1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has a prevalence of 4% in children aged 2 to 6 years. The main risk factors in this age group include tonsillar and adenoid hypertrophy, obesity, craniofacial malformations, neurological and neuromuscular diseases, and gastroesophageal reflux [

1]. These conditions usually result in narrowed airways and reduced airflow during the night, leading to sleep fragmentation, intrathoracic pressure changes, and intermittent hypoxia that predisposes to a proinflammatory state, with hypercoagulability, increased sympathetic activity, and oxidative stress [

2].

The main long-term consequences of OSA in children are behavioral, neurocognitive, cardiovascular, and metabolic alterations [

3]. Furthermore, OSA negatively influences quality of life in children, modifying their sense of well-being and affecting their psychosocial environment [

4]. There is a need for specific validated questionnaires that are highly sensitive and capable of assessing the efficacy of interventions used to improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in children with OSA. Health professionals tend to use generic questionnaires such as the Glasgow Children's Benefit Inventory [

5] or the Youth Quality of Life Instrument [

6] in this population.

To limit symptoms associated with OSA, it is crucial to establish an early diagnosis based on several specific and generic factors. The process should begin with exhaustive history taking, including specific questionnaires, followed by a physical examination and diagnostic testing. Polysomnography is the gold standard test for diagnosing OSA [

1]. Research has also found home respiratory polygraphy to be useful for diagnosis in children and in clinical decision-making [

7].

Questionnaires designed specifically for children and adolescents are relatively recent and have distinct features compared to adult questionnaires. For these reasons, a thorough evaluation of their psychometric properties is warranted. In the OSA setting, existing questionnaires measure HRQoL though parents and caregivers. Because all were created in English-speaking settings, we have to translate and adapt them to our culture before applying them in clinical practice. This process involves several steps: checking whether the construct to be measured exists in the target culture, translating the items, and evaluating the metric and psychometric properties (validity and reliability) of the new version [

8].

Currently, there are few questionnaires designed specifically for childhood OSA. The OSA-18 (created in 2000 and subsequently adapted to and validated in Spanish) is a reliable and sensitive instrument for assessing post-treatment changes in children with this condition [

9,

10]. Another relevant questionnaire is the Pediatric Throat Disorders Outcome Test (T14), which evaluates the results of treatment in children with OSA and recurrent tonsillitis [

11].

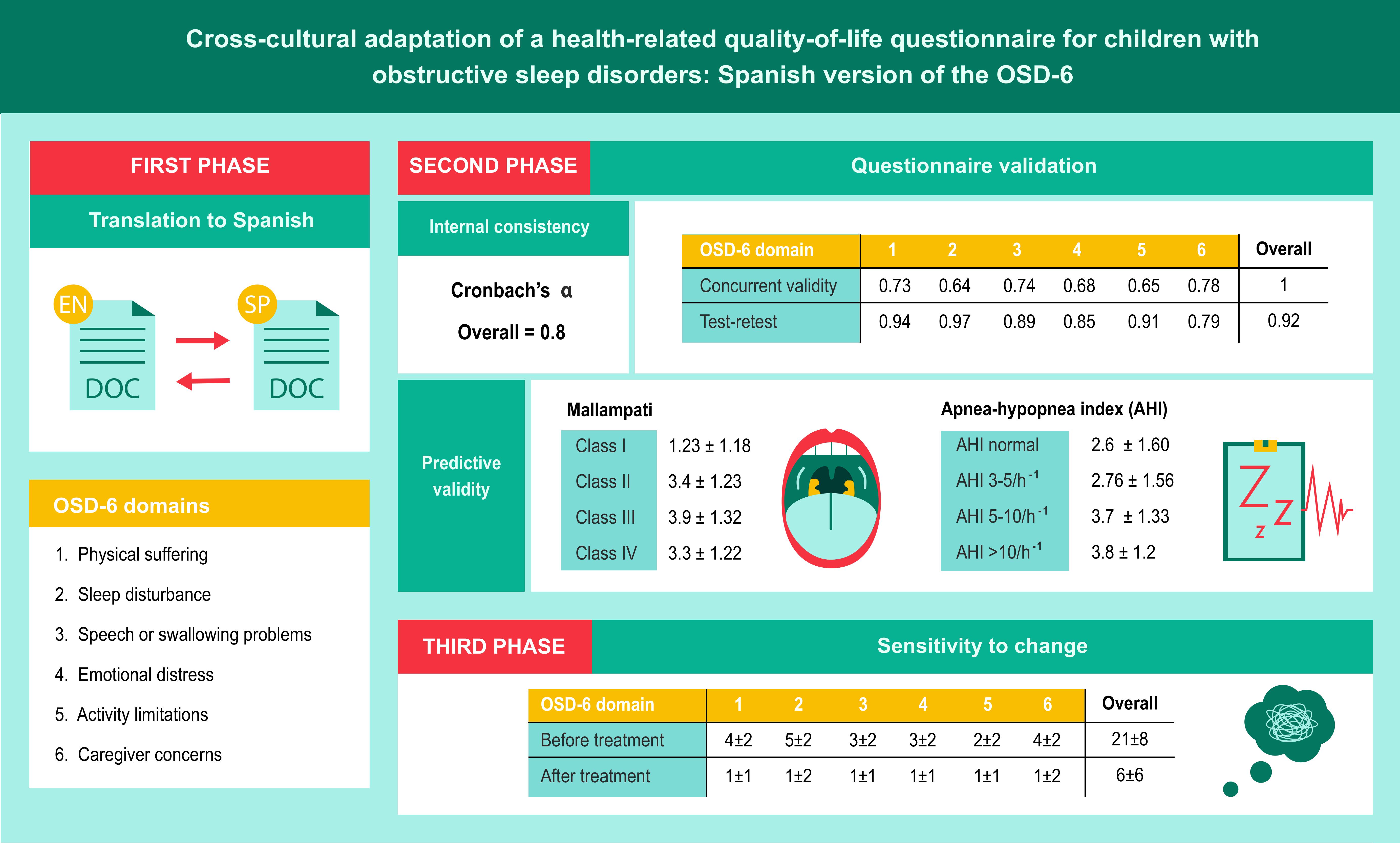

The OSD-6, created in 2000 by de Serres et al [

12], includes 6 domains that reflect the child’s functioning: physical suffering, sleep disturbance, speech or swallowing problems, emotional distress, activity limitations, and caregiver concerns related to the OSA or associated symptoms. Each domain includes a question designed to measure the overall effect of a group of OSA-related symptoms in each child. (

Figure S1).

The primary objective of our study was to adapt the original (English) version of the OSD-6 to the Spanish-speaking context. Our secondary objective was to analyze the reliability and validity of the Spanish version in the pre- and post-treatment evaluation of children with OSA.

2. Materials and Methods

To adapt the OSD-6, we followed International Test Commission guidelines [

13] and proposed guidelines for the cross-cultural adaptation of HRQoL questionnaires [

14]. The adaptation process included professional translation and back-translation and a pilot study in patients with different OSA severity [

15].

2.1. First Phase: Translation to Spanish

The original questionnaire was translated by 2 native Spanish translators with the authors’ consent. The translators and research group then discussed the resulting texts to obtain a single unified version. This questionnaire was given to parents/caregivers to check it was understandable. A native English translator then back-translated it to ensure accuracy and consistency, and we made any necessary corrections to the Spanish version. The translators assigned a score for each item to reflect the difficulty of translation and back-translation, with 1 representing minimum difficulty and 10 representing maximum difficulty. We also rated the fluency/grammatical correctness of each item of the Spanish version on a scale of 1 to 10. Finally, we graded the conceptional equivalence after the back-translation as follows: A (full equivalence), B (reasonable equivalence, a few dubious expressions), C (dubious equivalence). This new version was sent to the parents of 10 children aged 2 to 14 years with a polysomnography-based diagnosis of OSA to reach a consensus on the final questionnaire (

Figure S2).

2.2. Second Phase: Questionnaire Validation

In the second phase of the study, we assessed whether the translated questionnaire had the same psychometric properties as the original version. We evaluated the reliability or internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha for each or the scales, measuring the mean correlation coefficient of each domain with the total score from the scale and with the total number of domains. We considered between-group values above 0.4 and individual values (measuring a single dimension) greater than or equal to 0.8 to be adequate. To assess the cohesion of the instrument, we calculated the correlation between subscales and between each subscale and the total. To analyze concurrent validity (construct), we used Pearson or Spearman correlation values (depending on whether the variables followed a normal or non-normal distribution) of the different questionnaire domains globally and by subscales.

Convergent validity correlated each item with its domain, and divergent validity correlated each item with other domains. To analyze predictive validity, we compared the groups of patients with different Mallampati scores and different levels of OSA severity according to a set apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) cut-off, through a Student’s t-test for independent means. To evaluate test-retest reliability, we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between scores at baseline and after 1 week, for each domain and for the whole questionnaire, administered in the same conditions. We considered ICC values above 0.71 represented good agreement and values between 0.51 and 0.70 represented moderate agreement.

We performed a descriptive analysis of the different variables, evaluating their distribution to select the correct parametric or nonparametric statistical test. In addition, we evaluated the ceiling effect (percentage of responses with the maximum score) and floor effect (percentage with minimum score), as well as the percentage of items with no response and the percentage of nonapplicable items.

2.3. Third Phase: Sensitivity to Change

In this phase, we assessed changes in HRQoL as a result of treatment, comparing the values of all OSD-6 domains before and after treatment with a repeated measures Student t test.

Population

Inclusion criteria: age 2 to 14 years; referral to sleep unit; polysomnography-based diagnosis of OSA.

Exclusion criteria: inability to complete follow-up due to place of residence; immunosuppression (severe malnutrition, primary immunodeficiency, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]); parent refusal to participate in study; previous airway surgery or other interventions (e.g. cauterization or thermoplasty).

Diagnostic Protocol

The diagnostic protocol consisted of collecting body measurements (weight, height, body mass index [BMI], BMI percentile, neck circumference), administering the data collection questionnaire, obtaining the Mallampati score [

16] and Brodsky grade (degree of tonsillar hypertrophy), overnight polysomnography in hospital, and baseline evaluation of the OSD-6 questionnaires administered to parents or caregivers on the day of the test. After polysomnography, children considered suitable for surgical treatment were referred to the otorhinolaryngology department. We repeated the polysomnography 3 to 6 months after the surgery to assess post-treatment changes in respiratory parameters. On the same day, we collected body measurements and symptoms, and readministered the OSD-6.

Polysomnography

To establish a diagnosis, we used the Alice 5 polysomnography system (Phillips Respironics), which records electroencephalogram, electrooculogram, nasal flow (pressure-based sensor), chin electromyography (EMG), chest and abdomen movements, electrocardiogram, and EMG of both legs. We applied the criteria listed in the American Academy of Sleep Medicine to define respiratory events [

17]. The sleep technologist interpreted and manually corrected the polygraphic records. We classified OSA severity according to the AHI, as follows: mild OSA, AHI below 5/h

-1; moderate OSA, AHI of 5–10 h

-1; severe OSA, AHI above10/h

-1.

OSD-6 Questionnaire

The OSD-6 includes 35 items grouped into 6 domains: physical suffering (9 items), sleep disturbance (6 items), speech or swallowing problems (6 items), emotional distress (8 items), activity limitation (5 items) and caregiver concern (1 item). Parents rate the domains on a problem scale of 0 (none) to 6 (couldn’t be worse) to reflect how the symptoms affect their child. The total score is the sum of the scores for each domain divided by 6 (number of domains). Possible scores range from 0 to 36, and lower scores reflect a better situation.

Sample Size Calculation

With a confidence level (1-α) of 95%, 3% precision (d), a 5% approximate value of the parameter, and an expected proportion of losses (R) of 15%, we adjusted the sample size to 60 children. We estimated that we would need 20 children to determine test-retest reliability and sensitivity to change. The criterion used to estimate the sample size is based on the statistical requirements for calculating the reliability coefficient, assuming an expected value greater than or equal to 0.85, with that sample and a confidence interval of 95% for Zα/2 = 1.96.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis of the quantitative variables, which we expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and range, according to the type of distribution as determined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. As well as the calculations used to validate the questionnaires, we used repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis and multiple comparisons of means tests to assess the changes in scores for each of the domains. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. We used SPSS version 18 for the statistical analysis.

Ethical Aspects

Parents or caregivers had to give their informed consent to participate in the study. Our project complied with the fundamental principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki, the Council of Europe Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, and the UNESCO Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights; as well as the requirements established in Spanish legislation in the field of biomedical research, personal data protection, and bioethics. The research ethics committee of San Juan de Alicante University Hospital approved our study (ref. 13/311). The Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) funded this study through a scholarship (ref. 025/2014).

3. Results

We included 60 consecutive patients (45 boys and 15 girls) with a mean age of 6 (SD 3) years, a mean BMI of 18 (SD 4) kg/m2, and a mean neck circumference of 28 (SD 5) cm. Seven per cent of the sample had Brodsky grade 0, 12% had grade 1, 27% had grade 2, 45% had grade 3, and 6% had grade 4. The mean AHI established through polysomnography before treatment was 12 (SD 7) h-1. All patients underwent adenotonsillectomy.

The rating for difficulty of translation assigned by the translators was above 5 for 8 items (23%). After the back-translation, 4 items (11%) were rated reasonably equivalent (B), and 1 (3%) as having dubious equivalence (C). The research group and the translators discussed these equivalence issues and the items considered equivalent but with unnatural or grammatically incorrect wording (

Table 1).

We reached a final agreed wording for each of these items, so that all items and domains of the questionnaire achieved a score above 7/10 for fluency and correctness. This new version was administered to the parents of 10 children aged between 2 and 14 years who had been referred to the sleep unit and had a polysomnography-based diagnosis of OSA. In this way, we reached a consensus on the final version of the questionnaire (

Figure S2).

In the analysis of internal consistency or reliability, the Cronbach's alpha value of the overall questionnaire was 0.8 (excellent), with normal (or almost normal) distributions of the domains. Cronbach's alpha remained stable (0.76 to 0.78) upon removal of each domain. Internal consistency was good, although 20% of respondents selected the highest score for domains 1, 2, and 6, and 15% selected the lowest score for domains 3 and 5. In the overall questionnaire, the ceiling and floor effects were below 2%. Most correlations between items were significant (

Table 2).

When analyzing construct validity, as the questionnaire has 6 non-composite domains, we could not apply a factorial analysis to determine the similarity of the construct to the original. Concurrent validity remained stable and showed a positive correlation between all the domains (from 0.23 to 0.77), with a high correlation between the score of each domain and the overall score (from 0.65 to 0.78). We observed the lowest correlations between sleep disturbance and emotional distress (0.23), between sleep disturbance and activity limitations (0.24), and between caregiver concerns and activity limitations (0.27).

Table 3 presents the full results

.

The questionnaire showed adequate predictive validity for distinguishing between Mallampati scores (ANOVA p = 0.011), while the association between OSA-6 scores and AHI levels was borderline significant (ANOVA p = 0.069), as shown in

Table 4.

Test-retest reliability was also excellent, for the whole questionnaire and for each domain (

Table 5).

Table 6 presents the results for sensitivity to change, which was excellent in the overall score (p < 0.001) and in each domain (p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The concept of health in children and adolescents covers not only physical, psychological, and social aspects, but also their ability to carry out age-appropriate activities. The dimensions usually taken into account are related to daily activities (mobility and self-care), cognitive skills (memory, ability to concentrate and learn), emotions (positive and negative), self-perception, interpersonal relationships (with friends and family), and interaction with their environment (family cohesion, social support). Most HRQoL instruments for children use the psychometric model based on individuals’ ability to distinguish between stimuli of different intensities, with responses collected on scales (typically Likert scales).

Some sleep units use the University of Michigan Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire to screen children with suspected OSA, to rule out the need for polysomnography, or to identify symptoms [

18,

19]. However, the validated Spanish version seems to differ from the original in the questions related to daytime behavior and sleepiness, aspects that are undoubtedly very important in childhood OSA [

20]. The OSD-6 has been validated in Greek [

21] and Brazilian Portuguese [

22]. It has also been used in a series of patients in India [

23], although there is no evidence of prior validation. Similarly, in 2006, Diez-Montiel et al [

24] presented a series of children who had been evaluated with an unvalidated Spanish version of the OSD-6.

Our adaptation of the OSD-6 shows excellent internal consistency. The predictive validity is adequate, concurrent validity is moderate (though would be improved by a more balanced distribution of OSA severity, as there was a tendency to severe OSA in our sample), and sensitivity to post-treatment changes is excellent.

Our study has some limitations. Because most of the children who come to our sleep unit have been previously assessed by an otorhinolaryngologist or pediatrician, the probability of severe OSA in our participants was high, and severe cases were overrepresented in the sample. In daily practice, the severity distribution would normalize over time. Similarly, it is difficult to find children without clinically significant OSA owing to initial sampling bias with a high pretest probability of having the disease.

The main strength of our study was that we followed a systematic validation process set out in international guidelines, obtaining a Spanish version of the questionnaire that is equivalent to the original, in a sample of children who underwent polysomnography (considered the gold standard) and who were managed according to a standardized diagnostic and therapeutic protocol.

5. Conclusions

Our Spanish adaptation of the OSD-6 questionnaire can be used in Spanish-speaking countries and has similar psychometric properties to the original version. It is sensitive to post-treatment changes, shows moderate discriminative capacity for severity level, and can provide important information on the impact of childhood OSA through parents or caregivers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Original version of OSD-6.; Figure S2: Spanish version of OSD-6.

Funding

The Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) funded this study through a scholarship (ref. 025/2014).

Author Contributions Conceptualization

I.B., JN.S., V.E., E.P., MA.M., and EC.; Methodology: I.B., and E.C.; Software: MA.M., and EC.; Validation: I.B., JN.S., V.E., E.P., MA.M., and EC.; Formal Analysis: I.B., MA.M., and E.C.; Investigation: I.B., MA.M., and EC.; Resources:; Data Curation: I.B., JN.S., V.E., E.P., MA.M., and EC.; Writing: I.B., JN.S., V.E., E.P., MA.M., and E.C.; Original Draft Preparation: I.B., JN.S., V.E., E.P., MA.M., and E.C.; Writing – Review & Editing: I.B., JN.S., V.E., E.P., MA.M., and E.C.; Supervision: I.B., JN.S., V.E., E.P., MA.M., and E.C.; Project Administration: MA.M., and EC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committe of San Juan de Alicante University Hospital (ref. 13/311).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OSA |

Obstructive Sleep Apnea |

| HRQoL |

Health-related quality of life |

| T14 |

Pediatric Throat Disorders Outcome Test |

| ICC |

Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| AIDS |

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| AHI |

Apnea-Hypopnea Index |

| EMG |

Electromyography |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| SEPAR |

Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery |

References

- Vaienti, B.; Di Blasio, M.; Arcidiacono, L.; Santagostini, A.; Di Blasio, A.; Segù, M. A. narrative review on obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in paediatric population. Front Neurol. 2024, 15, 1393272. [CrossRef]

- Chiner, E.; Sancho-Chust, J.N.; Pastor, E.; Esteban, V.; Boira, I.; Castelló, C.; et al. Features of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Children with and without Comorbidities. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 2418. [CrossRef]

- Solano-Pérez, E.; Coso, C.; Castillo-García, M.; Romero-Peralta, S.; Lopez-Monzoni, S.; Laviña, E.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Sleep Apnea in Children: A Future Perspective Is Needed. Biomedicines. 2023, 11, 1708. [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, M.; Duggins, A.L.; Cohen, A.P.; Ishman, S.L. Comparison of Patient- and Parent-Reported Quality of Life for Patients Treated for Persistent Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018, 159, 789-795. [CrossRef]

- Kubba, H.; Swan, I.R.; Gatehouse, S. The Glasgow Children's Benefit Inventory: a new instrument for assessing health-related benefit after an intervention. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004, 113, 980-6. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.C.; Huebner, C.E.; Connell, F.A.; Patrick, D.L. Adolescent quality of life, part I: conceptual and measurement model. J Adolesc. 2002, 25, 275-86. [CrossRef]

- Chiner, E.; Cánovas, C.; Molina, V.; Sancho-Chust, J.N.; Vañes, S.; Pastor, E.; et al. Home Respiratory Polygraphy is Useful in the Diagnosis of Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2020, 9, 2067. [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A.; et al. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005, 8, 94-104. [CrossRef]

- Franco, R.A Jr.; Rosenfeld, R.M.; Rao, M. Quality of life for children with obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000, 123, 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Chiner, E.; Landete, P.; Sancho-Chust, J.N.; Martínez-García, M.Á.; Pérez-Ferrer, P.; Pastor, E.; et al. Adaptation and Validation of the Spanish Version of OSA-18, a Quality of Life Questionnaire for Evaluation of Children with Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016, 52, 553-559. [CrossRef]

- Hogg, E.S.; Hampton, T.; Wright, K.; Sharma, S.D. The effect on the T-14 paediatric throat disorders outcome score of delaying adenotonsillectomy surgery due to COVID-19. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2023, 105, S18-S21. [CrossRef]

- de Serres, L.M.; Derkay, C.; Astley, S.; Deyo, R.A.; Rosenfeld, R.M.; Gates, G.A. Measuring quality of life in children with obstructive sleep disorders. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000, 126, 1423-9. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A.; Hidalgo, M.D.; Hambleton, R.K.; Gómez-Benito, J. International Test Commission guidelines for test adaptation: A criterion checklist. Psicothema. 2020, 32, 390-398. [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, F.; Bombardier, C.; Beaton, D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993, 46, 1417-32. [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Lonner WJ, Berry W, editors. Field methods in cross-cultural research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1986, p. 137–64.

- Liistro, G.; Rombaux, P.; Belge, C.; Dury, M.; Aubert, G.; Rodenstein, D.O. High Mallampati score and nasal obstruction are associated risk factors for obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2003, 21, 248-52. [CrossRef]

- Berry, R.B.; Budhiraja, R.; Gottlieb, D.J.; Gozal, D.; Iber, C.; Kapur, V.K.; et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012, 8, 597-619. [CrossRef]

- Chervin, R.D.; Hedger, K.; Dillon, J.E.; Pituch, K.J. Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems. Sleep Med. 2000, 1, 21-32. [CrossRef]

- Tomás Vila, M.; Miralles Torres, A.; Beseler Soto, B. Versión española del Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire . Un instrumento útil en la investigación de los trastornos del sueño en la infancia. Análisis de su fiabilidad. An Pediatr (Barc). 2007, 66, 121–8. [CrossRef]

- de Terán, T.D.; Boira, I.; Muñoz, P.; Chiner, E.; Esteban, V.; González, M. Reliability of the Paediatric Sleep Questionnaire in Patients Referred for Suspected Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Arch Bronconeumol. 2025, 61, 41-43. [CrossRef]

- Lachanas, V.A.; Mousailidis, G.K.; Skoulakis, C.E.; Papandreou, N.; Exarchos, S.; Alexopoulos, EI.; et al. Validation of the Greek OSD-6 quality of life questionnaire in children undergoing polysomnography. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 78, 1342-7. [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro, M.G.; Corrêa, C.C.; Maximino, L.P.; Weber, SAT. Sleep quality in children: questionnaires available in Brazil. Sleep Sci. 2017, 10, 154-160. [CrossRef]

- Moideen, S.P.; G.M, D.; Sheriff, R.M.; James, F. Effectiveness of Adenoidectomy as a Standalone Procedure in Improving the Quality of Life of Children with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024, 76, 2344-2350. [CrossRef]

- Díez-Montiel, A.; de Diego, J.I.; Prim, M.P.; Martín-Martínez, M.A.; Pérez-Fernández, E.; Rabanal, I. Quality of life after surgical treatment of children with obstructive sleep apnea: long-term results. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 70, 1575-9. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

First phase of questionnaire adaptation.

Table 1.

First phase of questionnaire adaptation.

| |

Difficulty of translation |

Difficulty of back-translation |

Conceptual equivalence |

Fluency/ correctness |

| Physical suffering |

1 |

1.5 |

A |

9 |

| Sore throat |

2 |

3 |

A |

9 |

| Dry throat |

2 |

2.5 |

A |

8 |

| Nasal congestion |

1 |

2.5 |

A |

8.5 |

| Completely blocked nose |

4 |

5.5 |

B |

7 |

| Bedwetting |

7 |

4 |

A |

7.5 |

| Excessive daytime tiredness |

2 |

3 |

A |

8.5 |

| Failure to gain weight |

2 |

2 |

A |

8.5 |

| Bad breath |

4 |

3 |

A |

9 |

| Overall, how much has physical suffering been a problem for your child during the past 4 weeks because of enlarged tonsils and adenoids? |

6 |

4.5 |

A |

8.5 |

| Sleep disturbance |

1 |

1 |

A |

9 |

| Snoring |

1 |

1.5 |

A |

9.5 |

| Choking/gasping for air |

4 |

3.5 |

B |

7 |

| Stopping breathing for a few seconds |

3 |

2.5 |

A |

7.5 |

| Restless sleep |

2 |

2 |

A |

9 |

| Difficult to awaken from sleep |

3 |

3 |

A |

7 |

| Overall, how much has sleep disturbance been a problem for your child during the past 4 weeks because of enlarged tonsils and adenoids? |

6 |

4.5 |

A |

9 |

| Speech or swallowing problems |

3 |

2.5 |

A |

9 |

| Difficulty swallowing certain foods |

2 |

3 |

A |

8 |

| Choking on foods |

3 |

3.5 |

A |

8 |

| Muffled speech |

4 |

3.5 |

A |

9 |

| Nasal sounding speech |

4 |

3.5 |

A |

9 |

| Poor pronunciation |

4 |

4.5 |

B |

7 |

| Overall, how much has speech or swallowing problems been a problem for your child during the past 4 weeks because of enlarged tonsils and adenoids? |

6 |

4.5 |

A |

9 |

| Emotional distress |

3 |

3.5 |

A |

8 |

| Irritable |

1 |

3 |

A |

8 |

| Frustrated |

2 |

3 |

A |

8 |

| Sad |

6 |

3.5 |

A |

9 |

| Restless |

4 |

4 |

A |

8.5 |

| Poor appetite |

3 |

4 |

A |

8.5 |

| Can’t pay attention |

3 |

4 |

A |

8 |

| Child made fun of because of snoring |

5 |

5.5 |

C |

6.5 |

| Overall, how much of a problem has emotional distress been for your child during the past 4 weeks because of enlarged tonsils and adenoids? |

6 |

5.5 |

A |

9 |

| Activity limitations |

1 |

1.5 |

A |

9 |

| Playing |

1 |

1 |

A |

9.5 |

| Participating excelling at sports |

4 |

3 |

B |

7 |

| Doing things with friends/family |

3 |

3.5 |

A |

8 |

| Attending school or day care |

3 |

3 |

A |

8.5 |

| Overall, how much have your child’s activities been limited during the past 4 weeks because of enlarged tonsils and adenoids? |

7 |

5 |

A |

9 |

| Caregiver concerns |

3 |

3 |

A |

7.5 |

| Have you, as a caregiver, been worried, concerned, or inconvenienced because of your child’s snoring and difficulty breathing at night during the past 4 weeks. |

7 |

5 |

A |

8.5 |

Table 2.

Analysis of internal consistency of the OSD-6 questionnaire.

Table 2.

Analysis of internal consistency of the OSD-6 questionnaire.

| OSD-6 domain |

No. of items |

% floor effect |

% ceiling effect |

Cronbach’s α |

| Physical suffering |

1 |

— |

20% |

0.78 |

| Sleep disturbance |

1 |

— |

20% |

0.76 |

| Speech or swallowing problems |

1 |

15% |

— |

0.76 |

| Emotional distress |

1 |

— |

— |

0.78 |

| Activity limitations |

1 |

15% |

— |

0.78 |

| Caregiver concerns |

1 |

— |

20% |

0.76 |

| Overall |

6 |

2% |

2% |

0.8 |

Table 3.

Concurrent validity of the OSD-6 questionnaire measured with Pearson correlation coefficient.

Table 3.

Concurrent validity of the OSD-6 questionnaire measured with Pearson correlation coefficient.

| OSD-6 domain |

Physical suffering |

Sleep disturbance |

Speech or swallowing problems |

Emotional distress |

Activity limitations |

Caregiver concerns |

Overall |

| Physical suffering |

1 |

0.32 |

0.50 |

0.42 |

0.37 |

0.45 |

0.73 |

| Sleep disturbance |

0.32 |

1 |

0.34 |

0.23 |

0.24 |

0.77 |

0.64 |

| Speech or swallowing problems |

0.50 |

0.34 |

1 |

0.34 |

0.32 |

0.58 |

0.74 |

| Emotional distress |

0.42 |

0.23 |

0.34 |

1 |

0.55 |

0.30 |

0.68 |

| Activity limitations |

0.37 |

0.24 |

0.32 |

0.55 |

1 |

0.27 |

0.65 |

| Caregiver concerns |

0.45 |

0.77 |

0.57 |

0.30 |

0.27 |

1 |

0.78 |

| Overall |

0.73 |

0.64 |

0.74 |

0.68 |

0.65 |

0.78 |

1 |

Table 4.

Predictive validity of OSD-6 in relation to Mallampati score and apnea-hypopnea index (AHI).

Table 4.

Predictive validity of OSD-6 in relation to Mallampati score and apnea-hypopnea index (AHI).

| |

No. of children |

Mean OSD score |

SD |

Bonferroni ANOVA p value |

| Mallampati |

|

|

|

0.011 |

| Class I |

3 |

1.23 |

1.18 |

| Class II |

27 |

3.4 |

1.23 |

| Class III |

23 |

3.9 |

1.32 |

| Class IV |

7 |

3.3 |

1.22 |

| AHI level |

|

|

|

0.069 |

| Normal |

8 |

2.6 |

1.60 |

| 3–5/h-1

|

7 |

2.76 |

1.56 |

| 5–10/h-1

|

13 |

3.7 |

1.33 |

| > 10/h-1

|

32 |

3.8 |

1.2 |

Table 5.

Analysis of test-retest repeatability.

Table 5.

Analysis of test-retest repeatability.

| OSD-6 domain |

ICC (95% CI) |

| Physical suffering |

0.94 (0.92–0.96) |

| Sleep disturbance |

0.97 (0.93–0.99) |

| Speech or swallowing problems |

0.89 (0.85–0.94) |

| Emotional distress |

0.85 (0.82–0.89) |

| Activity limitations |

0.91 (0.87–0.95) |

| Caregiver concerns |

0.79 (0.75–0.86) |

| Overall |

0.92 (0.89–0.95) |

Table 6.

OSD-6 questionnaire sensitivity to change.

Table 6.

OSD-6 questionnaire sensitivity to change.

| OSD-6 domains |

Mean score before treatment |

Mean score after treatment |

p value |

| Physical suffering |

4 (SD 2) |

1 (SD 1) |

0.001 |

| Sleep disturbance |

5 (SD 2) |

1 (SD 2) |

0.001 |

| Speech or swallowing problems |

3 (SD 2) |

1 (SD 1) |

0.001 |

| Emotional distress |

3 (SD 2) |

1 (SD 1) |

0.001 |

| Activity limitations |

2 (SD 2) |

1 (SD 1) |

0.001 |

| Caregiver concerns |

4 (SD 2) |

1 (SD 2) |

0.001 |

| Overall |

21 (SD 8) |

6 (SD 6) |

0.001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).