Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

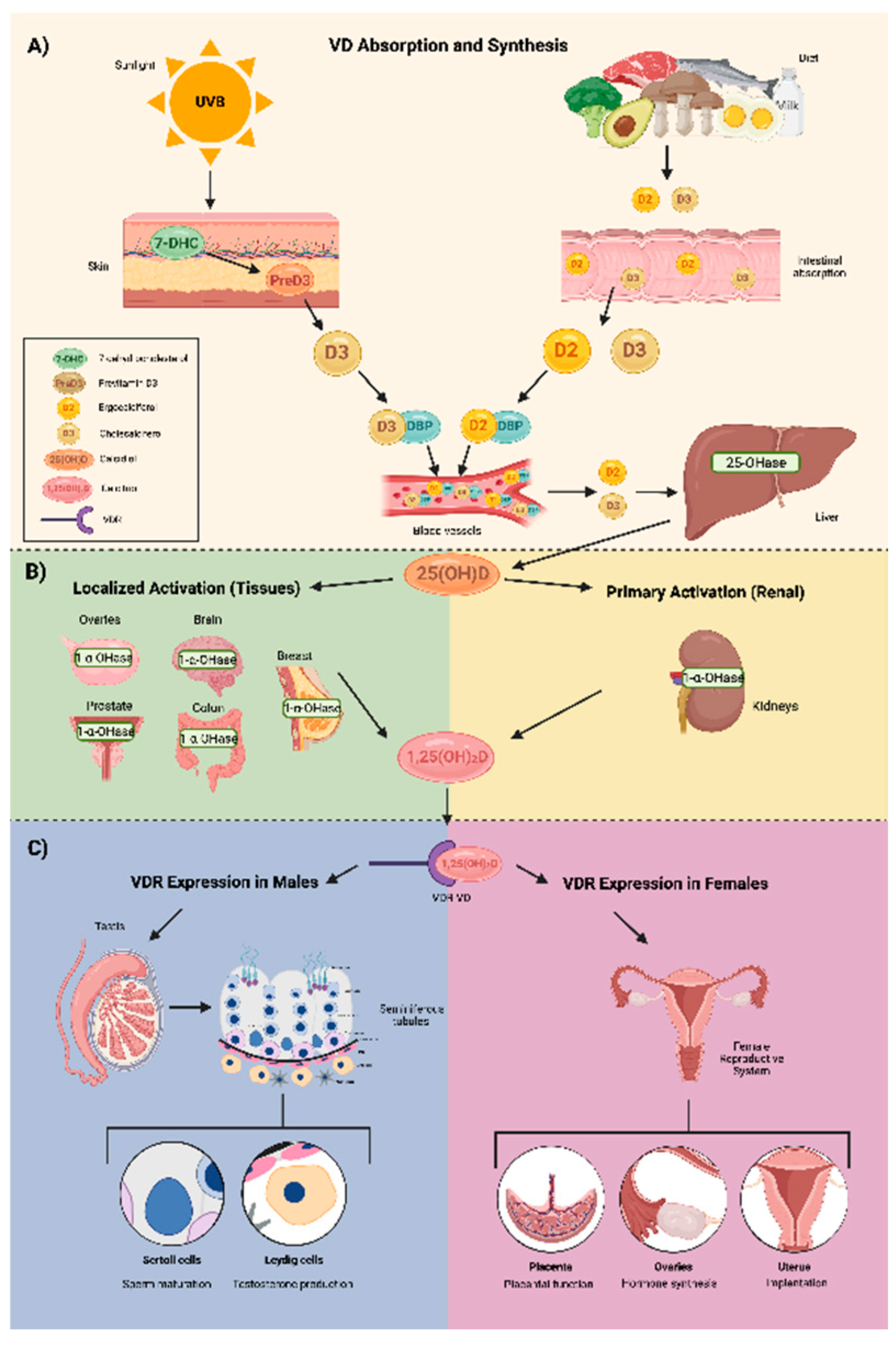

2. Vitamin D Structure and Metabolism

3. Vitamin D Deficiency

4. Correlation Between Vitamin D with Ovarian Reserve, Steroidogenesis, and Follicular Development

5. Vitamin D Receptor on Reproductive-Associated Tissues

6. Vitamin D and Fertility

7. Vitamin D and PCOS

8. Vitamin D and Endometriosis

9. Discussion

10. Conclusion

References

- Huhtakangas JA, Olivera CJ, Bishop JE, Zanello LP, Norman AW. The vitamin D receptor is present in caveolae-enriched plasma membranes and binds 1α, 25 (OH) 2-vitamin D3 in vivo and in vitro. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2660–71.

- Kahlon Simon-Collins M, Nylander E, Segars J, Singh BBK. A systematic review of vitamin D and endometriosis: role in pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. F&S Rev. 2022;4:1–14.

- Khurana, M., et al. (2021). Vitamin D and female reproductive health: A review of molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Reproductive Health Journal, 18(1), 123-134. [CrossRef]

- Bouillon R. Vitamin D: from photosynthesis, metabolism, and action to clinical applications, endocrinology: adult and pediatric: vitamin D, 7th ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier, 2015:1018–37.10.1016/B978-0-323-18907-1.00059-7.

- Christakos S, Seth T, Wei R, Veldurthy V, Sun C, Kim KI, Kim KY, Tariq U, Dhawan P. Vitamin D and health: beyond bone. MD Advis 2014;7:28–32.

- John, N., et al. (2022). Role of vitamin D in reproductive health: Implications for infertility and pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 107(9), 2301-2310. [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, M., et al. (2023). Vitamin D supplementation in assisted reproduction: Outcomes in IVF and ICSI cycles. Fertility and Sterility, 120(4), 718-725. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, N., et al. (2021). Association between vitamin D deficiency and reduced ovarian reserve: Implications for fertility. Fertility and Sterility, 115(5), 1092-1099. [CrossRef]

- Mohan A, Haider R, Fakhor H, Hina F, Kumar V, Jawed A, et al. Vitamin D and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023; 85(7):3506-3511. [CrossRef]

- Thomson RL, Spedding S, Buckley JD. Vitamin D in the aetiology and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012 Sep;77(3):343-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M., et al. (2022). Vitamin D as a potential therapeutic approach in endometriosis: A systematic review. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 154, 103462. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E., et al. (2020). The effect of vitamin D supplementation on endometriosis symptoms: A randomized trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 42(1), 11-18. [CrossRef]

- Lagana, A.S., Vitale, S.G., Ban Frangež, H., Vrtačnik-Bokal, E., D’Anna, R. (2017). Vitamin D in human reproduction: the more, the better? An evidence-based critical appraisal. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 21(18), 4243–4251.

- Pilz, S., Zittermann, A., Obeid, R., Hahn, A., Pludowski, P., Trummer, C., et al. (2018). The role of vitamin D in fertility and during pregnancy and lactation: A review of clinical data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2241. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.W., Lee, H.C. (2019). Vitamin D and health - The missing vitamin in humans. Pediatrics and Neonatology, 60(3), 237-244. [CrossRef]

- Fantini, C., Corinaldesi, C., Lenzi, A., Migliaccio, S., Crescioli, C. (2023). Vitamin D as a shield against aging. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(5), 4546. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zavala, N., López-Sánchez, G.N., Vergara-Lopez, A., Chávez-Tapia, N.C., Uribe, M., Nuño-Lámbarri, N. (2020). Vitamin D deficiency in Mexicans has a high prevalence: A cross-sectional analysis of patients from the Centro Médico Nacional 20 de noviembre. Archives of Osteoporosis, 15(1), 88. [CrossRef]

- Płudowski, P., Kos-Kudła, B., Walczak, M., Fal, A., Zozulińska-Ziółkiewicz, D., Sieroszewski, P., et al. (2023). Guidelines for preventing and treating vitamin D deficiency: A 2023 update in Poland. Nutrients, 15(3), 695. [CrossRef]

- Irani, M., Merhi, Z. (2014). Role of vitamin D in ovarian physiology and its implication in reproduction: A systematic review. Fertility and Sterility, 102(2), 460-468.e3. [CrossRef]

- Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jul 19;357(3):266-81. [CrossRef]

- Wortsman J, et al. "Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity." American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000.

- Silva, I.C.J., Lazzaretti-Castro, M. (2022). Vitamin D metabolism and extraskeletal outcomes: An update. Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 66(5), 748-755. [CrossRef]

- Várbíró, S., Takács, I., Tűű, L., Nas, K., Sziva, R.E., Hetthéssy, J.R., et al. (2022). Effects of Vitamin D on fertility, pregnancy, and polycystic ovary syndrome - A review. Nutrients, 14(8), 1649. [CrossRef]

- Pál É, Hadjadj L, Fontányi Z, Monori-Kiss A, Mezei Z, Lippai N, Magyar A, Heinzlmann A, Karvaly G, Monos E, Nádasy G, Benyó Z, Várbíró S. Vitamin D deficiency causes inward hypertrophic remodeling and alters vascular reactivity of rat cerebral arterioles. PLoS One. 2018 Feb 6;13(2):e0192480. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nandi, A., Sinha, N., Ong, E., Sonmez, H., Poretsky, L. (2016). Is there a role for vitamin D in human reproduction? Hormones Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigations, 25(1), 15-28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trujillo J, et al. "Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in postmenopausal women in Mexico, Chile, and Brazil." Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2018.

- Thacher TD, et al. "Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in women of reproductive age in Mexico." Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2017.

- Soto JR, Anthias C, Madrigal A, Snowden JA. Insights Into the Role of Vitamin D as a Biomarker in Stem Cell Transplantation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:500910.

- Sassi F, Tamone C, D'Amelio P. Vitamin D: Nutrient, Hormone, and Immunomodulator. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):1656. [CrossRef]

- Bacanakgil BH, İlhan G, Ohanoğlu K. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on ovarian reserve markers in infertile women with diminished ovarian reserve. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Feb 11;101(6):e28796. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moridi I, Chen A, Tal O, Tal R. The Association between Vitamin D and Anti-Müllerian Hormone: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1567. Published 2020 May 28. [CrossRef]

- Safaei Z, Bakhshalizadeh SH, Nasr Esfahani MH, Akbari Sene A, Najafzadeh V, Soleimani M, et al. Effect of Vitamin D3 on Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Granulosa Cells Derived from Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int J Fertil Steril. 2020;14(2):143-149. [CrossRef]

- Ling Y, Xu F, Xia X, Dai D, Xiong A, Sun R, Qiu L, Xie Z. Vitamin D supplementation reduces the risk of fall in the vitamin D deficient elderly: An updated meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2021 Nov;40(11):5531-5537. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H., et al. "Vitamin D and female fertility: A systematic review." Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2018.

- Ozkan S, Jindal S, Greenseid K, Shu J, Zeitlian G, Hickmon C, Pal L. Replete vitamin D stores predict reproductive success following in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2010 Sep;94(4):1314-1319. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J. M., et al. "Impact of vitamin D status on live birth rates in women undergoing IVF: A meta-analysis." Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2021.

- Rudick, B. M., et al. "Vitamin D deficiency and assisted reproductive outcomes: A retrospective study." Fertility and Sterility. 2020.

- Ekanayake DL, Małopolska MM, Schwarz T, Tuz R, Bartlewski PM. The roles and expression of HOXA/Hoxa10 gene: A prospective marker of mammalian female fertility? Reprod Biol. 2022 Jun;22(2):100647. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilpasree AS, Kulkarni VB, Shetty P, Bargale A, Goni M, Oli A, et al. Induction of Endometrial HOXA 10 Gene Expression by Vitamin D and its Possible Influence on Reproductive Outcome of PCOS Patients Undergoing Ovulation Induction Procedure. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2022;26(3):252-258. [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S., et al. "Vitamin D levels in follicular fluid and pregnancy outcomes following IVF." Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2019.

- Bischof, P., et al. "Vitamin D and reproductive health: The role of VDR in male and female fertility." Journal of Endocrinology. 2020.

- Bollen, S.E., Bass, J.J., Fujita, S., Wilkinson, D., Hewison, M., Atherton, P.J. (2022). The vitamin D/vitamin D receptor (VDR) axis in muscle atrophy and sarcopenia. Cell Signal, 96, 110355. [CrossRef]

- Blomberg Jensen M, et al. "Vitamin D receptor and vitamin D metabolizing enzymes are expressed in the human male reproductive tract." Human Reproduction. 2010.

- Becker S, Cordes T, Diesing D, Diedrich K, Friedrich M. Expression of 25 hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-hydroxylase in human endometrial tissue. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:771–5.

- Vienonen, A., Miettinen, S., Bläuer, M., Martikainen, P.M., Tomás, E., Heinonen, P.K., et al. (2004). Expression of nuclear receptors and cofactors in human endometrium and myometrium. Journal of the Society for Gynecological Investigation, 11(2), 104–112. [CrossRef]

- Bergadà, L., Pallares, J., Maria Vittoria, A., Cardus, A., Santacana, M., Valls, J., et al. (2014). Role of local bioactivation of vitamin D by CYP27B1 in human endometrial tissue. Fertility and Sterility, 101(4), 1014-1020. [CrossRef]

- Cermisoni GC, Alteri A, Corti L, Rabellotti E, Papaleo E, Viganò P, Sanchez AM. Vitamin D and Endometrium: A Systematic Review of a Neglected Area of Research. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Aug 8;19(8):2320. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cito G, Cocci A, Micelli E, Gabutti A, Russo GI, Coccia ME, Franco G, Serni S, Carini M, Natali A. Vitamin D and Male Fertility: An Updated Review. World J Mens Health. 2020 Apr;38(2):164-177. [CrossRef]

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, de Mouzon J, Sokol R, et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(9):1786-1801. [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F., Binkley, N.C., Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A., Gordon, C.M., Hanley, D.A., Heaney, R.P., et al. (2011). Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 96(7), 1911–1930. [CrossRef]

- Farhangnia P, Noormohammadi M, Delbandi AA. Vitamin D and reproductive disorders: a comprehensive review with a focus on endometriosis. Reprod Health. 2024 May 2;21(1):61. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jukic AMZ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, Wilcox AJ, McConnaughey DR, Steiner AZ. Pre-conception 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and fecundability. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(11):2163–72. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Lin H, Kong S, et al. Physiological and molecular determinants of embryo implantation. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34(5):939-980. [CrossRef]

- Baldini GM, Russo M, Proietti S, Forte G, Baldini D, Trojano G. Supplementation with vitamin D improves the embryo quality in in vitro fertilization (IVF) programs, independently of the patients' basal vitamin D status [published correction appears in Arch Gynecol Obstet.2024 Jun;309(6):2963. doi: 10.1007/s00404-024-07540-z]. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309(6):2881‐2890. [CrossRef]

- Moolhuijsen LME, Visser JA. Anti-Müllerian Hormone and Ovarian Reserve: Update on Assessing Ovarian Function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(11):3361–73. [CrossRef]

- Karami, S., et al. "Seasonal fluctuations of vitamin D and ovarian function: Implications for fertility." Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2021.

- Javed Z, Papageorgiou M, Deshmukh H, Kilpatrick ES, Mann V, Corless L, Abouda G, Rigby AS, Atkin SL, Sathyapalan T. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Hormones, and Liver Markers in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Nutrients. 2019 Jan 17;11(1):188. [CrossRef]

- Calagna G, Catinella V, Polito S, Schiattarella A, De Franciscis P, D’Antonio F, et al. Vitamin D and Male Reproduction: Updated Evidence Based on Literature Review. Nutrients. 2022;14(16):3278.

- Bischof, P., et al. "Vitamin D and reproductive health: The role of VDR in male and female fertility." Journal of Endocrinology. 2020.

- Somigliana, E., Panina-Bordignon, P., Murone, S., Di Lucia, P., Vercellini, P., & Vigano, P. (2007). Vitamin D reserve is higher in women with endometriosis. Human reproduction (Oxford, England), 22(8), 2273–2278. [CrossRef]

- Urbina, A., et al. "Effect of vitamin D supplementation on IVF success rates: A randomized controlled trial." Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2020.

- Meng X, Zhang J, Wan Q, et al. Influence of Vitamin D supplementation on reproductive outcomes of infertile patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2023;21(1):17. Published 2023 Feb 3. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Wu X, Luo X, Shao J, Guo D, Deng B, Wu Z. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on In Vitro Fertilization Outcomes: A Trial Sequential Meta-Analysis of 5 Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Mar 17;13:852428. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moridi I, Chen A, Tal O, Tal R. The Association between Vitamin D and Anti-Müllerian Hormone: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1567. Published 2020 May 28. [CrossRef]

- Moradkhani A, Azami M, Assadi S, Ghaderi M, Azarnezhad A, Moradi Y. Association of vitamin D receptor genetic polymorphisms with the risk of infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024 May 30;24(1):398. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chu J, Gallos I, Tobias A, Tan B, Eapen A, Coomarasamy A. Vitamin D and assisted reproductive treatment outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2018 Jan 1;33(1):65-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv SS, Wang JY, Wang XQ, Wang Y, Xu Y. Serum vitamin D status and in vitro fertilization outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Jun;293(6):1339-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi E, Arab A, Rafiee M, Amani R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between vitamin D and ovarian reserve. Sci Rep. 2021 Aug 6;11(1):16005. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cozzolino M, Busnelli A, Pellegrini L, Riviello E, Vitagliano A. How vitamin D level influences in vitro fertilization outcomes: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2020 Nov;114(5):1014-1025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, K., Thakur, R., Sharma, P., Kamra, P, Khetarpal, P. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) and its association with VDR gene variants Cdx2 (rs11568820) and ApaI (rs7975232): Systematic review, meta-analysis and in silico analysis,Human Gene,Volume 40,2024,201293, ISSN 2773-0441, https://. [CrossRef]

- Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2841-2855. [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 194: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Sep;136(3):638. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004069. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):e157-e171. [CrossRef]

- Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(3):364-379. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield RL, Ehrmann DA. The Pathogenesis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): The Hypothesis of PCOS as Functional Ovarian Hyperandrogenism Revisited. Endocr Rev. 2016;37(5):467-520. [CrossRef]

- Kuyucu Y, Çelik LS, Kendirlinan Ö, Tap Ö, Mete UÖ. Investigation of the uterine structural changes in the experimental model with polycystic ovary syndrome and effects of vitamin D treatment: An ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Reproductive Biology. 2018 Mar;18(1):53-59. DOI: 10.1016/j.repbio.2018.01.002. [PubMed]

- Pal L, Zhang H, Williams J, Santoro NF, Diamond MP, Schlaff WD, Coutifaris C, Carson SA, Steinkampf MP, Carr BR, McGovern PG, Cataldo NA, Gosman GG, Nestler JE, Myers E, Legro RS; Reproductive Medicine Network. Vitamin D Status Relates to Reproductive Outcome in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Secondary Analysis of a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Aug;101(8):3027-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thomson RL, Spedding S, Buckley JD. Vitamin D in the aetiology and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77(3):343-350. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostis P, Karras S, Goulis DG. Vitamin D in human reproduction: a narrative review. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(3):225-235. [CrossRef]

- Morgante G, Darino I, Spanò A, Luisi S, Luddi A, Piomboni P, Governini L, De Leo V. PCOS Physiopathology and Vitamin D Deficiency: Biological Insights and Perspectives for Treatment. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 2;11(15):4509. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maktabi M, Chamani M, Asemi Z. The Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Metabolic Status of Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Horm Metab Res. 2017;49(7):493-498. [CrossRef]

- Trummer C, Schwetz V, Kollmann M, et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on metabolic and endocrine parameters in PCOS: a randomized-controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58(5):2019-2028. [CrossRef]

- Davis EM, Peck JD, Hansen KR, Neas BR, Craig LB. Associations between vitamin D levels and polycystic ovary syndrome phenotypes. Minerva Endocrinol. 2019;44(2):176-184. [CrossRef]

- Lerchbaum E, Theiler-Schwetz V, Kollmann M, et al. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Surrogate Markers of Fertility in PCOS Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):547. Published 2021 Feb 7. [CrossRef]

- 84. TABLA.

- Trummer C, Schwetz V, Kollmann M, Wölfler M, Münzker J, Pieber TR, Pilz S, Heijboer AC, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Lerchbaum E. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on metabolic and endocrine parameters in PCOS: a randomized-controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2019 Aug;58(5):2019-2028. [CrossRef]

- Ostadmohammadi V, Jamilian M, Bahmani F, Asemi Z. Vitamin D and probiotic co-supplementation affects mental health, hormonal, inflammatory and oxidative stress parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Ovarian Res. 2019 Jan 21;12(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Lerchbaum E, Theiler-Schwetz V, Kollmann M, Wölfler M, Pilz S, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Trummer C. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Surrogate Markers of Fertility in PCOS Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2021 Feb 7;13(2):547. [CrossRef]

- Dastorani M, Aghadavod E, Mirhosseini N, Foroozanfard F, Zadeh Modarres S, Amiri Siavashani M, Asemi Z. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on metabolic profiles and gene expression of insulin and lipid metabolism in infertile polycystic ovary syndrome candidates for in vitro fertilization. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018 Oct 4;16(1):94. [CrossRef]

- Javed Z, Papageorgiou M, Deshmukh H, Kilpatrick ES, Mann V, Corless L, Abouda G, Rigby AS, Atkin SL, Sathyapalan T. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Hormones, and Liver Markers in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Nutrients. 2019 Jan 17;11(1):188. [CrossRef]

- Azhar A, Alam SM, Rehman R. Vitamin D and Lipid Profiles in Infertile PCOS and Non-PCOS Females. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2024 Jul;34(7):767-770. [CrossRef]

- Irani M, Seifer DB, Grazi RV, Julka N, Bhatt D, Kalgi B, Irani S, Tal O, Lambert-Messerlian G, Tal R. Vitamin D Supplementation Decreases TGF-β1 Bioavailability in PCOS: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Nov;100(11):4307-14. [CrossRef]

- Wen X, Wang L, Li F, Yu X. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on metabolic parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Ovarian Res. 2024 Jul 16;17(1):147. [CrossRef]

- Krul-Poel YHM, Koenders PP, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Ten Boekel E, Wee MMT, Louwers Y, Lips P, Laven JSE, Simsek S. Vitamin D and metabolic disturbances in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018 Dec 4;13(12):e0204748. [CrossRef]

- Edi R, Cheng T. Endometriosis: Evaluation and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2022 Oct;106(4):397-404. [PubMed]

- Cousins FL, McKinnon BD, Mortlock S, Fitzgerald HC, Zhang C, Montgomery GW, Gargett CE. New concepts on the etiology of endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023 Apr;49(4):1090-1105. [CrossRef]

- Cano-Herrera, G.; Salmun Nehmad, S.; Ruiz de Chávez Gascón, J.; Méndez Vionet, A.; van Tienhoven, X.A.; Osorio Martínez, M.F.; Muleiro Alvarez, M.; Vasco Rivero, M.X.; López Torres, M.F.; Barroso Valverde, M.J.; et al. Endometriosis: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Nutritional Aspects, and Its Repercussions on the Quality of Life of Patients. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1476. [CrossRef]

- Giudice LC, Oskotsky TT, Falako S, Opoku-Anane J, Sirota M. Endometriosis in the era of precision medicine and impact on sexual and reproductive health across the lifespan and in diverse populations. FASEB J. 2023 Sep;37(9):e23130. [CrossRef]

- Shafrir, A.L.; Farland, L.V.; Shah, D.K.; Harris, H.R.; Kvaskoff, M.; Zondervan, K.; Missmer, S.A. Risk for and consequences of endometriosis: A critical epidemiologic review. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 51, 1–15.

- Smolarz, B.; Szyłło, K.; Romanowicz, H. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis, Treatment and Genetics (Review of Literature). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10554. [CrossRef]

- Ocampo Hernández Dulce María, Gallardo Valencia Luis Ernesto, Guzmán-Valdivia Gómez Gilberto. Evaluación de la calidad de vida en pacientes con endometriosis mediante una escala original. Acta méd. Grupo Ángeles. 2023 Dez [citado 2025 Jan 29] ; 21( 4 ): 349-355. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1870-72032023000400349&lng=pt. Epub 21-Out-2024. [CrossRef]

- Nodler JL, DiVasta AD, Vitonis AF, Karevicius S, Malsch M, Sarda V, Fadayomi A, Harris HR, Missmer SA. Supplementation with vitamin D or ω-3 fatty acids in adolescent girls and young women with endometriosis (SAGE): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020 Jul 1;112(1):229-236. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kalaitzopoulos DR, Samartzis N, Daniilidis A, Leeners B, Makieva S, Nirgianakis K, Dedes I, Metzler JM, Imesch P, Lempesis IG. Effects of vitamin D supplementation in endometriosis: a systematic review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2022 Dec 28;20(1):176. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delbandi AA, Torab M, Abdollahi E, Khodaverdi S, Rokhgireh S, Moradi Z, Heidari S, Mohammadi T. Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for endometriosis in Iranian women. J Reprod Immunol. 2021 Feb;143:103266. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings BS, Hewison M. Vitamin D and Endometriosis: Is There a Mechanistic Link? Cell Biochem Funct. 2025 Jan;43(1):e70037. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng SH, Chen XX, Chen Y, Wu ZC, Chen XQ, Li XL. Antioxidant vitamins supplementation reduce endometriosis related pelvic pain in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2023 Aug 29;21(1):79. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hartwell, D., Rødbro, P., Jensen, S. B., Thomsen, K., & Christiansen, C. (1990). Vitamin D metabolites--relation to age, menopause and endometriosis. Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation, 50(2), 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Somigliana, E., Panina-Bordignon, P., Murone, S., Di Lucia, P., Vercellini, P., & Vigano, P. (2007). Vitamin D reserve is higher in women with endometriosis. Human reproduction (Oxford, England), 22(8), 2273–2278. [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, M., Koga, K., Izumi, G., Sue, F., Makabe, T., Taguchi, A., Nagai, M., Urata, Y., Takamura, M., Harada, M., Hirata, T., Hirota, Y., Wada-Hiraike, O., Fujii, T., & Osuga, Y. (2016). Effects of 1,25-Dihydroxy Vitamin D3 on Endometriosis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 101(6), 2371–2379. [CrossRef]

- Bellerba, F., Muzio, V., Gnagnarella, P., Facciotti, F., Chiocca, S., Bossi, P., Cortinovis, D., Chiaradonna, F., Serrano, D., Raimondi, S., Zerbato, B., Palorini, R., Canova, S., Gaeta, A., & Gandini, S. (2021). The Association between Vitamin D and Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review of Human Studies. Nutrients, 13(10), 3378. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, B. S., & Hewison, M. (2025). Vitamin D and Endometriosis: Is There a Mechanistic Link?. Cell biochemistry and function, 43(1), e70037. [CrossRef]

- Shrateh, O. N., Siam, H. A., Ashhab, Y. S., Sweity, R. R., & Naasan, M. (2024). The impact of vitamin D treatment on pregnancy rate among endometriosis patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Annals Of Medicine And Surgery, 86(7), 4098-4111. [CrossRef]

- Mun MJ, Kim TH, Hwang JY, Jang WC. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and the risk for female reproductive cancers: A meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2015 1 Jun;81(2):256-265. DOI: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.03.010. [PubMed]

- Xie, B., Liao, M., Huang, Y., Hang, F., Ma, N., Hu, Q., Wang, J., Jin, Y., & Qin, A. (2024). Association between vitamin D and endometriosis among American women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PloS one, 19(1), e0296190. [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzopoulos, D. R., Lempesis, I. G., Athanasaki, F., Schizas, D., Samartzis, E. P., Kolibianakis, E. M., & Goulis, D. G. (2020). Association between vitamin D and endometriosis: a systematic review. Hormones (Athens, Greece), 19(2), 109–121. [CrossRef]

- Espinola MSB, Bilotta G, Aragona C. Positive effect of a new supplementation of vitamin D3 with myo-inositol, folic acid and melatonin on IVF outcomes: a prospective randomized and controlled pilot study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020;37:1–4. [CrossRef]

| STUDY | COUNTRY | VIT D (n) | TYPE OF STUDY | CONCLUSIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou X et al, 2022. [63] | Switzerland | n=5 | Meta-Analysis. | VD may positively influence early pregnancy outcomes in women undergoing IVF, particularly for those with VD deficiency. |

| Moridi I et al, 2020. [64] | United States | n=5 | Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. | Vitamin D is a safe, affordable supplement with growing evidence supporting its benefits in improving pregnancy rates, live births in assisted reproduction, reducing pregnancy loss, and minimizing pregnancy complications. |

| Moradkhani et al, 2024. [65] | Iran | n=4 | Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. | Taql polymorphisms of the VDR gene are associated with susceptibility to infertility in women. But the protective polymorphisms for infertility are Fokl and Apal in women. |

| Chu et al, 2018. [66] | United Kingdom | n=11 | Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. | Women with sufficient levels of VD are more likely to achieve positive results in assisted reproductive treatments compared to women with VD deficiency. |

| Lv SS et al, 2016. [67] | China | n=5 | Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. | Women with adequate levels of VD are more likely to give birth to a live child after undergoing in vitro fertilization. |

| Karimi E et al, 2021. [68] | Iran | n=38 | Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. | No direct relationship was found between overall VD levels with ovarian reserve in women. However, further studies are required to understand the fundamental role of VD in ovarian reserve. |

| Cozzolino et al, 2020. [69] | Spain | n=14 | Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. | VD levels do not significantly affect IVF outcomes in terms of the number of pregnancies.As well as the number of live births. |

| Meng et al, 2023. | China | RCT n=9 | Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. | VD supplementation increases the probability of pregnancy in infertile women, mainly in patients with low VD levels, but further clinical studies are recommended. |

| STUDY | COUNTRY | VIT D (N) | TYPE OF STUDY | CONCLUSIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trummer et al, 2018. [81] | Austria. | N = 123 | Randomized controlled trial | VD supplementation resulted in a reduction in plasma glucose after 60 minutes during the OGTT. Aside from this, it had no significant effect on metabolic and endocrine parameters in PCOS. |

| Ostadmohammadi et al, 2019. [86] | Iran. | N = 60 | Randomize, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Supplementation of VD and probiotics, when compared to placebo, significantly improved depression, anxiety, stress, general health, and overall well-being in women with PCOS. It also contributed to a decrease in total testosterone, hirsutism, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Furthermore, there was a notable increase in total antioxidant capacity and glutathione levels. |

| Lerchbaum et al, 2021. [83] | Austria. | N = 180 | Double-blind randomized controlled trial | VD treatment in women with PCOS significantly affected FSH and the LH/FSH ratio after 24 weeks, but did not impact AMH levels. No significant effects were observed in non-PCOS women. |

| Dastorani et al, 2018. [88] | Iran. | N = 40 | Randomize, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial | VD supplementation significantly reduced serum AMH, insulin levels, and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), while increasing insulin sensitivity (QUICKI) compared to the placebo. Additionally, it led to a significant decrease in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels. |

| Javed et al, 2019. [57] | United Kingdom. | N = 44 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | This study shows that VD supplementation has beneficial effects on liver injury and fibrosis markers (ALT levels), along with modest improvements in insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in overweight and obese, VD-deficient women with PCOS. However, no significant changes were seen in other cardiovascular risk factors or hormones. |

| Azhar et al, 2024. [90] | Pakistan. | N = 180 | Comparative descriptive study. | Women with PCOS had lower VD levels. Both women with PCOS and VD deficiency exhibited lower HDL levels and higher total cholesterol, LDL, VLDL, and triglyceride levels compared to women without PCOS or those with sufficient or insufficient VD levels. |

| Irani et al, 2015. [91] | United States. | N = 93 | Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. | VD supplementation in women with PCOS increased VD levels and led to shorter menstrual cycles, reduced hirsutism (Ferriman-Gallwey score), lower triglycerides, and a decreased TGF-β1 to sENG ratio, highlighting VD's potential role in improving lipid metabolism and inflammation in PCOS. |

| Wen et al, 2024. [92] | China | N = 60 | Randomized controlled trial. | VD supplementation increased serum 25(OH)D levels. After 12 weeks, women in the VD group had lower BMI, WHR, insulin, HOMA-IR, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL-C compared to the control group in women with obesity or insulin resistance. |

| Krul et al, 2018. [93] | Netherlands | N = 1088 | Cross-sectional comparison study. | VD deficiency in PCOS may contribute to metabolic issues, especially insulin resistance and lipid abnormalities. Women with PCOS had lower VD levels, which were associated with higher insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and poorer lipid profiles, including reduced HDL-cholesterol and apolipoprotein A1. |

| STUDY | COUNTRY | VIT D (N) | TYPE OF STUDY | CONCLUSIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartwell D et al., (1990) [106]. | Denmark | N = 345 | Observational Cross-Sectional Study | This study analyzed vitamin D metabolite levels in women with and without endometriosis, across different age groups and menopausal status. It found that vitamin D levels fluctuate with age and menopause but did not establish a clear link between vitamin D and endometriosis severity. |

| Somigliana E et al (2007) [60] | England | N= 140 | Observational Case-Control Study | This study measured vitamin D reserves in women with endometriosis and found that, paradoxically, women with the condition had higher levels of vitamin D compared to controls. The findings suggest that increased vitamin D levels may be a compensatory response rather than a protective factor. |

| Miyashita M et al (2016) [108] | Japan | N= 35 | Experimental In Vitro Study | This study investigated the effects of the active form of vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3) on endometrial cells. It found that vitamin D3 inhibited the proliferation of endometrial stromal cells and reduced inflammatory markers, suggesting a potential therapeutic role for vitamin D in managing endometriosis. |

| Bellerba et al (2021) [109] | Italy | N= 25 analysis reviewed | Systematic review | This systematic review the authors explore the link between vitamin D and gut microbiota, indicating that vitamin D significantly influences the gut's microbial makeup and diversity. They found that higher vitamin D levels correlate with a richer microbiota, potentially increasing beneficial bacteria while decreasing harmful ones. The review points out that vitamin D deficiency may contribute to dysbiosis,.However, initial findings suggest that vitamin D may impact the immune system and cellular processes related to endometriosis. |

| Jennings et. al., (2025) [110] | USA | 12 studies reviewed | Systematic review | This study explores potential biological mechanisms linking vitamin D deficiency to endometriosis. It highlights the role of vitamin D in regulating inflammatory and immune responses, which may influence lesion development. |

| Zheng et al (2023) [105] | China | 13 RCTs involving 589 patients | Randomized Controlled Trial | A randomized controlled trial showed that supplementation with antioxidant vitamins, including vitamin D, significantly reduced dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. It also improved the overall quality of life. |

| Shrateh et al (2024) [111] | Israel | N=3 | Systematic Review and Meta analysis | The beneficial effects of VD supplementation on endometriosis-related symptoms may indirectly support better pregnancy outcomes and improved fertility. |

| Mun et al (2015) [112] | Ireland | N= 123 | Meta analysis | This meta-analysis found that certain vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of endometriosis, suggesting a genetic component to the disease's susceptibility. |

| Farhangnia et al (2024) [51] | Iran | N=180 | Comprehensive Review | This review examined the role of vitamin D in normal reproductive function and disorders, with a focus on endometriosis. Cellular and molecular studies suggest that vitamin D can inhibit key processes involved in endometriosis, such as cell proliferation, invasion,angiogenesis, and inflammation. Animal studies support these findings, showing that vitamin D treatment reduces endometriotic lesions in rats. However, human studies have yielded inconsistent results regarding the relationship between vitamin D levels and the risk or severity of endometriosis. |

| Kalaitzopoulos et al (2022) [102] | Greece | N = 12 | Systematic review | This review amalgamates results of available studies where supplementation of Vitamin D has a role as a treatment in endometriosis. |

| Xie. et al, 2024 [113] | Germany | N = 257 | Observational Cross-Sectional Study | A cross-sectional study found that higher serum 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with a decreased incidence of endometriosis women with endometriosis. These results lend credence to the possible advantages of maintaining sufficient vitamin D levels to prevent endometriosis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).