1. Introduction

Tendinopathy accounts for up to 30% of all overuse injuries [

1,

2,

3,

4], contributing to the need for 30 million sports medicine surgeries annually worldwide [

5,

6]. The rotator cuff consisting of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis, which locates around the humeral head, plays a key role in the stability, movement, and sensory motor control of the glenohumeral joint [

7]. Rotator cuff tendinopathy (RCT) is the most common condition within the disease spectrum, with its terminal stage manifested by tendon tears [

8]. It gives rise to 80% of all cases of shoulder pain [

9] and is among the most common reasons for upper extremity weakness during shoulder external rotation and elevation [

10,

11,

12]. The lack of clarity regarding the complex nature of RCT undermines effective prevention and treatment, leading to a significant decrease in patients' quality of life [

13] and imposing a substantial socio-economic burden [

14].

Neuropsychiatric disorders (ND) encompass a broad range of diseases that undermines brain function, behavior, and cognition [

15], with onset occurring from early childhood to late adulthood [

16,

17,

18,

1920,

21,

22]. The rising worldwide prevalence of ND contributes to a sobering health burden and mortality among billions of people in the global population [

23,

24]; moreover, epidemiological studies have revealed a potential correlation between ND and tendinopathy. Systematic reviews suggested that the glutaminergic and sympathetic nervous systems, along with increased nerve ingrowth, indicate that neurogenic inflammation plays a strong role in tendinopathic tissue [

25]. Self-reported psychological factors related to emotion, cognition, and behavior have also been found to be associated with poor clinical outcomes in tendinopathy of any duration, affecting both the upper and lower limb tendons [

26]. Furthermore, it has been shown that depression, anxiety, distress, catastrophization, and kinesiophobia are linked to pain and disability levels in tendinopathy patients [

27]. In preoperative rotator cuff patients, worse pain catastrophizing and symptoms of depression or anxiety were related to poorer postoperative rotator cuff scores [

28,

29,

30]. However, the neuropsychiatric state has been overlooked by most tendon researchers [

31]. Currently, the identification of associations between ND and RCT is significantly hindered by confounders, limited sample sizes, and short follow-up times, which complicate the interpretation of findings from traditional observational studies. Furthermore, reverse causation, where chronic pain and incapacity exacerbate neuropsychiatric symptoms, complicates the interpretation of these findings [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Thus, any causal effects of ND in determining RCT risk remain a mystery.

Mendelian randomization (MR) leverages genetic variants of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to answer causal questions between exposure and outcomes [

36,

37]. Compared to traditional case-control or cross-sectional methodology, this approach can reveal genotype traits inherited by offspring independent of lifestyle or environmental factors according to the randomized allocation of individual genes [

38]. Therefore, MR enables the inference of causal effects while minimizing unobserved confounding factors and reverse causation based on Mendel’s inheritance laws and instrumental variables (IV) estimation [

39]. IV associated with eight predominant types of ND including attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), bipolar disorder (BD), epilepsy, major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and schizophrenia (SCZ), have been revealed by Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [

40]. In addition to the predominant disease, other mediators consisting of cigarette consumption, household income, educational attainment, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, grip strength, physical activity, and sedentary behavior at work are also taken into analyses to unmask the potential causal relationship between ND and RCT, which could not be fulfilled by traditional study methodology [

41].

A clearer understanding of the potential causal relationship between ND and RCT could be gained by utilizing a two-sample MR method, which includes both bidirectional univariable Mendelian randomization (UVMR) and multivariable Mendelian randomization (MVMR). If an evidence-based causal link is established, it would necessitate adoption of more integrated prevention and treatment strategies addressing neuropsychiatric health, exercise safety, clinical intervention, and physical rehabilitation simultaneously for ND patients at high genetic risk of developing RCT or who have already suffered from RCT. This study aims to elucidate the extent to which ND contributes to the risk of developing RCT, which could shed new light on underlying genetic loci and biological mechanisms to guide future research into targeted therapies for preventing or managing RCT in individuals with neuropsychiatric conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

To investigate the relationship between main types of ND (ADHD, ASD, BD, epilepsy, MDD, OCD, and SCZ included) and RCT in European ancestry population, we conducted bidirectional and multivariable two-sample MR with open access GWAS summary statistics (

Figure 1). This study was performed adhering to the STROBE-MR guidelines for reporting observational studies using MR methodology [

42].

2.2. Collection of GWAS Results

2.2.1. Collection of GWAS Results of ND and RCT

GWAS summary statistics for ASD, ADHD, BD, OCD, and SCZ were acquired from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) repository (

https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downloads/), with the following datasets: ASD from iPSYCH-PGC_ASD_Nov2017.gz (

https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downloads), ADHD from ADHD2022_iPSYCH_deCODE_PGC.meta.gz (

https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downloads), BD from daner_PGC_BIP32b_mds7a_0416a.gz (

https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downloads), OCD from PGC_OCD_Aug2017-20171122T182645Z-001.zip > ocd_aug2017.gz (

https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downloads), and SCZ from ckqny.scz2snpres.gz (

https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downloads). MDD-associated datasets were retrieved from a dedicated online repository hosted by the University of Edinburgh (

https://doi.org/10.7488/ds/2458) [

43]. As for epilepsy, the related GWAS datasets were sourced from the Epilepsy Genetic Association Database (epiGAD) (

https://www.epigad.org/gwas_index.html). Notably, the comprehensive meta-analysis GWAS for MDD, incorporating data from 23andMe, was not available for public usage to date. Therefore, we included the meta-analysis that integrated results from the PCG and UK Biobank (UKB) cohorts. RCT summary data was obtained from the FinnGen Biobank Analysis Consortium database (Release 12,

https://finngen.gitbook.io/documentation/) with diagnosis according to International Classification of Diseases - 10 (ICD-10) criteria. A total of 390,666 participants from European ancestry, including 33,117 cases and 357,549 controls, were encompassed in this study.

2.2.2. Collection of GWAS Results of potential confounders

Potential confounding factors were selected based on clinical practice and literature study. The potential confounders GWAS dataset is mainly publicly available from the Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) Open GWAS database (

https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/) as GWAS-IDs of ‘ieu-b-40’ for serum BMI, ‘ieu-a-61’ for WC, ‘ieu-b-142’ for smoking, ‘ukb-b-7408’ for income, and ‘ukb-b-10215’ for hand grip strength. Physical activity, including sedentary behavior and moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), was from the largest European ancestry meta-analysis (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/downloads/summary-statistics, GCP ID: GCP000358) [

44]. 74 genome-wide significant loci were conclusively identified to be associated with the number of years of schooling completed in a population of 405072 Europeans [

45].

2.3. Genetic instrument selection

MR analysis requires three assumptions to demonstrate causal effects. First, the relevance assumption states that the instrument should be strongly linked to the specific exposure phenotype; we utilized genetic variants concluded by GWAS to achieve this assumption. Second, the independence assumption requires that the instrument is not associated with confounders; we performed pleiotropy-robust MR sensitivity analysis to provide causal estimates while relaxing this assumption. We also conducted MVMR analysis to evaluate SNPs potentially associated with confounders. Third, the exclusion restriction assumption posits that causal effects should occur solely through the exposure trait, which cannot be directly tested. Therefore, median-based MR was implemented in analyses to mitigate potential violations of this assumption. This method allows for a more robust sensitivity analysis by relaxing the assumption for certain instruments [

46].

For these MR methods, SNPs show genome-wide significance (p ≤ 5 × 10−8) within a 1-Mbp and r2 < 0.001 of the exposure trait as instrumental variables. Resulting from this threshold, a limited number of IV (n < 3) were identified, prompting the adoption of a more liberal threshold of p < 5 × 10−6. F-statistics for each instrument were estimated by:

F = [(N-k-1)/k]*[R2/(1-R2)] (n: sample size; k: number of IV, R2: exposure variance explained by selected IV generated by MR Steiger directionality test).

F < 10 was regarded as insufficiently informative for further analysis [

47]; and the Steiger filtering test was also performed to avoid the reverse causality [

48].

2.4. Statistical analysis

In bidirectional two-sample MR, the inverse variance weighted (IVW) method was the primary analysis to evaluate the causal association. To validate the primary results, we employed supplementary MR-Egger, weighted median, and weighted model methods. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess SNPs heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy in the MR analyses. Heterogeneity was evaluated by Cochran’s Q test with the IVW and the MR-Egger method. No heterogeneity significance is indicated by

p > 0.05. MR-Egger intercept tests were conducted to estimate horizontal pleiotropy in the MR analyses. These tests are crucial as they help identify whether genetic variants affect multiple traits, which could bias causal estimates. A

p > 0.05 in the MR-Egger intercept test indicated no significant horizontal pleiotropy, suggesting that the target trait is primarily affected by genetic variants. Causal analysis using summary effect estimates (CAUSE) was employed for verification of potential horizontal pleiotropy. Two models were used to assess whether the genetic variants studied influence only the target trait (causal model) or if they also influence related traits (shared model). Based on which model fits the data, conclusions were drawn about the presence or absence of horizontal pleiotropy (i.e., the effect of a genetic variant on multiple traits) and whether those effects are related or unrelated [

49].

We performed MVMR to estimate the direct effect of specific ND on RCT, adjusting for potential confounders to determine if these disorders have causal effects on RCT independent of these confounding factors. Four MVMR approaches were adopted in this study, including an IVW estimator with multiplicative random effects, a median-based estimator, an Egger regression-based estimator, and a LASSO-type regularization method designed to shrink intercepts towards zero for valid IVs [

50].

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using various R packages, including “TwoSampleMR”, “MRPRESSO”, “forestplot”, and “ggplot2” within R software (version 4.3.2, The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Basic Information of SNPs

This study analyzed nine exposures, comprising eight neuropsychiatric disorders (ADHD, ASD, BD, epilepsy, MDD, OCD, and SCZ included) and RCT among European participants. When considering ASD and OCD as exposures, we set the relaxation threshold at

p ≤ 5 × 10

−6 because of the IV insufficiency. Similarly, for RCT as an exposure, the analysis between RCT and epilepsy also had a limited number of available IV, leading to the same relaxation threshold of

p ≤ 5 × 10

−6. For the remaining instrumental variables, extraction was conducted following strict thresholds of

p ≤ 5 × 10

−8. A detailed overview of the research design, data sources, and sample sizes associated with these exposure factors is presented in

Table 1. Additionally, information on the SNPs corresponding to the instrumental variables can be found in

Supplementary Tables S1–S9.

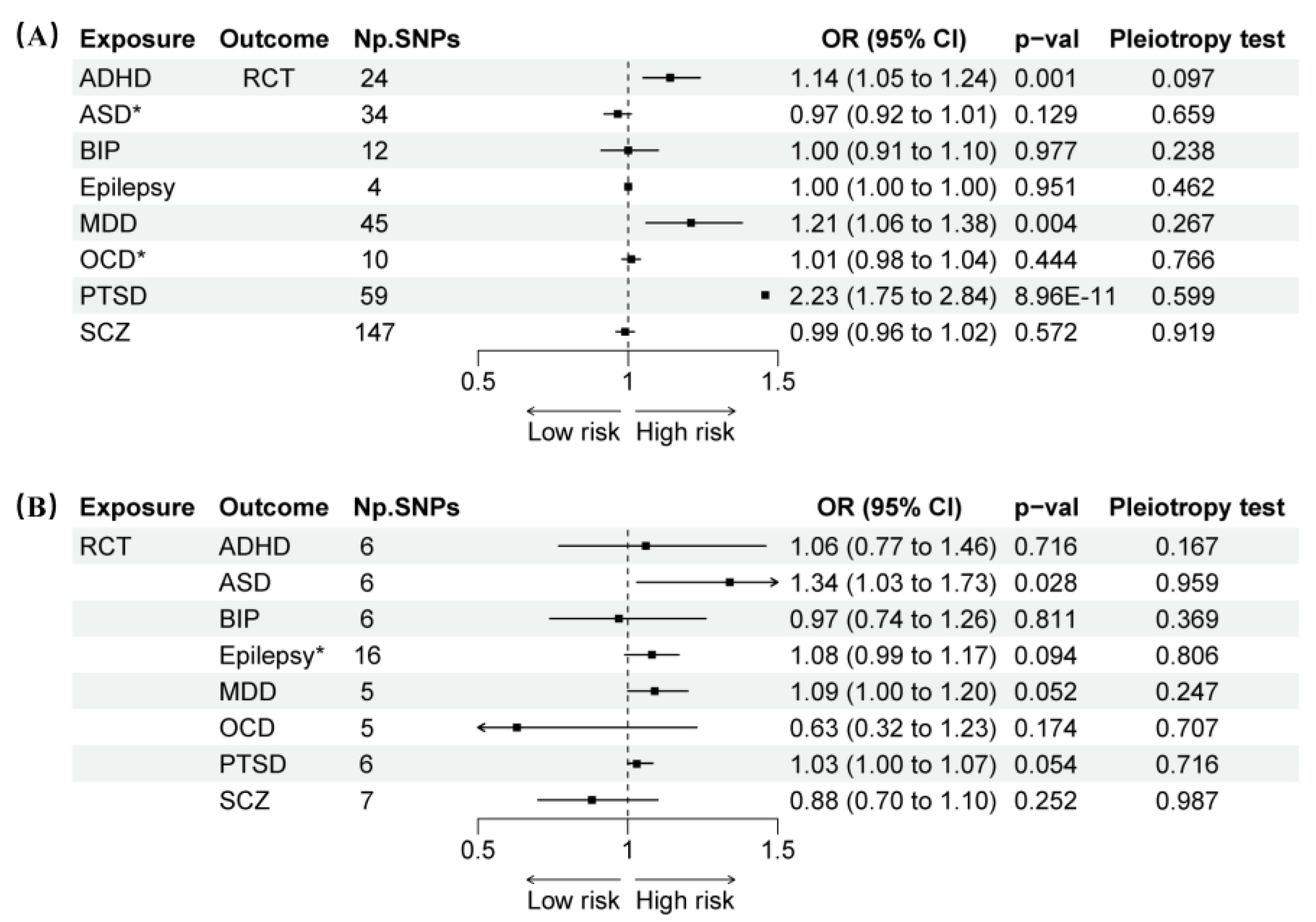

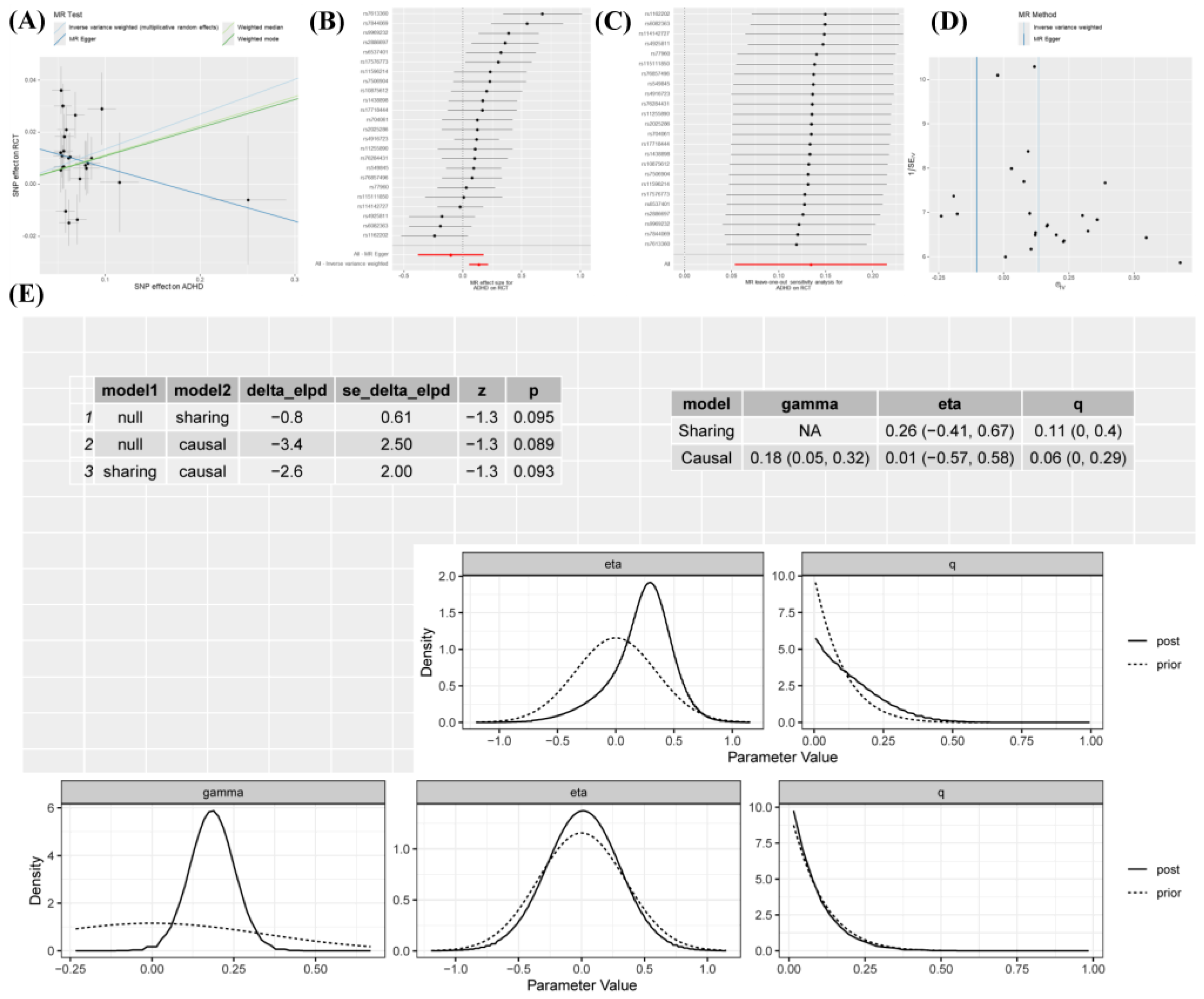

3.2. Causal Effects of ND on RCT

Results showed that the prevalence of ADHD was significantly correlated with RCT (IVW: OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.05–1.24,

p = 0.001) (

Figure 2). In contrast to the IVW results, the MR Egger analysis showed no evidence of directional pleiotropy, as indicated by the MR-Egger intercept scatter plot (

p = 0.097) and the funnel plot (

Figure 3). Comprehensive details of all MR analyses were recorded in

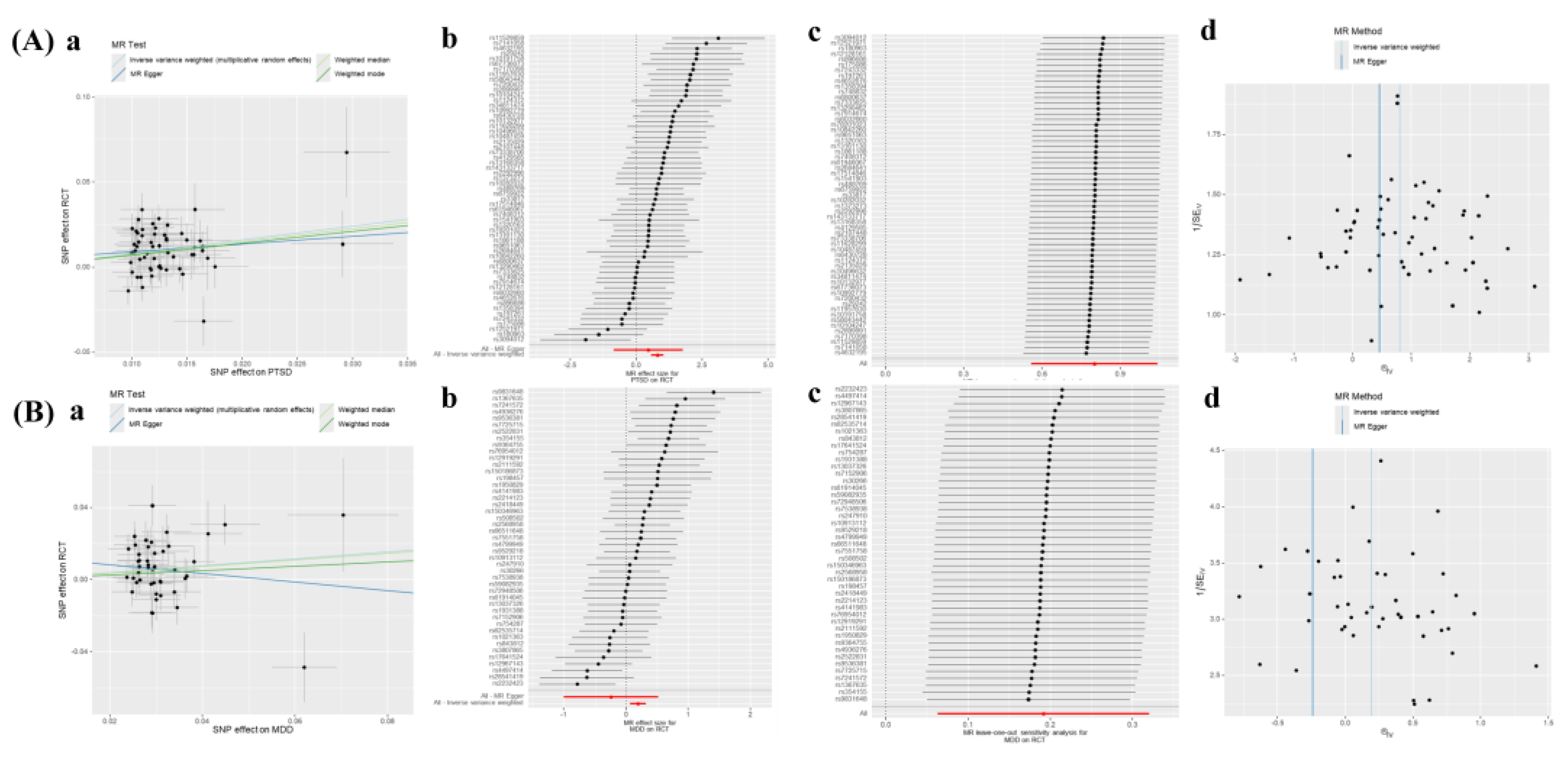

Supplement Table S10. Moreover, our analysis revealed a significant correlation between PTSD and MDD with RCT (PTSD: OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.75–2.84,

p < 0.001; MDD: OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.06–1.38,

p = 0.004) (

Figure 2), while no horizontal pleiotropy (Egger intercept:

p > 0.05) was observed (

Figure 4 and

Supplementary Table S10).

3.3. Causal Effects of RCT on ND

The reverse-direction MR showed RCT was associated with an increased risk of ASD with the IVW (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.03–1.73,

p = 0.028). No significant horizontal pleiotropy (Egger intercept:

p > 0.05) or heterogeneity (Cochran’s Q:

p > 0.05) was revealed by the analyses (

Figure 4 and

Supplementary Table S10). Although RCT exhibited a marginally increased risk for MDD and PTSD, these associations did not achieve statistical significance (

p > 0.05).

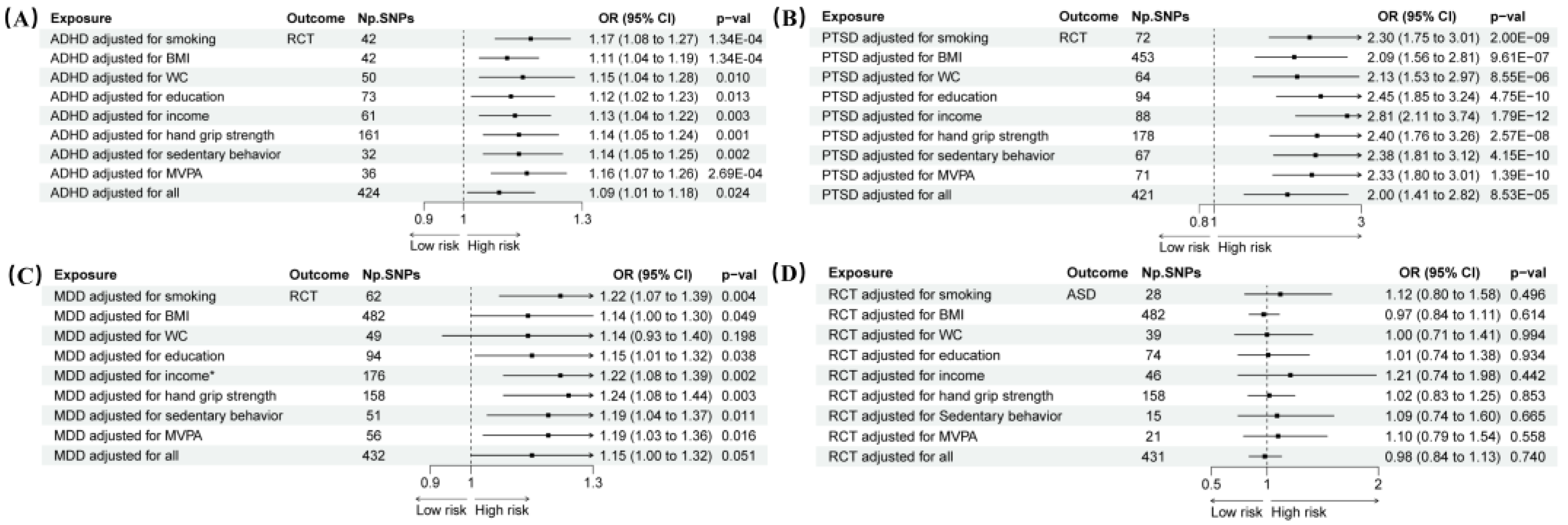

3.4. MVMR Analysis

MVMR analysis was performed, adjusting for important confounders including smoking, BMI, WC, education, income, hand grip strength, sedentary behavior, and MVPA. This adjustment did not substantially weaken the association between ADHD or PTSD and RCT (ADHD: OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01–1.18,

p = 0.024; PTSD: OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.41–2.82,

p = 8.53 × 10

−5). The results for ADHD and PTSD remained consistent when each confounding factor was adjusted for separately (

p < 0.05). However, it did reduce the association between MDD and RCT (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.68–1.66,

p = 0.783) (

Figure 5). Additionally, after adjusting for confounding factors, RCT did not significantly increase the risk of ASD. Detailed information on horizontal pleiotropy tests, heterogeneity tests, and MR analyses can be found in

Supplementary Table S11 and Supplementary Figures S1–S4.

4. Discussion

We employed bidirectional two-sample MR to clarify the potential causation between ND and RCT in this study. To date, this represents the first comprehensive research on these positive associations utilizing MR methodology. Current UVMR analysis revealed a causal effect of ADHD and PTSD on RCT risk; notably, ADHD is associated with a modest increase in RCT risk, while PTSD demonstrates a more pronounced risk elevation. MDD is also suggestively linked to RCT risk before adjustment for confounders. In reverse-direction MR, only ASD showed a potential association with RCT. However, after adjusting for cigarette consumption, household income, educational attainment, BMI, waist circumference, grip strength, physical activity, and sedentary behavior at work, MVMR unveiled that only ADHD and PTSD remained robustly identified as independent risk factors for RCT. Given the globally rising diagnoses of ND patients, integrating physical therapies into treatment strategies may help relive neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms [

23,

51,

52]. However, the clinical intervention for tendinopathy remains unsatisfactory [

13]. Thereby, recognizing the genetically predicted risk of RCT among these individuals is crucial. Raising awareness is essential for the appropriate early prevention and treatment of shoulder pain and dysfunction caused by RCT. This is particularly important for ND patients with ADHD or PTSD, who require proper exercise regimes in the real-world clinical practice. In addition, these findings might raise a new subcategory of neuropsychiatric RCT, thus advocating novel concepts of medical management and disease prognosis.

Growing evidence has consistently discovered unexpected intrinsic connections between ADHD or PTSD and musculoskeletal disorders. A cross-sectional comparative study has indicated ADHD shows a strong link to generalized joint hypermobility with musculoskeletal symptoms [

53]. Two potential hypotheses were suggested behind this relationship: either a shared genetic cause affects both the central nervous system and the connective tissue, or impaired proprioception leads to executive function overload [

54]. Interestingly, the current study’s MVMR, which intentionally adjusted for different physical activity levels, underscored the hypothesis that proprioception-mediated joint overactivity increases the risk of RCT in ADHD patients, while also solidifying the genetic predisposition comorbidity theory. Prior studies have supported that ADHD is a risk factor for many diseases such as tenosynovitis, shoulder pain, and frozen shoulder [

55,

56]. In alignment with these findings, our study confirms a positive association between ADHD and the risk of RCT from a genetic perspective. Systematic reviews have concluded that shoulder pain is generally overrepresented in individuals with PTSD, due to altered movement pattern triggered by psychological factors including fear, depression, anxiety and insomnia, which in turn heightens chronic stress and muscle tension in shoulder, potentially leading to overuse injury of rotator cuff tendons [

57,

58,

59]. Several studies also confirmed that PTSD is a risk factor for autoimmune thyroid disease, migraine, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases [

60,

61]. However, no research has distinguished the contributions of PTSD as an individual component in the incidence of RCT. Filling this research gap, the current MR analysis provides evidential support to a determinate causal effect of PTSD on RCT.

We speculate whether the influence of ADHD and PTSD on RCT risk is mediated by highly relevant shared pathophysiology. Both ADHD and PTSD are associated with the altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis [

62,

63]; this axis modulates the immune system in response to stress conditions [

64]. Hyperactivation of the HPA axis releases glucocorticoids that regulate multiple immune-related genes, including the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which leads to excessive systemic inflammation [

65], such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1 (IL-1), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [

65,

66,

67,

68]. These circulating pro-inflammatory mediators are critical for promoting tenocyte death and tendon matrix degradation while undermining tendon healing, central to the continuous disease progression of tendinopathy [

69,

70,

71,

72]. Elevated IL-1 and IL-6 have been observed in the subacromial bursa and partial thickness rotator cuff tear tissues [

73,

74,

75]; upregulated serum TNF-α has also been identified in the subacromial bursa harvested from symptomatic rotator cuff tendon surgeries [

76]. Furthermore, increased pro-inflammation and decreased anti-inflammation might be risk factors for RCT development [

77]. Therefore, a systemic pro-inflammatory condition could predispose ADHD and PTSD patients to RCT. However, further validation studies are required to substantiate this speculation since no research has revealed essential biomarkers that play a key role as regulatory molecules between ADHD or PTSD and RCT.

The key strength of this study is minimizing residual confounders and avoiding reverse causality by using bidirectional and multivariable MR analysis, thus enabling robust causal inferences between ADHD or PTSD and RCT. Inclusion of vast GWAS datasets for main types of ND and RCT ensures high statistical power and precise effect estimates. Additionally, sensitivity analyses distinguished potential violations of IV assumptions, enhancing the reliability of research findings. However, we recognized several limitations. Firstly, while employing MVMR, we could not include key factors like occupational activity, concomitant musculoskeletal conditions, and upper limb usage parameters in our adjustment due to a lack of relevant data, resulting in pleiotropy not being entirely excluded. Secondly, although FinnGen and PCG databases have some overlapped part. Our analysis utilized the latest FinnGen r12 version, while the current PCG is still based on an earlier FinnGen r5 version, attenuating the relevance of our two-sample MR analysis. Thirdly, this study was restricted to European ancestry participants, limiting the generalization of the findings. Lastly, the absence of individual-level raw data prevented researchers from conducting stratified analyses based on variables including age or gender, which restrained deeper exploration of the observed causal relationships. Future in-depth studies should address these drawbacks by harnessing more comprehensive datasets encompassing population subgroups with a broader diversity.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this two-sample MR study provided robust evidence supporting the genetic causality of ADHD and PTSD regarding the risk of developing RCT. Based on these findings, it is essential to enhance education, promote appropriate physical exercise, and raise awareness about the prevention and treatment of RCT specifically tailored for ADHD and PTSD populations. Further research is needed to explore the specific biomolecular mechanisms underlying the genetic links identified in this study and to develop early intervention strategies that could mitigate the risk of RCT in individuals with ADHD or PTSD.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: MVMR estimates for the causal associations between ADHD and RCT adjusting for confounders; Figure S2: MVMR estimates for the causal associations between MDD and RCT adjusting for confounders; Figure S3: MVMR estimates for the causal associations between PTSD and RCT adjusting for confounders; Figure S4: MVMR estimates for the causal associations between RCT and ASD adjusting for confounders; Table S1: Instrumental variables for ADHD; Table S2: Instrumental variables for ASD; Table S3: Instrumental variables for BD; Table S4: Instrumental variables for epilepsy; Table S5: Instrumental variables for MDD; Table S6: Instrumental variables for OCD; Table S7: Instrumental variables for PTSD; Table S8: Instrumental variables for SCZ; Table S9: Instrumental variables for RCT; Table S10: Sensitivity analyses of the causal effect between ND and RCT; Table S11: Sensitivity analyses of MVMR estimates for the causal associations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z., M.C., H.H. and P.S.; methodology, W.Z., M.C. and H.H.; software, W.Z., M.C. and H.H.; validation, W.Z., M.C. and H.H.; formal analysis, W.Z., M.C. and H.H.; investigation, W.Z., M.C. and H.H.; data curation, W.Z., M.C. and H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z., M.C. and H.H.; writing—review and editing, W.Z., M.C., H.H. and P.S.; visualization, W.Z., M.C. and H.H.; supervision, P.S.; project administration, P.S.; funding acquisition, W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the fellowship of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2022M723653.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this research will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASD |

Autism spectrum disorder |

| ADHD |

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| BD |

Bipolar disorder |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CAUSE |

Causal analysis using summary effect estimates |

| epiGAD |

Epilepsy Genetic Association Database |

| GWAS |

Genome-wide association studies |

| ICD-10 |

International Classification of Diseases-10 |

| IEU |

Integrative Epidemiology Unit |

| IL-1 |

Interleukin-1 |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| IV |

Instrumental variables |

| IVW |

Inverse variance weighted |

| MDD |

Major depressive disorder |

| MR |

Mendelian randomization |

| MVMR |

Multivariable Mendelian randomization |

| MVPA |

Moderate to vigorous physical activity |

| ND |

Neuropsychiatric disorders |

| OCD |

Obsessive compulsive disorder |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| PGC |

Psychiatric Genomics Consortium |

| PTSD |

Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| RCT |

Rotator cuff tendinopathy |

| SCZ |

Schizophrenia |

| SNPs |

Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| UKB |

UK Biobank |

| UVMR |

Univariable Mendelian randomization |

References

- Carragher, P.; Rankin, A.; Edouard, P. A One-Season Prospective Study of Illnesses, Acute, and Overuse Injuries in Elite Youth and Junior Track and Field Athletes. Front Sports Act Living 2019, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, K.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Kerr, Z.Y.; Golightly, Y.M.; Kucera, K.L.; Myers, J.B.; Rosamond, W.D.; Comstock, R.D. Epidemiology of Overuse Injuries in Collegiate and High School Athletics in the United States. Am J Sports Med 2015, 43, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viljoen, C.; Janse van Rensburg, D.C.C.; van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E.; Silva, B.; Scheer, V.; Besomi, M.; Gajardo-Burgos, R.; Matos, S.; Schoeman, M.; et al. Trail running injury risk factors: a living systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2022, 56, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, C.S.G.; Tadiello, F.F.; Medeiros, L.T.; Antonelo, M.C.; Alves, M.A.F.; Mendonca, L.D. Physical Therapy Service delivered in the Polyclinic During the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games. Phys Ther Sport 2019, 36, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaux, J.F.; Forthomme, B.; Goff, C.L.; Crielaard, J.M.; Croisier, J.L. Current opinions on tendinopathy. J Sports Sci Med 2011, 10, 238–253. [Google Scholar]

- Rinoldi, C.; Costantini, M.; Kijeńska-Gawrońska, E.; Testa, S.; Fornetti, E.; Heljak, M.; Ćwiklińska, M.; Buda, R.; Baldi, J.; Cannata, S. Tendon tissue engineering: effects of mechanical and biochemical stimulation on stem cell alignment on cell-laden hydrogel yarns. Advanced healthcare materials 2019, 8, 1801218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.S. Rotator cuff tendinopathy. British journal of sports medicine 2009, 43, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krampera, M.; Le Blanc, K. Mesenchymal stromal cells: Putative microenvironmental modulators become cell therapy. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1708–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottenheijm, R.P.; Joore, M.A.; Walenkamp, G.H.; Weijers, R.E.; Winkens, B.; Cals, J.W.; de Bie, R.A.; Dinant, G.-J. The Maastricht Ultrasound Shoulder pain trial (MUST): ultrasound imaging as a diagnostic triage tool to improve management of patients with non-chronic shoulder pain in primary care. BMC musculoskeletal Disorders 2011, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsell, L.; Dawson, J.; Zondervan, K.; Rose, P.; Randall, T.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Carr, A. Prevalence and incidence of adults consulting for shoulder conditions in UK primary care; patterns of diagnosis and referral. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006, 45, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Windt, D.A.; Koes, B.W.; de Jong, B.A.; Bouter, L.M. Shoulder disorders in general practice: incidence, patient characteristics, and management. Ann Rheum Dis 1995, 54, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Adebajo, A.; Hay, E.; Carr, A. Shoulder pain: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ 2005, 331, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedowitz, R.A.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ahmad, C.S.; Burks, R.T.; Flatow, E.L.; Green, A.; Iannotti, J.P.; Miller, B.S.; Tashjian, R.Z.; Watters, W.C., 3rd; et al. Optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011, 19, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.Y.; Song, S.Y.; Yoo, J.C.; Park, K.M.; Lee, S.M. Comparison of outcomes with arthroscopic repair of acute-on-chronic within 6 months and chronic rotator cuff tears. Journal of Shoulder Elbow Surgery 2017, 26, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitkanen, M.; Stevens, T.; Kopelman, M. Neuropsychiatric disorders. In Oxford Textbook of Medicine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 5268–5283. [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, C.-D.G.o.t.P.G. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. The Lancet 2013, 381, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, W.A. The prevalence and incidence of convulsive disorders in children. Epilepsia 1994, 35 Suppl 2, S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, L.; Beghi, E.; Oun, A.; Sillanpää, M. The epidemiology of epilepsy in Europe–a systematic review. European Journal of neurology 2005, 12, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annegers, J.; Hauser, W.; Lee, J.R.J.; Rocca, R. Secular Trends and Birth Cohort Effects in Unprovoked Seizures: Rochester, Minnesota 1935-1984. Epilepsia 1995, 36, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsopoulos, I.A.; Van Merode, T.; Kessels, F.G.; De Krom, M.C.; Knottnerus, J.A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence studies of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures. Epilepsia 2002, 43, 1402–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscio, A.M.; Stein, D.J.; Chiu, W.T.; Kessler, R.C. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry 2010, 15, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Chisholm, D.; Parikh, R.; Charlson, F.J.; Degenhardt, L.; Dua, T.; Ferrari, A.J.; Hyman, S.; Laxminarayan, R.; Levin, C.; et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet 2016, 387, 1672–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arensman, E.; Scott, V.; De Leo, D.; Pirkis, J. Suicide and Suicide Prevention From a Global Perspective. Crisis 2020, 41, S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasker, S.V.Z.; Challoumas, D.; Weng, W.; Murrell, G.A.; Millar, N.L. Is neurogenic inflammation involved in tendinopathy? A systematic review. BMJ open sport exercise medicine 2023, 9, e001494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, C.; Mc Auliffe, S.; Mallows, A.; O’sullivan, K.; Haines, T.; Malliaras, P. The strength of association between psychological factors and clinical outcome in tendinopathy: a systematic review. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0242568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallows, A.; Debenham, J.; Walker, T.; Littlewood, C. Association of psychological variables and outcome in tendinopathy: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017, 51, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjou, H.; Holtby, R.; Myhr, T. Gender differences in quality of life and extent of rotator cuff pathology. Arthroscopy 2006, 22, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E.; LeBlanc, J.; Sabo, M.T. Intersection of catastrophizing, gender, and disease severity in preoperative rotator cuff surgical patients: a cross-sectional study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2019, 28, 2284–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, J.D.; Suter, T.; Potter, M.Q.; Granger, E.K.; Tashjian, R.Z. Mental health has a stronger association with patient-reported shoulder pain and function than tear size in patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. JBJS 2016, 98, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Auliffe, S.; O'Sullivan, K.; Whiteley, R.; Korakakis, V. Why do tendon researchers overlook the patient’s psychological state? The review with no papers. Br J Sports Med 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey Smith, G.; Ebrahim, S. ‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? International journal of epidemiology 2003, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freshman, R.D.; Oeding, J.F.; Anigwe, C.; Zhang, A.L.; Feeley, B.T.; Ma, C.B.; Lansdown, D.A. Pre-existing Mental Health Diagnoses Are Associated With Higher Rates of Postoperative Complications, Readmissions, and Reoperations Following Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Arthroscopy 2023, 39, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, B.C.; Scribani, M.; Wittstein, J. Patients with depression and anxiety symptoms from adjustment disorder related to their shoulder may be ideal patients for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Journal of shoulder elbow surgery 2020, 29, S80–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrback, M.; Ramtin, S.; Abdelaziz, A.; Matkin, L.; Ring, D.; Crijns, T.J.; Johnson, A. Rotator cuff tendinopathy: magnitude of incapability is associated with greater symptoms of depression rather than pathology severity. Journal of Shoulder Elbow Surgery 2022, 31, 2134–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdin, C.A.; Khera, A.V.; Kathiresan, S. Mendelian Randomization. JAMA 2017, 318, 1925–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.M.; Holmes, M.V.; Davey Smith, G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ 2018, 362, k601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeland, I.J.; Kozlitina, J. Mendelian Randomization: Using Natural Genetic Variation to Assess the Causal Role of Modifiable Risk Factors in Observational Studies. Circulation 2017, 135, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, E.; Glymour, M.M.; Holmes, M.V.; Kang, H.; Morrison, J.; Munafò, M.R.; Palmer, T.; Schooling, C.M.; Wallace, C.; Zhao, Q. Mendelian randomization. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2022, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Writing Committee for the Attention-Deficit; Hyperactivity, D.; Autism Spectrum, D.; Bipolar, D.; Major Depressive, D.; Obsessive-Compulsive, D.; Schizophrenia, E.W.G.; Patel, Y.; Parker, N.; Shin, J.; et al. Virtual Histology of Cortical Thickness and Shared Neurobiology in 6 Psychiatric Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uffelmann, E.; Huang, Q.Q.; Munung, N.S.; De Vries, J.; Okada, Y.; Martin, A.R.; Martin, H.C.; Lappalainen, T.; Posthuma, D. Genome-wide association studies. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2021, 1, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrivankova, V.W.; Richmond, R.C.; Woolf, B.A.R.; Yarmolinsky, J.; Davies, N.M.; Swanson, S.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Timpson, N.J.; Dimou, N.; et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Using Mendelian Randomization: The STROBE-MR Statement. JAMA 2021, 326, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, N.R.; Ripke, S.; Mattheisen, M.; Trzaskowski, M.; Byrne, E.M.; Abdellaoui, A.; Adams, M.J.; Agerbo, E.; Air, T.M.; Andlauer, T.M.F.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat Genet 2018, 50, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Emmerich, A.; Pillon, N.J.; Moore, T.; Hemerich, D.; Cornelis, M.C.; Mazzaferro, E.; Broos, S.; Ahluwalia, T.S.; Bartz, T.M. Genome-wide association analyses of physical activity and sedentary behavior provide insights into underlying mechanisms and roles in disease prevention. Nature genetics 2022, 54, 1332–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okbay, A.; Beauchamp, J.P.; Fontana, M.A.; Lee, J.J.; Pers, T.H.; Rietveld, C.A.; Turley, P.; Chen, G.B.; Emilsson, V.; Meddens, S.F.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature 2016, 533, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.; Cho, S.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y.C.; Han, S.S.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.P.; Joo, K.W. A Mendelian randomization study found causal linkage between telomere attrition and chronic kidney disease. Kidney International 2021, 100, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, T.M.; Lawlor, D.A.; Harbord, R.M.; Sheehan, N.A.; Tobias, J.H.; Timpson, N.J.; Smith, G.D.; Sterne, J.A. Using multiple genetic variants as instrumental variables for modifiable risk factors. Statistical methods in medical research 2012, 21, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemani, G.; Tilling, K.; Davey Smith, G. Orienting the causal relationship between imprecisely measured traits using GWAS summary data. PLoS genetics 2017, 13, e1007081. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, J.; Knoblauch, N.; Marcus, J.H.; Stephens, M.; He, X. Mendelian randomization accounting for correlated and uncorrelated pleiotropic effects using genome-wide summary statistics. Nature genetics 2020, 52, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.J.; Burgess, S. Pleiotropy robust methods for multivariable Mendelian randomization. Stat Med 2021, 40, 5813–5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knöchel, C.; Oertel-Knöchel, V.; O’Dwyer, L.; Prvulovic, D.; Alves, G.; Kollmann, B.; Hampel, H. Cognitive and behavioural effects of physical exercise in psychiatric patients. Progress in neurobiology 2012, 96, 46–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.J.; Merwin, R.M. The Role of Exercise in Management of Mental Health Disorders: An Integrative Review. Annu Rev Med 2021, 72, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glans, M.; Thelin, N.; Humble, M.B.; Elwin, M.; Bejerot, S. Association between adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and generalised joint hypermobility: a cross-sectional case control comparison. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2021, 143, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Velasco, C.; Sinibaldi, L.; Castori, M. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, joint hypermobility-related disorders and pain: expanding body-mind connections to the developmental age. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2018, 10, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Marín, L.M.; Campos, A.I.; Cuéllar-Partida, G.; Medland, S.E.; Kollins, S.H.; Rentería, M.E. Large-scale genetic investigation reveals genetic liability to multiple complex traits influencing a higher risk of ADHD. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 22628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.-H. Causal relationship between ADHD and frozen shoulder: Two-sample Mendelian randomization. Medicine 2023, 102, e35883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, M.; Binnebose, M.; Wallis, H.; Lohmann, C.H.; Junne, F.; Berth, A.; Riediger, C. The Unhappy Shoulder: A Conceptual Review of the Psychosomatics of Shoulder Pain. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.K.; Li, M.Y.; Yung, P.S.; Leong, H.T. The effect of psychological factors on pain, function and quality of life in patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy: A systematic review. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2020, 47, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, N.; Clifford, C.; O'Neill, S.; Pedret, C.; Kirwan, P.; Millar, N.L. Biopsychosocial approach to tendinopathy. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2022, 8, e001326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maihofer, A.X.; Ratanatharathorn, A.; Hemmings, S.M.J.; Costenbader, K.H.; Michopoulos, V.; Polimanti, R.; Rothbaum, A.O.; Seedat, S.; Mikita, E.A.; Group, C.I.W.; et al. Effects of genetically predicted posttraumatic stress disorder on autoimmune phenotypes. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, C.J.; Longacre, L.S.; Cohen, B.E.; Fayad, Z.A.; Gillespie, C.F.; Liberzon, I.; Pathak, G.A.; Polimanti, R.; Risbrough, V.; Ursano, R.J. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease: state of the science, knowledge gaps, and research opportunities. JAMA cardiology 2021, 6, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookwalter, D.B.; Roenfeldt, K.A.; LeardMann, C.A.; Kong, S.Y.; Riddle, M.S.; Rull, R.P. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of selected autoimmune diseases among US military personnel. BMC psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccaro, L.F.; Schilliger, Z.; Perroud, N.; Piguet, C. Inflammation, Anxiety, and Stress in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Vale, W.W. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2006, 8, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katrinli, S.; Oliveira, N.C.S.; Felger, J.C.; Michopoulos, V.; Smith, A.K. The role of the immune system in posttraumatic stress disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, A.H.; Elgohary, T.M.; Nosair, N.A. Serum Interleukin-6 Level in Children With Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). J Child Neurol 2019, 34, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang-Dong, P.; Zhang, L.; Hong, C.; Jingjing, K.; Jinping, J. Correlation between interleukin-1b, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-a and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Matern Child Health Care China 2012, 27, 370–373. [Google Scholar]

- Schnorr, I.; Siegl, A.; Luckhardt, S.; Wenz, S.; Friedrichsen, H.; El Jomaa, H.; Steinmann, A.; Kilencz, T.; Arteaga-Henríquez, G.; Ramos-Sayalero, C. Inflammatory biotype of ADHD is linked to chronic stress: a data-driven analysis of the inflammatory proteome. Translational psychiatry 2024, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisari, E.; Rehak, L.; Khan, W.S.; Maffulli, N. Research. Tendon healing is adversely affected by low-grade inflammation. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 2021, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann, N.; Bowlby, C.; Coughlin, H.; Belacic, Z.; Sullivan, S.; Durgam, S. Interleukin-6 upregulates extracellular matrix gene expression and transforming growth factor β1 activity of tendon progenitor cells. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2023, 24, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, W.; Dakin, S.G.; Snelling, S.J.B.; Carr, A.J. Cytokines in tendon disease: A Systematic Review. Bone Joint Res 2017, 6, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhao, K.; Chen, X.; Yin, Z.; Heng, B.C.; Chen, W.; Shen, W. The roles of inflammatory mediators and immunocytes in tendinopathy. J Orthop Translat 2018, 14, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voloshin, I.; Gelinas, J.; Maloney, M.D.; O'Keefe, R.J.; Bigliani, L.U.; Blaine, T.A. Proinflammatory cytokines and metalloproteases are expressed in the subacromial bursa in patients with rotator cuff disease. Arthroscopy 2005, 21, 1076–e1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaine, T.A.; Kim, Y.S.; Voloshin, I.; Chen, D.; Murakami, K.; Chang, S.S.; Winchester, R.; Lee, F.Y.; O'Keefe R, J.; Bigliani, L.U. The molecular pathophysiology of subacromial bursitis in rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005, 14, 84S–89S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.W.; Choi, B.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Yoon, J.P.; Oh, K.S.; Park, K.S. Altered Gene and Protein Expressions in Torn Rotator Cuff Tendon Tissues in Diabetic Patients. Arthroscopy 2017, 33, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, B.J.; Franklin, S.L.; Carr, A.J. A systematic review of the histological and molecular changes in rotator cuff disease. Bone Joint Res 2012, 1, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanthan, K.; Feyh, A.; Visweshwar, H.; Shapiro, J.I.; Sodhi, K. Systematic Review of Metabolic Syndrome Biomarkers: A Panel for Early Detection, Management, and Risk Stratification in the West Virginian Population. Int J Med Sci 2016, 13, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).