1. Introduction

The correct estimation of the state of charge of a battery is essential. In addition to the accuracy, the speed of the convergence behavior, the temperature dependence and the behavior during long-term measurements are also of great importance. In the field of home storage and also in the automotive sector, the reliability of the estimate plays a major role. In the automotive sector, the possible range of the vehicle can be calculated directly from the state of charge [

1,

2,

3].

For lithium-ion batteries, various methods and algorithms for state of charge determination exist. The simplest method is to integrate the current flowing in and out of the battery over time. This method is called Coulomb Counting. The advantage of Coulomb Counting is its short computation time, since here only a simple addition and multiplication takes place. The method is therefore also fully real-time capable and is the basis for other techniques. Coulomb Counting has two significant drawbacks: it cannot detect and correct an incorrect state of charge, and it integrates measurement errors. An incorrect state means that the procedure does not know the initial state, which is however necessary to calculate the new state. This can happen if the battery management system loads the initial state incorrectly or if the initial state is unknown, for example with new batteries.

Mathematical filters can be used to counteract this problem. Probably the best known filter is the Kalman filter [

4]. The Kalman filter combines measured values with model values. The measured values come from Coulomb Counting and are subject to the same advantages and disadvantages as described above. Model values are added to the filter to compensate the disadvantages mentioned above. The battery model can be an equivalent circuit model describing the behavior of the battery at different temperatures, states of charge and currents. The filter weights the measured values and model values at each time step to determine the best possible state of the system, in this case, the state of charge of the battery.

Another comparable and well-known filter from control theory is the H-Infinity filter [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The H-Infinity filter is an estimation technique that aims to minimize the influence of noise and interference in a system. The filter also uses measured values and model values to estimate the states of a system, minimizing the variance of the disturbances. The filter provides the best possible estimate in terms of disturbance reduction, while the Kalman filter uses the mean square deviation between the estimate and the true state. On the one hand, the H-Infinity filter is more robust to uncertainties and model errors than the Kalman filter, which can be more sensitive to such errors. On the other hand, the H-Infinity filter is more complex to model and implement for any system.

Although our primary focus is on the comparative analysis of Kalman and H-Infinity filters due to their similarity and widespread adoption, we briefly mention alternative approaches such as particle filters, machine learning and neural networks to acknowledge the breadth of research in SOC estimation and to provide a comprehensive overview of the evolving landscape of battery management techniques [

2,

9]. The particle filter uses a probabilistic approach and works with a set of samples or ”particles” . Each particle represents a possible state of the system. Particles are weighted according to the probability that a particle corresponds to the actual state of the system, based on measurements. The particle filter can be computa- tionally intensive due to the use of a particle set, especially if the number of particles is high. This can affect the efficiency of the filter in real-time applications, as it requires a larger number of calculations compared to other filtering methods.

The neural network method involves collection of large data sets on the battery state and input param- eters, preparation and partitioning of the data into training, validation, and test sets, training with the data, validation, and finally application of the trained network. The disadvantages of neural networks compared to the filtering methods described above are the high demand for training data, the black-box approach without interpretable rules, the susceptibility to outliers, and the limited extrapolation capability when, for example, the battery ages [

9,

10].

In order to find the appropriate method for a specific application, a comparison of the methods is necessary. On the one hand the accuracy of the result is relevant, on the other hand the computation time is important. In this paper, we focus on the two filtering methods Kalman filter and H-Infinity filter. These are based on the same battery model and are similar in their implementation at the software level. The particle filter and neural networks are not discussed in this paper because they are not comparable to the other filters in terms of structure and complexity.

For the objective comparison of the filters for a given battery we implemented the Kalman filter and the H-Infinity filter and their most common extensions. The Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) for non-linear systems, which extends the models by linearizing system and measurement models. The Adaptive Extended Kalman Filter (AEKF) improves the EKF by additionally adjusting the process and noise covariance matrices during the filtering process. The Dual Extended Kalman Filter (DEKF) splits the state vector into multiple parts and filters them separately to reduce filter complexity and increase estimation accuracy. As an alternative for nonlinear systems, the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) is available, which uses the Un- scented Transform to achieve a better approximation of the probability distribution. For the H-Infinity Filter, the two variants Adaptive H-Infinity Filter and Dual H-Infinity Filter have been implemented. The mode of operation is the same as for the Kalman filter extensions.

Campestrini et al. have developed a method in [

11] to compared the Kalman-Filter against the extended Kalman-Filter. Six criteria were defined, each of which is given a score. The higher the score, the better the result. However, the running time of the algorithms is not evaluated in [

11], so in this paper the two filters, Kalman and H-Infinity filters, were implemented on a digital signal processor (DSP). Due to the constant running time of both filters and the deterministic behavior of a DSP, implementing them on the DSP makes sense and provides an objective comparison.

Various methods exist for modeling a battery. There are mainly two different approaches: electrochem- ical models (white box model) and equivalent circuit models (grey box model) [

12]. In this paper, the battery model (ECM) was generated using the newly developed method from [

13]. This model relies on an equivalent circuit. It consists of an open-circuit voltage source in series with a resistor and one to four RC elements connected in series (R and C are each connected in parallel). The model can be extended with more RC elements, but we could not see any improvement in the results and therefore the model was limited to a maximum of four RC elements. More RC elements would only increase the computation time in our case. All mentioned electrical components have to be parameterized. Bruch et al use a current pulse method with subsequent fitting in [

13]. Short current pulses are applied to the battery and the voltage response is recorded. This is done for different states of charge, temperatures and currents. Subsequently, the measured data is fitted to the present equivalent circuit using an optimizer. The results of the fitting are a battery model, which is the basis for both filters.

This paper is organized as follows. First we introduce the methods and describe briefly basic principles of a digital signal processor in

Section 2. In

Section 3 the experimental setup is described. The testing profiles and the test procedure is presented in

Section 4. After the definition of the evaluation criteria in

Section 5we show the results in

Section 6 and finally in

Section 7we conclude the paper.

2. Filter Methods and Digital Signal Processing

2.1. Kalman Filter

The Kalman filter (KF) was first introduced by R.E. Kalman in 1960 as new approach to linear filtering [

4]. Based on a model consisting of differential equations the filter predicts the state of a physical process.

By adapting the state variables the algorithm minimizes the error between the measured and predicted output [

4]. The model represents the knowledge of the physical process and the changes due to the input. Contrary the measurement shows the current state of the physical system as another input for the filter. The task of the filter is to determine the best estimation of the real value of the system using the model and the measurement. A predetermined weighting factor for measurement and model noise show the level of trust for each of the sources. These factors as well as the initial state and covariance have to be provided to the filter. Finding values which lead to good estimation behavior is called filter tuning. Often this procedure is done offline before the operation with a parameter variation [

14]. The Kalman filter operates through a distinct initialization phase that occurs only once at the beginning. Subsequently, at each time step of the system, it goes through a cyclical process consisting of prediction, computation of the correction gain, and application of the correction.

Since a battery model is not a linear system, the concept of the extended Kalman filter (EKF) was introduced. The EKF linearises the non-linear system by a first-order Taylor approximation. This, of course, can add inaccuracies to the calculations and can cause the filter to diverge [

15]. Despite the potential for inaccuracies and divergence due to the linearization process in the extended Kalman filter, its utilization remains prevalent because it provides a practical balance between computational complexity and the ability to handle non-linear system dynamics effectively. Another filter variation is the adaptive extended Kalman filter (AEKF). This filter skips the offline filter tuning by online calculations of the measurement and process noises. Moreover, the filter can adjust itself to changing environmental influences. Everytime step the noise values are adapted on basis of the error between measured and predicted output voltage [

11,

12,

16].

The dual extended Kalman filter (DEKF) estimates not only the SOC of the battery but also keeps track of the model parameters of the ECM, especially the actual battery capacity which is necessary to calculate the state-of-health. All parameters of the ECM underline measurement errors and change over time due to ageing effects. The DEKF consists of two extended Kalman filters which run in parallel. For the SOC estimation the EKF stays the same as described earlier [

17,

18]. Since the ECM parameters cannot be predicted, only the covariance values are updated. For the ECM parameter correction, the state vector of the SOC estimation is used. The updated ECM parameter vector is then the input for the next time step of the SOC estimation [

17,

19].

The unscented Kalman filter (UKF) has a different structure than the other filters, since it does not use the first order Taylor approximation. Instead, it is based on the unscented transformation for the linearization and uses sigma points. Instead of calculating the Jacobian for the linearisation of the function, the filter uses random samples of the Gaussian-random-variable [

20]. The model can approximate the expected value and the covariance of a random variable which is propagated through a non-linear function. This is achieved by omitting the derivation of system and measurement matrices [

21,

22].

2.2. H-Infinity Filter

The H-Infinity filter, also known as the H∞ filter, is an estimation algorithm based on control theory and signal processing [

5]. It is designed to deal with uncertainties, disturbances and noise in dynamic systems, making it suitable for battery state estimation tasks. The main objective of the H-Infinity filter is to minimize the effects of disturbances and measurement errors on estimation accuracy and to provide robust and reliable state estimates [

23,

24].

In the context of battery state estimation, the H-Infinity filter uses a mathematical model that describes the behavior of the battery and combines it with available measurements. The model captures the dynamic relationship between battery state variables, such as voltage, current, temperature, and SoC or SoH [

25]. By incorporating this model into the H-Infinity filter, it is possible to estimate battery state with improved accuracy and resistance to noise and uncertainty [

24].

The filter works in two main steps: prediction and correction. In the prediction step, the current state estimate is updated based on the model dynamics and the previously estimated state. This step uses control theory principles, such as state-space representations and Kalman filtering techniques, to project the sys- tem’s state forward in time. The correction step involves incorporating new measurements to refine the state estimate. The H-Infinity filter optimally combines the predicted state with the measurements, taking into account the uncertainties and noise present in both the model and the measurements. It uses optimization methods, such as linear matrix inequalities and convex optimization, to find the best estimate that minimizes the impact of disturbances and errors [

26].

The H-infinity also comes with different variations. In this work the adaptive and dual types were used. Both filter types work in the same way as their Kalman filter counterparts.

2.3. Digital Signal Processors (DSP)

Digital signal processors (DSPs) are specialized hardware for the computation of digital signals. Computation speed and reliability are key parameters for handling continuous input data streams. Critical controlapplications like medical diagnostics or other real-time dependent tasks often use DSPs [

27,

28].

The processors are optimized for the calculation rather than manipulation of digital data or testing of values. DSPs usually go back to the Harvard processor architecture than to the Von Neumann architecture. This massively improves data processing since the architecture uses separate memory to store data and program. The Super Harvard architecture even allows data to be stored in the program memory which can be used to load two data values into the core at the same time.

In this work a DSP is used for state estimation, the CPU cycles needed for the filters applied are mea- sured and compared. Complex pipeline structures as in general-purpose CPUs can be skipped because DSP tasks usually are pure mathematics which do not have cyclic conditions that must be proved. For more advanced and calculation intensive processes for which loops are crucial, the DSP provides additional hard- ware, called zero-overhead-loop, which makes the loop executable without the overhead of checking the loop conditions. This makes DSP programs predictable, fast and even cycle precise and a DSP is best suited for real-time applications [

29].

3. Experimental Setup

The batteries used were Samsung INR18650-29E lithium-ion cells. The specifications of the batteries were adapted for the stationary energy storage application found in [

30], which where implemented in the BMS software. In

Table 1 the specifications used can be found. The batteries were placed in a Weiss KWP 120/70 climate chamber and tested by a BaSyTec CTS-Lab tester.

All filters were implemented on the ADSP-21489 EZ-Board in C. The DSP had a processor frequency of 400 MHz and 5 Mbit internal memory. It was connected with a JTAG ICE and a USB connection to the computer. The software was written with the IDE VisualDSP++ 5.1.2 and used the standard matrix.h library.

The software implementation on the PC was written with Python 3.7.0 using Anaconda Spyder 3.3.1 and the numpy package 1.18.5.

Before the test a filter tuning was done. The ratio between the covariance values of the system and measurement noise matrices are important. Otherwise, the filters suffer from bad selected starting values. The simulation was a parameter sweep (over the initial values of the Kalman filter) done with Python. In contrast to [

31] different initial values for every filter were selected, because the filters scale differently with their parameters and the Kalman-filter and H-infinity-filter share just a subset of parameters. The influence of the number of RC-terms was investigated on the DSP, due to the predictability and cycle-precise execution.

4. Testing Profiles and Procedure

4.1. Profiles

Comparing the effect and accuracy of various SOC estimation methods can be difficult. A first step to a scientific basis is the use of generalized reproducible current profiles. Common profiles as the vehicle driving cycles like in [

32,

33,

34] not necessarily include all characteristics to compare different methods, especially if the application changes. In [

11] three profiles were presented for application independent tests. The three profiles were called A, B and C, respectively:

Table 1.

Specifications of the Samsung INR18650-29E lithium-ion cell. [

30].

Table 1.

Specifications of the Samsung INR18650-29E lithium-ion cell. [

30].

| Property |

Value |

| Charge cut-off voltage |

4.05 V |

| Discharge cut-off voltage |

2.5 V |

| Charging current rate |

0.5 C |

| Discharging current rate |

1.0 C |

| Capacity |

2200 mAh |

| Temperature range charging |

0 - 45 。C |

| Temperature range discharging |

-20 - 60 。C |

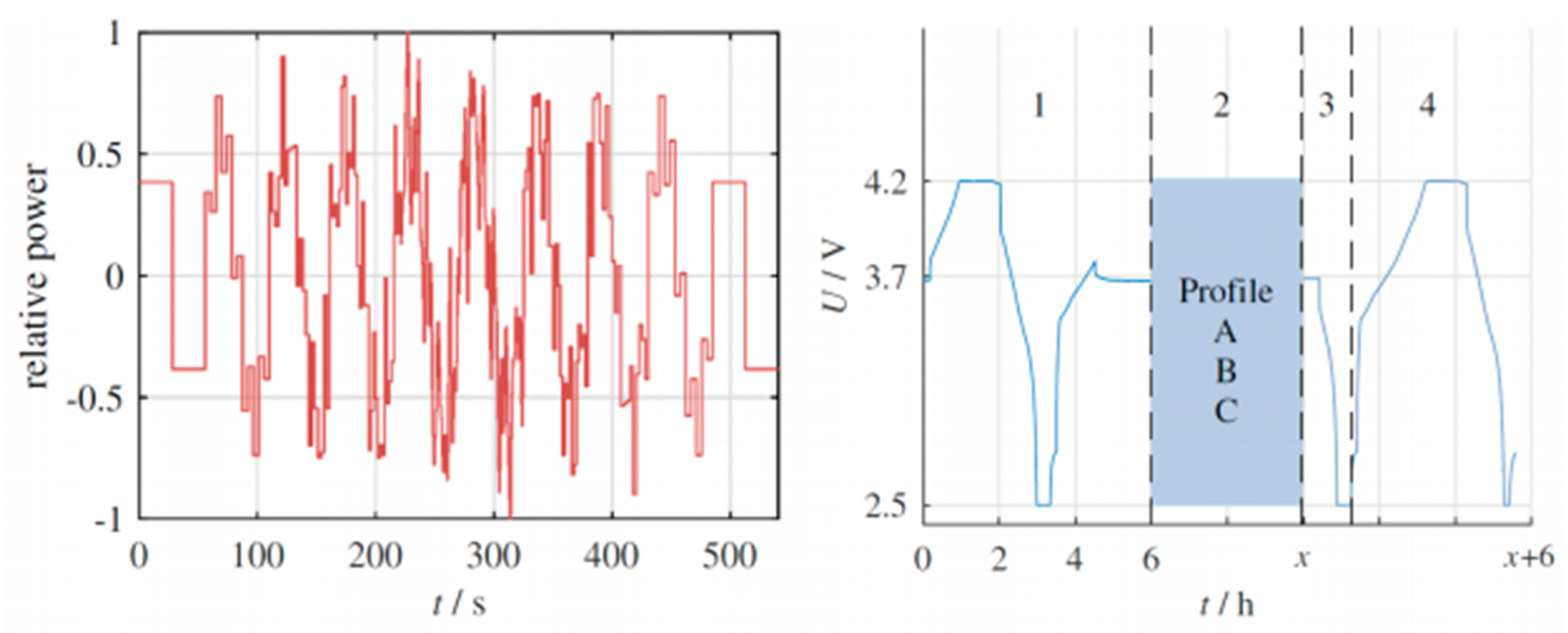

Profile A described the short term low dynamic behaviour

Profile B the short term high dynamic behaviour

Profile C the long-term behaviour with temperature variations.

The basis of all profiles was the synthetic load cycle (SLC) which was a normalized power profile, meaning that the sum of incoming and outgoing charge is zero. Each profile started with a CCCV charge and discharge cycle, following with a CCCV charge to the desired SOC value. After the test the residual charge was determined. For profile C the capacity of the battery must be measured after the test to see whether the capacity has changed during the test.

Figure 1 summarizes the general test setup.

4.2. Procedure

Test profile A was run at three different starting SOC values. The most distinct values for lithium-ion batteries are 10 %, 50% and 90 % [

11]. The profile started at 50% was then charged with a C-rate of 0.5 up to 90 %. After a relaxation time of 30 minutes the SLC was performed followed by another 30 minutes of relaxation. The discharge to10 % SOC was done with 1 C. Test profile A was setup for three different temperatures: 5 。C, 25 。C and 40 。C.

Test profile B was chained by SLC profiles shifted towards the discharge direction to artificially achieve a discharge behaviour for the high dynamic test [

11]. The profile started at 90 % SOC and goes down to 10 % SOC. Profile B ran at the same temperatures as profile A.

To assess the long-term stability of the system, Profile C is employed, with a particular emphasis on analyzing the predictive accuracy in response to temperature fluctuations. This profile is constructed upon the repeated execution of the coulomb-neutral SLC profile, maintaining the SOC consistently at 50%. Over a span of 24 hours, the temperature undergoes adjustments to three distinct test temperatures. Both the temperature transition and the stabilization period at the target temperature are allotted a duration of 3 hours each. Initially, the temperature in the chamber is raised from the starting point of 25°C to 40°C, followed by a rest phase. Subsequently, after the second interval, the temperature is brought back down to 25°C, succeeded by another period of rest. The subsequent step involves cooling the chamber to 5°C. After the final 3-hour rest phase, the temperature is once again elevated to 25°C. This entire cycle is reiterated seven times, culminating in a total profile period of seven days.

5. Evaluation Criteria

For a better comparison of different filter techniques a standardized scoring system was used. Here we only describe the criteria. A detailed mathematical derivation can be found in [

11]. [

11] proposed a system of six criteria with a scoring system from 0 (worst) to 5 (best). The criteria were estimation accuracy K

est , drift K

drift, residual charge determination K

res, transient behaviour K

trans , failure stability K

fail and temperature stability K

temp .

Table 2 shows the scoring system for different error boundaries ϵ [

11].

K

est evaluates the overall accuracy of the test. It describes the ratio between the time spend within an error boundary to the overall test time. This ratio is then multiplied with the corresponding score from

Table 2 and summed up for all boundaries.

K drift describes the accumulation of errors over a period of time. The goal is to evaluate if the filter estimation shows the same gradient as the reference SOC. K drift of profile A is the mean of the constant current charge and discharge period.

K res is determined after the test cycle by measuring the remaining capacity at the end of a test cycle and by measuring the actual battery capacity afterwards. Since the battery capacity may change over time, due to ageing and temperature effects, the true SOC value of the reference can be wrong.

Ktrans describes how fast the filter converges to the true SOC value if the start SOC was wrong. After 10 % of the test time Ktrans is calculated and scaled with the initial mismatch of the two values.

Ktemp shows how the state estimation filter behaves with changing temperatures. Most battery models use temperature sensitive parameters and the battery as well as the ambient temperature can change during operation. For all test, except for the failure stability, Ktemp is evaluated as the performance change due to different temperatures. Ktemp is then the sum of the standard deviations of each test.

The failure stability criterion was skipped in this work because of the additional complexity and timing demand to rerun all tests with incorrect voltage and current values and due to the extra requirements of changing the model parameters.

6. Results

The effectiveness of filter-based methods for state of charge estimation heavily relies on the accuracy of the battery model used. In this work, we utilized the model developed by [

13] and compared it with the one from [

31] to examine the effects of different modeling approaches and validation techniques. Our validation method and criteria are designed to be applicable to a wide range of lithium-ion battery models, reflecting a general approach suitable for various chemistries.

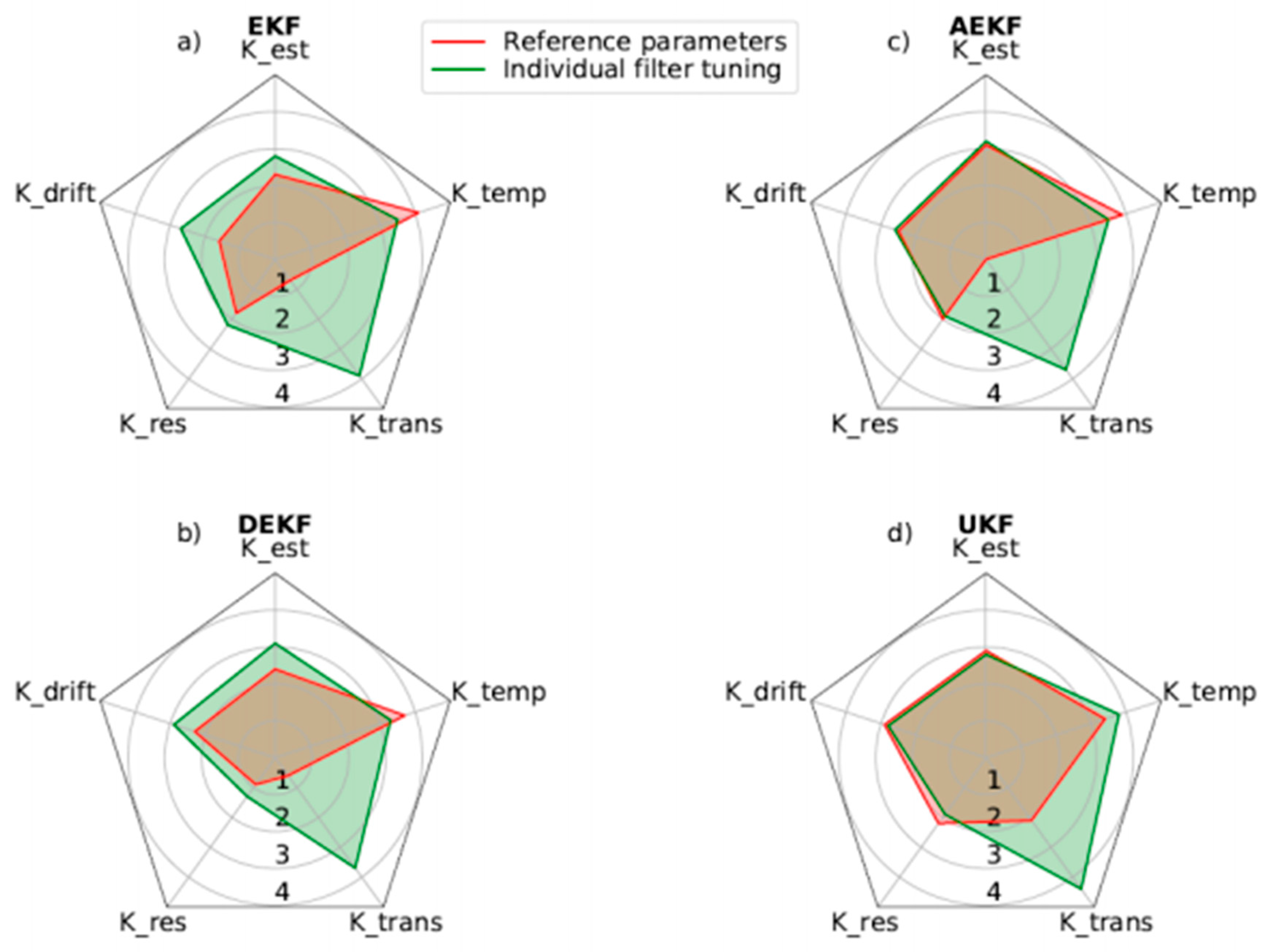

As shown in

Figure 2, the comparison between the reference from [

31] and our evaluation highlights the influence of using own battery models. Except for the temperature coefficient K temp, the performance of all criteria is significantly affected by the use of a different model. The smaller temperature range in our work, especially the lower scores at reduced temperatures, results in a reduced value for Ktemp.

The dependency on the battery model is evident in all other parameters, but the unscented Kalman filter stands out as it shows more consistent results, suggesting it is less sensitive to model variations. This is also due to a different approach to noise approximation and the consequences of using a mismatched battery cell,which introduces more noise.

Fine-tuning filter parameters is essential for each method. This work opted for a measurement noise matrix value that was significantly higher, by a factor of about 10,000, compared to [

31]. The covariance values for overpotentials had a minor impact across a wide range of parameters. A higher initial uncertainty in SOC estimation led to better transient behavior for all filters, as they could compensate for the expected initial inaccuracy. Initially, the convergence shown in

Figure 2 was not ideal because the filter parameters were not well-matched with the battery model. After adjusting the covariance matrix, the Ktrans score improved by 3.2 for the EKF, 3.7 for the AEKF, 3.1 for the DEKF, and 2.3 for the UKF.

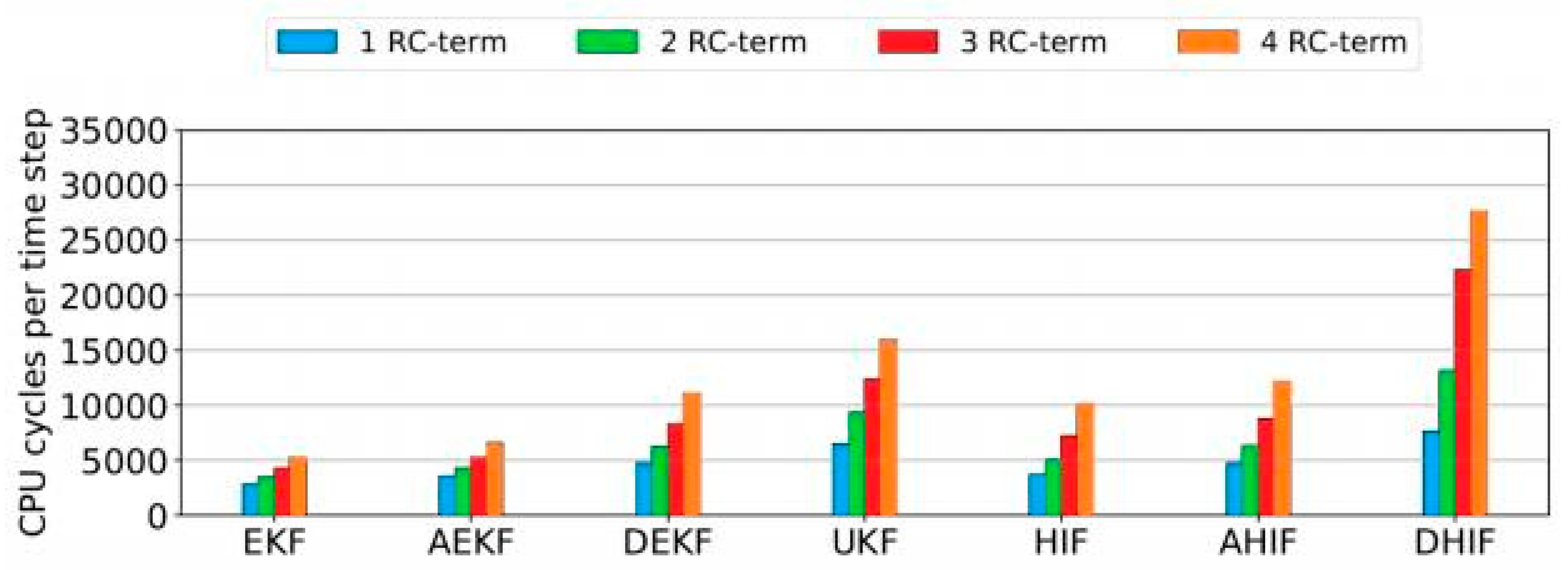

To investigate the relationship between the number of RC-terms in the model and the computation time, all filters were executed on a digital signal processor. The consistent CPU cycle count offered by a DSP allows for precise measurement of computation steps. As computation time in seconds varies across different processor platforms, we measured computation steps instead. These values can be converted to time by dividing by the processor’s frequency if needed.

The DSP compiler was set up to produce optimized code, using the internal compiler in VisualDSP++ without additional adjustments. Among the filters, the extended Kalman filter required the fewest compu- tation cycles, ranging from 2825 cycles with one RC-term to 5278 cycles with four RC-terms. On the DSP, only the size of the matrices matters because the system and the filter’s mathematical structure are fixed. The correlation between the number of RC-terms and computation cycles is nearly linear, as anticipated, due to the matrix dimensions for the filters increasing linearly with more RC-terms. The increase in cycles per RC-term varied from about 700 for the EKF to 6000 for the dual H-infinity filter. In general, H-infinity filters had a steeper increase in cycles than Kalman filters. The adaptive extended Kalman filter recalcu- lates the covariance matrices of measurement and process noise at each time step, unlike the EKF, which has predetermined parameters. Both dual filters run their algorithms twice per time step. H-infinity filters typically require more computation steps due to additional multiplications and inversions.

Figure 3 presents a summary of the CPU cycle counts for the seven filters we tested.

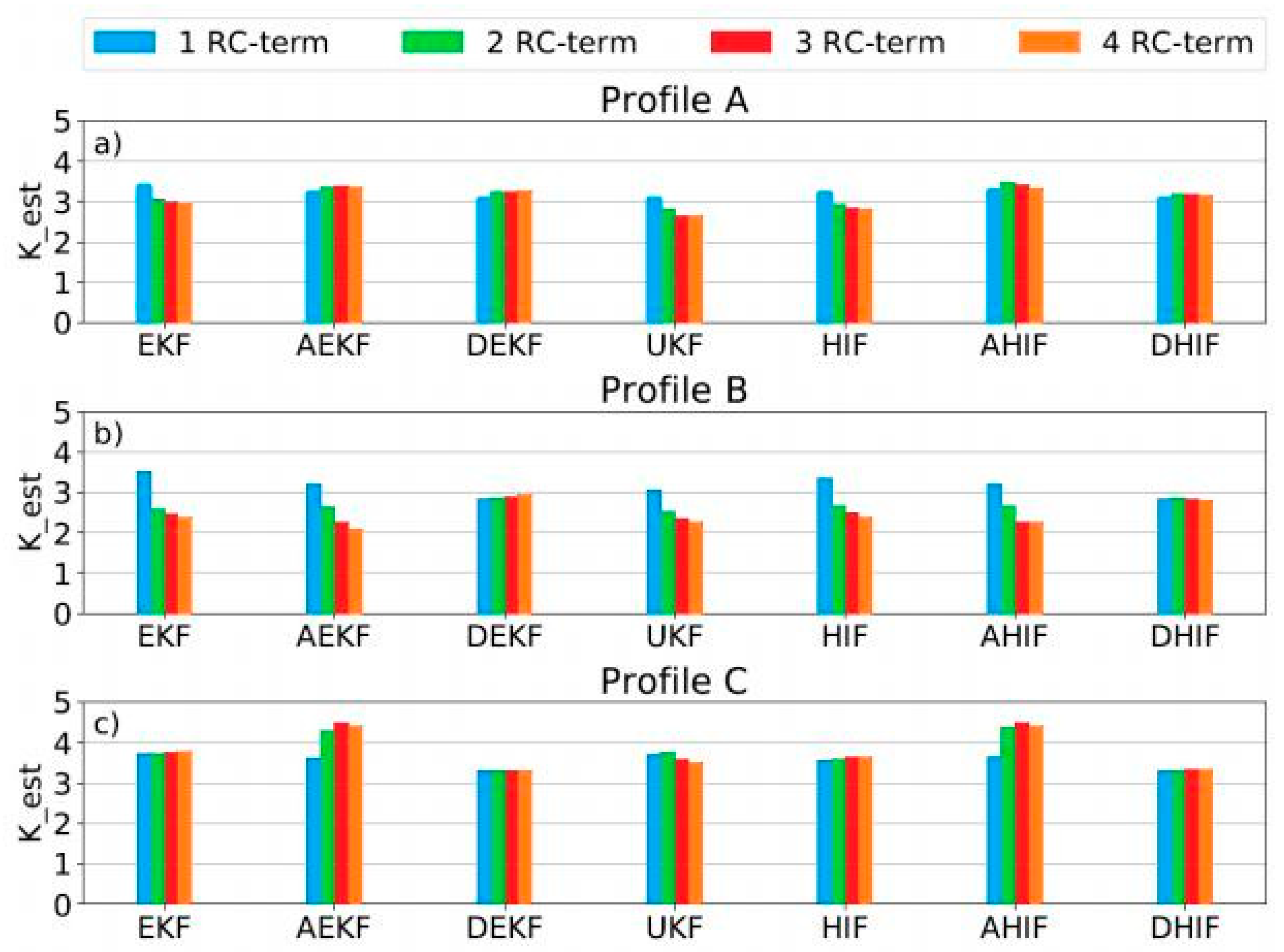

Exploring the link between the number of RC-terms in a battery model and the precision of SOC esti- mation is also crucial. The model by [

13] features four RC-terms. For each filter, across all test profiles, and for each model variant, we computed the parameter Kest from the validation criteria.

The findings, illustrated in

Figure 4, reveal that the extended Kalman filter and the H-infinity filter experience a drop in estimation accuracy for profiles A and B when utilizing more than one RC-term. In contrast, the adaptive filters achieved their best results for profiles A and C with two and three RC-terms, respectively. The adaptive filters with three RC-terms performed notably well in profile C. The unscented Kalman filter displayed a similar pattern to the EKF and HIF in profiles A and B, with a significant decrease in performance when moving from one to two RC-terms. Profile B shows the most considerable variation in scores, with values decreasing for all filters except the dual versions. This contrasts with the findings of [

31], which indicated that additional RC-terms could enhance accuracy under dynamic loads. As batteries heat up during dynamic loads, models failing to emulate this behavior can lead to errors. However, dual filters seem to counteract this issue, thereby maintaining consistent performance in profile B.

Adaptive filters excel under low dynamic loads and can even improve their scores with an increased number of RC-terms. Yet, under dynamic conditions, they struggle as they take time to search for the correct filter parameters, leading to a slow convergence towards the accurate SOC value, and ultimately scoring similarly to their non-adaptive counterparts.

In conclusion, no single filter consistently outperforms the others across all conditions. Compromises must be tailored to each specific situation. The results depicted in

Figure 4 do not support the notion that more RC-terms invariably result in enhanced estimation accuracy. On average, models with two RC-terms tend to yield the best performance.

For our analysis, we compared the Kalman and H-infinity filters using a model with two RC-elements. We evaluated the filters across all five validation criteria, starting with transient behavior and the Ktrans score. The greatest discrepancies occurred at 5 。C, with scores ranging from 2.64 for AEKF to 4.31 for UKF. The UKF’s performance is less affected by the model, which is advantageous at lower temperatures where model inaccuracies are more pronounced, making it the top performer in cold conditions. At room temperature (25 。C), the scores were close, between 4.16 and 4.44, indicating similar transient behaviors among the filters. At a temperature of 40 。C, the UKF led again with a score of 4.42. Overall, the UKF consistently scored highest on average for transient behavior, with H-infinity variations outperforming their Kalman counterparts for this metric.

The temperature analysis for profiles A and B is encapsulated by the Ktemp criterion. For the low- dynamic profile A, all filters scored similarly, around 3.0. However, for profile B, both dual filters scored over 1 point lower than the highest score for K temp, despite nearly topping the chart for profile A.

In the long-term, temperature-dependent profile C, all filters achieved a Kest score above 3.0. Adaptive filters led with scores of 4.3 (Kalman) and 4.37 (H-infinity). They also maxed out at 5.0 for K drift and Kres . In contrast, both dual filters scored the lowest across all criteria, with DEKF scoring 3.31 for Kest , 2.71 for K drift, and 2.28 for Kres . DHIF was slightly better with scores of 3.31, 2.74, and 3.3,respectively.

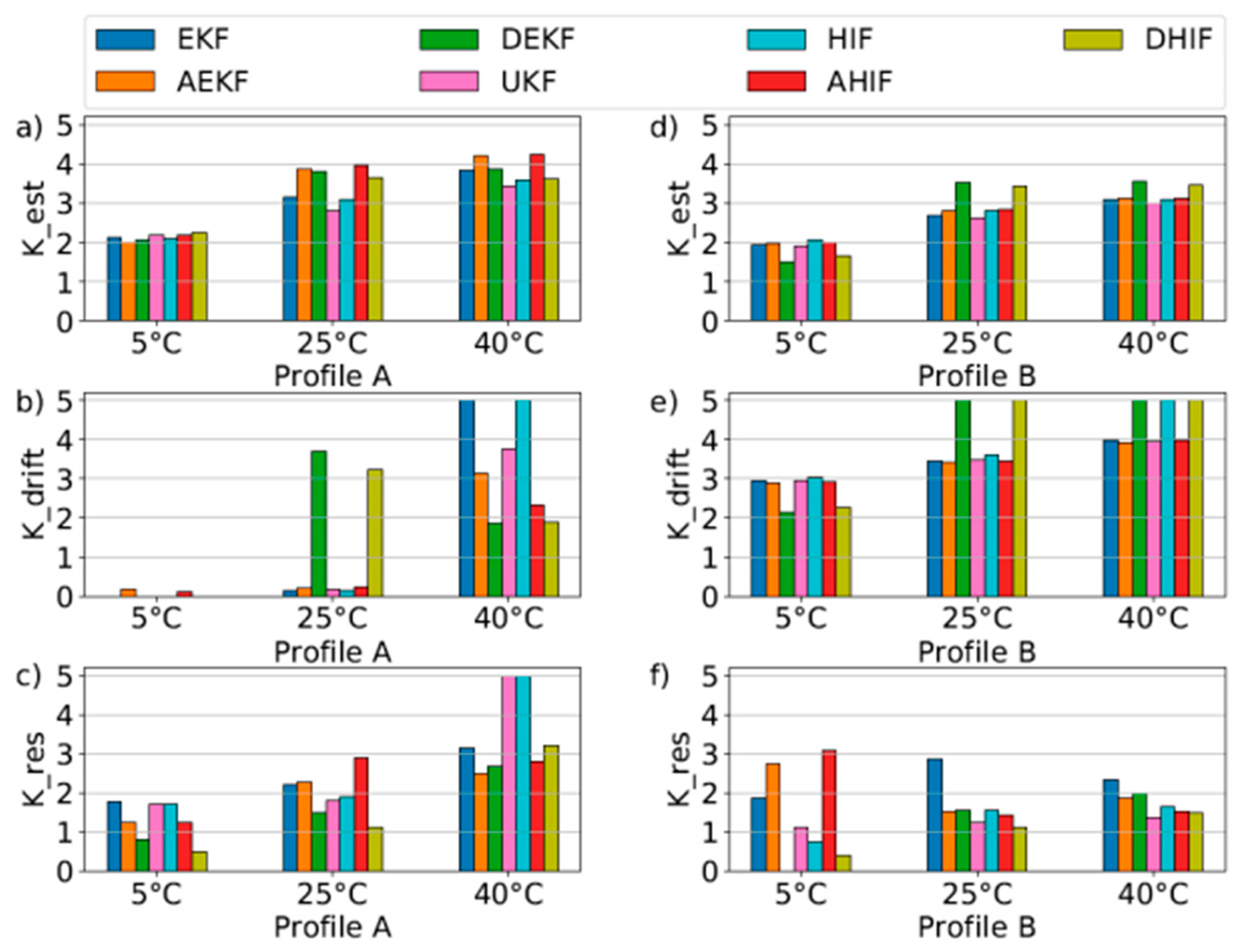

Figure 5 summarizes the other criteria. It shows that filters generally score higher in profile A than in profile B and perform better at higher temperatures. The score differences for various temperatures in profile A range from 0.6 to 1.8, and in profile B from 0.7 to 2.0. At the same temperature, corresponding Kalman and H-infinity filters yield similar results, with differences below 0.27 for profile A and 0.14 for profile B. Notably, the specific type of filter within the Kalman or H-infinity family has a more significant impact on the estimation score than the choice between Kalman or H-infinity filters. The maximum deviation for Kest at 5 。C for profile A is only 0.25, indicating that all filters can estimate SOC with comparable quality for low-dynamic profiles.

However, the drift score K drift presents a different picture, as shown in

Figure 5 b) and e). The filters struggle to match the reference SOC precisely at low temperatures. Model inaccuracies and higher internal resistance values at lower temperatures hinder the filters’ ability to converge swiftly to the correct SOC. For profile A, the type of filter variation again plays a more decisive role than the filter family itself. At 5 。C, adaptive filters score above 0, while dual filters excel at 25 。C. At 40 。C, the standard filter versions perform best. Profile B results are more uniform, with scores increasing alongside temperature. Both dual filters hit the top score of 5.0 at 25 。C and 40 。C. The difference between filters in profile B is minimal, except for EKF and HIF at 40 。C, which have a notable gap of 1.03. H-infinity filters generally score higher in profile B.

Figure 5 c) and f) display the residual charge scores. The results vary significantly across different profiles and temperatures. For profile B, most filters score lower than in profile A. While scores for profile A rise with temperature, this trend does not hold for profile B. The range of scores for profile A spans from 0.49 to 5.0, and for profile B from 0.0 to 3.09. EKF outperforms HIF at every temperature for profile B.

Despite lower scores for EKFin Kest and K drift compared to HIF in profile B across all temperatures, this does not necessarily correlate with residual charge estimation, suggesting that drift behavior and residual charge estimation are independent.

7. Conclusions and Outlook

This paper conducted a comparative analysis of seven filters, including the extended Kalman filter, adaptive extended Kalman filter, dual extended Kalman filter, unscented Kalman filter, H-infinity filter, adaptive H-infinity filter, and dual H-infinity filter. We examined the impact of the battery model on estimation ac- curacy and the computational demand on a digital signal processor. Three test profiles and a standardized validation method were applied to evaluate all filters. Through comparison with a reference implementation and subsequent individual filter tuning, we were able to enhance the filters’ performance for the specific bat- tery cell used. The validation method proved robust as it yielded consistent results across tests. A notable issue, transient behavior, was addressed through parameter adjustments. All filters exhibited low drift scores at temperatures under 40 。C, which aligns with the thermal effects observed during charge and discharge cycles. This phenomenon warrants further investigation and should be incorporated into future modeling efforts.

Overall, no single filter emerged as the clear winner for all scenarios; performance was relatively uni- form across the board. Kalman and H-infinity filters performed similarly, although H-infinity filters showed quicker convergence from incorrect SOC initialization. Considering both estimation accuracy and compu- tational load, the EKF and HIF demonstrated solid performance, making them reliable choices for general applications.

A common trend was the reduced performance of all filters at lower temperatures, likely due to unmod- eled heating effects, suggesting a need for improved model parameter extraction methods. Establishing a standardized measurement setup is essential to ensure not only filter comparison but also measurement reli- ability. While the validation method is broadly applicable, it can be further tailored with additional criteria for specific applications. Experiments with different cells, particularly for automotive use, should extend to temperatures as low as -40 。C, given that sub-zero operations were not covered in this work.

8. Acknowledgments

The research presented herein was carried out as part of the SIMBA project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 963542. The authors wish to extend their heartfelt thanks to the scientific staff at the department, particularly Maximilian Bruch, for his dedication and relentless effort in navigating the challenges associated with cell modeling and method implementation. Special appreciation is also due to Stephan Lux, Dr. Matthias Vetter, and Dr. Nina Kevlishvili for their meticulous and insightful proofreading of this work.

References

- Zhansheng Ning, ZhongweiDeng, Jinwen Li, Hongao Liu, and Wenchao Guo. Co-estimation of state of charge and state of health for 48 v battery system based on cubaturekalman filter and h-infinity. Journal of Energy Storage, 56:106052, 2022.

- Yong Chen, RongboLi, Zhenyu Sun, Li Zhao, and Xiaoguang Guo. Soc estimation of retired lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicle with improved particle filter by h-infinity filter. Energy Reports, 9:1937–1947, 2023.

- Selvaraj Vedhanayaki and Vairavasundaram Indragandhi. Certain investigation and implementation of coulomb counting based unscented kalman filter for state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicle application. International Journal of Thermofluids, 18:100335, 2023.

- R. E. Kalman. A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. Journal of Basic Engineering, 1960; 82, 35–45.

- IS Khalil, JC Doyle, and K Glover. Robust and optimal control. Prentice hall. 1996.

- Zhenggang Chen, Jianxiong Zhou, Fei Zhou, and Shuai Xu. State-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on improved h infinity filter algorithm and its novel equalization method. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021; 290, 125180.

- Zheng Chen, Hongqian Zhao, Xing Shu, Yuanjian Zhang, Jiangwei Shen, and Yonggang Liu. Synthetic state of charge estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on long short-term memory network modeling and adaptive h-infinity filter. Energy, 2021; 228, 120630.

- Tiancheng Ouyang, Peihang Xu, Jingxian Chen, Zixiang Su, Guicong Huang, and Nan Chen. A novel state of charge estimation method for lithium-ion batteries based on bias compensation. Energy, 226:120348, 2021.

- Chao Wang, Xin Zhang, Xiang Yun, and Xingming Fan. A novel hybrid machine learning coulomb counting technique for state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Energy Storage, 63:107081, 2023.

- Cheng Lin, Hao Mu, Rui Xiong, and Weixiang Shen. A novel multi-model probability battery state of charge estimation approach for electric vehicles using h-infinity algorithm. Applied Energy, 166:76–83, 2016.

- Christian Campestrini, Max F. Horsche, Ilya Zilberman, Thomas Heil, Thomas Zimmermann, and Andreas Jossen. Validation and benchmark methods for battery management system functionalities: State of charge estimation algorithms. Journal of Energy Storage, 7:38–51, 2016.

- Xin Lai, Yuejiu Zheng, and Tao Sun. A comparative study of different equivalent circuit models for estimating state-of-charge of lithium-ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta, 2018; 259, 566–577.

- Maximilian Bruch, Lluis Millet, Julia Kowal, and Matthias Vetter. Novel method for the parameterization of a reliable equivalent circuit model for the precise simulation of a battery cell’s electric behavior. Journal of Power Sources, 2021; 490, 229513.

- Christian Campestrini. Practical feasibility of kalman filters for the state estimation of lithium-ion batteries, 2018.

- Zhiliang Zhang, Xiang Cheng, Zhou-Yu Lu, and Dong-Jie Gu. Soc estimation of lithium-ion battery pack considering balancing current. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, 33(3):2216–2226, March 2018.

- M. Berecibar, I. Gandiaga, I. Villarreal, N. Omar, J. Van Mierlo, and P. Van den Bossche. Critical review of state of health estimation methods of li-ion batteries for real applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 56:572–587, 2016.

- Holger C. Hesse, Michael Schimpe, Daniel Kucevic, and Andreas Jossen. Lithium-ion battery storage for the grid—a review of stationary battery storage system design tailored for applications in modern power grids. Energies, 10(12), 2017.

- C. et al. Zhang L., Papavassiliou. Intelligent computing for extended kalman filtering soc algorithm of lithium-ion battery. Wireless Pers Commun, 2018; 102.

- M.A. Hannan, M.S.H. M.A. Hannan, M.S.H. Lipu, A. Hussain, and A. Mohamed. A review of lithium-ion battery state of charge estimation and management system in electric vehicle applications: Challenges and recommendations. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2017; 78, 834–854. [Google Scholar]

- Quanqing Yu, Rui Xiong, and Cheng Lin. Online estimation of state-of-charge based on the h infinity and unscented kalman filters for lithium ion batteries. Energy Procedia, 105:2791–2796, 2017. 8th International Conference on Applied Energy, ICAE2016, 8-11 October 2016, Beijing, China.

- D. Andrea. Battery Management Systems for Large Lithium-ion Battery Packs. EBL-Schweitzer. Artech House, 2010.

- Jeffrey, B. Straubel et al. Method and apparatus for mounting, cooling, connecting and protecting batteries, 2007. US2007009787 (A1).

- Keith Glover and John C. Doyle. State-space formulae for all stabilizing controllers that satisfy an h-infinity-norm bound and relations to relations to risk sensitivity. Systems and Control Letters, 11(3):167–172, 1988.

- Keith Zhou Kemin; Doyle, John C.; Glover. Robust and Optimal Control. Paperback; Prentice Hall, 1996.

- Rui Xiong, Quanqing Yu, Le Yi Wang, and Cheng Lin. A novel method to obtain the open circuit voltage for the state of charge of lithium ion batteries in electric vehicles by using h infinity filter. Applied Energy, 207:346–353, 2017. Transfor- mative Innovations for a Sustainable Future – Part II.

- D. Feng Y. Chen, D. Huang and K. Wei. An h-infinity filter based approach for battery soc estimation with performance analysis. IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), pages 1613–1618, 2015.

- Phil Lapsley; Jeff Bier; Amit Shoham; Edward A. Lee. DSP Processor Fundamentals: Architectures and Features. Wiley- IEEE Press, 1997.

- Ahmad Rahmoun, Moritz Loske, and Argo Rosin. Determination of the impedance of lithium-ion batteries using methods of digital signal processing. Energy Procedia, 46:204–213, 2014. 8th International Renewable Energy Storage Conference and Exhibition (IRES 2013).

- Steven W. Smith. The Scientist and Engineer’s Guide to Digital Signal Processing. 1997.

- Samsung SDI. Datasheet INR18650-29E, 2012.

- Christian Campestrini, Thomas Heil, Stephan Kosch, and Andreas Jossen. A comparative study and review of different kalman filters by applying an enhanced validation method. Journal of Energy Storage, 8:142–159, 2016.

- Saeed Sepasi, Reza Ghorbani, and Bor Yann Liaw. Improved extended kalman filter for state of charge estimation of battery pack. Journal of Power Sources, 255:368–376, 2014.

- Georg Walder, Christian Campestrini, Markus Lienkamp, and Andreas Jossen. Adaptive state and parameter estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on a dual linear kalman filter computer engineering, 03 2014.

- Rui Xiong, Fengchun Sun, Xianzhi Gong, and Hongwen He. Adaptive state of charge estimator for lithium-ion cells series battery pack in electric vehicles. Journal of Power Sources, 242:699–713, 2013.

- Christian Campestrini. Practical feasibility of kalman filters for the state estimation of lithium-ion batteries. 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).