1. Introduction

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is a major public health concern, particularly in children, representing 25% of all TBI cases in Europe[

1], and one of the leading causes of pediatric emergency departments (PED) visits[

2]. Children are particularly vulnerable to mTBI, and their developing brains may exhibit different injury mechanisms and recovery kinetics compared to adults. The management challenges in pediatric mTBI are distinct[

3], as clinicians strive to avoid unnecessary radiation while ensuring accurate diagnosis.

Diagnosis of mTBI relies primarily on self-reported symptoms and signs collected during clinical assessments[

4]. To detect potential intracranial injuries (ICI), imaging techniques such as Computer Tomography (CT) scans are employed[

5,

6]; however, their use is often limited in children due to concerns about radiation exposure[

7]. Consequently, clinicians frequently opt for monitoring the child’s symptoms over time rather than immediate imaging[

3,

8]. While this observational approach aims to minimize unnecessary risks, it often prolongs the child's stay in the PED, creating additional stress for both the patient and their family, and contributing to overcrowding. At present, clinicians lack reliable bedside tools to confidently discharge children with mTBI during the acute phase of management[

9].

mTBI can affect multiple brain structures, enhancing neuroinflammatory cascade, and damaging the blood-brain barrier (BBB)[

10]. All these injuries can lead to the leakage of proteins into the bloodstream[

11,

12]. Blood-based biomarkers have gained attention as a potential fast and cost-effective method for determining whether a patient with mTBI should undergo a head CT scan. Given the complexity and variability of mTBI, relying on a single biomarker for diagnosis may lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity. As a result, combining biomarkers into panels appeared to be more effective for better detecting diverse types of brain injuries[

13,

14]. While combinations of biomarkers have been investigated in adult mTBI[

15,

16], their performance in the pediatric population remains to be explored.

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) is a well-established protein released by astrocytes and has been extensively studied in the context of mTBI. Notably, its combination with Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL-1) has been explored to differentiate between patients with ICI on CT (CT+) and patients without (CT−) following mTBI. The combination of GFAP and UCHL1 showed a sensitivity of 97 %, a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99%, and a specificity of 36% in mTBI patients[

16,

17]. Another combination including GFAP has been tested in adult mTBI patients alongside Heart Fatty Acid Binding Protein (HFABP). HFABP, a capillary-binding protein indicative of vascular brain injury, has been found elevated in adult mTBI patients with CT+ results[

18]. The GFAP and HFABP combination improved specificity to 46% while maintaining 100% sensitivity[

15].

The S100 calcium-binding protein B (S100b) is another protein associated with astrocyte damage and has been extensively studied in the context of mTBI[

19,

20]. It has been included in both the Scandinavian[

21] and French[

22] guidelines for adults, based on its demonstrated ability to identify one third of patients for whom unnecessary CT scans could have been avoided[

23,

24]. In children, S100b is to date the most described blood biomarker in mTBI patients, also showing a reduction of one third of unnecessary CT scans[

20,

25,

26]. However, S100b is age-related, with significantly higher physiological expression observed in the healthy pediatric population during the first three years of life[

27].

Additional blood-based biomarkers that may be released from different brain cell components or cell types have also been investigated in mTBI[

28]. They have been shown to help differentiate between CT+ and CT− patients[

29,

30]. In pediatric TBI patients, a recent study demonstrated altered cytokine profiles following mTBI, highlighting the effect of neuro-inflammation triggered by the trauma[

31].

Based on these results, this study aimed to explore biomarker combinations to enhance diagnostic accuracy in safely ruling out children without ICI after mTBI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

Children aged 0 to 16 years with a mTBI occurring within 24 hours prior to their presentation at one of the participating PED were included. Five hospitals in Switzerland were part of the study (Geneva University Hospitals, Fribourg Hospital HFR, Neuchâtel Hospital (RHNE), University Children's Hospital Zurich and Inselspital, Bern University Hospital). Institutional review board approval was received; the study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki; and was registered at

www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT06233851.

Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of the children, as well as from the children themselves if they were 14 years of age or older. mTBI was defined by one of the following conditions: Head trauma with (1) a GCS score of 14; or (2) a GCS score of 15 with at least one of the following symptoms: loss of consciousness (LOC), post-traumatic amnesia (PTA), persistent headaches, irritability, three or more episodes of vomiting, confusion, dizziness or vertigo, post-traumatic seizure, or transient neurological abnormalities; or (3) evidence of a basilar skull fracture; or (4) severe mechanism of injury, such as a traffic accident or a fall from a height greater than 0.9 meters in children under 2 years old, or over 1.5 meters in children 2 years or older.

Exclusion criteria included: participation in another clinical study involving pharmacological treatment, recent alcohol consumption or psychoactive substance use, a traumatic brain injury (TBI) within the past month, seizures within the last month, a diagnosis of Down syndrome, acute encephalopathy, encephalitis, meningitis, or refusal to provide consent.

A group of healthy children was also recruited. Inclusion criteria were any child aged 16 or younger with a scheduled blood sample in the ambulatory care unit and without TBI. Exclusion criteria were the same as those defined for the TBI group.

2.2. Intervention and Data Collection

After informed consent was obtained, a blood sample was drawn as soon as possible, but no later than 24 hours after the trauma. The study did not interfere with any medical decision-making. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève (HUG)[

32,

33].

2.3. Blood-Based Biomarker Analysis

Serum samples were obtained by centrifugation and stored at −80°C. IL6, NfL, NTproBNP, GFAP, IL10, S100b, and HFABP concentrations were measured using enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA): R-plex Human NfL (F217X), NTproBNP (F214I), GFAP (F211M), S100b (F212E), and FABP3/HFABP (F214T) antibody sets; and V-plex Proinflammatory Panel 1 (Human) with IL6 and IL10 antibodies sets (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD, USA). Lower limit of detection (LLoD) was respectively 5.5 pg/mL with a calibration range of 12.21-50,000 pg/mL for NfL; 0.30 pg/mL and 0.12-500 pg/mL for NTproBNP; 63 pg/mL and 122–500,000 pg/mL for GFAP; 1.6 pg/mL and 1.22–5000 pg/mL for S100b; 90 pg/mL and 24.41–100,000 pg/mL for HFABP; 0.06 pg/mL and 0.06–488 pg/mL for IL6; and finally 0.04pg/mL and 0.04–233 pg/mL for IL10. The lower limit of quantification (LLoQ) was determined as the minimum concentration with a coefficient of variation (CV) under 20% and a recovery rate between 80% and 120%. Duplicate control serum samples were analyzed on each plate, ensuring that intra- and inter-plate coefficients of variation (CVs) remain below 20%. All kits were utilized following the manufacturers' guidelines.

2.4. Outcome Measures

The main outcome measure was the identification of ICI. To assess ICI, the study followed the PECARN criteria, which include intracranial hemorrhage or contusion, cerebral edema, traumatic infarction, diffuse axonal or shearing injuries, sigmoid sinus thrombosis, midline shift, signs of brain herniation, skull diastasis, pneumocephalus, or a skull fracture depressed by at least the thickness of the skull table. A single pediatric radiologist (CH), who was blinded to both clinical details and biomarker results, reviewed all CT scans. Cases with any of these criteria were classified as CT+, while those without were considered CT−. For non-scanned mTBI patients, they were considered negative for ICI in the absence of secondary presentation to PED.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R (

http://www.rproject.org, version 4.4.1) in RStudio (

http://www.rstudio.com, version 2024.09.0). Biomarker concentrations were normalized using their medians as correction factors. Patients were dichotomized into two groups: 1) patients with ICI on CT (= CT+); and 2) patients without ICI on CT or without CT scan but with in-hospital-observation (= CT− & Obs.). Differences between groups were established using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test, given that the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test revealed that all protein levels were non-normally distributed (p < 0.05). Chi-squared test was used for statistical analyses of the clinical data. Statistical significance was inferred at p < 0.05. The levels of biomarkers are presented using box- and dot-plots with a log10 Y-scale. Biomarker’s ability for classifying patients according to their group was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves with the pROC package in R. Individuals’ blood-biomarkers performances were already explored during intermediate analysis[

26,

34,

35]. Biomarker combinations were analyzed with PanelomiX[

36,

37], which uses iterative permutation-response calculations. The cut-off values for each biomarker were adjusted iteratively by 2% increment quantiles. In each iteration, the optimal performance was identified by maximizing specificity (SP) while maintaining 100% sensitivity (SE). This strategy aimed to avoid any false negatives among mTBI patients (100% Negative Predictive Value (NPV)) and safely discharge the maximum of patients without ICI. Models were limited to a maximum of two biomarkers. ROC analysis was applied to assess model performance. Only patients with complete data for all tested biomarkers were included in the analysis. The correlation between biomarker concentrations and patient age were evaluated in the healthy population, by Spearman correlation coefficient and its p-value.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical parameters

A total of 419 mTBI children were included between October 2020 and February 2023. Among these, 18 (4%) patients had an ICI on CT scan (CT+), 79 patients (19%) had a CT scan without ICI (CT−), and the remaining 322 patients (77%) were kept for observation without imaging (in-hospital-observation). None of the last group developed a subsequent ICI. Both the CT− and in-hospital-observation without imaging patients were grouped together (CT− & Obs.), and their clinical parameters were compared to the CT+ group (

Table 1).

The age of included children ranged from 1 month to 16 years in the CT− & Obs. group, and from 9 months to 15 years in the CT+ group. The mean age across both groups was 8 years. Most patients had a GCS of 15 with associated symptoms (86% and 66% for the CT− & Obs. and CT+ group, respectively). Signs of basilar skull fracture and severe mechanism of injury were reported in both groups, but significantly more in CT+ patients (33.3% and 77.8% respectively). There were no significant differences in the reported symptoms at admission between the compared groups. However, the two most prevalent associated symptoms were PTA (28.9%) and persistent headaches (26.2%) in the CT− & Obs. group; and persistent headaches (33.3%) and more than three episodes of vomiting (22.2%) in the CT+ group (

Table 1). Extracranial injuries (ECI) were significantly more reported in the CT+ group and mainly corresponded to fractures of the facial bones. The presence of simple skull fractures seen on CT was also significantly higher in the CT+ patient group (p < 0.001) (

Table 1). No other significant differences in clinical parameters were observed within the CT− & Obs. group and the CT+ group.

3.2. Individuals’ Biomarkers Performances

The mean with SD of all biomarkers, as well as the median with minimum and maximum values are reported in

Table 2. The median time between head trauma and blood sampling was 8 hours for CT+ patients and 6 hours for the other mTBI patients, with no significant difference (p = 0.298).

Blood concentration of IL6, NfL, GFAP, and S100b was significantly increased in CT+ patients compared to CT− and in-hospital-observation patients (

Table 2).

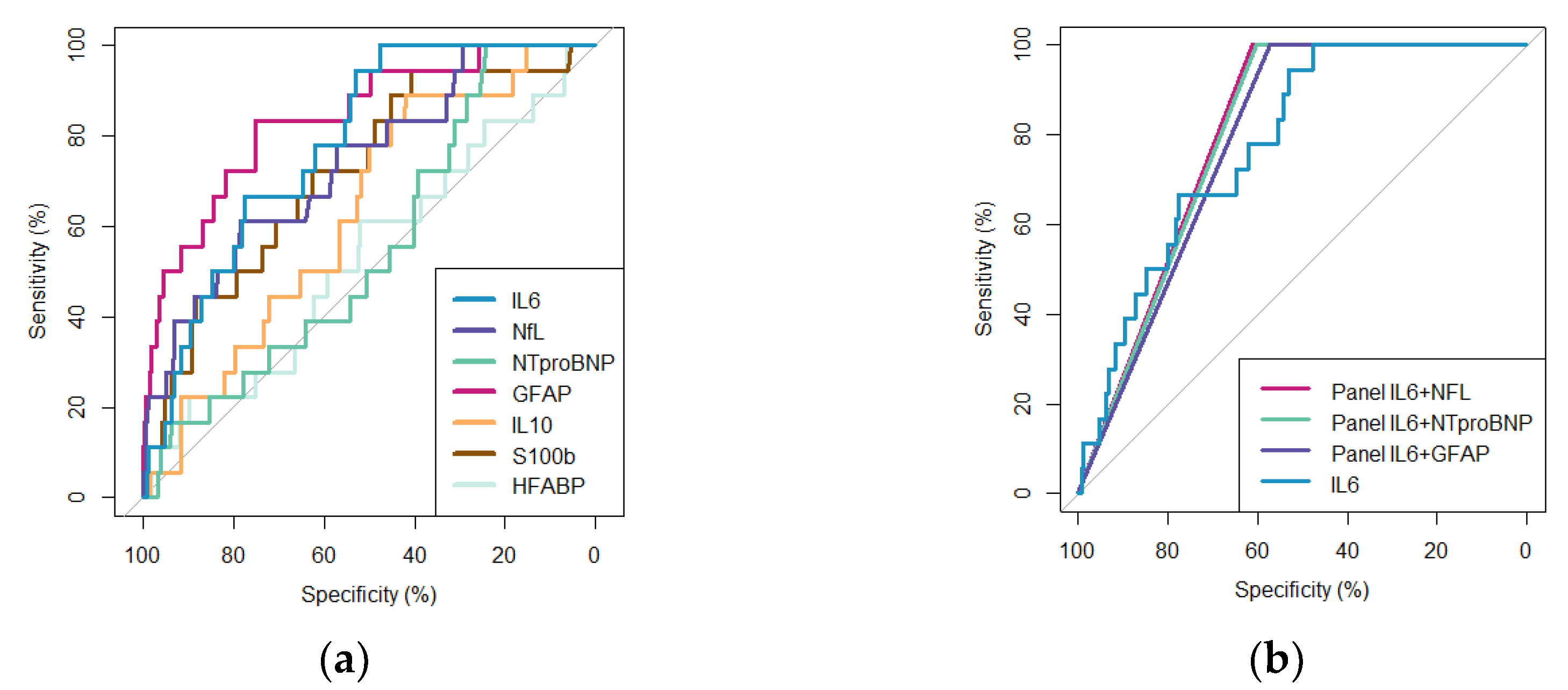

The diagnostic performance of each individual biomarker is presented with ROC curves and their AUC in

Figure 1a. At 100% sensitivity, IL6 yielded the best specificity of 47.6% [95% IC: 42.9 – 52.4 %], followed by NfL with 29.4% [95% IC: 25.0 – 33.8 %], GFAP with 25.7% [95% IC: 21.5 – 29.9%], and NTproBNP with 24.4% [95% IC: 20.3 – 28.6%]. IL10, S100b, and HFABP were not able to reach more than 20% of specificity at 100% of sensitivity (

Figure 1a and

Table 3a).

3.3. Combinations of Biomarkers Performances

Each possible duplex combination of biomarkers was tested for their capacity to rule out, setting the sensitivity at 100%. IL6 was present in each of the three best duplex combinations (

Figure 1b and

Table 3b). In association with either NfL, NTproBNP, or GFAP; IL6 was found to safely identify CT− and in-hospital-observation patients with more than 55% specificity. The duplex IL6 + NfL showed the best performance with a specificity reaching 61% [95% IC: 56-65%]; followed by IL6 + NTproBNP (60% [95% IC: 55-65%]), and IL6 + GFAP (57% [95% IC: 53-62%]). ROC curves of the three best duplex, compared to individual proteins are presented in

Figure 1b. The other duplex combinations were below 50% specificity when sensitivity was set at 100%.

A confusion matrix was built based on the prediction rules defined by the IL6 + NfL combinations (

Table 3c) and allowed to truly identify all CT+ (100% NPV) and truly discharged 33 CT− (out of 79) and 212 (out of 322) observed without imaging patients.

3.4. Age-Correlation in the Healthy Population

The age-correlation of each biomarker was investigated in a healthy group of 99 children, aged 1 month to 16 years (mean age 8 years). Spearman correlation analysis revealed that GFAP, IL10, and S100b were negatively and significantly correlated with age. NfL and HFABP were also significantly age-correlated but with a low correlation coefficient (Spearman coef. of -0.22); and neither NTproBNP nor IL6 were age-correlated.

4. Discussion

This study explored both the individual and combined performances of seven blood biomarkers in distinguishing children with and without ICI presenting in a PED with mTBI. Among the 419 children included, 23% underwent CT scans, of whom 19% were found to have an ICI (representing 4% of the total cohort). These proportions are consistent with reported prevalence in the literature[

2,

3,

38,

39,

40,

41] and underscore the relevance of finding reliable biomarkers to reduce unnecessary CT scans and minimize prolonged hospital stays for children without ICI.

The measurement of IL6 within 24 hours of trauma successfully identified 47% of children without ICI, while maintaining 100% sensitivity in detecting those with ICI. These results confirm prior findings from intermediate analyses in this cohort[

34]. But it also highlights the limitation of using a single biomarker, due to the complex physiopathology of mTBI.

Combining biomarkers aimed to increase diagnostic specificity while maintaining high sensitivity to safely discharge patients without ICI. Notably, the combination of IL6 with either NfL, NTproBNP, or GFAP significantly improved specificity, with the IL6 + NfL panel reaching 61% specificity and 100% sensitivity. Retrospectively, in our cohort, these combinations would have allowed the safe discharge of 33 out of 79 children who underwent CT scans without an ICI and 212 out of 322 children who were kept under observation for symptom monitoring in the PED, without missing any patients with an ICI. These findings represent a significant clinical benefit by reducing 42% of unnecessary CT scans and decreasing 67% of observations in PED, with a 100% NPV.

Among previously studied biomarkers, S100b has been shown to identify 34% of CT− patients with 100% sensitivity. Its short half-life in blood has led to recommendations for a maximum delay of 3–6 hours for sampling after head trauma[

20,

22,

25,

42]. In our study, S100b exhibited lower specificity (below 20%) when assessed across the full cohort. Even when selecting only patients sampled within 6 hours post-trauma, IL6 outperformed S100b, reinforcing IL6's potential as a more robust marker in both early and late trauma windows[

34]. This suggests that IL6 could be particularly valuable in real-world settings, where many patients present to the hospital more than 6 hours after injury. In our cohort, patients arriving at the PED later than 6 hours after trauma represented one quarter and should not be ignored.

Importantly, IL6 also benefits from being independent of age, making it a versatile decision-making tool across pediatric populations. While both S100b and GFAP are known to be age-dependent, requiring adjustments for use in young children, IL6, along with NTproBNP, can be applied without age stratification, further enhancing its clinical utility.

Given that IL6 is a cytokine released during neuroinflammatory responses, its elevated level post-trauma is unsurprising, although cytokines are not currently used clinically in this context. Furthermore, its combination with brain-specific proteins such as NfL, GFAP, or NTproBNP enhances its specificity, suggesting that pairing systemic inflammatory markers with proteins reflecting brain injury could yield a powerful diagnostic tool[

28]. In cases of multiple traumas, where IL6 might be elevated due to injuries outside the brain, combining it with brain-specific markers could help isolate brain trauma.

The three proteins IL6, NfL, and NTproBNP are already widely available in routine clinical analysis for other conditions, making them readily applicable in clinical practice once their utility in mTBI is validated. GFAP is also available on established diagnostic platforms, which could expedite the integration of these biomarker panels into clinical guidelines for mTBI management.

Strengths and Limitations

This study's key strengths include its large cohort size, making it one of the largest studies of pediatric mTBI biomarkers to date; and its comprehensive biomarker analysis within 24 hours of injury. The inclusion of both scanned and non-scanned patients enhances the generalizability of the findings, particularly in a pediatric population where radiation exposure is a critical concern and imaging rate is lower than in adult mTBI care.

Our study highlights the need to address not only CT scanned patients but also the high majority (77% in this cohort) of mTBI patients kept under observation without imaging. Reducing observation times for these patients could significantly alleviate stress for families and reduce hospital costs.

However, this study also has limitations. The cohort contained relatively few CT+ patients, reflecting the fact that most children with mTBI do not have ICI. While this is consistent with clinical practice, it limits the power of our analysis to fully explore the diagnostic performance for more severe injuries. Indeed, future mTBI biomarker studies should focus on detecting clinically important traumatic brain injuries rather than just ICI. To clearly incorporate blood-biomarker measurements into the widely used PECARN[

3] decision-making algorithm, further studies should be based on the same inclusion criteria.

Additionally, we only evaluated combinations of two biomarkers due to statistical limitations related to sample size. This prevented us from exploring more complex multi-biomarkers or clinical panels that could potentially yield even higher specificity. However, given that IL6 and its combinations showed robust performance, expanding this work to include larger cohorts and more biomarkers should be a priority.

Lastly, while we used a research-based platform for measuring biomarker levels, routine clinical validation is needed to establish practical cutoff values for each biomarker. This limitation can be addressed in future studies, as the biomarkers assessed are already available on validated clinical platforms.

Ultimately, mTBI is not always mild. It presents in various ways, with diverse recovery trajectories. Researchers are working to refine its classification by identifying endopheno-types[

43,

44]. Additionally, combined blood biomarkers may contribute to a biological signature of the trauma.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms, in a larger pediatric cohort, the diagnostic potential of seven blood-based proteins to safely identify children without ICI after a mTBI. Among these, the combination of IL6 with either NfL, NTproBNP, or GFAP demonstrated strong diagnostic value, suggesting its potential integration as a clinical decision-making tool for the management of mTBI in children. Specifically, the combination of IL6 and NfL was able to safely rule out ICI in 61% of cases with 100% NPV, significantly reducing the need for unnecessary CT scans and shortening the length of stay in PEDs. These findings highlight the promising role of biomarker panels in optimizing pediatric mTBI management, though further validation in external cohorts is needed to confirm their broader applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ACC, VP, JCS, SM, CK; data curation, ACC, VP; formal analysis, ACC; funding acquisition, JCS and SM; investigation, ACC, LG; methodology, ACC, VP, JCS, SM, CK; project administration: ACC, VP, JCS, SM, CK; resources, SM, FM, FS, FR, VW, MS, CRS, CH; JCS, VP; software, ACC; supervision, JCS and SM; validation, ACC, JCS, SM; writing—original draft preparation, ACC; writing—review and editing, all authors;

Funding

This research was funded by a private grant from Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) for its first year of recruitment.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Geneva (CCER-ID: 2020-01533 on the 12th of August 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank patients and their families for their participation in this study. We thank all the members of the t-BIOMAP study, clinicians, research nurses, radiologists, neuropsychologist, hospital laboratories and case managers. We thank the Platform of Pediatric Clinical Research of the HUG for their invaluable help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| BBB |

Blood-Brain Barrier |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| CV |

Coefficient of Variation |

| ECI |

ExtraCranial Injuries |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunoassay |

| GCS |

Glasgow Coma Scale |

| GFAP |

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| HFABP |

Heart Fatty-Acid-Binding Protein |

| HFR |

Fribourg Hospital |

| HUG |

Hopitaux Universitaires de Genève |

| IC |

Confidence Interval |

| ICI |

Intracranial injury |

| IL10 |

Interleukin 10 |

| IL8 |

Interleukin 8 |

| IL6 |

Interleukin 6 |

| IQR |

Inter Quartile Range |

| LLD |

Lower Limit of Detection |

| LLOQ |

Lower Limit of Quantification |

| LOC |

Loss of Consciousness |

| Max |

Maximum |

| Min |

Minimum |

| mTBI |

mild Traumatic Brain Injury |

| NfL |

Neurofilament Light chain |

| NPV |

Negative Predictive Value |

| NTproBNP |

N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide |

| PECARN |

Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network |

| PED |

Pediatric Emergency Department |

| PTA |

Post Traumatic Amnesia |

| RHNE |

Neuchâtel Hospital |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| S100b |

S100 calcium-binding protein B |

| SE |

Sensitivity |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SP |

Specificity |

| TBI |

Traumatic Brain Injury |

| UCHL-1 |

Ubiquitin Carboxy-terminal Hydrolase L1 |

References

- Lumba-Brown A, Yeates KO, Sarmiento K, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Among Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, e182853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewan MC, Mummareddy N, Wellons JC, 3rd, Bonfield CM. Epidemiology of Global Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Qualitative Review. World Neurosurg. 2016, 91, 497–509 e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009, 374, 1160–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babl FE, Borland ML, Phillips N, et al. Accuracy of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE head injury decision rules in children: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2017, 389, 2393–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg J, Holm L, Cassidy JD, et al. Diagnostic procedures in mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Rehabil Med 2004, (Suppl. 43), 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydel MJ, Preston CA, Mills TJ, Luber S, Blaudeau E, DeBlieux PM. Indications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injury. N Engl J Med. 2000, 343, 100–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357, 2277–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Holm L, Kraus J, Coronado VG, Injury WHOCCTFoMTB. Methodological issues and research recommendations for mild traumatic brain injury: the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Rehabil Med 2004, (43 Suppl), 113–25. [CrossRef]

- Levin HS, Diaz-Arrastia RR. Diagnosis, prognosis, and clinical management of mild traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 506–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi A, Braun M, Ahluwalia M, et al. Revisiting Traumatic Brain Injury: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Interventions. Biomedicines 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Zetterberg H, Smith DH, Blennow K. Biomarkers of mild traumatic brain injury in cerebrospinal fluid and blood. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2013, 9, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapin V, Gaulmin R, Aubin R, Walrand S, Coste A, Abbot M. Blood biomarkers of mild traumatic brain injury: State of art. Neurochirurgie. 2021, 67, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvier D, Oris C, Brailova M, Durif J, Sapin V. Interest of blood biomarkers to predict lesions in medical imaging in the context of mild traumatic brain injury. Clinical Biochemistry. 2020, 85, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siman R, Toraskar N, Dang A, et al. A Panel of Neuron-Enriched Proteins as Markers for Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2009, 26, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagerstedt L, Egea-Guerrero JJ, Bustamante A, et al. Combining H-FABP and GFAP increases the capacity to differentiate between CT-positive and CT-negative patients with mild traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0200394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarian JJ, Welch RD, Caudle K, et al. Accuracy of a rapid glial fibrillary acidic protein/ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 test for the prediction of intracranial injuries on head computed tomography after mild traumatic brain injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2021, 28, 1308–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarian JJ, Biberthaler P, Welch RD, et al. Serum GFAP and UCH-L1 for prediction of absence of intracranial injuries on head CT (ALERT-TBI): a multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurology. 2018, 17, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerstedt L, Egea-Guerrero JJ, Bustamante A, et al. H-FABP: A new biomarker to differentiate between CT-positive and CT-negative patients with mild traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0175572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oris C, Kahouadji S, Durif J, Bouvier D, Sapin V. S100B, Actor and Biomarker of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Oris C, Pereira B, Durif J, et al. The Biomarker S100B and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2018, 141. [CrossRef]

- Unden J, Ingebrigtsen T, Romner B, Scandinavian Neurotrauma C. Scandinavian guidelines for initial management of minimal, mild and moderate head injuries in adults: an evidence and consensus-based update. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Jardine C, Payen JF, Bernard R, et al. Management of patients suffering from mild traumatic brain injury 2023. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2023, 42, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcagnile O, Anell A, Undén J. The addition of S100B to guidelines for management of mild head injury is potentially cost saving. Bmc Neurol. 2016, 16, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unden L, Calcagnile O, Unden J, Reinstrup P, Bazarian J. Validation of the Scandinavian guidelines for initial management of minimal, mild and moderate traumatic brain injury in adults. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano S, Holzinger IB, Kellenberger CJ, et al. Diagnostic performance of S100B protein serum measurement in detecting intracranial injury in children with mild head trauma. Emerg Med J. 2016, 33, 42–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiollaz AC, Pouillard V, Spigariol F, et al. Management of Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Patients: S100b, Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein, and Heart Fatty-Acid-Binding Protein Promising Biomarkers. Neurotrauma Rep. 2024, 5, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvier D, Castellani C, Fournier M, et al. Reference ranges for serum S100B protein during the first three years of life. Clin Biochem. 2011, 44, 927–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes J, Spitz G, Major BP, et al. Utility of Acute and Subacute Blood Biomarkers to Assist Diagnosis in CT-Negative Isolated Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurology. 2023, 101, E1992–E2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posti JP, Takala RSK, Lagerstedt L, et al. Correlation of Blood Biomarkers and Biomarker Panels with Traumatic Findings on Computed Tomography after Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2019, 36, 2178–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain I, Marklund N, Czeiter E, Hutchinson P, Buki A. Blood biomarkers for traumatic brain injury: A narrative review of current evidence. Brain Spine 2024, 4.

- Ryan E, Kelly L, Stacey C, et al. Mild-to-severe traumatic brain injury in children: altered cytokines reflect severity. J Neuroinflamm 2022, 19.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009, 42, 377–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiollaz AC, Pouillard V, Habre C, et al. Diagnostic potential of IL6 and other blood-based inflammatory biomarkers in mild traumatic brain injury among children. Front Neurol. 2024, 15, 1432217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiollaz AC, Pouillard V, Habre C, et al. Evaluating NfL and NTproBNP as predictive biomarkers of intracranial injuries after mild traumatic brain injury in children presenting to emergency departments. Front Neurol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, X. PanelomiX for the Combination of Biomarkers. Methods Mol Biol. 2019, 1959, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. PanelomiX: A threshold-based algorithm to create panels of biomarkers. Translational Proteomics. 2013, 1, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe L, Babl F, Anderson V, Catroppa C. The epidemiology of paediatric head injuries: Data from a referral centre in Victoria, Australia. J Paediatr Child H. 2009, 45, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönnerqvist C, Brus O, Olivecrona M. Validation of the scandinavian guidelines for initial management of minor and moderate head trauma in children. Eur J Trauma Emerg S. 2021, 47, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan S, Eapen N, Phillips N, et al. PECARN algorithms for minor head trauma: Risk stratification estimates from a prospective PREDICT cohort study. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2021, 28, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigrovic LE, Kuppermann N. Children With Minor Blunt Head Trauma Presenting to the Emergency Department. Pediatrics. 2019, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unden J, Dalziel SR, Borland ML, et al. External validation of the Scandinavian guidelines for management of minimal, mild and moderate head injuries in children. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giza CC, Gioia G, Cook LJ, et al. CARE4Kids Study: Endophenotypes of Persistent Post-Concussive Symptoms in Adolescents: Study Rationale and Protocol. J Neurotrauma. 2024, 41, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haber M, Amyot F, Kenney K, et al. Vascular Abnormalities within Normal Appearing Tissue in Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2018, 35, 2250–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).