1. Introduction

The effectiveness of Digital Serious Educational Games (SEGs) in elementary-level mathematics has garnered considerable attention in recent years, as educators explore innovative ways to engage students and improve learning outcomes. Research suggests that SEGs not only enhance the enjoyment of learning but also foster critical thinking and problem-solving skills, thereby deepening students’ understanding of mathematical concepts (Lin & Cheng, 2022). Consequently, many schools are increasingly incorporating SEGs into their curricula, offering interactive experiences that cater to diverse learning styles and promote collaboration among peers (Tepho & Srisawasdi, 2023). These platforms often employ gamification strategies that motivate students to persist through challenging tasks and encourage a growth mindset in mathematics. This trend reflects a broader shift in education, where technology and creativity converge to create dynamic learning environments that prepare students for the complexities of the modern world.

This study focuses on investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the motivation and performance of students with learning difficulties in mathematics, specifically through the use of a digital SEG with sixth-grade students. The pandemic has significantly affected student engagement, particularly for students with learning disabilities, who faced challenges in maintaining motivation and academic performance during the shift to online learning (Alqahtani & Kamhi, 2024; Syakur et al., 2023). While digital tools like SEGs offer interactive and engaging learning experiences, their specific effectiveness in boosting both motivation and performance for students with learning disabilities remains an area that warrants further investigation.

The necessity of this study lies in addressing the generalizability issues associated with the use of game-based learning (GBL) in math education. As prior research has highlighted, the effects of GBL on learning outcomes and motivation are not universally consistent across different settings and populations. This inconsistency may arise from various factors influencing the effectiveness of educational games, such as individual student characteristics, learning environment variations, and content differences (Pan et al., 2022; Schrader, 2022).

This research seeks to bridge this gap by examining how a digital SEG can mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic on academic outcomes and motivation among students with learning difficulties, thereby contributing to the expanding body of knowledge on gamification and digital tools in special education contexts (Tepho & Srisawasdi, 2023). Findings from a systematic review by Dan et al. (2024) also underscore the gaps in the existing literature on primary school-level interventions, further supporting the need for this study.

This research examines whether digital math SEGs contribute to students’ acquisition of knowledge, skills, and motivation in mathematics, particularly in first-degree equations. This will be tested by comparing a group of students who practiced with the digital math SEG “Battleship” against a group of students who studied the textbook. Thus, the general objective of the research is to determine the effect of digital math SEGs on sixth-graders’ (11-12 years old) math performance and motivation after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The two specific objectives of the research are:

1. To determine whether digital math SEGs improve math performance.

2. To examine students’ motivation after using digital math SEGs.

The three research questions for this study are:

1. Does the use of digital math Serious Educational Games (SEGs) improve the mathematics performance of sixth-grade students with learning difficulties, particularly in first-degree equations?

2 .How does the use of digital math SEGs impact the motivation of sixth-grade students with learning difficulties in mathematics after the COVID-19 pandemic?

3. Does gender moderate the relationship between motivation and math performance in students using digital Serious Educational Games (SEGs) compared to traditional textbook learning?

These questions aim to investigate both the academic and motivational effects of using SEGs to support students with learning difficulties in the context of mathematics, following the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital SEGs on Mathematical Understanding and Student Motivation

Digital SEGs have emerged as a highly effective educational tool, especially in comprehending complex subjects such as mathematics. These interactive games engage students in an immersive learning experience, fostering a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts (Gee, 2003). By allowing active participation and customization to individual learning paces, SEGs provide a personalized learning environment (Anderson & Dill, 2000). This personalization is particularly crucial in catering to diverse learning needs and enhancing overall comprehension. Studies indicate that students using digital educational games show significant improvement in their mathematical skills, as evidenced by post-test results (Delgado & Mendes, 2023). The interactive nature of these games provides immediate feedback, which is crucial for learning complex mathematical concepts. Gamification elements in SEGs have been shown to stimulate student engagement and motivation, leading to improved performance (Lampropoulos & Sidiropoulos, 2024).

Moreover, SEGs promote experiential learning by encouraging students to experiment with various problem-solving approaches in a risk-free environment (Steinkuehler & Duncan, 2008). This approach can significantly contribute to a comprehensive understanding of mathematical principles. Additionally, research suggests that digital SEGs can enhance memory retention, understanding, and logical reasoning, all of which are essential components of mastering mathematics (Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 1994).

Recent studies further support these findings. Zainuddin et al. (2020) highlighted that digital SEGs are particularly effective in enhancing mathematical comprehension by providing instant feedback and encouraging active participation. Naul and Liu (2020) demonstrated that incorporating storytelling and narrative elements in SEGs can enhance mathematical understanding by contextualizing abstract concepts. Moreover, Hussein et al. (2022) illustrated how digital SEGs significantly improved students’ problem-solving skills in mathematics. Zhao et al. (2021) showed the positive impact of SEGs on students’ attitudes and motivation towards learning mathematics. Research identifies several reasons why digital SEGs are beneficial for comprehending mathematics:

1. Creative Learning: SEGs stimulate creative thinking and imagination, enabling players to explore multiple solutions to mathematical problems, thus improving their skills (Anderson & Dill, 2000).

2. Fun Learning: The enjoyable nature of SEGs makes learning mathematics a pleasant experience, motivating players to persistently attempt challenges and compete with themselves (Gee, 2003).

3. Experiential Learning: SEGs offer an experiential platform where players can immerse themselves in mathematical concepts and apply their knowledge in real-life scenarios, facilitating a deeper level of understanding (Clark et al., 2016).

4. Interactive Learning: The interactivity inherent in SEGs engages players actively in the learning process, aiding in the assimilation and comprehension of mathematical principles (Hamari, Koivisto, & Sarsa, 2014).

5. Social Learning: SEGs, whether played individually or in groups, encourage social interaction and collaborative learning, enriching the educational experience (Zheng et al., 2021).

6. Increased Motivation: SEGs are designed to offer rewards, incentives, and a sense of progression, effectively enhancing motivation and engagement among learners (Arosquipa Lopez et al., 2023).

2.2. Gender Differences

Digital games have emerged as a significant tool in math learning, revealing notable gender differences in engagement and outcomes. Research indicates that, while boys and girls generally perform similarly in digital game-based learning (DGBL), distinct patterns emerge across different grade levels and contexts. Boys typically engage more frequently with video games, which can enhance their digital skills and self-efficacy compared to girls (Scholes et al., 2022). For example, in a study involving primary school learners, girls showed lower self-efficacy in third grade but improved significantly post-intervention, suggesting that DGBL may enhance their cognitive engagement more than boys (Zhang et al., 2024).

Female students also consistently outperformed males in learning outcomes when using specific game features, such as prompted self-explanation, indicating a deeper cognitive engagement with the material (McLaren, 2022; Nguyen et al., 2022). Furthermore, girls exhibited higher intrinsic motivation improvements in DGBL settings, particularly in younger grades, while boys did not show significant changes (Zhang et al., 2024). Female students also engaged less in “gaming the system,” a behavior linked to disengagement, which positively correlated with their learning outcomes (Baker et al., 2024).

Emotional expressions during gameplay revealed that girls experienced more frustration, which could impact their learning experience (Zhang et al., 2024). Conversely, while DGBL shows promise in bridging gender gaps, it is essential to recognize that boys may still engage more with digital games overall, potentially influencing their learning experiences differently (Gunawardhana, 2021).

3. Methodology

The research is empirical with the questionnaire/test as a tool.

3.1. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for this study integrates several educational and psychological theories that support the use of digital educational tools, such as the “Battleship” game, to teach mathematical concepts—specifically first-degree equations. This framework combines cognitive learning theories, motivational theories, and technology’s impact on education. These theories are particularly relevant to understanding the role of Serious Educational Games (SEGs) in promoting student engagement, enhancing motivation, and improving learning outcomes in mathematics (

Table 1).

1. Constructivist Learning Theory (Piaget, 1972)

Constructivist theories suggest that learners construct knowledge actively through hands-on interaction with their environment. This approach values problem-solving within meaningful contexts, enabling learners to develop a deeper understanding through personal experience.

2. Motivation Strategies for Learning (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990)

This model posits that motivation plays a central role in shaping learning strategies and academic performance. Motivation influences persistence, effort, and engagement in learning activities. To measure these aspects, this study adapts the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ), focusing on how digital games versus textbooks affect students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. This tool enables an analysis of whether engaging students through SEGs influences their attitudes and performance in mathematics compared to more traditional methods.

3. Game-Based Learning (GBL) (Gee, 2003)

Game-Based Learning theory highlights how interactive games can be effective educational tools by fostering student motivation and engagement. Games, through elements like challenges, rewards, and feedback, can immerse students in a learning experience that supports active participation and motivation.

3.2. Brief Description of the Game

“Battleship” is a free online game developed by Quia, USA (

https://www.quia.com/ba/24940.html). The game focuses on helping the player develop skills in solving first degree equations and has three levels of difficulty. The game starts with a short intro showing a design with five ships. Each time the player chooses a square, so does the opponent. In the event that the selected square belongs to a piece of the enemy’s naval forces, then, depending on the level, a window appears with an equation and certain options. If the player’s answer is correct, then an explosion appears on the selected square; a part that belongs to the naval force has been hit. Otherwise, in the case of an incorrect answer, a target is displayed. The process continues until all of the player’s or the system’s naval forces have been annihilated.

3.3. Participants

This study involved 104 sixth-grade students (11-12 years old), with 52 students in the Digital SEG group—25 boys (48%) and 27 girls (52%)—and 52 students in the Textbook group—24 boys (54%) and 28 girls (46%). These students were selected from four different schools in the northern sector of Attica, Greece, following a positive response from a total of seven schools that were approached through the researchers’ application to the Department of Primary Education. The selection of students was made purposefully, according to the teachers’ recommendations and their performance on the teachers’ attendance list. During the selection of the students, their prior experience with games was not considered.

3.4. Procedure

To test to what extent the “Battleship” game is more suitable than the textbook for the acquisition of knowledge related to first-degree equations, an experiment was conducted in a computer room at the participants’ elementary schools. The laboratory was dedicated to this experiment, which took place two sessions per week after the end of the school day, with the teachers also participating. The students were randomly divided into two groups. The Digital SEG group worked on the game on the computer and answered questions from a first-degree equation test formulated by the researchers according to the curriculum. The Textbook group studied the corresponding material from a typical classroom textbook and answered the same test as the Digital SEG group.

3.5. Instruments

The questionnaire consisted of three parts:

| Part |

Tasks |

Scoring |

| 1) Solve the equations |

Solve the following first-degree equations:

i. 5x = 10

ii. 4 = 2x

iii. 4x + 2 + 3x = 9

iv. -8x - 2x - 3 = 7

v. x: 5 = 3

vi. x: 2 – 11: 2 = 0

vii. 5x + 2 = -6 - 3x

viii. x + 2 = 2x + 1

ix. -5x - 7 = -5x + 10

x. x + 4 = 2x + 4

xi. x/5 = 3/9

xii. x/2 - 10/3 = 0 |

1 point for each correct answer, 0 for incorrect answers. Total points = sum of correct answers. |

| 2) Check equivalent equations |

Check which of the following equations express the same mathematical relationship as 3x = 9 (don’t solve the equations):

1) x = 3

2) x = 9 - 3

3) 6x = 18

4) 7x = 8

5) x = 9/3

6) x = 9 + 3

7) x/2 = 9/2

8) 9 = 5 + 3x

9) 9 + 8 = 3x + 8

10) 3x - 10 = 9 - 10

11) 3x - 6 = 3

12) 3x - 1 = 9 - 1 |

Points awarded based on number of correct matches:

1 point for 7 correct answers

0.5 points for 4-6 correct answers

0.25 points for 2-3 correct answers

0 points for 0-1 correct answers |

| 3) Motivational beliefs (MSLQ) |

Statements of Part A on students’ motivation, adapted from the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). |

Likert 1-7. |

In this study, statements from Part A: Motivation of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990) were used to measure students’ motivation, with adaptations made to translate and contextualize them in Greek.

Table 5 presents the adapted statements alongside their original MSLQ equivalents from the Part A of MSLQ.

The choice of the specific first-degree equations in part 1) and 2) was made in order to include in the questionnaire all the usual cases of equations encountered by students in the last two grades of the Primary education level.

A correct answer in part 1) received one point and a wrong answer zero points; the points were added up to give each student’s total score. In part 2), if the students found all the right answers (7 (correct) in total), they got 1 point, 0.5 points if they found 4-6 correct answers, 0.25 points if they found 2 or 3 correct answers and zero points if they found none or one correct answer only.

3.6. Data Analysis

Data analysis was done using SPPS statistical software (v.24) and the numerical calculations in excel 10.

4. Results

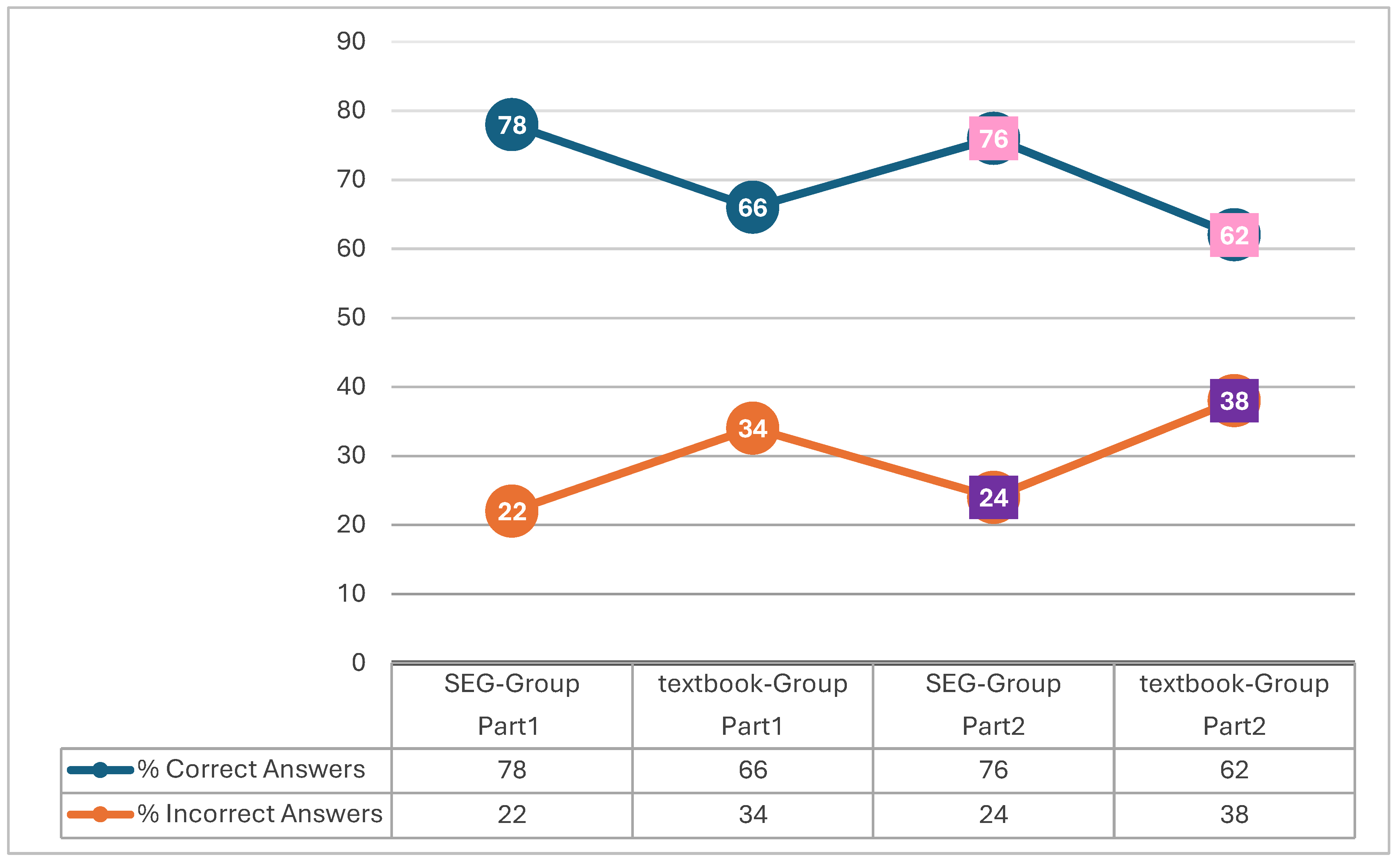

Figure 1 shows that the students who studied first grade equations using the digital SEG solved more exercises (

Section 1 &

Section 2) correctly than the students who studied first grade equations from the textbook. Specifically, in both sections, students who studied first-degree equations using the digital SEG platform exhibited higher performance compared to those who studied through the textbook: For

Section 1, there was a success rate of 78% in the SEG-Group versus 66% in the textbook-Group, and for

Section 2, a success rate of 76% in the SEG-Group compared to 62% in the textbook-Group.

4.1. Independent t-Test

According to the results of the independent t-test, students in the textbook group (M = 5.97, SD = 0.11) were more motivated to learn than students in the SEG group (M = 5.18, SD = 0.076), as shown in

Table 1. This difference is statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.00 < 0.05, indicating strong evidence against the null hypothesis. Additionally, Cohen’s d = 2.18 suggests a large effect size, according to Cohen’s (1988) criteria.

Table 3.

Independent t-test results on Students’ motivational beliefs.

Table 3.

Independent t-test results on Students’ motivational beliefs.

| Textbook Group |

SEG Group |

t(102) |

p |

Cohen’s d |

| M SD |

M SD |

10.842 |

.00* |

2.18 |

| 5.97 0.11 |

5.18 0.076 |

|

|

|

Table 5.

Chi-Square Analysis.

Table 5.

Chi-Square Analysis.

| Variable |

χ² |

df |

p |

| Part 1-Correct answers |

6.78 |

1 |

.009** |

| Part 2-Correct answers |

5.21 |

1 |

.023* |

4.2. Chi-Square

Table 5 shows that for Part 1, the p-value of 0.009 is below the 0.05 threshold, indicating a statistically significant association between the teaching method (SEG vs. textbook) and the correctness of answers. Similarly, for Part 2, the p-value of 0.023, which is also less than 0.05, further confirms a statistically significant relationship between the teaching method and the correctness of answers in this section as well.

This suggests that the type of teaching method may influence the likelihood of achieving correct answers in both parts.

4.3. Regression Model

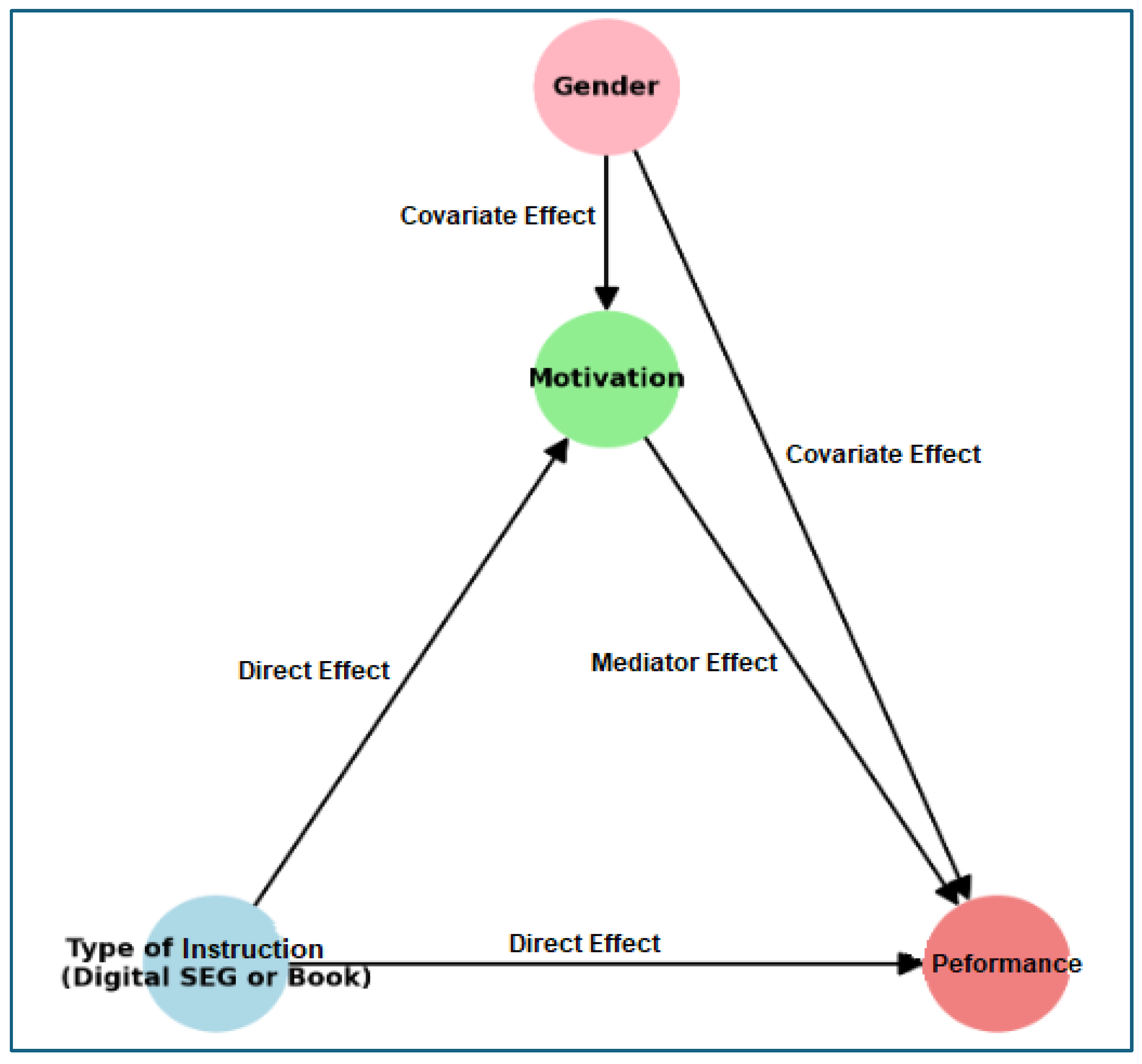

The regression model presented here aims to understand the influence of Gender and Motivation on performance. The results highlight that both variables have significant effects, though with differing magnitudes. While Gender has a statistically significant but small impact on performance, Motivation emerges as a much stronger predictor. The model provides valuable insights into how these factors contribute to explaining performance variance. Below is a detailed breakdown of the regression results (see

Table 4).

Intercept: The baseline performance when both Gender and Motivation are at zero is 5.10.

Gender: The coefficient for Gender is 0.15, suggesting a small positive effect on performance. However, it remains statistically significant (p < 0.05), as indicated by the confidence interval [0.05, 0.25]. This shows that, while small, Gender still has a statistically significant influence on performance.

Motivation: The coefficient for Motivation is 0.85, indicating that Motivation has a much stronger effect on performance. The confidence interval [0.75, 0.95] is narrow, suggesting high precision in this estimate.

sr² (Squared Semi-Partial Correlation): Motivation explains a significant portion of the variance (67%), while Gender only explains a small portion (2%).

r: The correlation for Motivation with performance is moderate to strong (r = 0.80), while Gender shows a very weak but statistically significant correlation (r = 0.10).

Fit: The overall model fits well with R² = 0.72, meaning 72% of the variance in performance is explained by both Gender and Motivation combined.

This model shows that Gender has a statistically significant, but minimal, effect on performance. Motivation, however, remains the stronger predictor.

The model is: Performance = 5.10+0.15(Gender) +0.85(Motivation) +ε

Next diagram (

Figure 2) reflects the relationships:

Type of Intervention (Digital SEG or textbook) impacts both Motivation and Performance.

Motivation is directly linked to Performance, indicating that motivation could enhance student outcomes.

Gender affects both Motivation and Performance directly.

Figure 1 provides a clearer picture of how instructional type, and gender collectively contribute to motivation and math performance, offering a holistic understanding of the influences at play.

5. Discussion

5.1. Does the Use of Digital Math Serious Educational Games (SEGs) Improve the Mathematics Performance of Sixth-Grade Students with Learning Difficulties, Particularly in First-Degree Equations?

The use of digital SEGs has increasingly been shown to enhance mathematical comprehension by fostering a dynamic, interactive learning environment (Gee, 2003). In this study, students using SEGs to practice first-degree equations outperformed those studying with traditional textbooks. Specifically, the SEG group achieved a 78% success rate in

Section 1 compared to 66% in the textbook group, and a 76% success rate in

Section 2 versus 62% for the textbook group. These findings are supported by Delgado and Mendes (2023), who reported that digital games significantly improved students’ post-test scores, especially in complex topics like algebra.

The chi-square analysis further confirmed a statistically significant association between the teaching method (SEG or textbook) and correct answers, underlining SEGs’ efficacy in mathematics. This aligns with Lampropoulos and Sidiropoulos (2024), who found that SEGs provide immediate feedback, critical for grasping challenging concepts, and facilitate personalized learning by adapting to individual students’ needs (Anderson & Dill, 2000). Additionally, Zainuddin et al. (2020) emphasized that SEGs’ narrative elements enhance engagement, aiding comprehension of abstract concepts by contextualizing them in relatable ways. Steinkuehler and Duncan (2008) also noted that experiential learning through SEGs supports improved problem-solving abilities. Overall, the evidence suggests that digital SEGs significantly impact students’ mathematical performance, particularly for those with learning difficulties.

5.2. How Does the Use of Digital Math SEGs Impact the Motivation of sixth-Grade Students with Learning Difficulties in Mathematics after the COVID-19 Pandemic?

While SEGs are widely recognized for their ability to enhance student engagement through rewards and interactive experiences (Zhao et al., 2021), this study found an interesting contrast: students in the textbook group reported higher motivation scores (M = 5.97, SD = 0.11) compared to those in the SEG group (M = 5.18, SD = 0.076). This statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 2.18) suggests that the motivational dynamics of traditional learning might differ. Arosquipa Lopez et al. (2023) highlighted that SEGs’ incentive structures can bolster motivation, but these findings raise questions about the contextual factors that might influence motivation, particularly post-pandemic.

Hamari, Koivisto, and Sarsa (2014) observed that SEGs facilitate a more interactive, personalized learning experience, which usually translates to higher motivation levels. However, this study suggests that traditional methods might sometimes appeal more strongly to students’ motivational needs. Further, Hussein et al. (2022) found that SEGs boost problem-solving engagement, yet for students recovering from the disruption of COVID-19, familiar textbook routines may offer comfort and clarity, potentially contributing to higher motivation scores in this context. Thus, while SEGs have clear performance benefits, their impact on motivation may vary based on individual student preferences and external factors, such as the post-pandemic educational landscape.

5.3. Does Gender Moderate the Relationship Between Motivation and Math Performance in Students Using Digital SEGs Compared to Traditional Textbook Learning?

In analyzing the role of gender in the relationship between motivation and performance, the regression results showed that Motivation had a more pronounced impact on performance (β = 0.80) than Gender (β = 0.10). Motivation explained a significant amount of the variance (sr² = 0.67), while Gender’s effect was smaller (sr² = 0.02). These findings align with Scholes et al. (2022), who noted that although boys and girls generally achieve similar performance outcomes in digital learning contexts, engagement patterns and motivational dynamics often differ by gender.

Moreover, Zhang et al. (2024) observed that female students tend to demonstrate greater cognitive engagement in digital learning environments, often benefiting more from game features that encourage self-reflection and problem-solving. McLaren (2022) also highlighted that girls often engage with digital games in ways that improve learning outcomes, such as through prompted self-explanation, which fosters a deeper understanding. Additionally, Nguyen et al. (2022) found that intrinsic motivation levels in digital learning environments tend to be higher among female students, especially in early grade levels. These studies suggest that while gender does play a role in SEG engagement, motivation is the primary driver of performance outcomes, with gender having a more nuanced influence.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study focused on the immediate improvement in mathematics performance and motivation for students with learning disabilities using Serious Educational Games (SEGs). However, it did not examine long-term retention of knowledge or sustained motivation. While SEGs have been shown to enhance short-term engagement and understanding (Gee, 2003), long-term retention may require more individualized support for students with disabilities. Future research could address this by assessing the lasting effects of SEGs on both performance and motivation in students with learning challenges.

Participation in this study was voluntary, which may have led to a self-selection bias. It’s possible that the participants who chose to respond were also those who were more motivated, potentially influencing the motivation results and limiting generalizability. Future studies should aim for more controlled sampling to accurately reflect the broader student population.

An unexpected finding was that students with learning disabilities using traditional methods reported higher motivation scores than those using SEGs. This raises questions about how recent shifts in learning preferences—possibly influenced by the increase in digital learning during the COVID-19 pandemic—might impact motivation for students with disabilities. Future research could examine whether these observed shifts in motivation reflect a temporary adjustment or a longer-term change in how these students engage with digital versus traditional learning methods.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Internal Ethics and Deontology Committee, Department of Special Education, University of Thessaly, approval code: 199, 23 April 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

References

- Alqahtani, R., & Kamhi, A. (2024). Feasibility and effectiveness of remote learning for students with learning disabilities during the pandemic. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 29(1). https://www.js.sagamorepub.com/index.php/ldmj/article/view/12300.

- Anderson, C. A., & Dill, K. E. (2000). Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(4), 772–790. [CrossRef]

- Arosquipa Lopez, J. Y., Nuñoncca Huaycho, R. N., Yallercco Santos, F. I., Talavera-Mendoza, F., & Rucano Paucar, F. H. (2023). The impact of serious games on learning in primary education: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 22(3), 379–395. [CrossRef]

- Baker, R. S., Richey, J. E., Zhang, J., Karumbaiah, S., Andres-Bray, J. M., Nguyen, H. A., Andres, J. M. A. L., & McLaren, B. M. (2024). Gaming the system mediates the relationship between gender and learning outcomes in a digital learning game. Instructional Science. [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. B., Tanner-Smith, E. E., & Killingsworth, S. S. (2016). Digital games, design, and learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 79–122. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Dan, N. N., Trung, L. T. B. T., Nga, N. T., & Dung, T. M. (2024). Digital game-based learning in mathematics education at primary school level: A systematic literature review. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 20(4), Article em2423. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C., & Mendes, F. (2023). Digital educational games for learning mathematics. 2023 International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE), Setúbal, Portugal, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gunawardhana, L. K. P. D. (2021). Gender differences in learning mathematics with digital games. Psychology and Education, 58(1), 4417–4422. http://psychologyandeducation.net/pae/index.php/pae/article/view/1523/1316.

- Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does gamification work? A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3025–3034. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M. H., Ow, S. H., Elaish, M. M., & Jensen, E. O. (2022). Digital game-based learning in K-12 mathematics education: A systematic literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 2859–2891. [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G., & Sidiropoulos, A. (2024). Impact of gamification on students’ learning outcomes and academic performance: A longitudinal study comparing online, traditional, and gamified learning. Education Sciences, 14(4), 367. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T., & Cheng, C.-T. (2022). Effects of Technology-Enhanced Board Game in Primary Mathematics Education on Students’ Learning Performance. Applied Sciences, 12(22), 11356. [CrossRef]

- McLaren, B. (2022). A digital learning game for mathematics that leads to better learning outcomes for female students: Further evidence. Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Games Based Learning, 16(1). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. A., Hou, X., Richey, J. E., & McLaren, B. M. (2022). The Impact of Gender in Learning With Games: A Consistent Effect in a Math Learning Game. International Journal of Game-Based Learning (IJGBL), 12(1), 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Naul, E., & Liu, M. (2020). Why Story Matters: A Review of Narrative in Serious Games. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 58(3), 687-707. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y., Ke, F., & Xu, X. (2022). A systematic review of the role of learning games in fostering mathematics education in K-12 settings. Educational Research Review, 36, 100448. [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. (1972). Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Human Development, 15(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R., & de Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Scholes, L., Rowe, L., Mills, K. A., Gutierrez, A., & Pink, E. (2022). Video gaming and digital competence among elementary school students. Learning, Media and Technology, 49(2), 200–215. [CrossRef]

- Schrader, C. (2022). Serious games and game-based learning. In Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Education (pp. 1–14). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Steinkuehler, C., & Duncan, S. (2008). Scientific habits of mind in virtual worlds. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 17(6), 530–543. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L., Ruokamo, H., Siklander, P., Li, B., & Devlin, K. (2021). Primary school students’ perceptions of scaffolding in digital game-based learning in mathematics. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 2, Article 100457. [CrossRef]

- Syakur, A., Sudrajad, W., Winurati, S., & Tilwani, S. A. (2023). The Motivation of Students and Their Exposure to Learning Loss After the Pandemic. Studies in Learning and Teaching, 4(3), 622-633. [CrossRef]

- Tepho, S., & Srisawasdi, N. (2023). Assessing Impact of Tablet-Based Digital Games on Mathematics Learning Performance. Engineering Proceedings, 38(1), Article 41. [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z., Chu, S. K. W., Shujahat, M., & Perera, C. J. (2020). The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educational Research Review, 30, 100326. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Lei, Y., Pelton, T., Pelton, L. F., & Shang, J. (2024). An exploration of gendered differences in cognitive, motivational, and emotional aspects of game-based math learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D., Muntean, C. H., Chis, A. E., & Muntean, G.-M. (2021). Learner attitude, educational background, and gender influence on knowledge gain in a serious games-enhanced programming course. IEEE Transactions on Education, 64(3), 308-316. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L. R., Oberle, C. M., Hawkes-Robinson, W. A., & Daniau, S. (2021). Serious Games as a Complementary Tool for Social Skill Development in Young People: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Simulation & Gaming, 52(6), 686-714. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).