Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

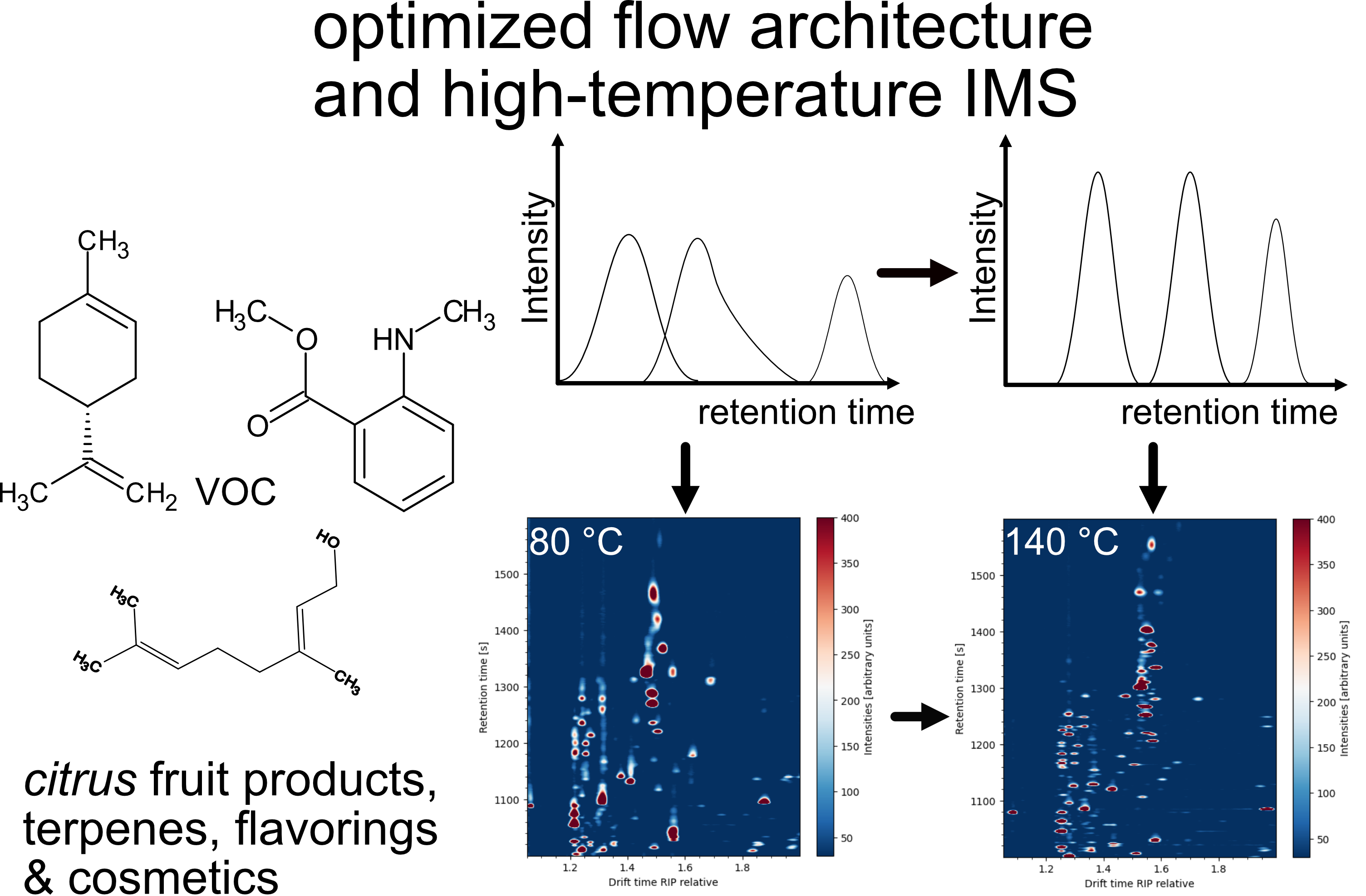

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Reagents and Samples

| Compound |

Molar Mass [g/mol] |

Boiling point [°C] |

Structure | Appearance |

| Ethyl butyrate (CAS: 105-54-4) | 116.16 | 120 - 121 |  |

Sweet oranges (C. sinensis (L.) Osbeck), mandarins (C. reticulata) |

| Sabinene (CAS: 3387-41-5) | 136.23 | 163 - 164 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| β – Pinene (CAS: 18172-67-3) | 136.23 | 166 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| (R)-(+)-Limonene (CAS: 5989-27-5) | 136.23 | 177 - 178 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| γ – Terpinene (CAS: 99-85-4) | 136.24 | 182 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| α – Terpineol (CAS: 98-55-5) | 154.25 | 217 - 219 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| (S)-(+)-Carvone (CAS: 2244-16-8) | 150,22 | 230 - 231 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| Geraniol (CAS: 106-24-1) | 154.25 | 229 - 230 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| Geranyl acetate (CAS: 105-87-3) | 196,29 | 138 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| Citronellol (CAS: 106-22-9) | 156,27 | 225 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| Citral (CAS: 5392-40-5) | 152.23 | 227 - 229 |  |

All Citrus fruits |

| Methyl-N-Methylanthranilate (CAS: 85-91-6) |

165.19 | 255 |  |

Mandarins (C. reticulata) |

| β-Caryophyllene (CAS: 87-44-5) | 204,35 | 256 - 259 |  |

Grapefruits (C. paradisisi) |

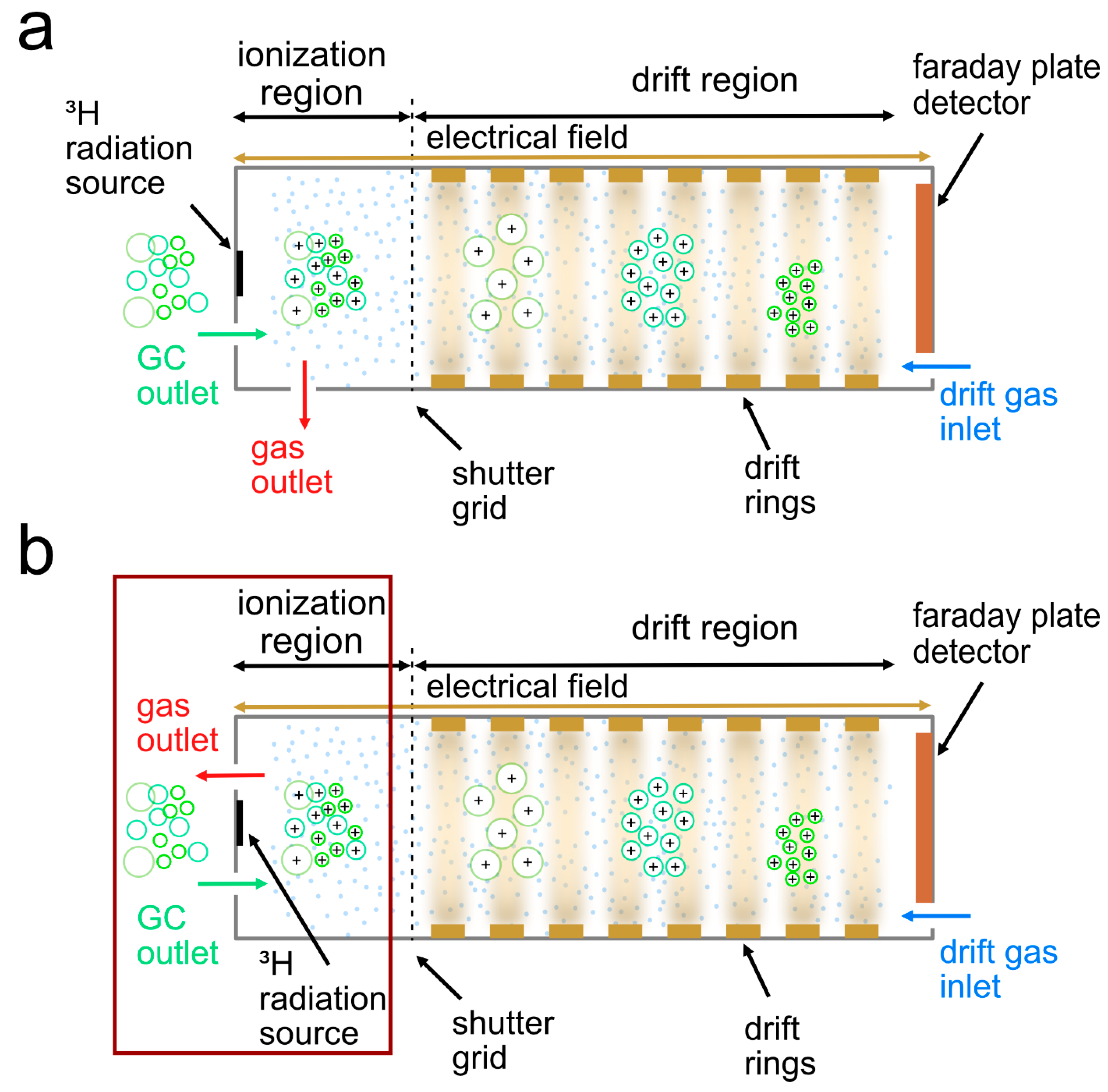

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Experimental Design for High Temperature Focus IMS

2.4. Data Processing and Evaluation

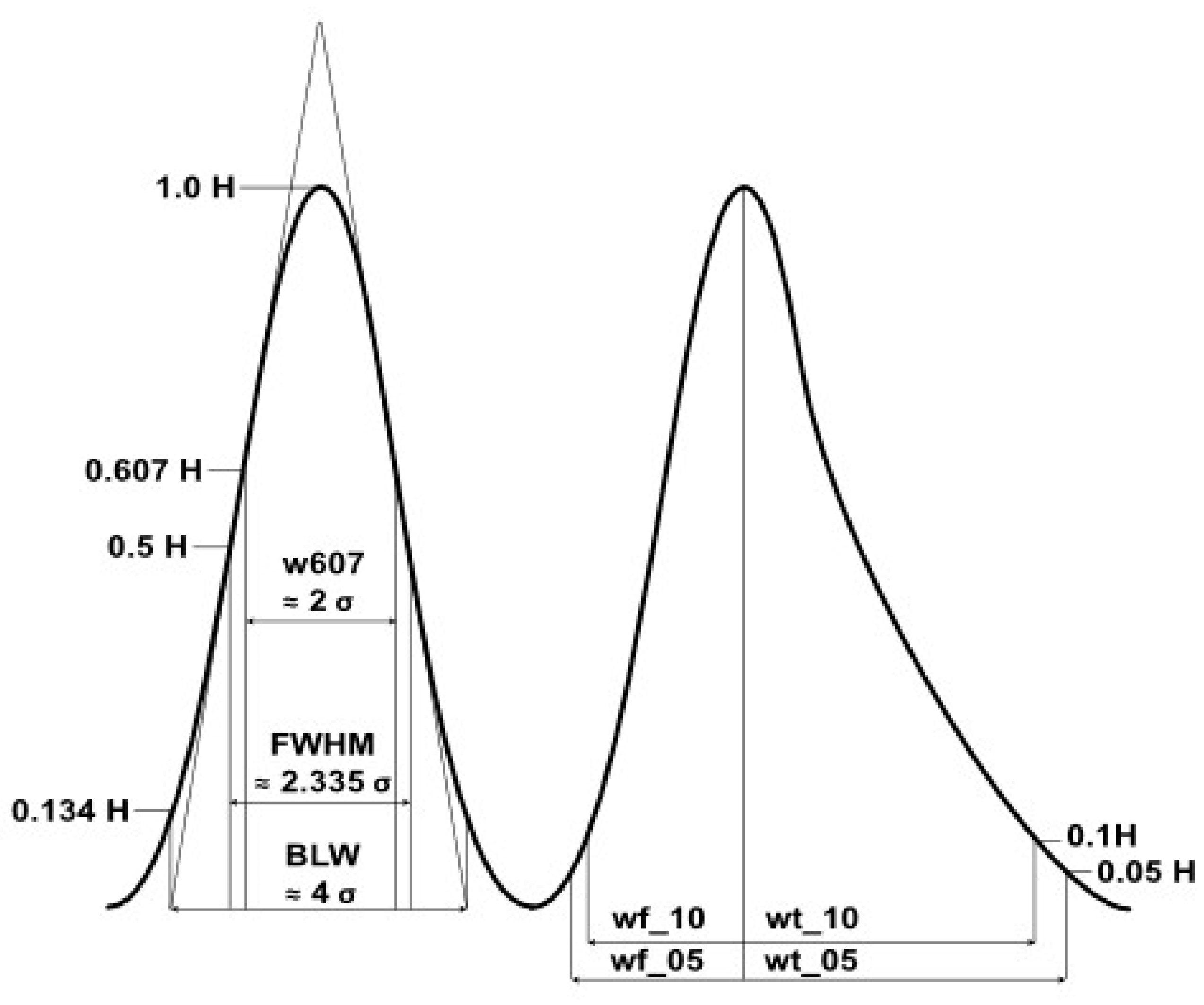

2.4.1. Reactant Ion Peak (RIP) and Background Calculations

2.4.2. Data Evaluation of the Experiments for High Temperature Focus IMS

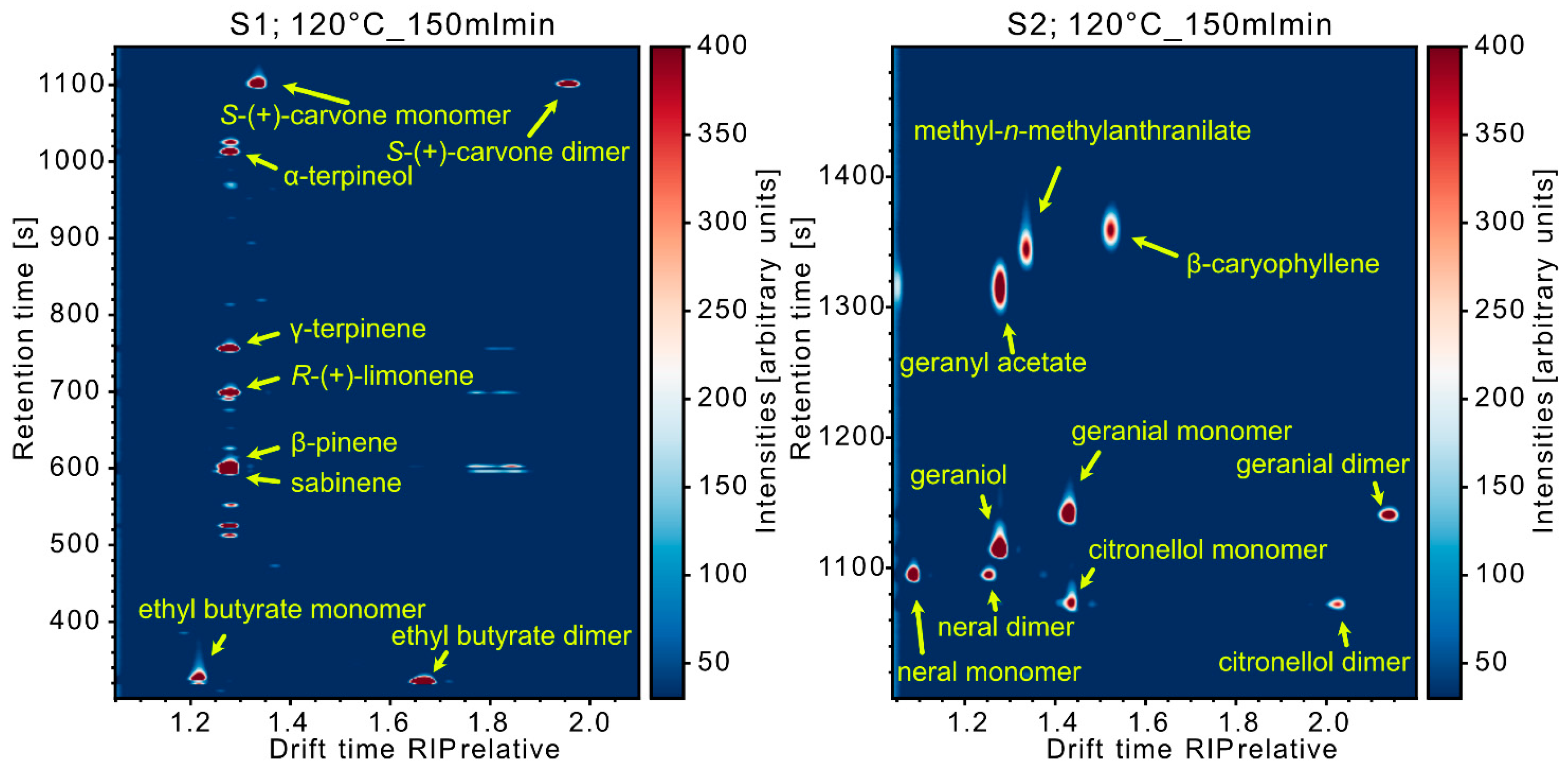

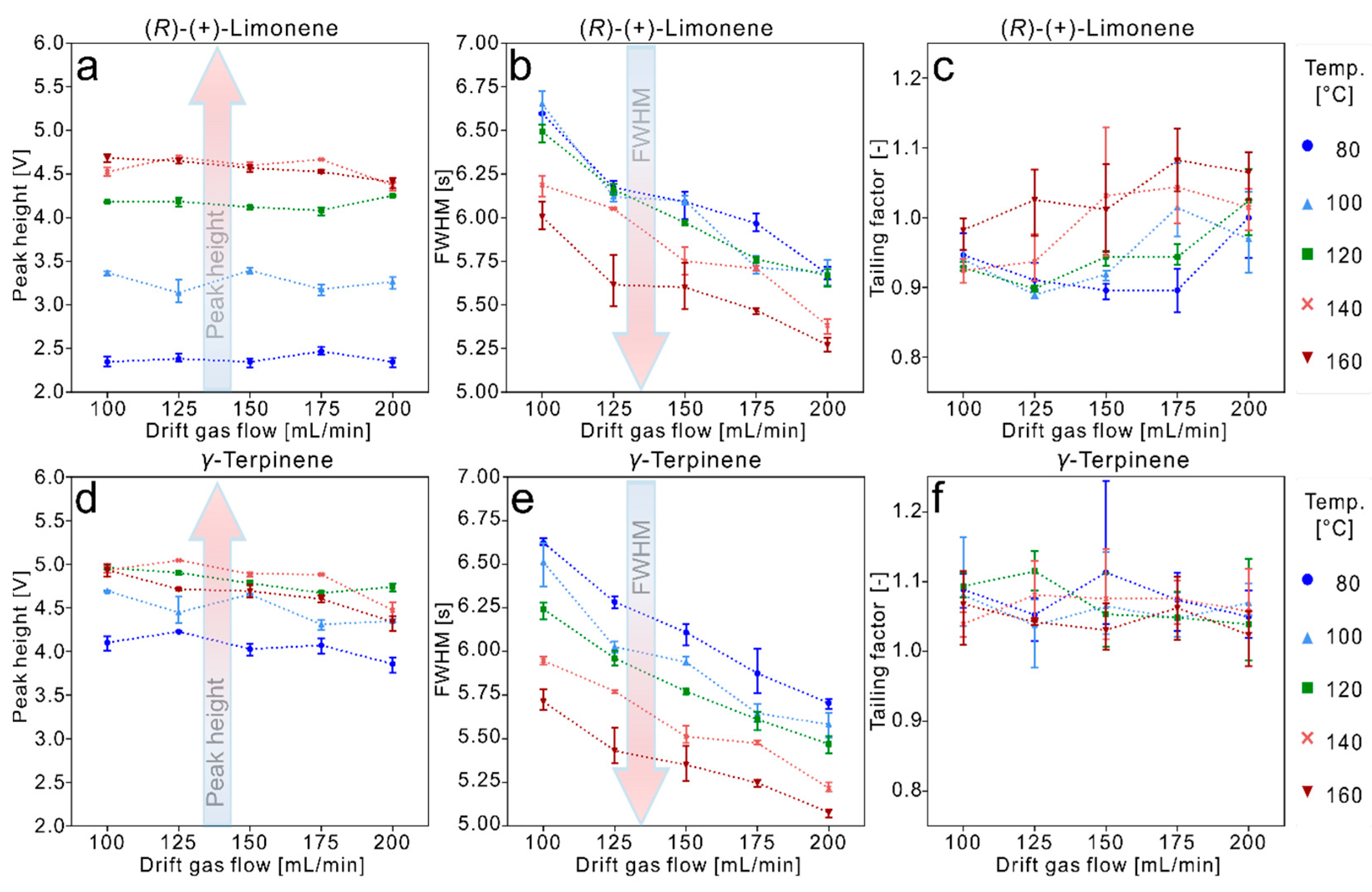

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. RIP & Background Calculations

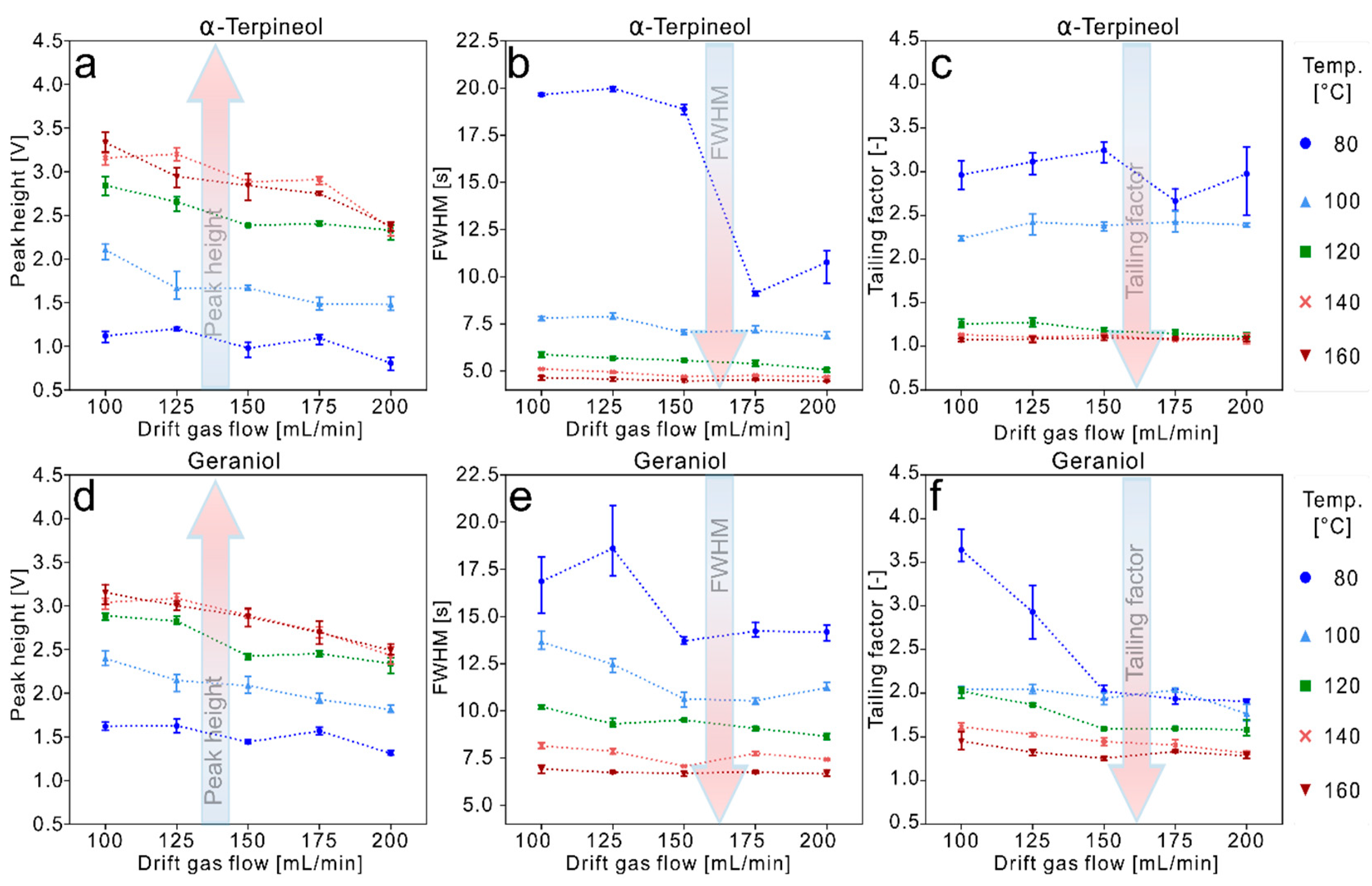

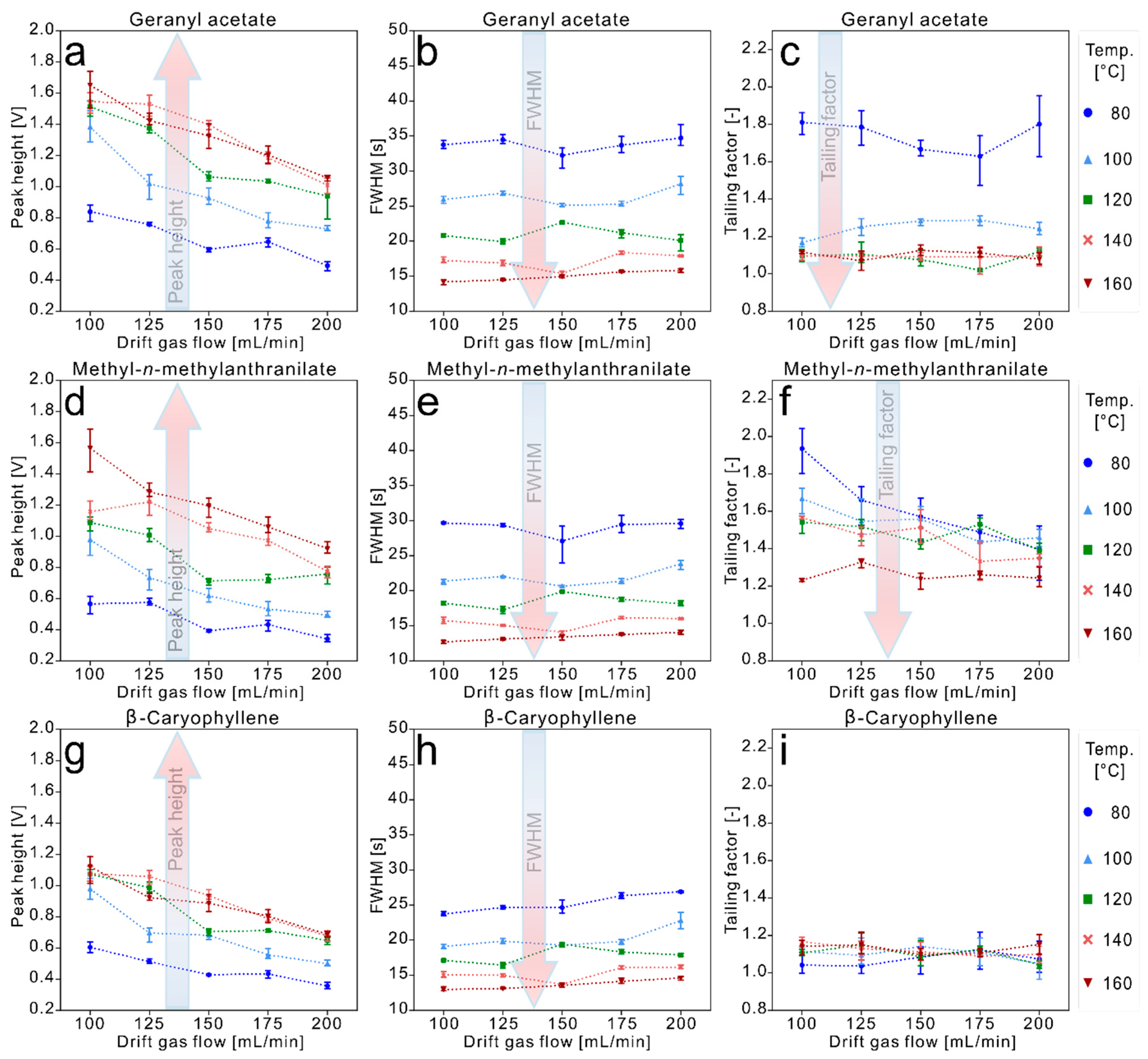

3.2. Data Evaluation of the Experiments for High Temperature Focus IMS

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Notes

References

- Parastar, H.; Weller, P. Towards greener volatilomics: Is GC-IMS the new Swiss army knife of gas phase analysis? TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 170, 117438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, N.; Birkenmeier, M.; Schwolow, S.; Rohn, S.; Weller, P. Volatile-Compound Fingerprinting by Headspace-Gas-Chromatography Ion-Mobility Spectrometry (HS-GC-IMS) as a Benchtop Alternative to 1H NMR Profiling for Assessment of the Authenticity of Honey. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhardt, N.; Schwolow, S.; Rohn, S.; Pérez-Cacho, P.R.; Galán-Soldevilla, H.; Arce, L.; Weller, P. Quality assessment of olive oils based on temperature-ramped HS-GC-IMS and sensory evaluation: Comparison of different processing approaches by LDA, kNN, and SVM. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, R.; Schwolow, S.; Rohn, S.; Weller, P. Volatilomic Profiling of Citrus Juices by Dual-Detection HS-GC-MS-IMS and Machine Learning-An Alternative Authentication Approach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Delgado, R.; Del Dobao-Prieto, M.M.; Arce, L.; Valcárcel, M. Determination of volatile compounds by GC-IMS to assign the quality of virgin olive oil. Food Chem. 2015, 187, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Maecker, R.; Vyhmeister, E.; Meisen, S.; Rosales Martinez, A.; Kuklya, A.; Telgheder, U. Identification of terpenes and essential oils by means of static headspace gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 6595–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanzmann, H.; Augustini, A.L.R.M.; Sanders, D.; Dahlheimer, M.; Wigger, M.; Zech, P.-M.; Sielemann, S. Differentiation of Monofloral Honey Using Volatile Organic Compounds by HS-GCxIMS. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, R.; Schwolow, S.; Rohn, S.; Weller, P. Comparison of PLSR, MCR-ALS and Kernel-PLSR for the quantification of allergenic fragrance compounds in complex cosmetic products based on nonlinear 2D GC-IMS data. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2020, 205, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Lin, T.; Ren, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bi, F.; Gu, L.; Hou, H.; He, J. Rapid discrimination of Citrus reticulata 'Chachi' by headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry fingerprints combined with principal component analysis. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 108985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitain, C.C.; Zischka, M.; Sirkeci, C.; Weller, P. Evaluation of IMS drift tube temperature on the peak shape of high boiling fragrance compounds towards allergen detection in complex cosmetic products and essential oils. Talanta 2023, 257, 124397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitmaier, E. Terpenes: Flavors, fragrances, pharmaca, pheromones, 1. Reprint; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2008; ISBN 9783527317868. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, J.; Bohlmann, J. Biotechnology of Isoprenoids; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-20106-1. [Google Scholar]

- Borsdorf, H.; Eiceman, G.A. Ion Mobility Spectrometry: Principles and Applications. Applied Spectroscopy Reviews 2006, 41, 323–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsdorf, H.; Rudolph, M. Gas-phase ion mobility studies of constitutional isomeric hydrocarbons using different ionization techniques. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2001, 208, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, J.W. New detectors in environmental monitoring using tritium sources. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, Articles 1996, 206, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COUNCIL DIRECTIVE 2013/59/EURATOM of 5 December 2013 laying down basic safety standards for protection against the dangers arising from exposure to ionising radiation .

- Garrido-Delgado, R.; Dobao-Prieto, M.M.; Arce, L.; Aguilar, J.; Cumplido, J.L.; Valcárcel, M. Ion mobility spectrometry versus classical physico-chemical analysis for assessing the shelf life of extra virgin olive oil according to container type and storage conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 2179–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiceman, G.A.; Nazarov, E.G.; Rodriguez, J.E.; Berglof, J.F. Positive reactant ion chemistry for analytical, high temperature ion mobility spectrometry (IMS): Effects of electric field of the drift tube and moisture, temperature, and flow of the drift gas. International Journal for Ion Mobility Spectrometry 1998, 1, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.G.; Eiceman, G.A.; Stone, J.A. Proton-bound cluster ions in ion mobility spectrometry. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry 1999, 193, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomareda, V.; Guamán, A.V.; Mohammadnejad, M.; Calvo, D.; Pardo, A.; Marco, S. Multivariate curve resolution of nonlinear ion mobility spectra followed by multivariate nonlinear calibration for quantitative prediction. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2012, 118, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.W.; Young, C.L. Analysis of Peak Profiles Using Statistical Moments. Journal of Chromatographic Science 1995, 33, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grushka, E. Characterization of exponentially modified Gaussian peaks in chromatography. Anal. Chem. 1972, 44, 1733–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalambet, Y. Data acquisition and integration. In Gas chromatography, 2nd ed.; Poole, C.F., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2021; pp. 505–524; ISBN 9780128206751. [Google Scholar]

- Kalambet, Y.; Kozmin, Y.; Mikhailova, K.; Nagaev, I.; Tikhonov, P. Reconstruction of chromatographic peaks using the exponentially modified Gaussian function. J. Chemometrics 2011, 25, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pápai, Z.; Pap, T.L. Analysis of peak asymmetry in chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A 2002, 953, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/1545 of 26 July 2023 amending Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards labelling of fragrance allergens in cosmetic products: Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/1545, 2023.

- European Parliament and the council of the European Union, Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on Cosmetic Products: Regulation (EC) No 1123/2009 .

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Fabroni, S.; Feng, S.; Rapisarda, P.; Rouseff, R. Chemistry of citrus flavor. In The genus citrus; Talon, M., Caruso, M., Gmitter, F.G., Eds.; United Kingdom; Woodhead publishing, an imprint of Elsevier: Duxford, 2020; pp. 447–470; ISBN 9780128121634. [Google Scholar]

- Rouseff, R.L.; Ruiz Perez-Cacho, P.; Jabalpurwala, F. Historical review of citrus flavor research during the past 100 years. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 8115–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berk, Z. Production of citrus juice concentrates. Citrus Fruit Processing; Elsevier, 2016; pp 187–217, ISBN 9780128031339.

- Wolford, R.W.; Kesterson, J.W.; Attaway, J.A. Physicochemical properties of citrus essential oils from Florida. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1971, 19, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugo, P.; Bonaccorsi, I.; Ragonese, C.; Russo, M.; Donato, P.; Santi, L.; Mondello, L. Analytical characterization of mandarin (Citrus deliciosa Ten.) essential oil. Flavour & Fragrance J 2011, 26, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, A.; Hitzemann, M.; Winkelholz, J.; Kirk, A.T.; Lippmann, M.; Thoben, C.; Wittwer, J.A.; Zimmermann, S. A hyper-fast gas chromatograph coupled to an ion mobility spectrometer with high repetition rate and flow-optimized ion source to resolve the short chromatographic peaks. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1736, 465376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).