Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

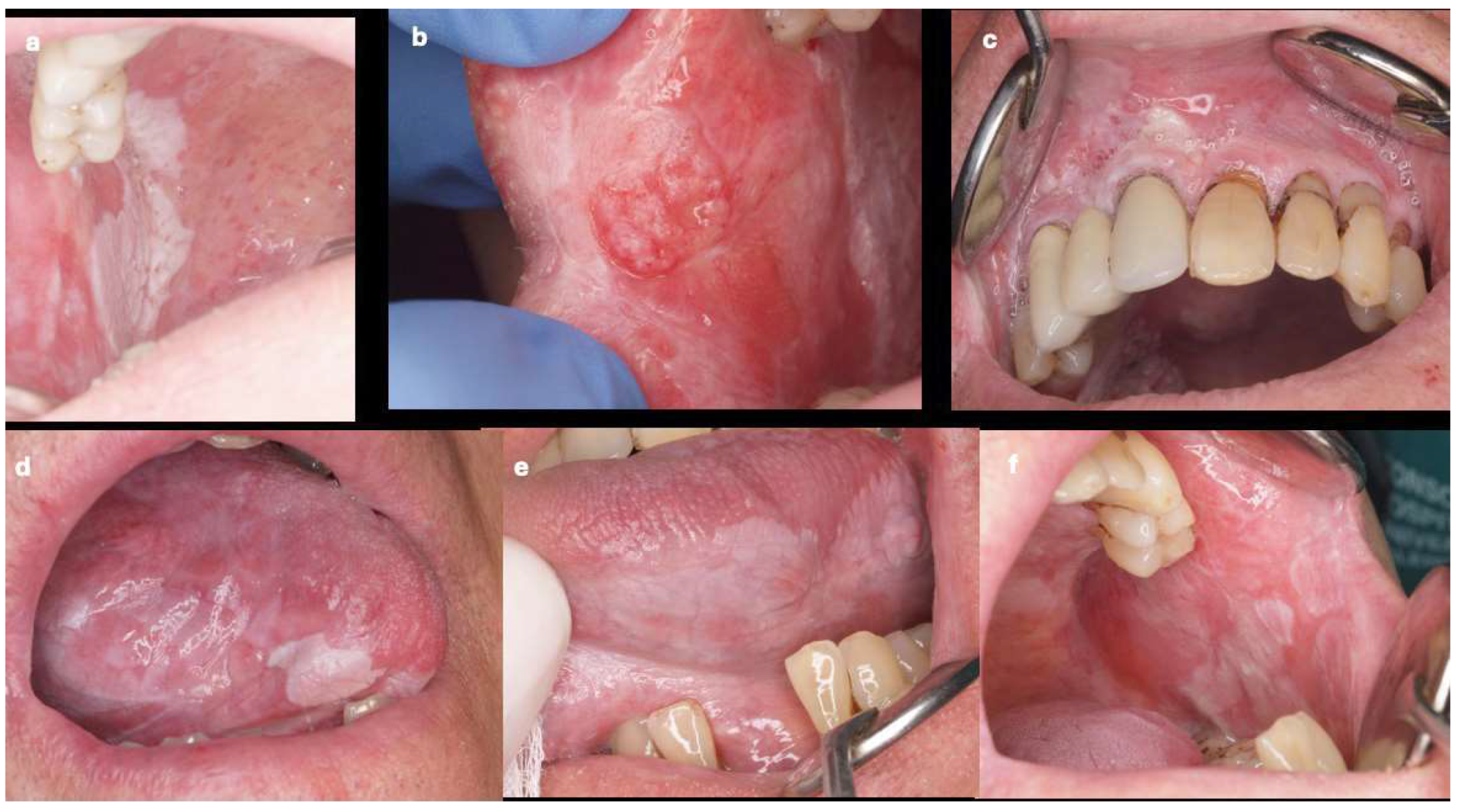

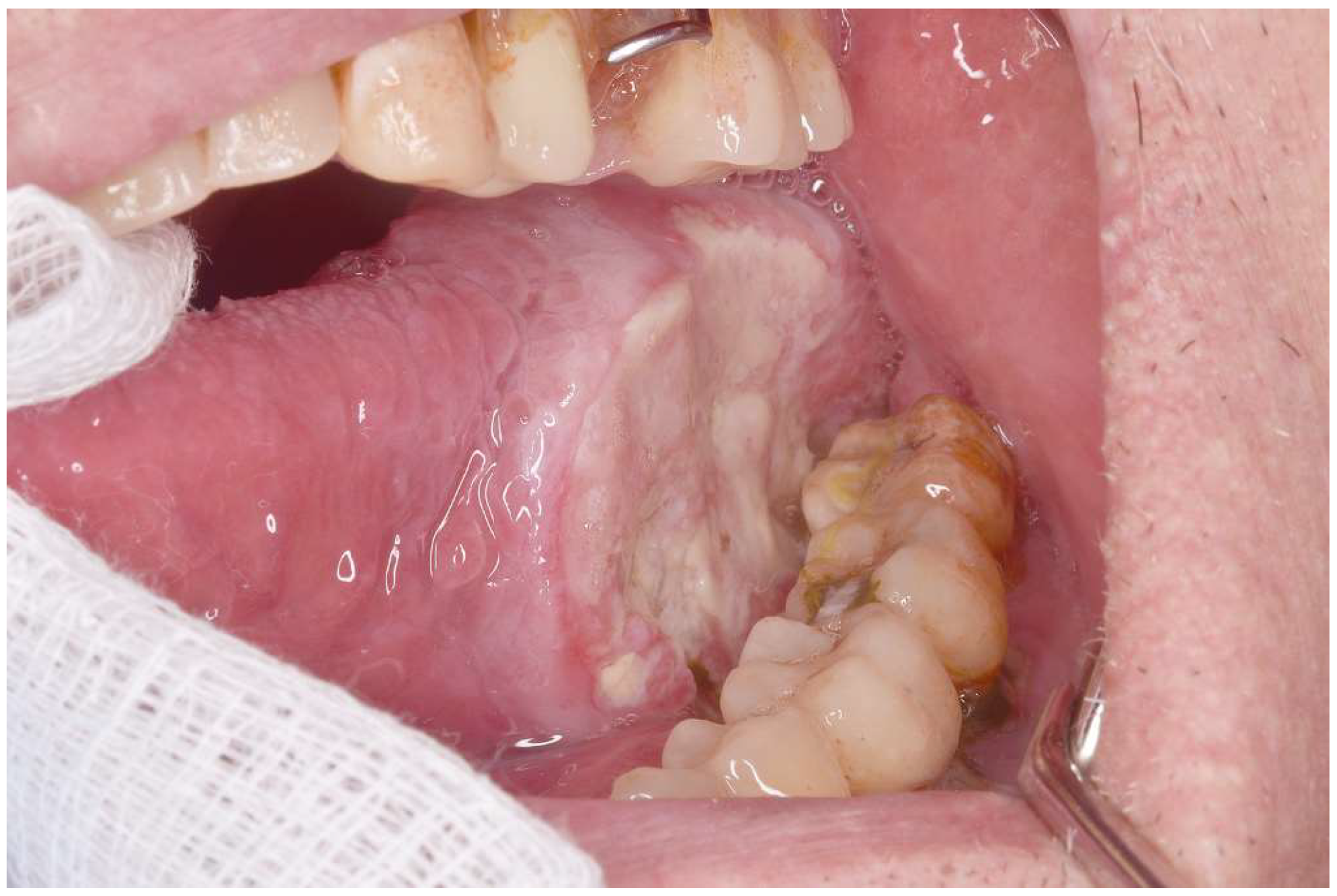

Background/Objectives: Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) is the oral disorder with the greatest degree of malignant transformation. However, it is relatively rare. This study compared the clinical characteristics of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) who had and had not been previously diagnosed with PVL. Methods: This case–control study compared the clinical characteristics of patients classified as early (T1 and T2) or advanced (T3 and T4) OSCC according to the TNM classification, including age, gender, location, and clinical type of cancer. The analysis involved 140 patients. Group 1: 50 OSCC patients with PVL (OSCC-PVL) and Group 2: 90 OSCC patients without PVL (OSCC-noPVL). Results: The patients with OSCC-PVL were younger than those with OSCC-noPVL, but this did not reach statistical significance. Regarding patient gender, those with OSCC-PVL were much more frequently female (70%), while OSCC-noPVL was more prevalent in men (65.5%) (p < 0.01). There were also significant differences in the oral locations between the two groups: the gingiva was most prevalent in OSCC-PVL and the tongue in OSCC-noPVL. Erythroleukoplastic forms were significantly more common in OSCC-PVL (30% vs. 7.7%), while ulcerated forms were more frequent in OSCC-noPVL (63.3% vs. 42%). Finally, early T stages were much more prevalent in our patients with OSCC-PVL. Conclusions: We found that OSCC preceded by PVL was much more frequent in women, had less aggressive clinical forms, and had significantly more frequent early T stages than in OSCC-noPVL.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hansen LS, Olson JA, Silverman S Jr. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. A long-term study of thirty patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985 Sep;60(3):285-98. PMID: 3862042. [CrossRef]

- Torrejon-Moya A, Jané-Salas E, López-López J. Clinical manifestations of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2020 May;49(5):404-408. Epub 2020 Feb 9. PMID: 31990082. [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya S, Kujan O, Aguirre-Urizar JM, Bagan JV, González-Moles MÁ, Kerr AR, Lodi G, Mello FW, Monteiro L, Ogden GR, Sloan P, Johnson NW. Oral potentially malignant disorders: A consensus report from an international seminar on nomenclature and classification, convened by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1862-1880. Epub 2020 Nov 26. PMID: 33128420. [CrossRef]

- Brignardello-Petersen R. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and erythroplakia are probably the disorders with the highest rate of malignant transformation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020 Aug;151(8):e62. Epub 2020 May 26. PMID: 32471555. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Ou L, Yang Y, Zhao D, Liu B, Liu R, Liu O, Feng H. A Bibliometric and Visualised Analysis of Proliferative Verrucous Leucoplakia From 2003 to 2023. Int Dent J. 2025 Feb;75(1):333-344. Epub 2024 Jul 22. PMID: 39043528. [CrossRef]

- Chainani-Wu N, Purnell DM, Silverman S Jr. A case report of conservative management of extensive proliferative verrucous leukoplakia using a carbon dioxide laser. Photomed Laser Surg. 2013 Apr;31(4):183-7. Epub 2013 Mar 8. PMID: 23473346. [CrossRef]

- Bombeccari GP, Garagiola U, Candotto V, Pallotti F, Carinci F, Giannì AB, Spadari F. Diode laser surgery in the treatment of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia associated with HPV-16 infection. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Jul 30;40(1):16. PMID: 30105220; PMCID: PMC6064714. [CrossRef]

- Yan Y, Li Z, Tian X, Zeng X, Chen Q, Wang J. Laser-assisted photodynamic therapy in proliferative verrucous oral leukoplakia. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2022 Sep;39:103002. Epub 2022 Jul 6. PMID: 35809828. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Shi Y, Dong Y, Liu T, Dan H, Wang J, Zeng X. Photodynamic therapy combined with laser drilling successfully prevents the recurrence of refractory oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2021 Dec;36:102564. Epub 2021 Oct 3. PMID: 34610431. [CrossRef]

- Cobb CM, Beaini NE, Scully J, Gibson TM. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: Case study of 24 years and outcome of treatment with CO2 laser. Clin Adv Periodontics. 2024 Oct 24. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39447057. [CrossRef]

- Vergier V, Porporatti AL, Babajko S, Taihi I. Gingival Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia and Cancer: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Oral Dis. 2024 Oct 9. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39385511. [CrossRef]

- Pedroso CM, do Santos ES, Alves FA, Martins MD, Kowalski LP, Lopes MA, Warnakulasuriya S, Villa A, Santos-Silva AR. Surgical protocols for oral leukoplakia and precancerous lesions across three different anatomic sites. Oral Dis. 2024 Aug 18. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39155483. [CrossRef]

- Proaño-Haro A, Bagan L, Bagan JV. Recurrences following treatment of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021 Sep;50(8):820-828. Epub 2021 Apr 13. PMID: 33765364. [CrossRef]

- Hanna GJ, Villa A, Nandi SP, Shi R, ONeill A, Liu M, Quinn CT, Treister NS, Sroussi HY, Vacharotayangul P, Goguen LA, Annino DJ Jr, Rettig EM, Jo VY, Wong KS, Lizotte P, Paweletz CP, Uppaluri R, Haddad RI, Cohen EEW, Alexandrov LB, William WN Jr, Lippman SM, Woo SB. Nivolumab for Patients With High-Risk Oral Leukoplakia: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2024 Jan 1;10(1):32-41. PMID: 37971722; PMCID: PMC10654930. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Lan Q, Wei P, Gao Y, Zhang J, Hua H. Clinical, histopathological characteristics and malignant transformation of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia with 36 patients: a retrospective longitudinal study. BMC Oral Health. 2024 May 30;24(1):639. PMID: 38816724; PMCID: PMC11138006. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-García P, González-Moles MÁ, Mello FW, Bagan JV, Warnakulasuriya S. Malignant transformation of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1896-1907. Epub 2021 May 19. PMID: 34009718. [CrossRef]

- Faustino ISP, de Pauli Paglioni M, de Almeida Mariz BAL, Normando AGC, Pérez-de-Oliveira ME, Georgaki M, Nikitakis NG, Vargas PA, Santos-Silva AR, Lopes MA. Prognostic outcomes of oral squamous cell carcinoma derived from proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review. Oral Dis. 2023 May;29(4):1416-1431. Epub 2022 Mar 2. PMID: 35199416. [CrossRef]

- González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, Ramos-García P. Prognosis Parameters of Oral Carcinomas Developed in Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Sep 28;13(19):4843. PMID: 34638327; PMCID: PMC8507842. [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Pomares A, Hervás D, Bagan-Debon L, Proaño A, Garcia D, Sandoval J, Bagan J. Oral cancers preceded by proliferative verrucous leukoplakia exhibit distinctive molecular features. Oral Dis. 2024 Apr;30(3):1072-1083. Epub 2023 Mar 21. PMID: 36892444. [CrossRef]

- Cerero-Lapiedra R, Baladé-Martínez D, Moreno-López LA, Esparza-Gómez G, Bagán JV. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a proposal for diagnostic criteria. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010 Nov 1;15(6):e839-45. PMID: 20173704.

- Nagesh M, Gowtham S, Bharadwaj B, Ali M, Goud AK, Siddiqua S. Evolution of TNM Classification for Clinical Staging of Oral Cancer: The Past, Present and the Future. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2023 Sep;22(3):710-719. Epub 2023 Apr 11. PMID: 37534341; PMCID: PMC10390384. [CrossRef]

- Erazo-Puentes MC, Sánchez-Torres A, Aguirre-Urizar JM, Bara-Casaus J, Gay-Escoda C. Has the 8th American joint committee on cancer TNM staging improved prognostic performance in oral cancer? A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2024 Mar 1;29(2):e163-e171. PMID: 38368527; PMCID: PMC10945871. [CrossRef]

- Sridharan S, Thompson LDR, Purgina B, Sturgis CD, Shah AA, Burkey B, Tuluc M, Cognetti D, Xu B, Higgins K, Hernandez-Prera JC, Guerrero D, Bundele MM, Kim S, Duvvuri U, Ferris RL, Gooding WE, Chiosea SI. Early squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue with histologically benign lymph nodes: A model predicting local control and vetting of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer pathologic T stage. Cancer. 2019 Sep 15;125(18):3198-3207. Epub 2019 Jun 7. PMID: 31174238; PMCID: PMC7723468. [CrossRef]

- Bürkner PC. brms An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan Journal of statistical software. 2017 Aug 29;80:1-28.

- Makowski D, Ben-Shachar MS, Chen SHA, Lüdecke D. Indices of Effect Existence and Significance in the Bayesian Framework. Front Psychol. 2019 Dec 10;10:2767. PMID: 31920819; PMCID: PMC6914840. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F (2024). Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/900-world-fact-sheet.pdf.

- Erazo-Puentes MC, Sánchez-Torres A, Aguirre-Urizar JM, Bara-Casaus J, Gay-Escoda C. Has the 8th American joint committee on cancer TNM staging improved prognostic performance in oral cancer? A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2024 Mar 1;29(2):e163-e171. PMID: 38368527; PMCID: PMC10945871. [CrossRef]

- Amezaga-Fernandez I, Aguirre-Urizar JM, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Chamorro-Petronacci C, Lafuente-Ibáñez de Mendoza I, Marichalar-Mendia X, Blanco-Carrión A, Antúnez-López J, García-García A. Epidemiological, clinical, and prognostic analysis of oral squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed and treated in a single hospital in Galicia (Spain): a retrospective study with 5-year follow-up. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2024 Jan 1;29(1):e36-e43. PMID: 37330964; PMCID: PMC10765332. [CrossRef]

- Mroueh R, Nevala A, Haapaniemi A, Pitkäniemi J, Salo T, Mäkitie AA. Risk of second primary cancer in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2020 Aug;42(8):1848-1858. Epub 2020 Feb 14. PMID: 32057158. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Jan-Feb;74(1):12-49. Epub 2024 Jan 17. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Mar-Apr;74(2):203. doi: 10.3322/caac.21830. PMID: 38230766. [CrossRef]

- Saldivia-Siracusa C, Araújo AL, Arboleda LP, Abrantes T, Pinto MB, Mendonça N, Cordero-Torres K, Gilligan G, Piemonte E, Panico R, De-Abreu-Álves F, Villaroel-Dorrego M. Insights into incipient oral squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive south-american study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2024 Jul 1;29(4):e575-e583. PMID: 38794942; PMCID: PMC11249374. [CrossRef]

- Daroit NB, Martins LN, Garcia AB, Haas AN, Maito FLDM, Rados PV. Oral cancer over six decades: a multivariable analysis of a clinicopathologic retrospective study. Braz Dent J. 2023 Dec 22;34(5):115-124. PMID: 38133466; PMCID: PMC10759960. [CrossRef]

- Palefsky JM, Silverman S Jr, Abdel-Salaam M, Daniels TE, Greenspan JS. Association between proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and infection with human papillomavirus type 16. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995 May;24(5):193-7. PMID: 7616456. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya JD, Fitzpatrick SG, Islam MN, Bhattacharyya I, Cohen DM. A Retrospective 20-Year Analysis of Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia and Its Progression to Malignancy and Association with High-risk Human Papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol. 2018 Dec;12(4):500-510. Epub 2018 Feb 9. PMID: 29427033; PMCID: PMC6232220. [CrossRef]

- Bagan JV, Jimenez Y, Murillo J, Gavaldá C, Poveda R, Scully C, Alberola TM, Torres-Puente M, Pérez-Alonso M. Lack of association between proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and human papillomavirus infection. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007 Jan;65(1):46-9. PMID: 17174763. [CrossRef]

- García-López R, Moya A, Bagan JV, Pérez-Brocal V. Retrospective case-control study of viral pathogen screening in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia lesions. Clin Otolaryngol. 2014 Oct;39(5):272-80. PMID: 25099922. [CrossRef]

- Morandi L, Gissi D, Tarsitano A, Asioli S, Gabusi A, Marchetti C, Montebugnoli L, Foschini MP. CpG location and methylation level are crucial factors for the early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma in brushing samples using bisulfite sequencing of a 13-gene panel. Clin Epigenetics. 2017 Aug 15;9:85. PMID: 28814981; PMCID: PMC5558660. [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Pomares A, Llorens C, Soriano B, Bagan L, Moreno A, Calabuig-Fariñas S, Jantus-Lewintre E, Bagan J. Differentially methylated genes in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia reveal potential malignant biomarkers for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2021 May;116:105191. Epub 2021 Feb 28. PMID: 33657465. [CrossRef]

- Okoturo E, Green D, Clarke K, Liloglou T, Boyd MT, Shaw RJ, Risk JM. Whole genome DNA methylation and mutational profiles identify novel changes in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2023 Jun;135(6):893-903. Epub 2023 Mar 17. PMID: 37088660. [CrossRef]

- Villa A, Menon RS, Kerr AR, De Abreu Alves F, Guollo A, Ojeda D, Woo SB. Proliferative leukoplakia: Proposed new clinical diagnostic criteria. Oral Dis. 2018 Jul;24(5):749-760. Epub 2018 May 2. PMID: 29337414. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-García P, González-Moles MÁ, Mello FW, Bagan JV, Warnakulasuriya S. Malignant transformation of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1896-1907. Epub 2021 May 19. PMID: 34009718. [CrossRef]

- Kovalski LNS, Zanella VG, Jardim LC, Só BB, Girardi FM, Kroef RG, Barra MB, Carrard VC, Martins MD, Martins MAT. Prognostic factors from squamous cell carcinoma of the hard palate, gingiva and upper alveolar ridge. Braz Oral Res. 2022 May 2;36:e058. PMID: 36507745. [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Pomares A, Hervás D, Bagan-Debon L, Proaño A, Garcia D, Sandoval J, Bagan J. Oral cancers preceded by proliferative verrucous leukoplakia exhibit distinctive molecular features. Oral Dis. 2024 Apr;30(3):1072-1083. Epub 2023 Mar 21. PMID: 36892444. [CrossRef]

- Bagan J, Sarrion G, Jimenez Y. Oral cancer: clinical features. Oral Oncol. 2010 Jun;46(6):414-7. Epub 2010 Apr 18. PMID: 20400366. [CrossRef]

- Hirata RM, Jaques DA, Chambers RG, Tuttle JR, Mahoney WD. Carcinoma of the oral cavity. An analysis of 478 cases. Ann Surg. 1975 Aug;182(2):98-103. PMID: 813586; PMCID: PMC1343824. [CrossRef]

- Oliver AJ, Helfrick JF, Gard D. Primary oral squamous cell carcinoma: a review of 92 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996 Aug;54(8):949-54; discussion 955. PMID: 8765383. [CrossRef]

- Mashberg A, Merletti F, Boffetta P, Gandolfo S, Ozzello F, Fracchia F, Terracini B. Appearance, site of occurrence, and physical and clinical characteristics of oral carcinoma in Torino, Italy. Cancer. 1989 Jun 15;63(12):2522-7. PMID: 2720601. [CrossRef]

- Bagan JV, Jimenez Y, Sanchis JM, Poveda R, Milian MA, Murillo J, Scully C. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: high incidence of gingival squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003 Aug;32(7):379-82. PMID: 12846783. [CrossRef]

- González-Ruiz I, Ramos-García P, Ruiz-Ávila I, González-Moles MÁ. Early Diagnosis of Oral Cancer: A Complex Polyhedral Problem with a Difficult Solution. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Jun 21;15(13):3270. PMID: 37444379; PMCID: PMC10340032. [CrossRef]

- González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, Ramos-García P. Prognosis Parameters of Oral Carcinomas Developed in Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Sep 28;13(19):4843. PMID: 34638327; PMCID: PMC8507842. [CrossRef]

- Tan Y, Wang Z, Xu M, Li B, Huang Z, Qin S, Nice EC, Tang J, Huang C. Oral squamous cell carcinomas: state of the field and emerging directions. Int J Oral Sci. 2023 Sep 22;15(1):44. PMID: 37736748; PMCID: PMC10517027. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Cancer (n=90) | PVL-Cancer (n=50) |

| Age | ||

| mean (sd) | 69.51 (11.27) | 66.62 (11.59) |

| median (q1, q3) | 70 (60.25, 77) | 66 (59, 73.75) |

| Gender | ||

| M | 59 (65.56 %) | 15 (30 %) |

| F | 31 (34.44 %) | 35 (70 %) |

| Location.cancer | ||

| Gingiva | 26 (28.89 %) | 25 (50 %) |

| Buccal mucosa | 8 (8.89 %) | 8 (16 %) |

| Tongue | 37 (41.11 %) | 9 (18 %) |

| Lips | 2 (2.22 %) | 7 (14 %) |

| Floor of the mouth | 6 (6.67 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Palate | 11 (12.22 %) | 1 (2 %) |

| Clinical.type | ||

| Erytrholeukoplakia | 7 (7.78 %) | 15 (30 %) |

| Ulcerative | 57 (63.33 %) | 21 (42 %) |

| Exophitic | 16 (17.78 %) | 11 (22 %) |

| Mixed | 10 (11.11 %) | 3 (6 %) |

| Stage | ||

| Early | 52 (57.78 %) | 40 (80 %) |

| Advanced | 38 (42.22 %) | 10 (20 %) |

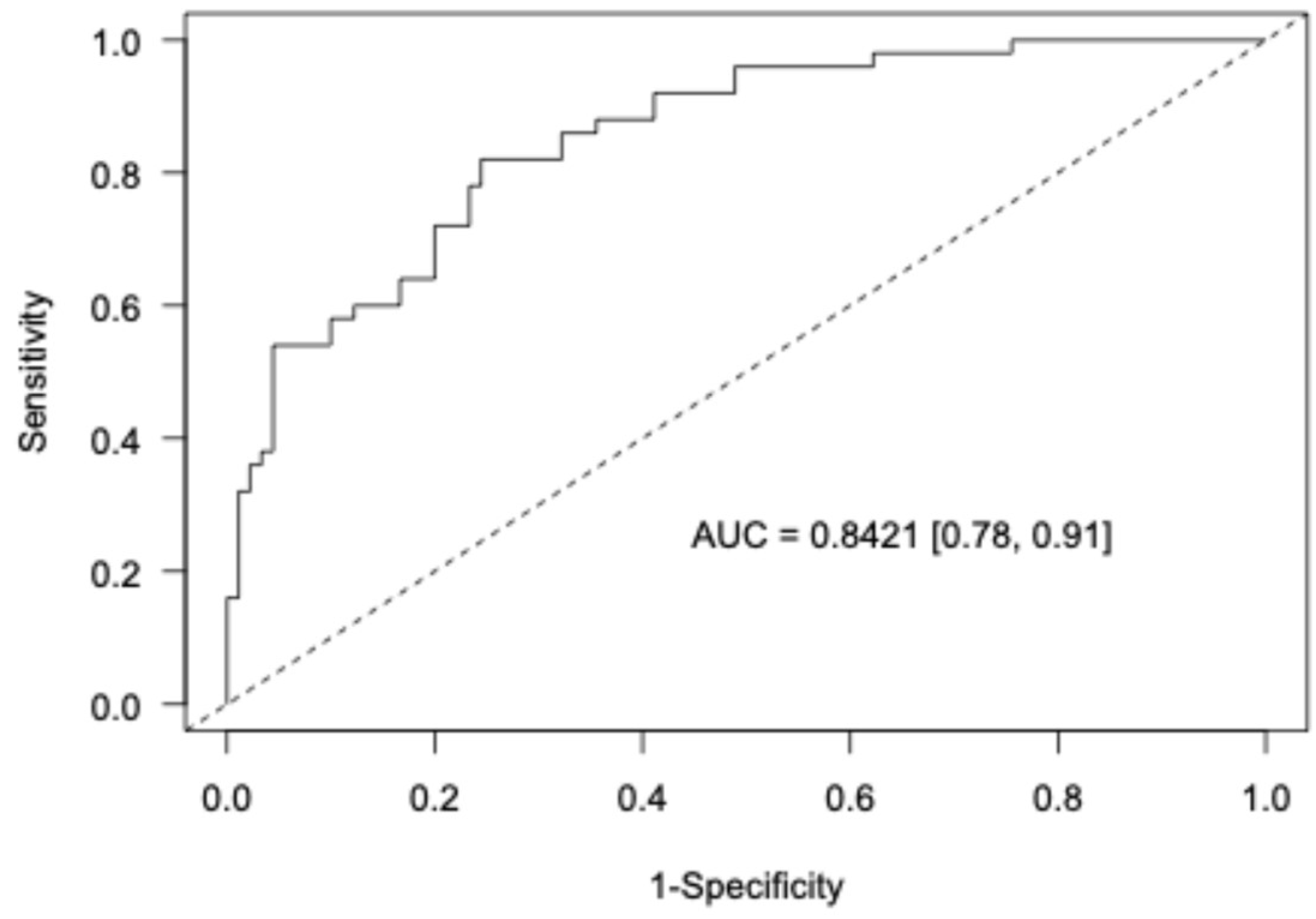

| Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | OR | 95% CrI | Prob. effect |

| Intercept | 0.432 | 0.757 | - | [-1.1, 1.9] | 0.711 |

| Location buccal mucosa | 0.865 | 0.712 | 2.376 | [0.58, 10.0] | 0.891 |

| Location tongue | -1.16 | 0.546 | 0.313 | [0.10, 10.0] | 0.988 |

| Location lips | 1.028 | 0.951 | 2.797 | [0.49, 21.7] | 0.867 |

| Location floor of the mouth | -3.496 | 1.799 | 0.03 | [0.001, 0.64] | 0.993 |

| Location palate | -2.017 | 1.128 | 0.133 | [0.01, 1.0] | 0.974 |

| Stage advanced | -1.095 | 0.524 | 0.335 | [0.11, 0.91] | 0.985 |

| Gender F | 1.621 | 0.507 | 5.058 | [1.9, 14.0] | 1 |

| Clinical type Ulcerative | -1.578 | 0.656 | 0.206 | [0.06, 0.73] | 0.993 |

| Clinicaltype Exophitic | -1.047 | 0.733 | 0.351 | [0.08, 1.46] | 0.924 |

| Clinical type Mixed | -1.916 | 0.961 | 0.147 | [0.02, 0.90] | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).