The working of the physical world can by and large be described by certain mathematical laws [

1]. For centuries, mathematical models have been established to ‘depict’ observed physical, mental and even societal phenomena and have been used in industry and society to design and manufacture new products, as well as to provide improved services. On the other hand, there are instances where mathematical theorems have directly materialized physical objects that have practical significance. For example, the well-known Penrose tilling [

2] that has been proved by mathematical theorems in pure geometry [

3] to tile a plane aperiodically has been widely used in architecture and decoration [

4].

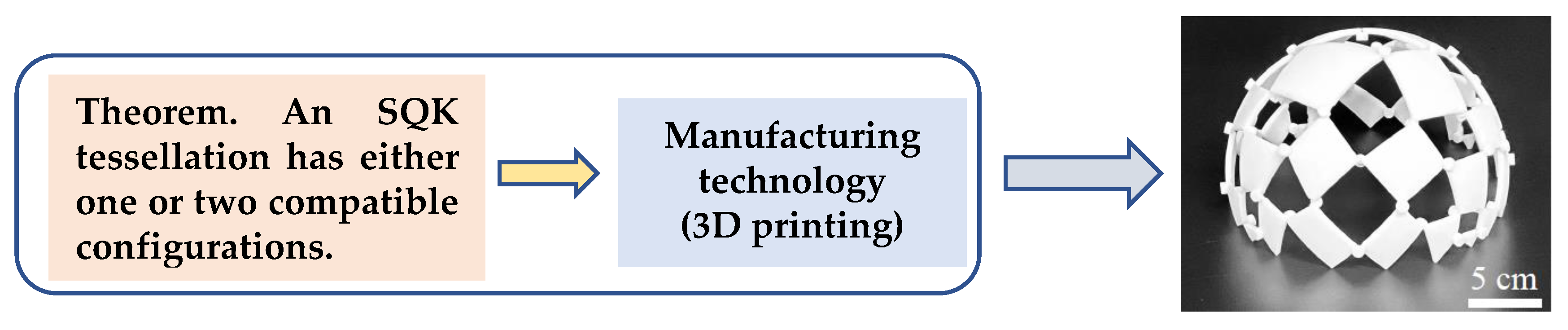

Kirigami is a traditional art for decoration; however, today, it is a promising technology for designing and fabricating novel morphing structures at different scales such as small stents in biomedical engineering and large solar sails in aerospace engineering. The deployability of kirigami is characterized by the motion of the panels around their joints. Rigid deployability, meaning the panels do not deform but only translate and rotate around the joints, has important implications in that it minimizes the degrees of freedom so as to greatly facilitate control in applications. Therefore, the precise design and economical manufacture of kirigami structures are largely governed by kinematics and geometry. Without the deformation of the panels, the deployability of kirigami is governed solely by geometry. Planar kirigami structures have been designed and fabricated based strictly on geometrical theorems [

5,

6]. For kirigami on curved surfaces, Dang et al. [

7] have established a theorem that stipulates the rigid deployability of spherical quadrilateral kirigami (SQK) that they then used to make a kirigami dome with the 3D printing technique (

Figure 1). The work of Dang et al. [

7] points to a new paradigm that it is possible to integrate rigorous mathematics with state-of-the-art manufacturing technology to produce new products.

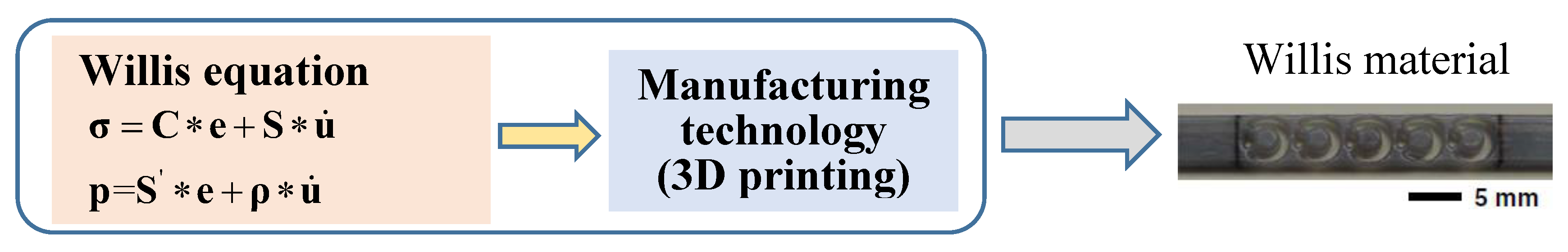

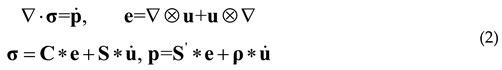

The development of the materials and structures with the function of electro-magnetic and acoustic cloaking has been a fertile field due to their intriguing properties and wide applications. In this regard, mathematics has played a vital role. The so-called Willis media – a kind of metamaterials – is an example based on a mathematical theory. The mechanics of solid materials is conventionally described by the Navier equation

where ρ denotes the density of the material,

u the displacement vector of a material point,

C the stiffness tensor of the material, ∇ (nabla) here denotes the gradient operator, and

f is the density of body force. With the development of new materials, and especially the emergence of metamaterials that exhibit unconventional properties, it appears that if the governing equation satisfies form-invariance under a certain curvilinear transformation, then a novel type of materials can be made to modulate the elastic and acoustic waves to realize intriguing functions of cloaking [

8]. However, the required form-invariance is not satisfied by the classical Navier equation (1), but by a new governing equation

This is the so-called Willis formalism [

8,

9]. Here,

p denotes the momentum vector, and

C,

S,

S′ and

ρ along with the sign ∗ are non-local operators imposed on the augments.

Based on the theoretical Willis formalism [

8,

9], a new category of metamaterials, the so-called Willis materials, has been invented, which has provided fertile ground for developments in physics, mechanics, materials science and engineering, and mechanical engineering [10-20]. Willis materials have important applications in the control of acoustic and elastic waves. Not surprisingly, a lot of research has been devoted to their practical realization [13-18]. Liu et al. [

16] have realized a Willis material with the 3D printing technology (

Figure 2). The material can be used to produce high-quality sensors and elastic wave cloaks. Chen et al. [

18] have designed and fabricated an active Willis meta-layer in beams and plates to independently modulate the transmission and reflection of flexural waves.

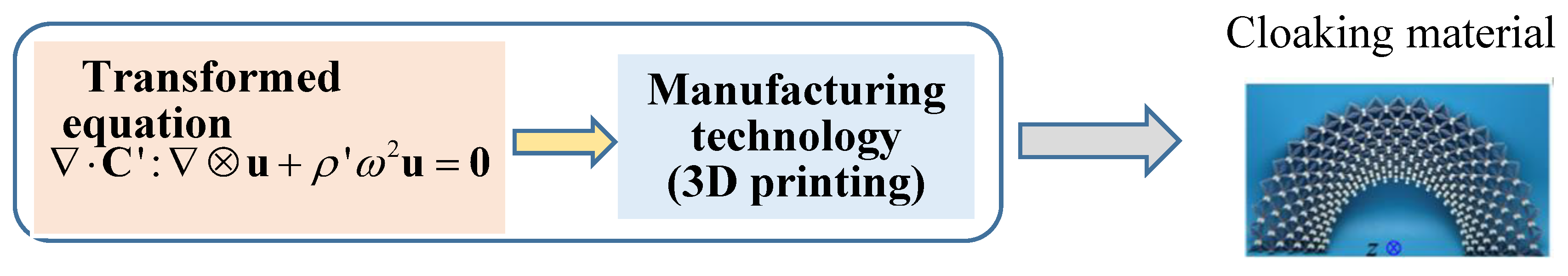

Brun et al. [

21] found that cloaking in elasticity can be achieved with an elastic constant tensor lacking minor symmetry. Then, Nassar et al. [

22] proposed the microstructural design of achieving such elastic constant tensors without minor symmetry. Based on the theory, Xu et al. [

23] have realized a perfect elastic cloaking material with the 3D printing technology (

Figure 3).

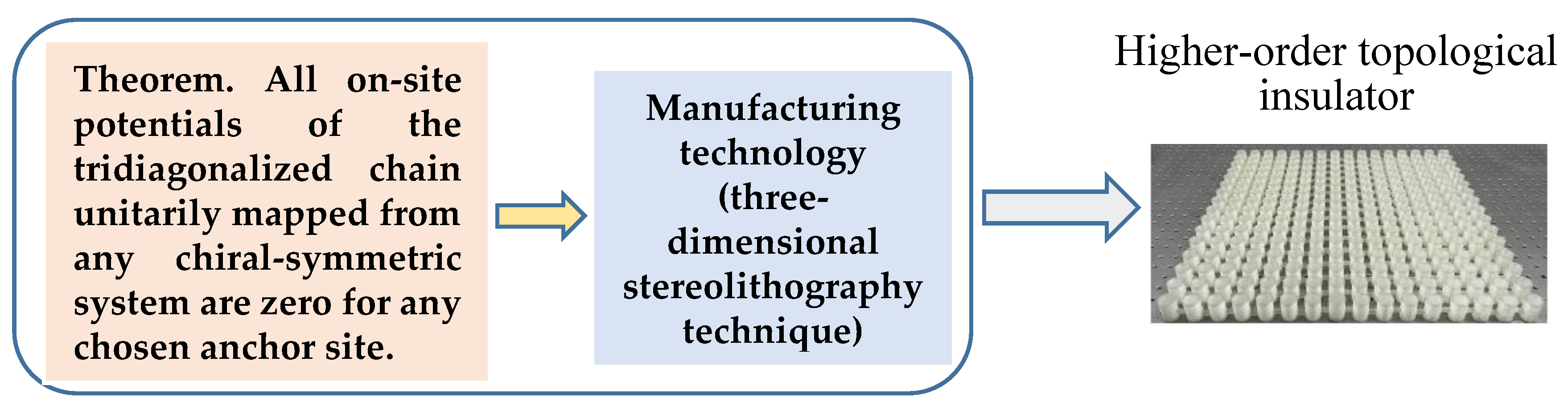

Topological insulators of different orders have an intimate correlation with mathematics. Among them, the so-called higher-order topological insulators have been attracting significant attention for they can realize any integer number of topological states at interfaces of materials. Recently, Sun et al. [

24] have constructed a new kind of higher-order topological insulators which can localize energy at arbitrary multiple sites within the whole structures without introducing material interfaces. This construction is based on a theorem for the improved Householder tridiagonalization of matrices. Sun et al. [

24] have designed and fabricated a higher-order topological insulator that exhibits the demanded localization of energy at multiple sites including the corners, edges and within the bulk of the material without the need for altering the structure, i.e. without introducing interfaces (

Figure 4). Moreover, they also demonstrated that multiple localization sites can be programmed to facilitate improving the sensitivity of sensors for detecting and imaging objects.

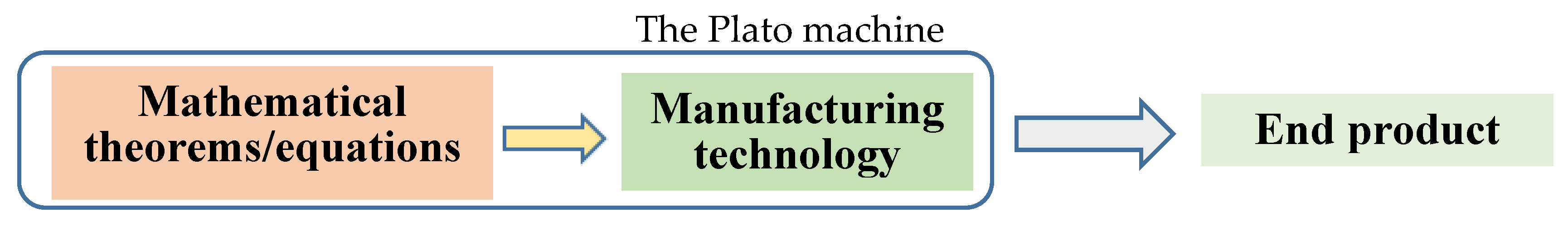

It is clear that the above examples have the same pattern, i.e. the production of physical objects is directly based on rigorous mathematical theorems or equations. This pattern can be universally represented by a simple scheme, shown in

Figure 5. This integrated system of mathematics and manufacturing technology that produces physical objects is here termed the Plato machine. The systems that manufacture new products in terms of physical laws may be regarded as generalized Plato machines.

The above direct transformation of mathematical theories into physical objects on a case-by-case basis was the product of human intelligence and effort. Nowadays, artificial intelligence (AI) can generate symbolic governing equations from data [25-29], auto-discover laws of geometric and physical conservation [

30,

31] and discover both the governing parameters and equations of natural phenomena from videos [

32,

33]. It is likely that a time will come when mathematical theorems and new governing equations are discovered by AI such that the whole process of mathematics-based inventions can be automated with minimal human supervision, hopefully to enrich the lives of human beings. It can be argued that not all theories predicted or discovered by AI can be easily materialized, at least in the immediate future. That is quite likely to be true, but if some of them can be materialized into useful products, that should suffice. In this connection, it is interesting to note that in 2006, when envisaging the new materials being constructed based on the Willis theory, Milton et al. [

8] speculated that “

it is far from clear that the desired composites” could be realized; it would “

be a tall order to physically build these materials.” It took only about ten years to realize these materials! It has been demonstrated that computational approaches have facilitated art-inspired design of metamaterials [

34]. The integration of mathematics and advanced manufacturing technology will be a promising avenue for design and production of new products.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Emeritus Professor Bhushan L. Karihaloo of Cardiff University, Professor Guoliang Huang and Dr Fan Feng of Peking University, Professor Linjuan Wang of Beihang University, and Professor Yongquan Li of Xi’an Jiaotong University for helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Penrose, R. The Road to Reality — A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. New York: Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, Inc., 2004.

- Penrose, R. The role of aesthetics in pure and applied mathematical research. Bulletin of the Institute of Mathematics and Its Applications. 1974;10: 266—271.

- Grunbaum B, Shephard GG. Tillings and Patterns. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company, 1987.

- Available online: https://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/Penrose+tiling#CITEREFPenrose1978.

- Choi GPT, Dudte LH, Mahadevan L. Compact reconfigurable kirigami. Physical Review Research. 2021; 3: 043030.

- Dang X, Feng F, Duan HL. Wang J. Theorem for the design of deployable kirigami tessellations with different topologies. Physical Review E. 2021; 104: 055006.

- Dang X, Feng F, Duan HL, Wang J. Theorem on the compatibility of spherical kirigami tessellations. Physical Review Letters. 2022; 128: 035501.

- Milton GW, Briane M, Willis JR. On cloaking for elasticity and physical equations with a transformation invariant form. New Journal of Physics. 2006; 8: 248.

- Willis, JR. Variational principles for dynamic problems for inhomogeneous elastic media. Wave Motion. 1981: 3:1–11.

- Shuvalov AL, Kutsenko AA, Norris AN, Poncelet O. Effective Willis constitutive equations for periodically stratified anisotropic elastic media. Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 2011; 467: 1749–1769.

- Muhlestein MB, Sieck CF, Alù A, Haberman MR. Reciprocity, passivity and causality in Willis materials. Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 2012; 472: 20160604.

- Nassar H, He QC, Auffray N. Willis elastodynamic homogenization theory revisited for periodic media. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids. 2015; 77: 158–178.

- Muhlestein MB, Sieck CF, Wilson PS, Haberman MR. Experimental evidence of Willis coupling in a one-dimensional effective material element. Nature Communications. 2017; 8:15625.

- Yao RW, Gao HX, Sun YX, Yuan XD, Xiang ZH. An experimental verification of the one-dimensional static Willis-form equations. International Journal of Solids and Structures. 2018; 134:283—292.

- Quan L, Ra’di Y, Sounas DL, Alù A. Maximum Willis coupling in acoustic scatterers. Physical Review Letters. 2018; 120: 254301.

- Liu Y, Liang Z, Zhu J, Xia L, Mondain-Monval O, Brunet T, Alù A, Li J. Willis Metamaterial on a structured beam. Physical Review X. 2019; 9: 011040.

- Zhai Y, Kwon H-S, Pop B-I. Active Willis metamaterials for ultracompact nonreciprocal linear acoustic devices. Physical Review B. 2019; 99: 220301(R).

- Chen Y, Li X, Hu G, Haberman MR, Huang GL. An active mechanical Willis meta-layer with asymmetric polarizabilities. Nature Communications. 2020; 11:3681.

- Peng Y-G, Mazor Y, Alù A. Fundamentals of acoustic Willis media. Wave Motion. 2022; 112: 102930.

- Qu H, Liu X, Hu G. Mass-spring model of elastic media with customizable Willis coupling. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences. 2022; 224:107325.

- Brun M, Guenneau S, Movchan AB. Achieving control of in-plane elastic waves. Applied Physics Letters. 2009; 94: 061903.

- Nassar H, Chen YY, Huang GL. A degenerate polar lattice for cloaking in full two-dimensional elastodynamics and statics. Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 2018; 474: 20180523.

- Xu X, Wang C, Shou W, Du Z, Chen Y, Li B, Matusik W, Hussein N, Huang GL. Physical realization of elastic cloaking with a polar material. Physical Review Letters. 2020; 124: 114301.

- Sun Y, Wang L, Duan HL, Wang J. A new class of higher-order topological insulators that localize energy at arbitrary multiple sites. Science Bulletin. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bongard J, Lipson H. Automated reverse engineering of nonlinear dynamical systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007; 104: 9943–9948.

- Bruntona SL, Proctor JL, Kutz JN. Discovering governing equations from data by sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016; 113: 3932–3937.

- Kim S, Lu PY, Mukherjee S, Gilbert M, Jing L. Integration of neural network-based symbolic regression in deep learning for scientific discovery. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems. 2021; 32: 4166—4177.

- Udrescu S-M, Tegmark M. AI Feynman: A physics-inspired method for symbolic regression. Science Advances. 2020; 6: eaay2631.

- Schmidt M, Lipson H. Distilling free-form natural laws from experimental data. Science. 2009; 324: 81—85.

- Manti S, Lucantonio A. Discovering interpretable physical models using symbolic regression and discrete exterior calculus. Machine Learning: Science and Technology. 2024; 5: 015005.

- Liu Z, Tegmark M. Machine learning conservation laws from trajectories. Physical Review Letters. 2021; 126: 180604.

- Chari P, Talegaonkar C, Ba Y, Kadambi A. Visual physics: Discovering physical laws from videos. 2019; arXiv:1911.11893.

- Udrescu SM, Tegmark M. Symbolic pregression: Discovering physical laws from distorted video. Physical Review E. 2021; 103: 043307.

- Choi GPT. Computational design of art-inspired metamaterials. Nature Computational Science. 2024; 4: 549–552.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).