Introduction

Sjogren's Syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the exocrine glands. Sjogren's syndrome without any other autoimmune disease is called primary Sjogren's syndrome (PSS) The clinical presentation that develops together with other autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, and scleroderma is defined as secondary Sjogren's Syndrome (SSS) [1, 2].

A multidisciplinary approach, including a rheumatologist and an ophthalmologist, leads to the diagnosis of SS based on clinical, laboratory, and histopathological findings [1-4]. Serological detection of anti-SSA/Ro autoantibodies, which occur in 67% of SS cases, and anti-SSB/La autoantibodies, which are detected in 49% of the cases, play an essential role in diagnosis and prognosis [

1]. There are cases in the literature that are anti-SSA/Ro and anti-SSB/La negative, along with anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) positive. This group has been referred to as "seronegative SS." Therefore, studies are being conducted to find new biomarkers in serum that contribute to diagnosis and early detection. It has been reported that serum BAFF levels increase in many autoimmune diseases such as SLE, PSS, RA, and immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) [

5]. Overexpression of α-Enolase has been detected in chronic autoimmune diseases such as RA, systemic sclerosis, and primary nephropathies. Autoantibodies against α-Enolase are detected very early in the sera of patients with RA and have been reported to have potential diagnostic and prognostic value [

6]. Wei et al. reported that overexpression of α-Enolase and high antibody levels in the serum might be associated with salivary gland hypofunction and inflammatory immune response. Therefore, α-Enolase expression can be used as a biomarker for PSS [

7]. SS patients are reported to have significantly higher levels of MMP-9 in their saliva and labial salivary glands compared to healthy controls [

8,

9]. Considering the pathogenesis of SS, MMP-9 activation causes significant changes in salivary gland parenchyma, extracellular matrix structure, and functions by destroying many extracellular matrix components, including type IV-V collagen and elastin [

8].

Additionally, a minor salivary gland biopsy, which is minimally invasive, is an important parameter helpful in diagnosing the disease [

4]. Sensitivity has been reported as 63.9%-85.7% and specificity as 61.2%-100% for minor salivary gland biopsy [

10]

. Although focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis, one of the histopathological findings, is one of the necessary criteria for diagnosis, there are differences between pathologists in the evaluation. In addition, studies have reported that in approximately half of the cases with focal lymphocyte sialoadenitis, no antibodies against Ro and La antigens were detected serologically. This shows that most patients cannot be diagnosed clinically without a salivary gland biopsy [

4]. Although focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis, one of the histopathological findings, is one of the necessary criteria for diagnosis, there are differences between pathologists in the evaluation. In addition, studies have reported that in approximately half of the cases with focal lymphocyte sialoadenitis, no antibodies against Ro and La antigens were detected serologically. This shows that most patients cannot be diagnosed clinically without a salivary gland biopsy [

4]. In addition, in biopsy specimens from patients with PSS, diffuse mild to moderate acinar atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, ductal dilatation, non-specific chronic sialoadenitis, sclerosing chronic sialoadenitis, granulomatous inflammation, and lymphoid follicular cells are also observed [

10].

SS is difficult to diagnose early, but late diagnosis is more likely to result in severe systemic complications and lymphoproliferative disease. Therefore, different biomarkers are recommended for diagnosing and treating SS and its subtypes. In this regard, it is anticipated that identifying specific markers will assist in developing more personalized treatments and better outcomes [

1].

This study aimed to evaluate tissue expressions of serological markers used in daily practice and investigate their diagnostic value.

Materials and Methods

PSS cases with salivary gland biopsy samples submitted to Akdeniz University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pathology, between 01.01.2006 and 31.12.2018, were scanned from the archive. Among these cases, 39 PSS cases with clinical follow-up and adequate (4mm 2) tissue in the paraffin block were selected as the study group. As the control group, 12 non-specific chronic sialoadenitis and 9 standard salivary gland cases with adequate tissue were determined. PSS cases were evaluated by Chisholm and Mason ACR/EULAR 2016 Classification criteria. In addition, a hospital automation system was used to obtain demographic and clinical information about the patients.

Sections of 4 microns were taken from paraffin-embedded salivary gland tissues for hematoxylen-eosin and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. The tissue area (in micro and square millimeters) was measured microscopically using an image processing-based diagnosis and analysis system (argentite/camera 5) in patients diagnosed with Sjogren's syndrome in preparations stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The number of focal aggregates containing at least 50 lymphocytes in an area of 4 mm2 in the periductal or perivascular region and the focus score was calculated to identify focal lymphocytic sialadenitis- the histopathological diagnosis supporting the disease in biopsy specimens. Grading was conducted following the Chisholm Mason classification (Grade 0: normal, Grade 1: mild, Grade 2: moderate mononuclear cell infiltration, Grade 3: the presence of one focus, Grade 4: the presence of multiple foci).

Anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La, anti-enolase, anti-BAFF, and MMP-9 antibodies were applied on the sections taken using the standard procedure in a fully automatic Daco staining machine and analyzed under a light microscope.

Expressions of all antibodies in tissues in the ductus, acini, and inflammation area were evaluated. Staining intensity is graded into three groups: light, medium, and strong.

Linear membranous and cytoplasmic staining were accepted as positive staining, with BAFF, TRIM21(SS-A/Ro), MMP9, and ENO1(α-Enolase) as complete or partial. Nuclear expression of SS-B was evaluated as positive staining. No staining with BAFF, TRIM21, MMP9, ENO1 and SS-B antibodies was considered negative staining. Different dilutions for each antibody and positive controls were used for IHC staining (

Table 1).

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 17.0 program, was used for statistical analysis. Study data were evaluated by descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage, minimum, maximum). In addition, the Pearson chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used to comparing qualitative data. Statistical significance was accepted as p<0.05.

Results

Of the 60 cases included in the study, 90% (n=54) were female, and 10% (n=6) were male. Subjects ranged in age from 24 to 72; the mean age was 48.8 (Std ± 11.8).

While no staining was observed in the duct areas in the control group with TRIM21 (SS-A/Ro52) antibody, mild staining was detected in the ducts in the study group diagnosed with PSS (

Figure 1). TRIM21 expression significantly differed between the study and control groups (p<0.01). A mild expression was found in 51.3% of the patients with PSS, whereas no expression was found in the patients with NCS in the control group (

Table 2). A statistically significant difference was found between the control and PSS groups in terms of TRIM21 expression (p<0.01). Acini areas showed mild TRIM21 staining in all cases.

Nuclear expression was detected in all ducts and inflamed areas in the control and study groups with SSB. While focal SSB expression was observed in the acini of the control group, SSB expression was relatively high in the study group (

Figure 2).

BAFF expression was observed in the ducts in all cases. There was mild staining in the ducts of 42.8% of the normal and 33.4% of the NCS cases in the BAFF control group, but no intense staining was detected. Strong staining was detected in 48.2% of PSS cases (

Table 3). This intense staining was statistically significantly different between the study and control groups (p<0.01). All acini areas remain stain-free. The inflamed areas of NCS patients had mild staining in 66.7% of cases, whereas patients with PSS had moderate and strong staining in a more significant percentage (

Figure 3). BAFF expression rates are detailed in

Table 3.

Moderate and strong staining was detected in the ducts with ENO1 in both the study and control groups. Moderate staining was detected in all normal salivary gland biopsies duct areas, and strong expression was observed in all the NCS and study group cases (

Figure 4). The difference in ENO1 expression was statistically significant in the differential diagnosis of normal salivary gland and NCS and PSS (p<0.01). Furthermore, serous glands showed intense staining with ENO-1, while mucinous glands showed mild staining. 66.7% of patients with NCS are ENO1 negative in the inflamed areas; however, mild staining was detected in 33.3% of them. 20.5% of the patients with PSS showed mild, 46.2% moderate, and 33.3% showed intense staining (

Figure 4) (

Table 3). The difference was statistically significant (p<0.01).

A total of 52.4% of the control group had MMP-9 antibodies in the duct areas; 4.8% had antibodies in the normal biopsy subgroup; 47.6% had antibodies in the NCS subgroup. Mild staining was detected in 84.6% of the study group (

Figure 5) (

Table 2). The study and control groups did not differ statistically significantly (p=0.07) (

Table 3). Acini and inflamed areas were not stained with MMP-9 in any case.

Discussion

PSS is an autoimmune disease with clinical diagnostic difficulties [

11]; to diagnose PSS, serum SS-A/Ro and SSB/La antibodies are assessed clinically [

12]. Serological tests are positive in approximately half of all PSS cases [

1]. Serological data are diagnostic when combined with clinical findings, but their sensitivity is low. Consequently, it is necessary to find different biomarkers and apply different techniques. Considering the pathogenesis of PSS, it is known that tissue damage occurs with autoantibodies before clinical findings appear [

1,

13]. Literature on IHC in salivary gland biopsies is limited. In the study by Aqrawi et al., IHC'sal Ro52 (SS-A)/TRIM21 expressions in the salivary gland were evaluated: PSS patients showed higher levels of Ro52 (SS-A)/TRIM21 expression than control subjects [

14]. Another study found high levels of Ro52/TRIM21 expression in acinar and ductal areas in the control and study groups [

15].

Similarly to the literature, mild staining was detected in the study group, while no staining was in the control group. In addition, there was no expression in patients with NCS containing an area of inflammation in the control group, while 51% of patients with PSS had mild expression. Unlike previous studies, we observed mild acinar staining in all cases.

While serum Anti-SSB/La positivity is highly specific, its sensitivity (40%) in diagnosing PSS is relatively low compared to autoimmune disorders like SLE [

16]. Currently, no IHC study has been conducted on salivary gland tissue in patients with SS. Our research detected nuclear staining in all ducts, acini, and inflammation areas in the control and study groups with SSB/La antibodies. Staining was noted in the nuclei of the acini, although it was more prevalent in the group with pSS than in the patients with NCS. When the NCS and PSS groups were compared with standard salivary gland samples, expression was relatively weak in normal salivary gland acini. Based on these findings, artificial intelligence-based algorithms may be able to standardize evaluations and find meaningful breakpoints.

Increased serum BAFF levels and strong expression of lymphocytes infiltrating the salivary glands have been reported. Additionally, BAFF serum levels were elevated in autoimmune diseases such as SLE and RA [

17,

18]. According to the literature, salivary gland samples from patients with PSS expressed more BAFF than those with NCS [

18]. As evidenced by our study, there was more expression in both ducts and inflammation areas in PSS cases than in NCS cases (p<0.01).

A limited study reported that α-Enolase (ENO1) was overexpressed in the minor salivary glands of PSS cases using the proteomic method [

7,

19]. In the study by Wei et al., increased expression of ENO1 in IHC and ductal and acinar areas was found in PSS cases compared to normal salivary glands. In addition, expression in regions of inflammation has been reported in PSS cases [

7]. Similarly, our study found that cases with PSS and NCS showed more robust expression in the duct areas than normal salivary gland cases, and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.01). Consistent with the literature, varying degrees of expression was found in all PSS cases, and mild expression was found in 33.3% of NCS cases.

In some of the studies in the literature, MPP-9 was detected in acinar and ductal cells in PSS cases by immunolocalization [

20]. It has been reported that MMP expression is increased in the salivary gland of patients with PSS compared to the control group, which includes inflammation in the acinar areas [

8]. In our study, mild expression was observed in the ducts in 84.6% of the patients with PSS and 83.3% with NCS. However, there was no expression in the ducts of the normal salivary gland group. No expression was observed in acini and ducts in all groups with MMP-9.

Studies have reported that histopathological findings such as focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis, ductal dilatation, adipose tissue infiltration, and fibrosis can be seen as a part of the aging process in healthy individuals [

21]. In addition, the observation of other histo-morphological findings (such as NCS, Slerosing sialoadenitis) and focal chronic sialoadenitis in salivary gland biopsies used to define the disease may cause difficulties in the interpretation of biopsies [

11].

Conclusion

Consequently, it is understood that clinically it can be used as an auxiliary marker to support the diagnosis in daily practice by evaluating the expression levels of TRIM 21 (Ro52), ENO1 (α-enolase), MMP9, and BAFF in patients with PSS. Still, more studies with more extensive series are needed for these markers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and I.H.O; methodology, C.S. software, V.Y; validation, N.Y., I.H.O. and C.S.; formal analysis, V.Y.; investigation, N.Y.; resources, N.Y.; data curation, V.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.; writing—review and editing, C.S.; visualization, I.H.O.; supervision, I.H.O.; project administration, V.Y.; funding acquisition, I.H.O.

Ethics Committee

This study was conducted at Akdeniz University, School of Medicine, Department of Pathology, with a Local Institutional Ethics Committee approval (Decision date: 27.02.2019 and Decision Number: 70904504) by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our very great appreciation to Assoc. Prof. Dr. Havva Serap Toru (Department of Pathology, Akdeniz University, School of Medicine, Antalya /Turkey) for her valuable and constructive suggestions during the development of this article. Her willingness to give her time so generously has been very much appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baldini, C., Ferro, F., Elefante, E., Bombardieri, S., Biomarkers for Sjogren's syndrome. Biomarkers in Medicine, 2018, 12(3), 275-286.

- Stefanski, AL, Tomiak C., Pleyer, U., Dietrich, T., Burmester, GR, Dörner, T., The diagnosis and treatment of Sjogren's syndrome. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 2017, 114(20), 354-361.

- Gobeljic, MS, Milic, V., Pejnović, N., Damjanov, N., Oral Disorders in Sjögren's Syndrome. Serbian Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research,2018,23,1-12.

- Pereira, DL, Vilela, SV, Dos Santos, TCRB, Pires FR, Clinical and laboratorial profile and histological features on minor salivary glands from patients under investigation for Sjögren's syndrome. Medicina Oral, Pathologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal, 2014, 19(3), 237-241.

- Vincent, F.B.; Saulep-Easton, D.; Figgett, W.A.; Fairfax, K.A.; Mackay, F. The BAFF/APRIL system: Emerging functions beyond B cell biology and autoimmunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 203–215. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ramos, À.; Roig-Borrellas, A.; García-Melero, A.; López-Alemany, R. α-Enolase, a Multifunctional Protein: Its Role on Pathophysiological Situations. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 156795. [CrossRef]

- Wei P., Xing Y., Li B., Chen F., Hua H., Proteomics-based analysis indicating α-enolase as a potential biomarker in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Gland Surgery, 2020, 9(6), 2054–2063.

- Perez P., Goicovich E., Alliende C., Aguilera S., Leyton C., Molina C., Pinto R., Romo R., Martinez B., Gonzalez MJ, Differential expression of matrix metalloproteinases in labial salivary glands of patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatology, 2000, 43, 2807–2817.

- Konttinen YT, Halinen S., Hanemaaijer R., Sorsa T., Hietanen J., Ceponis A., Xu JW, Manthorpe R., Whittington J., Larsson A., Salo T., Kjeldsen L., Stenman UH , Eisen AZ, Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 type IV collagenase/gelatinase implicated in the pathogenesis of Sjogren's syndrome . Matrix Biology, 1998, 17, 335–347.

- Bautista-Vargas M., Vivas AJ, Tobón GJ, Minor salivary gland biopsy: Its role in the classification and prognosis of Sjogren's syndrome . Autoimmuns Reviews, 2020, 19(12), 1-28.

- Monsalve, D.M.; Anaya, J.-M. With Minor Salivary Gland Biopsy in Sjogren Syndrome, Is a Negative Result Possible?. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 310–312. [CrossRef]

- Oke V., Wahren-Herlenius M., The immunobiology of Ro52 (TRIM21) in autoimmunity: a critical review. Journal of Autoimmunity, 2012, 39, 77–82.

- Theander E., Jonsson R., Sjostrom B., Brokstad K., Olsson P., Henriksson G., Prediction of Sjogren's syndrome years before diagnosis and identification of patients with early onset and severe disease course by autoantibody profiling . Arthritis Rheumatology, 2015, 67(9), 2427–2436.

- Aqrawi LA, Kvarnstrom M., Brokstad KA, Jonsson R., Ductal epithelial expression of Ro52 correlates with inflammation in salivary glands of patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome . Clinical and Experimental Immunology , 2014, 177, 244–252.

- Kyriakidis, NC, Kapsogeorgou EK, Gourzi VC, Konsta OD, Baltatzis GE, Tzioufas AG, Toll -like receptor 3 stimulation promotes Ro52/TRIM21 synthesis and nuclear redistribution in salivary gland epithelial cells, partially via type I interferon pathway . 2014, Clinical and Experimental Immunology, 178, 548–560.

- Konsta, OD, Le Dantec C., Charras A., Cornec D., Kapsogeorgou EK, Tzioufas AG, Pers JO, Renaudineau Y. Defective DNA methylation in salivary gland epithelial acini from patients with Sjögren's syndrome is associated with SSB gene expression, anti-SSB/La detection, and lymphocyte infiltration. Journal of Autoimmunity, 2016, 68, 30–38.

- Yoshimoto K, Tanaka M, Kojima M, Setoyama Y., Kameda H., Suzuki K., Tsuzaka K., Ogawa Y., Tsubota K., Abe T., Takeuchi T., Regulatory mechanisms for the production of BAFF and IL-6 are impaired in monocytes of patients of primary Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Research and Therapy, 2011, 13(5), R170.

- Carrillo-Ballesteros, F.J.; Palafox-Sánchez, C.A.; Franco-Topete, R.A.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F.; Orozco-Barocio, G.; Martínez-Bonilla, G.E.; Gómez-López, C.E.; Marín-Rosales, M.; López-Villalobos, E.F.; Luquin, S.; et al. Expression of BAFF and BAFF receptors in primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients with ectopic germinal center-like structures. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 20, 615–626. [CrossRef]

- Hjelmervik TO, Jonsson R., Bolstad AL, The minor salivary gland proteome in Sjögren's syndrome. Oral Diseases, 2009,15, 342-353.

- Ram, M.; Sherer, Y.; Shoenfeld, Y. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 and Autoimmune Diseases. J. Clin. Immunol. 2006, 26, 299–307. [CrossRef]

- Lamas-Gutierrez FJ, Reyes E., Martinez B, Hernandez-Molina G, Histopathological environment besides the focus score in Sjögren's syndrome. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 2014, 17, 898-903.

Figure 1.

A-B, no staining was observed in the duct areas in the Normal salivary gland (H&E, x200) (DAB, x200), C-D, mild staining was detected in the duct and inflammation areas in patients with Primary Sjogren's Syndrome (H&E, x200) (DAB, x200).

Figure 1.

A-B, no staining was observed in the duct areas in the Normal salivary gland (H&E, x200) (DAB, x200), C-D, mild staining was detected in the duct and inflammation areas in patients with Primary Sjogren's Syndrome (H&E, x200) (DAB, x200).

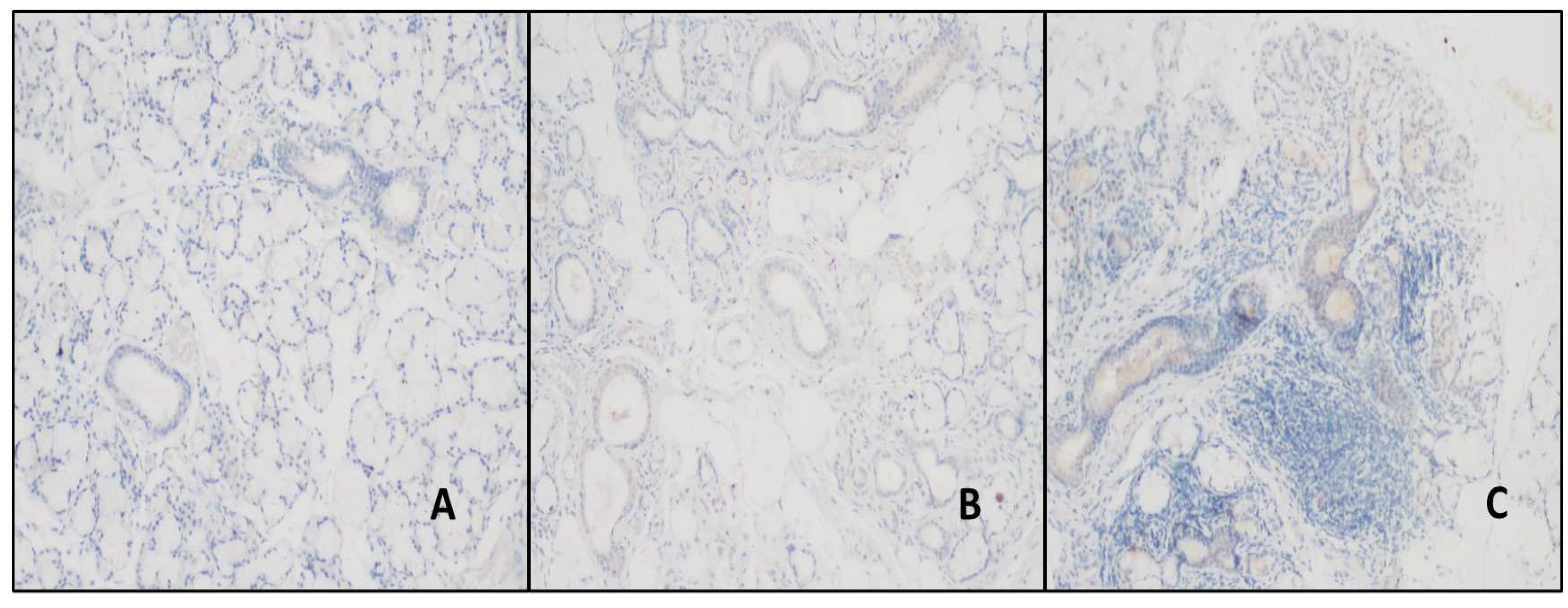

Figure 2.

A, SS-B antibody in the normal salivary gland and nuclear in duct and acini areas. staining (DAB, x200), B-C, Nuclear staining in the ductus, acini, and inflammation areas in the patient with NCC and PSS (DAB, x100, and x100).

Figure 2.

A, SS-B antibody in the normal salivary gland and nuclear in duct and acini areas. staining (DAB, x200), B-C, Nuclear staining in the ductus, acini, and inflammation areas in the patient with NCC and PSS (DAB, x100, and x100).

Figure 3.

A- Staining in duct areas with BAFF antibody in normal salivary gland (DAB, x200). B-C, the ducts and areas of inflammation were more stained in patients with PSS than in patients with NCC (DAB, x200, and x200).

Figure 3.

A- Staining in duct areas with BAFF antibody in normal salivary gland (DAB, x200). B-C, the ducts and areas of inflammation were more stained in patients with PSS than in patients with NCC (DAB, x200, and x200).

Figure 4.

A- Moderate staining in duct areas with ENO1 antibody in normal salivary gland (DAB, X100). BC- In cases with NSC and PSS, stronger staining was detected in the duct areas, and in the cases with PSS, stronger staining was detected in the areas of inflammation than in the patients with NSC (DAB, X100, and X100).

Figure 4.

A- Moderate staining in duct areas with ENO1 antibody in normal salivary gland (DAB, X100). BC- In cases with NSC and PSS, stronger staining was detected in the duct areas, and in the cases with PSS, stronger staining was detected in the areas of inflammation than in the patients with NSC (DAB, X100, and X100).

Figure 5.

ABC- While no MMP9 antibody was detected in normal salivary gland ducts, similar staining was found in these areas in patients with NSC and PSS (DAB, x100, x100, and x100).

Figure 5.

ABC- While no MMP9 antibody was detected in normal salivary gland ducts, similar staining was found in these areas in patients with NSC and PSS (DAB, x100, x100, and x100).

Table 1.

The primary antibodies used, the dilution ratios, and the positive control tissues.

Table 1.

The primary antibodies used, the dilution ratios, and the positive control tissues.

| Primary antibody |

Company |

Dilution rate |

Positive control |

Anti-BAFF antibodies

[ab217329], RabPAb |

abcam |

1/150 |

Tonsil |

Anti TRIM21 (SS-A/Ro) antibodies

[ab191690], RabPAb |

abcam |

1/100 |

Tonsil |

Anti MMP9 antibodies

[56-2A4, ab 58803], MauseMAb |

abcam |

1/100 |

Tonsil |

Anti ENO1 antibodies

[EPR19758, ab 227978], RabMAb |

abcam |

1/200 |

Pancreas |

Anti SS-B antibodies

[EPR6570, ab 124932], RabMAb |

abcam |

1/250 |

Colon |

Table 2.

Staining with TRIM 21, BAFF, and ENO1 antibodies in the areas of inflammation in the control group (in patients with Non-specific Chronic Sialoadenitis) and primary Sjogren's Syndrome.

Table 2.

Staining with TRIM 21, BAFF, and ENO1 antibodies in the areas of inflammation in the control group (in patients with Non-specific Chronic Sialoadenitis) and primary Sjogren's Syndrome.

| Antibody |

NCS (n=12) |

PSS (n=39) |

| N |

P |

N |

P |

| M |

MD |

S |

M |

MD |

S |

| TRIM21 |

12

100%

|

|

|

|

19

48.7% |

20

51.3% |

|

|

| BAFF |

3

25% |

8

66.7% |

one

8.3% |

|

|

4

10.3% |

16

41% |

19

48.7% |

| ENO1 |

8

66.7% |

4

33.3% |

|

|

|

8

20.5% |

18

46.2% |

13

33.3% |

| NCS: Non-specific Chronic Sialoadenitis, PSS: primary Sjogren's Syndrome, N: Negative, P: Positive, M: Mild, MD: Moderate, S: Strong |

Table 3.

The staining of duct areas with TRIM 21, BAFF, ENO1, and MMP-9 antibodies in the control and study groups.

Table 3.

The staining of duct areas with TRIM 21, BAFF, ENO1, and MMP-9 antibodies in the control and study groups.

| Antibody |

Control group (n=21) |

Patient group

PSS (n=39) |

P value |

| Normal (n=9) |

NCS (n=12) |

| N |

P |

N |

P |

N |

P |

| M |

MD |

S |

H |

HE |

S |

|

M |

MD |

S |

|

|

| TRIM21 |

9

42.8% |

|

|

|

12

57.2% |

|

|

|

|

39

100% |

|

|

p <0.01 |

|

| BAFF |

|

9

42.8% |

|

|

|

7

33.4% |

5

23.8% |

|

|

5

12.8% |

15

38.4% |

19

48.8% |

p <0.01 |

|

| ENO1 |

|

|

9

42.8% |

|

|

|

|

12

57.2% |

|

|

|

39

100% |

p <0.01 |

|

| MMP-9 |

8

38.1% |

one

4.8% |

|

|

2

9.5% |

10

47.6% |

|

|

6

15.4% |

33

84.6% |

|

|

P=0.07 |

|

| NCS: Non-specific Chronic Sialoadenitis, PSS: primary Sjogren's Syndrome, N: Negative, P: Positive, M: Mild, MD: Moderate, S: Strong |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).