Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Study Design

4. Variables

- Age

- Sex

- Comorbidities: High blood pressure (HBP), Diabetes mellitus (DM), Dyslipidemia (DL)

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

- Tumor size/volume

- Extra hepatic involvement

- Previous treatments (surgery, systemic therapy)

- Best Overall Response by image according to RECIST 1.1

- Tumor response according to RECIST 1.1 criteria every 1-2 months up to a minimum of 6 months of follow-up or death

- Progression-free survival up to a minimum of 6 months of follow-up or death

- Hepatic progression-free survival up to a minimum of 6 months of follow-up or death

- Overall survival up to a minimum of 6 months of follow-up or death

- Major and minor complications up to 90 days after the procedure

- Previous chemotherapy treatments

- Number of procedures (number of TARE-Y90 /DEBIRI treatments) per patient

- Performances and material related to the procedure per patient

- Treatment dose (TARE Y90: target site dose in Gy; DEBIRI: mg irinotecan)

- Hospital stays per patient (days)

- Length of stay in ICU per patient (hours), if applicable

- Complications per patient

- Follow-up visits

|

Socio demographic variables: Age Sex |

Clinical variables: Comorbidities: High blood pressure (HBP), Diabetes mellitus (DM), Dyslipidemia (DL) Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) Tumor size/volume Extra hepatic involvement Previous treatments (surgery, systemic therapy) |

|

Response variables: Best Overall Response by image according to RECIST 1.1 Tumor response according to RECIST 1.1 criteria every 1-2 months up to a minimum of 6 months of follow-up or death Progression-free survival up to a minimum of 6 months of follow-up or death Hepatic progression-free survival up to a minimum of 6 months of follow-up or death Overall survival up to a minimum of 6 months of follow-up or death Major and minor complications up to 90 days after the procedure |

Variables related to the resource consumption: Previous chemotherapy treatments Number of procedures (number of TARE-Y90 /DEBIRI treatments) per patient Performances and material related to the procedure per patient Treatment dose (TARE Y90: target site dose in Gy; DEBIRI: mg irinotecan) Hospital stays per patient (days) Length of stay in ICU per patient (hours), if applicable Complications per patient Follow-up visits |

5. Health Resource Consumption Analysis

6. Statistical Analysis

7. Results

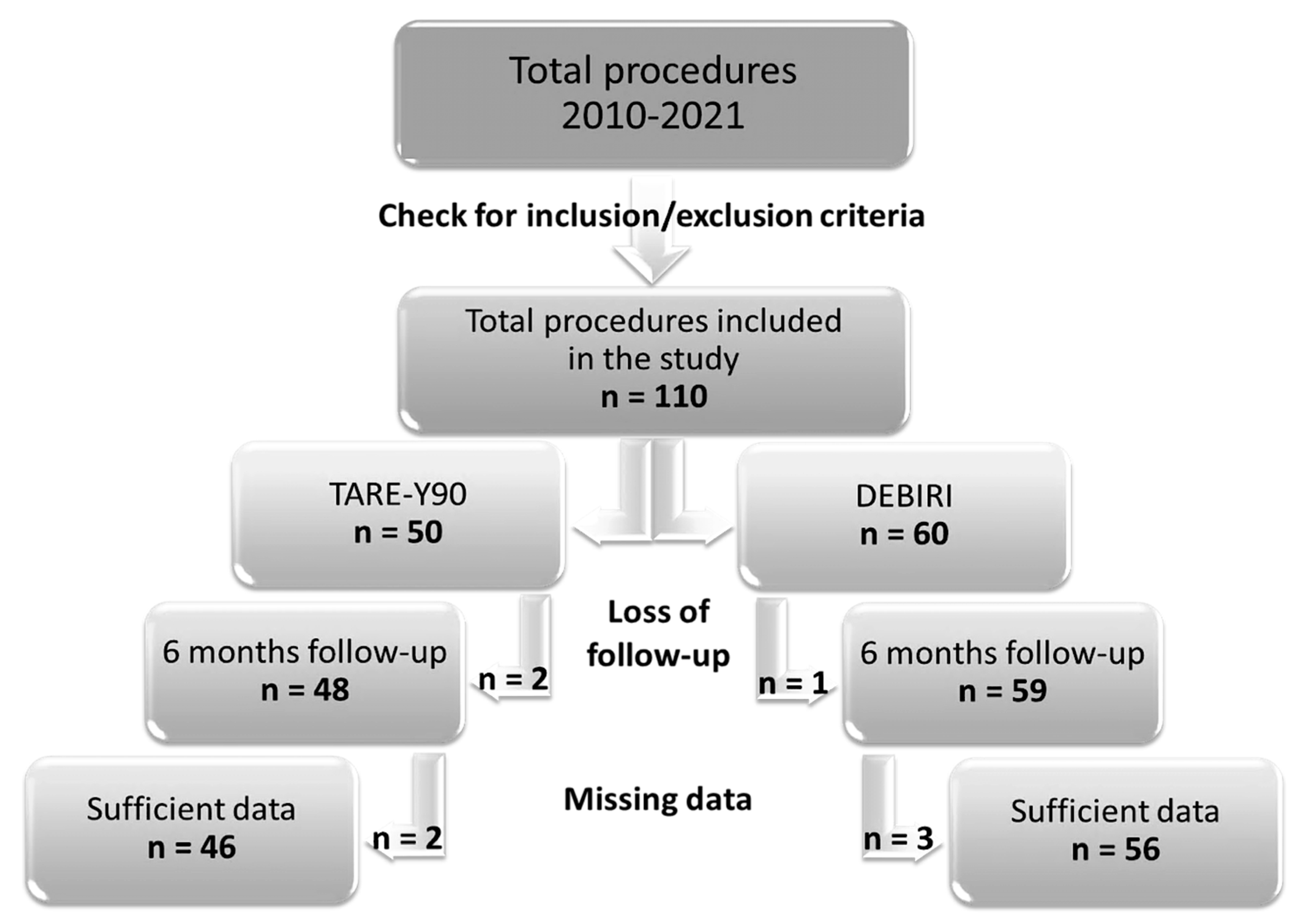

7.1. Retrospective Data Search: Subject Inclusion and Exclusion

| TARE-Y90 (N=46) | DEBIRI (N=56) | P | ||

| Age (years) | 62 ± 10 (34-77) | 62 ± 9 (45-79) | 0.89 (a) | |

| Sex | Men | 67 % (31) | 70 % (39) | 0.83 (c) |

| Women | 33 % (15) | 30 % (17) | ||

| ECOG | PS 0 | 72 % (33) | 66 % (38) | 0.56 (c) |

| PS 1 | 26 % (12) | 25 % (14) | ||

| PS 2 | 2 % (1) | 7 % (4) | ||

| HTA | 46 % (21) | 41 % (23) | 0.69 (c) | |

| DM | 13 % (6) | 16 % (9) | 0.78 (c) | |

| DL | 22 % (10) | 30 % (17) | 0.37 (c) | |

| PT localization | DX | 28 % (13) | 23 % (13) | 0.81 (c) |

| SX | 72 % (33) | 75 % (42) | ||

| DX; SX | 0 % (0) | 2 % (1) | ||

| PT vascular invasion | 50 % (23) | 28 % (16) | 0.30 (c) | |

| RAS mutation | 28 % (13) | 27 % (15) | 1.00 (c) | |

| BRAf | 2 % (1) | 4 % (2) | 1.00 (c) | |

| LM at PT diagnosis | 72 % (33) | 70 % (39) | 0.83 (c) | |

| Other M meanwhile the treatment | Lymph node | 12 % (6) | 12 % (7) | 1.00 (c) |

| Lung | 11 % (5) | 12 % (7) | ||

| Other location | 5 % (2) | 4 % (2) | ||

| No | 72 % (33) | 72% (40) | ||

| Ascites | 4 % (2) | 0 % (0) | 0.20 (c) | |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | 7 % (3) | 2 % (1) | 0.32 (c) | |

| Image test mode | TC | 80 % (37) | 84 % (47) | 0.78 (c) |

| PET-TC | 9 % (4) | 5 % (3) | ||

| RM | 7 % (3) | 9 % (5) | ||

| Echography | 4 % (2) | 2 % (1) | ||

| Nº LM | 4 ± 2 | 4 ± 4 | 0.61 (b) | |

| Size of target lesion | 45.7 ± 33.8 | 53.1 ± 35.1 | 0.30 (a) | |

| PET-CT pre-treatment | 61 % (28) | 39 % (22) | 0.05 (c)* | |

| LM localization | LHD | 50 % (23) | 34 % (19) | 0.14 (c) |

| LHI | 2 % (1) | 9 % (5) | ||

| Bi-lobar extension | 48 % (22) | 56 % (32) | ||

| Tumor burden | < 25 | 58 % (27) | 68 % (38) | 0.58 (c) |

| from 25 to 50 | 33 % (15) | 23 % (13) | ||

| > 50 | 9 % (4) | 9 % (5) | ||

| Pre-treatment CEA value | 286 ± 958 | 179 ± 557 | 0.61 (a) | |

| Previous treatments on PT | Primary tumor surgery | 78 % (36) | 96 % (54) | 0.006 (c)** |

| Systemic therapy | 96 % (44) | 100 % (56) | 0.20 (c) | |

| Surgery and/or Systemic therapy | 100 % (46) | 100 % (56) | 1.00 (c) | |

| Nº lines of systemic therapy | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 0.57 (a) | |

| Kind of first-line therapy | FOLFOX | 65 % (30) | 66 % (37) | 0.92 (c) |

| FOLFIRI | 15 % (7) | 18 % (10) | ||

| FOLFOX; FOLFIRI | 20 % (9) | 16 % (9) | ||

| Kind of previous treatments on LM | Surgery | 30 % (14) | 50 % (28) | 0.07 (c) |

| TACE | 2 % (1) | 9 % (5) | 1.00 (c) | |

| Ablation | 20 % (9) | 21 % (12) | 1.00 (c) | |

7.2. Response to Treatment

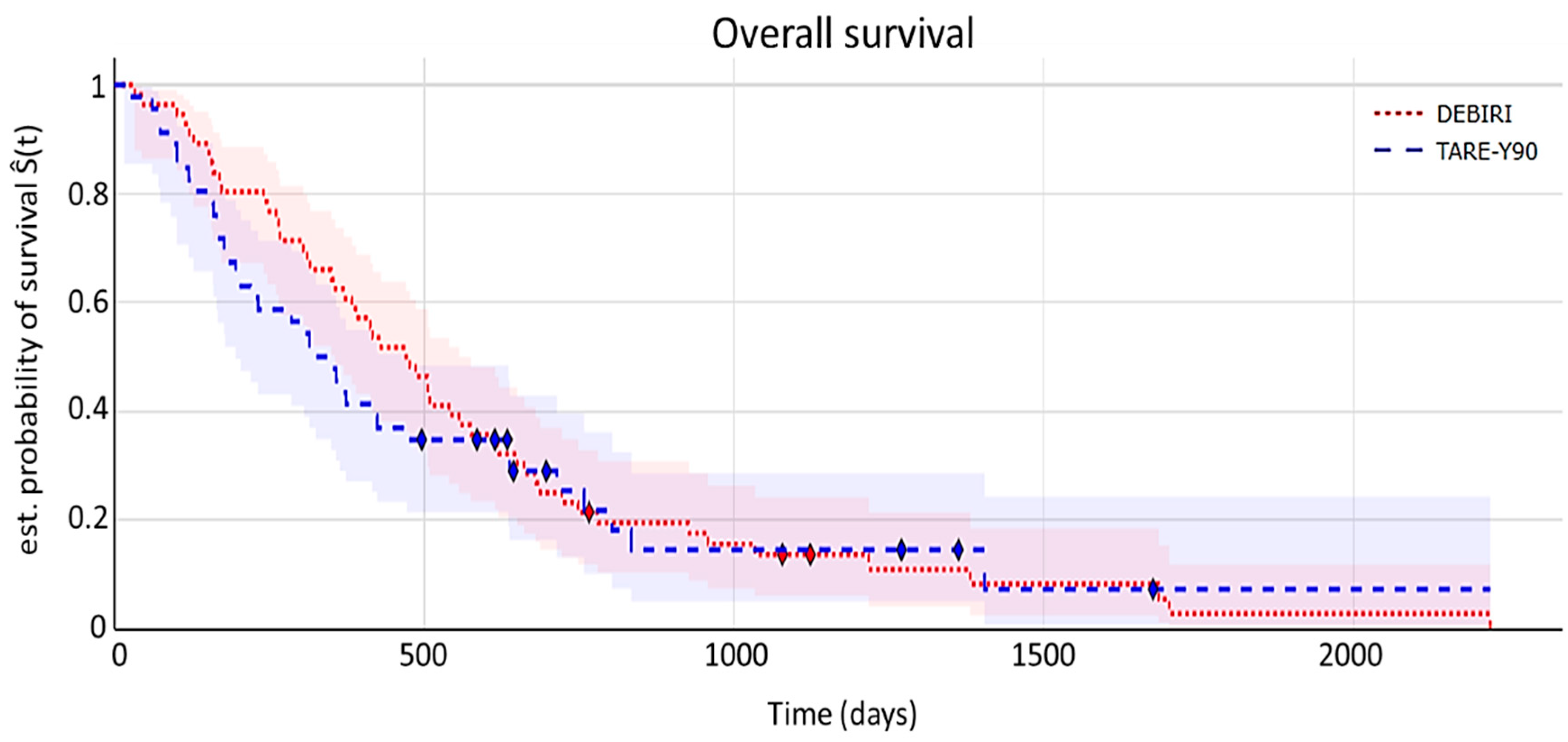

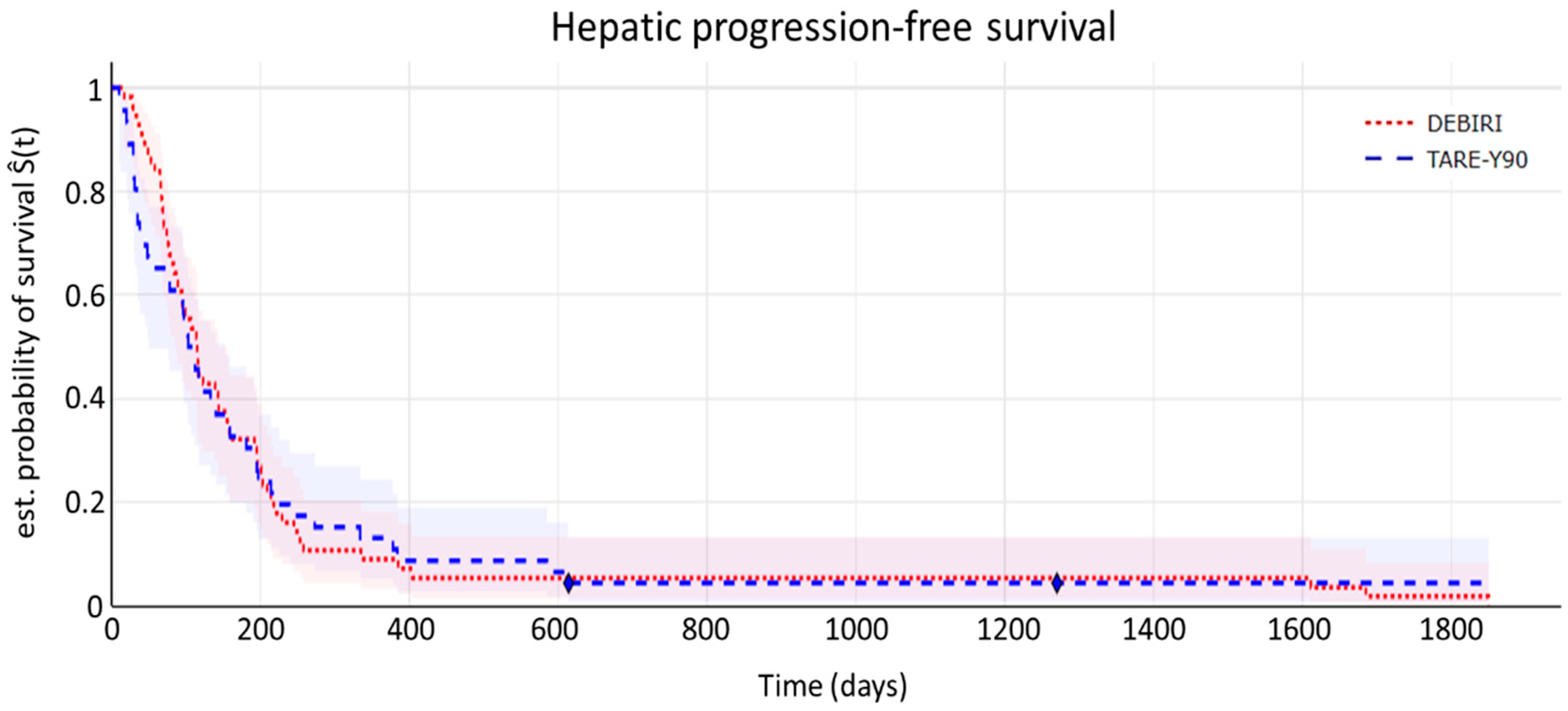

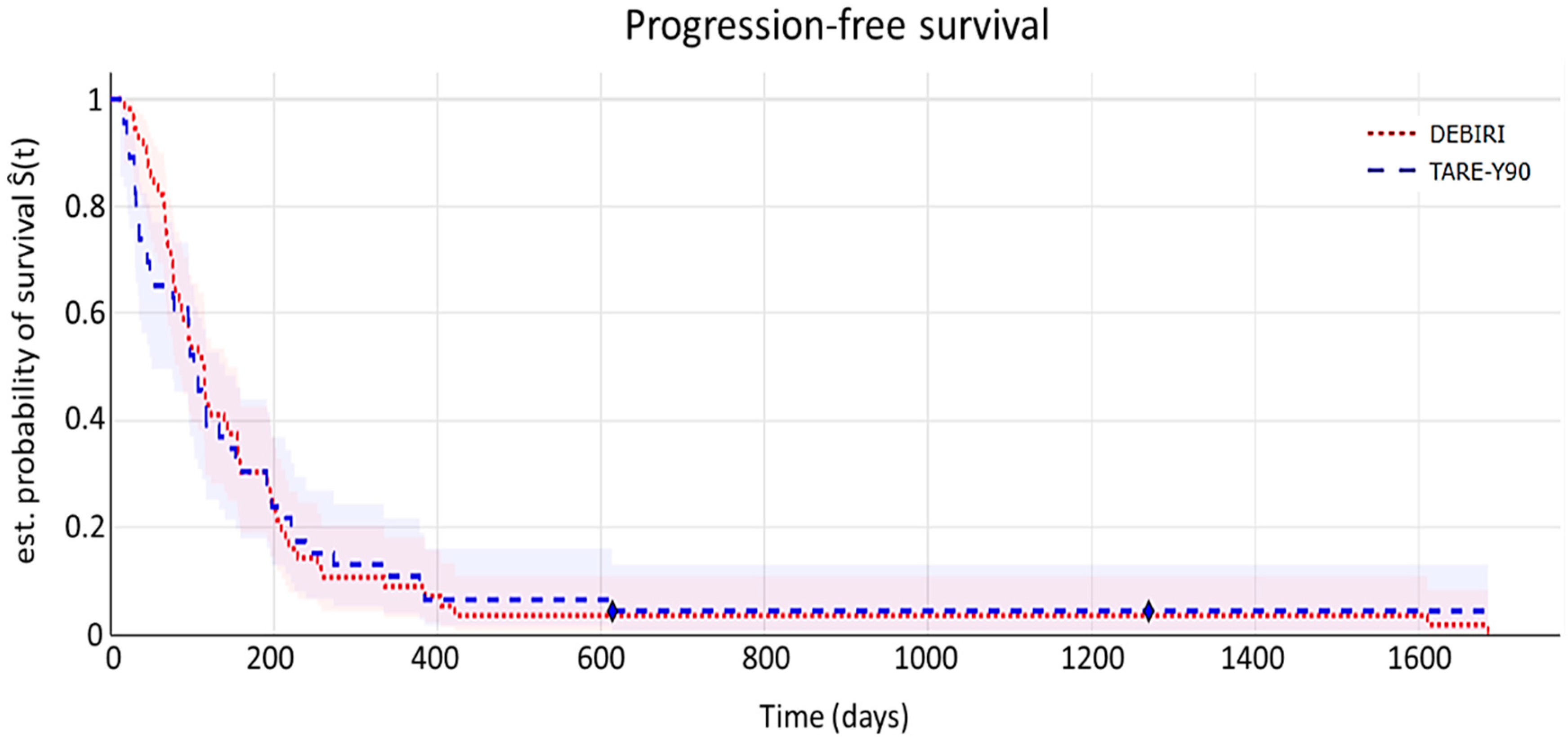

7.3. Time-to-Event Analyses

- a)

- Overall survival (OS)

- b)

- Hepatic progression-free survival (hPFS)

- c)

- Progression-free survival (PFS)

7.4. Health Resource Consumption Analysis

8. Discussion

Abbreviations

| ACs: | Autonomous Communities |

| CEA: | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CGP: | Clinical Good Practice |

| CR: | Complete response |

| DEBIRI: | Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) with irinotecan-preloaded particles |

| DL: | Dyslipidemia |

| DM: | Diabetes Mellitus |

| DP: | Disease progression |

| ECOG-PS: | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status |

| eCRF: | Electronic Case Report Form |

| HBP: | High blood pressure |

| HBV: | Hepatitis B Virus |

| HCV: | Hepatitis C Virus |

| HIV: | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| hPFS: | Hepatic progression-free survival |

| mCRC: | metastatic colorectal cancer |

| MSI: | microsatellite instability |

| NOR: | No overall response |

| LM: | Liver metastasis |

| OR: | Overall response |

| OS: | Overall survival |

| PFS: | Progression-free survival |

| PR: | Partial response |

| PPP: | Purchasing power parity. |

| PT: | Primary tumor |

| QoL: | Quality of Life |

| QALY: | Calidad ajustada a años de vida |

| RECIST: | Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| SD: | Stable disease |

| TACE: | transarterial chemoembolization |

| TARE: | transarterial radioembolization |

| TARE-Y90: | transarterial radioembolization with Y90 glass microspheres |

| Y90: | Yttrium-90 radioactive |

References

- Cancer Research 2019. Cancer Research UK. Bowel Cancer Statistics. 2020. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer#heading-Zero (accessed September 2020).

- IACR 2020. Cancer Today: International Association of Cancer Registries. Estimated number of deaths in 2020, worldwide, both sexes, all ages. 2021. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-table?v=2020&mode=cancer&mode_population=continents&population=900&populations=908&key=asr&sex=0&cancer=39&type=1&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=0&ages_group%5B%5D=17&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=1&include_nmsc_other=1#collapse-others (accessed 18th March 2021).

- ACS 2020. American Cancer Society. 2020. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html#:~:text=In%20the%20United%20States%2C%20colorectal,about%2053%2C200%20deaths%20during%202020.

- Safiri 2019. Safiri S, Sepanlou SG, Ikuta KS, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2019; 4(12): 913-33.

- Ponz de Leon 2004. Ponz de Leon M, Benatti P, Borghi F, et al. Aetiology of colorectal cancer and relevance of monogenic inheritance. Gut 2004; 53(1): 115.

- Macrae 2022. Macrae F. Colorectal cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors, and protective factors. Accessed at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/colorectal-cancer-epidemiology-risk-factors-and-protective-factors.

- Lykoudis 2014. Lykoudis PM, O'Reilly D, Nastos K, Fusai G. Systematic review of surgical management of synchronous colorectal liver metastases. BJS (British Journal of Surgery) 2014; 101(6): 605-12.

- Manfredi 2006. Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, Coatmeur O, Faivre J, Bouvier A-M. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 2006; 244(2): 254-9.

- Levy 2018. Levy J, Zuckerman J, Garfinkle R, et al. Intra-arterial therapies for unresectable and chemorefractory colorectal cancer liver metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB 2018; 20(10): 905-15.

- Wang 2020. Wang J, Li S, Liu Y, Zhang C, Li H, Lai B. Metastatic patterns and survival outcomes in patients with stage IV colon cancer: A population-based analysis. Cancer Medicine 2020; 9(1): 361-73.

- Riihimäki 2016. Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 29765-.

- Helling 2014. Helling TS, Martin M. Cause of death from liver metastases in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(2):501-6.

- SEOM 2018. Gómez-España MA, Gallego J, González-Flores E, Maurel J, Páez D, Sastre J, Aparicio J, Benavides M, Feliu J, Vera R. SEOM clinical guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (2018). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(1):46-54.

- Rodriguez-Fraile 2015. Rodríguez-Fraile M, Iñarrairaegui M. Radioembolización de tumores hepáticos con (90)Y-microesferas [Radioembolization with (90)Y-microspheres for liver tumors]. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2015;34(4):244-57.

- Salem 2010. Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, et al. Radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using Yttrium-90 microspheres: a comprehensive report of long-term outcomes. Gastroenterology 2010; 138(1): 52-64. [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy 2021. Mulcahy MF, Mahvash A, Pracht M, Montazeri AH, Bandula S, Martin RCG 2nd, Salem R; EPOCH Investigators. Radioembolization With Chemotherapy for Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Randomized, Open-Label, International, Multicenter, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021 ;39(35):3897-07.

- Fiorentini 2012: Hepatic arterial chemoembolization adopting DC Bead drug eluting bead loaded with irinotecan versus systemic therapy for colorectal cancer: a randomized study of efficacy and quality of life. AGH 2012; 3(1). March 2012.

- Vera R, Gonzalez-Flores E, Rubio C, Urbano J, Valero Camps M, Ciampi- Dopazo JJ, et al. Multidisciplinary management of liver metastases in patients with colorectal cancer: a consensus of SEOM, AEC, SEOR, SERVEI, and SEMNIM. Clin Transl Oncol 2020;22:647-62. [CrossRef]

- Kao YH, Tan EH, Ng CE, Goh SW. Clinical implications of the body surface area method versus partition model dosimetry for yttrium-90 radioembolization using resin microspheres: a technical review. Ann Nucl Med 2011; 25:455–461. [CrossRef]

- Mikell JK, Mahvash A, Siman W, Baladandayuthapani V, Mourtada F, Kappadath SC. Selective internal radiation therapy with yttrium-90 glass microspheres: biases and uncertainties in absorbed dose calculations between clinical dosimetry models. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016; 96:888–896. [CrossRef]

- Morán V, Prieto E, Sancho L, et al. Impact of the dosimetry approach onthe resulting 90Y radioembolization planned absorbed doses based on99mTc-MAA SPECT-CT: ¿is there agreement between dosimetry methods? EJNMMI Phys 2020; 7:1–22.

- Knight GM, Gordon AC, Gates V, et al. Evolution of Personalized Dosimetry for Radioembolization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023;34:1214–1225. [CrossRef]

- Bester L, Wasan H, Sangro B, Kennedy A, Pennington B, Sennfält K. Selec tive internal Radiotherapy (SIRT) using Resin Yttrium-90 Microspheres for Chemotherapy-Refractory metastatic colorectal Cancer: a UK cost-effec tiveness analysis. Value Health. 2013;16:A413. [CrossRef]

- Cosimelli M, Golfieri R, Pennington B, Sennfält K. Selective internal Radiotherapy (SIRT) using Resin Yttrium-90 Microspheres for Chemo therapy-Refractory metastatic colorectal Cancer: an italian cost-effec tiveness analysis. Value Health. 2013;16:A409. [CrossRef]

- Pennington B, Akehurst R, Wasan H, Sangro B, Kennedy AS, Sennfält K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of selective internal radiation therapy using yttrium-90 resin microspheres in treating patients with inoperable colorectal liver metastases in the UK. J Med Econ. 2015;18:797–804. [CrossRef]

- Brennan VK, Colaone F, Shergill S, Pollock RF. A cost-utility analysis of SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres versus best supportive care in the treatment of unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to chemotherapy in the UK. J Med Econ. 2020;23:1588–97. [CrossRef]

- Loveman E, Jones J, Clegg AJ, Picot J, Colquitt JL, Mendes D, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ablative therapies in the management of liver metastases: systematic review and economic evalu ation. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18. [CrossRef]

- Fusco F, Wolstenholme J, Gray A, Chau I, Dunham L, Love S, et al. Selective internal Radiotherapy (SIRT) in metastatic colorectal Cancer patients with liver metastases: preliminary primary Care Resource Use and Util ity results from the Foxfire Randomised Controlled Trial. Value Health. 2017;20:A445–6. [CrossRef]

- Dhir M, Zenati MS, Jones HL, Bartlett DL, Choudry MHA, Pingpank JF, et al. Effectiveness of hepatic artery infusion (HAI) Versus Selective Internal Radiation Therapy (Y90) for pretreated isolated unresectable colorectal liver metastases (IU-CRCLM). Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:550–7. [CrossRef]

- Bester L, Meteling B, Pocock N, Pavlakis N, Chua TC, Saxena A, et al. Radio embolization versus standard care of hepatic metastases: comparative retrospective cohort study of survival outcomes and adverse events in salvage patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol JVIR. 2012;23:96–105. [CrossRef]

- Gray B, Van Hazel G, Hope M, Burton M, Moroz P, Anderson J, et al. Randomised trial of SIR-Spheres plus chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy alone for treating patients with liver metastases from primary large bowel cancer. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2001;12:1711–20. https://doi. org/10.1023/a:1013569329846. [CrossRef]

- Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Gates VL, Nutting CW, Murthy R, Rose SC, et al. Research Reporting Standards for Radioembolization of hepatic malig nancies. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:265–78. [CrossRef]

- Karanicolas P, Beecroft JR, Cosby R, David E, Kalyvas M, Kennedy E, et al. Regional Therapies for Colorectal Liver Metastases: systematic review and clinical practice Guideline. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2021;20:20–8. [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy MF, Mahvash A, Pracht M, Montazeri AH, Bandula S, Martin RCG, et al. Radioembolization with Chemotherapy for Colorectal Liver Metastases: a randomized, Open-Label, International, Multicenter, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2021;JCO2101839. https:// doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.01839. [CrossRef]

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer with unilobar or bilobar metastatic liver disease (stage IV), unresectable and disease progression in the liver after several lines of chemotherapy (at least one). | Background of hepatic encephalopathy. |

| Clinically stable or resected primary tumor. | Pulmonary insufficiency or clinically evident chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. |

| Tumor replacement below 50% of the total volume of the liver. | Cirrhosis and portal hypertension. |

| Patients treated with TARE-Y90 (TheraSphere® Y-90 Glass Microspheres- Boston Scientific, Malborough, MA, US) | History of severe allergy or intolerance to contrast agents, narcotics, sedatives, or atropine that cannot be treated medically. |

| Patients treated with DEBIRI (DC Beads M1 70-150µ- Boston Scientific, Malborough, MA, US) | Contraindications to angiography or selective visceral catheterization such as bleeding or coagulopathy not controllable with common hemostatic agents (e.g.: device closure) |

| Life expectancy greater than 6 months at the start of locoregional therapy (minimum post-procedure follow-up time: 6 months or until death) | Intervention or compromise of the Ampulla of Vater. |

| ECOG 0-1 until the first treatment under scope. | Clinically obvious ascites (traces of ascites on imaging are acceptable) |

| Creatinine serum <2.0 mg/dL. | Hepatic toxicity due to previous cancer therapy that has not been resolved before the start of study treatment, if the researcher determines that the continuing complication will compromise the patient’s safe treatment. |

| Serum bilirubin up to 1.2 x upper limit. | Significant life-threatening extra-hepatic disease, including patients who are on dialysis, have unresolved diarrhea, have severe unresolved infections, including patients known to be HIV positive or to have acute HBV or HCV. |

| Albumin > 3.0 g/dL. | Confirmed extra-hepatic metastases. Limited and indeterminate extra-hepatic lesions are allowed in the lung and/or lymph nodes (up to 5 lesions in the lung, with each individual lesion <1 cm; any number of lymph nodes with each individual node <1.5 cm) |

| Neutrophil count > 1200/mm3 (1.2x109/L) | Previous treatment with liver radiotherapy. |

| Previous intra-arterial therapy directed at the liver, including transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) using irinotecan-loaded beads or TARE-Y90 therapy. |

|

| Treatment with biological agents within 28 days of receiving TARE-Y90 therapy. |

| TARE-Y90 (n = 46) |

DEBIRI (n = 56) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 4 % (1) | 12 % (9) | 0.06 |

| PR | 20 % (9) | 20 % (10) | |

| SD | 30 % (15) | 20 % (10) | |

| PD | 46 % (21) | 48 % (27) |

| TARE-Y90 (n = 46) |

DEBIRI (n = 56) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 24 % (10) | 52% (19) | 0.19 |

| NOR | 18% (36) | 48% (37) |

| Device/procedure/ health provider/time | Units per TARE-Y90 procedure | Units per DEBIRI procedure |

| Selective angiographic catheter | 1 | 0 |

| Simmons catheter | 1 | 0 |

| Guide | 1 | 0 |

| Introducer | 1 | 0 |

| Vascular puncture needle | 1 | 0 |

| Micro catheter | 1 | 0 |

| Vascular closure device | 1 | 0 |

| Coils | 1 | 0 |

| 99Tc-MAA | 1 | 0 |

| Pretreatment assessment with MAA | 1 | 0 |

| Dosimetry of patients treated with radioactive isotopes | 1 | 0 |

| Physician / specialist | 3 | 0 |

| Specialist technician | 1 | 0 |

| Nurse | 2 | 0 |

| Hospitalization (days) | 1 | 0 |

| Device/drug/health provider/time | Units per TARE-Y90 procedure | Units per DEBIRI procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Selective angiographic catheter | 1 | 1 |

| Simmons catheter | 1 | 1 |

| Guide | 1 | 1 |

| Introducer | 1 | 1 |

| Vascular puncture needle | 1 | 1 |

| Micro catheter | 1 | 1 |

| Vascular closure device | 1 | 1 |

| 90Y particles | 1 | 0 |

| DEBIRI particles | 0 | 2 |

| Irinotecan | 0 | 2 |

| - Gastroduodenal ulcer prophylaxis | 1 | 1 |

| - Anti-nausea prophylaxis | 0 | 1 |

| - Post-embolization syndrome prophylaxis | 1 | 1 |

| - Intravenous corticosteroid before treatment | 1 | 1 |

| - Cefuroxime | 1 | 1 |

| Physician / specialist | 3 | 1 |

| Specialist technician | 1 | 1 |

| Nurse | 2 | 2 |

| Procedure/hospitalization | Units per TARE-Y90 procedure | Units per DEBIRI procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Whole body positron tomography (PET-CT) | 1 | 0 |

| Dosimetry of patients treated with radioactive isotopes | 1 | 0 |

| Stay in intensive care unit (hours) | 0 | 2.20 |

| Hospitalization (days) | 1 | 2.56 |

| Concept | TARE-Y90 | DEBIRI |

| Average treatments per patient | 1.33 | 3.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).