1. Introduction

Mixed methods research can be a powerful tool for analyzing complex processes and systems in health domains and allows researchers to answer different types of research questions that could not be answered by qualitative or quantitative methodologies alone [

1].

By incorporating the concept of breastfeeding, mixed methods research can be beneficial for researchers aiming to understand breastfeeding as a subjective and experiential phenomenon. This understanding is shaped by the relationships established with members of one's social network. Additionally, mixed methods research is useful when comparing various factors that influence the duration of breastfeeding, including biological, psychological, cultural, socioeconomic, and demographic aspects [

2,

3].

Factors such as prenatal and postnatal guidance provided by primary and hospital health services can significantly influence a mother's decision to initiate breastfeeding, as well as her ability to maintain and extend its duration. The combination of these variables, along with how women personally experience them, can either positively or negatively affect their decision-making regarding breastfeeding [

4,

5,

6].

To understand all these factors and their influence on breastfeeding outcomes, it is necessary to work with a methodology that allows for a more comprehensive perception, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative data [

7,

8]. Mixed methods research (MMR) combines qualitative (QUAL) and quantitative (QUAN) research techniques to address a variety of complex phenomena more completely than either approach alone [

9]. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a broad search for objective and subjective elements that help to achieve a multifaceted understanding of the outcome of breastfeeding in different contexts and cultures, which can be achieved by applying mixed methods in research. Thus, the aim is to map the scientific production on the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding developed from mixed methods research.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a scoping review that followed the methodology of the JBI and the PRISMA-ScR Checklist (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) [

10,

11].

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The review protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform, obtaining DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/589Z2. The JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [

10] was used to construct the review protocol.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: The PCC mnemonic suggested by the JBI [

11] – Population (women), Concept (breastfeeding, scoring the care processes and practices and the experiences of professionals and users) and Context (health centers that promote and support breastfeeding, such as hospitals, maternity wards and prenatal clinics) – was used to define the research question: “Which studies on the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding were developed using mixed methods?”

Protocols of previous reviews, completed or in progress on this topic, were not found in a search conducted on the OSF platform.

Studies focusing on the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding using mixed methods were included. More specifically, studies that highlighted breastfeeding care processes and practices, the experiences of healthcare? professionals and users (with breastfeeding?), conducted in all contexts of breastfeeding care were included. No limits on publication dates or language were imposed. Full-text publications available free of charge in journals accessible through the selected databases were retrieved

2.3. Research Strategy

The research was conducted in three stages [

11]. In the first stage, after the research question was developed, the DeCS/MeSH descriptors were identified and a bibliographic search was conducted in three databases: Google Scholar, Virtual Health Library (BVS), and National Library of Medicine (PubMed) in collaboration with a librarian. In the second stage, once the descriptors and keywords were defined in DeCS/MeSH, these were applied and combined in a search strategy adapted according to the specificities of the following databases: Essential: Medline/Pubmed, EMBASE (Elsevier), Cochrane; complementary sources: Lilacs/BVS, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL - Ebsco), SCOPUS (Elsevier), and Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics) and Repositories: BDTD - Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations, maintaining the similarities of combinations, and using the Boolean operators AND and OR (Tabela 1 -Sup 1). The search took place in December 2023. Finally, the third stage includes checking the reference lists of the selected studies after reading the full text to find potential complementary studies relevant to address the research questions.

Table 1.

Terms for the strategic search in information sources.

Table 1.

Terms for the strategic search in information sources.

| Database |

Search Strategy |

Medline

(Pubmed) |

# 1 (Women [mesh terms] OR Girls [tiab] OR Girl [tiab] OR Woman [tiab] OR Women's Groups [tiab] OR Women Groups[tiab] OR Women's Group [tiab] OR Pregnant Women [mesh terms])

# 2 (Breast Feeding [mesh terms] OR Breastfed [tiab] OR Breastfeeding [tiab] OR Breast Fed [tiab] OR Breast Feeding, Exclusive [tiab] OR Exclusive Breast Feeding [tiab] OR Breastfeeding, Exclusive [tiab] OR Exclusive Breastfeeding) AND (Maternal-Child Health Centers [mesh terms] OR Center, Maternal-Child Health [tiab] OR Centers, Maternal-Child Health [tiab] OR Health Center, Maternal-Child [tiab] OR Health Centers, Maternal-Child [tiab] OR Maternal Child Health Centers [tiab] OR Maternal-Child Health Center [tiab] OR Community Health Centers [mesh terms] OR Center, Community Health [tiab] OR Centers, Community Health [tiab] OR Community Health Center [tiab] OR Health Center, Community [tiab] OR Health Centers, Community OR Hospitals, Maternity [mesh terms] OR Maternity Hospitals [tiab] OR Hospital, Maternity [tiab] OR Maternity Hospital [tiab]) AND (Mixed methods)

|

2.4. Studies Selection

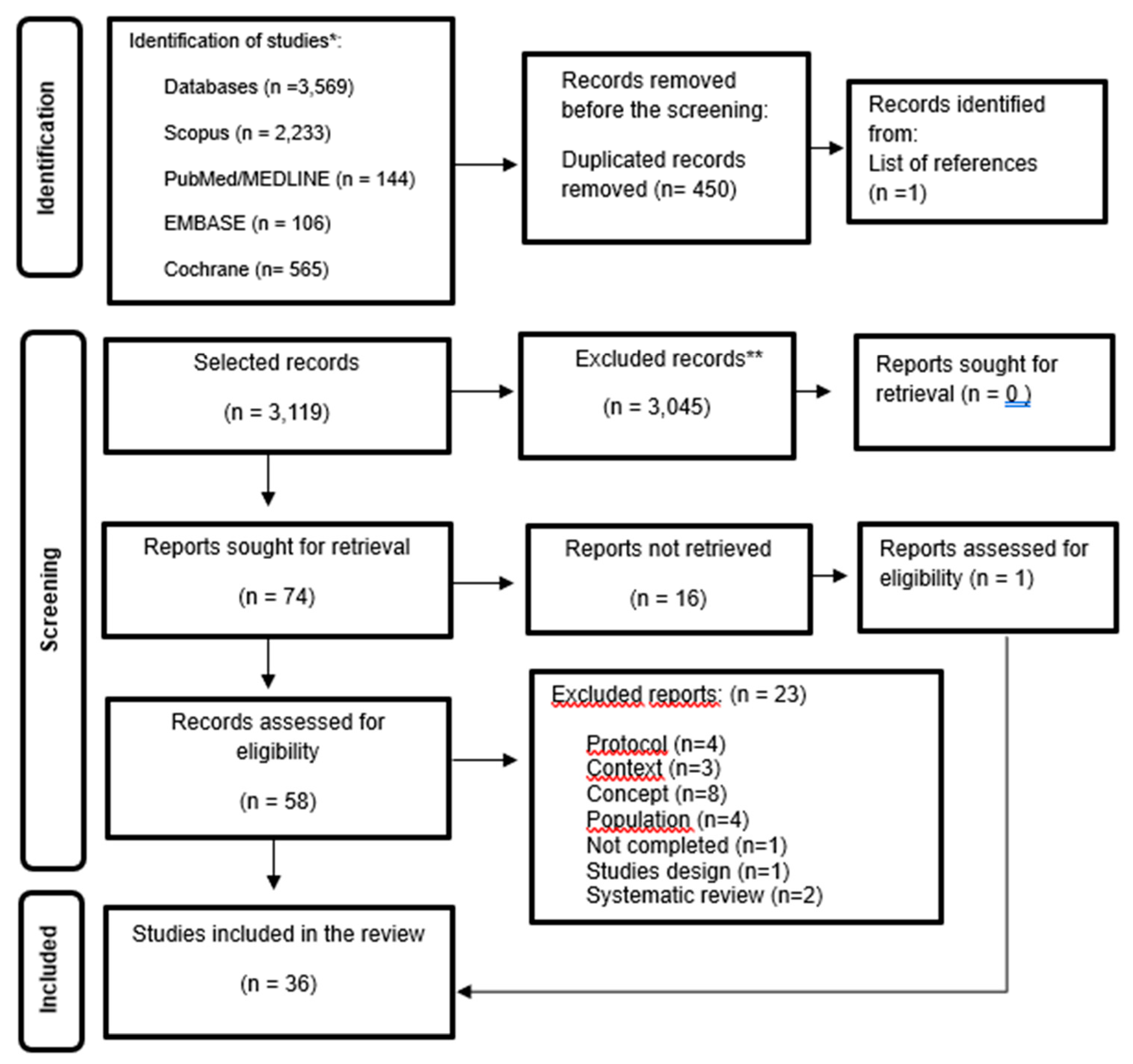

Rayyan was used for studies selection. Two researchers independently screened studies based on titles and abstracts. A third reviewer resolved conflicts on inclusion and exclusion. As recommended by the JBI, the flowchart model in

Figure 1 was used, detailing the studies selection process [

11].

2.5. Data Extraction

For data extraction, a Word table was developed following the data extraction model provided by JBI [

11], containing key information from the sources, such as author, year and country, objective, studies design, data collection instrument, theory, population and context (e.g., primary level, hospital), main results (quantitative and qualitative), limitations, and conclusion.

2.6. Summarizing and Reporting the Results

The content analysis technique by Bardin was used for the analysis and interpretation of the results. The results are presented both descriptively and through graphs and tables. The quality of the studies was evaluated using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. This tool was used to assess the reliability and relevance of the studies designs in the selected studies. After careful examination of each study, they were evaluated based on five specific criteria for mixed methods research, in addition to two initial questions that apply to both qualitative and quantitative studies within the MMAT tool [

12].

After reading in full, the mixed methods studies were evaluated using the MMAT tool, which has two general criteria, namely: Are there clear research questions? Does the data collected allow the research questions to be answered? Five specific criteria: 1) Is there an adequate justification for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? 2) Are the different components of the studies effectively integrated to answer the research question? 3) Are the results of the integration of the qualitative and quantitative components interpreted appropriately? 4) Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? 5) Do the different components of the studies meet the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved?

The information was then categorized into three groups: breastfeeding rates and duration, barriers to breastfeeding, and facilitators of breastfeeding.

3. Results

The search yielded 3,569 studies. After excluding 450 duplicates and reviewing titles and abstracts, 3,045 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were removed. After reading the 74 studies in full, 36 studies met all the inclusion criteria, as shown in the flowchart following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (

Figure 1 – Supl 2).

Mixed methods studies were conducted across 19 countries. The majority of the studies were conducted in the United States (n = 7; 19.4%). Most of the studies were published in 2020 (n = 8; 22.2%). (

Table 1).

Mixed methods approaches were described as explanatory sequential (n=18; 50%), convergent approach (n=14; 38.9%), and exploratory sequential (n=4; 11.1%).

Studies sought to elucidate institutional challenges to breastfeeding for health professionals [

13,

14] by using a sequential explanatory approach; and investigated mothers' experiences, measuring health professionals' knowledge, and attitudes and current practices regarding breastfeeding counseling [

15,

16]. Also, a study examined the associations between personal and environmental factors and exclusive breastfeeding [

17].

One study described the process of planning and evaluating a training program for women on breastfeeding applied a sequential explanatory approach [

5].

Pregnant and postpartum women were included in most of the studies (n=31, 86.1%), while health professionals were included in five studies (n=5, 13.9%).

All studies present the following data: 36.1% were from the community (n=13), 22.2% from the hospital (n=8), 16.7% from the Basic Health Unit (n=6), 13.9% from maternity (n=5), and 11.1% from the outpatient clinic (n=4).

The QUAN and QUAL methods used were adequately reported individually in the included studies. The QUAL component of the studies used questionnaires or semi-structured interviews (n=21, 58.3%), focus groups (n=8, 22.2%), in-depth interviews (n=5, 13.9%), observation method (n=1, 2.8%) and application of field diary (n=1, 2.8%). In the QUAN approach, 100% of the studies used questionnaires.

Most studies provided an adequate and complete description of the procedures followed in the sampling, data collection, and analysis stages of both components. On the other hand, the use of theories was present in the minority of the studies. The Theory of Planned Behavior (n=2, 5.6%) [

17,

18], Grounded Theory (n=1, 2.8%) [

19], Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Theory (n=1, 2.8%) [

14,

20] and Davis's Barrier Analysis Theory (n=1, 2.8%) [

21] were applied.

After reading and analyzing the 36 studies, it was found that only two studies [

22,

23] met all the criteria of the Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT).

Most studies included in this review was the lack of clarity regarding the theory used to support the analysis of the findings [

2,

3,

5,

13,

15,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

However, all studies included in the review were analyzed categorically. And, from the categorical analysis, common themes emerged that answered the research question: “How are studies on the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding being developed using mixed methods?”, organized into three categories: breastfeeding rates and duration, barriers, and facilitators presented below:

3.1. Breastfeeding Rates and Duration

After evaluating breastfeeding rates in the selected studies, it is observed that the rates continue to be lower than global recommendations.

Breastfeeding in the first hour after birth was 49.4% in Mexico [

40], 45% in Nigeria [

25], and 39.7% in Indonesia [

21].

Breastfeeding rates dropped within hours of birth, as observed in Nigeria, starting at 45% of mothers breastfeeding within the first hour of birth and decreasing to 29% within the first two hours [

25]. In another study conducted in Nigeria, breastfeeding remained above 50% up to one hour after birth [

4]. In Thailand, the cumulative proportions of mother-child pairs who initiated breastfeeding within two, three, and four hours after birth were 92.2%, 92.4%, and 94.7%, respectively [

24].

Regarding exclusive breastfeeding rates at hospital discharge, in a single hospital between Thailand and Myanmar, 99.3% of full-term newborns and 98.8% of preterm newborns were discharged exclusively breastfeeding [

24]. In Sweden, 82% of babies were exclusively breastfed at discharge [

41] and in the studies by [

35], this rate was higher than 90%.

The average length of exclusive breastfeeding observed in the United States was 5.8 months [

39]. In Mexico, 44.8% of children were exclusively breastfed in the first month of life [

40]. In South Africa, 34% of children were exclusively breastfed between four and eight weeks after birth [

22]. On the other hand, in Tanzania, 76% of 316 postpartum women exclusively breastfed their children up to one month after birth [

27]. Initially, 87.2% of Chinese and 75.6% of Irish mothers who gave birth in Ireland, breastfed their children. The rates decreased to 49.1% at 3 months and 28.4% at 6 months for Chinese mothers, while the rate among Irish mothers at 6 months remained above 60% [

42].

Several countries have assessed the duration of exclusive breastfeeding at six months, and even after recommendations from the WHO, UNICEF, and the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative to keep these rates above 50%. Research has found exclusive breastfeeding rates at 6 months of 19% in Nigeria [

25], 20% in Haiti [

26], 27% in Sweden [

41], 37.4% in Thailand [

17], and 35.3% in the USA [

28].

In China, women who worked in business and had formal employment contracts had the highest rates of early initiation, 75.67%, decreasing to 12.65% by 6 months [

30]. The proportion decreased significantly from 76% to 24.1% over six months, according to a different study [

27].

Over time, the rates of exclusive breastfeeding in the US decreased, with 33.4% of infants being exclusively breastfed for up to three months and only 16.9% up to one year of age [

28].

Breastfeeding rates at 12 months were 17% for Chinese women and 7.6% for Irish women [

42]. In contrast, studies showed a rate of 21% for Swedish women and 59% for American women [

41,

43].

Regarding breastfeeding intention, a study conducted in Thailand found that all first-time pregnant women expressed the intention or experience of breastfeeding when questioned in a focus group [

24]. Breastfeeding intention rates were mentioned by 99% of mothers in the studies conducted in the Southern and Central regions of Denmark [

29] and 67% of women reported an intention to breastfeed for more than 5 months. A study conducted in the United States [

37] indicates that 85.4% of women stated they intended to breastfeed.

When investigating the association between the breastfeeding practices of working mothers and their professional status and occupational areas related to agriculture, industry, and business, the intention to breastfeed was found in more than 90% [

30]. Also, 94% of women had a high level of knowledge about breastfeeding, and 73% of mothers intended to breastfeed their babies for up to one year [

25].

3.2. Barriers to Breastfeeding

The barriers to breastfeeding reported by mothers refer to biological; emotional; cultural; unfavorable social and hospital environments; difficulties in clinical management; lack of support from family, friends, health professionals, and employers; and skepticism about the benefits of breastfeeding.

Scientific evidence has supported mothers' reports of biological/physical barriers that influence breastfeeding, such as difficulty in latching on, sore/bruised and/or cracked nipples, change in the physical appearance of the breast associated with breastfeeding, insufficient milk production, mastitis, breast engorgement and nipple bleeding, which contributed to the woman's decision to stop breastfeeding [

13,

19,

29,

33,

36]. In Sweden, the findings on barriers to breastfeeding were represented by low milk production, and insufficient breast milk to satisfy the baby when breastfeeding and/or gaining weight [

41].

Although most mothers intend to breastfeed, many fear that they will not have enough milk for their baby and therefore prefer to supplement with formula, because they believe that donated milk may not be suitable for the baby and is not guaranteed to be safe and free from diseases, in addition to the belief that infant formula is recommended [

21,

40].

The child's crying frequent, breastfeeding, and short sleep periods were interpreted by mothers as signs of insufficient breast milk and drove the mothers' decision to mixed-feed their babies [22;27;40].

A mixed, explanatory sequential study, examining hospital practices, found that infants received infant formula during their hospital stay and that this was due to similar aspects, such as perception of insufficient milk, infant preferences, or cracked nipples. Other reasons included maternal need for rest and problems with breastfeeding technique [

40]. Other barriers included twins, the baby's refusal to breastfeed, being diabetic, smoking, or fear of breastfeeding because they were taking some medication [

39].

Mothers without support from family members and partners found it more difficult to breastfeed successfully [

19]. The mother's stress, the home environment, and the relationship with the child's father are barriers and affect women's mental health. According to them, these issues impair their ability to produce enough, good-quality breast milk for their babies [

22].

In the United Arab Emirates, women report difficulty in maintaining breastfeeding mainly due to employment, maternal exhaustion, and lack of family support [

44].

The family environment and breastfeeding support significantly influence mothers' decisions to start breastfeeding. Women considered the possibility of breastfeeding but felt discouraged by friends' or family's negative experiences with breastfeeding. African American and white adolescents reported that the lack of breastfeeding and negative experiences among their relatives and friends were barriers to the decision to breastfeed [

18].

In Nigeria, barriers to breastfeeding related to support from health professionals were the inability of midwives to perform safe traditional practices with mothers, ineffective rooming-in practices, staff shortages, lack of privacy in the ward, and inadequate visiting hours policy. Furthermore, it was observed that pregnant women who were denied safe traditional birth practices, such as singing, praying, or reading religious books during labor, were five times more likely to not breastfeed their newborns in the first hour after birth compared to pregnant women who were allowed these practices [

4].

Furthermore, despite contact with health and social service professionals during the first weeks postpartum, in most cases, adolescents did not receive support that would facilitate continued breastfeeding [

18]. Corroborating this finding, less than half of health professionals reported asking parents how long they planned to breastfeed exclusively and how long they planned to continue breastfeeding after the introduction of complementary foods at the first or second visit. Although almost all providers reported asking parents about breastfeeding problems or concerns at the first or second visit, only half (53.6%) reported that they continued to ask about problems or concerns at the 2-month visit, and one-third (34.3%) reported that they continued to ask about problems or concerns at the 4-month visit [

15].

In Ireland, breastfeeding had to be stopped because difficulties were not addressed in a timely and appropriate manner. Women reported that they did not receive adequate support or advice from healthcare providers [

42]. A lack of culturally appropriate breastfeeding promotion and a lack of breastfeeding education and encouragement from healthcare providers have been associated with breastfeeding failure [

14,

23,

34].

Furthermore, the mother's own will and external obstacles were additional reasons for stopping breastfeeding. An example of this reality is women with babies in the neonatal intensive care unit who have limited opportunities to be close to their babies [

21].

Skepticism about the benefits of breastfeeding, and the belief that children or other formula-fed individuals were healthy and intelligent, supported the idea that formula and breast milk are equivalent, which contributed to early weaning [

19]. Concerns about the quality of human milk when a woman’s diet is unhealthy cause mothers to lose confidence in breast milk, and fears of harming the child may lead women to introduce formula milk and/or complementary foods at an early age [

26].

Some mothers considered breastfeeding but were dissuaded by grandmothers’ arguments against breast milk being sufficient, especially in the first six months of birth. In a study in South-Western Nigeria, three of the grandmothers argued that introducing semi-solids or water alongside breast milk would allow the child to grow more quickly and enable their mothers to resume economic activities without a prolonged break [

25].

The use of infant formula in Ireland was prevalent among participants, resulting in cessation or shorter duration of breastfeeding, this evidence is justified because in this country, infant formula was widely considered to be of good quality, safe, and reasonably priced, compared to that produced in China [

42].

Some Swedish mothers also explained that when they started giving infant formula or solid foods, their breast milk dried up and it was difficult to continue breastfeeding [

41].

The lack of space for breastfeeding in the workplace is a problem that hinders breastfeeding. Other barriers include the difficulty in balancing work and breastfeeding, the lack of funding to create a breastfeeding-friendly work environment, inadequate and periodic breaks to breastfeed or express milk, and the lack of adequate support for working mothers [

3,

13,

14,

19,

23,

39,

41]. These barriers force mothers to adopt mixed-method feeding practices to fulfill their professional and social responsibilities [

30,

44].

Social environments unfavorable to breastfeeding are another barrier. In the USA, most mothers reported that they did not want to breastfeed, and the most frequent reasons were: returning to school, and feeling embarrassed about breastfeeding in public places [

18].

3.3. Facilitators of Breastfeeding

The success of breastfeeding depends on numerous factors, including breastfeeding education and counseling that may occur during prenatal, childbirth, and postpartum care. Success is also influenced by the woman's intention to breastfeed, and support from her employer, family, and spouse.

Early breastfeeding education for newborns, during consultations in antenatal clinics and during the postpartum period, has been shown to facilitate breastfeeding problems, since the knowledge acquired by women during prenatal care influences their behavior after childbirth and can improve newborn survival [

4].

Nurses play an important role in providing health education on breastfeeding during antenatal and postnatal visits at the health facility. The provision of targeted services by trained health professionals who provide breastfeeding support during antenatal and postnatal care has been associated with increases in breastfeeding rates, particularly in exclusive breastfeeding rates [

25]. Another practice that encourages breastfeeding is the support offered by women in the community who have already breastfed, a service known as peer support [

20]. Furthermore, women found prenatal consultations and postnatal contacts rewarding, enjoyable, encouraging, and valuable [

21].

Counseling is a practice that encourages breastfeeding. In the United Kingdom, mothers who received counseling on exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) during prenatal care were 73% more likely to have EBF compared to those who did not. Similarly, mothers who received EBF counseling after childbirth were twice as likely to practice EBF compared to those who did not receive guidance on the subject. The study also showed that women who were knowledgeable about the duration and benefits of breastfeeding had a higher prevalence of EBF compared to others [

27].

Counseling for women in same-sex relationships remains quite limited. All pregnant women need to receive support during the prenatal period, childbirth, and throughout their breastfeeding journey. Research in the United States shows that these mothers often seek information from external sources, such as empirical reports, books, online groups, and websites [

43]. In Africa, 80% of women who breastfed within 1 hour of their child's birth received assistance from a health professional, while 47% of women who did not breastfeed within that first hour did not receive assistance from a health professional [

36]. Other factors that interfere with breastfeeding are the knowledge of health professionals, the support of institutions and the implementation of policies such as the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) [

21].

The slow adoption of the BFHI policy by hospitals in Abu Dhabi is related to factors external to the health system and, as a result, most mothers adopt mixed feeding strategies for their children [

44]. Many American mothers obtained information about breastfeeding in the hospital after giving birth, as well as received practical assistance to show them how to hold the baby to feed him/her. Participants who placed importance on the benefits of breastfeeding for their infants’ health and development generally continued to breastfeed longer [

18,

24].

Women’s intention to breastfeed and high self-efficacy were strong predictors of positive breastfeeding outcomes [

24,

29,

41]. Furthermore, the acquisition of knowledge and practical skills by mothers, fathers/partners, and family members during pregnancy and postpartum visits is considered a cornerstone of successful breastfeeding [

5]. Prenatal education and counseling for adolescents may be more effective if they include family members and peer support for adolescents.

A home visit or outpatient appointment for adolescents in the initial days following hospital discharge, along with practical support, could enhance their ability to breastfeed. Additionally, it is essential to expand support for the transition back to school and to create more breastfeeding-friendly environments in schools. These measures have the potential to help adolescents who wish to breastfeed continue successfully [

18].

Scheduled home visits during the exclusive breastfeeding period or up to 6 months postpartum increase the self-confidence and satisfaction of breastfeeding mothers [

33,

36].

In addition to support from health professionals, support from family, spouse, and employer are essential links to successful breastfeeding. Social, instrumental, and emotional support, access to reliable information, and resources for community-based breastfeeding promotion programs. On the other hand, myths among low-income African American mothers and their families need to be dispelled [

23,

39].

Support from peers, spouses, and family members helped women feel more confident about breastfeeding and contributed to reducing stress, and strain at work, and breastfeeding [

14,

20]. A study conducted with women in Hong Kong found that breastfeeding support from family and friends was positively associated with the success of exclusive breastfeeding for up to six months, even during the COVID-19 pandemic [

2].

Other factors that facilitate mothers' breastfeeding practices after returning to work include employment benefits such as paid maternity leave, shorter commute time, a breastfeeding-friendly workplace, and flexible working hours [

14,

30]. Furthermore, having a daycare center in the workplace and positive attitudes and personal experiences of breastfeeding among colleagues and managers are factors that encourage breastfeeding [

13].

3.4. Limitations of the Studies Included in the Review

Regarding the limitations associated with the studies evaluated in this review, about 5 studies (13.9%) discussed the findings about the sampling N. Although they adopted a mixed-method design to strengthen the conclusions, quantitative and qualitative sample sizes were relatively small, which limits the generalizability of the data [

5,

23,

25,

26].

Overall, 5 studies (13.9%) addressed concerns related to recall bias in the conduct of the research [

2,

3,

27,

34,

42]. And only two studies (5.6%) mentioned the limitations of the low response rate, and few responses to allow statistical analysis [

20,

28].

In mixed methods research, a basic premise is the need for clear integration between quantitative and qualitative data. This integration can be achieved through a joint-display matrix [

12], which facilitates the clear visual presentation of the findings, allowing us to identify how they connect, compare, and complement each other.

Among the articles analyzed, only two adopted this strategy. Witten et al. [

22] used a matrix to present factors that influence exclusive breastfeeding in a cohort of mothers with babies aged 6 to 24 weeks, organizing the data by themes and codes, highlighting the most frequent barriers and facilitators. Felder et al. [

23] investigated 50 pregnant African-American women during an obstetric-gynecological consultation (Phase I) and, through a three-phase integration, presented the six qualitative themes (Phase II) and the integrated data (Phase III), revealing relevant cultural considerations for future research. This approach is evidenced as a best practice in mixed methods research, as it offers greater clarity in the relationship between qualitative and quantitative data, while enabling a richer and more visually accessible analysis. On the other hand, the other articles analyzed did not adopt the joint display matrix, presenting the data separately. Such a choice can make it difficult to immediately identify the relationships between the two data sets, compromising, to some extent, clarity and integration, which are fundamental pillars in mixed methods research.

4. Discussion

There are two main reasons for using mixed methods in research. The first is complementarity of using both quantitative and qualitative data to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon being studied. The second reason is sequentially, where one research approach lays the foundation for the questions of the other, helping to fill in the gaps regarding the phenomenon of interest [

9,

45].

Integration in mixed methods research is classified into four categories: 1) data fusion, when qualitative and quantitative data are analyzed separately, then the results from both arms are compared for differences and similarities in a convergent design; 2) data explication, when qualitative findings help to explain quantitative findings in an explanatory sequential design; 3) data construction, when qualitative results inform future quantitative research questions and enable the development of an exploratory sequential design; and 4) data incorporation, when qualitative findings can be incorporated and help explain quantitative findings in an intervention design [

9,

46].

In this review, most studies used the explanatory sequential approach, deepening the findings about breastfeeding rates and duration, barriers, and facilitators of breastfeeding. Although the academic community and policymakers are calling for a broader application of mixed methods research, suggesting the combined use of quantitative and qualitative methods, its application has been present in studies conducted in some countries, notably the United States [

18,

19,

23,

28,

38,

39,

43].

On the other hand, this type of research method remained stable throughout 2011 and 2019, with an upward curve in 2020 and 2022, indicating that mixed methods research is gaining strength, acquiring more prominence and value, probably due to a reflection of a change in research culture, moving from a single-method tradition to a multiple-method tradition.

In this scoping review, 50% of the studies analyzed used the explanatory sequential approach as a research design. It is pointed out that the most common design used in mixed study is convergent, in which QUAN and QUAL data collections are complementary and can be conducted separately or concomitantly [

47].

One of the limitations of the studies included in this review was the lack of clarity regarding the theory used to support the analysis of the findings. For Creswell and Creswell [

9] a mixed methods design within a theoretical lens presents an abstract and formalized set of assumptions to guide the approach and conduct the research. Two studies examined their data using the Theory of Planned Behavior [

17,

18]. According to Neifert [

48], the capabilities of this theory have been utilized to design behavior change interventions aimed at understanding the factors that influence the intention to exclusively breastfeed. These interventions focus on fostering positive behavioral beliefs, correcting misconceptions in this area, and empowering women.

The results highlighted that the prevalence of breastfeeding varied across countries, but in general, breastfeeding rates were lower in American, Mexican, Nigerian and Irish women [

18,

25,

28,

39,

40,

42] than in women from Thailand, South Africa, China and Sweden [

24,

30,

35,

36,

41,

42].

While the rates exceed the recommendations set by WHO and UNICEF, the data in this scoping review cannot accurately determine the prevalence of breastfeeding among women. This limitation arises from the varied outcome measures used across the studies and the methodological weaknesses present in the included research.

Individual and social barriers to breastfeeding, including lack of knowledge, embarrassment, generalized exposure to infant formula, inadequate maternity care practices, lactation difficulties, concerns about insufficient milk production, employment, insufficient family and social support, and inadequate knowledge and support from professionals were reported by women. Conversely, some studies addressed the importance of support from health professionals to help mothers increase the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding [

2,

18,

19,

21,

22,

23,

25,

26,

27,

29,

39,

40]. Family-centered breastfeeding models, peer support groups, and technologies have been studied as possible strategies to help women achieve their breastfeeding goals [

18,

20,

21,

25,

28,

49].

About breastfeeding facilitators, the literature indicates that continuous rooming-in, allowing mother and baby to stay together 24 hours a day, creates a climate that potentially supports the mother in learning to recognize and respond to the baby's hunger signals, and instills confidence in her ability to care for the baby [

4,

40,

50].

The limitation of this review is to recognize that the scope of mixed methods research may be much broader than what was captured since we cannot exclude the possibility that we missed some mixed methods publications that might not have been clearly identified as mixed methods. Furthermore, systematic review studies were excluded, and only primary studies were included.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review included mixed-methods research with an explanatory sequential, convergent, and exploratory sequential approach. The included studies addressed breastfeeding rates and duration, and barriers and facilitators of breastfeeding in different contexts and cultures worldwide.

The breastfeeding rates reported continue to be lower than the global recommendations. The barriers to breastfeeding reported by mothers refer to biological; emotional; cultural; unfavorable social and hospital environments; difficulties in clinical management; lack of support from family, friends, health professionals, and employers; and skepticism about the benefits of breastfeeding. On the other hand, the main facilitators of breastfeeding reported were education and counseling during prenatal, childbirth, and postpartum periods; the woman's intention to breastfeed, and support from family, employer, spouse, and health professionals.

Most studies employed an explanatory sequential mixed-methods approach to effectively research the multifaceted nature of breastfeeding and evaluate interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M., E.L., K.F, N.P., A.C., M.B., C.P.; Methodology, G.M., E.L., K.F, N.P., A.C., M.B., C.P.; Software, G.M., E.L, N.P., Formal Analysis, G.M., E.L., C.P.; Investigation, G.M., E.L., N.P., C.P.; Resources, G.M., N.P., Data Curation, G.M., N.P., Writing – Original Draft Preparation, G.M., E.N., A.C., M.B., C.P; Writing – Review & Editing, E.N., A.C., M.B., C.P; Visualization, G.M., E.L., K.F, N.P., A.C., M.B., C.P.; Supervision, E.L., C.P.; Project Administration, E.L., C.P.; Funding Acquisition, G.M., E.L., C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of CNPq - Financing Code 001 and the Espírito Santo Research and Innovation Support Foundation (FAPES).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kajamaa, A., Mattick, K., & de la Croix, A. How to do mixed-methods research. The clinical teacher. 2020;17(3), 267–271. [CrossRef]

- Kwan J, Jia J, Yip KM, So HK, Leung SS, Ip P, Wong WH. A mixed-methods studies on the association of six-month predominant breastfeeding with socioecological factors and COVID-19 among experienced breastfeeding women in Hong Kong. Int Breastfeed J. 21 maio 2022;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Kubuga CK, Tindana J. Breastfeeding environment and experiences at the workplace among health workers in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Int Breastfeed J. 14 jun 2023;18(1). [CrossRef]

- Shobo OG, Umar N, Gana A, Longtoe P, Idogho O, Anyanti J. Factors influencing the early initiation of breast feeding in public primary healthcare facilities in Northeast Nigeria: a mixed-method studies. BMJ Open. Abr 2020;10(4):e032835. [CrossRef]

- Kohan S, Keshvari M, Mohammadi F, Heidari Z. Designing and evaluating an empowering program for breastfeeding: a mixed-methods studies. Arch Iran Med. July 2019;22(8):443–52.

- Primo CC, Brandão MAG. Interactive Theory of Breastfeeding: creation and application of a middle-range theory. Reben - revista brasileira de enfermagem. 2017;70: 1191-1198. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco van der Sand IC, Silveira AD, Cabral FB, Das Chagas CD. A influência da autoeficácia sobre os desfechos do aleitamento materno: Estudo de revisão integrativa. Rev Contexto Amp Saude. 17 maio 2022;22(45):e11677. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso V, Trevisan I, Cicolella DD, Waterkemper R. Systematic review of mixed methods: method of research for the incorporation of evidence in nursing. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2019;28. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Projeto de pesquisa: métodos qualitativo, quantitativo e misto. 5. ed. Porto Alegre: Penso, 2021.

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. (2024). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Noth Adelaide, Australia: JBI. Available from: https://jbi-global- wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL.

- Peters, M.D.J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A.C., Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Adelaide/Austrália, JBI. Available from: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL.

- Oliveira JLC de, Magalhães AMM de, Matsuda LM, Santos JLG dos, Souto RQ, Riboldi C de O, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool: strengthening the methodological rigor of mixed methods research studies in nursing. Texto contexto – enferm. 2021;30:e20200603. [CrossRef]

- Jiravisitkul P, Thonginnetra S, Kasemlawan N, Suntharayuth T. Supporting factors and structural barriers in the continuity of breastfeeding in the hospital workplace. Int Breastfeed J. 19 dez 2022;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Nkrumah J, Abuosi AA, Nkrumah RB. Towards a comprehensive breastfeeding-friendly workplace environment: insight from selected healthcare facilities in the central region of Ghana. BMC Public Health. 9 set 2021;21(1). [CrossRef]

- Ramos MM, Sebastian RA, Sebesta E, McConnell AE, McKinney CR. Missed Opportunities in the Outpatient Pediatric Setting to Support Breastfeeding: Results From a Mixed-Methods Studies. J Pediatr Health Care. Jan 2019;33(1):64-71. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J. The Attitude of UAE Mothers towards Breastfeeding in Abu Dhabi. Texila Int J Public Health. 30 mar 2020;8(1):248-55. [CrossRef]

- Nuampa S, Ratinthorn A, Patil CL, Kuesakul K, Prasong S, Sudphet M. Impact of personal and environmental factors affecting exclusive breastfeeding practices in the first six months during the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand: a mixed-methods approach. Int Breastfeed J. 17 out 2022;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Tucker CM, Wilson EK, Samandari G. Infant feeding experiences among teen mothers in North Carolina: Findings from a mixed-methods studies. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2011;6(1):14. [CrossRef]

- Kadakia A, Joyner B, Tender J, Oden R, Moon RY. Breastfeeding in African Americans May Not Depend on Sleep Arrangement. Clinical Pediatrics. 2014 Aug 19;54(1):47–53. [CrossRef]

- Ingram J. A mixed methods evaluation of peer support in Bristol, UK: mothers’, midwives’ and peer supporters’ views and the effects on breastfeeding. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2013 Oct 20;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Murray L, Anggrahini SM, Woda RR, Ayton JE, Beggs S. Exclusive Breastfeeding and the Acceptability of Donor Breast Milk for Sick, Hospitalized Infants in Kupang, Nusa Tenggara Timur, Indonesia. J Hum Lact. 20 maio 2016; 32(3):438-45. [CrossRef]

- Witten C, Claasen N, Kruger HS, Coutsoudis A, Grobler H. Psychosocial barriers and enablers of exclusive breastfeeding: lived experiences of mothers in low-income townships, North West Province, South Africa. Int Breastfeed J. 26 ago 2020;15(1). [CrossRef]

- Felder TM, Cayir E, Nkwonta CA, Tucker CM, Harris EH, Jackson JR. A Mixed-Method Feasibility Studies of Breastfeeding Attitudes among Southern African Americans. West J Nurs Res. 23 set 2021:019394592110454. [CrossRef]

- White AL, Carrara VI, Paw MK, Malika, Dahbu C, Gross MM, et al. High initiation and long duration of breastfeeding despite absence of early skin-to-skin contact in Karen refugees on the Thai-Myanmar border: a mixed methods studies. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2012 Dec;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Agunbiade OM, Ogunleye OV. Constraints to exclusive breastfeeding practice among breastfeeding mothers in Southwest Nigeria: implications for scaling up. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2012 Apr;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Dörnemann J, Kelly AH. “It is me who eats, to nourish him”: a mixed-method studies of breastfeeding in post-earthquake Haiti. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2012 Jul 12;9(1):74–89.

- Maonga AR, Mahande MJ, Damian DJ, Msuya SE. Factors Affecting Exclusive Breastfeeding among Women in Muheza District Tanga Northeastern Tanzania: A Mixed Method Community Based Studies. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015 Aug 4;20(1):77–87. [CrossRef]

- Kamoun C, Spatz D. Influence of Islamic Traditions on Breastfeeding Beliefs and Practices Among African American Muslims in West Philadelphia: A Mixed-Methods Studies. J Hum Lact. 13 jun 2017; 34(1):164-75. [CrossRef]

- Feenstra MM, Jørgine Kirkeby M, Thygesen M, Danbjørg DB, Kronborg H. Early breastfeeding problems: A mixed method studies of mothers’ experiences. Sex Amp Reprod Healthc. Jun 2018;16:167-74. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Xin T, Gaoshan J, Li Q, Zou K, Tan S, Cheng Y, Liu Y, Chen J, Wang H, Mu Y, Jiang L, Tang K. The association between work related factors and breastfeeding practices among Chinese working mothers: a mixed-method approach. Int Breastfeed J. 27 jun 2019;14(1). [CrossRef]

- Hall H, McLelland G, Gilmour C, Cant R. ‘It's those first few weeks’: Women's views about breastfeeding support in an Australian outer metropolitan region. Women Birth. Dez 2014;27(4):259-65. [CrossRef]

- Hookway L, Brown A. Barriers to optimal breastfeeding of medically complex children in the UK paediatric setting: a mixed methods survey of healthcare professionals. J Hum Nutr Diet. 27 jul 2023;36:1857–1873. [CrossRef]

- Irmawati, Nugraheni SA, Sulistiyani, Sriatmi A. Finding The Needs of Breastfeeding Mother Accompaniment for Successful Exclusive Breastfeeding Until 6 Months in Semarang City: A Mixed Method. BIO Web Conf. 2022;54:00004. [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir RB, Flacking R, Jonsdottir H. Breastfeeding initiation, duration, and experiences of mothers of late preterm twins: a mixed-methods studies. Int Breastfeed J. 8 set 2022;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Saade S, Flacking R, Ericson J. Parental experiences and breastfeeding outcomes of early support to new parents from family health care centres—a mixed method studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 23 fev 2022;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Van Breevoort D, Tognon F, Beguin A, Ngegbai AS, Putoto G, van den Broek A. Determinants of breastfeeding practice in Pujehun district, southern Sierra Leone: a mixed-method studies. Int Breastfeed J. 26 maio 2021;16(1). [CrossRef]

- Gordon LK, Mason KA, Mepham E, Sharkey KM. A mixed methods studies of perinatal sleep and breastfeeding outcomes in women at risk for postpartum depression. Sleep Health. Jun 2021;7(3):353-61. [CrossRef]

- Papautsky EL, Koenig MD. A mixed-methods examination of inpatient breastfeeding education using a human factors perspective. Breastfeed Med. 1 dez 2021;16(12):947-55. [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Fiese BH, Donovan SM. Breastfeeding is natural but not the cultural norm: A mixed-methods studies of first-time breastfeeding, african american mothers participating in WIC. J Nutr Educ Behav. Jul 2017;49(7):S151—S161.e1. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cordero S, Lozada-Tequeanes AL, Fernández-Gaxiola AC, Shamah-Levy T, Sachse M, Veliz P, Cosío-Barroso I. Barriers and facilitators to breastfeeding during the immediate and one month postpartum periods, among Mexican women: a mixed methods approach. Int Breastfeed J. 15 out 2020;15(1). [CrossRef]

- Ericson J, Palmér L. Cessation of breastfeeding in mothers of preterm infants—A mixed method studies. Plos One. 15 maio 2020;15(5): e0233181. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Q, Younger KM, Cassidy TM, Wang W, Kearney JM. Breastfeeding practices 2008–2009 among Chinese mothers living in Ireland: a mixed methods studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 23 jan 2020;20(1). [CrossRef]

- Juntereal NA, Spatz DL. Breastfeeding experiences of same-sex mothers. Birth. 18 nov 2019;47(1):21-8. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J. The Effect of Knowledge on Breastfeeding among Mothers’ in Abu Dhabi. Texila Int J Public Health. 30 mar 2020;8(1):339-45. [CrossRef]

- Barnow BS, Pandey SK, Luo QE. Como a pesquisa de métodos mistos pode melhorar a relevância política das avaliações de impacto. Eval Rev. 2024 Jun; 48(3):495-514. [CrossRef]

- Dolan S, Nowell L, Moules NJ. Interpretive description in applied mixed methods research: Exploring issues of fit, purpose, process, context, and design. Nursing Inquiry. 2022 Dec 4.

- Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the Power of Stories and the Power of Numbers: Mixed Methods Research and Mixed Studies Reviews. Annu Rev Public Health [Internet]. 18 mar 2014 [citado 4 mar 2024];35(1):29-45. [CrossRef]

- Neifert M, Bunik M. Overcoming Clinical Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2013 Feb;60(1):115–45. [CrossRef]

- Mojgan J, Shirin O, Kazemi A. Development of an exclusive breastfeeding intervention based on the theory of planned behavior for mothers with preterm infants: Studies protocol for a mixed methods studies. Journal of education and health promotion. 2023 Jan 1;12(1):340–0. [CrossRef]

- Tomori, C. Overcoming Barriers to Breastfeeding. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2022 Feb;83. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).