Rethinking Protein Structure: Challenges in Understanding Protein Order and Disorder

The thermodynamic hypothesis, proposed by the Nobel Laureate in Chemistry 1972, Dr. Christian B. Anfinsen, asserts that a native protein’s three-dimensional structure in its normal physiological environment corresponds to the state where the Gibbs free energy of the entire system is minimized. This implies that the complete array of interatomic interactions governs the native conformation, which is dictated by the amino acid sequence in a specific environment. The Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences granted the Prize for his ground-breaking ‘studies on ribonuclease, in particular, the relationship between the amino acid sequence and the biologically active conformation’ [

1]. Yet, the intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) refute this theory.

IDPs are abundant in the human proteome and are characterized in unfolded regions that lack stable 3D structures. They adopt several conformations, usually in the proximity of the binding protein partner, and therefore constitute key regulatory elements in complex cellular processes such as signal transduction, cell cycle modulation, chromatin remodelling or gene transcription [

2].

Anfinsen’s principle underpins much of our understanding of protein folding but needed to be reconsidered in light of the structural versatility and the key role of IDPs in the cellular processes.

Thus, the efforts to predict protein structures have recently culminated in

in silico protein design and transformative AI-based tools like AlphaFold (AF) (

Box 1).

Box 1. Publicly available depositories and databases supporting structural analysis of biomolecules.

To unlock the structure of IDPs, combining the publically available data from DisProt, Alphafold and SASBDB databases provides a comprehensive approach. DisProt provides a curated repository for IDPs, focusing on their structural and functional aspects (https://disprot.org). Alphafold generates highly accurate protein 3D structures’ predictions from amino acid sequences (

https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk). The dataset of solved protein structures can be extracted from the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (

https://www.wwpdb.org ) and supports molecular replacement analysis. SASBDB (

https://www.sasbdb.org) reveals protein dynamics in solution, closely representing its native state in the cell. Together, these resources provide valuable insights into IDP behaviour, helping refine structural predictions and improve our understanding of protein folding in biologically relevant environments.

In 2024, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognised this progress, awarding David Baker for computational protein design and jointly Demis Hassabis and John M. Jumper for advancements in protein structure prediction.

The technologies have already played a significant role in drug discovery by enabling target protein modelling, de novo pharmaceutical peptide design and in silico screen of large compound libraries.

However, the main challenge of the AF algorithm arises from its reliance on deep learning, which is limited by the available dataset of solved protein structures in the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (

Box 1).

As such, the flexibility and dynamic behaviour of unfolded or partially disordered proteins remain beyond the predictive capabilities of current AI models.

Flexibility, however, is often a necessary aspect of protein function, and the protein universe is replete with multi-domain proteins composed of structured units with flexible linkers of variable length that limit both crystallographic and cryoEM studies.

Thus, we see that there is an urgent need to test and complement the AF predictions with experimental techniques, notably those that are readily available in core facilities or accessible on dedicated large infrastructures.

Addressing the knowledge gaps in characterising the conformational ensembles of IDPs is crucial for advancing our understanding of protein folding and function to develop new therapeutic strategies for precision medicine.

Intrinsically Disordered p53 and Allosteric Modulation Phenomenon

In IDPs, conformational transitions to folded states occur either through posttranslational modifications or in the proximity of the target ligand or the binding protein partner, thus improving the target specificity [

3].

The most studied IDP in human proteome is the p53 tumor suppressor, which contains approximately 40% of disordered regions (

Box 1).

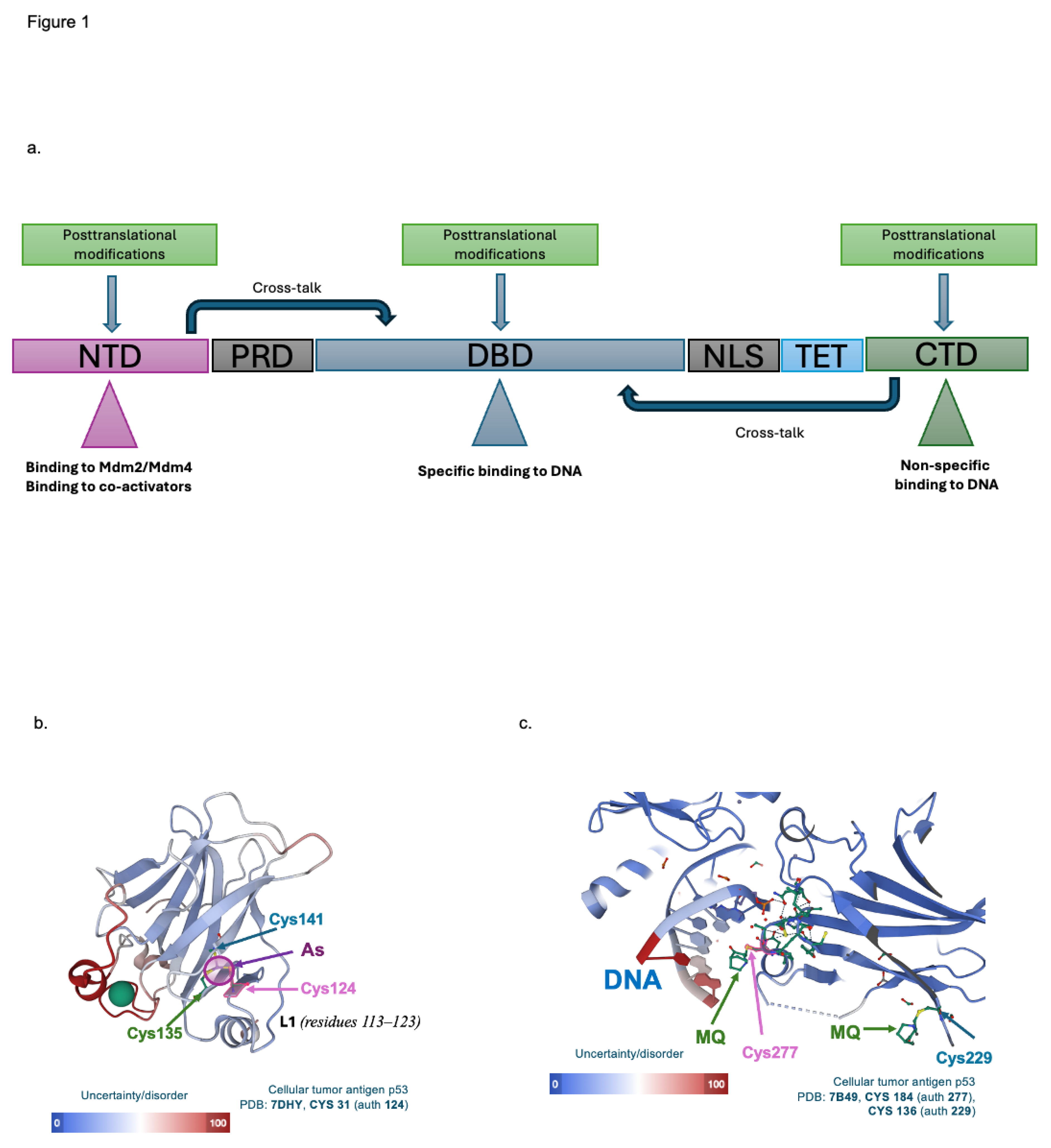

p53 is a vital tumor suppressor inactivated in all human cancers. It plays a key role in controlling cell fate under cellular stress like DNA damage, hypoxia or oncogene activation. As a pleiotropic transcription factor, p53 regulates the expression of over 100 target genes. It functions as a homotetramer featuring essential domains: an intrinsically disordered N-terminal transactivation domain (NTD), a proline-rich domain (PRD), a folded DNA-binding domain (DBD), a nuclear localisation signal (NLS), a tetramerisation domain (TET), and unfolded C-terminal domain (CTD). Each domain is integral to the protein’s functionality (

Figure 1a) [

4].

Depending on the type and severity of the stress, p53 undergoes multiple posttranslational modifications. These modifications, through allosteric modulation, shift the structure of p53 functional domains. For example, the phosphorylation at Thr

18 or Ser

15 affects the structure of the Mdm2 binding site in p53 (Phe

19, Trp

23, and Leu

26) and inhibits p53/Mdm2 interactions. This prevents p53 ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation. Posttranslational modifications also enable interactions with transcription co-factors or co-activators (

Figure 1a). Additionally, long-chain and/or direct interactions between NTD and CTD of p53 and the DBD induced by posttranslational modifications were reported. These allosteric modulations enhance p53 stability, promote binding to the canonical DNA sequence and drive gene expression induction.

Since its discovery in 1979, the structure of p53 has been intensively studied. However, the NTD and CTD are intrinsically disordered, and the full-length p53 exists in multiple conformations, making it impossible to crystallize the entire protein. For instance, NTD adopts a helical structure when in proximity to the Mdm2 binding pocket [

5,

6]. Likewise, the CTD transitions to the helical structure when subjected to posttranslational modifications like acetylation or when interacting with the partner proteins. Such structural adaptation allows p53 to bind non-specifically to DNA and slide along it in search of target genes [

4].

The structural flexibility of the DNA binding domain and its crosstalk with the CTD was supported in the studies investigating the intrinsic regulatory mechanism in the mutant p53 DBD. Mutant p53 can be reactivated by C-terminus-derived peptides or antibodies. The binding of these molecules triggers long-chain fluctuations, refolding DBD to a wild-type-like conformation. Thus, DBD and C-terminus interact to regulate DNA binding and p53 latency [

7,

8].

The flexibility of the p53 functional domains provides opportunities for the development of new therapeutic approaches that reactivate p53 in cancers either by; (1) preventing its interactions with negative regulators to stabilise wild-type protein; or (2) correcting the folding of mutant DBD and increasing specific DNA binding. These aspects are described in more detail below.

Beyond X-Ray Crystallography: Unrevealing Hidden p53’s Structural Elements Which Can Be Exploited for Precision Oncology

Despite the progress in AI innovations, resolving the structures of IDPs remains a critical challenge and hampers connecting structure to biological function. Traditional X-ray crystallography is inadequate, as these proteins rarely crystallize, and their inherent flexibility demands robust methods that examine the structure in solutions.

In p53, NTD plays a critical function in protein stability and activation of transcription activity. It is unstructured in solution and forms a partial helix when in the proximity of the interacting molecules.

Recently, Monte Carlo simulations of the cryogenic electron microscopy model of full-length p53 tetramer revealed that targeting the region in NTD spanning residues 33-37 with small molecules or repurposed drugs induces allosteric shift and prevents p53/Mdm2/Mdm4 interactions. Ion-mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS), which allows for studying native protein conformations, and circular dichroism demonstrated that drug binding leads to structural compaction, inhibiting these interactions [

9].

Interestingly, fusing the NTD p53 with the N-terminus of the spider silk protein, spidroin, improves p53 translation, stabilizes p53 in cells, and makes the NTD domain more compact. Molecular dynamics, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and IM-MS analyses indicated that the fused NTD maintains a folded conformation. This structural stability leads to a compact arrangement of the chimeric construct and supports the feasibility of the NTD structure compaction to prevent p53/Mdm2 interactions in cancer cells [

10].

Thus, methods that allow for the analysis of intact protein structures in solution complemented by in silico analysis such as molecular dynamic simulation, might deepen our knowledge of structural conformers in p53 to design a novel approach to inhibit p53/Mdm2 interactions.

In cancers, p53 is also inactivated by TP53 gene mutations in most of the missense type. These mutations induce significant variability in their functional effects on DBD, impairing p53’s ability to bind its target promoters.

While targeting structural p53 mutations is a daunting task due to their tendency to unfold, a new frontier for therapeutic intervention lies in exploiting allosteric modulation within the p53 DBD.

For example, X-ray crystallography of G245S mutant p53 DBD identified a novel allosteric site, called an As-binding pocket, where the arsenic ion interacts with a cysteine triad (Cys

124, Cys

135 and Cys

141) and Met

133, stabilizing the critical DNA-binding loop-sheet-helix motif (

Figure 1b) [

11]. The stabilization restores the transcriptional activity of a broad spectrum of p53 mutants and prevents protein-DNA aggregation associated with certain mutations, such as Y220C. Targeting the novel allosteric site thus offers a comprehensive strategy for restoring p53 activity in cancer by enhancing protein stability and DNA binding.

Another approach to reactivate mutant p53, which has not been fully explored yet, is mediated by APR-246/eprenetapopt. The active form of the drug, methylene quinuclidinone (MQ), specifically binds to cysteine residues in the p53 core domain [

12]. This interaction stabilizes the structure of the mutant protein, likely through an allosteric shift, and enhances its binding to DNA (

Figure 1c). Further studies are needed to explore the allosteric regulation in p53 DBD through targeting cysteine residues.

p53 functions as a tetramer, but its disorder complicates structural analysis by X-ray crystallography. The quaternary structure of human p53 was successfully studied in solution using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and NMR.

The p53 fragments or full-length p53 protein which harbour p53 stabilizing mutations (M133L/V203/N239Y/N268D) in the p53 core domain, with or without DNA, were modelled using SAXS, supplemented with the information from nuclear magnetic resonance showing transient interactions between core domains. The analysis reveals that p53 is an open tetramer in a solution that transitions into a fully folded structure upon binding to DNA.

Yet, electron microscopy of the immobilised superstable pseudo-wild-type mutant p53 alone, predominantly showed a closed conformation, which must open for DNA to bind. Thus, structural insights from SAXS and NMR take precedence over those from electron microscopy and might provide critical information mechanistic insights on the reconstitution of transcriptional activity of p53 [

13].

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the National Science Center, Poland (2020/39/B/NZ7/00757) and by Stiftelsen Cancercentrum Karolinska to J.E.Z.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Anfinsen, C.B. Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science 1973, 181, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holehouse, A.S. and Kragelund, B. B. The molecular basis for cellular function of intrinsically disordered protein regions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 187–211. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.E. and Dyson, H. J. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 293, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.; et al. p53 contains large unstructured regions in its native state. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 322, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kussie, P.H.; et al. Structure of the MDM2 oncoprotein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Science 1996, 274, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawacka-Pankau, J.E. The role of p53 family in cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, D.P.; Hupp, T.R. Drug discovery and p53. Drug Discov. Today 2003, 8, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selivanova, G.; et al. Reactivation of mutant p53: a new strategy for cancer therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1998, 8, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinkevich, V.V.; et al. Novel Allosteric Mechanism of Dual p53/MDM2 and p53/MDM4 Inhibition by a Small Molecule. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 823195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaldmäe, M.; et al. A “spindle and thread” mechanism unblocks p53 translation by modulating N-terminal disorder. Structure 2022, 30, 733–742.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; et al. Arsenic Trioxide Rescues Structural p53 Mutations through a Cryptic Allosteric Site. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 225–239.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; et al. APR-246 reactivates mutant p53 by targeting cysteines 124 and 277. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidow, H.; et al. Quaternary structures of tumor suppressor p53 and a specific p53 DNA complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007, 104, 12324–12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookes, E.; et al. AlphaFold-predicted protein structures and small-angle X-ray scattering: insights from an extended examination of selected data in the Small-Angle Scattering Biological Data Bank. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2023, 56, 910–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; et al. AlphaFold-guided molecular replacement for solving challenging crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2025, 81, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).