1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), suicide is defined as the act of intentionally ending one's own life. From the epidemiological point of view, suicide is the leading cause of preventable premature death [

1]. The self-destructive act of suicide is preceded by suicidal thoughts. It is a broad term used to describe various fantasies, considerations, wishes, and desires related to committing suicide. The intensity of suicidal thoughts ranges from fleeting, passive reflections about the meaninglessness of further existence, to persistent, irresistible intrusive ruminations about suicide, taking into account a specific method of taking one's own life. Some definitions of suicidal ideation include planning suicide, while others treat the preparation of the plan as a separate stage [

2]. The ways of understanding the factors causing suicide have changed over time. Initially, the emphasis was on the interaction of stressors and individual vulnerabilities. Newer models present the factors that cause suicide as elements of a phase process [

3].

Suicidal behavior is a major public health problem worldwide because of its frequency and the destructive effects of the individual on the general population [

4]. Every year, more than 720,000 people die from suicide worldwide, and about 10-20 times more attempt suicide [

5]. In most countries, the risk of suicide is higher in adult men, while the risk of suicide attempt is higher in young women [

6]. This type of phenomenon is referred to as the gender paradox and is explained mostly by the aggressiveness and impulsiveness of men, resulting in the use of more lethal methods [

7].

Literature review by Motillon-Toudic et al. et al. (2022) showed that among the associations of suicide risk factors, the strongest association is between suicide and previous suicide attempts. Another significant association revealed in the aforementioned study is the association of suicide with mood disorders, including depression [

1]. Mental disorders are also considered to be another important risk factor, which occur in up to 90% of suicide victims [

6].

Data from 194 countries suggest that suicide rates vary depending on economic, social, cultural and environmental factors, as well as age and gender. In addition, suicides are on the rise globally in people with chronic physical and mental illnesses, including alcohol and substance abuse, as well as in people who have already attempted suicide. Much less information is available on the specifics and epidemiology of suicide attempts, but it is assumed that in some regions they may exceed the number of suicides by up to 30 times [

8].

1.1. The Role of Nursing Staff in Suicide Prevention

Nursing staff provide primary care, are closest to the patient, and have a better chance of assessing and identifying warning signs of a suicidal crisis. Therefore, it plays a key role in suicide prevention [

9]. According to previous studies, nurses understood suicide as a search for relief from physical, mental and social suffering that was difficult or impossible to overcome. They associated taking their own lives with serious illness, traumatic life situations or inability to meet family expectations, especially in patients from communities deeply rooted in cultural and religious traditions [

5]. It has also been noted that non-mental health nurses are unable to understand and criticize cases of suicide attempts or self-harm, indicating that they are mostly focused on physical care [

9]. Understanding appropriate attitudes toward people with suicidal thoughts is a fundamental step in a nursing student's education program that can influence the course and experience of clinical internship and shape future nursing practice [

4].

1.2. Risks to Nurses' Mental Health

Nursing is a demanding profession that puts a significant strain on staff physically and mentally. Nurses are expected to be humane, compassionate, competent and conscientious in a demanding work environment. On a daily basis, nurses deal with the deteriorating condition of patients, frequent cases of death and bereavement of families, and at the same time they must provide professional and appropriate support to patients and their relatives [

10]. Chronic stress at work adversely affects the mental health of this group of specialists. Over time, stress can lead to serious health problems such as heart disease, increased blood pressure, diabetes, and mental disorders, mi.in. depression and anxiety [

11]. A study by Fond et al. showed that about 25% of nurses suffer from depression [

12]. On the other hand, according to research by Pękacka et al., in Poland only 24% of the nurses surveyed do not show any symptoms of depression, 32% experience mild depression, 20% moderate depression, 16% moderately severe, and 8% severe [

13]. Disturbed circadian rhythms and insufficient quality and quantity of sleep are considered to be the two most important factors in the long-term impact of night work on the mental health of nurses [

14]. Rosenberg et al. found that mental health problems were more common in shift workers than in those in the permanent work system, and shift work was associated with a 33% increase in the risk of depressive symptoms [

15].

Depression and burnout not only affect nurses' well-being, but also have a negative impact on the workforce and the quality of healthcare provided, including layoffs, an increase in medical errors, and a decline in patient satisfaction [

16]. Major depression affects employee performance as well as organizational productivity. It is associated with an increase in absenteeism at work, short-term disability and reduced productivity and presenteeism, defined as the phenomenon of ineffective attendance at work as a result of poor health. Depressed workers can have impaired judgment of clinical situations, and errors in judgment can lead to serious consequences for both patients and staff [

17]. Joinson (1992) first used the term compassion fatigue to describe the loss of a nurse's ability to care in an emergency department setting. Specialists' sense of apathy and aloofness was associated with many environmental stressors, complex patient needs, trauma, and emotional distress. This term defines the negative feelings that nurses feel when they care for those who are suffering. Compassion fatigue from a nurse affects her quality of life and the people she cares for. It results in a decrease in compassion and empathy and an impairment of the ability to make decisions about patient care [

18,

19].

The COVID-19 pandemic has also taken its toll and exposed nurses to chronic traumatic stress, a strong mental health risk factor [

20]. As the pandemic continued, healthcare workers, particularly frontline nurses, experienced burnout, and many nurses in public health practices quit or temporarily left their jobs due to accumulated fatigue and mental distress [

21].

Studies from different countries show that nurses may be at increased risk of suicide. According to data from the Office for National Statistics in the United Kingdom and the U.S. National Violent Death Reporting System, nurses have a higher suicide rate than women in the general population [

22]. It was shown that nurses were almost twice as likely to die by suicide as the general population and 70% more likely than women doctors [

20].

In addition to suicide-related factors, widely described in the general population, some of them may be due to the function and workplace of health care workers. Working in a hospital involves situations that require certain skills, such as dealing with life and death management, physical and emotional pain and suffering experienced together with patients and their families. Such an environment can predispose to mental disorders such as stress, anxiety, depression and substance use, which can make it even more difficult for this group of specialists to seek specialist help. In addition, easy access to lethal drugs and knowledge how to use them are factors that increase the risk of committing suicide [

23].

1.3. Nursing Staff's Willingness to Talk About Suicide

In the context of nurses' readiness to talk to patients about suicide, it is worth emphasizing the importance of training for nursing staff in the field of suicide risk assessment. As Bolsner et al. Due to the lack of proper training, nurses are afraid to talk to patients about suicide. Research suggests that after receiving risk assessment training, nurses realize that this area is not significantly different from any other disease and, as a result, are better able to help people with suicidal tendencies [

24].

For interventions with patients after a suicide attempt, which are complex and challenging clinical situations, nurses need structured training that takes into account their specifics. In community psychiatric care, this type of training can use not only specialist and theoretical knowledge, but also the experience of people who have experienced a serious mental crisis themselves. Their knowledge and experiences can be particularly valuable, providing unique perspectives and practical tips that help nurses better understand and support patients in similar situations [

25].

Omerov and Bullington, on the other hand, draw attention to the importance of interpersonal competence in the assessment and care of patients in suicidal crisis. Qualities such as kindness, non-judgmental attitude, openness, and respect are beneficial in alleviating patient suffering, effectively assessing risk, and delivering appropriate care. On the other hand, the lack of a caring approach may result in patients hiding their needs, using escape strategies, or giving up seeking help in the event of subsequent suicidal crises [

26].

1.4. The Concept of the "Wounded Healer"

In 1951, Carl Jung first used the term "

wounded healer". The concept derives from Greek mythology and refers to individuals who, through their struggles and weaknesses, develop a deep understanding and empathy for the pain of others, which fosters effective therapeutic interventions [

27]. The identity of the wounded healer stems from awareness and attention to one's own pain and fear, which in turn affects the care of others. Awareness of fracture and mortality becomes a powerful tool when caring for another person's pain [

28]. Conti-O'Hare introduced the concept of the "wounded healer" into the nursing discipline and developed the theory of "

nurse as a wounded healer". She emphasized that when faced with physical, emotional, psychological, or spiritual trauma, nurses can adopt effective or ineffective coping strategies. People who use ineffective strategies may behave like "

walking wounded" and project their own struggles onto patients and colleagues, showing less empathy [

29]. Such people experience problems in social, intimate and professional relationships [

30]. In contrast, people who successfully manage trauma are able to recognize, overcome, and transform their pain into healing. Although the "scar" remains, personal traumas that have been the subject of deep reflection can turn nurses into "wounded healers," improving their ability to build therapeutic relationships with patients. It is not only their suffering that transforms them into healers, but also the awareness of the hurt and their willingness to accept and overcome it [

31]. The theory has some limitations, focusing mainly on healthcare professionals and how their emotions affect the provision of nursing care. The theory does not mention any support that the nurse receives from those around her, but focuses on how she deals with her own internal struggles and what coping strategies she uses to overcome difficulties [

30].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

The study is a continuation of a pilot study conducted on a group of 100 nurses, the results of which were presented at the 5th National Scientific Conference "Problems of human health – causes, current state, ways for the future".

The research was conducted as a cross-sectional study. The criterion for inclusion was an active license to practice the profession of a nurse and work in the profession. On the other hand, the exclusion criterion was work in administrative positions, where nurses did not take care of the patient.

2.2. Study Population

The presented study involved 400 female at-born nurses working in various hospital wards across Poland. The mean age of all participants was 36.815 years (SD = 10.385).

2.3. Outcome Measure

The study used a demographic-descriptive questionnaire, an original questionnaire examining the competence to talk about suicidal topics, and two standardized psychometric methods: the Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ-R) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

The demographic and descriptive questionnaire contained 11 metric items concerning gender, age, place of residence, marital status, children, education, seniority, place and systems of work, as well as the use of psychological and psychiatric help, in order to characterize the group of respondents.

Author's questionnaire examining readiness to talk about suicide consisting of 13 single-choice items. The method items were generated by AI (Microsoft Copilot). The AI was asked to identify key areas to assess nurses' readiness to talk to a patient about suicide. As part of the statistical analyses, two factors were identified: interpersonal and emotional competences and technical and procedural competences. The first factor assessed self-confidence in a conversation about suicide, the ability to manage one's own emotions, build trust in the relationship with the patient and ensure their safety, adapt to the patient's individual needs and awareness of their own limitations. Questions concerning the second factor included training and experience in crisis intervention and suicide prevention, knowledge of procedures and protocols in the area of dealing with situations of mental crisis of the patient and warning signs of suicide, as well as access to support resources at work and outside it. Knowledge of active listening techniques is included in both factors. The respondents gave subjective answers using a 5-point Likert scale.

The Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ-R) was used to assess suicidal risk. It consisted of three questions about suicidal thoughts and tendencies in the past and one about the likelihood of their occurrence in the future. The questions were single-choice, and the respondent answered on a 5, 6 or 7-point Likert scale. The points obtained for each answer added up, and the overall score ranged from 3 to 18 points. The higher the score, the greater the intensity of suicidal behavior [

32,

33].

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to diagnose the symptoms of depression and to make an initial assessment of its occurrence. The tool consists of nine items and one supplementary question. The subjects marked their answers on a 4-point Likert scale, assessing the frequency of depression symptoms in the last two weeks. The tenth question was addressed to people who recognized at least one of the symptoms mentioned earlier and referred to the degree of difficulties in everyday life due to their presence. Obtaining 5 points or more indicates the occurrence of depression with a further division according to its severity [

34,

35].

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study was submitted to the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Warsaw, which took note of it and did not raise any objections to the methodology of the study (statement number: AKBE/2/2025). Participation in the survey was equivalent to providing informed consent to participate in the study. The benefit for the study participants was not intended. No risks or inconveniences for the subjects were identified.

2.5. Data Collection

The survey was conducted from August to September 2024 using a questionnaire made available to the respondents online. The survey and statistical analysis were commissioned to the Bureau of Statistical Research and Analysis.

2.6. Data Analysis

The analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS 26.0 package together with the Exact Tests module and the Statistica 13.3 package. All relationships, correlations and differences were statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

The basic test that was used in statistical analyses was the Chi-square test for the independence of variables. It was mainly used for questions built on nominal scales. To determine the strength of the compound, coefficients based on the aforementioned test were used: Phi and V Kramer. The Phi measure also tells you the direction of the relationship (positive or negative). It should be remembered that the analysis with the Chi-square test is accurate when none of the theoretical numbers is less than one and when no more than 20% of the theoretical numbers are less than 5. Therefore, additional tests have been performed for each analysis with the Chi-square test, which are carried out in particular with small samples. These are tests performed using the following methods: accurate or Monte Carlo. The estimated test probability "p" indicates whether the analyzed relationship is statistically significant. Under each cross-tab, there is a letter (a) next to the result of the Chi-square test – it means that the calculated statistic may not meet the condition of the minimum expected number, therefore the exact or Monte Carlo test is also carried out for this eventuality. In this case, if the value of "p" is calculated on the basis of the Monte Carlo method, it is additionally denoted by the letter (b). The significance "p" of the Phi and V Kramer coefficients is determined on the basis of the result of the Chi-square test.

When the variables were ordinal, the following coefficients were used: Kendall's Tau-b for tables with the same number of columns and rows, and Kendall's Tau-c for tables with different numbers of columns and rows. The values of the coefficients can take negative results, similar to the Phi measure. Therefore, they allow you to determine not only the strength but also the direction of the correlation. Under each cross-tab, there is, among other things, the value of the coefficient and the statistical significance "p". In addition, the value "p" is calculated using the Monte Carlo method, which is also denoted by the letter (c). If, as a result of the analyses, it turned out that there were no statistically significant correlations using the Tau-b and Tau-c Kendall coefficients, then the relationship was checked based on the chi-square test and an appropriate symmetric measure informing about the strength of the relationship. Thanks to this, it was possible to detect a possible relationship that is not monotonic.

Measures of the strength of the association for the above-mentioned coefficients range from 0 to 1, with a higher value of the coefficient indicating a stronger relationship/correlation. As mentioned above, the results obtained can also take negative values (except for Kramer's V measure), which indicates the direction of the relationship, but the interpretation of the strength of the relationship is similar.

While the dependent variable was measured on a quantitative scale and the independent on a qualitative scale, and when the conditions for the use of parametric tests were not met, nonparametric U tests were used by Mann Whitney (for 2 samples) and Kruskal Wallis (for more than 2 samples). In the course of these analyses, in addition to the standard statistical significance, the corresponding "p" values were also calculated using the Monte Carlo method. This is indicated by the letter (b) for the significance score for the Mann Whitney U test and by the letter (c) for the "p" score of the Kruskal Wallis test.

Correlations between ordinal or quantitative variables (during the non-met conditions of using parametric tests) were performed using Spearman's rho coefficient, which informs about the strength of the compound and its direction – positive or negative. The resulting value ranges from -1 to 1, with (-1) being an excellent negative correlation and (1) a perfect positive correlation.

In the construction of the questionnaire to assess readiness to talk about suicide, the Varimax factor analysis using the principal axes method was used to isolate factors. Reliability was determined by calculating Cronbach's Alpha coefficient [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

3. Results

Thanks to the data obtained from the demographic-descriptive questionnaire, the group of nurses participating in the study was characterized.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study group.

3.1. Depression and Suicidality Risk in Nursing Staff

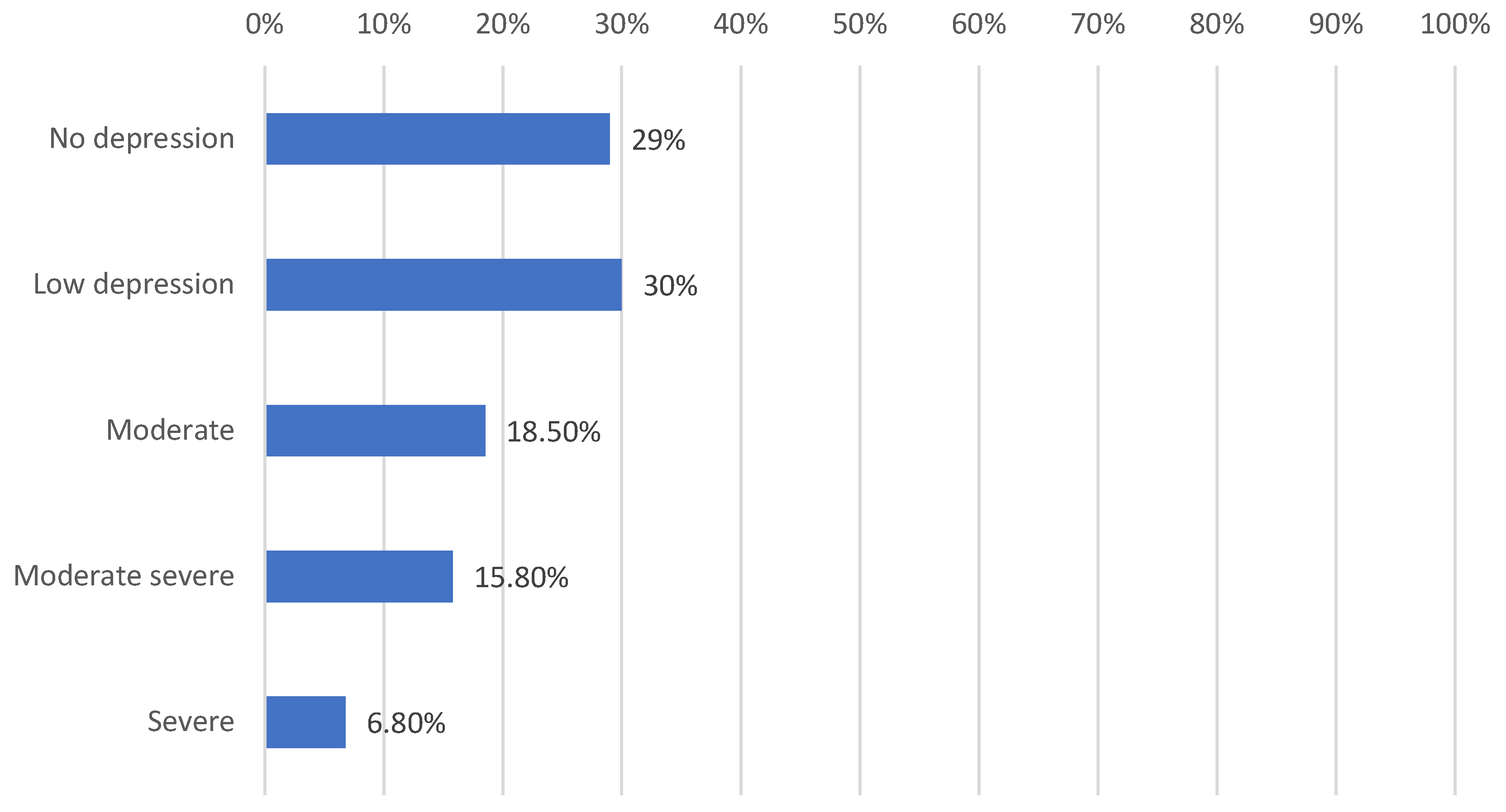

The analysis of PHQ-9 results showed that 71% of the subjects (N = 284) struggled with depression symptoms of varying severity. Most participants suffered from mild depression (N = 120), while its absence was found in only 29% (N = 116).

Figure 1.

Severity of depression in the study group based on PHQ-9.

Figure 1.

Severity of depression in the study group based on PHQ-9.

It has been confirmed that as the level of PHQ-9 depression increases, the results of SBQ-R suicidal behavior also increase (rho = 0,579, p < 0,001). Higher scores of the level of PHQ-9 depression and SBQ-R suicidal behavior were achieved by younger people (PHQ-9: Tau-c Kendalla = -0,153, p < 0,001; SBQ-R: rho = -0,127, p < 0,02) and those just beginning their nursing careers starting to become nurses (PHQ-9: Kendall’s Tau-b = -0,161, p < 0,001; SBQ-R: rho = -0,102, p < 0,05). Other factors negatively affecting the level of depression and suicidal behavior include lack of offspring, work only on night duty and marital status of a single or unmarried.

The PHQ-9 and SBQ-R results are not significantly differentiated by the type of facility where nursing staff are employed. The type of ward in which the respondents work also did not correlate with the level of depression on the PHQ-9 scale, but it was observed that people working in the psychiatric ward are characterized by a higher level of SBQ-R compared to the respondents from other wards (H = 15,158, df = 5, p < 0,02).

It was observed that the group of respondents who had used psychological help in the past achieved higher scores of depression and suicidality compared to the group that had never used such help (PHQ-9: U = 9243,00, Z = -5,972, p < 0,0001; SBQ-R: U = 3141,00, Z = -6,785, p < 0,0001), while the highest results were shown in the staff group that is currently under the care of a psychologist (PHQ-9: U = 2954,50, Z = -4,706, p < 0,0001; SBQ-R: U = 9276,00, Z = -5,989, p < 0,0001). No significant differences were found between the group receiving psychological help in the past and now.

It has not been shown that age, place of residence or degree of education have a significant impact on the level of depression and suicidal behavior.

3.2. Competence of Nursing Staff to Talk to Patients About Suicide

3.2.1. Initial Validation of a Questionnaire Examining the Staff's Competence to Talk to the Patient About Suicide

In order to conduct this study, a questionnaire was created to assess the competence of the examined staff in conducting conversations about suicide with the patient. The questionnaire contains 13 questions about both social and procedural skills. The survey allowed respondents to self-assess, allowing them to assess their strengths and weaknesses in selected categories.

In order to examine the psychometric properties of the questionnaire, a factor analysis was carried out using the main axes method, extracting two factors from the items included in the questionnaire, the results of which are presented in

Table 2.

The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by the Cronbach Alpha coefficient, which is a measure of the internal consistency of the questions. The value of the coefficient for factor I: 0.804213952, and for factor II: 0.812203491, which confirms the one-factor structure of the resulting tool.

Table 3.

Preparedness questionnaire broken down by selected factors.

Table 3.

Preparedness questionnaire broken down by selected factors.

| Factor I: Interpersonal and emotional competence |

2. Do you feel comfortable talking to the patient about suicide? (Are you confident and not afraid to bring up this topic)

5. Are you able to establish an empathetic and supportive relationship? (Do you have the ability to build trust and provide emotional support to the patient)

8. Can you manage your own emotions, e.g. are you able to remain calm and professional, even in difficult situations?

10. Do you know active listening techniques?

11. Can you adapt your approach to the individual needs of the patient?

12. Are you aware of your limitations, e.g. when you need support from other specialists?

13. Can you create a safe and supportive environment for the patient to feel safe and open up to difficult topics? |

| Factor II: Technical and procedural competence |

1. Do you have adequate training in crisis intervention and suicide prevention?

3. Do you know the procedures and protocols for dealing with a patient's mental crisis?

4. Can you recognize the warning signs of suicide?

6. Do you have access to support resources within the institution where you work?

7. Do you have access to support resources outside the institution where you work?

9. Do you have experience in working with patients in mental crisis?

10. Do you know active listening techniques? |

3.2.2. Psychological Help

The analysis showed that the differences between staff not receiving psychological help (group 1) and those currently receiving psychological assistance (group 3) indicate that in the case of important questions (1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 11) (p < 0.05), the latter obtained higher scores. Staff who have received psychological help in the past (group 2) also scored higher on relevant questions (4, 7, 9, 10) compared to those who had never received such assistance. The difference between the group treated in the past and now was detected in two questions, where the latter scored higher.

The differences between group 1 and group 2 turned out to be significant in the case of both factors, where higher scores were obtained by group 2 (factor 1: U = 12946,50, Z = -1,991, p < 0,05; factor 2: U = 11278,50, Z = -3,784, p < 0,0002). Group 3 in comparison with group 1 also achieved higher results (factor 1: U = 3996,00, Z = -2,498, p < 0,02; factor 2: U = 4065,50, Z = -2,350, p < 0,02), while the results of groups 2 and 3 did not differ significantly.

3.2.3. Psychiatric Treatment

Differences between nurses that has never received psychiatric treatment (group 1) and the group that underwent treatment in the past (group 2) indicated higher scores in the receiving group for six questions (1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 12) and factor 2 (U = 8286.00, Z = -3.44, p < 0.001). Differences between nurses who have never received treatment and those who are currently in treatment indicate higher scores for the latter in questions 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 12 and in factor 1 (U = 5333.50, Z = -2.82, p < 0.008) and 2 (U = 5257.50, Z = -2.82, p < 0.005). The differences between group 2 and group 3 were revealed only in the higher scores of group 3 in question 12 (U = 1660.00, Z = -2.49, p < 0.02).

4. Discussion

In the course of statistical analyses, an alarming percentage of nursing staff affected by depressive disorders was revealed, which amounted to 71%, and is similar to the results of other studies conducted so far in Poland. Kubik et al. showed a slight exacerbation of depressive symptoms in 41.81% of nurses, moderate in 17.68%, and moderate to severe in 4.76% [

11]. According to a study conducted in India, 74% experience varying degrees of anxiety, and 70.8% suffer from mild to very severe depression [

43]. In France, 29.3% of the nursing staff suffer from depression [

12], while in the United States, among nurses who were diagnosed with symptoms of depression, 32% were clinically depressed and 58% said they suffered from depression in the ordinary sense [

43].

Considering the impact of individual socio-demographic data on the level of depression and suicidal risk, it was noted that the lack of offspring, night work only and marital unmarried status were associated with an increase in depression and suicidal risk among nursing staff. Other studies are consistent with our results. The lack of a partner and offspring are important predictors of the risk of self-harm. Having children can reduce feelings of loneliness and give a sense of purpose in a parent's life. In addition, children, like a life partner, can be an important source of emotional and social support [

23,

44]. In contrast, disturbed circadian rhythms and insufficient quality and quantity of sleep were identified as the two most important factors in the long-term impact of night shift work on the mental health of nurses [

45].

In our study, the place of employment, the status and the level of education did not affect the mental state of the respondents in the evaluated aspects. This is not consistent with the available literature, as a number of studies describe the significance of the above data in the context of depressive disorders and suicidal risk. According to the study by Kumar et al. in the general population, higher education was a protective factor, due to the associated higher earnings, while older age was a risk factor [

46]. On the other hand, research shows that younger people in the professional group of nurses are more likely to suffer from depression and suicide risk, which is associated with less professional experience and greater susceptibility to stress in crisis situations [

47,

48]. Gruebner et al. showed in their study that the risk of mental disorders, including depression and anxiety, is higher in people living in large cities, but the cause has not been clearly established [

49]. Similar conclusions were also formulated in the study by Sampson et al. [

50]. However, other conclusions were drawn from studies conducted in China, where urbanization was a factor positively affecting the treatment of depression due to increased access to therapeutic resources [

51].

Analysis of the results showed that nurses who received psychological or psychiatric help in the past or currently were characterized by higher levels of depression and suicide risk. At the same time, despite experiencing mental suffering in the form of low mood and a decrease in the will to live, the readiness and effectiveness of care for patients in crisis in this group was higher than among staff who did not use help and declared a better mental state. Our results are consistent with the concept of "

wounded healer", which refers to people who, through their struggles and weaknesses, develop a deep understanding and empathy for the pain of others [

27]. In addition, participation in psychotherapy can foster the quality of help by developing emotional competences such as empathy, compassion or mentalization [

52,

53,

54]. On the other hand, people who had never received psychological or psychiatric help reported lower depression and suicidality as a group, but only 29% of the study population did not show any symptoms of depression. At the same time, these people were less competent in providing assistance to people in mental crisis. This creates an image of "

unhealed healers", i.e. nurses who, immersed in their problems, are characterized by reduced efficiency at work, which is revealed by the lower quality of care and readiness to provide it. Previous research confirms that poor mental well-being of nurses correlates with reduced work productivity, manifested by higher rates of presenteeism, impairment of daily activities, and overall loss of productivity [

55].

In conclusion, the study showed that nurses are a professional group with a high risk of depression and suicide, although in some respects heterogeneous. The highest severity of symptoms was reported by subjects receiving psychological and psychiatric help. This may be due to the fact that the use of specialist mental health help increases self-awareness of the difficulties experienced and fosters readiness to report emotional problems [

56,

57,

58]. Additional differences were revealed in the provision of assistance to patients. Despite the fact that nurses receiving psychological and psychiatric help reported the highest levels of depression and suicidality, their competence in providing help to people in suicidal crisis was higher than that of those who did not receive such help. Given that the entire study population of nurses as a professional group showed a high risk of depression and suicide, the use of psychological and psychiatric help was a decisive factor in whether a nurse would become a "wounded healer" or an “walking wounded unhealed healer". In other words, whether their own suffering will become a resource or merely a psychological degrading factor.

This study has several limitations. Cross-sectional studies do not allow for determining the direction of relationships between variables, which makes it impossible to establish causality. Additionally, the sample may not be fully representative of the entire nursing population. While 400 participants constitute a significant sample, it may not account for the diversity of all nurses in Poland, much less nurses worldwide. The results of our study are limited to individuals assigned female at birth. We chose this sample due to the gender imbalance in the Polish nursing population [

59], which would affect the quality of statistical analyses. According to a report prepared in 2023 at the request of the Supreme Chamber of Nurses and Midwives in Poland, women account for 97.1% of the nursing staff [

59].

Another limitation of the study is the data collection method based on self-reporting. The topic of depression and suicide can be difficult for some individuals, potentially affecting their willingness to participate and the quality of their responses. Additionally, self-assessment of competence to talk about suicide is subjective and depends on the individual experiences and feelings of nurses, which can also be reflected in the results.

Considering these limitations, further research on a larger sample is planned, in the form of multicenter longitudinal studies, based on mixed measurement methods, including a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods (e.g., surveys supplemented by in-depth interviews).