Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

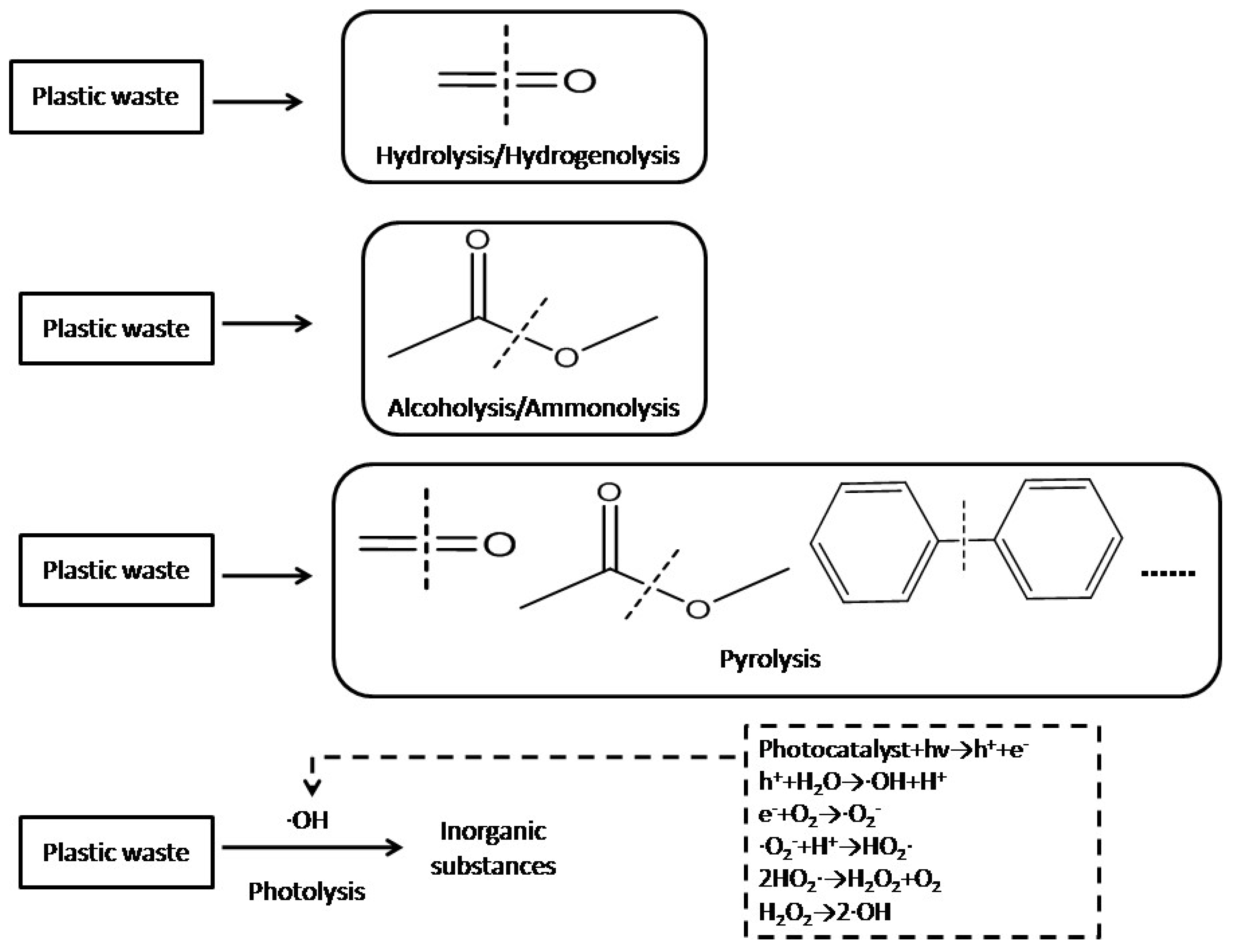

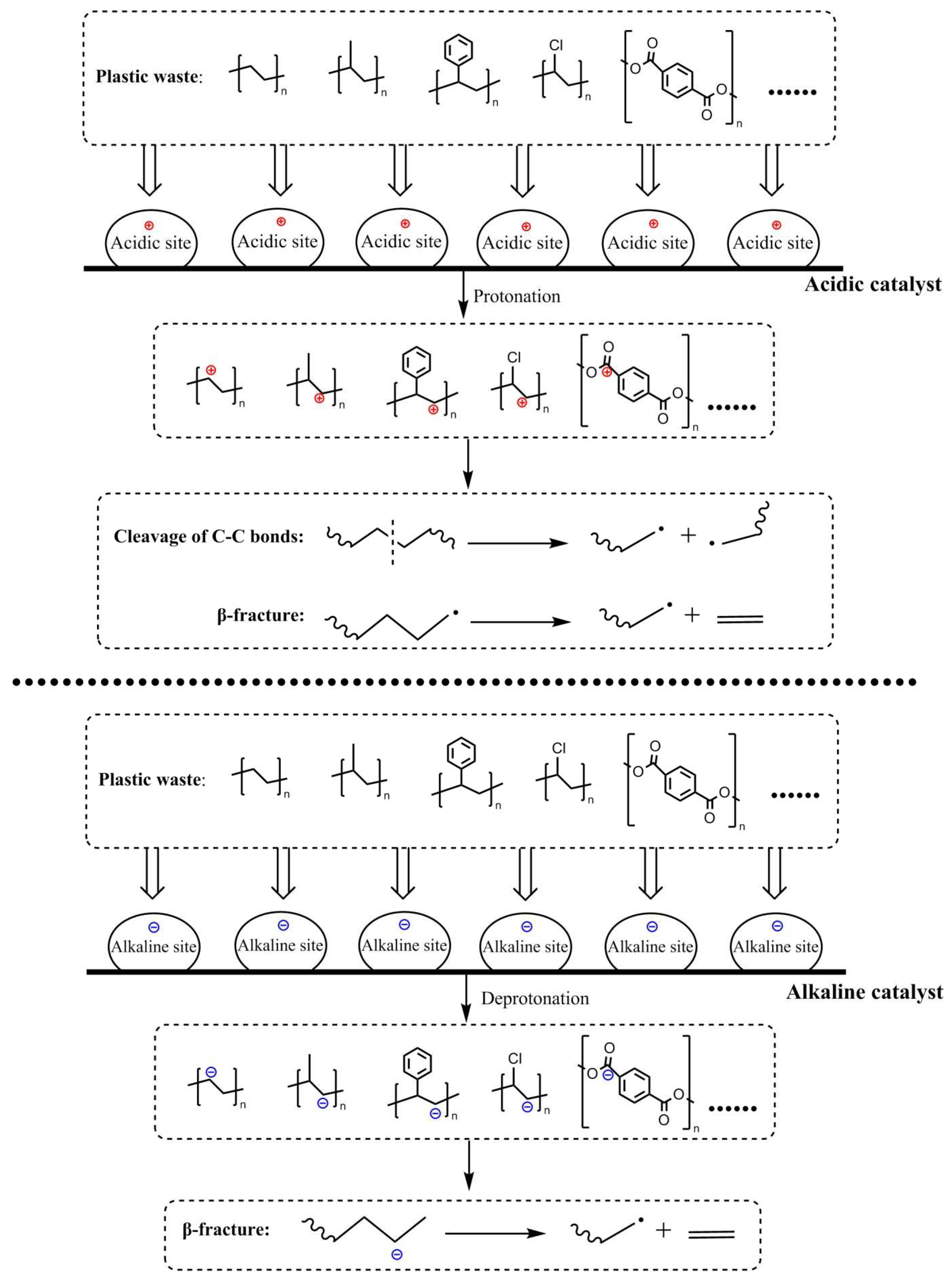

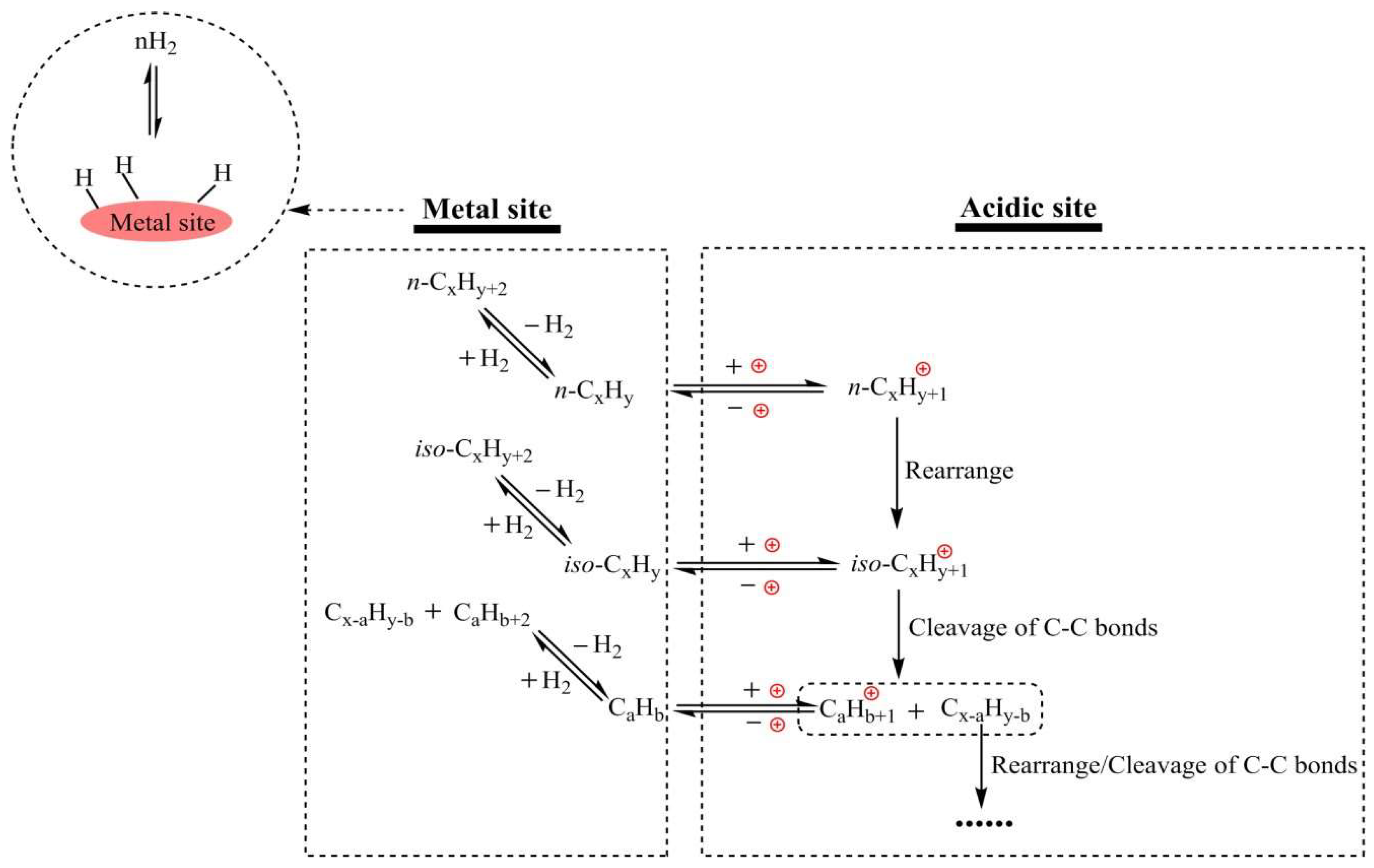

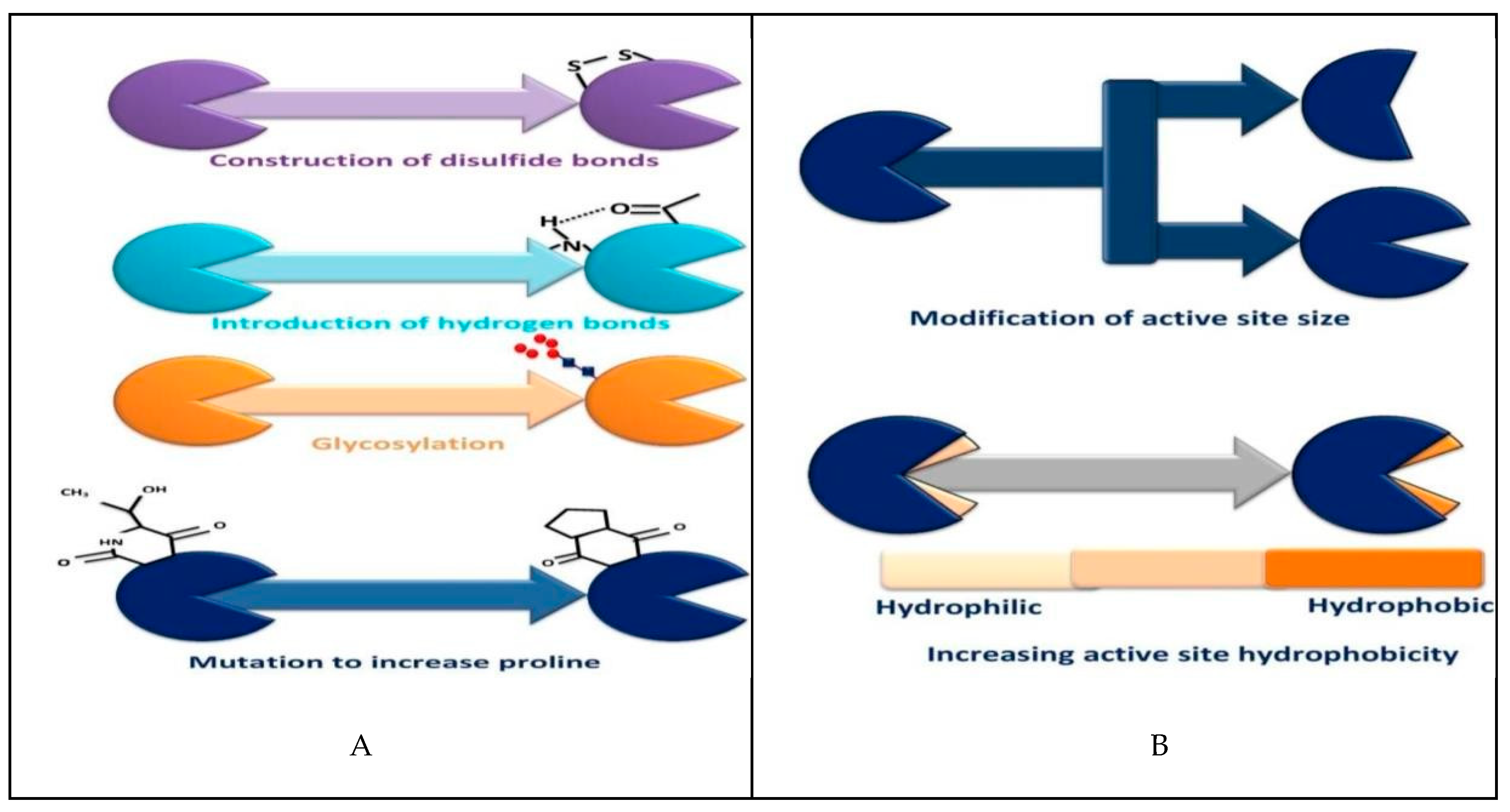

In recent years, vast amounts of plastic waste have been released into the en- vironment worldwide, posing a severe threat to human health and ecosystems. Despite the partial success of traditional plastic waste management technologies, their limitations underscore the need for innovative approaches. This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent advancements in chemical and biological technologies for converting and utilizing plastic waste. Key topics include the technical parameters, characteristics, processes, and reaction mechanisms underlying these emerging technologies. Addition- ally, the review highlights the importance of conducting economic analyses and life cycle assessments of these emerging technologies, offering valuable insights and establishing a robust foundation for future research. By leveraging literature from the past five years, this review explores innovative chemical approaches, such as hydrolysis, hydrogenolysis, alcoholysis, ammonolysis, pyrolysis, and photolysis, which break down high-molecular-weight macromolecules into oligomers or small molecules by cracking or depolymerizing specific chemical groups within plastic molecules. It also examines in- novative biological methods, including microbial enzymatic degradation, which employs microorganisms or enzymes to convert high molecular -weight macromolecules into oli- gomers or small molecules through degradation and assimilation mechanisms. The r e- view concludes by discussing future research directions focused on addressing the technological, economic, and scalability challenges of emerging plastic waste manage- ment technologies, with a strong commitment to promoting sustainable solutions and achieving lasting environmental impact.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Emerging Technologies

2.1. Chemical Methods

2.2. Biological Methods

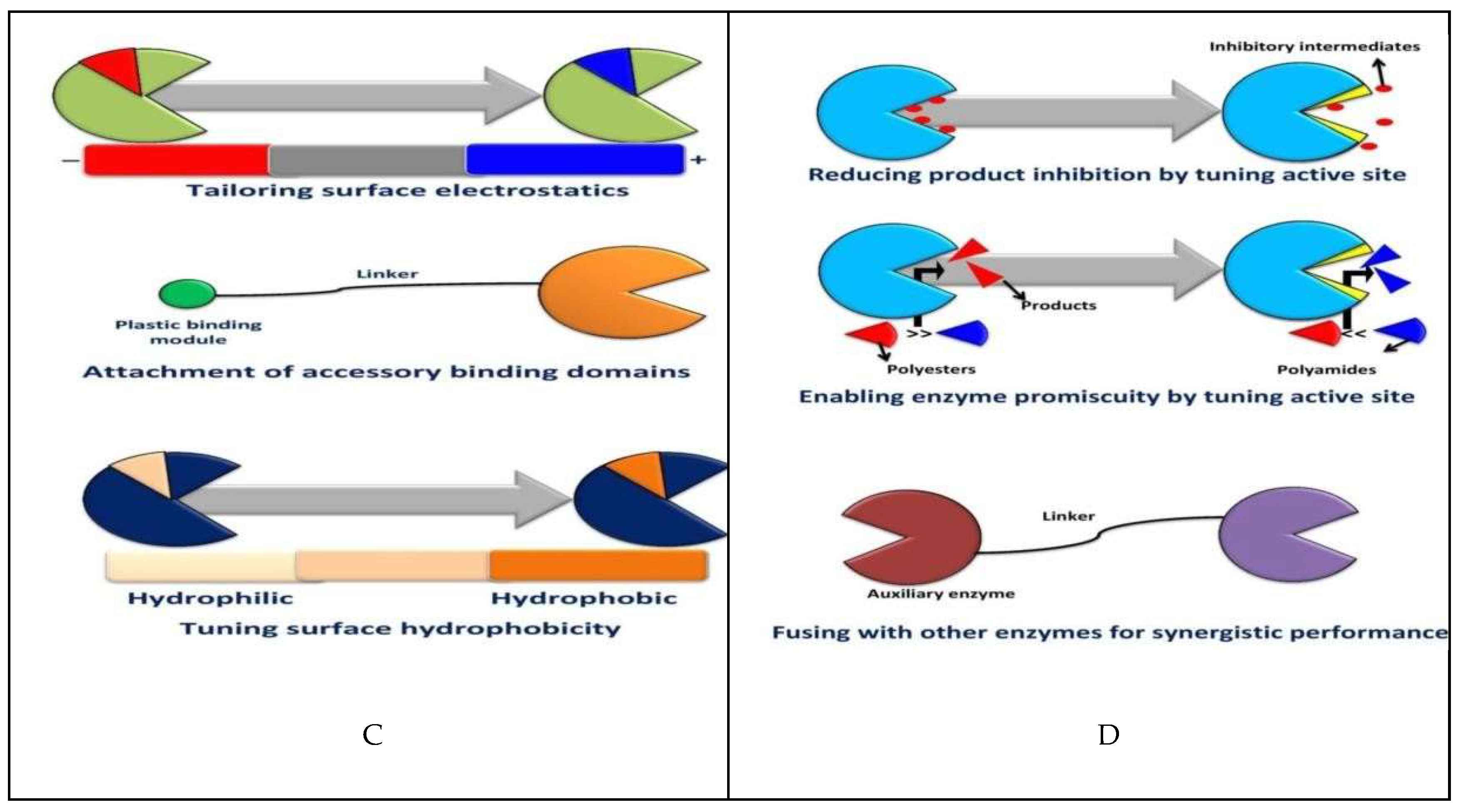

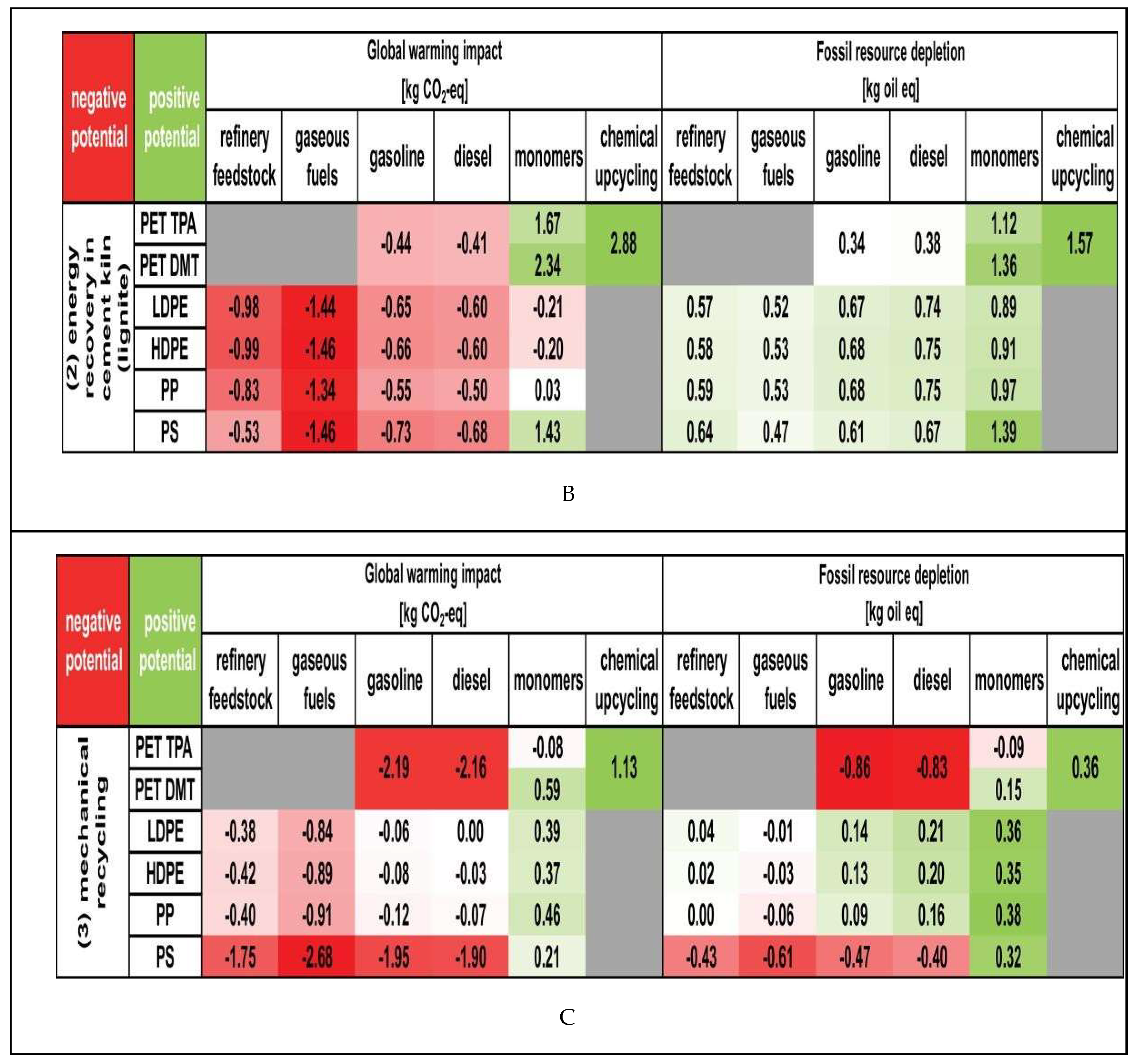

3. Economic Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment of Emerging Technologies

4. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- An, L.H.; Li, H.; Wang, F.F.; De ng, Y.X.; Xu, Q.J. Inte rnational Governance Progress in Marine Plastic Litter Pollution and Policy Re commendations. Re search of Environme ntal Sciences. 2022, 35, 1334–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Harussani, M.M.; Sapuan, S.M.; Rashid, U.; Khalina, A.; Ilyas, R.A. Pyrolysis of polypropylene plastic waste into carbonaceous char: Priority of plastic waste management amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Science of the Total Environme nt. 2022, 803, 149911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.M.; Robertson, M.L. The future of plastics recycling. Science. 2017, 358, 870–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorasan, C.; Edo, C.; Gonzále z-Pleiter, M.; Fernández-Piñas, F.; Leganés, F.; Rodrígue z, A.; Rosal, R. Ageing and fragme ntation of marine microplastics. Science of the Total Environme nt. 2022, 827, 154438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.C.; Bacha, A.U.R.; Yang, L. Control strategies for microplastic pollution in groundwater. Environme ntal Pollution. 2023, 335, 122323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, L.; Marcos, R.; Hernánde z, A. Pote ntial adverse health e ffects of ingeste d micro- and nanoplastics on humans. Lessons learne d from in vivo and in vitro mammalian models. Journal of Toxicology and Environme ntal Health, Part B. 2020, 23, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, B.G.; Takada, H.; Yamashita, R.; Okazaki, Y.; Uchida, K.; Tokai, T.; Tanaka, K.; Trenholm, N. PCBs and PBDEs in microplastic particles and zooplankton in open water in the Pacific Ocean and around the coast of Japan. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2020, 151, 110806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, J.H.; Zhang, W.; Shi, L.X.; Yi, K.X.; Yu, H.B.; Zhang, C.Y.; Li, S.Z.; Li, J.N. Microplastics as a ve hicle of heavy metals in aquatic environme nts: a review of adsorption fac tors, mechanisms, and biological e ffects. Journal of Environme ntal Manage ment. 2022, 302, 113995. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, X.T.; Niu, B.X.; Sun, H.W.; Zhou, X. Insight into response characteristics and inhibition mechanism of anammox granular sludge to polyethylene terephthalate microplastics exposure. Bioresource Technology. 2023, 385, 129355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Re ddy, S.; Barathe, P.; Oak, U.; Shriram, V.; Kharat, S.S.; Govarthanan, M.; Kumar, V. Microplastic-associate d pathogens and antimicrobial resistance in environme nt. Che mosphere. 2022, 291, 133005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikrishnan, T.; Janardhanam, M.; Sivakumar, P.; Sivakumar, R.; Rajamanickam, K.; Raman, T.; Thangave lu, M.; Muthusamy, G.; Singaram, G. Microplastic contamination in commercial fish species in southern coastal region of India. Chemosphere. 2023, 313, 137486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lü, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Shao, L.M.; Ye, J.F.; He, P.J. Is incineration the terminator of plastics and microplastics? Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2021, 401, 123429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.Q.; Pe ng, S.Z.; Pe ng, C.; Hu, Y.K. Re search progress in high value -added utilization technology of waste plastics. Che mical Industry and Engine ering Progress. 2023, 42, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Wang, S.; Yan, J.B.; Zhang, H.R.; Qiu, L.P.; Liu, W.J.; Guo, Y.; She n, J.; Chen, B.; Shi, C.; Ge, X. Revie w of waste plastics treatme nt and utilization: Efficie nt conversion and high value utilization. Process Safety and Environme ntal Protection. 2024, 183, 378–398. [Google Scholar]

- Su, K.Y.; Liu, H.F.; Zhang, C.F.; Wang, F. Photocatalytic conversion of waste plastics to low carbon number organic products. Chine se Journal of Catalysis. 2022, 43, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The w, C.X.E.; Lee, Z.S.; Srinophakun, P.; Ooi, C.W. Rece nt advances and challe nges in sustainable manageme nt of plastic waste using biodegradation approach. Bioresource Technology. 2023, 374, 128772. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.M.; Strong, G.; DaSilva, V.; Gao, L.J.; Huacuja, R.; Konstantinov, I.A.; Rose n, M.S.; Nett, A.J.; Ewart, S.; Geyer, R.; Scott, S.L.; Guironne t, D. Chemical Recycling of Polyethyle ne by Tandem Catalytic Conversionto Propyle ne. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2022, 144, 18526–18531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Re n, Y.; Li, Z.H.; Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Ge, R.X.; Kong, X.G.; Zhe ng, L.R.; Duan, H.H. Electrocatalytic upcycling of polyethyle neterephthalate to commodity chemicals and H2 fue l. Nature Communications. 2021, 12, 4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.Y.; Hu, W.Y.; Huang, W.W.; Wang, H.; Yan, S.H.; Yu, S.T.; Liu, F.S. Methanolysis of polycarbonate into valuable product bisphenol A using choline chloride -based deep eutectic solve nts as highly active catalys ts. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2020, 388, 124324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Chen, L.Y.; Je ng, R.J.; Dai, S.A. 100% Atom-Economy Efficie ncy of Recycling Polycarbonate into Versatile Inte rmediates. ACS Sustainable Che mistry & Engine ering. 2018, 6, 8964–8975. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Luo, H.; Shao, Z.L.; Zhou, H.Z.; Lu, J.W.; Che n, J.J.; Huang, C.J.; Zhang, S.N.; Liu, X.F.; Xia, L.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.H. Converting Plastic Wastes to Naphtha for Closing the Plastic Loop. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2023, 145, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, G.; Ke nne dy, R.M.; Hackler, R.A.; Ferrandon, M.; Te nnakoon, A.; Patnaik, S.; LaPointe, A.M.; Ammal, S.C.; Heyde n, A.; Perras, F.A.; Pruski, M.; Scott, S.L.; Poeppelme ier, K.R.; Sadow, A.D.; Delferro, M. Upcycling Single -Use Polyethyle ne into High-Quality Liquid Products. ACS Ce ntral Science. 2019, 5, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conk, R.J.; Hanna, S.; Shi, J.X.; Yang, J.; Ciccia, N.R.; Qi, L.; Bloomer, B.J.; He uvel, S.; Wills, T.; Su, J.; Bell, A.T.; Hartwig, J.F. Catalytic deconstruction of waste polyethylene withe thyle ne to form propyle ne. Science. 2022, 377, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Ze ng, M.H.; Yappert, R.D.; Sun, J.K.; Lee, Y.H.; LaPointe, A.M.; Peters, B.; Abu-Omar, M.M.; Scott, S.L. Polyethylene upcycling to long-chain alkylaromaticsby tandem hydrogenolysis/aromatization. Science. 2020, 370, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attique, S.; Batool, M.; Yaqub, M.; Goerke, O.; Gregory, D.H.; Shah, A.T. Highly e fficie nt catalytic pyrolysis of polyethylene waste to derive fue l products by novel polyoxometalate/kaolin composites. Waste Management & Re search. 2020, 38, 689–695. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, D.D.; Yang, H.P.; Hu, Q.; Che n, Y.Q.; Chen, H.P.; Williams, P.T. Carbon nanotubes from post-consumer waste plastics: Investigations intocatalyst metal and support material characteristics. Applied Catalysis B: Environme nt al. 2021, 280, 119413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Duan, D.L.; Lei, H.W.; Villota, E.; Ruan, R. Je t fue l production from waste plastics via catalytic pyrolysis with activated carbons. Applied Ene rgy. 2019, 251, 113337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, E.; Lei, H.W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Xin, L.Y.; Zhao, Y.F.; Qian, M.; Zhang, Q.F.; Lin, X.N.; Wang, C.X.; Mateo, W.; Villota, E.M.; Ruan, R. Jet fue l and hydroge n produced from waste plastics catalytic pyrolysiswith activated carbon and MgO. Scie nce of the Total Environme nt. 2020, 727, 138411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, N.; Li, X.Q.; Xia, S.W.; Sun, L.; Hu, J.H.; Bartocci, P.; Fantozzi, F.; Williams, P.T.; Yang, H.P.; Che n, H.P. Pyrolysis-catalysis of diffe re nt waste plastics over Fe/Al2O3 catalyst: High-value hydroge n, liquid fue ls, carbon nanotubes and possiblereaction mechanisms. Ene rgy Conversion and Management. 2021, 229, 113794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Sun, Y.K.; Guo, J.J.; Wang, S.; Yuan, J.P.; Esakkimuthu, S.; Uzoejinwa, B.B.; Yuan, C.; Abomohra, A.E.F.; Qian, L.L.; Liu, L.; Li, B.; He, Z.X.; Wang, Q. Synergistic e ffects of co-pyrolysis of macroalgae and polyvinyl chloride onbio-oil/bio-char properties and transferring regularity of chlorine. Fuel. 2019, 246, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akubo, K.; Nahil, M.A.; Williams, P.T. Aromatic Fuel Oils Produced from the Pyrolysis -Catalysis of Polyethyle ne Plastic with Metal-Impregnated Ze olite Catalysts. Journal of the Ene rgy Institute. 2019, 92, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer, I.; Je nks, M.J.F.; Gonzále z, R.M.; Meirer, F.; Weckhuyse n, B.M. Plastic Waste Conversion over a Re fine ry Waste Catalyst. Angewandte Che mie International Edition. 2021, 60, 16101–16108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.Z.; Cho, M.K.; Lee, J.G.; Choi, S.W.; Lee, K.B. Upcycling of Waste Polyethyle ne Te rephthalate Plastic Bottle s into Porous Carbon for CF4 Adsorption. Environmental Pollution. 2020, 265, 114868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.W.; Liu, B.G.; Rong, Q.; Zhang, L.B.; Guo, S.H. Porous carbon materials derived from discarded COVID-19 masks via microwave solvothermal method for lithium-sulfur batteries. Science of the Total Environme nt. 2022, 817, 152995. [Google Scholar]

- Munir, D.; Amer, H.; Aslam, R.; Bououdina, M.; Usman, M.R. Composite zeolite beta catalysts for catalytic hydrocracking of plastic waste to liquid fue ls. Materials for Re newable and Sustainable Ene rgy. 2020, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nakaji, Y.; Tamura, M.; Miyaoka, S.; Kumagai, S.; Tanji, M.; Nakagawa, Y.; Yoshioka, T.; Tomishige, K. Low-temperature catalytic upgrading of waste polyole finic plastics intoliquid fue ls and waxes. Applied Catalysis B: Environme ntal. 2021, 285, 119805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.T.; Bobbink, F.D.; van Muyden, A.P.; Lin, K.H.; Corminboe uf, C.; Zamani, R.R.; Dyson, P.J. Catalytic hydrocracking of synthe tic polymersinto grid-compatible gas streams. Cell Re ports Physical Science. 2021, 2, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.S.; Mahari, W.A.W.; Ok, Y.S.; Pe ng, W.X.; Chong, C.T.; Ma, N.L.; Chase, H.A.; Liew, Z.L; Yusup, S.; Kwon, E.E.; Tsang, D.C.W. Microwave vacuum pyrolysis of waste plastic and used cooking oil for simultaneous waste reduction and sustainable energy conversion: Recovery of cleaner liquid fue l and techno -economic analysis. Rene wable and Sustainable Energy Revie ws. 2019, 115, 109359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Q.; Che n, K.; Xie, W.; Liu, Y.Y.; Cao, M.J.; Kong, X.H.; Chu, Q.L.; Mao, H.P. Hydrocarbon rich bio-oil production, thermal behavior analysis and kine tic study of microwave-assiste d co-pyrolysis of microwave-torre fie d lignin with low density polyethyle ne. Bioresource Technology. 2019, 291, 121860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re x, P.; Msilamani, I.P.; Miranda, L.R. Microwave pyrolysis of polystyrene and polypropylene mixtures using diffe rent activated carbon from biomass. Journal of the Ene rgy Institute. 2020, 93, 1819–1832. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.; Dai, L.L.; Lv, Y.C.; Li, H.; De ng, W.Y.; Guo, F.Q.; Che n, P.; Lei, H.W.; Ruan, R. Catalytic pyrolysis of plastic wastes in a continuous microwave assistedpyrolysis system for fue l production. Che mical Engine ering Journal. 2021, 418, 129412. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.Q.; Bian, C.; Wang, G.Y.; Bai, B.; Xie, Y.P.; Jin, H. Co-gasification of plastic wastes and soda lignin in supercritical water. Che mical Engine ering Journal. 2020, 388, 124277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Liu, Y.G.; Wang, Q.X.; Zou, J.; Zhang, H.; Jin, H.; Li, X.W. Experime ntal investigation on gasification characteristics of plastic wastes in supercritical water. Re newable Ene rgy. 2019, 135, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Wang, W.Z.; Jin, H. Experime ntal study on gasification performance of polypropyle ne (PP) plastics in supercritical water. Ene rgy. 2020, 191, 116527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Hu, C.S.; Peng, B.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.W.; Wu, K.; Zhang, H.Y.; Xiao, R. High H2/CO ratio syngas production from chemical looping co-gasificationof biomass and polyethylene with CaO/Fe2O3 oxygen carrie r. Energy Conversion and Manage ment. 2019, 199, 111951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.C.; Zhe ng, K.; Che n, Q.X.; Li, X.D.; Li, Y.M.; Shao, W.W.; Xu, J.Q.; Zhu, J.F.; Pan, Y.; Sun, Y.F.; Xie, Y. Photocatalytic Conversion of Waste Plastics into C2 Fuels under Simulated Natural Environme nt Conditions. Ange wandte Chemie Inte rnational Edition. 2020, 59, 15497–15501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ze ng, M.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Strong, G.; LaPointe, A.M.; Kocen, A.L.; Qu, Z.Q.; Coates, G.W.; Scott, S.L.; Abu-Omar, M.M. Chemical Upcycling of Polyethyle ne to Value -Added α,ω-Divinyl-Functionalize d Oligomers. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 2021, 9, 13926–13936. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.T.; Wang, X.H.; Miller, J.B.; Huber, G.W. The Chemistry and Kine tics of Polyethyle ne Pyrolysis: A Process to Produce Fuels and Che micals. ChemSusChem. 2020, 13, 1764–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.; Farag, H.A.; Nassef, E.; Amer, A.; ElTaweel, Y. Pyrolysis of low-density polyethyle ne waste plastics using mixtures of catalysts. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management. 2020, 22, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Yang, X.X.; Fu, Z.W.; Li, R.; Wu, Y.L. Synergistic e ffect of catalytic co-pyrolysis of cellulose and polyethyle ne over HZSM-5. Journal of The rmal Analysis and Calorimetry. 2020, 140, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriapparao, D.V.; Vinu, R.; Shukla, A.; Haldar, S. Effe ctive Deoxygenation for the Production of Liquid Biofue ls via Microwave Assisted Co-pyrolysis of Agro Residues and Waste Plastics Combine d withCatalytic Upgradation. Bioresource Technology. 2020, 302, 122775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Y.S.; Park, K.B.; Kim, J.S. Hydrogen production from steam gasification of polyethylene using a two-stage gasifie r and active carbon. Applied Ene rgy. 2020, 262, 114495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.N.; He, C.Z.; Dong, J.; Li, N.; Xu, C.R.; Pan, X.C. Sunlight-Me diated Degradation of Polyethyle ne under the Syne rgy of Photothermal C–HActivation and Modification. Macromolecular Che mistry and Physics. 2022, 223, 2100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.C.; Tran, K.Q. A review on disposal and utilization of phytoreme diation plants containing heavy metals. Ecotoxicology and Environme ntal Safety. 2021, 226, 112821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Song, L.; Zhang, X.M.; Guo, Y.; Qian, F.J.; Dong, H.P. Re search Status and Prospect of Polycarbonate Chemical Depolymerization Technology. China Plastics Industry. 2023, 51, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Liu, M.J.; Zhou, H.; Su, B.G.; Yang, Y.W. Progress on catalytic cracking of waste polyole fin plastics to produce fue ls. Industrial Catalysis. 2022, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Susastriawan, A.A.P.; Purnomo; Sandria, A. Experimental study the influe nce of zeolite size on low-temperaturepyrolysis of low-density polyethyle ne plastic waste. The rmal Science and Engine ering Progress. 2020, 17, 100497. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Zhang, X.K.; Zhao, Z.G.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, K.G. Progress of research on chemical upcycling of plastic waste based on pyrolysis. Ene rgy and environmental protection. 2023, 37, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.V.; Kumar, S.; Sarker, M. Waste HD-PE Plastic Deformation into Liquid Hydrocarbons as Fuel by a Pyrolysis-Catalytic CrackingUsing the CuCO3 Catalyst. Sustainable Ene rgy & Fuels. 2018, 2, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.V. Waste and virgin high-de nsity poly(ethyle ne) into rene wable hydrocarbons fue l by pyrolysis -catalytic cracking with a CoCO3 catalyst. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 2018, 134, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, T.R.; Jin, M.Y.; Lu, X.R.; Liu, T.; Vahabi, H.; Gu, Z.P.; Gong, X. Functional carbon dots derived from biomass and plastic wastes. Green Chemistry. 2023, 25, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.F.; Zhong, L.Q.; Gong, X. Robust Superhydrophobic Films Based on an Eco-Frie ndly Poly(L-lactic acid)/Ce llulose Composite with Controllable Water Adhe sion. Langmuir. 2024, 40, 10362–10373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, B.W.; Chen, X.; Ling, Y.; Niu, T.T.; Guan, W.X.; Meng, J.P.; Hu, H.Q.; Tsang, C.W.; Liang, C.H. Hydrogenolysis -Isomerization of Waste Polyole fin Plasticsto Multibranched Liquid Alkanes. ChemSusChe. 2023, 16, e 202202035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.C.; Wang, L.A.; Xu, T.T.; Deng, X.J.; Zhang, H.L. Re search on the e ffect of Na 2S2O3 on mercury transfer ability of two plant species. Ecological Engine ering. 2014, 73, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.C.; Wang, L.A.; Zeng, F.T.; Al-Hamadani, S.M.Z.F. The Absorption and Enrichme nt Condition of Mercury by Three Plant Species. Polish Journal of Environme ntal Studies. 2015, 24, 887–891. [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.Y.; Zhang, X.R.; Liu, J.F.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wu, L.Y.; Bai, X.J.; Tan, C.H.; Gong, Y.W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Li, H.Y. Establishment of evaluation system for biological remediation on organic pollution in groundwater using slow-re lease age nts. Science of the Total Environme nt. 2023, 903, 166522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.P.; Xing, J.M. Progress in biodegradation and upcycling of polyethyle ne terephthalate (PET). Chinese Journal of Bioprocess Engine ering. 2022, 20, 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Rambabu, K.; Bharath, G.; Govarthanan, M.; Kumar, P.S.; Show, P.L.; Banat, F. Bioprocessing of plastics for sustainable environme nt: Progress, challe nges, and prospects. Trends in Analytical Che mistry. 2023, 166, 117189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.G.; Yu, Z.F.; Du, Y.M.; Wang, X.C.; Wang, C.H. Sustainable one-pot synthesis of novel soluble cellulose-based nonionic biopolymers for natural antimicrobial materials. Chemical Engine ering Journal. 2023, 468, 143810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.G.; Yu, Z.F.; Wang, X.C.; Li, N. Eco-Frie ndly Cellulose-Based Nonionic Antimicrobial Polymers with Excelle nt Biocompatibility, Nonle achability, and Polymer Miscibility. ACS Applied Materials & Inte rfaces. 2023, 15, 50344–50359. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, X.G.; Fu, Y.T.; Wang, X.C. Versatile Biomass-Based Injectable Photothermal Hydrogel for Integrate d Regenerative Wound Healing and Skin Bioe lectronics. Advanced Functional Materials. 2024, 2405745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Wang, X.C.; Hao, D.Y.; Xie, L.; Yang, J.; Dang, X.G. Polysaccharides for sustainable leather production: A review. Environme ntal Che mistry Letters. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, A.; Bukhari, D.A.; Shamim, S.; Rehman, A. Plastics degradation by microbes: A sustainable approach. Journal of King Saud Unive rsity – Science. 2021, 336, 101538. [Google Scholar]

- Bahl, S.; Dolma, J.; Singh, J.J.; Se hgal, S. Biodegradation of plastics: A state of the art revie w. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2021, 39, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanek, A.K.; Kosiorowska, K.E.; Miro_nczuk, A.M. Curre nt knowledge on polyethyle ne terephthalate degradation by ge ne tically modifie d microorganisms. Frontiers in Bioe ngine ering and Biotechnology. 2021, 9, 771133. [Google Scholar]

- Veluru, S.; Seeram, R. Biotechnological approaches: Degradation and valorization of waste plastic to promote the circular economy. Circular Economy. 2024, 3, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- We i, R.; Breite, D.; Song, C.; Gräsing, D.; Ploss, T.; Hille, P.; Schwe rdtfeger, R.; Matysik, J.; Schulze, A.; Zimmermann, W. ; Biocatalytic Degradation Efficie ncy of PostconsumerPolyethyle ne Terephthalate Packaging Determine dby The ir Polymer Microstructures. Advanced Science. 2019, 6, 1900491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowska, G.B.; Tylman-Mojżeszek, W.; Mierek-Adamska, A.; Riche rt, A.; Hrynkie wicz, K. Pote ntial of Serratia plymuthica IV-11-34 strain for biodegradation of polylactide and poly(ethyle ne terephthalate ). Inte rnational Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2021, 193, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollinge r, A.; Thie s, S.; Knie ps-Grünhage n, E.; Gertze n, C.; Kobus, S.; Höppner, A.; Ferrer, M.; Gohlke, H.; Smits, S.H.J.; Jaege r, K.E. A Novel Polyester Hydrolase From the Marine Bacterium Pseudomonas aestusnigri - Structural and Functional Insights. Frontie rs in Microbiology. 2020, 11, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Che n, Z.Z.; Wang, Y.Y.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Wang, X.; Tong, S.W.; Yang, H.T.; Wang, Z.F. Efficie nt biodegradation of highly crystallize d polyethylene terephthalate through cell surface display of bacterial PETase. Scie nce of the Total Environme nt. 2020, 709, 136138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Maitra, S.S.; Singh, R.; Burwal, D.K. Acclimatization of a newly isolated bacteria in monomer tere -phthalic acid (TPA) mayenable it to attack the polymer poly-ethyle ne tere-phthalate (PET). Journal of Environme ntal Chemical Engineering. 2020, 8, 103977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabloune, R.; Khalil, M.; Moussa, I.E.B.; Simao-Beaunoir, A.; Lerat, S.; Brze zinski, R.; Beaulieu, C. Enzymatic Degradation of p-Nitrophe nyl Esters, Polyethyle ne Te rephthalate,Cutin, and Suberin by Sub1, a Suberinase Encoded by the Plant Pathogen Streptomyces scabies. Microbes and Environme nts. 2020, 35, ME19086. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, F.; We i, R.; Cui, Q.; Bornscheuer, U.T.; Liu, Y.J. The rmophilic whole-cell degradation of polyethyle ne terephthalate using e ngine ered Clostridium thermocellum. Microbial Biotechnology. 2021, 14, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzi, A.; De hnad, A.; Fotouhi, A.F. Biocatalysis and agricultural biotechnology biodegradation of polyethylene terephthalate waste using Streptomyces species and kine tic modeling of the process. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology. 2019, 17, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moog, D.; Schmitt, J.; Senger, J.; Zarzycki, J.; Re xer, K.H.; Linne, U.; Erb, T.; Maier, U.G. Using a marine microalga as a chassis for polyethyle ne terephthalate (PET) degradation. Microbial Cell Factories. 2019, 18, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournie r, V.; Topham, C.M.; Gilles, A.; David, B.; Folgoas, C.; Moya-Leclair, E.; Kamionka, E.; Desrousseaux, M.L.; Texier, H.; Gavalda, S.; Cot, M.; Guémard, E.; Dalibey, M.; Nomme, J.; Cioci, G.; Barbe, S.; Chateau, M.; André, I.; Duquesne, S.; Marty, A. An e ngine ered PET depolymerase to bre ak down and recycle plastic bottles. Nature. 2020, 580, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.X.; Ni, K.F.; Hao, H.L.; Shang, Y.P.; Zhao, B.; Qian, Z. Secretory expression in Bacillus subtilis and biochemical characterization of a highly thermostable polyethyle ne terephthalate hydrolase from bacterium HR29. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2021, 143, 109715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomucci, L.; Raddadi, N.; Soccio, M.; Lotti, N.; Fava, F. Polyvinyl chloride biodegradation by Pseudomonas citronellolis and Bacillus flexus. New Biotechnology. 2019, 52, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivi, V.K.; Martins-Franchetti, S.M.; Attili-Ange lis, D. Biodegradation of PCL and PVC: Chaetomium globosum (ATCC 16021) activity. Folia Microbiologica. 2019, 64, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomucci, L.; Raddadi, N.; Soccio, M.; Lotti, N.; Fava, F. Biodegradation of polyvinyl chloride plastic films by e nriche d anae robic marine consortia. Marine Environmental Re search. 2020, 158, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, T.A.; Barbosa, R.; Mesquita, A.B.S.; Ferreira, J.H.L.; de Carvalho, L.H.; Alves, T.S. Fungal degradation of reprocessed PP/PBAT/the rmoplastic starch blends. Journal of Materials Research and Technology. 2020, 9, 2338–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Gao, D.L.; Li, Q.H.; Zhao, Y.X.; Li, L.; Lin, H.F.; Bi, Q.R.; Zhao, Y.C. Biodegradation of polyethyle ne microplastic particles by the fungus Aspergillus flavus from the guts of wax moth Galleria mellonella. Scie nce of the Total Environme nt. 2020, 704, 135931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandare, S.D.; Chaudhary, D.R.; Jha, B. Marine bacterial biodegradation of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) plastic. Biodegradation. 2021, 32, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spina, F.; Tummino, M.L.; Poli, A.; Prigione, V.; Ilieva, V.; Cocconcelli, P.; Puglisi, E.; Bracco, P.; Zanetti, M.; Varese, G.C. ; Low density polyethyle ne degradation by filame ntous fungi. Environme ntal Pollution. 2021, 274, 116548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanniyasi, E.; Gopal, R.K.; Gunase kar, D.K.; Raj, P.P. Biodegradation of low-density polyethyle ne (LDPE) sheet by microalga, Uronema africanum Borge. Scie ntific Re ports. 2021, 11, 17233. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A.S.; Bose, H.; Mohapatra, B.; Sar, P. Biodegradation of Unpre treated Low-Density Polyethyle ne (LDPE) by Stenotrophomonas sp. and Achromobacter sp. Isolated From Waste Dumpsite and Drilling Fluid. Frontie rs in Microbiology. 2020, 11, 603210. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, R.S.; Ramya, R.; Kannan, K.; Antony, A.R.; Kannan, V.R. Investigation of biodegradation pote ntials of high-de nsity polyethylene degrading marine bacteria isolate d from the coastal regions of Tamil Nadu, India. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2019, 138, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Kim, C.G. Biodegradation of micro-polyethylene particles by bacterial colonization of a mixed microbial consortium isolated from a landfill site. Che mosphere. 2019, 222, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.N.; We i, M.; Han, F.; Fang, C.; Wang, D.; Zhong, Y.J.; Guo, C.L.; Shi, X.Y.; Xie, Z.K.; Li, F.M. Greater Biofilm Formation and Increased Biodegradation of Polyethyle ne Film by a Microbial Consortium of Arthrobacter sp. and Streptomyces sp. Microorganisms. 2020, 8, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsamahy, T.; Sun, J.Z.; Elsilk, S.E.; Ali, S.S. Biodegradation of low-density polyethylene plastic waste by a constructed tri-culture yeast consortium from wood-fee ding termite: Degradation mechanism and pathway. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2023, 448, 130944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarke r, R.K.; Chakraborty, P.; Paul, P.; Chatterjee, A.; Tribedi, P. Degradation of low-density poly ethyle ne (LDPE) by Enterobacter cloacae AKS7: a pote ntial step towards sustainable environme ntal remediation. Archives of Microbiology. 2020, 2028, 2117–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazer, Z.; Najafi, M.B.H.; Levin, D.B. Microbial degradation of low-density polyethyle ne and synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate polymers. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 2019, 653, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skariyachan, S.; Taskee n, N.; Kishore, A.P.; Krishna, B.V.; Naidu, G. Novel consortia of Enterobacter and Pseudomonas formulated from cow dung exhibite d e nhance d biodegradation of polyethyle ne and polypropyle ne. Journal of Environme ntal Manage ment. 2021, 284, 112030. [Google Scholar]

- Delacuvelle rie, A.; Cyriaque, V.; Gobert, S.; Benali, S.; Wattie z, R. The plastisphere in marine ecosystem hosts pote ntial specific microbial degraders including Alcanivorax borkumensis as a ke y playe r for the low-density polyethyle ne degradation. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2019, 380, 120899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, A.; Chaudhary, D.R.; Jha, B. Destabilization of polyethylene and polyvinylchloride structure by marine bacterial strain. Environme ntal Science and Pollution Re se arch International. 2019, 26, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoironi, A.; Anggoro, S. ; Sudarno, Evaluation of the Inte raction Among Microalgae Spirulina sp, Plastics Polyethylene Terephthalate and Polypropyle ne in Freshwater Environment. Journal of Ecological Engine ering. 2019, 206, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong-Johnson, E.Z.L.; Voigt, C.A.; Sinske y, A.J. An absorbance method for analysis of e nzymatic degradation kine tics of poly(e thyle ne terephthalate) films. Scientific Re ports. 2021, 11, 928. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.L.; Che n, Y.C.; Liu, X.Y.; Dong, S.J.; Tian, Y.E.; Qiao, Y.X.; Mitra, R.; Han, J.; Li, C.L.; Han, X.; Liu, W.D.; Che n, Q.; We i, W.Q.; Wang, X.; Du, W.B.; Tang, S.Y.; Xiang, H.; Liu, H.Y.; Liang, Y.; Houk, K.N.; Wu, B. Computational Redesign of a PETase for Plastic Biodegradation under Ambie nt Condition by the GRAPE Strategy. ACS Catalysis. 2021, 11, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.T.; Wang, D.; We i, N. Enzyme Discovery and Enginee ring for Sustainable Plastic Recycling. Trends in Biotechnology. 2022, 40, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.K.; Lee, S.H.; Park, H.D. Curre nt biotechnologies on depolymerization of polyethyle ne terephthalate (PET) and repolymerization of reclaimed monomers from PET for bio-upcycling: A critical revie w. Bioresource Technology. 2022, 363, 127931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Song, Y.Y.; Wang, X.; Me ng, Q.Q.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, L.P.; Wu, S.K. Hydrogen production from organic solid waste by the rmochemical conversion process: a review. Che mical Industry and Engine ering Progress. 2021, 40, 709–721. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, V.; Parashar, A.; Shastri, Y.; Bhattacharya, S. Techno-Economic and Life Cycle Assessment of Pyrolysis of Unsegregated Urban Municipal Solid Waste in India. Industrial & Engine ering Che mistry Re search. 2021, 60, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.J.; Boit, M.O.K.; Wu, K.; Jain, P.; Liu, E.J.; Hsieh, Y.F.; Zhou, Q.; Li, B.W.; Hung, H.C.; Jiang, S.Y. Zwitterionic carboxybetaine polymers extend the shelf-life of humanplatelets. Acta Biomaterialia. 2020, 109, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, X.G.; Yu, Z.F.; Yang, M.; Woo, M.W.; Song, Y.Q.; Wang, X.C.; Zhang, H.J. Sustainable e lectrochemical synthesis of natural starch-based biomass adsorbe nt with ultrahigh adsorption capacity for Cr(VI) and dyes removal. Separation and Purification Technology. 2022, 288, 120668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.J.; Tsao, C.T.; Kyomoto, M.; Zhang, M.Q. Injectable Natural Polymer Hydrogels for Treatment of Knee Osteoa rthritis. Advanced Healthcare Materials. 2022, 11, 2101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.C. A revie w on the emerging conversion technology of cellulose, starch, lignin, protein and other organics from vegetable-fruit-based waste. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023, 242, 124804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.H. Plastic waste as pyrolysis feedstock for plastic oil production: A revie w. Scie nce of the Total Environme nt. 2023, 877, 162719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluth, A.; Xu, Z.; Fifie ld, L.S.; Yang, B. Advancing biological processing for valorization of plastic wastes. Renewable and Sustainable Ene rgy Re views. 2022, 170, 112966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Liu, H.X.; Che ng, Z.J.; Cheng, B.B.; Che n, G.Y.; Wang, S.B. Conversion of plastic waste into fue ls: A critical review. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2022, 424, 127460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meys, R.; Frick, F.; Westhues, S.; Sternberg, A.; Klanke rmaye r, J.; Bardow, A. Towards a circular economy for plastic packaging wastes – the environmental pote ntial of che mical recycling. Resources, Conservation & Re cycling. 2020, 162, 105010. [Google Scholar]

|

Plastic waste |

Device |

Reactant |

Catalyst |

Temperature |

Reaction medium |

Illumination |

Product |

Reference |

|

|

PE PET PC PC PE PE PE PE PE Plastic mixture Plastic mixture |

Tank reactor Electrolyzer Autoclave Reaction vessel Autoclave Autoclave Reaction vessel Autoclave Furnace Fixed bed reactor Tube reactor |

C2H4 H2O Methanol C6HN, C8HN2O2 / / C2H4 / / / / |

Pt/γ-Al2O3, MTO/Cl−Al2O3 Electrocatalyst ChCl-2Urea Stannous octoate Pt@S-1 Pt/SrTiO3 Ir-tBuPOCOP, [PdP(tBu)3(m-Br)]2 Pt/γ-Al2O3 KAB/kaolin composites Four Ni-Fe catalysts Activated carbon |

100 °C 60 °C 130 °C 70-75 °C 250 °C 300 °C 130-350 °C 280 °C 295 °C 500 °C 430-571 °C |

Atmospheric C2H4 KOH aqueous solution Autogenous pressure Anisole 3 MPa of H2 170 Pa of H2 / / N2 N2 N2 |

/ / / / / / / / / / / |

Propylene Potassium diformate, terephthalic acid, H2 Bisphenol A PU Naphtha hydrocarbons Fuel oil Propylene Alkylaromatics, alkylnaphthenes Fuel oil, syngas Carbon nanotubes Jet fuel, H2-enriched gases |

[17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] |

|

| Low-density PE PP PE PS PVC High-density PE PP PET Medical masks Plastic mixture Low-density PE Plastic mixture Plastic mixture Low-density PE |

Fixed bed reactor Fixed bed reactor Fixed bed reactor Fixed bed reactor Fixed bed reactor Fixed bed reactor Autoclave Horizontal furnace Tube furnace Autoclave Autoclave Autoclave Microwave oven Microwave oven |

/ / / / EC / / / / / / / Cooking oil Lignin |

Activated carbon, MgO Fe/Al2O3 Fe/Al2O3 Fe/Al2O3 / Y-zeolite with transition metals Waste refinery catalyst / / Zeolite beta composite CeO2-supported Ru Ru-modified zeolite / / |

450-600 °C 500 °C 500 °C 500 °C 550 °C 600 °C 100-450 °C 600-1000 °C 900 °C 360-400 °C 200 °C 300 °C 400-550 °C 550 °C |

N2 N2 N2 N2 N2 N2 / N2 Ar 20 bar of H2 2 MPa of of H2 50 bar of H2 Negative pressure N2 |

/ / / / / / / / / / / / / / |

Jet fuel, H2-enriched gases H2, liquid fuels, carbon nanotubes H2, liquid fuels, carbon nanotubes H2, liquid fuels, carbon nanotubes Bio-oil, bio-char, non-condensable gas Aromatic fuel oils, H2 Methylbenzenes, alkanes Porous carbon Porous carbon materials Gasoline Liquid fuels, waxes CH4 Liquid fuel Hydrocarbon rich bio-oil |

[28] [29] [29] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] |

|

| Plastic mixture PE, PP PE, PC, PP, ABS PS PP PE Plastic mixture PE PE Low-density PE PE |

Microwave oven Microwave oven Autoclave Tube reactor Tube reactor Fixed bed reactor Reaction vessel Autoclave Fluidized-bed reactor Autoclave Pyrolyzer |

/ / Soda lignin / / Pine wood / Br2, ethylene / / Cellulose |

/ ZSM-5 / / Seawater CaO/Fe2O3 oxygen carrier Nb2O5 Grubbs Catalyst M202 / CB, kaoline, silica gel, activated charcoal HZSM-5 zeolite |

450-500 °C 500-740 °C 500-750 °C 500-800 °C 500-800 °C 750-850 °C RT 30-105 °C 500-600 °C 550-650 °C 650 °C |

/ / Supercritical water Supercritical water Supercritical water N2 / 2.7 bar of ethylene N2 / N2 |

/ / / / / / Sunlight 400−410 nm UV / / / |

Fuel oil Fuel oil Syngas H2, CH4, CO2 H2, CH4, CO2 Syngas with high H2/CO ratio C2 fuels α,ω-divinyl-functionalized oligomer H2, C1–C4 paraffins, C2–C4 olefins, 1,3-butadiene, C4–C60 n-paraffins, isoparaffins, mono-olefins, cycloalkanes/alkadienes, aromatics Parafns, isoparafns, olefns, naphthenes, aromatics, char, syngas Oxygenated chemicals, olefins, |

[40] [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] [50] |

|

|

PP, PS PE PE |

Microwave oven Fluidized bed gasifier, tar-cracking reactor Reaction vessel |

Rice straw, sugarcane bagasse / DIAD |

HZSM-5 Active carbon TBADT |

500 °C 790-840 °C 110 °C |

N2 Air or oxygen / |

/ / Sunlight |

alkanes, and aromatics Bio-oil, biochar, gas Syngas, tar Low molecular weight PE with tunable polarity |

[51] [52] [53] |

|

|

Plastic waste |

Microorganism / Enzyme |

Reaction condition |

Product |

Reference |

|

PET PET PET PET PET PET PET PET PET PET PET |

Thermobifida fusca / Cutinase (TfCut2) Serratia plymuthica strain IV-11-34 / Synthase Pseudomonas aestusnigri / Carboxylic ester hydrolase Pichia pastoris / PETase Rhococcus sp. SSM1 / PETase Streptomyces scabies / Protein Sub1 Clostridium thermocellum / thermophilic cutinase Streptomyces sp. Phaeodactylum tricornutum / PETase LCC – ICCG variant / Depolymerase Bacillus subtilis HR29 / BhrPETase |

1000 r/min, 70 °C, 96 h 26 °C, 30 d 30 °C, 48 h 30 °C, 18 h 34 °C, pH 8.5 37 °C, 20 d Anaerobically, 60 °C, 14 d 120 rpm, 28 °C, 18 d 21-30 °C, 180 d 65°C, 14 h, pH 8 37 °C, pH 7 |

Ethylene glycol, terephthalic acid Small molecules Bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate, mono(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate Small molecules Small molecules Terephthalic acid Small molecules Small molecules Terephthalic acid, mono(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalic acid Small molecules Small molecules |

[77] [78] [79] [80] [81] [82] [83] [84] [85] [86] [87] |

| PVC PVC PVC PP PE PE PE PE PE PE PE PE PE PE |

Pseudomonas citronellolis, Bacillus flexus Chaetomium globosum Anaerobic marine consortia Aspergillus sp., Penicillium sp. Aspergillus flavus / AFLA_006190, AFLA_053930 Cobetia sp., Halomonas sp., Exiguobacterium sp., Alcanivorax sp. Aspergillus flavus, Fusarium falciforme, Fusarium oxysporum, Purpureocillium lilacinum Uronema africanum Borge Stenotrophomonas sp., Achromobacter sp. / Cutinase, lipase, esterase, alkane monooxygenase Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas spp. Paenibacillus sp., Bacillus sp. Arthrobacter sp., Streptomyces sp. Sterigmatomyces halophilus, Meyerozyma guilliermondii, Meyerozyma caribbica / MnP, Lac, LiP |

Aerobically, 30 d 28 °C, 28 d Anaerobically, 20 °C, 2 a 29 °C, 30 d 28 d 30-90 d 30 d 30 d Aerobically, 150 rpm, 30 °C, 45 d 30 °C, 30 d 30 °C, 60 d 120 r/min, 25 °C, 90 d 30 °C, 45 d 30 °C, 45 d |

Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules |

[88] [89] [90] [91] [92] [93] [94] [95] [96] [97] [98] [99] [100] [101] |

| PE PE, PP PE, PET PE, PVC PP, PET |

Enterobacter cloacae AKS7 PE-degrading bacteria, PHA-synthesizing bacteria Enterobacter, Pseudomonas Alcanivorax, Marinobacter, Arenibacter Bacillus spp. Spirulina sp. |

30 °C, 21 d 37 °C, 160 d 30 °C, 80 d 180 rpm, 30 °C, 90 d 112 d |

Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules Small molecules |

[102] [103] [104] [105] [106] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).