Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Brief History of Antibiotics

2. Antibiotic Resistance

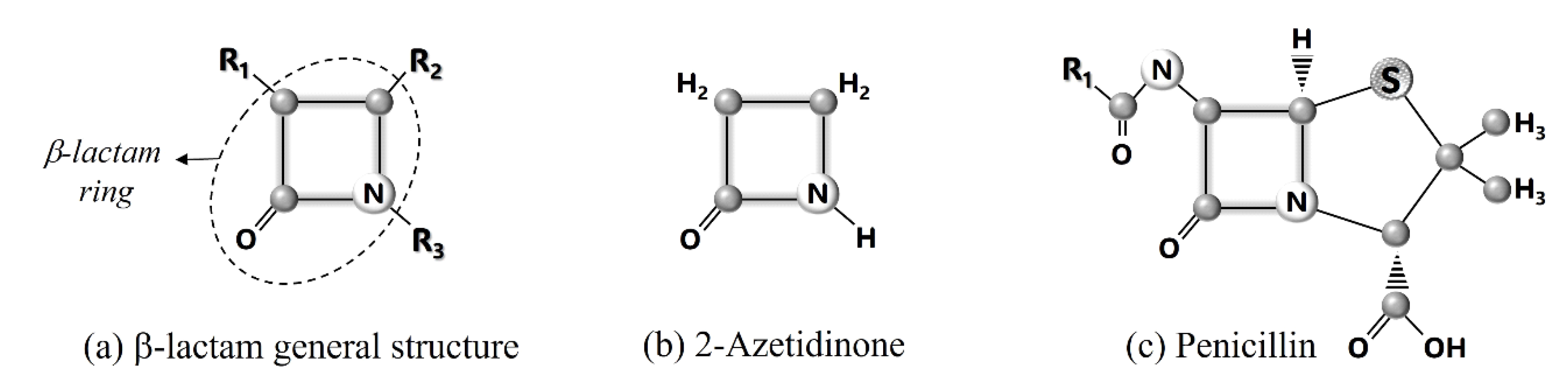

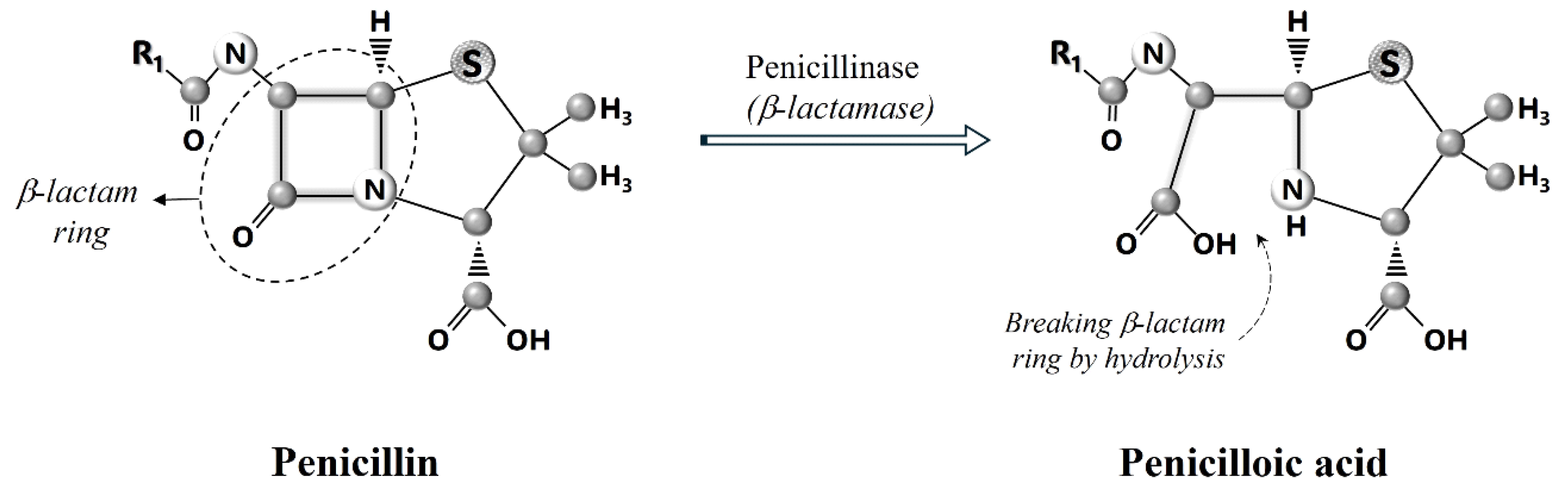

4. How β-Lactam Antibiotics Work?

5. ESBLs

6. Classifications of ESBLs

7. Genetics of ESBLs

8. ESBLs Mutations in Kuwait

References

- Lobanovska, M.; Pilla, G. Penicillin’s Discovery and Antibiotic Resistance: Lessons for the Future? Yale J Biol Med. 2017, 90, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, M.I.; Truman, A.W.; Wilkinson, B. Antibiotics: past, present and future. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019, 51, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, A.R.; Halls, G.; Hu, Y. Novel classes of antibiotics or more of the same? Br J Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 184–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner J, Muraoka A, Bedenbaugh M, Childress B, Pernot L, Wiencek M, et al. The Chemical Relationship Among Beta-Lactam Antibiotics and Potential Impacts on Reactivity and Decomposition. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 807955. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, E.P.; Chain, E. An enzyme from bacteria able to destroy penicillin. 1940. Rev Infect Dis. 1988, 10, 677–678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rammelkamp, T. Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to the action of penicillin. Exp Biol Med. 1942, 51, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminov, R.I. A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Front Microbiol. 2010, 1, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, L.A.; Dermody, T.S. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Arch Intern Med. 1991, 151, 886–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reygaert, W.C. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, O.B.; Irwin, A.; Berthe, F.C.J.; Le Gall, F.G.; Marquez, P.V. Drug-resistant infections : a threat to our economic future (Vol. 2): final report (English). HNP/Agriculture Global Antimicrobial Resistance Initiative Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/323311493396993758/final-report.

- Hodgkin, D.C. The X-ray analysis of the structure of penicillin. Adv Sci. 1949, 6, 85–9. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham EP, Chain E, Fletcher CM, Gardner AD, Heatley NG, Jennings MA, et al. Further observations on penicillin. Lancet 1941, 238, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. beta-lactams and beta-lactamase inhibitors: an overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2016; 6, a025247. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim S, Kwon Y, Kim Y, Park H, Kwak K, et al. Structural Insights for β-Lactam Antibiotics. Biomol Ther 2023, 31, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes R, Amador P, Prudêncio C. β-Lactams chemical structure, mode of action and mechanisms of resistance. Rev Med Microbiol. 2013, 24, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Jacoby, G.A. Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drawz, S.M.; Bonomo, R.A. Three decades of beta-lactamase inhibitors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010, 23, 160–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, S.; Fatima, J.; Shakil, S.; Rizvi, S.M.; Kamal, M.A. Antibiotic resistance and extended spectrum beta-lactamases: Types, epidemiology and treatment. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2015, 22, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K. Classification for β-lactamases: historical perspectives. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2023, 21, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D.L.; Bonomo, R.A. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005, 18, 657–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambler, R.P. The structure of beta-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1980, 289, 321–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bush, K.; Jacoby, G.; Medeiros, A. A functional classification scheme for b-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 1211–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Fisher, J.F. Epidemiological expansion, structural studies, and clinical challenges of new b-lactamases from gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011, 65, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N.; Turton, J.F.; Livermore, D.M. Multi resistant gram negative bacteria: the role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 736–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanheira, M.; Simner, P.J.; Bradford, P.A. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: an update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021, 3, dlab092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, N.; Kontomichalou, P. Penicillinase synthesis controlled by infectious R factors in Enterobacteriaceae. Nature. 1965, 208, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitton, J.S. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Ergeb Physiol. 1972, 65, 15–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, G.A.; Bush, K. Amino acid sequences for TEM, SHV and OXA extended-spectrum and inhibitor resistant β-lactamases: Lahey Clinic; 1997. Available from: http://www.lahey.org/Studies/.

- NCBI National center for biotechnology information. Pathogen Detection Reference Gene Catalog. cited 2023 Feb 24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/refgene/#.

- Dashti, A.A.; Jadaon, M.M.; Amyes, S.G. Retrospective study of an outbreak in a Kuwaiti hospital of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae possessing the new SHV-112 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase. J Chemother. 2010, 22, 335–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashti, A.A.; Vali, L.; Jadaon, M.M.; El-Shazly, S. The emergence of a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolate harboring a novel SHV-122 enzyme is a serious threat for hospitalised patients. 16th HSC Poster Conference 2011, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, Kuwait, May 3-5, 2011. 3 May.

- Dashti, A.A.; Jadaon, M.M.; Gomaa, H.H.; Noronha, B.; Udo, E.E. Transmission of a Klebsiella pneumoniae clone harbouring genes for CTX-M-15-like and SHV-112 enzymes in a neonatal intensive care unit of a Kuwaiti hospital. J Med Microbiol. 2010, 59 Pt 6, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, P.W. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella spp. Br J Biomed Sci. 2000, 57, 226–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alajmi, R.Z.; Alfouzan, W.A.; Mustafa, A.S. The Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae among Neonates in Kuwait. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zowawi HM, Balkhy HH, Walsh TR, Paterson DL. β-Lactamase production in key gram-negative pathogen isolates from the Arabian Peninsula. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013, 26, 361–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashti, A.A.; West, P.W. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolated in the Al-Amiri Hospital in 2003 and compared with isolates from the Farwania hospital outbreak in 1994-96 in Kuwait. J Chemother. 2007, 19, 271–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattoir, V.; Poirel, L.; Rotimi, V.; Soussy, C.J.; Nordmann, P. Multiplex PCR for detection of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance qnr genes in ESBL-producing enterobacterial isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007, 60, 394–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotimi, V.O.; Jamal, W.; Pal, T.; Sovenned, A.; Albert, M.J. Emergence of CTX-M-15 type extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Salmonella spp. in Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. J Med Microbiol. 2008, 57 Pt 7, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Sweih, N.; Salama, M.F.; Jamal, W.; Al Hashem, G.; Rotimi, V.O. An outbreak of CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in an intensive care unit of a teaching hospital in Kuwait. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011, 29, 130–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hashem, G.; Al Sweih, N.; Jamal, W.; Rotimi, V.O. Sequence analysis of bla(CTX-M) genes carried by clinically significant Escherichia coli isolates in Kuwait hospitals. Med Princ Pract. 2011, 20, 213–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnin RA, Rotimi VO, Al Hubail M, Gasiorowski E, Al Sweih N, Nordmann P, et al. Wide dissemination of GES-type carbapenemases in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in Kuwait. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 183–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vali, L.; Dashti, A.A.; Jadaon, M.M.; El-Shazly, S. The emergence of plasmid mediated quinolone resistance qnrA2 in extended spectrum β-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in the Middle East. Daru. 2015, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sweih, N.; Jamal, W.; Mokaddas, E.; Habashy, N.; Kurdi, A.; Mohamed, N. Evaluation of the in vitro activity of ceftaroline, ceftazidime/avibactam and comparator antimicrobial agents against clinical isolates from paediatric patients in Kuwait: ATLAS data 2012-19. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021, 3, dlab159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghnia, O.H.; Al-Sweih, N.A. Whole Genome Sequence Analysis of Multidrug Resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains in Kuwait. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Findlay, J.; Sierra, R.; Raro, O.H.F.; Aires-de-Sousa, M.; Andrey, D.O.; Nordmann, P. Plasmid-mediated fosfomycin resistance in Escherichia coli isolates of worldwide origin. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2023, 35, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redha, M.A.; Al Sweih, N.; Albert, M.J. Multidrug-Resistant and Extensively Drug-Resistant Escherichia coli in Sewage in Kuwait: Their Implications. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Years of testing | Bacteria | Hospital in Kuwait | ESBL genes reported (percentage not shown) | Reference (publication year) |

| 2003 1994 to 1996 |

E. coli | Al-Amiri Al-Farwania |

TEM & SHV (general) | 37 (2007) |

| 2002 to 2004 | E. cloacae, C. freundii | Mubarak Al-Kabir |

SHV-12, VEB-1b | 38 (2007) |

| 2003 to 2006 | Salmonella spp. | Mubarak Al-Kabir, Infectious Diseases H. |

TEM, CTX-M-15 | 39 (2008) |

| 2005 to 2006 | K. pneumoniae | Al-Jahra | TEM-1, SHV-112, CTX-M-15-like |

33 (2010) |

| 2010 | K. pneumoniae | Al-Amiri | SHV-112 | 31 (2010) |

| 2008 | K. pneumoniae | Mubarak Al-Kabeer | TEM-1, CTX-M-15 | 40 (2011) |

| 2008 | E. coli | Mubarak Al-Kabeer, Al-Amiri, Al-Sabah, Al-Adan, Al-Jahra, Ibn Sina, Al-Farwaniya, Maternity |

TEM, SHV (general), CTX-M (-15, -14, -14b, TOHO-1) |

41 (2011) |

| 2007 to 2008 | A. baumannii | Mubarak Al-Kabeer, Al-Sabah, Al-Adan, Al-Jahra, Al-Babtain, Al- Razi |

GES-11, GES-14, OXA-23 OXA-51-like (-74, -66, -71, -98) |

42 (2013) |

| Non-specified | K. pneumoniae | Al-Amiri, Al-Adan, Al-Ahmadi (Kuwait Oil Company H.) |

TEM-1, SHV, CTX-M (-2, -15) |

43 (2015) |

| 2012 to 2019 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae | 3 non-specified hospitals | CTX-M-15 | 44 (2021) |

| 2020 to 2021 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae | Mubarak Al-Kabeer, Ibn Sina, Al-Babtain |

TEM-1, SHV-11/-12, CTX-M-15, OXA-1/-48, KPC-2/-29, CMY-4/-6, OKP-B, ACT, EC. |

45 (2022) |

| 2020 | Enterobacteriaceae spp. (mostly E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp.) | Al-Farwaniya | TEM, SHV & CTX-M (general) | 35 (2023) |

| 2017 to 2022 | E. coli | Non-specified | CMY-2 | 46 (2023) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).