Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Relevant literature

2.2. Methodology

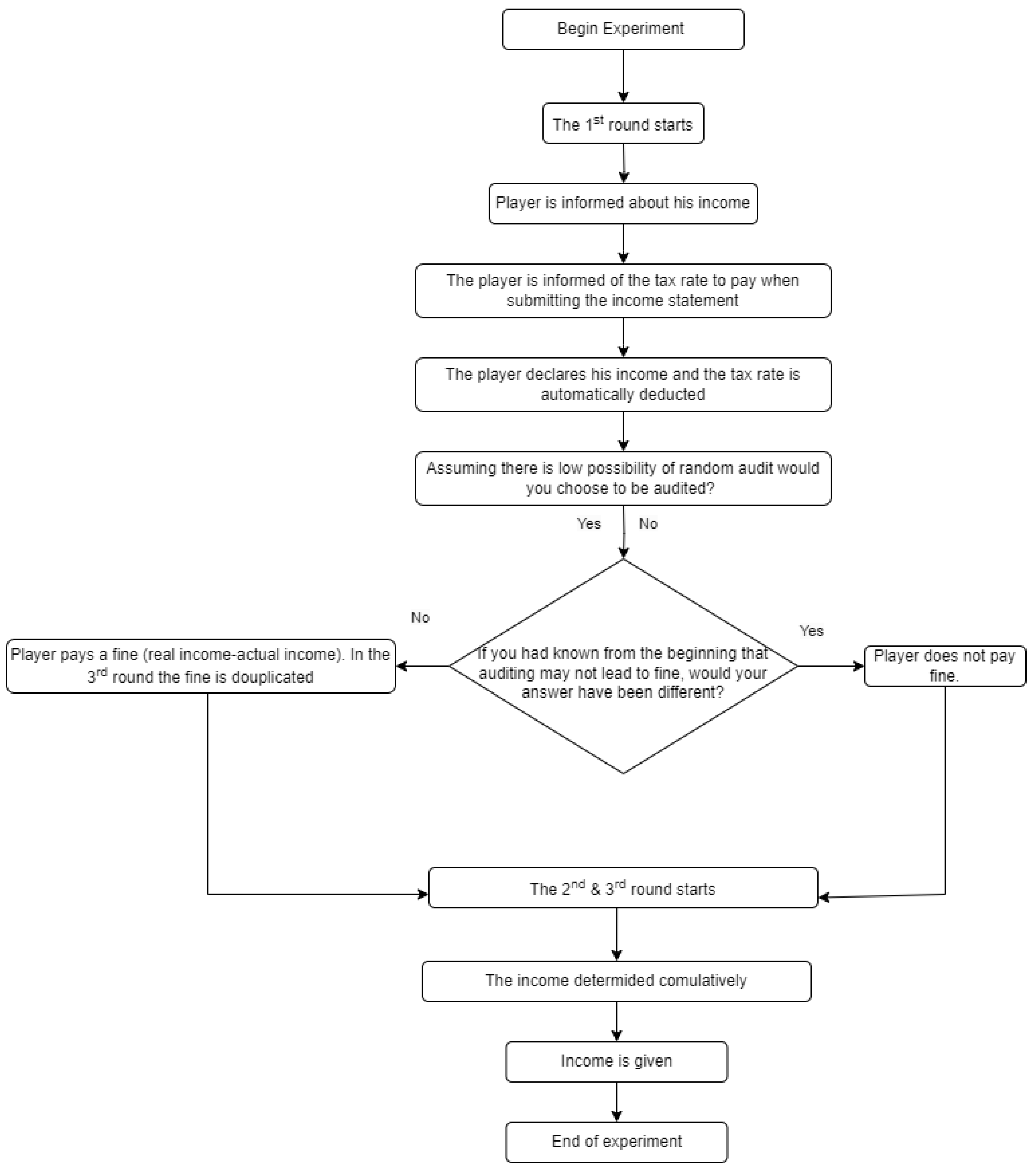

2.2.1. Experimental Design

- T5: Represents a tax rate of 5% and is combined with an audit probability of 10% (P10).

- T47: Corresponds to a tax rate of 47% and is associated with an audit probability of 5% (P5).

- T25: Signifies a tax rate of 25% and is coupled with an unknown audit probability (UP).

2.2.2. Subject recruitment & research questions analysis

2.2.3. Content analysis

3. Results

3.1. Average compliance

3.2. Distribution of compliance

3.3. Regression analysis

| Compliance rate | |

| Assets = 2 | 0.087*** |

| (0.030) | |

| Assets = 3 | 0.100* |

| (0.059) | |

| Assets = 4 | 0.001 |

| (0.123) | |

| Assets = 5 | 0.121* |

| (0.063) | |

| Gender = 1 | 0.100** |

| (0.041) | |

| Stage = 2 | -0.224*** |

| (0.040) | |

| Stage = 3 | 0.086** |

| (0.040) | |

| Investment = 1 | -0.041 |

| (0.025) | |

| Legal Status = 2 | 0.087* |

| (0.044) | |

| Legal Status = 3 | 0.140*** |

| (0.052) | |

| Legal Status = 4 | 0.195** |

| (0.089) | |

| Legal Status = 5 | 0.057* |

| (0.034) | |

| Danger = 2 | -0.049 |

| (0.033) | |

| Observations | 300 |

| R-squared | 0.417 |

| F-test | 13.566 |

| Prob > F | 0.000 |

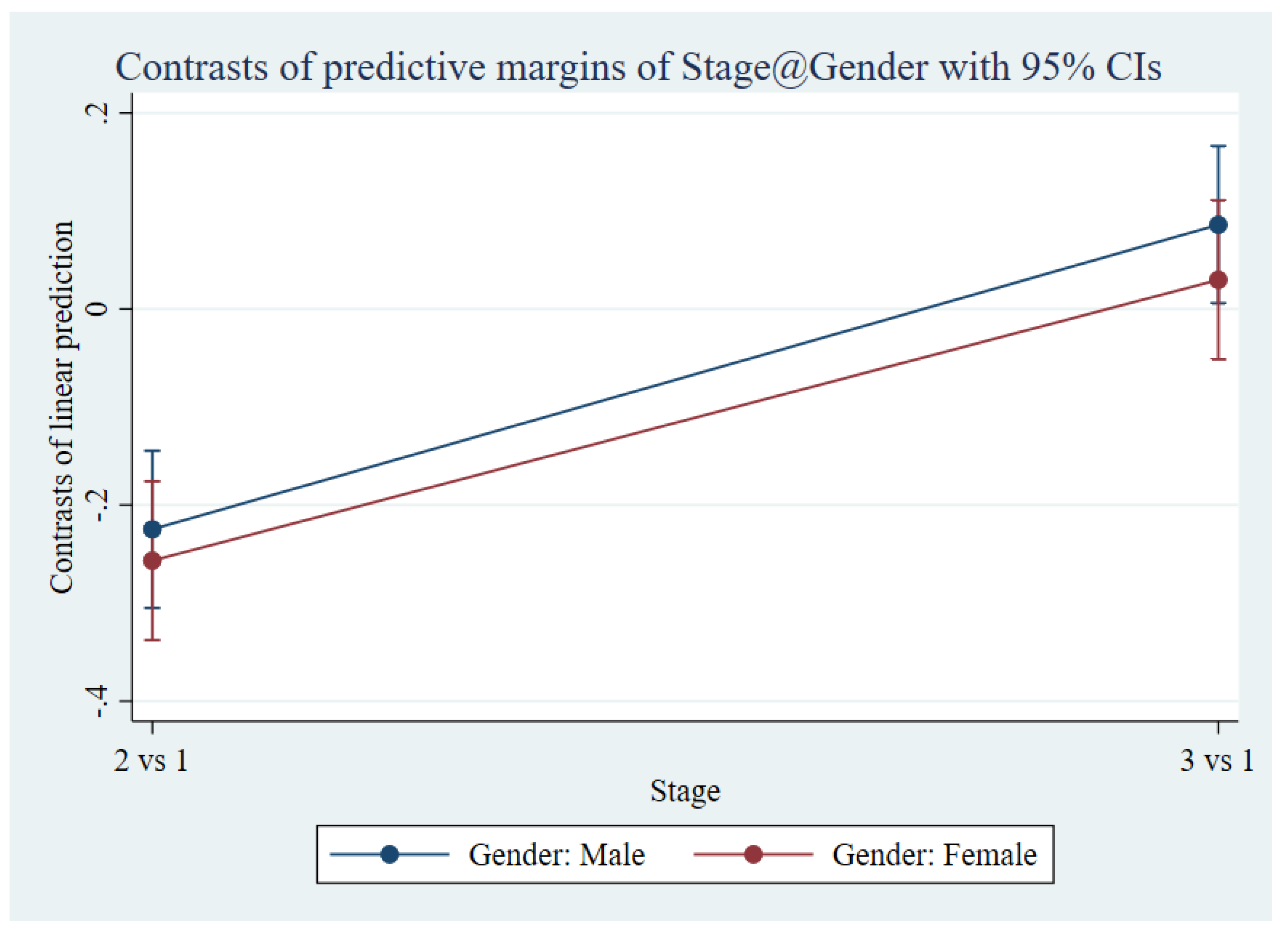

| df | F | P > t | |

| Stage@Gender | |||

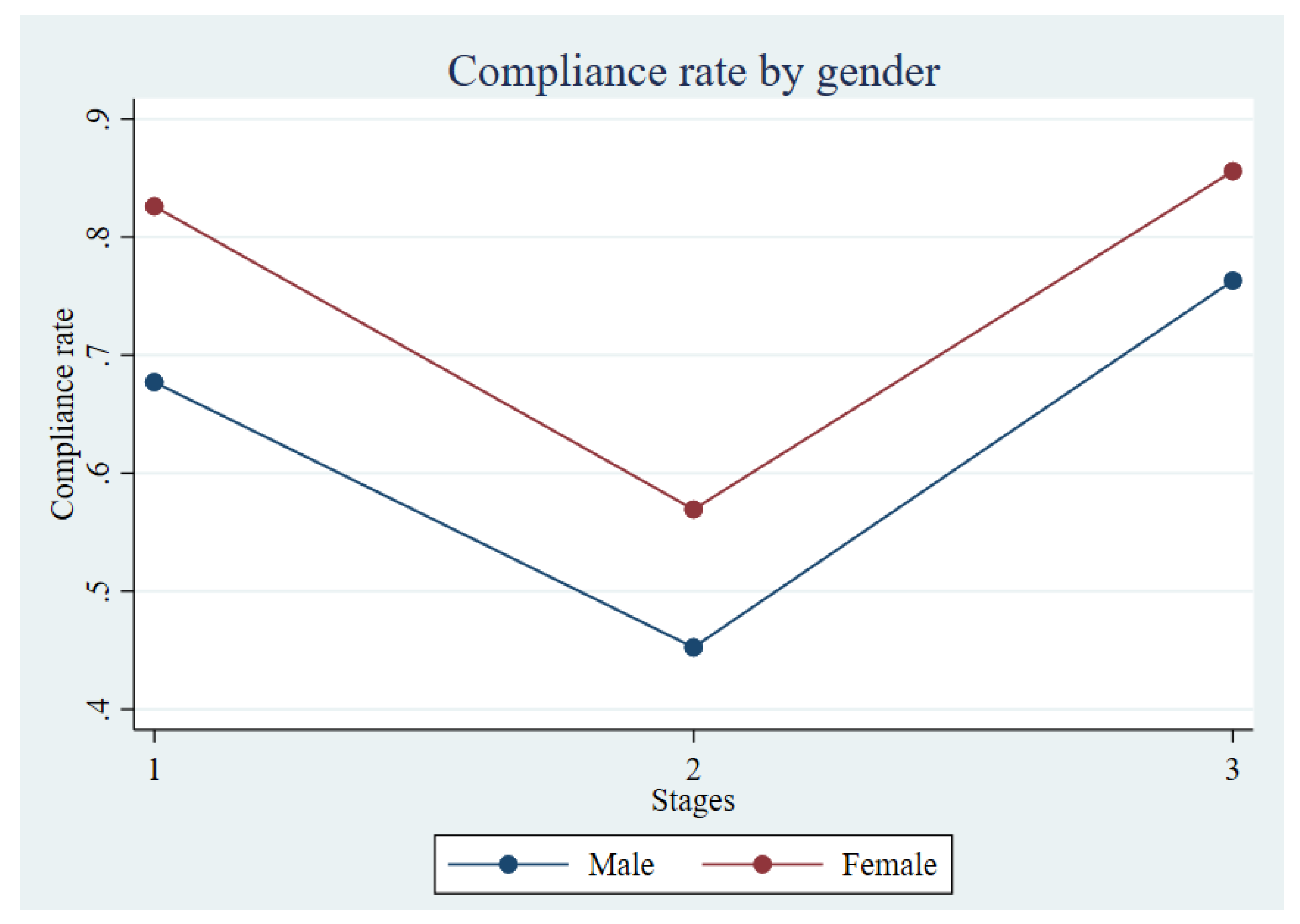

| (2 vs 1) Male | 1 | 30.32 | 0.000 |

| (2 vs 1) Female | 1 | 38.77 | 0.000 |

| (3 vs 1) Male | 1 | 4.44 | 0.035 |

| (3 vs 1) Female | 1 | 0.60 | 0.337 |

| Joint | 4 | 30.18 | 0.000 |

| Denominator | 284 |

| Stage@Gender | Contrast | Std. err. | t | P > t | 95% conf. interval | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| (2 vs 1) Male | -0.224 | 0.04 | 0.000 | -0.305 | -0.144 | |

| (2 vs 1) Female | -0.256 | 0.041 | 0.000 | -0.337 | -0.175 | |

| (3 vs 1) Male | 0.086 | 0.40 | 0.036 | 0.005 | 0.166 | |

| (3 vs 1) Female | 0.031 | 0.041 | 0.337 | -0.043 | 0.113 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Compliance Rate | FE | RE | BE | PA |

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Gender = 1, Female | 0.071** | 0.071** | 0.071** | 0.071** |

| (0.028) | (0.032) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |

| Stage = 2 | -0.240*** | -0.240*** | -0.240*** | -0.240*** |

| (0.028) | (0.027) | (0.025) | (0.025) | |

| Stage = 3 | 0.059** | 0.059** | 0.059** | 0.059** |

| (0.026) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.025) | |

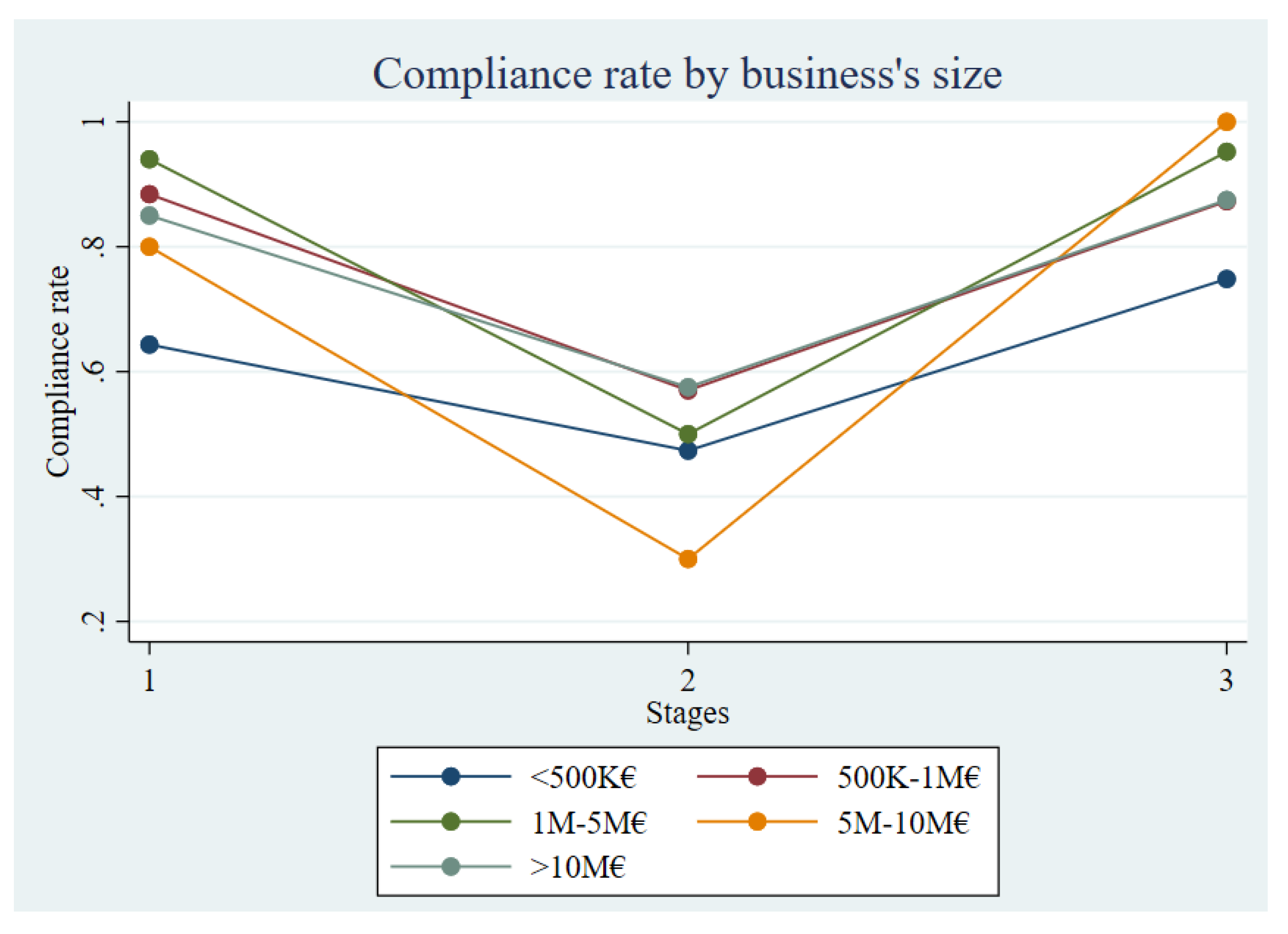

| Assets = 2, 500K-1M€ | 0.093*** | 0.093** | 0.093*** | 0.093*** |

| (0.032) | (0.038) | (0.035) | (0.035) | |

| Assets = 3, 1M-5M€ | 0.104** | 0.104 | 0.104 | 0.104 |

| (0.041) | (0.075) | (0.069) | (0.069) | |

| Assets = 4, 5M-10M€ | -0.017 | -0.017 | -0.017 | -0.017 |

| (0.056) | (0.159) | (0.146) | (0.146) | |

| Assets = 5, >10M€ | 0.127 | 0.127 | 0.127* | 0.127* |

| (0.119) | (0.081) | (0.074) | (0.074) | |

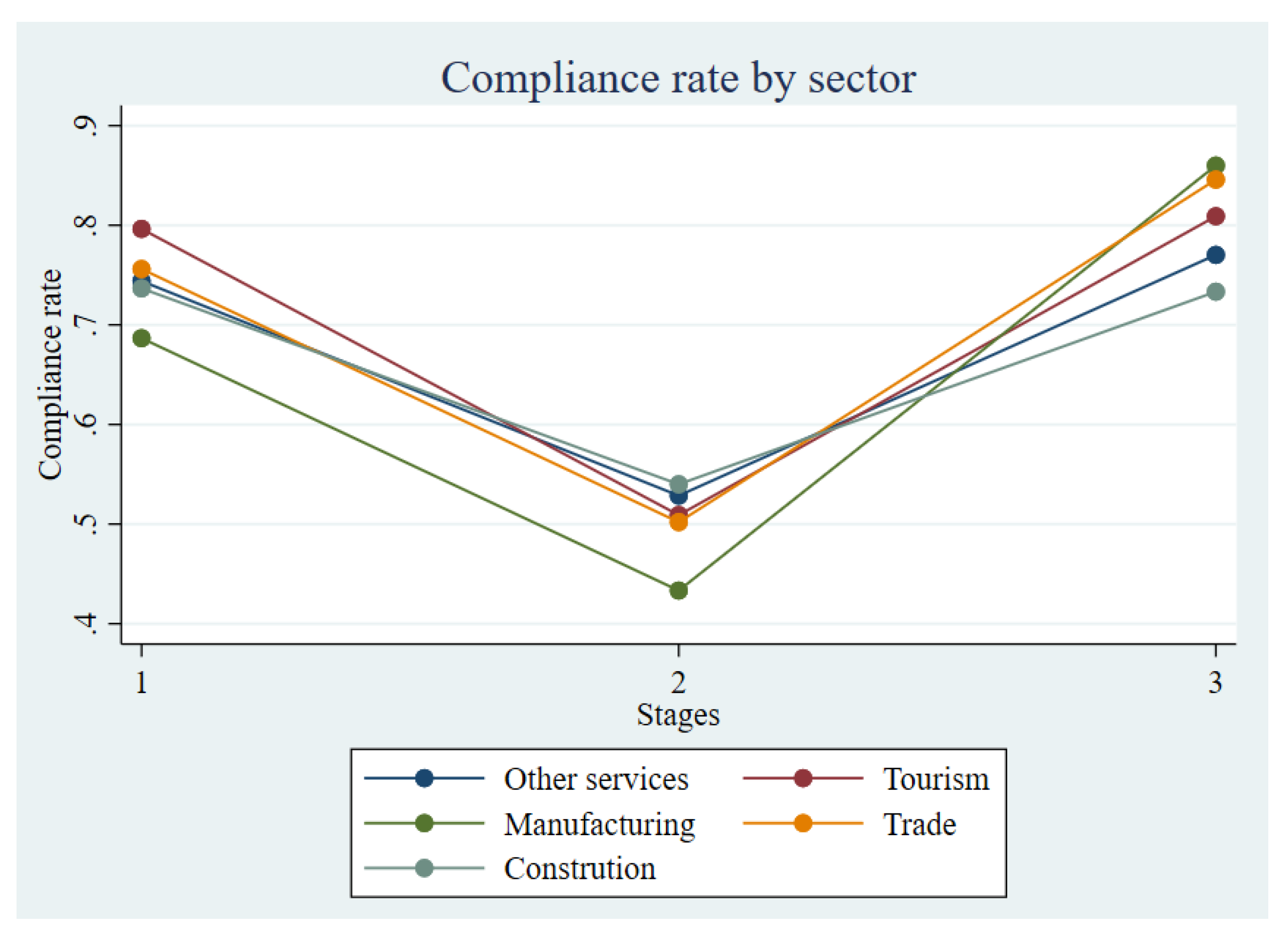

| Sector = 2, Tourism | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.034 |

| (0.054) | (0.056) | (0.051) | (0.051) | |

| Sector = 3, Manufacturing | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| (0.047) | (0.068) | (0.062) | (0.062) | |

| Sector = 4, Trade | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.032) | (0.032) | |

| Sector = 5, Construction | -0.001 | -0.001 | -0.001 | -0.001 |

| (0.062) | (0.066) | (0.060) | (0.060) | |

| Investment = 1, Stock Market | -0.041 | -0.041 | -0.041 | -0.041 |

| (0.027) | (0.032) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |

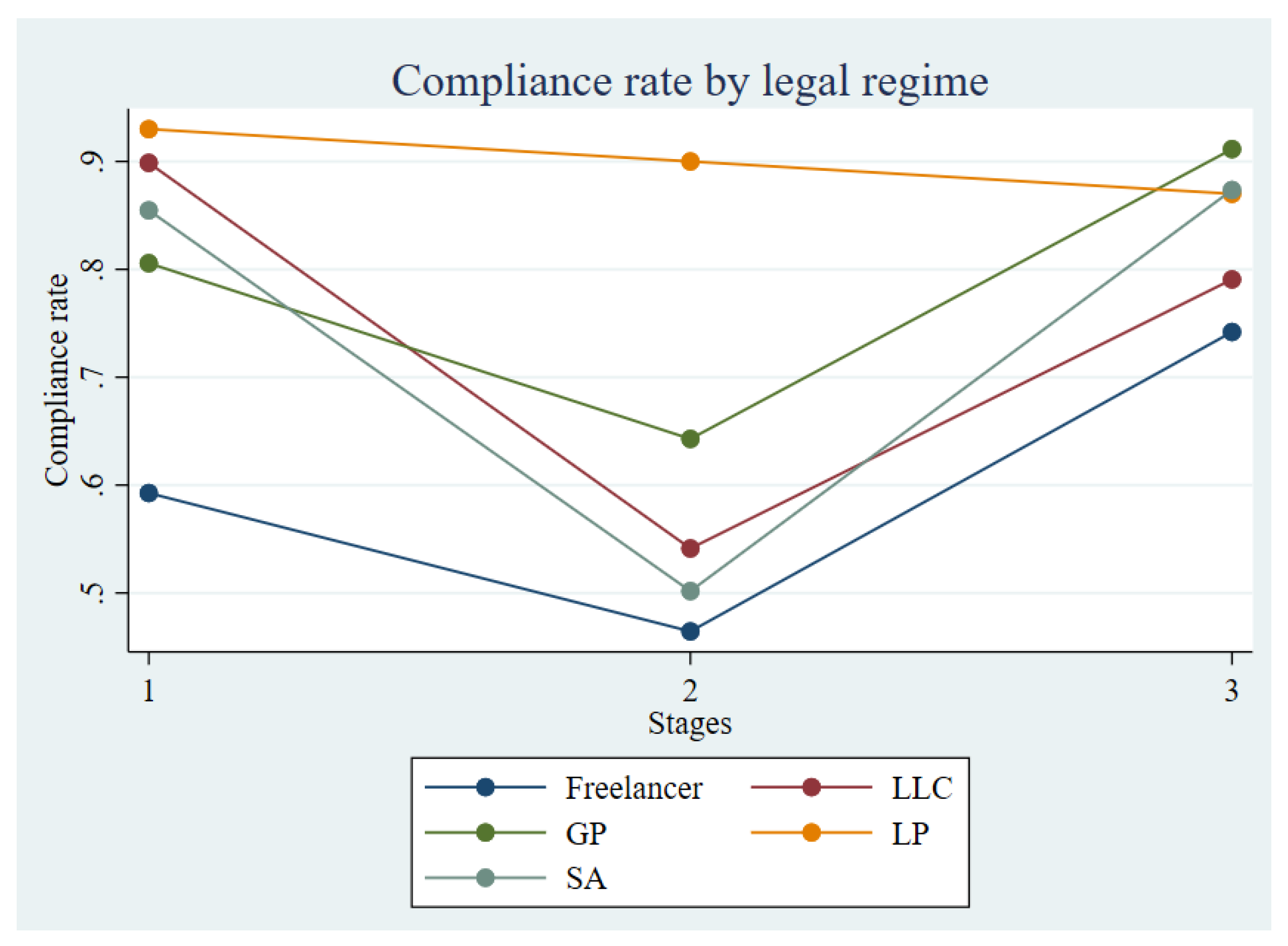

| Legal Status = 2, LLC | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.090* | 0.090* |

| (0.055) | (0.055) | (0.051) | (0.051) | |

| Legal Status = 3, GP | 0.140*** | 0.140** | 0.140** | 0.140** |

| (0.045) | (0.065) | (0.060) | (0.060) | |

| Legal Status = 4, LP | 0.188*** | 0.188 | 0.188* | 0.188* |

| (0.049) | (0.115) | (0.105) | (0.105) | |

| Legal Status = 5, SA | 0.056 | 0.056 | 0.056 | 0.056 |

| (0.040) | (0.042) | (0.039) | (0.039) | |

| Danger = 2, Risk Lover | -0.045 | -0.045 | -0.045 | -0.045 |

| (0.044) | (0.043) | (0.039) | (0.039) | |

| Constant | 0.656*** | 0.750*** | 0.596*** | 0.656*** |

| (0.057) | (0.016) | (0.052) | (0.050) | |

| Observations | 297 | 297 | 297 | 297 |

| R-squared | 0.442 | 0.390 | ||

| Number of ID | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and future research

5. Conclusions

Appendix A. Guides of Participants

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix B. Guidelines and Procedures

Appendix B.1. Verbal Guidelines (Interpreted from Greek)

Appendix B.2. Instructions on the First Screen (All Treatments)

Appendix C. Profile questions

References

- Alm, J.; Cherry, T.; Jones, M.; McKee, M. Taxpayer information assistance services and tax compliance behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology 2010, 31, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J.; Cherry, T.; Jones, M.; McKee, M. Encouraging filing via tax credits and social safety nets. The IRS Research Bulletin: Proceedings of the 2008 IRS Research Conference 2008, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Friedland, N.; Maital, S.; Rutenberg, A. A simulation study of income tax evasion. Journal of Public Economics 1978, 10, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B. Speaking to theorists and searching for facts: Tax morale and tax compliance in experiments. Journal of Economic Surveys 2002, 16, 657–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleven, H.J.; Knudsen, M.B.; Kreiner, C.T.; Pedersen, S.; Saez, E. Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from a tax audit experiment in Denmark. Econometrica 2011, 79, 651–692. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, L.; Scartascini, C. Tax Compliance and Enforcement in the Pampas. Evidence from a Field Experiment. Inter-American Development Bank Working Paper Series, Washington, DC, Inter-American Development Bank, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Doerrenberg, P.; Schmitz, J. Tax compliance and information provision—A field experiment with small firms. ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper 2015, 15-028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascagni, G. From the lab to the field: A review of tax experiments. Journal of Economic Surveys 2018, 32, 273–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allingham, M.G.; Sandmo, A. Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics 1972, 1, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemrod, J.; Blumenthal, M.; Christian, C. Taxpayer response to an increased probability of audit: Evidence from a controlled experiment in Minnesota. Journal of Public Economics 2001, 79, 455–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangl, K.; Torgler, B.; Kirchler, E.; Hofmann, E. Effects of supervision on tax compliance: Evidence from a field experiment in Austria. Economics Letters 2014, 123, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, L.; Fonseca, M.A.; Myles, G. Lab experiment to investigate tax compliance: Audit strategies and messaging. HM Revenue and Customs Research 2013, 308. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, J.; Sanchez, I.; De Juan, A. Economic and noneconomic factors in tax compliance. KYKLOS-BERNE 1995, 48, 3–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Juan, A.; Lasheras, M.A.; Mayo, R. Voluntary compliance and behavior of Spanish taxpayers. Instituto de Estudios Fiscales, Madrid, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B.S.; Torgler, B. Tax morale and conditional cooperation. Journal of Comparative Economics 2007, 35, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaufus, K.; Bob, J.; Otto, P.E.; Wolf, N. The effect of tax privacy on tax compliance—An experimental investigation. European Accounting Review 2017, 26, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühren, C.; Kundt, T.C. Does the level of work effort influence tax evasion? Experimental evidence. Review of Economics 2014, 65, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coricelli, G.; Joffily, M.; Montmarquette, C.; Villeval, M.C. Cheating, emotions, and rationality: an experiment on tax evasion. Experimental Economics 2010, 13, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, B.; Lacroix, G.; Villeval, M.C. Tax evasion and social interactions. Journal of Public Economics 2007, 91, 2089–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, S.; Hoffmann, A. Tax evasion and risky investments in an intertemporal context: An experimental study. SFB 373 Discussion Paper 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pántya, J.; Kovács, J.; Kogler, C.; Kirchler, E. Work performance and tax compliance in flat and progressive tax systems. Journal of Economic Psychology 2016, 56, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomquist, K.M. A comparative analysis of reporting compliance behavior in laboratory experiments and random taxpayer audits. Proceedings. Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association 2009, 102, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Chateauneuf, A.; Eichberger, J.; Grant, S. Choice under uncertainty with the best and worst in mind: Neo-additive capacities. Journal of Economic Theory 2007, 137, 538–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J.; Erard, B.; Feinstein, J. Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature 1998, 36, 818–860. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, J.; McClelland, G.H.; Schulze, W.D. Why do people pay taxes? Journal of Public Economics 1992, 48, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, G.D.; Naylor, R.A. A model of tax evasion with group conformity and social customs. European Journal of Political Economy 1996, 12, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J.; Jackson, B.; McKee, M. Institutional uncertainty and taxpayer compliance. The American Economic Review 1992, 82, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Dhami, S.; Al-Nowaihi, A. Why do people pay taxes? Prospect theory versus expected utility theory. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 2007, 64, 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth, M. The use of field experiments to increase tax compliance. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 2014, 30, 658–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Anno, R. Tax evasion, tax morale and policy maker’s effectiveness. The Journal of Socio-Economics 2009, 38, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, M.; Christian, C.; Slemrod, J. Do normative appeals affect tax compliance? Evidence from a controlled experiment in Minnesota. National Tax Journal 2001, 54, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B. A field experiment in moral suasion and tax compliance focusing on underdeclaration and overdeduction. FinanzArchiv/Public Finance Analysis 2013, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner, G.; Sausgruber, R.; Traxler, C. Testing enforcement strategies in the field: Threat, moral appeal and social information. Journal of the European Economic Association 2013, 11, 634–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.S.; Koper, C.S. Deterring corporate crime. Criminology 1992, 30, 347–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, V.; Braithwaite, J.; et al. An evolving compliance model for tax enforcement. In Crimes of Privilege: Readings in White-Collar Crime; Oxford University Press: 2001.

- Yitzhaki, S. A note on income tax evasion: A theoretical approach. Journal of Public Economics 1974, 3, 201–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemrod, J. Cheating ourselves: The economics of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2007, 21, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBacker, J.; Heim, B.T.; Tran, A. Importing corruption culture from overseas: Evidence from corporate tax evasion in the United States. Journal of Financial Economics 2015, 117, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosonen, T.; Ropponen, O. The role of information in tax compliance: Evidence from a natural field experiment. Economics Letters 2015, 129, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, M.; Pomeranz, D.D.; Carrillo, P. Dodging the Taxman: Firm Misreporting and Limits to Tax Enforcement. 2015.

- Slemrod, J.; Collins, B.; Hoopes, J.L.; Reck, D.; Sebastiani, M. Does credit-card information reporting improve small-business tax compliance? Journal of Public Economics 2017, 149, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz, D. No taxation without information: Deterrence and self-enforcement in the value-added tax. American Economic Review 2015, 105, 2539–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and punishment: An economic approach. In The Economic Dimensions of Crime; Springer: 1968, pp. 13–68.

- Slemrod, J. The economics of corporate tax selfishness. National Tax Journal 2004, 57, 877–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, K.J.; Slemrod, J. Corporate tax evasion with agency costs. Journal of Public Economics 2005, 89, 1593–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, M.; Mills, L.F.; Slemrod, J.B. An empirical examination of corporate tax noncompliance. Ross School of Business Paper 2005, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, M.W.; Thomas, J.E. Audit probabilities and the tax evasion decision: An experimental approach. Journal of Economic Psychology 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.E. Introduction to experimental economics. The Handbook of Experimental Economics 1995, 1, 3–109. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, M.W.; Hero, R.E. Tax evasion and heuristics: A research note. Journal of Public Economics 1985, 26, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, P.J.; Davis, J.S.; Jung, W.O. Experimental evidence on taxpayer reporting under uncertainty. Accounting Review 1991, 535–558. [Google Scholar]

- Slemrod, J.; Weber, C. Evidence of the invisible: Toward a credibility revolution in the empirical analysis of tax evasion and the informal economy. International Tax and Public Finance 2012, 19, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.; Scartascini, C. Don’t blame the messenger: A field experiment on delivery methods for increasing tax compliance. IDB Working Paper No. IDB-WP-627 2015.

- Mogollon, M.; Ortega, D.; Scartascini, C. Who’s calling? The effect of phone calls and personal interaction on tax compliance. International Tax and Public Finance 2021, 28, 1302–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Carpio, L. Are the Neighbors Cheating? Evidence from a Social Norm Experiment on Property Taxes in Peru. Job Market Paper 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, T.; Monestier, F.; Pineiro, R.; Rosenblatt, F.; Tunón, G. Is paying taxes habit forming? Experimental evidence from Uruguay. Unpublished paper 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, J. Taxation and public opinion in Sweden: An interpretation of recent survey data. National Tax Journal 1974, 27, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onu, D.; Oats, L. “Paying tax is part of life”: Social norms and social influence in tax communications. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 2016, 124, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler, B. Behavioral taxation: Opportunities and challenges. CREMA Working Paper 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B. Moral suasion: An alternative tax policy strategy? Evidence from a controlled field experiment in Switzerland. Economics of Governance 2004, 5, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koessler, A.K.; Torgler, B.; Feld, L.P.; Frey, B.S. Commitment to pay taxes: Results from field and laboratory experiments. European Economic Review 2019, 115, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwenger, N.; Kleven, H.; Rasul, I.; Rincke, J. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivations for tax compliance: Evidence from a field experiment in Germany. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2016, 8, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neve, J.E.; Imbert, C.; Spinnewijn, J.; Tsankova, T.; Luts, M. How to improve tax compliance? Evidence from population-wide experiments in Belgium. Journal of Political Economy 2021, 129, 1425–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, R.G.; Martinez-Vazquez, J.; McKee, M.; Torgler, B. Tax morale affects tax compliance: Evidence from surveys and an artefactual field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 2009, 70, 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth, M.; List, J.A.; Metcalfe, R.D.; Vlaev, I. The behavioralist as tax collector: Using natural field experiments to enhance tax compliance. Journal of Public Economics 2017, 148, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, P.; Gamba, S. The impact of social pressure on tax compliance: A field experiment. International Review of Law and Economics 2016, 46, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.X.; Sinning, M. Trying to make a good first impression: A natural field experiment to engage new entrants to the tax system. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 2022, 100, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djawadi, B.M.; Fahr, R. The impact of tax knowledge and budget spending influence on tax compliance. IZA Discussion Papers 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B. Beyond punishment: A tax compliance experiment with taxpayers in Costa Rica. Revista de Análisis Económico 2003, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Holz, J.E.; List, J.A.; Zentner, A.; Cardoza, M.; Zentner, J.E. The $100 million nudge: Increasing tax compliance of firms using a natural field experiment. Journal of Public Economics 2023, 218, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belnap, A.; Welsch, A.; Williams, B. Remote tax authority. Journal of Accounting and Economics 2023, 75, 101570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M. Misperceptions of social norms about tax compliance: From theory to intervention. Journal of Economic Psychology 2005, 26, 862–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, M.; Inman, R.P.; Loeffler, C.; MacDonald, J.; Sieg, H. An experimental evaluation of notification strategies to increase property tax compliance: Free-riding in the city of brotherly love. Tax Policy and the Economy 2016, 30, 129–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucco, C.; Lenz, A.K.; Goldszmidt, R.; Valdivia, M. Face-to-face vs. virtual assistance to entrepreneurs: Evidence from a field experiment in Brazil. Economics Letters 2020, 188, 108922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, K.M.; Cappelen, A.W.; Sørensen, E.Ø.; Tungodden, B. You’ve got mail: A randomized field experiment on tax evasion. Management Science 2020, 66, 2801–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitaille, N.; House, J.; Mazar, N. Effectiveness of planning prompts on organizations’ likelihood to file their overdue taxes: A multi-wave field experiment. Management Science 2021, 67, 4327–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, N.; Ratto, M. The effects of penalty information on tax compliance: Evidence from a New Zealand field experiment. National Tax Journal 2018, 71, 547–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessing, D.J.; Elffers, H.; Robben, H.S.J.; Webley, P. Needy or greedy? The social psychology of individuals who fraudulently claim unemployment benefits. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 1993, 23, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamleitner, B.; Korunka, C.; Kirchler, E. Tax compliance of small business owners: A review. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ostapenko, N.; Williams, C.C. Determinants of entrepreneurs’ views on the acceptability of tax evasion and the informal economy in Slovakia and Ukraine: An institutional asymmetry approach. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 2016, 28, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, C.Y.L.; Fonseca, M.A.; Myles, G.D. Do students behave like real taxpayers in the lab? Evidence from a real effort tax compliance experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 2016, 124, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Slemrod, J. A general model of the behavioral response to taxation. International Tax and Public Finance 2001, 8, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and personality. New York: Harp and Row 1970.

- Chetty, R.; Finkelstein, A. Public economics. NBER Reporter 2020, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Slemrod, J. Tax compliance and enforcement. Journal of Economic Literature 2019, 57, 904–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities. Sage Publications 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, M.T.; Selmer, R.; Lindman, A.; Tverdal, A.; Menotti, A.; Thomsen, T.; DeBacker, G.; De Bacquer, D.; Tell, G.S.; Njolstad, I.; et al. Cardiovascular risk estimation in older persons: SCORE OP. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2016, 23, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinyan, A.; Asatryan, Z. Nudging for tax compliance: A meta-analysis. ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper 2019, 19-055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J.; Malézieux, A. 40 years of tax evasion games: A meta-analysis. Experimental Economics 2021, 24, 699–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, J.; Alao, H.; Brown, C.J.; Choudhary, S. Enriching the values of micro and small business research projects: Co-creation service provision as perceived by academic, business, and student. Studies in Higher Education 2016, 41, 560–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J.C.; Byrd, J.T. Social responsibility and the small business. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal 2013, 19, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, A.; Jiang, H. Corporate governance and financial reporting quality in China: A survey of recent evidence. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 2015, 24, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, V.A.; Bitzenis, A. Tax compliance of small enterprises in Greece. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 2016, 28, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, S.; Kogler, C.; Mittone, L.; Kirchler, E. Tax compliance depends on the voice of taxpayers. Journal of Economic Psychology 2016, 56, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazart, C.; Bonein, A. Reciprocal relationships in tax compliance decisions. Journal of Economic Psychology 2014, 40, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C.; Mittone, L.; Morreale, A. Tax morale and fairness in conflict: An experiment. Journal of Economic Psychology 2020, 81, 102314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fochmann, M.; Müller, N.; Overesch, M. Less cheating? The effects of prefilled forms on compliance behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology 2021, 83, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.T. The broken bridge of public finance: Majority rule, earmarked taxes, and social engineering. Public Choice 2020, 183, 315–338. [Google Scholar]

- Feld, L.P., & Frey, B.S. (2007). Tax compliance as the result of a psychological tax contract: The role of incentives and responsive regulation. *Law & Policy, 29*(1), 102–120. [CrossRef]

- Bargain, O.; Dolls, M.; Immervoll, H.; Neumann, D.; Peichl, A.; Pestel, N.; Siegloch, S. Tax policy and income inequality in the United States, 1979–2007. Economic Inquiry 2015, 53, 1061–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchler, E.; Hoelzl, E.; Wahl, I. Enforced versus voluntary tax compliance: The “slippery slope” framework. Journal of Economic Psychology 2008, 29, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassa, E.T. Factors influencing taxpayers to engage in tax evasion: Evidence from Woldia City administration micro, small, and large enterprise taxpayers. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2021, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, H.; Huber, L.R.; Van Praag, M.; Goslinga, S. The effect of a tax training program on tax compliance and business outcomes of starting entrepreneurs: Evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Business Venturing 2019, 34, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrancea, L.M.; Nichita, A.; De Agostini, R.; Batista Narcizo, F.; Forte, D.; de Paiva Neves Mamede, S.; Roux-Cesar, A.M.; Nedev, B.; Vitek, L.; Pántya, J.; et al. A self-employed taxpayer experimental study on trust, power, and tax compliance in eleven countries. Financial Innovation 2022, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiconco, R.I.; Gwokyalya, W.; Sserwanga, A.; Balunywa, W. Tax compliance behaviour of small business enterprises in Uganda. Journal of Financial Crime 2019, 26, 1117–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörrenberg, P.; Pfrang, A.; Schmitz, J. How to improve small firms’ payroll tax compliance? Evidence from a randomized field experiment. Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.; Kasper, M.; Enachescu, J.; Benk, S.; Budak, T.; Kirchler, E. Emotions and tax compliance among small business owners: An experimental survey. International Review of Law and Economics 2018, 56, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F. The shadow economy and work in the shadow: What do we (not) know? IZA Discussion Paper 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halla, M. Tax morale and compliance behavior: First evidence on a causal link. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 2012, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Plumley, A.H. The determinants of individual income tax compliance: Estimating the impacts of tax policy, enforcement, and IRS responsiveness. Harvard University 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorio, C.V.; D’Amuri, F. Workers’ tax evasion in Italy. Giornale degli economisti e Annali di economia 2005, 247–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lois, P.; Drogalas, G.; Karagiorgos, A.; Chlorou, A. Tax compliance during fiscal depression periods: The case of Greece. EuroMed Journal of Business 2019, 14, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, J.A. Criminal investigation enforcement activities and taxpayer noncompliance. Public Finance Review 2007, 35, 500–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.S.; Yoo, S.W.; Kim, J. Ambiguity, audit errors, and tax compliance. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics 2011, 18, 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Livernois, J.; McKenna, C.J. Truth or consequences: Enforcing pollution standards with self-reporting. Journal of Public Economics 1999, 71, 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, A.; Warren, R.S. Ambiguity about audit probability, tax compliance, and taxpayer welfare. Economic Inquiry 2005, 43, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanoglou, G.; Rapanos, V.T. Why do people evade taxes? New experimental evidence from Greece. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 2015, 56, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razen, M.; Kupfer, A. The effect of tax transparency on consumer and firm behavior: Experimental evidence. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 2023, 104, 101990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J.; Kasper, M. Using behavioural economics to understand tax compliance. Economic and Political Studies 2023, 11, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.B.; da Silveira, J.J.; Lima, G.T. To Comply or not to Comply: Persistent Heterogeneity in Tax Compliance and Macroeconomic Dynamics. FEA/USP 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann, S.; Lambsdorff, J.G. How income and tax rates provoke cheating—An experimental investigation of tax morale. Journal of Economic Psychology 2017, 63, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Questions | Objectives |

|---|---|

| RQ1: How do high tax rates, audit probabilities, and higher fines influence tax compliance? | Explore the effects of tax rates and the interplay between audit probabilities and fines on compliance levels, providing comprehensive mapping and categorization. |

| RQ2: How do gender differences and the size of an entity affect tax compliance behavior? | Investigate gender-specific compliance behaviors and the impact of a company’s size on its tax behavior, aiming to quantify differences and ascertain cause-and-effect relationships. |

| RQ3: What role does the legal status of a company play in its tax compliance and behavior? | Examine how different corporate legal statuses influence tax compliance rates, seeking to identify patterns that suggest lower or higher compliance levels among varying statuses. |

| Round | Tax Rate (%) | Probability of Audit (%) | Fine Multiplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | 5% | 10% | 1× Penalty |

| Round 2 | 47% | 5% | 1× Penalty |

| Round 3 | 25% | Unspecified | 2× Penalty |

| Compliance Rate | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.81 |

| Round 2 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.57 |

| Round 3 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.85 |

| Compliance rate | Gender | Sector | Legal Status | Assets | Danger | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliance rate | 1.0000 | |||||

| Gender | 0.2296* | 1.0000 | ||||

| (0.0001) | ||||||

| Sector | 0.0187 | 0.1792* | 1.0000 | |||

| (0.7488) | (0.0019) | |||||

| Legal Status | 0.2337* | 0.1412* | 0.0014 | 1.0000 | ||

| (0.0000) | (0.0148) | (0.9804) | ||||

| Assets | 0.2169* | 0.1901* | 0.0135 | 0.3852* | 1.0000 | |

| (0.0002) | (0.0010) | (0.8165) | (0.0000) | |||

| Danger | -0.2944* | -0.2193* | 0.0147 | -0.4367* | -0.3049* | 1.0000 |

| (0.0000) | (0.0001) | (0.8009) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).