Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. ILC3s and ILC3s Glycolysis

2.1. Introduction to ILC3s

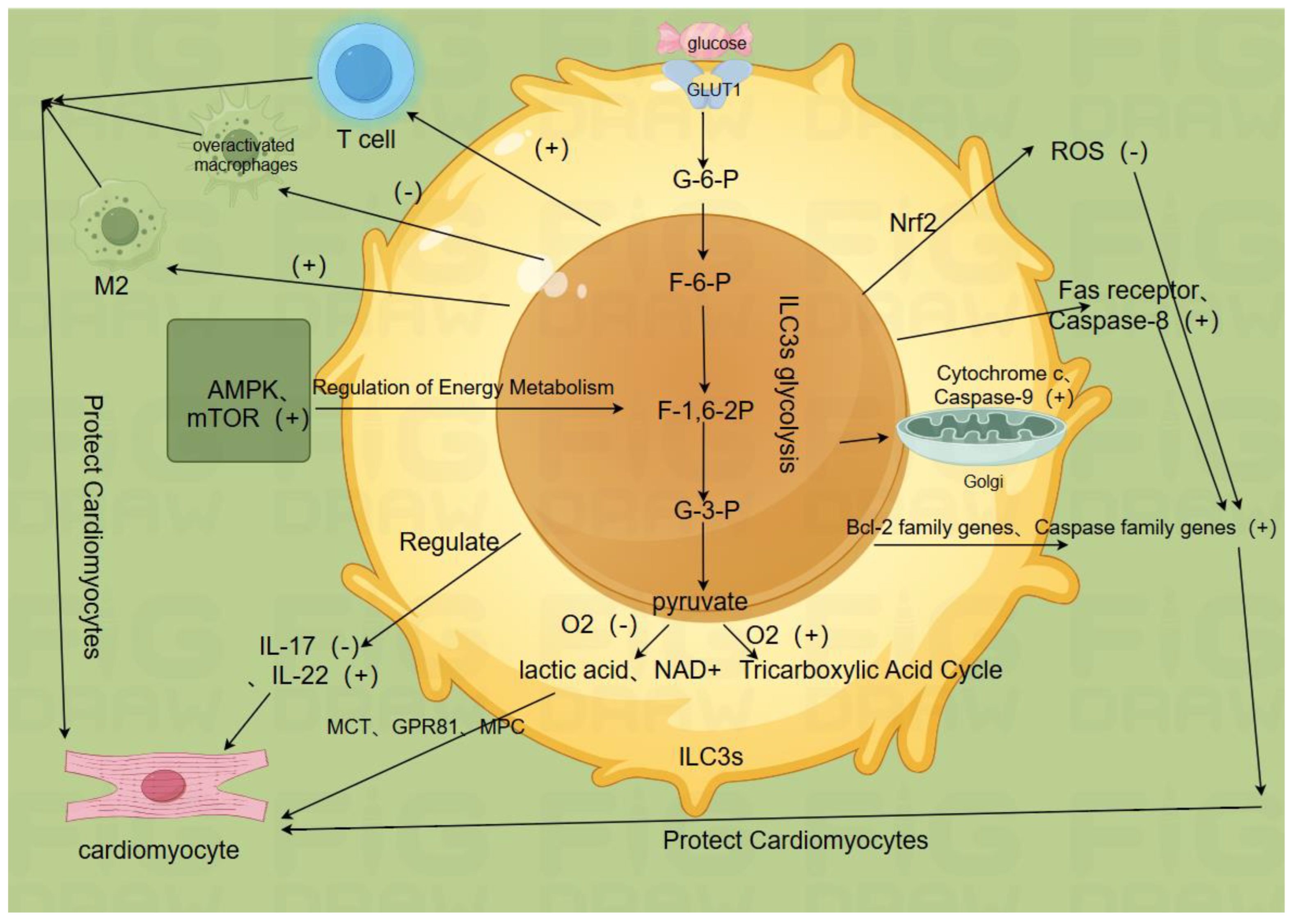

2.2. ILC3s Glycolysis is Key to ILC3s Function(Figure b)

2.2.1. Glucose Uptake and Metabolic Pathways

2.2.2. Cytokine Secretion and Metabolic Product Signaling

2.2.3. Synergistic Effects of Cardiomyocyte Protection and Immune Regulation

2.2.4. Antioxidant Enzyme and Reactive Oxygen Species Regulation

2.2.5. Regulation of Apoptosis Signaling Pathways

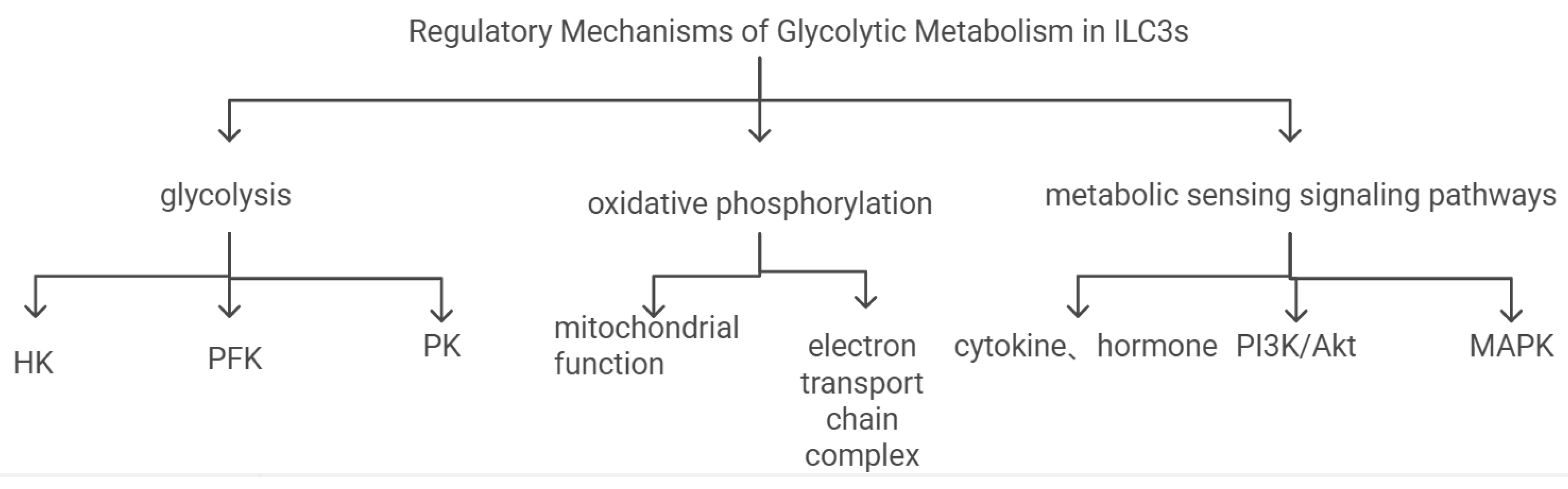

2.3. Regulation Mechanisms of ILC3s Glycolysis

3. Multiple Regulatory Mechanisms of ILC3s Glycolysis in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

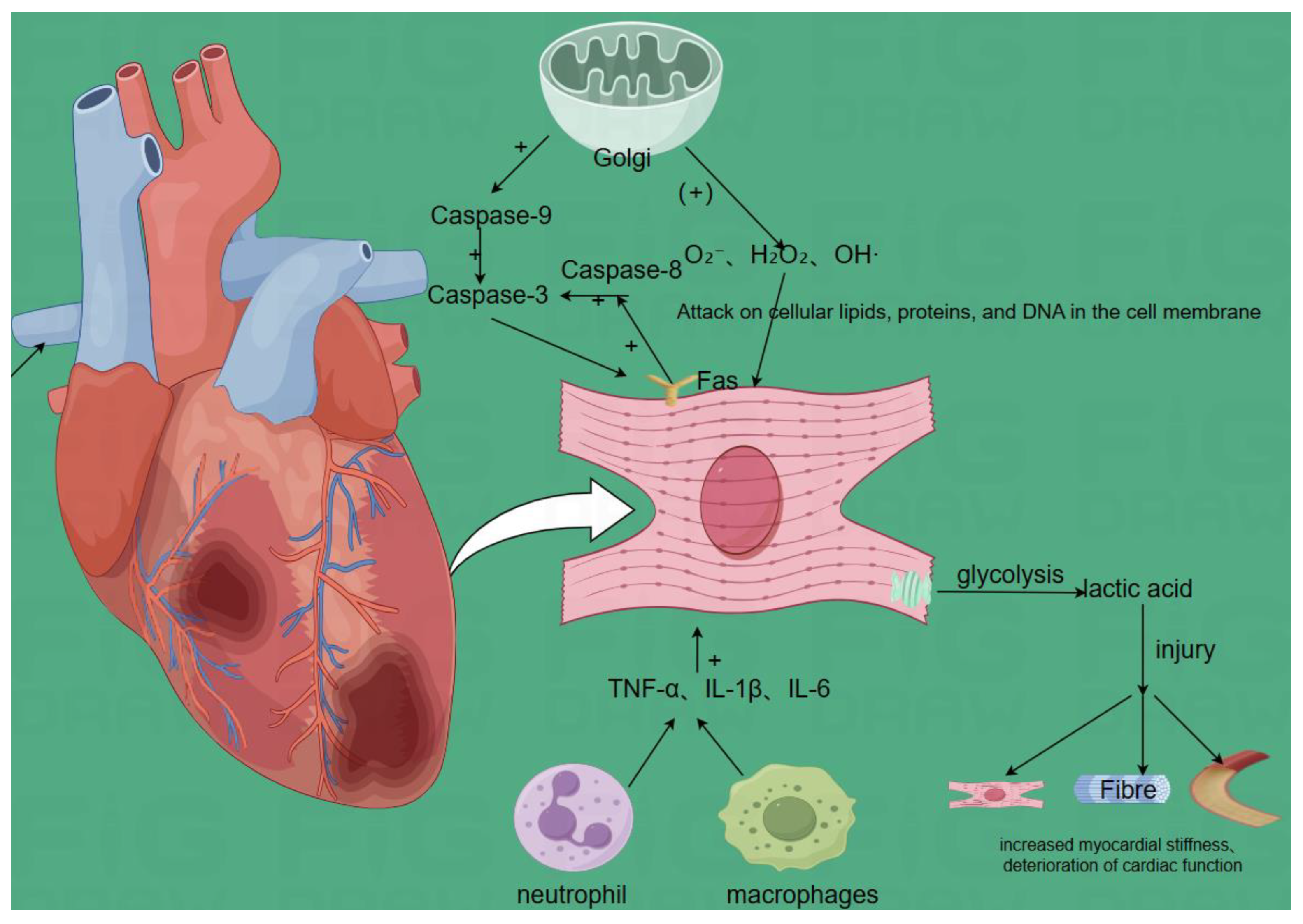

3.1. Pathophysiology of Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury(Figure d)

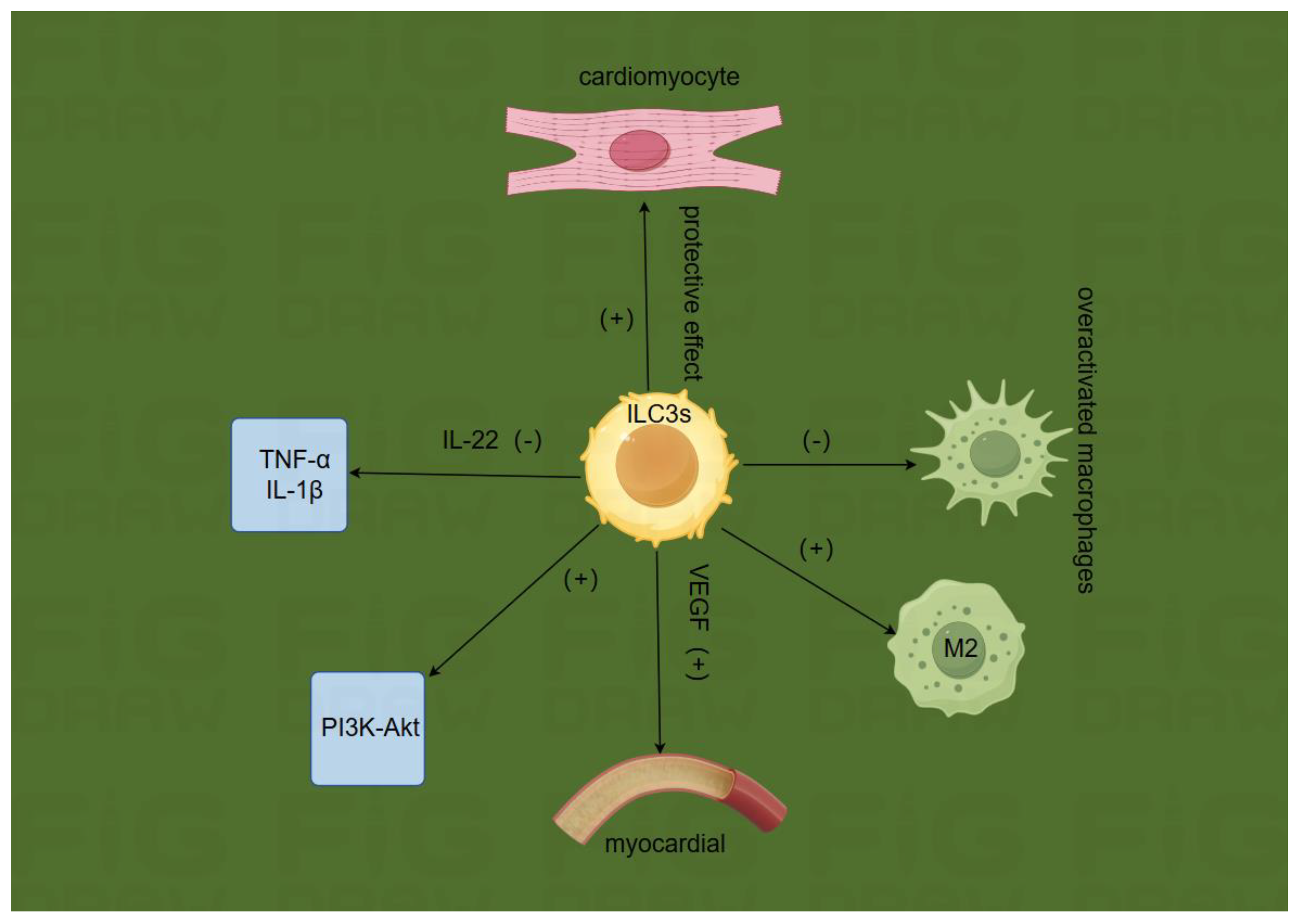

3.2. Effects of ILC3s Glycolysis on Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

3.2.1. Glucose Uptake and Metabolic Pathways

3.2.2. Metabolic Sensing Molecules and Signal Transduction

3.2.3. Cytokine Secretion and Metabolic Product Signaling

3.2.4. Immune Regulation and Antioxidant Effects

3.2.5. Regulation of Apoptosis Signaling Pathways

4. Potential Applications of ILC3s Glycolysis in MIRI Treatment

4.1. Key Enzymes, Metabolic Sensing Molecules, and Signal Pathways in ILC3s Glycolysis Pathway

4.1.1. Hexokinase, Phosphofructokinase, and Pyruvate Kinase

4.1.2. AMPK and mTOR

4.1.3. PI3K/Akt, JAK2/STAT3, and Nrf2/HO-1 Pathways

4.2. Cardiomyocytes and Vasculature in ILC3s Glycolysis Pathway

4.2.1. Cardiomyocyte Proliferation

4.2.2. Angiogenesis

4.3. Combined Applications of ILC3s Glycolysis in MIRI Treatment

4.3.1. Combination of ILC3s Glycolysis with Drug Therapy in MIRI Treatment

4.3.2. Combination of ILC3s Glycolysis with Ischemic Preconditioning and Postconditioning in MIRI Treatment

4.3.3. Combination of ILC3s Glycolysis with Stem Cell Therapy in MIRI Treatment

4.4. Clinical Detection and Individualized Adjustment Strategies for ILC3s Glycolysis in MIRI Treatment

4.4.1. Clinical Detection

4.4.2. Clinical Adjustment

4.4.3. Treatment Plan Adjustment Strategies

4.4.4. Monitoring and Feedback

5. Conclusion

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form |

| AIF | apoptosis-inducing factor |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AICAR | 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| CPB-CABG | Cardiopulmonary Bypass - Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting |

| Cyt c | cytochrome c |

| DEHP | di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EndoG | endonuclease G |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| FasL | Fas ligand |

| G-3-P | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate |

| GPR81 | G Protein-Coupled Receptor 81 |

| GLUT1 | glucose transporter 1 |

| HK | hexokinase |

| ILC3s | Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-17 | interleukin-17 |

| IL-22 | interleukin-22 |

| IPostC | ischemic postconditioning |

| IPC | Ischemic preconditioning |

| IRE1 | inositol-requiring enzyme 1 |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| MCT | monocarboxylate transporters |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MVD | microvascular density |

| MDH2 | malate dehydrogenase 2 |

| MPTP | mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| NAD+ | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| NOX | NADPH oxidase |

| OP-CABG | Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting |

| PDK4 | pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 |

| PD-1 | programmed cell death 1 |

| PFK | phosphofructokinase |

| PIP2 | phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate |

| PK | pyruvate kinase |

| PTP | permeability transition pores |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RORγt | retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor gamma |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| STAT3 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| Zbtb46 | zinc finger and BTB domain-containing protein 46 |

| 2-DG | 2-deoxy-D-glucose |

References

- Zhang, S.; Yan, F.; Luan, F.; Chai, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.-W.; Chen, Z.-L.; Xu, D.-Q.; Tang, Y.-P. The pathological mechanisms and potential therapeutic drugs for myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, M.; Lu, Y.; Xin, L.; Gao, J.; Shang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Lin, H.; Fang, X.; Qu, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Role of Oxidative Stress in Reperfusion following Myocardial Ischemia and Its Treatments. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6614009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Q.; Yi, X.; Zhu, X.-H.; Wei, X.; Jiang, D.-S. Regulated cell death in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 2024, 35, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, C.; Serafin, A.; Schwerdt, O.M.; Fischer, J.; Sicklinger, F.; Younesi, F.S.; Byrne, N.J.; Meyer, I.S.; Malovrh, E.; Sandmann, C.; et al. Transient Inhibition of Translation Improves Cardiac Function After Ischemia/Reperfusion by Attenuating the Inflammatory Response. Circulation 2024, 150, 1248–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.-E.; Yu, P.; Hu, Y.; Wan, W.; Shen, K.; Cui, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Cui, C.; Chatterjee, E.; et al. Exercise training decreases lactylation and prevents myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting YTHDF2. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2024, 119, 651–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumpper-Fedus, K.; Park, K.H.; Ma, H.; Zhou, X.; Bian, Z.; Krishnamurthy, K.; Sermersheim, M.; Zhou, J.; Tan, T.; Li, L.; et al. MG53 preserves mitochondrial integrity of cardiomyocytes during ischemia reperfusion-induced oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2022, 54, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Yin, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, T.; Jiang, B.; Li, H. Trimetazidine attenuates Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced myocardial ferroptosis by modulating the Sirt3/Nrf2-GSH system and reducing Oxidative/Nitrative stress. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 229, 116479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Elmoselhi, A.B.; Hata, T.; Makino, N. Status of myocardial antioxidants in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 47, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, A.; Huang, Y.; Sun, H.; Guan, F.; Jiang, W. Tetrandrine downregulates TRPV2 expression to ameliorate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats via regulation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis, calcium homeostasis and mitochondrial function. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 964, 176246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Wang, Q.; Xue, F.-S.; Yuan, Y.-J.; Li, S.; Liu, J.-H.; Liao, X.; Zhang, Y.-M. Comparison of cardioprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of ischemia pre- and postconditioning in rats with myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. Inflamm. Res. 2011, 60, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azab, M.; Idiiatullina, E.; Safi, M.; Hezam, K. Enhancers of mesenchymal stem cell stemness and therapeutic potency. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Shi, W.; Sun, H.; Ji, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; Sheng, H.; Shu, J.; Zhou, L.; Cai, T.; et al. Activation of DR3 signaling causes loss of ILC3s and exacerbates intestinal inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, N.; Guo, X. The crosstalk between ILC3s and adaptive immunity in diseases. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 3965–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, M.O.; Spari, D.; Sànchez Taltavull, D.; Salm, L.; Yilmaz, B.; Doucet Ladevèze, R.; Mooser, C.; Pereyra, D.; Ouyang, Y.; Schmidt, T.; et al. ILC3s restrict the dissemination of intestinal bacteria to safeguard liver regeneration after surgery. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, J.; Chu, C.; Zhang, C.; Sockolow, R.E.; Eberl, G.; Sonnenberg, G.F. Zbtb46 defines and regulates ILC3s that protect the intestine. Nature 2022, 609, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Shen, X.; Liu, K.; Lu, C.; Fan, Y.; Xu, Q.; Meng, X.; Hong, S.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. The Transcription Factor ThPOK Regulates ILC3 Lineage Homeostasis and Function During Intestinal Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Transcription Factor RORα Preserves ILC3 Lineage Identity and Function during Chronic Intestinal Infection | The Journal of Immunology | American Association of Immunologists. Available online: https://journals.aai.org/jimmunol/article/203/12/3209/110026/The-Transcription-Factor-ROR-Preserves-ILC3 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- CCR6+ group 3 innate lymphoid cells accumulate in inflamed joints in rheumatoid arthritis and produce Th17 cytokines | Arthritis Research & Therapy | Full Text. Available online: https://arthritis-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13075-019-1984-x?utm_source=xmol&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_content=meta&utm_campaign=DDCN_1_GL01_metadata (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Role of Nutrient-sensing Receptor GPRC6A in Regulating Colonic Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells and Inflamed Mucosal Healing | Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis | Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/16/8/1293/6521543 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Vitamin D downregulates the IL-23 receptor pathway in human mucosal group 3 innate lymphoid cells - ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0091674917306577 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Activation of DR3 signaling causes loss of ILC3s and exacerbates intestinal inflammation | Nature Communications. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-11304-8?utm_source=xmol&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_content=meta&utm_campaign=DDCN_1_GL01_metadata (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Musculin is highly enriched in Th17 and IL-22-producing ILC3s and restrains pro-inflammatory cytokines in murine colitis - Yan - 2021 - European Journal of Immunology - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/eji.202048573 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Wang, B.; Lim, J.-H.; Kajikawa, T.; Li, X.; Vallance, B.A.; Moutsopoulos, N.M.; Chavakis, T.; Hajishengallis, G. Macrophage β2-Integrins Regulate IL-22 by ILC3s and Protect from Lethal Citrobacter rodentium-Induced Colitis. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 1614–1626.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P5374Genetic deletion of IL-22 increased cardiac rupture after myocardial infarction in mice | European Heart Journal | Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article-abstract/40/Supplement_1/ehz746.0337/5597811?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Bresler, P.; Tejerina, E.; Jacob, J.M.; Legrand, A.; Quellec, V.; Ezine, S.; Peduto, L.; Cherrier, M. T cells regulate lymph node-resident ILC populations in a tissue and subset-specific way. iScience 2021, 24, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontiers | Biology of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor C in the Morphogenesis of Lymphatic Vessels. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/bioengineering-and-biotechnology/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2018.00007/full (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Burton, P.B.J.; Owen, V.J.; Hafizi, S.; Barton, P.J.R.; Carr-White, G.; Koh, T.; De Souza, A.; Yacoub, M.H.; Pepper, J.R. Vascular endothelial growth factor release following coronary artery bypass surgery: extracorporeal circulation versus ‘beating heart’ surgery. Eur. Heart J. 2000, 21, 1708–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxidative stress in myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury: a renewed focus on a long-standing area of heart research: Redox Report: Vol 10, No 4. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/135100005X57391 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Chinese Medical Journal. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/cmj/fulltext/2023/10200/senp2_mediated_serca2a_desumoylation_increases.12.aspx (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Xuan, X.; Zhou, J.; Tian, Z.; Lin, Y.; Song, J.; Ruan, Z.; Ni, B.; Zhao, H.; Yang, W. ILC3 cells promote the proliferation and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells through IL-22/AKT signaling. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 22, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, E.; Lavoie, S.; Fonseca-Pereira, D.; Bae, S.; Michaud, M.; Hoveyda, H.R.; Fraser, G.L.; Gallini Comeau, C.A.; Glickman, J.N.; Fuller, M.H.; et al. Metabolite-Sensing Receptor Ffar2 Regulates Colonic Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells and Gut Immunity. Immunity 2019, 51, 871–884.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepworth, M.R. Proline fuels ILC3s to maintain gut health. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 1848–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ILC3s integrate glycolysis and mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species to fulfill activation demands | Journal of Experimental Medicine | Rockefeller University Press. Available online: https://rupress.org/jem/article/216/10/2231/120535/ILC3s-integrate-glycolysis-and-mitochondrial (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Tan, C.Y.; Theriot, B.S.; Rao, M.V.; Surana, N.K. A commensal-derived exopolysaccharide regulates ILC3-mediated diseases. J. Immunol. 2023, 210, 227.04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montessuit, C.; Lerch, R. Regulation and dysregulation of glucose transport in cardiomyocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Res. 2013, 1833, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMPK: An Epigenetic Landscape Modulator. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/10/3238 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Sajiir, H.; Ramm, G.A.; Macdonald, G.A.; McGuckin, M.A.; Prins, J.B.; Hasnain, S.Z. Harnessing IL-22 for metabolic health: promise and pitfalls. Trends Mol. Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.-L.; Jiao, Y.-R.; Li, T.; Yao, H.-C. Inhibition of IL-17 might be a novel therapeutic target in the treatment of myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 239, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Tian, Y.; Chen, R.; Xia, L.; Liu, F.; Su, Z. IL-22 ameliorated cardiomyocyte apoptosis in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury by blocking mitochondrial membrane potential decrease, inhibiting ROS and cytochrome C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RORγt inhibitors block both IL-17 and IL-22 conferring a potential advantage over anti-IL-17 alone to treat severe asthma | Respiratory Research | Full Text. Available online: https://respiratory-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12931-021-01743-7?utm_source=xmol&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_content=meta&utm_campaign=DDCN_1_GL01_metadata (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Dexmedetomidine Ameliorates Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting MDH2 Lactylation via Regulating Metabolic Reprogramming - She - 2024 - Advanced Science - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://advanced.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/advs.202409499 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Jun, J.H.; Shim, J.-K.; Oh, J.E.; Shin, E.-J.; Shin, E.; Kwak, Y.-L. Protective Effect of Ethyl Pyruvate against Myocardial Ischemia Reperfusion Injury through Regulations of ROS-Related NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4264580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Martinez-Ruiz, G.U.; Bouladoux, N.; Stacy, A.; Moraly, J.; Vega-Sendino, M.; Zhao, Y.; Lavaert, M.; Ding, Y.; Morales-Sanchez, A.; et al. Transcription factor Tox2 is required for metabolic adaptation and tissue residency of ILC3 in the gut. Immunity 2024, 57, 1019–1036.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glucose metabolism and acute myocardial infarctionThe opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology. | European Heart Journal | Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article-abstract/27/11/1264/456905?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Liu, X.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Y.; Qi, C.; Xiong, T.; Wu, G.; Zeng, C.; Wang, D. DRD4 Mitigates Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Association With PI3K/AKT Mediated Glucose Metabolism. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Jia, T.; Feng, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, D. T Cell Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase in Glucose Metabolism. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JCI Insight - Glucose metabolism controls disease-specific signatures of macrophage effector functions. Available online: https://insight.jci.org/articles/view/123047 (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- A New Paradigm in Catalase Research - ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S096289242030252X (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Targeted delivery and ROS-responsive release of Resolvin D1 by platelet chimeric liposome ameliorates myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury | Journal of Nanobiotechnology | Full Text. Available online: https://jnanobiotechnology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12951-022-01652-x?utm_source=xmol&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_content=meta&utm_campaign=DDCN_1_GL01_metadata (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Li, X.; Jin, Y. Inhibition of miR-182-5p attenuates ROS and protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by targeting STK17A. Cell Cycle Georget. Tex 2022, 21, 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BCL2-regulated apoptotic process in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (Review). Available online: https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/ijmm.2020.4781 (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Liu, H.; Li, S.; Jiang, W.; Li, Y. MiR-484 Protects Rat Myocardial Cells from Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting Caspase-3 and Caspase-9 during Apoptosis. Korean Circ. J. 2020, 50, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Location matters: hexokinase 1 in glucose metabolism and inflammation - ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1043276022001400 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Fulghum, K.L.; Audam, T.N.; Lorkiewicz, P.K.; Zheng, Y.; Merchant, M.; Cummins, T.D.; Dean, W.L.; Cassel, T.A.; Fan, T.W.M.; Hill, B.G. In vivo deep network tracing reveals phosphofructokinase-mediated coordination of biosynthetic pathway activity in the myocardium. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2022, 162, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Jeon, J.-H.; Min, B.-K.; Ha, C.-M.; Thoudam, T.; Park, B.-Y.; Lee, I.-K. Role of the Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex in Metabolic Remodeling: Differential Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Functions in Metabolism. Diabetes Metab. J. 2018, 42, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Li, H.; Wang, M.; Chu, E.; Wei, N.; Lin, J.; Hu, Y.; Dai, J.; Chen, A.; Zheng, H.; et al. mTOR participates in the formation, maintenance, and function of memory CD8+T cells regulated by glycometabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 204, 115197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, M.; Li, L.; Deng, J.; Wang, X.; Su, J.; Zhu, Y.; He, F.; Mao, J.; et al. Ginsenoside Rg3 ameliorates myocardial glucose metabolism and insulin resistance via activating the AMPK signaling pathway. J. Ginseng Res. 2022, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coupling of GABA Metabolism to Mitochondrial Glucose Phosphorylation | Neurochemical Research. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11064-021-03463-2?utm_source=xmol&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_content=meta&utm_campaign=DDCN_1_GL01_metadata (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Cai, J.; Shi, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, Q.; Gong, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhang, Z. Taxifolin ameliorates DEHP-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy via attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction and glycometabolism disorder in chicken. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wende, A.R.; Schell, J.C.; Ha, C.-M.; Pepin, M.E.; Khalimonchuk, O.; Schwertz, H.; Pereira, R.O.; Brahma, M.K.; Tuinei, J.; Contreras-Ferrat, A.; et al. Maintaining Myocardial Glucose Utilization in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy Accelerates Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Diabetes 2020, 69, 2094–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliati, S.; Cabrera-Alarcón, J.L.; Enriquez, J.A. Regulation and functional role of the electron transport chain supercomplexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 2655–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oherle, K.; Acker, E.; Bonfield, M.; Wang, T.; Gray, J.; Lang, I.; Bridges, J.; Lewkowich, I.; Xu, Y.; Ahlfeld, S.; et al. Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Supports a Pulmonary Niche that Promotes Type 3 Innate Lymphoid Cell Development in Newborn Lungs. Immunity 2020, 52, 275–294.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennicke, C.; Cochemé, H.M. Redox regulation of the insulin signalling pathway胰岛素信号通路的氧化还原调节. Redox Biol. 2021, 42, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.S.; Jun, H.-S. Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 on Oxidative Stress and Nrf2 Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desideri, E.; Vegliante, R.; Cardaci, S.; Nepravishta, R.; Paci, M.; Ciriolo, M.R. MAPK14/p38α-dependent modulation of glucose metabolism affects ROS levels and autophagy during starvation. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1652–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, P.; Lai, C.J.; Lin, C.-Y.; Liou, Y.-F.; Huang, C.-Y.; Lee, S.-D. Effect of superoxide anion scavenger on rat hearts with chronic intermittent hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 120, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.; Park, M.; Kang, C.; Dilmen, S.; Kang, T.H.; Kang, D.G.; Ke, Q.; Lee, S.U.; Lee, D.; Kang, P.M. Hydrogen Peroxide-Responsive Nanoparticle Reduces Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.G.; Fearnhead, H.O. Apocytochrome c blocks caspase-9 activation and Bax-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 50834–50841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Borné, Y.; Mattisson, I.Y.; Wigren, M.; Melander, O.; Ohro-Melander, M.; Bengtsson, E.; Fredrikson, G.N.; Nilsson, J.; Engström, G. FADD, Caspase-3, and Caspase-8 and Incidence of Coronary Events. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Li, M.; Hu, D.; Li, J. Recent advances in potential targets for myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury: Role of macrophages. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 169, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- role of neutrophils in myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury | Cardiovascular Research | Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/cardiovascres/article-abstract/43/4/860/340838?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Tian, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Z. Abnormalities of glucose and lipid metabolism in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, M.E.; Li, S.; Trouten, A.M.; Stairley, R.A.; Roddy, P.L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Sucov, H.M.; Tao, G. Cardiomyocyte-fibroblast interaction regulates ferroptosis and fibrosis after myocardial injury. iScience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharmacological inhibition of GLUT1 as a new immunotherapeutic approach after myocardial infarction - ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006295221002033 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Bin, J.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G.; Zheng, H. ENHANCED GLYCOLYSIS PROMOTES POSTNATAL CARDIOMYOCYTE PROLIFERATION AND IMPROVES CARDIAC FUNCTION. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yang, J.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Hong, L.; Yuan, D.; Xia, R.; Liu, Y.; Pan, J.; et al. Nucleophosmin 1 promotes mucosal immunity by supporting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and ILC3 activity. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 1565–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedriali, G.; Ramaccini, D.; Bouhamida, E.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Giorgi, C.; Tremoli, E.; Pinton, P. Perspectives on mitochondrial relevance in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relaxin activates AMPK-AKT signaling and increases glucose uptake by cultured cardiomyocytes | Endocrine. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12020-018-1534-3?utm_source=xmol&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_content=meta&utm_campaign=DDCN_1_GL01_metadata (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- mTOR signaling mediates ILC3-driven immunopathology | Mucosal Immunology. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41385-021-00432-4?utm_source=xmol&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_content=meta&utm_campaign=DDCN_1_GL01_metadata (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Lin, B.; Ma, M.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. GPR34-mediated sensing of lysophosphatidylserine released by apoptotic neutrophils activates type 3 innate lymphoid cells to mediate tissue repair. Immunity 2021, 54, 1123–1136.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Li, F.; Chen, S.; Han, X.; Zheng, R.; Hu, X.; Lin, R.; Pei, Q.; et al. Intestinal CXCR6+ ILC3s migrate to the kidney and exacerbate renal fibrosis via IL-23 receptor signaling enhanced by PD-1 expression. Immunity 2024, 57, 1306–1323.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.-M.; Hu, Y.-Y.; Yang, T.; Wu, N.; Wang, X.-N. Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress in Vascular-Related Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 7906091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Chen, L.; Li, G.; Lei, W.; Zhao, J.; Liao, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, M. Sodium Lactate Accelerates M2 Macrophage Polarization and Improves Cardiac Function after Myocardial Infarction in Mice. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2021, 2021, 5530541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksida, T.; Paunović, V.; Koprivica, I.; Mićanović, D.; Jevtić, B.; Jonić, N.; Stojanović, I.; Pejnović, N. Development of Type 1 Diabetes in Mice Is Associated with a Decrease in IL-2-Producing ILC3 and FoxP3+ Treg in the Small Intestine. Molecules 2023, 28, 3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Guan, X.; Qian, H.; Wang, L.; Shen, Z.; Fang, L.; Liu, Z. Restoration of NRF2 attenuates myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury through mediating microRNA-29a-3p/CCNT2 axis. BioFactors Oxf. Engl. 2021, 47, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terse, P.; Joshi, P.; Bordelon, N.; Brys, A.; Patton, K.; Arndt, T.; Sutula, T. 2-Deoxy–D-Glucose (2-DG) Induced Cardiac Toxicity in Rat: NT- proBNP and BNP as Potential Early Cardiac Safety Biomarkers. Int. J. Toxicol. 2016, 35, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Li, C.; Zhu, Y.; Song, Y.; Lu, S.; Sun, H.; Hao, H.; Xu, X. TEPP-46-Based AIE Fluorescent Probe for Detection and Bioimaging of PKM2 in Living Cells. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 12682–12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choksey, A.; Carter, R.D.; Thackray, B.D.; Ball, V.; Kennedy, B.W.C.; Ha, L.H.T.; Sharma, E.; Broxholme, J.; Castro-Guarda, M.; Murphy, M.P.; et al. AICAR confers prophylactic cardioprotection in doxorubicin-induced heart failure in rats. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2024, 191, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The mystery of metformin.,Journal of Biological Chemistry - X-MOL. Available online: https://www.x-mol.com/paper/5659876?adv (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- VEGF-A in Cardiomyocytes and Heart Diseases. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/15/5294 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- The Clinical Efficacy of N-Acetylcysteine in the Treatment of ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ihj/62/1/62_20-519/_article/-char/en (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Talabieke, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, M. Abstract 424: Arachidonic Acid Synergizes With Aspirin In Cardioprotection Following Acute Myocardial Infarction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, A424–A424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Ischaemic preconditioning-induced serum exosomes protect against myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2021, 39, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalpol Promotes the Survival and VEGF Secretion of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells and Their Role in Myocardial Repair After Myocardial Infarction in Rats | Cardiovascular Toxicology. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12012-018-9460-4?utm_source=xmol&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_content=meta&utm_campaign=DDCN_1_GL01_metadata (accessed on 24 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).