Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

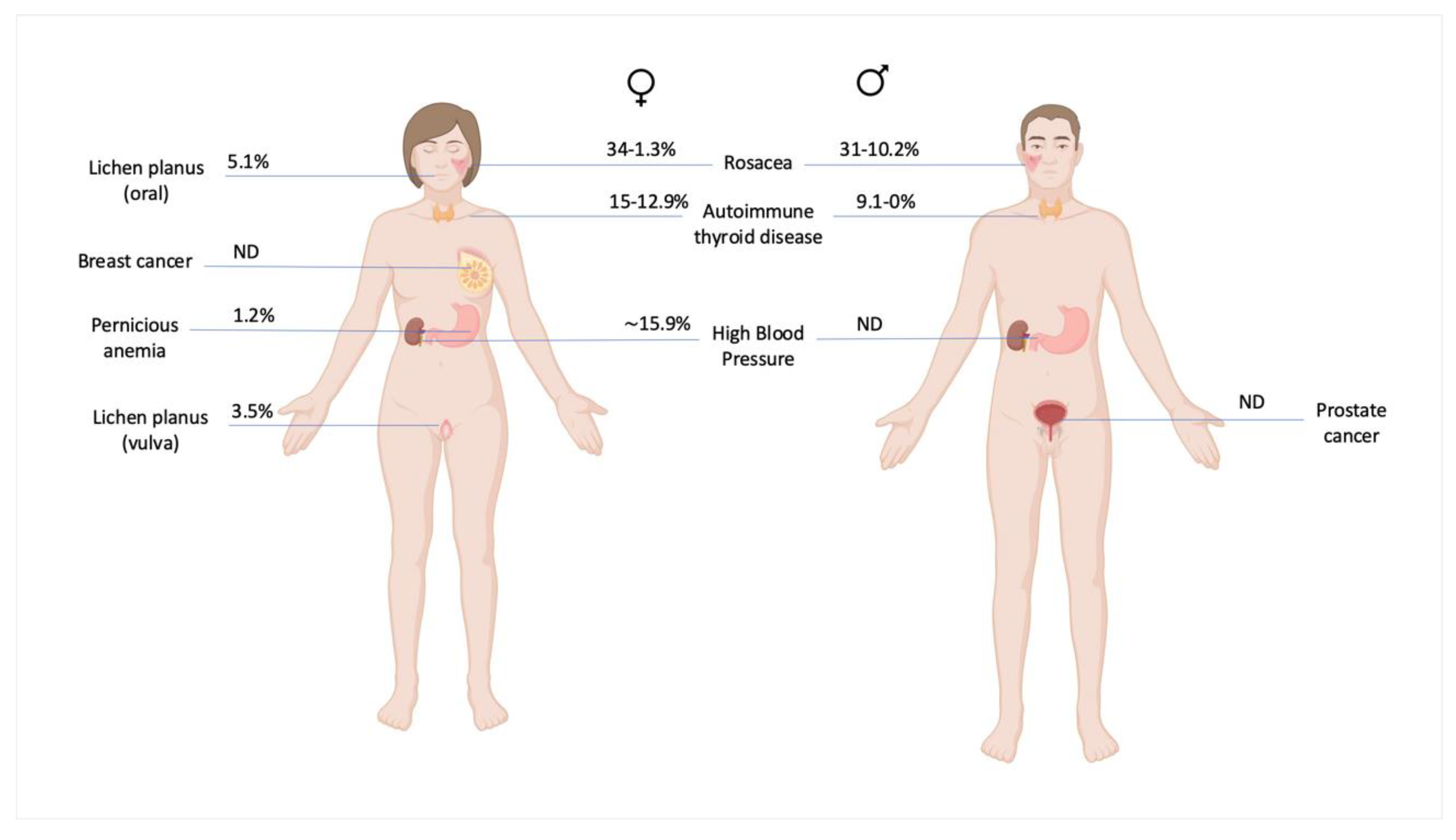

Epidemiology

Etiopathogenesis

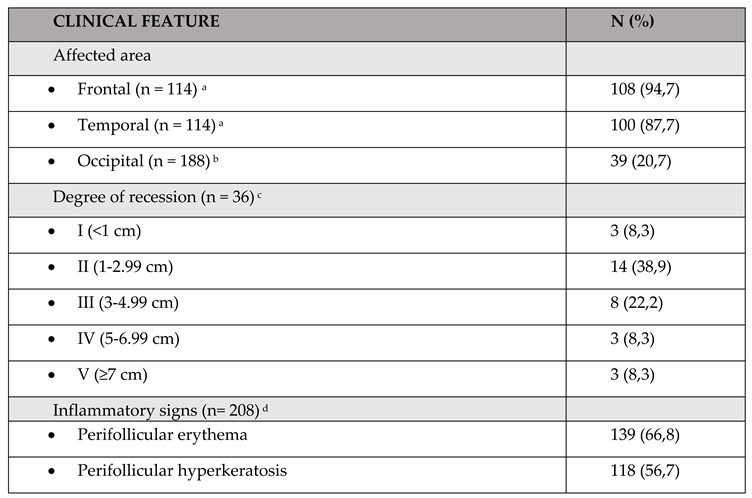

Clinical

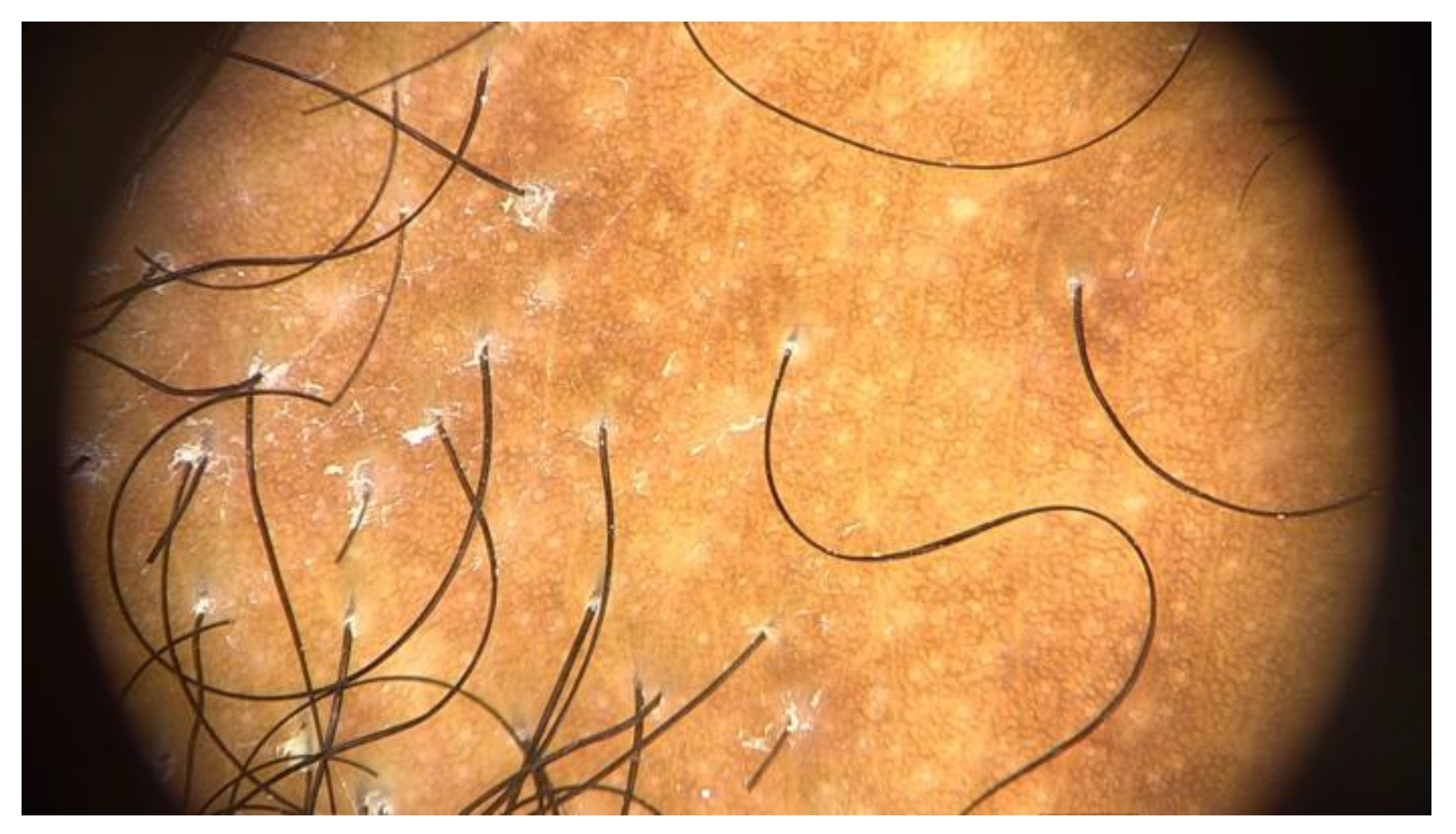

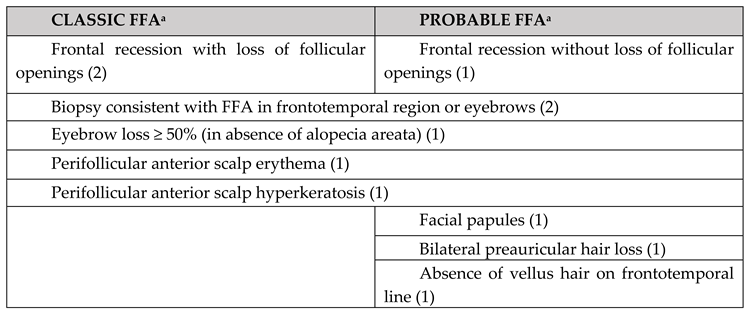

Diagnosis

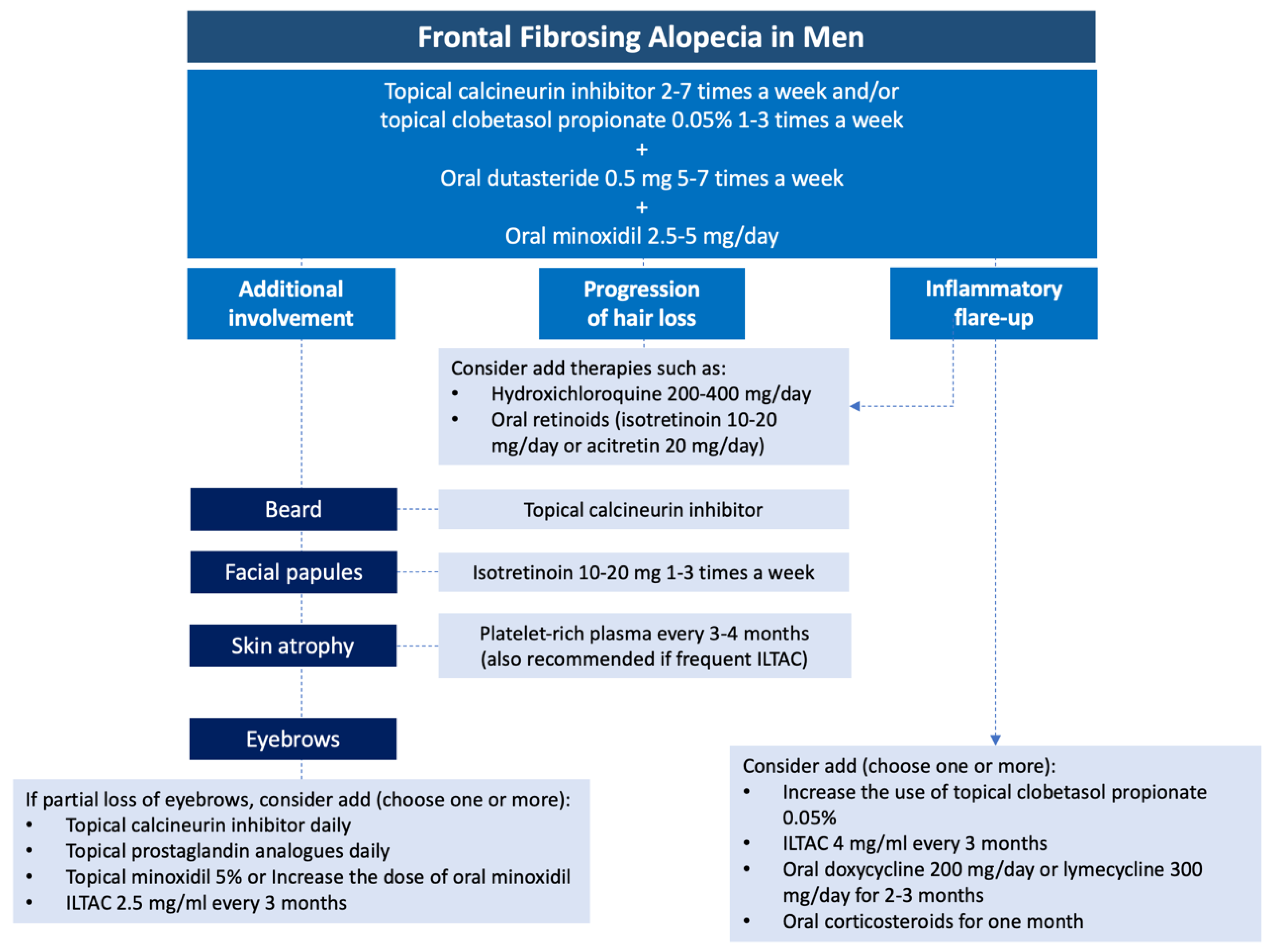

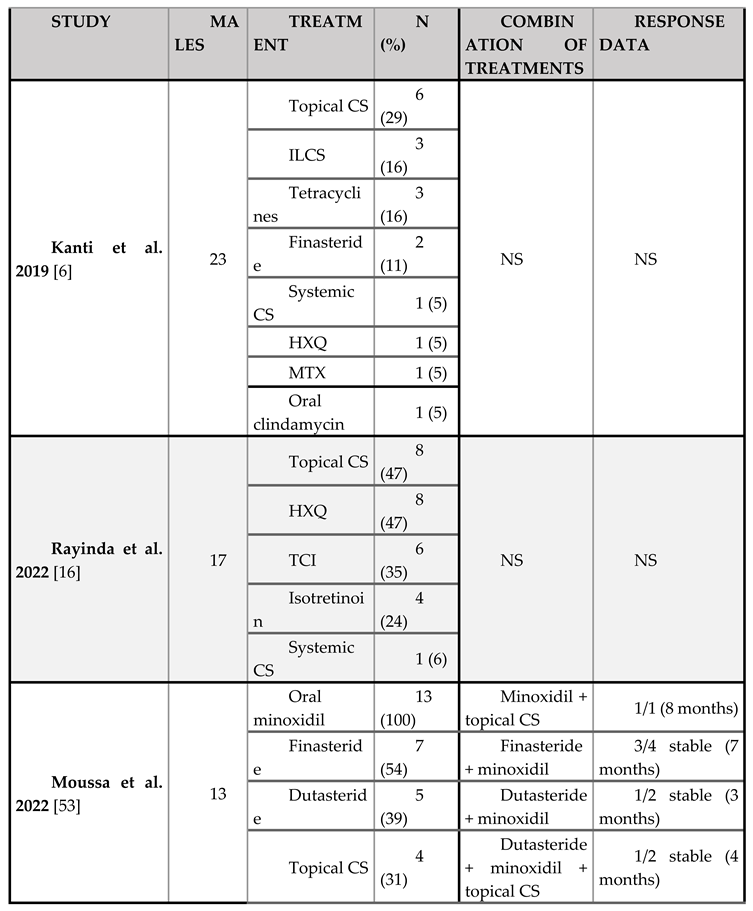

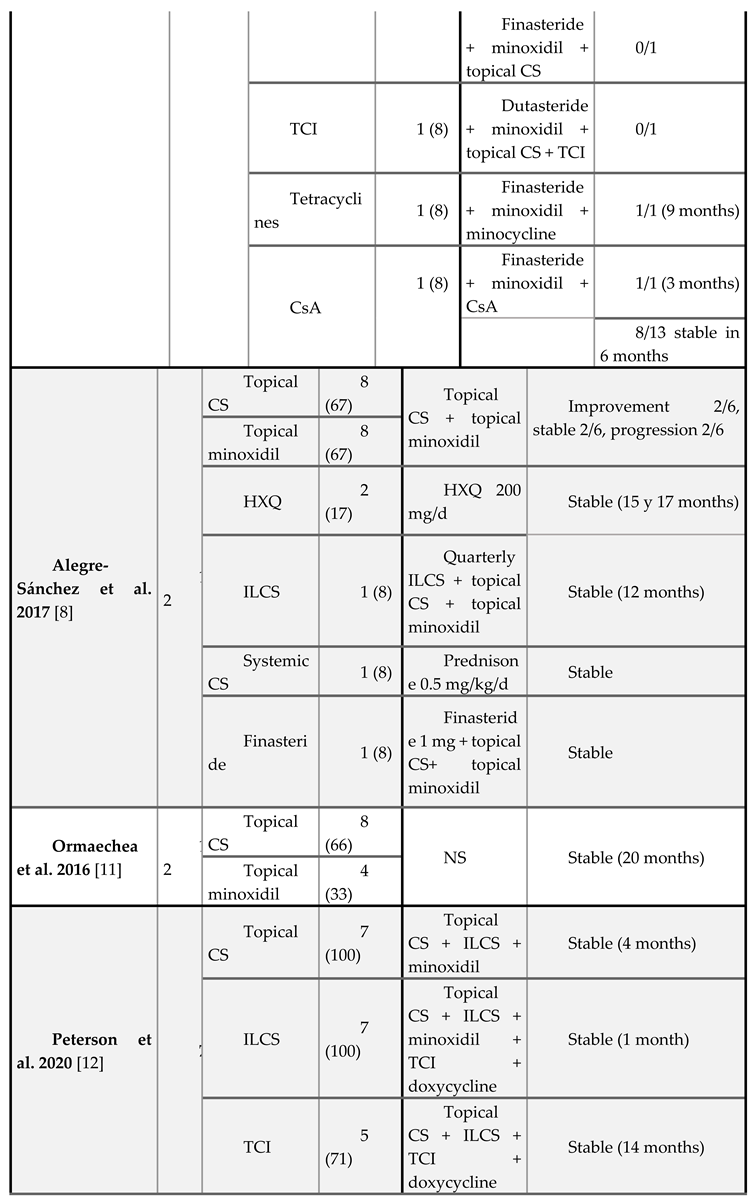

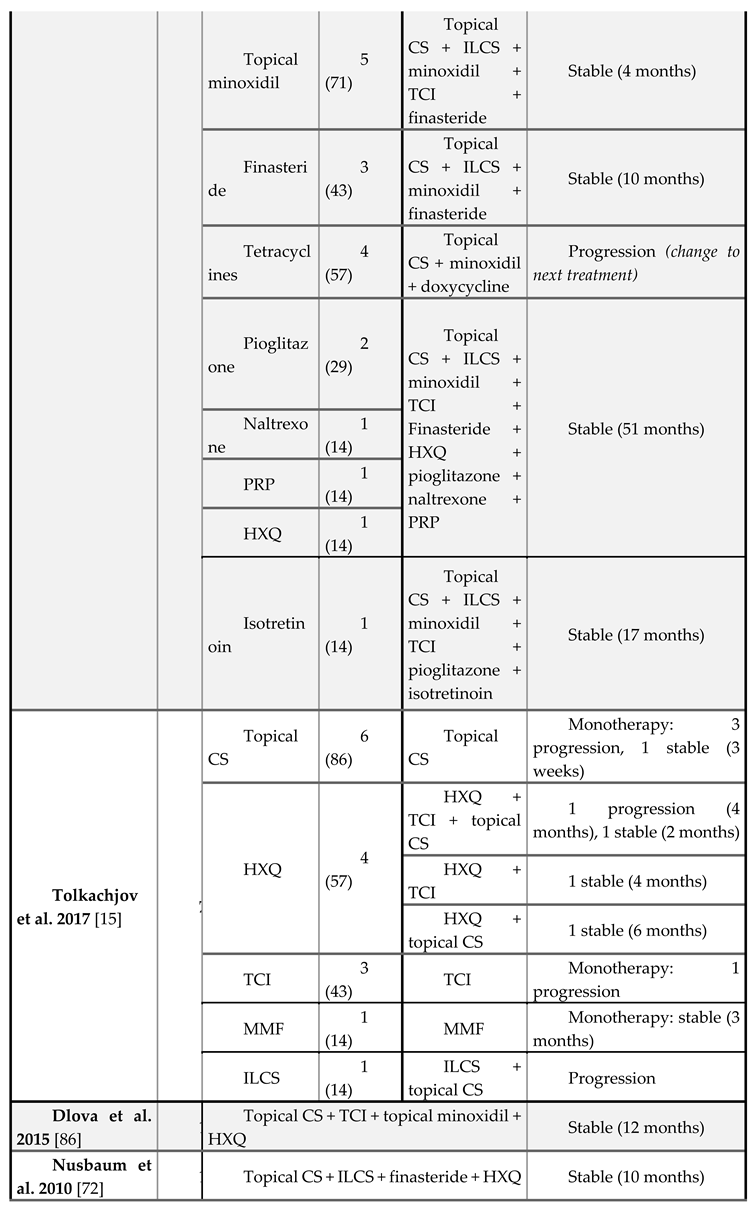

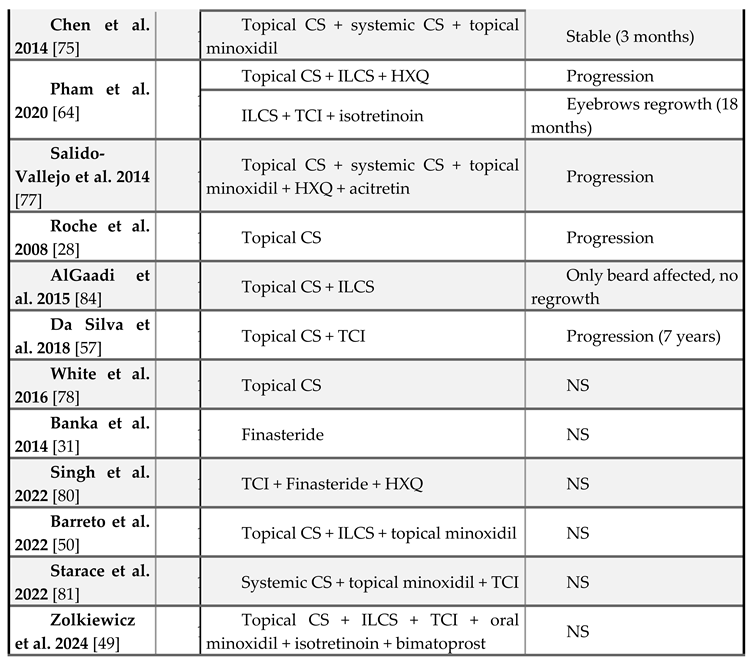

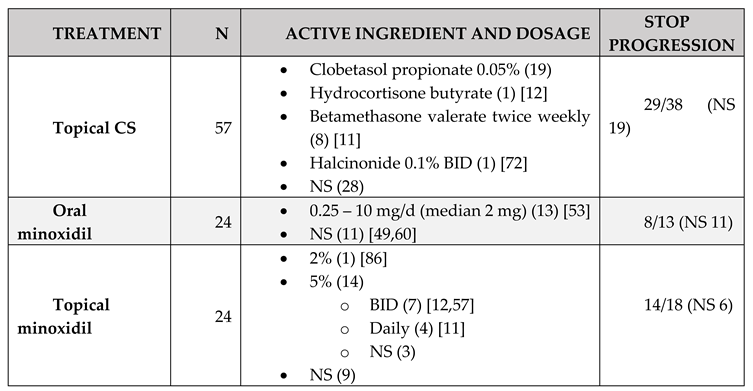

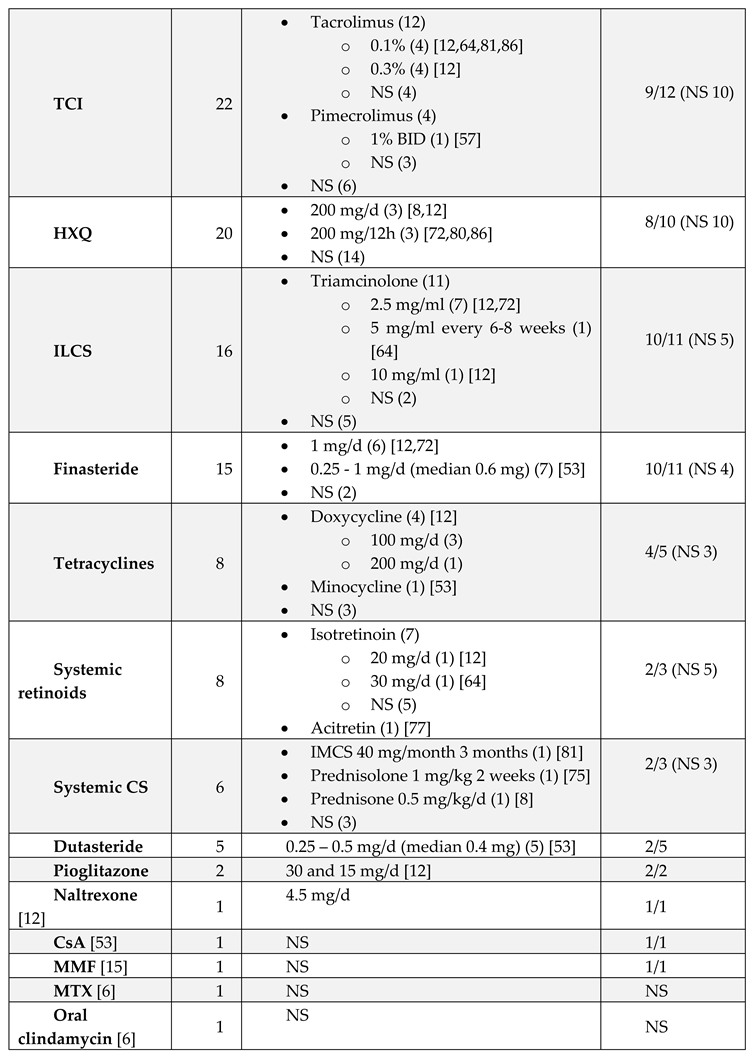

Treatment

References

- Kossard, S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. Scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994, 130, 770–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockmeier, M.; Kunte, C.; Sander, C.A.; Wolff, H. Frontale fibrosierende Alopezie Kossard bei einem Mann. Hautarzt. 2002, 53, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathoulas, J.T.; Flanagan, K.E.; Walker, C.J. , et al. A multicenter descriptive analysis of 270 men with frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planopilaris in the United States. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2023, 88, 937–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vañó-Galván, S.; Molina-Ruiz, A.M.; Serrano-Falcón, C. , et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A multicenter review of 355 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014, 70, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trager, M.H.; Lavian, J.; Lee, E.Y. , et al. Medical comorbidities and sex distribution among patients with lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021, 84, 1686–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanti, V.; Constantinou, A.; Reygagne, P.; Vogt, A.; Kottner, J.; Blume-Peytavi, U. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: demographic and clinical characteristics of 490 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019, 33, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphal, D.C.; Caballero-Uribe, N.; Regnier, A.; Taguti, P.; Dutra Rezende, H.; Trüeb, R.M. Male frontal fibrosing alopecia: study of 35 cases and association with sunscreens, facial skin and hair care products. Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegre-Sánchez, A.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Bernárdez, C.; Molina-Ruiz, A.M.; Arias-Santiago, S.; Vañó-Galván, S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in male patients: a report of 12 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017, 31, e112–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Arrones, O.M.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Rodrigues-Barata, A.R. , et al. Risk factors associated with frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicentre case-control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019, 44, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSweeney, S.M.; Christou, E.A.A.; Dand, N. , et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a descriptive cross-sectional study of 711 cases in female patients from the UK. Br J Dermatol. 2020, 183, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormaechea-Pérez, N.; López-Pestaña, A.; Zubizarreta-Salvador, J.; Jaka-Moreno, A.; Panés-Rodríguez, A.; Tuneu-Valls, A. Alopecia frontal fibrosante en el varón: presentación de 12 casos y revisión de la literatura. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2016, 107, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.; Gutierrez, D.; Brinster, N.K.; Lo Sicco, K.I.; Shapiro, J. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in males: demographics, clinical profile and treatment experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato-Berezo, A.; Iglesias-Sancho, M.; Rodríguez-Lomba, E. , et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in men: A multicenter study of 39 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2022, 86, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pindado-Ortega, C.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Buendía-Castaño, D. , et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and cutaneous comorbidities: A potential relationship with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018, 78, 596–597.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolkachjov, S.N.; Chaudhry, H.M.; Camilleri, M.J.; Torgerson, R.R. Frontal fibrosing alopecia among men: A clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017, 77, 683–690.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayinda, T.; McSweeney, S.M.; Dand, N.; Fenton, D.A.; McGrath, J.A.; Tziotzios, C. Clinical characteristics of male frontal fibrosing alopecia: a single-centre case series from London, UK. British Journal of Dermatology. 2022, 186, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, A.; Tadiotto Cicogna, G.; Caro, G.; Fortuna, M.C.; Magri, F.; Grassi, S. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: A New Association with Lichen Sclerosus in Men. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021, 14, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Doche, I.; Nico, M.M.S.; Gerlero, P. , et al. Clinical features and sex hormone profile in male patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia: A multicenter retrospective study with 33 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2022, 86, 1176–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranum, A.; Freese, R.; Ramesh, V.; Pearson, D.R. Lichen planopilaris is associated with cardiovascular risk reduction: a retrospective cohort review. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. 2024, 10, e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziotzios, C.; Petridis, C.; Dand, N. , et al. Genome-wide association study in frontal fibrosing alopecia identifies four susceptibility loci including HLA-B*07:02. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayinda, T.; McSweeney, S.M.; Fenton, D. , et al. Shared Genetic Risk Variants in Both Male and Female Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2023, 143, 2311–2314.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porriño-Bustamante, M.L.; López-Nevot, M.Á.; Aneiros-Fernández, J.; García-Lora, E.; Fernández-Pugnaire, M.A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Familial frontal fibrosing alopecia: A cross-sectional study of 20 cases from nine families. Aust J Dermatology. 2019, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porriño-Bustamante, M.L.; López-Nevot, M.Á.; Aneiros-Fernández, J. , et al. Study of Human Leukocyte Antigen ( HLA ) in 13 cases of familial frontal fibrosing alopecia: CYP 21A2 gene p.V281L mutation from congenital adrenal hyperplasia linked to HLA class I haplotype HLA - A*33:01 ; B*14:02; C*08:02 as a genetic marker. Aust J Dermatology. 2019, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, P.M.; Garbers, L.E.F.M.; Silva, N.S.B. , et al. A large familial cluster and sporadic cases of frontal fibrosing alopecia in Brazil reinforce known human leucocyte antigen (HLA) associations and indicate new HLA susceptibility haplotypes. Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020, 34, 2409–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Belmonte, M.R.; Navarro-López, V.; Ramírez-Boscà, A. , et al. Case series of familial frontal fibrosing alopecia and a review of the literature. J of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2015, 14, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlova, N.; Goh, C.L.; Tosti, A. Familial frontal fibrosing alopecia: Correspondence. British Journal of Dermatology. 2013, 168, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porriño-Bustamante, M.L.; García-Lora, E.; Buendía-Eisman, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Familial frontal fibrosing alopecia in two male families. Int J Dermatol. 2019, 58, e178–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, M.; Walsh, M.; Armstrong, D. Frontal fibrosing alopecia—Occurrence in male and female siblings. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008, 58, AB81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindado-Ortega, C.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Moreno-Arrones, Ó.M. , et al. Effectiveness of dutasteride in a large series of patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia in real clinical practice. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021, 84, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossard, S.; Shiell, R.C. Frontal fibrosing alopecia developing after hair transplantation for androgenetic alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2005, 44, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banka, N.; Mubki, T.; Bunagan, M.J.K.; McElwee, K.; Shapiro, J. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a retrospective clinical review of 62 patients with treatment outcome and long-term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 2014, 53, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobato-Berezo, A.; March-Rodríguez, A.; Deza, G.; Bertolín-Colilla, M.; Pujol, R.M. Frontal fibrosing alopecia after antiandrogen hormonal therapy in a male patient. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018, 32, e291–e292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debroy Kidambi, A.; Dobson, K.; Holmes, S. , et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in men: an association with facial moisturizers and sunscreens. Br J Dermatol. 2017, 177, 260–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, P.M.; Anzai, A.; Duque-Estrada, B. , et al. Risk factors for frontal fibrosing alopecia: A case-control study in a multiracial population. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021, 84, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kam, O.; Na, S.; Guo, W.; Tejeda, C.I.; Kaufmann, T. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and personal care product use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023, 315, 2313–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor-Nieto, M.A.; Gatica-Ortega, M.E.; Sánchez-Herreros, C.; Vergara-Sánchez, A.; Martínez-Mariscal, J.; De Eusebio-Murillo, E. Sensitization to benzyl salicylate and other allergens in patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Contact Dermatitis. 2021, 84, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestre, J.F.; Mercader, P.; González-Pérez, R. , et al. Sensitization to fragrances in Spain: A 5-year multicentre study (2011-2015). Contact Dermatitis. 2019, 80, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, V.B.; Donati, A.; Contin, L.A.; et al. Photopatch and patch testing in 63 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case series. Br J Dermatol. 2018, 179, 1402–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, L.; Rokni, G.R.; Lotti, T.; et al. Allergic contact dermatitis in patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia: An international multi-center study. Dermatologic Therapy 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Rodríguez, M.; Moro-Bolado, F.; Romero-Aguilera, G.; Ruiz-Villaverde, R.; Carriel, V. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: An Observational Single-Center Study of 306 Cases. Life. 2023, 13, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladizinski, B.; Bazakas, A.; Selim, M.A.; Olsen, E.A. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A retrospective review of 19 patients seen at Duke University. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013, 68, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samrao, A.; Chew, A.L.; Price, V. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinical review of 36 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2010, 163, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernárdez, C.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Gil-Redondo, R. , et al. Beard loss in men with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2022, 86, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.; Miteva, M. Distinct Trichoscopic Features of the Sideburns in Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Compared to the Frontotemporal Scalp. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018, 4, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, E.A.; Harries, M.; Tosti, A. , et al. Guidelines for clinical trials of frontal fibrosing alopecia: consensus recommendations from the International FFA Cooperative Group (IFFACG)*. Br J Dermatol. 2021, 185, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, G.C.A.E.; Cortez De Almeida, R.F.; Melo, D.F. Trichoscopy of Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Affecting Black Scalp: A Literature Review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2024, 10, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porriño-Bustamante, M.L.; Fernández-Pugnaire, M.A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: A Review. JCM. 2021, 10, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, T.D.M.; Cortez De Almeida, R.F.; Müller Ramos, P.; Jeunon, T.; Melo, D.F. The watch sign: an atypical clinical finding of frontal fibrosing alopecia in two male patients. Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żółkiewicz, J.; Maińska, U.; Nowicki, R.J.; Sobjanek, M.; Sławińska, M. The ‘Watch Sign’ – Another Observation in the Course of Male Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia. Dermatology Practical & Conceptual. 2024, 14, e2024132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, T.M.; Oliveira Xavier De Brito, E.; Medina Vilela, G.; Melo, D.F. Atypical frontal fibrosing alopecia presentation in a male patient associated with spontaneous reversal of canities. Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Nieto, M.A.; Vaño-Galvan, S.; Gómez-Zubiaur, A.; Jiménez-Blázquez, E.; Moreno-Arrones, O.M.; Melgar-Molero, V. Localized grey hair repigmentation (canities reversal) in patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vano-Galvan, S.; Saceda-Corralo, D. Oral dutasteride is a first-line treatment for frontal fibrosing alopecia. Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024, 38, 1455–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, A.; Bennett, M.; Bhoyrul, B.; Kazmi, A.; Asfour, L.; Sinclair, R.D. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of frontal fibrosing alopecia in men. Int J Dermatology 2022, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Oh, S.U.; Kim, S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.S. Dutasteride in the treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024, 38, 1514–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppt, M.V.; Letulé, V.; Laniauskaite, I. , et al. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: A Retrospective Analysis of 72 Patients from a German Academic Center. Facial Plast Surg. 2018, 34, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strazzulla, L.C.; Avila, L.; Li, X.; Lo Sicco, K.; Shapiro, J. Prognosis, treatment, and disease outcomes in frontal fibrosing alopecia: A retrospective review of 92 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018, 78, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Libório, R.; Trüeb, R.M. Case Report of Connubial Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2018, 10, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Ramírez, D.; Ferrándiz, L.; Camacho, F.M. [Diagnostic and therapeutic assessment of frontal fibrosing alopecia]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007, 98, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira Xavier De Brito, F.; Cortez De Almeida, R.F.; Frattini, S.; Baptista Barcaui, C.; Starace, M.; Fernandes Melo, D. Is there a rationale for the Use of Lymecycline for Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia? Dermatol Pract Concept. 2024, e2024018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pindado-Ortega, C.; Pirmez, R.; Melo, D.F.; et al. Low-dose oral minoxidil for frontal fibrosing alopecia: a 122-patient case series. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2024, S000173102400886X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrosa, A.F.; Duarte, A.F.; Haneke, E.; Correia, O. Yellow facial papules associated with frontal fibrosing alopecia: A distinct histologic pattern and response to isotretinoin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017, 77, 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, H.; Rostami, A.; Tavakolpour, S. , et al. Oral isotretinoin combined with topical clobetasol 0.05% and tacrolimus 0.1% for the treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 2022, 33, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahpar, A.; Nezhad, N.Z.; Sahaf, A.; Ahramiyanpour, N. A review of isotretinoin in the treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia. J of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2024, 23, 1956–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.T.; Hosking, A.M.; Cox, S.; Mesinkovska, N.A. Therapeutic response of facial papules and inflammation in frontal fibrosing alopecia to low-dose oral isotretinoin. JAAD Case Reports. 2020, 6, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirmez, R.; Spagnol Abraham, L. Eyebrow Regrowth in Patients with Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Treated with Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021, 7, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.C.; Samrao, A.; Ruben, B.S.; Price, V.H. Eyebrow regrowth in patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia treated with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide: Correspondence. British Journal of Dermatology. 2010, 163, 1142–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, A.; Bergfeld, W. Prostaglandin analogue for treatment of eyebrow loss in frontal fibrosing alopecia: three cases with different outcomes. Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svigos, K.; Yin, L.; Shaw, K. , et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma in lichen planopilaris and its variants: A retrospective case series demonstrating treatment tolerability without koebnerization. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2020, 83, 1506–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.; Park, M.; Babadjouni, A.; Atanaskova Mesinkovska, N. Evaluating Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Scarring Alopecia: A Systematic Review. JDD. 2024, 23, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, A.; Navarro, M.R.; Ramirez, A. , et al. Plasma Rich in Growth Factors as an Adjuvant Treatment for the Management of Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: A Retrospective Observational Clinical Study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023, 27, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vañó-Galván, S.; Villodres, E.; Pigem, R. , et al. Hair transplant in frontal fibrosing alopecia: A multicenter review of 51 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019, 81, 865–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusbaum, B.P.; Nusbaum, A.G. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia in a Man: Results of Follicular Unit Test Grafting. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010, 36, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saceda-Corralo, D.; Pindado-Ortega, C.; Moreno-Arrones, Ó.M. , et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Santiago, S.; O’Valle, F.; Husein ElAhmed, H. A man with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011, 64, AB91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Kigitsidou, E.; Prucha, H.; Ring, J.; Andres, C. Male frontal fibrosing alopecia with generalised hair loss: Male frontal fibrosing alopecia. Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 2014, 55, e37–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Fenton, D.A.; Stefanato, C.M. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lupus overlap in a man: guilt by association? Int J Trichology. 2013, 5, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salido-Vallejo, R.; Garnacho-Saucedo, G.; Moreno-Gimenez, J.C.; Camacho-Martinez, F.M. Beard involvement in a man with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014, 80, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, F.; Callahan, S.; Kim, R.H.; Meehan, S.A.; Stein, J. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in a 46-year-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2016, 22, 13030–qt82h822bg. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Garza, S.S.; Vastarella, M.; Ocampo-Candiani, J.; et al. Trichoscopy of the beard: Aid tool for diagnosis of frontal fibrosing alopecia in men. JAAD Case Reports 2021, 15, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Arshdeep Batrani, M.; Kubba, A. Male frontal fibrosing alopecia with generalized body hair loss. Int J Trichol. 2022, 14, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starace, M.; Alessandrini, A.; Brandi, N.; Misciali, C.; Piraccini, B.M. First Italian case of frontal fibrosing alopecia in a male. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2022, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Marak, A.; Paul, D.; Dey, B. A Retrospective Study of Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia from North-East India. Indian Journal of Dermatology. 2023, 68, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altemir, A.; Lobato-Berezo, A.; Pujol, R.M. Scalp demodicosis developing in a patient with frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinical and trichoscopic mimicker of active disease. Int J Dermatology 2022, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlGaadi, S.; Miteva, M.; Tosti, A. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in a male presenting with sideburn loss. Int J Trichol. 2015, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswamy, P.; Mendese, G.; Goldberg, L.J. Scarring Alopecia of the Sideburns: A Unique Presentation of Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia in Men. Arch Dermatol. 2012, 148, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dlova, N.C.; Goh, C.L. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in an African man. Int J Dermatol. 2015, 54, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).