1. Introduction

Higher Education Institutions (HEI) play an important role in reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and integrating these into teaching and research [

1,

2]. Furthermore, HEIs should not only consider the SDGs theoretically in their core activities, but also act accordingly in their own operations, as they have a role model function [

3]. Among SDGs, combatting climate change is crucial, as climate change is a major barrier for achieving nearly all SDGs except SDG 17 (Partnership for the goals) [

4]. Therefore, various universities already set themselves goals to become carbon neutral, for example in the UK or in Germany [

5,

6].

The CO

2-Footprint of HEIs can differ substantially depending (beside other factors) on the selected time metric and functional unit, as well as the data collection boundary applied [

7]. However, the review of Valls-Val and Bovea (2021), which analyzed 35 publications focusing on the CO

2-Footprint of HEIs, showed that independently of these factors, scope 1 and 2 emissions represent a major emission hot-spot for most of the HEIs assessed [

7]. In accordance with the GHG protocol, the scopes encompass direct greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions caused by sources which are controlled or owned by the HEI (scope 1) and indirect GHG emissions which occur due to the generation of purchased electricity (scope 2) [

8]. To reduce the scope 1 and 2 emissions of HEIs several measures were proposed. A reduction of the scope 1 emissions could for example be achieved through the replacement of fossil-fueled vehicles by electric cars [

9]. As scope 2 encompasses the indirect GHG emissions caused by the generation of purchased electricity, several studies emphasize the importance of purchasing electricity from renewable sources or producing renewable energy on campus [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Another possible measure is the reduction of the electricity consumption of the HEI, for example through the implementation of an energy management system [

14].

However, even if all reduction measures are taken, residual GHG emissions will remain which are hard to avoid. Therefore, most HEIs must compensate the remaining emissions for example by buying carbon credits which are generated by emission reduction projects somewhere else. This approach however has been criticized because it bears the risk of over-crediting the reduction projects or even incentivize to produce waste gases to generate credits [

15,

16,

17,

18]. The latter means that there is the probability that purchased carbon credits will not truly lead to emission reductions. HEIs with a focus on agriculture, viticulture, horticulture, or forestry, which often own and manage agricultural, or forest land for research and education purposes, are in a unique situation regarding other options: They do have waste biomass. Hence, these HEIs have the possibility to offset GHG emissions on their own premises, for example through carbon sequestration in form of living biomass, or organic carbon in the soil, as well as through the production and utilization of biochar or the use of silicate rock powder (enhanced weathering) [

19,

20].

One example for such an agricultural HEI is Geisenheim University (HGU) which is located in the federal state of Hesse in Southwest-Germany. The HGU focuses on viticulture, horticulture and landscape architecture research and education and has over 60 ha of open land, research areas and parks. According to a resolution of the state government of Hesse from 2009, the state administration, including all public universities in Hesse, have to become climate neutral until 2030. By 2020, there was still a gap of 206,966 t CO

2, or even 357,788 t CO

2, if purchasing of additional certificates and other market instruments are not taken into account [

21].

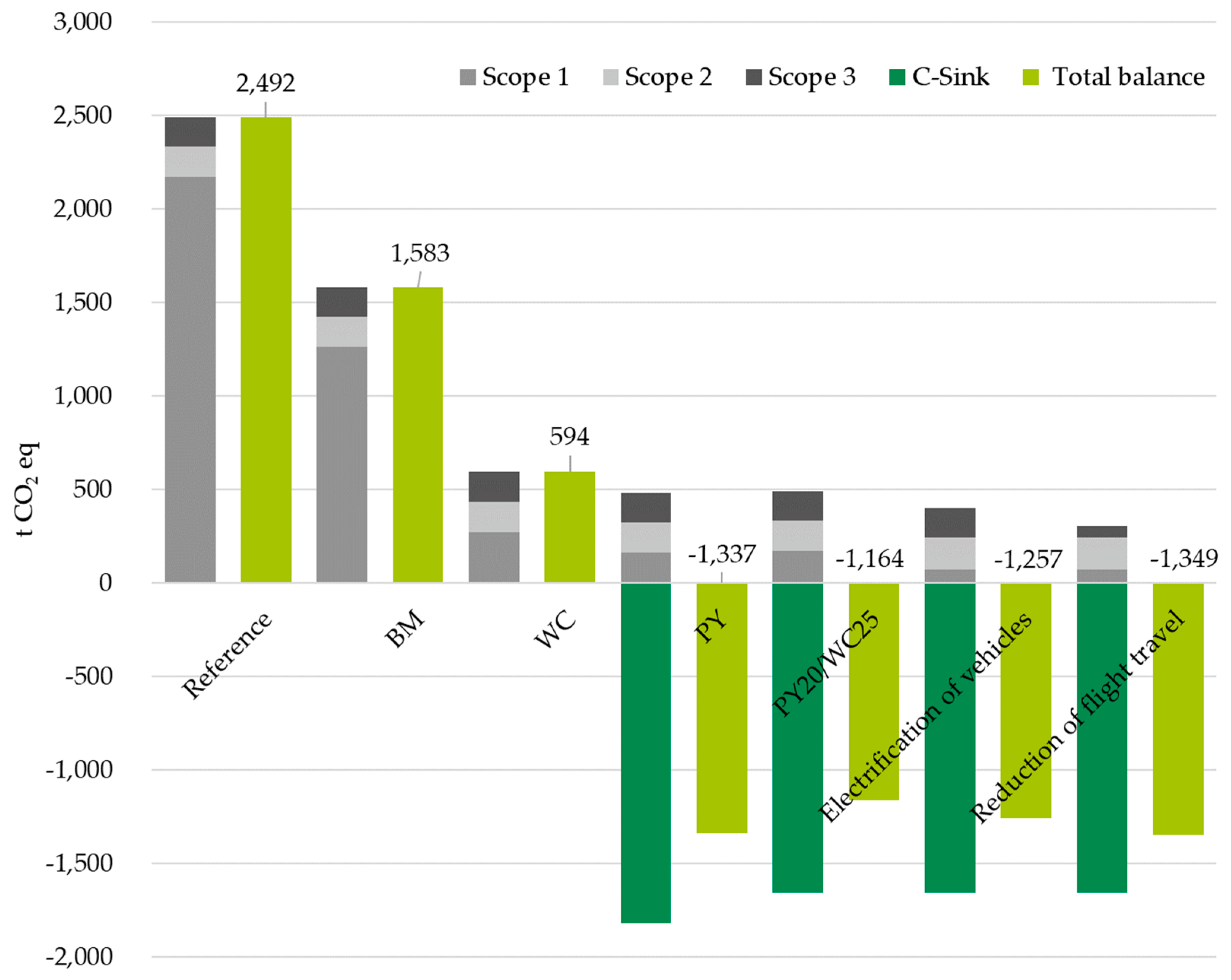

Therefore, the question arises how HGU can become carbon neutral without relying on external carbon offsets, by using their own unique resource basis in the framework of a sustainable circular bioeconomy. To answer this question, the current study assessed in a first step scope 1, 2 and, as far as these are reported, scope 3 emissions of HGU. In addition, the available biomass resource basis was analyzed. We show that even in the best-case scenario, due to the unavoidable emissions, the carbon footprint will not fall below 594 t CO2eq per year. Therefore, carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies need to be implemented if both, the objectives of the state for climate neutrality by 2030 in the administration, and the federal goal of CO2 neutrality by 2045 are to be met. This study identifies reduction potentials and develops cost effective pathways to explore how HGU may become net CO2 negative before the year 2030.

We include the investigation of pyrolyzing local residual biomass to generate thermal energy and biochar, a solid product [

22]. Pyrolysis is a thermal process in which biomass is heated in the absence of oxygen and the resulting syngases (mainly CO, H

2 and CH

4) and oils can be burned e.g. used as fossil fuel substitutes [

23]. As no oxygen is supplied to the process, the carbon cannot be oxidized and C is concentrated during the process and turned into a persistent form[

24]. Depending on the process design, the gases can also be condensed, resulting in a larger fraction of pyrolysis oil and condensing the oil itself, leads to enhanced quality [

25,

26]

This process, known as pyrolysis with carbon capture and storage (PyCCS) or Biochar Carbon Removal (BCR) [

27] offers significant environmental benefits, especially when the biochar is applied in soils such as the reduction of N

2O emissions [

28] and the creation of reliable and permanent carbon sinks [

29,

30]. In contrast to other CDR methods, this technology is permanent, almost irreversible and, above all, technically mature today (technology readiness level TRL 9) [

31,

32].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Overview

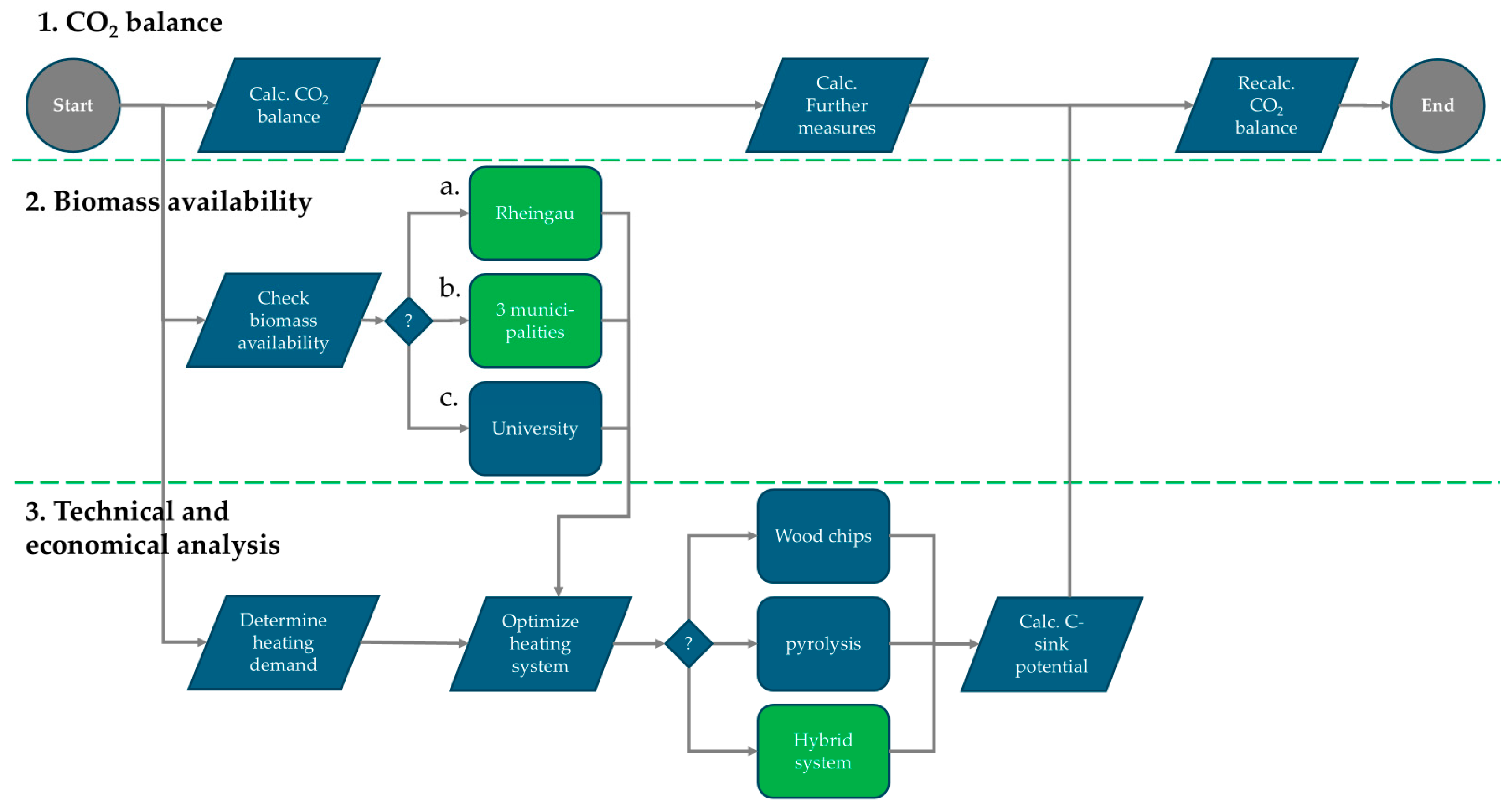

A three-stage approach was employed to assess HGU's potential transition from a CO

2 source to a CO

2 sink (

Figure 1). First, a comprehensive analysis of the university's current greenhouse gas emissions was conducted following the GHG Protocol guidelines, including scope 1-3 emissions (scope 3 where data was available). Second, the theoretical and technical biomass potential with focus on woody residues from viticulture and horticulture was evaluated. To assess biomass availability, three spatial scenarios were established, comprising (a) the HGU activity area, (b) an extended area encompassing HGU and 3 municipalities, and (c) the Rheingau region (

Table 4).

As third step, technical and economic feasibility analyses of different heating systems were performed, with particular attention being paid to hybrid solutions combining pyrolysis with conventional wood chip combustion. The environmental impact was assessed through carbon sink (i.e. BCR-) potential calculations according to European Biochar Certificate (EBC) methodology, while economic viability was evaluated using the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) approach.

Figure 1.

Methodological framework for assessing the transition of Hochschule Geisenheim University from CO2 source to sink. The flowchart illustrates the three-stage analytical approach: (1) GHG emissions analysis, (2) biomass potential assessment, and (3) technical-economic feasibility evaluation of heating systems. Green boxes indicate the identified optimal pathway.

Figure 1.

Methodological framework for assessing the transition of Hochschule Geisenheim University from CO2 source to sink. The flowchart illustrates the three-stage analytical approach: (1) GHG emissions analysis, (2) biomass potential assessment, and (3) technical-economic feasibility evaluation of heating systems. Green boxes indicate the identified optimal pathway.

2.2. Site Description and Infrastucture

Geisenheim University was founded in 1872 by Eduard von Lade as the "Royal College for Fruit and Wine Growing in Geisenheim", with the first buildings dating back to this time. Over time, the university expanded, and since 2013, Geisenheim University has been established as a new type of technical university with PhD granting status. In 2022, the portfolio comprised more than 50 buildings of all types (from transformator housings to institute buildings) from different construction periods and with varying energy efficiency levels. Between 2024 and 2026, 5 new buildings will be added, including training, laboratory and lecture hall buildings.

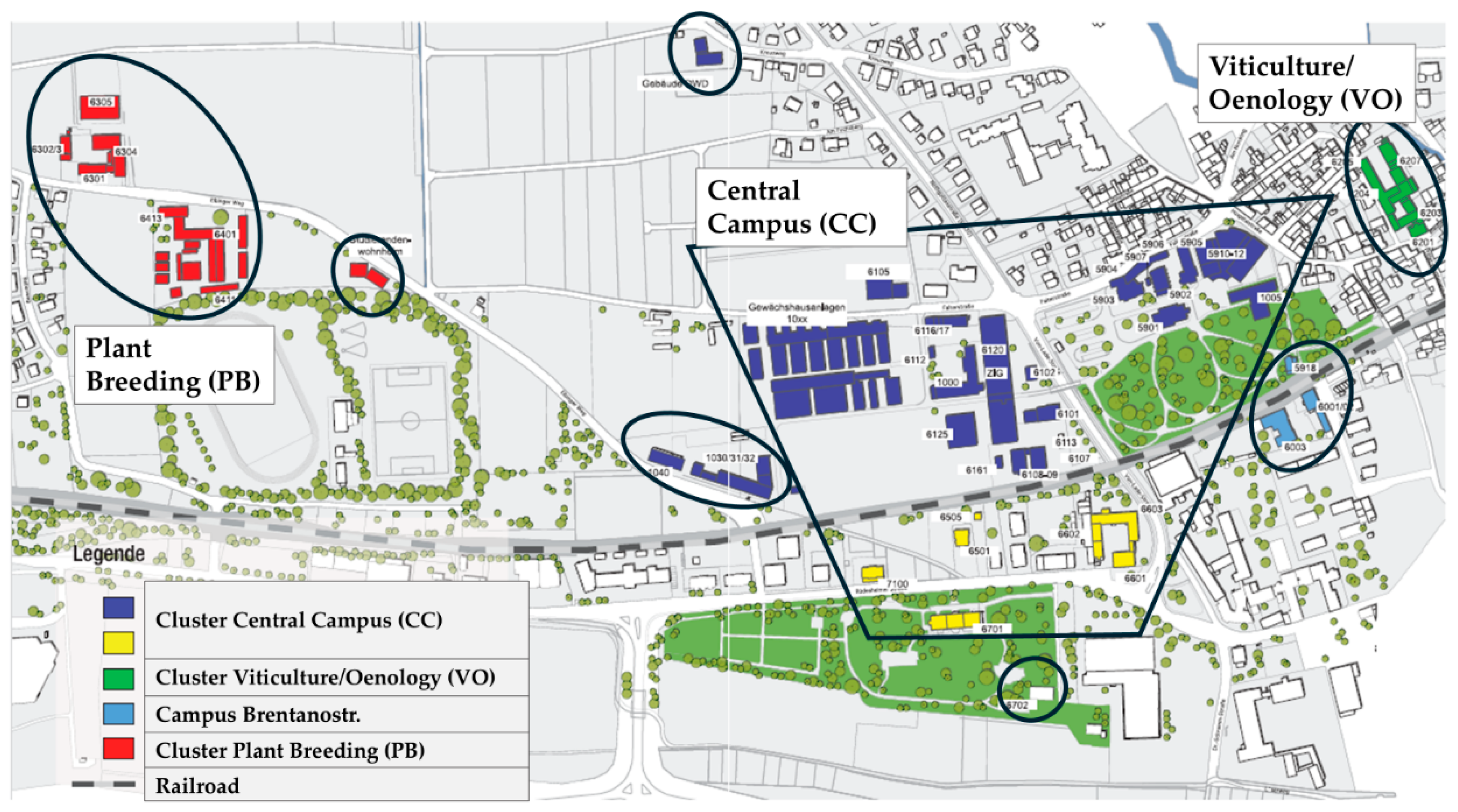

The property is divided into three energy supply clusters. The central campus (cluster CC) represents the largest cluster, generating the highest energy demand for both electricity and heat. This area includes 4,500 m² of greenhouse cultivation area, the largest institute building with laboratories, the majority of administrative buildings and lecture halls, as well as the canteen and library. The viticulture/oenology institute buildings are located to the east (cluster VO), while the Department of Plant Breeding (cluster GB) is situated to the west, both featuring smaller lecture and laboratory facilities. Additional buildings on campus are supplied with heat and electricity on a decentralized basis. Each cluster contains one building with oil or liquified gas heating scheduled for replacement, though these are negligible regarding the CO2 balance (<0.5% of Scope 1).

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of energy supply clusters at Hochschule Geisenheim University campus. The three main clusters are: Central Campus (CC) with primary energy demand, Viticulture/Oenology (VO) in the east, and Grapevine Breeding (GB) in the west. Colored areas represent distinct heating networks with current fossil (also known as natural) gas supply infrastructure.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of energy supply clusters at Hochschule Geisenheim University campus. The three main clusters are: Central Campus (CC) with primary energy demand, Viticulture/Oenology (VO) in the east, and Grapevine Breeding (GB) in the west. Colored areas represent distinct heating networks with current fossil (also known as natural) gas supply infrastructure.

Currently, almost 100% of heat is provided by fossil gas, generated centrally by boilers for each cluster. The heating system in CC will be modelled for renewable heat generation in this study. The other heating systems in clusters VO and GB are assumed to be switched to wood chips (WC) in 2029 due to their expected end of life. After generation, energy is distributed to individual buildings via local heating networks. The university operates four transformer stations: one in each, the grapevine breeding and viticulture clusters; and two on the central campus.

The transmission infrastructure for heat (local heating network) and electricity (transformers and supply lines) is crucial for the university's future energy supply, enabling reduced transmission losses and distribution of self-generated energy through photovoltaic systems on campus.

2.3. System Boundaries and Greenhouse Gas Accounting

The system boundaries for GHG accounting were defined spatially, temporally and operationally. The spatial boundaries include all university-owned and operated facilities within the main campus (approx. 60 hectares), including buildings, technical infrastructure, agricultural areas (vineyards, orchards, experimental fields), campus greenhouses, and university-owned vehicles. The principles of GHG accounting have been established in the Greenhouse Gas Protocol and shaped in the ISO 14064-1:2006, following three central principles: completeness (inclusion of all relevant sources), relevance (consideration of significant gases and activities), and comparability, accuracy, transparency and reproducibility [

33,

34].

Within these boundaries, all activities were categorized according to the GHG Protocol scope definitions:

Scope 1: Direct emissions from university-owned facilities and vehicles

Scope 2: Indirect emissions from purchased electricity and district heating

Scope 3: Other indirect emissions, although it should be noted that scope 3 has not yet been recorded in sufficient detail to enable full reporting

2019 was chosen as the reference year as 2020 and 2021 were characterised by the global COVID-19 pandemic and 2022 by the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine. Due to Germany's dependence on Russian gas, this had a major impact on the supply situation, the global market price and resulted in federal legislative ordinances on energy saving. Osorio et al. [

35] estimate that scope 3 emissions account for 37% of total emissions at higher education institutions. Klein-Banai and Theis [

36] found that an institution's GHG emissions are a function of the size of the institution (building area and number of students), number of laboratories and other factors. For this study, the CO

2 emission factors were taken from the GEMIS database and can be found in

Table 1.

Due to local conditions, some emission sources are particularly relevant or negligible at HGU. For example, the fertile soils in Rheingau make additional fertilization in perennial crops like grapevine and fruits obsolete, so no additional nitrogen fertilizer has been applied since 2018. On the other hand, around 15% of the campus' heating demand is attributed to heating the greenhouses.

Table 1.

CO2-equivalent emission factors and annual energy consumption at Hochschule Geisenheim University in 2019. LNG = liquified natural gas, RE = renewable energy, PV poly. = polycrystal photovoltaic.

Table 1.

CO2-equivalent emission factors and annual energy consumption at Hochschule Geisenheim University in 2019. LNG = liquified natural gas, RE = renewable energy, PV poly. = polycrystal photovoltaic.

| Type |

kg CO2*kWh-1

|

MWh consumed (2019) |

Database |

| Fossil gas |

0.2378 |

8,620 |

GEMIS 5.1 |

| LNG |

0.2378 |

27 |

GEMIS 5.0 |

| Biomethane (mix) |

0.13274 |

0 |

GEMIS 5.0 |

| Electricity (RE, hydropower) |

0.0375 |

4,325 |

Energy Provider |

| Electricity (PV poly.) |

0.04 |

0 |

GEMIS 5.1 |

| Electricity (mix 2019) |

0.411 |

0 |

Statista |

| wood chips |

0.0223 |

0 |

GEMIS 5.1 |

2.4. Biomass Assessment

The assessment of available biomass resources was conducted across three defined collection areas. The first collection area comprised exclusively the biomass available on the Geisenheim University premises and through its activities. The second collection area considered the biomass of the three directly neighbouring municipalities of Rüdesheim, Geisenheim and Oestrich-Winkel (approx. 2,138 ha of vineyards). The third collection area included the total biomass of the "Rheingau" wine-growing region (3,200 ha of vineyards).

The theoretical potential of biomass was determined by combining literature values and on-site pruning residue harvest determined in long term trials by the Institute of Viticulture and the Institute of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition of Geisenheim University [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Technical potential was calculated assuming a mass loss of 19 percent during the collection (baling) of the biomass [

40,

42]. The calculation of the stem wood produced was based on a standing time of 25 years for the vineyards and orchards.

Additional biomass sources were evaluated from bundle wood collections, where non-compostable, woody branches and trunks up to a length of 1.5 m can be handed in by citizens. According to Richter and Raussen [

43] this results in approx. 60 kg/inhabitant/year of material throughout Germany.

"Soft" biomass, such as pomace from wine production, is not considered in this study. In principle, anaerobic digestion of pomace in a biogas plant would enable energy production, but the space required is large, the investment costs high and the associated logistic flows impractical for the densely built-up university [

44,

45].

2.5 Biomass Utilization and Carbon Sink Potential

This study investigated the effects of utilizing local ligneous biomass in a pyrolysis plant on Geisenheim University's carbon balance. The analysis assumed a biochar mass yield of 19% (w/w) at a pyrolysis temperature of 600°C [

46]. Biochar offers a wide range of utilization options. For example, biochar use in agriculture, composting and animal husbandry (feeding, bedding) has already been extensively scientifically examined [

20,

22]. Industrial applications, such as admixture as an additive in concrete, cement and asphalt, reduce the carbon footprint, can enhance material properties of the mixed products (or both) and are practiced by start-up companies [

47,

48].

As the feedstock is not entirely oxidized, the heat yield of pyrolysis plants is lower than that of conventional wood chip heating systems. However, the fixation of the carbon contained in the biomass through pyrolysis effectively enables CO

2 to be removed from the atmosphere. This is achieved by converting the CO

2 originally removed from the atmosphere by the plant into biochar, thereby fixing atmospheric carbon in solid, persistent form [

24]. Provided that it is ensured that the carbon fixed in the biochar does not return to the atmosphere (e.g. through combustion), it is possible to certify and trade the fixed CO

2 in the form of C-sink certificates [

29]. These certificates can be sold in voluntary CO

2 markets or used to offset unavoidable emissions.

According to the calculation method for carbon sinks defined by the European Biochar Certificate [

29] the C-sink potential for biochar produced at Geisenheim University was calculated. This calculation incorporated:

Collection and baling diesel consumption

Transport diesel consumption

Chipping electricity demand

Carbon content of grapevine pruning biochar

Collection and transport carbon efficiency

Biochar production carbon efficiency

Safety margins of 10%

2.6. Heating System Analysis

The heating demand analysis was based on hourly load profiles, which were recorded and analyzed for the years 2018 to 2022. For system optimization, ordered annual load curves were generated to determine base and peak load requirements. For the comparative assessment, six system variants were analyzed. These included a fossil gas system (Reference), a biomethane system (BM), a pure wood chip firing system (WC), a pure pyrolysis system (PY), and two hybrid systems combining pyrolysis base load with wood chip peak load boilers. The hybrid systems were configured as 1.5 MW pyrolysis with 3.0 MW wood chip (PY15/WC30) and 2.0 MW pyrolysis with 2.5 MW wood chip (PY20/WC25) capacity.

Operating parameters for all systems were derived from manufacturer specifications and validated using literature values from Möhren et al. [

49]. The detailed parameters are provided in the

Supplementary Materials,

Table S1, Sheet ‘Technologies’.

Additionally, the analysis included a localized sourcing scenario in which 100% of the biomass feedstock was obtained within a maximum transportation radius of 10 km, thereby substantially reducing fuel costs associated with transportation. The economic analysis followed the methodology of DIN 2067 [

50].

This methodology incorporates investment costs including base installation costs, peripheral equipment and planning. Operating costs were determined by considering maintenance (3% of total investment annually) and fuel costs (0.05 €/kWh for biomass purchased), personnel requirements apply only in proportion to an increased effort with handling residual biomasses in PY scenarios. Additional revenue streams from carbon sink certificates, heat sales, and biochar market value were incorporated into the calculation. A period of 20 years was considered, prices are adjusted with an annual increase of 2%. The calculation sheet with detailed calculations and additional parameters are provided in

Supplementary Table S1, Sheet ‘Calculations’.

The necessary prices for CO

2 to reach the EU’s emission reduction goals were derived from Pietzcker et al. [

51] and revenues for the sequestration of carbon on the voluntary market for BCR were estimated according to Carbonfuture GmbH [

52] to 200 € in 2026. The 2045 price of 300 € is in accordance to the mean of the projected price of a ton of CO

2 removed by direct air capture (DAC) [

53]. The proposed system does not include revenues from the sale of biochar in the first five years, as this serves as an incentive for biomass suppliers to participate in the exchange system in the early years.

The operating costs consist of costs for maintenance and servicing, fuel supply and CO

2 emissions; in the case of pyrolysis solutions, revenues from carbon sink trading are added. The decision variable is the heat generation price (€/MWh), which was calculated according to the widely used levelized cost of energy (LCOE) approach [

54,

55].

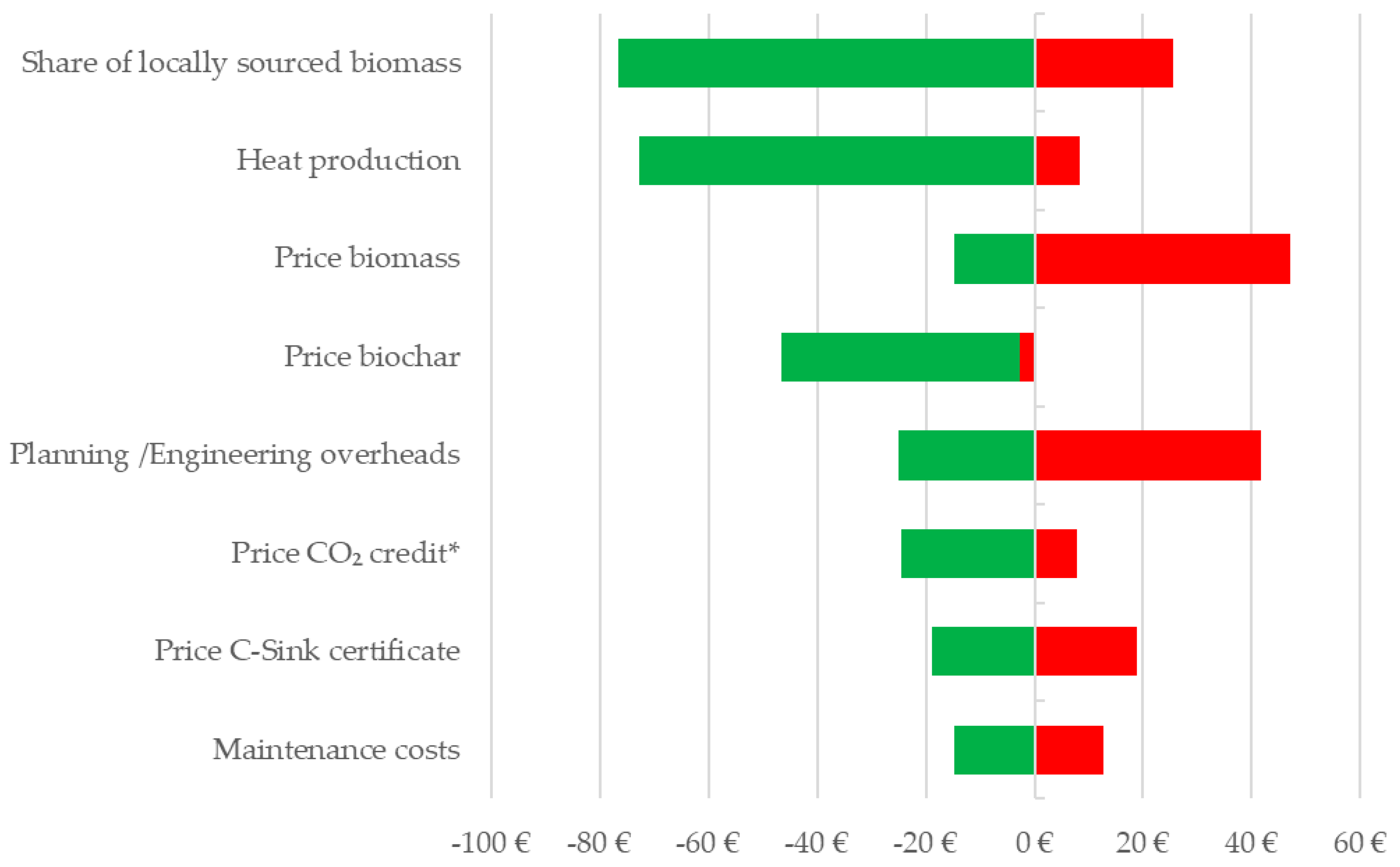

For sensitivity analysis, eight key parameters were identified and varied within defined boundaries as shown in

Table 2. Both one-at-a-time (OAT) and multivariate analyses were performed to assess result robustness.

2.7. C-Sink Calculation

CO

2 certificates usually certify the reduction of emissions compared to a reference scenario and thus contribute to the avoidance of emissions. A fully certified carbon sink guarantees the traceable storage of carbon at all times and results from the active removal of CO

2 from the atmosphere. CDR or Negative emissions (NET) are vital to limit global warming to 2°C [

56]. Carbon sinks are created according to the following scheme:

Removal of CO2 from the atmosphere

Conversion of the carbon into a stable form

Storage in soil or materials

To calculate the carbon footprint of biochar produced at the university, the European Biochar Certificate (EBC) was developed in 2020 in Switzerland as a methodology to determine the sink potential [

29]; EBC C-sink is now hosted by Carbon standards International (1). Following the measurement, reporting, verification (MRV) principles, C-sink certificates are tradable on the voluntary carbon market.

- (1)

2.8. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the robustness of the economic analysis, both one-at-a-time (OAT) and multivariate sensitivity analyses were conducted. For the OAT analysis, eight parameters were identified as potentially influential factors affecting the levelized cost of energy (LCOE). The parameter ranges for the analysis were defined based on current market data and future projections (

Table 2). The PY20/WC25 scenario was selected as the reference case for detailed analysis, as it achieved the highest carbon sequestration rate of 1.656 t CO

2e*year

-1 while maintaining heat production costs at the same level as the Wood chip reference scenario, representing an optimal compromise between environmental and economic objectives.

Table 2.

Parameter ranges for one-at-a-time (OAT) sensitivity analysis of the PY20/WC25 hybrid heating system scenario. Upper and lower boundaries were established based on current market data and future projections. (*) CO2 credit price variation applies exclusively to the pure woodchip (WC) scenario.

Table 2.

Parameter ranges for one-at-a-time (OAT) sensitivity analysis of the PY20/WC25 hybrid heating system scenario. Upper and lower boundaries were established based on current market data and future projections. (*) CO2 credit price variation applies exclusively to the pure woodchip (WC) scenario.

| Parameter |

Lower Boundary |

Upper Boundary |

| Maintenance costs |

-50% |

50% |

| Price C-Sink Certificate |

100 |

300 |

| Price CO2 Credit* |

50 |

190 |

| Planning /Engineering overheads |

-20% |

20% |

| Price biochar |

100 |

500 |

| Price biomass |

0,05 |

0,1 |

| Heat production |

4.500 |

10.000 |

| Share of locally sourced biomass |

0% |

100% |

For the multivariate analysis, parameter combinations were systematically varied within their defined ranges to investigate potential interaction effects. The complete analysis methodology and parameter boundaries are documented in the

Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

3.1. Carbon Footprint Analysis

The analysis of Geisenheim University's carbon footprint revealed that heat generation is the dominant source of emissions throughout the observation period (

Table 3). Despite increasing student and employee numbers, total emissions showed a declining trend from 2019 to 2022. This reduction was particularly pronounced in 2022, mainly due to decreased heating energy consumption following the implementation of energy saving measures in response to the energy price crisis / the Ukrainian war. The pandemic years 2020 and 2021 showed significantly reduced scope 3 emissions due to travel restrictions.

These findings identify heat generation as the key leverage point for achieving the university's emission reduction goals.

Table 3.

Annual greenhouse gas emissions of Hochschule Geisenheim University from 2018 to 2022, categorized by emission scopes according 2.3. Values are presented in t CO2e*year-1, with percentage distribution across scopes. Institutional metrics including student numbers, employee count, and facility area are provided for contextual reference.

Table 3.

Annual greenhouse gas emissions of Hochschule Geisenheim University from 2018 to 2022, categorized by emission scopes according 2.3. Values are presented in t CO2e*year-1, with percentage distribution across scopes. Institutional metrics including student numbers, employee count, and facility area are provided for contextual reference.

| Scope |

|

2018 |

% |

2019 |

% |

2020 |

% |

2021 |

% |

2022 |

% |

| 1 |

Heat generation |

1,965 |

|

2,071 |

|

2,023 |

|

2,179 |

|

1,628 |

|

| 1 |

Vehicle Fuels |

99 |

90.3 |

100 |

87.2 |

71 |

94.2 |

70 |

95.0 |

71 |

90.9 |

| 2 |

Electricity |

128 |

5.6 |

162 |

6.5 |

117 |

5.3 |

110 |

4.7 |

118 |

6.3 |

| 3 |

Air travel |

86 |

|

147 |

|

8 |

|

3 |

|

46 |

|

| |

Water |

6 |

4.0 |

11 |

6.3 |

5 |

0.6 |

4 |

0.3 |

5 |

2.7 |

| |

Total |

2,285 |

|

2,502 |

|

2,234 |

|

2,366 |

|

1,868 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Students |

1,655 |

|

1,750 |

|

1,750 |

|

1,750 |

|

1,750 |

|

| |

Employees |

404 |

|

450 |

|

542 |

|

542 |

|

542 |

|

| |

area (m2) |

50,579 |

|

50,579 |

|

50,579 |

|

50,579 |

|

50,579 |

|

3.2. Biomass Availability

The assessment of biomass resources across the three defined collection areas revealed substantial differences in potential availability (

Table 4).

The university grounds alone provide a technical biomass potential of 143.6 t DM*year-1. Expanding the collection radius to include the three neighboring municipalities of Rüdesheim, Geisenheim, and Oestrich-Winkel increased the technical biomass potential to 5,651 t DM*year-1. The full Rheingau region showed a technical biomass potential of 8,670 t DM*year-1.

These findings indicate that biomass availability within a 10-km radius of the university campus is sufficient to sustain the proposed heating systems, with the potential to establish multiple comparable units before encountering biomass supply limitations. The proximity of the biomass sources to the university ensures favorable transport logistics and maintains low associated emissions.

Table 4.

Technical biomass potential from viticulture residues and municipal biomass collection across Rheingau region municipalities. Data includes municipality characteristics (population, total area), vineyard area and calculated biomass availability from different sources. All biomass values are reported as dry matter (DM) in metric tons per year.

Table 4.

Technical biomass potential from viticulture residues and municipal biomass collection across Rheingau region municipalities. Data includes municipality characteristics (population, total area), vineyard area and calculated biomass availability from different sources. All biomass values are reported as dry matter (DM) in metric tons per year.

| Municipality |

Inhabitants |

total area (km2) |

Vinyard area (ha)* |

Biomass viticulture (t) |

Mun. biomass collection (t) |

Biomass total (t) |

| HGU |

n.a. |

n.a. |

33 |

68 |

76 |

144 |

| Rüdesheim |

10,054 |

51.41 |

652 |

1,344 |

302 |

1,646 |

| Geisenheim |

11,699 |

40.34 |

512 |

1,055 |

351 |

1,406 |

| Oestrich-Winkel |

11,873 |

59.51 |

1,019 |

2,100 |

356 |

2,457 |

| Subtotal 3 municipalities |

151 |

2,183 |

4,567 |

1,009 |

5,651 |

| Kiedrich |

4,075 |

12.34 |

157 |

323 |

122 |

445 |

| Eltville |

8,476 |

10.08 |

128 |

264 |

254 |

518 |

| Martinsthal |

1,226 |

4.73 |

60 |

124 |

37 |

160 |

| Rauenthal |

1,800 |

7.27 |

92 |

190 |

54 |

244 |

| Erbach |

3,429 |

12.69 |

161 |

332 |

103 |

435 |

| Hattenheim |

2,181 |

12.00 |

152 |

314 |

65 |

379 |

| Walluf |

5,523 |

6.75 |

86 |

176 |

166 |

342 |

| Lorch |

4,017 |

54.43 |

182 |

375 |

121 |

496 |

| Total Rheingau (all municip.) |

272 |

3,200 |

6,664 |

1,931 |

8,670 |

3.3. Heating System Performance

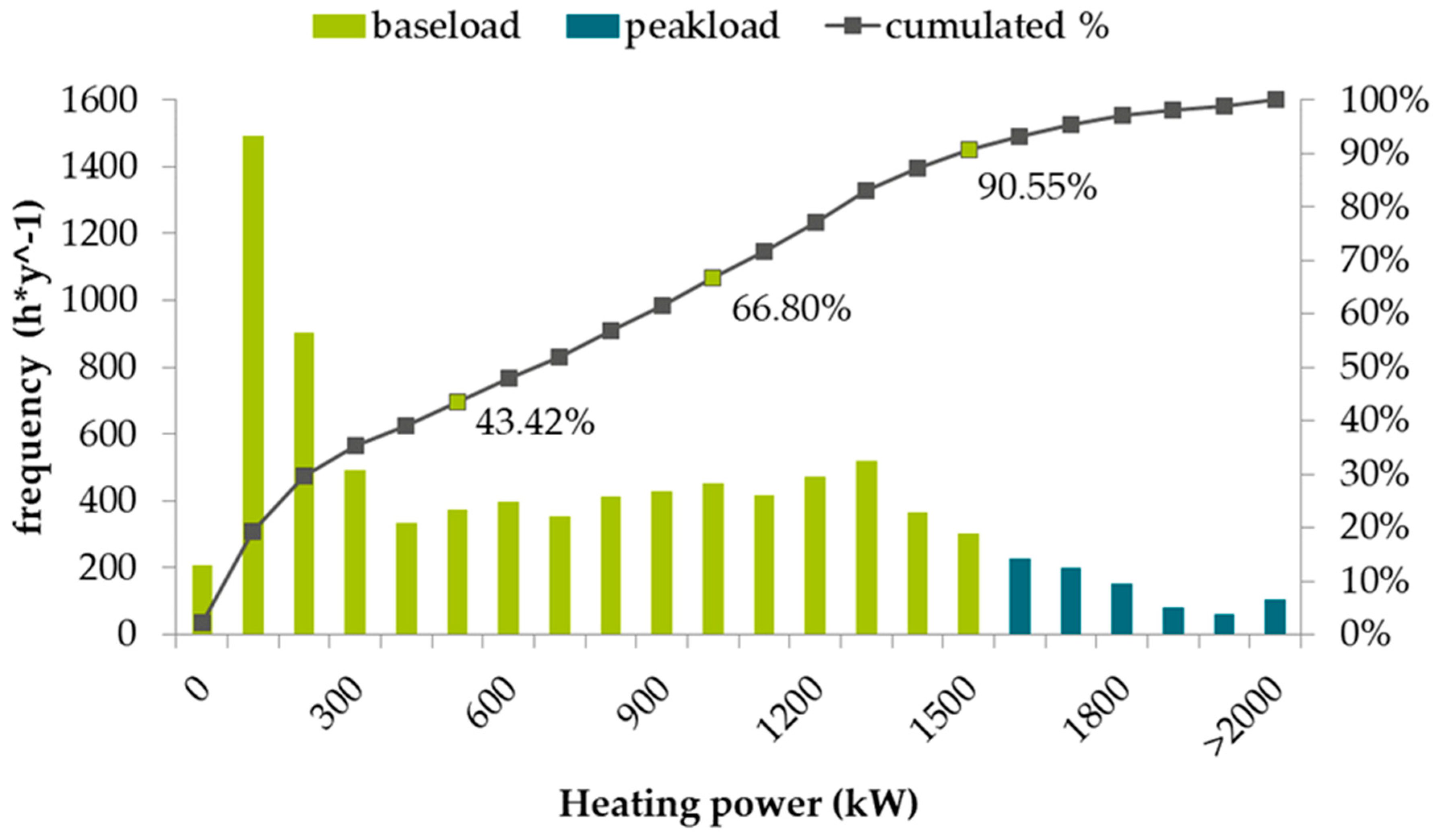

Analysis of the ordered load profiles revealed that the heating demand rarely reached maximum capacity. The peak load of 3.24 MW occurred only once during the observation period (

Table 5), while 90.55 % of the heating demand was below 1.5 MW (

Figure 3).

Table 5.

Historical heating load analysis and proposed generation allocation for the Central Campus cluster (2018-2022). Data shows power demand distribution and corresponding energy consumption across load ranges, with mean values and proposed technology assignment (PY = pyrolysis, WC = wood chip combustion). All power values in kW, energy values in kWh. n.a. = not applicable.

Table 5.

Historical heating load analysis and proposed generation allocation for the Central Campus cluster (2018-2022). Data shows power demand distribution and corresponding energy consumption across load ranges, with mean values and proposed technology assignment (PY = pyrolysis, WC = wood chip combustion). All power values in kW, energy values in kWh. n.a. = not applicable.

| |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Mean |

Proposed |

| Power |

Energy |

Energy |

Energy |

Energy |

Energy |

Energy |

generation |

| 500 |

630,157 |

624,149 |

750,404 |

453,636 |

629,973 |

617,664 |

PY |

| 1,000 |

1,356,316 |

1,556,154 |

1,670,776 |

1,663,317 |

1,616,567 |

1,572,626 |

PY |

| 1,500 |

2,330,150 |

2,565,807 |

2,450,804 |

2,628,596 |

1,731,281 |

2,341,328 |

PY |

| 2,000 |

1,333,699 |

1,222,191 |

914,787 |

1,303,106 |

629,572 |

1,080,671 |

PY |

| 3,000 |

316,658 |

228,003 |

43,074 |

212,201 |

40,068 |

168,001 |

WC |

| 4,500 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3,245 |

0 |

649 |

WC |

| Total energy |

5,966,980 |

6,194,804 |

5,829,846 |

6,264,100 |

4,647,460 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

| Min power |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

| Max power |

2,742.5 |

2,866.3 |

2,469.2 |

3,244.5 |

2,457.3 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

| Av. power |

681.6 |

707.2 |

665.5 |

715.1 |

530.5 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

| Med. power |

575 |

654 |

602 |

739 |

413 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Figure 3.

Annual heat load duration curve for the Central Campus cluster in 2019. The curve demonstrates that 90.55% of the annual heating demand occurs below 1.5 MW capacity, with peak loads reaching a maximum of 2.87 MW. This load distribution pattern supports the design rationale for a hybrid heating system.

Figure 3.

Annual heat load duration curve for the Central Campus cluster in 2019. The curve demonstrates that 90.55% of the annual heating demand occurs below 1.5 MW capacity, with peak loads reaching a maximum of 2.87 MW. This load distribution pattern supports the design rationale for a hybrid heating system.

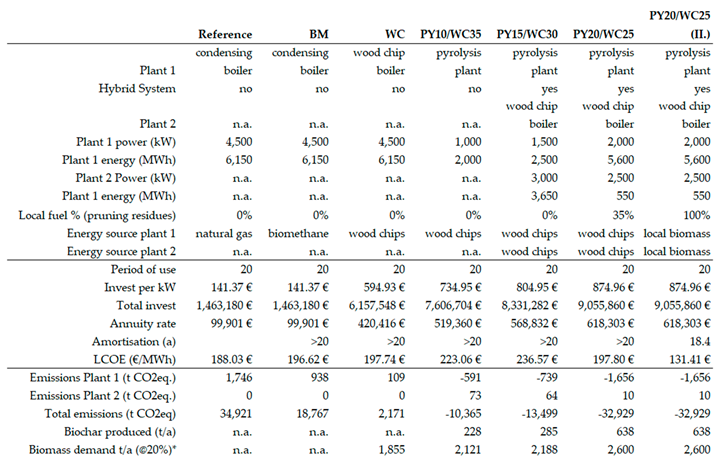

3.4. Optimized Heating System

The comparative analysis of different heating systems revealed distinct performance profiles (Table 7). Systems incorporating pyrolysis demonstrated significant carbon dioxide removal potential, but economic performance varied considerably. The reference and biomethane (BM) variants, while technically simple, showed high LCOE at 188.03 and 196.62 €/MWh respectively. Pure wood chip firing (WC) resulted in an LCOE of 197.74 €/MWh.

The hybrid systems combining pyrolysis and wood chip boilers showed varying performance levels depending on their configuration. While the PY10/WC35 and PY15/WC30 configurations achieved carbon removal of -10,365 and -13,499 t CO2e, respectively, over their service life, their LCOE remained high at 223.06 and 236.57 €/MWh. The PY20/WC25 configuration emerged as particularly promising, achieving the highest carbon dioxide removal (-32,929 t CO2e) while maintaining an LCOE of 197.80 €/MWh, comparable to the pure wood chip system, when partially supplied with residual biomass.

Most notably, when completely operated with locally sourced biomass (PY20/WC25 II), this system showed substantially improved economics, with LCOE being reduced to 131.93 €/MWh. The annual biochar production of 638 t would require approximately 2,600 t of biomass input, which aligns with the identified local biomass availability.

3.5. C-Sink Calculation

According to the calculation method for carbon sinks defined in [

29], the C-sink potential for biochar produced at Geisenheim University was calculated to be 70.75 %. For parameters used see

Table 4, entire calculation is provided in the supplementary materials, table S1, sheet ‘C-Sink potential’. This means that after calculating the carbon expenditure (CE) for providing the biomass and producing the biochar, 1,000 kg of BC contain 707.5 kg of net sequestered carbon or 2,594 kg CO

2e of tradeable C sinks. Depending on the capacity of the pyrolysis plant, this results in up to 1,656 t C-sink certificates or 638 t of BC annually. The certification of the C-sinks can be achieved through a contractual agreement with the biomass supplier. He receives an equivalent in biochar for the biomass supplied, which must then be mixed with pomace or co-composted and incorporated into the supplier's agricultural soil to convert the sink potential into a verified C-sink.

3.6. Economic Analysis and Sensitivity Assessment

The economic feasibility analysis revealed significant variations in investment requirements and operating costs across the systems (

Table 6). Initial investments ranged from 141.37 €/kW for conventional systems to 874.96 €/kW for pyrolysis-based configurations, resulting in total investments between 1.46 and 9.06 million euro. The amortization period of 18.5 years for biomass-based systems reflects the significant initial investment but demonstrates long-term economic viability when considering the complete lifecycle costs and revenues.

The sensitivity analysis identified the share of locally sourced biomass and heat production as the most influential parameters affecting the LCOE (Figure 5). A shift from 0% to 100% local biomass resulted in a LCOE reduction of 76.61 €/MWh from the base case. Similarly, increasing heat production from 4,500 to 10,000 MWh/year decreased the LCOE by 72.67 €/MWh. Other parameters showed less significant impacts: planning and engineering overheads demonstrated a moderate impact range of -24.98 to +41.63 €/MWh, while maintenance costs showed the lowest sensitivity with deviations between -14.74 and +12.74 €/MWh from the base case.

Table 6.

Technical-economic comparison of heating system alternatives following DIN 2067 methodology. Analysis includes system specifications, investment requirements, operational parameters, and environmental impact metrics across different technology configurations. PY = Pyrolysis, WC = Wood Chips, BM = Biomethane, *water content.

Table 6.

Technical-economic comparison of heating system alternatives following DIN 2067 methodology. Analysis includes system specifications, investment requirements, operational parameters, and environmental impact metrics across different technology configurations. PY = Pyrolysis, WC = Wood Chips, BM = Biomethane, *water content.

Table 7.

Parameters and emission factors used in carbon sink potential calculations for biochar production from vineyard pruning residues. Values include operational energy requirements, carbon content specifications, and efficiency factors according to the European Biochar Certificate methodology [

29]. CE = carbon expenditure.

Table 7.

Parameters and emission factors used in carbon sink potential calculations for biochar production from vineyard pruning residues. Values include operational energy requirements, carbon content specifications, and efficiency factors according to the European Biochar Certificate methodology [

29]. CE = carbon expenditure.

| Parameter |

Type |

Unit |

Amount |

Source |

| collecting & baling |

diesel |

liter |

5.5 |

[57] |

| transport 10 km |

diesel |

liter |

8.6 |

[57] |

| chipping |

electricity |

kWh |

30 |

own measurements |

| Carbon content grapevine prunings |

biochar |

% |

75 |

[39,58] |

| CE collection and transport |

n.a. |

% |

1.58 |

Suppl. T1 Sheet ‘C-Sink Potential’ |

| CE production biochar |

n.a. |

% |

2.26 |

Suppl. T1 Sheet ‘C-Sink Potential’ |

| CE safety margin |

n.a. |

% |

0.38 |

Suppl. T1 Sheet ‘C-Sink Potential’ |

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis results visualized as a tornado diagram showing the impact of key parameters on the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) for the PY20/WC25 scenario. Parameters are ranked by their influence on LCOE, with locally sourced biomass share and heat production emerging as the most significant factors. (*) CO2 credit price applies only to wood chip (WC) system.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis results visualized as a tornado diagram showing the impact of key parameters on the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) for the PY20/WC25 scenario. Parameters are ranked by their influence on LCOE, with locally sourced biomass share and heat production emerging as the most significant factors. (*) CO2 credit price applies only to wood chip (WC) system.

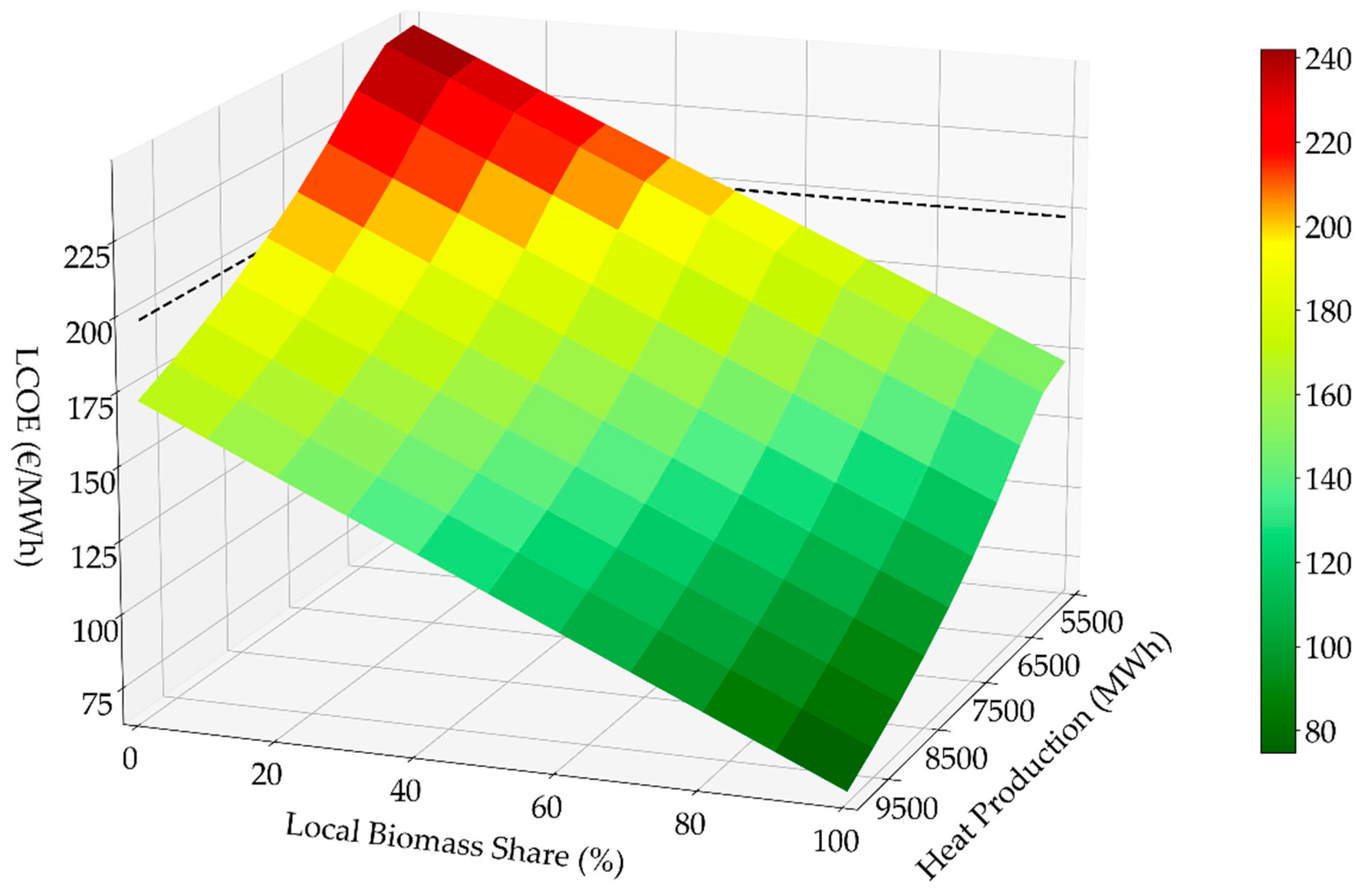

The surface plot demonstrates the combined effect of heat production and locally sourced biomass share on the LCOE. The lowest LCOE values (75.88 €/MWh) were observed at maximum heat production (10,000 MWh) and 100% locally sourced biomass, while the highest values (256.42 €/MWh) occurred at minimum heat production (5,500 MWh) and 0% locally sourced biomass. A clear gradient can be observed, showing that increasing either parameter leads to improved economic performance, with the steepest improvements occurring in the transition from 0% to 50% local biomass share.

For the multivariate analysis, more conservative assumptions were applied to test system robustness. These included additional infrastructure costs of 1,000,000 € for increased heat production capacity and lower revenue projections from carbon sink certificates (100 € fixed instead of increasing to 300 €) and biochar sales (200 € per ton). Even under these conservative conditions, the analysis revealed that the lowest LCOE values (66.34 €/MWh) were achieved with maximum heat production and 100% locally sourced biomass, while the highest values (248.00 €/MWh) occurred at minimum heat production and 0% locally sourced biomass.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional surface plot illustrating the combined effects of heat production capacity and locally sourced biomass percentage on the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE). The plot reveals a clear gradient with optimal economic performance (lowest LCOE) achieved at maximum heat production and 100% local biomass utilization.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional surface plot illustrating the combined effects of heat production capacity and locally sourced biomass percentage on the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE). The plot reveals a clear gradient with optimal economic performance (lowest LCOE) achieved at maximum heat production and 100% local biomass utilization.

3.7. Reduction Pathway

As can be seen in

Table 3, the purchase of (renewable) electricity only accounts for around 4.7-6.5% of the carbon footprint. With a factor of 0.0375 kg CO

2 *kWh

-1 from the University’s energy contractor, measures like the expansion of PV generation capacities, which make sense from an economic and sustainability perspective, have no relevant influence on the CO

2 balance, thus were not the objective of this study. By far the largest proportion is influenced by the generation of heat. Accordingly, only the carbon relevant measures are dealt with in this section. The measures shown in

Figure 4 are briefly described in the following.

Neither the Biomethane nor the wood chip scenario are able to reduce the university’s CO

2 balance to near zero, leaving 594 tons of unavoidable CO

2 emissions, with 274 t in Scope 1, and 162 t and 158 t in Scope 2 and 3, respectively. This clearly contravenes the Hessian state government's plan for achieving CO

2-neutral state administration by 2030 and, in view of the time horizon left for the use of heat generators (20 years), most likely also contravenes the German climate targets for CO

2 neutrality by 2045. Since PY20/WC25 is the most cost-effective solution (

Table 6), the bivalent system should be selected in view of the only slightly higher sink capacity of the “pure” PY variant.

Figure 6.

Projected carbon balance trajectory for Hochschule Geisenheim University following implementation of strategic emission reduction measures. The graph shows the transition from current emissions (2019 baseline) through various intervention stages, demonstrating the potential pathway to achieve carbon negativity through hybrid pyrolysis-woodchip heating system implementation.

Figure 6.

Projected carbon balance trajectory for Hochschule Geisenheim University following implementation of strategic emission reduction measures. The graph shows the transition from current emissions (2019 baseline) through various intervention stages, demonstrating the potential pathway to achieve carbon negativity through hybrid pyrolysis-woodchip heating system implementation.

Electrification of Vehicle Fleet

The electrification of the university fleet has the potential to reduce CO2 emissions by 70 to 100 tons annually within Scope 1. However, this transition is expected to incur a marginal increase of 8 tons within Scope 2, attributable to the increasing electricity consumption associated with the process. In the immediate future, the feasibility of electrification is primarily applicable to the university’s car fleet, with the substitution of heavy machines like tractors being achievable in the mid-term. Given the prevalence of smaller agricultural machinery in viticulture and fruit growing, promising solutions exist for electrified tractors (e.g., Fendt e100 Vario, Monarch MK-V) to commence operations in the later 2020s and be fully deployed in the 2030’s.

Avoidance of Medium-Haul Flights

The COVID-19 pandemic has made it clear that entire conferences can also be held online. Assuming that half of medium-haul flights and a third of long-haul flights are cancelled, a saving of 67 t CO2 can be achieved within Scope 3.

4. Discussion

Key Findings

This study demonstrates that Higher Education Institutions with access to agricultural and municipal residual biomass can establish economically viable carbon removal systems while meeting their heating demands. The proposed hybrid pyrolysis-woodchip system achieves three crucial objectives simultaneously: It provides renewable heat generation, creates certified and tradeable carbon sinks, and produces valuable biochar for local agricultural applications. Most notably, when operated with locally sourced biomass, the system achieves lower levelized costs of energy (131.93 €/MWh) compared to conventional heating systems while removing substantial amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere (-32,929 t CO2e over service life). This shows that BCR technology can be implemented cost-effectively when integrated into existing infrastructure needs.

Comparison with Similar Studies

The findings can be compared with and extended upon previous research on carbon neutrality initiatives in higher education institutions. The transition of Leuphana University Lueneburg towards climate neutrality was documented by Opel et al. [

5], where significant emission reductions through conventional measures were achieved. In this study, however, it is demonstrated that, beyond carbon neutrality, also a carbon negative status can be achieved through innovative technological integration.

In the economic analysis by Latter and Capstick [

6], where UK universities' climate emergency declarations were examined, it was found that most institutions struggle with the financial feasibility of carbon reduction measures. In contrast, it is demonstrated by our hybrid pyrolysis-woodchip system that cost competitiveness (131.93 €/MWh with local biomass) can be achieved, while additional carbon removal benefits are provided, indicating a viable pathway for institutions with access to biomass resources.

The scope 1 emissions, particularly from heating, were identified as a major challenge in the comprehensive review of Valls-Val and Bovea [

7] of 35 higher education institutions' carbon footprints. These findings are confirmed by our observations, but it is uniquely demonstrated how these emissions can be transformed into carbon sinks through pyrolysis technology. This approach differs from conventional offsetting strategies that were criticized by Haya et al. [

15], as verifiable, permanent carbon removal within the institution's operational boundary is created.

The economic viability of the proposed system (18.5-year amortization period) can be favorably compared with other institutional carbon reduction measures. Longer payback periods for conventional renewable energy installations at universities were reported by Mendoza-Flores et al. [

9]. However, it is demonstrated by this study that the business case can be improved through integration of heat generation with carbon removal while environmental benefits are delivered by the use of biochar in agriculture such as reduced nitrate leaching to groundwaters or reduced nitrous oxide emissions [

28]. Such indirect effects on GHG balances were not part of this assessment.

This work also contributes to the broader discussion of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) implementation pathways. While Young et al. [

53] project high costs for direct air capture technologies (

$200-600/tCO

2), our pyrolysis-based approach achieves removal at lower costs while providing additional benefits through heat generation and biochar utilization. This supports Werner et al.’s [

27] assertion that biomass pyrolysis systems offer significant potential for limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

Cost and Price Estimations

The economic viability of CDR systems faces significant uncertainties regarding future price developments. Current forecasts for carbon removal costs vary widely between 100 and 600 US dollars per ton of CO

2e [

53]. While optimistic studies project prices below 100 US dollars, such scenarios could create problematic market incentives if removal costs fall below emission costs [

56]. Our sensitivity analysis demonstrates that the system's economic viability is less dependent on carbon prices than previously assumed, with local biomass sourcing and heat utilization being the key economic drivers. The cost calculations following DIN 2067 may be conservative, particularly regarding maintenance costs and peripheral equipment for pyrolysis systems, as they are derived from conventional heating systems.

Technical and Methodological Limitations

Several methodological and data-related limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. The biomass availability assessment relies on literature values and limited field measurements, which may not fully capture local variations in biomass productivity [

40,

59]. While pruning residue quantities were validated through long-term trials at HGU, the technical collection potential could vary significantly based on vineyard management practices and actual collection efficiency [

38,

60]. The assumed collection loss of 19% represents an average value that may fluctuate seasonally [

37,

61].

The establishment and maintenance of reliable biomass supply chains presents additional challenges. Initial stakeholder communications indicates strong interest in the circular biochar utilization model, as participants would benefit from reduced disposal costs and improved soil quality through biochar application, but requires consistent feedstock quality standards [

22,

62]. A particular consideration in viticulture-derived feedstocks is the presence of copper from plant protection treatments, which are commonly applied in both conventional and organic vineyard management. Analysis of pruning residues showed copper concentrations between 8.5 and 19.2 mg*kg

-1. While these concentrations are expected to increase during pyrolysis due to mass reduction and element conservation, the projected copper content in the resulting biochar would remain below the regulatory threshold of 70 mg*kg

-1 [

63,

64].

The successful operation of the system depends on establishing effective quality control systems and biochar application protocols that comply with evolving regulatory frameworks.

Our economic analysis is based on current market prices and technological parameters, with projections extending to 2045. While sensitivity analyses were conducted, long-term price developments for all carbon removal certificates, biochar and other resources remain uncertain. The investment cost calculations for pyrolysis systems are derived from conventional heating system standards (DIN 2067), which may not fully capture specific maintenance requirements or peripheral equipment needs of pyrolysis technology.

While current German regulations on biochar soil application are more restrictive than EU standards, the system's biochar will be produced at >550°C from pruning residues and is expected to result in H/C

org ratio of 0.17, thus meets internationally recognized stability criteria [

23,

65,

66].

Risk of Mitigation Deterrence and Increased Macroeconomic Costs

The deployment of the sink option by BC or any other CDR technology generally poses the risk of mitigation deterrence [

67]. Especially the petrochemical industry employs Circular Carbon strategy approaches to mitigate the need for ambitious emission reductions [

68]. Governments that endorse technological openness and rely on future measures, rather than actively shaping pathways toward a far below 2°C future, risk burdening economy and society with unnecessarily high costs through their policy of postponement [

69,

70].

5. Conclusions

The implementation of carbon sinks has been identified as indispensable for atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. Higher education institutions and other public institutions can play an important role as ideal testing grounds for sustainable transitions, combining both institutional responsibility and technical capabilities.

The results demonstrate that heat production, carbon sink certificate generation, and biochar creation from local biomass can be achieved while maintaining economic viability at Geisenheim University. Although CDR implementation costs currently exceed conventional emission offsetting, this difference maintains incentives for emission reduction measures, ensuring that carbon sinks are reserved for genuinely unavoidable emissions.

Several research priorities have been identified for future investigation. Governmental Public institutions need to develop comprehensive understanding of carbon sinks to facilitate their timely integration into respective net-zero strategies. Investigation of synergies with additional institutional sustainability initiatives and scalability assessments for broader public institution implementation have been determined as necessary next steps.

The findings align with both Hesse's state objectives for climate-neutral administration by 2030 and federal neutrality goals by 2045, providing an evidence-based implementation framework for other institutions. Our results demonstrate that economic viability and ambitious climate action can be achieved through integrated technological solutions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K., G.A-K.; methodology, C.K., M.W., G.A-K. .; software, G.A-K.; validation, C.K., M.W., G.A-K.; formal analysis, G.A-K.; investigation, G.A-K.; resources, G.A-K, C.K.; data curation, G.A-K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A-K.; writing—review and editing, C.K., M.W.; visualization, G.A-K.; supervision, C.K.; project administration, G.A-K.; funding acquisition, C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hessian Ministry of Higher Education, Research, Science and the Arts, project “Facing Compensation” (Grant No. K15/02.P7P2). C.K. gratefully acknowledges funding by the BMBF consortium project “PyMiCCS” (Grant No. 01LS2109C) within the CDRterra program that allows results like those presented here to be entered into CDRSynTra assessment matrices.

Acknowledgments

Department of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition; Department of General and Organic Viticulture; Department of Pomology; Department of Applied Ecology; Department of Strategic University Development and Sustainability.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

-

Sustainable Development Goals in Higher Education; Springer Cham, Ed. International Joint Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Rio de Janeiro; Springer, 2020.

- Findler, F.; Schönherr, N.; Lozano, R.; Reider, D.; Martinuzzi, A. The impacts of higher education institutions on sustainable development. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2019, 20, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavič, P.; Lukman, R. Review of sustainability terms and their definitions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2007, 15, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuso Nerini, F.; Sovacool, B.; Hughes, N.; Cozzi, L.; Cosgrave, E.; Howells, M.; Tavoni, M.; Tomei, J.; Zerriffi, H.; Milligan, B. Connecting climate action with other Sustainable Development Goals. Nature Sustainability 2019, 2, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opel, O.; Strodel, N.; Werner, K.F.; Geffken, J.; Tribel, A.; Ruck, W. Climate-neutral and sustainable campus Leuphana University of Lueneburg. Energy 2017, 141, 2628–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latter, B.; Capstick, S. Climate Emergency: UK Universities' Declarations and Their Role in Responding to Climate Change. Frontiers in Sustainability 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls-Val, K.; Bovea, M.D. Carbon footprint in Higher Education Institutions: a literature review and prospects for future research. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 2523–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganathan, J.; Corbier, L.; Bhatia, P.; Schmitz, S.; Gage, P.; Oren, K. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard, Washington, DC, 2004. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg-protocol-revised.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Mendoza-Flores, R.; Quintero-Ramírez, R.; Ortiz, I. The carbon footprint of a public university campus in Mexico City. Carbon Management 2019, 10, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, G.; LaPoint, T. Comparing Greenhouse Gas Emissions across Texas Universities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clabeaux, R.; Carbajales-Dale, M.; Ladner, D.; Walker, T. Assessing the carbon footprint of a university campus using a life cycle assessment approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 273, 122600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Msigwa, G.; Yang, M.; Osman, A.I.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Strategies to achieve a carbon neutral society: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2277–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Andara, A.; Río-Belver, R.M.; Rodríguez-Salvador, M.; Lezama-Nicolás, R. Roadmapping towards sustainability proficiency in engineering education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2018, 19, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, H.N.; Pettersen, J.; Solli, C.; Hertwich, E.G. Investigating the Carbon Footprint of a University - The case of NTNU. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 48, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haya, B.; Cullenward, D.; Strong, A.L.; Grubert, E.; Heilmayr, R.; Sivas, D.A.; Wara, M. Managing uncertainty in carbon offsets: insights from California’s standardized approach. Climate Policy 2020, 20, 1112–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haya, B.K.; Evans, S.; Brown, L.; Bukoski, J.; van Butsic; Cabiyo, B.; Jacobson, R.; Kerr, A.; Potts, M.; Sanchez, D.L. Comprehensive review of carbon quantification by improved forest management offset protocols. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2023, 6. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.; Kollmuss, A. Perverse effects of carbon markets on HFC-23 and SF6 abatement projects in Russia. Nature Climate Change 2015, 5, 1061–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill-Wiehl, A.; Kammen, D.; Haya, B. Cooking the books: Pervasive over-crediting from cookstoves offset methodologies, 2023.

- Lal, R.; Smith, P.; Jungkunst, H.F.; Mitsch, W.J.; Lehmann, J.; Nair, P.R.; McBratney, A.B.; Moraes Sá, J.C. de; Schneider, J.; Zinn, Y.L.; et al. The carbon sequestration potential of terrestrial ecosystems. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2018, 73, 145A–152A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.-P.; Kammann, C.; Hagemann, N.; Leifeld, J.; Bucheli, T.D.; Sánchez Monedero, M.A.; Cayuela, M.L. Biochar in agriculture – A systematic review of 26 global meta-analyses. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessisches Ministerium der Finanzen. Der CO2 Fußabdruck der hessischen Landesverwaltung: CO2 Bilanz Verfahrensbeschreibung, Wiesbaden, 2020 (accessed on 19 December 2022).

-

Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation; Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S., Eds., 2. Auflage; Taylor & Francis Ltd.: Sterling, 2015. ISBN 9780415704151.

- Jäger, N.; Conti, R.; Neumann, J.; Apfelbacher, A.; Daschner, R.; Binder, S.; Hornung, A. Thermo-Catalytic Reforming of Woody Biomass. Energy & Fuels 2016, 30, 7923–7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, D.A.; Brown, R.C.; Amonette, J.E.; Lehmann, J. Review of the pyrolysis platform for coproducing bio-oil and biochar. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2009, 3, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papari, S.; Hawboldt, K. A review on condensing system for biomass pyrolysis process. Fuel Processing Technology 2018, 180, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Production and Characterization of Slow Pyrolysis Biochar; Faulstich, M., Ed. European Biomass Conference and Exhibition, Berlin, 6-9.07.2011; ETA-Florence Renewable Energies, 2011.

- Werner, C.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Gerten, D.; Lucht, W.; Kammann, C. Biogeochemical potential of biomass pyrolysis systems for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C. Environmental Research Letters 2018, 13, 44036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchard, N.; Schirrmann, M.; Cayuela, M.L.; Kammann, C.; Wrage-Mönnig, N.; Estavillo, J.M.; Fuertes-Mendizábal, T.; Sigua, G.; Spokas, K.; Ippolito, J.A.; et al. Biochar, soil and land-use interactions that reduce nitrate leaching and N2O emissions: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2354–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, H.-P.; Kammann, C.; Hagemann, N. Certification of the carbon sink potential of biochar. Version 2.1, Arbaz, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.european-biochar.org/media/doc/139/c-de_senken-potential_2-1.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Schmidt, H.-P.; Anca-Couce, A.; Hagemann, N.; Werner, C.; Gerten, D.; Lucht, W.; Kammann, C. Pyrogenic carbon capture and storage. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisotti, F.; Hoff, K.A.; Mathisen, A.; Hovland, J. Direct Air capture (DAC) deployment: A review of the industrial deployment. Chemical Engineering Science 2024, 283, 119416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziejarski, B.; Krzyżyńska, R.; Andersson, K. Current status of carbon capture, utilization, and storage technologies in the global economy: A survey of technical assessment. Fuel 2023, 342, 127776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsches Institut für Normung. DIN EN ISO 14064-1:2019-06, Treibhausgase_- Teil_1: Spezifikation mit Anleitung zur quantitativen Bestimmung und Berichterstattung von Treibhausgasemissionen und Entzug von Treibhausgasen auf Organisationsebene (ISO_14064-1:2018); Deutsche und Englische Fassung EN_ISO_14064-1:2018; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin.

- Gray, R. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg_project_accounting.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Osorio, A.M.; Úsuga, L.F.; Vásquez, R.E.; Nieto-Londoño, C.; Rinaudo, M.E.; Martínez, J.A.; Leal Filho, W. Towards Carbon Neutrality in Higher Education Institutions: Case of Two Private Universities in Colombia. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Banai, C.; Theis, T.L. Quantitative analysis of factors affecting greenhouse gas emissions at institutions of higher education. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 48, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilanzdija, N.; Voca, N.; Kricka, T.; Matin, A.; Jurisic, V. Energy potential of fruit tree pruned biomass in Croatia. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2012, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, S.; van Dongen, R.; Kern, J. Decomposition of cherry tree prunings and their short-term impact on soil quality. Applied Soil Ecology 2017, 117-118, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, N.; Conti, R.; Neumann, J.; Apfelbacher, A.; Daschner, R.; Binder, S.; Hornung, A. Thermo-Catalytic Reforming of Woody Biomass. Energy & Fuels 2016, 30, 7923–7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pari, L.; Suardi, A.; Santangelo, E.; García-Galindo, D.; Scarfone, A.; Alfano, V. Current and innovative technologies for pruning harvesting: A review. Biomass and Bioenergy 2017, 107, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Marti, B.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, E.; Callejón-Ferre, Á.J.; Estornell-Cremades, J. Mechanized methods for harvesting residues biomass from Mediterranean fruit tree cultivations. Scientia Agricola 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [Der Titel "Grella, Manzone et al. 2013 – Harvesting orchard pruning residues" kann nicht dargestellt werden. Die Vorlage "Literaturverzeichnis - Zeitschriftenaufsatz - (Standardvorlage)" beinhaltet nur Felder, welche bei diesem Titel leer sind.].

- Richter, F.; Raussen, T. Optimierung der Erfassung, Aufbereitung und stofflich-energetischen Verwertung von Grüngut in Deutschland. Müll und Abfall 2018, 18, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Polo; Cledera-Castro; Soria. Biogas Production from Vegetable and Fruit Markets Waste—Compositional and Batch Characterizations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6790. [CrossRef]

- Velásquez Piñas, J.A.; Venturini, O.J.; Silva Lora, E.E.; Del Olmo, O.A.; Calle Roalcaba, O.D. An economic holistic feasibility assessment of centralized and decentralized biogas plants with mono-digestion and co-digestion systems. Renewable Energy 2019, 139, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spokas, K.A. Review of the stability of biochar in soils: predictability of O:C molar ratios. Carbon Management 2010, 1, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legan, M.; Gotvajn, A.Ž.; Zupan, K. Potential of biochar use in building materials. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 309, 114704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; He, M.; Wang, L.; Yan, J.; Ma, B.; Zhu, X.; Ok, Y.S.; Mechtcherine, V.; Tsang, D.C.W. Biochar as construction materials for achieving carbon neutrality. Biochar 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhren, S.; Meyer, J.; Krause, H.; Saars, L. A multiperiod approach for waste heat and renewable energy integration of industrial sites. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 148, 111232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDI Verein deutscher Ingenieure. VDI 2067 - Wirtschaftlichkeit gebäudetechnischer Anlagen: Grundlagen und Kostenberechnung; Beuth GmbH: Berlin, 2012, 91.140.01 (2067) (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Pietzcker, R.; Feuerhahn, J.; Haywood, L.; Knopf, B.; Leukhardt, F.; Luderer, G.; Osorio, S.; Pahle, M.; Dias Bleasby Rodrigues, R.; Edenhofer, O. Notwendige CO2-Preise zum Erreichen des europäischen Klimaziels 2030; Ariadne-Hintergrund, Potsdam, 2021 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Carbonfuture GmbH. C-Senken Portfolios - Carbonfuture. Available online: https://platform.carbonfuture.earth/balancer/portfolios (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Young, J.; McQueen, N.; Charalambous, C.; Foteinis, S.; Hawrot, O.; Ojeda, M.; Pilorgé, H.; Andresen, J.; Psarras, P.; Renforth, P.; et al. The cost of direct air capture and storage can be reduced via strategic deployment but is unlikely to fall below stated cost targets. One Earth 2023, 6, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, B.; Hu, W.; Zhong, C. Establishment of Performance Metrics for Batteries in Large-Scale Energy Storage Systems from Perspective of Technique, Economics, Environment, and Safety. Energy Technology 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branker, K.; Pathak, M.; Pearce, J.M. A review of solar photovoltaic levelized cost of electricity. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 15, 4470–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, S.; Lamb, W.F.; Callaghan, M.W.; Hilaire, J.; Creutzig, F.; Amann, T.; Beringer, T.; Oliveira Garcia, W. de; Hartmann, J.; Khanna, T.; et al. Negative emissions—Part 2: Costs, potentials and side effects. Environmental Research Letters 2018, 13, 63002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KTBL-Dieselbedarfsrechner. Available online: https://daten.ktbl.de/dieselbedarf/main.html#0 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Cárdenas-Aguiar, E.; Gascó, G.; Lado, M.; Méndez, A.; Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Paz-González, A. New insights into the production, characterization and potential uses of vineyard pruning waste biochars. Waste management 2023, 171, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, L.S.; Ciria, P.; Carrasco, J.E. An assessment of relevant methodological elements and criteria for surveying sustainable agricultural and forestry biomass byproducts for energy purposes. BioResources 2008, 3, 910–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pari, L.; Alfano, V.; Garcia-Galindo, D.; Suardi, A.; Santangelo, E. Pruning Biomass Potential in Italy Related to Crop Characteristics, Agricultural Practices and Agro-Climatic Conditions. Energies 2018, 11, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grella, M.; Manzone, M.; Gioelli, F.; Balsari, P. Harvesting of southern Piedmont’s orchards pruning residues: evaluations of biomass production and harvesting losses. Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2013, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Laird, D.A.; Heaton, E.A.; Rathke, S.; Acharya, B.S. Soil carbon increased by twice the amount of biochar carbon applied after 6 years: Field evidence of negative priming. GCB Bioenergy 2020, 12, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ithaka Institute. European Biochar Certificate – Richtlinien für die European Biochar Certificate – Richtlinien für die Zertifizierung von Pflanzenkohle; 10.1G; Ithaka Institute: Arbaz, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Duca, D.; Toscano, G.; Pizzi, A.; Rossini, G.; Fabrizi, S.; Lucesoli, G.; Servili, A.; Mancini, V.; Romanazzi, G.; Mengarelli, C. Evaluation of the characteristics of vineyard pruning residues for energy applications: effect of different copper-based treatments. Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2016, 47, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, E.S.; Li, H.; Cederlund, H.; Karltun, E.; Sundberg, C. Modelling biochar long-term carbon storage in soil with harmonized analysis of decomposition data. Geoderma 2024, 441, 116761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Cowie, A.L.; van Zwieten, L.; Bolan, N.; Budai, A.; Buss, W.; Cayuela, M.L.; Graber, E.R.; Ippolito, J.A.; Kuzyakov, Y.; et al. How biochar works, and when it doesn't: A review of mechanisms controlling soil and plant responses to biochar. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1731–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hougaard, I.-M. Enacting biochar as a climate solution in Denmark. Environmental Science & Policy 2024, 152, 103651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, E.; Tilsted, J.P.; Vogl, V.; Nikoleris, A. Imagining circular carbon: A mitigation (deterrence) strategy for the petrochemical industry. Environmental Science & Policy 2024, 151, 103640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.H.; Sterner, T. Few and Not So Far Between: A Meta-analysis of Climate Damage Estimates. Environmental and Resource Economics 2017, 68, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, A.; Cheng, X. Quantifying economic impacts of climate change under nine future emission scenarios within CMIP6. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).