1. Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) and their encapsulated microRNAs (miRNAs) are emerging as crucial tools for the diagnosis and treatment of human disease [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

EVs are nanovesicles that originate from cells with a role in intercellular communication [

12,

13,

14]. They carry a variety of biomolecules which play significant roles in both physiological and pathological processes [

15]. Research has shown that EVs are involved in the progression of disease, associating for example to tumor growth stage [

16,

17,

18] or to degeneration in neurodegenerative disorders [

2,

3]. Their ability to carry information from parental cells catalogues them as mediators to influence the behavior of target cells, becoming critical in the understanding of human physiology as well as in the mechanisms of disease [

13,

14,

19]. These findings unleashed a crusade to intensively explore EVs potential as biomarkers for early disease detection and for disease monitoring. EVs can also provide insights into drug efficacy and individuals response to treatment, highlighting their wide potential as tools in clinical settings [

1,

3,

8]. Their biomarker capacity extends to guiding therapy in cardiovascular and other diseases challenged with post-treatment recidivism, such as cancers, neurodegenerative conditions or tissue repair treatments [

2,

4,

5,

10,

20,

21,

22,

23].

EVs can be found in many body fluids, including blood, urine, saliva, and other which provide the media for EV-based long-range cell-cell communication [

6,

8]. Thus, becoming valuable for liquid biopsy minimally invasive approaches in the development of precision medicine programs, and in accurate prediction of patient prognosis and treatment outcomes [

9].

On another side, microRNAs or miRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules, typically 21-25 nucleotides in length, that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level [

24]. They play important roles in both physiological and pathological processes, and their dysregulation has also been observed in numerous diseases, making them attractive targets for diagnosis and treatment methods as well [

3,

25]. Encapsulation of miRNAs within EVs provides an additional layer of stability and specificity for the action of miRNAs [

8,

9,

10]. EV double-membrane protects miRNAs from enzymatic degradation, preserving their integrity in circulating fluids, with EV surface markers and cargoes often reflecting health status of their parental cells, thus providing insights into tissue or cell-type origin of the pathology and its associated mechanisms [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

While the potential of EVs and their miRNA contents seems promising in future clinical applications, there are still challenges to standardize their research and their use in the clinic. This review provides an updated overview of the main methods used for the isolation of EVs from biofluids and for the downstream inspection of the miRNAs contained within, while highlighting associated advantages and disadvantages for each method. It also provides examples of EV-encapsulated miRNAs catalogued as disease biomarkers while summarizing the methods used for their identification. This information may serve as valuable guidance for future research initiatives in the promising field of disease diagnostic and treatment based on EV-encapsulated miRNAs.

2. EVs: Biogenesis, Function, and Clinical Potential

The first observation of EVs seems to trace back to the 1940s when small particles shedding off platelets were noticed while studying blood cells under a microscope; particles that were later coined “platelet dust” by Wolf (1967) [

30,

31]. At this time there was no clue of the universality and relevance of this phenomenon. In 1969, EVs were described while describing the process of bone formation. Those EVs were named matrix vesicles, seemingly helping in the process of the hardening of bones, which led to propose their involvement in an important physiological process [

32,

33].

Then, EVs were found to be released also by intestinal cells, suggesting that EVs may come from different cell types, possibly representing a universal process. In the 80s EVs were detected in cellular cultures and informed as “particles with a morphology like viruses”, indicating that EVs may display various appearances [

34,

35]. During this decade, vesicles were discovered also in semen, where they received the name of prostasomes. These and other accumulation of findings pointed at EVs being present in many or perhaps all body fluids possibly performing different functions [

36], with implications in pathological processes [

37].

In 1983, it was found that some of the vesicles, nowadays named exosomes, come from inward budding processes, driving the formation of larger structures within cells or multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs) [

38]. In the late 1990s, a significant breakthrough occurred when researchers discovered that exosomes could present antigens, triggering immune responses, representing a major step in understanding of how EVs can influence the immune system [

39].

In 2006 and 2007, EVs were found to contain RNA, including microRNAs [

40]. This discovery sparked great interest because it showed that EVs could carry genetic information acting as directional communication vehicles between cells in a new way of long-range cell-to-cell communication. Since then, EVs have been isolated from many different types of cells and body fluids, such as saliva, urine, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid and breast milk among other, leading to the current general acceptance that EVs spread throughout our bodies being involved in many health-relevant functions [

6,

8,

9].

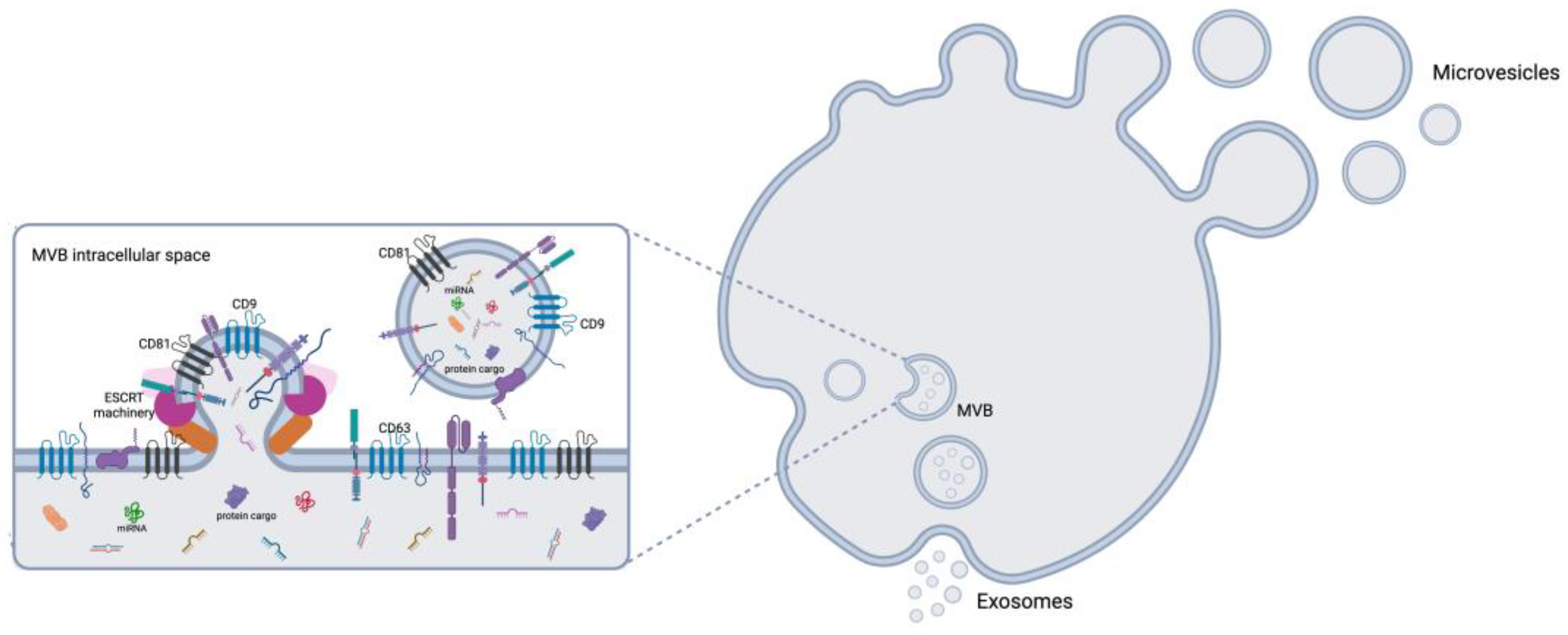

2.1. Biogenesis of EVs

EVs are heterogeneous membrane-bound particles released by practically all cell types. They are classified into three main groups based on their size and origin: exosomes (30–150 nm), microvesicles (100–1,000 nm), and apoptotic bodies (500–2,000 nm). Exosome biogenesis begins within endosomes, which develop into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (

Figure 1) [

13,

41,

42,

43], which can either fuse with lysosomes for degradation or merge with the plasma membrane to release exosomes [

44]. Key regulators of this process include the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery, tetraspanins, including CD9, CD63 and CD81, and lipid-dependent pathways such as ceramide-mediated mechanisms [

45,

46,

47]. Microvesicles, by contrast, originate by outward budding of the plasma membrane, driven by cytoskeletal reorganization and lipid redistribution processes (

Figure 1) [

12,

45,

48].

2.2. EV Function

EVs mediate long-range intercellular communication by transferring their cargo to target cells (directional transfer), which includes proteins, lipids, DNA, and RNA (miRNAs included), exerting their influence in numerous biological processes such as immune modulation [

49], angiogenesis [

16,

18], cellular proliferation [

50], and many other. EVs also play roles in disease by promoting tumor progression through metastasis, mediating immune evasion, drug resistance, and other. For example, cancer-derived EVs can modify the tumor microenvironment by delivering oncogenic factors to stromal cells [

8,

15,

16,

17,

22].

2.3. EVs Clinical Potential

EVs are being studied as therapeutic delivery vehicles due to their natural biocompatibility, ability to evade immune surveillance, and efficient cellular uptake. Engineered EVs can deliver therapeutic molecules, including miRNAs, siRNAs, proteins, and drugs, to target cells [

11,

51,

52]. For instance, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived EVs have shown promising results in treating inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases by delivering anti-inflammatory cytokines or neuroprotective factors [

53,

54]. EV-based therapies for cancer are also being explored, with preclinical studies showing success in delivering chemotherapeutics and suppressing tumor growth [

55]. As mentioned earlier, EVs are being considered as non-invasive biomarkers for diagnostic purposes due to their wide presence in biological fluids that can be obtained less invasively than solid tissues, such as blood, urine, saliva, or cerebrospinal fluid [

6,

13].

Standardization of simplified EV isolation techniques allowing translation of EV potential for either application: diagnosis or treatment are intensively pursued. Current main protocols used for the isolation of EVs include ultracentrifugation, precipitation, immunoaffinity capture, flow cytometry, size-exclusion chromatography and microfluidics [

56,

57]. Downstream analyses of isolated EVs, including proteomic and RNA sequencing, enable the identification of disease-specific signatures. However, in this review we will concentrate on detection of miRNAs which in addition to their diagnostic value are envisioned as potential therapeutic options.

3. Methods to Isolate EVs

EVs can vary in size, cargo, and surface markers which can help in their cataloguing and influence their optimized isolation methods.

Isolating EVs is a complex task due to their small size and the variety of types present in the fluid of interest. Nowadays, there is not a unique standardized optimal method for EV isolation since each method presents strengths and weaknesses. Different isolation methods favor the purification of certain types of EVs over other and thus, the optimized method may need tailoring according to disease type. In addition, contaminants like for example protein clumps or other particles that are not EVs may complicate their downstream analysis [

58,

59,

60,

61]. Understanding the particularities of each method seems crucial for the translation of methods into a clinical setting. The main EV isolation methods used in research are:

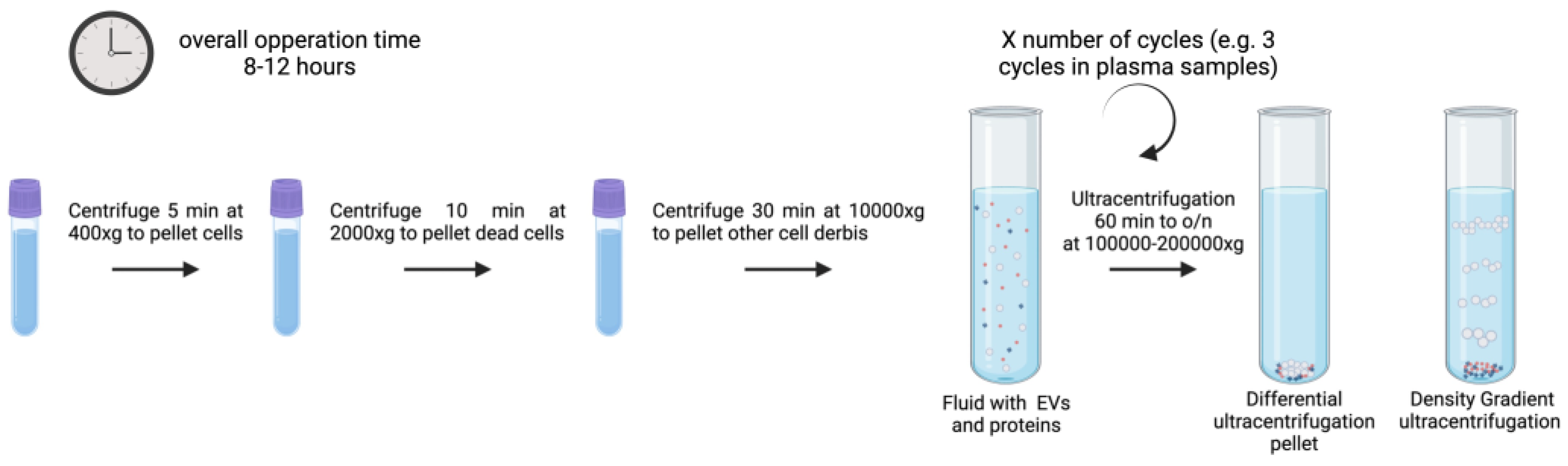

3.1. Ultracentrifugation

Ultracentrifugation (UC) is the most widely used exosome separation technique. The conventional UC approach relies on the sedimentation principle [

62,

63]. And in research it is commonly used to isolate EVs from nearly all biofluid samples including plasma, breast milk, cerebrospinal fluid, amniotic fluid, urine, aqueous humor, and cell culture lines [

12,

63]. Cells, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies are separated using a sequence of low-speed centrifugations, and EVs are finally obtained using a high-speed UC set at 100,000-150,000x g [

64], as illustrated in

Figure 2. All centrifugation steps must be performed at 4ºC. The EV pellet can then be reconstituted in phosphate-buffered saline or another stable buffer and stored for further analysis at -80 ºC or at 4ºC for their short-term use.

UC allows upscaling of the process [

65]. However, the EV structure may be disrupted by applying large shear forces during UC. Main drawbacks being EV loss, fusion, distortion, and co-isolation of contaminants like proteins or other complexes [

66,

67]. While effective, it often requires larger volumes compared to other techniques due to the low abundance of EVs in biofluids and UC equipment capacity [

68]. Differential UC (dUC) and density gradient UC (DGUC)are two subtypes of the technique.

3.1.1. dUC

dUC is commonly used to purify exosomes from other vesicles, proteins, and cell debris. Often also called UC, uses serial rounds of centrifugation with a number of cycles and speed depending on the vesicle size range under isolation [

69,

70]. The sedimentation coefficient (S), which is correlated with exosome size and density. dUC requires intense hands-on for the process of programming spin cycles and running them to separate pellets and supernatants. It also demands larger sample quantities since significant losses are expected by repeated cycles of sample transfer between tubes [

71]. The principle of this method is the use of low centrifugal force to remove big particles and cell debris to then isolate purified EVs from supernatants at higher forces. To pellet cells, big detritus, apoptotic bodies, and clumps of biopolymers, biological fluid samples are first centrifuged at 500, 3000, and 10,000-16,000x g for up to one hour. The exosomes are extracted from the supernatant by one to three cycles of centrifugation of 1–6 hour/eachs at 100,000–150,000x g. The exosome pellets are then resuspended in sterile filtered phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer for their immediate use but can also be stored at -80 °C for an extended periods.

This method’s primary benefits are its low processing costs, capacity to handle large sample volumes (1–25 ml), simultaneous separation of multiple EV samples, and absence of additional chemicals needed for the procedure.

This process is time-consuming and is dependent on rotor type and its characteristics, as well as the temperature and viscosity of the starting liquid (properties of the biofluid under study) [

72]. Limitations include heterogeneity of fluid composition and the presence of many vesicles of comparable sizes and protein aggregates that can co-form at 100,000 x g. Additionally, exosome aggregation occurs at high centrifugal speeds over extended periods of time.

Figure 2 illustrates a typical UC process as described previously [

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70] for different biofluids (plasma, urine, cell culture media, etc.) with volumes ranging from 1 to 25 ml and estimated overall operation times of 8 to 12 hours.

3.1.2. DGUC

DGUC, sometimes referred to as isopycnic UC, uses a number of solvents of different densities displayed discontinuously to trap exosomes between different layers [

25]. DGUC centrifugation enhances particle separation efficiency according to their buoyant density values enabling separation of subcellular components [

68]. DGUC centrifugation separates exosomes based on the variations in their mass density and size relative to other constituents in shorter time and reduced number of cycles as compared to dUC.

It also takes shorter times than dUC. It is considered a practical method for EV subtype isolation. However, its success depends on the type of rotor and its properties, as well as the initial liquid’s temperature and viscosity. Additional cleaning procedures are required since the EVs will be obtained in a solution that is typically incompatible with downstream analysis. Standard centrifugation methods must be optimized based on the characteristics of the biofluid samples and the rotor being used [

72].

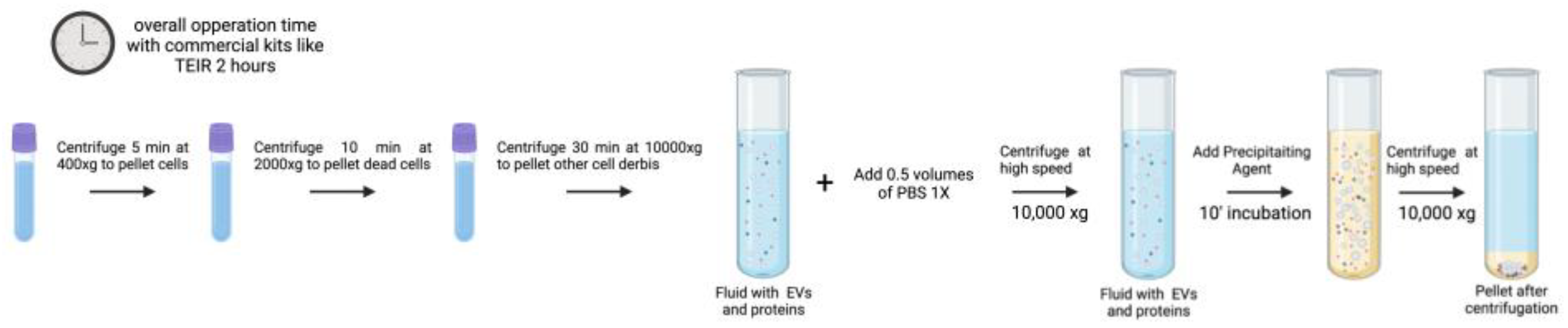

3.2. Precipitation

Precipitation-based techniques mostly use highly hydrophilic polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) or its derivatives, to chemically precipitate EVs [

73]. The process of EV precipitation relies on the presence of PEG which indices crowding and exclusion effects reducing the solubility by bringing exosomes closer to each other while disrupting the hydration layers surrounding exosomes [

74]. In this approach, samples are coincubated with 8–12% 6 kDa PEG solution at 4 °C overnight. Experimental evidence has demonstrated that adding positively charged protamine molecules may promote vesicle aggregation during the incubation phase [

75]. To separate EVs from serum, Helwa et al. assessed ultracentrifugation and three commercial precipitation kits utilizing PEG: the miRCURY Exosome Kit (Qiagen, USA), the Total Exosome Isolation Reagent (TEIR; Invitrogen, USA), and ExoQuick-Plus (System Biosciences, USA) [

62]. The quantity of EVs recovered by differential centrifugation was approximately 130 times lower than that of commercial kits, depending on the beginning volume. Except for TEIR, which produced yields notoriously higher than miRCURY, the yields of all other commercial kits were reported similar [

62]. The ExoQuick manufacturer protocol states that the samples used in tests are precleared to remove cells and cellular debris. The cleared solution is then incubated with the appropriate volume of ExoQuick for 0.5–12 hours, depending on the sample origin. After incubation, the solution is centrifuged for 20 minutes at 16,000 x g at 4 ºC to pellet the EVs. The pellet can be resuspended in the appropriate sample buffer, such as sterile-filtered PBS, and analyzed or stored at -80 °C [

76]. The final preparation barely contains any precipitating agent, but since the pellet is collected by high-speed centrifugation frequently contains clumps of proteins and other contaminants.

The precipitation-based isolation technique does not require specialized equipment, is quick, simple, affordable, and only requires a modest sample size. Since it does not damage EVs and does not call for any extra equipment, precipitation is recognized as the most straightforward and quick technique for isolating EVs. For clinical research, these features seem the most desirable.

The poorer product purity is a drawback of the method [

77,

78]. High protein contamination limits the use of precipitation techniques to analyze EV samples under certain conditions. Furthermore, exosomes that have been separated by precipitation techniques could include biopolymers that may interfere with downstream assays. An efficient pre-filtration step utilizing a 0.22 μm filter or a post-precipitation purification procedure that involves additional centrifugation, or an additional 0.22 μm filtration could reduce contamination with non-EV pollutants [

79]. Exosome isolation from human biological fluids has greatly improved thanks to upgrades and improvements to the original polymer precipitation method. Two commercial kits that use polymer precipitation with an increased yield and purity in comparison to formerly mentioned are ExoQuick Plus (System Biosciences, USA) and ExoEasy (Qiagen, The Netherlands) [

80]. Commercial kits provide a practical alternative for quick and labor-saving methods to isolate EVs, but their lack of specificity imposes limitations for downstream applications.

Figure 3 illustrates a graphical summary of a commercial EV isolation kit as described by the “Total Exosome Isolation (from plasma) Invitrogen” manufacturer protocol. This protocol has been optimized for plasma samples, while the described PEG precipitation protocol can be used in all types of fluids. For this process the overall operation time is 2 hours, and for a conventional PEG-precipitation protocol, the time increases to up to 24 hours [

62,

73,

74,

75]. The volume of work can be easily scaled, but the optimal working sample volume goes from 0.1 to 1 mL [

62].

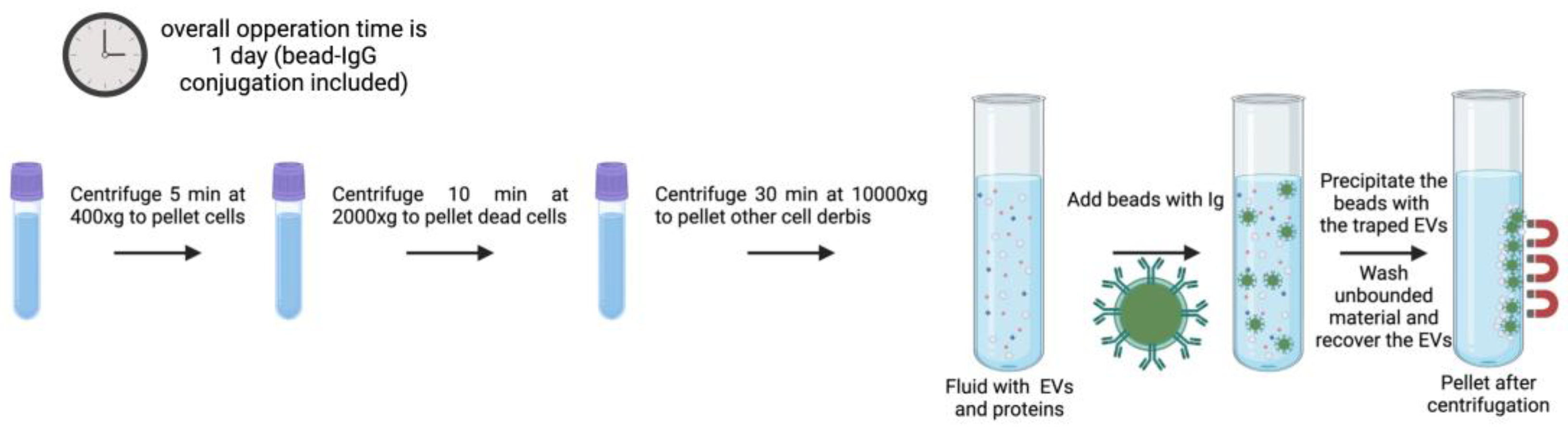

3.3. Immunoaffinity

These strategies are based on the identification of specific EV subsets according to their surface protein composition. Certain proteins and receptors are commonly present in some EVs populations [

81], offering a chance to anchor antibodies for immunoaffinity-based EV isolation (

Figure 4) [

82]. Immunoaffinity-based EV capture may in theory be used towards any protein or cell membrane component that is expressed on EV membranes and that does not count with soluble equivalents in the fluid. Transmembrane proteins, heat shock proteins, platelet-derived growth factor receptors, fusion proteins (such as flotillins, annexins, and GTPases), lipid-related proteins, and phospholipases are some of the exosome markers that have been identified over the last few decades [

82,

83,

84,

85]. Databases of proteins contained in exosomes, such as Exocarta, Vesiclepedia, EVpedia, ExoRBase or EV-TRACK were built for the study of EVs and may facilitate the selection of particular subpopulations by immunoaffinity. EVs have a wide variety of markers on their membranes, some of the most generally used for immunoaffinity of exosomes are the tetraspanins CD9, CD63 or CD81; despite not all exosomes contain these three tetraspanins concomitantly on their surface. Therefore, with this technique it is not possible to isolate all EV types present in a sample, it rather focuses on the isolation of specific subpopulations. Immunoaffinity based isolation techniques preserves EVs functionality, allowing the study of effects (potential functions) of EV subtypes [

86].

In addition to the mentioned tetraspanins, other transmembrane proteins like Rab5, CD82, annexin, and Alix have been described for selective exosome isolation [

87,

88]. As a result, several exosome isolation products have been developed, such as the Exosome Isolation Kit CD81/CD63 (Miltenyi Biotec), the Exosome Isolation and Analysis Kit (Abcam), and the Exosome-human CD63 isolation reagent (Thermofisher). Immunoaffinity capture offers the opportunity to classify distinct EVs subpopulations of certain origin through their associated surface markers. A prior study showed that exosomes released by tumors could be specifically isolated, both from culture medium of tumor-derived cell lines and clinical samples, by using magnetic beads coated with antibodies recognizing EpCAM (a surface marker overexpressed on tumor derived exosomes) [

89]. Gathering exosomes of a particular origin offers crucial information about their parental cells which may be valuable for diagnosis and treatment options.

Figure 4.

Generalized example of immunoaffinity protocol for EV isolation with magnetic beads as the solid phase. The protocol timing may change depending on the target, however the overall estimated time of incubation is from 1h to overnight. EVs from all types of biofluids can be isolated using immunoaffinity. There is no strict working volume value, but it needs to be optimized according to sample viscosity [

90] (created with Biorender).

Figure 4.

Generalized example of immunoaffinity protocol for EV isolation with magnetic beads as the solid phase. The protocol timing may change depending on the target, however the overall estimated time of incubation is from 1h to overnight. EVs from all types of biofluids can be isolated using immunoaffinity. There is no strict working volume value, but it needs to be optimized according to sample viscosity [

90] (created with Biorender).

Solid matrices to attach antibodies, for immunoaffinity include agarose and magnetic beads, plastic plates, and different kinds of microfluidic devices, the latter under intensive development in the last years [

90]. The most often used are submicron-sized magnetic particles (commonly known as magnetic beads) (

Figure 4), the reasons being their broad binding surface, constituting near-homogeneous processes with excellent capture efficiency and sensitivity. They offer the possibility of handling very large initial sample volumes, enabling upscaling or downscaling for specific applications [

90]. Furthermore, its facility of operation and automatization facilitates its translation into potential diagnostic platforms when using disease-specific antibodies and magnetically induced cell sorting [

91].

Although immunoaffinity-based EV isolation methods guarantee high-purity exosome isolation by a simple process, the collected EV biological functions may be permanently impacted by the non-neutral pH and non-physiological elution buffers used in the process (to elute vesicles from the antibodies). Denatured EV samples are not suitable for exosome-based functional research and other therapeutic applications, although being typically acceptable for diagnostic reasons (e.g., by evaluating the genetic and protein contents of the EV) [

88,

92]. Recently to solve this problem, Nakai and colleagues used the Ca2+-dependent Tim4 protein, which binds selectively to phosphatidylserine, a protein that is highly expressed on the exosome surface, to build an exosome isolation device that overcomes the limitation imposed by antibody capture [

93].

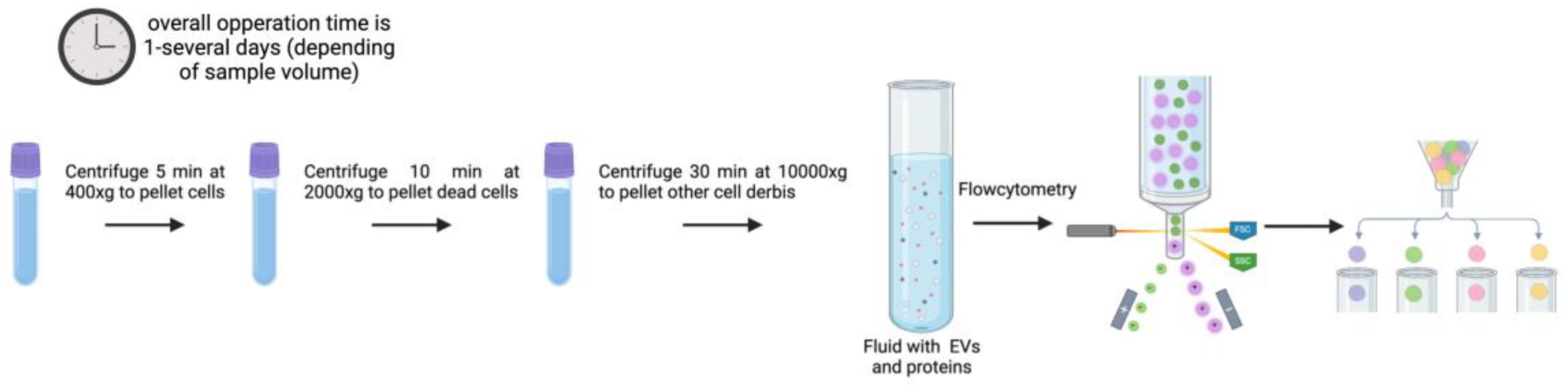

3.4. Flow Cytometry and Sorting

Since flow cytometry would enable high-throughput, multi-parametric analysis and separation (sorting) of individual EVs depending on their surface features, it seems of interest from the translation point of view. This is the reason behind the multiple efforts invested to improve this method. Low refractive index and submicron size of EVs are significant disadvantages when employing this method. Particles smaller than 600 nm are below detection limits on forward/side scattered (FSC/SSC) light detectors. This results in electrical noise and scattered light signals that overlap with the buffers [

94,

95].

Recently de Rond et al. [

96] described a new flow cytometry approach that can detect and isolate 100 nm EVs. This study focused on enhancing the forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) sensitivity of the FACSCanto flow cytometer to detect single 100 nm EVs. A crucial aspect for improvement because of the small size and low refractive index of EVs which typically place them below the detection limits of standard flow cytometers. The study systematically evaluated various adaptations to the optical configuration and fluidics of the flow cytometer. These improvements included changes to the obscuration bar shape, laser power, pinhole diameter, and sample stream width, among other. The goal was to improve the detection of scatter signals from EVs. The optimized FACSCanto was tested with both polystyrene beads and EVs isolated from human urine. The results showed that the optimized system could effectively measure the scatter signals from these particles, confirming its enhanced capacity to detect EVs. The study reported significant improvements in sensitivity, achieving estimated detection limits for EVs of 246 nm for FSC and 91 nm for SSC. This implies that with the right configurations, flow cytometry-based methods can constitute a powerful tool for isolating and analyzing EVs [

96].

Song et al. provided a thorough procedure (illustrated in

Figure 5) for isolating and purifying 50–200 nm small EV (sEV) using a flow cell sorter [

97]. To achieve a stable side stream and a decent sorting rate, a 50 µm nozzle and 80 psi sheath fluid pressure were chosen. Standard sized polystyrene microspheres were used to locate populations of 100, 200, and 300 nm particles. The sEV signal may be distinguished from the background noise with further adjustment of the voltage, gain, and FSC triggering threshold. A representative population of sEV can be obtained using FSC compared with SSC alone thanks to the panel of optimized sort settings. Numerous downstream research applications are possible with EVs isolated by the flow cytometry-based technology, which not only enables high-throughput analysis but also synchronous categorization or proteome analysis [

97]. Despite the advantages of this technique, it is a highly cost procedure. Access to modified flow cytometry equipment is something that very few laboratories can afford [

96,

97].

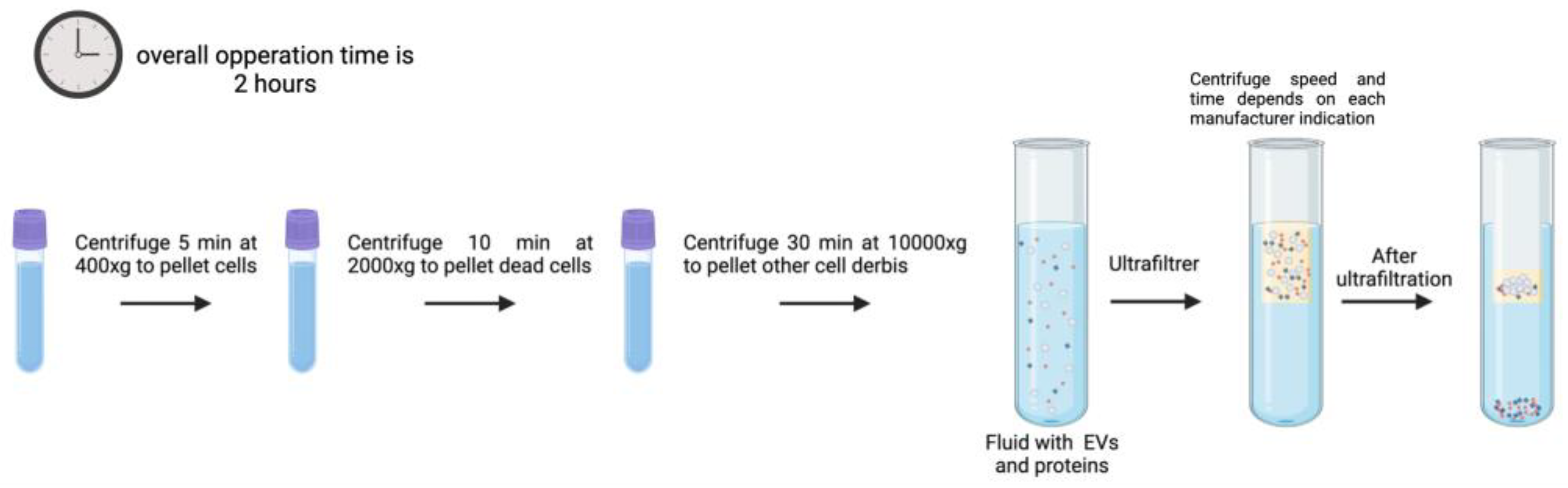

3.5. Ultrafiltration

With a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) value of 10, 50, and 100 kDa, ultrafiltration (UF) is used as a fundamental step to extract EVs from large volumes from samples, into concentrated small volumes that can be used in further purification procedures or analysis (

Figure 6) [

98]. The idea behind this technique is that EVs will be purified with the use of membrane filters of pore size such that limits the passage or flow through of contaminants.

Using membrane filters with pore diameters of 0.22 and 0.45 μm, EVs are first separated from bigger pollutants such as cells, debris, and microparticles. Then, commercial membrane filters with molecular weight cutoffs ranging from 5 to 100 kDa, such as the Corning Disposable Bottle-Top Filter or the Acison Centrifugal Filter, are used to separate the soluble and aggregated proteins.

EVs are later separated using ultrafiltration, which uses pressure to force sample fluid through membranes with pores smaller than 100 nm [

90]. Membranes with nanoscale or greater pore widths can be used in additional procedures to filter out more unwanted particles. Although the procedure is faster than UC, the pressure used can result in vesicle loss due to membrane adhesion, vesicle fusion and damage from shear stress, and membrane blockage from particle aggregation, which might reduce EV yields and lengthen processing time [

90,

99]. Vesicle ultrafiltration techniques include tandem filtration, centrifugal ultrafiltration, tangential flow filtration, and sequential filtration [

90,

100].

Sequential filtration entails several rounds of filtration, each with a distinct molecular weight cutoff, whereas tandem filtration combines multiple filters in a single syringe. When the nanoporous membrane is rotated inside a tube, centrifugal force pushes the sample material through the membrane [

101,

102]. To prevent clogging and remove big particles from samples such as cells, intact organelles, apoptotic bodies, and protein aggregates, preliminary centrifugation or dead-end filtering at 0.22 μm prior to centrifugal ultrafiltration is frequently used.

More recently, EVs have been isolated with greater yields using tangential flow filtration (TFF) [

100]. Instead of applying pressure orthogonally, TFF filters samples in tangential disposition to the membrane [

102]. EV loss may occur because of membrane damage and contamination by soluble components smaller than filter pores which are two drawbacks for this option. Additionally, some vesicles might be lost by absorption into the membrane at the crucial step of retrieving minute amounts of biological fluids. TFF can be scaled up to process larger volumes of fluid with improved consistency and with milder effects to the sample when compared to UC. However, TFF requires enhanced processing time than other filtration methods.

Compared to UC-based isolation methods, UF is simpler, quicker, and requires less special equipment. UF can damage EVs by shear stress, induce particle aggregation, which might impact EV yield [

90,

99,

100].

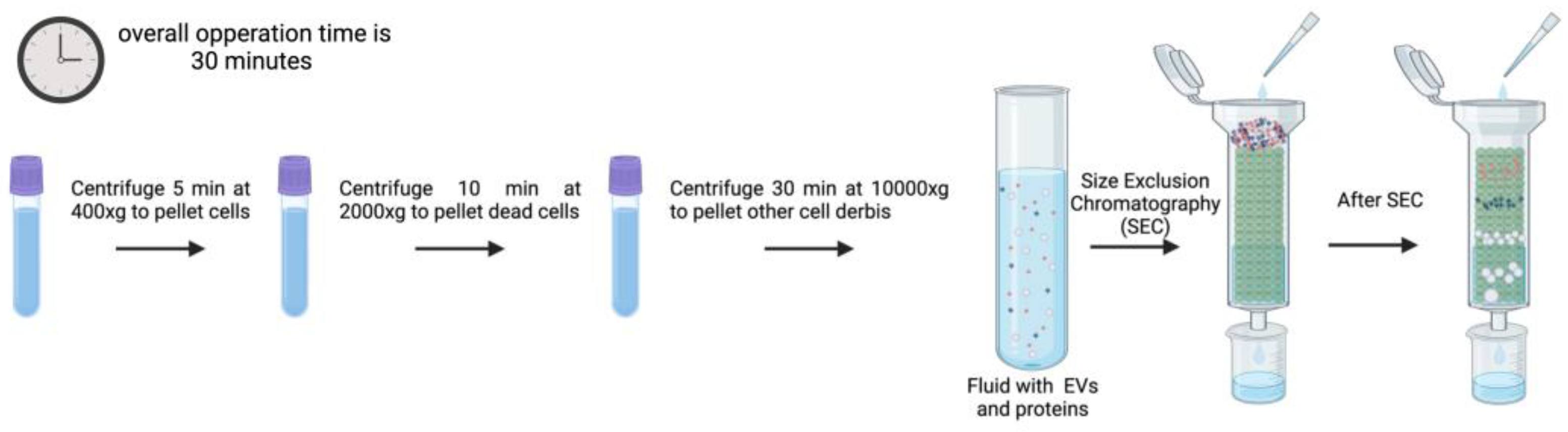

3.6. Size Exclusion Chromatography

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) or Gel Filtration is frequently used to separate biopolymers, such as proteins, polysaccharides, proteoglycans, etc., from fluids by allowing molecules with different hydrodynamic radius to be separated. This method can also be used to isolate EVs from blood plasma, protein complexes in urine, and lipoproteins [

103,

104,

105,

106,

107]. Since vesicles travel with the fluid flow (illustrated in

Figure 7) under a slight differential pressure and, seldomly interacting with the stationary phase, EV keep intact their integrity, preserve biological activity, and reflect abundance in origin during SEC [

108,

109]. Furthermore, biopolymer interaction and nonspecific contamination of EV preparations are reduced when high ionic strength buffers are used [

108]. Additionally, chromatography is easily scalable, with longer columns improving peak resolution for particles that are close in size, while larger columns enable the analysis of more concentrated materials from larger volumes. However, it is important to mention that the number of components, the volumes analyzed, and the variation in diameter (hydrodynamic radius) of the particles to be separated impact separation efficiencies [

108].

Several commercial column types have been developed to make the process of EV isolation by SEC easier and more reproducible. These include Sephacryl S-400 (GE Healthcare, UK), Sepharose 2B (Sigma, US), Sepharose CL-4B (Sigma, US), Sepharose CL-2B (30 mL; GE Healthcare, Sweden), and qEV Size Exclusion Columns (Izon Science Ltd., UK) [

110,

111]. When EV isolation efficiency is compared to commercial columns, it is shown that the resulting EV preparations differ in terms of both efficiency and albumin contamination level [

110].

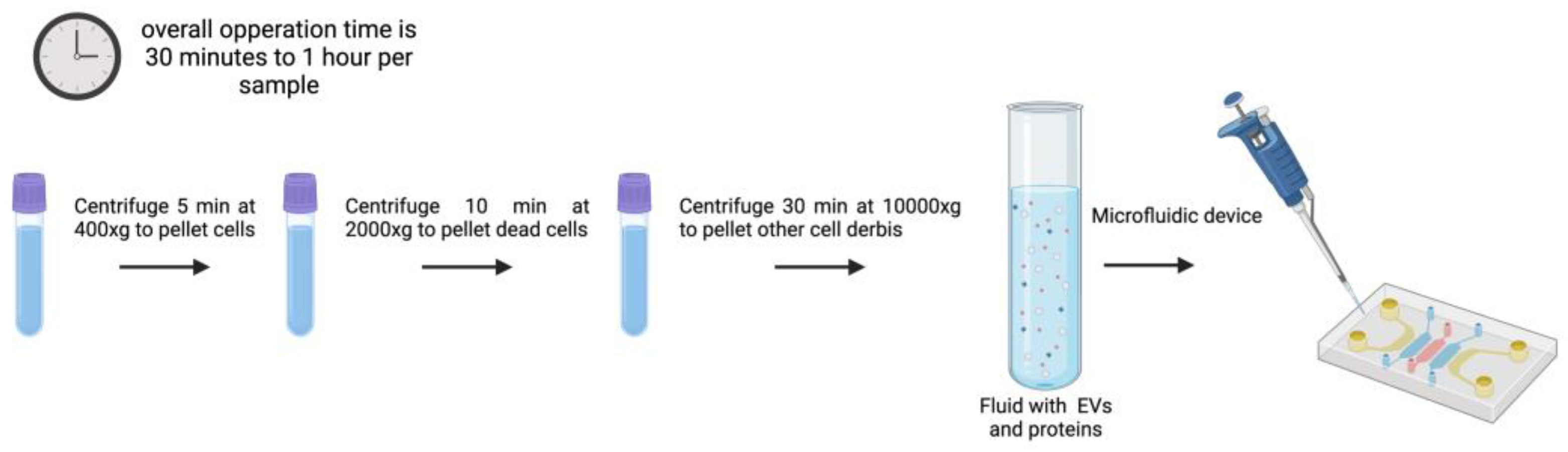

3.7. Microfluidics

There are different types of microfluidic devices developed to isolate EVs. The methodology described in 2015 by Dudani et al. [

112] for the isolation and detection of EVs focuses on a microfluidic platform based on immunoaffinity capture of vesicles using a technique called Rapid Inertial Solution Exchange (RInSE). To perform this method a microfluidic device is needed where fluid is introduced using PHD 2000 syringe pumps and Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) tubing. This setup allows for precise control of fluid flow rates during the isolation process.

An example of this protocol to isolate exosomes begins with the preparation of 20 µm polystyrene beads that are coated with streptavidin, and then incubated with biotinylated anti-human CD63 antibodies, a surface marker of exosomes, at 37°C for 30 minutes for bead coating. After removal of unbound antibodies, coated beads are resuspended in tris-buffered saline (TBS). This ensures that the beads are ready for the isolation of EVs from the sample solution (culture media or blood samples) [

112]. After the introduction of the anti-human CD63 antibody-coated beads intothe microfluidic device the fluid is pumped through the device with syringe pumps allowing the selective capture of exosomes by the beads in the microchannels. These devices operate at higher flow rates than traditional methods, enhancing the volume of fluid processed and, in consequence, improving the efficiency of EV isolation. . The inertial forces help to separate EVs from other particles in solution, enhancing the specificity of the isolation process. Once the exosomes are captured on the beads, an elution buffer (IgG elution buffer) is added to release the EVs from the beads. This step is crucial for obtaining isolated exosomes in a solution that can be further analyzed by their content and featuress [

112].

In particular, the

signal detection-based microfluidic approach [

112,

113] is one of the most recent techniques for separating exosomes from low amounts of biological fluids by using optical, electrochemical, or magnetic signals to detect exosomes. Microfluidics devices enable quick, precise, and economical isolation of exosomes from other nanometer-sized particles [

113,

114]. Popular microfluidic-based technologies fully integrate size-based, immunoaffinity-based, and dynamic separation of vesicles. It seems worth mentioning the recently developed ExoTIC device to isolate exosomes from serum or other physiological fluids [

82,

113] which outperforms PEG precipitation and UC alternatives in terms of yields, purity, and efficiency [

114].

Integrated systems, which consist of two or more devices constructed to function independently but in parallel, are known as microfluidic systems. Usually, a network of linked microchannels made up of one or more devices can handle smaller volumes of sample [

115,

116]. This feature makes microfluidic devices capable of accurately and specifically replicate intricate analytical processes at the microscale level. To promote fluid movement or expand the range of possible selection criteria, more specialized components might be added [

117].

Other devices incorporate

immunoaffinity-based microfluidic EV isolation techniques, which capture analytes using a general lateral flow [

118]. This process involves coating the base of a microfluidic device, like the ExoChip (made of polydimethylsiloxane), with antibodies against EV surface markers that are frequently overexpressed, such as CD9, CD63, and CD81 for exosome subpopulations [

119]. Still another example is represented by arrays of silicon nanowire micropillars that employ size exclusion to capture exosomes [

120]. Exosomes are caught in openings of this system as the fluid is pushed through. The initial phase of this process is quick, but it may take up to 24 hours for exosomes to be released from the pores limiting its diagnostic adequacy in terms of clinical settings.

EV separation by size has also been accomplished using a

viscoelastic-based microfluidic platform [

121,

122,

123]. Before being placed in viscoelastic buffer, samples are mixed with biocompatible, elastically responsive polymers of this platform. As the fluid passes through the devices, larger particles—such as cells, cell debris, and microvesicles from serum or cell culture medium with higher elastic pressures—are forced away from the EVs (

Figure 8). Meng et al. describe one example of this subtype of microfluidic platform to allow for the continuous and label-free isolation of exosomes straight from cancer patient blood samples. At a sample volumetric flow rate of 200 μl/h, they found that the device effectively extracted EVs with a diameter of around 100 nm, demonstrating 97% purity and 87% recovery rate [

123].

Acoustic microfluidic approaches represent another variant of microfluidic technology that can be used to separate exosomes based on their size [

119,

124]. In contrast to micropillar arrays, acoustic waves are milder on vesicles and require less contact. A flowing sample is used by interdigital transducers to create waves all over it. The particle size cutoff at the two separation channels is determined by the wave frequency. While the waste from one channel solely contains exosomes with a purity of around 98%, the residue from the other channel contains both big microvesicles and apoptotic bodies. Each sample takes around 25 minutes to run in this scenario, and EVs maintain their biological function because there is no physical interaction.

In addition to using acoustics, microfluidics has also used electrical waves to separate exosomes without the need for labels or physical touch [

125].

Ion-based separation makes use of exosome greater negative charge in comparison to other particles as the principle for its purification [

126]. Mogi et al. developed a microfluidic device of this type containing two inlet and two exit channels. High and low voltage is used to separate positively and negatively charged particles [

126]. Positively charged particles are attracted to the low-voltage channel in this device, whereas negatively charged particles are attracted to the high-voltage channel in each pair. A perpendicular ion channel in the middle creates an ion depletion zone that pushes uncharged particles into the channels and keeps them toward the center. This device, which is tuned for voltage and flow rate to improve exosome retention has demonstrated notably greater yields than UC methods.

In addition, microfluidics-based technology can isolate EVs from a reduced volume of sample. It enhances capture efficiency and specificity, paving the way for automated and high-throughput EV detection in clinical settings. Another strength of this isolation method is that EVs keep their function capacity unaltered after their isolation. However, costs are still high and it is time consuming [

123].

3.8. EV Isolation Methods Overview

Main EV isolation methods rely on different principles leading to particular advantages and disadvantages sometimes tricky to be compared. To help choosing the isolation method that fits best an experimental aim, we have generated a summary table (

Table 1) with strengths and weaknesses for each of the methods depicted here.

4. Biogenesis and Function of microRNAs

Mature miRNAs play significant roles in gene regulation affecting important biological processes such as development, differentiation, apoptosis, and immune responses [

127]. As previously mentioned, dysregulated miRNA expression is observed with disease. Examples include cardiovascular disorders [

128], cancer [

129], or neurodegenerative disease [

130], as previously pointed.

4.1. microRNAs Biogenesis

miRNA biogenesis begins with the transcription of a long primary transcript called pri-miRNA typically transcribed by RNA polymerase II which contain a hairpin-like structure [

131].These pri-miRNA are processed in the nucleus by a micro-complex , primarily formed by the Drosha ribonuclease and the double-stranded RNA-bing protein DGCR8 (DiGeorge Syndrome Critical Region 8) to generate a shorter, hairpin-structured pre-miRNA [

132]. The pre-miRNA is then exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm via a protein called Exportin-5, which recognizes 2-nucleotide overhangs at the ends of the pre-miRNA structure [

133]. Once in the cytoplasm, the pre-miRNA gets processed further by the Dicer ribonuclease enzyme, which cleaves the loop of the pre-miRNA to produce a miRNA duplex that consists of a guide strand and a passenger strand. The guide strand is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), whereas the passenger strand is typically degraded [

134,

135]. The mature miRNA incorporated into the RISC complex guides the complex to complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) targets. The interaction between the miRNA and its target mRNA often leads to translational repression or mRNA degradation, thus regulating gene expression [

136,

137,

138].

There are alternative mechanisms and processes that contribute to miRNA regulation and function like for instance, some studies indicate that Dicer can be processed into different isoforms or interact with other RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), which can alter the processing of pre-miRNAs [

139]. A recent study has shown that certain miRNAs may bypass Dicer processing. These Dicer-independent pathways involve alternative RNA-processing enzymes like Argonaute 2 (Ago2), which directly cleaves precursor miRNA molecules into mature miRNAs [

140].

miRNA biogenesis can be modulated by tissue-specific factors or external stimuli such as stress, disease, or changes in the environment. This means that different tissues may have different sets of miRNAs, or certain signaling pathways may regulate the processing of specific miRNAs [

141]. RBPs can also regulate miRNA biogenesis by interacting with pri-miRNAs or pre-miRNAs [

142].

Some pri-miRNAs may undergo alternative splicing, generating multiple isoforms of pre-miRNAs or even different mature miRNAs from a single miRNA gene. This allows for finely-tuned regulation of miRNA function, particularly in complex biological processes like development, cell differentiation, and responses to stress [

143].

A recent publication suggests that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) can be processed to produce functional miRNAs. These lncRNAs may contain embedded miRNA genes or undergo complex splicing events that yield miRNA-like molecules, contributing to miRNA biogenesis from alternative RNA species [

144].

The exosome complex, known for its role in RNA degradation, can also participate in the processing of certain miRNAs. This suggests that there could be alternative pathways for miRNA maturation that do not involve the canonical Drosha/Dicer pathway [

145].

4.2. microRNAs Function

miRNAs primarily function as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression. miRNAs regulate gene expression by binding to complementary sequences within the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of target mRNAs [

146]. Thus, recruiting the RISC to degrade the mRNA or inhibit its translation. This regulatory capacity allows miRNAs to control key cellular processes, such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, immune response and metabolism [

147,

148,

149,

150].

In a disease context miRNAs may play different roles. For example, in cancer miRNAs often act as either oncogenes (oncomiRs) or tumor suppressors; e.g., miR-21 is an oncomiR frequently upregulated in cancers, promoting tumor growth and metastasis by targeting tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN and PDCD4. Conversely, the let-7 family of miRNAs functions as tumor suppressors by inhibiting oncogenic pathways, including those mediated by RAS and MYC [

151]. Dysregulation of miRNAs is implicated in a broad spectrum of diseases beyond cancer, including cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune dysregulation-associated pathologies [

152].

4.3. microRNAs in Therapy

miRNAs have emerged as promising therapeutic targets due to their critical roles in disease mechanisms, their simplicity and stability [

153]. Some strategies to modulate miRNA activity include:

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs): synthetic nucleotides s known as ASOs could selectively attach to target mRNAs or miRNAs and disrupt or block their activity. In the context of cancer this strategy could work to restore tumor suppressor expression. ASOs can also be chemically modified to further improve stability and specificity for improved results.

By specifically targeting oncogenic miRNAs that are important in carcinogenesis, such as miRNA-23a and miRNA-106b, ASOs have shown to significantly reduce their activity [

154]. Because of their capacity to specifically target miRNAs and their engineered stability, ASOs treatments offer promising therapeutic options for novel cancer treatments [

155].

Ongoing clinical trials are expanding the use of miRNA-based therapeutic approaches for the treatment of genetic disorders, showcasing their versatility and wide potential [

156,

157].

AntagomiRs: antagomiRs are a specific type of ASOs designed to inhibit miRNAs.

Antagomir therapy is a promising approach for the modulation of miRNA activity in various medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease [

158], neurological disorders [

159], and cancer [

160]. This therapeutic strategy involves the use of chemically modified oligonucleotides designed to inhibit specific miRNAs, thereby restoring normal gene expression and cellular function.

AntagomiR-21 has shown to improve cardiac function post-myocardial infarction by reducing myocardial fibrosis and apoptosis, leading to enhanced ejection fraction and decreased left ventricular end-diastolic diameter [

158].In addition, a study performed by Huang et al., on ischemic stroke models, miR-15a/16-1 antagomiR significantly improved neurobehavioral outcomes and reduced infarct volume [

159].

Small Molecule Inhibitors: Small molecule inhibitors can block the pathological process by interfering with elements involved in miRNA biogenesis pathways. These inhibitors seek to restore normal gene expression patterns though different mechanisms, for instance, limiting tumor growth by suppressing oncogenic miRNA activity [

161].

Anti-miR-122 therapy is being explored as a potential treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and related liver diseases due to the critical role of microRNA-122 (miR-122) in HCV replication. The therapeutic approach aims to inhibit miR-122 activity, thereby reducing HCV replication and potentially improving patient outcomes [

162,

163]. These inhibitors work by transcriptionally inhibiting miR-122 expression, showcasing a novel therapeutic strategy against HCV [

164]. The use of anti-miR-122 therapy could lead to significant advancements in HCV treatment, particularly for patients with chronic infections where current antiviral therapies may be insufficient [

162].

In the context of this focused review it seems relevant to highlight that delivery vehicles such as nanoparticles and EVs are being explored to enhance the stability and specificity of miRNA-based therapeutics [

10,

160].

4.4. microRNAs in Diagnosis

miRNAs diagnostic value has been amply recognized due to their stability in biological fluids, disease-specific expression patterns, and non-invasive accessibility. Aberrant miRNA expression profiles have already been identified for a variety of diseases (

Table 2 and

Table 3), allowing early detection, monitoring or progression of disease, as well as prediction to treatment response [

3,

9].

Despite miRNA promising applications [

165,

166,

167,

168], clinical implementation of miRNA diagnostics faces the challenge of high variability in circulating miRNA expression levels potentially making results hard to interpret. An aspect further difficulted by the lack of standardized protocols [

169], and the limited sensitivity and specificity of current methods when evaluating heterogeneous samples [

170].

In the initial experimental discovery phase of miRNA biomarkers high-throughput -omic screens, such as microarrays, followed by validation of the most promising candidates by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) measurements has been popularly used [

171].

5. Methods to Assess miRNA Levels

The diagnostic use of miRNAs relies on their accurate detection and reproducible quantification in body fluids such as blood, urine, and saliva. Common methodologies include:

5.1. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

One of the most popular and sensitive method for measuring miRNA expression levels is qRT-PCR. Since miRNAs are short (~18-25 nucleotides), they cannot be directly retrotranscribed like mRNAs. To overcome their lack of polyA tail to anchor oligo-dT primers, the process includes a polyadenylation reaction prior to their reverse transcription (RT). qRT-PCR options include TaqMan-based miRNA TaqMan test (Life Technologies), SYBR green-based miScript (Qiagen), and SYBR green-based miRCURY LNA (Exiqon) [

172]. These popular methods have evolved into qRT-PCR arrays that can profile huge sets of circulating miRNAs at once, such as the TaqMan array miRNA 384 Cards (ThermoFisher), Smart Chip PCR (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan), and bespoke miScript miRNA PCR array (Qiagen) [

173].

qRT-PCR is a sensitive technique for measuring miRNA levels [

173,

174]. An amplification curve is produced using real-time monitoring of fluorescence linked to the amplification of cDNA obtained from miRNA species [

175]. Numerous software programs are available for analyzing qPCR curves, yielding quantification [

176].

Despite being a sensitive technique, problems may occur when working with target levels that are close to qPCR detection limits, as in the case of many circulating miRNAs. This results in missing data, which is processed and interpreted differently by several studies. There is currently no agreement on how to deal with missing data in qPCR experiments in a way that is statistically solid [

172,

173]. Therefore, it can be said that qRT-PCR is a highly sensitive and specific method to detect miRNAs but it is limited when the target abundance is close to the qRT-PCR detection limits [

177].

To specifically approach miRNA detection improval,

stem-loop priming has been developed. Stem-loop priming is a widely used technique for the reverse transcription of miRNAs, offering high specificity and efficiency in miRNA quantification. Unlike conventional linear primers, stem-loop primers are designed to anneal to the 3’ end of the miRNA, forming a hairpin structure that enhances the specificity of reverse transcription and prevents the amplification of precursor miRNAs. This method enables selective detection of mature miRNAs while reducing background signals from primary and precursor forms. Stem-loop priming also improves cDNA stability and facilitates efficient amplification [

234].

5.2. Microarray Analysis

As mentioned, an established -omic method for examining unbiased microRNA expression patterns is microarray analysis. Microarrays use probes complementary to known miRNAs immobilized on a solid surface. Upon labeling, miRNA samples are hybridized to these probes, with the resulting fluorescence signals revealing their presence and relative abundance in the sample [

178,

179]. The ability to concurrently identify several miRNAs at once and detect them across body fluids is one of the many clear benefits that microarray analysis offers when it comes to miRNA biomarlker identification. It constitutes a noninvasive and practical diagnostic technique, suitable for comparative expression profiling, despite holding lower sensitivity as compared to qRT-PCR. An additional limitation is that target probes can yield cross-hybridization leading to detection of false positives [

178].

5.3. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)

By contrast to microarrays NGS can render the discovery of novel miRNAs [

180]. It involves converting miRNA into cDNA libraries, which are then sequenced to determine the exact nucleotide sequences and quantities of miRNAs present in a sample. With the help of NGS, millions of DNA fragments can be sequenced quickly at once, enabling precise microRNA detection and characterization across their whole sequence [

153].

Background noise and cross-hybridization are issues that NGS technologies do not face when compared to other high-throughput techniques like microarrays. Other noteworthy benefits of the NGS include the ability to produce thorough and conclusive results of all miRNAs even in samples with low content such as plasma or serum [

181], and does not require previous knowledge of target miRNAs, [

182,

183]. However, it is not free of limitations with main being its high cost, and the requirement of time-consuming computational infrastructure for the analysis and interpretation of data [

184].

5.4. In Situ Hybridization

The expression and location of molecules within a cell, tissue, or embryo can be detected using the traditional in situ hybridization (ISH) technique. ISH methods were originally applied to the detection of miRNA in 2006 [

185]. They used tagged complementary nucleic acid probes to identify single-stranded DNA or RNA in tissue slices or fixed cells [

186]. ISH’s main benefit over other miRNA detection techniques is its capacity to track both cellular and subcellular distributions and identify the spatiotemporal expression profile of miRNAs. This technique is useful to clarify the biological function of miRNAs and their potential pathologic participation in a variety of disorders.

ISH is currently the only method for miRNA profiling that can identify the native localization of miRNA at a single cell level, inside tissues, or in cell compartments [

187]. Single molecule RNA FISH (smRNA-FISH) approaches have been made possible by recent developments in a variety of signal amplification and super-resolution imaging techniques.

ISH, however, has low throughput that limits its applications, but it can identify many miRNAs per reaction [

188]. FISH technology has advanced significantly with the development of new labeling techniques and the launch of high-resolution imaging systems for precise mapping of intra-nuclear genomic architecture and single-cell, single-molecule profiling of cytoplasmic RNA transcription, being used in the clinic for genetic diagnostics [

189,

190,

191].

5.5. Northern Blotting

Northern Blot (NB) for the analysis of miRNA levels is an easily accessible technology. It is carried out by size-separating RNAs species in a sample using denaturing gel electrophoresis, transferring and cross-linking it to a membrane, and then hybridizing it with a labeled nucleic acid probe complementary to the target RNA. Individual miRNA expression levels can be examined using this classical method [

192]. The benefit of NB analysis is that it can identify both mature and miRNA precursors at the same time. However, this method is costly, time-consuming, and requires labeling.

Quantitative analysis does not usually employ NB. It is regarded as semi-quantitative and offers data on the relative levels of RNA expression in a sample or between samples [

193,

194]. Both radioactive and non-radioactive probes can be employed for detection, and labeling techniques such as uniform probe labeling and end labeling are acceptable [

195,

196]. The most often used radioactive labeling method is

32P because of its high sensitivity. However, a major drawback is the short half-life of the probe, the health risk for the operator that needs to comply safety precautions, and specialized training related to the proper use of radioisotopes [

196].

5.6. Biosensors

Biosensors for the detection of microRNA have gained significant attention due to their potential for early disease diagnosis and monitoring in a clinical setting [

218]. Recent advancements in biosensor technology have focused on enhancing sensitivity, specificity, and dynamic range, making them suitable for clinical applications. Different types of biosensors have been developed as follows:

Nanochannel Biosensors: Solid-state nanochannel biosensors use allosteric DNA probes to achieve a programmable dynamic range for miRNA detection. By employing tri-block DNA architectures, these biosensors can adjust binding affinities, achieving a dynamic range of up to 10,900-fold which enhances their versatility in various applications [

197].

Electrochemical Biosensors: Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as effective tools for detecting miRNAs, particularly in cancer diagnostics. The principle of electrochemical biosensors is fundamentally based on the interaction between biological elements and electrochemical transducers, which convert biochemical signals into measurable electrical signals. These biosensors utilize various enzymes and biomolecules to achieve high sensitivity and specificity in detecting analytes [

179]. They are characterized by simplicity, sensitivity, and low cost, making them ideal for point-of-care applications. For instance, a novel electrochemical biosensor achieved a detection limit of 2.5 fM for miRNA-182-5p, demonstrating high sensitivity in complex samples [

178,

179].

Surface-enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Biosensor: When molecules are bonded to the “nanostructure” of substrates, Raman signals can be amplified by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Pyridine adsorbed on electrochemically rough silver electrodes provides the source for this phenomenon [

200]. In 1979, pyridine’s increased signal was also detected in a silver and gold colloidal solution [

201]. In line with the electromagnetic mechanism (EM) has been proved that SERS is more of a “nanostructure effect” than a “surface effect” with the critical role that surface plasmon resonance plays in SERS having been amply illustrated [

18]. The potential distribution observed in an electrochemical environment, which correlates to the chemical enhancement mechanism (CM) model, it can be used to show the critical function of charge transferred between a molecule and a substrate in SERS, what makes it suitable to detect miRNA particles [

202,

203]. Electromagnetic field and molecular polarization enhancement are the two models that these two mechanisms correlate to. While the latter focuses on the modification of the molecular electronic structure during the adsorption process, resulting in resonant Raman scattering, the former concentrates on enhanced electromagnetic fields on metal surfaces with an appropriate shape [

204,

205].

Surface Plasmon Resonance Aptasensors: The biotin-streptavidin dual-mode phase imaging surface plasmon resonance (PI-SPR) aptasensor represents another innovative approach, significantly improving detection limits and reducing nonspecific adsorption. This method allows for rapid, simultaneous detection of multiple miRNA markers, enhancing its utility in clinical settings [

206].

Biosensor techniques can provide rapid and in real-time miRNA detection and could be suitable for portable diagnostics. However, it requires careful design and optimization, and the isolation efficacy can be affected by biological sample complexity [

178,

179,

180,

181,

182,

183,

184,

185,

186,

187,

188,

189,

190,

191,

192,

193,

194,

195,

196,

197,

198,

199,

200,

201,

202,

203,

204,

205,

206].

5.7. Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR)

ddPCR partitions a miRNA-containing sample into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets. Each droplet undergoes individual PCR amplification, and fluorescence signals are measured to determine miRNA copy numbers without the need for a standard curve. Unlike qRT-PCR, ddPCR provides direct miRNA copy number measurements without requirement of reference genes. Capable of detecting low-abundance miRNAs, even in challenging samples like EVs [

207,

208], or in complex biological samples, such as plasma and serum. ddPCR is more expensive than qRT-PCR due to specialized reagents and equipment. Can analyze only a few miRNAs at a time compared to NGS and the sample partitioning must be optimized for accurate quantification [

207,

208].

5.8. NanoString

NanoString technology or nCounter offers a highly sensitive and robust platform for miRNA detection, enabling precise quantification without the need for reverse transcription or amplification [

235,

236]. This digital hybridization-based approach uses fluorescent barcoded probes that directly bind to target miRNAs [

235,

236]. This allows a multiplexed detection of hundreds of miRNAs in a single assay. Unlike qPCR and NGS, NanoString provides direct and absolute miRNA quantification. Additionally, it provides a high specific and sensitive option to detect low abundant miRNAs. It is reproducible and easy to use, making this technique a powerful tool for biomarker discovery and detection [

235,

236].

5.9. Overview of Methods to Quantify miRNA Levels

All miRNA detection methods described use different principles for their detection and therefore present different potential advantages and disadvantages which need to be evaluated according to specific goals.

Table 2 provides a summary of each of the methods presented together with their particular strengths and weaknesses.

Table 2.

Summary of strengths and weaknesses of each miRNA detection method described in section 5.

Table 2.

Summary of strengths and weaknesses of each miRNA detection method described in section 5.

| Detection method |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Reference |

| qRT-PCR |

High sensitivity and specificity.

Quantitative and widely used.

|

Requires prior sequence knowledge.

Limited detection of novel miRNAs. |

[174] |

| Microarray Analysis |

High-throughput detection of multiple miRNAs.

Suitable for comparative expression profiling. |

Lower sensitivity than qRT-PCR.

Detects only known miRNAs. |

[178] |

| NGS |

Allows discovery of novel miRNAs.

High sensitivity and dynamic range.

|

Expensive and requires complex bioinformatics.

Long turnaround time. |

[184] |

| ISH |

Provides spatial distribution of miRNA expression.

Single-cell resolution.

|

Less quantitative than qRT-PCR/NGS.

Requires high-quality tissue samples. |

[188,189] |

| NB |

Confirms miRNA integrity and size. |

Labor-intensive and requires large RNA amounts.

Low sensitivity.

|

[193,196] |

| Biosensors |

Rapid and real-time detection.

Potential for portable diagnostics. |

Requires careful design and optimization.

May be affected by biological sample complexity. |

[178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206] |

| ddPCR |

Absolute quantification without a standard curve.

High sensitivity, even for low-abundance miRNAs.

Resistant to PCR inhibitors.

|

More expensive than qRT-PCR.

Limited multiplexing capabilities. |

[207,208] |

| NanoString |

Direct and absolute quantification.

High specificity due to sequence-specific probes.

Multiplexing capability.

Works well with low RNA input and degraded samples.

High reproducibility and ease of use.

|

Lower sensitivity compared to qPCR for low-abundance miRNAs.

Higher cost per sample compared to some qPCR-based methods.

Requires specialized equipment (nCounter system). |

[235,236] |

To further illustrate the potential of miRNA detection in diagnostics

Table 3 compiles some examples of circulating miRNAs and their link to a particular disease. The detection method used in each study is also detailed to further document resources for methods to quantify miRNAs.

Table 3.

Examples of circulating miRNAs identified in the referenced studies as disease biomarkers.

Table 3.

Examples of circulating miRNAs identified in the referenced studies as disease biomarkers.

| Biomarker |

Associated disease |

Detection methodology |

Reference |

| miR-15a and miR-16 |

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

qRT-PCR |

[209] |

| miR-21 |

Various Cancers (e.g., breast, lung, prostate) |

qRT-PCR |

[210] |

| miR-126 |

Lung Cancer |

Microarray Analysis |

[211] |

| miR-122 |

Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

Northern Blot and qRT-PCR |

[212] |

| miR-155 |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

qRT-PCR |

[213] |

| miR-21, miR-126, miR-146a |

COVID-19 |

qRT-PCR |

[214] |

| miR-196b, miR-31, miR-891a, miR-34c, miR-653 |

Lung Adenocarcinoma |

Transcriptome Analysis |

[215] |

| miR-21, miR-155 |

Breast Cancer |

Electrochemical Biosensors |

[216] |

| miR-122, miR-192 |

Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

NGS |

[217] |

| miR-29a, miR-181b |

Alzheimer’s Disease |

Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Biosensors |

[218] |

6. microRNAs Encapsulated in Extracellular Vesicle in Diagnosis and Treatment

Encapsulated miRNAs, primarily found within EVs, offer a highly stable and biologically relevant source of disease biomarkers [

1]. These vesicles protect miRNAs from RNase-mediated degradation and facilitate their transport between cells located at very large distances within an organism, contributing to intercellular communication in physiological and pathological pathways [

8,

9]. The selective encapsulation of miRNAs into EVs is often influenced by disease-specific mechanisms, leading to distinct expression signatures that can serve as diagnostic and prognostic indicators [

5]. The different advancements in EV isolation and miRNA detection methods explained in previous sections highlight their potential in the context of precision medicine, enabling non-invasive detection and monitoring of disease. Some examples of EV-derived miRNAs identified as disease biomarkers are listed in the

Table 4 together with the used method for their identification.

The ability of EVs to protect miRNAs from enzymatic degradation enhances their stability and bioavailability, making this route attractive for therapeutic delivery [

10]. Moreover, engineered EVs can be designed to carry specific miRNAs to particular destinations, enabling targeted modulation of disease pathways [

10,

160]. EV derived miRNAs and other EV cargos show modulation of diverse cellular activities in different tissues and potential therapeutic efficacy in disease models [

229]. The EV derived miRNAs of MSC-derived EVs were suggested as the main bioactive compartment for their therapeutic effects [

229]. An additional example is provided by the finding that encapsulated miR-150-3p increases osteoblast development and proliferation in osteoporosis [

230]. miRNAs enclosed in MSC-derived EVs also showed possible modulation in cancer models. MiR-15a was shown to slow the evolution of carcinomas by blocking spalt-like transcription factor 4; while EV-derived miR-139-5p seems to prevent bladder carcinogenesis by targeting the polycomb repressor complex 1 [

231,

232]. In addition, tumor development and angiogenesis were effectively inhibited by EVs loaded with miR-497 [

233].

However, additional work is needed for validation of many of the findings and to standardize protocols before EV-encapsulated miRNAs can be implemented as treatments.

7. Discussion

EVs have gained increasing attention as potential biomarkers due to their ability to carry microRNAs that reflect the physiological and pathological states of their tissue of origin. Various isolation techniques, including UC, SEC, polymer-based precipitation, and microfluidics, have been employed to obtain EVs from biological samples. However, each method presents inherent limitations related to yield, purity, and processing time [

97,

98].

One of the primary challenges in EV research is the heterogeneity of vesicles and the diversity of isolation protocols, which can lead to inconsistencies in downstream analyses hindering clinical translation of findings.

Comparative studies have shown that differences in isolation methods can significantly impact EV yields and their microRNA contents, affecting the reproducibility of results [

99]. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of each technique is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach based on the aims of downstream applications.

Standardization efforts, such as those led by the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles, aim to establish guidelines for EV isolation and characterization to promote reproducibility and facilitate data comparison across studies [

1]. Initiatives that underscore the importance of optimizing isolation techniques and implementing quality control measures to ensure the clinical utility of EV-based diagnostics.

Future research should focus on developing automated and scalable isolation methods that combine high efficiency with minimal sample processing time. Additionally, the integration of multi-omic approaches and artificial intelligence-driven data analysis could expedite the translation of EV and miRNA-based diagnostics and therapeutics to the clinic.

8. Conclusions

EVs and their encapsulated microRNAs have emerged as promising biomarkers for diagnostic applications, offering a minimally invasive approach for disease detection and monitoring. The ability of EVs to transport functional biomolecules across biological barriers underscores their potential utility in clinical settings. However, the success of EV-based diagnostics hinges on the development of reliable and reproducible isolation methodologies.

Despite the significant progress made in EV isolation techniques, establishment of standardized methods granting consistent yields, high purity, and integrity of vesicles across different sample types and experimental conditions remains. The heterogeneity of EV populations and the complexity of biological fluids present additional challenges in achieving methodological uniformity.

Standardizing EV isolation protocols is a critical goal for the field, as it will enable more accurate characterization of vesicle-associated microRNAs and enhance their diagnostic applicability. Future research efforts should focus on refining existing techniques and developing consensus guidelines to facilitate cross-study comparability and clinical translation.

On another side, detection of miRNAs is a rapidly evolving field with significant implications for biomarker discovery, disease diagnostics, and therapeutic monitoring. While qRT-PCR, microarray analysis, NGS, ISH, NB, biosensors, ddPCR and NanoString each offer unique strengths, none of them is considered better over the other. The selection of an optimal detection platform depends on factors such as sensitivity, specificity, cost, and throughput. Emerging technologies aim to address the current limitations by improving sensitivity, reducing cost, and making data interpretation easier with an expected significant impact in the advancement of this field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization M.L. and E.O..; drawings M.L. ; writing—original draft preparation M.L. and E.O.; writing—review and editing, M.L. and E.O.; supervision, E.O.; funding acquisition, E.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Generalitat valenciana CIAICO, grant number 2021/103 to E.O. and UCV VIDI fellowship to M.L.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EV |

Extracellular Vesicle |

| miRNA |

microRNA |

| MVB |

Multi-Vesicular Bodie |

| ESCRT |

Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport |

| MSC |

Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| UC |

Ultracentrifugation |

| dUC |

Differential Ultracentrifugation |

| DGUC |

Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation |

| PEG |

Polyethylene Glycol |

| TEIR |

Total Exosome Isolation Reagent |

| FSC |

Forward Scattered |

| SSC |

Side Scattered |

| sEV |

Small Extracellular Vesicle |

| MWCO |

Molecular Weight Cutoff |

| UF |

Ultrafiltration |

| TFF |

Tangential Flow Filtration |

| SEC |

Size Exclusion Chromatography |

| RInSE |

Rapid Inertial Solution Exchange |

| PEEK |

Polyetheretherketone |

| TBS |

Tris-Buffered Saline |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| pre-miRNA |

miRNA precursor |

| DGCR8 |

DiGeorge Syndrome Critical Region 8 |

| RISC |

RNA-induced silencing complex |

| mRNA |

messenger RNA |

| Ago2 |

Argonaute 2 |

| RBP |

RNA-binding protein |

| lncRNAs |

long non-coding RNAs |

| UTR |

Untranslated Region |

| ASO |

Antisense Oligonucleotide |

| HCV |

Hepatitis C Virus |

| qPCR |

quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| qRT-PCR |

Quantitative Real-Time PCR |

| RT |

reverse transcription |

| cDNA |

complementary DNA |

| NGS |

Next Generation Sequencing |

| ISH |

In Situ Hybridization |

| smRNA |

Single molecule RNA |

| NB |

Northern Blot |

| SERS |

Surface-enhanced Raman Scattering |

| EM |

Electromagnetic Mechanism |

| CM |

Chemical-enhancement Mechanism |

| PI-SPR |

Phase Imaging Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| ddPCR |

Digital Droplet PCR |

References

- Das S, Lyon CJ, Hu T. A Panorama of Extracellular Vesicle Applications: From Biomarker Detection to Therapeutics. ACS Nano. 2024 Apr 9;18(14):9784-9797. Epub 2024 Mar 12. PMID: 38471757; PMCID: PMC11008359. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Zhang, X., Yang, Z. et al. Extracellular vesicles: biological mechanisms and emerging therapeutic opportunities in neurodegenerative diseases. Transl Neurodegener 13, 60 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Ashish et al. “MicroRNA expression in extracellular vesicles as a novel blood-based biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease.” Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association vol. 19,11 (2023): 4952-4966. [CrossRef]

- Phan, Thanh Huyen et al. “Made by cells for cells - extracellular vesicles as next-generation mainstream medicines.” Journal of cell science vol. 135,1 (2022): jcs259166. [CrossRef]

- EL Andaloussi, Samir et al. “Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities.” Nature reviews. Drug discovery vol. 12,5 (2013): 347-57. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, Raghu, and Valerie S LeBleu. “The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes.” Science (New York, N.Y.) vol. 367,6478 (2020): eaau6977. [CrossRef]

- Mustajab, Tamanna et al. “Update on Extracellular Vesicle-Based Vaccines and Therapeutics to Combat COVID-19.” International journal of molecular sciences vol. 23,19 11247. 24 Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bajo-Santos, Cristina et al. “Plasma and urinary extracellular vesicles as a source of RNA biomarkers for prostate cancer in liquid biopsies.” Frontiers in molecular biosciences vol. 10 980433. 3 Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Makarova, J et al. “Extracellular miRNAs and Cell-Cell Communication: Problems and Prospects.” Trends in biochemical sciences vol. 46,8 (2021): 640-651. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Eric Z et al. “Exosomal MicroRNAs as Novel Cell-Free Therapeutics in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine.” Biomedicines vol. 10,10 2485. 5 Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K., Liu, Q., Wu, K. et al. Extracellular vesicles as potential biomarkers and therapeutic approaches in autoimmune diseases. J Transl Med 18, 432 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, Buzas K, Casal E, Cappello F, Carvalho J, Colás E, Cordeiro-da Silva A, Fais S, Falcon-Perez JM, Ghobrial IM, Giebel B, Gimona M, Graner M, Gursel I, Gursel M, Heegaard NH, Hendrix A, Kierulf P, Kokubun K, Kosanovic M, Kralj-Iglic V, Krämer-Albers EM, Laitinen S, Lässer C, Lener T, Ligeti E, Linē A, Lipps G, Llorente A, Lötvall J, Manček-Keber M, Marcilla A, Mittelbrunn M, Nazarenko I, Nolte-’t Hoen EN, Nyman TA, O’Driscoll L, Olivan M, Oliveira C, Pállinger É, Del Portillo HA, Reventós J, Rigau M, Rohde E, Sammar M, Sánchez-Madrid F, Santarém N, Schallmoser K, Ostenfeld MS, Stoorvogel W, Stukelj R, Van der Grein SG, Vasconcelos MH, Wauben MH, De Wever O. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015 May 14;4:27066. PMID: 25979354; PMCID: PMC4433489. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L. M., and Wang, M. Z. (2019). Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells 8 (7), 727. [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, E., Boing, A. N., Harrison, P., Sturk, A., and Nieuwland, R. (2012). Classification, functions, and clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles. Pharmacol. Rev.64 (3), 676–705. [CrossRef]