1. Introduction

Cement, the primary binding material in concrete, consumes about 10-15% of industrial energy and emits approximately 5-9% of world’s anthropogenic

during its production [

1,

2,

3]. Approximately 1 ton of

is produced during the production of 1 ton of cement, which is environmentally taxing [

1,

4,

5,

6]. Furthermore, concrete is a widely used construction material due to its economic and durability benefits, and its demand is increasing every year due to its need for infrastructure construction [

2,

4,

7]. Around 4.1 billion metric tons of cement were produced in the world in 2022, where United States alone accounted for 93 million metric tons [

8]. The production of cement is expected to increase to 5.0 billion metric tons by 2030 worldwide [

7]. On the other hand, in 2018, 12.25 million tons of municipal glass waste (WG) were generated in the United States. However, according to EPA, only 25% of them were recycled and the remaining were either combusted (13.4%) or land-filled (61.6%) [

9]. Additionally, the glass takes a very long time (approximately 4000 years) to degrade naturally, which is another concern for the sustainable environment.

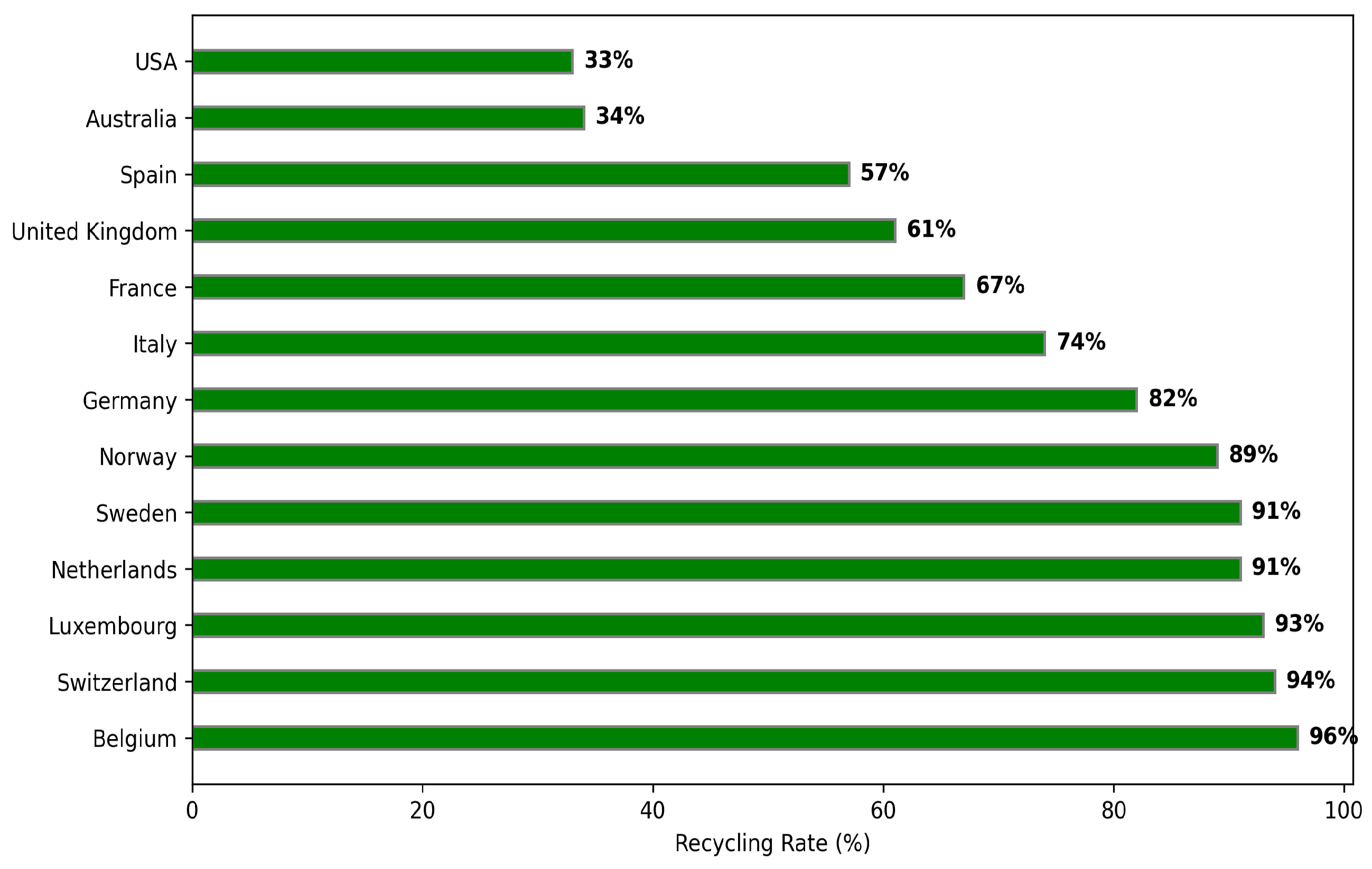

Figure 1 shows the recycling rates for discarded glass in different nations. Notably, of the countries examined, the USA and Australia have the lowest recycling rates, while European countries have higher recycling rates.

The use of cement and the effect of global warming can be reduced to a certain extent by incorporating supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) such as Fly Ash (FA), Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBFS), Ground Glass Powder (GGP), Silica Fume (SF), natural pozzolans, Rice Husk Ash (RHA) etc. as a partial replacement of cement [

4,

7]. The availability of the most commonly used SCM, fly ash (FA), is sharply decreased due to the rapid decommissioning of coal-powered plants in the USA in recent years [

1,

10]. Around 25% of coal-based power plants are shut down while many are converting to cheaper and cleaner alternatives such as renewable and natural gas, leading to the shortage of FA [

1,

4]. The intermittent supply of FA, comparatively high cost of slag, and the sustainability challenges due to the allocation of colossal landfill sites to waste glass leads the concrete industry in the USA to explore for the other alternatives of SCMs [

4]. The artificial pozzolans like fine GGP and natural pozzolans like pumice, perlite, volcanic ash, etc. contains amorphous alumino-silicate to form C-S-H gel during the reaction with calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)

2) in the presence of water are potential alternatives to FA [

11]. Natural pozzolans have the benefits of improving durability and sustainability in concrete; however, they do have few drawbacks, such as variability in chemical and physical properties, limited availability and supply, slow pozzolanic activity, possible contamination and processing challenges, and transportation costs. Glass has lower variation of material chemical composition, greater purity, and lower water demand when compared FA and traditional SCMs [

12].

Figure 1.

Recycling rates of waste glass in different countries.[

13]

Figure 1.

Recycling rates of waste glass in different countries.[

13]

Studies [

1,

4,

7,

12,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] have demonstrated that inert waste glass when crushed and milled to very fine powder level of 300

m particle size shows behavior of pozzolanic material enhancing the mechanical properties of concrete due to its high silicon content. Furthermore, studies [

15,

34] have concluded that GP finer than 100

m can exhibit better pozzolanic reactivity than FA after 90 days of curing at low cement replacement percentage. This could lower approximately ½ pound of

emission for every pound of glass used[

1]. Additionally, [

35] investigated life cycle assessment on utilization of GGP on a case study of bridge retrofit. They found that using 20% GGP instead of cement in the production of concrete decreased greenhouse gas emissions by 1.23 kg

-equivalent and energy consumption by 0.008 GJ per kilogram of GGP incorporated. Thus, waste glass has high potential to tackle the problems faced by concrete industry - due to a widespread sourcing unlike natural pozzolans and the sharp decrease of FA production - to be used as a SCMs in the USA.[

1,

36].

This study aims to explore recent studies on the application of GGP in concrete production and its benefits as a sustainable alternative to reduce carbon footprint and promote a circular economy. This study emphasizes the potential of GGP as an efficient SCM by focusing on the mechanical and fresh qualities of GGP-incorporated concrete, including workability, density, setting time, compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, and punching strength. The pressing need to lessen the environmental effects of cement production — a significant source of carbon emissions worldwide — is what spurred this research. This research highlights the importance of GGP in promoting sustainable building practices in addition to analyzing its technical feasibility as a pozzolanic material.

2. Literature Review

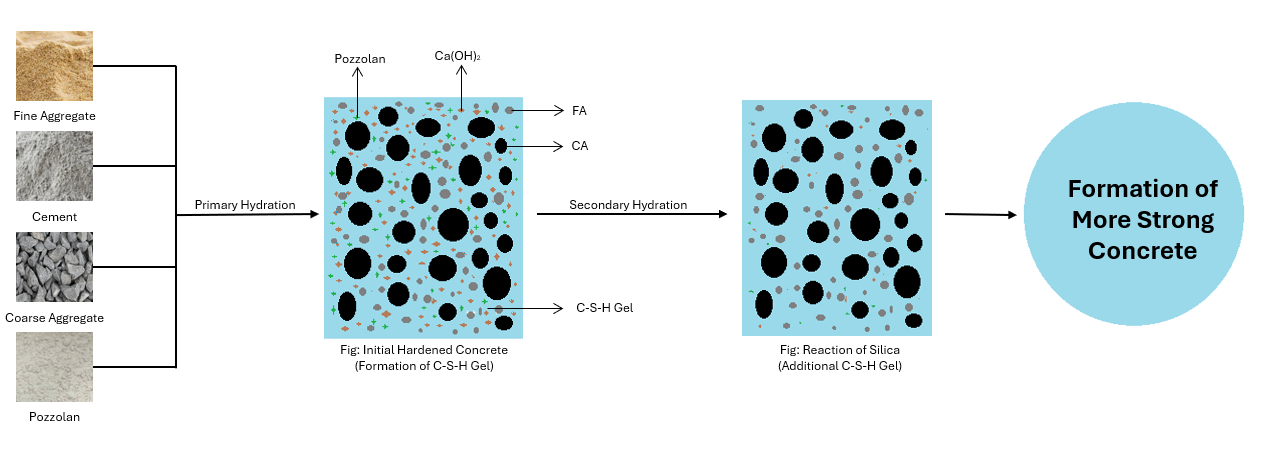

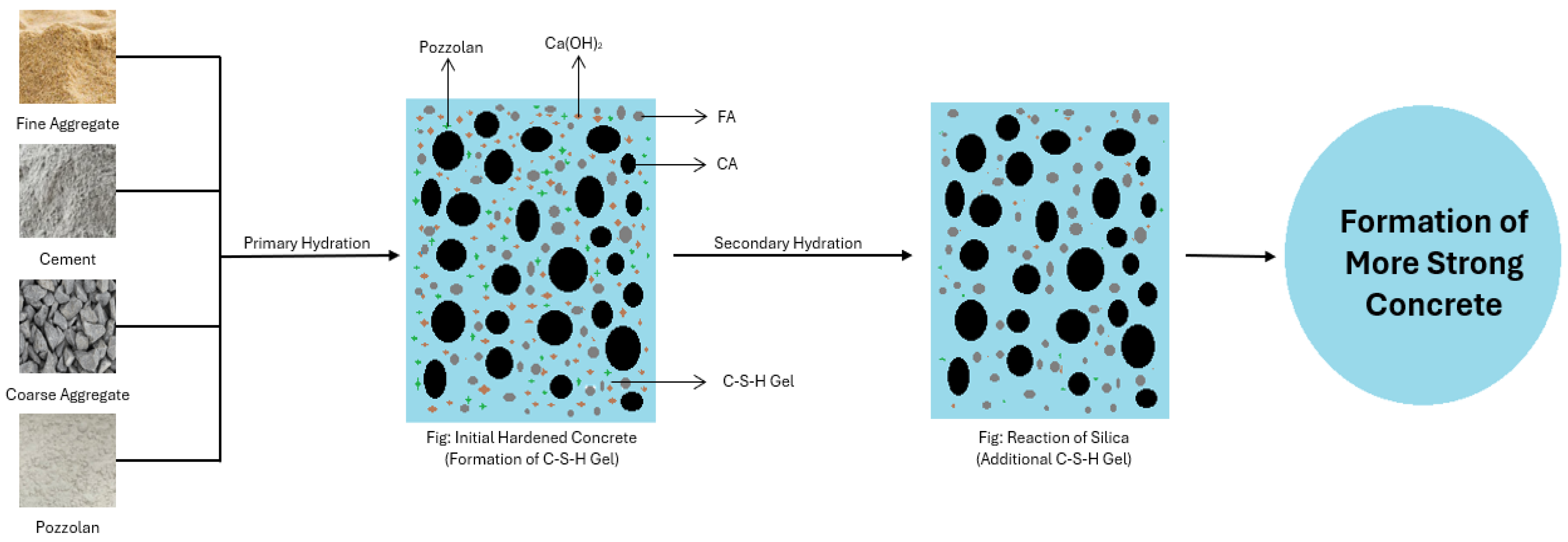

2.1. Pozzolans

“A material comprised of silica or silica along with alumina, which inherently lacks significant cementitious properties but can chemically react with calcium hydroxide ((Ca(OH)

2)) under typical temperatures when finely divided and in the presence of moisture, resulting in the formation of compounds (C-S-H gel) with cementitious characteristics is called Pozzolan” according to ASTM-C125 [

37]. SCMs are frequently employed in concrete mixtures as partial cement replacements; the quantity of SCMs used varies based on the desired concrete qualities as shown in

Figure 2. The compounds in cement; tricalcium silicate (3 CaO.

(

S)), dicalcium silicate (2 CaO.

(

S)) reacts with water (hydration of cement) to form 3 CaO.2

.3

O (C-S-H) gel and Ca(OH)

2 as a byproduct. This calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H gel) is highly adhesive in nature with very low solubility that binds the aggregates and provides strength to the concrete. On the other hand, the byproduct Ca(OH)

2 is soluble in water and gets leeched out of the concrete. This makes concrete more porous with lower strength. The substitution of the portion of cement with SCMs to react with byproduct Ca(OH)

2 to form an additional C-S-H gel contributes to a decrease in the total amount of cement, which benefits the environment by lowering carbon emissions from cement manufacture. SCMs can also improve the concrete’s long-term durability by decreasing permeability, strengthening resistance to chemical deterioration, and boosting resistance to sulfate assault. The chemical reaction involved in the pozzolanic reaction is illustrated below:

The methods required for selecting materials as pozzolans are largely determined by the amorphous contents of minerals found in raw materials and/or the industrial processes that produce by-products with pozzolanic reactivity [

38]. The pozzolans are divided into three categories based on their production methods: (i) Natural Pozzolan : The materials such as volcanic ash, pumice, and certain types of clay minerals that are produced through the grinding of raw natural materials into fine particles, without the need for calcination or heat treatment to alter their chemical and/or structural properties to enhance pozzolanic reactivity [

39]. (ii) Processed pozzolans : materials made from clays and shales. These are produced by grinding raw natural materials into fine particles, without requiring calcination or heat treatment to modify their chemical and/or structural properties for improving pozzolanic reactivity. when calcined at high temperatures, become pozzolanic and contain a significant proportion of crystalline silica and alumina in their raw form. Fly ash (FA), rice husk ash (RHA), and silica fume (SF) are considered processed pozzolans, as they are industrial by-products resulting from the combustion of coal, rice husks, and silica, respectively. (iii) Manufactured Pozzolans: the materials such as Ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) and GGP that acquire pozzolanic characteristics after grinding the refined substances into fine powder [

38].

2.2. Chemical Composition of Pozzolans

The origin of the raw materials or refined materials used in the production process affects the elemental and mineral composition of pozzolans [

38]. Silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), iron (Fe), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), potassium (K), and sodium (Na) are among the elements that make up this composition. When utilized in cementitious systems, the pozzolanic activity and performance are directly impacted by the amounts of these components, which differ based on the materials’ source. The Si and Al content dominates in all pozzolans except for silica fume, which contains a very high Si amount.

Table 1 displays the elemental composition, which is typically represented by the oxides

,

,

, CaO, MgO,

O, and

O.

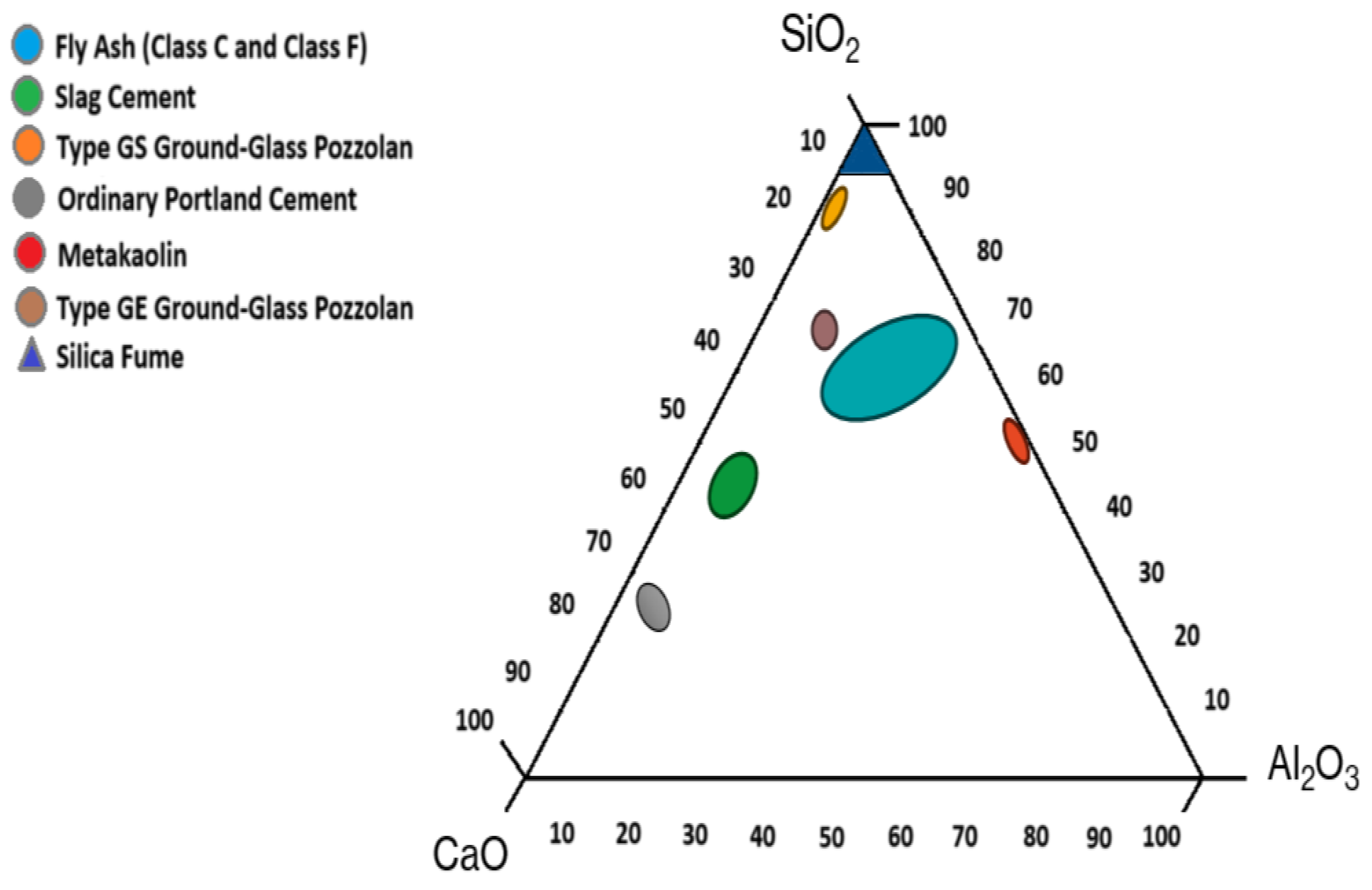

An efficient analytical technique for assessing and contrasting the pozzolanic reactivity of different processed and produced pozzolans is a ternary diagram, illustrated in

Figure 3, normalized to the combined proportions of

,

, and CaO. One of the most reactive pozzolanic materials is silica fume (SF), which is mostly made of

. Its ultra-fine particle size and unusually high silica content enable a quick reaction with Ca(OH)

2that produces more calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, improving the durability and performance of concrete [

44,

45].

GGP has a lower

concentration than SF [

46], it nevertheless outperforms other widely used pozzolans in this area. GGP’s pozzolanic reactivity may surpass that of pozzolans such as fly ash, metakaolin, and slag due to its comparatively high silica concentration. More reactive silica is available because to the higher

content in GGP, which is essential for the hydration process’s production of more calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel. When GGP is utilized as an additional cementitious material, its reactivity may result in better mechanical properties in cementitious systems. Furthermore, the performance of GGP is significantly influenced by other parameters, including particle size, specific surface area, curing temperatures, and the total chemical composition, even if it’s comparatively high

concentration [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. The pozzolanic reaction’s kinetics and the material’s capacity to interact with Ca(OH)

2 during hydration are controlled by these characteristics [

52]. Glass’s reactivity and usefulness as an additional cementitious material varies greatly depending on the type (such as soda-lime, borosilicate, or tempered glass) [

53]. For consistent performance, the underlying material must be thoroughly characterized. The sections that follows offers more information on the characteristics and advantages of GGP in improving the strength and durability of concrete.

Figure 3.

Ternary plot for different materials (normalized to the sum of

,

, and CaO). (Source [

54] )

Figure 3.

Ternary plot for different materials (normalized to the sum of

,

, and CaO). (Source [

54] )

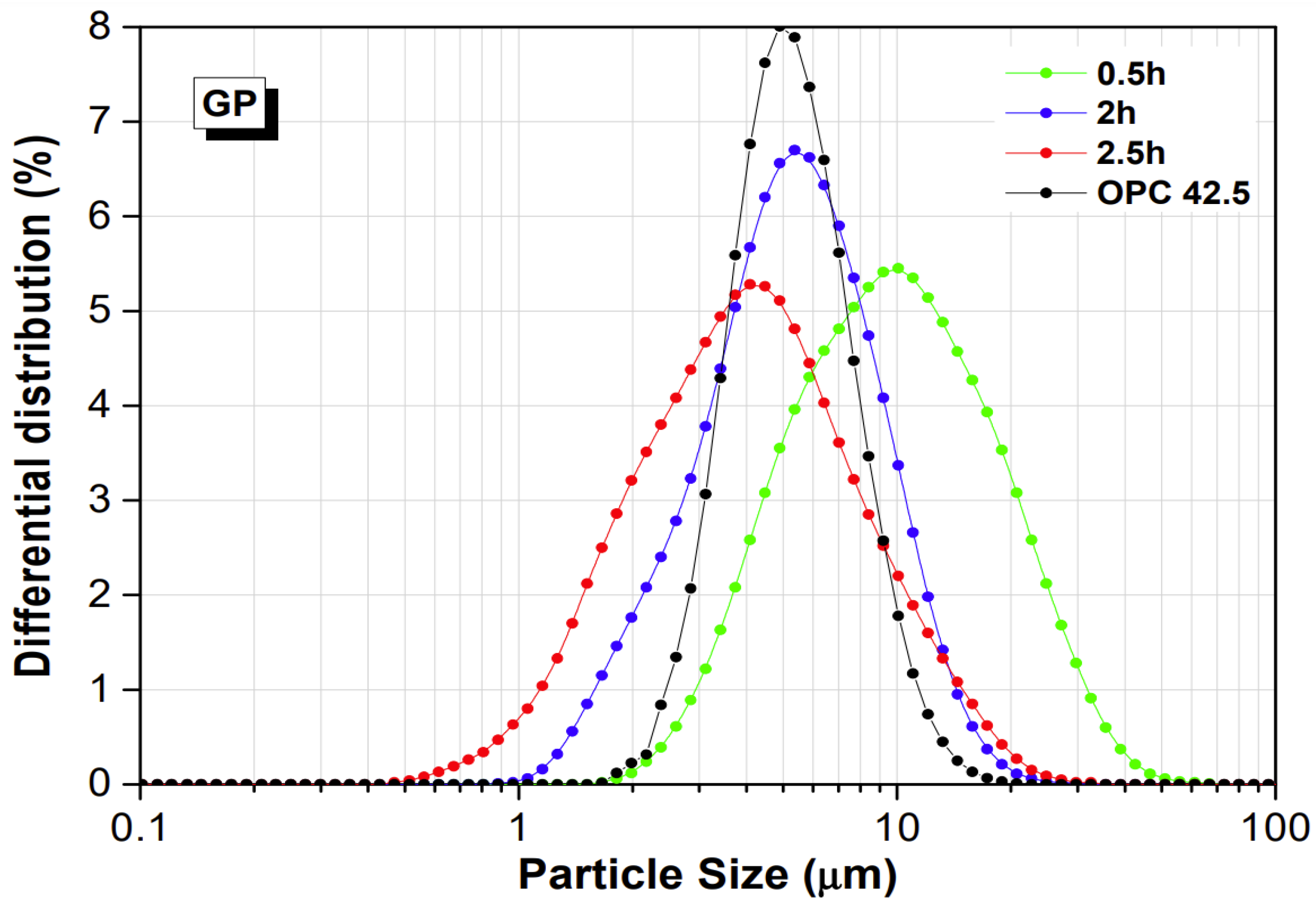

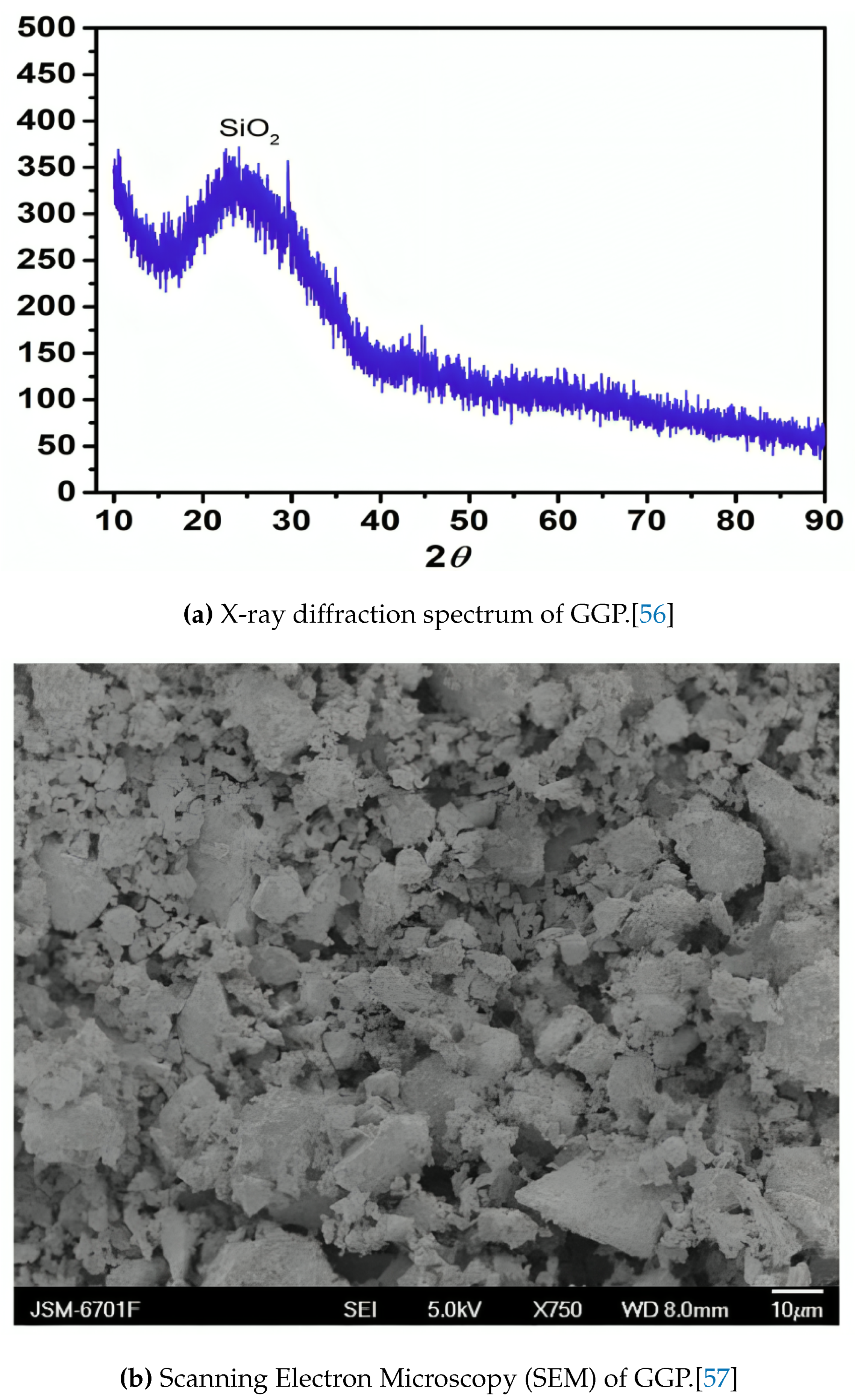

2.3. Ground Glass Pozzolan (GGP)

GGP, obtained from recycled waste glass can be categorized based on glass types, glass colors, and application. This classification provides important information about GGP characteristics and their uses in concrete mix design optimization. Lead glass, soda-lime glass, borosilicate glass, aluminosilicate glass, barium glass, electrical glass, E glass, and other substances are among the many different forms of glass. These glasses can be crushed and ground to a finer powder size using a ball mill to partially replace cement in concrete. The average ground time and particle size distribution is shown in

Figure 4. Additionally, recycled waste glass has an amorphous structure in X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns that increases as depicted in

Figure 5(a). This amorphous silica has a higher number of reactive sites than crystalline silica due to its less ordered structure, which speeds up hydration in the early phases of cementitious reactions [

1]. The micro morphology of GGP as illustrated in

Figure 5(b) shows a smooth surface and a dense microstructure that can be used for self-compacting concrete due to low water absorption capacity [

55]. The upcoming section describes the detailed chemical composition of glass based on its type and color.

2.3.1. Types of Glass

Various types of glass include soda-lime glass, borosilicate glass, lead glass, aluminosilicate glass, and E-glass, among others. The chemical composition of different types of glass is shown in

Table 2. Soda-lime glass is the most widely used of them, especially in windows, jars, and bottles used in homes. USA, approximately produces 11.5 tons of post-consumer waste glass, where 90% glasses are soda-lime [

58]. Based on its intended function, soda-lime glass is further divided into two primary types: plate glass, which is frequently used in windows and flat panels, and container glass, which is used for objects like bottles and jars[

4,

58]. Plate glass is produced by floating on a molten tin. It is available in both clear or tinted color varieties and is utilized as a glazing material, providing transparency in automobiles and buildings. Similarly, Container glass is produced through a molding process utilizing air pressure and is available in a range of colors, including clear, green, blue, and amber. They are usually used for packaging since they are highly durable, chemically resistive and ability to preserve the integrity of stored products[

54]. E-glass is renowned for its high electrical resistance and mechanical properties with low-alkali content. This glass produced through an extrusion process and is primarily used as a reinforcement in fiber-reinforced polymers [

59,

60].

While other glass types, may possess higher silica content suitable for pozzolanic reactions. The uniformity and stability of soda-lime glass in a variety of applications are facilitated by the very minimal variance in its silica concentration [

61]. Because of this property, soda-lime glass is a good pozzolan to be used as a SCM in concrete industry. Furthermore, as indicated in

Table 4, ASTM [

62] also specifies the minimum and maximum ranges for component elements in the chemical composition of both soda-lime and E glasses. “Type GS" and “Type GE" are shorthands for ground soda-lime glass and ground E-glass, respectively.

Table 2.

Composition of different types of glass. Source[

13,

54]

Table 2.

Composition of different types of glass. Source[

13,

54]

| Glass Type |

(%) |

O+O (%) |

CaO (%) |

(%) |

MgO (%) |

(%) |

| Electric glass |

52.0 – 56.0 |

0.0 – 2.0 |

16.0 – 25.0 |

12.0 – 16.0 |

– |

– |

| Borosilicate glass |

70.0 – 80.0 |

4.0 – 8.0 |

– |

7.0 |

– |

11.0 – 15.0 |

| Lead glass |

54.0 – 65.0 |

13.0 – 15.0 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| Soda-lime glass |

71.0 – 75.0 |

12.0 – 16.0 |

10.0 – 15.0 |

– |

0.1 – 4.0 |

– |

| E-glass |

59.9 – 61.3 |

0.77 – 0.81 |

21.4 – 21.9 |

12.5 – 12.64 |

2.69 |

– |

| Barium glass |

36.0 – 35.0 |

7.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 – 4.0 |

9.0 |

10.0 |

| Aluminosilicate glasses |

57.0 – 64.5 |

0.5 – 1 |

8.0 – 10.0 |

17.0 – 24.5 |

7.0 – 10.5 |

5 |

Table 3.

Chemical composition requirements for glass Types GS and GE. Source[

62]

Table 3.

Chemical composition requirements for glass Types GS and GE. Source[

62]

| Component |

Type GS |

Type GE |

| Silicon dioxide (), min (%) |

60.0 |

55.0 |

| Aluminum oxide (), max (%) |

5.0 |

15.0 |

| Calcium oxide (CaO), max (%) |

15.0 |

25.0 |

| Iron oxide (), max (%) |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| Sulfur trioxide (), max (%) |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| Total equivalent alkalies, , max (%) |

15.0 |

4.0 |

| Moisture content, max (%) |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| Loss on ignition, max (%) |

0.5 |

0.5 |

Table 4.

Chemical composition requirements for glass Types GS and GE. Source [

62]

Table 4.

Chemical composition requirements for glass Types GS and GE. Source [

62]

| Type |

|

|

CaO |

|

|

|

Moisture |

LOI |

| GS |

≥60.0 |

≤5.0 |

≤15.0 |

≤1.0 |

≤1.0 |

≤15.0 |

≤0.5 |

≤0.5 |

| GE |

≥55.0 |

≤15.0 |

≤25.0 |

≤1.0 |

≤1.0 |

≤4.0 |

≤0.5 |

≤0.5 |

2.3.2. Glass Color

Glass can be divided into clear glass, amber glass, brown glass, green glass, or white glass based on color composition [

13,

55]. Different chemical compositions as shown in

Table 5 can be observed from different colors of glass for the same type of glass. In recycled glass, the acceptable limits for color contamination are as follows: 4%-6% for clear glass, 5%-15% for amber glass, and 5%-30% for green glass alone [

55]. To effectively separate and sort various colors for additional processing, mixed-color glass is separated and sorted at recycling plants utilizing optical sorting technology. Since around one-third of the mixed-color glass contains particles smaller than 3/8 inch (9.51 mm), optical color separation is not cost-effective because of the lower sorting efficiency and greater processing expenses for finer particles [

58]. Additionally, chemical incompatibility and temperature fluctuations that can impact the quality and structural integrity of recovered glass when melted and reprocessed make it difficult to reuse mixed-color glass. A small quantity of 5 grams of non-recyclable glass is adequate to contaminate an entire ton of recyclable glass [

58]. However, color separation of the glass is not required when used as a pozzolan. Because color has no effect on the glass’s pozzolanic qualities; such as its capacity to react with Ca(OH)

2, mixed-color glass can be used without separation [

54]. Through the reduction of carbon emissions, the partial substitution of glass as a pozzolan for cement would make a substantial contribution to sustainable construction methods. By reducing the need for cement production — which is energy-intensive and produces significant

emissions—this substitution could be a more ecologically responsible method of building.

3. Fresh Concrete Properties

3.1. Slump

The ease with which fresh concrete may be mixed, transported, and laid without segregation or excessive bleeding is known as concrete workability, and it is commonly assessed by slump. It offers a straightforward but efficient way to evaluate the fluidity and consistency of the mix by measuring the vertical settlement of a concrete sample following the removal of a conical mold. It’s crucial to remember that slump by itself does not fully represent workability. Therefore, slump needs to be considered in conjunction with other elements to make sure that concrete satisfies the performance and durability standards required for the intended use.

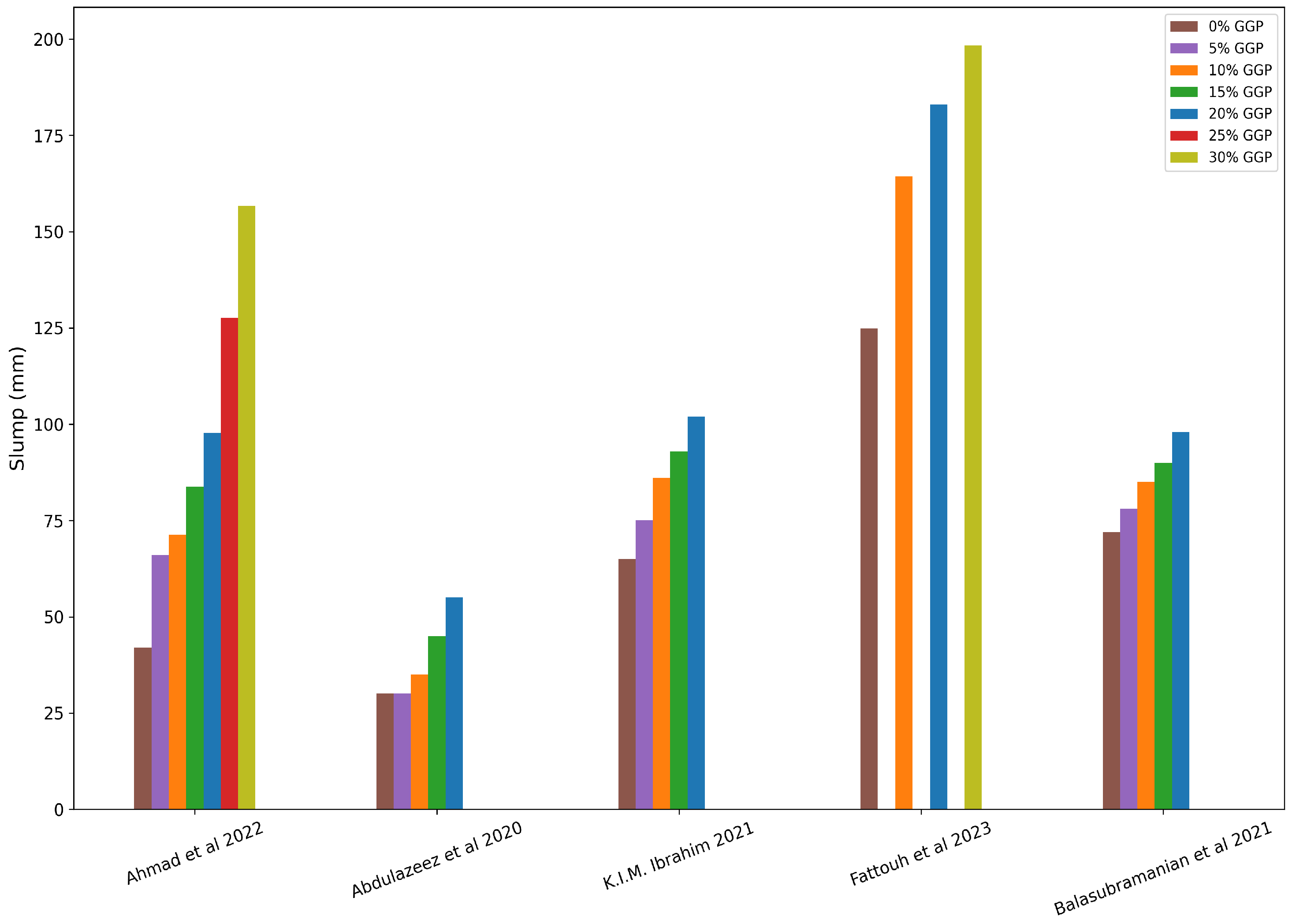

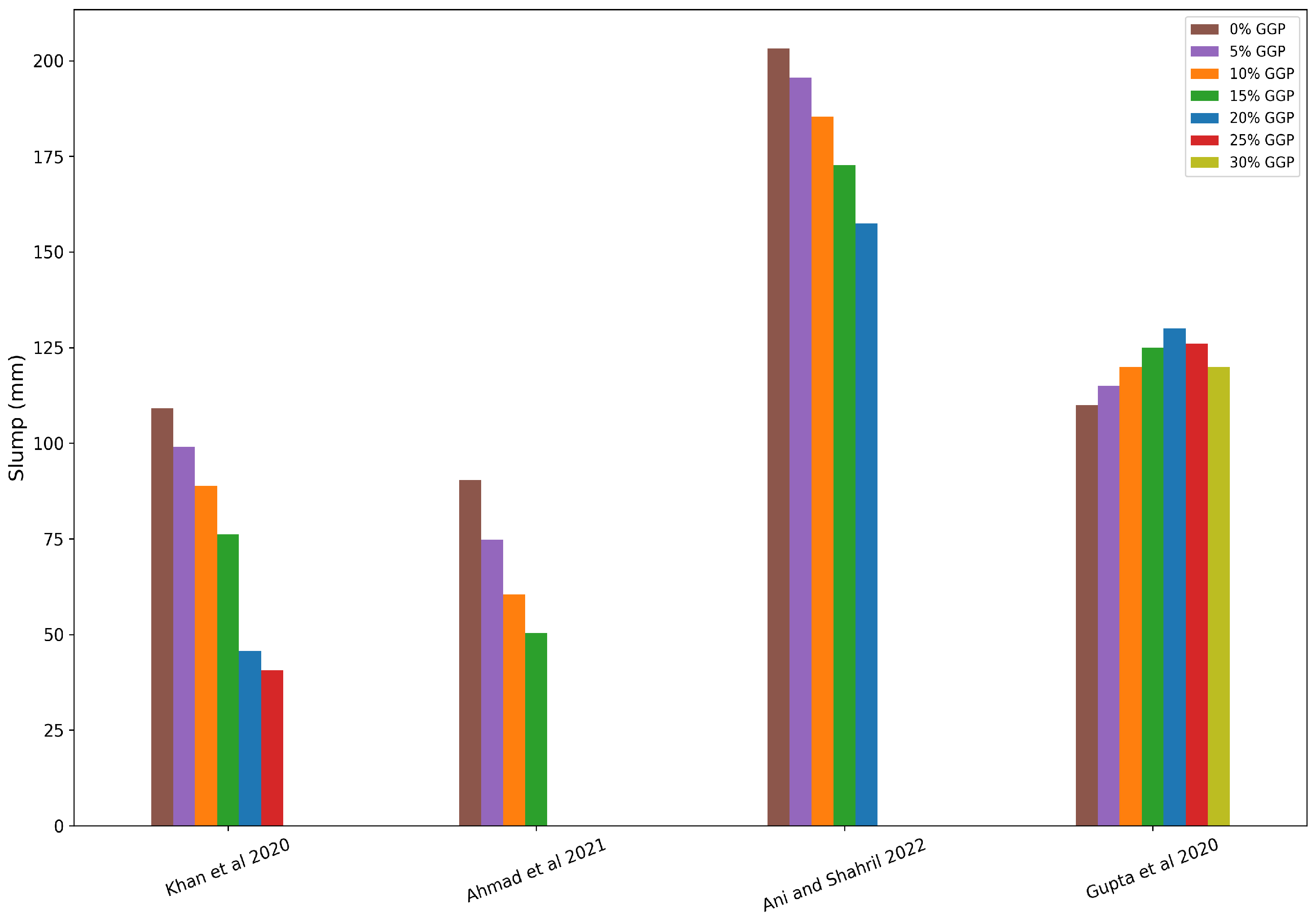

The

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 summarizes the slump flow with varying percentages of waste glass (0–30% in increments of 5%) in relation to partially replacing cement with GPP. Overall, the findings from the previous experimental data present significant discrepancies. Abdulazeez et al. [

63] , K.I.M. Ibrahim [

64], Fattouh et al. [

65], and Balasubramanian et al. [

56] reported an increase of approximately 83%, 57%, 37%, 36% in the slump value with 20% cement replacement levels by GGP, respectively. This is explained by waste glass’s poor water absorption and the availability of free water to reduce the internal friction between aggregates. Additionally, the strong pozzolanic activity of GGP strengthens the matrix, and its tiny particles fill the porosity of the coarse aggregates and lower internal friction, making the mix more flowable and workable overall. However, Khan et al. [

66], Ani et al. [

67], and Sayeeduddin & Chavan [

68] demonstrated a decrease of approximately 30%, 22%, 19% in the slump value with 20% cement replacement levels by GGP, respectively. This decrease in slump is explained due to the waste glass particles’ higher surface area and angular form, which necessitated more cement paste for coating and consequently decreasing the amount of cement paste available for lubrication. On the other hand, Gupta et al. [

69] found that the value of the slump gradually increased to approximately 18% for a 20% replacement level, and then gradually decrease to the slump value of control mixture till 40% replacement of cement by GGP. According to Ahmad et al. an experimental study[

7] reported a rise in slump value, while another study[

70] reported a fall in slump value, with higher levels of cement replacement by GGP.

In conclusion, these studies demonstrate the complex relationship of GGP and their effect on the workability of concrete, indicating that more research is required to provide precise recommendations for the ideal replacement amounts.

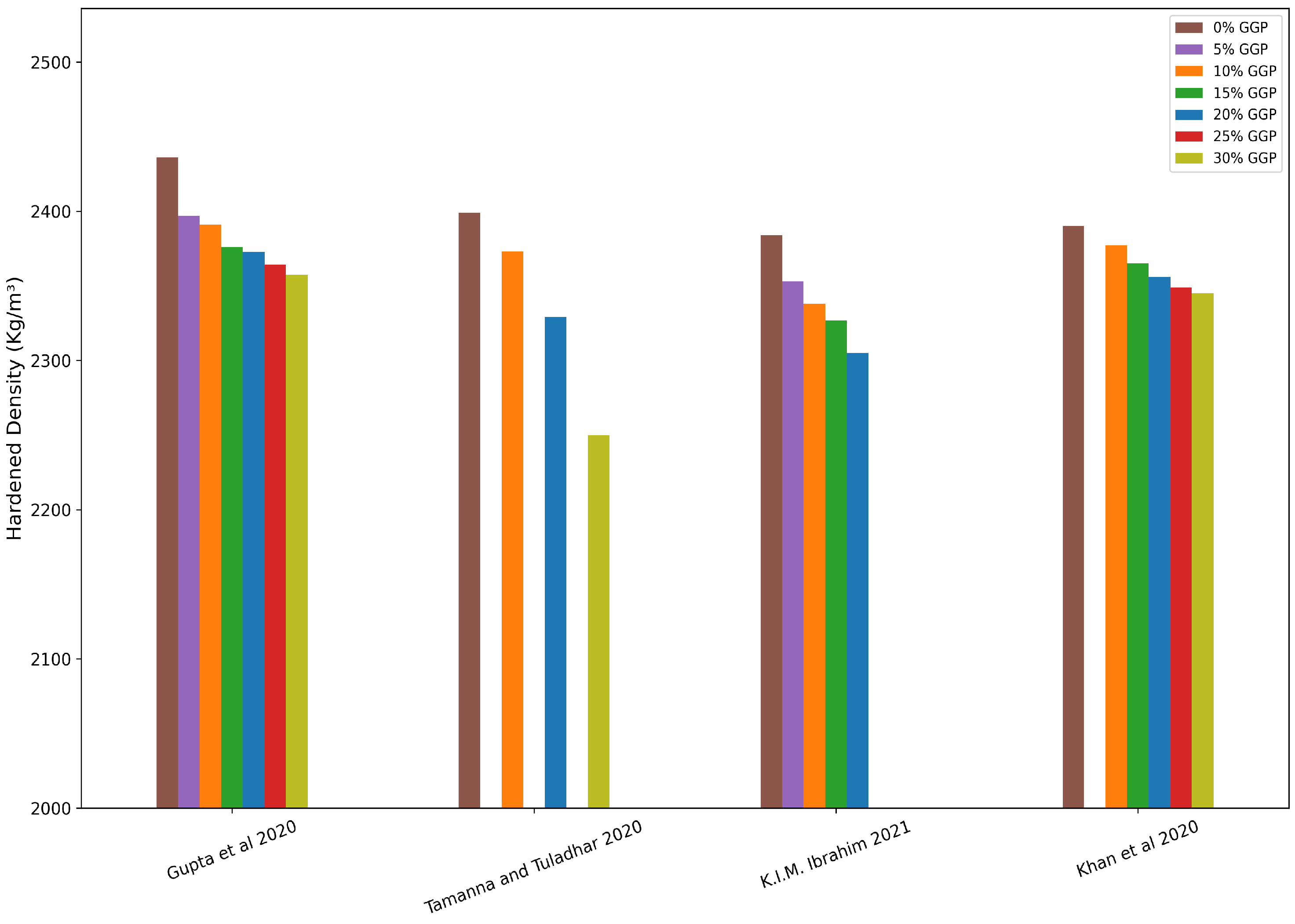

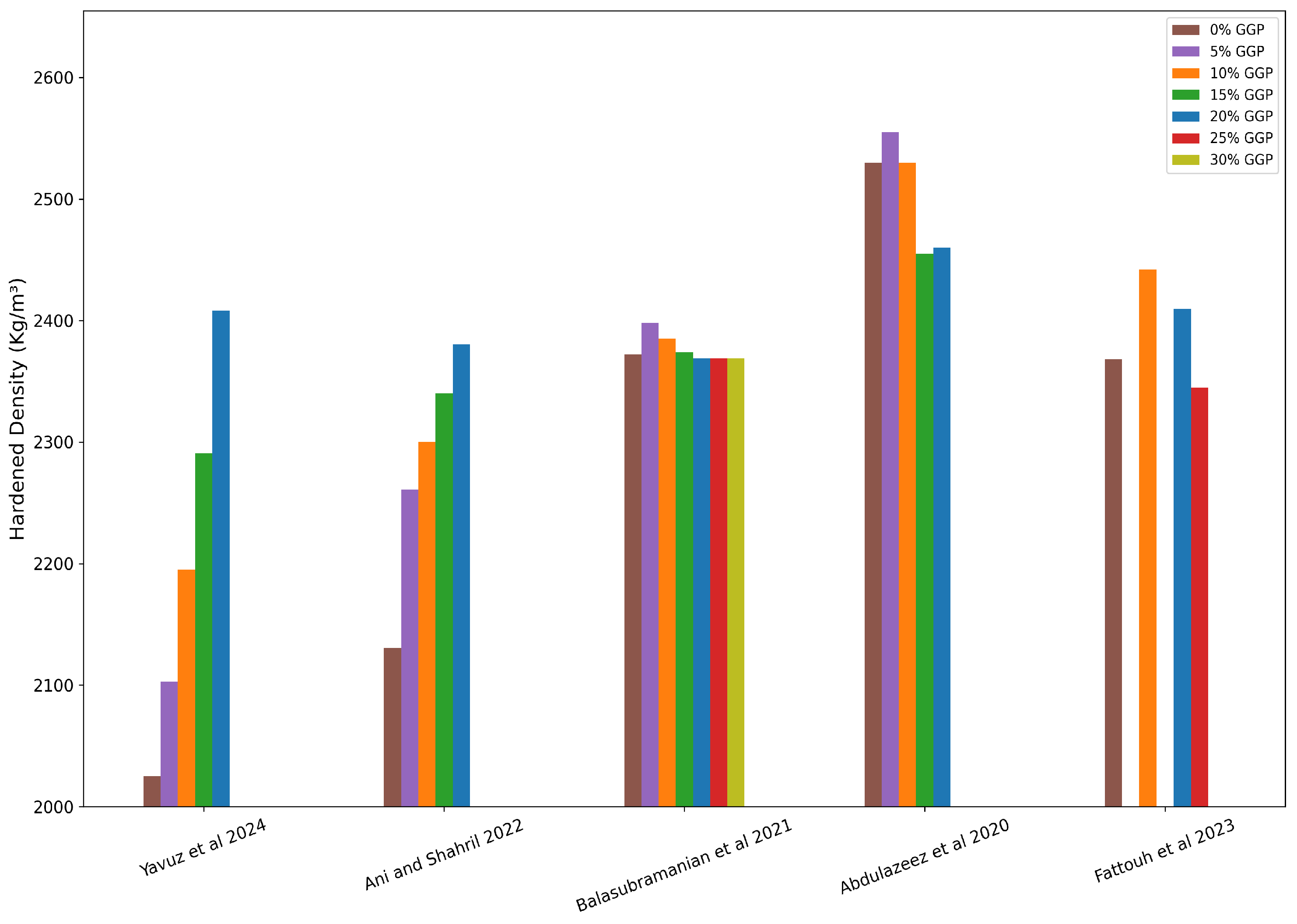

3.2. Density

Concrete’s density, which typically ranges from 2200 to 2500 kg/m³, depends on a number of variables, including the type and size of the aggregate, the cement concentration, and the air content. By adjusting the aggregate type, particle size distribution, cement concentration, and air content, concrete density can be tailored to improve durability and structural performance under particular environmental circumstances. Studies [

64,

66,

69,

71], have demonstrated a decrease in concrete density with increasing levels of cement replacement by GGP as depicted in

Figure 8. Ibrahim [

64], khan [

66], Gupta el al. [

69], and Tamanna & Tuladhar [

71] reported a decrease of approximately 3.3%, 1.4%, 2.6%, 2.9% in the concrete density with 20% cement replacement levels by GGP, respectively. This decrease is attributed to the lower specific gravity of GGP in comparison to cement and the development of micropores due to incomplete pozzolanic reactions. While several studies [

56,

63,

65] have reported an initial increase in concrete density to a replacement level, followed by a subsequent decline as the replacement percentage is further increased, as illustrated in

Figure 9 . However, other studies shows[

67,

72] increase in concrete density with incorporation higher GGP replacement levels. Ani et al. [

67] and Yavuz et al. [

72] reported an increase of approximately 5.3% and 19% in the concrete density with 20% cement replacement levels by GGP, respectively. It is concluded that this phenomenon is due to an increased C–S–H gel created by the increased pozzolanic activity of GGP with Ca(OH)

2. Thus, the matrix is densified and strengthened as a whole by filling the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) and reducing the weakest regions.

In conclusion, these results demonstrate the varying relationship of GGP and their effect on the density of concrete, indicating that more research is required to provide precise recommendations for the ideal replacement amounts.

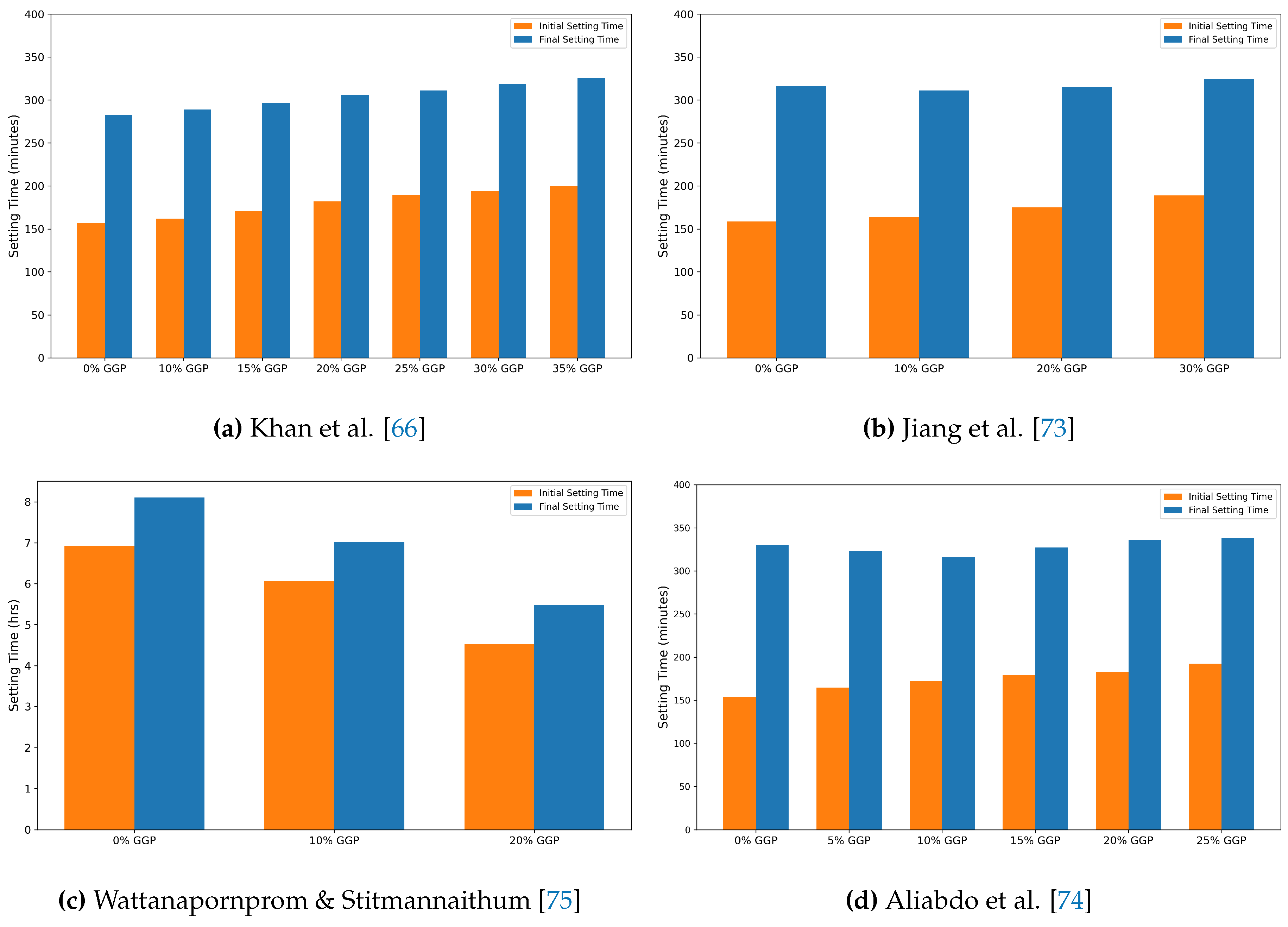

3.3. Setting Time

The setting time is an important factor that affects concrete workability, placing, and finishing. In order to maximize the curing process and ensure the required strength and longevity of the hardened concrete, it is crucial to comprehend the starting and final setting time frames. Previous studies [

66,

73,

74] have reported an increase in the initial setting time of concrete, as illustrated in

Figure 10. This phenomenon is explained by GGP’s reduced water absorption properties, which raise the amount of free water in the concrete matrix and reduce the rate at which the OPC paste condenses [

73]. However, a gradual increase in the final setting time was reported by Khan et al. [

66] for the increasing replacement levels. Studies by Jiang et al. [

73] and Aliabdo et al.[

74] demonstrated a specific replacement(5-20%) level leads to slight reduction in the final setting time compared to the control mixture. On the other hand, Wattanapornprom & Stitmannaithum [

75] demonstrated a delay in the initial and final setting time of GGP incorporated concrete. The initial setting time was decreased by 12% and 35%, while the final setting time was reduced by 14% and 32% for a replacement level of 10% and 20 %, compared to the control mixture.

4. Mechanical Properties

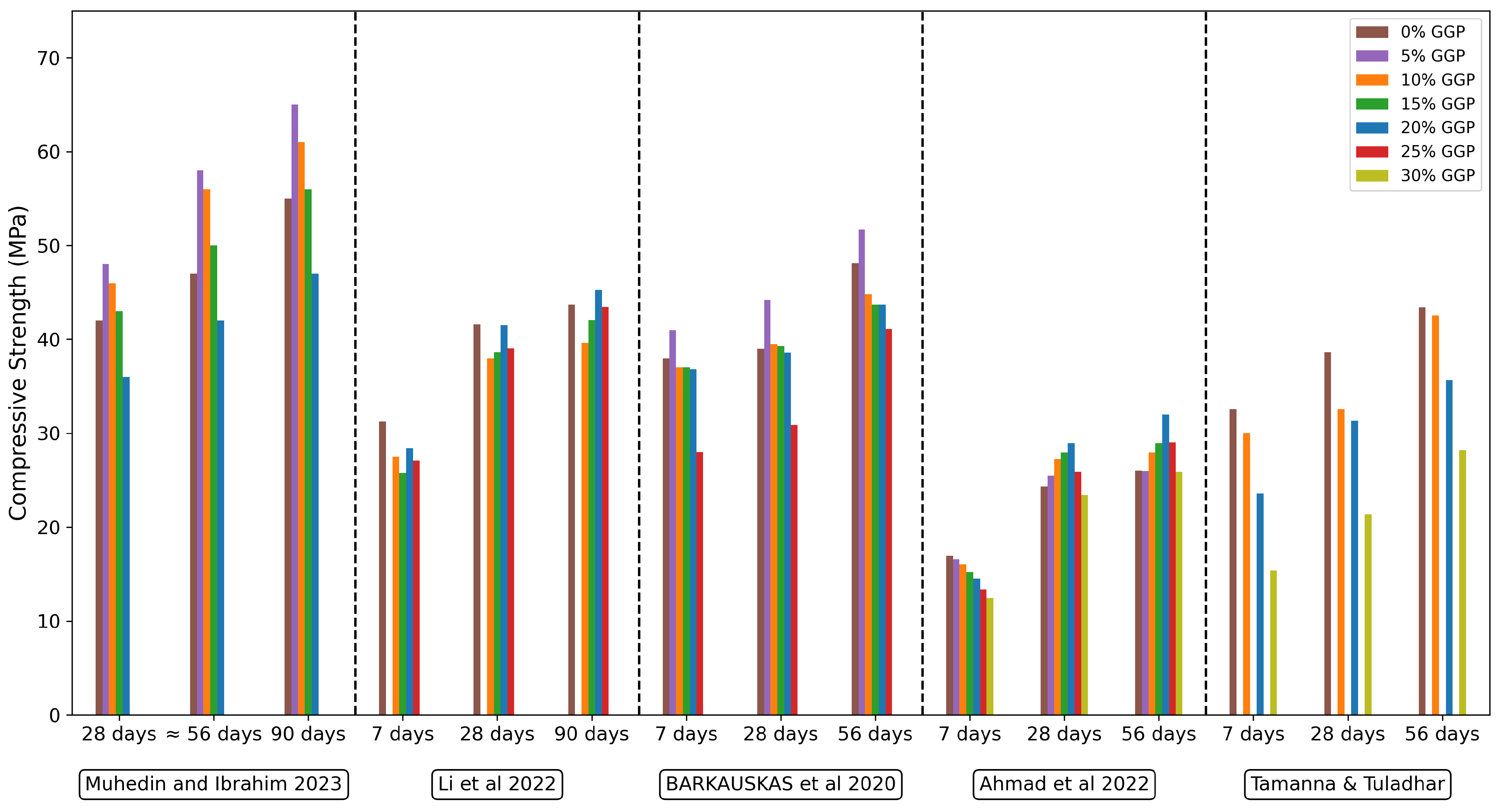

4.1. Compressive Strength

The compressive strength of concrete, which indicates its capacity to sustain structural loads, is essential to the design and quality assurance of concrete infrastructures. Several studies [

7,

57,

71,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81] have reported that, in comparison to the control mix, the addition of GGP to concrete mix designs affects the compressive strength at different curing ages. The pozzolanic process that GGP starts inside the concrete matrix is largely responsible for this effect, which over the time promotes improved strength and durability. The compressive strength results for various GGP replacement levels and curing durations are presented in

Figure 11.

Muhedin and Ibrahim [

76] examined the effect of partial replacement of cement with GGP at a water-to-cement (W/C) ratio of 0.48 with different GGP replacement levels (5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%) to a control mixture without GGP for 28, 56, and 90 days. The findings showed that, for all evaluated curing ages, concrete containing GGP had greater compressive strength than the control mixture up to a 15% replacement level. The compressive strength increased maximum at 5% replacement level compared to the control mix with approximately 14%, 23%, and 18% for 28, 56, and 90 days respectively. The main reasons for the 15% improvement in compressive strength when GGP is used in place of cement are the material’s pozzolanic activity and filler effect, which improve the microstructure and longevity of the concrete. Similar findings was reported by Ahmad et al.[

7] at 0.53 W/C with GGP replaced at 0% to 30% levels. Regardless of the replacement level, the GGP-modified mixtures continuously showed compressive strength values that were higher than those of the control mixture at later curing days although the 7 days strengths were lower. The compressive strength was approximately 19% and 23% on 28 days and 56 days respectively for 20% replacement of cement by GGP. This resulted from the well-known fact that pozzolanic reactions are slow and do not provide strength at a young age [

7]. On later curing stages (28 and 56 days), additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel is formed when the amorphous silica in GGP combines with Ca(OH)

2, produced by cement hydration. Thus by strengthening the internal link structure, filling capillary holes, and densifying the cement matrix, this secondary C-S-H formation increases the GGP concrete’s compressive strength. Li et al[

57], explored GGP replacement levels from 0% to 25% at a 0.55 W/C ratio, and by Barkauskas et al. [

77], studied replacement levels from 0% to 30% at a 0.46 W/C ratio showed relative increase in compressive strength at later curing days due to pozzolanic reaction of GGP. Li et al[

57] reported 20% replacement level surpassed by 5% the compressive strength of the control mixture at 90 days . Similarly, Barkauskas et al. [

77] reported 5% replacement level consistently surpassed the compressive strength of the control mixture by approximately 8%, 13%, and 8% at 7, 28, and 56 days respectively. However, Tamanna and Tuladhar [

71] experimental results reported none of the replacement level exceeded the compressive strength of control mixture on 7, 28, 56 days of curing at 0.535 W/C. The compressive strength of 10% replacement level was highest among all and was 8%, 16%, and 2% lower than the control mixture at 7, 28, and 56 days respectively.

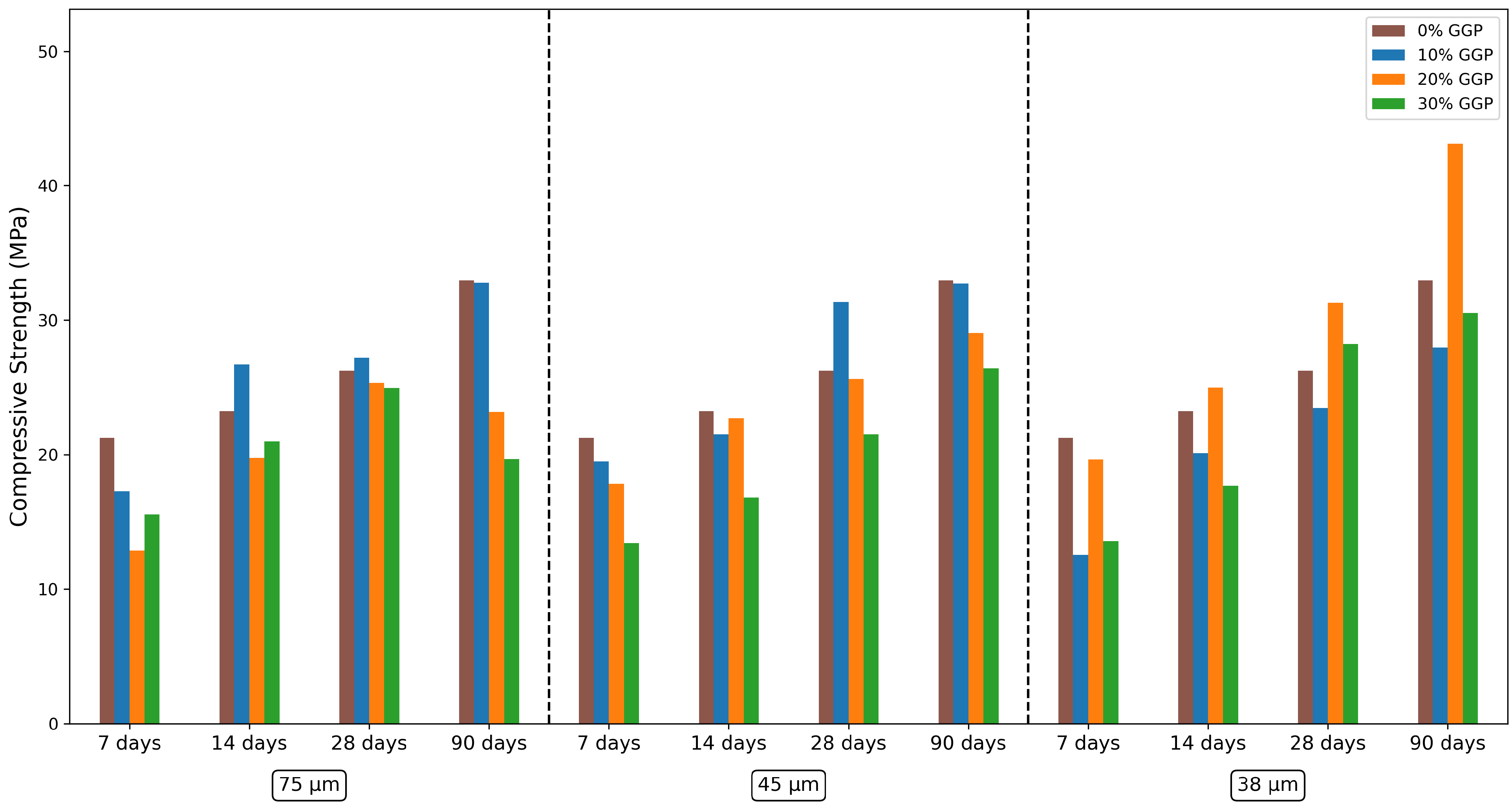

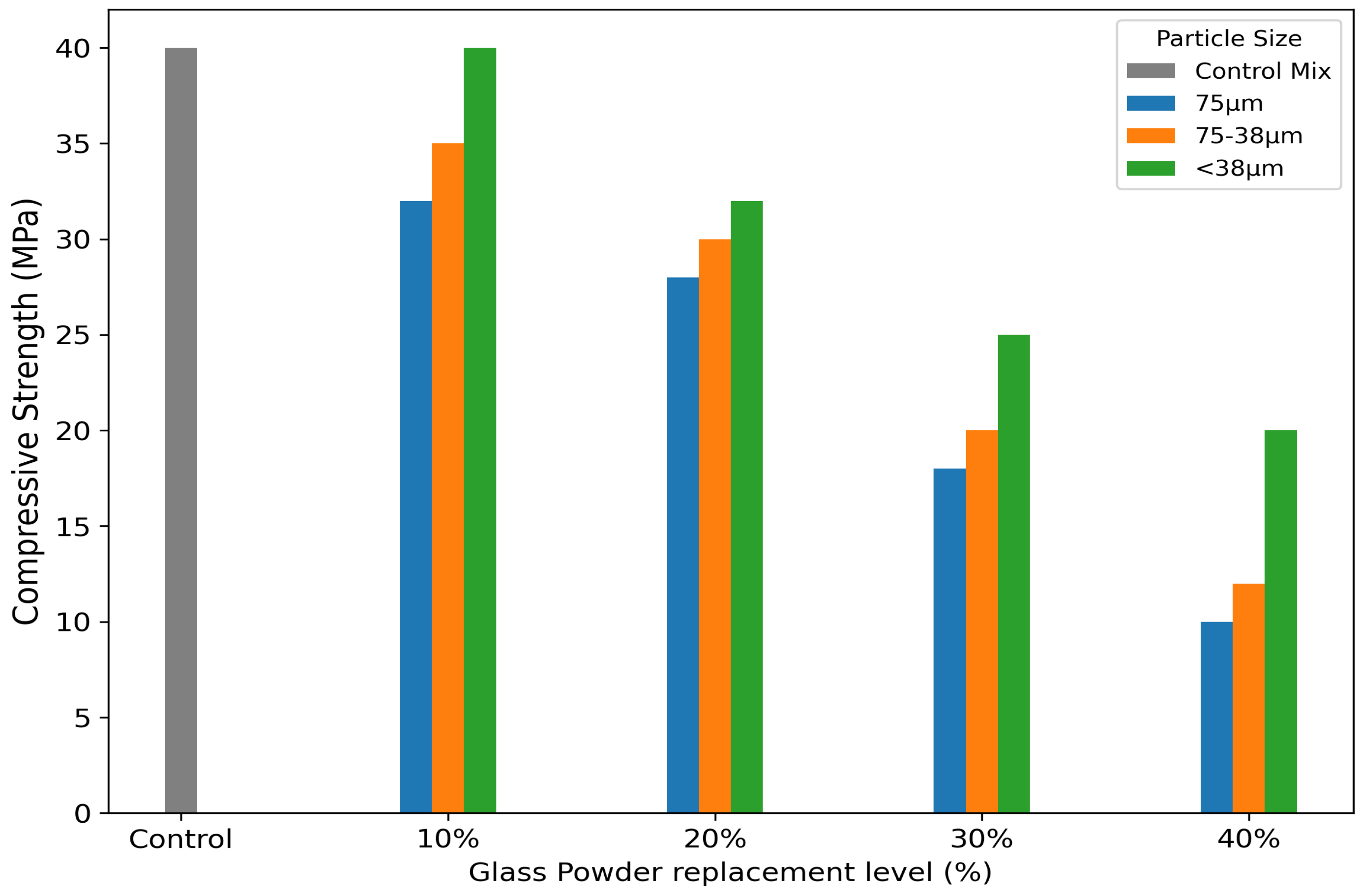

The particle size of GGP at the same cement replacement level has shown a considerable effect on the compressive strength of the concrete incorporated with GGP in previous studies [

78,

79]. Letelier et al. [

78] studied the effect of three different particle sizes(74

m,45

m, and 38

m) of GGP on the compressive strength of concrete incorporated with GGP as a partial replacement of cement as shown in

Figure 12. The result showed that the compressive strength of GGP incorporated concrete increases as the particle size of the GGP gets finer. At 14, 28, and 90 days of curing, the GGP, which had a particle size of 38

m, exceeded the control mixture’s compressive strength by approximately 7%, 19%, and 30% respectively at a 20% replacement level. This suggests that GGP can be used as a replacement of traditional pozzolans when subjected to prolonged curing durations. The finer particle size, which raises the surface area accessible for pozzolanic reactions, is responsible for the improved performance. Because there is more contact between the reactive particles and the accessible Ca(OH)

2 in the mixture, a larger surface area promotes a faster rate of reaction [

82]. Tamanna et al. [

79] reported similar findings on the effect of 0%-40% cement replacement with GGP size(75

m,75-38

m,<38

m) on the compressive strength of concrete at a 0.45 W/C ratio, as illustrated in

Figure 13. The compressive strength of 10% GGP incorporated concrete with particle size <38

m showing comparable strength to that of the control mix at 28 days of curing. For particle size <38

m and 10% replacement level, the compressive strength is reported to be approximately 14% and 25% than that of GGP with particle size 75-38

m and 75

m respectively.

In addition,

Table 6 shows the summary of the compressive strength development with GGP incorporated concrete and optimum GGP replacement level.

4.2. Strength Activity Index (SAI)

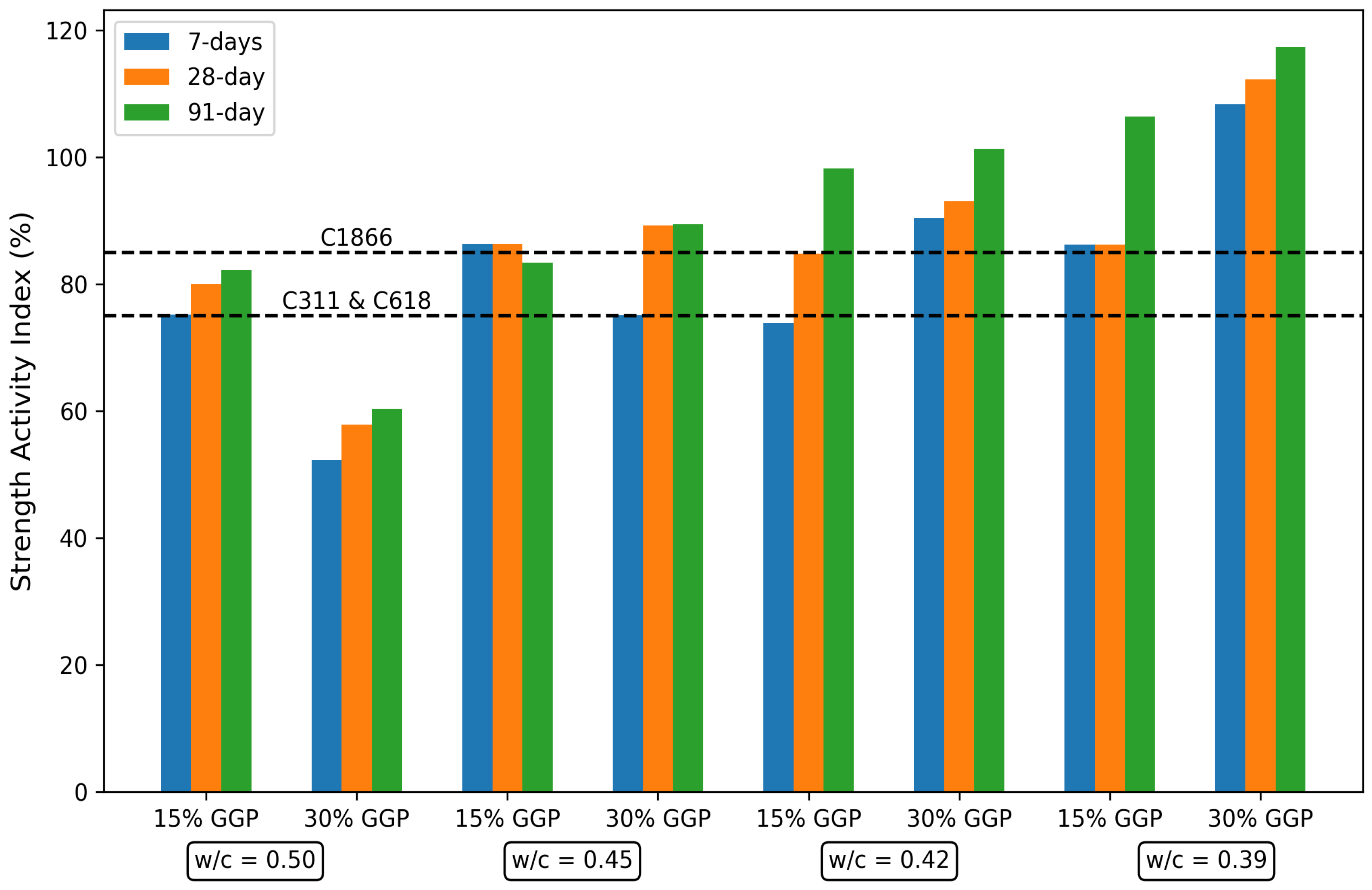

The strength activity index (SAI) serves as an important parameter that quantifies the pozzolanic reactivity of supplementary cementitious materials by measuring their influence on the compressive strength development when used as a partial replacement for cement in concrete. It is the ratio of a concrete mix’s compressive strength with a certain amount of SCM substituted to that of a control mix that does not contain SCM on identical testing and curing conditions. According to ASTM [

92,

93], any GGP to be used as pozzolan at 7 and 28 days must have a SAI value of at least 75%. However, ASTM-C1866 [

62] requires GGP-incorporated concrete to have a minimum of 85% SAI at 28 days. But according to ASTM-C1866 [

62], GGP-incorporated concrete must have at least 85% SAI after 28 days. Kalakada et al [

2] evaluated SAI at three curing ages— 7 days, 28 days, and 91 days— with the w/c ratio : 0.50, 0.45, 0.42, and 0.39 and reported higher SAI values at higher curing days and lower W/C ratio as illustrated in

Figure 14. This could be attributed to the combined effects of maximum pozzolanic activity and concurrent water reduction, which occur simultaneously [

2]. Notably, all replacement level at all curing days achieved minimum SAI of 75% in accordance with ASTM-C311 and ASTM-C618, with exception of mixes containing 30% GGP. The GGP with a water-to-cement (W/C) ratio of 0.39 continuously satisfied the necessary 85% SAI value for ASTM C1866 during the course of all curing phases. Similar results were reported by Afshinnia and Rangaraju [

94] with GGP particle sizes (17

m and 70

m), Shao et al. [

48] with GGP particle sizes (38

m, 75

m, 150

m), and Shi et al. [

95] with GGP particle sizes (approximately 12

m, 20

m, 75

m, and 110

m ).

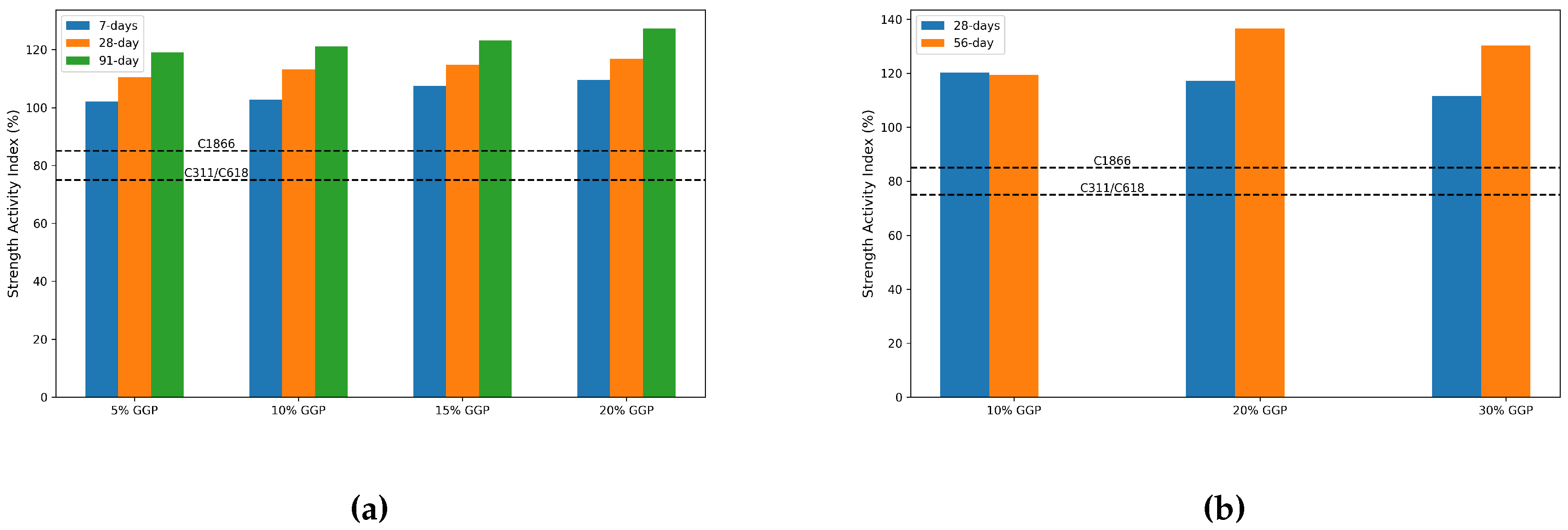

Similarly, Patel et al. [

96] demonstrated that GGP, with a mean particle size of approximately 1

m and up to 20% replacement at a 0.4 W/C ratio, exhibits SAI values exceeding 100% at all curing days as illustrated in

Figure 15(a). The 20% replacement level shows the highest SAI values among all with approximately 109%, 116%, and 127% at 7, 28, and 90 days of curing period respectively. Furthermore, Banerji et al. [

80] also reported that all mixes exceeded the ASTM C1866 requirement of 85% SAI at both 7 and 28 days as depicted in

Figure 15(b), highlighting its potential as a SCM in concrete.

4.3. Tensile Strength

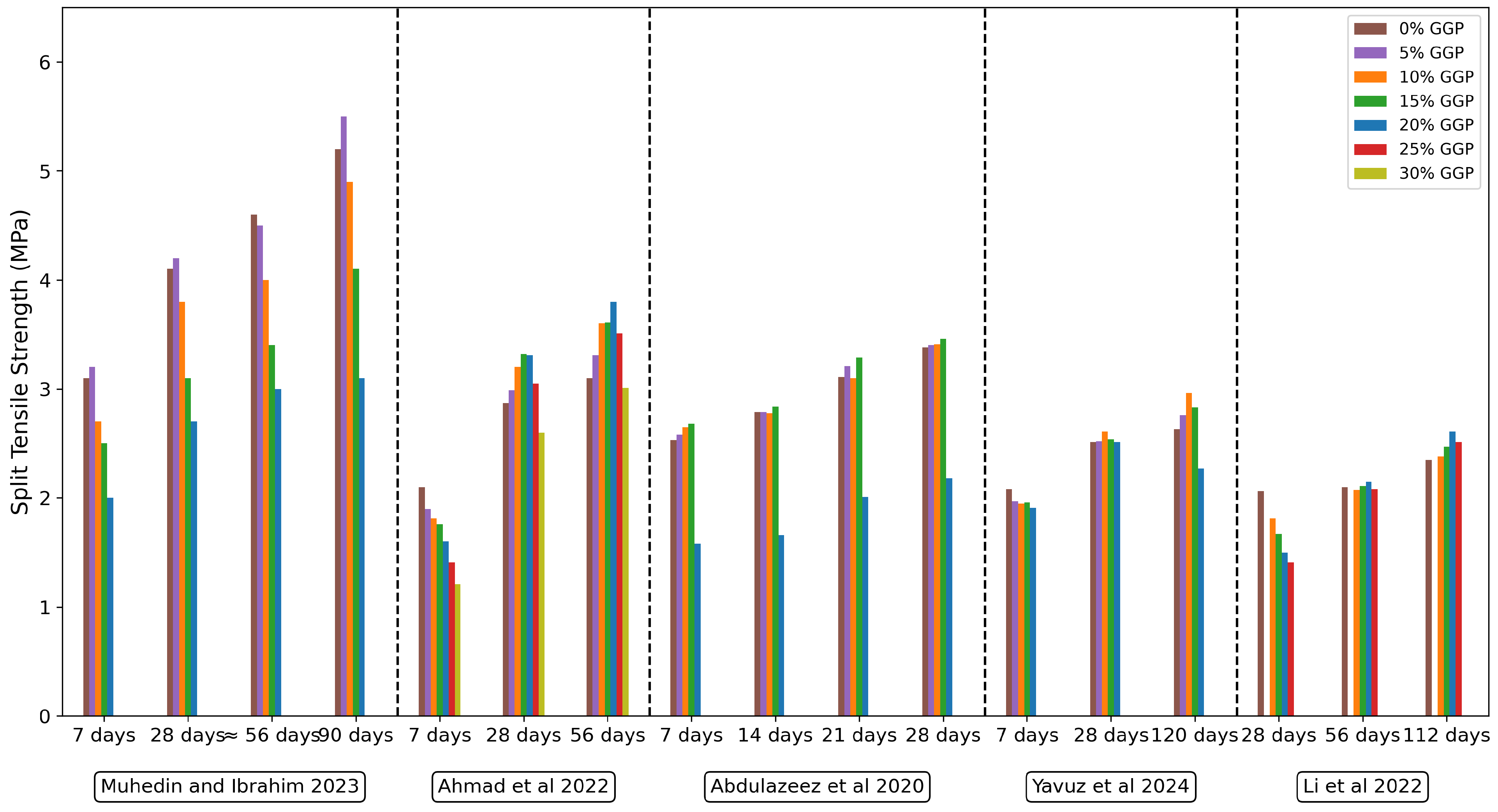

Concrete’s ability to withstand brittle failure under tensile loads is evaluated by measuring its split tensile strength, which is around 10% of its compressive strength. This test helps determine how easily concrete may crack, which is important for the longevity and integrity of the structure. The split tensile strength of GGP incorporated concrete from recent studies is depicted in

Figure 16.

Muhedin and Ibrahim [

76] studied the effect of partial cement replacement with GGP at a 0.48 W/C ratio, evaluating compressive strength development over 7, 28, 56, and 90 days for mixes with GGP replacement levels of 0-30%. The highest peak compressive strength was reported for a 5% replacement level of cement with GGP across all curing durations. This can be attributed to the pozzolanic activity of GGP, which enhances strength development during the secondary hydration phase. Beyond 5% replacement level, the strength of GGP concrete was lower than that of the control mixture. Another study by Ahmad et al. [

7] at 0.6 W/C for 0-30% cement replacement level with particle size lower than 38

m at 7, 28, 56 days reported higher tensile strength for GGP incorporated mixes at 28 and 56 days. The tensile strength was approximately 15% and 22% at 28 and 56 days respectively for 20% replacement level. However, at 7 days, the tensile strength was lower than the control mixture for all the GGP replaced concrete. This is because the pozzolanic reaction between the silica from GGP and the Ca(OH)

2 generated during cement hydration is largely responsible for the improvement in tensile strength at later curing ages. Over time, this reaction produces more calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, which greatly increases the concrete matrix’s density and strength. Additionally, it was reported that the concrete with 30% GGP substitution level had an approximately 42%, 9%, and 3% lower compressive strength than the control mixture at 7, 28 and 56 days. This decrease is explained by the dilution effect, which occurs when a large amount of cement is substituted, lowering the amount of calcium hydroxide available and the total amount of binder. As a result, the pozzolanic reaction’s scope is constrained, which inhibits the growth of strength. Similar results was obtained by Yuvaz et al. [

72] on utilization of 40

m GGP at 0.35 W/C. GGP added 5%, 10%, 15%, 20% samples had 7-day tensile strength values that were 7.7%, 15.4%, 16.2%, and 23.1% lower than the control mixture, respectively. At 28 days, however, the tensile strength values were 7.5%, 14.3%, 14.9%, and 12.4% higher than the control mixture, respectively. The increases were 5.7%, 9.3%, 6.7%, and 4.1% after 120 days, indicating that GGP had a beneficial long-term impact on tensile strength. The full hydration of cementitious materials, which promotes the development of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, is also responsible for the strength increase at later curing ages. Similar results were found in pervious concrete by Li et al. [

97], reported higher tensile strength at later curing ages with replacement levels ranging from 0 to 25% and W/C ratios of 0.22, 0.24, 0.26, and 0.28. The splitting tensile strength peaked at 20% GGP replacement after first declining at 28 days and then progressively increasing over the next 56 days. In contrast, in comparison to the control mix, GGP-incorporated concrete showed greater tensile strength up to a 15% replacement level after seven days, according to Abdulazeez et al. [

63]. GGP concrete’s tensile strength at 14 days was on par with the control mixture’s. Nevertheless, by 21 days, the tensile strength of the concrete containing GGP was either the same as or greater than that of the control mix, indicating the positive impact of GGP on the development of later-age strength.

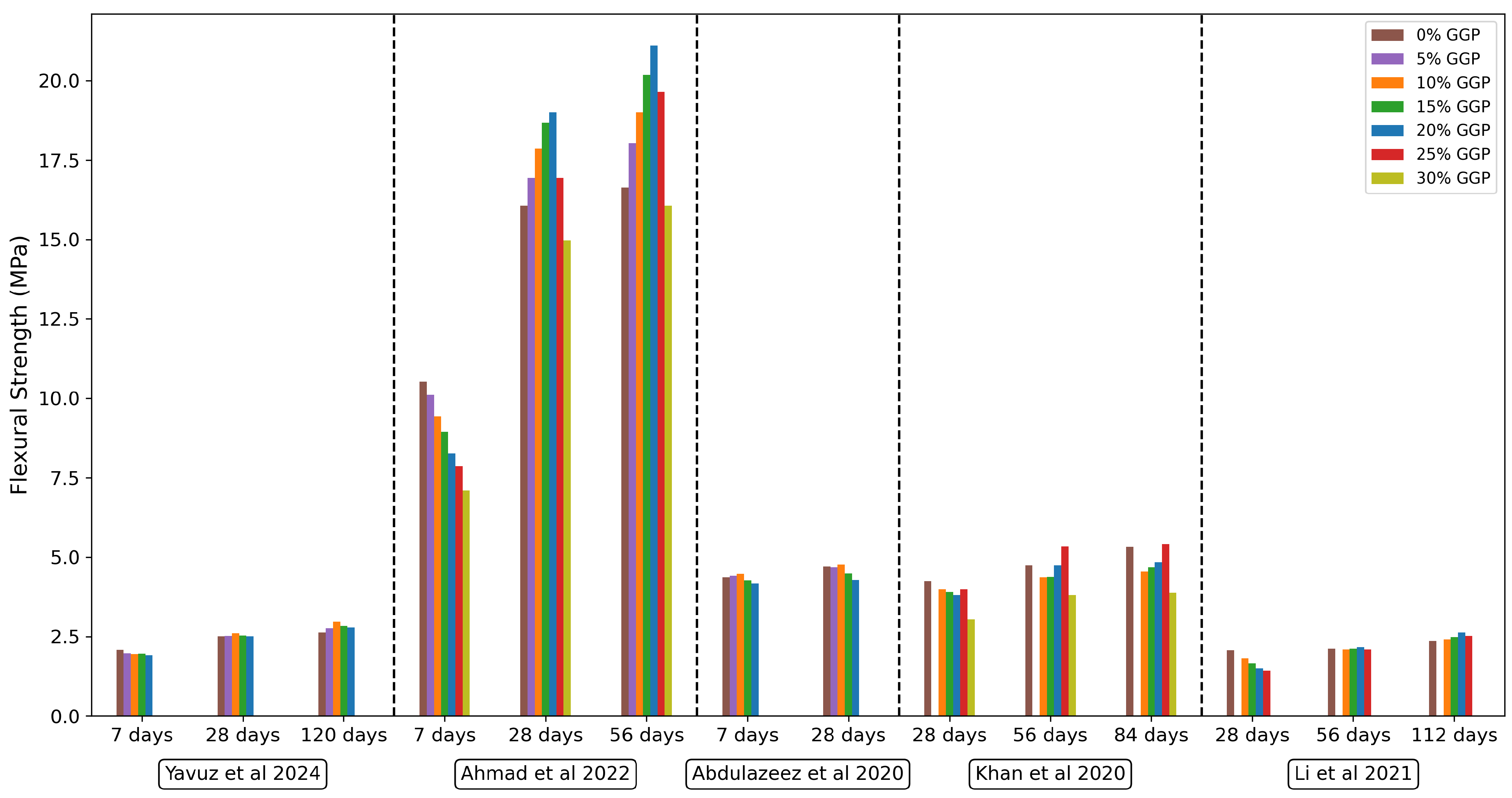

4.4. Flexural Strength

Concrete’s flexural strength or modulus of rupture , is a crucial factor that indicates how resistant it is to bending stresses. It gives information on the material’s resistance to tensile forces brought on by bending, which makes it a crucial characteristic for designing structural components like pavements, slabs, and beams that are subjected to flexural stresses. The split tensile strength of GGP incorporated concrete from recent studies is illustrated in

Figure 17.

Yuvaz et al. [

72] studied prismatic molds incorporated with GGP with dimensions of 100×100×400 mm under 3-point loading for flexural strength. The findings reported that the control mix had approximately 5.3%, 6.2%, 5.7%, and 8.1% higher 7-day flexural strength than the GGP-incorporated samples 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% respectively. The flexural strength of the samples with GGP added, however, exceeded that of the control mixture at 28 and 120 days. For 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% replacement levels, at 120 days, the respective flexural strength reported was approximately 4.9%, 12.5%, 7.6%, and 6.1% higher than the control mix. The pozzolanic reactivity of GGP, which promotes the production of more C-S-H gel and gradually improves the concrete’s flexural qualities, is responsible for this improvement at later curing ages. Li et al. [

97] observed similar results for pervious concrete that included GGP. The three-point loading method was used to measure the flexural strength of samples measuring 100 × 100 × 400 mm. At 56 and 112 days of cure, it was reported that concrete with 10% GGP had approximately 0.9% and 2.1%, while 20% GGP had approximately 2.8% and 11.9% higher flexural strength than the control mix respectively. Significant amounts of

and

from GGP react with Ca(OH)

2 during the prolonged curing period, forming C-S-H and C-A-H gels, which is responsible for this improvement. A denser matrix with lower permeability is the outcome of the microstructure being refined by these hydration products [

97].

According to Khan et al [

66], at later ages of 56 and 84 days, there was a rise in the flexural strength for 152.4 mm wide × 152.4 mm deep × 762 mm-long beam incorporated with GGP. While a notable improvement was noted at 56 days by 12.6%, the strength gain for 25% replacement was around 2% greater than that of regular concrete after 84 days. At 28, 56, and 84 days, approximately 28%, 20%, 27% lower flexural strength was demonstrated by beams with a 30% replacement level respectively, which is explained by the primary hydration process producing less Ca(OH)

2. This restricted Ca(OH)

2 availability inhibits the

pozzolanic process to form strength imbibing C-S-H gel. Similar results were reported by Abdulazeez et al. [

63] for the flexural strength of GGP-incorporated concrete. Their study, conducted on beams measuring 150 mm × 150 mm × 750 mm, showed comparable trends, highlighting the influence of GGP replacement levels on the flexural performance of concrete. The beams had a 2.3% and 1.5% higher flexural strength for 10% replacement level at 7 and 28 days respectively . Ahmad et al. [

7] examined 150 mm × 150 mm × 750 mm GGP-incorporated beam samples (#4 bar as longitudinal reinforcement and #2@125 mm c/c stirrup) subjected to four-point loading. The results demonstrated that glass substitution could result in a 20% increase in flexural strength at 28 and 56 days. But the strength started to decline after a 20% replacement level. Additionally, the compaction process became more difficult due to decreased flowability at greater waste glass doses (30% by weight of cement). This required more compaction, which caused pores to form in the cured concrete and ultimately decreased its flexural strength.

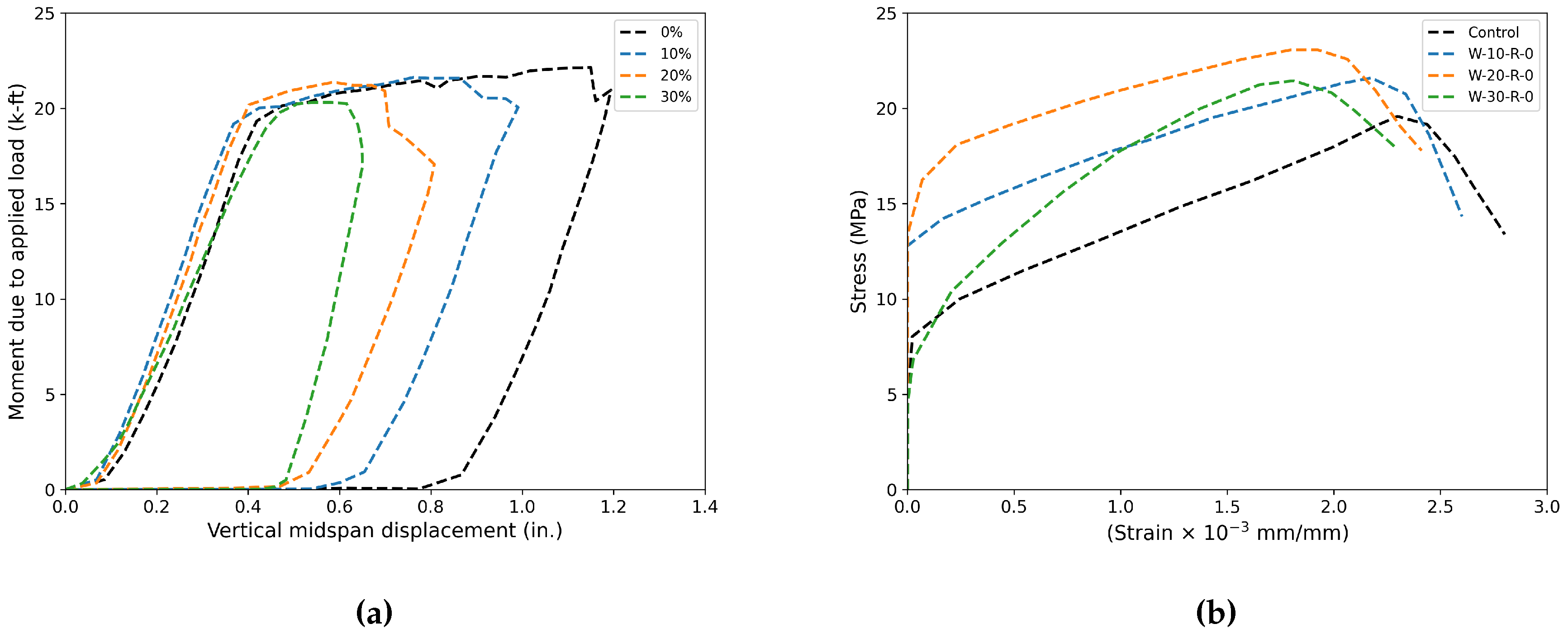

From previous studies[

58,

70], partial cement replacement by GGP has influence on the ductility of concrete beams. Christiansen and Dymond [

58] examined the effects of different cement replacement levels (10%, 20%, and 30%) at 0.46 W/C on the ductility of a reinforced concrete beam measuring 15.24 cm × 25.4 cm × 1.83 m. According to their findings, although the peak flexural strength variation is insignificant, the ductility of the beam gradually decreased as the cement replacement percentage rose as depicted

Figure 18. This shows how higher replacement levels may affect the performance of concrete structures in terms of their capacity to experience plastic deformation prior to failure. Ahmad et al. (2022) [

70] conducted a study on the effect of GGP incorporation in concrete beams. The findings showed that at a 20% GGP replacement level, maximal ductility increased. But after this point, the ductility of the beams decreased as the replacement level increased further.

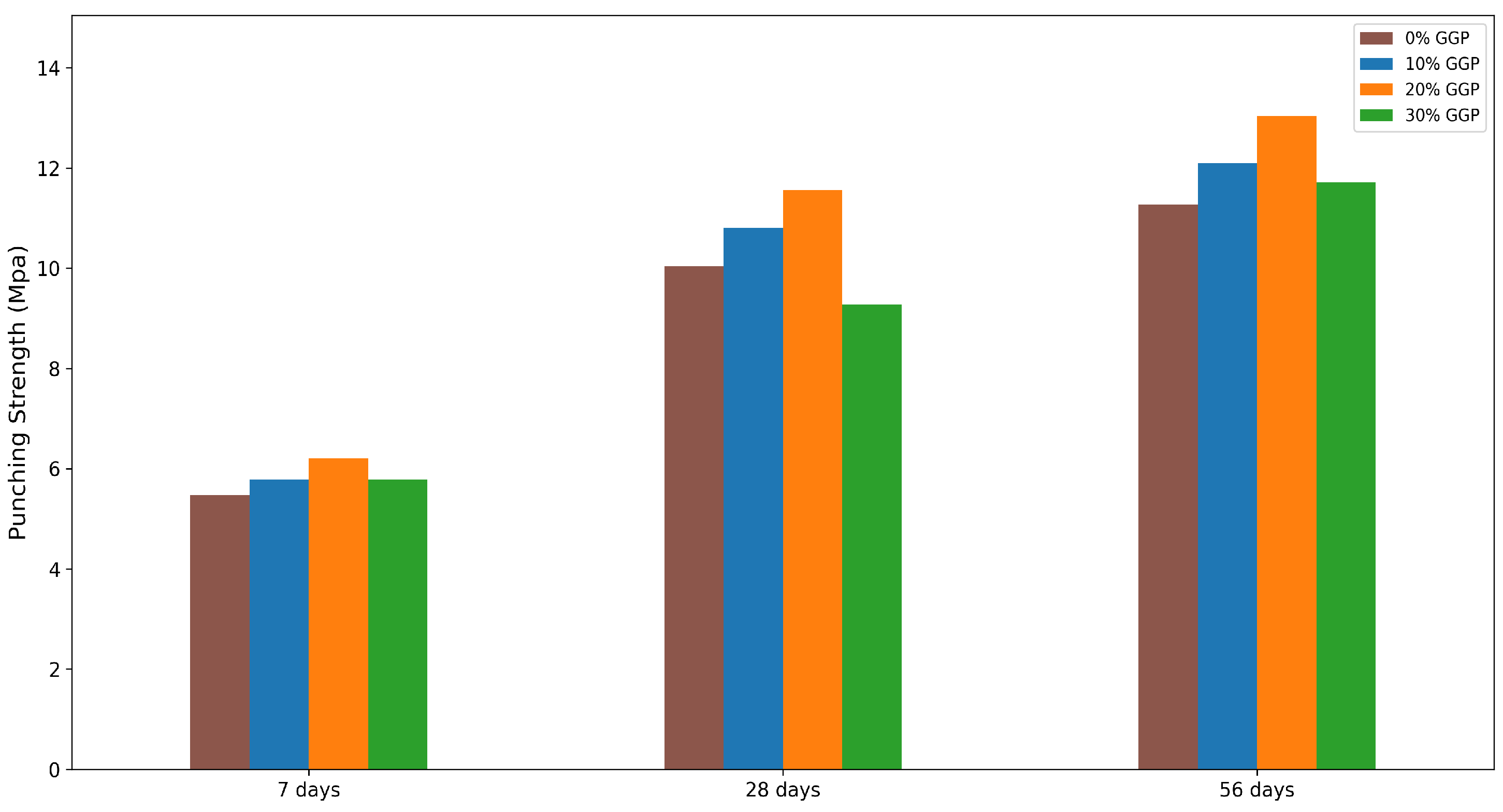

4.5. Punching Strength of Concrete

The punching strength of concrete is a critical factor in the structural integrity of slabs and foundations, particularly under concentrated loads. A limited studies have been found in literature for GGP incorporated as a partial replacement to the cement in concrete highlighting a need for further research to understand its full potential and performance characteristics. Ahmad et al [

70] performed punching shear test on a GGP incorporated concrete slab specimen of 500mm x 500 mm at 7, 28, 56 days. The authors replaced 10% and 20% cement with GGP at 0.467 W/C. They reported concrete’s punching strength increased up to a 20% replacement level; after that, it fell due to more voids as a result of low workability. At 56 days, the punching strength exhibited by 20% GGP replacement level was observed to be approximately 13% higher than control mixture due to micro fillings due to secondary hydration in concrete matrix. A 20% waste glass substitution produced the best punching strength at 56 days, whereas 0% substitution produced the lowest strength for all curing days.

Figure 19.

Relation of % GGP replacement and Punching Strength at different curing days reported in different studies. [

70].

Figure 19.

Relation of % GGP replacement and Punching Strength at different curing days reported in different studies. [

70].

5. Conclusions

This study explores the effect of using GGP as a sustainable material that serves as a supplementary cementitious material in concrete production. As GGP reduces the amount of cement required in concrete, it minimizes the possible environmental impact caused during cement production. In addition to environmental benefits, the use of GGP is also beneficial in enhancing different concrete properties due to its higher silica content. For this reason, this study has focused on the effect the fresh and mechanical properties of concrete produced by using GGP as a cement replacement material. The reviewed concrete properties include workability, density, setting time, compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, and punching strength. The existing literature on the effect of GGP addition to partial cement replacement was reviewed on each of these properties, and the major findings are listed below:

The slump increases with a higher amount of GGP in some cases, while in other cases the slump value decreases. The increase in slump occurs as a result of lower water absorption and reduced internal friction from the presence of GGP. However, the decrease in slump results from the angular shape of GGP particles with high surface area, which requires more cement paste for coating. Further research is recommended to clarify this varying effects on slump.

An increase in the GGP content decreases concrete density. This occurs due to the low specific gravity of GGP and incomplete pozzolanic reactions. However, other findings show increase in concrete density because of densification of matrix by filling of ITZ by additional C-S-H gel. Further research is recommended to gain a deeper understandings of these contrasting results.

The addition of GGP in concrete increases the initial setting time. This occurs because the glass particles of GGP reduce water absorption, increasing the amount of free water in the mixture and delaying the initial setting time. However, studies claim a decrease in the final setting time, while others report an increase. Further research is recommended to better understand this difference in results in final setting time.

The addition of GGP improves the compressive strength at later curing ages due to the pozzolanic reaction forming an additional C-S-H gel, while at early curing stages, the compressive strength remains lower compared to the control mix. Furthermore, finer GGP particle size result in higher compressive strength.

Similar outcomes for tensile strength and flexural strength are noted. The strength values improve at later curing stages due to additional pozzolanic reactions and a denser concrete mix. However, ductility decreases with an increase in the amount of GGP.

The punching strength is enhanced due to the addition of GGP because of micro fillings due to secondary hydration in concrete matrix.

The optimum dosage of GGP depends upon different factors such as mix design, particle size, specific surface area and glass chemical composition, type and color.

In conclusion, the review summarizes the impact on various concrete properties due to addition of GGP as a partial replacement of cement. In majority of instances, the incorporation can not only contribute to sustainable construction practice but also improve mechanical and durability properties. Although most of the publications indicate that GGP enhances these qualities, other show the contrary. These discrepancies is attributed to complex interaction between GGP and concrete properties. In this regard, this review suggests that further research is recommended to determine the reliable correlation between GGP replacement and concrete properties.

Author Contributions

Writing original draft, Sushant Poudel; conceptualization, Sushant Poudel, Utkarsha Bhetuwal and Diwakar KC; methodology, Sushant Poudel, Utkarsha Bhetuwal and Diwakar KC ; formal analysis, Sushant Poudel, Utkarsha Bhetuwal, Pravin Kharel, Sudip Khatiwada, Bipin Lamichhane, Sachin Kumar Yadav and Saurabh Suman; investigation, Sushant Poudel, Utkarsha Bhetuwal, Pravin Kharel, Sudip Khatiwada, Bipin Lamichhane, Sachin Kumar Yadav, and Saurabh Suman; resources, Sudip Khatiwada and Diwakar KC; review and editing, Sudip Khatiwada and Diwakar Kc; data collection, Sushant Poudel and Utkarsha Bhetuwal, Pravin Kharel, Bipin Lamichhane, Sachin Kumar Yadav and Saurabh Suman; grammatical improvement, Sudip Khatiwada and Diwakar KC; formatting, Sudip Khatiwada; revising, Sushant Poudel, Utkarsha Bhetuwal, Pravin Kharel, Bipin Lamichhane, Sachin Kumar Yadav and Saurabh Suman . All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bueno, E.T.; Paris, J.M.; Clavier, K.A.; Spreadbury, C.; Ferraro, C.C.; Townsend, T.G. A review of ground waste glass as a supplementary cementitious material: A focus on alkali-silica reaction. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 257, 120180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalakada, Z.; Doh, J.; Zi, G. Utilisation of coarse glass powder as pozzolanic cement—A mix design investigation. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 240, 117916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, Y.; Hogland, W. Waste glass in the production of cement and concrete–A review. Journal of environmental chemical engineering 2014, 2, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstic, M.; Davalos, J. Field Application of Recycled Glass Pozzolan for Concrete. ACI Materials Journal 2019, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gong, X.Z.; Cui, S.P.; Wang, Z.H.; Zheng, Y.; Chi, B.C. CO2 emissions due to cement manufacture. In Proceedings of the Materials Science Forum. Trans Tech Publ, 2011, Vol. 685, pp. 181–187.

- Huntzinger, D.N.; Eatmon, T.D. A life-cycle assessment of Portland cement manufacturing: comparing the traditional process with alternative technologies. Journal of cleaner production 2009, 17, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Martinez-Garcia, R.; Algarni, S.; de Prado-Gil, J.; Alqahtani, T.; Irshad, K. Characteristics of sustainable concrete with partial substitutions of glass waste as a binder material. International Journal of Concrete Structures and Materials 2022, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department, S.R. Major countries in worldwide cement production in 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/267364/world-cement-production-by-country/, 2023.

- EPA. Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: 2018 Fact Sheet. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-11/documents/2018_ff_fact_sheet.pdf.

- Adesina, A.; Das, S. Influence of glass powder on the durability properties of engineered cementitious composites. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 242, 118199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasaniya, M.; Thomas, M.D.; Moffatt, E.G. Pozzolanic reactivity of natural pozzolans, ground glasses and coal bottom ashes and implication of their incorporation on the chloride permeability of concrete. Cement and Concrete Research 2021, 139, 106259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, R.U.D.; Soroushian, P. Strength and durability of recycled aggregate concrete containing milled glass as partial replacement for cement. Construction and Building Materials 2012, 29, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Vajna, J.; Cheung, T.H.H.; Kurmus, H.; Arulrajah, A.; Horpibulsuk, S. Practical recycling applications of crushed waste glass in construction materials: A review. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 156, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Zhou, Z.; Usanova, K.I.; Vatin, N.I.; El-Shorbagy, M.A. A step towards concrete with partial substitution of waste glass (WG) in concrete: a review. Materials 2022, 15, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, A.M.; Sousa-Coutinho, J. Durability of mortar using waste glass powder as cement replacement. Construction and building materials 2012, 36, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, A.S.; Anand, K.; Rakesh, P. Partial replacement of Ordinary Portland cement by LCD glass powder in concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 46, 5131–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, B.; Nounu, G. Properties of concrete contains mixed colour waste recycled glass as sand and cement replacement. Construction and Building Materials 2008, 22, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, A.; Xu, A. Performance of glass powder as a pozzolanic material in concrete: A field trial on concrete slabs. Cement and concrete research 2006, 36, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, A.; Xu, A. Value-added utilisation of waste glass in concrete. Cement and concrete research 2004, 34, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidol, A.; Tognonvi, M.T.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Effect of glass powder on concrete sustainability. New Journal of Glass and Ceramics 2017, 7, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idir, R.; Cyr, M.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Pozzolanic properties of fine and coarse color-mixed glass cullet. Cement and Concrete Composites 2011, 33, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idir, R.; Cyr, M.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Use of waste glass in cement-based materials. Environnement, Ingénierie & Développement 2010, p. 10.

- Lu, J.x.; Duan, Z.h.; Poon, C.S. Fresh properties of cement pastes or mortars incorporating waste glass powder and cullet. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 131, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Cam, H.; Neithalath, N. Influence of a fine glass powder on the durability characteristics of concrete and its comparison to fly ash. Cement and Concrete composites 2008, 30, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidian-Dezfouli, H.; Afshinnia, K.; Rangaraju, P.R. Efficiency of Ground Glass Fiber as a cementitious material, in mitigation of alkali-silica reaction of glass aggregates in mortars and concrete. Journal of Building Engineering 2018, 15, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, A.F.; Etienne, D.; Harbec, D.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; et al. Long-term performance of glass-powder concrete in large-scale field applications. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 135, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigione, G.; Marra, S. Relationship between particle size distribution and compressive strength in Portland cement. Cement and concrete research 1976, 6, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Hanif, A.; Usman, M.; Sim, J.; Oh, H. Performance evaluation of concrete incorporating glass powder and glass sludge wastes as supplementary cementing material. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 170, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A. The influence of waste glass powder as a pozzolanic material in concrete. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol 2016, 7, 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sahmenko, G.; Korjakins, A.; et al. Bore-silicate glass waste of lamp as a micro-filler for concrete. Rigas Tehniskas Universitates Zinatniskie Raksti 2009, 10, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke, K.; Adedeji, A. A review on the properties of concrete incorporated with waste glass as a substitute for cement. Epistem. Sci. Eng. Technol 2016, 5, 396–407. [Google Scholar]

- Rahma, A.; El Naber, N.; Issa Ismail, S. Effect of glass powder on the compression strength and the workability of concrete. Cogent Engineering 2017, 4, 1373415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmiri, A.; Samet, B.; Chaabouni, M. A cross mixture design to optimise the formulation of a ground waste glass blended cement. Construction and Building Materials 2012, 28, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodehi, M.; Ren, J.; Shi, X.; Debbarma, S.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Experimental evaluation of alkali-activated and portland cement-based mortars prepared using waste glass powder in replacement of fly ash. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 394, 132124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guignone, G.; Calmon, J.L.; Vieira, G.; Zulcão, R.; Rebello, T.A. Life cycle assessment of waste glass powder incorporation on concrete: a bridge retrofit study case. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremichael, N.N.; Jadidi, K.; Karakouzian, M. Waste glass recycling: The combined effect of particle size and proportion in concrete manufactured with waste recycled glass. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 392, 132044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard Terminology Relating to Concrete and Concrete Aggregates. Standard, American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA, 2019.

- Kasaniya, M. Pozzolans: Reactivity test method development and durability performance. PhD thesis, The University of New Brunswick, 2014.

- Massazza, F. Pozzolana and pozzolanic cements.; In Lea’s Chemistry of Cement and Concrete (Ed. P.C. Hewlett), 1998; chapter Chapter 10, pp. 471–631.

- Kasaniya, M.; Thomas, M.D. Role of the alkalis of supplementary cementing materials in controlling pore solution chemistry and alkali-silica reaction. Cement and Concrete Research 2022, 162, 107007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, Y.; Saeki, T.; Saito, T. Relation between chemical composition and physical properties of CSH generated from cementitious materials. Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology 2015, 13, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; Kasaniya, M.; Tuen, M.; Thomas, M.D.; Suraneni, P. Linking reactivity test outputs to properties of cementitious pastes made with supplementary cementitious materials. Cement and Concrete Composites 2020, 114, 103742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Duitama, J.A.; Rojas-Avellaneda, D. Pozzolans: A review. Engineering and Applied Science Research 2022, 49, 495–504. [Google Scholar]

- Burhan, L.; Ghafor, K.; Mohammed, A. Modeling the effect of silica fume on the compressive, tensile strengths and durability of NSC and HSC in various strength ranges. Journal of Building Pathology and Rehabilitation 2019, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.M.; Abed, F.; Katman, H.Y.B.; Humada, A.M.; Al Jawahery, M.S.; Majdi, A.; Yousif, S.T.; Thomas, B.S. Effect of silica fume on the properties of sustainable cement concrete. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 24, 8887–8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Y. Effective utilization of waste glass as cementitious powder and construction sand in mortar. Materials 2020, 13, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Meng, W.; Khayat, K.H.; Bao, Y.; Guo, P.; Lyu, Z.; Abu-Obeidah, A.; Nassif, H.; Wang, H. New development of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Composites Part B: Engineering 2021, 224, 109220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Lefort, T.; Moras, S.; Rodriguez, D. Studies on concrete containing ground waste glass. Cement and concrete research 2000, 30, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzahosseini, M.; Riding, K.A. Effect of curing temperature and glass type on the pozzolanic reactivity of glass powder. Cement and Concrete Research 2014, 58, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraghechi, H.; Maraghechi, M.; Rajabipour, F.; Pantano, C.G. Pozzolanic reactivity of recycled glass powder at elevated temperatures: Reaction stoichiometry, reaction products and effect of alkali activation. Cement and Concrete Composites 2014, 53, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkevičius, V.; Šerelis, E.; Hilbig, H. The effect of glass powder on the microstructure of ultra high performance concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2014, 68, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tural, H.; Ozarisoy, B.; Derogar, S.; Ince, C. Investigating the governing factors influencing the pozzolanic activity through a database approach for the development of sustainable cementitious materials. Construction and Building Materials 2024, 411, 134253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zier, M.; Stenzel, P.; Kotzur, L.; Stolten, D. A review of decarbonization options for the glass industry. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2021, 10, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, A.; Krstic, M.; Rangaraju, P.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Thomas, M.D. Ground-glass pozzolan for use in concrete. Concr. Int 2020, 42, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.; Meng, W.; Nassif, H.; Gou, H.; Bao, Y. New perspectives on recycling waste glass in manufacturing concrete for sustainable civil infrastructure. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 257, 119579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, B.; Krishna, G.G.; Saraswathy, V.; Srinivasan, K. Experimental investigation on concrete partially replaced with waste glass powder and waste E-plastic. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 278, 122400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Qiao, H.; Li, A.; Li, G. Performance of waste glass powder as a pozzolanic material in blended cement mortar. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 324, 126531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, M.U.; Dymond, B.Z. Effect of composition on performance of ground glass pozzolan. ACI Materials Journal 2019, 116, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Huang, R.; Wu, J.; Yang, C.C. Waste E-glass particles used in cementitious mixtures. Cement and concrete Research 2006, 36, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Matinlinna, J.P. E-glass fiber reinforced composites in dental applications. Silicon 2012, 4, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karazi, S.; Ahad, I.; Benyounis, K. Laser Micromachining for Transparent Materials. In Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering; Elsevier, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Standard Specification for Ground-Glass Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. Standard, American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA, 2020.

- Abdulazeez, A.S.; Idi, M.A.; Kolawole, M.A.; Hamza, B. Effect of waste glass powder as a pozzolanic material in concrete production. Int. J. Eng. Res 2020, 9, 589–594. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, K. Recycled waste glass powder as a partial replacement of cement in concrete containing silica fume and fly ash. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2021, 15, e00630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattouh, M.S.; Elsayed, E.K. Influence of utilizing glass powder with silica fume on mechanical properties and microstructure of concrete. Delta University Scientific Journal 2023, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Shahzada, K.; Ullah, Q.S.; Fahim, M.; Khan, S.W.; Badrashi, Y.I. Development of environment-friendly concrete through partial addition of waste glass powder (WGP) as cement replacement. Civil Engineering Journal 2020, 6, 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ani, F.M.; Hossain, M.A.; Shahril, R.N. Recycling of Glass Waste on the Concrete Properties as a Partial Binding Material Substitute. European Journal of Engineering and Technology Research 2022, 7, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeeduddin, M.S.; Chavan, M.F. Use of waste glass powder as a partial replacement of cement in fibre reinforced concrete. IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE) e-ISSN 2016, pp. 2278–1684.

- Gupta, J.; Jethoo, A.; Lata, N. Assessment of mechanical properties by using powder waste glass with cement in concrete mix. In Proceedings of the IOP conference series: materials science and engineering. IOP Publishing, 2020, Vol. 872, p. 012122.

- Ahmad, J.; Martínez-García, R.; de Prado-Gil, J.; Irshad, K.; El-Shorbagy, M.A.; Fediuk, R.; Vatin, N.I. Concrete with partial substitution of waste glass and recycled concrete aggregate. Materials 2022, 15, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanna, N.; Tuladhar, R. Sustainable use of recycled glass powder as cement replacement in concrete. The Open Waste Management Journal 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, D.; Akbulut, Z.F.; Guler, S. An experimental investigation of hydraulic and early and later-age mechanical properties of eco-friendly porous concrete containing waste glass powder and fly ash. Construction and Building Materials 2024, 418, 135312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xiao, R.; Bai, Y.; Huang, B.; Ma, Y. Influence of waste glass powder as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) on physical and mechanical properties of cement paste under high temperatures. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 340, 130778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabdo, A.A.; Abd Elmoaty, M.; Aboshama, A.Y. Utilization of waste glass powder in the production of cement and concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 124, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanapornprom, R.; Stitmannaithum, B. Comparison of properties of fresh and hardened concrete containing finely ground glass powder, fly ash, or silica fume. Engineering Journal 2015, 19, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhedin, D.A.; Ibrahim, R.K. Effect of waste glass powder as partial replacement of cement & sand in concrete. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2023, 19, e02512. [Google Scholar]

- Barkauskas, K.; Nagrockienė, D.; Norkus, A. The effect of ground glass waste on properties of hardened cement paste and mortar. Ceramics-Silikaty 2020, 64, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letelier, V.; Henríquez-Jara, B.I.; Manosalva, M.; Parodi, C.; Ortega, J.M. Use of waste glass as a replacement for raw materials in mortars with a lower environmental impact. Energies 2019, 12, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanna, N.; Sutan, N.M.; Yakub, I.; Lee, D. Strength Characteristics of Mortar Containing Different Sizes Glass Powder. Journal of Civil Engineering, Science and Technology 2014, 5, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, S.; Poudel, S.; Thomas, R.J. Performance of Concrete with Ground Glass Pozzolan as Partial Cement Replacement.

- Islam, G.S.; Rahman, M.; Kazi, N. Waste glass powder as partial replacement of cement for sustainable concrete practice. International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment 2017, 6, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yi, C.; Zi, G. Waste glass sludge as a partial cement replacement in mortar. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 75, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, B.; Senatsi, K.; Abdulwahab, R.; Nkala, M. Effects of Waste Glass Powder as Partial Replacement of Cement on the Structural Performance of Concrete 2024.

- Qasem, O.A.M.A. The Utilization Of Glass Powder As Partial Replacement Material For The Mechanical Properties Of Concrete. PhD thesis, Universitas Islam Indonesia, 2024.

- Herki, B.M. Strength and Absorption Study on Eco-Efficient Concrete Using Recycled Powders as Mineral Admixtures under Various Curing Conditions. Recycling 2024, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baikerikar, A.; Mudalgi, S.; Ram, V.V. Utilization of waste glass powder and waste glass sand in the production of Eco-Friendly concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 377, 131078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Meng, X.; Wang, B.; Tong, Q. Experimental Study on Long-Term Mechanical Properties and Durability of Waste Glass Added to OPC Concrete. Materials 2023, 16, 5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaamandadin, N.A.; Abdul Aziz, I.S.; Mustafa, W.A.; Santiagoo, R. Mechanical properties of the utilisation glass powder as partial replacement of cement in concrete. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Manufacturing and Mechatronics: Proceedings of the 2nd Symposium on Intelligent Manufacturing and Mechatronics–SympoSIMM 2019, 8 July 2019, Melaka, Malaysia. Springer, 2020, pp. 221–229.

- Moreira, O.; Camões, A.; Malheiro, R.; Jesus, C. High Glass Waste Incorporation towards Sustainable High-Performance Concrete. CivilEng 2024, 5, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.; Bindhu, K.; Matos, A.M.; Delgado, J. Eco-friendly concrete with waste glass powder: A sustainable and circular solution. Construction and building materials 2022, 355, 129217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, D.; Liang, Y. Influence of Ultra Fine Glass Powder on the Properties and Microstructure of Mortars. Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2024, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Standard Test Methods for Sampling and Testing Fly Ash or Natural Pozzolans for Use in Portland-Cement Concrete1. Standard, American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA, 2022.

- Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. Standard, American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA, 2023.

- Afshinnia, K.; Rangaraju, P.R. Influence of fineness of ground recycled glass on mitigation of alkali–silica reaction in mortars. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 81, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wu, Y.; Riefler, C.; Wang, H. Characteristics and pozzolanic reactivity of glass powders. Cement and Concrete Research 2005, 35, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Shrivastava, R.; Tiwari, R.; Yadav, R. Properties of cement mortar in substitution with waste fine glass powder and environmental impact study. Journal of Building Engineering 2020, 27, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Qiao, H.; Li, Q.; Hakuzweyezu, T.; Chen, B. Study on the performance of pervious concrete mixed with waste glass powder. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 300, 123997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).