Introduction

Salmon and trout are characterized by elongated and streamlined bodies, enabling fast swimming in both freshwater and marine environments. Most of them are anadromous and their life cycle includes distinct stages: egg, fry, smolt, and adult, with some species displaying remarkable homing abilities and returning to their natal streams for reproduction (Groot and Margolis 1991; Quinn 2007). In South Korea, 11 salmoniform species have been identified (Kim et al. 2005). Among these, three species, Brachymystax lenok tsinlingensis, Oncorhynchus keta, and Oncorhynchus masou masou, are native to South Korea, whereas Oncorhynchus mykiss was introduced for aquaculture and recreational fishing. These species play significant roles in Korean riverine ecosystems and are both culturally and commercially important.

Salmo trutta, endemic to most of Europe and commonly referred to as brown trout, is a freshwater migratory species that spawns in riverbeds composed of gravel or sand with fast-flowing, cool, and oxygen-rich waters. This species exhibits a high degree of behavioral variability, with some populations being purely freshwater residents, whereas others are anadromous, known as sea trout, and migrate to the ocean before returning to rivers to spawn. This species is prized for its adaptability, thrives in a wide range of habitats, and is well-known for sport fishing (Elliott 1994; Klemetsen et al 2003).

Over the past few decades, S. trutta has been introduced into many regions outside of its native habitats, including North America, Australia, and parts of Asia, including South Korea, for food consumption and recreational fishing (Townsend 1996; Klemetsen et al. 2003; Behnke 2010; McIntosh et al. 2010; Korsu et al. 2010; Hasegawa 2020; Park et al. 2022). As an aggressive predator and competitor, this alien species outcompetes native fish for food and habitat and preys on native aquatic animals, disrupting the natural aquatic ecosystems; thus, S. trutta is a significant ecological threat to several non-native regions (Townsend and Crowl 1991; Klemetsen et al. 2003; McDowall 2003; McHugh and Budy 2006; Korsu et al. 2010; McIntosh et al. 2010; Hasegawa 2020). In addition, S. trutta hybridizes with native salmonid species (Verspoor 1988; Meldgaard et al. 2007; Castillo et al. 2008), reducing the genetic integrity and fitness of native populations. Genetic mixing threatens the long-term viability of native species, exacerbating their decline and destabilizing freshwater ecosystems in which these species play critical roles. Owing to the ecological threats exerted by this species, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) has listed S. trutta in the “100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species” (Lowe et al. 2000).

Although exact records of its introduction are unavailable, Park et al. (2022) reported that S. trutta successfully established a sexually mature population downstream of the Soyang Reservoir in Chuncheon-si, Gangwon-do, South Korea. This area is enclosed by three reservoirs: Soyang Reservoir, which discharges water into the Soyang River and drains into the northeastern Uiam Reservoir; Paro Lake, which is connected to the Bukhan River and drains into the northwestern Uiam Reservoir; and southern Uiam Reservoir, which discharges water into the Han River Basin. As a result, the S. trutta population that was introduced into South Korea became landlocked. As a cold-water species, its optimal habitat temperature ranges between 12 and 19 °C; however, it is resilient and survives at temperatures up to 24.7 °C (Molony 2001). During summer, most rivers in South Korea approach 30 °C, limiting the species' ability to establish a wide distribution. Nevertheless, owing to hydroelectric power generation, the multipurpose dam continuously discharges cold water from its mid-layer, creating conditions that allow for S. trutta survival downstream.

In 2021, the Ministry of Environment of South Korea legally designated S. trutta as an invasive species to prevent further spread and minimize ecological damage through eradication and removal projects (ME 2021; NIE 2023). Owing to its popularity in recreational fishing and ecological adaptability, there are concerns regarding the impact of widespread S. trutta release and distribution. Therefore, close monitoring of habitat and potential spread is required, necessitating the urgent need for rapid and effective species identification in new habitats and areas of expansion. However, the current assessment and monitoring of S. trutta are still conducted using traditional methods, such as skimming nets, gill nets, or angler-provided rod catch data. Electrofishing, a common method used in freshwater fish surveys, is illegal in South Korea. Given ecological traits of S. trutta, including its preference for cold water and long-distance migration, monitoring via traditional methods is challenging. Moreover, these surveys are expensive, labor-intensive, and time-consuming.

Environmental DNA (eDNA)-based real-time PCR (quantitative PCR or qPCR) assays are powerful tools for molecular monitoring of invasive fish species in aquatic ecosystems, as well as for monitoring commercially exploited, rare, or endangered fish species (e.g., Wilcox et al. 2015; Atkinson et al. 2018; Fernandez et al. 2018; Knudsen et al. 2019; Hernandez et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2021). This method involves the collection of water samples from an environment where a species may be present and analysis of the obtained samples for the detection of biological material, such as skin cells, scales, mucus, blood, feces, and gametes, shed by the species. qPCR amplifies DNA sequences unique to the target species, enabling highly sensitive detection even at low population densities. This technique is particularly useful for early detection, tracking the spread, and monitoring the distribution of exotic fish species, such as S. trutta (Gustavson et al. 2015; Banks et al. 2016; Carim et al. 2016; Deutschmann et al. 2019; Hernandez et al. 2020).

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to determine the distribution range of S. trutta through qPCR analysis of water samples collected from river water downstream of the Soyang Reservoir and around the Uiam Reservoir, where the species is known to inhabit.

Materials and Methods

Sampling of Fish Specimens and Genomic DNA (gDNA) Extraction

Specimens of S. trutta (n = 2), the other five salmonid species, i.e., B. lenok tsinlingensis, O. keta, O. mykiss, Thymallus grubii, and Salmo salar, and 19 common freshwater fish species were collected from rivers or local markets in South Korea. A piece of the salmonid pelvic fin was excised and used for gDNA extraction, as previously described by Asahida et al. (1996). The extracted gDNA was resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0), and its quantity and quality were assessed using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop™ One, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Modification of Primers and Probe

All mitochondrial cytochrome

b gene (

mt-cyb) sequences of

S. trutta haplotypes and all reference sequences of mitochondrial genomes of salmoniform species were retrieved from GenBank (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and aligned using ClustalW in BioEdit 7.2 (Hall 1999). Following comparison of the aligned nucleotide matrices, the forward and reverse primers and hydrolysis probe reported by Carim et al. (2016) were modified, which were used in the qPCR assays. The melting temperature (Tm) and secondary structures of the primers were predicted using the Sequence Manipulation Suite ver. 2 (

https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/) (Stothard 2000) and optimized prior to oligonucleotide synthesis.

Environmental Water Sampling and eDNA Extraction

Environmental water samples (each 1–2 L) were collected in sterile disposable plastic bottles at a depth of 10 m from eight stations located downstream of the Soyang Reservoir and around the Uiam Reservoir between January and March 2023 (

Table 1) in Chuncheon-si, Gangwon-do, South Korea. The samples were vacuum-filtered through glass microfiber filters (Grade GF/F circles, 47 mm; Whatman, Marlborough, MA, USA). Each filter was folded in half four times using uncontaminated forceps, inserted into a 2.0-mL microtube, and placed in a cooled ice box with polyethylene bags containing ice, protected from light exposure. They were then transported directly to the laboratory and stored in at –70 °C until further use. Each filter was broken using a Omni Bead Ruptor 12 Bead Mill Homogenizer (OMNI International, Kennesaw, GA, USA) and eDNA was extracted using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The eDNA was finally eluted in 50 μL of sterile distilled water and immediately stored at –20 °C for further processing.

qPCR Assay

qPCR amplification was conducted in triplicate (three technical replicates) for each eDNA sample using GoTaq® Probe qPCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The reaction mixture (10 μL) contained 1 μL of eDNA as a template, 0.2 μM each of the forward Str-cyb-0297f (5′-CCGAGGACTCTACTATGGT-3′) and reverse Str-cyb-0384r (5′-GGAAGAACGTAGCCCACG-3′) primers, and the hydrolysis probe Str-cyb-0341p (5′-FAM-ATATCGGAGTCGTACTGCTA-MGB-Eclipse-3′), which were synthesized by Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, South Korea). qPCR was performed using a QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the following cycling conditions: an initial activation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, and annealing and extension at 60 °C for 45 s. The gDNAs (20 ng μL-1) extracted from two S. trutta specimens were used as positive controls. Sterile distilled water was used as a negative control to monitor contamination during filtration, eDNA extraction, and qPCR analysis.

A synthesized partial DNA fragment of S. trutta mt-cyb containing all the binding sites for the forward and reverse primers and the hydrolysis probe was produced by gene synthesis and inserted into a plasmid by Bioneer Inc. (Daejeon, South Korea). The sensitivity of the oligonucleotide primers and the hydrolysis probe was tested against 10-fold serial dilutions of the plasmid DNA (109 copies rxn-1) in triplicate for each dilution. The results were used to produce a standard curve for S. trutta eDNA. Their specificity was also tested against five other salmonid species and 19 freshwater fish belonging to diverse orders and families that are commonly found in South Korea.

Results

Modified Primers and Probe

In this study, we modified the forward and reverse primers, as well as the hydrolysis probe, previously described by Carim et al. (2016), which were specific to

S. trutta and designed based on

mt-cyb sequences (

Table 2). The Tm of the forward and reverse primers used in this study (Str-cyb-0297f and Str-cyb-0384r, respectively) were lower than those used by Carim et al. (2016) (Str-cyb-0294f and Str-cyb-0382r, respectively). Both primers used in the present study showed exact matches with all

S. trutta haplotypes in the GenBank database. Additionally, the hydrolysis probe used in this study (Str-cyb-0341p) had a higher Tm than that used by Carim et al. (2016) (Str-cyb-0345p). The probe matched all

S. trutta haplotypes in the GenBank database, with a single base-pair mismatch in only one haplotype (GenBank accession number JX960839) reported by Crête-Lafrenière et al. (2012), but multiple base-pair mismatches with other salmoniform species, including the congeneric

Salmo ischchan,

Salmo obtusirostris, and

Salmo salar.

The forward and reverse primers produced a 105-bp amplicon, as predicted using conventional PCR amplification. The hydrolysis probe consisted of a 20-mer oligonucleotide with a fluorophore, fluorescein, covalently attached to the 5′-end, and a quencher, MGB-Eclipse, at the 3′-end. This combination of oligonucleotides was unique to Salmo trutta and was not found in other salmoniform species.

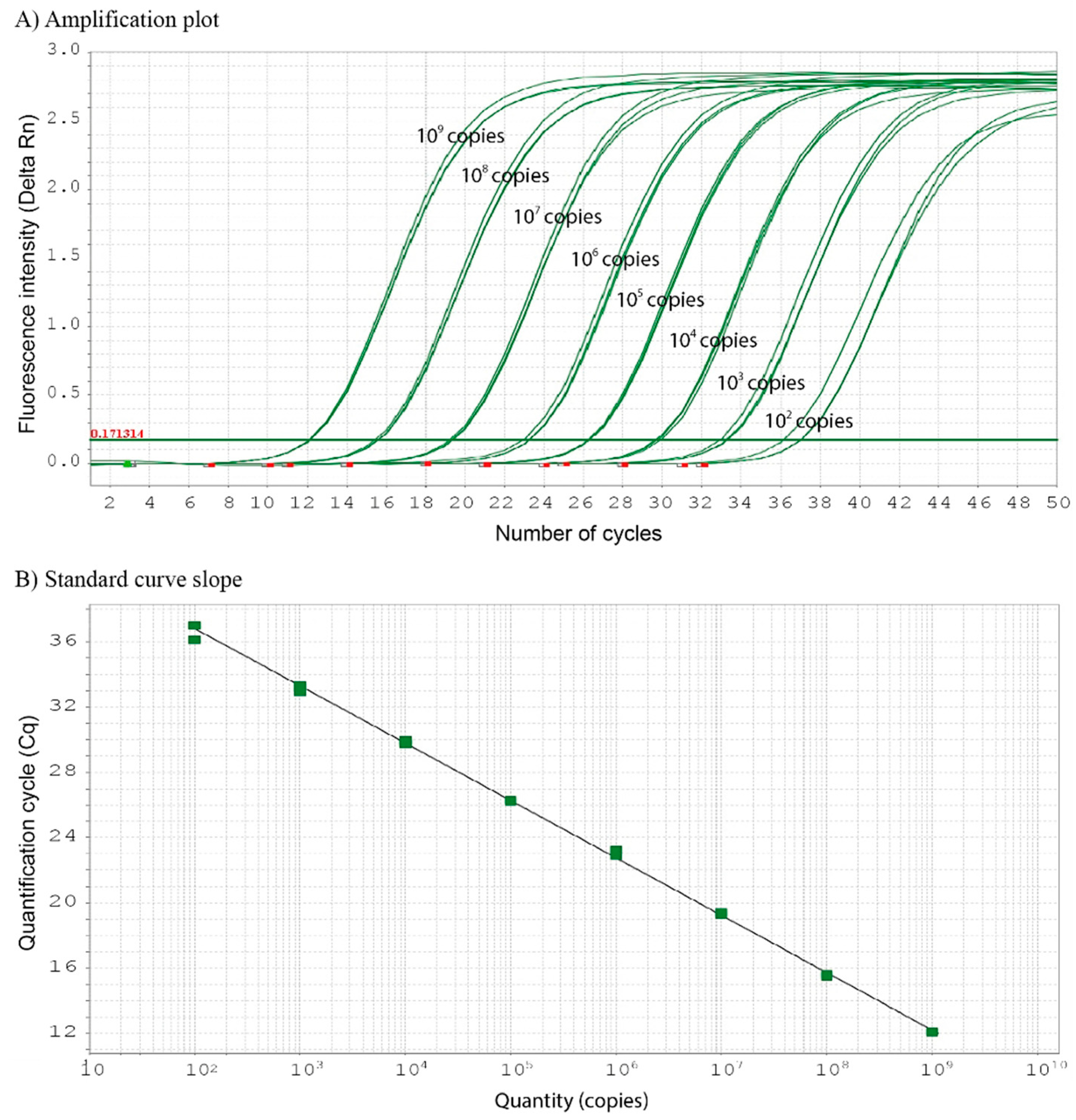

Sensitivity and Specificity Tests

qPCR amplification using the designed primers and probe resulted in positive amplification with a quantification cycle (Cq) value of 17.776 against a standard concentration of the gDNA (20 ng μL

-1) extracted from

S. trutta. No background amplification was observed. The sensitivity test was conducted using a serial dilution of plasmid DNA (1–10

9 copies per reaction), in which a partial DNA fragment of

S. trutta mt-cyb containing all the binding sites for the forward and reverse primers and the hydrolysis probe were inserted. An inverse relationship was observed between the Cq values and plasmid DNA concentrations, with a detection limit of as low as 10

2 copies per reaction of plasmid DNA and a Cq value of 36.717 (

Figure 1). Therefore, the Cq value was set as the lowest detection limit to achieve acceptable levels of precision and accuracy in the qPCR assay. This correlation was used to generate the standard curve slope, which produced the following linear regression equation:

Linear regression was used to detect and quantify S. trutta eDNA in environmental water samples.

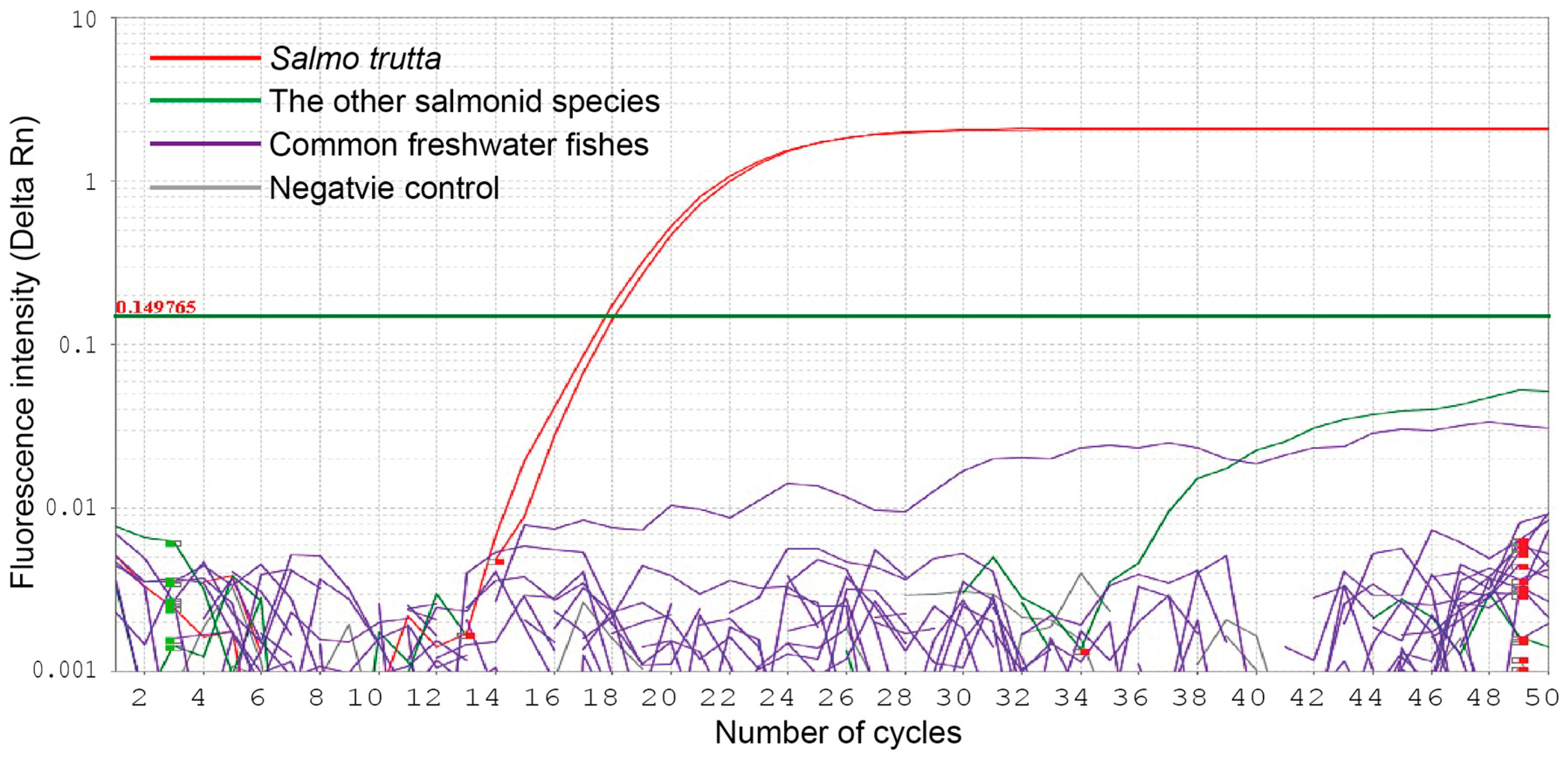

To confirm the specificity of the primers and hydrolysis probe for

S. trutta, we carried out qPCR amplification of 5 salmonid species (

B. lenok tsinlingensis,

O. keta,

O. mykiss,

T. grubii, and

S. salar) and 19 freshwater fishes belonging to diverse orders and families (

Acheilognathus rhombeus,

Coreoperca herzi,

Cyprinus carpio,

Gasterosteus aculeatus,

Hemiculter eigenmanni,

Lepomis macrochirus,

Liobagrus andersoni,

Misgurnus anguillicaudatus,

Monopterus albus,

Mugil cephalus,

Odontobutis platycephala,

Orthrias nudus,

Oryzias latipes,

Plecoglossus altivelis,

Repomucenus olidus,

Rhynchocypris oxycephalus,

Silurus asotus,

Tachysurus fulvidraco, and

Zacco platypus) that are commonly found in rivers and lakes or local markets of South Korea. Only two

S. trutta specimens successfully produced positive fluorescence amplifications, whereas the other five salmonid and freshwater fish failed to produce measurable amplifications (

Figure 2).

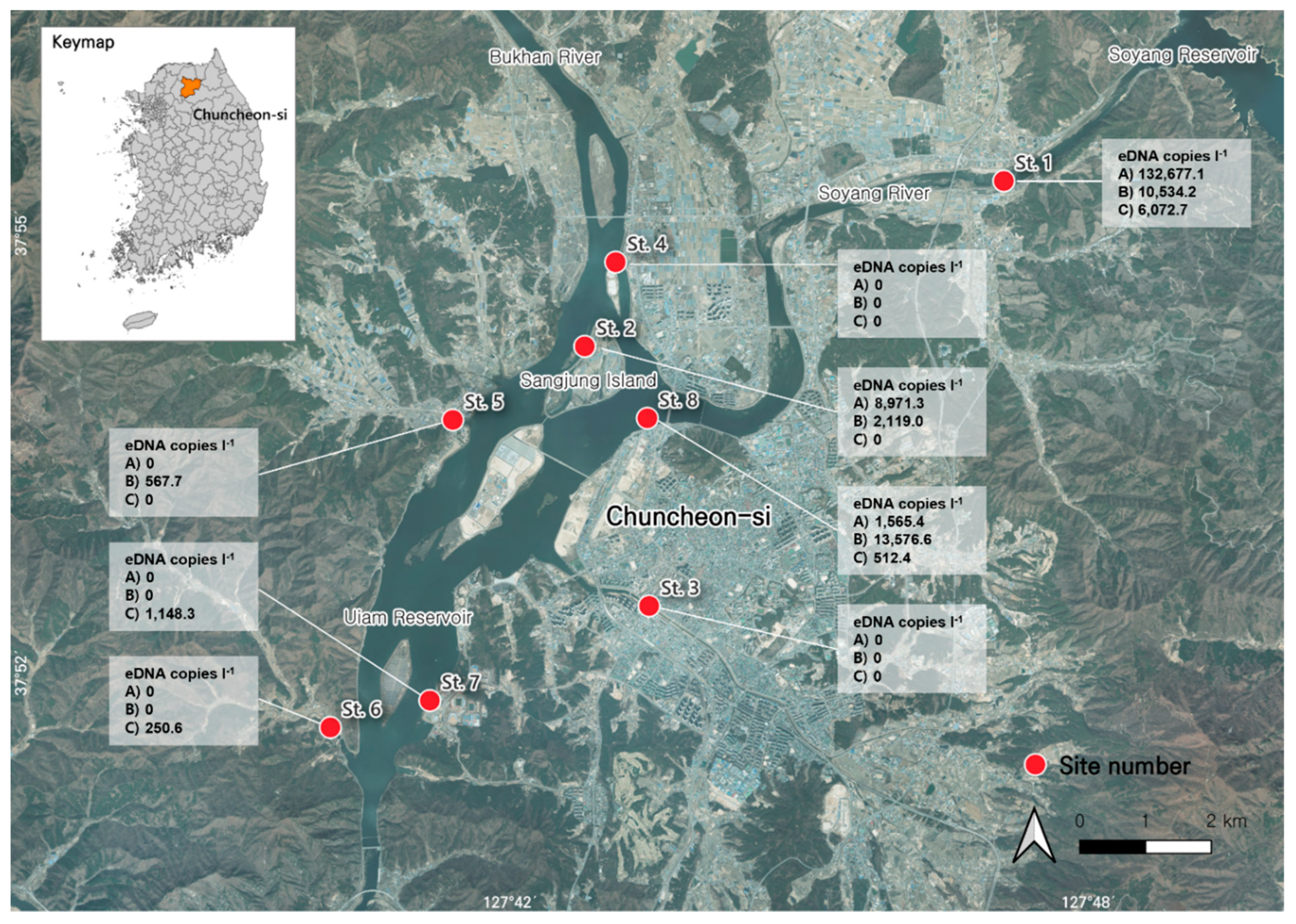

qPCR Assay of Environmental Water Samples

The

S. trutta-specific primers and hydrolysis probe used in this study were used to amplify eDNA extracted from the collected environmental water samples (n = 24). Positive amplifications were observed in 11 samples (Stns. 1, 2, and 8 on January 2023 at Stns. 1, 2, 5, and 8 in February 2023, and Stns. 1, 6, 7, and 8 in March 2023), with Cq values ranging from 30.665 to 38.629, corresponding to plasmid copy numbers from 250.6 copies L

-1 to 132,677.1 copies L

-1 (

Table 3). The highest value, 132,677.1 ± 6,386.3 copies L

-1, was observed for St. 1.

S. trutta eDNA was detected in all three replicates in the upstream section of the Soyang River (St. 1), located downstream of the Soyang Reservoir, between January and March 2023 (

Figure 3). It was also detected in all three replicates from the downstream section (St. 8) in February 2023 but in only one replicate out of three in January and March. Additionally, it was detected in all three replicates from Sangjung Island (St. 2), located upstream of the Uiam Reservoir, in January and February 2023; however, no

S. trutta eDNA was detected in March. In contrast, two small streams flowing into the Uiam Reservoir (Stns. Five and 6) possessed

S. trutta eDNA in only one out of three replicates in February and March, whereas St. 7, located downstream of the Uiam Reservoir, showed

S. trutta eDNA in only one of the three replicates in March at very low concentrations. However,

S. trutta eDNA was not detected in the Gongji Stream (St. 3), which flows into the Uiam Reservoir, or in St. 4, which is located downstream of the Bukhan River. Representative samples that showed positive amplifications were further verified via Sanger sequencing to confirm the absence of false-positive results (data not shown).

Discussion

As the habitat range of S. trutta, a major invasive species in South Korea, expands, concerns are growing over the potential ecological disruptions in the Uiam Reservoir connected to the Soyang River, including habitat and food competition with native freshwater fish. Therefore, year-round spatio-temporal monitoring and habitat usage studies of this invasive species are necessary for effective management practices.

eDNA-based qPCR assays enhance management efforts aimed at preventing the establishment and spread of invasive species, and by providing rapid and precise results, is useful in protecting native biodiversity (Lodge et al. 2012; Thomsen and Willerslev 2015). The effectiveness of qPCR for species detection depends on the development of species-specific primers that exclusively amplify the DNA of the target species, minimizing false positives from cross-amplification with closely related species (Ficetola et al. 2008; Wilcox et al. 2013). To ensure target specificity, the primers need to be tested against all related species potentially present in the study area to confirm that only the target species is amplified. This validation process is essential for the accurate detection of species using molecular monitoring. Using the forward and reverse primers and hydrolysis probe specific to S. trutta that were modified from Carim et al. (2016), we aimed to amplify S. trutta eDNA from environmental water samples by qPCR assay, even if present at low concentrations, to allow for accurate and early detection of the target species.

It has been previously reported that qPCR targeting S. trutta is an important tool for detecting and monitoring this invasive species (Banks et al. 2016; Carim et al. 2016; Deutschmann et al. 2019; Hernandez et al. 2020). This method aids in tracking the spread of S. trutta and supports efforts to control its population and mitigate ecological damage. In this study, we modified the primer set (reducing the Tm of the forward and reverse primers) and hydrolysis probe (increasing the Tm of the hydrolysis) reported by Carim et al. (2016) to enhance qPCR sensitivity and specificity. Reducing the Tm of both primers improved their binding efficiency to eDNA at low temperatures, increasing the amplification efficiency, especially in low-concentration samples, and resulting in greater detection sensitivity. Additionally, increasing the Tm of the hydrolysis probe enhances its binding stability to the target sequence, ensuring more selective binding to the correct target and reducing nonspecific binding. This minimizes false positives and enables more accurate detection of the target species. Aligning the Tm of the primers and probe improved the overall balance and efficiency of the qPCR, thus enhancing the robustness of the qPCR assay, particularly when complex or degraded samples are used. These optimizations led to more reliable and precise detection of species, such as S. trutta, via molecular monitoring.

In the present study, S. trutta eDNA was detected in high quantities and frequencies in the upstream (St. 1) and downstream (St. 8) sections of the Soyang River, which is consistent with previous findings (NIE 2020, 2023; Park et al. 2022; Kim et al. 2023). These areas are characterized by shallow water depths, with riverbeds mainly composed of sand, pebbles, gravel, and boulders (Park et al. 2022; NIE 2023). In addition to these two stations, S. trutta eDNA was detected on Sangjung Island (St. 2), located upstream of the Uiam Reservoir. The environmental water was released from the middle layer of the Soyang Reservoir for hydroelectric power generation, maintaining a discharge water temperature of 15 °C throughout the year. As a result, the downstream area, approximately 10 km before merging with the Bukhan River, is influenced by the cold water released from the reservoir (Yi et al. 2006). These three stations were directly affected by cold water. Thus, the riverbed structure and hydraulic characteristics of the Soyang River provide an optimal environment for S. trutta inhabitation and spawning (Kondolf and Wolman 1993; Young 1995; Armstrong et al. 2003), because this species requires low water temperatures and high levels of dissolved oxygen. Park et al. (2022) observed sexually mature males and females in the Soyang Reservoir, supporting the conclusion that S. trutta migrates downstream from the Soyang Reservoir for spawning. Therefore, these areas serve as overwintering habitats for anadromous fish, such as S. trutta, which migrate to the upper rivers or streams for reproduction. This species also has a high potential to expand its habitat to the Paro Reservoir, located upstream of the Uiam Reservoir, because of its distinct life cycle, necessitating broader monitoring efforts across the Han River basin.

Our study confirmed previously known habitats of S. trutta and demonstrated that this fish is expanding its habitat. Consistent with previous findings, we found that S. trutta eDNA was detected in the Soyang River (Park et al. 2022; Kim et al. 2023); however, we also detected S. trutta in the Uiam Reservoir, indicating that the species utilizes a broader range of habitats than previously reported. Although the quantity of eDNAs does not always directly reflect the biomass or number of individuals, owing to various biotic and abiotic factors in the natural habitats of the target species (Goldberg et al. 2015; Barnes and Turner 2016; Deutschmann et al. 2019; Knudsen et al. 2019; Yates et al. 2019), our results highlight qPCR as an alternative tool for determining the presence of S. trutta in aquatic environments. This method offers a more efficient and effective approach for assessing and monitoring practices than traditional field surveys. Furthermore, this approach can support conservation efforts by habitats that require removal of invasive species with the goal of restoring the area to its predefined historical conditions (Banks et al. 2016).

This survey was conducted during a limited period, specifically during the winter months (January and February) and early spring (March), when water was at the lowest annual temperature (Park et al. 2022). These water temperatures are suitable for S. trutta, enabling broad species distribution. It is necessary to apply molecular monitoring during warmer months, that is, from late spring to fall, when water temperatures rise. During the period, it is likely that S. trutta move to deeper and cooler areas at the bottom of the Uiam Reservoir, where lower water temperatures are maintained. In this study, we found that S. trutta eDNA was more frequently detected at the southern stations (Stns. 5, 6, and 7), which were located around the main water body of the Uiam Reservoir in February and March, when the water temperature was higher than that in January.

In addition, S. trutta frequently hybridizes with other native salmonid species (Verspoor 1988; Meldgaard et al. 2007; Castillo et al. 2008). It also has a high potential to hybridize with native salmonid species in South Korea, such as B. lenok tsinlingensis and O. masou masou, leading to genetic mixing that reduces the integrity and fitness of native populations. Such hybridization may result in the loss of locally adapted traits, inhibiting resilience to environmental changes, climate stress, and competition with invasive salmonid species. The introduction of S. trutta through intentional stocking or natural migration to other South Korean rivers and streams could negatively impact the natural genetic pollution, further endangering native populations. S. trutta fishing has gained popularity and attempts have been made to transplant this species into other rivers or streams in online communities, highlighting the need for ongoing monitoring to prevent its spread. Overall, our findings highlight the potential for the future use of our qPCR assay for the monitoring of invasive fish species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: SH Kim, SI Lee, and K-Y Kim; field sampling: SH Kim; lab experiment: SE JO; manuscript writing: SH Kim, SH Lee, and K-Y Kim.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Ecology funded by the Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Korea (NIE-A-2024-09 and NIE-A-2024-19).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate Mr. Jung-Soo Heo of AquaGenTech Co., Ltd. for his valuable comments and suggestions on qPCR assays and Mr. Joo-Won Shin for his assistance with environmental water sampling. Owing to their contributions, we have been able to improve the quality of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The sponsors have no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Armstrong JD, Kemp PS, Kennedy GJA, Ladle M, Milner NJ (2003) Habitat requirements of Atlantic salmon and brown trout in rivers and streams. Fish Res 62(2):143–170. [CrossRef]

- Asahida T, Kobayashi T, Saitoh K, Nakayama I (1996) Tissue preservation and total DNA extraction form fish stored at ambient temperature using buffers containing high concentration of urea. Fish Sci 62(5):727–730. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson S, Carlsson JEL, Ball B, Egan D, Kelly-Quinn M, Whelan K, Carlsson J (2018) A quantitative PCR-based environmental DNA assay for detecting Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquat Conserv 28(5):1238–1243. [CrossRef]

- 2016; Banks JC, Demetras NJ, Hogg ID, Knox MA, West DW (2016) Monitoring brown trout (Salmo trutta) eradication in a wildlife sanctuary using environmental DNA.

- Barnes MA, Turner CR (2016) The ecology of environmental DNA and implications for conservation genetics. Conserv Genet 17(1):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Behnke R (2010) Trout and salmon of North America. The Free Press, Simon & Schuster Inc., New York, 360 pp.

- Carim KJ, Wilcox TM, Anderson M, Lawrence DJ, Young MK, McKelvey KS, Schwartz MK (2016). An environmental DNA marker for detecting nonnative brown trout (Salmo trutta). Conserv Genet Resour 8:2591–261. [CrossRef]

- Castillo AGF, Ayllon F, Moran P, Izquierdo JI, Martinez JL, Beall E, Garcia-Vazquez E (2008) Interspecific hybridization and introgression are associated with stock transfers in salmonids. Aquaculture 278(1–4):31–36. [CrossRef]

- Crête-Lafrenière A, Weir LK, Bernatchez L (2012) Framing the Salmonidae family phylogenetic portrait: a more complete picture from increased taxon sampling. PLoS ONE 7(10): e46662. [CrossRef]

- Deutschmann B, Müller AK, Hollert H, Brinkmann M (2019) Assessing the fate of brown trout (Salmo trutta) environmental DNA in a natural stream using a sensitive and specific dual-labelled probe. Sci Total Environ 655:321–327. [CrossRef]

- Elliott JM (1994) Quantitative ecology and the brown trout. Oxford University Press.

- Fernandez S, Sandin MM, Beaulieu PG, Clusa L, Martinez JL, Ardura A, García-Vázquez E (2018) Environmental DNA for freshwater fish monitoring: insights for conservation within a protected area. PeerJ 6:e4486. [CrossRef]

- Ficetola GF, Miaud C, Pompanon F, Taberlet P (2008) Species detection using environmental DNA from water samples. Biol Lett 4(4):423–425. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg CS, Strickler KM, Pilliod DS (2015) Moving environmental DNA methods from concept to practice for monitoring aquatic macroorganisms. Biol Conserv 183:1–3. [CrossRef]

- Groot C, Margolis L (eds) (1991) Pacific salmon life histories. UBC Press, Vancouver.

- Gustavson MS, Collins PC, Finarelli JA, Egan D, Conchúir RÓ, Wightman GD, King JJ, Gauthier DT, Whelan K, Carlsson JE, Carlsson J (2015) An eDNA assay for Irish Petromyzon marinus and Salmo trutta and field validation in running water. J Fish Biol 87(5):1254–1262. [CrossRef]

- Hall TA (1999) BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp S 41:95–98.

- Hasegawa K (2020) Invasions of rainbow trout and brown trout in Japan: A comparison of invasiveness and impact on native species. Ecol Freshw Fish 29(3):419–428. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez C, Bougas B, Perreault-Payette A, Simard A, Côté G, Bernatchez L (2020) 60 specific eDNA qPCR assays to detect invasive, threatened, and exploited freshwater vertebrates and invertebrates in Eastern Canada. Environ DNA 2(3):373–386. [CrossRef]

- Kim I-S, Choi Y, Lee C-L, Lee Y-J, Kim B-J, Kim J-H (2005) Illustrated book of Korean fishes. Kyo-Hak Publishing Co, Ltd, Seoul, 615 pp.

- Kim J, Hong D, Kim J, Kim B, Kim H, Choi J (2023) Length–weight relationship and condition factor of the invasive fish species brown trout (Salmo trutta) in Soyang River. J Agric Life Environ Sci 35(4):604–617. (in Korean).

- Kim K-Y, Heo JS, Moon SY, Kim K-S, Choi J-H, Yoo J-T (2021) Preliminary application of molecular monitoring of the Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii) based on real-time PCR assay utilization on environmental water samples. Korean J Ecol Environ 54(3):209–220. [CrossRef]

- Klemetsen A, Amundsen PA, Dempson JB, Jonsson B, Jonsson N, O’Connell MF, Mortensen E (2003) Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L., brown trout Salmo trutta L. and Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus (L.): a review of aspects of their life histories. Ecol Freshw Fish 12(1):1–59. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen SW, Ebert RB, Hesselsøe M, Kuntke F, Hassingboe J, Mortensen PB, Thomsen PF, Sigsgaard EE, Hansen BK, Nielsen EE, Møller PR (2019) Species-specific detection and quantification of environmental DNA from marine fishes in the Baltic Sea. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 510:31–45. [CrossRef]

- Kondolf GM, Wolman MG (1993) The sizes of salmonid spawning gravels. Water Resour Res 29(7):2275–2285. [CrossRef]

- Korsu K, Huusko A, Muotka T (2010) Impacts of invasive stream salmonids on native fish: using meta-analysis to summarize four decades of research. Boreal Environ Res 15:491–500.

- Lodge DM, Turner CR, Jerde CL, Barnes MA, Chadderton L, Egan SP, Feder JL, Mahon AR, Pfrender ME (2012) Conservation in a cup of water: estimating biodiversity and population abundance from environmental DNA. Mol Ecol 21(11):2555–2558. [CrossRef]

- Lowe S, Browne M, Boudjelas S, De Poorter M (2000) 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species: A Selection from the Global Invasive Species Database, vol 100. Invasive Species Specialist Group, Auckland.

- McDowall RM (2003) Impacts of introduced salmonids on native galaxiids in New Zealand upland streams: a new look at an old problem. Trans Am Fish Soc 132(2):229–238. [CrossRef]

- McHugh P, Budy P (2006) Experimental effects of nonnative brown trout on the individual- and populations-level performance of native Bonneville cutthroat trout. Trans Am Fish Soc 135(6):1441–1455. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh AR, McHugh PA, Dunn NR, Goodman JM, Howard SW, Jellyman PG, O’Brien LK, Nyström P, Woodford DJ (2010) The impact of trout on galaxiid fishes in New Zealand. N Z J Ecol 34(1):195–206.

- Meldgaard T, Crivelli AJ, Jesensek D, Poizat G, Rubin JF, Berrebi P (2007) Hybridization mechanisms between the endangered marble trout (Salmo marmoratus) and the brown trout (Salmo trutta) as revealed by in-stream experiments. Biol Conserv 136(4):602–611. [CrossRef]

- Molony B (2001) Environmental requirements and tolerances of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) with special reference to Western Australia: a review. Department of Fisheries, Government of Western Australia, Perth, Australia.

- ME (Ministry of Environment) (2021) Notice on designation of ecosystem-disrupting organisms. ME(2021-176).(in Korea).

- NIE (National Institute of Ecology) (2020) Investigating ecological risk of alien species in 2020. National Institute of Ecology, Seocheon, 208 pp.

- NIE (National Institute of Ecology) (2023) Monitoring of invasive alien species in 2023. National Institute of Ecology, Seocheon, 208 pp.

- Park CW, Yun YJ, Kim JW, Bae DY, Kim JG, Kim SH (2022) An Identification of domestic habitat and settlement of the invasive exotic fish brown trout, Salmo trutta. Korean J Ichthyol 34(4):270–276. (in Korean).

- Quinn TP (2007) The behavior and ecology of Pacific salmon and trout. University of British Columbia Press, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, MD.

- Stothard P (2000) The sequence manipulation suite: JavaScript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. BioTechniques 28(6):1102–1104. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen PF, Willerslev E (2015) Environmental DNA–An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biol Conserv 183:4–18. [CrossRef]

- Townsend CR (1996) Invasion biology and ecological impacts of brown trout Salmo trutta in New Zealand. Biol Conserv 78(1–2):13–22. [CrossRef]

- Townsend CR, Crowl TA (1991) Fragmented population structure in a native New Zealand fish: an effect of introduced brown trout?. Oikos 61(3):347–354. [CrossRef]

- Verspoor E (1988) Widespread hybridization between native Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, and introduced brown trout, S. trutta, in eastern Newfoundland. J Fish Biol 32(3):327–334. [CrossRef]

- Wilcox TM, Carim KJ, McKelvey KS, Young MK, Schwartz MK (2015) The dual challenges of generality and specificity when developing environmental DNA markers for species and subspecies of Oncorhynchus. PLOS ONE 10(11):e0142008. [CrossRef]

- Wilcox TM, McKelvey KS, Young MK, Jane SF, Lowe WH, Whiteley AR, Schwartz MK (2013) Robust detection of rare species using environmental DNA: the importance of primer specificity. PLOS ONE 8(3):e59520. [CrossRef]

- Yates MC, Fraser DJ, Derry AM (2019) Meta-analysis supports further refinement of eDNA for monitoring aquatic species-specific abundance in nature. Environ DNA 1(1):5–13. [CrossRef]

- Yi YK, Lee HS, Baek HJ, Kim YD (2006) Temperature variation of release water of Soyang Reservoir. KSCE J Civ Eng:1657–1660. (in Korean).

- Young MK (1995) Conservation assessment for inland cutthroat trout, vol 256. United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, CO.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).