Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The Information Technology (IT) industry is not only an emerging global sector but also has the potential to support various business verticals. The rapid pace at which we demand and process information, and the significant convenience it brings to our lives, is remarkable. However, it is important to recognize that the IT industry, particularly the general computing sector, significantly contributes to energy consumption and carbon emissions. This systematic review aims to identify the key requirements for greening emerging technologies. The main objective of this study includes examining sources of energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions within the IT sector and exploring the potential of various IT technologies to improve energy efficiency. This review study adopted systematic review processes that involved filtering 1988 academic articles down to 374 relevant studies, focusing on seven technologies: cloud computing, mobile computing, Internet of Things, big data analytics, networking, blockchain technology, and AI. Findings of this review study reveal a classification framework for these technologies, highlighting their unique contributions and potential for energy savings. The study emphasizes the importance of adopting cross-technology techniques to enhance sustainability. This review study demonstrateds by developing a comprehensive understanding of each technology's role in energy conservation and proposing integrative approaches to greening IT. This work provides a valuable reference for organizations aiming to implement green practices and supports future research in sustainable IT solutions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Emerging IT Technologies Background

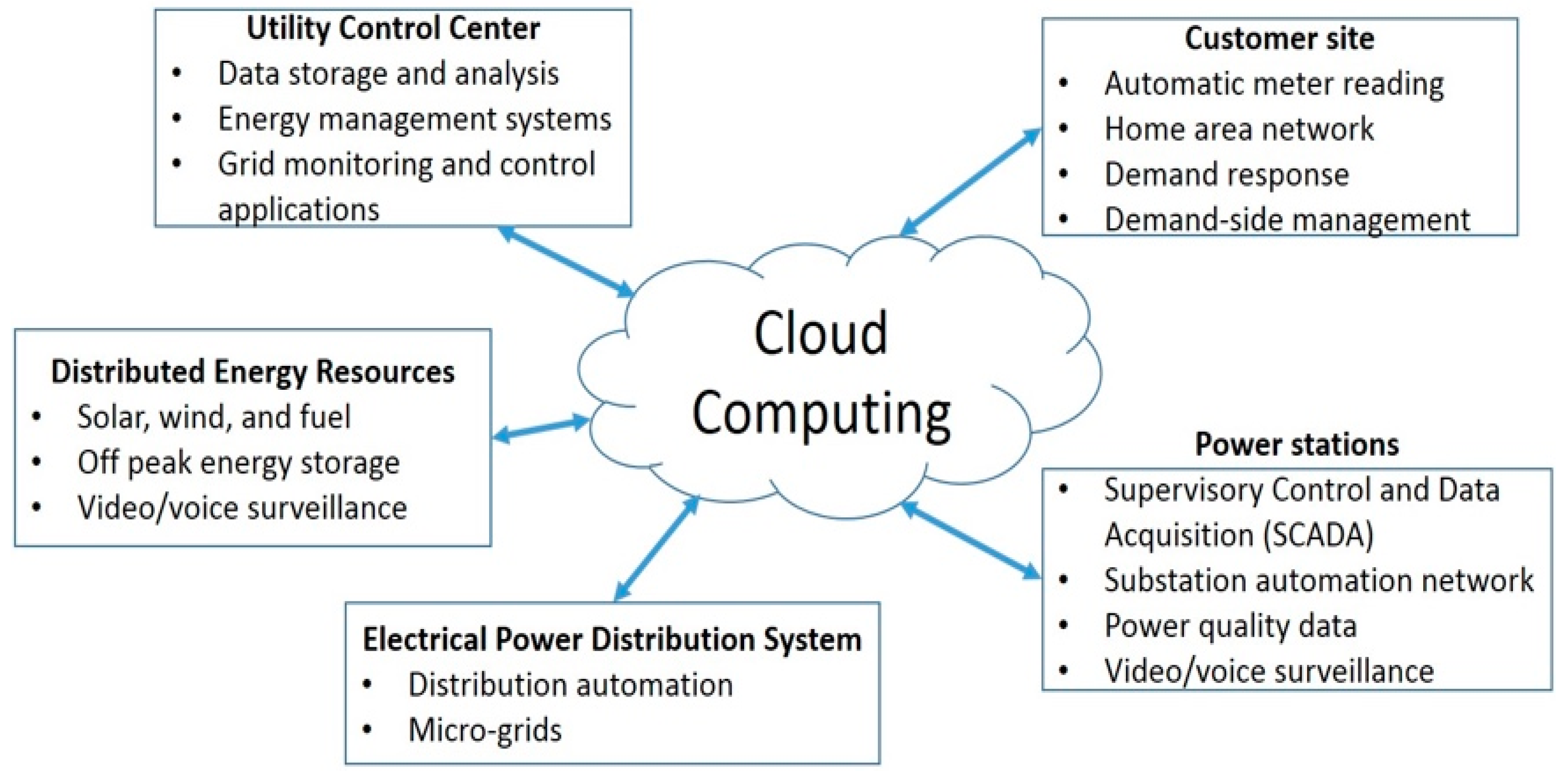

2.1. Cloud Computing

2.2. Mobile Computing

2.3. Internet of Things (IoT)

2.4. Big Data Analytics

2.5. Blockchain Technology

2.6. Artificial Intelligence (AI)

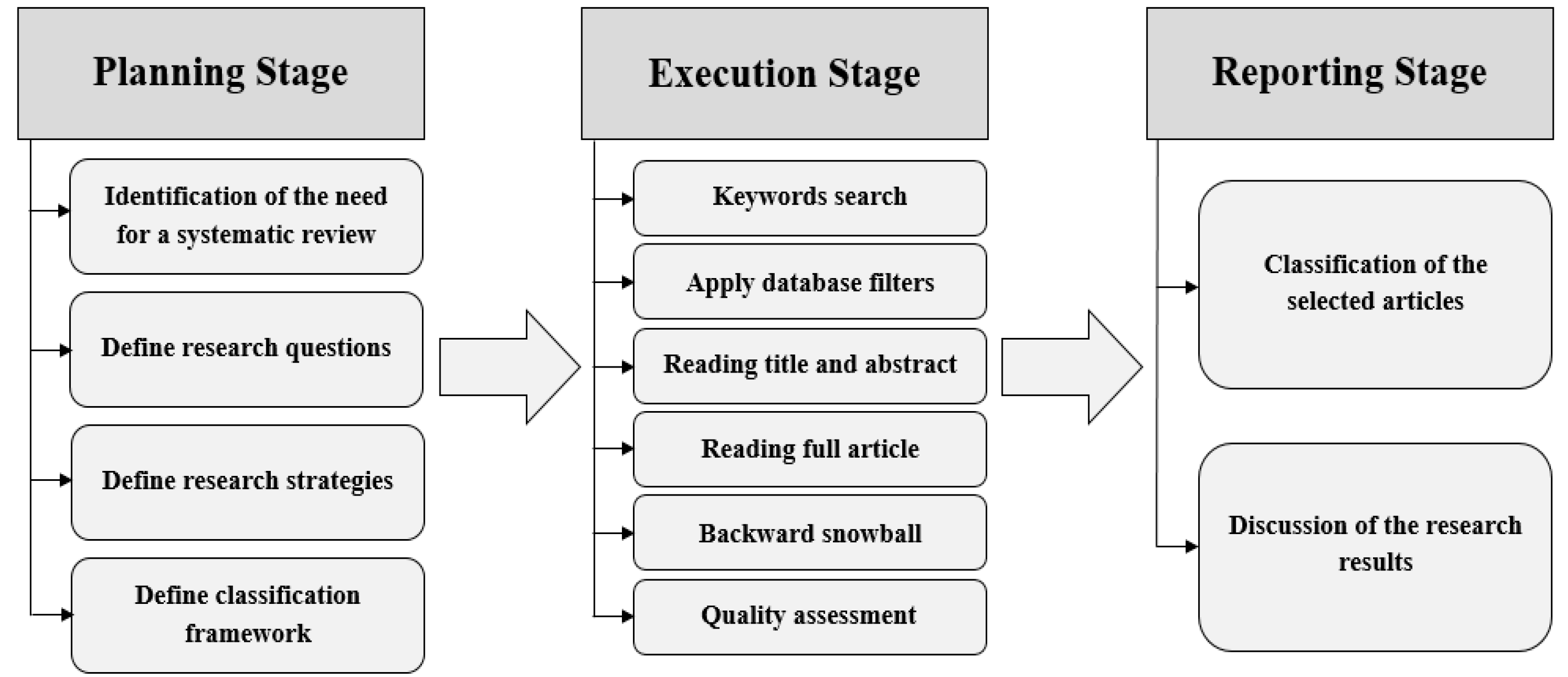

3. Review Planning and Methodology

3.1. Planning Stage

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of publication | Scholarly articles | Reports and any other sources | To ensure that the research retrieves information of academic level sources. |

| Peer-reviewed | Peer-reviewed | Non-peer-reviewed | To ensure the high quality of the used articles. |

| Publication year | Articles published from 2012 to 2022 | Articles that published prior to 2012 | To ensure the validity of the content in any article used in this research review. The pace of technology changes is relatively rapid and the past 10 years is an appropriate time period when the authors can observe the recent trends. |

| Language | English language | Any language other than English | English is the official language of research articles. |

3.2. Execution Stage

3.3. Summarizing Stage

3.4. Common Characteristics related to Selected Articles

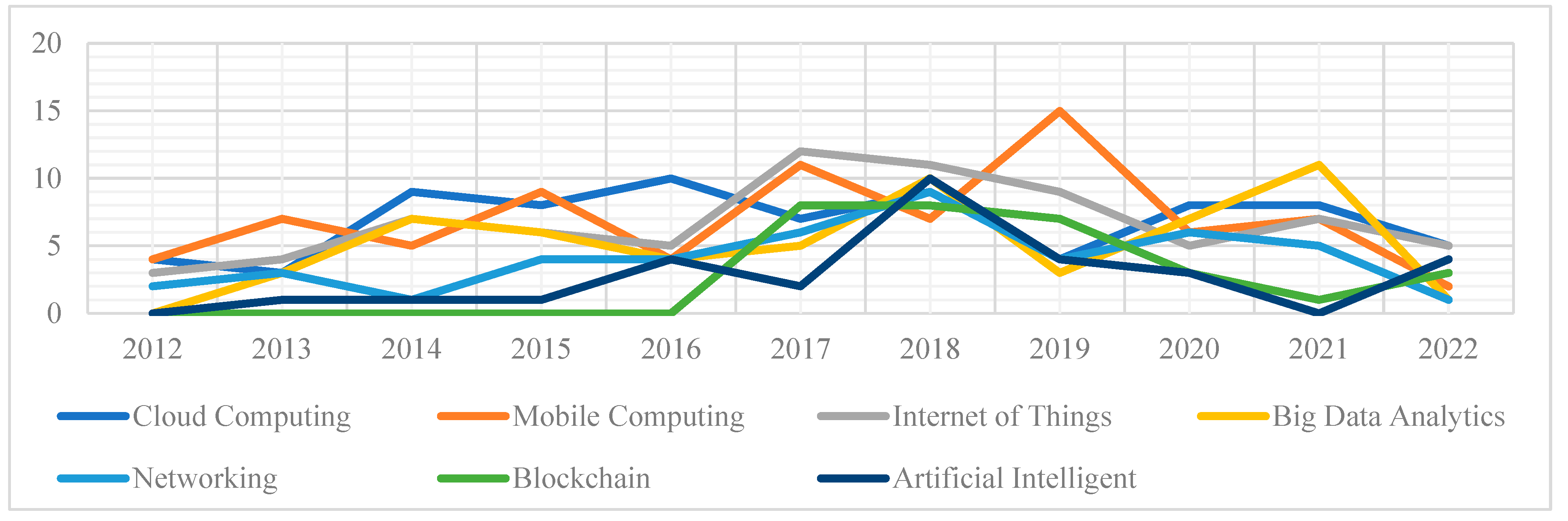

3.4.1. Temporal distribution

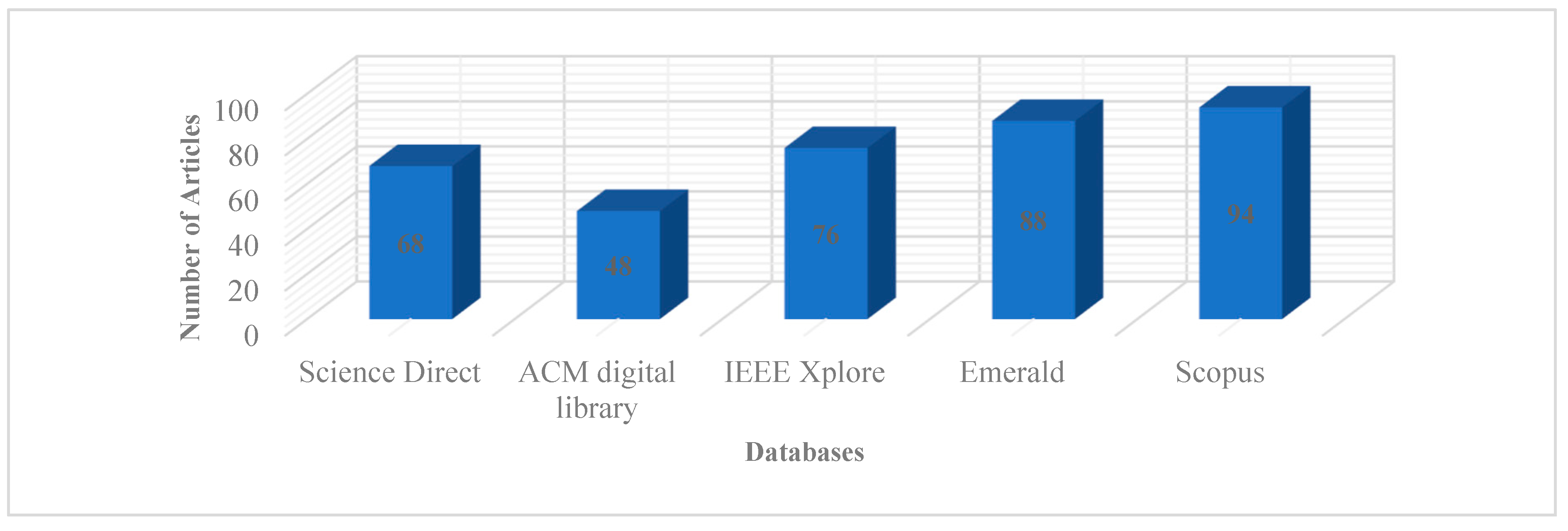

3.4.2. Distribution of Articles by Database

3.4.3. Article distribution Affording to Classification Framework

3.5. Research Synthesis and Propositions

4. Research Discussion

4.1. Cloud Computing

4.2. Mobile Computing

4.3. Internet of Things

4.3.1. Green Radio-Frequency Identification

4.3.2. Green Wireless Sensor Network

4.3.3. Green Machine-to-Machine Communication

4.4. Big Data Analytics

4.5. Networking

4.6. Blockchain Technology

- Encryption of energy savingsx: Encrypting energy savings data and sharing it over a blockchain can secure the energy efficiency market by preventing unauthorized access. Energy baseline and savings data are crucial assets, underpinning various transactions from bank payments to fees for energy service companies and technology providers. Securing this data is critical in today's digitalized world, and blockchain offers a solution for protecting customer energy savings data.

- Exchange of energy savings: Beyond P2P energy trading of excess electricity generation, blockchain technology holds potential for trading energy savings within local communities. Energy savings data could be encrypted and stored on a blockchain platform, enabling transactions for balancing energy bills or purchasing additional energy services.

4.7. Artificial Intelligence

5. Research Implications

5.1. Implications to Theory

5.2. Implications to Research

5.3. Implications to Practice

6. Research Limitation

7. Conclusion

References

- Gooneratne, C. P., Magana-Mora, A., Contreras Otalvora, W., Affleck, M., Singh, P., Zhan, G. D., & Moellendick, T. E. (2020). Drilling in the Fourth Industrial Revolution—Vision and Challenges. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 48(4), 144–159. [CrossRef]

- Andri, R., Cavigelli, L., Rossi, D., & Benini, L. (2016). YodaNN: An Ultra-Low Power Convolutional Neural Network Accelerator Based on Binary Weights. 2016 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI). [CrossRef]

- Armeniakos, G., Zervakis, G., Soudris, D., Henkel, J., 2022. Hardware Approximate Techniques for Deep Neural Network Accelerators: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. Just Accepted (March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M., Al-Fuqaha, A., Sorour, S., & Guizani, M., (2018). Deep Learning for IoT Big Data and Streaming Analytics: A Survey, in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 2923-2960, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Gu, T., & Zhang, X. (2022), MDLdroid: A ChainSGD-Reduce Approach to Mobile Deep Learning for Personal Mobile Sensing, in IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 134-147. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K., Pasricha, S., Kim, RG. (2020), A Survey of Resource Management for Processing-In-Memory and Near-Memory Processing Architectures. Journal of Low Power Electronics and Applications. 10(4):30. [CrossRef]

- Ding, R., Liu, Z., Blanton, R. D. S., & Marculescu, D. (2018). "Quantized deep neural networks for energy efficient hardware-based inference," 2018 23rd Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC), pp. 1-8.

- Azzouni, A., Boutaba, R., & Pujolle, G. (2017). NeuRoute: Predictive dynamic routing for software-defined networks," 2017 13th International Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM), pp. 1-6.

- Wang, E., Davis, JJ., Zhao R., Ng, H-C., Niu X., Luk, W., Cheung, PY. & Constantinides GA. (2019) Deep neural network approximation for custom hardware: where we’ve been, where we’re going. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 52, 40.

- Mirjalili, S. (2015) How effective is the Grey Wolf optimizer in training multi-layer perceptrons. Appl Intell 43, 150–161. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li et al. (2019). HEIF: Highly Efficient Stochastic Computing-Based Inference Framework for Deep Neural Networks, IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 38, no. 8, pp. 1543-1556. [CrossRef]

- Boutaba, R., Salahuddin, M.A., Limam, N. et al. (2018). A comprehensive survey on machine learning for networking: evolution, applications and research opportunities. J Internet Serv Appl 9, 16. [CrossRef]

- Shafik, R., Yakovlev, A., Das, S. (2018) Real-power computing. IEEE Trans. Comput. 67, 1445–1461. [CrossRef]

- Qiqieh, I., Shafik, R., Tarawneh, G., Sokolov, D., Das, S. & Yakovlev, A. (2018) Significance-driven logic compression for energy-efficient multiplier design. IEEE J. Emerg. Selected Top. Circuits Syst. 8, 417–430. [CrossRef]

- Mrazek, V., Sarwar, SS., Sekanina, L., Vasicek, Z., Roy, K. (2016) Design of power-efficient approximate multipliers for approximate artificial neural networks. In Proc. IEEE/ACM Int. Conf. on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD), Austin, TX, 7–10. pp. 1–7. New York, NY: IEEE.

- Lei, J., Wheeldon, A., Shafik, R., Yakovlev, A. & Granmo, O. –C. (2020) From Arithmetic to Logic based AI: A Comparative Analysis of Neural Networks and Tsetlin Machine, 27th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), pp. 1-4.

- Siomau, M. (2014). A quantum model for autonomous learning automata. Quantum Inf Process 13, 1211–1221. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Chen, T., Xu, Z., Sun, N., & Temam, O. (2016). DianNao family: energy-efficient hardware accelerators for machine learning. Commun. ACM 59, 11, 105–112. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G., Dubey, A., Tan, C., & Mitra, T. (2018) Synergy: an HW/SW framework for high throughput CNNs on embedded heterogeneous SoC. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 18. [CrossRef]

- Misra, N. N., Dixit, Y., Al-Mallahi, A., Bhullar, M. S., Upadhyay, R., & Martynenko, A. (2022). IoT, Big Data, and Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture and Food Industry, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 6305-6324. [CrossRef]

- Li, Bh., Hou, Bc., Yu, Wt. et al. (2017) Applications of artificial intelligence in intelligent manufacturing: a review. Frontiers Inf Technol Electronic Eng 18, 86–96. [CrossRef]

- Benini, L., (2017). Plenty of room at the bottom: micropower deep learning for cognitive cyber physical systems. Proc. 7th IEEE Int. Workshop on Advances in Sensors and Interfaces (IWASI), Vieste, Italy, 15–16 June 2017, pp. 165–165. New York, NY.

- Yaseen, M. U., Anjum, A., Rana, O., & Antonopoulos, N., (2019). Deep Learning Hyper-Parameter Optimization for Video Analytics in Clouds, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 253-264. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A., Knezevic, M., Leander, G., Toz, D., Varici, K., & Verbauwhede, I. (2013). SPONGENT: The Design Space of Lightweight Cryptographic Hashing, IEEE Transactions on Computers, vol. 62, no. 10, pp. 2041-2053.

- Lei, J., Wheeldon, A., Shafik, R., Yakovlev, A., & Granmo, O. -C., (2020). From Arithmetic to Logic based AI: A Comparative Analysis of Neural Networks and Tsetlin Machine," 27th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), pp. 1-4.

- Fyrbiak, M., et al. (2019). HAL—The Missing Piece of the Puzzle for Hardware Reverse Engineering, Trojan Detection and Insertion, IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 498-510. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., et al., (2022). Joint Shareability and Interference for Multiple Edge Application Deployment in Mobile-Edge Computing Environment, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 1762-1774. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Peng, Q., Xia, Y., & Lee, J. (2019). Mobility-Aware Tasks Offloading in Mobile Edge Computing Environment, Seventh International Symposium on Computing and Networking (CANDAR), pp. 204-210. [CrossRef]

- Nurvitadhi, E., Sheffield, D., Sim, J., Mishra, A., Venkatesh, G., & Marr, D., (2016). Accelerating Binarized Neural Networks: Comparison of FPGA, CPU, GPU, and ASIC, International Conference on Field-Programmable Technology (FPT), pp. 77-84. [CrossRef]

- Javaid, N., Sher, A., Nasir, H., Guizani, N. (2018). Intelligence in IoT-based 5G networks: opportunities and challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 56, 94–100. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A., Chandrakasan, AP., (2018). Conv-RAM: an energy-efficient SRAM with embedded convolution computation for low-power CNN-based machine learning applications. Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, 11–18 February 2018, pp. 488–490. New York, NY: IEEE.

- Neftci, EO., (2018). Data and power efficient intelligence with neuromorphic learning machines. iScience 5, 52–68. [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, S.S., Adebayo, T.S., Nakorji, M. et al. (2022). Impacts of globalization and energy consumption on environmental degradation: what is the way forward to achieving environmental sustainability targets in Nigeria? Environ Sci Pollut Res. [CrossRef]

- Tao, X., Han, Y., Xu, X. et al. (2017). Recent advances and future challenges for mobile network virtualization. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 60, 040301. [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, F. Z., Bredel, M., Schaller, S., & Schneider, F., (2017), NFV and SDN—Key Technology Enablers for 5G Networks, IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 35, no. 11, pp. 2468-2478. [CrossRef]

- Sun, G., Zhou, R., Sun, J., Yu, H., & Vasilakos, A. V., (2020). Energy-Efficient Provisioning for Service Function Chains to Support Delay-Sensitive Applications in Network Function Virtualization, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 7, no. 7, pp. 6116-6131. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., (2020). Energy Efficient NFV Resource Allocation in Edge Computing Environment, International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), pp. 477-481. [CrossRef]

- Alam, I., Sharif, K., Li, F., Latif, Z., Karim, M. M., Biswas, S., Nour, B., & Wang, Y., (2020). A Survey of Network Virtualization Techniques for Internet of Things Using SDN and NFV. ACM Comput. Surv. 53, 2, Article 35 (March 2021), 40 pages. [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, S., Ramar, R., Hussain, I., Kavin, BP., Alshamrani. SS., AlGhamdi, AS., Alshehri, A. (2022). Predicting Attack Pattern via Machine Learning by Exploiting Stateful Firewall as Virtual Network Function in an SDN Network. Sensors. 22(3):709. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L., Wen, X., Wang, L., Lu, Z., & Knopp, R., (2018). An SDN/NFV based framework for management and deployment of service based 5G core network, China Communications, vol. 15, no. 10, pp. 86-98. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K., Mangat, V., Kumar, K., (2020). A comprehensive survey of service function chain provisioning approaches in SDN and NFV architecture, Computer Science Review, Volume 38, 100298. [CrossRef]

- Taleb, T., Samdanis, K., Mada, B., Flinck, H., Dutta, S., & Sabella, D., (2017). On Multi-Access Edge Computing: A Survey of the Emerging 5G Network Edge Cloud Architecture and Orchestration," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 1657-1681. [CrossRef]

- Demirci, S., Demirci, M., & Sagiroglu, S., (2018). Optimal Placement of Virtual Security Functions to Minimize Energy Consumption, International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC), pp. 1-6.

- Jain, R., & Paul, S., (2013). Network virtualization and software defined networking for cloud computing: a survey, IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 51, no. 11, pp. 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Toosi, A. N. Son, J., Chi, Q., Buyya, R., (2019). ElasticSFC: Auto-scaling techniques for elastic service function chaining in network functions virtualization-based clouds, Journal of Systems and Software, Volume 152, Pages 108-119. [CrossRef]

- Soares, J., Dias, M., Carapinha, J., Parreira, B., & Sargento, S., (2014). Cloud4NFV: A platform for Virtual Network Functions, IEEE 3rd International Conference on Cloud Networking (CloudNet), pp. 288-293.

- Herrera, J. G., & Botero, J. F., (2016). Resource Allocation in NFV: A Comprehensive Survey, IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 518-532. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R., Aujla, G. S., Garg, S., Kumar, N., & Rodrigues, J. J. P. C., (2018). SDN-Enabled Multi-Attribute-Based Secure Communication for Smart Grid in IIoT Environment, IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 2629-2640. [CrossRef]

- Hu, N., Tian, Z., Du, X., Guizani, N., & Zhu, Z., (2021). Deep-Green: A Dispersed Energy-Efficiency Computing Paradigm for Green Industrial IoT, IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 750-764. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, D. B., & Reddy, S. R., (2017). Software Defined Networking Architecture, Security and Energy Efficiency: A Survey, IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 325-346. [CrossRef]

- Son, J., & Buyya, R., (2018). A Taxonomy of Software-Defined Networking (SDN)-Enabled Cloud Computing. ACM Comput. Surv. 51, 3, Article 59 (May 2019), 36 pages. [CrossRef]

- Caprolu, M., Raponi, S., & Pietro, R. D., (2019). FORTRESS: An Efficient and Distributed Firewall for Stateful Data Plane SDN, Security and Communication Networks, vol. 2019, Article ID 6874592, 16 pages. [CrossRef]

- Liang, K., Zhao, L., Chu, X., & Chen, H., (2017). An Integrated Architecture for Software Defined and Virtualized Radio Access Networks with Fog Computing, IEEE Network, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 80-87. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q., & Yu, F. R., (2015). Distributed denial of service attacks in software-defined networking with cloud computing, IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 52-59. [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, I., Taleb, T., Samdanis, K., Ksentini, A., & Flinck, H., (2018). Network Slicing and Softwarization: A Survey on Principles, Enabling Technologies, and Solutions, IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 2429-2453. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, N., Pan, C., Wang, S., & Yin, C., (2020). Joint resource allocation and computation offloading in mobile edge computing for SDN based wireless networks, Journal of Communications and Networks, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q., Ansari, N., & Toy, M., (2016). Software-defined network virtualization: an architectural framework for integrating SDN and NFV for service provisioning in future networks, IEEE Network, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 10-16. [CrossRef]

- Son, J., Dastjerdi, A. V., Calheiros, R. N., & Buyya, R., (2017). SLA-Aware and Energy-Efficient Dynamic Overbooking in SDN-Based Cloud Data Centers, IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 76-89. [CrossRef]

- Haque, I. T., & Abu-Ghazaleh, N., (2016). Wireless Software Defined Networking: A Survey and Taxonomy, IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 2713-2737. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Jin, H., Wen, Y., & Leung V. C. M., (2013). Enabling technologies for future data center networking: a primer, IEEE Network, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 8-15. [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, F. Z., Bredel, M., Schaller, S., & Schneider, F., (2017). NFV and SDN—Key Technology Enablers for 5G Networks, IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 35, no. 11, pp. 2468-2478. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, HC., Lee, CS. & Chen, JL. (2018). Mobile Edge Computing Platform with Container-Based Virtualization Technology for IoT Applications. Wireless Pers Commun 102, 527–542. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., & Hämmäinen, H., (2015). Cost efficiency of SDN in LTE-based mobile networks: Case Finland, International Conference and Workshops on Networked Systems (NetSys), pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Abuarqoub A., (2020). A Review of the Control Plane Scalability Approaches in Software Defined Networking. Future Internet. 12(3):49. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, A., Sakadasariya, A., & Patel, J., (2018). Software defined network: Future of networking, 2nd International Conference on Inventive Systems and Control (ICISC), pp. 1351-1354.

- Tang, M., & Pan, S., (2015). A Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for the Energy-Efficient Virtual Machine Placement Problem in Data Centers. Neural Process Lett 41, 211–221. [CrossRef]

- Montazerolghaem, A., Yaghmaee, M. H., & Leon-Garcia, A., (2020). Green Cloud Multimedia Networking: NFV/SDN Based Energy-Efficient Resource Allocation, IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 873-889. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., & Gu, S., (2021). Industry 4.0, a revolution that requires technology and national strategies. Complex Intell. Syst. 7, 1311–1325. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, B. G., & Özkasap, Ö., (2019). A survey of energy efficiency in SDN: Software-based methods and optimization models, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 137, Pages 127-143. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, K., Khan, S.U., Madani, S.A. et al., (2013). A survey on Green communications using Adaptive Link Rate. Cluster Comput 16, 575–589. [CrossRef]

- Zeadally, S., Khan, S.U. & Chilamkurti, N., (2012). Energy-efficient networking: past, present, and future. J Supercomput 62, 1093–1118. [CrossRef]

- Luitel, S., & Moh, S., (2018). Energy-Efficient Medium Access Control Protocols for Cognitive Radio Sensor Networks: A Comparative Survey. Sensors. 18(11):3781. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, P.S., Chatterjee, J.M., Kumar, A. et al. (2021). Energy-efficient cluster head selection through relay approach for WSN. J Supercomput 77, 7649–7675. [CrossRef]

- Tuysuz, M. F., Ankarali, Z. K., & Gözüpek, D., (2017). A survey on energy efficiency in software defined networks, Computer Networks, Volume 113, Pages 188-204, ISSN 1389-1286. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Zhang, Y., Zukerman, M., & Yung, E. K. -N., (2015). Energy-Efficient Base-Stations Sleep-Mode Techniques in Green Cellular Networks: A Survey, IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 803-826. [CrossRef]

- Popoola, O., & Pranggono, B. (2018). On energy consumption of switch-centric data center networks. J Supercomput 74, 334–369. [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi, M. H., & Sawyer, S., (2019). Networks of innovation: the sociotechnical assemblage of tabletop computing, Research Policy, Volume 48, Supplement, 100001. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. A., Rehmani, M. H., & Rachedi, A., (2016). When Cognitive Radio meets the Internet of Things? International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC),pp. 469-474. [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R., Zahoor, S., Shah, M. A., Wahid, A., & Yu, H., (2017). Green IoT: An Investigation on Energy Saving Practices for 2020 and Beyond, IEEE Access, vol. 5, pp. 15667-15681. [CrossRef]

- Molla, A., Abareshi, A., & Cooper, V., (2014). Green IT beliefs and pro-environmental IT practices among IT professionals, Information Technology & People, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 129-154. [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M., Chierici, R., Mazzucchelli, A. and Fiano, F., (2021). "Supply chain management in the era of circular economy: the moderating effect of big data", The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 32 No. 2, pp. 337-356. [CrossRef]

- Hypolite, J., Sonchack, J., Hershkop, S., Dautenhahn, N., DeHon, A., & Smith, J. M., (2020). DeepMatch: practical deep packet inspection in the data plane using network processors. 16th International Conference on emerging Networking EXperiments and Technologies (CoNEXT '20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 336–350. [CrossRef]

- Thein, T., Myo, M. M., Parvin, S., & Gawanmeh, A., Reinforcement learning based methodology for energy-efficient resource allocation in cloud data centers, Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, Volume 32, Issue 10, Pages 1127-1139. [CrossRef]

- Shortall, R., Davidsdottir, B., & Axelsson, G., (2015). Geothermal energy for sustainable development: A review of sustainability impacts and assessment frameworks, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 44, Pages 391-406. [CrossRef]

- Fais, B., Sabio, N., & Strachan, N., (2016). The critical role of the industrial sector in reaching long-term emission reduction, energy efficiency and renewable targets, Applied Energy, Volume 162, Pages 699-712. [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S. E., & Krogstie, J. (2021). A Novel Model for Data-Driven Smart Sustainable Cities of the Future: A Strategic Roadmap to Transformational Change in the Era of Big Data. Future Cities and Environment, 7(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, T., Sekaran, K. C., & Jose, J., (2014). Study and analysis of various task scheduling algorithms in the cloud computing environment, International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), 2014, pp. 658-664.

- Del Giudice, M., Chierici, R., Mazzucchelli, A. and Fiano, F. (2021), "Supply chain management in the era of circular economy: the moderating effect of big data", The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 32 No. 2, pp. 337-356. [CrossRef]

- Çavdar, D., & Alagoz, F., (2012). A survey of research on greening data centers, IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), 2012, pp. 3237-3242. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M. H., Ahmed, E., Yaqoob, I., Hashem, I. A. T., Imran, M., & Ahmad, S., (2018). Big Data Analytics in Industrial IoT Using a Concentric Computing Model, IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 37-43. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D., Wang, Y., Lv, Z., Wang, W., & Wang, H., An Energy-Efficient Networking Approach in Cloud Services for IIoT Networks, IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 928-941. [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, A., & Gezen, M., (2022). The evaluation of renewable energy resources in Turkey by integer multi-objective selection problem with interval coefficient, Renewable Energy, Volume 182, Pages 842-854. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Khan, S.U., (2013). Review of performance metrics for green data centers: a taxonomy study. J Supercomput 63, 639–656. [CrossRef]

- He, W., Wang, F.-K. and Akula, V. (2017), "Managing extracted knowledge from big social media data for business decision making", Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 275-294. [CrossRef]

- Hashem, I. A. T., Anuar, N. B., Gani, A., Yaqoob, I., Xia, F., & Khan S. U., (2016). Mapreduce: Review and open challenges. Scientometrics. 20161–34. [CrossRef]

- Awaysheh, F. M., Aladwan, M. N., Alazab, M., Alawadi, S., Cabaleiro, J. C., & Pena, T. F., (2020). Security by Design for Big Data Frameworks Over Cloud Computing, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E., Yaqoob, I., Hashem, I. A. T., Khan, I., Ahmed, A. I. A., Imran, M, & Vasilakos, A. V., (2017). The role of big data analytics in Internet of Things Computer Networks, Volume 129, Part 2, Pages 459-471. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A., Tanwar, S., Tyagi, S., & Kumar, N., (2018). Michele Maasberg, Kim-Kwang Raymond Choo, Multimedia big data computing and Internet of Things applications: A taxonomy and process model, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 124, Pages 169-195. [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, C., Psannis, K. E., Gupta, B. B., & Ishibashi, Y., (2018). Security, privacy & efficiency of sustainable Cloud Computing for Big Data & IoT, Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems, Volume 19, Pages 174-184. [CrossRef]

- Montori, F., Bedogni, L., Di Felice, M., & Bononi, L., (2018). Machine-to-machine wireless communication technologies for the Internet of Things: Taxonomy, comparison and open issues, Pervasive and Mobile Computing, Volume 50, Pages 56-81. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A., Natgunanathan, I., Xiang, Y., Hua, G., & Guo, S., (2016). Protection of Big Data Privacy, IEEE Access, vol. 4, pp. 1821-1834. [CrossRef]

- Farhan, L., Kharel, R., Kaiwartya, O., Quiroz-Castellanos, M., Alissa, A., & Abdulsalam, M., (2018). A Concise Review on Internet of Things (IoT) -Problems, Challenges and Opportunities,” 11th International Symposium on Communication Systems, Networks & Digital Signal Processing (CSNDSP), pp. 1-6.

- Syed, H. J., Gani, A., Ahmad, R. W., Khan, M. K., & Ahmed, A. I. A., (2017). Cloud monitoring: A review, taxonomy, and open research issues, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 98, Pages 11-26. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, A. K., (2022). Big data with cloud computing: Discussions and challenges, Big Data Mining and Analytics, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 32-40. [CrossRef]

- Xinhua, E., Han, J., Wang, Y., & Liu, L., Big Data-as-a-Service: Definition and architecture, 15th IEEE International Conference on Communication Technology, pp. 738-742.

- Sundaran, K., Ganapathy, V., & Sudhakara, P., (2017). Fuzzy logic based Unequal Clustering in wireless sensor network for minimizing Energy consumption, 2nd International Conference on Computing and Communications Technologies (ICCCT), pp. 304-309. [CrossRef]

- Netto, M. A. S., Calheiros, R. N., Rodrigues, E. R., Cunha, R. L. F., & Buyya, R., (2019). HPC Cloud for Scientific and Business Applications: Taxonomy, Vision, and Research Challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 51, 1, Article 8, 29 pages. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jarrah, OY., Yoo, PD., Muhaidat, S., Karagiannidis GK., & Taha, K., (2015). Efficient machine learning for big data: A review. Big Data Res. ;2(3):87–93. [CrossRef]

- Miao, K., Li, J., Hong, W., & Chen, M., (2020). A Microservice-Based Big Data Analysis Platform for Online Educational Applications, Scientific Programming, vol. Article ID 6929750, 13 pages, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Kung, L., & Byrd, T. A., (2018). Big data analytics: Understanding its capabilities and potential benefits for healthcare organizations, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Volume 126, Pages 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Liu, Q., Luo, Y., Peng, K., Zhang, X., Meng, S., & Qi, L., (2019). A computation offloading method over big data for IoT-enabled cloud-edge computing, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 95, Pages 522-533. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Cao, J., Sherratt, R.S. et al. (2018) An improved ant colony optimization-based approach with mobile sink for wireless sensor networks. J Supercomput 74, 6633–6645. [CrossRef]

- Elgendy, N., Elragal, A. (2014). Big Data Analytics: A Literature Review Paper. In: Perner, P. (eds) Advances in Data Mining. Applications and Theoretical Aspects. ICDM 2014. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 8557. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, M., Duggal, R., & Khatri, S. K., (2015). Unravelling unstructured data: A wealth of information in big data, 4th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (ICRITO) (Trends and Future Directions), pp. 1-6.

- Kumar, A., & Hancke, G. P., (2014). Energy Efficient Environment Monitoring System Based on the IEEE 802.15.4 Standard for Low Cost Requirements, IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 2557-2566. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, P. S., & Pillai, A. S., (2020). Big Data solutions in Healthcare: Problems and perspectives, International Conference on Innovations in Information, Embedded and Communication Systems (ICIIECS), pp. 1-6.

- Kantareddy, S. N. R. et al., (2020) Perovskite PV-Powered RFID: Enabling Low-Cost Self-Powered IoT Sensors, Sensors Journal, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 471-478. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, SH., Lee, J., & Choi, JK., (2014). An adaptive reporting frequency control scheme for energy saving on wireless sensor networks. In: Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), International Conference on. IEEE; p. 39–44.

- Duroc, Y., & Kaddour, D., (2012) RFID Potential Impacts and Future Evolution for Green Projects, Energy Procedia, Volume 18, Pages 91-98. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Chang, R., & Chan, H., (2014). A green energy-efficient scheduling algorithm using the DVFS technique for cloud datacenters, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 37, Pages 141-147. [CrossRef]

- Beneventi, F., Bartolini, A., Cavazzoni, C. & Benini, L., (2017). Continuous learning of HPC infrastructure models using big data analytics and in-memory processing tools, Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), pp. 1038-1043.

- Li, D., & Halfond, W. G. J., (2014). An investigation into energy-saving programming practices for Android smartphone app development. Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Green and Sustainable Software (GREENS). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Benzidia, S., Makaoui, N., & Bentahar, O., (2021). The impact of big data analytics and artificial intelligence on green supply chain process integration and hospital environmental performance, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Volume 165, 120557. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., Lin, W., Hsu, C., & He, L., (2018). Energy-efficient hadoop for big data analytics and computing: A systematic review and research insights, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 86, Pages 1351-1367. [CrossRef]

- Aceto, G., Persico, V., & Pescapé, A., (2020). Industry 4.0 and Health: Internet of Things, Big Data, and Cloud Computing for Healthcare 4.0, Journal of Industrial Information Integration, Volume 18, 100129. [CrossRef]

- Palomba, F., Di Nucci, D., Panichella, A., Zaidman, A., & De Lucia, A., (2019). On the impact of code smells on the energy consumption of mobile applications, Information and Software Technology, Volume 105, Pages 43-55. [CrossRef]

- Luvisi, A., (2016). Electronic identification technology for agriculture, plant, and food. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 36, 13. [CrossRef]

- Popli, S., Jha, R. K., & Jain, S., (2022). Green IoT: A Short Survey on Technical Evolution & Techniques. Wireless Pers Commun 123, 525–553. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J., & McGovern, C., (2022). A qualitative study of improving the operations strategy of logistics using radio frequency identification, Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Shah, G. A., & Arshad, J., (2016). Energy efficient techniques for M2M communication: A survey, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 68, Pages 42-55. [CrossRef]

- Romeo, L., Petitti, A., Marani, R., & Milella, A., (2020) Internet of Robotic Things in Smart Domains: Applications and Challenges. Sensors; 20(12):3355. [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, D., & Abas, S., (2020). Modified Clustering Algorithms for Energy Harvesting Wireless Sensor Networks- A Survey, 21st International Arab Conference on Information Technology (ACIT), pp. 1-11.

- Li, X., Li, D., Wan, J. et al. (2017). A review of industrial wireless networks in the context of Industry 4.0. Wireless Netw 23, 23–41. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M., Nielsen, R. H., & Prasad, N. R., (2013). The evolution of M2M into IoT, First International Black Sea Conference on Communications and Networking (BlackSeaCom), pp. 112-115.

- Valaskova, K., Ward, P., & Svabova, L., (2021). Deep learning-assisted smart process planning, cognitive automation, and industrial big data analytics in sustainable cyber-physical production systems. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 9(2), 9-20.

- Kantareddy, S. N. R., Mathews, I., Bhattacharyya, R., Peters, I. M., Buonassisi, T., & Sarma, S. E., (2019). Long Range Battery-Less PV-Powered RFID Tag Sensors, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 6989-6996. [CrossRef]

- Moraru, A., Helerea, E., Ursachi, C., & Călin, M. D., (2017). RFID system with passive RFID tags for textiles, 10th International Symposium on Advanced Topics in Electrical Engineering (ATEE), pp. 410-415.

- Escobar, J. J. M., Matamoros, O. M., Padilla, R. T., Reyes, I. L., & Espinosa, H. Q., (2021). A comprehensive review on smart grids: Challenges and opportunities. Sensors, 21(21), 6978. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, T., Abdrabou, A., Shaban, K., & Gaouda, A. M. (2018). Heterogeneous wireless networks for smart grid distribution systems: Advantages and limitations. Sensors, 18(5), 1517. [CrossRef]

- Alvi, H. M., Sahar, H., Bangash, A. A., & Beg, M. O., (2017). EnSights: A tool for energy aware software development, 13th International Conference on Emerging Technologies (ICET), pp. 1-6.

- Rekik, S., Baccour, N., Jmaiel, M. et al., (2017). Wireless Sensor Network Based Smart Grid Communications: Challenges, Protocol Optimizations, and Validation Platforms. Wireless Pers Commun 95, 4025–4047. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., CHEN, Z., YU, T., HUANG, X., & GU, X., (2018). Agricultural remote sensing big data: Management and applications, Journal of Integrative Agriculture, Volume 17, Issue 9, Pages 1915-1931. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, T., Salgado, F., Tavares, A., & Cabral, J., (2017). CUTE Mote, A Customizable and Trustable End-Device for the Internet of Things, IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 17, no. 20, pp. 6816-6824, 15 Oct.15. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R., Carção, T., Couto, M., Cunha, J., Fernandes, J. P., & Saraiva, J., (2017). Helping Programmers Improve the Energy Efficiency of Source Code, IEEE/ACM 39th International Conference on Software Engineering Companion (ICSE-C), pp. 238-240.

- Loganathan, S., & Arumugam, J., (2021). Energy Efficient Clustering Algorithm Based on Particle Swarm Optimization Technique for Wireless Sensor Networks. Wireless Pers Commun 119, 815–843. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., Tschetter, E., Léauté, X., Ray, N., Merlino, G., & Ganguli, D., (2014).. Druid: a real-time analytical data store. Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD '14). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 157–168. [CrossRef]

- He, L., Lee, Y., Kim, E., & Shin, K. G., (2019). Environment-aware estimation of battery state-of-charge for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Cyber-Physical Systems (ICCPS '19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 227–236. [CrossRef]

- Dogra, R., Rani, S., Babbar, H., & Krah, D., (2022). Energy-Efficient Routing Protocol for Next-Generation Application in the Internet of Things and Wireless Sensor Networks, Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, vol. Article ID 8006751, 10 pages, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tian, W., (2013). A review of sensitivity analysis methods in building energy analysis, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 20, Pages 411-419. 20. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z., Zhang, H. H., Xiong, G., Guo, G., Wang, H., Chen, J., Praveen, A., Yang, Y., Gao, X., Wang, A., Lin, W., Agrawal, A., Yang, J., Wu, H., Li, X., Guo, F., Wu, J., Zhang, J., & Raghavan, V., (2021). Greenplum: A Hybrid Database for Transactional and Analytical Workloads. Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD '21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2530–2542. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A., & Sabyasachi, A. S., Cloud computing simulators: A detailed survey and future direction, IEEE International Advance Computing Conference (IACC), pp. 866-872.

- Yassine, A., Singh, S., Hossain, M. S., & Muhammad, G., (2019). IoT big data analytics for smart homes with fog and cloud computing, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 91, Pages 563-573. [CrossRef]

- Khashan, O. A., (2021). Parallel Proxy Re-Encryption Workload Distribution for Efficient Big Data Sharing in Cloud Computing, IEEE 11th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), pp. 0554-0559.

- Hao, S., Li, D., Halfond, W. G. J., & Govindan, R., (2013). Estimating mobile application energy consumption using program analysis, 35th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), pp. 92-101.

- Osanaiye, O. A., Alfa, A. S., & Hancke, G. P., (2018). Denial of Service Defence for Resource Availability in Wireless Sensor Networks, IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 6975-7004. [CrossRef]

- Shah, K. & Narmavala, Z., (2018). A Survey on Green Internet of Things, Fourteenth International Conference on Information Processing (ICINPRO), pp. 1-4.

- Vrchota, J., Pech, M., Rolínek, L., Bednář, J., (2020) Sustainability Outcomes of Green Processes in Relation to Industry 4.0 in Manufacturing: Systematic Review. Sustainability, 12(15):5968. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. H., & Yaqoob, I., (2016). A survey: Internet of Things (IOT) technologies, applications and challenges, IEEE Smart Energy Grid Engineering (SEGE), pp. 381-385.

- Chaudhari, BS., Zennaro, M., & Borkar, S., (2020). LPWAN Technologies: Emerging Application Characteristics, Requirements, and Design Considerations. Future Internet. 12(3):46. [CrossRef]

- Benhamaid, S., Bouabdallah, A., & Lakhlef, H., Recent advances in energy management for Green-IoT: An up-to-date and comprehensive survey, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 198, 103257. [CrossRef]

- Fourty, N., Bossche, A., Val, T., (2012). An advanced study of energy consumption in an IEEE 802.15.4 based network: Everything but the truth on 802.15.4 node lifetime, Computer Communications, Volume 35, Issue 14, Pages 1759-1767. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y., Xing, Z., Fadlullah, Z. M., Yang, J., & Kato, N., (2018). Characterizing Flow, Application, and User Behavior in Mobile Networks: A Framework for Mobile Big Data, IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 40-49. [CrossRef]

- Gu, C., Fan, L., Wu, W., Huang, H., & Jia, X., (2018). Greening cloud data centers in an economical way by energy trading with power grid, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 78, Part 1, Pages 89-101. [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M. A., Siekkinen, M., Koo, J., & Tarkoma, S., (2017). Full Charge Capacity and Charging Diagnosis of Smartphone Batteries, in IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, vol. 16, no. 11, pp. 3042-3055, 1. [CrossRef]

- Sen, P., Kantareddy, S. N. R., Bhattacharyya, R., Sarma, S. E., & Siegel, J. E., (2020). Low-Cost Diaper Wetness Detection Using Hydrogel-Based RFID Tags, IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 3293-3302, 15. [CrossRef]

- Aldeer, M. M. N., (2013). A summary survey on recent applications of wireless sensor networks, IEEE Student Conference on Research and Developement, pp. 485-490.

- Catarinucci, L. et al., (2015). An IoT-Aware Architecture for Smart Healthcare Systems, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 515-526. [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, F., et al., (2021). Data Driven Fleet Monitoring and Circular Economy, 17th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems (DCOSS), pp. 483-488.

- Kang, L., Poslad, S., Wang, W., Li, X., Zhang, Y., & Wang, C., (2016). A Public Transport Bus as a Flexible Mobile Smart Environment Sensing Platform for IoT, 12th International Conference on Intelligent Environments (IE), pp. 1-8.

- Chen, X., Ding, N., Jindal, A., Hu, Y. C., Gupta, M., & Vannithamby, R. (2015). Smartphone Energy Drain in the Wild: Analysis and Implications. SIGMETRICS Perform. Eval. Rev. 43, 1, 151–164. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z., Lou, R., Li, J., Singh, A. K., & Song, H., (2021). Big Data Analytics for 6G-Enabled Massive Internet of Things, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 5350-5359. [CrossRef]

- Yousafzai, A., Yaqoob, I., Imran, M., Gani, A., & Noor, R. Md., (2020). Process Migration-Based Computational Offloading Framework for IoT-Supported Mobile Edge/Cloud Computing, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 4171-4182. [CrossRef]

- Shan, H., Peterson, J., Hathorn, S., & Mohammadi, S., (2018). The RFID Connection: RFID Technology for Sensing and the Internet of Things, IEEE Microwave Magazine, vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 63-79. [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, P., (2018). A novel, cost efficient identification method for disassembly planning of waste electrical and electronic equipment, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 172, Pages 2695-2707. [CrossRef]

- Talal, M., Zaidan, A.A., Zaidan, B.B. et al., (2019). Comprehensive review and analysis of anti-malware apps for smartphones. Telecommun Syst 72, 285–337. [CrossRef]

- Anthony, B., Abdul Majid, M., Romli, A., A generic study on Green IT/IS practice development in collaborative enterprise: Insights from a developing country, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, Volume 55, 101555. [CrossRef]

- Kong, L., He, L., Gu, Y., Wu, M. -Y., & He, T., (2014). A Parallel Identification Protocol for RFID systems, IEEE INFOCOM - IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, pp. 154-162.

- LaPre, J. M., Gonsiorowski, E. J., Carothers, C. D., Jenkins, J., Carns, P., & Ross, R., (2015). Time Warp state restoration via delta encoding, Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), pp. 3025-3036.

- Liu, Y., Wang, H., Fei, Y., Liu, Y., Shen, L., Zhuang, Z., & Zhang, X., (2021). Research on the Prediction of Green Plum Acidity Based on Improved XGBoost. Sensors; 21(3):930. [CrossRef]

- Xia, N., Chen, H. -H., & Yang, C. -S., (2018). Radio Resource Management in Machine-to-Machine Communications—A Survey, IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 791-828.

- Albreem, M. A., Sheikh, A. M., Alsharif, M. H., Jusoh, M. & Mohd, Y. M. N., (2021). Green Internet of Things (GIoT): Applications, Practices, Awareness, and Challenges," IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 38833-38858. [CrossRef]

- Tupe, U.L., Babar, S.D., Kadam, S.P. and Mahalle, P.N., (2022), "Research perspective on energy-efficient protocols in IoT: emerging development of green IoT", International Journal of Pervasive Computing and Communications, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 145-170. [CrossRef]

- Waltho, C., Elhedhli, S., & Gzara, F., (2019). Green supply chain network design: A review focused on policy adoption and emission quantification, International Journal of Production Economics, Volume 208, Pages 305-31. [CrossRef]

- Nam, T. M., Thanh, N. H., Hieu, H. T., Manh, N. T., Huynh, N. V., & Tuan, H. D., (2017). Joint network embedding and server consolidation for energy–efficient dynamic data center virtualization, Computer Networks, Volume 125, Pages 76-89. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. et al., (2019). Energy-Efficient Resource Allocation for Energy Harvesting-Based Cognitive Machine-to-Machine Communications, IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 595-607. [CrossRef]

- Dash, S., Shakyawar, S.K., & Sharma, M. et al. (2019). Big data in healthcare: management, analysis and future prospects. J Big Data 6, 54. [CrossRef]

- Cinquini, L., Crichton, D., Mattmann, C., Harney, J., Shipman, G., Wang, F., Ananthakrishnan, R., Miller, N., Denvil, S., Morgan, M., Pobre, Z., Bell, G. M., Doutriaux, C., Drach, R., Williams, D., Kershaw, P., Pascoe, S., Gonzalez, E., Fiore, S., & Schweitzer, R., (2014). The Earth System Grid Federation: An open infrastructure for access to distributed geospatial data, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 36, Pages 400-417. [CrossRef]

- Jin, ZH., Shi, H., Hu, YX. et al., (2020). CirroData: Yet Another SQL-on-Hadoop Data Analytics Engine with High Performance. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 35, 194–208. [CrossRef]

- Seo, M., Song, Y., Kim, J., Paek, S. W., Kim, G., & Kim, S. W., (2021). Innovative lumped-battery model for state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries under various ambient temperatures, Energy, Volume 226, 120301. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, M., Kor, A-L., Pattinson, C., & Rondeau, E., (2020) Green Cloud Software Engineering for Big Data Processing. Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):9255. [CrossRef]

- Le, H., (2021). Analyzing Energy Leaks of Android Applications Using Event-B. Mobile Netw Appl 26, 1329–1338. [CrossRef]

- Asci, C., Wang, W., & Sonkusale, S., (2020). Security Monitoring System Using Magnetically-Activated RFID Tags, IEEE SENSORS, pp. 1-4.

- Shabtai, A., Kanonov, U., Elovici, Y. et al. (2012). “Andromaly”: a behavioral malware detection framework for android devices. J Intell Inf Syst 38, 161–190. [CrossRef]

- Amutha, J., Sharma, S. & Nagar, J., (2020). WSN Strategies Based on Sensors, Deployment, Sensing Models, Coverage and Energy Efficiency: Review, Approaches and Open Issues. Wireless Pers Commun 111, 1089–1115. [CrossRef]

- Dong, L., Satpute, M. N., Shan, J., Liu, B., Yu, Y. & Yan, T., (2019). Computation Offloading for Mobile-Edge Computing with Multi-user, IEEE 39th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), pp. 841-850.

- Xu, J., Xiang, J., & Yang, D., Incentive Mechanisms for Time Window Dependent Tasks in Mobile Crowdsensing, IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 6353-6364. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F. K., Zeadally, S. & Exposito, E., (2017). Enabling Technologies for Green Internet of Things," IEEE Systems Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 983-994. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Li, X. & Wen, W., (2014). WLCleaner: Reducing Energy Waste Caused by WakeLock Bugs at Runtime, IEEE 12th International Conference on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, pp. 429-434.

- Abbasi, A. M. et al., (2015). A framework for detecting energy bugs in smartphones, 6th International Conference on the Network of the Future (NOF), pp. 1-3.

- Pramanik, P. K. D. et al., (2019). Power Consumption Analysis, Measurement, Management, and Issues: A State-of-the-Art Review of Smartphone Battery and Energy Usage, IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 182113-182172. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L., & Abreu, R., (2019). Catalog of energy patterns for mobile applications. Empir Software Eng 24, 2209–2235. [CrossRef]

- Ha, I., Djuraev, M. & Ahn, B., (2017) An Optimal Data Gathering Method for Mobile Sinks in WSNs. Wireless Pers Commun 97, 1401–1417. [CrossRef]

- Satyaraj, D., & Bhanumathi, V. (2021). Efficient design of dual controlled stacked SRAM cell. Analog Integr Circ Sig Process 107, 369–376. [CrossRef]

- Pedram, M., (2012). Energy-Efficient Datacenters, IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 31, no. 10, pp. 1465-1484.

- Arshad, R., Zahoor, S., Shah, M. A., Wahid, A. & Yu, H., (2017). Green IoT: An Investigation on Energy Saving Practices for 2020 and Beyond, IEEE Access, vol. 5, pp. 15667-15681. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y., You, C., Zhang, J., Huang, K. & Letaief, K. B., (2017). A Survey on Mobile Edge Computing: The Communication Perspective, IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 2322-2358. [CrossRef]

- Boukoberine, M. N., Zhou, Z., & Benbouzid, M., (2019). A critical review on unmanned aerial vehicles power supply and energy management: Solutions, strategies, and prospects, Applied Energy, Volume 255, 113823. [CrossRef]

- Catarinucci, L., Colella, R., Del Fiore, G., et al. (2014). A Cross-Layer Approach to Minimize the Energy Consumption in Wireless Sensor Networks. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks. [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D., Boshell, F., Saygin, D., Bazilian, M. D., Wagner, N., & Gorini, R., (2019) The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation, Energy Strategy Reviews, Volume 24, Pages 38-50. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., Leung, V. C. M., Shu, L. & Ngai, E. C., (2017). Green Internet of Things for Smart World, IEEE Access, vol. 3, pp. 2151-2162. [CrossRef]

- Twayej, W., & Al-Raweshidy, H. S., (2017). An energy efficient M2M routing protocol for IoT based on 6LoWPAN with a smart sleep mode, Computing Conference, pp. 1317-1322.

- Wu, H., Wolter, K., Jiao, P., Deng, Y., Zhao, Y. & Xu, M., (2021). EEDTO: An Energy-Efficient Dynamic Task Offloading Algorithm for Blockchain-Enabled IoT-Edge-Cloud Orchestrated Computing, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 2163-2176, 15.

- Farooq, M. U., Khan, S. U. R., & Beg, M. O., (2019). MELTA: A Method Level Energy Estimation Technique for Android Development, International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC), pp. 1-10.

- Owusu, P. A. & Asumadu-Sarkodie, S., (2016). A review of renewable energy sources, sustainability issues and climate change mitigation, Cogent Engineering, 3:1, 1167990.

- Tupe, U.L., Babar, S.D., Kadam, S.P. and Mahalle, P.N., (2022). Research perspective on energy-efficient protocols in IoT: emerging development of green IoT, International Journal of Pervasive Computing and Communications, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 145-170. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, W., Soban, M., Akhtar, F., & Zaffar, N. A., (2015). Smart meters for industrial energy conservation and efficiency optimization in Pakistan: Scope, technology and applications, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 44, Pages 933-943. [CrossRef]

- Kamaludin, H., Mahdin, H., & Abawajy, JH. (2018). Clone tag detection in distributed RFID systems. PLoS ONE 13(3): e0193951. [CrossRef]

- Balasingam, B., Ahmed, M., & Pattipati, K., (2020). Battery Management Systems—Challenges and Some Solutions. Energies. 13(11):2825. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. K., Amin, S. I., Imam, S. A., Sachan, V. K., & Choudhary, A., A Survey of Wireless Sensor Network and its types, International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking (ICACCCN), pp. 326-330. [CrossRef]

- Galmés, S., & Escolar, S., (2018) Analytical Model for the Duty Cycle in Solar-Based EH-WSN for Environmental Monitoring. Sensors. 18(8):2499. [CrossRef]

- Tryfonos, A., et al., (20118). ENEDI: Energy Saving in Datacenters," 2018 IEEE Global Conference on Internet of Things (GCIoT), pp. 1-5.

- Boukettaya, G., Krichen, L., A dynamic power management strategy of a grid connected hybrid generation system using wind, photovoltaic and Flywheel Energy Storage System in residential applications, Energy, Volume 71, Pages 148-159. [CrossRef]

- Poongodi, T., Ramya, S.R., Suresh, P., Balusamy, B. (2020). Application of IoT in Green Computing. In: Bhoi, A., Sherpa, K., Kalam, A., Chae, GS. (eds) Advances in Greener Energy Technologies. Green Energy and Technology. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Tan, G., Cao, J., Lu, M., & Fan, X., (2020). Modeling and Improving the Energy Performance of GPS Receivers for Location Services, IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 4512-4523, 15. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.C., & Abdelzaher, T., (2013). Social Sensing. In: Aggarwal, C. (eds) Managing and Mining Sensor Data. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Akherfi, K., Gerndt, M., & Harroud, H., (2018). Mobile cloud computing for computation offloading: Issues and challenges, Applied Computing and Informatics, Volume 14, Issue 1, Pages 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Khune, R. S., & Thangakumar, J., (2012). A cloud-based intrusion detection system for Android smartphones, International Conference on Radar, Communication and Computing (ICRCC), pp. 180-184.

- Cruz, L., & Abreu, R., (2017). Performance-Based Guidelines for Energy Efficient Mobile Applications, IEEE/ACM 4th International Conference on Mobile Software Engineering and Systems (MOBILESoft), pp. 46-57.

- DeLovato, N., Sundarnath, K., Cvijovic, L., Kota, K., & Kuravi, S., (2019). A review of heat recovery applications for solar and geothermal power plants, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 114, 109329. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A., Soliman, L. A., Raghavan, V., El-Helw, A., Gu, Z., Shen, E., Caragea, G. C., Garcia-Alvarado, C., Rahman, F., Petropoulos, M., Waas, F., Narayanan, S., Krikellas, K., & Baldwin, R., (2014). Orca: a modular query optimizer architecture for big data. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD '14). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 337–348. [CrossRef]

- Farhan, L., Hameed, RS., Ahmed, AS., Fadel, AH., Gheth, W., Alzubaidi, L., Fadhel, MA., & Al-Amidie, M., (2021) Energy Efficiency for Green Internet of Things (IoT) Networks: A Survey. Network. 1(3):279-314. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A., Chong, L. K., Ballabriga, C., & Roychoudhury, A., (2018). EnergyPatch: Repairing Resource Leaks to Improve Energy-Efficiency of Android Apps, IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 470-490. [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y., Hu, W., Yang, Y., Gao, W., & Cao, G., (2015). Energy-Efficient Computation Offloading in Cellular Networks, IEEE 23rd International Conference on Network Protocols (ICNP), pp. 145-155.

- Maute, J. M., Puebla, V. K. J., Nericua, R. T., Gerasta, O. J. L., & Hora, J. A., (2018). Design Implementation of 10T Static Random Access Memory Cell Using Stacked Transistors for Power Dissipation Reduction, IEEE 10th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology,Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM), pp. 1-6.

- Gautam, M., & Akashe, S., Transistor gating: Reduction of leakage current and power in full subtractor circuit, 3rd IEEE International Advance Computing Conference (IACC), pp. 1514-1518.

- Khosravi, L. L., Andrew, H. & Buyya, R., (2017). Dynamic VM Placement Method for Minimizing Energy and Carbon Cost in Geographically Distributed Cloud Data Centers, IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 183-196.

- Alsamhi, S.H., Ma, O., Ansari, M.S. et al. (2019). Greening internet of things for greener and smarter cities: a survey and future prospects. Telecommun Syst 72, 609–632. [CrossRef]

- Ni, J., Lin, X., & Shen, X. S., (2019). Toward Edge-Assisted Internet of Things: From Security and Efficiency Perspectives, IEEE Network, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 50-57.

- Ganatra, Y., Ruiz, J., Howarter, J. A., & Marconnet, A., (2018). Experimental investigation of Phase Change Materials for thermal management of handheld devices, International Journal of Thermal Sciences, Volume 129, Pages 358-364. [CrossRef]

- Mikulics, M., & Hardtdegen, H. H., (2020). Fully photon operated transmistor / all-optical switch based on a layered Ge1Sb2Te4 phase change medium, FlatChem, Volume 23, 100186. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z., Yang, S., Yu, Y., Vasilakos, A. V., Mccann, J. A., & Leung, K. K., (2013). gs: standards, challenges, and opportunities, IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 91-98. [CrossRef]

- Subbaraj, S., Thiyagarajan, R., & Rengaraj, M., (2021). A smart fog computing based real-time secure resource allocation and scheduling strategy using multi-objective crow search algorithm. J Ambient Intell Human Comput. [CrossRef]

- Ielmini, D. Ielmini, D., & Wong, HS. P., (2018) In-memory computing with resistive switching devices. Nat Electron 1, 333–343. [CrossRef]

- Sarood, O., Miller, P., Totoni, E., & Kalé, L. V., (2012) “Cool” Load Balancing for High Performance Computing Data Centers, IEEE Transactions on Computers, vol. 61, no. 12, pp. 1752-1764.

- Usman, J., Ismail, A.S., Chizari, H. et al., (2019). Energy-efficient Virtual Machine Allocation Technique Using Flower Pollination Algorithm in Cloud Datacenter: A Panacea to Green Computing. J Bionic Eng 16, 354–366. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Xu, W., Pan, Y., Pan, C., & Chen, M., (2018). Energy Efficient Resource Allocation in Machine-to-Machine Communications With Multiple Access and Energy Harvesting for IoT, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 229-245. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z., Lin, J., Cui, D. et al. (2020). A multi-objective trade-off framework for cloud resource scheduling based on the Deep Q-network algorithm. Cluster Comput 23, 2753–2767. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., Leung, V. C. M., Shu, L., & Ngai, E. C., (2015). Green Internet of Things for Smart World, IEEE Access, vol. 3, pp. 2151-2162. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Xu, C., Cheung, S-C., & Terragni, V., (2016). Understanding and detecting wake lock misuses for Android applications. Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering (FSE 2016). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 396–409. [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, D., Srivastava, R., Nagpal, R., & Nagpal, D., (2021). Multiclass classification of mobile applications as per energy consumption, Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, Volume 33, Issue 6, Pages 719-727. [CrossRef]

- Al-Fuqaha, A., Guizani, M., Mohammadi, M., Aledhari, M., & Ayyash, M., (2015). Internet of Things: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Protocols, and Applications, IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 2347-2376. [CrossRef]

- Rodenas-Herraiz, D., Garcia-Sanchez A-J., Garcia-Sanchez, F., (2013). Garcia-Haro, J., (2013). Current Trends in Wireless Mesh Sensor Networks: A Review of Competing Approaches. Sensors. 13(5):5958-5995. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F., Ali, I., Kousar, S. et al. (2022). The environmental impact of industrialization and foreign direct investment: empirical evidence from Asia-Pacific region. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29, 29778–29792. [CrossRef]

- Jing, SY., Ali, S., She, K., & Zhong, Y., (2013). State-of-the-art research study for green cloud computing. J Supercomput. 65(1):445–68. [CrossRef]

- Kortbeek, Vito, Abu Bakar, Cruz, S., Yildirim, K. S., Pawełczak, P., & Hester, J., (2020). BFree: Enabling Battery-free Sensor Prototyping with Python. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 4, 4, Article 135, 39 pages. [CrossRef]

- Sayadnavard, M. H., Haghighat, A. T., & Rahmani, A. M., (2022). A multi-objective approach for energy-efficient and reliable dynamic VM consolidation in cloud data centers, Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, Volume 26, 100995. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Tiwari, P. & Zymbler, M., (2019). Internet of Things is a revolutionary approach for future technology enhancement: a review. J Big Data 6, 111. [CrossRef]

- Weekly, K., Jin, M., Zou, H., Hsu, C., Soyza, C., Bayen, A., Spanos, C., (2018). Building-in-Briefcase: A Rapidly-Deployable Environmental Sensor Suite for the Smart Building. Sensors. 18(5):1381. [CrossRef]

- Giluka, M. K., Rajoria, N., Kulkarni, A. C., Sathya, V. & Tamma, B. R., (2014). Class based dynamic priority scheduling for uplink to support M2M communications in LTE, IEEE World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), pp. 313-317.

- Tamkittikhun, N., Hussain, A., Kraemer, F.A., (2017). Energy Consumption Estimation for Energy-Aware, Adaptive Sensing Applications. In: Bouzefrane, S., Banerjee, S., Sailhan, F., Boumerdassi, S., Renault, E. (eds) Mobile, Secure, and Programmable Networking. MSPN. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 10566. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Maray, M., & Shuja, J., (2022). Computation Offloading in Mobile Cloud Computing and Mobile Edge Computing: Survey, Taxonomy, and Open Issues, Mobile Information Systems, vol. 2022, Article ID 1121822, 17 pages. [CrossRef]

- Gavurova, B., Rigelsky, M., & Ivankova, V. (2021). Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Health in the Countries of the European Union. Front Public Health. 9: 756652. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Mao, S., & Leung, V. C. M., (2015). EMC: Emotion-aware mobile cloud computing in 5G, IEEE Network, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 32-38.

- Madni, S. H. H., Abd Latiff, M. S., Coulibaly, Y., & Abdulhamid, S. M., (2016). Resource scheduling for infrastructure as a service (IaaS) in cloud computing: Challenges and opportunities, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 68, Pages 173-200. [CrossRef]

- Shuja, J., Ahmad, R.W., Gani, A. et al., (2017). Greening emerging IT technologies: techniques and practices. J Internet Serv Appl 8, 9. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D., Rao, J., Jiang, C., & Zhou, X., Resource and Deadline-Aware Job Scheduling in Dynamic Hadoop Clusters, IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium, pp. 956-965.

- Vijayaraghavan, T., et al., (2017). Design and Analysis of an APU for Exascale Computing, IEEE International Symposium on High Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA), pp. 85-96.

- Vahedi, E., Ward, R. K., & Blake, I. F., (2014) Performance Analysis of RFID Protocols: CDMA Versus the Standard EPC Gen-2, IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1250-1261. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M., Haque, M.E., & Arif, M.T., (2022). Kalman filtering techniques for the online model parameters and state of charge estimation of the Li-ion batteries: A comparative analysis, Journal of Energy Storage, Volume 51, 104174. [CrossRef]

- Guliani, A., & Swift M. M., (2019). Per-Application Power Delivery. Proceedings of the Fourteenth EuroSys Conference (EuroSys '19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 5, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, M. H., Rahmani, A. M., & Sahafi, A., (2020). A survey study on virtual machine migration and server consolidation techniques in DVFS-enabled cloud datacenter: Taxonomy and challenges, Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, Volume 32, Issue 3, Pages 267-286. [CrossRef]

- Samriya, J. K., & Kumar, N., (2020). An optimal SLA based task scheduling aid of hybrid fuzzy TOPSIS-PSO algorithm in cloud environment, Materials Today: Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Angrish, A., Starly, B., Lee, Y-S., & Cohen, P. H., (2017). A flexible data schema and system architecture for the virtualization of manufacturing machines (VMM), Journal of Manufacturing Systems, Volume 45, Pages 236-247. [CrossRef]

- Belkhir, L., & Elmeligi, A., (2018). Assessing ICT global emissions footprint: Trends to 2040 & recommendations, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 177, Pages 448-463. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Sun, H., Li, C., Li, T., Xin, J., & Zheng, N., (2021). Exploring Highly Dependable and Efficient Datacenter Power System Using Hybrid and Hierarchical Energy Buffers, IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 412-426. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Gordon, M. S., Dick, R. P., Mao, Z. M., Dinda, P., & Yang, L., (2012). ADEL: an automatic detector of energy leaks for smartphone applications. Proceedings of the eighth IEEE/ACM/IFIP international conference on Hardware/software codesign and system synthesis (CODES+ISSS '12). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 363–372. [CrossRef]

- Torous, J., & Roberts, LW., (2017). Needed Innovation in Digital Health and Smartphone Applications for Mental Health: Transparency and Trust. JAMA Psychiatry. 74 (5):437–438. [CrossRef]

- Madhu, J. G. P. & Dhiman, G., (2017). An architecture for energy-efficient hybrid full adder and its CMOS implementation," 2017 Conference on Information and Communication Technology (CICT), pp. 1-5.

- Lakshmi, S., Raj, C. M., & Krishnadas, D., (2018). Optimization of Hybrid CMOS Designs Using a New Energy Efficient 1 Bit Hybrid Full Adder, 3rd International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), pp. 905-908.

- Yuan, J., Wang, Y., Chen, H., Jin, H., & Liu, H., (2021). Eunomia: Efficiently Eliminating Abnormal Results in Distributed Stream Join Systems, IEEE/ACM 29th International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQOS), pp. 1-11.

- Avvari, G.V., Pattipati, B., Balasingam, B., Pattipati, K.R., & Bar-Shalom, Y., (2015). [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, A., Masdari, M., & Gharehchopogh, F.S., (2021). Energy and Cost-Aware Workflow Scheduling in Cloud Computing Data Centers Using a Multi-objective Optimization Algorithm. J Netw Syst Manage 29, 31. [CrossRef]

- Koronen, C., Åhman, M. & Nilsson, L.J., (2020). Data centres in future European energy systems—energy efficiency, integration and policy. Energy Efficiency 13, 129–144. [CrossRef]

- Freitag, C., Berners-Lee, M., Widdicks, K., Knowles, B., Blair, G. S., Friday, A., (2021). The real climate and transformative impact of ICT: A critique of estimates, trends, and regulations, Patterns, Volume 2, Issue 9, 100340. [CrossRef]

- Tarplee, K. M., Friese, R., Maciejewski, A. A., Siegel, H. J., & Chong, E. K. P., (2016). Energy and Makespan Tradeoffs in Heterogeneous Computing Systems using Efficient Linear Programming Techniques, IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 1633-1646. [CrossRef]

- Muzamane, HA., & Liu, H-C., (2021). Experimental Results and Performance Analysis of a 1 × 2 × 1 UHF MIMO Passive RFID System. Sensors. 21(18):6308. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H., Ghouchani, B. E. (2021), Virtual machine placement mechanisms in the cloud environments: a systematic review, Kybernetes, Vol. 50 No. 2, pp. 333-368. [CrossRef]

- Barke, A., Bley, T., Thies, C., Weckenborg, C., & Spengler, T.S., (2022). Are Sustainable Aviation Fuels a Viable Option for Decarbonizing Air Transport in Europe? An Environmental and Economic Sustainability Assessment. Appl. Sci., 12, 597. [CrossRef]

- Koot, M., & Wijnhoven, F., (2021). Usage impact on data center electricity needs: A system dynamic forecasting model, Applied Energy, Volume 291, 116798. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A., Singh, G. K., & Pant, V., (2021). Protection of AC microgrid integrated with renewable energy sources – A research review and future trends, Electric Power Systems Research, Volume 193, 107036. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, Y., Hammad, H., Waraga, O. A., & Talib, M. A., Energy Management Systems and Smart Phones: A Systematic Literature Survey, International Conference on Communications, Computing, Cybersecurity, and Informatics (CCCI), pp. 1-7.

- Begum, R., Werner, D., Hempstead, M., Prasad, G., & Challen, G., Energy-Performance Trade-offs on Energy-Constrained Devices with Multi-component DVFS, IEEE International Symposium on Workload Characterization, pp. 34-43.

- Bressler, R.D., (2021). The mortality cost of carbon. Nat Commun 12, 4467. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A., Rana, S., & Matahai, K.J., (2016). A Critical Analysis of Energy Efficient Virtual Machine Placement Techniques and its Optimization in a Cloud Computing Environment, Procedia Computer Science, Volume 78, Pages 132-138. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R. W., et al., (2019). Enhancement and Assessment of a Code-Analysis-Based Energy Estimation Framework, IEEE Systems Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1052-1059. [CrossRef]

- Lannelongue, L., Grealey, J., & Inouye, M., (2021). Green Algorithms: Quantifying the Carbon Footprint of Computation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 8 (12):2100707. [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, W., & Chinedu, P. U., (2020). Green Computing: A Machinery for Sustainable Development in the Post-Covid Era. In (Ed.), Green Computing Technologies and Computing Industry in 2021. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., (2018). Multi-Objective Decision-Making for Mobile Cloud Offloading: A Survey, IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 3962-3976. [CrossRef]

- Roelich, K., Knoeri, C., Steinberger, J. K., Varga, L., Blythe, P. T., Butler, D., Gupta, R., Harrison, G. P., Martin, C., & Purnell, P., Towards resource-efficient and service-oriented integrated infrastructure operation, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Volume 92, Pages 40-52. [CrossRef]

- Bharany, S., Sharma, S., Khalaf, O.I., Abdulsahib, G.M., Al Humaimeedy, A.S., Aldhyani, T.H.H., Maashi, M., & Alkahtani, H., (2022). A Systematic Survey on Energy-Efficient Techniques in Sustainable Cloud Computing. Sustainability, 14, 6256. [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A. I., (2022). Household's awareness and participation in sustainable electronic waste management practices in Saudi Arabia, Ain Shams Engineering Journal, Volume 13, Issue 4, 101729. [CrossRef]

- Almobaideen, W., Qatawneh, M., & AbuAlghanam, O., (2019). Virtual Node Schedule for Supporting QoS in Wireless Sensor Network, IEEE Jordan International Joint Conference on Electrical Engineering and Information Technology (JEEIT), pp. 281-285.

- Khan, A. A., & Zakarya, M., (2021). Energy, performance and cost efficient cloud datacentres: A survey, Computer Science Review, Volume 40, 100390. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C., Goswami, P., & Bai, G., (2020). A literature review of current technologies on health data integration for patient-centered health management. Health Informatics Journal. 1926-1951. [CrossRef]

- Benis, A., Tamburis, O., Chronaki, C., & Moen, A., (2021). One Digital Health: A Unified Framework for Future Health EcosystemsJ Med Internet Res; 23 (2):e22189. e22189: 23 (2). [CrossRef]

- Keeler, L. W., & Bernstein, M. J., (2021). The future of aging in smart environments: Four scenarios of the United States in 2050, Futures, Volume 133, 102830. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Manogaran, G., & Muthu, B., (2021). IoT enabled integrated system for green energy into smart cities, Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, Volume 46, 101208. [CrossRef]

- Sarrafan, K., Muttaqi, K. M., & Sutanto, D., (2020). Real-Time State-of-Charge Tracking Embedded in the Advanced Driver Assistance System of Electric Vehicles, IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 497-507. [CrossRef]

- Calza, F., Parmentola, A., & Tutore, I., (2020). Big data and natural environment. How does different data support different green strategies? Sustainable Futures, Volume 2, 100029. [CrossRef]

- Toosi, A. N., Qu, C., Assunção, M. D., & Buyya, R., (2017). Renewable-aware geographical load balancing of web applications for sustainable data centers, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 83, Pages 155-168. [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, S., Rizou, S., & Spinellis, D., (2020). Software Development Lifecycle for Energy Efficiency: Techniques and Tools. ACM Comput. Surv. 52, 4, Article 81, 33 pages. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S., Köhler, A., Liu, R., Stobbe, L., Proske, M., & Schischke, K., (2016). Paradigm shift in Green IT - extending the life-times of computers in the public authorities in Germany, Electronics Goes Green 2016+ (EGG), pp. 1-7.

- Qureshi, K. N., Hussain, R., & Jeon, G., (2020). A Distributed Software Defined Networking Model to Improve the Scalability and Quality of Services for Flexible Green Energy Internet for Smart Grid Systems, Computers & Electrical Engineering, Volume 84, 106634. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z., Zhou, X., Hu, H., Wang, Z., & Wen, Y., (2022). Toward a Systematic Survey for Carbon Neutral Data Centers," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 895-936. [CrossRef]

- Diniz, E. H., Yamaguchi, J. A., Santos, T. R., Carvalho, A. P., Alégo, A. S., & Carvalho, M., Greening inventories: Blockchain to improve the GHG Protocol Program in scope 2, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 291, 125900. [CrossRef]

- Lumbreras, M., Diarce, G., Martin-Escudero, K., Campos-Celador, A., Larrinaga, P., (2022). Design of district heating networks in built environments using GIS: A case study in Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 349, 131491. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R. W., Gani, A., Hamid, S. H., Xia, F., & Shiraz, M., (2015). A Review on mobile application energy profiling: Taxonomy, state-of-the-art, and open research issues, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 58, Pages 42-59. [CrossRef]

- Dauvergne, P., (2022). Is artificial intelligence greening global supply chains? Exposing the political economy of environmental costs, Review of International Political Economy, 29:3, 696-718. [CrossRef]

- Tso, F., Jouet, S., Pezaros, & D. P., (2016). Network and server resource management strategies for data centre infrastructures: A survey, Computer Networks, Volume 106, Pages 209-225. [CrossRef]

- Biran, O., Corradi, A., Fanelli, M., Foschini, L., Nus, A., Raz, D., Silvera, E., (2012). A stable network-aware VM placement for cloud systems. Proceedings of IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGRID ’12), pp. 498-506.

- Mann, V., Gupta, A., Dutta, P., Vishnoi, A., Bhattacharya, P., Poddar, R., Iyer, A., (2012). Remedy: network-aware steady state VM management for data centers Proceedings of IFIP TC 6 Networking Conference, LNCS, vol. 7289, pp. 190-204.

- Gutierrez-Estevez, D.M., Luo, M., (2015). Multi-resource schedulable unit for adaptive application-driven unified resource management in data centers. Proceedings of 2015 International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC), pp. 261-268.

- Manvi, S. S., & Shyam, G. K., (2014). Resource management for Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) in cloud computing: A survey, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 41, Pages 424-440. [CrossRef]

- Tso, F.P., Oikonomou, K., Kavvadia, E., & Pezaros, D.P. (2014). Scalable traffic-aware virtual machine management for cloud data centers. Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), IEEE, pp. 238-247.

- Shuja, J., Bilal, K., Madani, SA., Othman, M., Ranjan, R., Balaji, P., & Khan, SU. (2016). Survey of techniques and architectures for designing energy-efficient data centers. IEEE Syst J.10 (2):507–19. [CrossRef]

- Koot, M., & Wijnhoven, F., (2021). Usage impact on data center electricity needs: A system dynamic forecasting model, Applied Energy, Volume 291, 116798. [CrossRef]

- Wierman, A., Liu, Z., Liu, I. & Mohsenian-Rad, H., (2014). Opportunities and challenges for data center demand response, International Green Computing Conference, pp. 1-10.

- Moazamigoodarzi, H., Pal, S., Down, D., Esmalifalak, M., & Puri, I. K., (2020). Performance of a rack mountable cooling unit in an IT server enclosure, Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, Volume 17, 100395. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A., Jindal, A., Hu, Y. C., & Midkiff, S. P., (2012). What is keeping my phone awake? Characterizing and detecting no-sleep energy bugs in smartphone apps. Proceedings of the 10th international conference on Mobile systems, applications, and services (MobiSys '12). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 267–280. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S. A. L., Cunha, D. C., Silva-Filho, A. G., (2019). Autonomous power management in mobile devices using dynamic frequency scaling and reinforcement learning for energy minimization, Microprocessors and Microsystems, Volume 64, Pages 205-220. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, K., Jones, GF., &Fleischer, AS. (2014). A review of data center cooling technology, operating conditions and the corresponding low-grade waste heat recovery opportunities. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 31: 622–38.

- Shuja, J., Gani, A., Shamshirband, S., Ahmad, R. W., & Bilal, K., (2016). Susthniques and technologies, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 62, Pages 195-214. [CrossRef]

- Tiwary, M., Puthal, D., Sahoo, K. S., Sahoo, B., & Yang, L. T., (2018). Response time optimization for cloudlets in Mobile Edge Computing, Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, Volume 119, Pages 81-91. [CrossRef]

- Jin, C., Bai, X., Yang, C., Mao, W., & Xu, X., (2020). A review of power consumption models of servers in data centers, Applied Energy, Volume 265, 114806. [CrossRef]

- Mosaad, M. I., Elkalashy, N. I., & Ashmawy, M. G., (2018). Integrating adaptive control of renewable distributed Switched Reluctance Generation and feeder protection coordination, Electric Power Systems Research, Volume 154, Pages 452-462. [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, D., et al., (2014). A 3 GHz Dual Core Processor ARM Cortex TM -A9 in 28 nm UTBB FD-SOI CMOS With Ultra-Wide Voltage Range and Energy Efficiency Optimization, IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 812-826. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W., Wu, W., Wang, H., Wang, J. Z., & Hsu, C., (2018). Experimental and quantitative analysis of server power model for cloud data centers, Future Generation Computer Systems, Volume 86, Pages 940-950. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P., Hu, Z., Liu, D., Yan, G., & Qu, X., (2013). Virtual machine power measuring technique with bounded error in cloud environments, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 36, Issue 2, Pages 818-828. [CrossRef]

- Arroba, P., Risco-Martín, J. L., Zapater, M., Moya, J. M., Ayala, J. L., Olcoz, K., (2014). Server Power Modeling for Run-time Energy Optimization of Cloud Computing Facilities, Energy Procedia, Volume 62, Pages 401-410. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C. & Naik, K. (2021). Smartphone processor architecture, operations, and functions: current state-of-the-art and future outlook: energy performance trade-off. J Supercomput 77, 1377–1454. [CrossRef]

- Strazzabosco, A., Gruenhagen, J.H., & Cox, S., (2022). A review of renewable energy practices in the Australian mining industry, Renewable Energy, Volume 187, Pages 135-143. [CrossRef]