Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

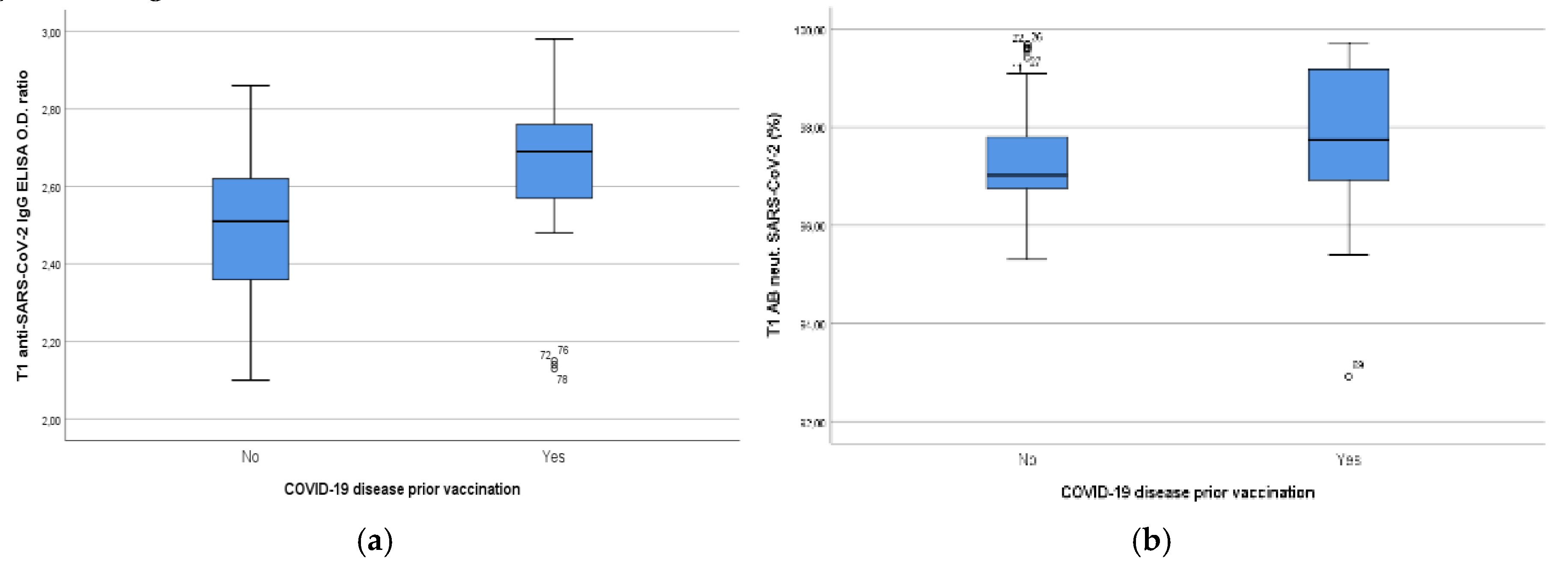

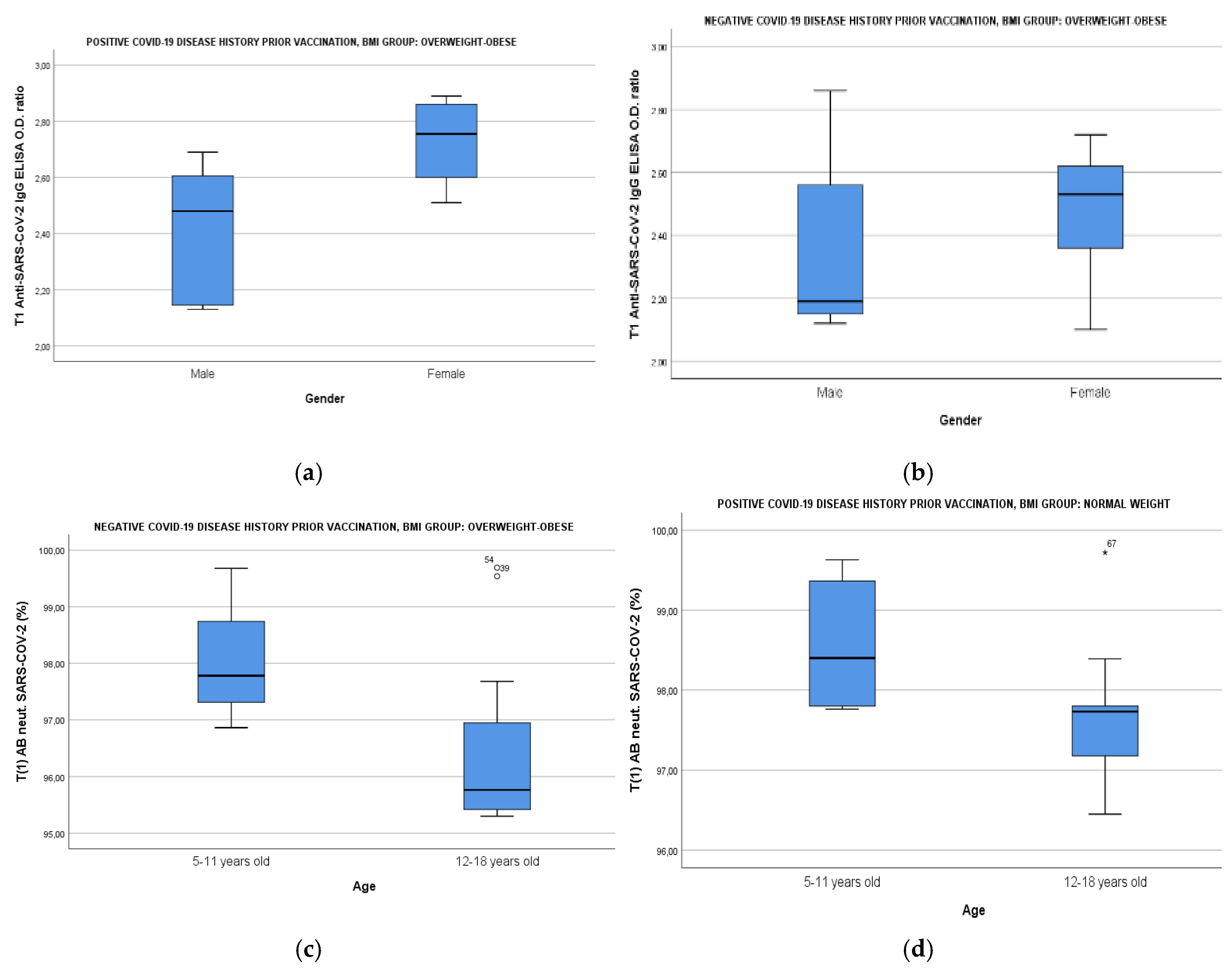

Background: The aim of the study is to evaluate whether increased Body Mass Index (BMI), biochemical and lifestyle parameters linked to obesity and smoke exposure disrupt immune responses of children and adolescents following vaccination with the mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine. Methods: Participants were assigned to receive two doses of the mRNA vaccine. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG and neutralizing antibodies (abs) were measured before vaccination (T0) and 14 days after the second dose (T1). BMI and biochemical parameters were evaluated at T0. A questionnaire on lifestyle characteristics was filled in. Results: IgG Optical Density (OD) ratio at T1 was lower in the overweight-obese group regardless of COVID-19 disease positive history [p=0.028 for the seronegative group, p=0.032 for the seropositive group]. Neutralizing abs were lower in overweightobese participants in the seronegative group at T1 [p=0.008]. HDL, Fasting Glucose/insulin Ratio (FGIR), C-Reactive Protein (CRP), HBA1c, uric acid and smoke exposure were significantly correlated with BMI [p=0.006, p<0.001, p<0.001, p=0.006, p=0.009, p<0.001, respectively]. The main biochemical parameters that were inversely correlated with IgG and neutralizing titers at T1 were uric acid [p=0.018, p=0.002], FGIR [p=0.001, p=0.008] and HBA1C [p=0.027, p=0.038], while smoke exposure negatively affected the humoral immune responses at T0 in the convalescent group [p=0.004, p=0.005]. Conclusions: Current data suggests that uric acid, Insulin Resistance (IR) and smoke exposure could adversely affect the immune responses in overweight-obese vaccinated children highlighting the need for actions needed for better protection of this specific subgroup.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Design and Criteria

2.3. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Binding Antibody and Biochemical Parameters

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Lifestyle Characteristics of Study Population

3.2. Results of Biochemical Profile of Study Population

- a)

- According to Center of Disease Control (CDC) physical activity key guidelines for children and adolescents, exercise should include vigorous-intensity, muscle- and bone- strengthening physical activity at least three times per week

- b)

- According to KIDMED index, a score of 0–3 reflects poor adherence to the Mediterranean diet, a score of 4–7 describes average adherence and a score of 8–12 good adherence

- c)

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Definition for Dyslipidemia in Children and Adolescents abnormal values were as followed: TCHOL≥200mg/dl, TGs≥ 100 mg/dL for ≤ 9 years old and ≥130 mg/dL for >10 years old, LDL-C≥130 mg/Dl, HDL-C<40 mg/dL and Lp(a) ≥30

- d)

- Normal ranges of CRP: 0-5 mg/l, HBA1C : 4.5-6.3% according to the Laboratory Manufacturer design

- e)

- According to literature abnormal values were considered when FGIR<7 both for prepubertal and pubertal participants & uric acid was >6.5mg/dl

3.3. a Results of Humoral Immune Responses of Study Population Divided by BMI

3.4. b Results of Humoral Immune Responses of Study Population According to BMI, Age & Gender

3.5. c Impact of Smoke Exposure, BMI, FGIR, HBA1c and Uric Acid on Humoral Immune Responses of Study Population

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| GROUP OF CHILDREN DIVIDED BY |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOCHEMICAL PARAMETERS | Negative Disease History | Positive Disease History | ||||

| Normal BMI | Overweight-obese | P -Value | Normal BMI | Overweight-obese | P-Value | |

|

HDL (MG/DL) MEAN (95% CI)I |

62.50(56.81-68.19) | 50.89 (45.79-56.00) | 0.005 | 60.24(55.86-64.62) | 58.31(51.48-65.15) | 0.581 |

| CRP (MG/L) MEAN RANK II | 18.25 | 30.33 | 0.01 | 13.12 | 21.13 | 0.017 |

|

URIC ACID (MG/DL) MEAN (95% CI) III |

4.28 (3.92-4.64) | 5.13 (4.61-5.66) | 0.002 | 4.05 (3.57-4.54) | 4.54 (3.81-5.28) | 0.382 |

| HBA1C (%) MEAN RANK II | 18.96 | 28.05 | 0.021 | 15.12 | 19.00 | 0.261 |

| FGIR MEAN RANK III | 29.94 | 14.33 | <0.001 | 20.88 | 12.88 | 0.017 |

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Definition for Dyslipidemia in Children and Adolescents abnormal values were as followed: TCHOL≥200mg/dl, TGs≥ 100 mg/dL for ≤ 9 years old and ≥130 mg/dL for >10 years old, LDL-C≥130 mg/Dl, HDL-C<40 mg/dL and Lp(a) ≥30

- Normal ranges of CRP: 0-5 mg/l, HBA1C : 4.5-6.3% according to the Laboratory Manufacturer design

- According to literature abnormal values were considered when FGIR4,5<6 both for prepubertal and pubertal participants & uric acid34,35 was >6.5mg/dl

Appendix B

| Variables in the Equation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | p-value | Exp(B) | 95% CI for EXP(B) | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| BMI GROUP | 0.48 | <0.001 | 1.61 | 1.28 | 2.03 | |

| Smoke exposure | -0.23 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 3.07 | |

| COVID-19 disease prior to vaccination | 0.42 | 0.56 | 1.53 | 0.36 | 6.43 | |

| Gender | 0.17 | 0.81 | 1.19 | 0.32 | 4.47 | |

| Age | 0.53 | 0.53 | 1.71 | 0.33 | 8.54 | |

| Constant | -11,37 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

References

- SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination elicits robust antibody responses in children. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Nov 23;14(672):eabn9237. [CrossRef]

- Pivonello, C.; Negri, M.; Pivonello, R.; et al. How May Obesity-Induced Oxidative Stress Affect the Outcome of COVID-19 Vaccines? Lesson Learned from the Infection. Stresses 2021, 1, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, Scott D.; Ovsyannikova, Inna G.; Poland, Gregory A. The weight of obesity on the human immune response to vaccination, Vaccine, Volume 33, Issue 36, 2015, Pages 4422-4429, ISSN 0264-410X. [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas, L.; García-Alvarez, A.; et al. “Nutrient adequacy and Mediterranean Diet in Spanish school children and adolescents” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2003) 57, Suppl 1, S35–S39. [CrossRef]

- Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med, 2016; 12, 785–786. [CrossRef]

- Piercy, KL.; Troiano, RP.; Ballard, RM.; et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018 Nov 20;320(19):2020-2028. [CrossRef]

- Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity. Pediatrics. 2023 Feb 1;151(2):e2022060640. [CrossRef]

- Ballerini, MG.; Bergadá, I.; Rodríguez, ME.; et al. Insulin level and insulin sensitivity indices among healthy children and adolescents. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2016 Aug 1;114(4):329-36. English, Spanish. [CrossRef]

- Jeyanathan, M.; Afkhami, S.; Smaill, F.; et al. Immunological considerations for COVID-19 vaccine strategies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020 Oct;20(10):615-632. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Muik, A.; Vogler, I.; et al. BNT162b2 vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies and poly-specific T cells in humans. Nature 595, 572–577 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Frenck, RW Jr.; Klein, NP.; Kitchin N.; et al. Safety, Immunogenicity, and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine in Adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jul 15;385(3):239-250. [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Berman, G.; Zhou, H.; et al. Evaluation of mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021 Dec 9;385(24):2241-2251. [CrossRef]

- Padoan, A.; Dall'Olmo, L.; Rocca, FD.; et al. Antibody response to first and second dose of BNT162b2 in a cohort of characterized healthcare workers. Clin Chim Acta. 2021 Aug;519:60-63. [CrossRef]

- Krammer, F.; Srivastava, K.; Alshammary, H.; et al. Antibody Responses in Seropositive Persons after a Single Dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 8;384(14):1372-1374. [CrossRef]

- Tregoning, JS.; Flight, KE.; Higham; et al. Progress of the COVID-19 vaccine effort: viruses, vaccines and variants versus efficacy, effectiveness and escape. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021 Oct;21(10):626-636. [CrossRef]

- Kurtovic, L.; Beeson, JG. Complement Factors in COVID-19 Therapeutics and Vaccines. Trends Immunol. 2021 Feb;42(2):94-103. [CrossRef]

- Jay, C.; Adland, E.; Csala, A.; et al. (2023) Age- and sex- specific differences in immune responses to BNT162b2 COVID-19 and live-attenuated influenza vaccines in UK adolescents. Front. Immunol. 14:1248630. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2019), Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2017), Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, I.; Delle Cave, F.; Guarracino, C.; et al. Obesity and COVID-19 in children and adolescents: a double pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2022 Jun 6;93(S3):e2022195. [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, PA.; Paich, HA.; Handy, J.; et al. Obesity is associated with impaired immune response to influenza vaccination in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012 Aug;36(8):1072-7. [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Chen, XF.; Shen, C.; et al. Hepatitis B vaccine response in obesity: A meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2016 Sep 14;34(40):4835-41. [CrossRef]

- Eliakim, A.; Schwindt, C.; Zaldivar, F.; et al. Reduced tetanus antibody titers in overweight children. Autoimmunity. 2006 Mar;39(2):137-41. [CrossRef]

- Pellin, R.; Venuti, A.; Pimpinelli, F.; et al. Initial observations on age, gender, BMI and hypertension in antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine. EClinicalMedicine. 2021 Jun;36:100928. [CrossRef]

- Lumeng, CN.; Bodzin, JL.; Saltiel, AR.; et al. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007 Jan;117(1):175-84. [CrossRef]

- Manna, P.; Jain, SK. Obesity, Oxidative Stress, Adipose Tissue Dysfunction, and the Associated Health Risks: Causes and Therapeutic Strategies. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2015 Dec;13(10):423-44. [CrossRef]

- Bakadia, BM. Boni, BOO.; Ahmed, AAQ.; et al. The impact of oxidative stress damage induced by the environmental stressors on COVID-19. Life Sci. 2021 Jan 1;264:118653. [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Chakraborty, R.; Kalita, P.; et al. Diabetes mellitus and COVID-19: Understanding the association in light of current evidence. World J Clin Cases. 2021 Oct 6;9(28):8327-8339.

- Ruiz-Ramie, JJ.; Barber, JL.; Sarzynski, MA. Effects of exercise on HDL functionality. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2019 Feb;30(1):16-23. [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, Y.; Nishizawa, H.; Tochino, Y.; et al. Uric acid secretion from adipose tissue and its increase in obesity. J Biol Chem. 2013 Sep 20;288(38):27138-27149. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, KJ.; Tzameli, I.; Pissios, P.; et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase is a regulator of adipogenesis and PPARgamma activity. Cell Metab. 2007 Feb;5(2):115-28. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, W.; McRae, S.; Marek, G.; et al. Hyperuricemia as a mediator of the proinflammatory endocrine imbalance in the adipose tissue in a murine model of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2011 Apr;60(4):1258-69. [CrossRef]

- Morales, F.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Leon, MJ.; et al. Effects of Malnutrition on the Immune System and Infection and the Role of Nutritional Strategies Regarding Improvements in Children's Health Status: A Literature Review. Nutrients. 2023 Dec 19;16(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, WD. Abnormal serum uric acid levels in children. J Pediatr. 1996 Jun;128(6):731-41. [CrossRef]

- Kubota, M. Hyperuricemia in Children and Adolescents: Present Knowledge and Future Directions. J Nutr Metab. 2019 May 2;2019:3480718. [CrossRef]

- Carsetti, R.; Quintarelli, C.; Quinti, I.; et al. The immune system of children: the key to understanding SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility? Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 Jun;4(6):414-416. [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, MM.; Zeitler, PS. Insulin Resistance of Puberty. Curr Diab Rep. 2016 Jul;16(7):64. [CrossRef]

- Klein, SL.; Marriott, I.; Fish, EN. Sex-based differences in immune function and responses to vaccination. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015 Jan;109(1):9-15. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Trinh, TA.; Hallam, KT.; et al. The links between parental smoking and childhood obesity: data of the longitudinal study of Australian children. BMC Public Health. 2024 Jan 2;24(1):68. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.; Ponticelli, D.; Agüero, F.; et al. Does smoking have an impact on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines? Evidence from the VASCO study and need for further studies. Public Health. 2022 Feb;203:97-99.

- Pedersen, KM.; Çolak, Y.; Ellervik, C.; et al. Smoking and Increased White and Red Blood Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019 May;39(5):965-977. [CrossRef]

- Vardavas, CI.; Plada, M.; Tzatzarakis, M.; et al. Passive smoking alters circulating naïve/memory lymphocyte T-cell subpopulations in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010 Dec;21(8):1171-8. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Liang, CL.; Liu, H.; et al. Impacts of cigarette smoking on immune responsiveness: Up and down or upside down? Oncotarget. 2017 Jan 3;8(1):268-284. [CrossRef]

| BMI GROUPa | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal-weight | Overweight-obese | ||||

| Gender | Female | Number (%) | 22 (55) | 18 (45) | 0.921 |

| Age(years) | 5-11 | Number (%) | 15 (51.7) | 14 (48.3) | 0.713 |

| 12-18 | Number (%) | 28 (56) | 22 (44) | ||

| Smoking Score | 1 | Number (%) | 29 (72.5) | 11 (27.5) | <0.001 |

| 0 | Number (%) | 11 (28.2) | 28 (71.8) | ||

| Exercise Scoreb | 0 | Number (%) | 14 (43.8) | 18 (56.3) | 0.212 |

| 1 | Number (%) | 29 (61.7) | 18 (38.3) | ||

| Kidmed Scorec | Poor (0-3) | Number (%) | 6 (50) | 6 (50) | 0.751 |

| Moderate (4-7) | Number (%) | 24 (58.5) | 41 (41.5) | ||

| Good (≥8) | Number (%) | 13 (50) | 13 (50) | ||

| BIOCHEMICAL PARAMETERS | TCHOL (mg/dl) MEAN (95% CI)d | 150.19(144.65-155.72) | 150.23(142.41-158.05) | 0.924 | |

| TG (mg/dl) MEAN RANKd | 33.73 | 36.59 | 0.135 | ||

| LDL (mg/dl) MEAN (95% CI)d | 81.82(76.54-87.11) | 88.89(81.57-96.20) | 0.269 | ||

| HDL (mg/dl) MEAN (95% CI)d | 61.60(57.87-65.34) | 54.29(50.13-58.44) | 0.006 | ||

| Lp(A) (mg/dl) MEAN RANKd | 38.23 | 41.06 | 0.581 | ||

| CRP (mg/l) MEAN RANKe | 30.79 | 51.00 | <0.001 | ||

| Uric acid (mg/dl) MEAN (95% CI)f | 4.19 (3.91-4.47) | 4.85 (4.42-5.28) | 0.009 | ||

| HBA1C (%) MEAN RANKe | 33.36 | 46.67 | 0.006 | ||

| FGIR MEAN RANKf | 50.51 | 26.65 | <0.001 | ||

| Number | anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG ELISA OD ratio |

SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing AB (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling | T0 ΜΕAΝ (95%CI) | T1 ΜΕAΝ (95%CI) | T0 MEDIAN (IQR) | T1 ΜΕDIAΝ (IQR) | |

| Negative Disease history prior to immunization | |||||

| BMI | |||||

| Normal-weight | 26 | 0.09 (0.06-0.12) | 2.55 (2.50-2.60) | 2.60 (1.67) | 97.51 (2.22) |

| Overweight-obese | 20 | 0.08 (0.45-0.12) | 2.42 (2.31-2.52) | 2.43 (1.23) | 96.34 (2.28) |

| P-value | 0.60 | 0.028 | 0.88 | 0.008 | |

| Positive Disease history prior to immunization | |||||

| BMI | |||||

| Normal-weight | 17 | 1.50 (1.22-1.78) | 2.73 (2.66-2.80) | 50.92 (44.16) | 97.8 (1.55) |

| Overweight-obese | 16 | 1.07 (0.79-1.36) | 2.57 (2.44-2.70) | 15.45 (36.86) | 96.93 (3.96) |

| P-value | 0.026 | 0.032 | <0.001 | 0.07 | |

| COVID-19 DISEASE HISTORY PRIOR VACCINATION | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Negative | Independent Variables | Positive | ||

| Beta (95% CI) | P-value | Beta (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| T0 anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG | - | - | - | Smoke exposure | -0.55 (-0.91;-0.20) | 0.004(R2: 0.22) |

| Τ0SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing (%) | - | - | - | Smoke exposure | -25.61 (-42.77; -8.44) | 0.005(R2: 0.21) |

| T1 anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG | BMI | -0.02 (-0.03; -0.01) | 0.002(R2: 0.19) | BMI | -0.03 (-0.04; -0.02) | <0.001(R2: 0.45) |

| Uric acid | -0.06(-0.114; -0.011) | 0.018 (R2: 0.11) | FGIR | -0.24 (-0.38; -0.11) |

0.001 (R2: 0.44) |

|

| HBA1c | -0.17 (-0.33; -0.02) | 0.027(R2: 0.44) | ||||

| Τ1 SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing (%) | BMI | -0.17(-0.25; -0.11) | <0.001(R2: 0.30) | BMI | -0.15 (-0.26; -0.04) | 0.009(R2: 0.30) |

| FGIR | -1.52 (-2.62; -0.42) |

0.008 (R2: 0.35) |

||||

| Uric acid | -0.59(-0.95; -0.23) | 0.002 (R2: 0.19) | HBA1c | -1.36 (-2.63; -0.10) | 0.038(R2: 0.35) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).