Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

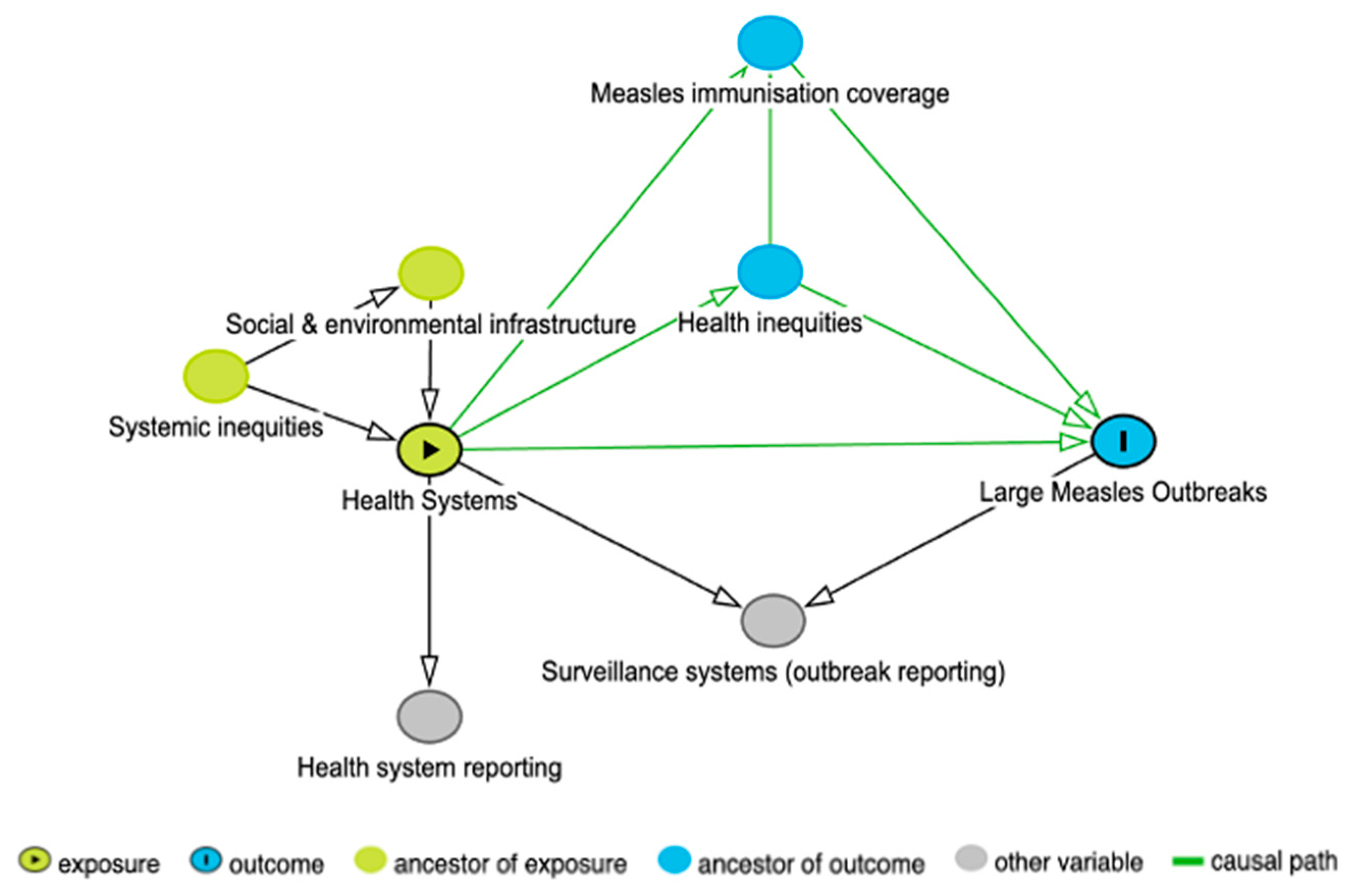

2.1. Directed Acyclic Graph

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Measles Outbreaks

2.2.2. Health Systems

2.2.3. Gini Coefficient

2.3. Data Processing

2.4. Analysis Methods

2.4.1. Regression Model Fitting

2.4.2. Regression Model Testing

2.4.3. Effect Modification and Missing Data

3. Results

3.1. DAG

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

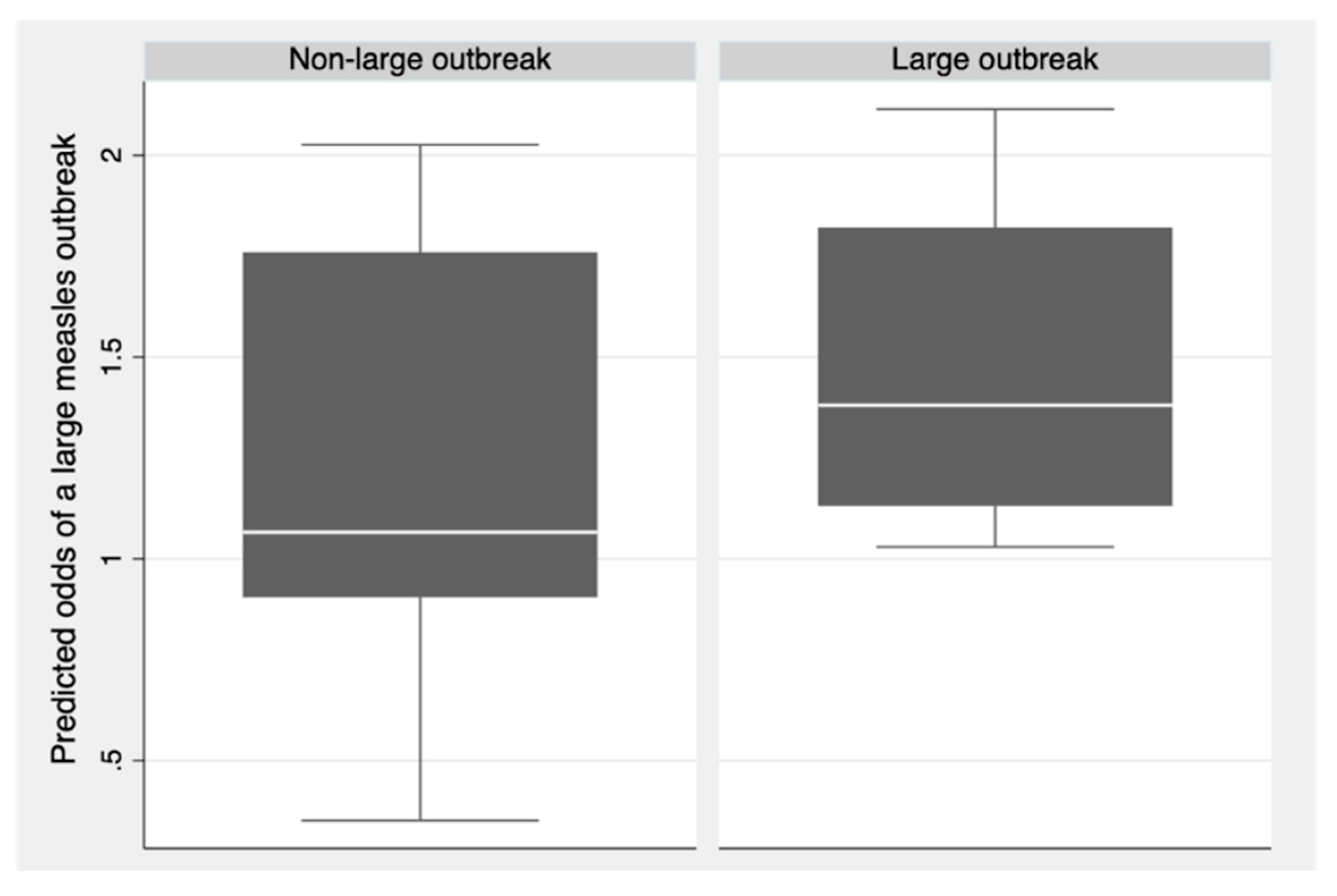

3.3. Regression Analysis

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

3.5. Missing Data

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LMIC | Low-and-middle-income country |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Large outbreak definition | Input variable | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence intervals | p-value | Brier score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 cases | Proportion of births delivered in a health facility (%) | 0.99 | (0.95, 1.04) | 0.77 | 0.330 |

| Number of nurses and midwives (per 10,000 population) | 1.03 |

(0.98, 1.08) |

0.29 |

||

| Health expenditure (per capita in US$) | 0.99 | (0.98, 1.00) | 0.18 | ||

| 150 cases | Proportion of births delivered in a health facility (%) | 1.00 | (0.96, 1.03) | 0.86 | 0.217 |

| Number of nurses and midwives (per 10,000 population) | 1.02 | (0.98, 1.06) | 0.31 | ||

| Health expenditure (per capita in US$) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.00) | 0.26 | ||

| 200 cases | Proportion of births delivered in a health facility (%) | 1.00 | (0.97, 1.04) | 0.88 | 0.205 |

| Number of nurses and midwives (per 10,000 population) | 1.02 | (0.98, 1.06) | 0.26 | ||

| Health expenditure (per capita in US$) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.00) | 0.31 |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Complications of Measles. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/measles/symptoms/complications.html (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- World Health Organization. History of the Measles Vaccine. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/history-of-measles-vaccination (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- World Health Organization. Measles. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Iacobucci, G. Measles is now “an imminent threat” globally, WHO and CDC warn. BMJ 2022, 379, o2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immunization Agenda (IA2030) Scorecard. Reduce large or disruptive vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks. Available online: https://scorecard.immunizationagenda2030.org/ig1.3 (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- World Health Organization, UNICEF. Progress and challenges with Achieving Universal Immunization Coverage; 2023.

- Local Burden of Disease Vaccine Coverage Collaborators. Mapping routine measles vaccination in low- and middle-income countries. Nature 2021, 589, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Immunization data portal. Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/ (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Guerra, F.M.; Bolotin, S.; Lim, G.; Heffernan, J.; Deeks, S.L.; Li, Y.; Crowcroft, N. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17, e420–e428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Nearly 40 million children are dangerously susceptible to growing measles threat. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-11-2022-nearly-40-million-children-are-dangerously-susceptible-to-growing-measles-threat (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Pandey, A.; Galvani, A.P. Exacerbation of measles mortality by vaccine hesitancy worldwide. Lancet Glob Health 2023, 11, e478–e479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Immunization Agenda 2030: A Global Strategy To Leave No One Behind; World Health Organization: 2020.

- LaBeaud, D.A.; Malhotra, I.; King, M.J.; King, C.L.; King, C.H. Do Antenatal Parasite Infections Devalue Childhood Vaccination? PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2009, 3, e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciu, A.; Negussie, Y.; Geller, A.; Weinstein, J.N. The Root Causes of Health Inequity. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity 2017.

- Gavi the Vaccine Alliance. Gavi’s Strategy. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/strategy (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Gavi the Vaccine Alliance. Reaching Zero-dose Children. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/strategy/phase-5-2021-2025/equity-goal/zero-dose-children-missed-communities (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Dalton, M.; Sanderson, B.; Robinson, L.J.; Homer, C.S.E.; Pomat, W.; Danchin, M.; Vaccher, S. Impact of COVID-19 on routine childhood immunisations in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. PLOS Glob Public Health 2023, 3, e0002268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Broucker, G.; Ahmed, S.; Hasan, Z.; Mehdi, G.G.; Del Campo, J.M.; Ali, W.; Uddin, J.; Constenla, D.; Patenaude, B. The economic burden of measles in children under five in Bangladesh. BMC Health Serv Res 2020, 20, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Measles and rubella strategic framework 2021-2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- John, J. Measles: A Canary in the Coal Mines? Indian J Pediatr 2016, 83, 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.; Rahimi, N.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C. Factors limiting data quality in the expanded programme on immunization in low and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Vaccine 2020, 38, 4652–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cao, B.; Borghi, E.; Chatterji, S.; Garcia-Saiso, S.; Rashidian, A.; Doctor, H.; D’Agostino, M.; Karamagi, H.; Novillo-Ortiz, D.; et al. Data gaps towards health development goals, 47 low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ 2022, 100, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veillard, J.; Cowling, K.; Bitton, A.; Ratcliffe, H.; Kimball, M.; Barkley, S.; Mercereau, L.; Wong, E.; Taylor, C.; Hirschhorn, L.; et al. Better Measurement for Performance Improvement in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative (PHCPI) Experience of Conceptual Framework Development and Indicator Selection. Milbank Q 2017, 95, 836–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. UNICEF and WHO warn of perfect storm of conditions for measles outbreaks, affecting children. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2022-unicef-and-who-warn-of--perfect-storm--of-conditions-for-measles-outbreaks--affecting-children (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Gastañaduy, P.; Banerjee, E.; DeBolt, C.; Bravo-Alcántara, P.; Samad, S.; Pastor, D.; Rota, P.; Patel, M.; Crowcroft, N.; Durrheim, D. Public health responses during measles outbreaks in elimination settings: Strategies and challenges. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018, 14, 2222–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies.; 2010.

- Grimm, P.Y.; Oliver, S.; Merten, S.; Han, W.W.; Wyss, K. Enhancing the Understanding of Resilience in Health Systems of Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Int J Health Policy Manag 2022, 11, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, Z.; Ebrahimi, P.; Aryankhesal, A.; Maleki, M.; Yazdani, S. Toward a theory-led meta-framework for implementing health system resilience analysis studies: a systematic review and critical interpretive synthesis. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanefeld, J.; Mayhew, S.; Legido-Quigley, H.; Martineau, F.; Karanikolos, M.; Blanchet, K.; Liverani, M.; Yei Mokuwa, E.; McKay, G.; Balabanova, D. Towards an understanding of resilience: responding to health systems shocks. Health Policy Plan 2018, 33, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Primary health care measurement framework and indicators: monitoring health systems through a primary health care lens; World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): Geneva, 2022.

- World Health Organization. Health systems resilience toolkit: a WHO global public health good to support building and strengthening of sustainable health systems resilience in countries with various contexts; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health 2018, 6, E1196–E1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, J.; van der Zander, B.; Gilthorpe, M.; Liskiewicz, M.; Ellison, G. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ’dagitty’. Int J Epidemiol 2016, 45, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Measles Outbreak Toolkit. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/outbreak-toolkit/disease-outbreak-toolboxes/measles-outbreak-toolbox (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- ReliefWeb. All Disasters. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/disasters (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- World Health Organization. Disease Outbreak News (DONs). Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- World Health Organization. Global progress against measles threatened amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/10-11-2021-global-progress-against-measles-threatened-amidst-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Mavoungou, Y.; Niama, F.; Gangoué, L.; Koukouikila-Koussounda, F.; Bayonne, M.; Nkoua Badzi, C.; Gandza Gampouo, L.; Kiminou, P.; Biyama-Kimia, P.; Mahoukou, P.; et al. Measles Outbreaks in the Republic of Congo: Epidemiology of Laboratory-Confirmed Cases Between 2019 and 2022. Adv Virol 2024, 2024, 8501027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. 2. Regional Office for Africa. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/1637 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Americas. Measles/Rubella bi-Weekly Bulletin. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/measles-rubella-weekly-bulletin?topic=4914&d%5Bmin%5D=&d%5Bmax%5D= (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific Region. 7. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/137517 (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. 5. Regional Office for Europe. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/107131 (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. 6. Regional Office for South-East Asia. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/126384 (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Weekly Epidemiological Monitor. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/pandemic-epidemic-diseases/information-resources/weekly-epidemiological-monitor.html (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- World Health Organization. Indicators. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/indicator-explorer-new/mca/proportion-of-births-delivered-in-a-health-facility (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- World Health Organization. Domestic general government health expenditure (GGHE-D) per capita in US$. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/domestic-general-government-health-expenditure--(gghe-d)-per-capita-in-us (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- World Health Organization. Nursing and midwifery personnel (per 10 000 population). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/nursing-and-midwifery-personnel-(per-10-000-population) (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Hasell, J. Measuring inequality: What is the Gini coefficient? Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/what-is-the-gini-coefficient (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- The World Bank. Gini index. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?end=2022&start=2022&view=map&year=1997 (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- The World Bank. Population estimates and projections. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/population-estimates-and-projections# (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Goldstein-Greenwood, J. A Brief on Brier Scores. Available online: https://library.virginia.edu/data/articles/a-brief-on-brier-scores (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- Shoman, H.; Karafillakis, E.; Rawaf, S. The link between the West African Ebola outbreak and health systems in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone: a systematic review. Glob Health 2017, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, J.; Biggs, B. The Impact of Conflict on Immunisation Coverage in 16 Countries. Int J Health Policy Manag 2019, 8, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, A.; Crawshaw, A.F.; Carter, J.; Knights, F.; Iwami, M.; Darwish, M.; Hossain, R.; Immordino, P.; Kaojaroen, K.; Severoni, S.; et al. Defining drivers of under-immunization and vaccine hesitancy in refugee and migrant populations. J Travel Med 2023, 30, taad084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Response to Measles Outbreaks in Measles Mortality Reduction Settings: Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals.; 2009.

- Delport, D.; Sanderson, B.; Sacks-Davis, R.; Vaccher, S.; Dalton, M.; Martin-Hughes, R.; Mengistu, T.; Hogan, D.; Abeysuriya, R.; Scott, N. A Framework for Assessing the Impact of Outbreak Response Immunization Programs. Diseases 2024, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Health system indicator | Large measles outbreaks (N = 30) | Non-large measles outbreaks (N = 23) |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of births delivered in a health facility (%)* | 74.90 (35.40, 98.20) | 88.55 (57.40, 98.90) |

| Number of nurses and midwives (per 10,000 population)* | 11.24 (4.10, 42.34) | 19.36 (6.95, 32.45) |

| Health expenditure (per capita in US$)* | 18.80 (8.05, 131.28) | 97.16 (15.32, 249.70) |

| Input variable | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence intervals | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of births delivered in a health facility (%) | 0.99 | (0.95, 1.02) | 0.49 |

| Number of nurses and midwives (per 10,000 population) | 1.02 | (0.98, 1.06) | 0.33 |

| Health expenditure (per capita in US$) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.00) | 0.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).