1. Introduction

The aging trend in the global population has led to a significant increase in the number of individuals over the age of 90. In 2024, the global population of nonagenarians was approximately 23 million and is expected to triple by 2050 [

1]. This demographic shift increases healthcare demands of elderly people, particularly in cardiovascular disease management.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) stands out as the leading cause of death among nonagenarians, with a cardiovascular disease prevalence of 24.1% and a CAD prevalence of 10.9% [

2,

3,

4]. Nonagenarians present a different risk profile for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) development compared to younger populations. Age-related atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, arterial calcification and multiple comorbidities are the main factors that trigger the development of CAD in this group [

5]. Furthermore, risk factors such as hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic renal failure are more prevalent in the older age group and many of these patients struggle with additional age-related health problems such as frailty, cognitive impairments and functional decline [

2,

6]. Compared to patients under 70 years of age with ACS, all-cause and cardiovascular mortality is 20 times higher in this group [

7].

Invasive treatment approaches for ACS in nonagenarians require careful consideration due to multiple comorbidities and frailty. However, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) stands out as an effective method to reduce mortality in this age group [

8]. Studies have shown that percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) significantly reduces mortality in this age group, with one-year mortality rates of 46% in medically treated patients compared to 24% in those receiving PCI. [

9]. In the light of this information, the rates of invasive intervention in the elderly patient group have been increasing rapidly in recent years [

10].

A more personalized, multidisciplinary approach is needed to address the unique needs of nonagenarians with ACS. These challenges, which increase with age, necessitate more clinical research for the older age group and require updating treatment guidelines for the special needs of this group [

11]. This study aims to provide a basis for both preventive health services in terms of cardiovascular disease risks during the healthy aging process and customized treatment approaches for this age group after ACS by revealing the differences between healthy controls of the same age group and patients diagnosed with ACS.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective case-control study included patients aged 90-100 years who presented to the emergency department of our hospital between January 2022 and January 2024 with chest pain and were diagnosed with ACS for the first time. ACS diagnosis was based on electrocardiographic findings and/or elevated cardiac enzymes accompanying typical chest pain within the last 12 hours. In total, 29 of 104 patients (27.9%) had persistent ST segment elevation on two consecutive ECGs and were included in the ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) group; the other 75 patients (72.1%) had ECG findings other than ST segment elevation and were included in the non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) group.

The control group was consisted of 113 healthy individuals aged 90-100 years who applied to the Internal Medicine Clinic of our hospital in the same period. Exclusion criteria were determined as the presence of known coronary artery disease, acute inflammatory, metabolic diseases, and heart failure for healthy individuals.

Hemogram parameters, glucose, HbA1c, creatinine and lipid parameters which were measured by fasting venous blood sampling at the time of admission in emergency department or on the first day of hospitalization in the ACS group. For control group blood samples collected during outpatient clinic visits were used.

Among lipid parameters, total cholesterol (TC), low density lipoprotein (LDL), triglyceride (TG), high density lipoprotein (HDL) were obtained by device measurements; Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP) was calculated by logarithmic transformation of TG/HDL ratio.

Other demographic information, height, weight and Body Mass Index (BMI) measurements, family history and smoking habits were obtained retrospectively from the hospital database. Family history was defined as coronary artery disease or sudden death in at least one first-degree relative, and smoking history was defined as current or past smoking of 20 pack/year or more. Dyslipidemia was defined as abnormal values in at least one lipid parameter: LDL≥130 mg/dL, TG≥150 mg/dL, HDL≤45 mg/dL. HT was defined as a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg and/or a diastolic pressure of 90 mmHg or more in at least two measurements and/or use of antihypertensive agents. Diabetes Mellitus (DM) was defined as hyperglycemia (fasting blood glucose≥126 mg/dL, blood glucose≥200 mg/dL during any measurement and/or HbA1c≥6.5%) confirmed by at least two measurements or known use of hypoglycemic agents. The obesity group included the group with BMI values of 30 and above.

Coronary angiographies were performed with the Judkin technique. Patients who underwent treatments to restore blood flow such as coronary stenting, balloon angioplasty or thrombolytic therapy were included in the revascularization group.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SPSS version 29.0 (SPSS Inc. IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean±standard deviation and categorical variables were expressed as percentage. Normally distributed variables between the two groups were analyzed by independent t test and non-normally distributed variables were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test. Chi square test or Fisher's Exact test was used for differences between categorical variables. Traditional risk factors were evaluated by logistic regression analyses. Lipid parameters were converted into categorical (dichotomous) variables and analyzed by logistic regression method with 3 different modelling. Hosmer-Lemeshow fit statistic was used to evaluate model fit. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A p value below 0.05 was accepted as a statistically significant difference.

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

The demographic and biochemical characteristics of the patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and healthy controls included in the study were compared in detail and summarized in

Table 1. Significant differences were observed in hemoglobin (Hgb), mean erythrocyte volume (MCV), red cell distribution width (RDW), white blood cell count (WBC), mean platelet volume (MPV), glucose and total cholesterol values in the ACS group. It was found that Hgb and MCV values were lower and RDW, WBC, MPV, glucose and total cholesterol values were higher in the ACS group compared to the healthy control group (p<0.05). In lipid profile evaluation, no statistically significant difference was observed between the groups in low density lipoprotein (LDL) levels (p>0.05). However, high density lipoprotein (HDL) levels were significantly lower in the ACS group compared to the healthy control group (p<0.001). In addition, atherogenic index (AIP) was found to be higher in the ACS group compared to the healthy control group (p<0.001). Family history was found to be higher in the healthy control group than in the ACS group and was statistically significant (45.1%, 32.0%, respectively; p=0.049).

In

Table 2, patients were classified as NSTEMI and STEMI and their demographic data, risk factors, biochemical values and outcomes were compared. Accordingly, it was noticed that among the traditional risk factors, especially family history was more common in the STEMI group (p=0.049). WBC was significantly higher in the STEMI group (p=0.03). Patients in the STEMI group underwent more CAG and PCI procedures than patients in the NSTEMI group (p<0.001). In-hospital mortality was observed in 7 of 75 patients (9.3%) in the NSTEMI group compared to 13 of 29 patients in the STEMI group and this difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). No significant difference was observed in the mean length of hospital stay between two groups.

The effects of gender, family history, smoking history, hypertension, dyslipidemia, DM and obesity, which are among the traditional risk factors, on the development of ACS were analyzed by logistic regression analyses (

Table 3). It was observed that dyslipidemia and obesity increased the risk of ACS development, but this risk was not statistically significant for obesity, whereas a significant level was measured for dyslipidemia (OR=1.953, 95% CI: 1.034-3.692, p=0.039). Contrary to expectations, the risk of ACS was found to be lower in those with a family history (OR=0.492, 95% CI: 0.264-0.917, p=0.026).

The effect of lipid parameters on the risk of ACS was evaluated by logistic regression analyses in 3 different models (

Table 4). After the variables were classified as high LDL, high TG, low HDL, high AIP, they were analyzed alone in Model 0 and a statistically significant difference was found only in the low HDL group in this model (OR= 5.534, 95%CI: 2.615-11.713, p<0.001). In Model 1, only the gender variable was added to analyze the existing parameters and a significant risk was observed only for the low HDL group (OR= 5.619, 95%CI: 2.648-11.921, p<0.001). When the model was adjusted for traditional risk factors such as gender, family history, smoking, hypertension, diabetes and obesity, in addition to the significant difference in the low HDL group (OR=5.554, 95% CI: 2.536-12.160, p<0.001), a significant increased risk was found for the high LDL group (OR=0.440, 95% CI: 0.222-0.872, p<0.019).

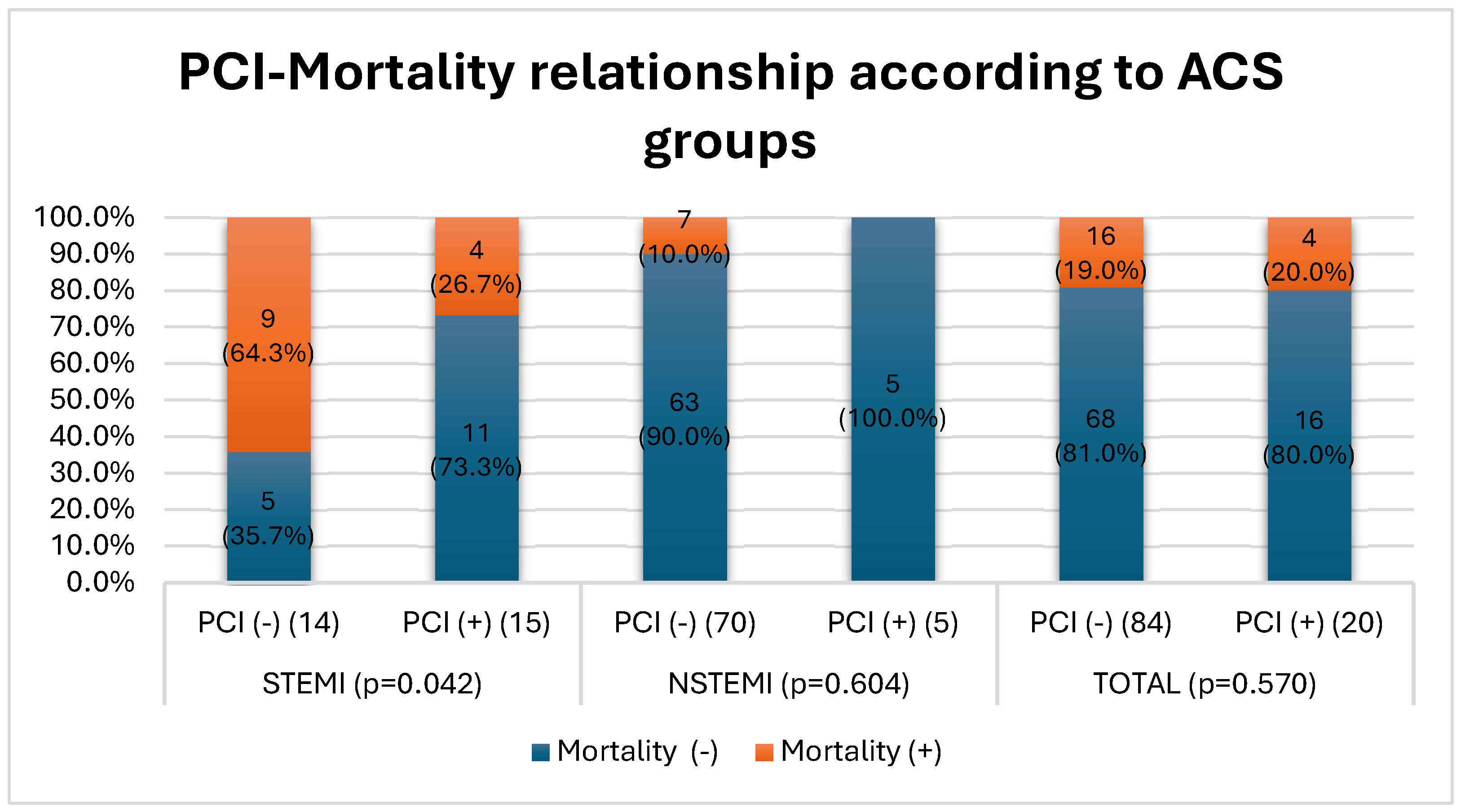

Figure 1 shows the relationship between PCI application and mortality rates in STEMI and NSTEMI groups. In the STEMI group, the mortality rate was 64.3% in patients who did not undergo PCI, whereas the mortality rate was 26.7% in patients who underwent PCI. This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.042). In the NSTEMI group, while the mortality rate was 10.0% in patients who did not undergo PCI, no mortality was observed in patients who underwent PCI (0%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.604). In the total evaluation, the mortality rate was 19.0% in patients who did not undergo PCI and 20.0% in patients who underwent PCI, and again no significant difference was observed (p = 0.570)

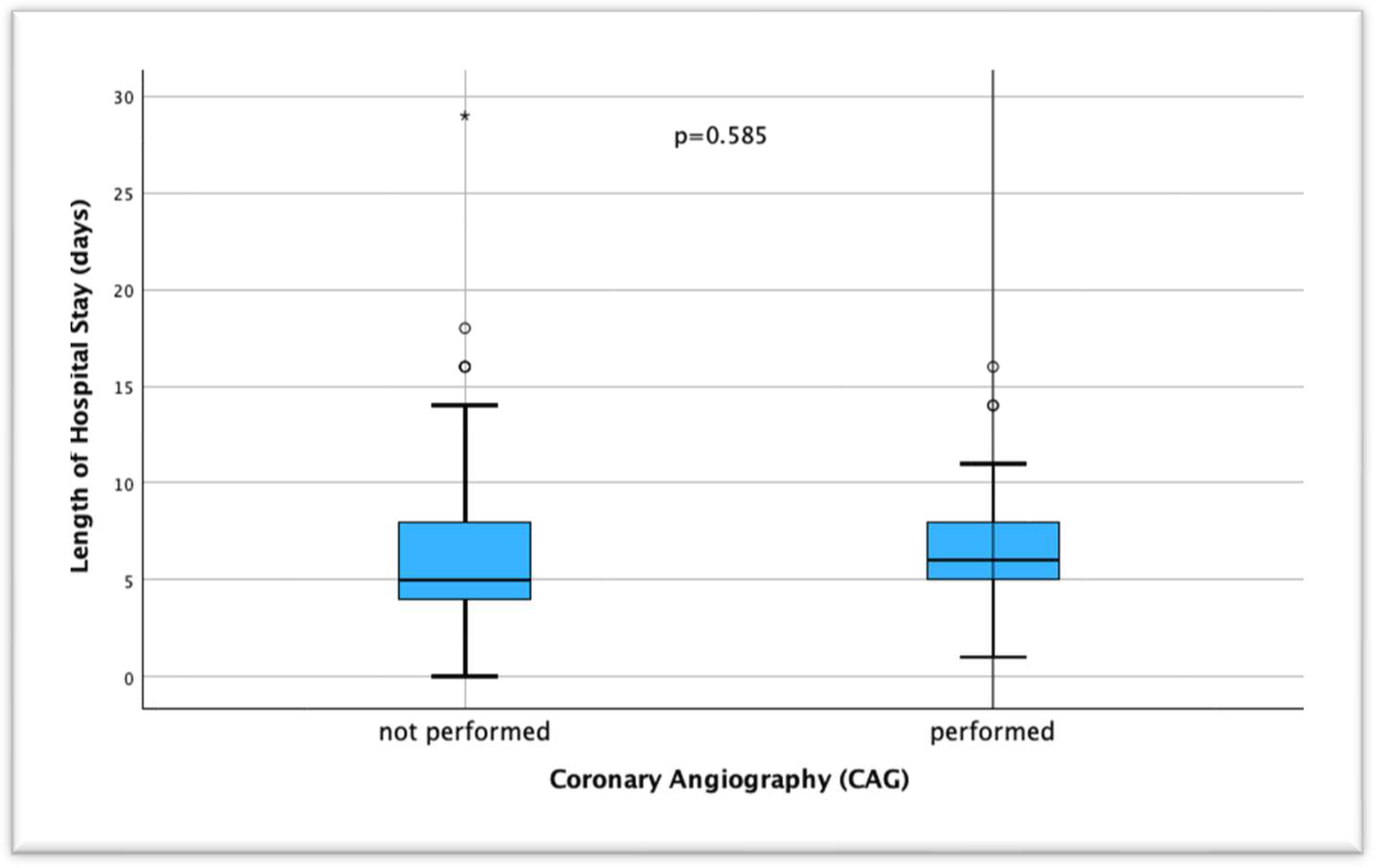

When the duration of hospitalization of patients who were interned with a diagnosis of ACS and underwent coronary angiography was compared, the mean duration was 6.68±4.45 (0-29) days in the group without coronary angiography and 6.74±3.74 (1-16) days in the group with angiography, and no significant difference was found between both groups (p=0.585) (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Risk Factors for ACS Development

In individuals over 90 years of age, the effect of classical risk factors on the development of ACS shows a different profile than in younger age groups. In the study conducted by Mostaza et al. in Madrid in 2018, comparing those with and without cardiovascular disease in the population over 90 years of age, male gender, hypertension, dyslipidemia, current smoking, presence of DM were found to be significantly different as risk factors in the group with cardiovascular disease, and no significant difference was found between BMI values [

3]. However, since more than half of the patients in this group were receiving statin therapy, a situation in favor of the cardiovascular disease group was found in atherogenic lipid parameters. Although our study does not include drug use data, it is valuable in terms of showing naive values since patients diagnosed with ACS for the first time were selected. In the GRACE study, which examined the differences in risk factors, treatment and outcomes of 24165 patients with ACS from 14 different countries according to age groups, it was revealed that factors such as DM, HT, dyslipidemia and smoking were less common in patients over 85 years of age compared to other age groups It has been shown that the male gender dominance, which reaches 80% in the group under 45 years of age, decreases to 40% over 85 years of age [

12]. This suggests that multimorbidity and chronic inflammation processes that increase with age may play a role in the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease rather than traditional risk factors [

13,

14,

15]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study with a high number of patients comparing healthy patients over 90 years of age with patients diagnosed with ACS. Therefore, we think that our study may contribute to the literature by comparing patients in the same age group without cardiovascular disease rather than the differences with other age groups. In this context, the fact that the traditional risk factors of male gender, smoking, HT and DM did not show significant differences in both groups and BMI, HbA1c and creatinine values were similar clearly reveals the etiological differences in this age group [

16,

17]. In fact, contrary to expectations, the finding that family history of coronary artery disease was higher in the control group is outside the usual scenarios. However, the fact that family history was not taken as premature cardiac or sudden death may also play a role here. In our study, we observed that dyslipidemia significantly increased the risk of ACS and this finding is consistent with the literature emphasizing the importance of lipid control in the elderly [

17,

18]. Although the study by Krumholz et al. in 1994 showed that dyslipidemia was not associated with cardiovascular risk and mortality in patients over 70 years of age, our study clearly demonstrates that especially low HDL alone constitutes a risk [

19]. However, the fact that family history reduces the risk of developing ACS differs from the general trend in the literature on younger age groups. This may be explained by the fact that genetic factors are overshadowed by comorbidities and environmental factors in older age groups [

20]. In our findings, hemoglobin and MCV values were found to be low, whereas parameters such as RDW, WBC, glucose and total cholesterol were found to be high in the ACS group. Although this difference was statistically significant when glucose values in the ACS group were analyzed in the emergency department and regardless of adequate fasting time, this limitation was not considered to have a clinical significance in the current situation since no significant difference was observed especially in comparisons related to HbA1c levels or presence of DM. Especially high RDW and WBC levels have been found to be higher in the elderly population with cardiovascular disease as a result of inflammation in the literature, and its association with mortality has been shown in the presence of ACS [

21,

22,

23].

4.2. Differences According to ACS Groups

When the patients were grouped as NSTEMI and STEMI, only family history showed a significant difference in terms of risk factors. Yayan et al. showed that only hypertension was statistically higher in the NSTEMI group between NSTEMI and STEMI groups in individuals over 90 years of age, but family history was not among the traditional risk factors [

24]. In this sense, our study is valuable in terms of emphasizing the importance of family history in ACS type.

We think that the higher leukocyte values in the STEMI group are related with the severity of inflammation. Di Stefano et al. showed that inflammatory markers such as leukocytes, high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), ferritin and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were much higher in STEMI patients than in the NSTEMI group in their study in middle-aged patients [

25]. One of the limitations of our study is that inflammatory markers other than leukocytes were not included, but the differences in leukocyte values support the existing literature.

Sugiyama et al., in their study including patients over 30 years of age between 2001 and 2011, when they analyzed PCI intervention rates according to ACS type over the years, they showed that the PCI rate was 76.6% in the STEMI group and 33.9% in the NSTEMI group by 2011 [

26]. Although our study shows similarly high rates for the STEMI group, with a PCI rate of up to 6.7% in the NSTEMI group, it reveals a much more conservative trend in this group.

Mortality rates in the STEMI group were significantly higher than in the NSTEMI group (44.8% and 9.3%, respectively). Sheldon et al. also showed that mortality was higher in the STEMI group than in the NSTEMI group and that this group especially benefited more from PCI interventions in their study including patients over 90 years of age [

27]. It was thought that the differences in mortality rates between both groups may be effective in the tendency of clinicians towards PCI.

4.3. Invasive Treatment and Mortality Reduction

In their 2008 study, From et al. showed that in-hospital mortality after PCI intervention decreased from 22% to 6% in patients over 90 years of age compared to the pre-2000s and argued that PCI should not be avoided in advanced age groups if indicated due to the increased technical success of the procedure [

28]. In our study, CAG was performed in 8 (10.7%) and PCI in 5 (6.7%) of 75 patients in the NSTEMI group, whereas in the STEMI group, CAG was performed in 19 (65.5%) and PCI in 15 (51.1%) of 29 patients (p<0.001) (

Table 2). This shows that medical treatment was the clinician's preference at a higher rate in our study, especially in the NSTEMI group. Several studies have shown that compared with younger patient groups, patients older than 90 years of age have higher short- and long-term mortality rates after PCI [

29,

30,

31]. Studies comparing ACS patients over 90 years of age with PCI and medical therapy in their own age groups have shown that in-hospital or 1-year mortality rates, MACE and all-cause mortality were lower in the PCI group [

32,

33,

34]. In our study, no significant difference was found when the relationship between PCI application and mortality in all ACS patients was analyzed (p=0.570), but when classified according to ACS subgroups, higher in-hospital mortality was observed in patients who underwent PCI, especially in the STEMI group, compared to the medical treatment arm (p=0.042) (

Figure 1). Şahin et al. and Cepas-Guillen et al. showed lower mortality rates for the STEMI group, which is similar to our study [

9,

35]. In addition, the fact that no statistically significant difference was observed between patients without and with CAG in terms of the mean duration of hospitalization may be a reason not to avoid PCI. From et al. defined a shorter hospitalization duration of 3.7 days in patients of the same age group, which is shorter than the mean duration in our study [

28]. However, we believe that especially in vulnerable patient groups with high comorbidity, there may be differences in the duration of hospitalization at the clinician's initiative to observe post-procedural complications, if any.

4.4. Limitations and Significance of the Study

In this study, demographic, biochemical and lipid profiles of patients over 90 years of age with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and healthy controls were compared in detail and the relationship between different types of ACS and risk factors was evaluated. Our findings demonstrated once again the importance of traditional risk factors in the development of ACS in the older age group, with low HDL levels being a particularly prominent risk factor. Furthermore, we observed that invasive treatment approaches were effective in reducing mortality in the STEMI group and family history played a greater role in this group compared to the NSTEMI group. As a contribution to the literature, the results emphasize the importance of personalized treatment approaches in this age group. However, our study has some limitations due to its retrospective nature. The lack of retrospective medical treatment history of the patients, the fact that the control group was selected among individuals who were admitted to the hospital and had a possible health problem, the lack of some biochemical markers (such as inflammatory markers, lipoprotein a, homocysteine, etc.), and the lack of out-of-hospital follow-up limit the generalizability of the results. In future studies, prospective studies should aim to contribute to the clinical management strategies of ACS patients in this age group.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reveals that low HDL levels are a significant risk factor for the development of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in individuals over 90 years of age, aligning with existing literature on lipid control in the elderly. However, it also highlights critical differences within the ACS group itself, emphasizing the distinct profiles of STEMI and NSTEMI patients. The findings demonstrate that family history plays a more prominent role in STEMI cases compared to NSTEMI, suggesting genetic predispositions might influence the severity of myocardial infarction in this age group. Additionally, PCI interventions showed significant benefits in reducing in-hospital mortality rates in STEMI patients, reinforcing the importance of timely and appropriate invasive treatments, even in advanced age groups.

Although PCI was not associated with significant mortality differences in the NSTEMI group, it remains a valuable therapeutic option that may improve long-term outcomes. These results suggest that ACS patients in nonagenarian populations require personalized treatment approaches that consider both their unique risk profiles and the potential benefits of invasive strategies. Clinicians should carefully assess the balance between potential procedural risks and the expected benefits, particularly in STEMI patients, who appear to benefit more substantially from PCI.

This study underscores the importance of tailoring cardiovascular care in the elderly to account for age-specific differences in disease presentation and treatment response. Future research should focus on prospective studies to further evaluate the long-term outcomes of PCI in nonagenarian ACS patients and refine guidelines for invasive procedures in this growing demographic.

References

- Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2024, Online Edition. United Nations; 2024.

- Leucker TM, Gerstenblith G, editors. Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mostaza JM, Lahoz C, Salinero-Fort MA, Cardenas J. Cardiovascular disease in nonagenarians: Prevalence and utilization of preventive therapies. Eur J Prev Cardiolog 2019;26:356–64. [CrossRef]

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;147. [CrossRef]

- Rich MW. Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Prognosis of Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Elderly. American J Geri Cardiology 2006;15:7–13. [CrossRef]

- Forman DE, Maurer MS, Boyd C, Brindis R, Salive ME, Horne FM, et al. Multimorbidity in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018;71:2149–61.

- Couture EL, Farand P, Nguyen M, Allard C, Wells GA, Mansour S, et al. Impact of an invasive strategy in the elderly hospitalized with acute coronary syndrome with emphasis on the nonagenarians. Cathet Cardio Intervent 2018;92. [CrossRef]

- Shah P, Najafi AH, Panza JA, Cooper HA. Outcomes and Quality of Life in Patients ≥85 Years of Age With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. The American Journal of Cardiology 2009;103:170–4. [CrossRef]

- Cepas-Guillén PL, Echarte-Morales J, Caldentey G, Gómez EM, Flores-Umanzor E, Borrego-Rodriguez J, et al. Outcomes of Nonagenarians With Acute Coronary Syndrome. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2022;23:81-86.e4. [CrossRef]

- Goel K, Gupta T, Gulati R, Bell MR, Kolte D, Khera S, et al. Temporal Trends and Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions in Nonagenarians. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2018;11:1872–82. [CrossRef]

- Jokhadar M. Review of the treatment of acute coronary syndrome in elderly patients. CIA 2009:435. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman FH, Cameron A, Fisher LD, Grace N. Myocardial infarction in young adults: Angiographic characterization, risk factors and prognosis (coronary artery surgery study registry). Journal of the American College of Cardiology 1995;26:654–61. [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2018;15:505–22.

- Liberale L, Montecucco F, Tardif J-C, Libby P, Camici GG. Inflamm-ageing: the role of inflammation in age-dependent cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal 2020;41:2974–82.

- García-Blas S, Cordero A, Diez-Villanueva P, Martinez-Avial M, Ayesta A, Ariza-Solé A, et al. Acute Coronary Syndrome in the Older Patient. JCM 2021;10:4132. [CrossRef]

- Kannel WB. Factors of Risk in the Development of Coronary Heart Disease—Six-Year Follow-up Experience: The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med 1961;55:33. [CrossRef]

- Kannel WB. Coronary heart disease risk factors in the elderly. The American Journal of Geriatric Cardiology 2002;11:101–7.

- Wenger NK. Dyslipidemia as a risk factor at elderly age. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 2004;13:4–9.

- Krumholz HM, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, de Leon CFM, Vaccarino V, Silverman DI, et al. Lack of association between cholesterol and coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity and all-cause mortality in persons older than 70 years. Jama 1994;272:1335–40.

- Madhavan MV, Gersh BJ, Alexander KP, Granger CB, Stone GW. Coronary artery disease in patients≥ 80 years of age. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018;71:2015–40.

- Liu X-M, Ma C-S, Liu X-H, Du X, Kang J-P, Zhang Y, et al. Relationship between red blood cell distribution width and intermediate-term mortality in elderly patients after percutaneous coronary intervention n.d.

- Xanthopoulos A, Tryposkiadis K, Dimos A, Bourazana A, Zagouras A, Iakovis N, et al. Red blood cell distribution width in elderly hospitalized patients with cardiovascular disease. WJC 2021;13:503–13. [CrossRef]

- Weijenberg MP, Feskens EJM, Kromhout D. White Blood Cell Count and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and All-Cause Mortality in Elderly Men. ATVB 1996;16:499–503. [CrossRef]

- Yayan J. Association of traditional risk factors with coronary artery disease in nonagenarians: the primary role of hypertension. Clinical Interventions in Aging 2014:2003–12.

- Di Stefano R, Di Bello V, Barsotti MC, Grigoratos C, Armani C, Dell’Omodarme M, et al. Inflammatory markers and cardiac function in acute coronary syndrome: Difference in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and in non-STEMI models. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2009;63:773–80. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama T, Hasegawa K, Kobayashi Y, Takahashi O, Fukui T, Tsugawa Y. Differential Time Trends of Outcomes and Costs of Care for Acute Myocardial Infarction Hospitalizations by ST Elevation and Type of Intervention in the United States, 2001–2011. JAHA 2015;4:e001445. [CrossRef]

- Sheldon M, Blankenship JC. STEMI in nonagenarians: Never too old. Cathet Cardio Intervent 2022;100:17–8. [CrossRef]

- From AM, Rihal CS, Lennon RJ, Holmes DR, Prasad A. Temporal Trends and Improved Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Revascularization in Nonagenarians. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2008;1:692–8. [CrossRef]

- Sawant AC, Josey K, Plomondon ME, Maddox TM, Bhardwaj A, Singh V, et al. Temporal Trends, Complications, and Predictors of Outcomes Among Nonagenarians Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 2017;10:1295–303. [CrossRef]

- Tokarek T, Siudak Z, Dziewierz A, Rakowski T, Krycińska R, Siwiec A, et al. Clinical outcomes in nonagenarians undergoing a percutaneous coronary intervention: data from the ORPKI Polish National Registry 2014–2016. Coronary Artery Disease 2018;29:573–8. [CrossRef]

- Antonsen L, Jensen LO, Terkelsen CJ, Tilsted H, Junker A, Maeng M, et al. Outcomes after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in octogenarians and nonagenarians with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: From the Western Denmark heart registry. Cathet Cardio Intervent 2013;81:912–9. [CrossRef]

- Oh S, Jeong MH, Cho KH, Kim MC, Sim DS, Hong YJ, et al. Outcomes of Nonagenarians with Acute Myocardial Infarction with or without Coronary Intervention. JCM 2022;11:1593. [CrossRef]

- Lee KH, Ahn Y, Kim SS, Rhew SH, Jeong YW, Jang SY, et al. Characteristics, In-Hospital and Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Nonagenarian Compared with Octogenarian Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients. J Korean Med Sci 2014;29:527. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y-J, Hou CJ-Y, Chou Y-S, Tsai C-H. Percutaneous coronary intervention in nonagenarians. Acta Cardiologica Sinica 2004;20:73–82.

- Sahin M, Ocal L, Kalkan AK, Kilicgedik A, Kalkan ME, Teymen B, et al. In-Hospital and long term results of primary angioplasty and medical therapy in nonagenarian patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res 2017;9:147–51. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).