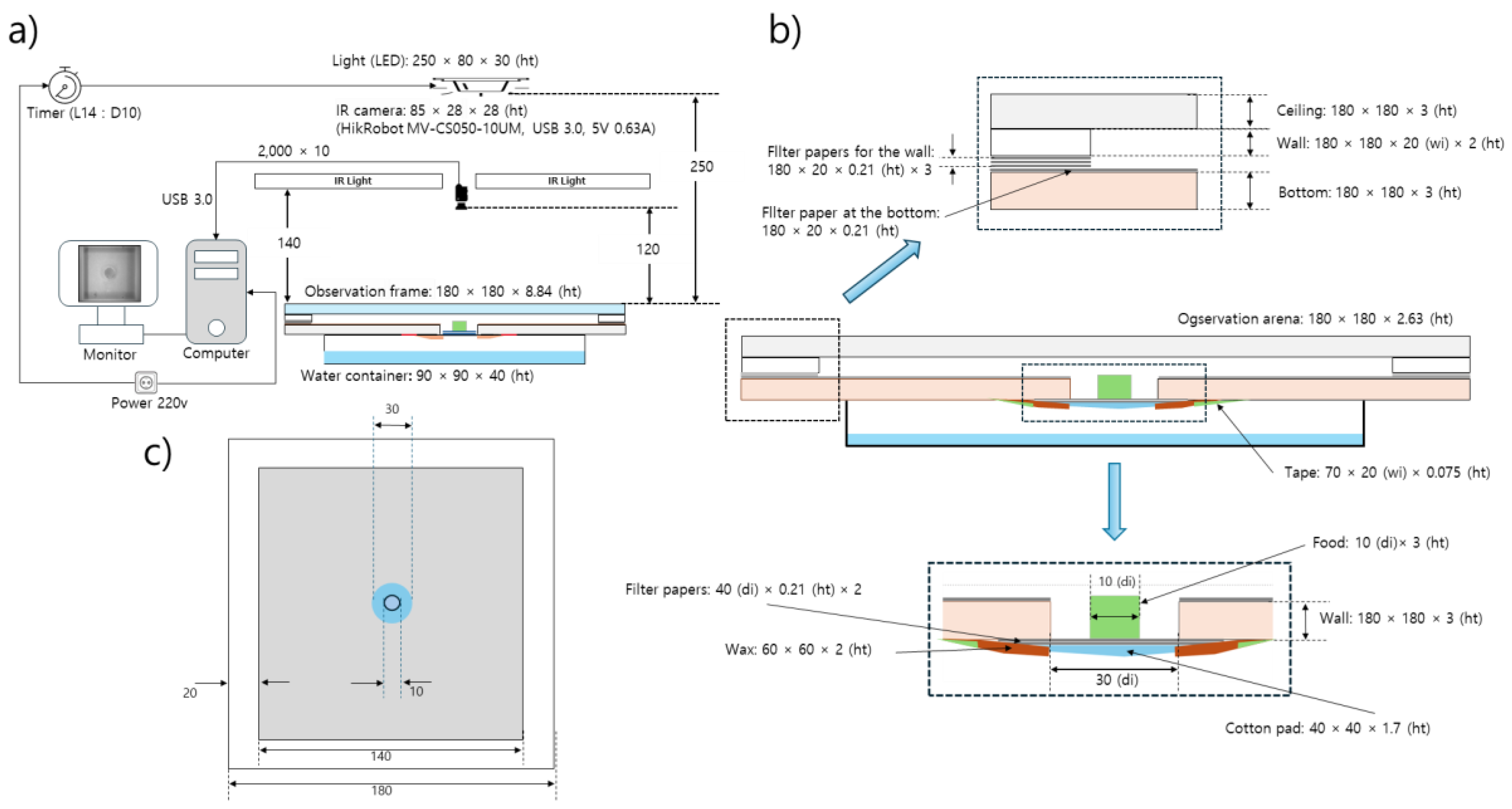

3.1. Overall Movement Positions and Parameter Frequencies

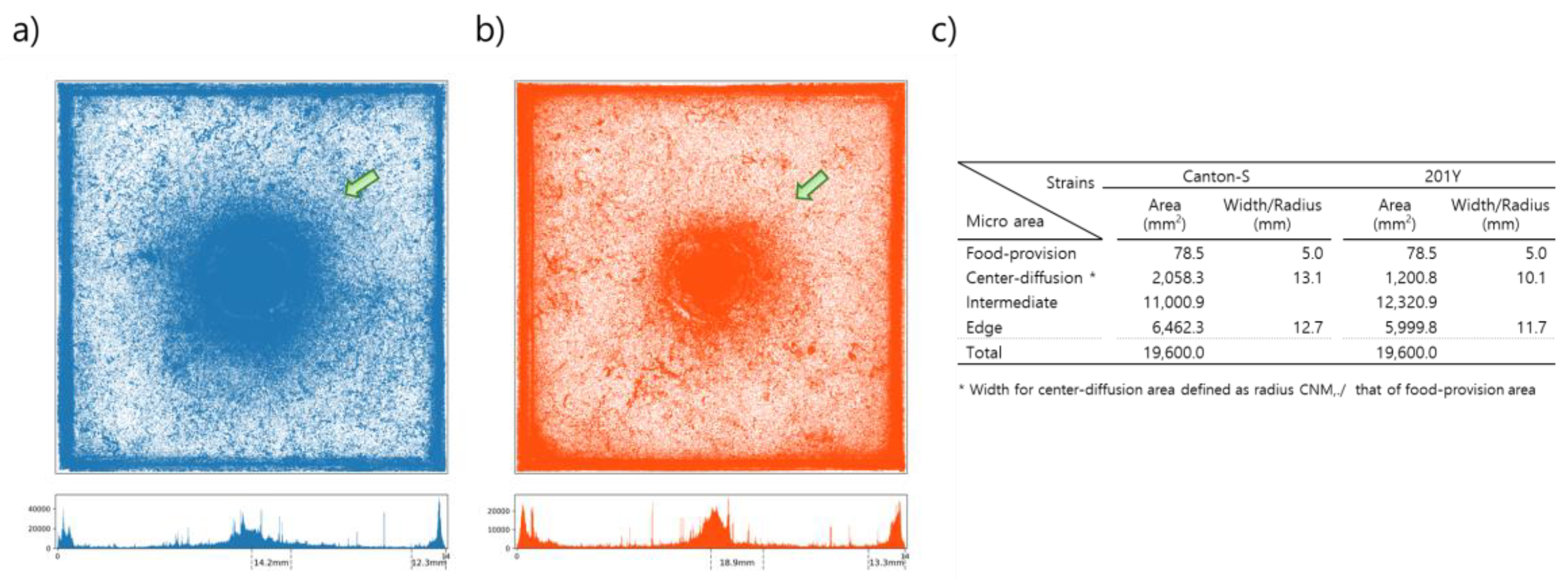

Figure 2 presents the cumulated movement positions within the observation arena of 10

D. melanogaster individuals from strains Canton-S and 201Y over the 24 h observation period for all eight trials. The center area had the highest density of movement positions for both strains (green arrows,

Figure 2). It is noted that the center area with high densities was broader for Canton-S than in 201Y. The spatial clustering based on the accumulated movement positions was obtained from DBSCAN. The positions along the four sides of the observation arena were combined into one coordinate and clustering was conducted in one dimension. The center area with high cumulated positions was defined as the center-diffusion area after clustering, but the food-provision area (10 mm in diameter) within the center-diffusion area was excluded and instead considered separately as its own micro-area. The food-provision area was thus fixed at 78.5 mm

2 for both strains, while the center-diffusion area was broader for Canton-S (2,058.3 mm

2) than for 201Y (1,200.8 mm

2) (

Figure 2c). The edge area was similar for the two strains (6,462.3 mm

2 and 6,000.0 mm

2, respectively, for Canton-S and 201Y. The intermediate area was defined as the area between the center-diffusion and edge areas (

Figure 2c) and was used to observe the activity of individuals in open space. The intermediate area was broader for 201Y (12,320.9 mm

2) than for Canton-S (11,000.9 mm

2).

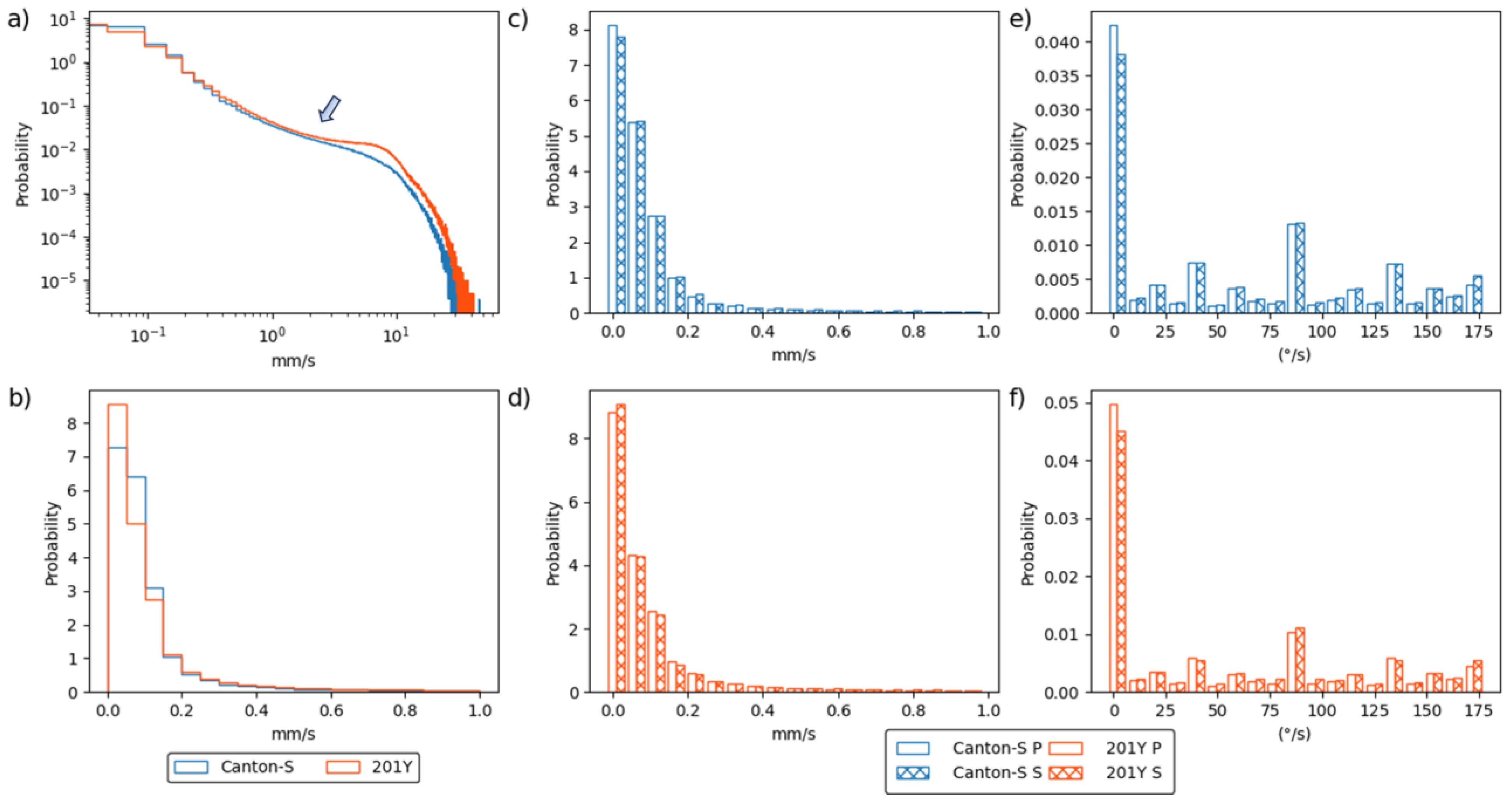

To assess the motility of group movement during the observation period, histograms for the speed and DCR were obtained during the photo- and scotophases.

Figure 3a presents the frequencies for speed over the entire observation period for Canton-S and 201Y on a log–log scale. Higher speeds were more frequent for 201Y than for Canton-S, especially above 1 mm/s (arrow,

Figure 3a).

Figure 3b displays the frequencies for speeds lower than 1 mm/s. These frequencies were highly skewed right, with extremely low frequencies above 0.2 mm/s.

Figure 3c and 3d compare the frequencies for speeds lower than 1.0 mm/s during the photo- and scotophases for Canton-S and 201Y, respectively. Frequencies were highly skewed right with extremely high frequencies of low speeds under 0.2 mm/s. The frequencies for speed during both the photo- and scotophases were similar overall for both strains (

Figure 3c,d).

The frequency curves for the DCR were similar for the photo- and scotophases with a low range for both strains (

Figure 3e,f). The first bin (0–9 °/s) had a very high frequency, indicating a straight and forward direction of group movement. The DCR was also higher for the angles close to 90 °/s and 180 °/s for both strains, while the frequencies for movement at angles of multiples values of 25 °/s (e.g., 45 °/s and 70 °/s) were relatively higher than other angles for both strains (

Figure 3e,f).

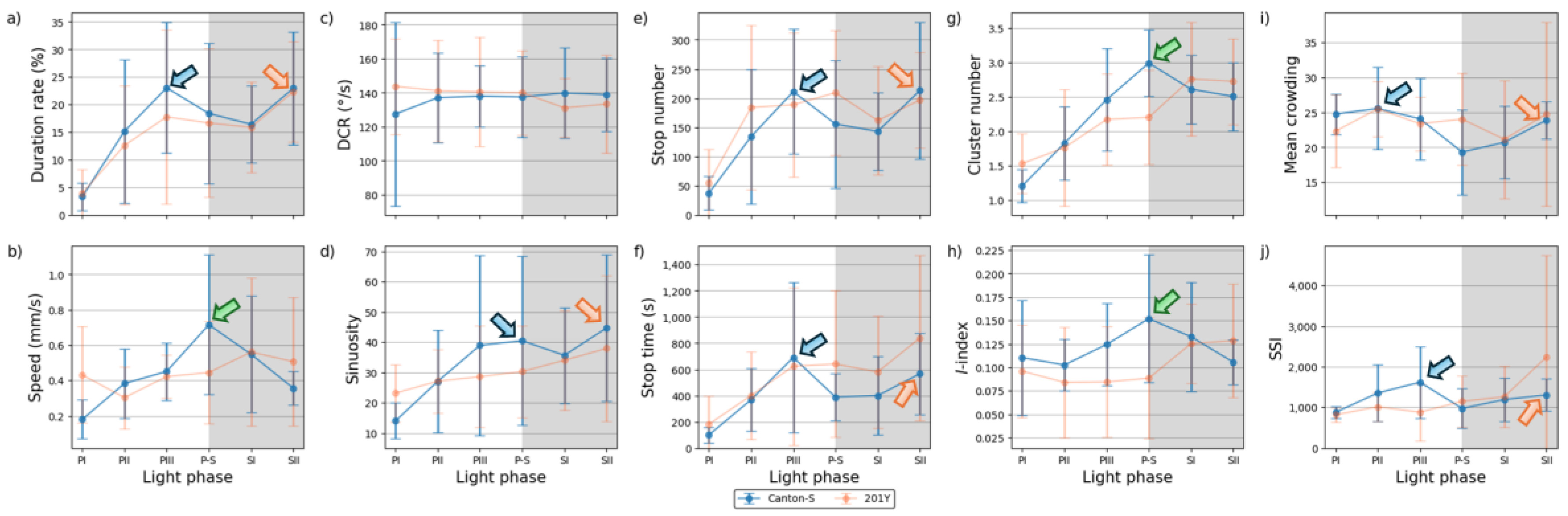

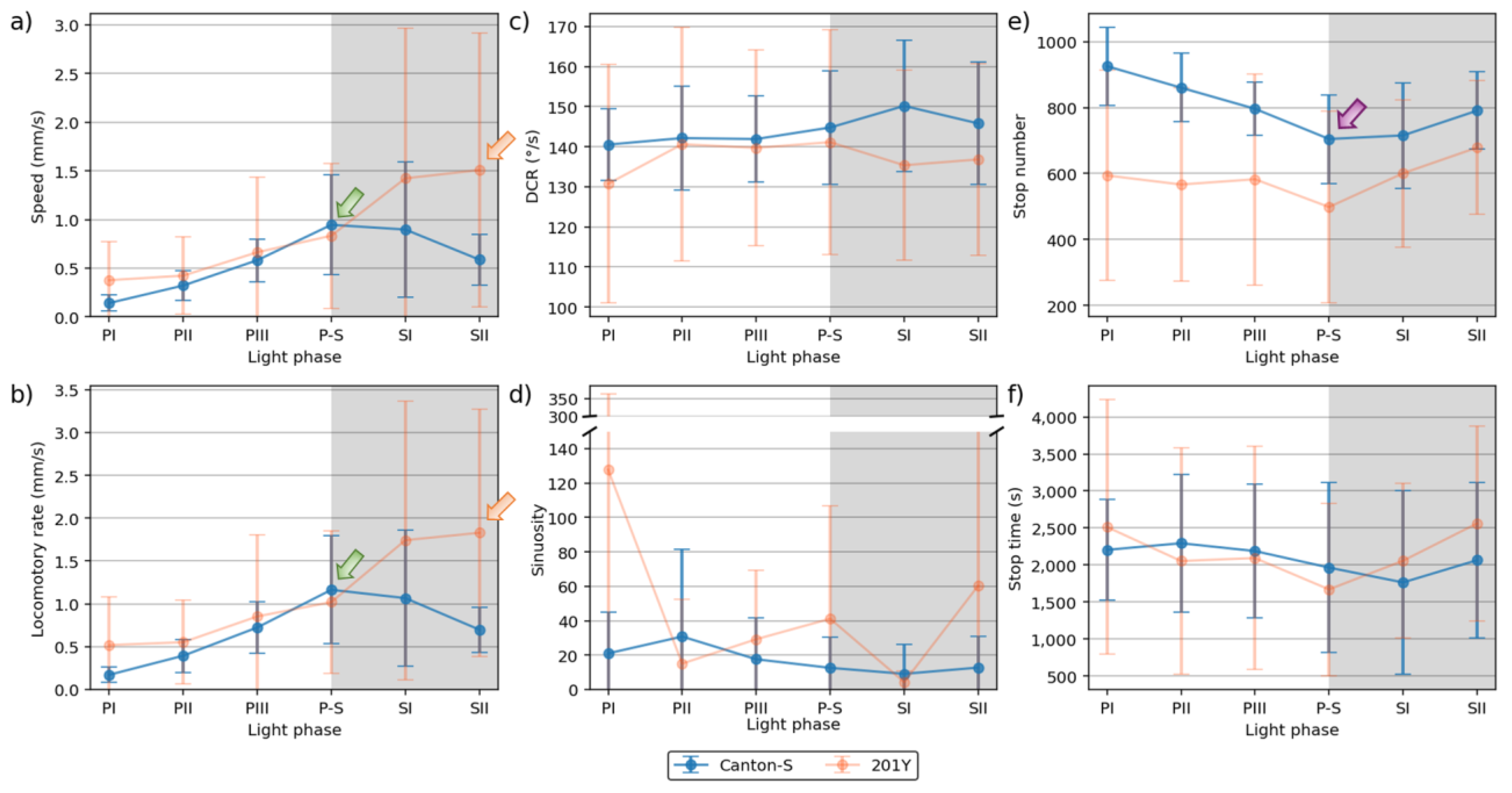

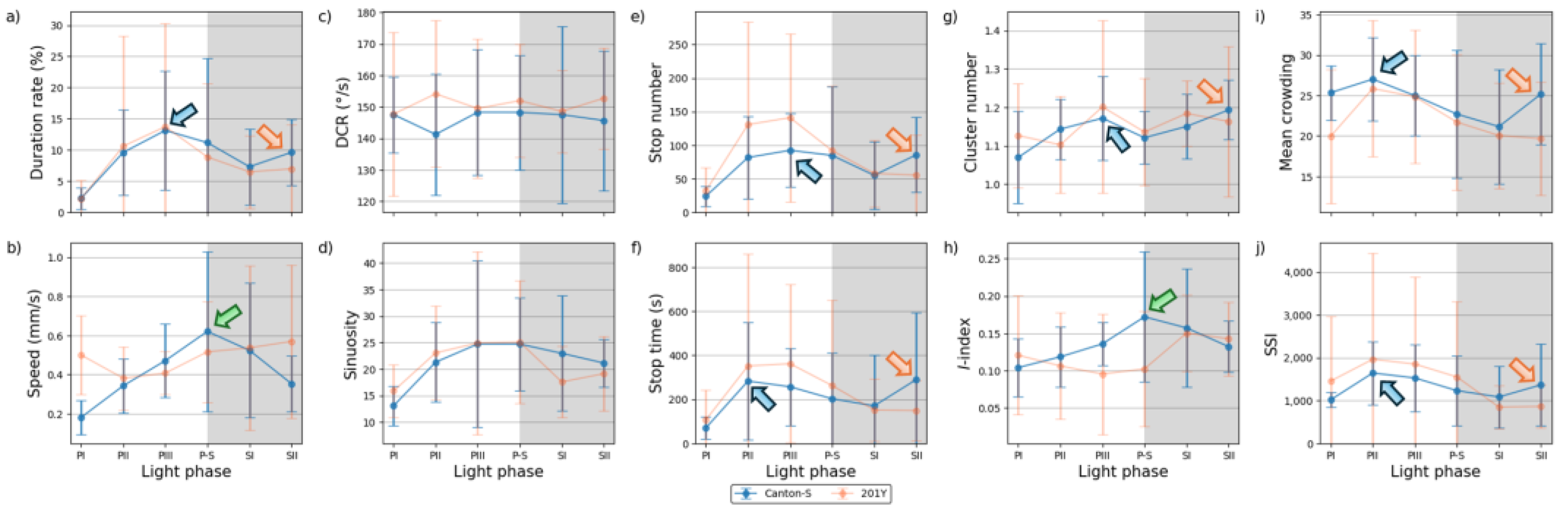

The movement parameters for the two strains within the observation arena according to the light phase are presented in

Figure 4 The diel difference within the observation arena differed between the two strains. For Canton-S, a peak in speed (1.0 mm/s) was observed during P-S (i.e., the transitional period between the photophase and the scotophase; green arrow,

Figure 4a) while, for 201Y, the speed continuously increased until the end of the scotophase (1.5 mm/s) (orange arrow,

Figure 4a). Speed was higher overall for 201Y (0.9 mm/s on average) than for Canton-S (0.6 mm/s on average), particularly during the scotophase (1.5 mm/s and 0.7 mm/s on average, respectively). During the photophase, the speed of 201Y (0.5 mm/s) was slightly higher than that of Canton-S (0.4 mm/s), indicating that the higher overall speed for 201Y (

Figure 3a) was mainly due to activity during the scotophase.

The locomotory rate was also measured to assess the motility of groups only during those time units when the individuals moved (

Figure 4b). The locomotory rates were overall close to speed for both Canton-S and 201Y. A slight increase was observed in the locomotory rates compared to the speed across the light phases, with the maximum observed during P-S for Canton-S (1.2 mm/s) and 201Y (1.8 mm/s). No qualitative difference between the speed and locomotory rate was observed because only a small number of stops occurred in the group movement of

D. melanogaster within the observation arena during the observation period.

In contrast to the speed, the DCR (

Figure 4c) was stable across the light phases at around 140.9 °/s without a clear diel difference in the two strains (Canton-S: 144.2 °/s; 201Y: 137.4 °/s), with slight differences including a slight increase for Canton-S (145.8 °/s) and a slight decrease for 201Y (136.8 °/s) during SII.

Sinuosity (

Figure 4d) was stable overall at an average of 17.3 across the light phases for Canton-S, though it rose to 23.1 and decreased to 10.9 during the photophase and scotophase, respectively. For 201Y, sinuosity was particularly high during PI (127.7) and SII (60.3). Except for these periods, however, the sinuosity had a stable range of 22.4 on average (

Figure 4d).

The stop number exhibited the opposite pattern to that of the speed and locomotory rates, with a minimum (704.8) during P-S for Canton-S (purple arrow,

Figure 4e), indicating that the stop number decreased when the speed increased. The stop number was consistently lower during all of the light phases for 201Y than for Canton-S (

Figure 4e). The diel differences for 201Y during the photophase (581.2) and scotophase (639.7) were not as large as for Canton-S, showing 860.7 and 753.1, respectively. Like Canton-S, the minimum stop number for 201Y was observed during P-S (498.5).

The pattern for the stop time according to the light phase was markedly different from that for the stop number (

Figure 4f). The stop time was relatively stable without a clear diel difference, reaching 2,229.4 s during the photophase and 2,915.3 s during the scotophase on average for Canton-S. The trend in the stop time was also stable, covering a narrow range for 201Y during the photophase and scotophase (2,220.7 s and 2,309.8 s, respectively).

The SD (vertical bars in

Figure 4) varied greatly according to the light phase and strain. For Canton-S, the SD range was overall shorter and more stable across the light phases than for 201Y. For the DCR, the SD was consistently high across the light phases for 201Y compared with Canton-S, relatively high during the photophase for the stop number and time, and relatively high during the scotophase for the speed and locomotory rate (

Figure 4). High SDs at PI, P-S and SII were also noted with sinuosity for 201Y.

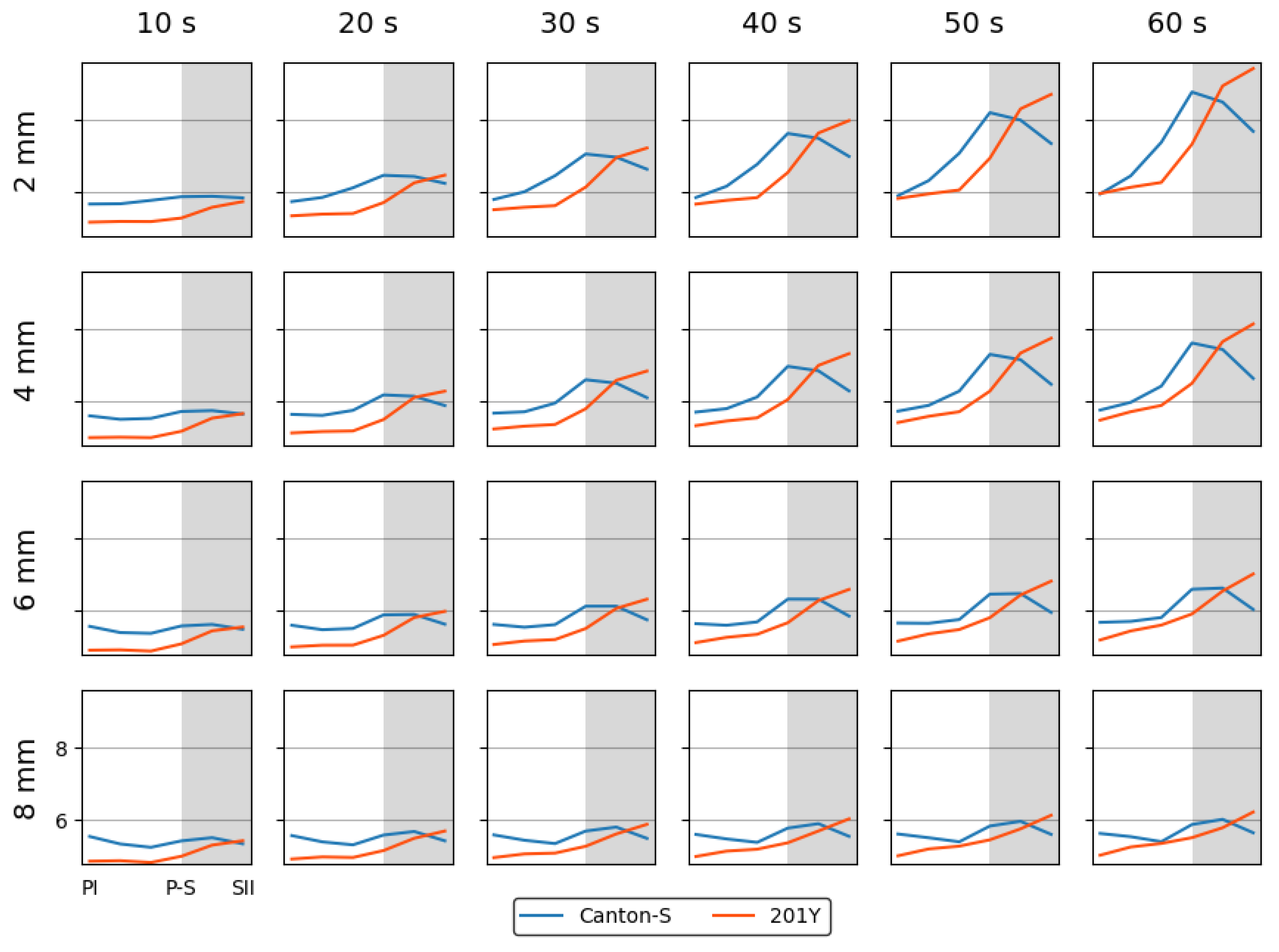

3.3. Dispersion Parameter Measurements

Spatial and temporal units were determined to obtain dispersion parameters. Clustering represents how many local groups are spatially observed in the cumulated group movement positions. In determining the spatial units, the threshold distance (

ε) for clustering was examined from 2 mm to 8 mm at intervals of 2 mm across time window sizes from 10 s to 60 s at intervals of 10 s. The cluster numbers obtained using the different spatial units and time windows according to the light phase are listed in

Figure A1 The number of clusters increased as the window size increased, while the trend in the cluster number according to the spatial unit size was similar overall, though there was a slight difference between the two strains during the late scotophase.

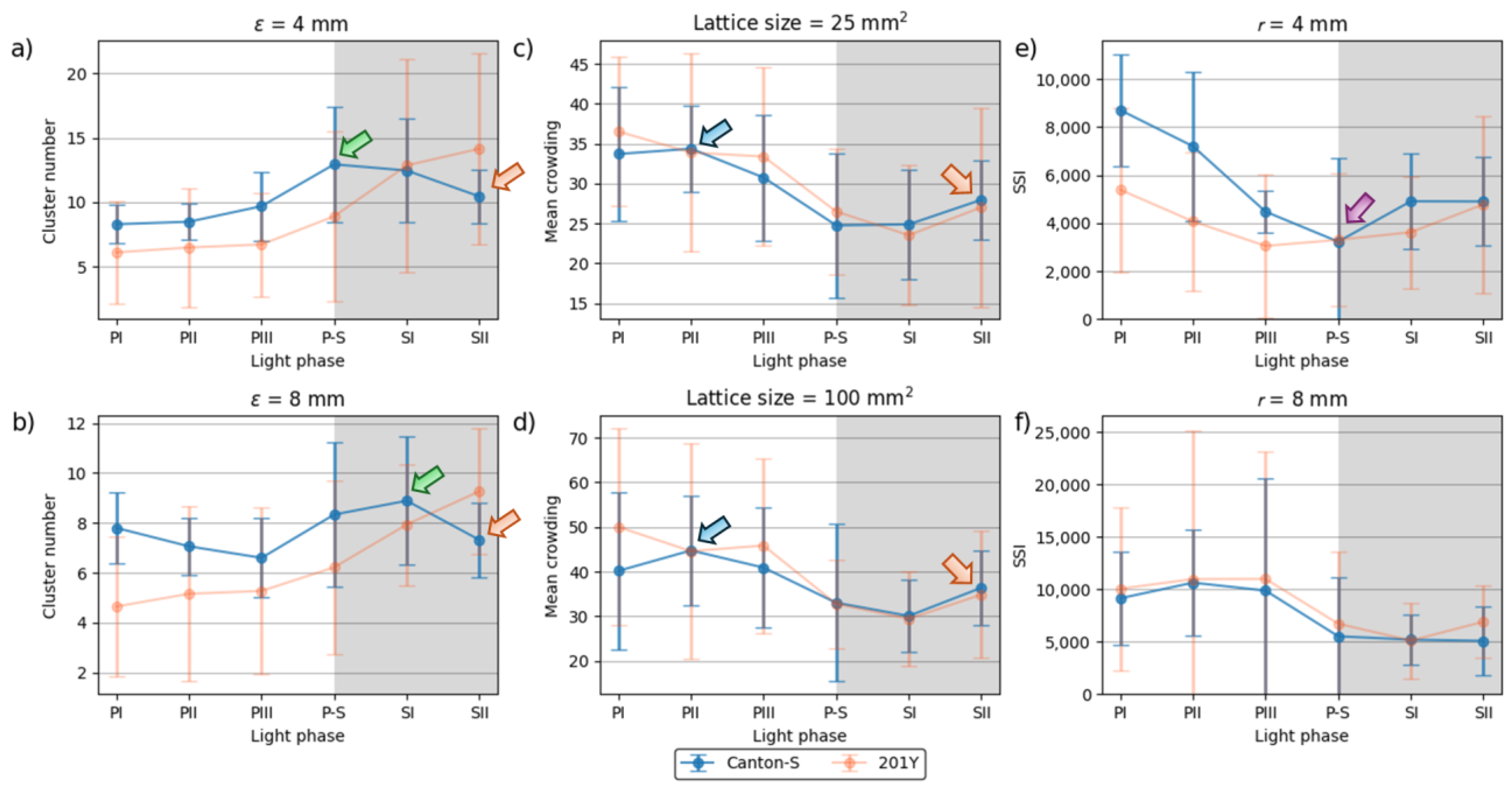

To examine the cluster patterns in more detail, we selected

ε = 4 mm and 8 mm as the threshold distance, with 30 s as the window size. The trend over time for the cluster number with the two threshold distances was generally similar (

Figure 6a,b). With

ε = 8 mm, the cluster number (6.6–8.9 on average) was lower overall than

ε = 4 mm (4.7–9.3). For Canton-S, the peak was delayed during SI (8.9) (green arrow,

Figure 6b) and the cluster number decreased during PI–PIII (7.8, 7.1, and 6.6, respectively) for Canton-S, whereas the cluster number slowly increased with

ε = 4 mm during this period (

Figure 6a). Differences in the cluster number was observed for 201Y compared with Canton-S. For 201Y, the cluster number was low during PI and continuously increased until SII for both threshold distances (

Figure 6a,b). In addition, the SD range was generally broad during the scotophase with

ε = 4 mm and during the photophase with

ε = 8 mm for 201Y.

The overall dispersion patterns for the movement positions were examined using the

I-index. Because the

I-index globally measures the dispersion pattern focusing on individual isolation over the entire observation arena, the determination of local spatial units was not necessary.

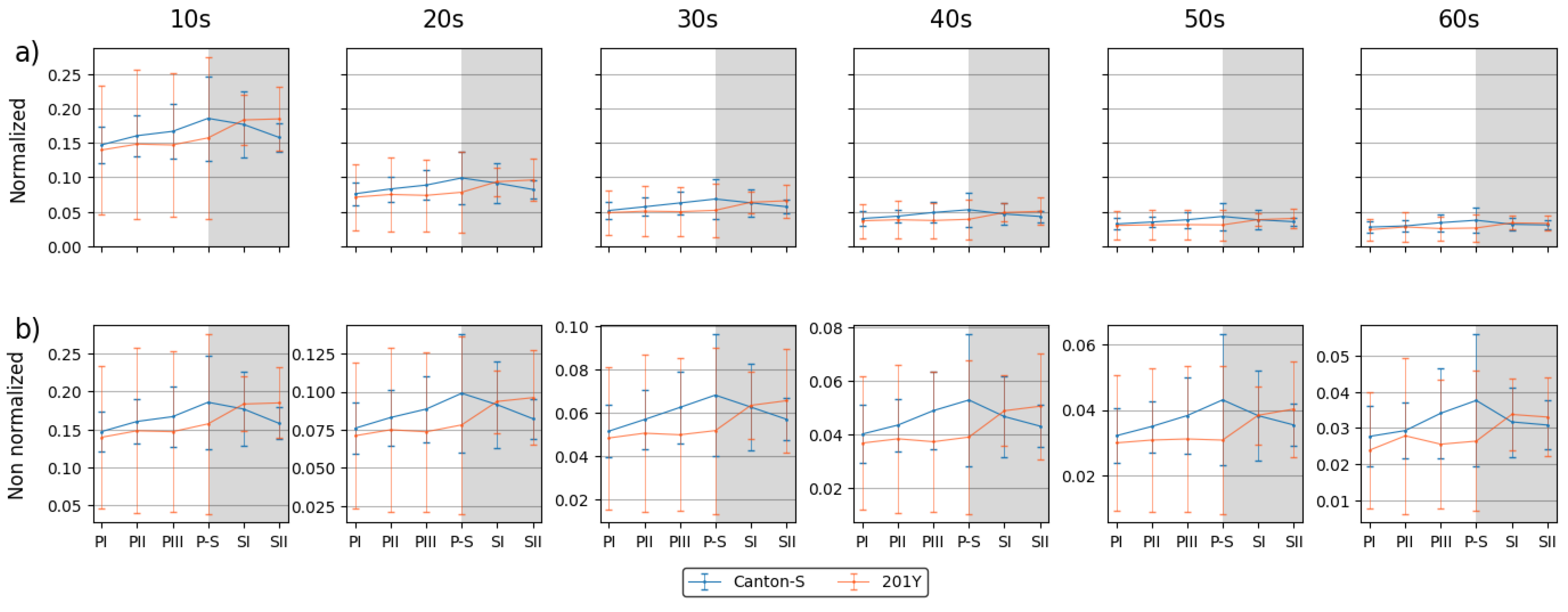

Figure 7 presents the

I-index for the cumulated movement positions across the entire observation arena for time windows of 10 s to 60 s under normalization. Generally, the values were narrow in a low range. The

I-index was higher at a window size of 10 s (peaking at 0.19), decreasing dramatically as the time window increased from 20 s (peaking at 0.10)(

Figure 7a).

The trend in the

I-index values over time was generally consistent between the time windows (

Figure 7b). The

I-index peaked during P-S (0.04-0.19) for Canton-S, indicating that the isolation of the individuals was lowest during P-S. For 201Y, the

I-index was low during the photophase (0.03–0.15) and increased afterward during the scotophase (0.03–0.18). The

I-index according to the light phase followed a similar pattern to that for speed for both strains (

Figure 4a). For Canton-S, the

I-index and the speed both peaked during the same light phase (P-S). The trend in

I-index values over time were also similar to the cluster number with ε = 4 mm (

Figure 6a) for Canton-S. The pattern of change in the

I-index for 201Y was similar to that for the speed in the overall observation arena (

Figure 4a). The SD range for the

I-index was broader overall for 201Y than for Canton-S and during the photophase than during the scotophase.

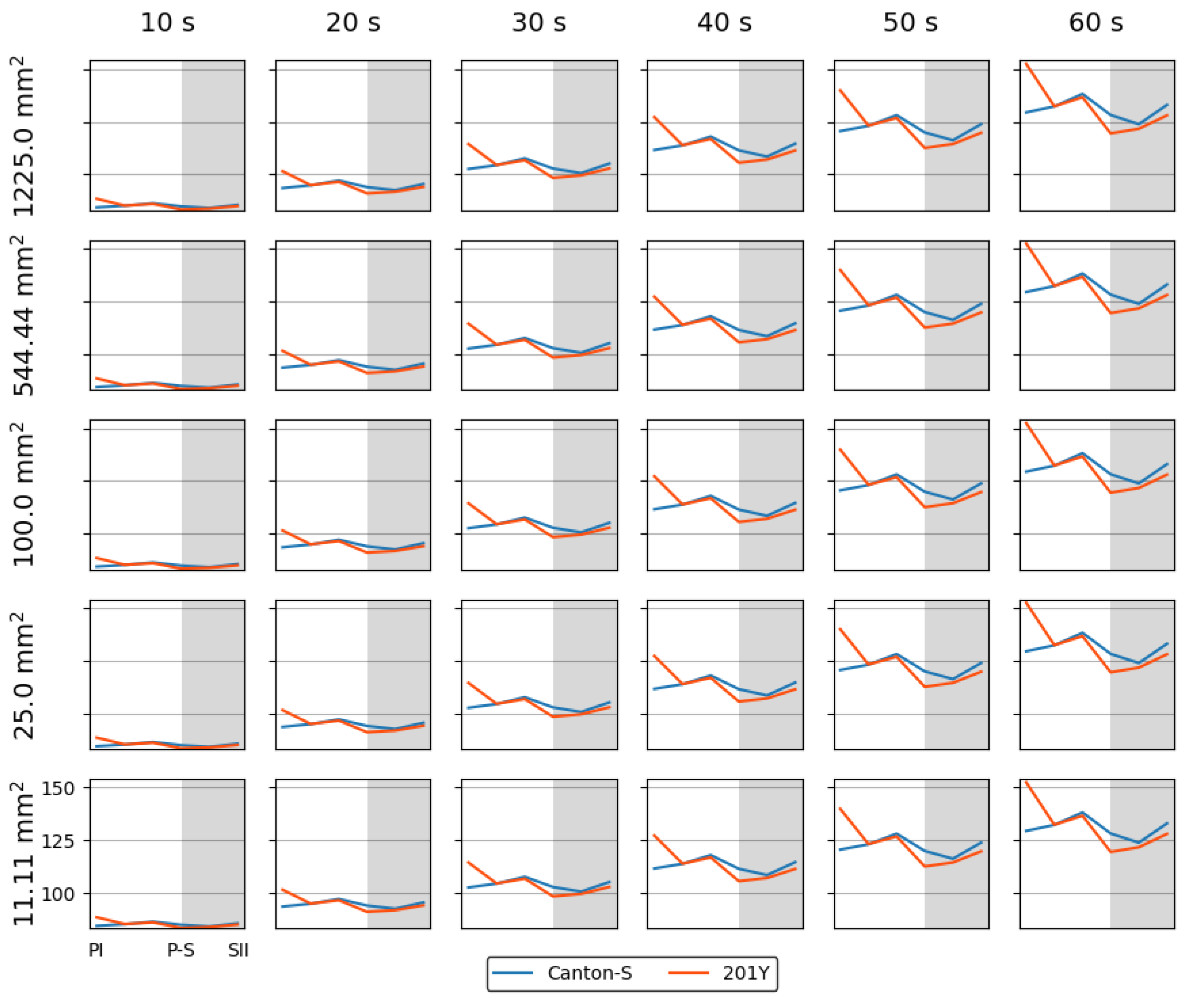

While the

I-index describes the degree of individual isolation, mean crowding represents the local crowdedness within a particular spatial unit. Mean crowding was obtained according to time window sizes between 10 s and 60 s and spatial scales between 11.1 mm

2 and 1,225.0 mm

2 to determine the optimal unit size for space and time (

Figure A2). Overall, the trend over time for the mean crowding was similar between the spatial size and time windows. However, the mean crowding values gradually increased with the time window size (

Figure A2) in a manner similar to the cluster number (

Figure A1).

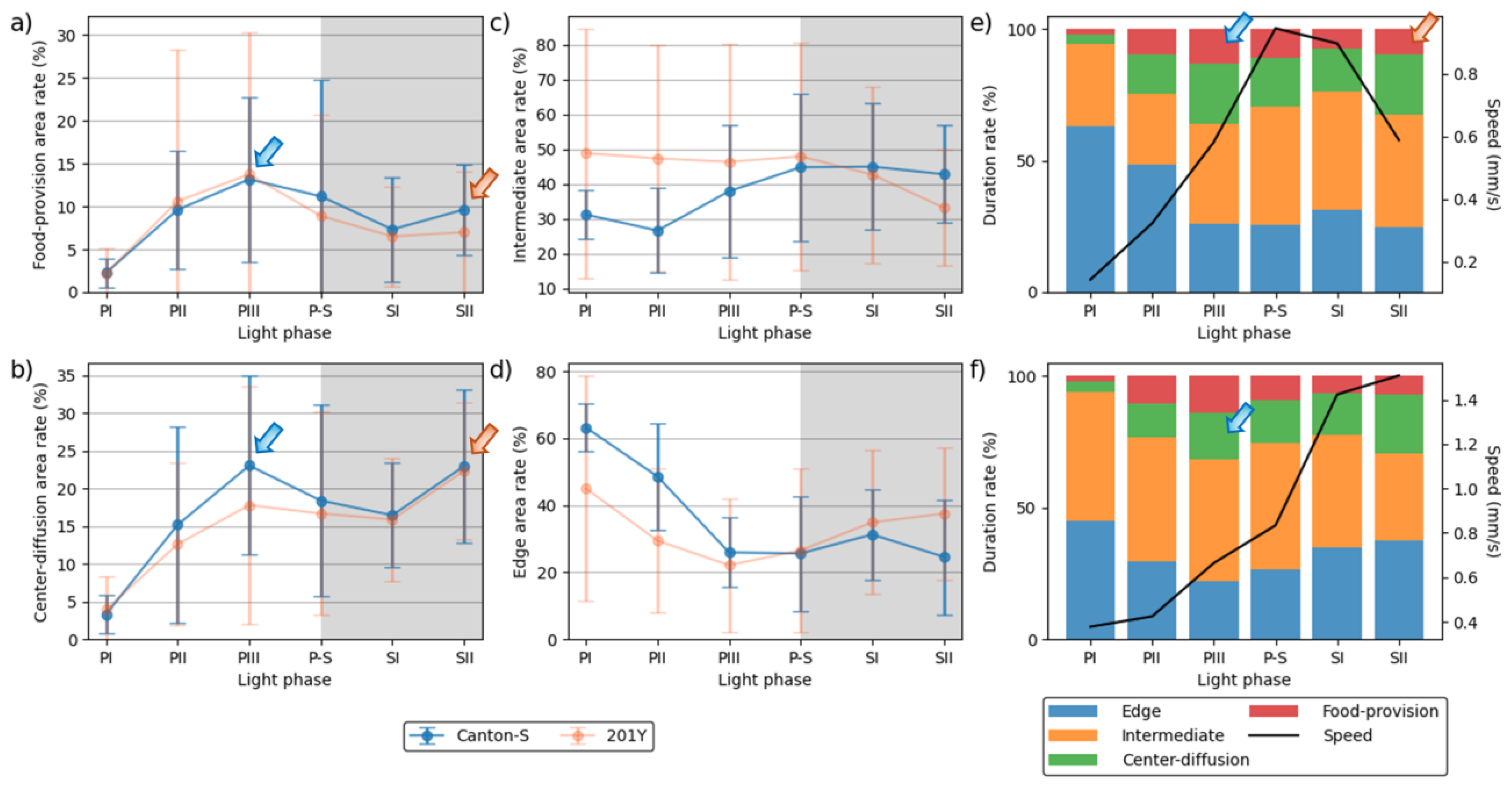

The trends in the mean crowding values across the light phases with a spatial unit size of 25 mm

2 and 100 mm

2 and a window size of 30 s were selected for detailed comparison (

Figure 6c,d). The overall trends over time were similar between the two spatial unit sizes and the two strains. These trends over time for the mean crowding were also similar to that for the duration rate overall in the food-provision and center-diffusion areas (

Figure 5a,b), with two peaks observed during the photophase and scotophase (blue and orange arrows, respectively,

Figure 6c,d).

A slight difference was observed between Canton-S and 201Y during PI with a spatial unit size of 100 mm

2, being higher for 201Y than for Canton-S during this phase (

Figure 6d). The SD range was also broader overall for 201Y than for Canton-S, especially during the photophase.

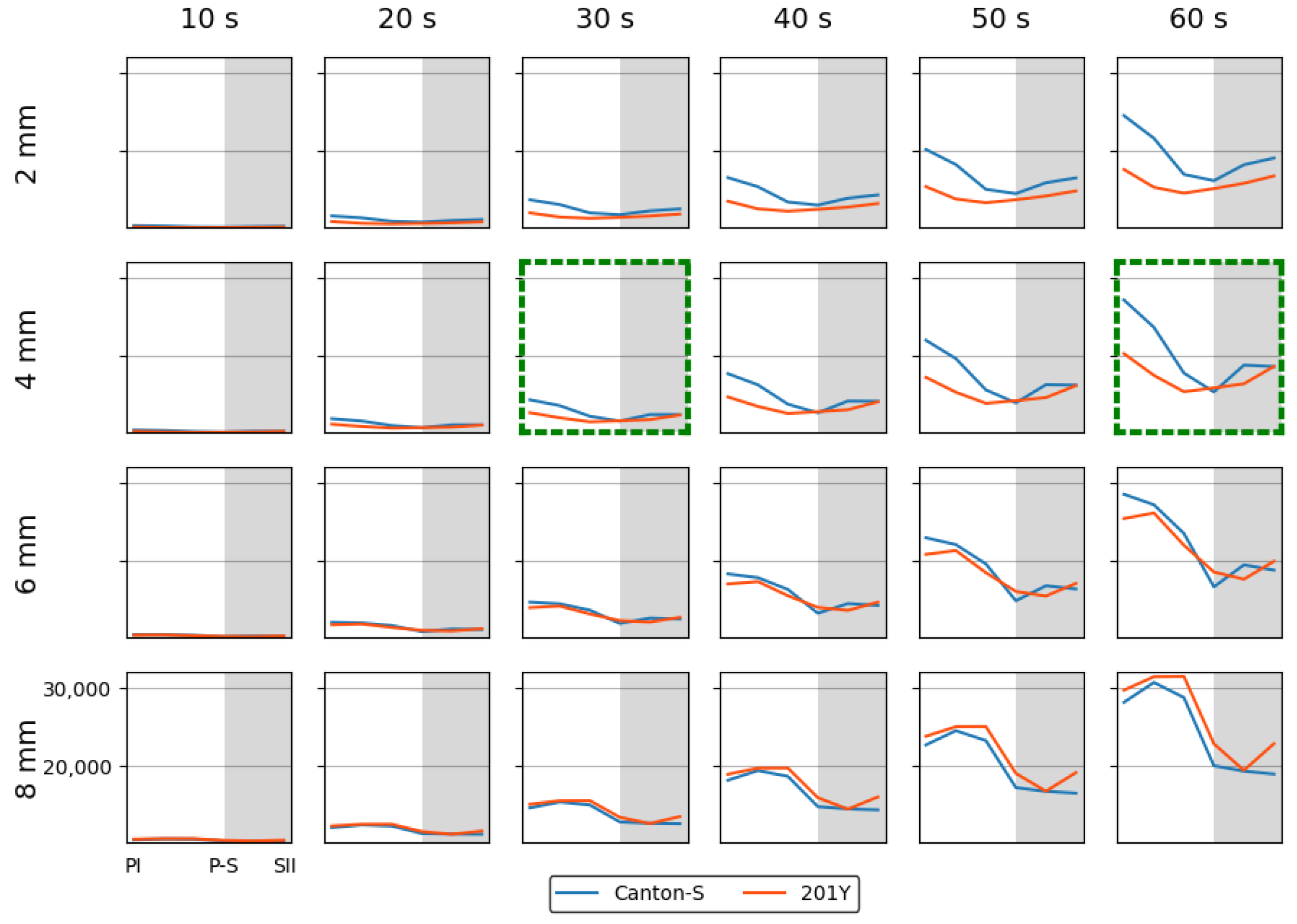

The SSI was also measured across different threshold distances and time window sizes as listed in

Figure A3. While the SSI exhibited generally similar trends, the values increased as both the spatial distance and the time window size increased. With a threshold distance of 6 mm or lower, the SSI was higher for Canton-S and lower for 201Y. However, with a threshold distance of 8 mm, the SSI was lower for Canton-S and higher for 201Y (see the two green dotted rectangles shown as examples in

Figure A3).

Although 4 mm is close to the critical distance for the SSI for

Drosophila [

2,

39], we investigated the SSI with a threshold distance of 8 mm with the same time unit of 30 s for the purpose of comparison (

Figure 6e,f). The shape of the trend in the SSI with a threshold distance of 4 mm was the opposite of that for the cluster number (

Figure 6a) and similar to that for mean crowding (

Figure 6c). Genetic differences in the SSI were found at the threshold distance of 4 mm; in particular, the SSI values were substantially lower for 201Y than for Canton-S, especially during the photophase (

Figure 6e).

The trend in the SSI across the light phases at a threshold distance of 8 mm exhibited different patterns, with high values during PII ~ PIII (

Figure 6f). The SSI values were remarkably similar between the two strains, with a maximum during PII (10,637.24) and a minimum (5,082.12) during SII for Canton-S, compared to a maximum during PIII (10,997.26) and a minimum during SI (5,116.39) for 201Y. SDs were overall higher for 201Y than for Canton-S, with SDs exceptionally high in photophase with the threshold distance of 8 mm for this strain.

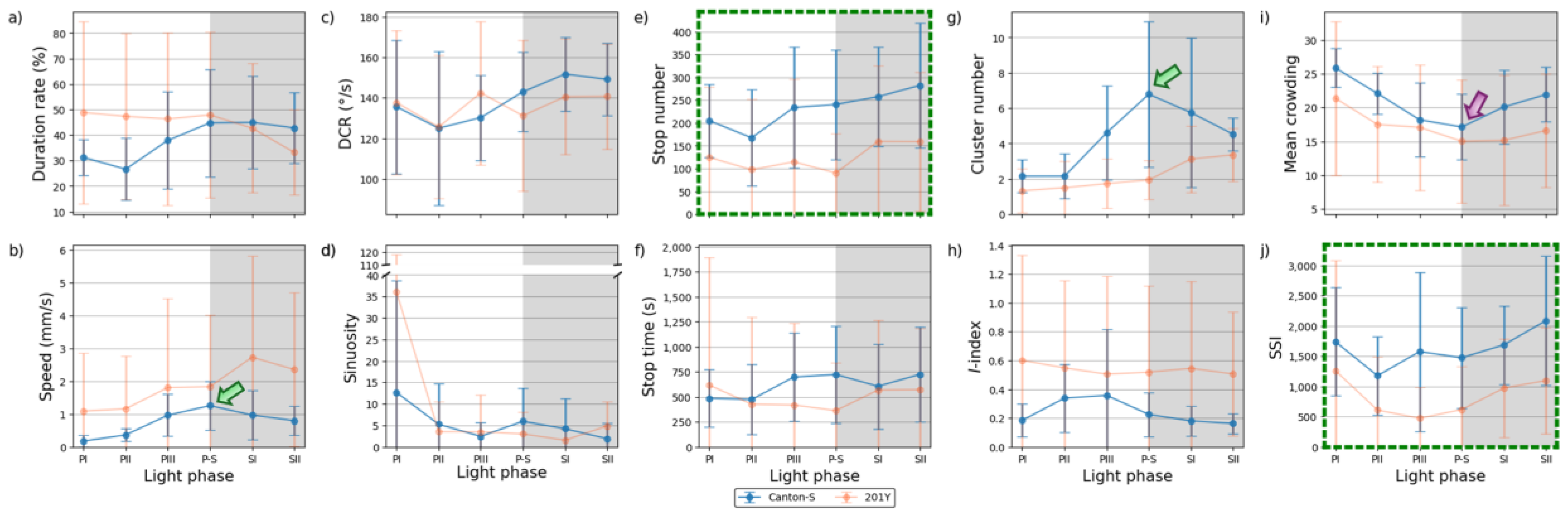

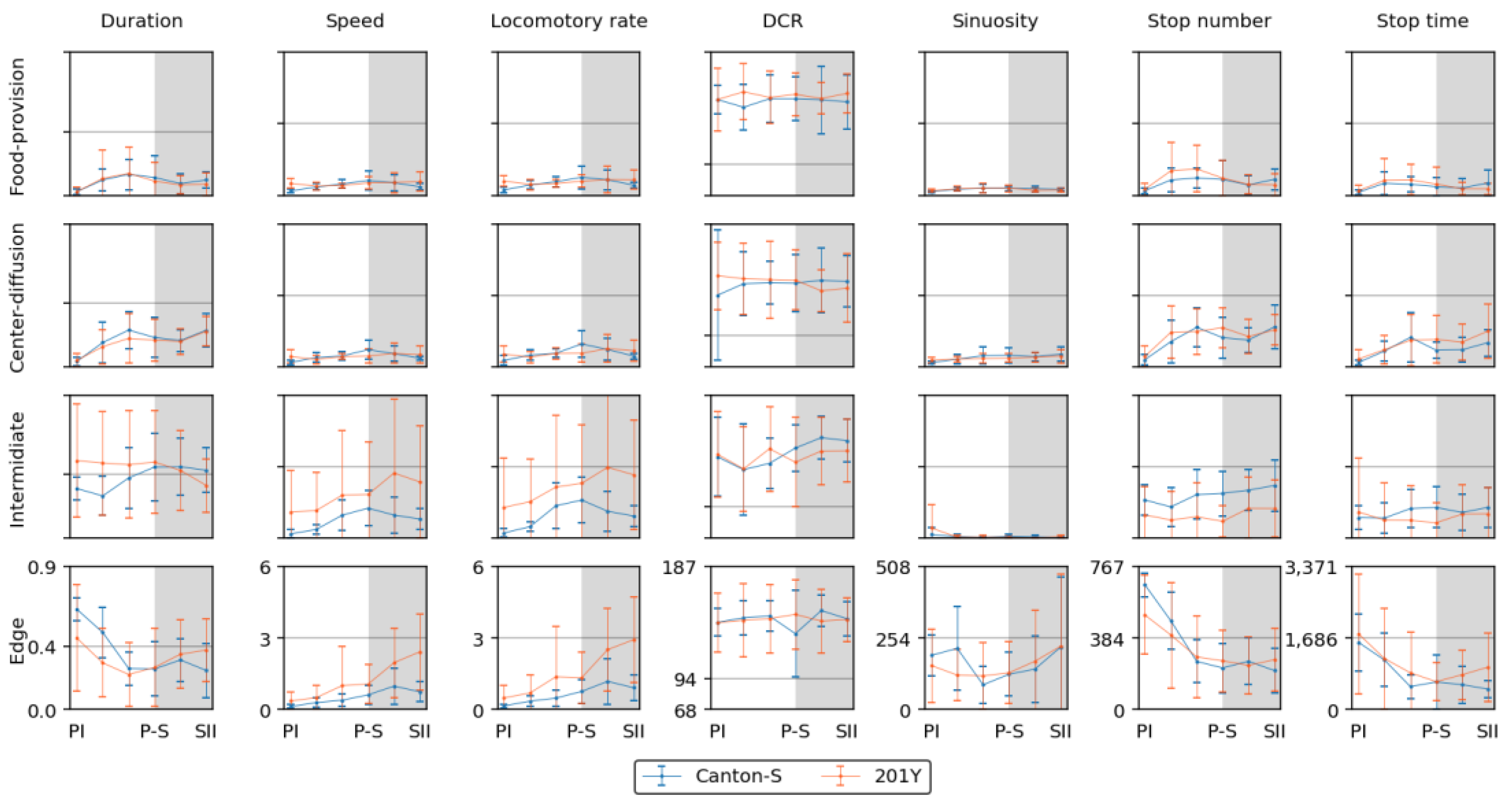

3.4. Comparison of the Parameters Between Micro-Areas

Figure 8 presents overall view of the movement parameters with normalization for the micro-areas with a time window size of 30 s. The trends in the movement parameters over time were generally similar between the food-provision and center-diffusion areas, while these trends were variable in the intermediate and edge areas. In particular, the motility and sessility parameters were more variable between the light phases in the intermediate and edge areas (

Figure 8). Sinuosity exhibited high variability in the edge area, while it was more stable with low values in the other micro-areas. The DCR was consistently observed within a limited range around an average of 140.9 °/s (though the change in direction, i.e., right or left, was not considered) across the light phases, indicating that large directional changes were observed during the 1 s time unit for group movement. Genetic differences in the motility parameters were also clearly observed in the intermediate and edge areas.

Figure 9 shows overview of the dispersion parameters with normalization for the micro-areas with a time window size of 30 s and with a threshold distance of 4 mm for the cluster number and SSI, a lattice size of 25 mm

2 for the mean crowding, and the entire observation arena (19,600.0 mm

2) for the

I-index. Similar to movement parameters, the dispersion parameters were more variable in the intermediate and edge areas. The cluster number and the

I-index were high in the intermediate area for Canton-S in accordance with the duration rate, while the cluster numbers were low in the food-provision and center-diffusion areas. The

I-index was particularly high in the intermediate area, especially for 201Y, indicating a low degree of individual isolation. The cluster number and SSI were characterized by high values with a difference between the two strains at the edge of the area (

Figure 9).

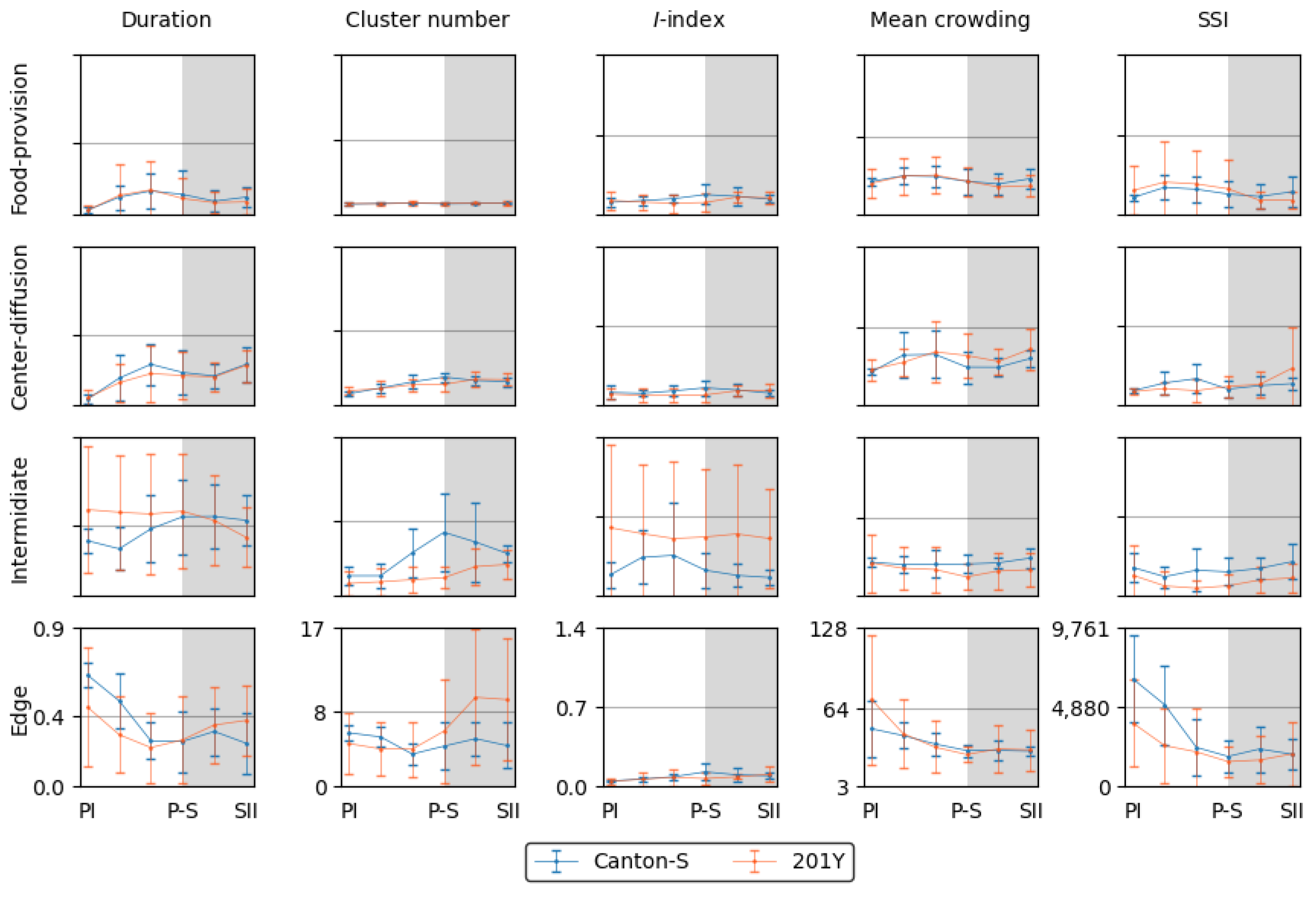

The movement and dispersion parameters are presented together for each micro-area in

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, focusing on trends over time. The trends for the parameters were similar overall between the resource supply areas (i.e., food and humidity), while those in areas related to activity (i.e., open space in the intermediate area and edge) varied greatly.

Coinciding trends were found for some measured parameters for Canton-S across the light phases depending on the micro-area. In the food-provision area, two major trends were observed over time. The first trend was a single peak for speed (0.6 mm/s) and the

I-index (0.2) during P-S (green arrows,

Figure 10b,h), while the second trend was two peaks during PII ~ PIII and SII for the duration rate (PIII: 13.1 %; SII: 9.6 %), stop number (PIII: 135.9; SII: 55.5), stop time (PII: 357.0 s; SII: 145.0 s), cluster number (PIII: 1.2; SII: 1.2), mean crowding (PII: 27.0; SII: 25.2), and SSI (PII: 1,645.5; SII: 1,367.5) (blue and orange arrows,

Figure 10a,e–g,i,j). Most of the dispersion parameters except for the

I-index exhibited two peaks in the food-provision area. The coinciding parameters with two peaks reflected local aggregations for feeding along with maximum durations in the food provision area.

Sinuosity exhibited a unique pattern with an early increase during the photophase to reach the highest level during PIII ~ P-S, followed by a slight decrease during the scotophase for Canton-S in the range of 13.0–24.7 (

Figure 10d). The DCR was stable across the light phases at around 148.6 °/s (

Figure 10c).

When comparing Canton-S and 201Y, the trends according to the light phase were substantially different for the speed and

I-index, whereas similar patterns were observed over time for the other parameters. While Canton-S had a maximum speed during P-S (0.6 mm/s) and a clear diel difference, the diel difference for 201Y was less distinct, with low values during the photophase (0.4 mm/s) and a high value during the scotophase (0.6 mm/s) (

Figure 10b). The

I-index was low overall (0.10–0.12) until P-S, followed by an increase during SI ~ SII (0.14–0.15) for 201Y, which was in contrast to the single peak during P-S for Canton-S (

Figure 10h). The stop number and stop time also differed, with higher averages during the photophase (135.9 and 357.0 s, respectively) and lower averages during SII (55.5 and 149.5 s, respectively) for 201Y than for Canton-S (

Figure 10e,f).

SDs were variably expressed according to parameters, light phases and micro-areas (vertical bars,

Figure 10-12). Since the parameter values were not normalized, the degree of variability cannot be comparable with other parameters objectively in these figures The quantitative degree of variability, expressed as coefficient of variation (CV; ratio of SD to mean) of measured parameters, will be discussed in ‘Section 4.5 Data variability and statistical differentiation’. In

Figure 10-12, relative SD sizes across light phases are described in different parameters in two strains.

In the food-provision area for 201Y, distinctively high SDs were observed in photophase with duration rate, stop number and time, and SSI (

Figure 10a,e,f,j) and in scotophase with speed (

Figure 10b). The cluster number had intermittently high SDs in photo- and scoto-phases for 201Y (

Figure 10g). Outstanding SDs were relatively fewer for Canton-S than for 201Y. SDs were high in scotophase with speed, mean crowding and

I-index (

Figure 10b,j,i), and were intermittently high in photophase with duration rate and sinuosity Canton-S (

Figure 10a,d).

The parameter trends in the center-diffusion area (

Figure 11) were generally similar to those for the food-provision area (

Figure 10). Single peaks during P-S were observed for the speed (0.7 mm/s), cluster number (3.0), and

I-index (0.15) for Canton-S (

Figure 11b,g,h). A single peak was also observed for the cluster number during P-S in the center-diffusion area (

Figure 11g), whereas the cluster number had double peaks in the food provision area (

Figure 10g). Sinuosity also exhibited double peaks in the center-diffusion area during P-S (40.5) and SII (44.7) (

Figure 11d), contrary to the trend of sinuosity in the food-provision area that showed the highest level during PIII ~ P-S for Canton-S (

Figure 10d). Similar to the case of the food provision area the coinciding parameters with two peaks reflected local aggregations for obtaining humidity along with maximum durations in the center-diffusion area.

Figure 11.

Movement and dispersion parameters in the center-diffusion area across light phases for Canton-S and 201Y of D. melanogaster. (a) Duration rate, (b) speed, (c) DCR, (d) sinuosity, (e) stop number, (f) stop time, (g) cluster number, (h) I-index, (i) mean crowding and (j) SSI.

Figure 11.

Movement and dispersion parameters in the center-diffusion area across light phases for Canton-S and 201Y of D. melanogaster. (a) Duration rate, (b) speed, (c) DCR, (d) sinuosity, (e) stop number, (f) stop time, (g) cluster number, (h) I-index, (i) mean crowding and (j) SSI.

The sinuosity, cluster number, mean crowding, and SSI (

Figure 11d,g,i,j) were considerably different for 201Y compared with Canton-S in the center-diffusion area, while the other parameters had similar trends between two strains to those observed for the food-provision area. The sinuosity exhibited two peaks over time for Canton-S and a linear increase toward the scotophase for 201Y (

Figure 11d). Mean crowding and SSI also had two peaks for Canton-S, whereas these peaks were not observed for 201Y (

Figure 11i,j). The cluster number had a single peak during P-S for Canton-S, which was in contrast to the linear increase observed for 201Y (

Figure 11g). Although similar, minor differences were found in the stop number and stop time between the two strains, with higher stop numbers (PII ~ P-S: 167.2; SII: 213.2 on average) and stop times (P-S: 641.1 s; SII: 839.4 s on average) for 201Y (

Figure 11e,f).

SDs in the center-diffusion area were observed with similarities and differences compared to the food-provision area. For 201Y, high SDs were observed in photophase with duration rate and stop number (

Figure 11a,e) and in scotophase with speed, mean crowding and SSI (

Figure 11b,i,j). The stop time was intermittently high in both photo- and scoto-phases (

Figure 11f). In Canton-S, high SDs were observed in photophase with duration rate, DCR and stop time (

Figure 11a,c,f) and in scotophase with speed (

Figure 11b). The stop number was intermittently high in both photo- and scoto-phases in Canton-S (

Figure 11e). It is noted that high SDs of duration rate and speed were observed in photophase and scotophase, respectively, in both strains in the food-provision and center-diffusion areas commonly (

Figure 10a,b and

Figure 11a,b). Extremely high SDs were observed with mean crowding and SSI during SII for 201Y compared with Canton-S (

Figure 11i,j), whereas SD of DCR was outstandingly high during PI for Canton-S compared with 201Y (

Figure 11c).

In the intermediate area, substantial differences were found in the parameter trends across the light phases (

Figure 12) compared to the areas for resource provision. Increases were observed for the duration rate (21.5 % on average), speed (0.3 mm/s on average), stop number (81.9 on average), and stop time (199.2 s on average), compared with the center-diffusion area for Canton-S, while a decrease was observed for sinuosity (28.1 on average). The trend for speed in the intermediate area (green arrow,

Figure 12b) was similar to that observed for the food-provision and center-diffusion areas, with a single peak during P-S for Canton-S. The two peaks observed for the number of parameters during the photophase and scotophase in the food-provision and center-diffusion areas were not observed in the intermediate area.

Figure 12.

Movement and dispersion parameters in the intermediate area across light phases for Canton-S and 201Y of D. melanogaster. (a) Duration rate, (b) speed, (c) DCR, (d) sinuosity, (e) stop number, (f) stop time, (g) cluster number, (h) I-index, (i) mean crowding and (j) SSI.

Figure 12.

Movement and dispersion parameters in the intermediate area across light phases for Canton-S and 201Y of D. melanogaster. (a) Duration rate, (b) speed, (c) DCR, (d) sinuosity, (e) stop number, (f) stop time, (g) cluster number, (h) I-index, (i) mean crowding and (j) SSI.

In the intermediate area, a number of parameters were low during the photophase and high during the scotophase, including the duration rate (photophase: 31.9 %; scotophase: 43.9 %), speed (0.5 mm/s and 0.9 mm/s, respectively), and stop number (202.0 and 269.9, respectively) for Canton-S (

Figure 12a,b,e). Except for the high value during PI (12.7), sinuosity was generally stable (4.0 on average) afterward (

Figure 12d). The DCR was slightly variable (139.1 on average) in the intermediate area (

Figure 12c).

Dispersion parameter patterns were also substantially different from those of the food-provision and center diffusion areas (

Figure 12g–j). The cluster number had a single peak during P-S (6.8), matching the peak for speed (

Figure 12b,g). The trends for the

I-index, mean crowding, and SSI were different overall from each other for Canton-S. For mean crowding, the minimum (17.1) was observed in the intermediate area (purple arrow,

Figure 12i). The

I-index had a peak early during PIII (

Figure 12h). Coinciding trends were also observed between parameters; the trend in the SSI was very similar to that for the stop number (solid rectangles,

Figure 12e,j).

Differences in the parameters between Canton-S and 201Y were observed in the intermediate area. The duration rate differed between light phases, being higher in the photophase (47.5 % on average) and lower in the scotophase (37.9 % on average) for 201Y than for Canton-S (

Figure 12a). Although the trend in the speed was similar between the two strains in the center-diffusion area (

Figure 11b), the speed for 201Y (1.8 mm/s) was substantially higher overall than for Canton-S (0.8 mm/s) (

Figure 12b) in the intermediate area. This suggested the high speeds observed for 201Y overall originated from high speeds in the intermediate area, especially during the scotophase. In accordance with this, the stop number was consistently lower for 201Y (124.3) than for Canton-S (231.1) across the light phases (

Figure 12e). The stop time, however, did not differ significantly between the two strains except for a minor increase during PIII (697.1 s) and P-S (723.4 s) for Canton-S compared with 201Y (419.4 s and 362.7 s, respectively) (

Figure 12f).

For 201Y, comparing to the center-diffusion area, increases in parameter values in the intermediate area were observed for duration rate (44.4 %) and speed (1.8 mm/s) (

Figure 12a,b), while decreases were observed for sinuosity (8.8), stop number (124.3), and stop time (494.3 s) on average (

Figure 12d–f). Sinuosity was much higher during PI for 201Y (36.1) than for Canton-S (12.7), indirectly indicating a high degree of searching around activity for 201Y. The patterns for the stop number and SSI over time were remarkably similar for both 201Y and Canton-S (dotted green rectangles,

Figure 12e,j), suggesting that the balance between attraction and repulsion with regard to neighboring individuals through frequent stops was preserved in both wild type and the mutant.

The SD patterns in the intermediate area were substantially different from those observed in the food-provision and center-diffusion areas. In Canton-S, SDs of many parameters were relatively stable including duration rate, speed, stop number and time and mean crowding (

Figure 12a,b,e,f,i). SDs were intermittently high in photophase with DCR, sinuosity and

I-index (

Figure 12c,d,h), and high in scotophase with cluster number (

Figure 12g). SD of SSI was sporadically high in both photo- and scoto-phases for the same strain (

Figure 12j). For 201Y, SDs were overall high with duration rate, speed, stop time,

I-index and mean crowding (

Figure 12a,b,f,h,i), and low with cluster number (

Figure 12g) compared to Canton-S. Within 201Y, SDs were high in photophase in variable periods with duration rate, DCR, stop time (

Figure 12a,c,f), and intermittently high in both photo- and scoto-phases with speed (

Figure 12a). It is noted that SDs were exceptionally high with sinuosity during PI for both strains (

Figure 12d).

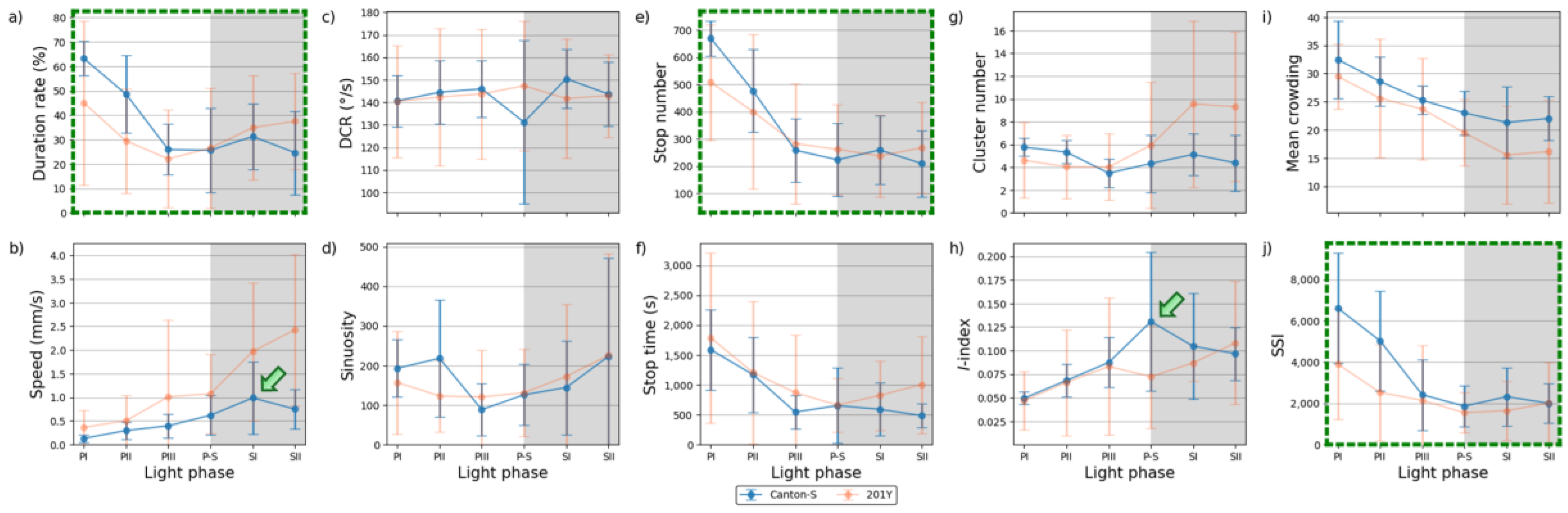

The parameters in the edge area were substantially different from those in the other micro-areas (

Figure 13). Peaks often observed in the resource provision areas were not found in the edge area for Canton-S. The peak for the speed (1.0 mm/s) was observed slightly later during SI in the edge area (green arrow,

Figure 13b), compared with the peak during P-S in the other areas.

Figure 13.

Movement and dispersion parameters in the edge area across light phases for Canton-S and 201Y of D. melanogaster. (a) Duration rate, (b) speed, (c) DCR, (d) sinuosity, (e) stop number, (f) stop time, (g) cluster number, (h) I-index, (i) mean crowding and (j) SSI.

Figure 13.

Movement and dispersion parameters in the edge area across light phases for Canton-S and 201Y of D. melanogaster. (a) Duration rate, (b) speed, (c) DCR, (d) sinuosity, (e) stop number, (f) stop time, (g) cluster number, (h) I-index, (i) mean crowding and (j) SSI.

A substantial increase in the average sinuosity (165.2 on average) was observed in the edge area compared with the intermediate area (5.4 on average) for Canton-S (

Figure 12d and 13d). A clear increase was also observed for the average SSI (3,371.9 on average) in the edge area (

Figure 13j) compared with the intermediate (1,624.2 on average) and other areas, indicating a strong aggregation in the area close to boundary in the observation arena. Exceptionally high values were observed for the average duration rate (55.9 % on average), stop number (573.2 on average), and stop time (1,377.9 s on average) during PI ~ PII in the edge area (

Figure 13a,e,f). The values later stabilized at an average of 26.9 % for the duration rate, 237.9 for the stop number, and 566.7 s for the stop time in the edge area. The DCR was stable with 142.9 °/s on average, although slight variation was observed during P-S.

The dispersion parameters in the edge area were also substantially different from those in the other micro-areas (

Figure 13g-j). A peak during P-S was observed for the

I-index (0.13) for Canton-S (green arrow,

Figure 13h), matching the peak for speed (green arrow,

Figure 13b). While the cluster number (4.7 on average) was stable across the light phases, high values were observed in early photophase for mean crowding (48.5) and the SSI (6,610.2) for Canton-S, but these decreased and stabilized during the scotophase (31.3 and 2,158.5, respectively, on average) (

Figure 13i,j).

Differences in the behaviors of the two strains were also observed in the edge area. Of the movement parameters, the average duration rate was lower during the photophase (32.2 % on average) and higher during the scotophase (36.2 % on average) for 201Y compared with Canton-S (45.9 % and 28.0 % respectively, on average)(

Figure 12a). The speed was also substantially higher across the light phases for 201Y than for Canton-S(

Figure 12b). This difference was not great during the PI, but it continuously increased until SII, reaching 2.4 mm/s for 201Y compared to 0.8 mm/s for Canton-S (

Figure 13b). Together with the faster speeds in the intermediate area, the speed in the edge area during the scotophase contributed greatly to the increase in the total speed of 201Y (

Figure 4a). The trend in the stop number over time was similar between the two strains in the edge area (

Figure 13e), whereas the stop number differed between the two strains especially in photophase in the intermediate area (

Figure 12e). However, the DCR, sinuosity, stop number, and stop time were similar overall between the two strains (

Figure 13c,e,f).

Coinciding patterns were also observed between parameters in the edge area. The patterns over time for the duration rate, stop number, and SSI were very similar between Canton-S and 201Y (green dotted rectangles,

Figure 13a,e,j). The stop number and SSI were in accord in the intermediate area as stated above (green dotted rectangles,

Figure 12e,j), while the duration rate was added to this group in the edge area, with very high values observed during the early photophase. This coinciding trend for the stop number and SSI in the areas related to activity persisted between strains.

The data variability pattern in the edge area was broadly similar to those in the intermediate area while allowing some local differences. The SDs for 201Y were high with duration rate, speed, DCR, stop time, cluster number,

I-index and mean crowding compared with Canton-S (

Figure 13a-c,f,g-i), similar to the case of the intermediate area. SDs increased correspondingly with the values of speed and cluster increasing as the time progressed toward scotophase for 201Y (

Figure 13b,g). For Canton-S, SDs of many parameters were relatively stable including duration rate, speed, DCR, stop number and time, cluster number and mean crowding (

Figure 13a-c,e-g,i), broadly similar to the intermediate area. SDs were intermittently high in photophase with SSI (

Figure 13j) and high in scotophase with

I-index (

Figure 13h). SD of sinuosity was sporadically high in both photo- and scoto-phases in the same strain (

Figure 13d).

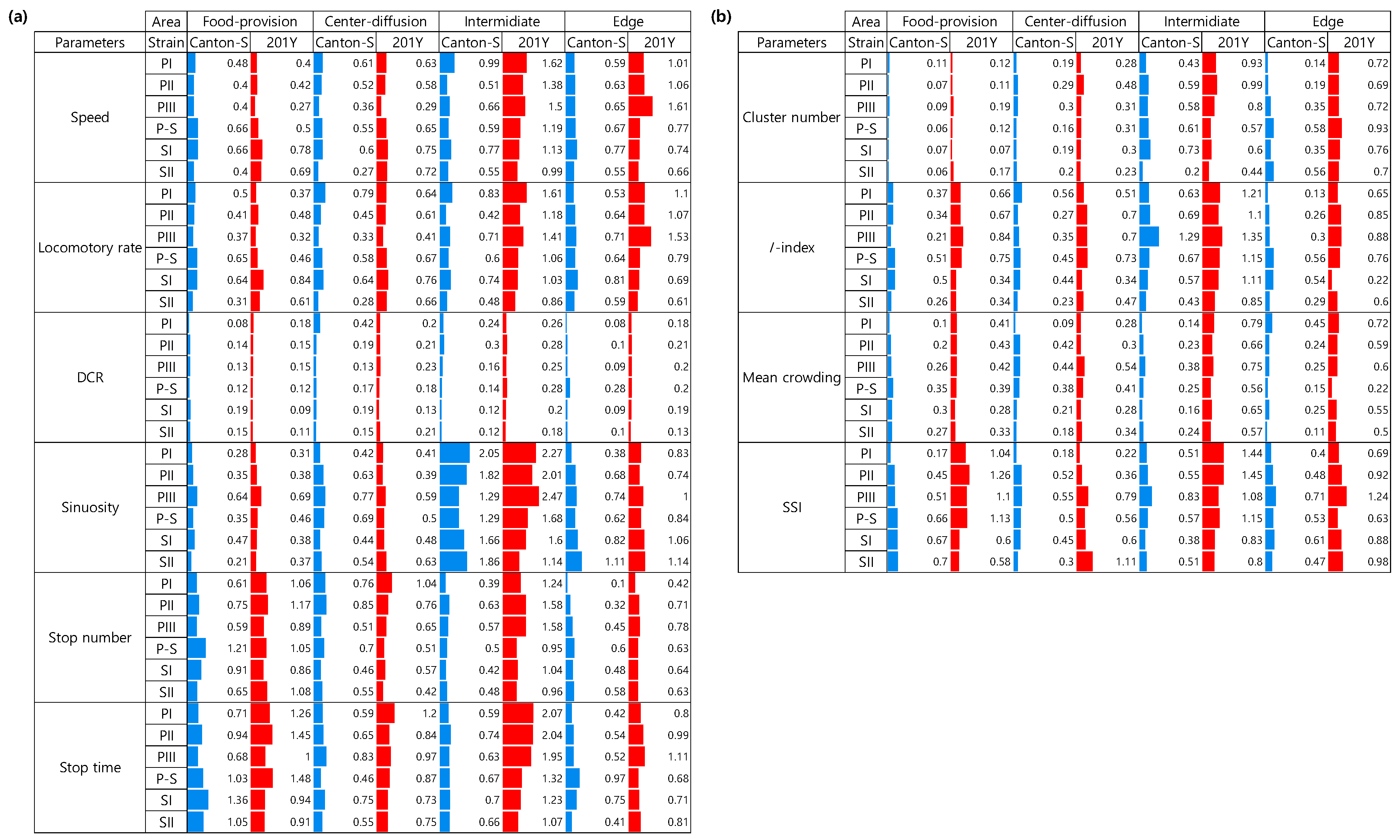

3.5. Data Variability and Statistical Differentiation

Because high variability was observed for the movement and dispersion parameters, the CV was used to compare the degree of variation in these parameters according to the micro-area, light phase, and strain. For the movement parameters, sinuosity overall exhibited high CVs for both strains (0.21–2.05 for Canton-S and 0.31–2.47 for 201Y) (

Figure 14a). In contrast, CVs were low overall for the DCR for both strains (0.08–0.42 and 0.09–0.28, respectively).

CVs were high overall in the areas related to activity compared with the areas related to resource supply. In the food-provision area, the stop number (0.61–1.21), stop time (0.68–1.36) had higher ranges than the other parameters for Canton-S (

Figure 14a). Stop number (0.46–0.85) and stop time (0.59–0.75) showed slightly high range of CVs than speed (0.27-0.61) and locomotory rate (0.28-0.79) in the center-diffusion area.

In the intermediate area, the

I-index (0.43–1.29) had a high CV range followed by sinuosity (1.29–2.05), speed (0.55–0.99), locomotory rate (0.42–0.83), and SSI (0.38–0.83) for Canton-S (

Figure 14a). In the edge area, the CV range was relatively low, being highest for sinuosity (0.38–1.11) and the locomotory rate (0.53–0.81).

The CVs for the movement parameters for 201Y were higher overall than those for Canton-S, while the CV trends within the micro-areas were similar (

Figure 14a). Higher CVs were found in the intermediate area than in the other micro-areas, with many parameters exhibiting CVs over 1.0, including the sinuosity (1.14–2.47), stop time (1.07–2.07), speed (0.99–1.62), locomotory rate (0.86–1.61), stop number (0.95–1.58), SSI (0.80–1.45), and

I-index (0.85–1.35) for 201Y (

Figure 14). Differences between the two strains were also observed in the edge area. While the CVs for sinuosity were not much different as stated above, those for the speed (0.66–1.61), locomotory rate (0.61–1.53), and SSI (0.63–1.24) were higher for 201Y than for Canton-S (0.55–0.77, 0.53–0.81, and 0.63–1.24, respectively).

Figure 14b presents the CVs for the dispersion parameters according to the micro-area and light phase. The CVs for the dispersion parameters were generally lower than those for the movement parameters.

Among the micro-areas, the CVs were higher in the intermediate area for the SSI (0.17–0.83 for Canton-S and 0.22–1.45 for 201Y) and the

I-index (0.13–1.29 and 0.22–1.35, respectively) compared with the other indices. The cluster number and mean crowding had low CVs in the food-provision (0.06–0.35 for Canton-S and 0.07–0.43 for 201Y) and center-diffusion areas (0.09–0.44 and 0.23–0.54, respectively) compared with the other micro-areas (

Figure 14b).

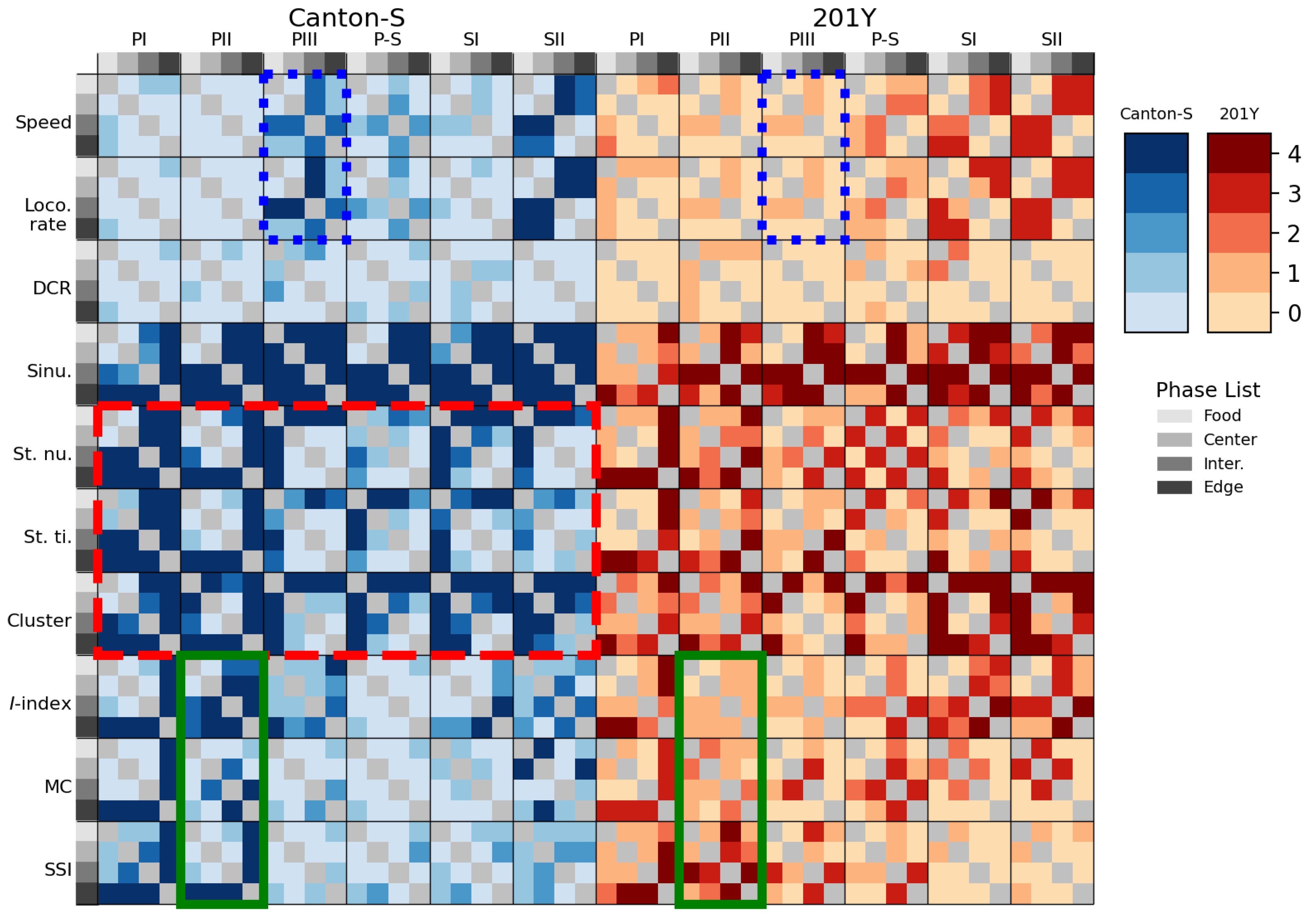

Due to the high variability of parameters, statistically significant differences were observed in cases where the values of the parameters varied strongly.

Figure 15 presents the statistical differentiation of the parameters between the micro-areas using Mann-Whitney U and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. For Canton-S, sinuosity was the most clearly differentiated movement parameters between the micro-areas during the light phases for both strains, whereas the DCR was not statistically different between these areas. Sessility (i.e., the stop number and stop time) and motility (i.e., the speed and locomotory rate) parameters exhibited some statistical differentiation between the micro-areas, light phases, and strains (

Figure 15).

The movement parameters, stop number and stop time and the dispersion parameter cluster number were statistically differentiated in the intermediate and edge areas during PI ~ PII and in the food-provision area during PIII–SII for Canton-S (red dashed rectangle,

Figure 15), indicating that the parameters for sessility and the cluster number were sensitive to differences in group behaviors between micro-areas. For the dispersion parameters, statistical differentiation was also observed for the

I-index, mean crowding, and SSI, primarily in the edge area during PI (the last column of each heatmap plot for each parameter).

In contrast, the motility parameters were not as statistically distinct as the other parameters, except for differences observed in the speed and locomotory rate during PIII (in the intermediate area; third column of the heatmap plot) and SII (in the intermediate and edge areas; third and fourth columns of the heatmap plots). The locomotory rate had a slightly stronger differentiation than the speed (

Figure 15).

The mutant 201Y exhibited similar statistical differentiation to Canton-S, but the degree of this differentiation was weaker for both movement and dispersion parameters (

Figure 15), confirming the broader data variability of parameters observed for 201Y (e.g.,

Figure 10–13). Unlike with the

I-index, the mean crowding and SSI during PII observed for Canton-S was not observed for 201Y (green solid rectangles,

Figure 15). Differences in the speed and locomotory rate observed for Canton-S were not observed for 201Y (two blue dotted rectangles,

Figure 15), indicating that differences in group behavior were weaker in the mutant.

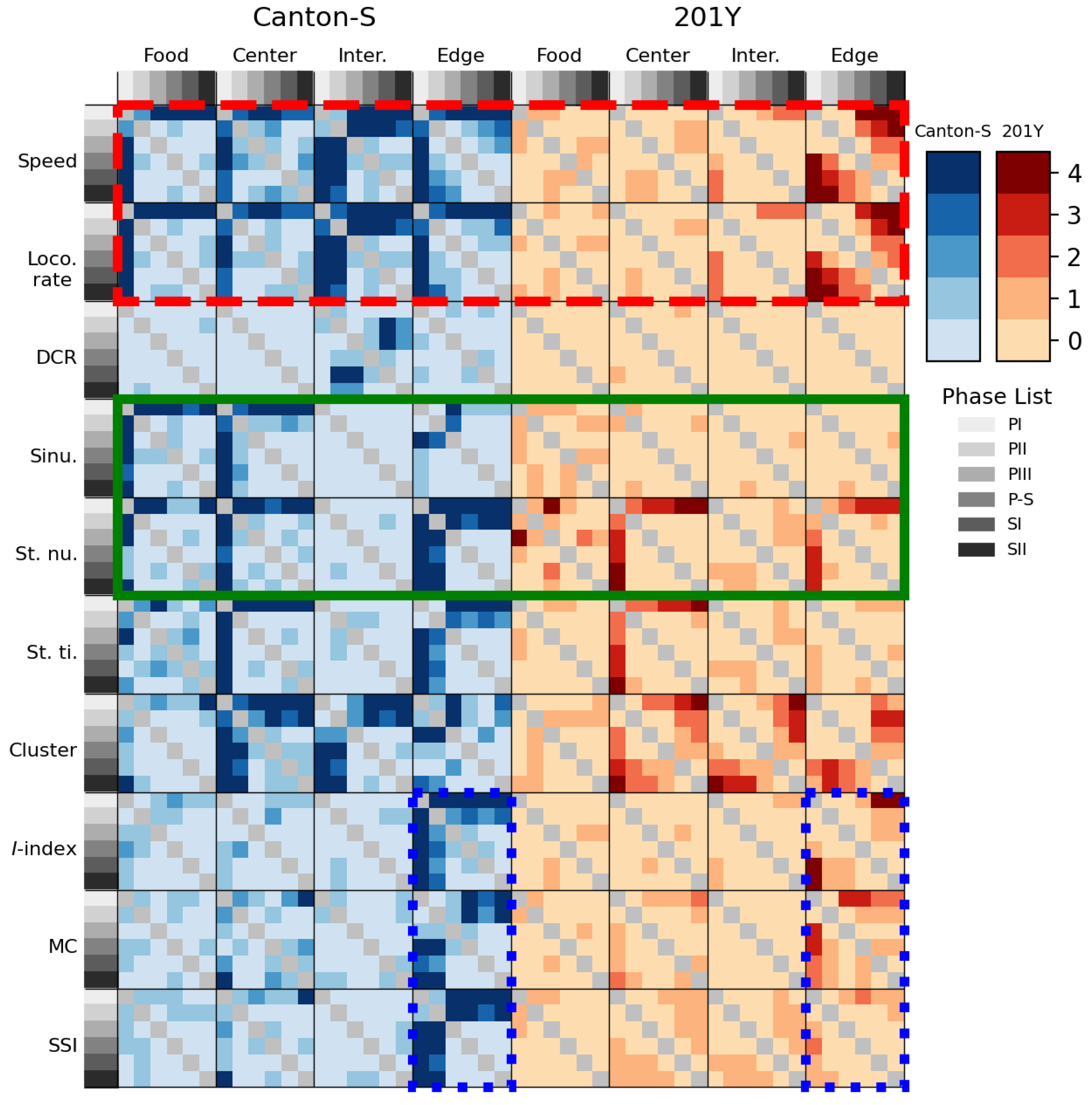

Figure 16 presents the statistical differentiation between light phases for the movement and dispersion parameters in each micro-area in two strains. Differentiation of parameters according to the light phrase was consistently observed in the edge area (the vertical column matching the edge area for Canton-S,

Figure 16), primarily during PI ~ PII (first and second columns within each heatmap plot). In the food-provision and center-diffusion areas, the motility and sessility parameters were statistically differentiated, while the cluster number in the dispersion parameters was differentiated in the center-diffusion area. The DCR was not statistically different except for a minor difference in the intermediate area. The

I-index, mean crowding, and SSI were not differentiable between the micro-areas except in the edge area.

Statistical differentiation between light phases for 201Y was much weaker compared with Canton-S (

Figure 16). No statistical differences were observed for 201Y except in the edge area and in the intermediate area. The statistical differences observed for the sinuosity, stop number, and stop time for Canton-S were not observed for 201Y, with only minor differences in the center-diffusion area for the stop number and stop time (green solid rectangle,

Figure 16). Strong statistical differentiation was observed for the speed and locomotory rate for Canton-S, but this differentiation was not observed in most areas except the edge area for 201Y (red dashed rectangle,

Figure 16). Similarly, the statistical differentiation observed for the

I-index, mean crowding, and SSI for Canton-S was not observed for 201Y (blue dotted rectangles,

Figure 16). These results indicated that the differences in the genetic make-up of 201Y more severely affected behaviors related to the light phases than the micro-areas.

Table 1 summarizes the statistical analysis of the movement and dispersion parameters for Canton-S and 201Y, with strong statistical differences highlighted in blue (

p < 0.05) and green (

p < 0.10) to show possibilities of separation between parameters with high variability in two strains.

Clear statistical differences were often observed in the parameters for sessility. In particular, the stop number was highly differentiated in the intermediate area, while the cluster number and SSI were highly differentiated in the intermediate area (

Table 1). The locomotory rate was slightly more strongly statistically differentiable than the speed with higher significance during PI and SII. Overall, the statistical differentiation matched the differences in the parameters observed between the micro-areas (

Figure 10–13).