Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

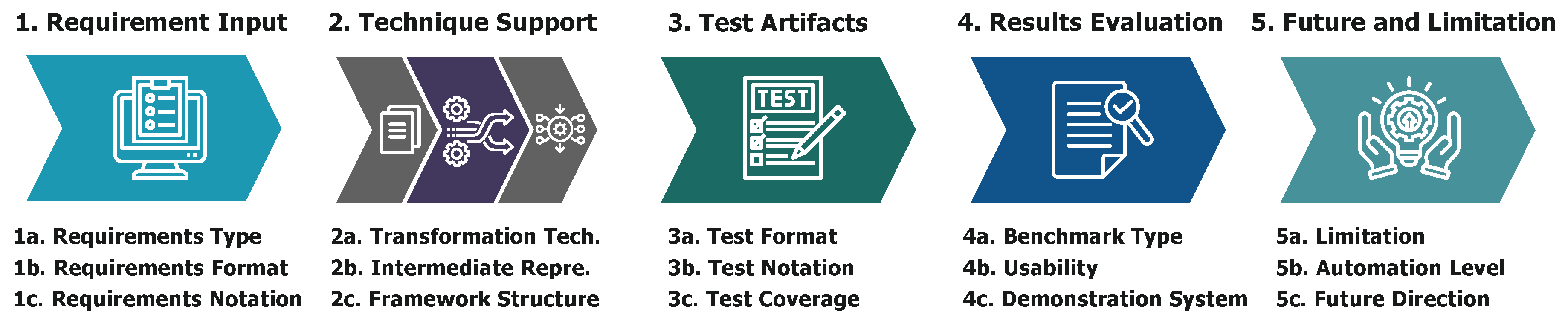

1. Introduction

- RQ1. What are the input configurations, formats, and notations used in the requirements in requirements-driven automated software testing?

- RQ2. What are the frameworks, tools, processing methods, and transformation techniques used in requirements-driven automated software testing studies?

- RQ3. What are the test formats and coverage criteria used in the requirements-driven automated software testing process?

- RQ4. How do existing studies evaluate the generated test artifacts in the requirements-driven automated software testing process?

- RQ5. What are the limitations and challenges of existing requirements-driven automated software testing methods in the current era?

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Requirements Engineering

2.2. Automated Software Testing and Requirements Engineering

2.3. REDAST Secondary Studies

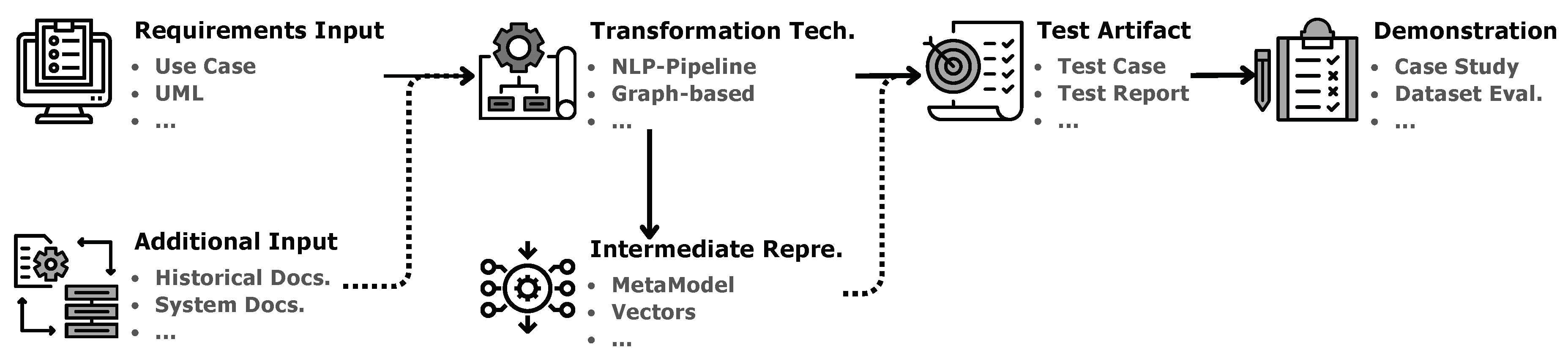

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Questions

3.2. Searching Strategy

3.2.1. Search String Formulation

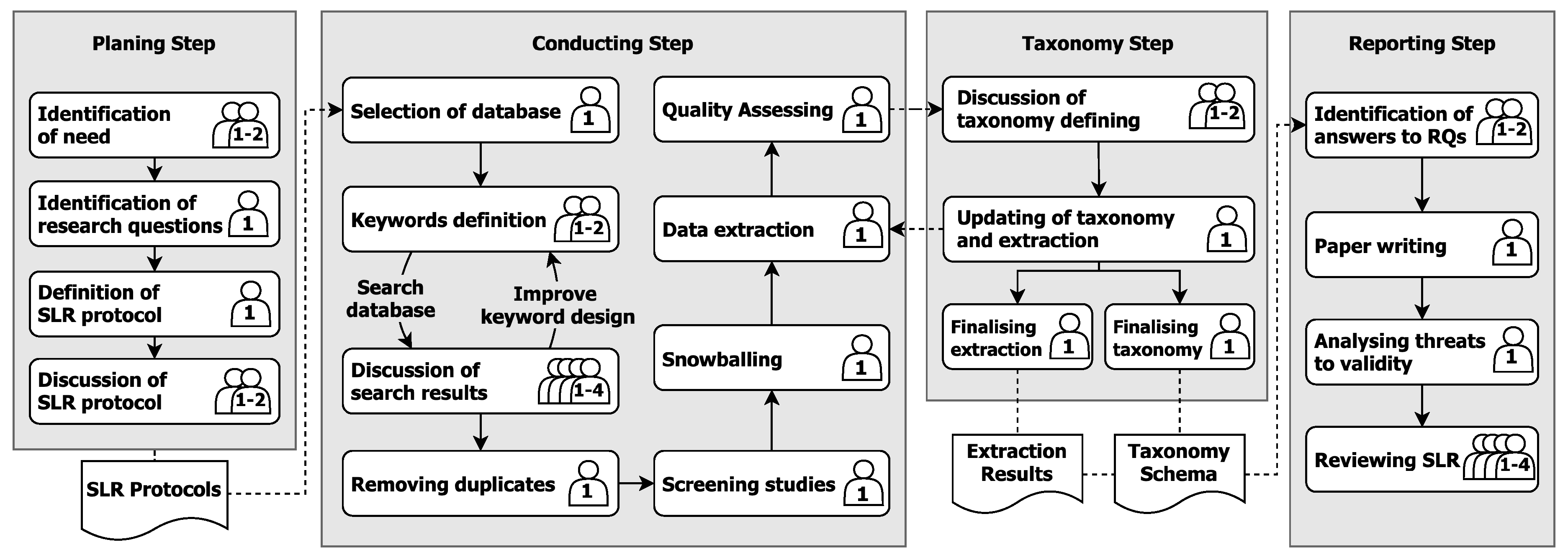

3.2.2. Automated Searching and Duplicate Removal

3.2.3. Filtering Process

- 1st-round Filtering was based on the title and abstract, using the criteria I01 and E01. At this stage, the number of papers was reduced from 21, 652 to 9, 071.

- 2nd-round Filtering. We attempted to include requirements-related papers based on E02 on the title and abstract level, which resulted from 9, 071 to 4, 071 papers. We excluded all the papers that did not focus on requirements-related information as an input or only mentioned the term “requirements” but did not refer to the requirements specification.

- 3rd-round Filtering. We selectively reviewed the content of papers identified as potentially relevant to requirements-driven automated test generation. This process resulted in 162 papers for further analysis.

3.2.4. Snowballing

3.2.5. Data Extraction

3.2.6. Quality Assessment

- QA1. Does this study clearly state how requirements drive automated test generation?

- QA2. Does this study clearly state the aim of REDAST?

- QA3. Does this study enable automation in test generation?

- QA4. Does this study demonstrate the usability of the method from the perspective of methodology explanation, discussion, case examples, and experiments?

4. Taxonomy

4.1. Designing of Taxonomy Schema

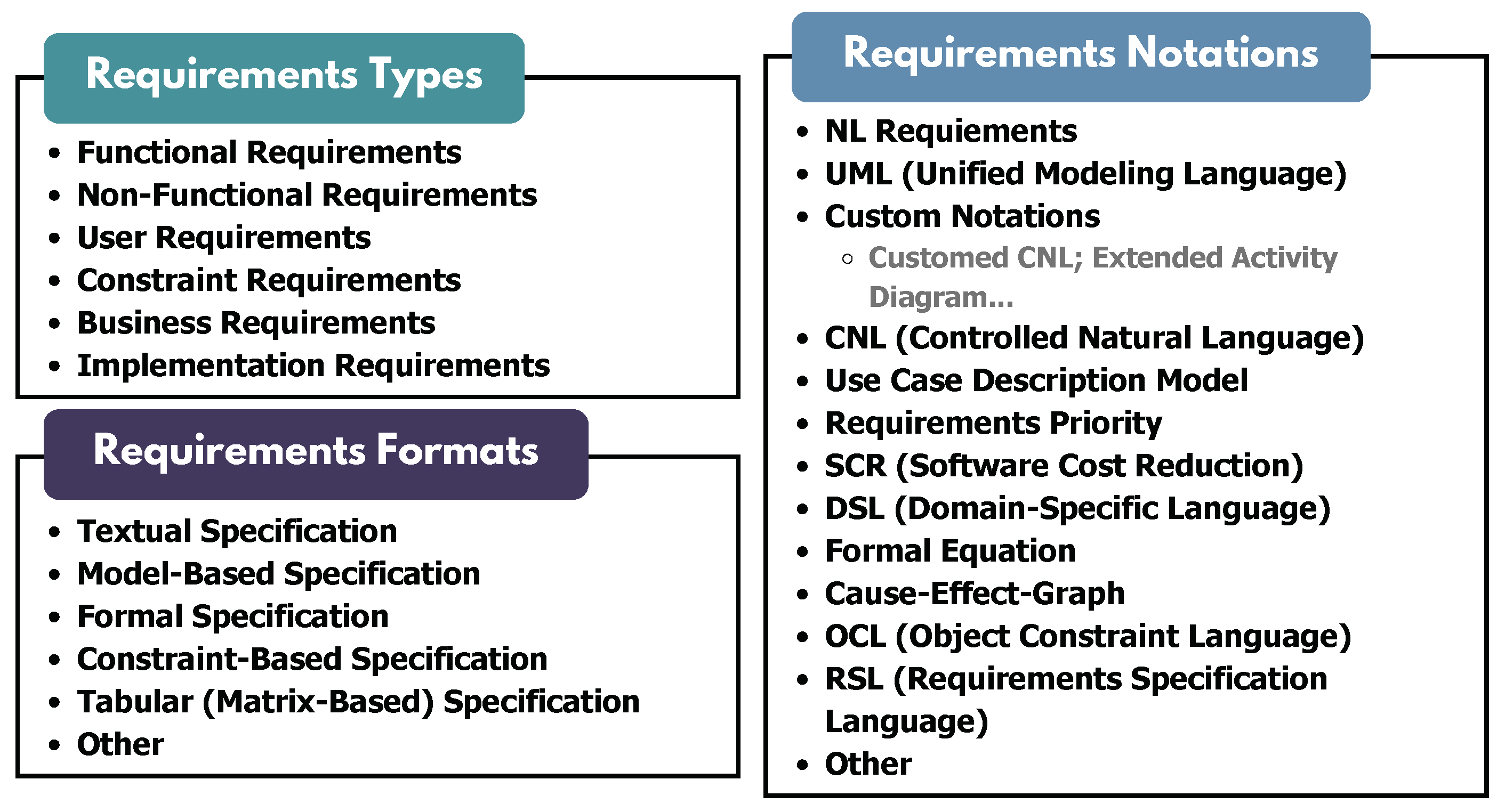

4.2. Requirements Input Category

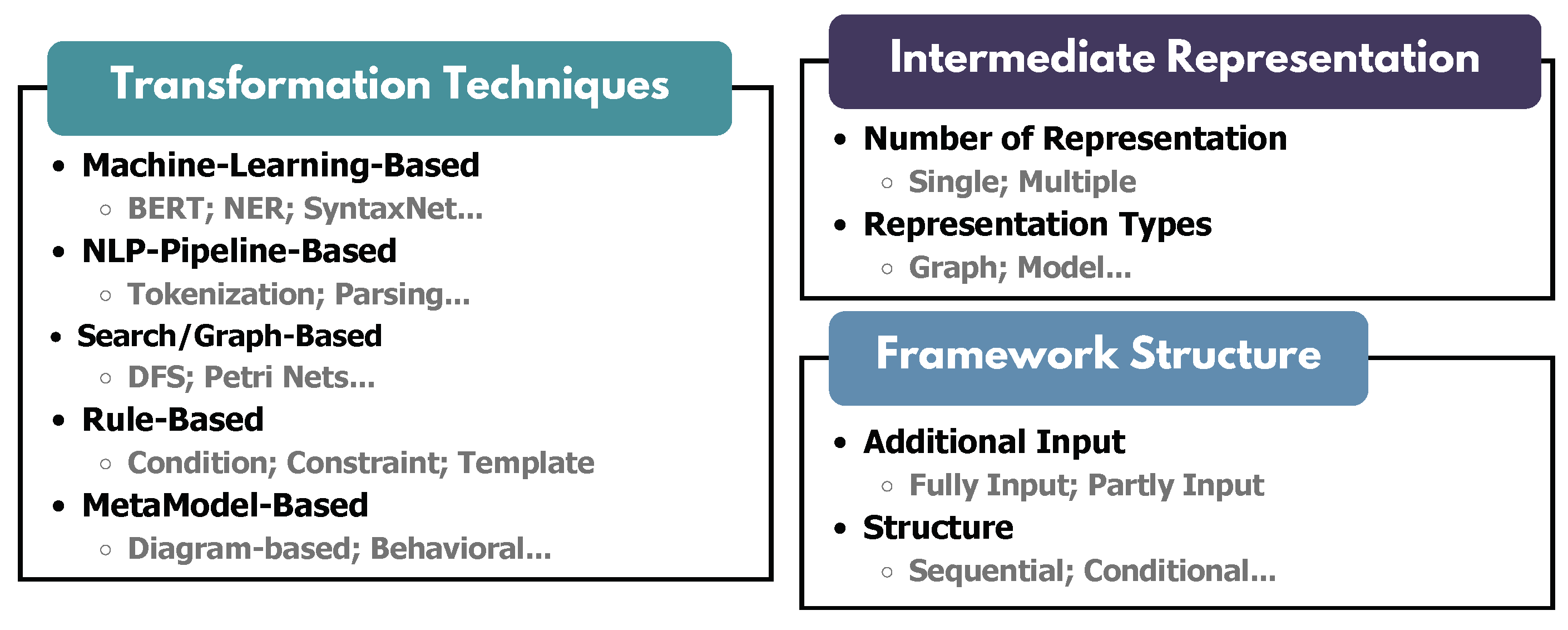

4.3. Transformation Techniques Category

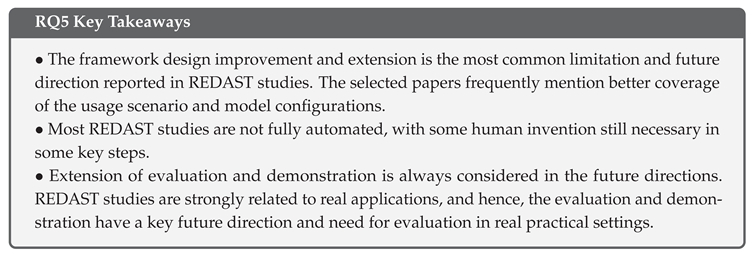

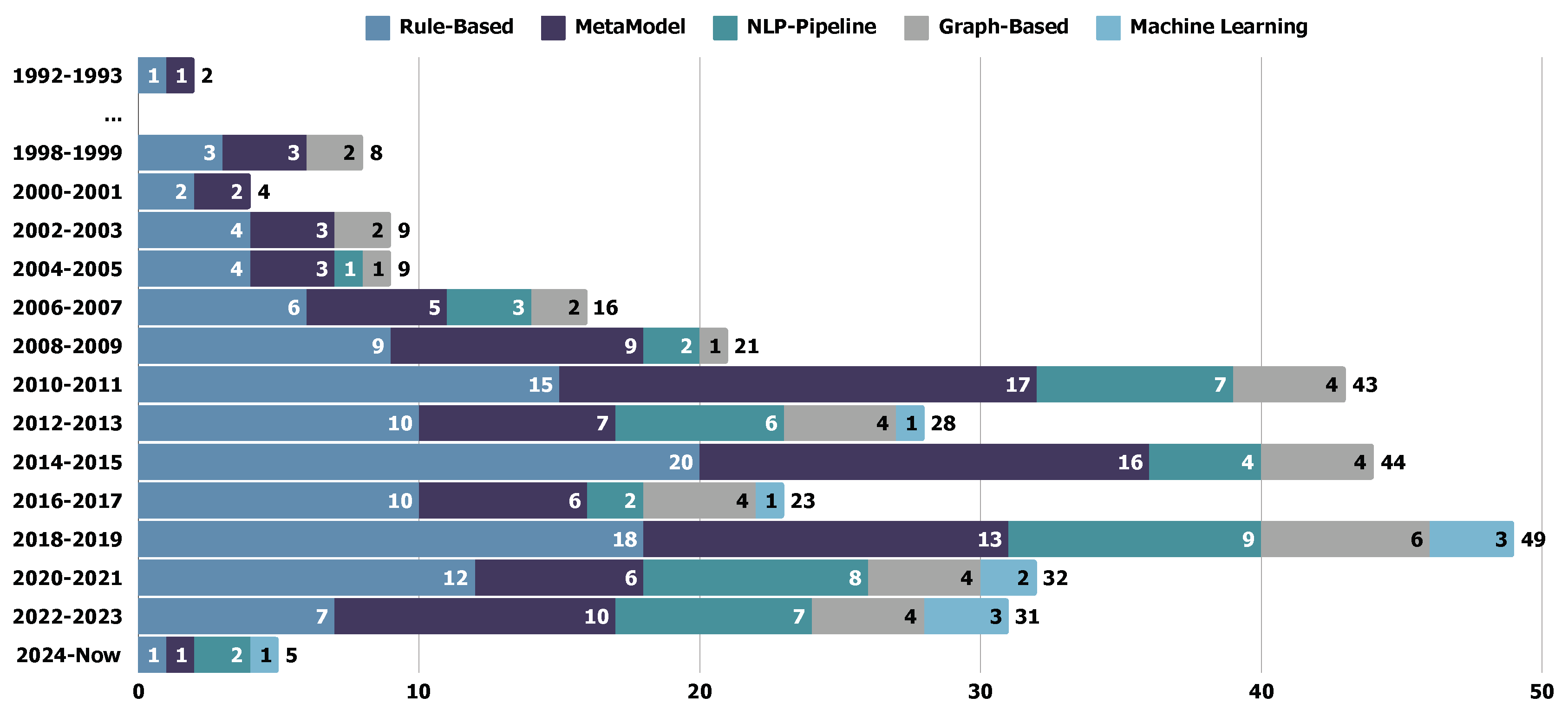

- Transformation Techniques. From requirements to generated test artifacts, the transformation techniques are expected to transfer requirements to readable, understandable, and generation-friendly artifacts for test generation. However, varying from different usage scenarios, various types of techniques are adopted in the transformation framework. Even though there are only limited studies explicitly discussing the transformation techniques for REDAST, we referred to the survey in related fields [39,40,41,42], such as automated software testing and software generation, to finalize our schema for transformation techniques. The categorization for transformation techniques can be formulated as five categories: (1) rule-based techniques rely on predefined templates or rules to formulate requirements to test artefacts; (2) meta-model-based techniques employ the meta-models to define the behavior, structure, relationships, or constraints to enable enhanced expression ability; (3) graph-based techniques mainly use the graph as representation (e.g., state-transition graphs, dependency graphs) with traversing or analyzing on paths, nodes, or conditions; (4) natural language processing pipeline-based techniques focus on leveraging open-source NLP tools for REDAST, like text segmentation and syntax analysis; (5) machine learning-based techniques leverage ML (including deep learning) in the REDAST process, which always involves the patterns or feature learning process using training data.

- Intermediate Representations are related to the optional steps in the generation framework. Some papers employ a stepwise transformation approach instead of directly transforming requirements into test artifacts. This approach generates intermediate artifacts that enhance the traceability and explainability of the methodology. For example, the unstructured NL requirements could be transformed into an intermediate more structured representation that facilitates the generation of test artifacts. While intermediate representations are derived from requirements, we employed a categorization method for representation types similar to that used in requirements schemas.

- Additional Inputs. In addition to simply using requirements as input, some frameworks accommodate additional input types, such as supporting documents, user preferences, and more. To analyze these frameworks from the perspective of input composition, we introduce additional inputs that categorize and examine the variety of inputs utilized.

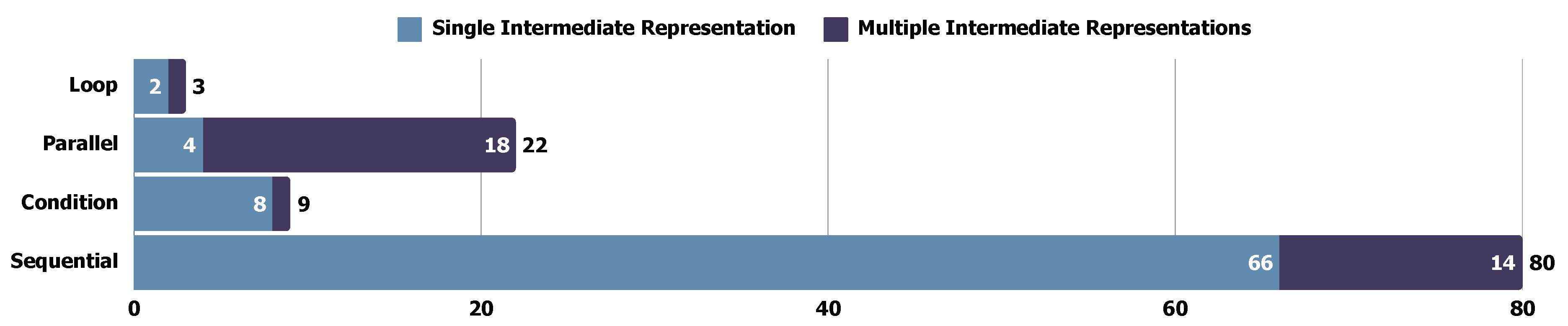

- Framework Structure refers to the underlying architectural approach used to transform requirements into test artifacts. It determines how different stages of transformation interact. Within the REDAST framework, transformation methodologies are categorized into four distinct structures ([43,44]): (1) Sequential – Follows a strict, ordered sequence of transformation steps, maintaining logical continuity without deviations. Each step builds upon the previous one; (2) Conditional – Introduces decision points that enable alternative transformation paths based on specific conditions, increasing adaptability to varying requirements; (3) Parallel – Allows simultaneous processing of different representations across multiple transformation units, significantly improving efficiency; (4) Loop – Incorporates iterative cycles for continuous refinement, ensuring enhanced quality through repeated validation and adjustment.

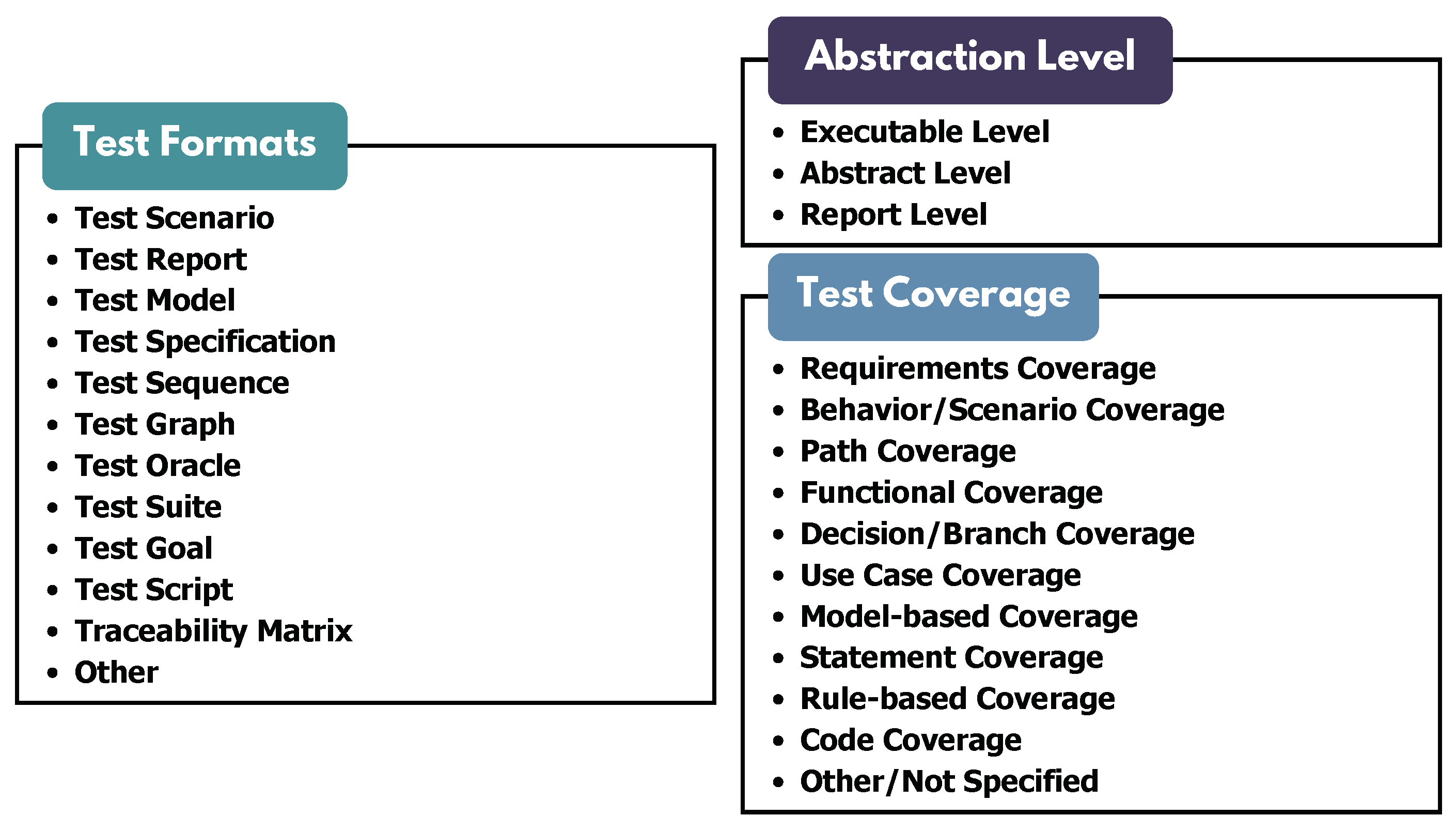

4.4. Test Artifacts Category

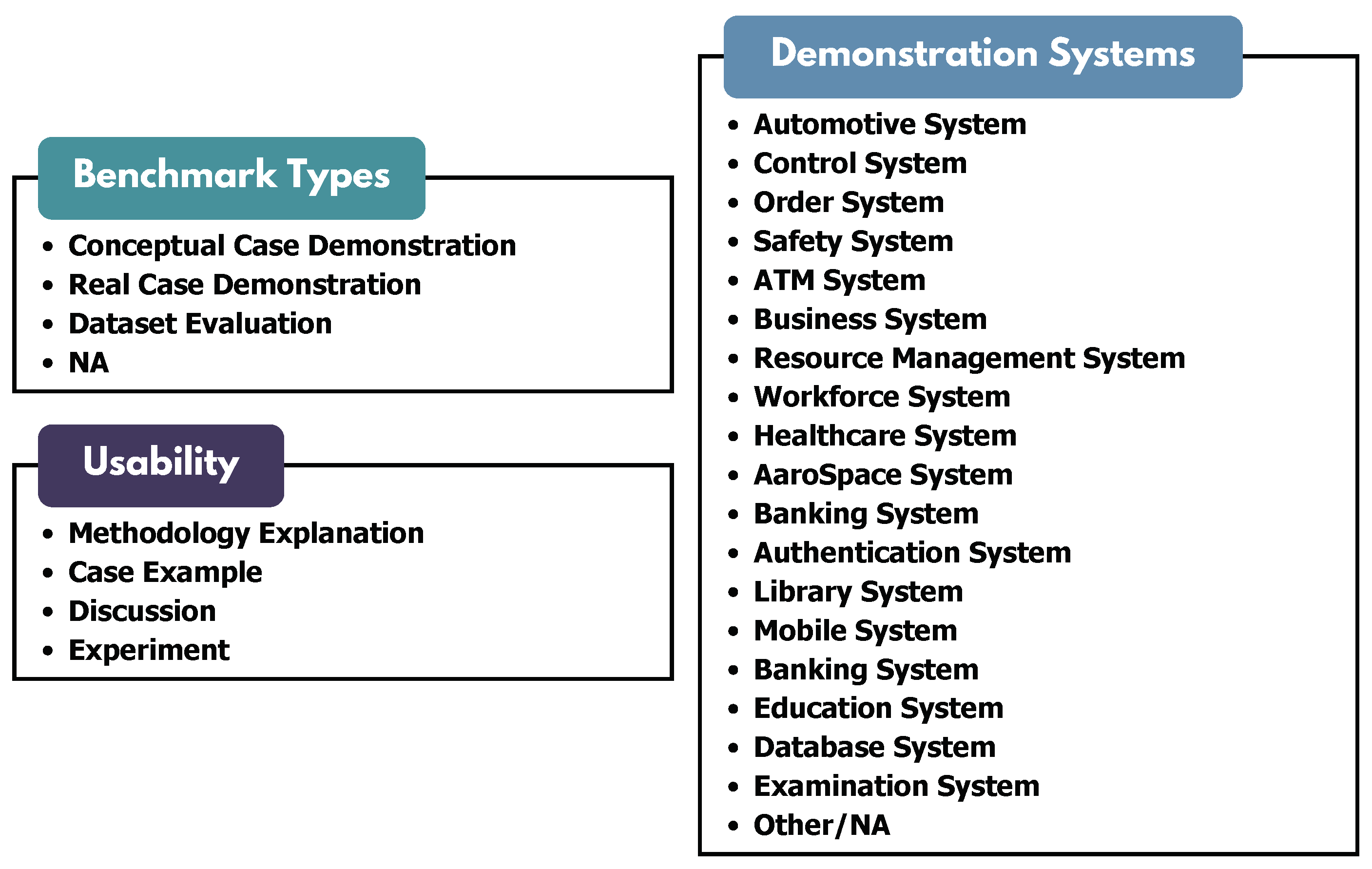

4.5. Results Demonstration Category

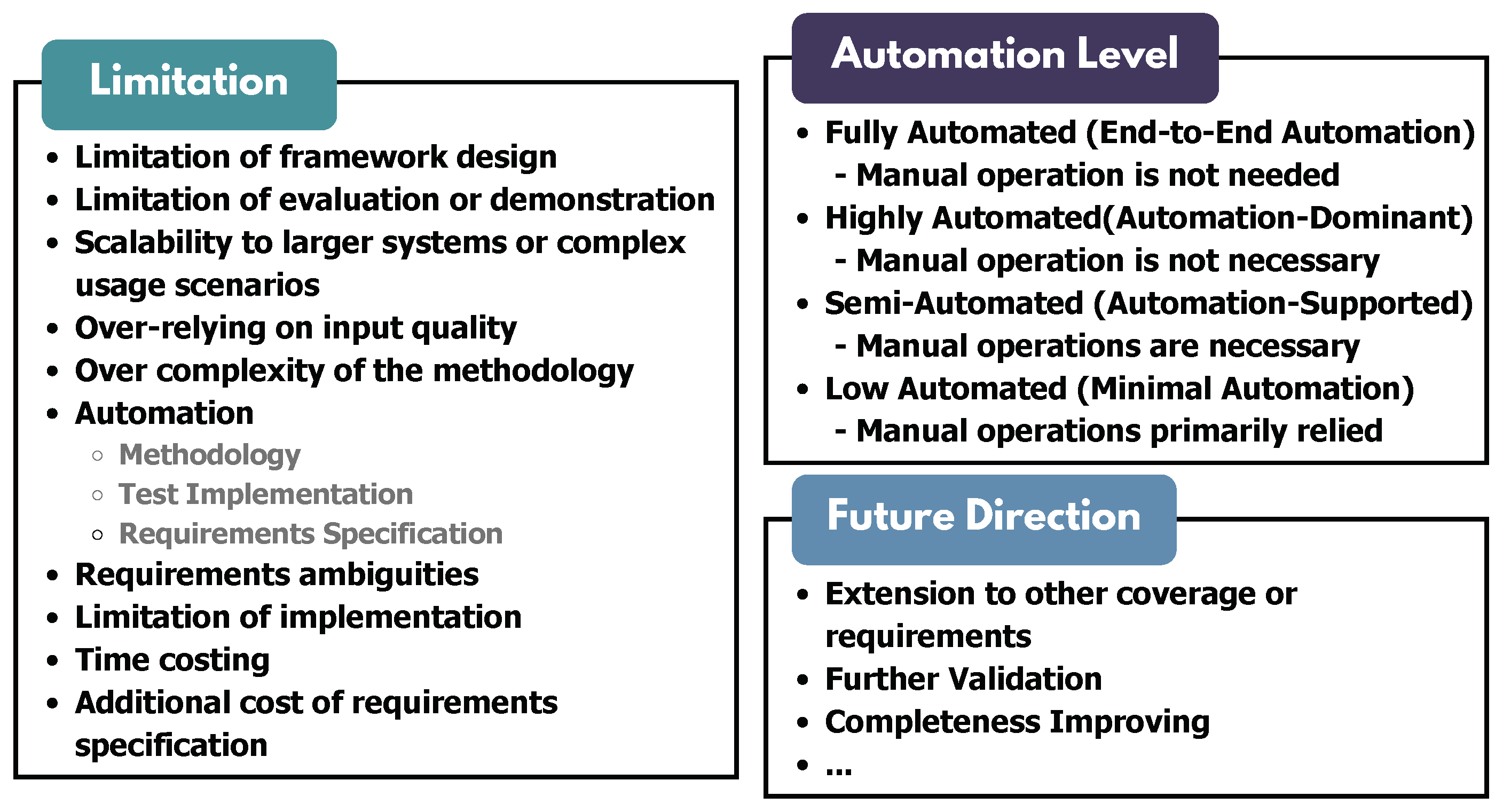

4.6. Future and Limitation Category

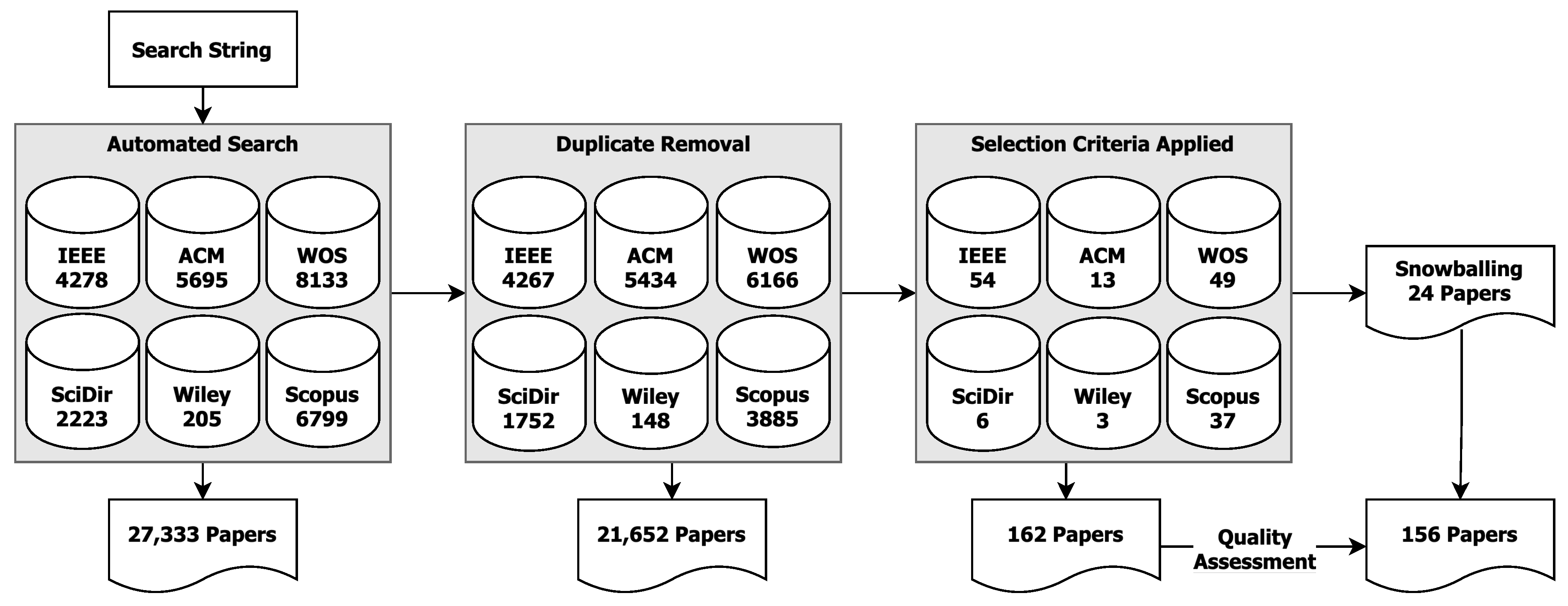

- Fully Automated (End-to-End Automation): Studies in this category require no human intervention or operation.

- Highly Automated (Automation-Dominant): These studies demonstrate a high degree of automation, with human intervention incorporated into the methodology but not essential.

- Semi-Automated (Automation-Supported): This level involves significant manual operations at specific stages of the process.

- Low Automated (Minimal Automation): Studies at this level exhibit only basic automation, relying primarily on manual operations across all steps.

5. Results

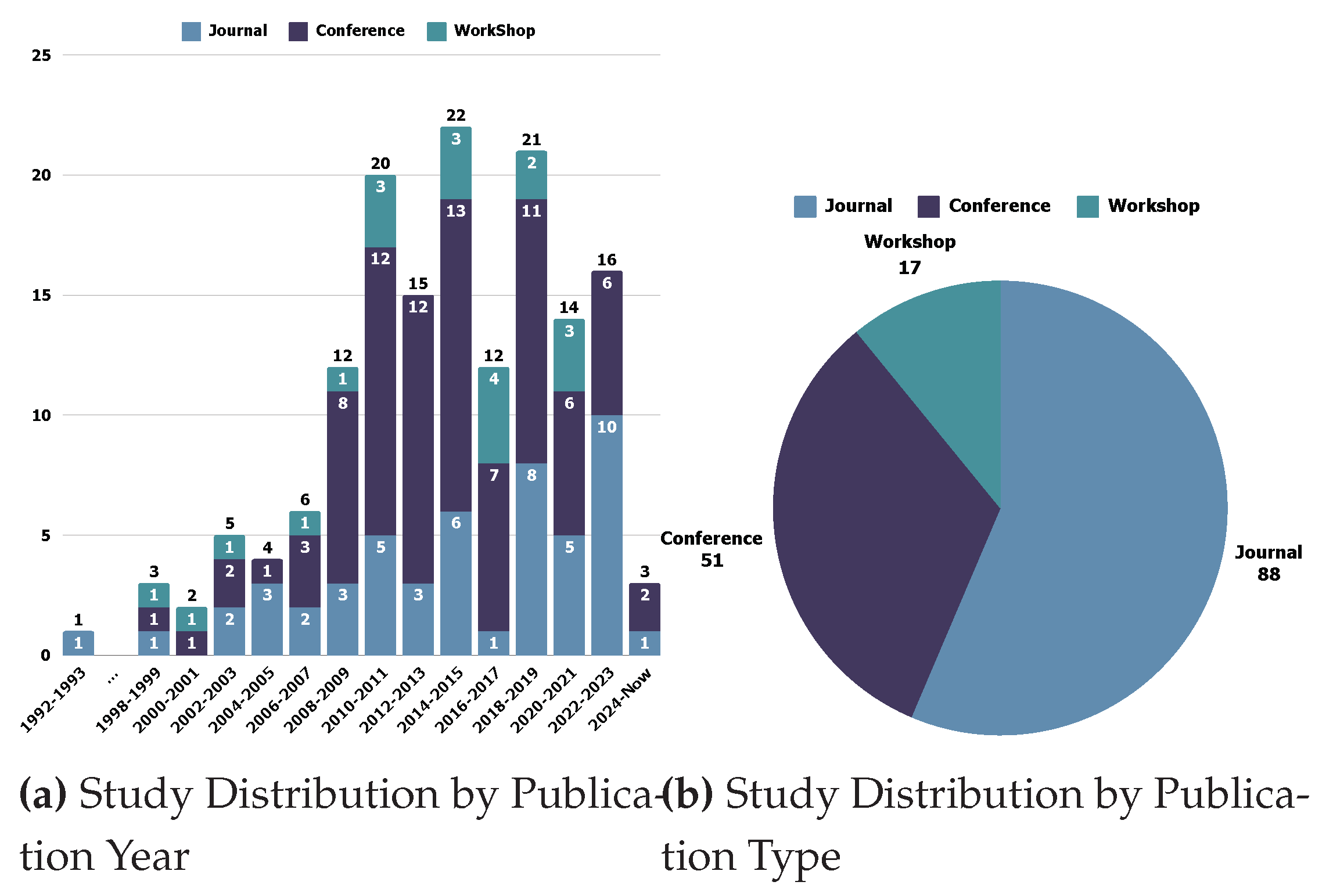

5.1. Trend: General Results of the Publications

5.2. RQ1: Requirements Specification Formulation

5.2.1. Requirements Types

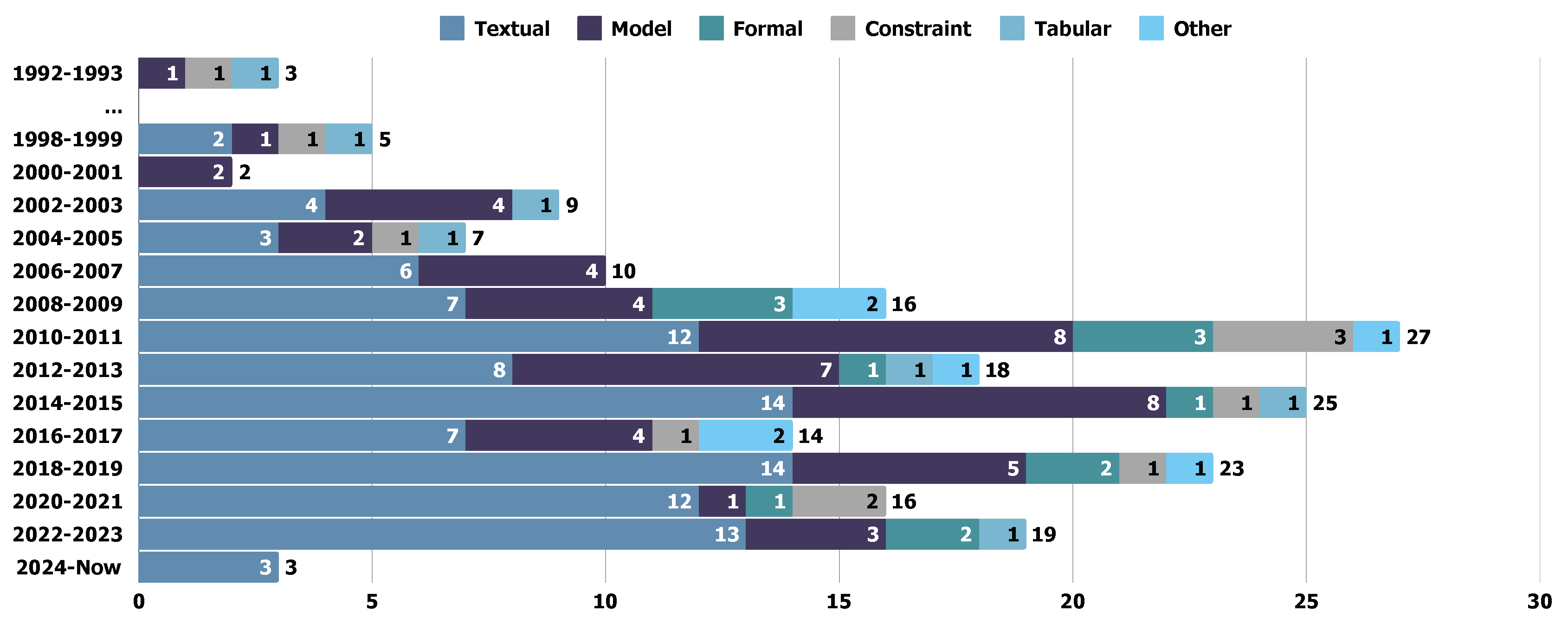

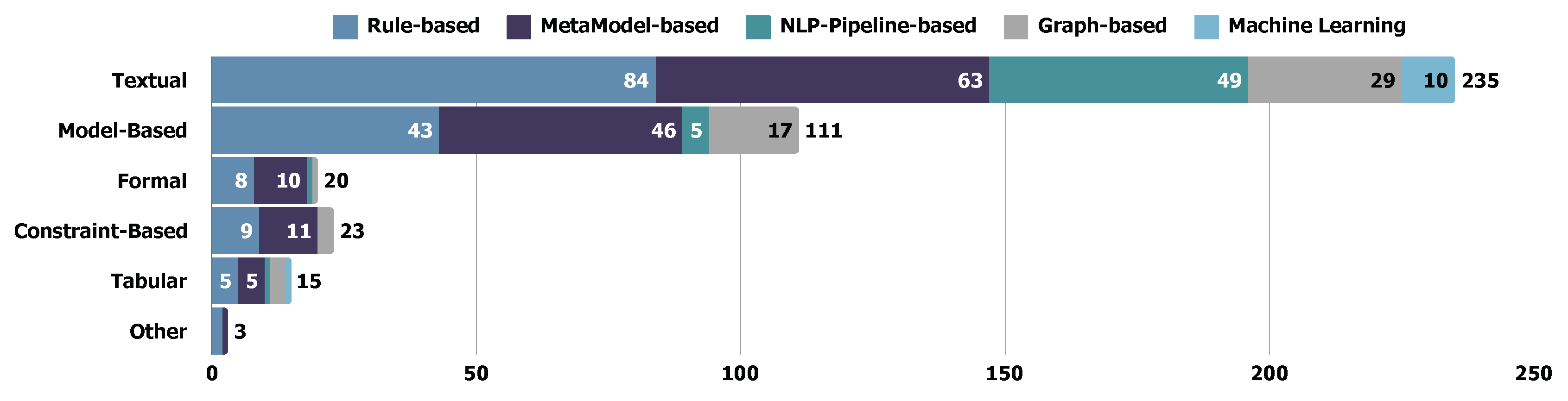

5.2.2. Requirements Specification Format

| Requirements Formats | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Textual | P2,P5,P6,P7,P8,P9,P10,P11,P12, | |

| P13,P14,P15,P16,P17,P18,P19,P22,P23,P24, | ||

| P25,P26,P28,P31,P32,P34,P36,P37,P38,P39,P41,P42,P43,P44,P45,P46, | ||

| P47,P48,P51,P52,P54,P55,P57,P58,P60,P61,P62,P63,P64,P65,P67,P68,P70, | ||

| P71,P75,P76,P77,P80,P82,P83,P84,P86,P88,P92,P93,P96,P98,P99,P102,P103, | ||

| P106,P108,P109,P110,P112,P114,P116,P117,P119,P121,P122,P123,P125,P126, | ||

| P127,P128,P129,P130,P132,P133,P134,P135,P136,P137,P138,P139,P140,P145, | ||

| P147,P149,P151,P152,P153,P156,P157,P160 | 105 | |

| Model-Based | P1,P4,P7,P8,P10,P11,P14,P15, | |

| P16,P17,P20,P21,P25,P27,P28,P30,P33,P35,P46,P49, | ||

| P50,P53,P56,P57,P65,P66,P69,P73,P74,P75,P78,P86, | ||

| P89,P90,P95,P96,P99,P104,P109,P110,P115,P119,P123, | ||

| P131,P137,P143,P144,P145,P148,P150,P152,P153,P154,P161 | 54 | |

| Formal | P3,P21,P45,P58,P59,P72, | |

| P79,P105,P110,P111,P113,P124,P155 | 13 | |

| Constraint-Based | P3,P27,P33,P59,P72, | |

| P78,P91,P100,P101,P105,P154 | 11 | |

| Tabular (Matrix-Based) | P29,P33,P78,P92,P107,P154,P159 | 7 |

| Other | P40,P94,P118,P142,P141,P146,P158 | 7 |

| Requirements Formats | Requirements Formulations | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Model Specification | Behavior Tree, Graph-based, Finite State Machine, Specification and Description Language (SDL), Use Case Map, Activity Diagram, Communication Diagram, Misuse Case, Conditioned Requirements Specification, Use Case, Scenario conceptual model, UML, Models, Sequence Diagram, State Machine Diagram, Scenario, NL requirements, pseudo-natural language, Behavior Model, Extended Use Case Pattern, Linear temporal logic, Communication Event Diagram (CED), SysML, Formal Use Case, Textual Normal Form, Object Diagram | 30 |

| Textual Specification | Graph-based, Scenario specification, User Story, NL Requirements, Use Case Map, Misuse Case, Use Case, Scenario Model, Textual, Scenario conceptual model, DSL, Use Case/Scenario, NL requirements (Behavior), Business Process Modeling Language, Signal Temporal Logic (STL), Restricted Signals First-Order Logic (RFOL), Formal Requirements Specification, Formal Use Case | 26 |

| Constraint Specification | Graph-based, OCL, DSL, Finite State Machine, Formal Requirements Specification, SysReq-CNL, Scenario, UML | 7 |

| Formal Specification | Signal Temporal Logic (STL), Restricted Signals First-Order Logic (RFOL), Formal Requirements Specification, Linear Temporal Logic, NL requirements, Use Case | 7 |

| Other Specification | Requirements Dependency, Requirements Priorities, Safety Requirements Specification, Test requirements | 4 |

| Tabular Specification | Scenario, Tabular Requirements Specification, Finite State Machine | 3 |

- Textual Specification. 105 studies adopted textual specification methods. Our analysis shows that textual specification is the most commonly used format in REDAST studies. Textual specification, written in natural language (NL), is the predominant choice. Besides the textual specification, NL is widely integrated into other specification formats, including formal (mathematical) and tabular specifications. NL-based requirements are generally favored in RADAST studies due to their accessibility and ease of understanding, which supports both requirements description and parsing NL is commonly used in these studies due to its advanced explainability and flexibility. We separately discuss this category by distinguishing textual specifications from others and whether the requirements follow natural language logic [52,53]. Other formats especially involve specific specification rules or templates compared to textual specifications.

- Model-based Specification. 54 studies specify requirements using model-based specifications. Model-based approaches construct semi-formal or formal meta-models to represent and analyze requirements. Compared to textual specifications, meta-models have better abstraction capabilities for illustrating the behaviors (e.g., P1 P1, P27 P27, P35 P35, etc.), activities (e.g., P25 P25, P139 P144, P146 P151, etc.), etc., of a software system [54].

- Constraint-based Specification. We identified 11 studies in the selected papers that utilize constraint-based requirements specification. Constraint-based specification is also a welcomed requirements format, where Domain-Specific Language are adopted in the selected studies, e.g., P3 P3, P89 P92, P96 P100, etc. Constraint-based specification involves defining system properties as limits, conditions, or relationships that must hold within the system. Constraint-based specification can provide a concise and precise description of system behavior, especially in the context of complex software systems [55,56]. DSL is a typical constraint-based specification, e.g., P88 P91, P95 P99, and P96 P100.

- Formal (Mathematical) Specification. In the selected studies, we identified 13 papers that used formal (mathematical) specifications in requirements elicitation. The formal (mathematical) specification can translate natural language requirements into a precise and unambiguous specification that can be used to guide the development of software systems [57], where the typical formal requirements specification are assertions (e.g., P109 P113), controlled language (e.g., P79 P79, P108 P112), and so on. Unlike textual specification, the logical expression can describe software requirements unambiguously [58].

- Tabular (Matrix-based) Specification. We identified 7 studies that adopted tabular specifications. Tabular specification methods can formalize requirements in a structured and organized manner, where each row represents a requirement, and each column represents a specific attribute or aspect of the requirement [57]. Tabular specification can greatly improve traceability and make it more friendly for verification and validation.

5.2.3. Requirements Specification Notation

- NL Requirements Specification. We found that 47 studies introduced natural language (NL) requirements specifications in their methods. NL requirements specifications are used not only in REDAST studies but also in requirements elicitation and specification domains. For example, “shall” requirements (formally known as IEEE-830 style “shall” requirements [59]) are widely used for requirements specification, enabling less ambiguity and more flexibility. NL requirements specifications are applicable for various processing methods, such as condition detection (e.g., P23 P23) and semantic analysis (e.g., P63 P63).

- Unified Modeling Language Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a commonly used notation in model-based specification. We identified 33 studies that utilized UML in the selected papers. UML is versatile and can be combined with other notations to describe scenarios, behaviors, or events, effectively capturing functional requirements [60]. For instance, in the selected studies, P56 P56 introduced a tabular-based UML for requirements traceability, while P17 P17 employed UML use case diagrams specifically to depict requirement scenarios.

- Controlled Natural Language. In the selected studies, 15 papers opted for controlled natural language (CNL) as a requirement notation. CNL is partly based on natural language but is structured using the Rimay pattern [61], deviating from conventional expression syntax.

- Use Case, User Story, and Their Variations. Use cases, user stories, and their variations are distinct requirement notations in scenario-based specifications, sharing similar characteristics. These notations generally consist of a cohesive set of possible dialogues that describe how an individual actor interacts with a system or use textual descriptions to depict the operational processes of the system. In this way, the system behavior is vividly explained.

- Other Specifications. Other specification notations are not frequently adopted methods, where the “Other” category contains the notations that appear one time. Most of them are variations of common notations.

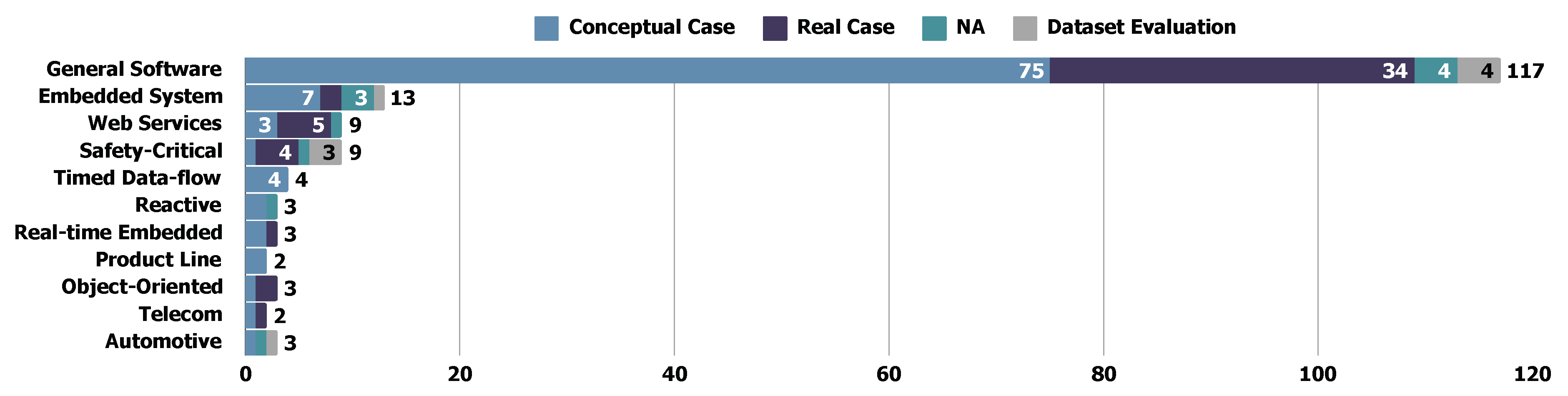

5.2.4. Findings: Cross-Analysis of Requirements Input and Target Software

| Target Software | Model-based | Textual | Constraint-based | Formal | Other | Tabular (Matrix-based) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Software | 75 | 34 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Embedded System | 7 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Web Services | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Safety-Critical | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Timed Data-flow | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reactive | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Real-time Embedded | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Product Line | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Object-Oriented | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Telecom | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Automotive | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

5.2.5. Findings: Trend of Requirements Input Over the Years

5.3. RQ2: Transformation Technology in REDAST

5.3.1. Transformation Techniques

- Template-based techniques formulate the generated artifacts into predefined templates for further processing.

- Constraint-based techniques indicate the transforming process for new artifact generation, where the rule here refers to the transformation rules.

- Condition-based techniques are defined for the static regulating within existing generated artifacts based on predefined conditions or forms.

| NLP-Pipeline Method | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Dependency Parsing | P22, P23, P36, P41, P42, P43, P44, P55, P57, P70, P71, P77, P98, P106, P108, P116, P117, P127, P130, P135, P159 | 21 |

| POS Tagging | P22, P24, P32, P36, P41, P43, P48, P52, P60, P68, P70, P77, P106, P116, P122, P133, P134, P135, P139, P157, P159 | 21 |

| NL Parsing | P19, P44, P48, P55, P60, P70, P71, P76, P115, P126, P127, P130, P139, P157 | 14 |

| Tokenization | P18, P23, P24, P36, P43, P48, P83, P98, P116, P122, P127, P135, P157, P160 | 14 |

| CNL Parsing | P2, P9, P28, P42, P45, P62, P65, P80, P132, P134, P137, P156 | 12 |

| Semantic Analysing | P24, P60, P63, P77, P82, P83, P108, P117, P126 | 9 |

| Sentence Splitting | P43, P71, P115, P126 | 4 |

| Condition Detector | P23 | 1 |

| Lemmatization | P135 | 1 |

| Word Embedding | P127 | 1 |

| Word Frequency Analysing | P52 | 1 |

| Graph-based Methods | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Depth First Traversal (DFT) | P6, P8, P12, P33, P50, P53, P59, P66, P78, P103, P121, P127, P136 | 13 |

| Breadth-First Traversal (BFT) | P13, P28, P74, P77, P78, P92, P103, P127, P145 | 9 |

| Graph Traversal | P19, P70, P86, P88, P116, P153, P161 | 7 |

| Knowledge Graph (KG) | P98, P127, P139 | 3 |

| Petri Nets | P47, P89, P65 | 3 |

| Graph Splitting | P71 | 1 |

| Graph-Theoretical Clustering | P71 | 1 |

| Greedy Search Strategy | P26 | 1 |

| Meta-Heuristic Search Algorithm | P61 | 1 |

| Path Sensitization Algorithm | P57 | 1 |

| Round-Strip Strategy | P25 | 1 |

| Shortest Path Finding Strategy | P42 | 1 |

| Graph Simplifying | P17 | 1 |

| Machine Learning Methods | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| BERT & Classifier | P23, P98, P128 (Seq2Seq) | 3 |

| SyntaxNet | P93, P126 | 2 |

| Pretrained NER Model | P52, P127 | 2 |

| MLP Classifier | P18 | 1 |

| k-Means Clustering | P159 | 1 |

| LLM & RAG | P160 | 1 |

5.3.2. Framework Details

| Additional Input Types | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Source Code | P82, P159 | 2 |

| System Implementation | P69, P112 | 2 |

| System Implementation and Supporting Documents | P113, P129 | 2 |

| Historical Documents | P32 | 1 |

| Requirements Documents and Historical Documents | P127 | 1 |

| Requirements Documents and Scenario | P96 | 1 |

- Historical Documents are always referenced in the generation process. For example, P2 P2 opted for historical test logs as the additional input in the test generation step. The test logs can serve as a reference for evaluating the generated test artifacts.

- System Implementation is the next stage after requirements engineering based on the SDLC, where the requirements are believed to dominate the implementation process and vice versa significantly. In P109 P113, the implementation documents are used in the analysis to provide evidence from the actual scenario.

- Source Code can also be used as an additional input alongside requirements in the transformation process. P154 P159 introduces code updating information in the test prioritization process, which is used to find the error-prone modules.

- Additional Documents, such as ground knowledge documents, are used to support test generation with a more substantial knowledge base. P122 P127 is a KnowledgeGraph-based method, where the ground knowledge is largely integrated for constructing the knowledge graph.

| Structure | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Sequential | P1, P2, P5, P6, P8, P11, P12, P13, P14, P16, P17, P20, P22, P24, P26, P27, P29, P30, P31, P32, P33, P35, P36, P37, P40, P43, P44, P45, P46, P50, P53, P54, P55, P58, P59, P61, P62, P64, P65, P70, P75, P76, P77, P78, P100, P101, P102, P107, P108, P109, P110, P111, P114, P115, P116, P118, P121, P124, P125, P127, P128, P129, P132, P133, P134, P135, P136, P137, P139, P142, P143, P145, P146, P147, P148, P149, P151, P154, P156, P159 | 80 |

| Parallel | P3, P7, P9, P10, P19, P21, P25, P34, P39, P51, P52, P57, P66, P68, P72, P74, P80, P104, P140, P150, P152, P153 | 22 |

| Conditional | P15, P18, P28, P47, P49, P71, P73, P144, P155 | 9 |

| Loop | P4, P56, P113 | 3 |

- Sequential Structure. The sequential framework conducts transformations in a strict, ordered sequence without any bypasses or shortcuts. This approach enhances logical continuity and maintains a clear connection between each step. P107 P111 is a typical sequential framework where the formal specifications are step-by-step transformed into conjunctive normal form, assignment, and test cases.

- Conditional Structure. This framework introduces conditional steps, allowing for alternative paths at key stages. This flexibility improves adaptability and generalization, enabling the framework to manage diverse scenarios effectively. P73 P73 is a good example in this category, where this study constructs several conditions in transformation, e.g., “Need more details of requirements”, “There are improvements of transformation”, etc.

- Parallel Structure. In a parallel framework, different representations can be processed simultaneously across multiple transformation processors. This structure significantly boosts time efficiency. The typical parallel structure can be found in P10 P10. This study constructs a two-way structure and converts requirements input to use case diagrams and executable contracts for generating contractual use case scenarios.

- Loop structure. The loop structure incorporates assertion-controlled loops, enabling iterative refinement of generated artifacts. Cycling through iterations ensures higher quality in the final outputs. For example, P109 P113 introduces the loop structure by designing a validation and tuning process to refine the guarded assertions in this method iteratively.

5.3.3. Intermediate Representation

- Rule-based Representation (51 studies): The rule-based representation here refers to general controlled NL, assertion, or equation, where these notations generally consist of descriptions with predefined conditions or forms.

- MetaModel-based Representation (48 studies): MetaModel has widely opted for intermediate representation, where model attributes offer additional explainability for test transformation.

- Graph-based Representation (38 studies): Graph is an advanced representation method that reflects basic information and indicates the co-relations among different elements.

- Test-Specification-based (5 studies): Some studies introduce test-related intermediate representation but cannot classify it into parts of the test outcome. Thus, the test-specification-based representation is especially considered a category. We didn’t identify too many test-specification-based representations in selected studies.

5.3.4. Findings: Trend of Transformation Techniques Over the Years

5.3.5. Findings: Cross-Analysis of Requirements Input and Transformation Techniques

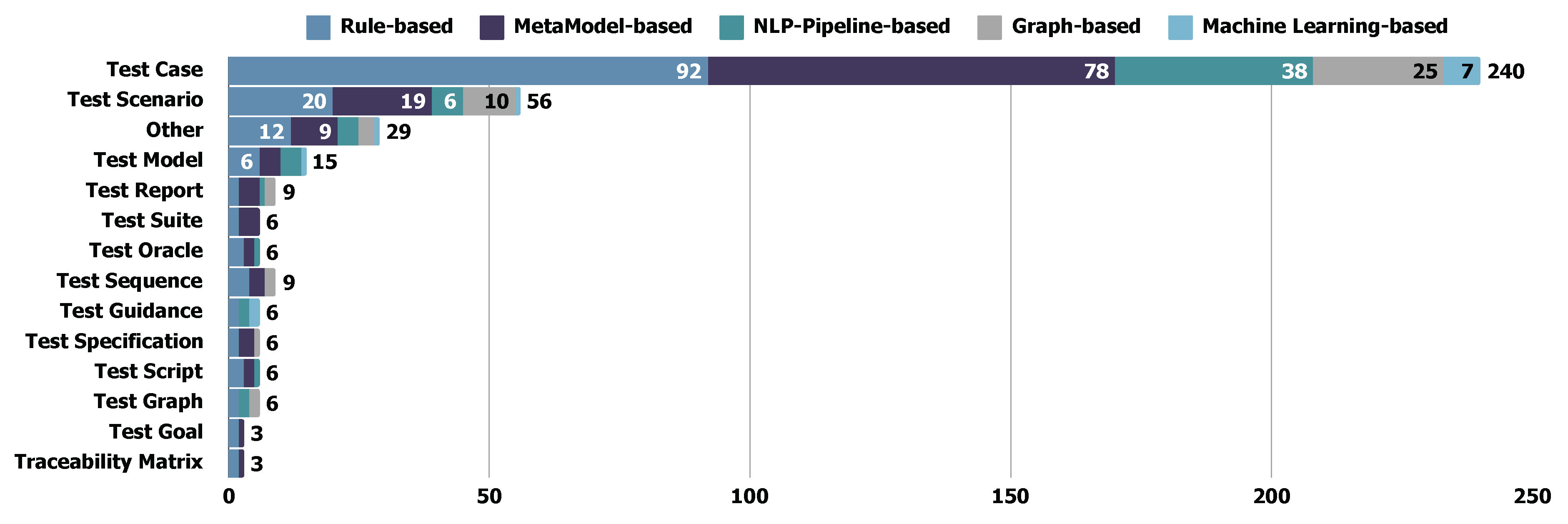

5.4. RQ3: Generated Test Artifacts in REDAST

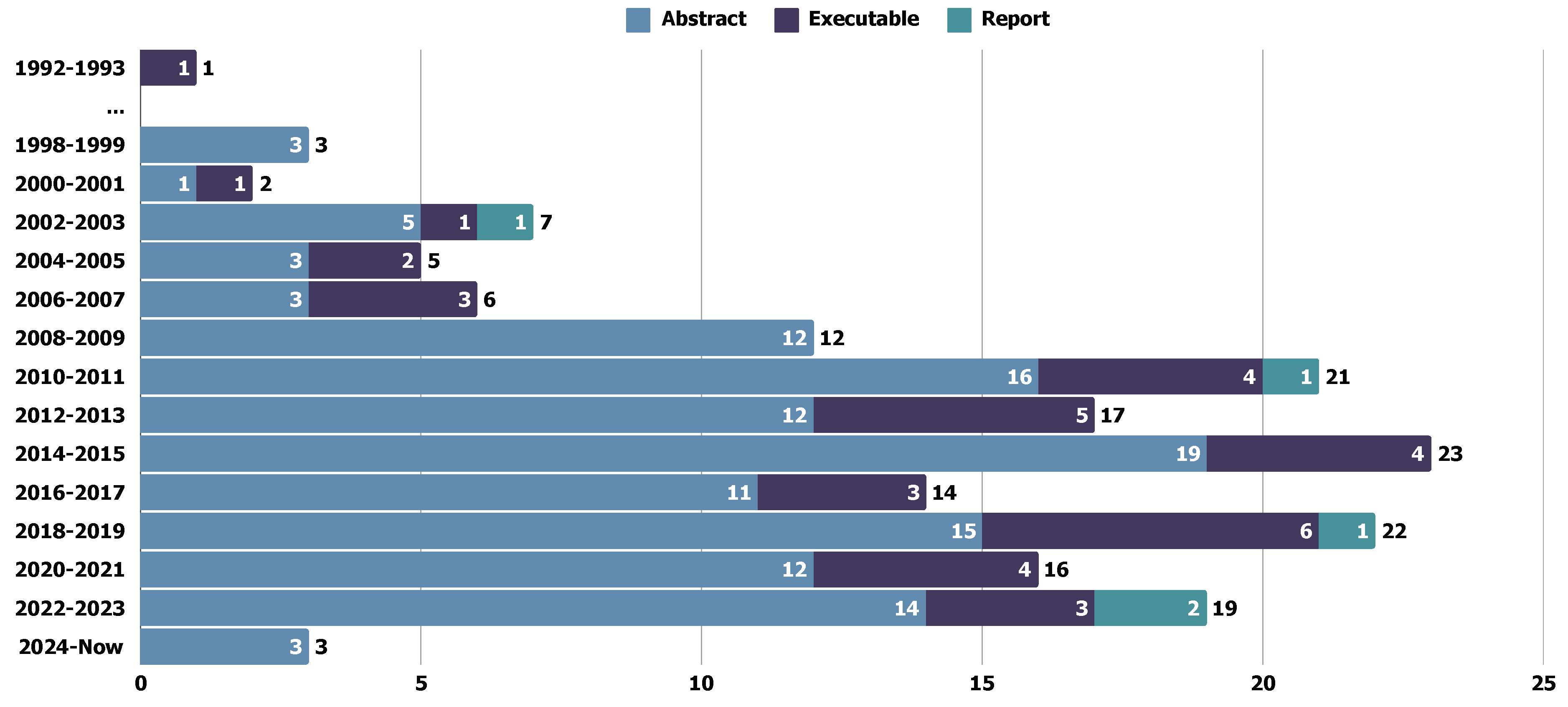

5.4.1. Test Abstraction Level

- Executable Level includes artifacts, such as code and scripts, that can be directly executed. Typically, the test artifact in P94 P98 is on the executable level, where the test case consists of several sections, including “Target Entities”, “Test Intent”, “Extracted Triplets”, “Context Sub-graph”, “Test Case”, and so on.

- Abstract Level includes the artifacts that cannot be directly executed, e.g., textual scenarios, test diagrams, etc. We identify P71 P71 as an example of this category. P71 generates test plans consisting of activities and acceptance criteria, where the acceptance criteria in this study don’t give specific operation or system behavior, e.g., “Is bill paid?”, “Is ID card valid?” or some similar statements.

- Report Level mainly refers to the results after executing test artifacts. We separately present this because some studies also provide the executing tool. In P29 P29, this study introduces an automatic tester using generated test data. The final output is the corresponding test report from the tester.

| Abstraction Levels | Paper ID | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Executable | P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P7, P8, P9, P11, P12, P13, P15, P16, P19, P21, P23, P24, P25, P26, P27, P28, P29, P30, P31, P32, P33, P34, P35, P36, P37, P38, P39, P40, P43, P44, P45, P48, P49, P50, P51, P52, P53, P54, P55, P56, P57, P58, P59, P60, P61, P62, P63, P64, P65, P66, P67, P68, P70, P73, P76, P77, P78, P79, P80, P82, P83, P84, P86, P88, P90, P91, P92, P94, P95, P96, P98, P99, P100, P101, P103, P104, P105, P106, P107, P108, P109, P110, P111, P112, P113, P114, P116, P118, P119, P121, P123, P124, P125, P127, P128, P129, P130, P131, P132, P133, P134, P135, P136, P138, P140, P141, P142, P143, P144, P145, P146, P147, P148, P149, P151, P152, P153, P155, P156, P157, P158, P159, P160, P161 | 129 |

| Abstract | P5, P6, P7, P10, P14, P17, P18, P20, P22, P26, P41, P42, P46, P47, P69, P71, P72, P73, P74, P75, P80, P84, P89, P91, P93, P102, P115, P117, P122, P125, P126, P137, P139, P140, P147, P150, P154 | 37 |

| Report | P15, P29, P57, P89, P149 | 5 |

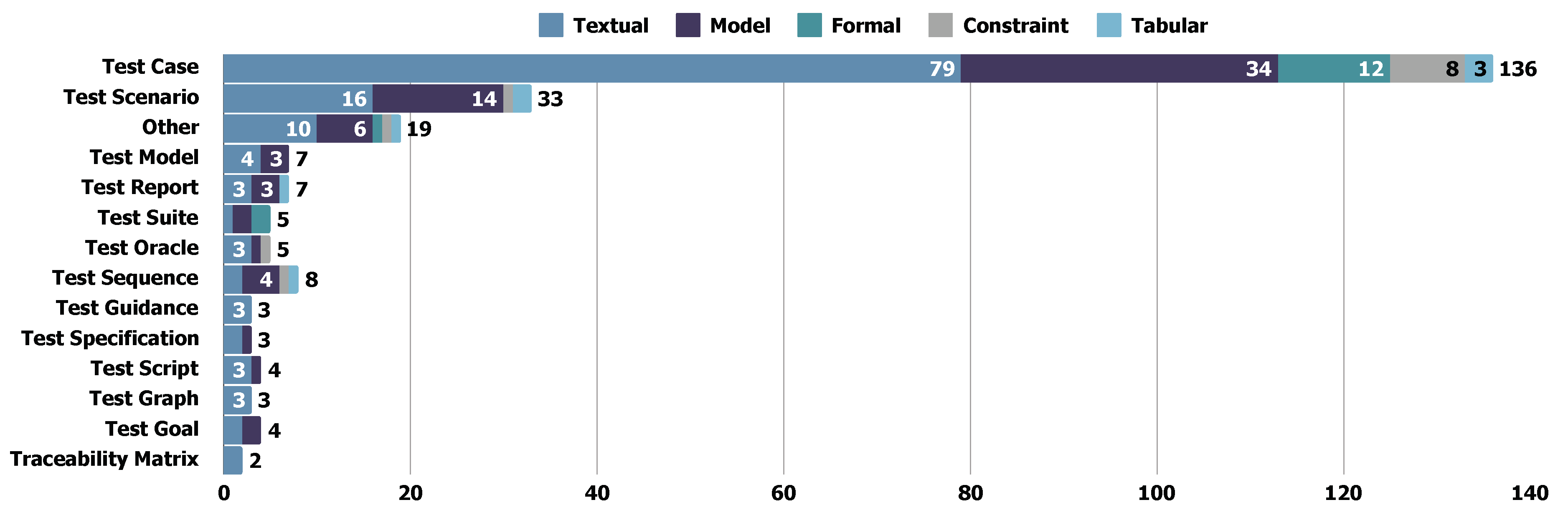

5.4.2. Test Formats

- Test Case, Test Scenario, and their Variations are the most commonly derived test formats in REDAST papers. Test scenarios enable a high-level description of the test objectives from a comprehensive point of view. Test cases include more detailed, stepwise instructions or definitions by focusing on a specific software part.

- Test Requirements, Guidance, Plan, Suggestion, and Acceptance Criteria. These test artifacts generally offer high-level, abstracted, or constructive objectives and suggestions for software testing. Rather than specifically match every step in software testing, they enable high-level instruction for test structure.

- Test Suite, Script, and Oracle, compared with the other formats, are advanced in applicability and usability. Generally, assertion, code, or any executable source are used in these formats, which are designed for execution.

- Test Sequence, Model and Goal. These test formats are designed to meet the specific test objectives in the structural testing process. The model or sequence in these formats enables better traceability compared with the other formats.

5.4.3. Test Coverage Methods

5.4.4. Findings: Trend of Test Abstraction Level Over the Years

5.4.5. Findings: Cross-Analysis of Transformation Techniques and Test Artifacts

5.4.6. Findings: Cross-Analysis of Requirements Input and Test Artifacts

5.5. RQ4: Evaluation Methods of REDAST Studies

5.5.1. Types of Evaluation Methods

- Conceptual Case Demonstration. These studies typically begin by designing a conceptual case and then applying REDAST methods to the designed case to demonstrate the test generation process. Commonly used conceptual cases include online systems (e.g., P11 P11, P21 P21, P119 P124), ATMs (e.g., P12 P12, P13 P13, P35 P35), and library systems (e.g., P6 P6), among others. While these demonstrations effectively illustrate the methodology procedure, they often lack compulsion and persuasiveness in demonstrating the efficacy of the results. However, the use of conceptual cases, which are based on widely familiar scenarios, enhances understandability. This familiarity benefits readers by making the methodologies easier to comprehend and follow.

- Industrial Case Demonstration. Studies in this category demonstrate their methods by incorporating industrial cases into their experiments. By re-organizing and utilizing data extracted from industrial scenarios, REDAST methods are validated under real-world conditions, offering stronger evidence and greater persuasiveness compared to conceptual case studies. Additionally, we observed that some studies intersect across categories, combining (i) both conceptual and industrial case studies, and (ii) industrial case studies with dataset evaluations (e.g., P28 P28 on several industrial cases from public paper, P155 P160 on postal systems). These overlaps occur because industrial cases not only serve as a basis for case studies but can also be used to formulate evaluation datasets, further enhancing their utility in validating methodologies.

- Evaluation on Given Datasets. Evaluations conducted on public or industrial datasets provide a compelling approach to demonstrating the efficacy and usability of a method. However, transitioning from discrete cases to datasets requires significant additional effort, including data cleaning, reorganization, and formulation. This challenge arises due to two primary factors: (1) the high usability requirements of REDAST studies, which are often difficult to demonstrate effectively using certain datasets, and (2) the absence of a standardized benchmark dataset for evaluating test artifacts. As a result, most studies rely on case demonstrations rather than systematic evaluations with well-formulated datasets. Only a small number of studies (e.g., P18 P18, P39 P39, P41 P41) employ dataset evaluations within the selected works.

5.5.2. Software Platforms in Case Demonstration

5.5.3. Examples of Evaluation or Experiments

Case 1: P155 - Generating Test Scenarios from NL Requirements using Retrieval-Augmented LLMs: An Industrial Study

Case 2: P24 - Automatic Generation of Acceptance Test Cases from Use Case Specifications: an NLP-based Approach

5.5.4. Findings: Cross-Analysis of Demonstration Types and Target Software Systems

5.6. RQ5: Limitation, Challenging and Future of REDAST Studies

5.6.1. Limitations in Selected Studies

5.6.2. Insight Future View from Selected Studies

5.6.3. Findings: Cross-Analysis of Demonstration Types and Validation Challenges

5.6.4. Findings: Trend of Automation Level Over the Years

6. Threats to Validity

6.1. Internal Validity

6.2. Construct Validity

6.3. Conclusion Validity

6.4. External Validity

7. Discussion and Roadmap

7.1. Data Preprocessing for REDAST

7.2. Requirements Input for REDAST

7.3. Transformation Techniques for REDAST

7.4. Test Artifacts Output for REDAST

7.5. Evaluation Solutions for REDAST Studies

7.6. Other Suggestion for REDAST Studies

8. Conclusion

References

- Bertolino, A. Software Testing Research: Achievements, Challenges, Dreams. In Proceedings of the Future of Software Engineering (FOSE ’07), 2007, pp. 85–103. [CrossRef]

- Baresi, L.; Pezzè, M. An Introduction to Software Testing. Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science 2006, 148, 89–111. Proceedings of the School of SegraVis Research Training Network on Foundations of Visual Modelling Techniques (FoVMT 2004), . [CrossRef]

- Barr, E.T.; Harman, M.; McMinn, P.; Shahbaz, M.; Yoo, S. The Oracle Problem in Software Testing: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2015, 41, 507–525. [CrossRef]

- Unterkalmsteiner, M.; Feldt, R.; Gorschek, T. A taxonomy for requirements engineering and software test alignment. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2014, 23. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Wan-Kadir, W.M.; Ibrahim, N.; Shah, M.A.; Younas, M.; Khan, A.; Zareei, M.; Alanazi, F. Automated test case generation from requirements: A systematic literature review. Computers, Materials and Continua 2021, 67, 1819–1833.

- Unterkalmsteiner, M.; Feldt, R.; Gorschek, T. A taxonomy for requirements engineering and software test alignment. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2014, 23. [CrossRef]

- Garousi, V.; Joy, N.; Keles, A.B. AI-powered test automation tools: A systematic review and empirical evaluation. ArXiv 2024, abs/2409.00411. [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.; Rumpe, B. Engineering Autonomous Driving Software. ArXiv 2014, abs/1409.6579. [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Madeyski, L.; Budgen, D. SEGRESS: Software engineering guidelines for reporting secondary studies. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2022, 49, 1273–1298. [CrossRef]

- ur Rehman, T.; Khan, M.N.A.; Riaz, N. Analysis of requirement engineering processes, tools/techniques and methodologies. International Journal of Information Technology and Computer Science (IJITCS) 2013, 5, 40.

- Arora, C.; Grundy, J.; Abdelrazek, M., Advancing Requirements Engineering Through Generative AI: Assessing the Role of LLMs. In Generative AI for Effective Software Development; Nguyen-Duc, A.; Abrahamsson, P.; Khomh, F., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 129–148. [CrossRef]

- Glinz, M. A glossary of requirements engineering terminology. Standard Glossary of the Certified Professional for Requirements Engineering (CPRE) Studies and Exam, Version 2011, 1, 56.

- Pohl, K. Requirements engineering: fundamentals, principles, and techniques; Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated, 2010.

- Zowghi, D.; Coulin, C. Requirements elicitation: A survey of techniques, approaches, and tools. Engineering and managing software requirements 2005, pp. 19–46. [CrossRef]

- Kotonya, G.; Sommerville, I. Requirements engineering: processes and techniques; Wiley Publishing, 1998.

- Chung, L.; Nixon, B.A.; Yu, E.; Mylopoulos, J. Non-functional requirements in software engineering; Vol. 5, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Sneha, K.; Malle, G.M. Research on software testing techniques and software automation testing tools. In Proceedings of the 2017 international conference on energy, communication, data analytics and soft computing (ICECDS). IEEE, 2017, pp. 77–81. [CrossRef]

- Alaqail, H.; Ahmed, S. Overview of software testing standard ISO/IEC/IEEE 29119. International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security (IJCSNS) 2018, 18, 112–116.

- Rafi, D.M.; Moses, K.R.K.; Petersen, K.; Mäntylä, M.V. Benefits and limitations of automated software testing: Systematic literature review and practitioner survey. In Proceedings of the 2012 7th international workshop on automation of software test (AST). IEEE, 2012, pp. 36–42. [CrossRef]

- Deming, C.; Khair, M.A.; Mallipeddi, S.R.; Varghese, A. Software Testing in the Era of AI: Leveraging Machine Learning and Automation for Efficient Quality Assurance. Asian Journal of Applied Science and Engineering 2021, 10, 66–76.

- Balaji, S.; Murugaiyan, M.S. Waterfall vs. V-Model vs. Agile: A comparative study on SDLC. International Journal of Information Technology and Business Management 2012, 2, 26–30.

- Mathur, S.; Malik, S. Advancements in the V-Model. International Journal of Computer Applications 2010, 1, 29–34.

- Atoum, I.; Baklizi, M.K.; Alsmadi, I.; Otoom, A.A.; Alhersh, T.; Ababneh, J.; Almalki, J.; Alshahrani, S.M. Challenges of software requirements quality assurance and validation: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 137613–137634. [CrossRef]

- Unterkalmsteiner, M.; Gorschek, T.; Feldt, R.; Klotins, E. Assessing requirements engineering and software test alignment—Five case studies. Journal of systems and software 2015, 109, 62–77. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.; Vakkalanka, S.; Kuzniarz, L. Guidelines for conducting systematic mapping studies in software engineering: An update. Information and Software Technology 2015, 64, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th international conference on evaluation and assessment in software engineering, 2014, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Shamsujjoha, M.; Grundy, J.; Li, L.; Khalajzadeh, H.; Lu, Q. Developing mobile applications via model driven development: A systematic literature review. Information and Software Technology 2021, 140, 106693. [CrossRef]

- Naveed, H.; Arora, C.; Khalajzadeh, H.; Grundy, J.; Haggag, O. Model driven engineering for machine learning components: A systematic literature review. Information and Software Technology 2024, p. 107423. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Wan-Kadir, W.M.; Ibrahim, N.; Shah, M.A.; Younas, M.; Khan, A.; Zareei, M.; Alanazi, F. Automated test case generation from requirements: A systematic literature review. Computers, Materials and Continua 2021, 67, 1819–1833.

- Klaus, P.; Chris, R. Requirements Engineering Fundamentals, 1st ed.; Rocky Nook, 2011.

- Wagner, S.; Fernández, D.M.; Felderer, M.; Vetrò, A.; Kalinowski, M.; Wieringa, R.; Pfahl, D.; Conte, T.; Christiansson, M.T.; Greer, D.; et al. Status quo in requirements engineering: A theory and a global family of surveys. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology (TOSEM) 2019, 28, 1–48. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Baldwa, S.; Jambavalikar, S.M.; Murthy, L.B.; Krishna, A. Software functional and non-function requirement classification using word-embedding. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications. Springer, 2022, pp. 167–179. [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, A. Scenario-based requirements analysis. Requirements engineering 1998, 3, 48–65. [CrossRef]

- De Landtsheer, R.; Letier, E.; Van Lamsweerde, A. Deriving tabular event-based specifications from goal-oriented requirements models. Requirements Engineering 2004, 9, 104–120. [CrossRef]

- Van Lamsweerde, A. Goal-oriented requirements engineering: A guided tour. In Proceedings of the Proceedings fifth ieee international symposium on requirements engineering. IEEE, 2001, pp. 249–262. [CrossRef]

- Mordecai, Y.; Dori, D. Model-based requirements engineering: Architecting for system requirements with stakeholders in mind. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Systems Engineering Symposium (ISSE). IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Alhoshan, W.; Ferrari, A.; Letsholo, K.J.; Ajagbe, M.A.; Chioasca, E.V.; Batista-Navarro, R.T. Natural language processing for requirements engineering: A systematic mapping study. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–41. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, B.; Wang, R. Generating Test Scenarios using SysML Activity Diagram. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Dependable Systems and Their Applications (DSA), 2021, pp. 257–264. [CrossRef]

- Hooda, I.; Chhillar, R. A review: study of test case generation techniques. International Journal of Computer Applications 2014, 107, 33–37.

- Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q. Software testing with large language models: Survey, landscape, and vision. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2024. [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.G.; Walkinshaw, N.; Hierons, R.M. Test case generation for agent-based models: A systematic literature review. Information and Software Technology 2021, 135, 106567. [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Burke, E.K.; Chen, T.Y.; Clark, J.; Cohen, M.B.; Grieskamp, W.; Harman, M.; Harrold, M.J.; McMinn, P.; Bertolino, A.; et al. An orchestrated survey of methodologies for automated software test case generation. Journal of systems and software 2013, 86, 1978–2001. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, F.; Shen, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. A Survey on Large Language Models for Code Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.00515 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Azab, S.; Abdelhamid, Y. Source-Code Generation Using Deep Learning: A Survey. In Proceedings of the EPIA Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Springer, 2023, pp. 467–482. [CrossRef]

- Gurcan, F.; Dalveren, G.G.M.; Cagiltay, N.E.; Roman, D.; Soylu, A. Evolution of Software Testing Strategies and Trends: Semantic Content Analysis of Software Research Corpus of the Last 40 Years. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 106093–106109. [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.A. Comprehensive study of software testing: Categories, levels, techniques, and types. International Journal of Advance Research, Ideas and Innovations in Technology 2019, 5, 32–40.

- Atifi, M.; Mamouni, A.; Marzak, A. A comparative study of software testing techniques. In Proceedings of the Networked Systems: 5th International Conference, NETYS 2017, Marrakech, Morocco, May 17-19, 2017, Proceedings 5. Springer, 2017, pp. 373–390. [CrossRef]

- IEEE Standard for System, Software, and Hardware Verification and Validation - Redline. IEEE Std 1012-2016 (Revision of IEEE Std 1012-2012/ Incorporates IEEE Std 1012-2016/Cor1-2017) - Redline 2017, pp. 1–465.

- Tran, H.K.V.; Unterkalmsteiner, M.; Börstler, J.; bin Ali, N. Assessing test artifact quality—A tertiary study. Information and Software Technology 2021, 139, 106620. [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y.W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural computation 2006, 18, 1527–1554. [CrossRef]

- Van der Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. Journal of machine learning research 2008, 9.

- Loucopoulos, P.; Karakostas, V. System requirements engineering; McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1995.

- Sommerville, I. Software engineering 9th 2011.

- Loniewski, G.; Insfran, E.; Abrahão, S. A systematic review of the use of requirements engineering techniques in model-driven development. In Proceedings of the Model Driven Engineering Languages and Systems: 13th International Conference, MODELS 2010, Oslo, Norway, October 3-8, 2010, Proceedings, Part II 13. Springer, 2010, pp. 213–227. [CrossRef]

- Bruel, J.M.; Ebersold, S.; Galinier, F.; Naumchev, A.; Mazzara, M.; Meyer, B. Formality in software requirements. CoRR 2019.

- Nikitin, D. SPECIFICATION FORMALIZATION OF STATE CHARTS FOR COMPLEX SYSTEM MANAGEMENT. Bulletin of National Technical University" KhPI". Series: System Analysis, Control and Information Technologies 2023, pp. 104–109. [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, S.; Minhas, N.M. Integrating Formal Methods in XP-A Conceptual Solution. Journal of Software Engineering and Applications 2014, 7, 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Dulac, N.; Viguier, T.; Leveson, N.; Storey, M.A. On the use of visualization in formal requirements specification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings IEEE Joint International Conference on Requirements Engineering. IEEE, 2002, pp. 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Committee, I.C.S.S.E.S.; Board, I.S.S. IEEE recommended practice for software requirements specifications; Vol. 830, IEEE, 1998.

- Henderson-Sellers, B. UML-the Good, the Bad or the Ugly? Perspectives from a panel of experts. Software & Systems Modeling 2005, 4.

- Veizaga, A.; Alferez, M.; Torre, D.; Sabetzadeh, M.; Briand, L. On systematically building a controlled natural language for functional requirements. Empirical Software Engineering 2021, 26, 79. [CrossRef]

- Pa, N.C.; Zain, A.M. A survey of communication content in software requirements elicitation involving customer and developer 2011.

- Barata, J.C.; Lisbôa, D.; Bastos, L.C.; Neto, A.G.S.S. Agile requirements engineering practices: a survey in Brazilian software development companies 2022. [CrossRef]

- Barr, E.T.; Harman, M.; McMinn, P.; Shahbaz, M.; Yoo, S. The Oracle Problem in Software Testing: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2015, 41, 507–525. [CrossRef]

- Duque-Torres, A.; Klammer, C.; Pfahl, D.; Fischer, S.; Ramler, R. Towards Automatic Generation of Amplified Regression Test Oracles. 2023 49th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications (SEAA) 2023, pp. 332–339. [CrossRef]

- Molina, F.; Gorla, A. Test Oracle Automation in the era of LLMs. ArXiv 2024, abs/2405.12766. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mäntylä, M.; Liu, Z.; Markkula, J.; Raulamo-Jurvanen, P. Improving test automation maturity: A multivocal literature review. Software Testing 2022, 32. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hall, P.A.; May, J.H. Software unit test coverage and adequacy. Acm computing surveys (csur) 1997, 29, 366–427. [CrossRef]

- Sykora, K.; Ahmed, B.S.; Bures, M. Code Coverage Aware Test Generation Using Constraint Solver. ArXiv 2020, abs/2009.02915. [CrossRef]

- Tufano, M.; Chandel, S.; Agarwal, A.; Sundaresan, N.; Clement, C.B. Predicting Code Coverage without Execution. ArXiv 2023, abs/2307.13383. [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, O.P.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Bailey, J.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering–a systematic literature review. Information and software technology 2009, 51, 7–15. [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 |

| Terms Group | Terms |

|---|---|

| Test Group | test* |

| Requirement Group | requirement* OR use case* OR user stor* OR specification* |

| Software Group | software* OR system* |

| Method Group | generat* OR deriv* OR map* OR creat* OR extract* OR design* OR priorit* OR construct* OR transform* |

| Criterion ID | Criterion Description |

|---|---|

| S01 | Papers written in English. |

| S02-1 | Papers in the subjects of "Computer Science" or "Software Engineering". |

| S02-2 | Papers published on software testing-related issues. |

| S03 | Papers published from 1991 to the present. |

| S04 | Papers with accessible full text. |

| ID | Description |

|---|---|

| Inclusion Criteria | |

| I01 | Papers about requirements-driven automated system testing or acceptance testing generation, or studies that generate system-testing-related artifacts. |

| I02 | Peer-reviewed studies that have been used in academia with references from literature. |

| Exclusion Criteria | |

| E01 | Studies that only support automated code generation, but not test-artifact generation. |

| E02 | Studies that do not use requirements-related information as an input. |

| E03 | Papers with fewer than 5 pages (1-4 pages). |

| E04 | Non-primary studies (secondary or tertiary studies). |

| E05 | Vision papers and grey literature (unpublished work), books (chapters), posters, discussions, opinions, keynotes, magazine articles, experience, and comparison papers. |

| Venue Names | Type | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| IEEE International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE) | Conference | 6 |

| IEEE International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability, and Security (QRS) | Conference | 6 |

| IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification, and Validation (ICST) Workshops | Workshop | 5 |

| IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering (TSE) | Journal | 4 |

| Software Quality Journal (SQJ) | Journal | 3 |

| Science of Computer Programming | Journal | 3 |

| IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation (ICST) | Conference | 3 |

| International Conference on Quality Software (QSIC) | Conference | 3 |

| International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering (ENASE) | Conference | 3 |

| Innovations in Systems and Software Engineering | Journal | 3 |

| IEEE International Workshop on Requirements Engineering and Testing (RET) | Workshop | 3 |

| ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes | Journal | 3 |

| Journal of Systems and Software (JSS) | Journal | 2 |

| IEEE International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE) | Conference | 2 |

| IEEE International Requirements Engineering Conference Workshops (REW) | Workshop | 2 |

| International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management | Journal | 2 |

| International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS) | Conference | 2 |

| International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Technology (ICETET) | Conference | 2 |

| Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science | Journal | 2 |

| Australian Software Engineering Conference (ASWEC) | Conference | 2 |

| International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications | Journal | 2 |

| Electronics | Journal | 2 |

| Target Software Systems | Paper ID | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| General Software | P2, P3, P5, P6, P7, P8, P9, P10, P13, P14, P15, P16, P17, P18, P19, P23, P24, P25, P30, P31, P34, P35, P36, P37, P39, P40, P41, P42, P43, P46, P51, P52, P53, P54, P55, P57, P62, P63, P65, P68, P69, P70, P71, P73, P74, P75, P76, P78, P79, P82, P83, P84, P86, P88, P89, P92, P93, P96, P99, P100, P103, P104, P105, P106, P109, P114, P116, P117, P118, P119, P121, P122, P124, P125, P126, P127, P128, P129, P130, P132, P135, P136, P137, P138, P139, P141, P142, P143, P144, P145, P146, P148, P150, P151, P152, P153, P157, P158, P159, P160 | 100 |

| Embedded System | P29, P33, P38, P60, P61, P94, P98, P111, P113, P140, P147, P149, P155, P161 | 14 |

| Web Services System | P1, P4, P11, P21, P56, P67, P112 | 7 |

| Safety-Critical System | P27, P50, P72, P101, P123, P131 | 6 |

| Timed Data-flow Reactive System | P80, P108, P133, P134 | 4 |

| Reactive System | P45, P107, P156 | 3 |

| Real-time Embedded System | P26, P64, P115 | 3 |

| Product Line System | P32, P48 | 2 |

| Object-Oriented System | P28, P66 | 2 |

| Telecommunication Application | P22, P95 | 2 |

| Automotive System | P59, P102 | 2 |

| Space Application | P44 | 1 |

| SOA-based System | P90 | 1 |

| Labeled Transition System | P49 | 1 |

| Healthcare Application | P110 | 1 |

| Event-driven System | P154 | 1 |

| Cyber-Physical System | P58 | 1 |

| Core Business System | P20 | 1 |

| Concurrent System | P12 | 1 |

| Complex Dynamic System | P91 | 1 |

| Aspect-Oriented Software | P47 | 1 |

| Agricultural Software | P77 | 1 |

| Requirements Types | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Requirements | Almost all papers support functional requirements, except P18, P74, P79, P155, P156. | 152 |

| Non-functional Requirements | P2, P33, P41, P48, P50, P51, P56, P57, P61, P68, P69, P71, P73, P76, P79, P83, P88, P90, P96, P116, P123, P124, P146, P155, P156, P157, P161 | 27 |

| User Requirements | P2, P43, P74, P84, P88, P92, P119, P121, P139, P142 | 10 |

| Constraint Requirements | P86, P91, P94, P100, P101, P114, P161 | 7 |

| Business Requirements | P18, P51, P74, P89, P94, P95, P137 | 7 |

| Implementation Requirements | P95 | 1 |

| Requirements Notations | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| NL requirements | P23 (PURE dataset), P26,P34 (Textual User Story), P37 (Usage Scenario), P38 (NL Requirements), P39 (Scenario Specification), P40 (Test requirements), P41 (Textual Use Case), P42,P44, P52 (Textual Use Case), P54,P55, P60 (Textual Use Case), P63,P67,P71 (Template-based), P77 (Scenario), P82,P84,P87, P88 (Textual Use Case), P93,P98,P102,P104,P106,P113,P116,P117, P121 (Claret Format), P122,P126,P127,P128,P129,P130,P135,P136,P138,P139,P140, P147 (Technical Requirements Specification), P149,P151, P157 (Positive and negative pair), P160 | 47 |

| UML | P4,P7,P8,P10,P11,P15,P16,P17, P25 (Activity Diagram), P28 (Sequence Diagram), P35,P46,P49,P53,P56, P57,P66,P73,P74,P75,P89,P90, P96 (UML MAP), P99, P109 (Sequence Diagram), P110,P115,P119,P123, P145 (Activity Diagram), P152 (Activity Diagram), P153 (Sequence Diagram), P161 (Modeling and Analysis of Real Time and Embedded Systems) | 33 |

| Other | P18 (Semi-Structured NL), P21 (OWL-S Model), P29 (State-Transition Table), P58 (Formal NL Specification), P64 (Structured Requirements Specification), P65 (Class Diagram, Restricted-form of NL), P68 (Semi-Formal Requirements Description), P69 (Requirements Specification Modeling Language), P94 (Safety Requirements Specification), P107 (Expressive Decision Table), P125 (Textual Use Case), P131 (Functional Diagram), P137 (Requirement Description Modeling Language), P142 (Requirements Dependency Mapping), P143 (Specification and Description Language), P144 (Behavior Tree), P148 (Domain-Specific Modeling Language), P150 (Statechart Diagram), P158 (Risk Factor), P159 (Requirement Traceability Matrix) | 20 |

| Custom | P1 (Custom Metamodel), P3 (Constraint-based Requirements Specification), P9 (Custom CNL), P12 (Semi-Structured NL Extended Lexicon), P14 (Interaction Overview Diagram), P27 (SCADE Specification), P30 (Extended SysML), P32 (RUCM with PL extension), P47 (Aspect-Oriented PetriNet), P50 (Safety SysML State Machine), P59 (OCL-Combined AD), P62 (State-based Use Case), P86 (Contract Language for Functional PF Requirements (UML)), P92 (Textual Scenario based on tabular expression), P103 (NL requirements (Language Extended Lexicon)), P111 (Specification language for Embedded Network Systems), P114 (Requirements Specification Modeling Language) | 17 |

| CNL | P2, P5 (RUCM), P6 (Use Case Specification Language (USL)), P22 (RUCM), P24 (RUCM), P45, P61 (RUCM), P80, P83 (Restricted Misuse Case Modeling), P108, P112,P132,P133,P134,P156 | 15 |

| Use Case Description Model | P13 (Use Case Description Model), P19 (Use Case Description Model), P36 (Use Case Description Model), P43 (Use Case Description Model), P48 (Use Case Description Model), P70 (Use Case Description Model), P76 (Use Case Description Model) | 7 |

| Requirements Priorities | P118 (Customer-assigned priorities, Developer-assigned priorities), P141 (Customer Assigned Priority), P146 (Stakeholder Priority) | 3 |

| SCR | P33,P78,P154 | 3 |

| DSL | P91,P100,P101 | 3 |

| Formal Equation | P79,P124,P155 | 3 |

| Cause-Effect-Graph | P20,P95 | 2 |

| OCL | P72,P105 | 2 |

| RSL | P31,P51 | 2 |

| Techniques | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Rule-based | P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7, P8, P9, P10, P11, P12, P13, P14, P16, P17, P18, P19, P21, P22, P26, P28, P31, P32, P33, P34, P35, P36, P38, P40, P41, P42, P43, P44, P45, P46, P47, P48, P49, P51, P52, P55, P56, P57, P59, P60, P61, P64, P65, P66, P67, P68, P69, P70, P71, P72, P73, P74, P75, P76, P77, P78, P80, P83, P84, P86, P88, P90, P91, P92, P95, P96, P99, P100, P101, P102, P103, P104, P106, P107, P108, P109, P111, P112, P113, P114, P115, P116, P117, P118, P119, P121, P123, P124, P125, P126, P127, P129, P131, P132, P133, P134, P135, P136, P137, P138, P140, P141, P142, P143, P144, P145, P147, P148, P149, P150, P151, P154, P156, P157, P158, P161 | 122 |

| MetaModel-based | P1, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7, P8, P9, P11, P13, P14, P15, P16, P20, P21, P22, P24, P25, P27, P28, P29, P30, P31, P32, P33, P35, P36, P37, P39, P43, P44, P45, P46, P47, P48, P49, P50, P51, P53, P54, P56, P57, P58, P59, P60, P61, P62, P64, P65, P66, P69, P70, P71, P72, P74, P75, P76, P77, P78, P79, P80, P88, P90, P91, P92, P94, P95, P96, P99, P100, P101, P103, P104, P105, P108, P109, P110, P114, P115, P116, P121, P123, P129, P131, P132, P133, P134, P135, P136, P137, P140, P143, P144, P146, P147, P148, P149, P150, P152, P154, P155, P161 | 102 |

| NLP-Pipeline-based | P2, P9, P18, P19, P22, P23, P24, P28, P32, P36, P41, P42, P43, P44, P45, P48, P52, P55, P57, P60, P62, P63, P65, P68, P70, P71, P76, P77, P80, P82, P83, P98, P106, P108, P115, P116, P117, P122, P126, P127, P130, P132, P133, P134, P135, P137, P139, P156, P157, P159, P160 | 51 |

| Graph-based | P6, P8, P12, P13, P17, P19, P25, P26, P28, P33, P42, P47, P50, P53, P57, P59, P61, P65, P66, P70, P71, P74, P77, P78, P86, P88, P89, P92, P98, P103, P116, P121, P127, P136, P139, P145, P153, P161 | 38 |

| Machine Learning-based | P18, P23, P52, P93, P98, P122, P126, P127, P128, P159, P160 | 11 |

| Rule Methods | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Constraint | P1, P2, P3, P4, P9, P10, P12, P16, P17, P18, P21, P22, P26, P28, P31, P32, P33, P35, P36, P38, P41, P42, P43, P44, P45, P46, P47, P48, P49, P51, P55, P60, P65, P66, P67, P69, P71, P73, P75, P77, P83, P84, P92, P96, P99, P108, P109, P111, P112, P113, P115, P116, P117, P123, P129, P135, P136, P137, P141, P142, P143, P150, P151, P154, P156, P158 | 68 |

| Condition | P3, P4, P6, P7, P8, P11, P14, P16, P28, P32, P34, P40, P45, P47, P51, P52, P56, P57, P59, P61, P64, P68, P69, P70, P72, P73, P76, P78, P80, P86, P88, P90, P91, P95, P101, P102, P104, P106, P107, P111, P114, P118, P119, P124, P125, P126, P127, P131, P132, P133, P134, P137, P138, P140, P141, P142, P144, P145, P147, P148, P149, P156, P161 | 61 |

| Template | P5, P13, P19, P43, P48, P74, P99, P100, P103, P106, P108, P109, P112, P116, P119, P121, P123, P145, P157 | 19 |

| MetaModel Methods | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Other | P1, P3, P11, P15, P25, P28, P29, P32, P37, P39, P43, P46, P48, P50, P54, P57, P58, P60, P61, P64, P70, P71, P74, P75, P76, P77, P80, P90, P91, P92, P94, P95, P100, P101, P103, P104, P116, P137, P140, P146, P148, P155 | 44 |

| Diagram-based Models | P8, P13, P14, P16, P20, P22, P33, P47, P49, P53, P56, P65, P66, P72, P99, P105, P108, P109, P110, P115, P121, P123, P132, P135, P150, P152 | 25 |

| Formal and Logic-based Models | P45, P62, P69, P78, P79, P96, P129, P131, P133, P134, P147 | 11 |

| Domain-Specific Modeling Languages | P27, P30, P31, P51, P59, P114, P161 | 7 |

| State-based and Transition Models | P36, P44, P88, P143, P149, P154 | 6 |

| Use Case Models | P4, P5, P6, P7, P24 | 5 |

| Behavioral Models | P35, P136, P144 | 3 |

| Ontology and Knowledge-based Models | P9, P21 | 2 |

| Graph and Flow-based Models | P140 | 1 |

| Repre. Types | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Rule | P2, P3, P7, P9, P10, P19, P22, P24, P26, P28, P34, P36, P39, P43, P49, P50, P51, P55, P55, P57, P58, P64, P66, P68, P68, P71, P71, P76, P78, P80, P101, P102, P104, P107, P109, P110, P111, P113, P113, P114, P118, P121, P125, P129, P133, P134, P136, P140, P142, P143, P146, P156, P159 | 51 |

| Model | P1, P4, P7, P8, P11, P15, P18, P20, P21, P25, P25, P27, P30, P31, P32, P33, P40, P43, P45, P47, P50, P51, P52, P58, P59, P61, P62, P65, P70, P72, P73, P74, P74, P75, P76, P80, P100, P104, P114, P124, P132, P133, P137, P137, P145, P147, P148, P150, P152, P154, P155 | 48 |

| Graph | P3, P9, P10, P12, P13, P14, P16, P17, P19, P30, P33, P35, P37, P44, P46, P53, P54, P56, P57, P66, P77, P108, P109, P110, P115, P116, P127, P128, P135, P136, P139, P140, P143, P144, P149, P150, P152, P153, P153 | 38 |

| Test Case | P5, P6, P21, P29, P151 | 5 |

| Test Formats | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Test Case | P1,P2,P3,P4,P5,P6,P7,P9,P11 , P13 (optimized), P15,P16,P19,P21,P23,P24,P25,P26,P27,P28,P30 , P31 (acceptance), P32,P35,P36,P37 , P38 (prioritized), P39 (prioritized), P43 , P44 (system and acceptance), P45,P48,P49,P50,P51 , P52 (tabular), P54,P55,P56,P57, P58 (failure-revealing), P59,P60, P61,P62,P68, P70,P72,P74,P76,P77,P79,P80 , P82 (prioritized), P83 (security), P84 , P86,P88,P90,P91,P92,P94,P95,P96,P98,P99,P100,P101,P102,P103 , P104 (prioritized), P105,P106,P107,P108,P109,P110,P111,P112 , P113 (passive), P114,P116 , P118 (prioritized), P119 , P121 , P122, P123,P124,P125,P127,P128,P130,P131,P132,P133,P134,P135 , P136 (prioritized), P138 (prioritized), P140 , P141 (prioritized), P142 (prioritized), P143 , P144 (prioritized), P145 , P146 (prioritized), P147,P148,P149,P151,P153,P156,P157 , P158 (prioritized), P159 (prioritized), P161 | 116 |

| Test Scenario | P8,P11,P12,P28,P29,P31,P32,P33,P51, P53 (prioritized), P56,P57,P62,P64,P65, P66 (prioritized), P67 (prioritized), P73,P95,P96,P129,P145,P160,P161 | 24 |

| Other | P14 (Test-Path), P20 (Test Procedures), P21 (Test Mutant), P26 (Scenario Tree), P34 (Test Verdict), P41 (Key Value Pairs), P47 (Test Requirements), P71 (Test Plan, Acceptance Criteria), P75 (Test Description), P112 (Interface Prototype), P115 (Test Bench), P122 (Test Suggestion), P140 (Function Chart), P154 (Safety Properties) | 14 |

| Test Model | P18, P22, P73, P80,P137, P150 | 6 |

| Test Report | P15, P29, P57, P89, P149 | 5 |

| Test Suite | P40, P79, P95, P152, P155 | 5 |

| Test Oracle | P7, P34, P63, P91 | 4 |

| Test Sequence | P7, P17, P69, P78 | 4 |

| Test Guidance | P93, P117, P126 | 3 |

| Test Specification | P5, P6, P20 | 3 |

| Test Script | P2, P51, P75 | 3 |

| Test Graph | P42, P125, P139 | 3 |

| Test Goal | P10, P46 | 2 |

| Traceability Matrix | P84, P147 | 2 |

| Test Coverages | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Requirements Coverage | P2, P16, P22, P26, P33, P38, P39, P41, P42, P45, P49, P60, P63, P71, P72, P74, P75, P82, P84, P91, P93, P95, P98, P102, P104, P105, P106, P108, P109, P112, P113, P115, P117, P118, P121, P123, P124, P125, P127, P133, P136, P138, P141, P145, P146, P153, P155, P156, P158, P159, P161 | 52 |

| Behavioral/Scenario Coverage | P1, P4, P6, P7, P11, P24, P32, P37, P46, P51, P52, P53, P54, P56, P57, P58, P62, P64, P66, P67, P68, P70, P73, P77, P78, P89, P92, P96, P111, P114, P129, P130, P144, P148, P150, P151, P154, P157, P160 | 37 |

| Path Coverage | P5, P8, P12, P14, P17, P30, P35, P55, P59, P65, P88, P103, P110, P135, P143, P152 | 16 |

| Functional Coverage | P13, P25, P27, P29, P61, P94, P107, P119, P122, P131, P134 | 11 |

| Use Case Coverage | P9, P10, P15, P19, P43, P47, P76, P83, P86 | 9 |

| Not Specified | P21, P34, P48, P80, P90, P126, P137, P139, P149 | 9 |

| Decision/Branch Coverage | P50, P100, P101, P132, P140, P147 | 6 |

| Statement Coverage | P23, P28, P36, P128, P142 | 5 |

| Other | P116 (Boundary Coverage), P44 (Combinatorial Coverage), P18 (Structural Coverage) | 3 |

| Model-Based Coverage | P20, P69, P79 | 3 |

| Rule-Based Coverage | P3, P31 | 2 |

| Code Coverage | P40, P99 | 2 |

| Benchmark Types | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Case Demonstration | P1, P2, P4, P6, P7, P8, P10, P11, P12, P13, P14, P16, P17, P21, P22, P26, P27, P35, P43, P46, P48, P49, P51, P53, P62, P64, P66, P67, P68, P69, P71, P74, P75, P77, P82, P84, P86, P89, P90, P92, P98, P99, P100, P105, P106, P111, P112, P114, P115, P119, P123, P124, P128, P132, P133, P134, P136, P141, P144, P145, P149, P150, P151, P152, P153, P155, P156, P159, P161 | 69 |

| Real Case Demonstration | P3, P5, P9, P12, P15, P18, P20, P23, P24, P25, P28, P29, P30, P32, P33, P34, P36, P37, P38, P42, P44, P45, P49, P50, P54, P55, P58, P59, P60, P61, P72, P78, P79, P80, P83, P88, P91, P94, P95, P101, P102, P107, P108, P109, P110, P113, P117, P118, P121, P123, P125, P126, P127, P129, P130, P131, P132, P134, P135, P137, P138, P140, P142, P147, P154, P160 | 66 |

| NA | P19, P31, P39, P40, P47, P52, P57, P63, P65, P70, P73, P76, P93, P96, P103, P104, P116, P122, P139, P143, P146, P148, P158 | 23 |

| Dataset Evaluation | P18, P41, P56, P157 | 4 |

| Software Platforms | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| NA | P19, P31, P39, P40, P47, P52, P57, P63, P65, P70, P73, P76, P93, P96, P103, P104, P116, P122, P139, P143, P146, P148, P158 | 23 |

| Automotive System | P5, P23, P24, P32, P45, P58, P59, P61, P79, P80, P98, P102, P107, P108, P115, P127, P128, P129, P154, P155 | 20 |

| Control System | P27, P29, P30, P42, P44, P60, P64, P78, P94, P111, P113, P121, P125, P132, P140, P142, P144, P161 | 18 |

| Safety System | P49, P50, P54, P71, P72, P78, P88, P89, P102, P108, P117, P126, P131, P132, P135, P147, P154 | 17 |

| Order System | P4, P10, P12, P16, P17, P48, P53, P55, P66, P67, P68, P114, P132, P133, P134, P152 | 16 |

| Business System | P18, P20, P23, P36, P37, P68, P77, P90, P91, P92, P124, P160 | 12 |

| Resource Management System | P5, P25, P26, P33, P34, P68, P82, P118, P121, P126, P136, P157 | 12 |

| Workforce System | P8, P22, P23, P28, P41, P46, P74, P75, P86, P95, P99, P145 | 12 |

| Healthcare System | P15, P17, P34, P38, P41, P51, P58, P83, P110, P119, P159 | 11 |

| ATM System | P12, P13, P17, P22, P35, P105, P109, P151, P153, P155 | 10 |

| Aerospace System | P28, P35, P69, P80, P100, P101, P130, P149, P156 | 9 |

| Banking System | P5, P21, P43, P68, P121 | 5 |

| Authentication System | P1, P84, P106, P112 | 4 |

| Mobile Application | P2, P34, P62, P68 | 4 |

| Library System | P6, P7, P9 | 3 |

| Booking System | P55, P56, P150 | 3 |

| Education System | P11, P123, P159 | 3 |

| Other | P137, P138, P141 | 3 |

| Database System | P3, P117 | 2 |

| Examination System | P14 | 1 |

| Usability | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| The methodology explanation | Almost all of the papers enable clear methodology explanation, except P35, P36, P38, P138, P140, P156, P158 | 154 |

| Case example | P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P7, P8, P9, P11, P12, P13, P14, P15, P16, P17, P18, P21, P22, P23, P24, P26, P27, P28, P29, P32, P33, P34, P35, P36, P37, P38, P39, P40, P41, P42, P43, P44, P46, P48, P49, P50, P55, P58, P59, P60, P61, P62, P64, P66, P67, P68, P69, P71, P78, P79, P83, P84, P86, P88, P89, P90, P91, P92, P93, P94, P95, P96, P98, P99, P101, P102, P107, P108, P109, P110, P111, P112, P113, P114, P115, P116, P117, P118, P119, P121, P123, P124, P125, P126, P127, P129, P130, P131, P132, P133, P134, P135, P136, P137, P138, P140, P141, P143, P144, P145, P146, P147, P148, P149, P150, P151, P152, P154, P155, P156, P158, P159, P160, P161 | 120 |

| Discussion | P1, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7, P8, P9, P10, P11, P12, P13, P15, P17, P18, P19, P20, P21, P22, P23, P24, P25, P26, P27, P28, P29, P31, P32, P33, P35, P36, P37, P38, P40, P41, P42, P43, P44, P45, P46, P47, P48, P49, P50, P51, P52, P54, P55, P56, P58, P59, P60, P61, P62, P63, P64, P65, P66, P67, P68, P69, P70, P71, P72, P73, P75, P76, P77, P78, P79, P80, P82, P83, P84, P86, P88, P92, P94, P96, P99, P104, P113, P117, P121, P127, P128, P129, P130, P131, P132, P134, P135, P137, P141, P144, P147, P152, P154, P155, P156, P157, P158, P159, P160, P161 | 105 |

| Experiment | P2, P3, P5, P7, P9, P12, P13, P14, P15, P17, P18, P22, P23, P24, P26, P27, P28, P30, P32, P34, P35, P37, P39, P40, P41, P42, P43, P44, P45, P52, P53, P56, P58, P59, P61, P70, P71, P72, P76, P79, P80, P82, P83, P86, P89, P91, P95, P99, P101, P102, P107, P108, P110, P113, P117, P118, P121, P125, P127, P128, P129, P130, P131, P132, P133, P134, P135, P137, P138, P140, P141, P142, P154, P157, P159, P160, P161 | 77 |

| Limitations | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Limitations of Framework Design | P4, P8, P11, P12, P21, P22, P23, P28, P31, P32, P33, P35, P41, P44, P45, P46, P60, P62, P64, P67, P68, P86, P89, P91, P92, P102, P106, P109, P110, P117, P118, P121, P126, P131, P145, P146, P148, P150, P151, P156, P160 | 41 |

| NA | P14, P15, P16, P18, P26, P29, P83, P90, P93, P95, P98, P99, P101, P114, P119, P123, P124, P125, P133, P134, P137, P138, P139, P140, P141, P142, P158, P161 | 28 |

| Limitation of Evaluation or Demonstration | P7, P19, P39, P40, P48, P74, P75, P96, P100, P102, P105, P108, P110, P122, P129, P132, P143, P146, P153, P160 | 20 |

| Scalability to Large Systems | P10, P30, P32, P35, P38, P47, P50, P55, P56, P66, P70, P75, P78, P80, P84, P107, P111, P126, P128, P159 | 20 |

| Over Relying on Input Quality | P2, P17, P34, P36, P37, P43, P44, P51, P53, P55, P65, P71, P107, P127, P144, P157 | 16 |

| Complexity of Methodology | P3, P54, P62, P69, P72, P73, P76, P77, P79, P82, P94, P116, P147, P149, P154 | 15 |

| Automation (Methodology) | P6, P8, P24, P27, P38, P57, P58, P59, P107, P112, P115, P116 | 12 |

| Incomplete Requirements Coverage | P13, P61, P88, P105, P108, P113, P131, P136, P155, P156 | 10 |

| Automation (Test Implementation) | P2, P5, P25, P73, P104, P122, P130, P135 | 8 |

| Automation (Requirements Specification) | P1, P9, P68, P103, P117, P151, P152 | 7 |

| Requirements Ambiguities | P42, P49, P52 | 3 |

| Limitation of Implementation | P20, P63 | 2 |

| Time-Costing | P20, P39 | 2 |

| Additional Cost of Requirements Specification | P7 | 1 |

| Automation Levels | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Highly Automated | P2, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7, P8, P9, P10, P12, P16, P17, P18, P20, P22, P23, P24, P28, P29, P32, P41, P42, P43, P44, P47, P48, P49, P51, P53, P54, P56, P57, P59, P60, P69, P70, P71, P74, P75, P77, P78, P82, P83, P89, P91, P92, P93, P98, P100, P101, P102, P103, P105, P106, P107, P108, P109, P111, P112, P117, P124, P125, P126, P127, P132, P133, P134, P136, P137, P140, P145, P146, P149, P151, P153, P154, P160 | 77 |

| Semi-Automated | P19, P26, P27, P38, P46, P58, P63, P64, P68, P84, P86, P90, P94, P95, P99, P104, P110, P113, P114, P115, P116, P118, P119, P121, P122, P129, P130, P131, P135, P138, P139, P141, P142, P148, P150, P152, P155, P156, P161 | 39 |

| Fully Automated | P1, P11, P13, P14, P15, P21, P25, P30, P31, P33, P34, P35, P36, P37, P39, P40, P45, P50, P52, P55, P61, P62, P65, P66, P67, P72, P73, P76, P79, P80, P128, P143, P144, P147, P157 | 35 |

| Low Automation | P88, P96, P123, P158, P159 | 5 |

| Future Directions | Paper IDs | Num. |

|---|---|---|

| Extension to Other Coverage Criteria or Requirements | P5, P11, P13, P14, P15, P16, P17, P18, P21, P22, P23, P28, P30, P32, P34, P35, P36, P42, P44, P45, P46, P47, P48, P49, P50, P51, P53, P54, P55, P57, P58, P59, P60, P61, P62, P65, P66, P67, P68, P73, P75, P78, P86, P92, P95, P98, P100, P101, P102, P103, P104, P105, P106, P107, P108, P110, P129, P130, P132, P133, P134, P137, P145, P146, P147, P148, P150, P151, P152, P158, P159, P160 | 72 |

| Further Validation | P5, P6, P9, P14, P15, P19, P20, P21, P26, P38, P48, P54, P59, P72, P74, P75, P86, P89, P93, P96, P101, P108, P109, P110, P113, P115, P118, P119, P121, P125, P126, P127, P138, P140, P142, P143, P144, P145, P146, P156, P159, P160 | 42 |

| Completeness Improvement | P24, P35, P36, P40, P45, P51, P52, P69, P71, P79, P80, P89, P92, P93, P95, P96, P112, P117, P119, P125, P126, P128, P129, P131, P134, P138, P140, P142, P149, P154, P155, P157 | 32 |

| Automation Improvement | P4, P5, P6, P10, P11, P12, P46, P53, P56, P58, P67, P72, P73, P76, P88, P95, P104, P106, P115, P139, P144, P151, P152, P154 | 24 |

| Extension of Other Techniques | P9, P19, P20, P22, P27, P30, P31, P33, P34, P37, P43, P44, P63, P70, P71, P76, P77, P88, P94, P127, P128, P147, P153, P157 | 24 |

| Extension to Other Domains or Systems | P8, P10, P24, P26, P28, P29, P33, P41, P42, P47, P56, P61, P63, P64, P66, P69, P73, P77, P79, P80, P100, P102, P107, P135 | 24 |

| Extension to Other Phases or Test Patterns | P1, P2, P7, P12, P16, P21, P25, P26, P37, P51, P52, P57, P62, P65, P74, P98, P105, P106, P111, P112, P114, P137, P153, P156 | 24 |

| Performance Improvement | P4, P27, P42, P52, P94, P106, P107, P130, P132, P133, P138, P143, P149, P155 | 14 |

| Real Tool Development | P1, P7, P13, P54, P56, P64, P78, P110, P112, P113, P114, P116, P117, P140 | 14 |

| Benchmark Construction | P3, P39, P116, P139 | 4 |

| Traceability Improvement | P31, P39, P121, P137 | 4 |

| Robustness Improvement | P18, P118, P141 | 3 |

| NA | P82, P83, P84, P90, P91, P99, P122, P123, P124, P136, P161 | 11 |

| Conceptual Case Study | Real Case Study | NA | Dataset Evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Further Validation | 15 | 22 | 5 | 0 |

| Limitation of Demonstration or Evaluation | 14 | 13 | 3 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).