1. Introduction

The success of endodontic treatment depends on multiple factors (1), among which the clinician's awareness of dental anatomy and the root canal system holds a special place (2-4), According to a systematic review, the diversity in the root canal system of second mandibular molars is very high (5) Notably, as an anatomic variation, C-shaped canals occur frequently in these teeth, with a worldwide prevalence of 13.9%. This figure rises dramatically in some Asian populations, where up to 44% of second mandibular molars exhibit this particular canal configuration (6). Research suggests that the development of C-shaped canals is influenced by a combination of genetic and ethnic factors. Additionally, the adaptation of teeth to more compact dental arches may contribute to root fusion and the subsequent formation of C-shaped canal morphology (7).

The unique morphology of C-shaped root canals presents significant challenges in endodontic procedures, including difficulties in properly cleaning, shaping, and filling the canal system. As a result, teeth with C-shaped canals have a higher likelihood of unsuccessful outcomes following root canal therapy. Therefore accurately identifying C-shaped canal morphology is important (8). Today, the variations in the root canal system of teeth are accurately examined using CBCT images (4). Although periapical radiographs are still widely used and play a significant role in pre-treatment evaluations (3), CBCT provides three-dimensional and high-quality images to clinicians, eliminating the limitations of conventional radiographs, such as distortion and superimposition of bone and various parts of the tooth (4). However, CBCT imaging imposes a much higher dose of radiation and additional costs on the patient, limiting the application of this imaging method in routine clinical treatments (9). Furthermore, diagnosing the presence or absence of C-shaped canals, commonly seen in second mandibular molars, using two-dimensional imaging methods not only is time consuming but also lacks accuracy. In a study by Zhang et al., two dentists were asked to determine the presence or absence of C-shaped canals in panoramic radiographs. The diagnosis results of the dentists were then compared with each other and with CBCT evaluations as the correct standard. According to the results of this study, the agreement of the dentists' opinions with the correct standard was 0.413 and 0.301, and with each other was 0.460 (10).

2. Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning in Endodontics

McCarthy and colleagues first introduced the concept of artificial intelligence (AI) in 1965 (11). AI, a branch of computer science, focuses on creating intelligent entities, typically in software form (12). Machine learning, a subset of AI, enables systems to learn tasks without predefined rules by training on data, gradually improving accuracy through error correction, similar to how a child learns to recognize images (13). Deep learning, a more advanced subfield, involves learning complex patterns and hierarchies, often through Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), which consist of interconnected layers of neurons. Depending on the number of hidden layers, these networks can be shallow or deep. In medical and dental sciences, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), a popular ANN type, process digital signals like images and are well-suited for classification, detection, and segmentation tasks (14).

Deep learning models have been applied in various aspects of endodontic, including diagnosis of treatment necessity, working length determination, detection of root fractures, assessment of periapical lesions and investigation of root canal anatomy (4, 15-22). While most studies utilize radiographic images, the use of photographic images in AI-based dental diagnostics remains limited (23). Photographic diagnosis offers advantages such as lower cost, absence of radiation exposure, and safety for all patients, including pregnant individuals.

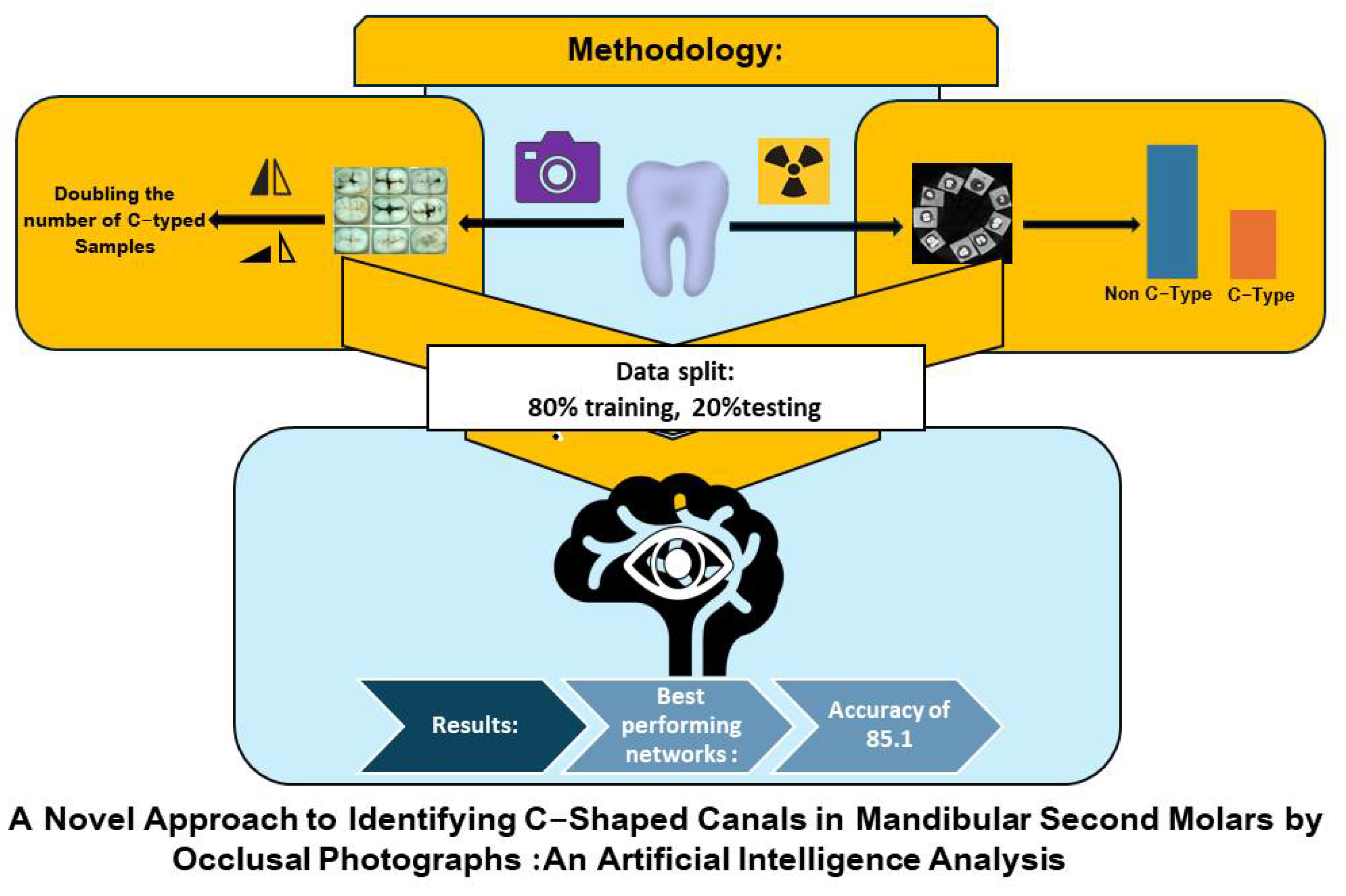

This study aims to evaluate the relationship between the clinical crown appearance of mandibular second molars and the presence of C-shaped canals using a deep learning model trained on intraoral photographs. The model's performance will be compared against CBCT evaluations as the gold standard.

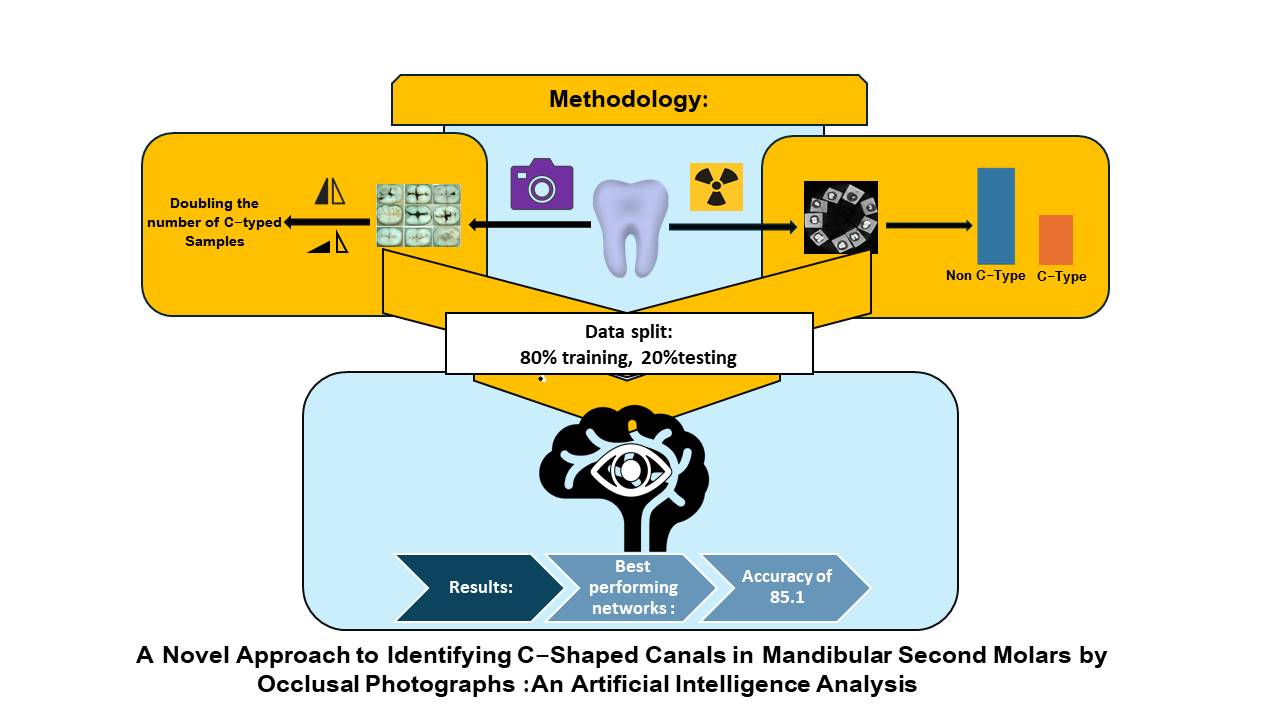

3. Methodology

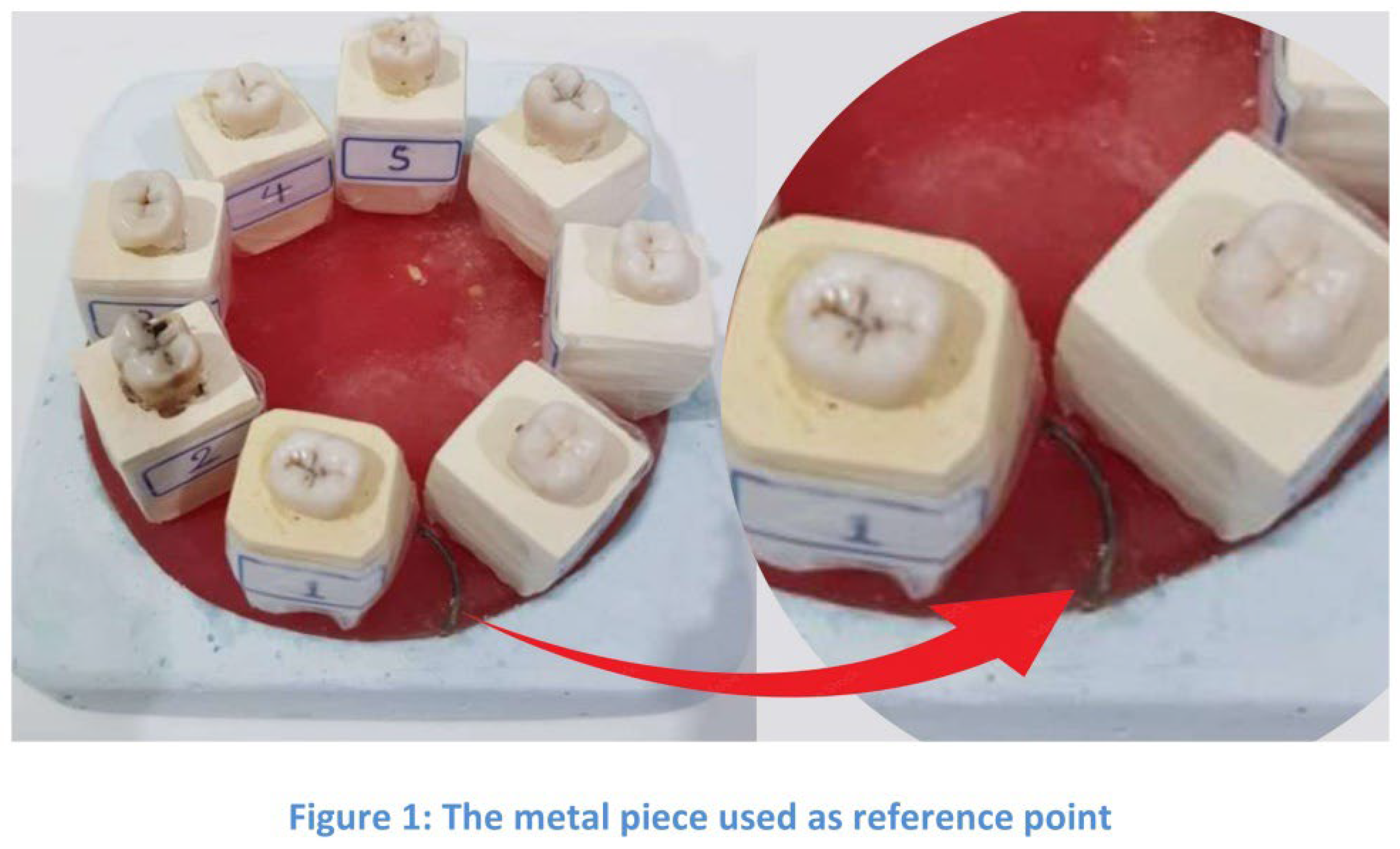

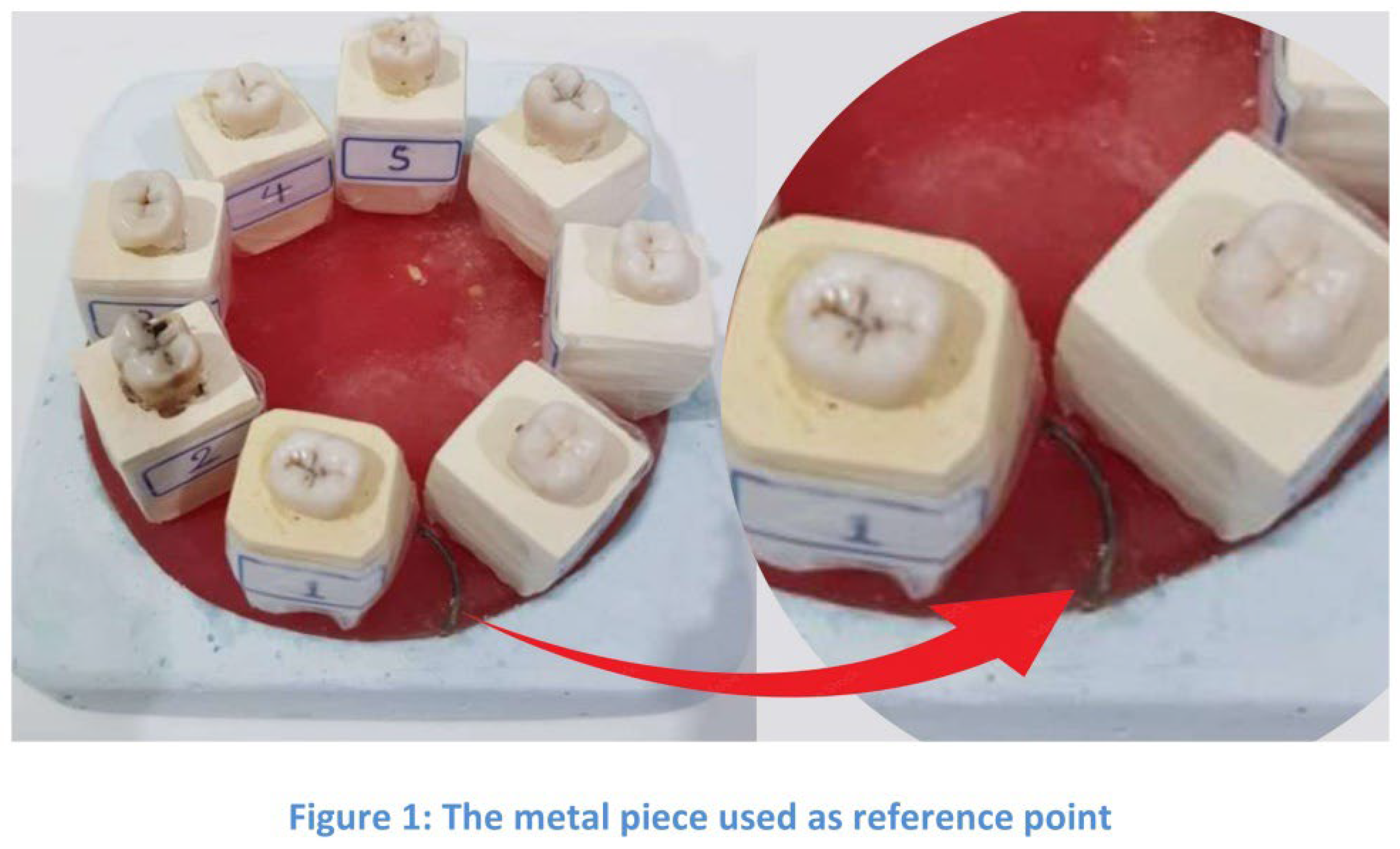

This cross-sectional study collected 231 extracted mandibular second molars that were lost due to periodontal disease, caries or other conditions from an Iranian population. The extracted teeth were divided into two groups: 116 teeth with relatively healthy crowns and 115 teeth with minor decay or structural defects, to the extent that the decay did not involve more than 25% of the crown tissue. Based on CDC guideline (24) to prevent cross-sectional contamination, and to avoid significant surface alterations the samples were soaked in 10% formalin solution for two weeks and kept in tap water afterwards. For better resolution, apical one third of all teeth were covered with red dental wax in a spherical shape in order to be mounted in to rectangular cubes of 1:1 plaster –Stone. The samples were then trimmed similar to each other and labeled numerically. Photographs of the occlusal surfaces were taken using an Ez shot HD wireless oral camera positioned 10 mm away from the surface. If the initial image was not clear, the camera position was adjusted by up to 5 mm to improve clarity. The teeth were then arranged in a custom-made board in groups of 8 and 7, with their lingual surfaces facing the center of the board. A metal piece was used as a reference point for sample identifications. In each CBCT shot, the samples were arranged so that the tooth with the lowest numbered sample faced the concave part of the metallic piece (Figure 1). CBCT images were captured using the Carestream Dental model 9600 cs device s were, all standardized by Radiographic exposure setting with a tube voltage of: 60 kVp, mAs of: 6.2, and FOV of: 5×10 cm. the teeth were then scanned at 0.5-mm interval thickness and observed in axial and coronal sections.

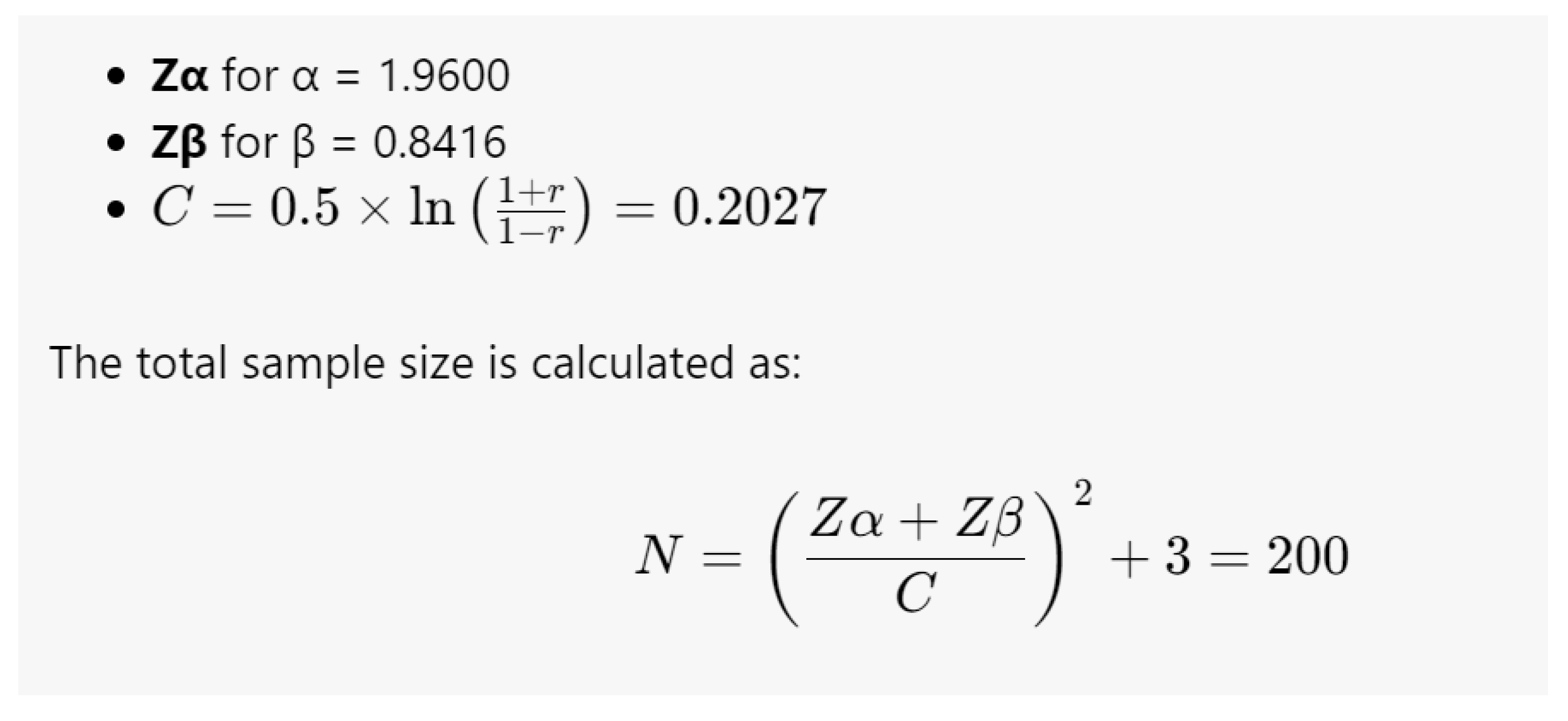

3.1. Sample Size Calculation Method.

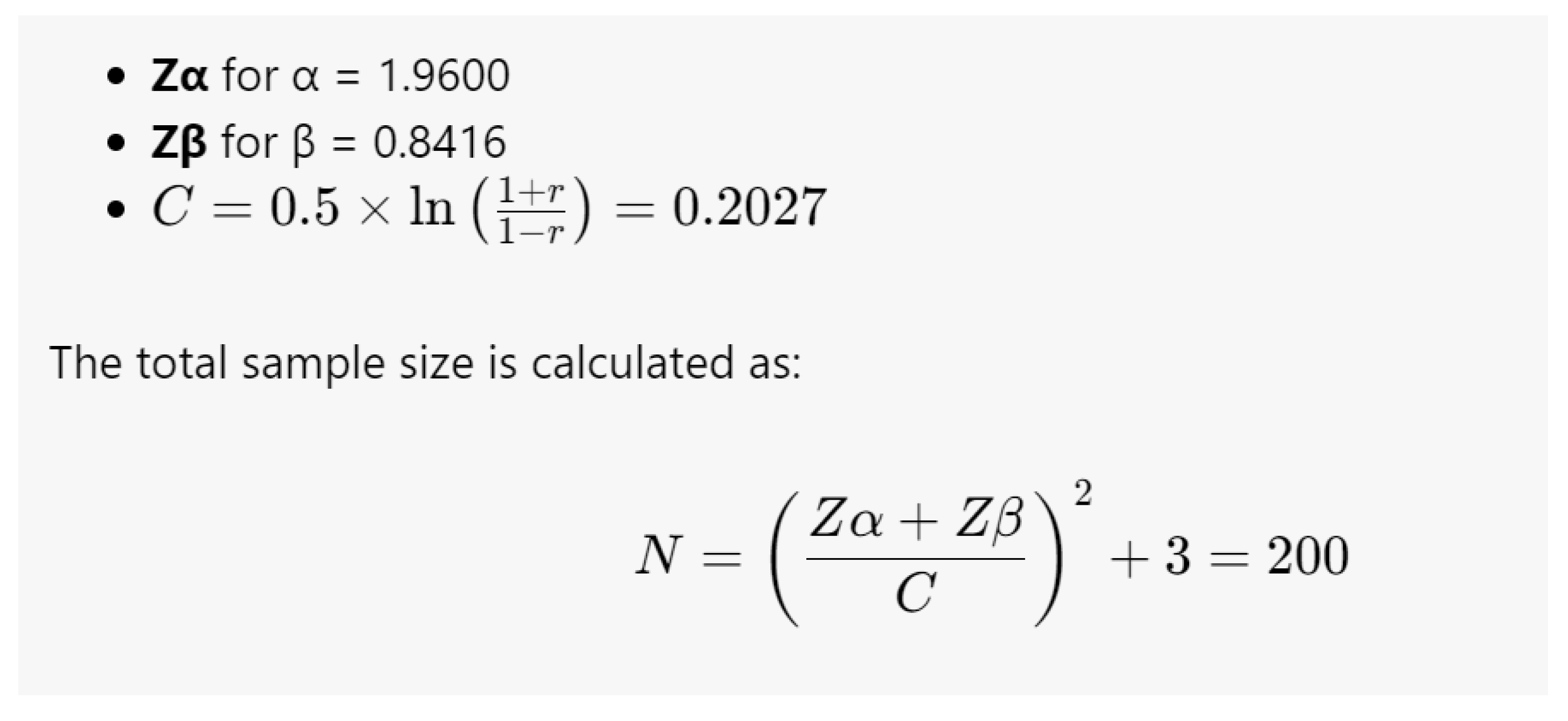

For this study, the sample size was calculated based on a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.2 between two types of images, considering a power of 0.8 and a Type I error of 0.05 as follows:

The total sample size is calculated as:

A minimum sample size of 200 was calculated, and in this study, a total of 231 second molars were collected.

3.2. Radiographic Data Extraction

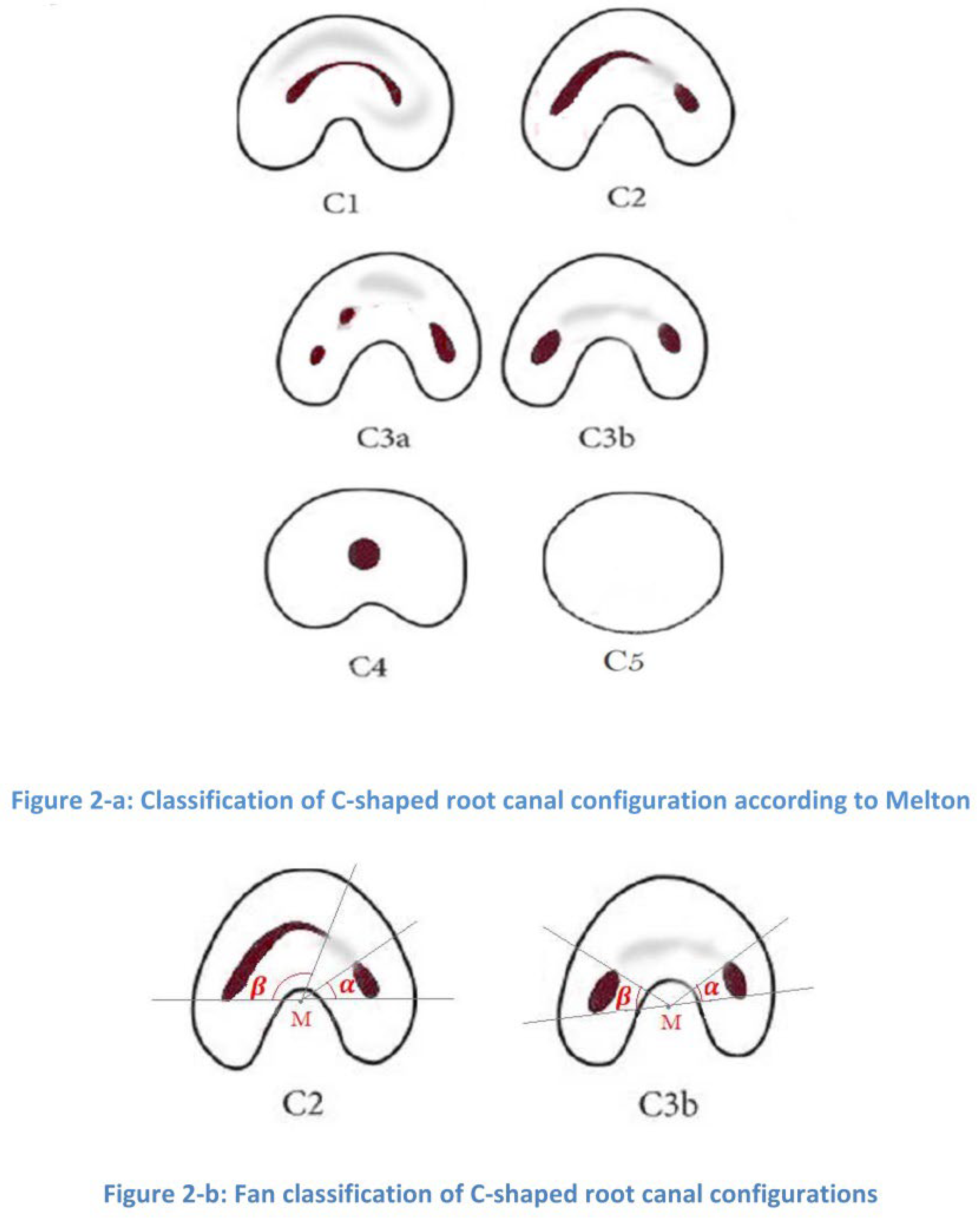

In our study, the mandibular second molar root canal morphology was classified into two patterns: (1) C-shaped canals and (2) non-C-shaped canals.

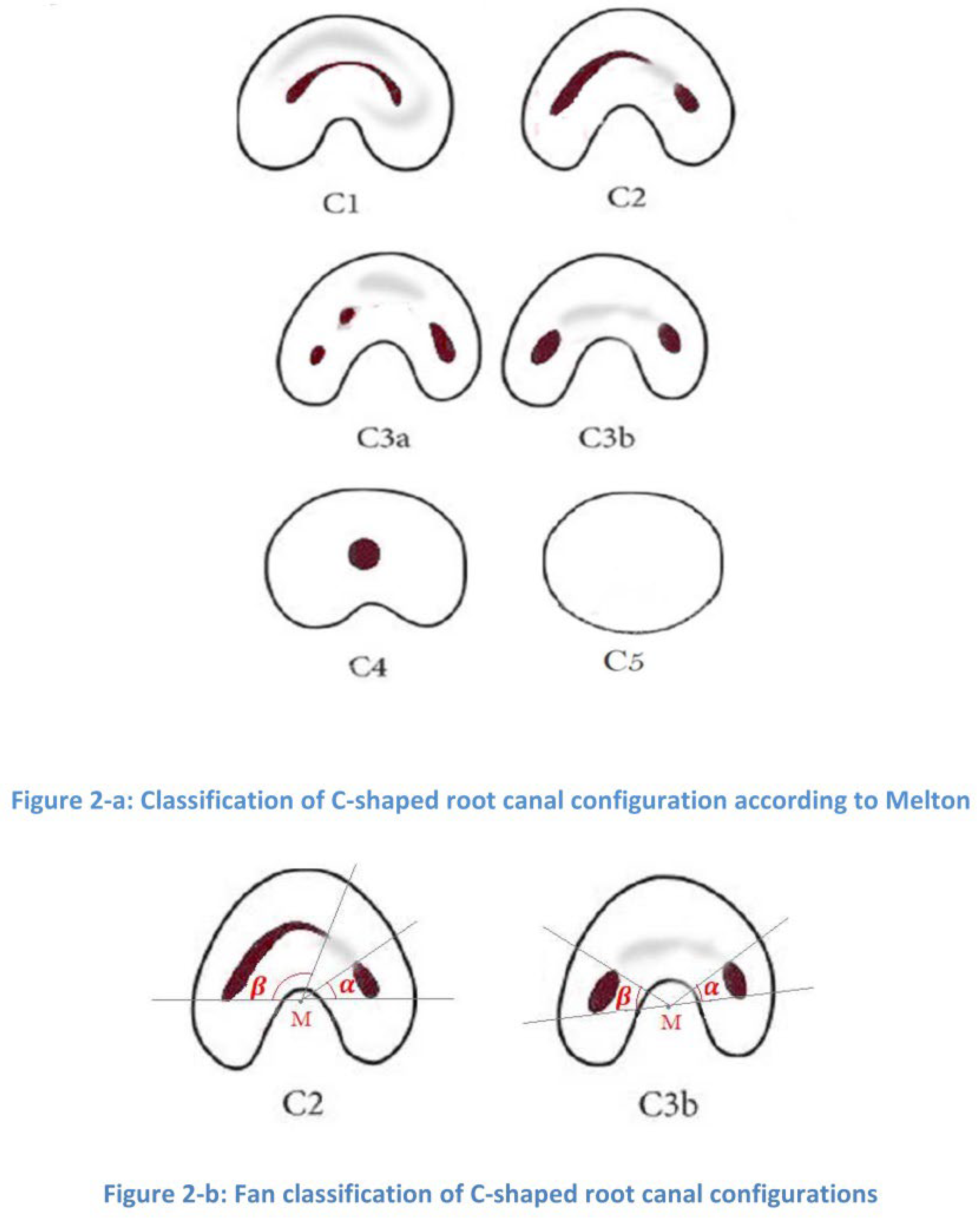

The C-shaped pattern is characterized by a single root with a deep groove that opens on the buccal or lingual surface (25, 26) we used both Fan et all Radiographic classification Of c- shaped root morphology (27) and Melton’s classification of c shaped canals based on their cross-sectional shape (28) for identifying mandibular second molars with c shaped root canals (Figure 2a).

The pattern of C-shaped canals, on the axial section, could have different morphologies at different sections as follows:

C1 - A continuous C-shaped outline with no separation.

C2 - A semicolon shape, where dentine separates the main C-shaped canal.

C3 - Two or more discrete round or oval canals.

C4 - A single round or oval canal.

C5 - No canal, which might occur due to calcification and is usually seen near the apex.

According to Fan et al., for a mandibular second molar to have a C-shaped canal system, at least one cross-sectional view of the canals in a fused root should display a configuration that falls within the C1, C2, C3, or C4 categories. In the C2 pattern, both angles α and β are equal to or greater than 60 degrees, while in the C3 pattern, both angles are less than 60 degrees (26,27) (Figure 2b). Data extraction was performed by a senior Endodontic resident (A.M.) under the supervision of two board-certified endodontists with over 10 years of experience (H.K. and E.K.). Challenging cases were discussed until a consensus was reached.

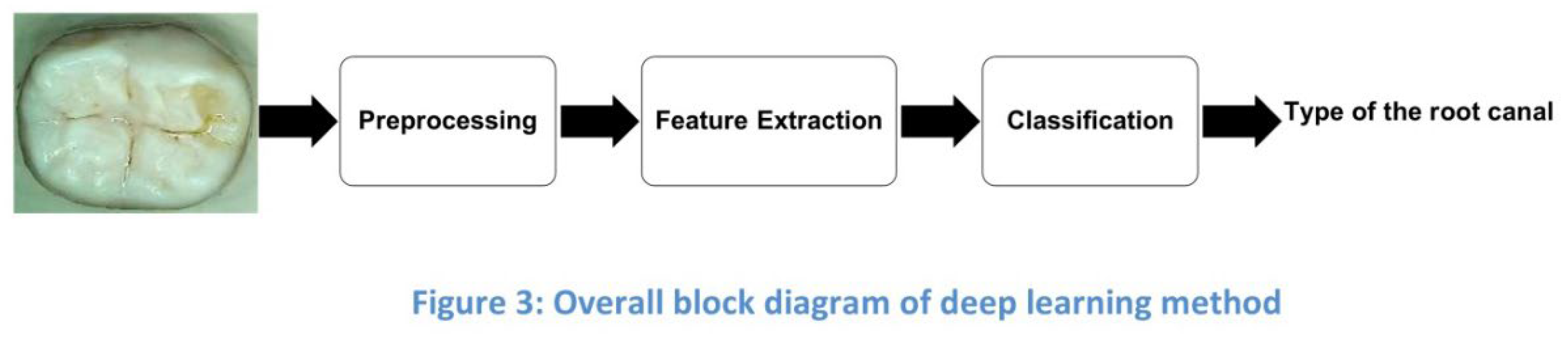

3.4. AI Programming for Classification of C-Shaped and Non-C-Shaped Root Canals

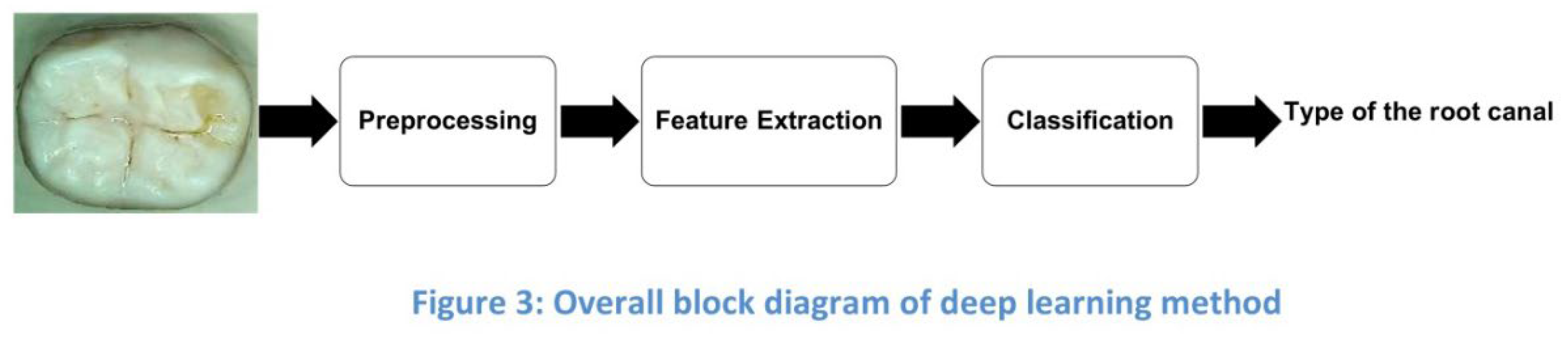

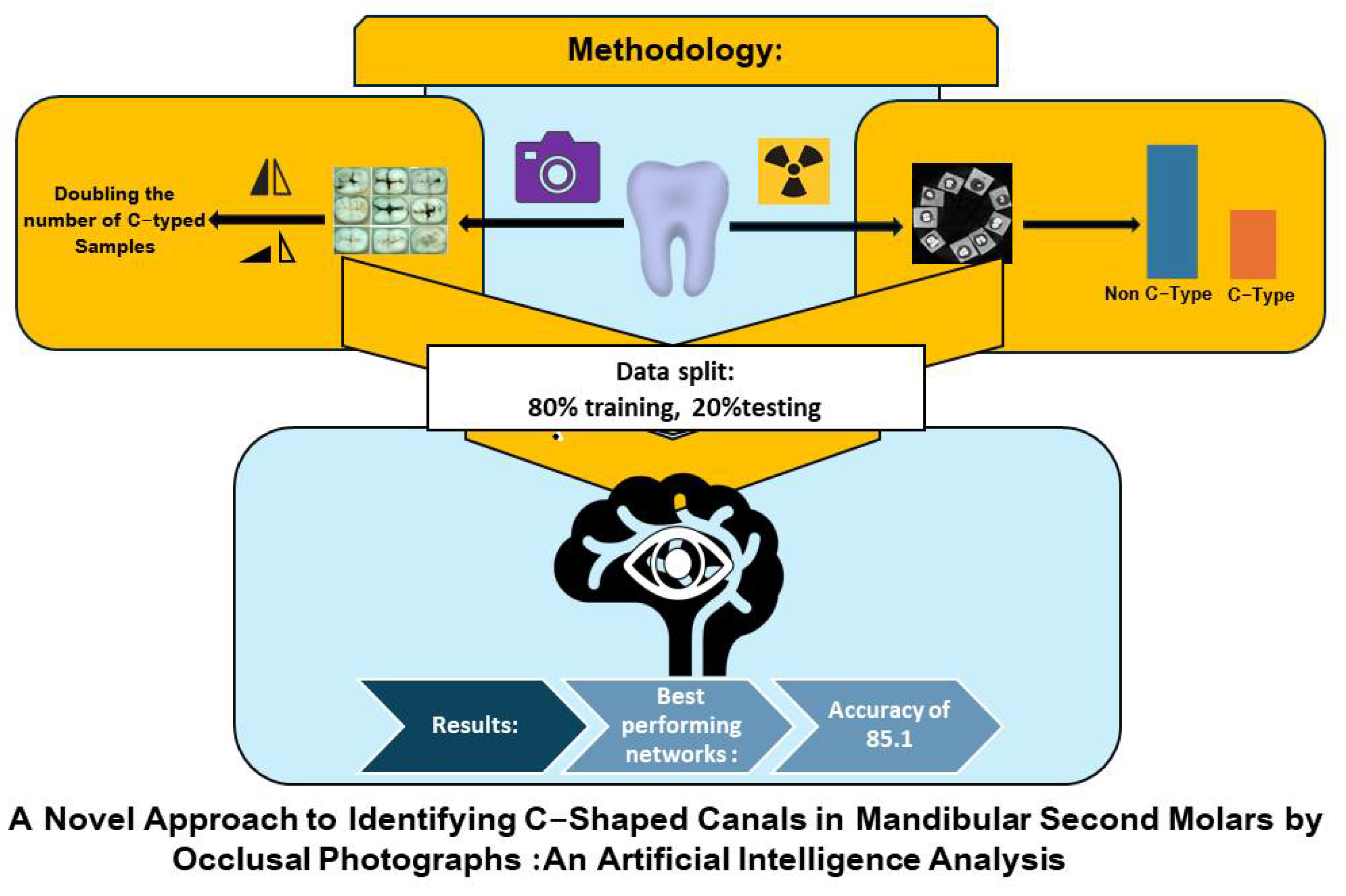

Figure 3 displays the overall block diagram of the deep learning method, which includes three main parts: preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification. We will further investigate its components.

3.5. Dataset and Preprocessing

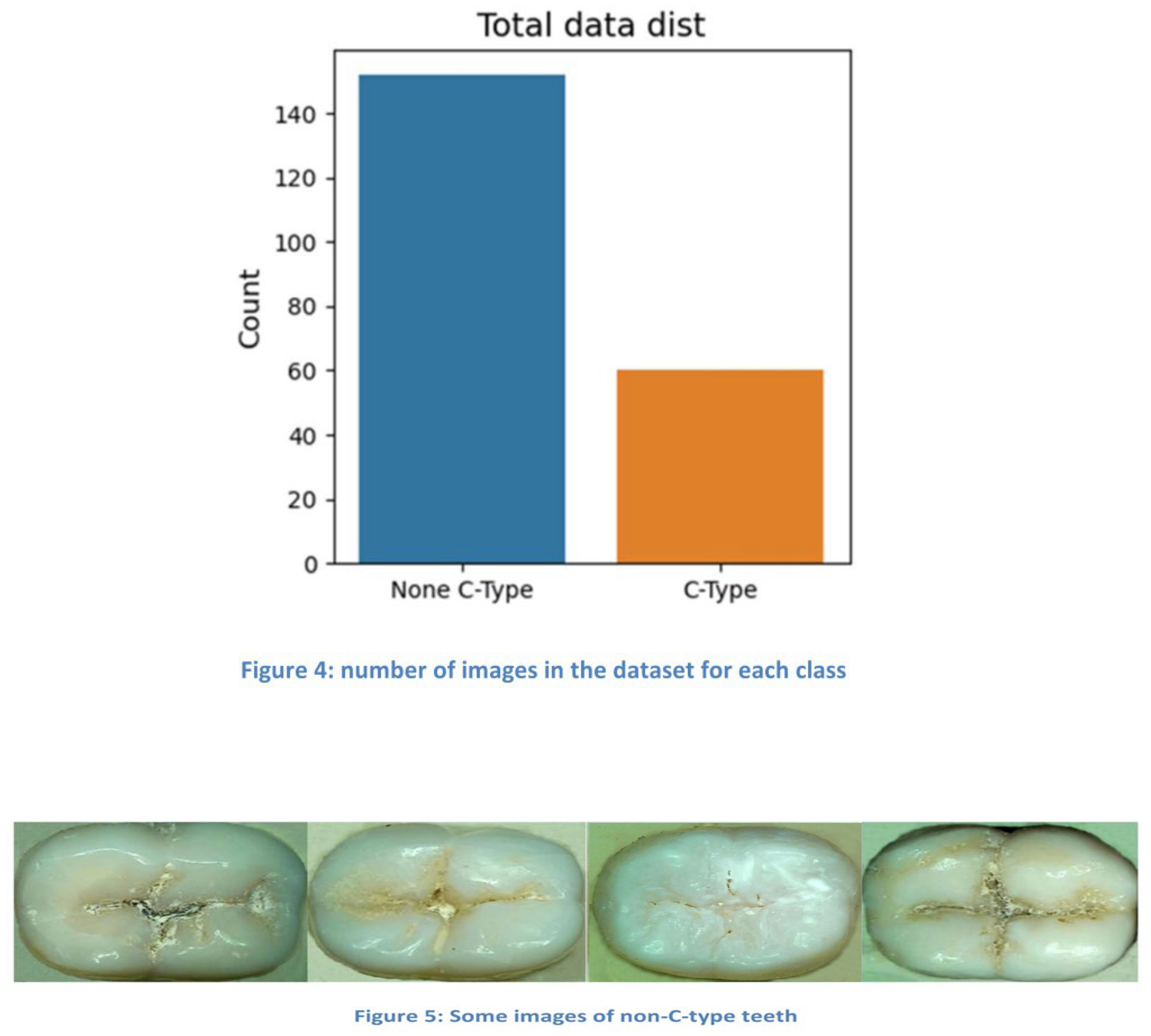

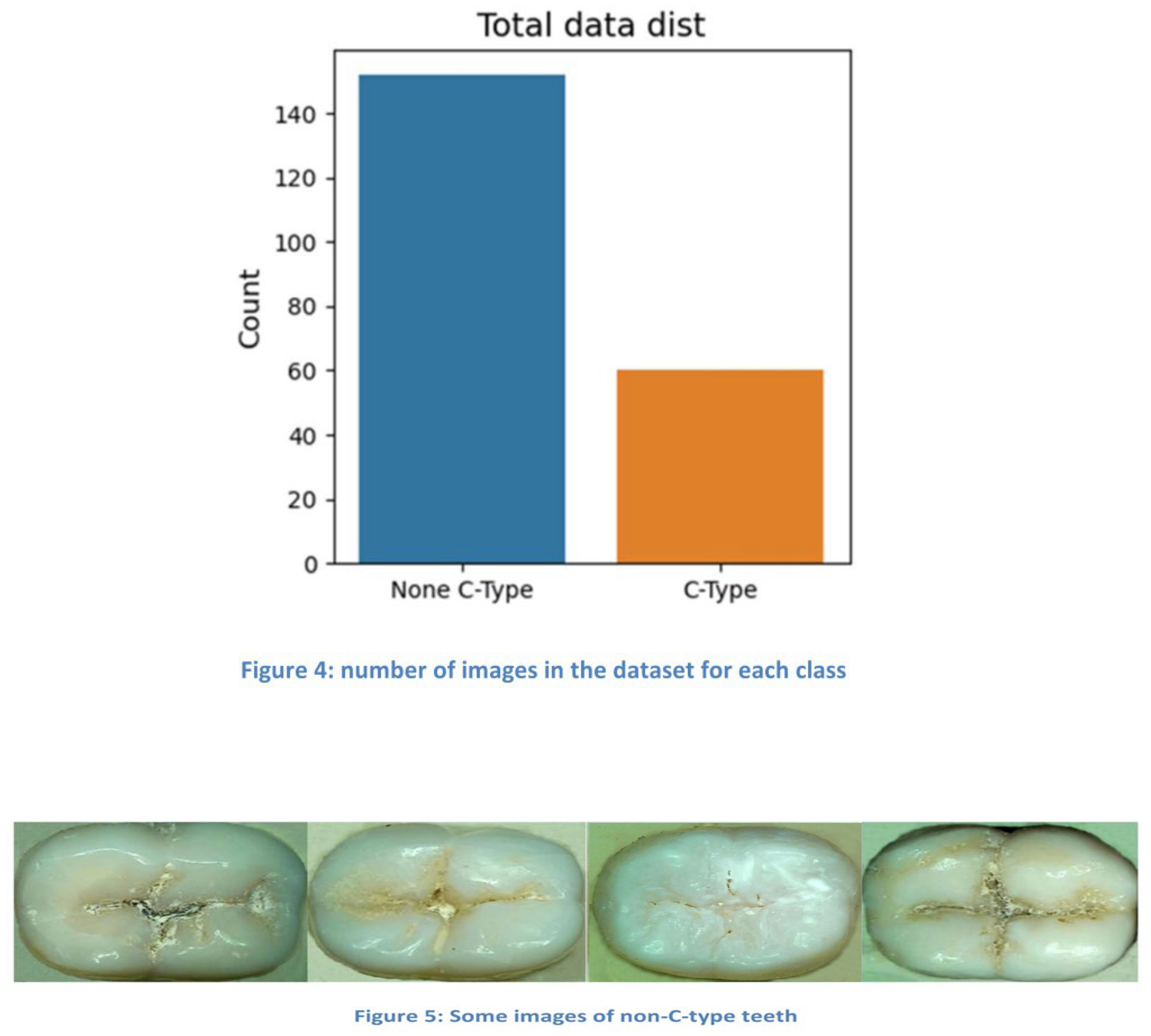

For AI programming, the study utilized a dataset of 212 images of second mandibular molars (19 excluded due to poor image quality and missing data before processing). The final dataset comprised 60 images of C-shaped root canals and 152 images of non-C-shaped root canals. Images were manually preprocessed by:

Removing excess backgrounds

Standardizing backgrounds

Rescaling to 300x300 pixels in most samples

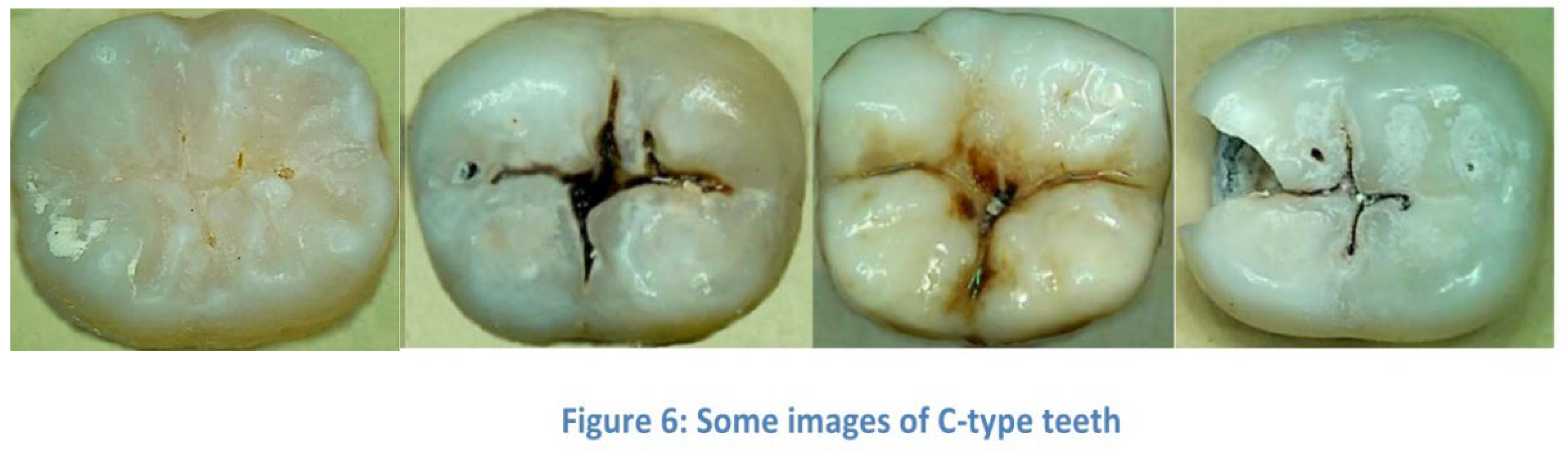

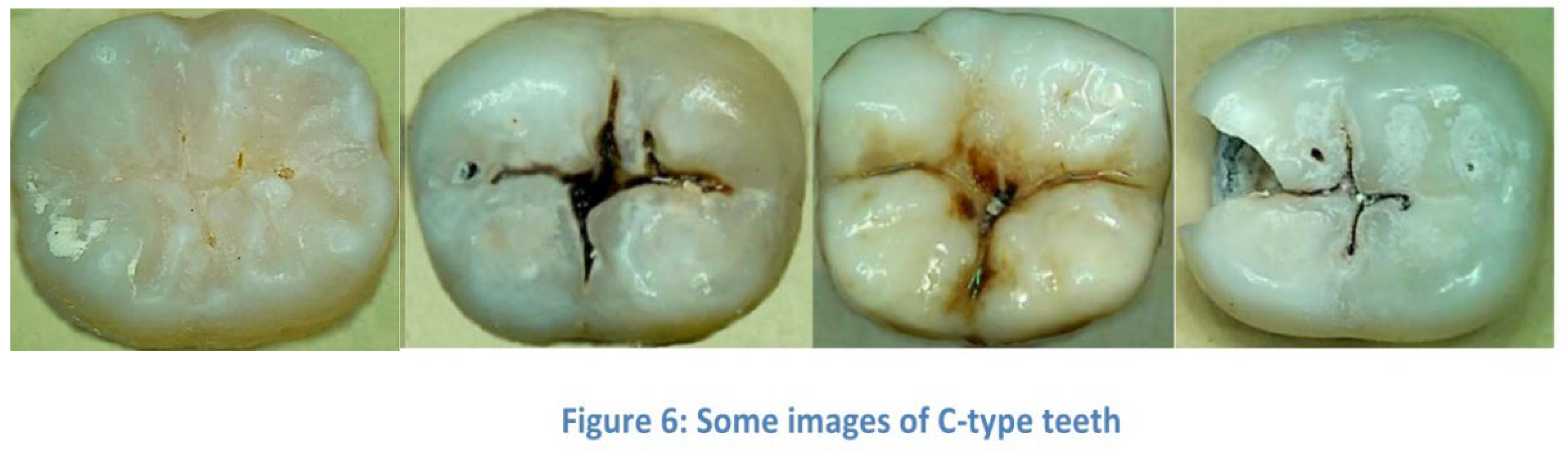

To address class imbalance, data augmentation techniques such as rotation and flipping were employed, effectively doubling the number of C-shaped canal samples to match the non-C-shaped group. This augmentation expanded the dataset and improved model generalization. Figure 4 shows the number of images in each class, while Figure 5 and Figure 6 displays sample images of C-Type and Non-C-Type teeth.

3.6. Feature Extraction and Transfer Learning

The classification task aimed to categorize images into C-Type or Non C-Type using deep learning methods. Due to the challenge of manual feature extraction from dental images, deep learning networks were employed. To address the issue of limited data, transfer learning was applied using pre-trained networks (ResNet50, ResNet101, VGG19, ResNet152, and EfficientNetB1/B3/B5) on ImageNet datasets. ConvNext networks were initially tested but showed suboptimal performance, leading to their exclusion from further analysis.

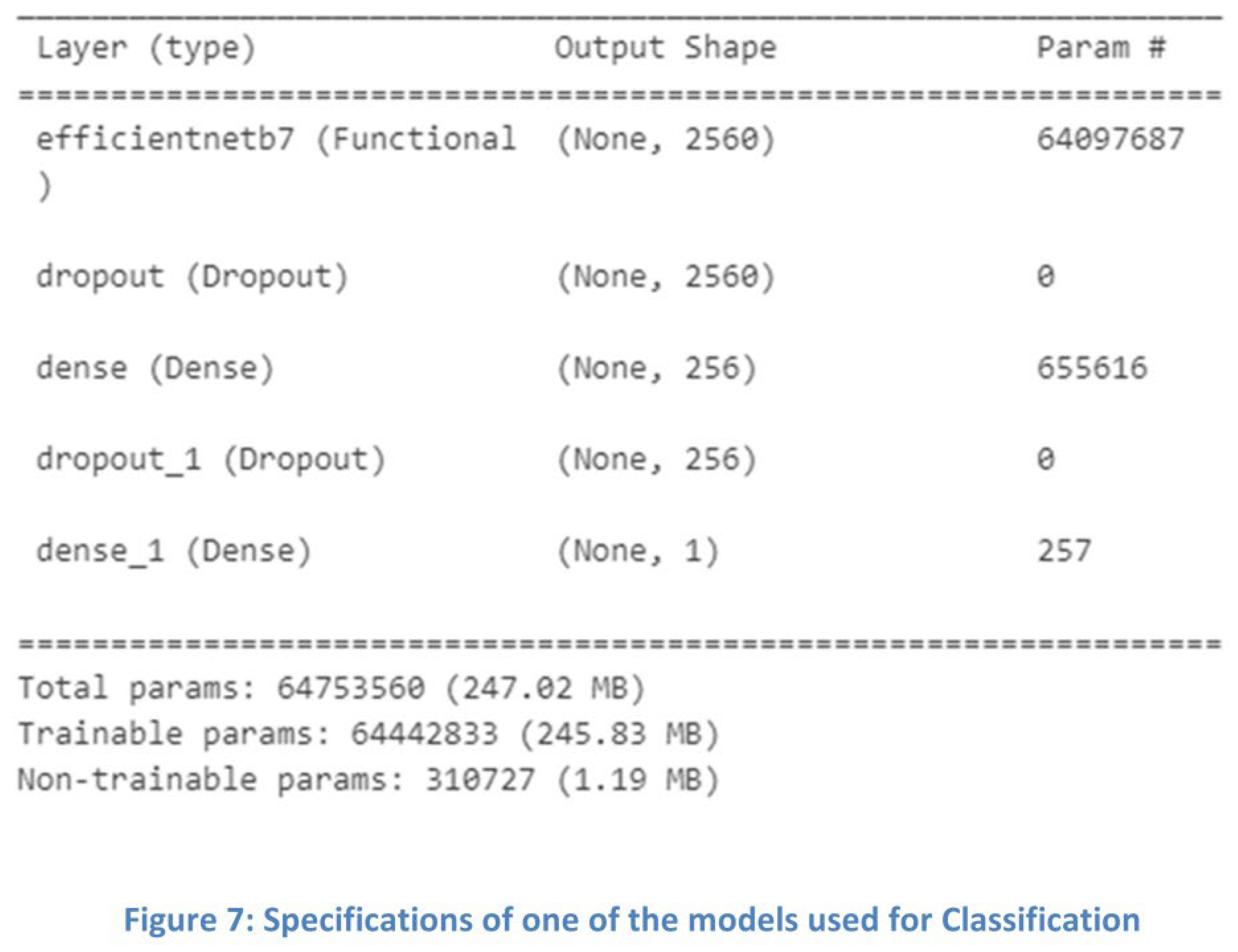

3.7. Classification

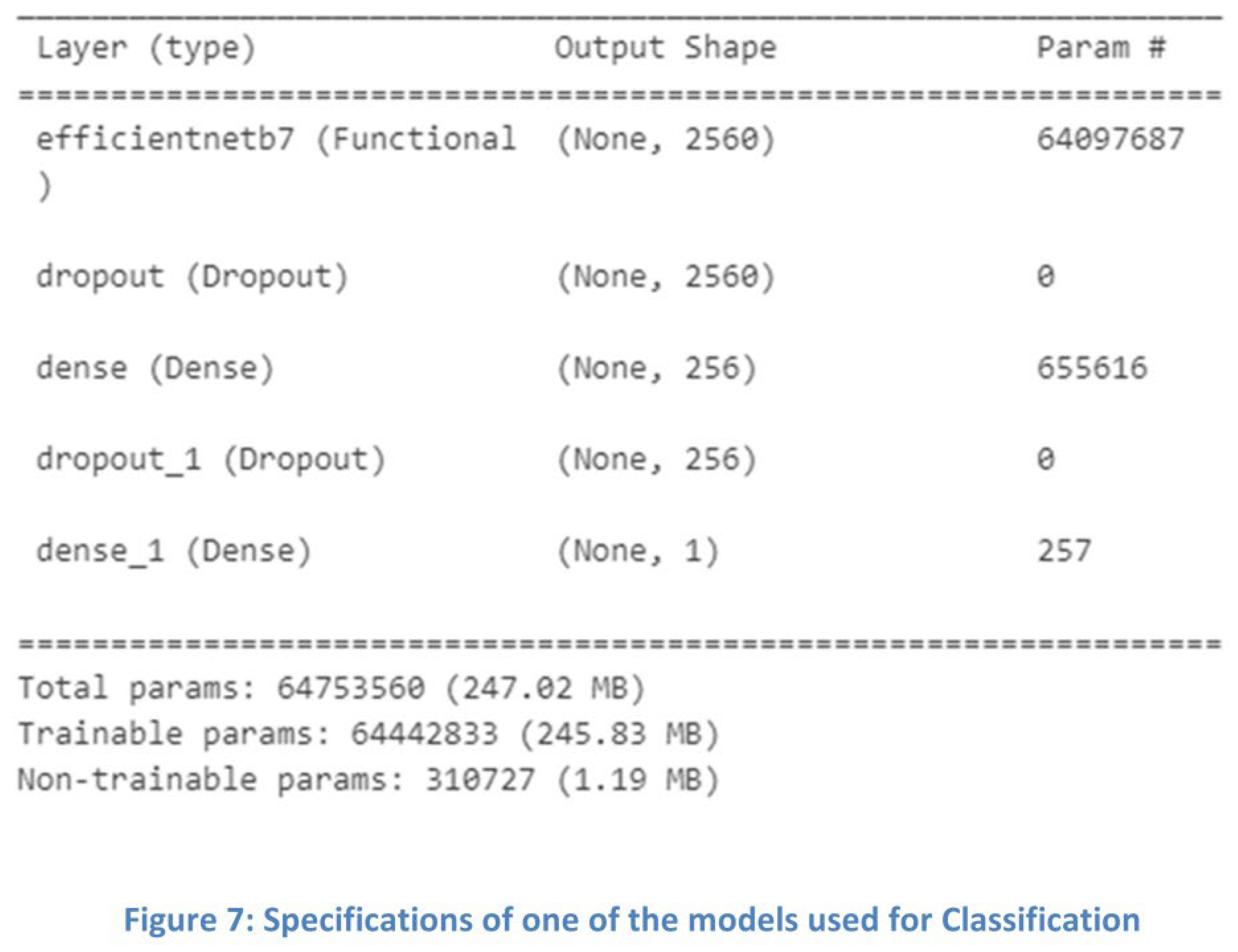

Various classification methods can be used, such as KNN, SVM, Naive Bayes, and neural networks. Here, we have used a fully connected neural network. The specifications of one of the models that yielded the best results are shown in Figure 7.

3.8. Implementation

Programming: Python with NumPy, SciKitLearn, TensorFlow, and Keras libraries

Hardware: Colab platform with Tesla T4 GPU (16GB memory)

Data split: 80% training, 20% testing

Training parameters: 150 epochs, batch size of 16

For implementing this model, deep networks VGG19, ResNet50, ResNet101, and EfficientNetB1, B3, B5 were used. The data was split into 20% for testing and 80% for training, and the images of the C-Type were augmented to equalize the number of images in the classes. Transfer learning models were utilized, leveraging pre-trained weights from ImageNet. Each network was trained for 150 epochs, with batch sizes of 8, 16, and 32 tested; a batch size of 16 yielded the best results across all networks and was used consistently.

3.9. Evaluation Metrics

Performance was evaluated using accuracy and a confusion matrix. The confusion matrix provides insights into model performance by breaking down prediction results into True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN), offering a more detailed performance analysis than accuracy alone. Additional metrics derived from the confusion matrix include precision and recall, from which the F1-score (F-measure) can be calculated. The formulas are given below:

4. Results

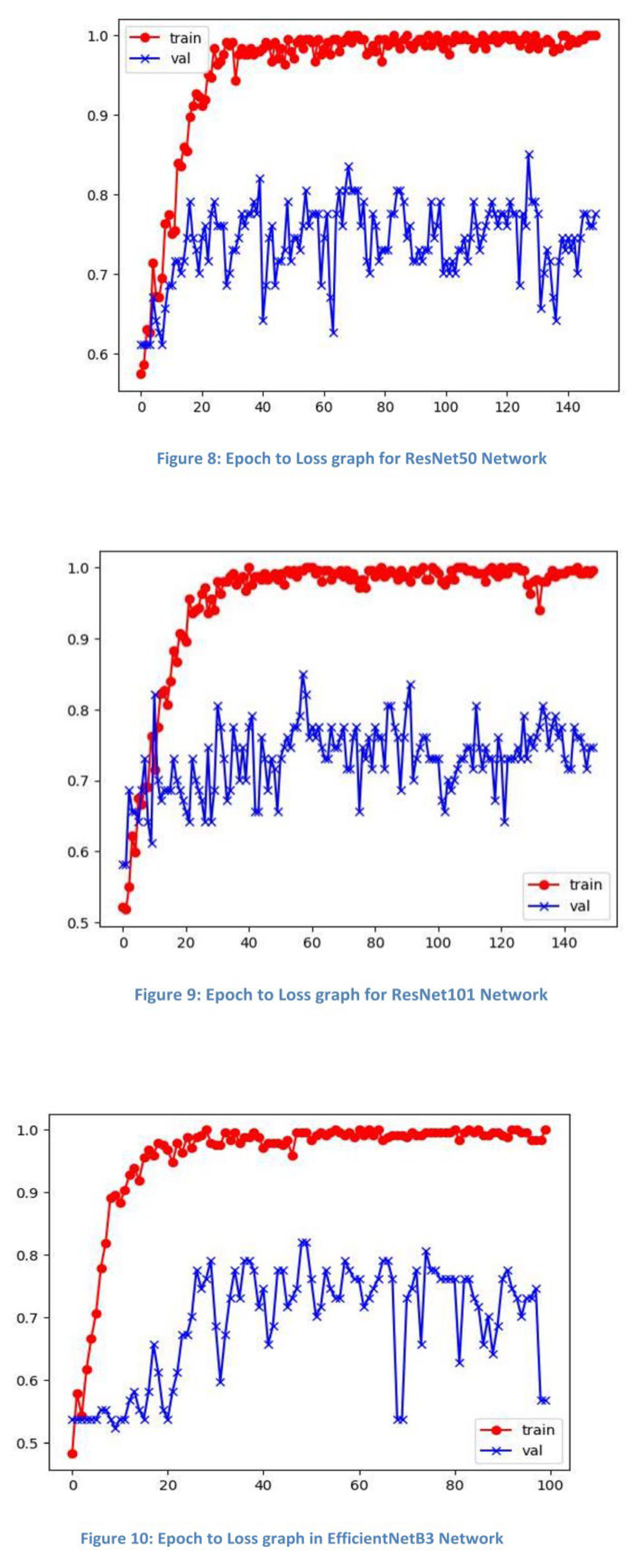

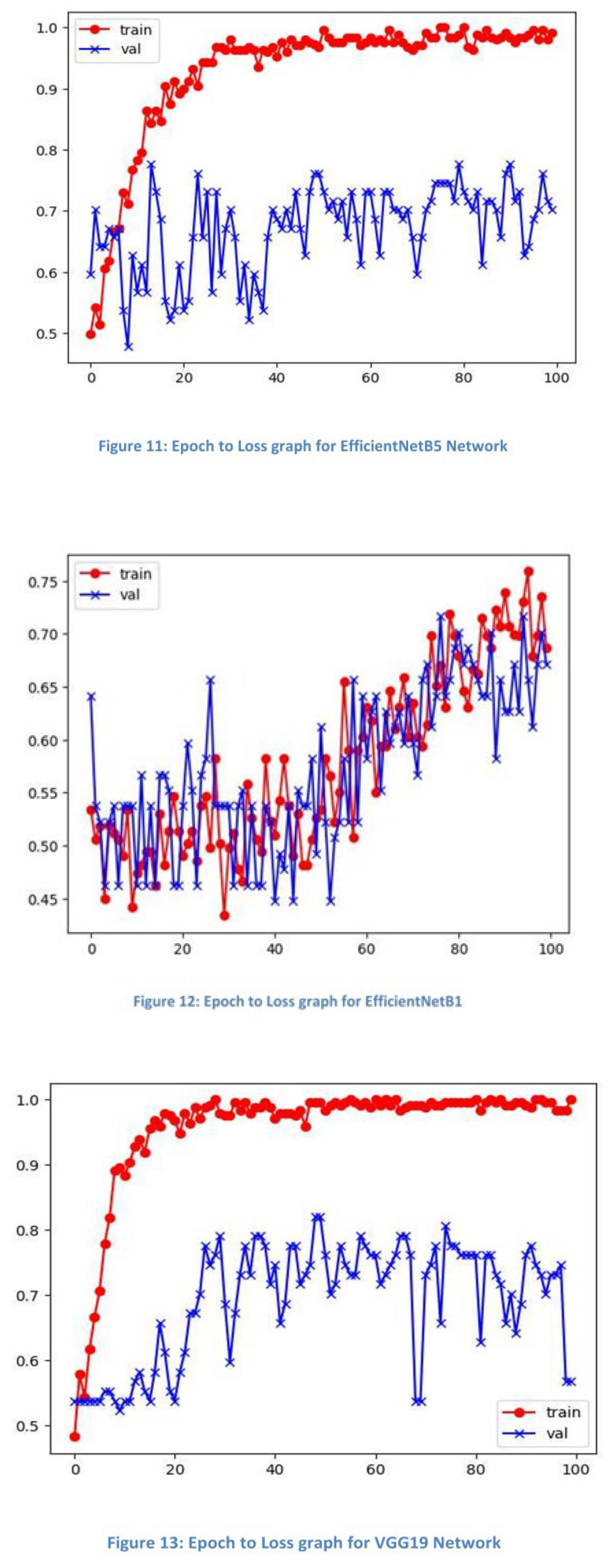

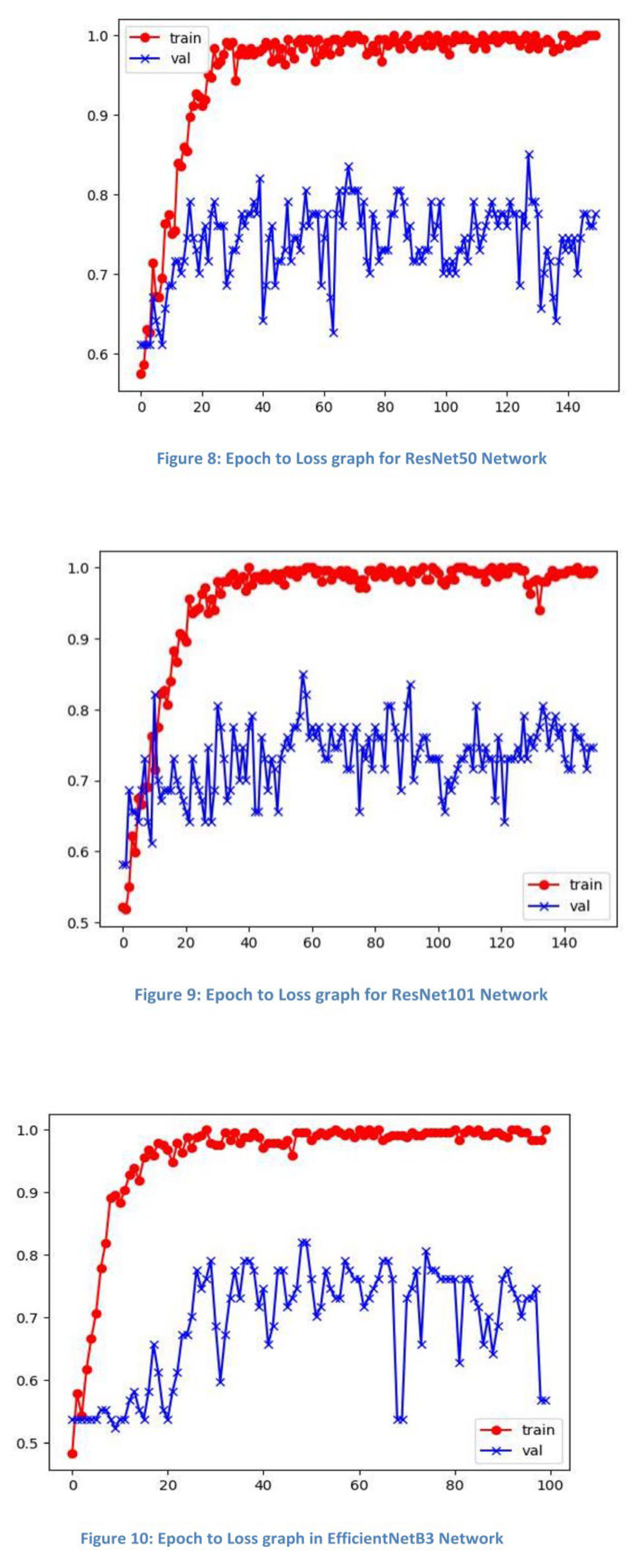

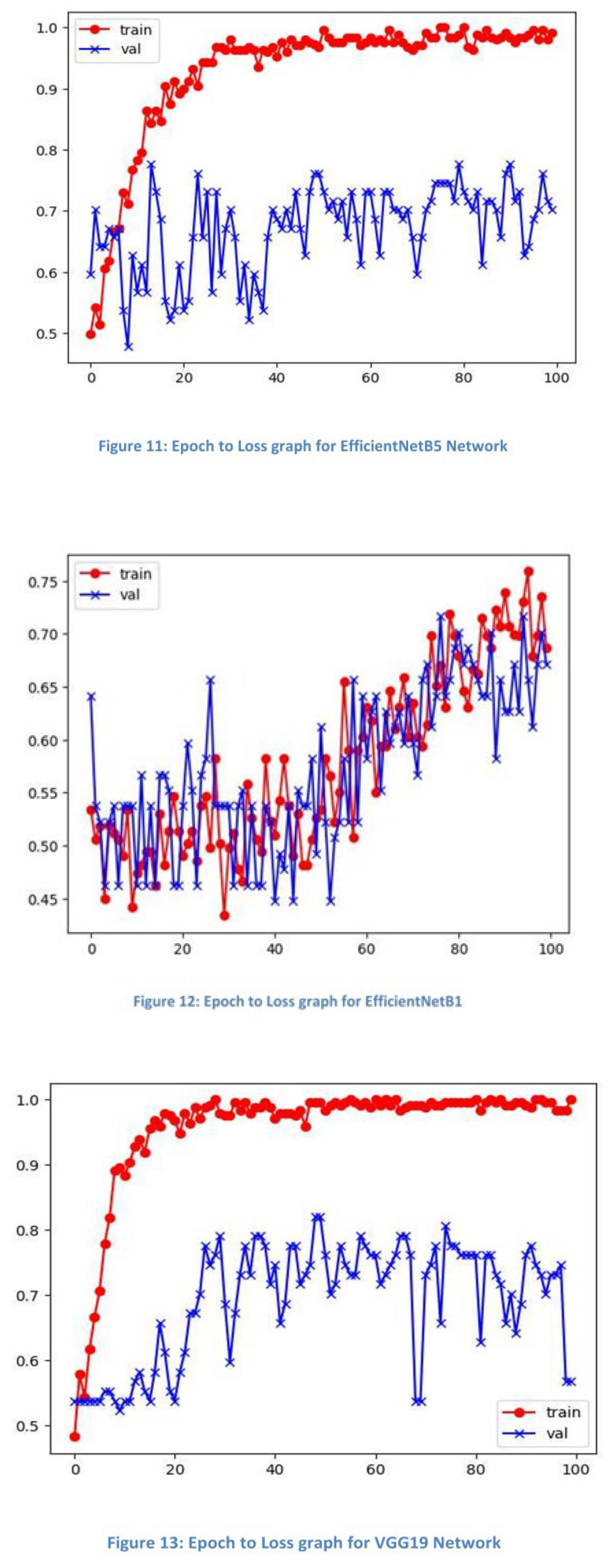

ResNet101 and ResNet50 networks achieved the best performance, with 85.1% accuracy in distinguishing dental canal types. The effectiveness of ResNet networks is attributed to their skip connections, which help mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, allowing better adaptation to this specific classification task.

The obtained results are presented in

Table 1, and

epoch vs. loss graphs for several models are shown in Figures 8-13.

4. Discussion

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in dentistry is rapidly expanding, revolutionizing various aspects of dental care and diagnosis. However, the use of photographic images for training AI models in this field remains relatively unexplored [

3]. While most AI applications in dentistry rely on radiographic images, a few notable exceptions have emerged, demonstrating the potential of photographic-based AI diagnostics. For instance, researchers have developed AI models for diagnosing occlusal caries lesions in posterior permanent teeth using color dental photographs (29). Similarly, an AI system capable of identifying gingivitis from intraoral photographs has been created (30). These studies showcase the versatility of photographic-based AI in assessing both hard tissue anomalies and soft tissue conditions.

Despite these advancements, there remains a significant gap in current research concerning the use of photographic images for AI-assisted analysis in endodontics, particularly in the identification of complex root canal anatomies such as C-shaped canals. One of the most frequent anatomical variations of second mandibular molar is c- shaped canals (7) that are characterized by the presence of isthmi, or narrow connections, between the individual root canals. This results in the formation of a canal system that resembles the shape of the letter "C"(26, 31).

Panoramic radiography can assist in recognizing and diagnosing C-shaped root canal systems and is considered a common approach for identifying C-shaped canals in mandibular second molars. Radicular fusion or proximity is a characteristic feature of C-shaped canal systems which can be seen in this modality, but nonfused root appearances should also be considered suspicious [23, 33].

Identifying C-shaped canals through conventional two-dimensional imaging techniques such as panoramics presents some challenges due to the overlapping of structures in the resulting images. The detection of certain C-shaped canals is further complicated by the density of trabecular bone, which can obscure the canal's morphology (34).

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) offers a significant advancement over traditional 2-dimensional (2D) radiographic techniques, enabling clinicians to capture and manipulate three-dimensional images of specific structures or regions of interest, effectively addressing the limitations of conventional 2D imaging methods. CBCT allows for evaluation of the root canal configuration (C1-C5) at different root levels (coronal, middle, apical) (35). Yet as mentioned earlier it imposes a much higher dose of radiation and additional costs on the patient, limiting the application of this imaging method in routine clinical treatments (2).

The ability to identify root canal morphology without exposing patients to radiation has been a compelling area of investigation. This study aims to address this possibility, exploring the potential of AI-analyzed intraoral photographs in identifying these complex anatomical variations.

Our findings demonstrate the successful development of an AI model capable of distinguishing C-shaped canals in mandibular second molars with an accuracy of 85.1%, using ResNet50 & 101 architecture and intraoral photographs. While the results are promising, it is important to consider them within the broader context of AI applications in endodontics. Direct comparisons with previous studies were not possible due to the novelty of this approach and the lack of comparable methodologies; however, several relevant studies are worth noting. Previous research has reported higher accuracy rates, albeit using different imaging modalities. For example, Zhang et al. (11) achieved 98.3% accuracy in detecting C-shaped root canals in mandibular second molars using a CNN model with a lightweight architecture incorporating a receptive field block. Similarly, Jeon et al. (23) reported a 95.1% accuracy rate using a CNN-based deep learning model called Xception."These models utilized radiographic images."which allowed them to analyze distinctive features of C-shaped canals, such as root furcation and convergence, facilitating differentiation from other canal configurations. The higher accuracy rates in these studies can be attributed to the detailed internal tooth structure information provided by radiographs. While our current accuracy leaves room for improvement, it represents a solid starting point for a novel approach in endodontic diagnostics. Future research could focus on improving the AI model’s performance through larger datasets, advanced image processing techniques, or by integrating multiple imaging modalities while maintaining low radiation exposure. By utilizing only intraoral photographs, we offer a practical alternative that avoids radiation, allowing for safer and potentially more frequent assessments. This method could be particularly useful in screening processes, early detection of anatomical variations, or in situations where radiographic equipment is unavailable, such as in underserved areas or for patients who must avoid radiation exposure, like pregnant women.

5. Conclusions

Achieving an accuracy of 85.1%, our AI-driven approach demonstrates the feasibility of using non-radiographic imaging methods for endodontic diagnostics. While these results are promising, further work is needed to refine the models' accuracy, especially when compared to higher performance levels seen with radiographic-based systems.

Author Contributions

1. Conceptualization: Hamed Karkehabadi, Elham Khoshbin. 2. Data Curation: Amal Mahavi, Hassan Khotanlou. 3. Formal Analysis: Hassan Khotanlou, Leili Tapak. 4. Investigation: Amal Mahavi, Parisa Ranjbar. 5. Methodology: Amal Mahavi, Hassan Khotanlou, Parisa Ranjbar. 6. Project Administration: Hamed Karkehabadi, Elham Khoshbin. 7. Resources: Hamed Karkehabadi. 8. Software: Hassan Khotanlou. 9. Supervision: Hamed Karkehabadi, Elham Khoshbin. 10. Validation: Hamed Karkehabadi, Elham Khoshbin. 11. Visualization: Hassan khotanlou, Amal Mahavi. 12. Writing Original Draft: Amal Mahavi, Leili Tapak, Hassan Khotanlou. 13. Writing, Review, and Editing: Amal Mahavi, Hamed Karkehabadi, Elham Khoshbin.

Funding

This research received no funding from the university or any other organization.

Ethical consideration

The teeth were collected with informed consent; ensuring patients understood their teeth might be used for research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology Department of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences for their cooperation in the preparation of radiographs and their assistance in addressing our questions regarding image interpretation and related processes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this publication.

References

- Celikten, B.; Tufenkci, P.; Aksoy, U.; Kalender, A.; Kermeoglu, F.; Dabaj, P.; Orhan, K. Cone beam CT evaluation of mandibular molar root canal morphology in a Turkish Cypriot population. Clin. Oral Investig. 2016, 20, 2221–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsypremila, G.; Vinothkumar, T.S.; Kandaswamy, D. Anatomic symmetry of root and root canal morphology of posterior teeth in Indian subpopulation using cone beam computed tomography: A retrospective study. Eur. J. Dent. 2015, 09, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, B.V.; Filho, G.A.N.; Salgado, D.M.R.d.A.; Moura-Netto, C.; Giovani, E.M.; Costa, C. Evaluation of the Root Canal Morphology of Molars by Using Cone-beam Computed Tomography in a Brazilian Population: Part I. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 1604–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraiwa, T.; Ariji, Y.; Fukuda, M.; Kise, Y.; Nakata, K.; Katsumata, A.; Fujita, H.; Ariji, E. A deep-learning artificial intelligence system for assessment of root morphology of the mandibular first molar on panoramic radiography. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2019, 48, 20180218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V.; Joshi, P.S.; Shetty, R.; Sarode, G.S.; Chakraborty, D. Root anatomy and canal configuration of human permanent mandibular second molar: A systematic review. J. Conserv. Dent. 2021, 24, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Zuben, M.; Chen, A.; Al-Shahrani, S.; et al. Worldwide prevalence of mandibular second molar C-shaped morphologies evaluated by cone-beam computed tomography. J Endod. 2017, 43, 1442–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shemesh, A.; Levin, A.; Katzenell, V.; Ben Itzhak, J.; Levinson, O.; Avraham, Z.; Solomonov, M. C-shaped canals—prevalence and root canal configuration by cone beam computed tomography evaluation in first and second mandibular molars—a cross-sectional study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2016, 21, 2039–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, D.; Kim, D.-V.; Kim, S.-Y. Analysis of Cause of Endodontic Failure of C-Shaped Root Canals. Scanning 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesień, M.; Olszewski, J. Absorbed doses for patients undergoing panoramic radiography, cephalometric radiography and CBCT. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Heal. 2017, 30, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xi, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, B. A lightweight convolutional neural network model with receptive field block for C-shaped root canal detection in mandibular second molars. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifschitz, V. John McCarthy (1927–2011). Nature 2011, 480, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.J. Artificial intelligence: A modern approach; Pearson Education, Inc., 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Larrivée, N.; Lee, A.; Bilaniuk, O.; Durand, R. Use of artificial intelligence in dentistry: Current clinical trends and research advances. J Can Dent Assoc. 2021, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A. Neural networks and deep learning; Determination Press: San Francisco (CA), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, C.L.; Lin, J.W.; Wei, C.S.; Hsu, M.C. (Eds.) Dentition labeling and root canal recognition using a GAN and rule-based system. 2019 International Conference on Technologies and Applications of Artificial Intelligence (TAAI); 2019. IEEE.

- Saghiri, M.A.; Asgar, K.; Boukani, K.K.; Lotfi, M.; Aghili, H.; Delvarani, A.; Karamifar, K.; Saghiri, A.M.; Mehrvarzfar, P.; Garcia-Godoy, F. A new approach for locating the minor apical foramen using an artificial neural network. Int. Endod. J. 2011, 45, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghiri, M.A.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Gutmann, J.L.; Lotfi, M.; Asgar, K. The Reliability of Artificial Neural Network in Locating Minor Apical Foramen: A Cadaver Study. J Endod. 2012, 38, 1130–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicory, J.; Chandradevan, R.; Hernandez-Cerdan, P.; Huang, W.A.; Fox, D.; Qdais, L.A.; et al. (Eds.) Micro-fracture detection using wavelet features and machine learning. Medical Imaging 2021: Image Processing; 2021. SPIE.

- Ekert, T.; Krois, J.; Meinhold, L.; Elhennawy, K.; Emara, R.; Golla, T.; Schwendicke, F. Deep Learning for the Radiographic Detection of Apical Lesions. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 917–922.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orhan, K.; Bayrakdar, I.S.; Ezhov, M.; Kravtsov, A.; Özyürek, T. Evaluation of artificial intelligence for detecting periapical pathosis on cone-beam computed tomography scans. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Yan, H.; Setzer, F.C.; Shi, K.J.; Mupparapu, M.; Li, J. Anatomically Constrained Deep Learning for Automating Dental CBCT Segmentation and Lesion Detection. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2020, 18, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.-J.; Yun, J.-P.; Yeom, H.-G.; Shin, W.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Jeong, S.-H.; Seo, M.-S. Deep-learning for predicting C-shaped canals in mandibular second molars on panoramic radiographs. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2021, 50, 20200513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Shah, D.; Patel, Z.; Makwana, H.S.; Rajput, A. A comprehensive review on AI in endodontics. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2023, 11, 2321–9653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003, 52, 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi, T.; Shibata, T.; Inamoto, K.; Shibata, N.; Ariji, Y.; Fukuda, M.; Nakata, K.; Ariji, E. Cone-beam computed tomography classification of the mandibular second molar root morphology and its relationship to panoramic radiographic appearance. Oral Radiol. 2020, 37, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkhaneh, M.; Karkehabadi, H.; Alafchi, B.; Shokri, A. Association of root morphology of mandibular second molars on panoramic-like and axial views of cone-beam computed tomography. BMC Oral Heal. 2023, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, B.; Cheung, G.S.; Fan, M.; Gutmann, J.L.; Bian, Z. C-shaped Canal System in Mandibular Second Molars: Part I—Anatomical Features. J. Endod. 2004, 30, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, D.C.; Krell, K.V.; Fuller, M.W. Anatomical and histological features of C-shaped canals in mandibular second molars. J Endod. 1991, 17, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdouses, E.D.; Koutsouri, G.D.; Tripoliti, E.E.; Matsopoulos, G.K.; Oulis, C.J.; Fotiadis, D.I. A computer-aided automated methodology for the detection and classification of occlusal caries from photographic color images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2015, 62, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, R.C.W.; Li, G.-H.; Tew, I.M.; Thu, K.M.; McGrath, C.; Lo, W.-L.; Ling, W.-K.; Hsung, R.T.-C.; Lam, W.Y.H. Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence-Based Photographic Detection of Gingivitis. Int. Dent. J. 2023, 73, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burse, A.; Mahapatra, J.; Reche, A.; Awghad, S.S.; Awghad, S., Jr. Uncovering the Enigma of the C-shaped Root Canal Morphology. Cureus 2024, 16, e61883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, S.; Alharbi, N.; Chaudhry, J.; Khamis, A.H.; El Abed, R.; Ghoneima, A.; Jamal, M. The C-shaped root canal systems in mandibular second molars in an Emirati population. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinanoglu, A.; Helvacioglu-Yigit, D. Analysis of C-shaped Canals by Panoramic Radiography and Cone-beam Computed Tomography: Root-type Specificity by Longitudinal Distribution. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, H.; Wu, Y.-N. The C-shaped Root Canal Configuration: A Review. J Endod. 2007, 33, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.C.; Wanderley, V.A.; Vasconcelos, K.d.F.; Leite, A.F.; Pauwels, R.; Nadjmi, M.; Oliveira, M.L.; Tanomaru-Filho, M.; Jacobs, R. Evaluation of 10 Cone-beam Computed Tomographic Devices for Endodontic Assessment of Fine Anatomic Structures. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Results obtained from different models.

Table 1.

Results obtained from different models.

| Architectures |

Number of layers |

Number of parameters |

Accuracy% |

Confusion matrix |

| |

True Class |

| EfficientNetB1 |

340 |

8149640 |

82.1 |

Predicted

Class |

|

| EfficientNetB3 |

386 |

11177264 |

77.7 |

Predicted

Class |

|

| EfficientNetB5 |

571 |

29038328 |

82.1 |

Predicted

Class |

|

| ResNet |

152 |

58856449 |

80.6 |

Predicted

Class |

|

| ResNet |

101 |

43151361 |

85.1 |

Predicted

Class |

|

| ResNet |

50 |

24112513 |

85.1 |

Predicted

Class |

|

| VGG19 |

19 |

20155969 |

71.65 |

Predicted

Class |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).