Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Given the significant impact of air pollution on global health, continuous and precise monitoring of air quality in all populated environments is crucial. Unfortunately, even in the most developed economies, current air quality monitoring networks are largely inadequate. The high cost of monitoring stations has been identified as a key barrier to widespread coverage, making cost-effective air quality monitoring devices a potential game changer. However, the accuracy of measurements obtained from low-cost sensors is affected by many factors, including gas cross-sensitivity, environmental conditions, and production inconsistencies. Fortunately, machine learning models can capture complex interdependent relationships in sensor responses, and thus can enhance their readings and sensor accuracy. After gathering measurements from cost-effective air pollution monitoring devices placed alongside a reference station, the data were used to train such models. Assessment of their performance showed that models tailored to individual sensor units greatly improved measurement accuracy, boosting their correlation with reference-grade instruments by up to 10\%. Nonetheless, the research also revealed that inconsistencies in the performance of similar sensor units can prevent the creation of a unified correction model for a given sensor type.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Advantages of Cost-Effective Air Pollution Monitoring Devices

2.2. Current Technical Limitations

- Electrochemical (EC) sensors measure the current produced by electrochemical reactions with the target gas [55].

- Non-dispersive infrared (NDIR) sensors track reductions in infrared radiation when the gas passes through an active filter [56].

- Metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) sensors rely on gas-solid interactions that induce an electronic charge on the metal oxide surface.

- Photo-ionisation detection (PID) sensors employ ultraviolet light to ionise target molecules, converts the resulting ions into digital reading, and thus quantifies the chemical content [57].

2.3. Measurement Corrections

3. Dataset: Co-located Cost-Effective Device and Reference Station Measurements

3.1. Data Collection

| Sensor Type | Weybourne Atmospheric Lab. | Cost-Effective Solution | |

| CO | Model | Ecotech Spectronus | Honeywell AQ7CO |

| Technology | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer | Electrochemistry | |

| Precision | 1 PPB | unknown | |

| Unit cost | > $100,000 (it measures both CO and CO2) | < $150 | |

| O3 | Model | Thermo 49i Ozone Analyzer | Honeywell AQ7OZ |

| Technology | UV Absorption | Electrochemistry | |

| Precision | 1 PPB | unknown | |

| Unit cost | > $3,000 | < $150 | |

| CO2 | Model | Ecotech Spectronus | Sensirion SCD30 |

| Technology | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer | Non Dispersive Infrared | |

| Precision | 100 PPB (0.1 PPM) | 30,000 PPB (30 PPM) | |

| Unit cost | > $100,000 (it measures both CO and CO2) | < $50 | |

| Others | Temperature (°C), relative humidity (%) and pressure (hPa) | ||

| Sensor | Unit | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev. | Missing Values |

| Temperature WAO | °C | 7.56 | 28.07 | 14.93 | 3.20 | 2 |

| Temperature 5158 | °C | 13.85 | 37.74 | 22.26 | 3.97 | 0 |

| Temperature 5178 | °C | 12.99 | 38.07 | 21.69 | 4.08 | 0 |

| Relative Humidity WAO | % | 32.31 | 100.00 | 77.29 | 13.47 | 2 |

| Relative Humidity 5158 | % | 27.22 | 68.41 | 52.03 | 9.04 | 0 |

| Relative Humidity 5178 | % | 26.21 | 70.21 | 54.03 | 9.77 | 0 |

| Pressure WAO | hPa | 990.52 | 1023.53 | 1008.82 | 5.99 | 2 |

| Pressure 5158 | kPa | 99.22 | 102.53 | 101.06 | 0.60 | 0 |

| Pressure 5178 | kPa | 99.23 | 102.54 | 101.07 | 0.60 | 0 |

| CO WAO | ppb | 84.25 | 294.13 | 110.80 | 15.76 | 318 |

| CO 5158 | µV | 1380450 | 2382109 | 2232868 | 66708.54 | 0 |

| CO 5178 | µV | 1177112 | 2280425 | 2129110 | 85833.71 | 0 |

| O3 WAO | ppb | 7.72 | 65.69 | 28.83 | 8.34 | 395 |

| O3 5158 | µV | 2197081 | 2552181 | 2343918 | 49237.40 | 0 |

| O3 5178 | µV | 2164612 | 2589412 | 2341934 | 52920.40 | 0 |

| CO2 WAO | ppm | 406.88 | 468.03 | 423.47 | 9.22 | 330 |

| CO2 5158 | ppm | 94.58 | 180.73 | 121.17 | 11.52 | 0 |

| CO2 5178 | ppm | 217.99 | 329.56 | 256.31 | 15.89 | 0 |

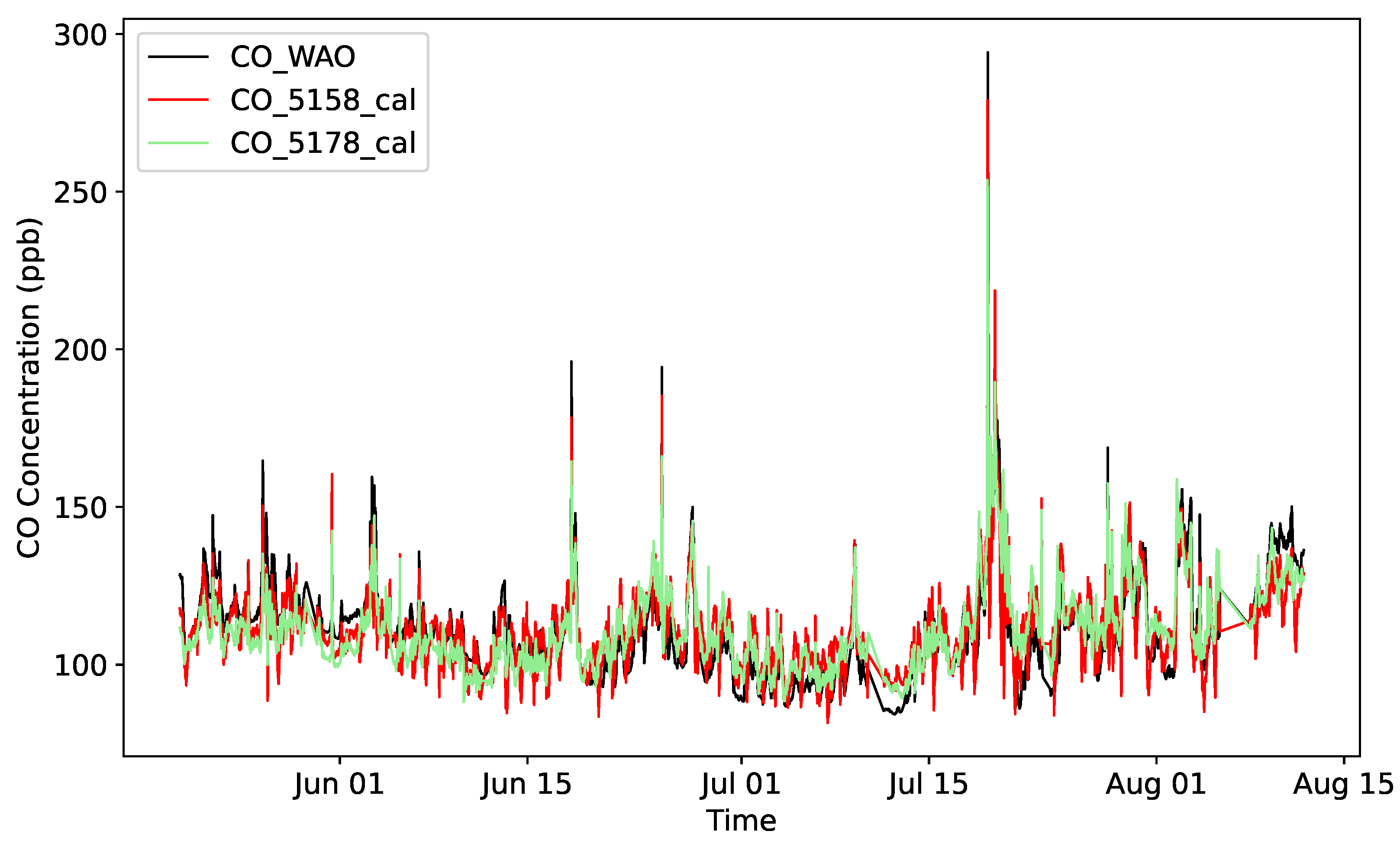

3.2. Sensor Calibration

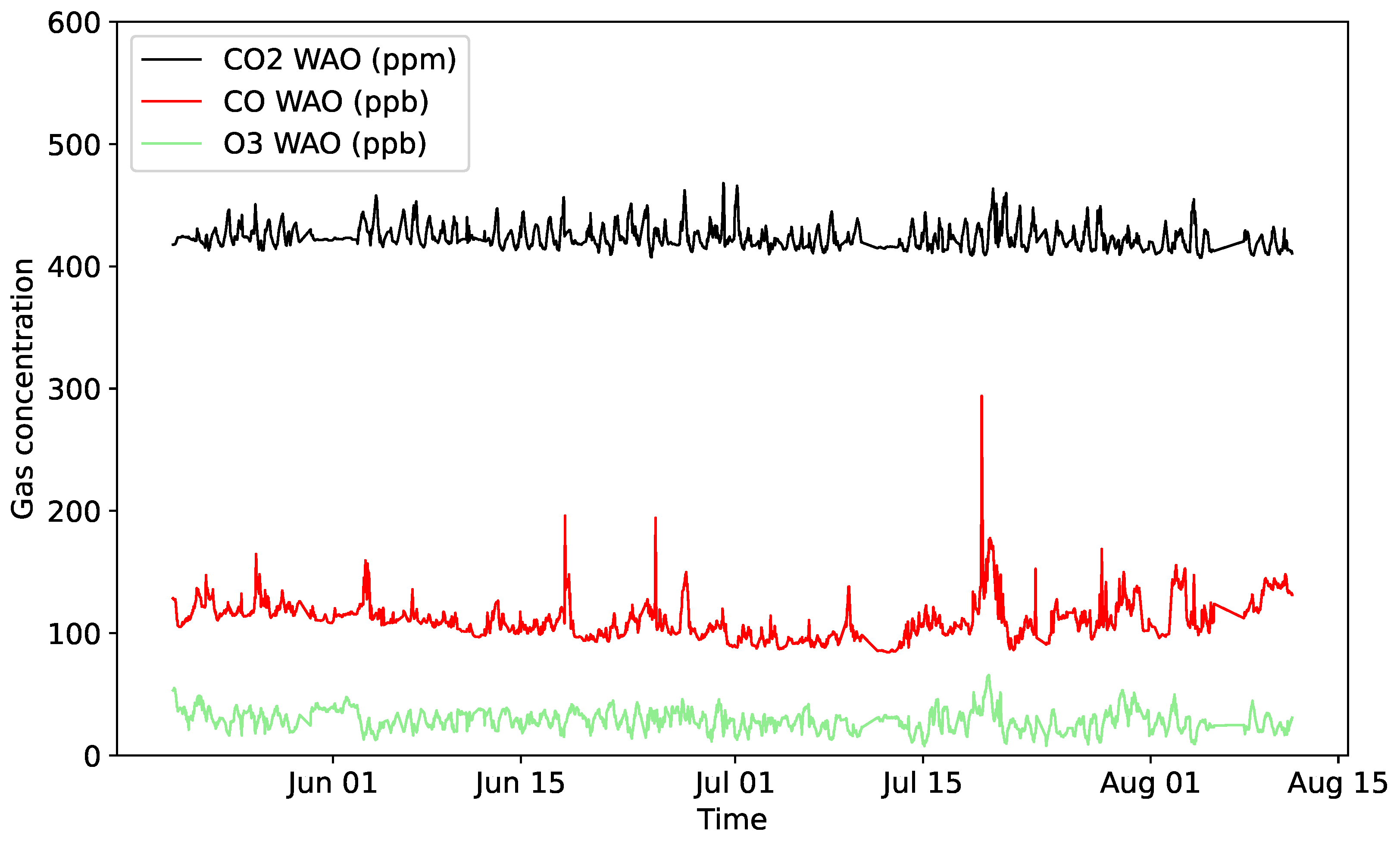

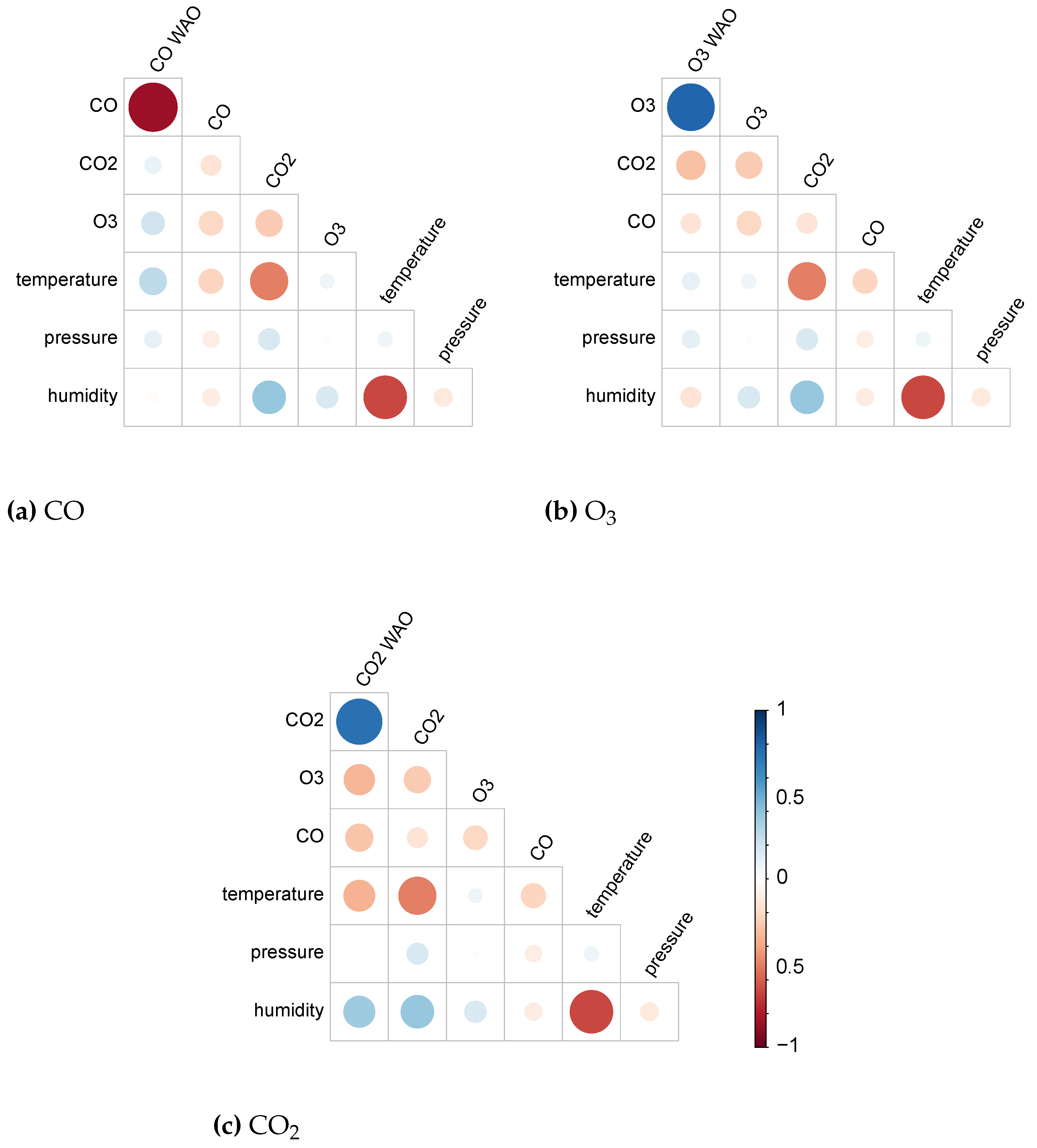

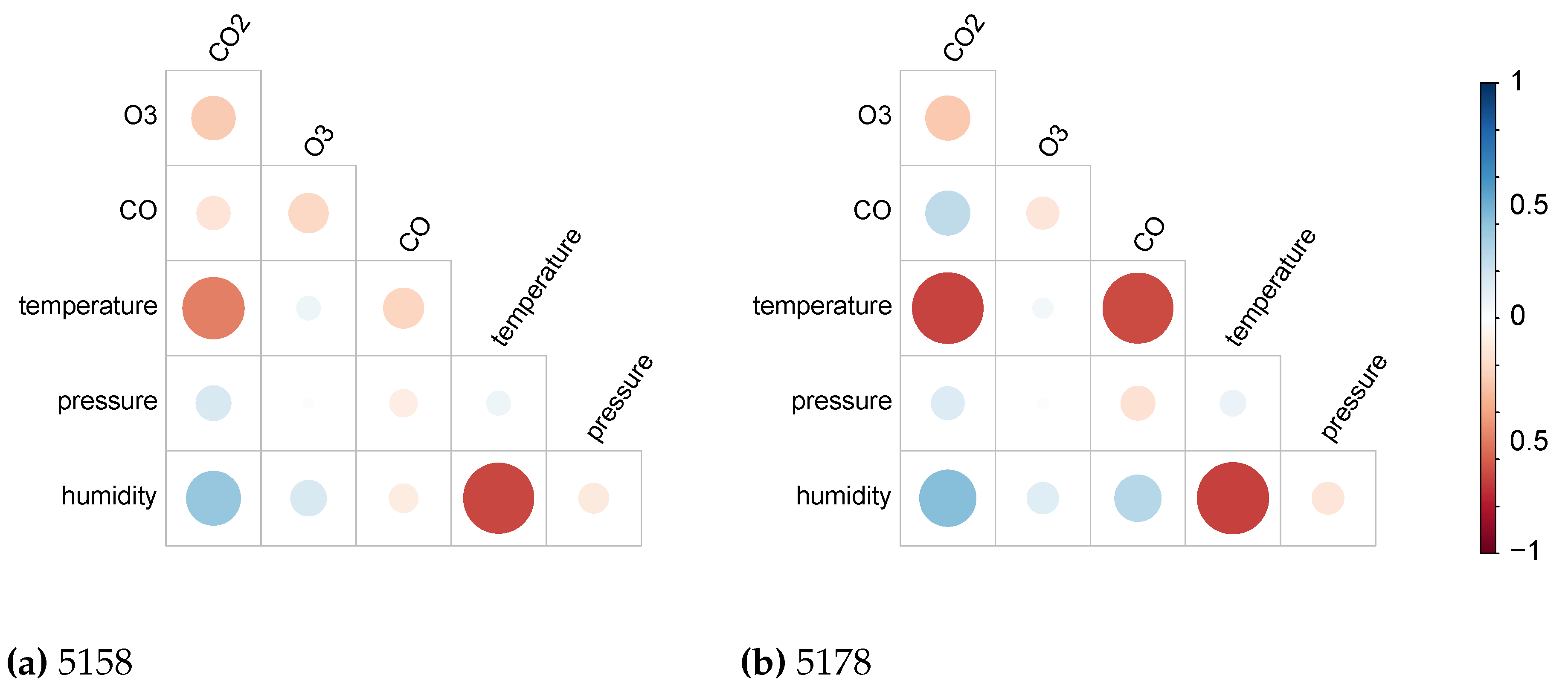

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Methodology to Enhance Measurement Accuracy

4.1. Model Choice

- Y: the reference observation;

- : the intercept;

- : the coefficients of the model for each feature;

- : the observation for the feature k, ;

- : the residual term.

4.2. Feature Selection

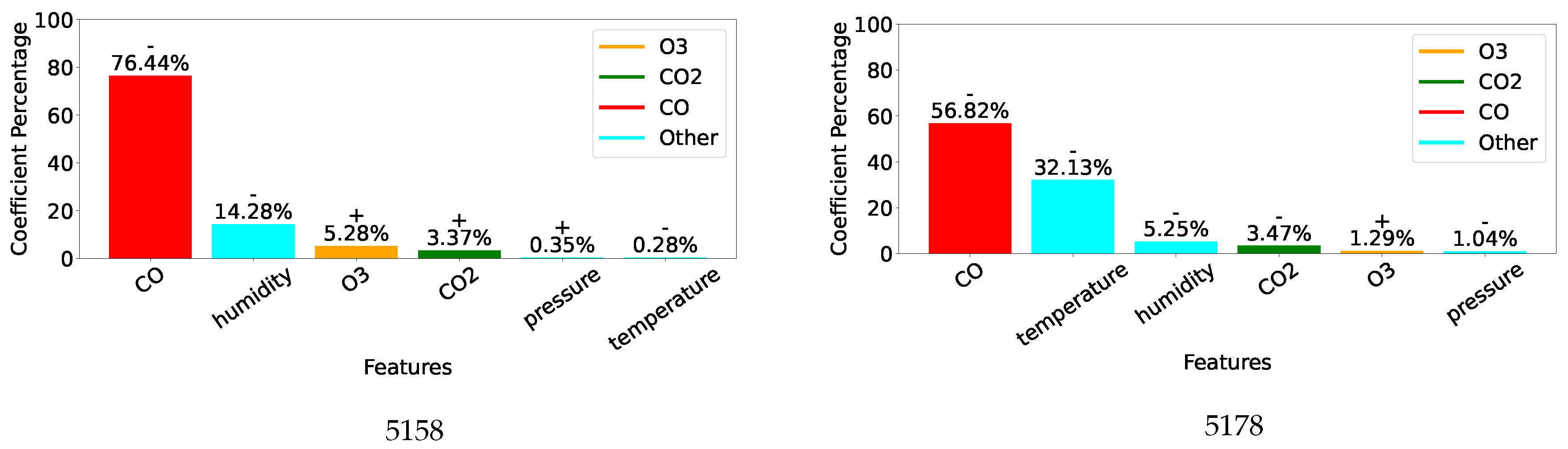

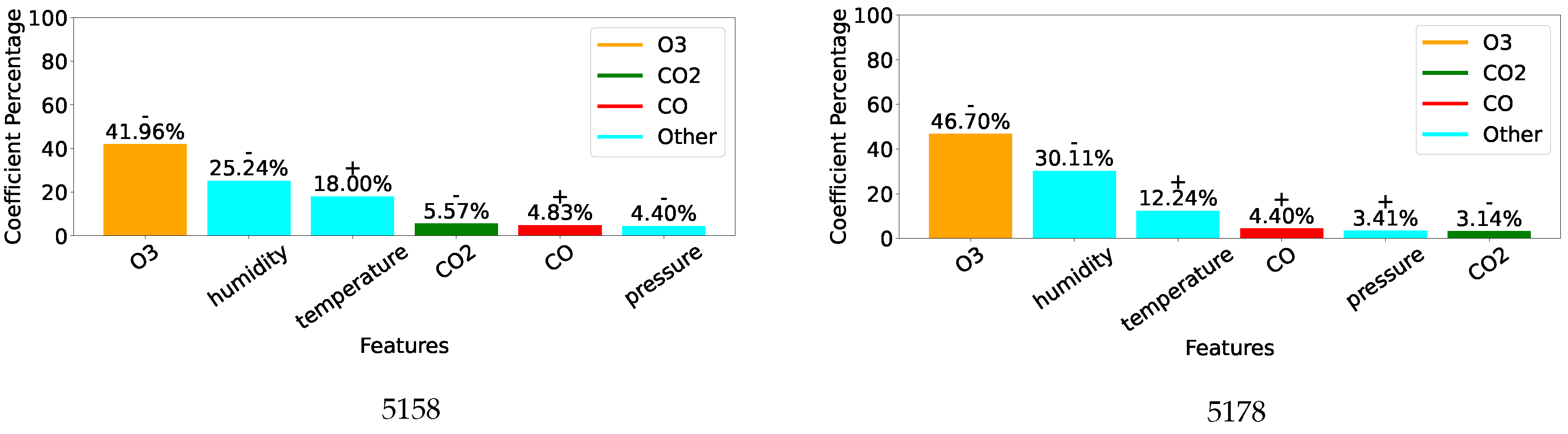

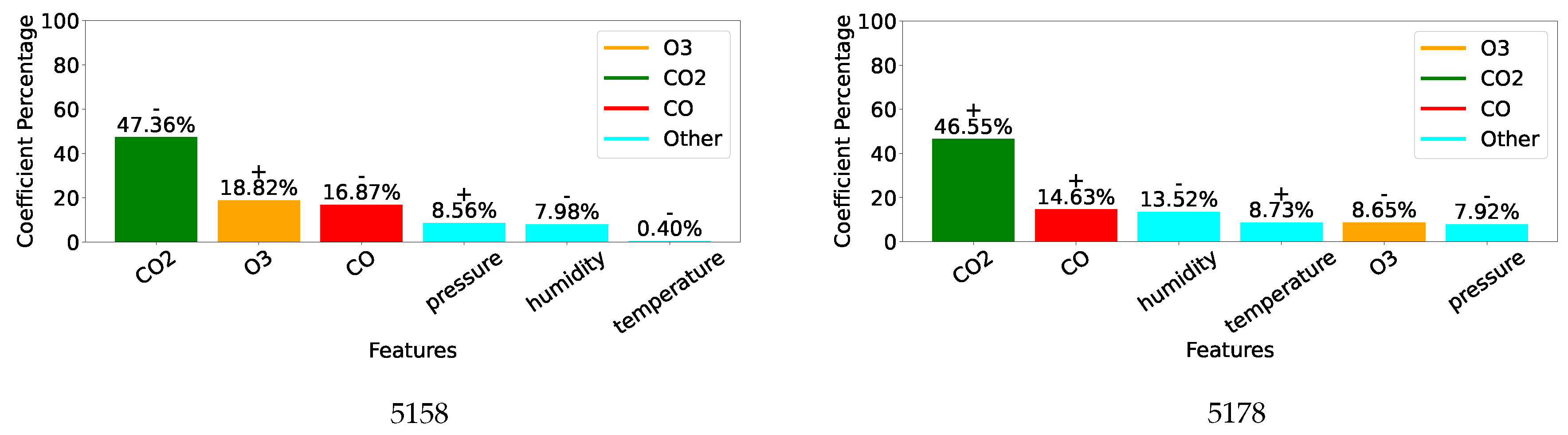

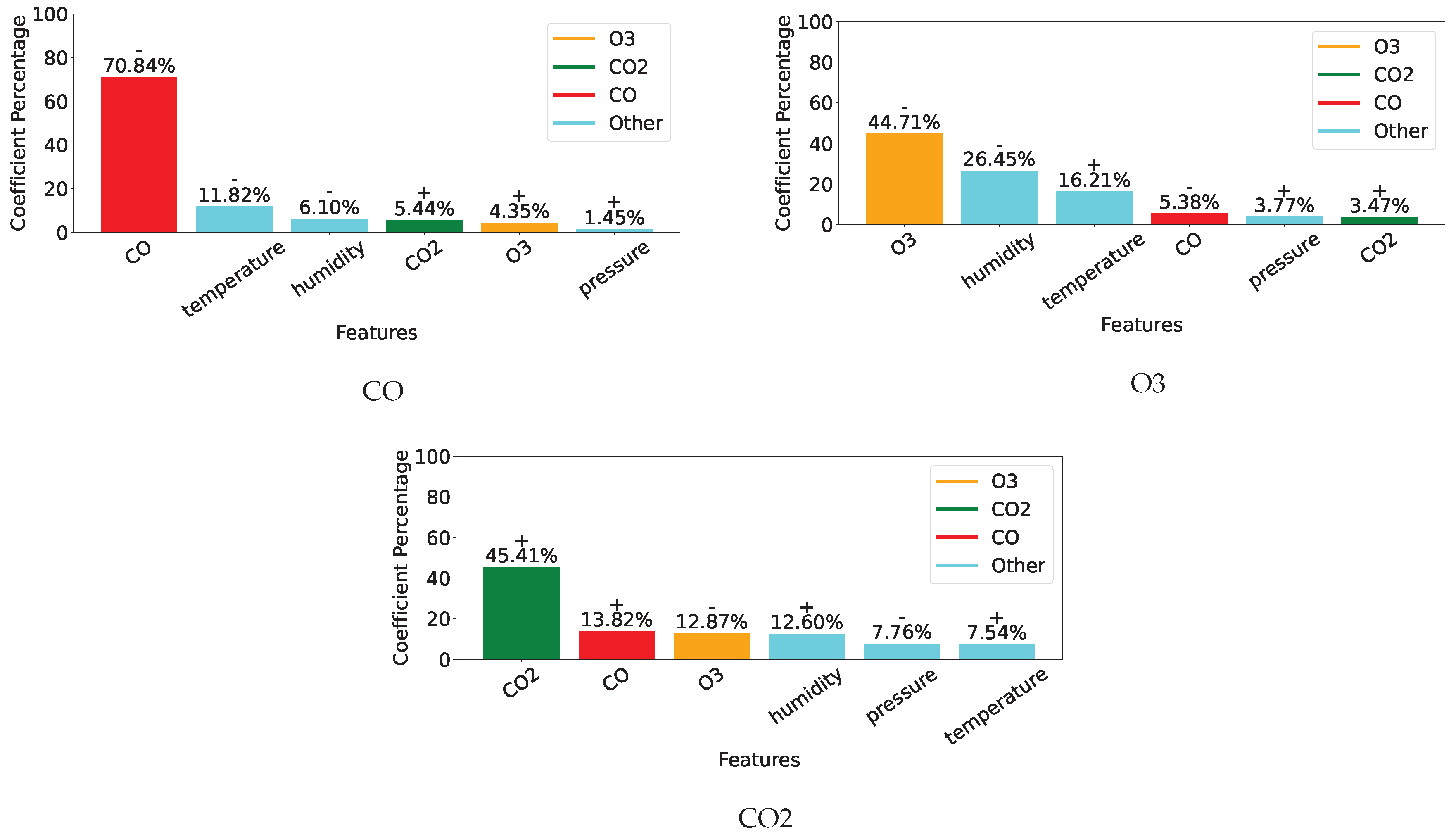

| 5158 | 5178 | Combo (5158+5178) | |||||||

| CO | O3 | CO2 | CO | O3 | CO2 | CO | O3 | CO2 | |

| CO | √ | √ | √ | √ | . | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| O3 | . | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| CO2 | . | √ | √ | . | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Temperature | . | √ | . | √ | . | . | √ | √ | √ |

| Humidity | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Pressure | . | √ | √ | . | . | √ | √ | √ | √ |

- Z: the standardised value of the feature;

- X: the initial value of the feature;

- : the mean value of the feature;

- (X): the standard deviation of the feature.

5. Results

5.1. Models for individual sensors

| Correlation | MPE | MAE | STD | Min | Max | ||

| CO 58 (ppb) | MLR (all features) | 0.84 | 4.91 % | 7.03 | 4.83 | 0.03 | 29.44 |

| MLR (best features) | 0.84 | 4.66 % | 6.86 | 4.76 | 0.05 | 30.10 | |

| SVR (best features) | 0.83 | 4.70 % | 6.13 | 4.02 | 0.06 | 24.65 | |

| Calibration | 0.82 | 4.51 % | 6.93 | 4.96 | 0.04 | 29.90 | |

| CO 78 (ppb) | MLR (all features) | 0.90 | 2.95 % | 4.80 | 3.76 | 0.02 | 29.76 |

| MLR (best features) | 0.90 | 2.97 % | 4.78 | 3.68 | 0.03 | 28.84 | |

| SVR (best features) | 0.91 | 3.07 % | 4.17 | 2.89 | 0.04 | 20.43 | |

| Calibration | 0.84 | 5.71 % | 7.66 | 4.80 | 0.06 | 26.87 | |

| O3 58 (ppb) | MLR (all features) | 0.89 | 8.14 % | 3.24 | 2.40 | 0.02 | 12.81 |

| MLR (best features) | 0.89 | 8.14 % | 3.24 | 2.40 | 0.02 | 12.81 | |

| SVR (best features) | 0.91 | 4.45 % | 2.51 | 1.86 | 0.01 | 9.79 | |

| Calibration | 0.80 | 11.81 % | 4.18 | 3.05 | 0.01 | 14.56 | |

| O3 78 (ppb) | MLR (all features) | 0.82 | 13.44 % | 4.93 | 3.15 | 0.09 | 18.83 |

| MLR (best features) | 0.82 | 13.02 % | 4.75 | 3.07 | 0.06 | 18.40 | |

| SVR (best features) | 0.85 | 8.40 % | 3.54 | 2.48 | 0.03 | 14.14 | |

| Calibration | 0.72 | 15.10 % | 5.19 | 3.70 | 0.03 | 18.57 | |

| CO2 58 (ppm) | MLR (all features) | 0.80 | 0.33 % | 4.18 | 3.57 | 0.02 | 18.85 |

| MLR (best features) | 0.81 | 0.32 % | 4.14 | 3.56 | 0.02 | 18.88 | |

| SVR (best features) | 0.82 | 0.38 % | 3.93 | 3.24 | 0.02 | 16.50 | |

| Calibration | 0.74 | 0.33 % | 4.70 | 3.78 | 0.01 | 20.35 | |

| CO2 78 (ppm) | MLR (all features) | 0.85 | 0.42 % | 3.84 | 3.39 | 0.03 | 19.35 |

| MLR (best features) | 0.86 | 0.42 % | 3.82 | 3.40 | 0.02 | 19.11 | |

| SVR (best features) | 0.87 | 0.41 % | 3.56 | 3.13 | 0.03 | 16.05 | |

| Calibration | 0.79 | 0.51 % | 4.60 | 3.72 | 0.02 | 19.38 |

5.2. Models for Combined Sensors

| Correlation | MPE | MAE | STD | Min | Max | ||

| CO (ppb) | MLR (all features) | 0.81 | 4.27 % | 6.83 | 4.99 | 0.03 | 35.85 |

| SVR (all features) | 0.81 | 4.48 % | 7.07 | 5.34 | 0.03 | 43.21 | |

| Calibration | 0.82 | 4.57 % | 6.85 | 4.88 | 0.02 | 31.43 | |

| O3 (ppb) | MLR (all features) | 0.85 | 10.79 % | 4.05 | 2.89 | 0.01 | 18.74 |

| SVR (all features) | 0.85 | 9.67 % | 3.89 | 2.85 | 0.01 | 18.01 | |

| Calibration | 0.76 | 12.33 % | 4.51 | 3.35 | 0.01 | 18.39 | |

| CO2 (ppm) | MLR (all features) | 0.79 | 0.29 % | 4.19 | 3.62 | 0.01 | 20.38 |

| SVR (all features) | 0.80 | 0.32 % | 4.01 | 3.60 | 0.01 | 20.52 | |

| Calibration | 0.75 | 0.32 % | 4.56 | 3.73 | 0.01 | 20.85 |

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burnett, R. et al. (2018) ‘Global estimates of mortality associated with long-term exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(38), pp. 9592–9597. [CrossRef]

- 2022. Ambient (outdoor) air pollution, World Health Organization [Accessed on 31 January 2025].

- Forouzanfar, M.H. et al. (2016) ‘Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015’, The Lancet, 388(10053), pp. 1659–1724. [CrossRef]

- Morawska, L. et al. (2018) ‘Applications of low-cost sensing technologies for air quality monitoring and exposure assessment: How far have they gone?’, Environment International, 116, pp. 286–299. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R. et al. (2022) ‘Pollution and health: A progress update’, The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(6). [CrossRef]

- Noble, C.A. et al. (2001) ‘Federal reference and equivalent methods for measuring fine particulate matter’, Aerosol Science and Technology, 34(5), pp. 457–464. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xin, Chen, X. and Zhang, Xiaobo (2018) ‘The impact of exposure to air pollution on cognitive performance’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), pp. 9193–9197. [CrossRef]

- Manisalidis, I. et al. (2020) ‘Environmental and health impacts of Air Pollution: A Review’, Frontiers in Public Health, 8. [CrossRef]

- Martenies, S.E. , Wilkins, D. and Batterman, S.A. (2015a) ‘Health impact metrics for Air Pollution Management Strategies’, Environment International, 85, pp. 84–95. [CrossRef]

- Castell, N. , Dauge, F. R., Schneider, P., Vogt, M., Lerner, U., Fishbain, B., Broday, D., & Bartonova, A. (2017). Can commercial low-cost sensor platforms contribute to air quality monitoring and exposure estimates? Environment International Vol. 99, pp. 293–302.

- Hegde, M. , Nebel, J.-C., & Rahman, F. (2024). Cleaning up the Big Smoke: Forecasting London’s Air Pollution Levels Using Energy-Efficient AI. International Journal of Environmental Pollution and Remediation Vol. 12, not yet published.

- Yang, B.-Y. et al. (2020) ‘Ambient air pollution and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis’, Environmental Research, 180, p. 108817. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R. et al. (2022) ‘Pollution and health: A progress update’, The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(6). [CrossRef]

- www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/low-cost-air-pollution-monitors-and-indoor-air-quality.

- Snyder, E.G. et al. (2013) ‘The changing paradigm of Air Pollution Monitoring’, Environmental Science & Technology, 47(20), pp. 11369–11377. [CrossRef]

- Taheri Shahraiyni, H. et al. (2015) ‘The development of a dense urban air pollution monitoring network’, Atmospheric Pollution Research, 6(5), pp. 904–915. [CrossRef]

- US EPA, O. (2016) EPA Scientists Develop and Evaluate Federal Reference & Equivalent Methods for Measuring Key Air Pollutants. https://www.epa.gov/air-research/epa-scientists-develop-and-evaluate-federal-reference-equivalent-methods-measuring-key.

- Hoekman, S.K. and Welstand, J.S. (2021) ‘Vehicle emissions and air quality: The early years (1940s–1950s)’, Atmosphere, 12(10), p. 1354. [CrossRef]

- Apte, J.S. and Manchanda, C. (2024) ‘High-resolution urban air pollution mapping’, Science, 385(6707), pp. 380–385. [CrossRef]

- Ródenas García, M. et al. (2022) ‘Review of low-cost sensors for indoor air quality: Features and applications’, Applied Spectroscopy Reviews, 57(9–10), pp. 747–779. [CrossRef]

- Shairsingh, K. et al. (2023) ‘Who air quality database: Relevance, history and future developments’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 101(12), pp. 800–807. [CrossRef]

- Carotenuto, F. et al. (2023) ‘Low-Cost Air Quality Monitoring Networks for long-term field campaigns: A Review’, Meteorological Applications, 30(6). [CrossRef]

- Bittner, A.S. et al. (2022) ‘Performance characterization of low-cost air quality sensors for off-grid deployment in rural Malawi’, Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 15(11), pp. 3353–3376. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, D. et al. (2020) ‘A chronology of Global Air Quality’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 378(2183), p. 20190314. [CrossRef]

- Carotenuto, F. et al. (2023) ‘Low-Cost Air Quality Monitoring Networks for long-term field campaigns: A Review’, Meteorological Applications, 30(6). [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.R. et al. (2021) ‘From low-cost sensors to high-quality data: A summary of challenges and best practices for effectively calibrating low-cost Particulate Matter Mass Sensors’, Journal of Aerosol Science, 158, p. 105833. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. et al. (2024) ‘Research of low-cost air quality monitoring models with different machine learning algorithms’, Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 17(1), pp. 181–196. [CrossRef]

- Bush, T. et al. (2022) ‘Machine learning techniques to improve the field performance of low-cost air quality sensors’, Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 15(10), pp. 3261–3278. [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, K. et al. (2024) Enhancing accuracy of air quality sensors with machine learning to augment large-scale monitoring networks, Nature News. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41612-024-00833-9 (Accessed: 26 January 2025).

- Kumar, P. et al. (2015) ‘The rise of low-cost sensing for managing air pollution in cities’, Environment International, 75, pp. 199–205. [CrossRef]

- Seesaard, T. , Kamjornkittikoon, K. and Wongchoosuk, C. (2024) ‘A comprehensive review on advancements in sensors for air pollution applications’, Science of The Total Environment, 951, p. 175696. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Trejo, A. et al. (2024) ‘Air quality monitoring with low-cost sensors: A record of the increase of PM2.5 during Christmas and New Year’s Eve celebrations in the city of Queretaro, Mexico’, Atmosphere, 15(8), p. 879. [CrossRef]

- Brugnone, F. , Randazzo, L. and Calabrese, S. (2024) ‘Use of low-cost sensors to study atmospheric particulate matter concentrations: Limitations and benefits discussed through the analysis of three case studies in Palermo, Sicily’, Sensors, 24(20), p. 6621. [CrossRef]

- Okorn, K. and Iraci, L.T. (2024) ‘An overview of outdoor low-cost gas-phase air quality sensor deployments: Current efforts, trends, and limitations’, Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 17(21), pp. 6425–6457. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. et al. (2020) ‘Low-cost sensors as an alternative for long-term air quality monitoring’, Environmental Research, 185, p. 109438. [CrossRef]

- Popoola, O.A.M. et al. (2018) ‘Use of networks of low cost air quality sensors to quantify air quality in urban settings’, Atmospheric Environment, 194, pp. 58–70. [CrossRef]

- Low-cost sensors can improve air quality monitoring and People’s Health (2024) World Meteorological Organization. Available at: https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/low-cost-sensors-can-improve-air-quality-monitoring-and-peoples-health (Accessed: 26 January 2025).

- Bililign, S. et al. (2024) ‘East African megacity air quality: Rationale and framework for a measurement and Modeling Program’, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 105(8). [CrossRef]

- Nalakurthi, N.V. et al. (2024) ‘Challenges and opportunities in calibrating low-cost environmental sensors’, Sensors, 24(11), p. 3650. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z. et al. (2024) ‘Humidity-independent gas sensors in the detection of hydrogen sulfide based on ND2O3-loaded in2o3 porous nanorods’, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 403, p. 135237.

- Khreis, H. et al. (2022) ‘Evaluating the performance of low-cost air quality monitors in Dallas, Texas’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), p. 1647. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, T. et al. (2024) Sustaining low-cost PM2.5 monitoring networks in South Asia: Technical challenges and solutions [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Mead, M. I. , Popoola, O. A. M., Stewart, G. B., Landshoff, P., Calleja, M., Hayes, M., Baldovi, J. J., McLeod, M. W., Hodgson, T. F., Dicks, J., Lewis, A., Cohen, J., Baron, R., Saffell, J. R., & Jones, R. L. (2013). The use of electrochemical sensors for monitoring urban air quality in low-cost, high-density networks. Atmospheric Environment Vol. 70, pp. 186–203.

- Kumar, P. et al. (2015) ‘The rise of low-cost sensing for managing air pollution in cities’, Environment International, 75, pp. 199–205. [CrossRef]

- Dharaiya, V.R. et al. (2023) ‘Evaluating the performance of low-cost PM sensors over multiple coalesce network sites’, Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 23(5), p. 220390. [CrossRef]

- Karagulian, F. et al. (2019) ‘Review of the performance of low-cost sensors for air quality monitoring’, Atmosphere, 10(9), p. 506. [CrossRef]

- Bililign, S. et al. (2024) East African megacity air quality: Rationale and framework for a measurement and Modeling Program, AMETSOC. Available at: https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/bams/105/8/BAMS-D-23-0098.1.xml (Accessed: 26 January 2025).

- Thara Seesaard, a. et al. (2024) A comprehensive review on advancements in sensors for air pollution applications, Science of The Total Environment. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969724058522 (Accessed: 26 January 2025).

- Varaden, D. , Leidland, E. and Barratt, B. (2019) The Breathe London Wearables Study Engaging primary school children to monitor air pollution in London. Greater London Authority. Available at: https://erg.ic.ac.uk/research/docs/Uploads_to_exposure_science_website/Final%20BLW%20Report_211019%20.pdf (Accessed: 26 January 2025).

- Wenwei Che, et al. (2020). PRAISE-HK: A personalized real-time air quality informatics system for citizen participation in exposure and health risk management.

- Mahajan, S. et al. (2022) ‘Translating citizen-generated air quality data into evidence for shaping policy’, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Lung, S.-C.C. et al. (2022) Research priorities of applying low-cost PM2.5 sensors in Southeast Asian countries, International journal of environmental research and public health. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8835170/ (Accessed: 26 January 2025 ).

- Bililign, S. et al. (2024a) East African megacity air quality: Rationale and framework for a measurement and Modeling Program, AMETSOC.

- Higgins, C. , Kumar, P. and Morawska, L. (2024) ‘Indoor air quality monitoring and source apportionment using low-cost sensors’, Environmental Research Communications, 6(1), p. 012001. [CrossRef]

- Liang Y et al. 2021 Field comparison of electrochemical gas sensor data correction algorithms for ambient air measurements Sensors Actuators B 327 128897. [CrossRef]

- Air Quality Expert Group 2023 HM Governmet Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

- Coelho Rezende G, Le Calvé S, Brandner J J and Newport D 2019 Micro photoionization detectors Sensors Actuators B 287 86–94.

- Levy Zamora, M. et al. (2022) ‘Evaluating the performance of using low-cost sensors to calibrate for cross-sensitivities in a multipollutant network’, ACS ES&T Engineering, 2(5), pp. 780–793. [CrossRef]

- Chai, H. et al. (2022) ‘Stability of Metal Oxide Semiconductor Gas Sensors: A Review’, IEEE Sensors Journal, 22(6), pp. 5470–5481.

- Johnson, N. et al. (2018) ‘Using a gradient boosting model to improve the performance of low-cost aerosol monitors in a dense, heterogeneous urban environment’, Atmospheric Environment, 184, pp. 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Molaie, S. and Lino, P. (2021) ‘Review of the newly developed, mobile optical sensors for real-time measurement of the Atmospheric Particulate Matter Concentration’, Micromachines, 12(4), p. 416. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L. et al. (2022) ‘Optical measurement method of non-spherical particle size and concentration based on high-temperature melting technique’, Measurement, 198, p. 111375. [CrossRef]

- Hagan, D.H. and Kroll, J.H. (2020) ‘Assessing the accuracy of low-cost optical particle sensors using a physics-based approach’, Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 13(11), pp. 6343–6355. [CrossRef]

- Laref, R. et al. (2021) ‘Empiric unsupervised drifts correction method of electrochemical sensors for in field nitrogen dioxide monitoring’, Sensors, 21(11), p. 3581. [CrossRef]

- Leo Hohenberger, T. Leo Hohenberger, T. et al. (2022) ‘Assessment of the impact of sensor error on the representativeness of population exposure to urban air pollutants’, Environment International, 165, p. 107329. [CrossRef]

- Maag, B. , Zhou, Z. and Thiele, L. (2018) ‘A survey on sensor calibration in Air Pollution Monitoring deployments’, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 5(6), pp. 4857–4870. [CrossRef]

- Wei, P. , Ning, Z., Ye, S., Sun, L., Yang, F., Wong, K., Westerdahl, D., & Louie, P. (2018). Impact Analysis of Temperature and Humidity Conditions on Electrochemical Sensor Response in Ambient Air Quality Monitoring. Sensors Vol. 18, Issue 2, p. 59.

- Fine, G.F. et al. (2010) ‘Metal oxide semi-conductor gas sensors in environmental monitoring’, Sensors, 10(6), pp. 5469–5502.

- Afshar-Mohajer, N. et al. (2017) ‘Evaluation of low-cost electro-chemical sensors for environmental monitoring of ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon monoxide’, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 15(2), pp. 87–98. [CrossRef]

- Pang, X. et al. (2018) ‘The impacts of water vapour and co-pollutants on the performance of electrochemical gas sensors used for air quality monitoring’, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 266, pp. 674–684. [CrossRef]

- Zuidema, C. et al. (2019) ‘Efficacy of paired electrochemical sensors for measuring ozone concentrations’, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 16(2), pp. 179–190. [CrossRef]

- Cross, E.S. et al. (2017) ‘Use of electrochemical sensors for measurement of Air Pollution: Correcting interference response and validating measurements’, Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 10(9), pp. 3575–3588. [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, S.; Astolfi, M.; Gaiardo, A.; Malagù, C.; Rispoli, G.; Vincenzi, D.; Zonta, G. Investigating the Temperature-Dependent Kinetics in Humidity-Resilient Tin–Titanium-Based Metal Oxide Gas Sensors. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yin, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, D.; Gao, R. Metal Oxide Gas Sensors: Sensitivity and Influencing Factors. Sensors 2010, 10, 2088–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyungmin Kim, Jin Kuen Park, Jieon Lee, Yong Jung Kwon, Hyeunseok Choi, Seung-Min Yang, Jung-Hoon Lee, Young Kyu Jeong, Synergistic approach to simultaneously improve response and humidity-independence of metal-oxide gas sensors, Journal of Hazardous Materials, Volume 424, Part B, 2022, 127524, ISSN 0304-3894. [CrossRef]

- Afshar-Mohajer, N. , Zuidema, C., Sousan, S., Hallett, L., Tatum, M., Rule, A. M., … Koehler, K. (2018). Evaluation of low-cost electro-chemical sensors for environmental monitoring of ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon monoxide. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 15(2), 87–98. [CrossRef]

- Hayward, I.; Martin, N.A.; Ferracci, V.; Kazemimanesh, M.; Kumar, P. Low-Cost Air Quality Sensors: Biases, Corrections and Challenges in Their Comparability. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastine, B.; Hummelgård, C.; Bryzgalov, M.; Rödjegård, H.; Martin, H.; Schröder, S. Compact Non-Dispersive Infrared Multi-Gas Sensing Platform for Large Scale Deployment with Sub-ppm Resolution. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.K. (2022) ‘Non-dispersive Infrared Gas Sensing Technology: A Review’, IEEE Sensors Journal, 22(1), pp. 6–15. [CrossRef]

- Muller, M. et al. (2020) ‘Integration and calibration of non-dispersive infrared (NDIR) CO2 low-cost sensors and their operation in a sensor network covering Switzerland’, Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 13(7), pp. 3815–3834. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.R. et al. (2017) ‘Evaluation and environmental correction of ambient CO2; measurements from a low-cost Ndir Sensor’, Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 10(7), pp. 2383–2395. [CrossRef]

- Wei Xu, Yunfei Cai, Song Gao, Shuang Hou, Yong Yang, Yusen Duan, Qingyan Fu, Fei Chen, Jie Wu, New understanding of miniaturized VOCs monitoring device: PID-type sensors performance evaluations in ambient air. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2021; 330, 129285ISSN 0925-4005. [CrossRef]

- Spinelle, L. et al. (2017) ‘Review of portable and low-cost sensors for the ambient air monitoring of benzene and other volatile organic compounds’, Sensors, 17(7), p. 1520. [CrossRef]

- Bilek, J.; Marsolek, P.; Bilek, O.; Bucek, P. Field Test of Mini Photoionization Detector-Based Sensors—Monitoring of Volatile Organic Pollutants in Ambient Air. Environments 2022, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, A. et al. (2017) ‘Highly sensitive and selective VOC sensor systems based on semiconductor gas sensors: How to?’, Environments, 4(1), p. 20. [CrossRef]

- Nabil Abdullah, A. et al. (2020) ‘Effect of environmental temperature and humidity on different metal oxide gas sensors at various gas concentration levels’, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 864(1), p. 012152. [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi H, Rahbarpour S, Hosseini-Golgoo S, Jamaati H, Reducing the destructive effect of ambient humidity variations on gas detection capability of a temperature modulated gas sensor by calcium chloride, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, Volume 331, 2021, 129091, ISSN 0925-4005,.

- Isaac, N.A. , Pikaar, I. & Biskos, G. Metal oxide semiconducting nanomaterials for air quality gas sensors: operating principles, performance, and synthesis techniques. Microchim Acta 189, 196 (2022).

- Peterson, P. et al. (2017) ‘Practical use of metal oxide semiconductor gas sensors for measuring nitrogen dioxide and ozone in urban environments’, Sensors, 17(7), p. 1653. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.D. et al. (2024) ‘Gamma: A universal model for calibrating sensory data of multiple low-cost air monitoring devices’, Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 128, p. 107591. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S. and Kumar, P. (2020) ‘Evaluation of low-cost sensors for quantitative personal exposure monitoring’, Sustainable Cities and Society, 57, p. 102076. [CrossRef]

- Rahi, P. , Sood, S.P., Bajaj, R. et al. Air quality monitoring for Smart eHealth system using firefly optimization and support vector machine. Int. j. inf. tecnol. 13, 1847–1859 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Laref, R. et al. (2018) ‘Support vector machine regression for calibration transfer between electronic noses dedicated to air pollution monitoring’, Sensors, 18(11), p. 3716. [CrossRef]

- Topalović, D.B. et al. (2019) ‘In search of an optimal in-field calibration method of low-cost gas sensors for ambient air pollutants: Comparison of linear, multilinear and artificial neural network approaches’, Atmospheric Environment, 213, pp. 640–658. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. and Choi, K. (2024) Calibration methods for low-cost particulate matter sensors considering seasonal variability, MDPI.

- Rezaei, R., Naderalvojoud, B., and Gullu, G.: A Comparative study of Deep Learning Models on Tropospheric Ozone Forecast- ing Using Feature Engineering Approach, Atmosphere, 14, 239. [CrossRef]

- Nalakurthi, N.V.S.R. et al. (2024) Challenges and opportunities in calibrating low-cost environmental sensors, Sensors (Basel, Switzerland).

- An Wang, Yuki Machida, Priyanka deSouza, Simone Mora, Tiffany Duhl, Neelakshi Hudda, John L. Durant, Fábio Duarte, Carlo Ratti, Leveraging machine learning algorithms to advance low-cost air sensor calibration in stationary and mobile settings, Atmospheric Environment, Volume 301, 2023, 119692, ISSN 1352-2310. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, N. , Presto, A. A., Kumar, S. P. N., Gu, J., Hauryliuk, A., Robinson, E. S., & Robinson, A. L. (2018). A machine learning calibration model using random forests to improve sensor performance for lower-cost air quality monitoring. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques Vol. 11, Issue 1, pp. 291–313.

- Clarity, Air quality monitoring 2.0 article, https://www.clarity.io/blog/air-quality-monitoring-2-0-how-different-types-of-air-monitoring-technologies-are-contributing-to-a-more-holistic-understanding-of-air-pollution.

- Sofía Ahumada, Matias Tagle,Yeanice Vasquez, Rodrigo Donoso, Jenny Lindén,Fredrik Hallgren,Marta Segura andPedro Oyola, Calibration of SO2 and NO2 Electrochemical Sensors via a Training and Testing Method in an Industrial Coastal Environment, Sensors 2022.

- Eben, S. Cross, Leah R. Williams, David K. Lewis, Gregory R. Magoon, Timothy B. Onasch, Michael L. Kaminsky, Douglas R. Worsnop, and John T. Jayne, Use of electrochemical sensors for measurement of air pollution: correcting interference response and validating measurements, AMT 2017.

- Weybourne Atmospheric Observatory [Accessed on 31 January 2025].

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).