1. Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has significantly impacted global health, originating in December 2019, with conditions resembling pneumonia [

1]. SARS-CoV-2 spread faster than SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV, reaching six continents within three months of emergence [

2,

3]. Its genome encodes four structural proteins—spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N)—with the N protein being highly immunogenic and essential for the viral replication and assembly [

4,

5]. The N protein contains RNA-binding N-terminal and C-terminal domains (NTD and CTD, respectively) by an serine-arginine (SR)-rich domain, contributing to its structural and functional versatility [

6,

7]. Anti-N antibodies are crucial for early serological detection during SARS-CoV-2 infection, with high sensitivity and persistence compared to antibodies against other structural proteins of this virus [

8,

9,

10]. RNA testing of upper respiratory samples detects viral RNA before symptom onset, peaking in the first symptomatic week [

11,

12]. Elevated RNA levels in the blood correlate with severe disease outcomes [

13]. IgG antibodies emerge 7–14 days post-symptom onset, persisting for 4–6 months, while IgA and IgM decline rapidly [

14,

15,

16]. Neutralizing antibodies suggest some immunity against reinfection, though protective thresholds remain undefined [

17,

18,

19]. A single mRNA vaccine dose elicits a robust neutralizing response in previously infected individuals, comparable to two doses in infection-naïve individuals [

20,

21,

22].

Humoral responses influence COVID-19 prognosis, with IgG1 and IgG3 dominating SARS-CoV-2 responses. IgG4 production increases after repeated mRNA vaccinations, potentially modulating immune overactivation. However, emerging evidence suggests that this increase in IgG4 levels may not be a protective mechanism; rather, it constitutes an immune tolerance mechanism to the spike protein that could promote unopposed SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication by suppressing natural antiviral responses. [

23,

24]. IgG4 responses can either be beneficial or harmful depending on the situation [

24,

25].

Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 may induce IgG4 synthesis to promote immune tolerance and evade immune surveillance [

26]. The N protein disrupts host immune responses, contributing to the inflammation and severe outcomes [

27,

28,

29]. While natural antibodies provide temporary protection, their persistence and efficacy against variants remain uncertain [

4,

30]. This study investigates anti-N antibody presence, affinity, and distribution among vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals, aiming to guide future vaccine strategies and public health efforts.

Coronaviruses are zoonotic pathogens, with bats often identified as their primary reservoir [

31]. Transmission to humans occurs via intermediate hosts, such as pangolins [

32]. SARS-CoV-2 is more infectious than SARS-CoV-1 due to its enhanced binding to the ACE2 receptor, facilitated by a distinct surface protein [

33,

34]. Unlike SARS-CoV-1, which peaks in viral load during the second week of infection, SARS-CoV-2 reaches its highest viral concentration in the upper respiratory tract within the first symptomatic week [

35]. Its spike glycoprotein features S1 and S2 subunits responsible for cell adhesion and membrane fusion [

36]. Genetic studies suggest the absence of furin-like cleavage sites in pangolin coronaviruses enhances human transmissibility [

37]. The N protein comprises 419 amino acids with three intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) and two conserved structural regions (CSRs) [

38,

39]. SARS-CoV-2 shares strong genomic similarities with MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-1, indicating evolutionary ties and shared functional characteristics [

40,

41]. The N protein is highly conserved among coronaviruses [

42,

43,

44]. Structural analysis reveals a positively charged pocket in the NTD domain, facilitating viral RNA binding and assembly [

45]. Within the SARS-CoV-2 framework, the N protein is indispensable for the viral life cycle, facilitating RNA release, replication, and virion assembly [

46,

47].

The N protein suppresses type I interferon production more effectively than SARS-CoV’s N protein, interfering with retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS) pathways [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. It prevents STAT1/2 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, blocking type I interferon responses [

49,

57]. The N protein also sequesters virus-derived double-stranded RNAs, impairing RNA-induced silencing mechanisms [

58,

59,

60]. These strategies enable SARS-CoV-2 to evade innate immunity. Higher concentrations of anti-N antibodies are associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. However, in cancer patients with persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection, lower antibody levels correlate with extended viral load duration [

66]. SARS-CoV-2 N protein-specific antibodies bind to cell surfaces and activate Fc receptor-expressing cells, affecting disease severity [

67]. While antibody levels decline during convalescence, memory B cells persist, peaking at 150 days post-infection [

68]. Maintaining B-cell memory is critical for effective control of COVID-19 [

66,

69].

SARS-CoV-2 N protein-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells play a vital role in immune responses. CD4+ T cells exhibit antigen experience and aid prolonged antibody production [

70,

71]. CD8+ T cells recognizing N protein epitopes are associated with reduced disease severity and sustained antiviral potency [

72,

73,

74]. Epitope N105-113, conserved across coronaviruses, elicits strong CD8+ T cell responses, particularly in HLA-B07 genotype individuals, highlighting its potential for vaccine design [

73,

74,

75].

IgG subclasses, distinguished by their heavy chain constant regions, play varied roles in immune responses [

76,

77,

78]. IgG1 and IgG3 dominate in mild and severe COVID-19 cases, respectively, with IgG3 declining over time [

79,

80,

81,

82]. IgG4, the least common subclass, mitigates inflammation and immune overactivation but is also implicated in autoimmune disorders [

25,

83].

Repeated administration of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines has been shown to increase IgG4 antibody levels, which are typically associated with immune tolerance and reduced pro-inflammatory responses. This immunological adaptation reflects a dynamic shift in the antibody profile with successive doses of mRNA vaccines. For instance, Buhre et al. (2023) reported that mRNA vaccines, compared to adenovirus-based vaccines, induced significantly higher levels of IgG4 antibodies over the long term, while maintaining low levels of galactosylation and sialylation in the Fc region of IgG [86]. Similarly, Hartley et al. (2023) demonstrated that a third dose of mRNA vaccines enhanced IgG4 isotype switching and improved memory B cell recognition of Omicron subvariants, a response not observed in adenovirus-primed individuals [87].

Yoshimura et al. (2024) further supported these findings by showing that repeated mRNA vaccination elicited IgG4 responses specifically targeting the spike receptor-binding domain [88]. Kiszel et al. (2023) highlighted the influence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection on IgG4 class switching, showing that previously infected individuals exhibited a more pronounced IgG4 response following mRNA vaccination [89]. Akhtar et al. (2023) noted the emergence of tolerance-inducing IgG4 antibodies after booster doses, emphasizing their anti-inflammatory potential [90]. Espino et al. (2024) provided additional evidence from Latin American populations, demonstrating a significant rise in IgG4 levels after repeated Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccinations, although these antibodies displayed limited neutralization capacity against Omicron subvariants [91].

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination promotes an IgG4-dominated response, signifying an evolving immune adaptation that balances long-term protection and immune tolerance. Understanding the mechanisms and implications of this antibody profile is critical for optimizing vaccination strategies, particularly concerning booster doses and the challenges posed by emerging variants.

Currently approved SARS-CoV-2 vaccines target spike protein, focusing on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) as a critical site for neutralization. However, mutations within the RBD have significantly reduced vaccine efficacy against variants like Omicron. First identified in late 2021, the Omicron variant exhibits a remarkable ability to evade neutralizing antibodies elicited by vaccines targeting the original Wuhan strain [92,93]. This is largely attributed to extensive mutations in the RBD, which enhance its binding affinity to the human ACE2 receptor and alter its antigenic properties, leading to immune evasion [94,95,96]. Liu et al. (2021) demonstrated that the extensive RBD mutations in Omicron reduced the binding of neutralizing antibodies, thereby diminishing the efficacy of vaccines developed against the ancestral spike protein [97]. Shah and Woo (2022) expanded on these findings, highlighting Omicron’s enhanced ACE2 binding and resistance to approved therapeutic antibodies, further emphasizing the need for updated vaccines tailored to its unique mutations [98].

Renner et al. (2024) underscored that the cross-protective efficacy of existing vaccines is significantly reduced against Omicron, pointing to the urgent need for variant-specific vaccines to maintain robust protection against emerging strains [99]. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2022) provided structural insights into Omicron’s spike mutations, showing how these changes not only improve ACE2 binding but also amplify immune evasion, making neutralization by antibodies more difficult [100].

Despite a weaker binding affinity to ACE2 compared to the Delta variant, Wu et al. (2022) noted that Omicron’s extensive mutations enable it to escape neutralizing antibodies more effectively, complicating control efforts with existing vaccines [101]. Dejnirattisai et al. (2022) emphasized the widespread neutralizing antibody escape seen with Omicron, raising concerns that prior immunity from vaccination or infection may not sufficiently protect against reinfection [102].

Finally, Planas et al. (2022) confirmed the considerable escape of Omicron from antibody neutralization [103]. Their findings emphasize the urgent need for the development of new vaccines and therapeutic strategies to combat this highly evasive variant [103]. Vaccines incorporating the N protein show promise due to its conserved T cell epitopes, eliciting robust T cell responses and offering protection against diverse SARS-CoV-2 variants [104,105,106]. Preclinical studies demonstrated the protective efficacy of N protein-based vaccines, with strong IFNγ responses and tissue-resident memory T cells observed [107,108,109]. Vaccines combining S and N proteins enhance protection against the SARS-CoV-2 variants, despite the limited neutralizing activity of N-specific antibodies [109,110]. N-specific T cells are crucial for secondary defense mechanisms, providing prolonged protection [107,108,111,112]. In vivo studies highlighted the importance of CD8+ T cells in controlling viral load and preventing weight loss after Omicron challenges [109].

The N protein of SARS-CoV-2 is a pivotal structural and functional component, crucial for viral replication, immune evasion, and pathogenesis. Anti-N antibodies and T-cell responses provide valuable insights into the immune response and vaccine development. Vaccines targeting the N protein could fill gaps left by spike protein-based vaccines, offering broader protection against variants. Further research is essential to optimize vaccine strategies, ensuring durable immunity and effective control of SARS-CoV-2 and its evolving variants.

3. Results

3.1. Total IgG in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated (X±SD)

The data from

Table 2 provide a detailed comparison of total IgG (tIgG) levels between vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals, focusing on mean values and standard deviations. In the vaccinated group, the mean tIgG levels are generally higher, indicating a stronger immune response due to vaccination. For example, Sample #1 (Female) has a mean IgG level of 2.25 (OD) with a standard deviation of 0.042, while Sample #2 (Male) has a mean of 2.336 with a standard deviation of 0.089. The range of mean values for the vaccinated group spans from 1.403 (Sample #29, Male) to 2.592 (OD) (Sample #20, Male). The standard deviation values vary, reflecting the diversity in immune response among individuals, with the SD ranging from 0.011 (Sample #5, Female) to 1.190 (Sample #29, Male). Both male and female participants are included in the vaccinated group, with no clear pattern of higher or lower tIgG levels based on gender alone.

In contrast, the non-vaccinated group generally exhibits lower mean tIgG levels, suggesting a baseline level of tIgG in the absence of vaccination. For instance, Sample #1 (Female) has a mean tIgG level of 0.5117 (OD) with a standard deviation of 0.1665, and Sample #2 (Male) has a mean of 0.7523 (OD) with a standard deviation of 0.1155. The mean values for the non-vaccinated group range from 0.5117 (Sample #1, Female) to 0.8190 (OD) (Sample #5, Female). The standard deviation values are also lower in this group, ranging from 0.0014 (Sample #15, Male) to 0.2144 (Sample #13, Female), indicating less variability in tIgG levels among non-vaccinated individuals. Similar to the vaccinated group, both males and females are represented, with no significant gender-based differences in tIgG levels.

When comparing the two groups, it is evident that vaccinated individuals tend to have higher tIgG levels on average. For example, Sample #17 (Male) in the vaccinated group has a mean IgG level of 2.451 (OD) with a standard deviation of 0.014, compared to Sample #17 (Female) in the non-vaccinated group with a mean of 0.7523 (OD) and a standard deviation of 0.1155. This finding underscores the effectiveness of vaccination in boosting the immune response. Additionally, the greater variability in tIgG levels among vaccinated individuals suggests that individual factors such as health status, genetics, and environmental influences may affect the immune response to vaccination. There is no distinct trend indicating that one gender consistently has higher or lower tIgG levels within each group.

In conclusion, the data from

Table 2 highlights the impact of vaccination on tIgG levels, demonstrating higher mean levels and greater variability in vaccinated individuals compared to non-vaccinated controls. This information is crucial for understanding the benefits of vaccination and the range of immune responses it can generate. While gender does not appear to significantly influence tIgG levels, the overall findings emphasize the importance of vaccination in promoting a stronger immune response.

3.2. Anti-N IgG1 Among Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated (X±SD)

The data presented in

Table 3 provide a detailed comparison of IgG

1 levels between vaccinated and non-vaccinated (control) individuals, with a focus on mean values and standard deviations. This comparison is essential for understanding the immune response elicited by vaccination. In the vaccinated group, the mean IgG

1 levels exhibit a wide range, from as low as 0.05 (Sample #19, Male) to as high as 2.348 (OD) (Sample #20, Male). This significant variation suggests that the immune response to vaccination can differ greatly among individuals. The standard deviation values, which range from 0.0028 (Sample #19, Male) to 0.553 (Sample #24, Male), further highlight this variability. Such differences in the spread of IgG

1 levels indicate that while some individuals may have a robust response to the vaccine, others may have a more moderate increase in IgG

1 levels. The data includes both male and female participants, but there is no clear pattern indicating that one gender consistently has higher or lower IgG

1 levels.

In contrast, the non-vaccinated (control) group shows generally lower mean IgG1 levels, ranging from 0.053 (Sample #7, Male) to 0.373 (OD) (Sample #29, Male). The standard deviation values in this group are also lower, ranging from 0.001 (Sample #7, Male) to 0.141 (Sample #24, Female), suggesting less variability in IgG1 levels among non-vaccinated individuals. This lower variability could imply a more uniform baseline level of IgG1 in the absence of vaccination. Similar to the vaccinated group, both males and females are represented, and there is no distinct trend indicating significant gender-based differences in IgG1 levels.

When comparing the two groups, it is evident that vaccinated individuals tend to have higher IgG1 levels on average. This finding underscores the effectiveness of vaccination in enhancing the immune response, as reflected by the increased IgG1 levels. Additionally, the greater variability in IgG1 levels among vaccinated individuals suggests that the vaccine elicits a diverse range of immune responses, which could be influenced by various factors such as individual health status, genetics, and environmental factors.

In conclusion, the data from

Table 3 highlights the impact of vaccination on IgG

1 levels, demonstrating higher mean levels and greater variability in vaccinated individuals compared to non-vaccinated controls. This information is crucial for understanding the benefits of vaccination and the range of immune responses it can generate. While gender does not appear to significantly influence IgG

1 levels within each group, the overall findings emphasize the importance of vaccination in promoting a stronger immune response.

3.3. Anti-N IgG2 Among Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated (X±SD)

The data in

Table 4 compares IgG

2 levels between vaccinated and non-vaccinated (control) individuals, focusing on mean values and standard deviations. For the vaccinated group, the mean IgG

2 levels range from 0.050 (Sample #2, Male) to 0.066 (OD) (Sample #8, Female), indicating a relatively narrow range of immune responses among individuals. The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.0005 (Sample #4, Female) to 0.0123 (Sample #7, Female), suggest some variability in IgG

2 levels, but not as pronounced as seen in IgG

1 levels. Both males and females are included in the vaccinated group, with no clear pattern of higher or lower IgG

2 levels based on gender alone.

In the non-vaccinated group, the mean IgG2 levels are also within a narrow range, from 0.049 (Sample #20, Male) to 0.206 (OD) (Sample #19, Female). The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.0005 (Sample #4, Female) to 0.2221 (Sample #19, Female), indicate a similar level of variability as seen in the vaccinated group. This suggests that the baseline IgG2 levels in non-vaccinated individuals are relatively consistent. Both genders are represented in this group as well, without distinct trends indicating significant gender-based differences in IgG2 levels.

Comparatively, the mean IgG2 levels in vaccinated individuals are slightly higher on average than those in non-vaccinated individuals. This suggests that vaccination may have a modest effect on increasing IgG2 levels. However, the variability in IgG2 levels is similar between the two groups, indicating that individual differences in immune response are present regardless of vaccination status.

In summary,

Table 4 shows that vaccination leads to a slight increase in IgG

2 levels compared to non-vaccinated controls, with similar variability in both groups. Gender does not appear to significantly influence IgG

2 levels within each group. This data highlights the nuanced impact of vaccination on IgG

2 levels, suggesting a modest enhancement of immune response.

3.4. Anti-N IgG3 Among Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated (X±SD)

The data in

Table 5 compares IgG

3 levels between vaccinated and non-vaccinated (control) individuals, focusing on mean values and standard deviations. For the vaccinated group, the mean IgG3 levels range from 0.047 (Sample #14, Female) to 0.0753 (OD) (Sample #18, Male), indicating a relatively narrow range of immune response among individuals. The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.0005 (Sample #13, Male) to 0.0102 (Sample #19, Male), suggest some variability in IgG

3 levels, but not as pronounced as seen in IgG

1 levels. Both males and females are included in the vaccinated group, with no clear pattern of higher or lower IgG

3 levels based on gender alone.

In the non-vaccinated group, the mean IgG3 levels are also within a narrow range, from 0.0433 (Sample #12, Female) to 0.158 (OD) (Sample #3, Female). The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.00047 (Sample #4, Female) to 0.0359 (Sample #3, Female), indicate a similar level of variability as seen in the vaccinated group. This suggests that the baseline IgG3 levels in non-vaccinated individuals are relatively consistent. Both genders are represented in this group as well, without distinct trends indicating significant gender-based differences in IgG3 levels.

Comparatively, the mean IgG3 levels in vaccinated individuals are slightly higher on average than those in non-vaccinated individuals. This suggests that vaccination may have a modest effect on increasing IgG3 levels. However, the variability in IgG3 levels is similar between the two groups, indicating that individual differences in immune response are present regardless of vaccination status.

In summary,

Table 5 shows that vaccination leads to a slight increase in IgG

3 levels compared to non-vaccinated controls, with similar variability in both groups. Gender does not appear to influence IgG3 levels within each group significantly. This data highlights the nuanced impact of vaccination on IgG3 levels, suggesting a modest enhancement of imm une response.

3.5. Anti-N IgG4 Among Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated (X±SD)

The data in

Table 6 compares IgG

4 levels between vaccinated and non-vaccinated (control) individuals, focusing on mean values and standard deviations. For the vaccinated group, the mean IgG4 levels range from 0.046 (Sample #30, Male) to 0.144 (OD) (Sample #17, Male), indicating a relatively narrow range of immune responses among individuals. The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.00047 (Samples #13, Male; #6, Male; #27, Female) to 0.00455 (Sample #14, Female), suggest some variability in IgG

4 levels, but not as pronounced as seen in IgG

1 levels. Both males and females are included in the vaccinated group, with no clear pattern of higher or lower IgG

4 levels based on gender alone.

In the non-vaccinated group, the mean IgG4 levels are also within a narrow range, from 0.043 (Sample #26, Male) to 0.058 (OD) (Samples #1, Female; #3, Female). The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.00047 (Samples #4, Female; #27, Male) to 0.00386 (Sample #3, Female), indicate a similar level of variability as seen in the vaccinated group. This suggests that the baseline IgG4 levels in non-vaccinated individuals are relatively consistent. Both genders are represented in this group as well, without distinct trends indicating significant gender-based differences in IgG4 levels.

Comparatively, the mean IgG4 levels in vaccinated individuals are slightly higher on average than those in non-vaccinated individuals. This suggests that vaccination may have a modest effect on increasing IgG4 levels. However, the variability in IgG4 levels is similar between the two groups, indicating that individual differences in immune response are present regardless of vaccination status.

When comparing IgG4 with other IgG subclasses, we observe that IgG1 shows the most significant increase post-vaccination, with mean levels ranging from 0.05 (Sample #19, Male) to 2.3477 (OD) (Sample #20, Male) in vaccinated individuals, compared to 0.053 (Sample #7, Male) to 0.373 (Sample #29, Male) in non-vaccinated individuals. The variability in IgG1 levels is also higher in vaccinated individuals, indicating a more diverse immune response. For IgG2, the mean levels in vaccinated individuals range from 0.050 (Sample #2, Male) to 0.0663 (OD) (Sample #8, Female), with a similar level of variability in both vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups. IgG3 levels show a slight increase post-vaccination, with mean levels ranging from 0.047 (Sample #14, Female) to 0.0753 (OD) (Sample #18, Male) in vaccinated individuals, and a similar variability in both groups.

Overall, the data across all IgG subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4) indicates that vaccination generally leads to an increase in IgG levels, with the most significant increase observed in IgG1. The variability in IgG levels is higher in vaccinated individuals for IgG1, suggesting a more diverse immune response. For IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4, the increases are modest, and the variability is similar between vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups. Gender does not appear to significantly influence IgG levels within each group for any of the IgG subclasses. This comprehensive comparison highlights the nuanced impact of vaccination on different IgG subclasses, emphasizing the overall enhancement of immune response post-vaccination.

3.6. Affinity of IgG1 in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated (X±SD)

The data in

Table 7 compares the affinity of IgG

1 strength between vaccinated and non-vaccinated (control) individuals for N, focusing on mean values and standard deviations. For the vaccinated group, the mean affinity of IgG

1 ranges from 0.0503 (Sample #5, Female) to 0.3347 (OD) (Sample #16, Female), indicating a broad range of immune responses among individuals. The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.0005 (Sample #13, Male) to 0.0198 (Sample #20, Male), suggest some variability in IgG

1 affinity levels, but not as pronounced as seen in total IgG

1 levels. Both males and females are included in the vaccinated group, with no clear pattern of higher or lower IgG

1 affinity based on gender alone.

In the non-vaccinated group, the mean affinity of IgG1 ranges from 0.0457 (Samples #6, Female; #23, Female) to 0.2763 (OD) (Sample #2, Male). The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.0008 (Sample #6, Female) to 0.0109 (Sample #2, Male), indicate a similar level of variability as seen in the vaccinated group. This suggests that the baseline affinity of IgG1 in non-vaccinated individuals is relatively consistent. Both genders are represented in this group as well, without distinct trends indicating significant gender-based differences in IgG1 affinity.

Comparatively, the mean affinity of IgG1 in vaccinated individuals is generally higher than in non-vaccinated individuals. This suggests that vaccination may enhance the affinity of IgG1, leading to a more effective immune response. However, the variability in IgG1 affinity is similar between the two groups, indicating that individual differences in immune response are present regardless of vaccination status.

3.7. Affinity of IgG2 in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated (X±SD)

The data in

Table 8 compares the affinity of IgG

2 strength between vaccinated and non-vaccinated (control) individuals for N, focusing on mean values and standard deviations. For the vaccinated group, the mean affinity of IgG

2 ranges from 0.048 (Sample #13, Male) to 0.0663 (OD) (Sample #8, Female), indicating a relatively narrow range of immune responses among individuals. The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.00047 (Samples #4, Female; #6, Male) to 0.00287 (Sample #1, Female), suggest some variability in IgG

2 affinity levels, but not as pronounced as seen in total IgG

1 levels. Both males and females are included in the vaccinated group, with no clear pattern of higher or lower IgG

2 affinity based on gender alone.

In the non-vaccinated group, the mean affinity of IgG2 ranges from 0.0447 (Sample #22, Male) to 0.05767 (OD) (Sample #1, Female). The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.00047 (Samples #4, Female; #6, Female) to 0.00125 (Samples #2, Male; #9, Female), indicate a similar level of variability as seen in the vaccinated group. This suggests that the baseline affinity of IgG2 in non-vaccinated individuals is relatively consistent. Both genders are represented in this group as well, without distinct trends indicating significant gender-based differences in IgG2 affinity.

Comparatively, the mean affinity of IgG2 in vaccinated individuals is generally higher than in non-vaccinated individuals. This suggests that vaccination may enhance the affinity of IgG2, leading to a more effective immune response. However, the variability in IgG2 affinity is similar between the two groups, indicating that individual differences in immune response are present regardless of vaccination status.

3.8. Affinity of IgG3 in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated (X±SD)

The data in

Table 9 compares the affinity of IgG

3 strength between vaccinated and non-vaccinated (control) individuals for N, focusing on mean values and standard deviations. For the vaccinated group, the mean affinity of IgG

3 ranges from 0.045 (Sample #26, Female) to 0.06767 (OD) (Sample #7, Female), indicating a relatively narrow range of immune response among individuals. The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.00047 (Samples #4, Female; #8, Female; #17, Male) to 0.00386 (Sample #7, Female), suggest some variability in IgG

3 affinity levels, but not as pronounced as seen in total IgG

1 levels. Both males and females are included in the vaccinated group, with no clear pattern of higher or lower IgG

3 affinity based on gender alone.

In the non-vaccinated group, the mean affinity of IgG3 ranges from 0.0433 (Sample #12, Female) to 0.0633 (OD) (Sample #4, Female). The standard deviation values, ranging from 0.00047 (Samples #4, Female; #7, Male) to 0.0359 (Sample #3, Female), indicate a similar level of variability as seen in the vaccinated group. This suggests that the baseline affinity of IgG3 in non-vaccinated individuals is relatively consistent. Both genders are represented in this group as well, without distinct trends indicating significant gender-based differences in IgG3 affinity.

Comparatively, the mean affinity of IgG3 in vaccinated individuals is generally higher than in non-vaccinated individuals. This suggests that vaccination may enhance the affinity of IgG3, leading to a more effective immune response. However, the variability in IgG3 affinity is similar between the two groups, indicating that individual differences in immune response are present regardless of vaccination status.

3.9. Affinity of IgG4 in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated (X±SD)

The data in

Table 10 compares the affinity of IgG

4 strength between vaccinated and non-vaccinated (control) individuals for N, focusing on mean values (X) and standard deviations (SD). In vaccinated individuals, the mean affinity of IgG4 ranges from 0.0507 to 0.144 (OD), with the highest value observed in Sample #17 (Male) and the lowest in Sample #13 (Male). The standard deviation values for this group range from 0.00047 to 0.00455, indicating some variability in IgG4 affinity levels among vaccinated individuals. Both male and female participants are included in this group, with no clear pattern of higher or lower IgG4 affinity based on gender alone.

In non-vaccinated individuals, the mean affinity of IgG4 ranges from 0.043 to 0.058 (OD), with the highest value observed in Samples #1 and #3 (both Female) and the lowest in Sample #26 (Male). The standard deviation values for this group range from 0.00047 to 0.00386, suggesting a similar level of variability as seen in the vaccinated group. Both genders are represented in this group as well, without distinct trends indicating significant gender-based differences in IgG4 affinity. When comparing the two groups, the mean affinity of IgG4 is generally higher in vaccinated individuals compared to non-vaccinated individuals. This suggests that vaccination may enhance the affinity of IgG4, leading to a more effective immune response. However, the variability in IgG4 affinity is similar between the two groups, indicating that individual differences in immune response are present regardless of vaccination status.

The data suggests that vaccination enhances the affinity of IgG4 antibodies, which could contribute to a stronger and more effective immune response. There is no significant influence of gender on IgG4 affinity levels within each group. This comprehensive comparison highlights the impact of vaccination on IgG4 affinity and the overall enhancement of the immune response post-vaccination.

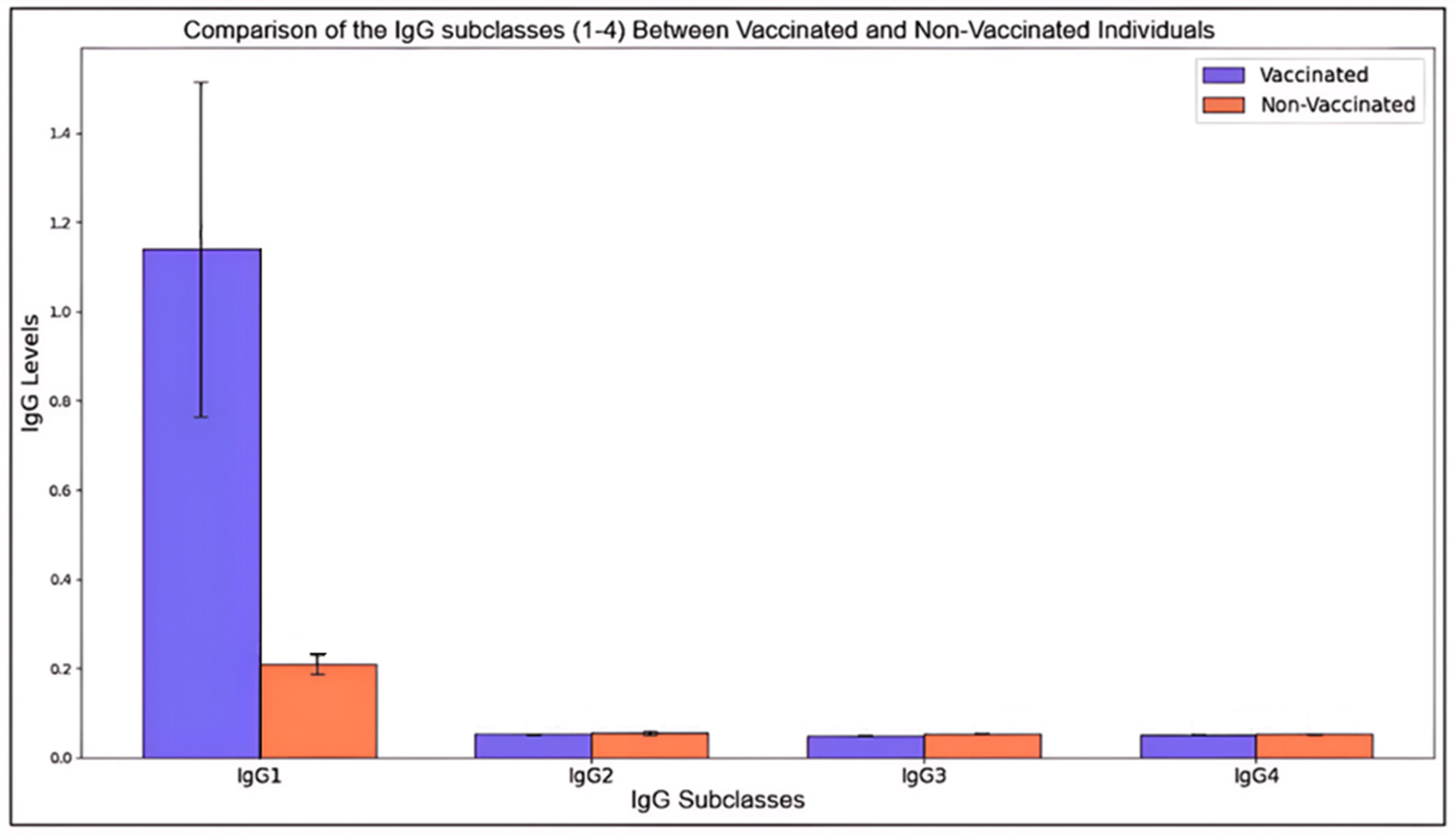

Figure 1.

Comparison of the IgG subclasses (1-4) Between Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated Individuals.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the IgG subclasses (1-4) Between Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated Individuals.

This histogram illustrates the mean levels (± standard deviation) of four IgG subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4) in vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals. Each bar represents the mean level for a given subclass, with error bars denoting standard deviations to capture variability within each group.

The immune response enhancement through vaccination is evident in IgG subclasses, where vaccinated individuals exhibit generally higher mean levels across subclasses. IgG1, often associated with a robust response, shows a notable increase in vaccinated individuals, highlighting its role in immune defense post-vaccination. The differences between vaccinated and non-vaccinated means were statistically significant (p < 0.05) across all subclasses, particularly marked in IgG1 and IgG4, suggesting that vaccination significantly boosts immune markers associated with these antibodies. Furthermore, higher standard deviations among vaccinated samples in certain subclasses suggest diverse individual immune responses, possibly due to genetic and health variability. Standard deviations within non-vaccinated groups remained relatively consistent, indicating baseline immune levels. These findings underscore the impact of vaccination on immunoglobulin levels, particularly IgG1 and IgG4, reflecting enhanced immunological readiness in vaccinated individuals.

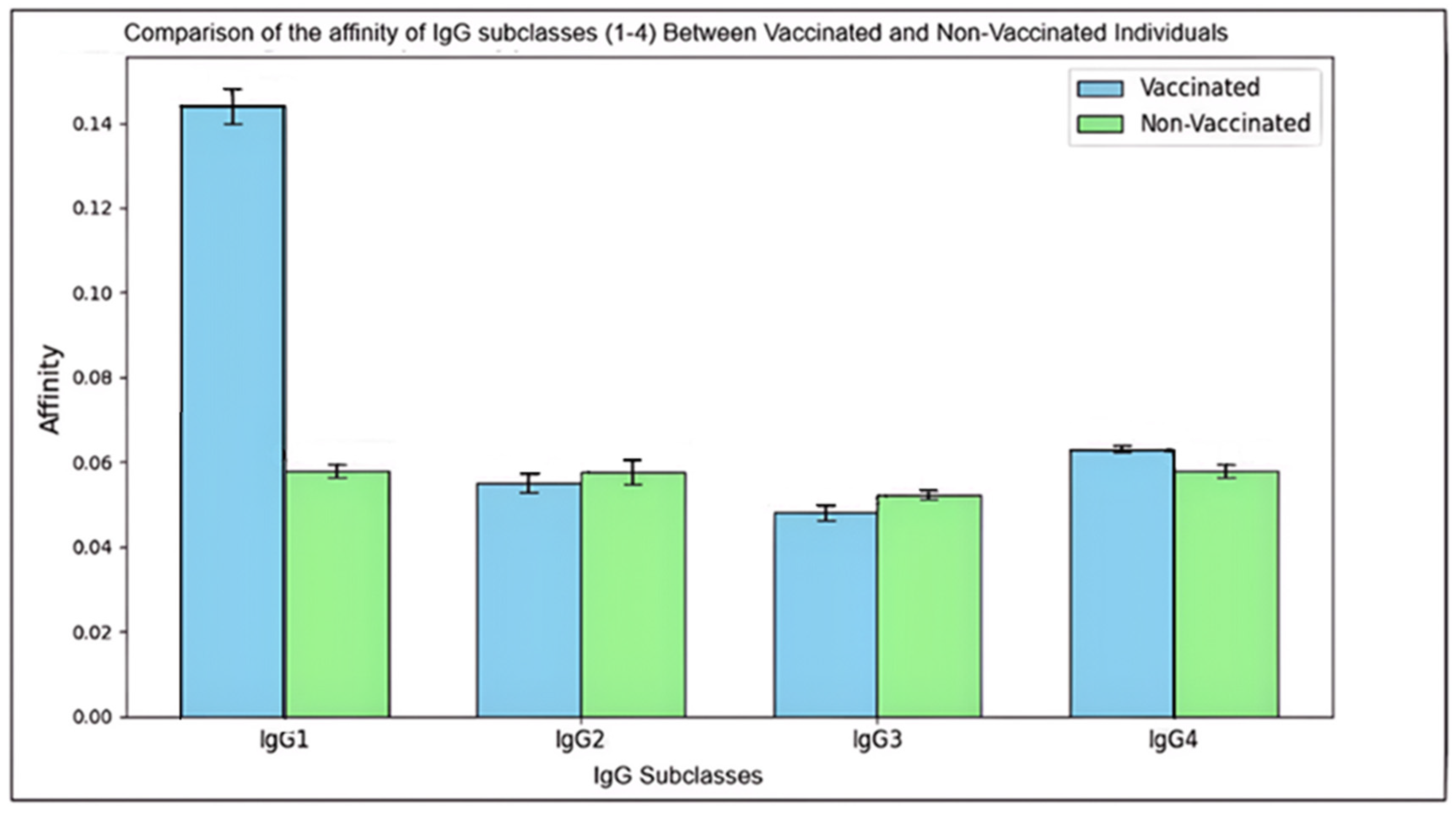

Figure 2.

Comparison of the affinity of IgG subclasses (1-4) Between Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated Individuals.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the affinity of IgG subclasses (1-4) Between Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated Individuals.

This histogram presents the mean affinity (± standard deviation) of IgG subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4) among vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals. Each bar represents the mean affinity level for a specific subclass, with error bars indicating the standard deviation to illustrate the variability within each group.

The affinity of antibodies indicating the strength of their binding to pathogens differs notably between vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups, reflecting the influence of vaccination on immune response quality. Vaccinated individuals exhibit higher mean affinities, particularly in IgG1 and IgG4, which are statistically significant (p < 0.05). This increase in affinity suggests that vaccination promotes a more effective immune response, enhancing the antibodies’ ability to neutralize pathogens more efficiently. Notably, IgG1 shows the most substantial improvement, supporting its role as a primary mediator in the immune response post-vaccination.

In addition, the vaccinated group’s greater standard deviations across subclasses imply a diverse immune response influenced by individual variability, such as genetics or health conditions. Conversely, the non-vaccinated group’s affinities remain consistent and lower, representing a baseline level of immunity. This comprehensive analysis emphasizes the role of vaccination in improving antibody affinity, which enhances immune system efficacy against potential infections.

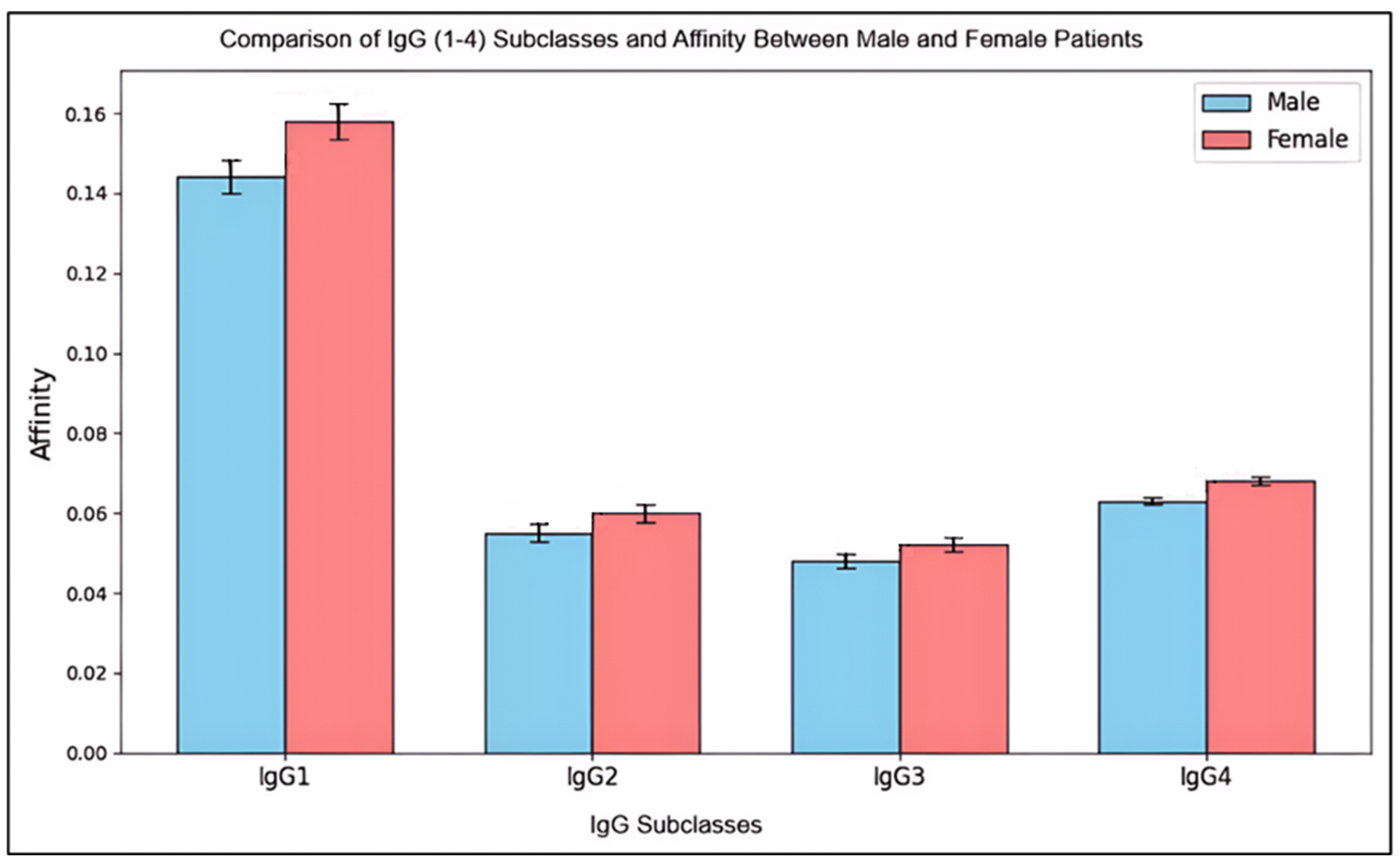

Figure 3.

Comparison of IgG (1-4) Subclasses Affinity Between Male and Female Patients.

Figure 3.

Comparison of IgG (1-4) Subclasses Affinity Between Male and Female Patients.

This histogram compares mean levels (± standard deviation) of IgG subclasses (IgG1 through IgG4) and their affinities between male and female patients. Error bars show standard deviations, capturing the spread of affinity levels within each subclass.

The results reveal slight differences in IgG subclass levels and affinities between genders, with females showing marginally higher mean levels, particularly in IgG2 and IgG4. However, these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05), suggesting that any observed variations may be due to normal biological variation rather than distinct immunological differences between male and female patients. Standard deviations indicate moderate variability within both groups, slightly higher among females in certain subclasses. This variability hints at individual immune response differences, which may result from genetic, environmental, or health-related factors rather than gender alone.

In conclusion, while females displayed a trend of marginally higher IgG levels and affinities, these findings do not imply a significant gender-based difference in immune response across IgG subclasses. The similarities in these immunological measures underscore the general consistency in IgG responses across genders in this patient group.

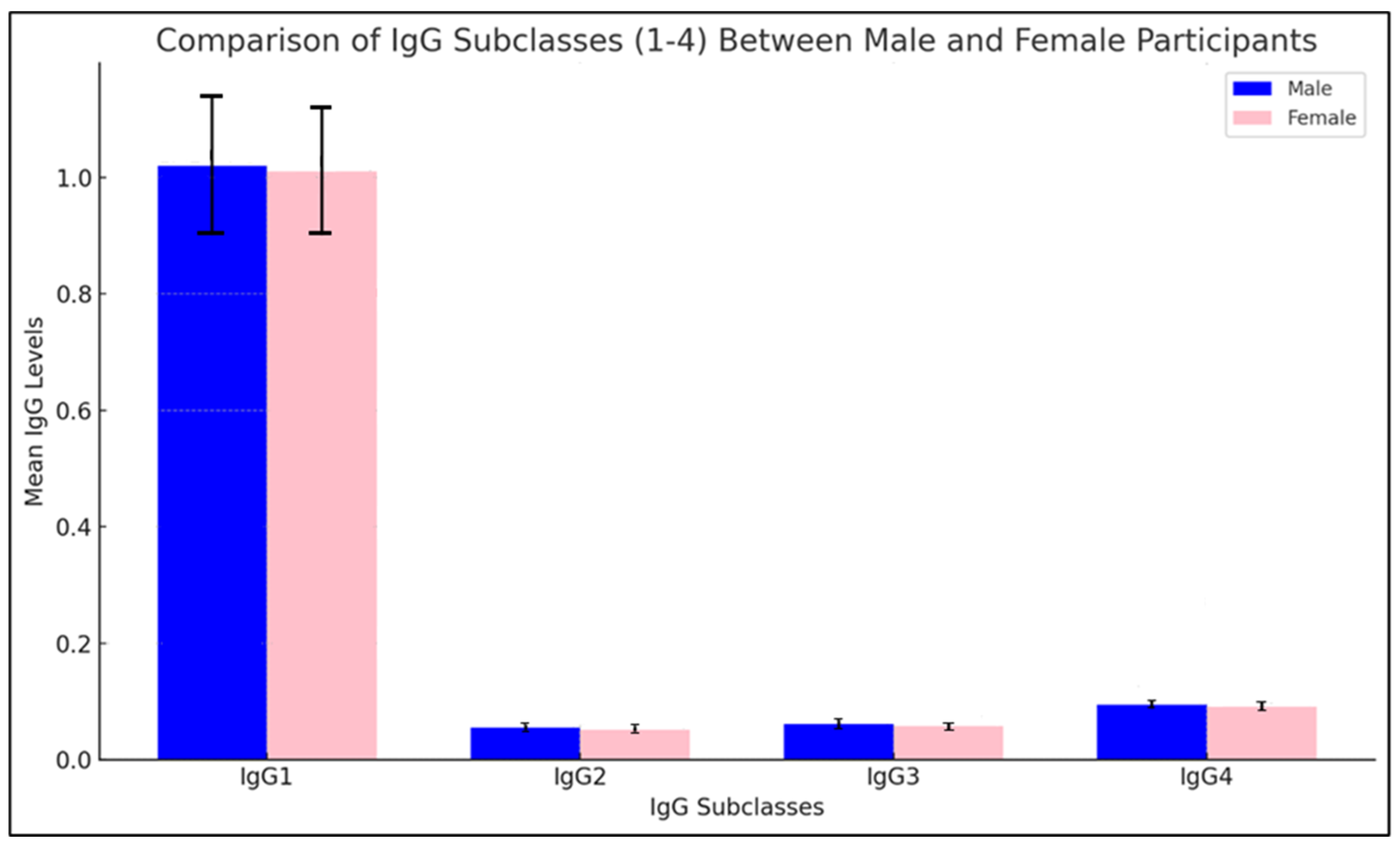

Figure 4.

Comparison of the IgG subclasses (1-4) between male and female participants.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the IgG subclasses (1-4) between male and female participants.

The histogram presents a comparative analysis of IgG subclasses (IgG1-4) between male and female participants, with mean levels displayed along with standard deviations in parentheses above each bar. IgG1 levels are slightly higher in males than in females, suggesting a possible variation in immune response for this subclass. IgG2 levels are nearly equal across genders, indicating that this subclass may exhibit a more consistent immune response, unaffected by gender-based differences. For IgG3, a minor increase in female levels is observed, while IgG4 levels are marginally higher in males.

Statistical significance testing was performed to assess these differences, and the results indicate that while some variations in IgG subclasses are visible, they are not statistically significant at a conventional threshold (p > 0.05). This lack of significant difference suggests that, for IgG subclasses in this study, gender does not substantially affect the antibody response. The consistent levels across genders, especially for IgG2 and IgG3, imply that immune response to the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 in these subclasses may be generally robust and uniform across male and female participants, irrespective of minor mean differences. This uniformity supports the idea that the immune response induced may be more influenced by external factors, such as vaccination status or antigen exposure, than by gender alone.

4. Discussion

The study on the affinity and subclasses of anti-N protein antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals provides a comprehensive analysis of the immune response dynamics. The N protein of SARS-CoV-2 is highly immunogenic and is expressed abundantly during infection [

9], making it a significant target for antibody responses. Antibodies against the N protein are detectable early in the infection and persist longer than those against other viral proteins [

8], which is crucial for understanding long-term immunity and the potential for reinfection.

IgG

4, one of the four subclasses of IgG antibodies, is known for its unique properties, including its ability to undergo Fab-arm exchange and its anti-inflammatory effects [

76]. Unlike IgG

1 and IgG

3, which are typically involved in pro-inflammatory responses, IgG

4 is associated with immune tolerance and long-term immunity [113]. The production of IgG

4 following repeated antigen exposure, such as vaccination, suggests a role in modulating the immune response to prevent overactivation and potential tissue damage.

The study revealed that vaccinated individuals exhibited higher levels of IgG

4 antibodies against the N protein compared to non-vaccinated individuals. This increase in IgG4 levels post-vaccination may be explained by hybrid immunity, a phenomenon where individuals who have both recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequently received vaccination exhibit enhanced immune responses. This aligns with the findings by Irrgang et al. [114], who reported that repeated mRNA vaccinations or breakthrough infections can boost IgG4 antibody levels, predominantly spike-specific. However, the presence of anti-N IgG4 antibodies in mRNA vaccine recipients suggests prior exposure to the N protein through natural infection, as mRNA vaccines themselves do not contain the genetic code for the N protein. [

24,110]

Several studies have explored the dynamics of IgG

4 in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination. For instance, [

23] reported a significant increase in IgG

4 levels following multiple doses of mRNA vaccines [90,115] suggesting a role in long-term immune regulation. Similarly, [

23,

24] highlighted the potential of IgG4 to induce tolerance against the spike protein, drawing parallels with allergen-specific immunotherapy, which could facilitate reinfection and other unintended consequences. The role of the N protein in modulating immune responses has also been extensively studied [

47,

49]. [

48] demonstrated that the N protein can suppress type I interferon responses, aiding in viral immune evasion. This suppression could be counteracted by the presence of high-affinity IgG

4 antibodies, which may enhance the clearance of the virus without triggering excessive inflammation [

49].

The interaction between the N protein and IgG

4 antibodies is pivotal in understanding the immune response to SARS-CoV-2. The N protein’s ability to interfere with host immune pathways, such as the RIG-I signaling pathway, underscores the importance of a balanced antibody response [

56]. IgG

4’s anti-inflammatory properties could help maintain this balance, preventing the detrimental effects of an overactive immune response while ensuring effective viral clearance.

Interestingly, Saudi Arabia’s history with the MERS coronavirus, another member of the Betacoronavirus genus, provides a unique context for this study. Prior exposure to MERS may have influenced baseline immunity in the population, potentially affecting antibody dynamics in response to SARS-CoV-2. Elevated IgG levels in some participants could reflect immunological imprinting or cross-reactivity due to previous exposure to coronaviruses. This warrants further exploration to determine if such prior exposure contributes to the observed variations in antibody responses. The findings of this study have significant implications for vaccine development and public health strategies [116]. The induction of IgG4 antibodies through vaccination could be a crucial factor in designing vaccines that not only provide protection but also minimize adverse inflammatory responses. This approach could be particularly beneficial for individuals with underlying health conditions that predispose them to severe COVID-19.

Future studies should focus on the long-term persistence of IgG4 antibodies and their protective efficacy against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants [109]. Additionally, research should explore the potential of combining N protein-based vaccines with other viral antigens to enhance the breadth and durability of the immune response.

The study also delves into the broader context of SARS-CoV-2 immunity, examining the roles of other IgG subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3) in the immune response. IgG1 and IgG3 are typically involved in pro-inflammatory responses and are crucial for pathogen neutralization. The study found that vaccinated individuals had higher levels of IgG1 and IgG3 compared to non-vaccinated individuals, indicating a robust immune response post-vaccination. IgG2 showed a slight increase in vaccinated individuals, suggesting a modest enhancement of immune response.

The study employed the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) technique to isolate and characterize these antibodies. This technique allowed us to quantify the antibodies and determine their affinity for the N protein. The analysis of antibody subclasses provided insights into the diversity of the immune response. The comparison of antibody prevalence and properties in vaccinated versus non-vaccinated individuals highlighted how vaccination status affects the immune response, particularly the response to the N protein.

The study’s methodology involved collecting venous samples from vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals, separating the sera, and using ELISA to quantify IgG antibodies and their subclasses. The results showed significant differences in antibody levels and affinities between the two groups, with vaccinated individuals exhibiting higher levels of IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4, and higher antibody affinities overall. The study also explored the impact of gender on antibody levels and affinities. While female participants generally exhibited higher IgGs levels and affinities compared to male participants, particularly in the vaccinated group, these differences were not statistically significant. This trend, though not definitive, suggests a potential for variations in immune response between genders. However, the lack of statistical significance indicates that further studies with larger sample sizes would be necessary to confirm any true gender-based differences in response to vaccination and to assess potential implications for vaccine efficacy and public health strategies.

In summary, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of the immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 N protein in vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals, highlighting the roles of IgG subclasses. IgG1 and IgG4 were the most elevated in vaccinated individuals, with IgG1 contributing to viral neutralization and IgG4, an anti-inflammatory subclass, potentially reducing immune overactivation. These findings have significant implications for vaccine strategies and public health, emphasizing the need for further research into the long-term impacts of vaccination on immunity against SARS-CoV-2.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the affinity and IgG subclasses of anti-N protein antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals. The findings highlight several key points. Vaccinated individuals generally exhibit higher levels of IgG antibodies compared to non-vaccinated individuals, with a particularly significant increase in IgG1. This suggests that vaccination effectively enhances the immune response, leading to a higher production of this antibody subclass. Among the IgG subclasses, IgG1 shows the highest increase in both anti-N antibody levels and affinity in vaccinated individuals, indicating that vaccination not only boosts the quantity of IgG1 but also enhances its quality, making it more effective in binding to antigens.

The affinity of IgG1 antibodies is significantly higher in vaccinated individuals, which points to a stronger and more effective immune response. The affinities of IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 show minor increases, with IgG2 showing the least change. This suggests that while vaccination enhances the overall immune response, its impact is most pronounced on IgG1. Additionally, female participants generally show higher IgG levels and affinities than males, especially in the vaccinated group. However, this difference is not significant. More samples are needed to confirm any gender-based differences in immune response.

The findings underscore the importance of targeting the N protein in vaccine development. The robust antibody response to the N protein, especially in vaccinated individuals, highlights its potential as a key component in future vaccines. This study’s results suggest that incorporating the N protein in vaccines could enhance their effectiveness, particularly in inducing a strong and durable immune response.

Building on these findings, several areas for future research are identified. Longitudinal studies are needed to monitor the persistence of IgG subclasses and their affinities over time in both vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals. This will provide insights into the durability of the immune response and the potential need for booster vaccinations. Expanding the study to include a more diverse population sample, considering factors such as age, ethnicity, and underlying health conditions, will help to generalize the findings and understand the immune response across different demographic groups.

Investigating the underlying mechanisms that drive the differences in antibody responses between vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals is also crucial. This includes exploring the role of different vaccine platforms and adjuvants in shaping the immune response. Further research should also explore the gender differences observed in this study to understand the biological and hormonal factors that may influence the immune response to vaccination. This could lead to more tailored vaccination strategies.

Assessing the antibody response to different SARS-CoV-2 variants, particularly focusing on the N protein, will help determine the effectiveness of current vaccines against emerging variants and guide the development of next-generation vaccines. Exploring the potential of combination vaccines that target both the S and N proteins could enhance the breadth and robustness of the immune response, providing better protection against diverse SARS-CoV-2 variants. By addressing these areas, future research can build on the current findings to enhance our understanding of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and improve vaccine strategies for better public health outcomes.