1. Introduction

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is a complex, often debilitating, chronic disease that affects around 3.3 million people in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA) and 17 – 24 million worldwide. Patients suffering from ME/CFS experience post-exertional malaise, severe fatigue, cognitive disturbances/brain fog, sleep and immunological dysfunctions with a pronounced impact on daily quality of life [

1]. The biomolecular mechanisms behind ME/CFS are still unknown. However, the onset of ME/CFS in most cases occurs after an episode with flu-like symptoms, indicating that infectious agents can play a role in the continuing symptoms of the disease [

2]. EBV-induced infectious mononucleosis is often reported at the onset of ME/CFS, as well as other infectious agents i.e. Ross River virus,

Coxiella burnetii, West Nile virus, and SARS-CoV-2 [

1,

3,

4]. Non-infectious events such as physical or mental stress, toxins, or trauma are known triggers of ME/CFS [

5].

Following the occurrence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the prevalence of patients suffering from prolonged symptoms lasting for more than 6 months e.g. long COVID, is estimated to affect between 5% and 43% of infected patients. Most long COVID symptoms are also seen in ME/CFS, and it is difficult to distinguish between these two conditions [

6].

We previously showed that in SARS-CoV-2 infected persons, the antibody titres in saliva against EBV and HHV6 were significantly increased, indicating a reactivation of these viruses after an infections trauma such as COVID-19 [

7]. The anti-EBV mucosal Abs were more enhanced in ME/CFS patients compared to healthy donors. In a recent study, we also showed that the concentration of human adenovirus (HAdV) antibodies in saliva was increased after infection with SARS-CoV-2 [

8]. These findings raised the question of which role HAdV and/or herpesviruses play in the pathogenesis of ME/CFS.

EBV, HCMV, HHV6, SARS-CoV-2, and HAdV all replicate in the airway epithelium. These viruses are transmitted via saliva, sputum, or via inhalation of droplets from infected individuals and can establish persistent infections in their host, in part through evading host immune surveillance. Here, we have investigated the presence of several viruses in airway mucosa by analyzing sputum samples derived from ME/CFS patients and controls. We have hypothesized that dysfunctional IFN signaling underlies aberrant control of viral infection by analyzing autoAbs to IFN-I.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Sputum samples from patients (n=13, mean age 49.8 yrs, range of 22-61 yrs) diagnosed with ME/CFS according to the 2003 Canadian Consensus Criteria [

9,

10] were recruited from the regional (Östergötland) Association for ME patients

. The duration of ME/CFS disease in this group was 14.2 years with a range of 8-28 years. Sputum samples were also collected from healthy age-matched donors (HD) (n=10, mean age 51.0 yrs, range 33-66 yrs). The age of ME/CFS vs HD did not differ (

p= 0.7089) (

Table 1). Four elderly healthy donors (Senior control donors, SENIORS) were also recruited; mean age 72.5 yrs, range 65-77 yrs, as well as two immunosuppressed participants: one B-cell depleted donor (Rituximab anti-CD19 mAb treated, named NEG CTR, based on the low count of Ab-releasing B-cells and EBV), and one glucocorticoid immunosuppressed donor (treatment of asthma, named POS CTR, based on presence of all analyzed viruses except SARS-CoV-2 ). The POS and NEG CTR donors were both active and working 100%. Demographic data, including sex, age, and duration of ME/CFS disease, of the study participants is presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Ethical Permit

The study was reviewed and approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, Regional Ethics Committee (D.nr. 2019-0618 and 2024-00365-02). Health declarations, medical data, and sputum samples were collected after written informed consent.

2.3. Sputum Collection

Sputum samples were collected in the morning according to detailed instructions, including deep breathing and coughing. The mucus sputum sample was collected in a sterile 50 ml plastic tube, avoiding saliva contamination. Sputum samples were diluted with an equal volume 0.9% NaCl solution, mixed vigorously for 2 min to reduce viscosity and facilitate handling, then frozen at -80o C.

2.4. PCR Analysis of EBV, HCMV, HHV6, HAdV, and SARS-CoV-2 in Sputum

All samples were analysed for HAdV [

11], EBV, HCMV [

12], HHV6 (forward primer 5'-GCG TTT TCA GTG TGT AGT TCG G-3', reverse primer 5'-TTC TGT GTA GGC GTT TCG ATC A-3', probe 5'FAM--CCT CAA CCT AGC GCT CGG GGC T-TAMRA-3´; unpublished) and SARS-Cov-2 (modified from Corman et al. [

13]) with real-time PCR at Department of Clinical Microbiology, Umeå University

. DNA was prepared from sputum diluted with equal volume of isotonic NaCl, followed by routine extraction using the QIASymphony® DSP Virus/Pathogen Midi Kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany).

2.5. ELISA Analysis of IgG autoAbs to Type-I IFN

The assay was performed as previously described [

14]. In brief, ELISA was performed in 96-well ELISA plates (Maxisorp; Thermo Fisher Scientific) coated overnight in 4

o C with 1 µg/ml recombinant human IFN-α2 (ref. number 130-093-873; Miltenyi Biotec). The plates were washed in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20, blocked by assay buffer (PBS, 0.05% Tween 20, 0.5% BSA), washed and incubated with a 1:16 dilution of sputum samples from ME/CFS and control groups for 2 h at room temperature. Each sample was tested in duplicate. Plates were washed with PBS, 0.05% Tween 20, and incubated with a goat anti-human IgG (Fc)-HRP conjugate (Bio-Rad) at a 1:5000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. After a final wash in PBS, 0.05% Tween 20, the TNB substrate was added and optical density was measured at 450 nm.

3. Results

3.1. Viral Load of EBV, HCMV, HHV6, HAdV, and SARS-CoV-2 in Sputum

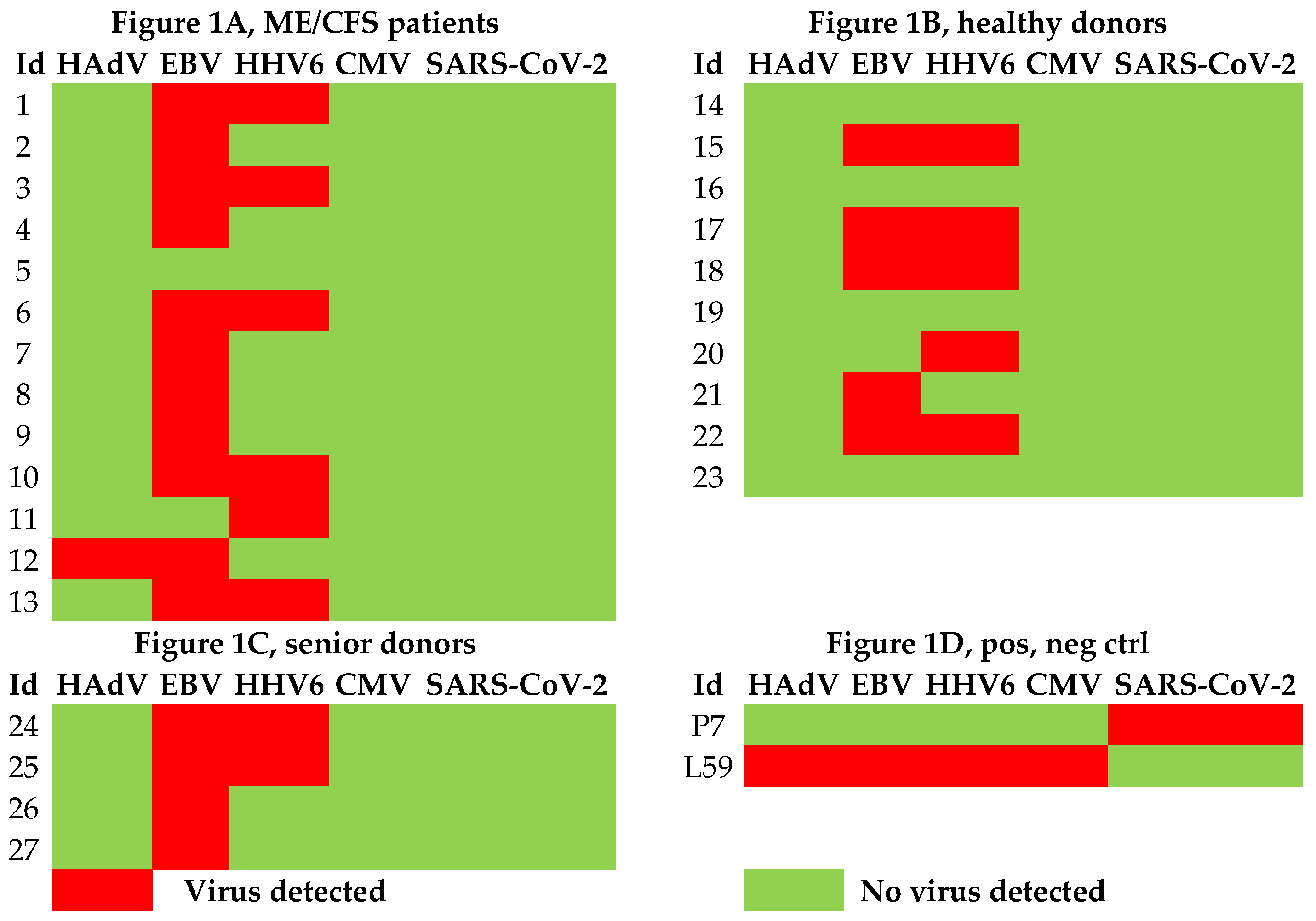

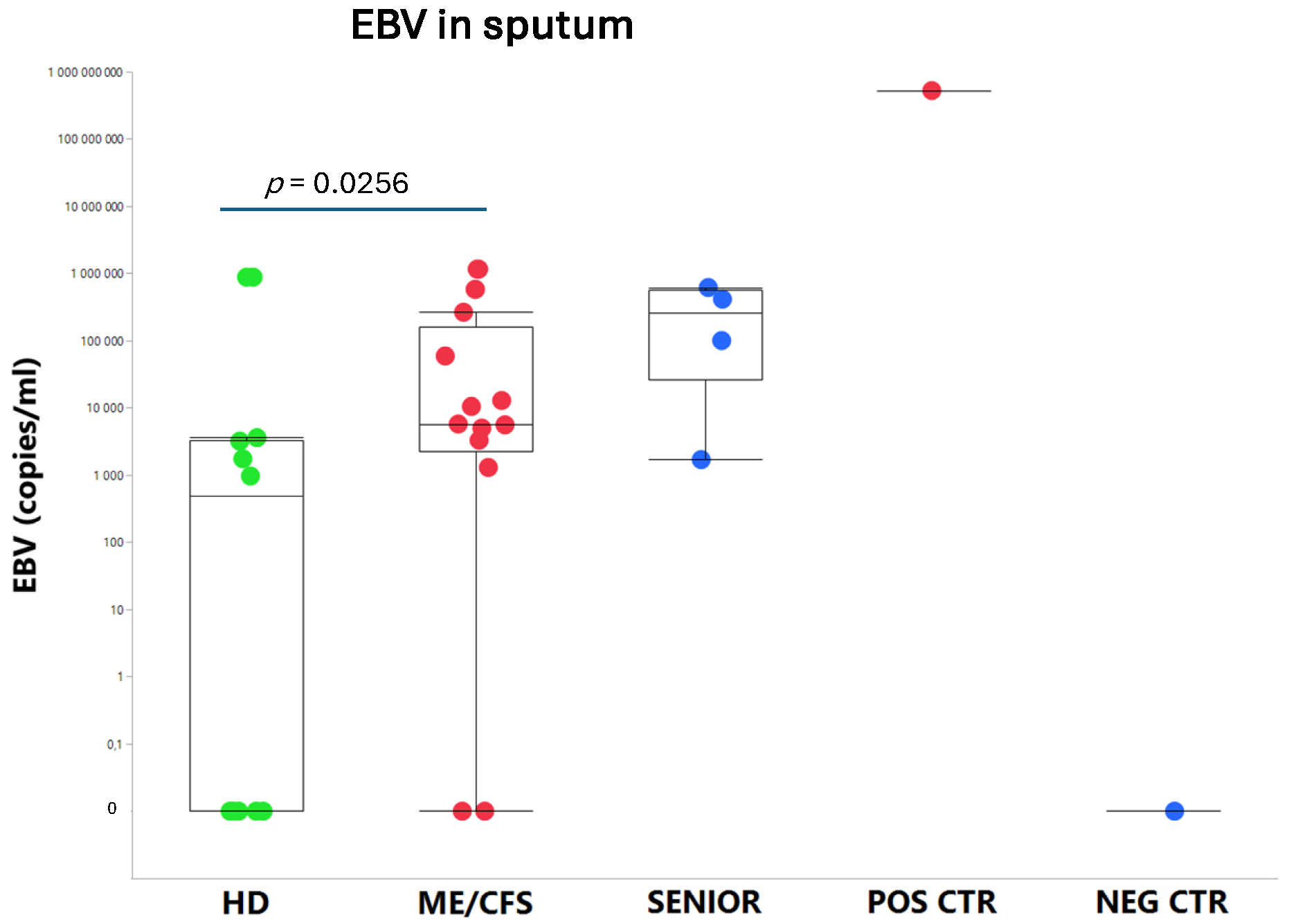

We found that ME/CFS patients more frequently (85%, 11/13) released EBV compared to HD (50%, 5/10) (

Figure 1) and that the viral load, measured as the number of EBV copies/ml, was significantly elevated compared to age-matched controls (

p=0.0256) (

Figure 2A). The highest EBV load in sputum was found in the immunosuppressed/ glucocorticoid treated asthmatic donor who inhaled glucocorticoids twice a day. This participant released all viruses tested into sputum, except SARS-CoV-2. In the SENIOR group, all 4 participants were positive for EBV. The negative control donor (B-cell depleted), was devoid of EBV (

Figure 2A), due to the absence of B cells, explained by the fact that EBV is harboured in small resting B-cells in its latency state.

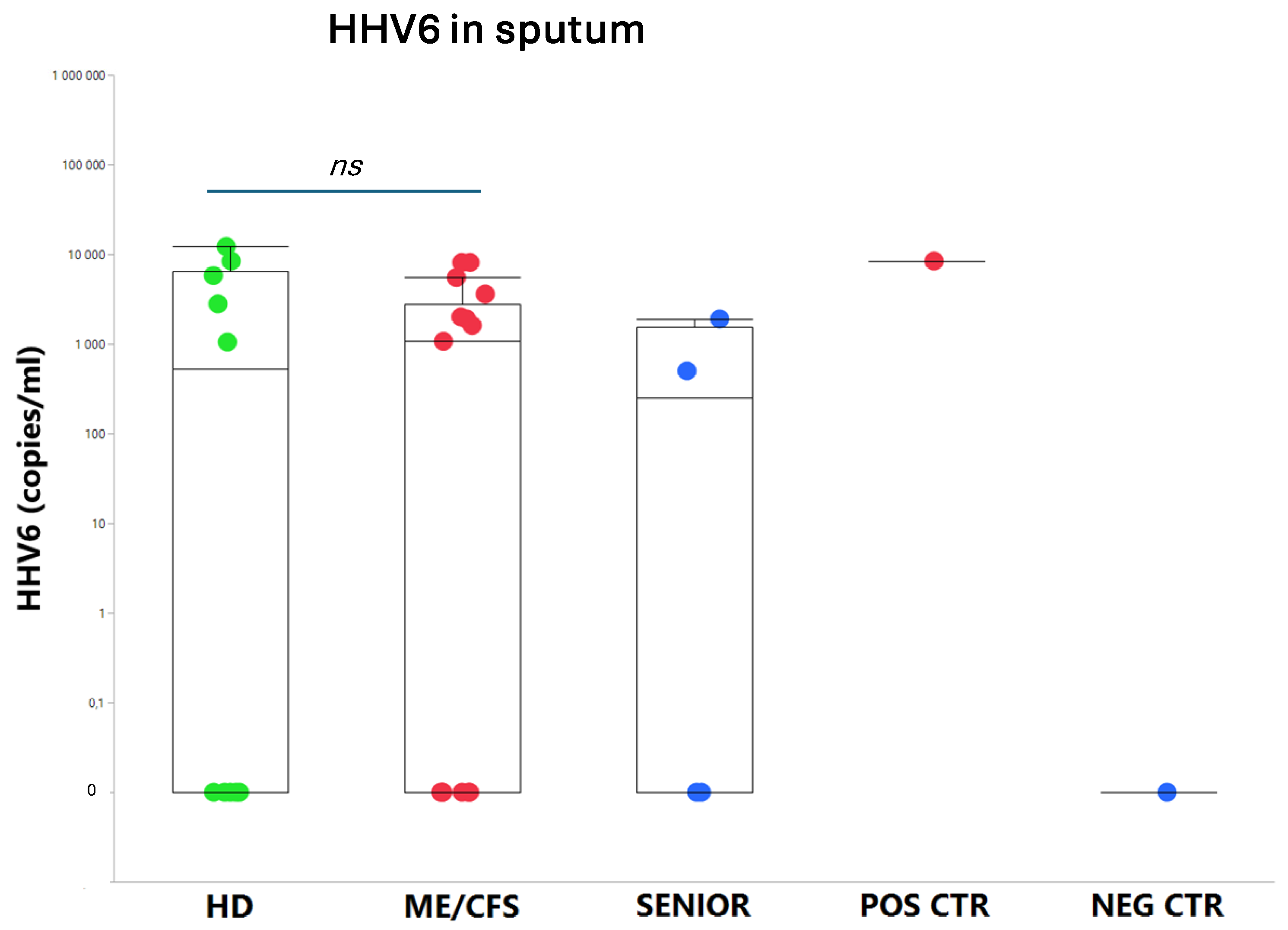

The presence of HHV6 was demonstrated in 6 out of 13 patients in the ME/CFS group. In the HD control group, 5 out of 10 were PCR positive for HHV-6. In the SENIOR group, 2 out of 4 participants were HHV6 positive. There was no statistical difference in viral load of HHV6 in ME/CFS vs HD. HCMV was not detected in the sputum of any of the 29 participants in the study, except in a glucocorticoid immunosuppressed control donor (

Figure 2B).

HAdV was detected in a ME/CFS patient (Id12) with severe symptoms but in none of the HD and SENIOR controls. HAdV was detected, however, in the immunosuppressed/glucocorticoid-treated donor, who was positive for all viruses tested except SARS-CoV-2. Id12 is a patient (age 22 yrs) with severe and long-lasting (12 yrs) ME/CFS. The patient was wheelchair-bound due to severe symptoms. The other ME/CFS participants (12/13) had mild/moderate symptoms, and none was bedridden or wheelchair-bound at the time of sputum collection.

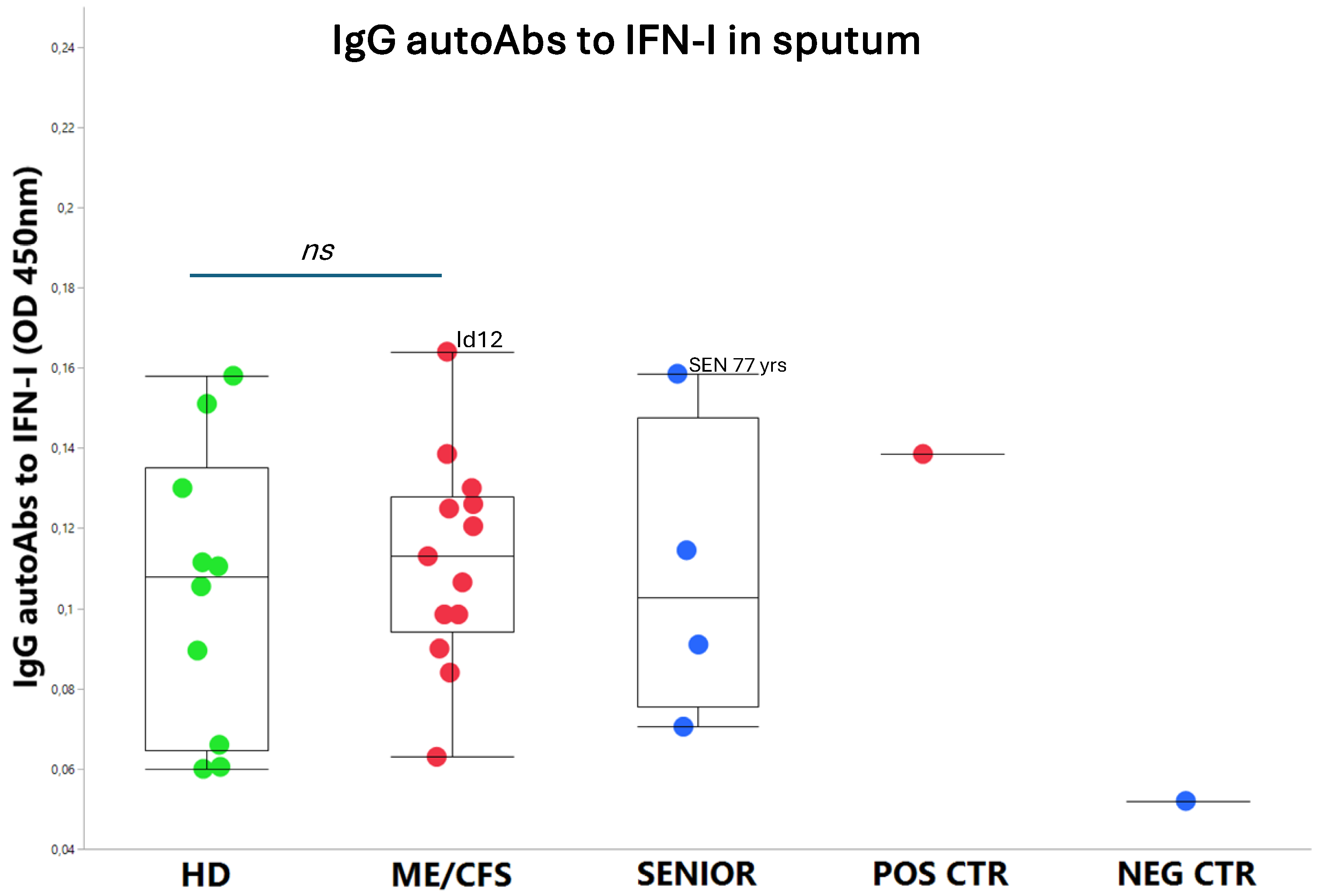

3.2. IgG autoAbs Against IFN-I in ME/CFS Patients

On a group level, the autoAbs to IFN-I were slightly elevated in ME/CFS patients, albeit not significantly more than in HD controls. Notably, patient Id12 showed the highest level of autoAbs to IFN-I of all participants (

Figure 3). Additionally, among the SENIORS, the eldest participant (age 77 yrs) showed the second highest level of anti-IFN-I autoAbs. All participants were positive for anti-type-I IFN IgG autoAbs except the negative control (B cell depleted).

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings - Sputum Content of Reactivated Viruses and autoAbs to IFN-I

We have explored the release of reactivated latent viruses in airway mucosa by collecting sputum samples from 29 participants: ME/CFS patients, age-matched healthy controls, elderly healthy controls and immunosuppressed active controls. We found that ME/CFS patients had a significantly higher viral copy number/ml of EBV compared to healthy donors. HHV6 was released in 50% of participants. HAdV was not found in patients nor in controls except for a young ME/CFS patient with severe symptoms and one of the participants treated with airway glucocorticoids. AutoAbs to type I IFN were not raised in the investigated ME/CFS cohort, apart from the very same patient that released HAdV, and in the eldest 77-yr-old participant.

4.2. ME/CFS Immune and Antiviral Dysregulation -Unknown Mechanisms of Action

ME/CFS and long COVID are debilitating multisystemic conditions sharing similarities in immune dysregulation and cellular signaling pathways, contributing to a state of immune exhaustion profile in the pathophysiology [

15]. These post-acute infection syndromes (PAIS) are subjects of intense research due to the lack of understanding of the underlying mechanisms, representing a significant blind spot in the field of medicine [

5,

7,

16,

17,

18]. Among the identified risk factors are reactivated latent viruses, including EBV and specific autoAbs [

19]. AutoAbs to IFN-I have recently been reported in severe infection: COVID-19 [

20,

21,

22]; Ross River virus [

23,

24]; West Nile virus [

14], and in non -SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infections [

25]. Notably, these infections are all reported to develop, at a certain frequency, into post-infectious fatigue syndrome sharing most symptoms with ME/CFS [

5]. Furthermore, autoAbs to IFN-I are present in higher concentration in approximately 4% of uninfected individuals over 70 years old [

21], in autoimmune diseases such as SLE and Sjögren’s syndrome [

26], and in severe of disseminated viral infections caused by VZV, HCMV, or HAdV [

27]. It is not known whether autoAbs to IFN-I are present in conditions of lytic viral infections by EBV. Therefore, we hypothesised in this study that autoAbs to IFN-I are present in ME/CFS patients – a condition in which oral mucosal Abs against EBV are overexpressed compared to healthy controls [

7], indicating a higher level of lytic release of the virus in the mucosa. However, in contrast to our hypothesis, we found in the present study that the majority of the patients and controls expressed moderate levels of IFN-I Abs, with two notable exceptions: one severely affected ME/CFS patient expressing HAdV and EBV, and one control participant, treated with airway glucocorticoid, expressing HAdV, EBV, HHV6, and HCMV. These findings indicate that in mild/moderate ME/CFS conditions, release of EBV and HHV6 is not associated with raised levels of autoAbs to IFN-I, whereas HAdV is released in severe ME/CFS. These findings are substantiated by others showing that HAdV and HCMV infections in immunocompromised donors have elevated anti-IFN-I autoAbs that may play a crucial part in down-regulating the antiviral immune defence [

26].

4.3. Overload of Epstein-Barr Virus in ME/CFS

Shikova et al [

28] analyzed in plasma samples EBV, HHV6, and HCMV among 58 ME/CFS patients compared to 50 healthy controls, using PCR analysis. They found no significant difference between the two groups regarding presence of HHV6 or HCMV, whereas a significant increase of EBV was detected (

p=0.0027). These findings corroborate and are in line with the present results in sputum, where we find a significantly higher number of EBV viral copies (

p=0.0256) in ME/CFS patients.

4.4. Human Adenovirus and Herpesvirus Reactivation in Airways

Our present study is of explorative nature and a limited pilot study, therefore, it is of interest to further investigate whether HAdV can have a role in the pathophysiology of ME/CFS, particularly in severe patients. The frequency of HAdV infection in patients with airway symptoms in the Swedish population was reported by the Public Health Agency of Sweden between September 29, 2023, and April 7, 2024, analyzing HAdV in 32,245 cases, of which 2.2% were positive (

www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se). The numbers indicates that active HAdV infection is not frequent in the Swedish population. HAdV infection among ME/CFS patients would be of interest for comparison to healthy controls. Sputum is a superior source for detection of HAdV compared to nasopharyngeal swabs as reported by Jeong et al [

29]. They found that among 134 patients with respiratory infection, 11 patients in total were positive for HAdV in nasopharyngeal and/or sputum samples. In sputum the rate of detection was 91% and in nasopharyngeal swabs, 46% was detected [

29].

Both HAdV and herpesviruses establish persistent infections in humans [

30]. HAdV persistence can occur in different sites of the body, for example, in T-lymphocytes from tonsils, adenoids, and intestine, in brain tissue, and in airway epithelial cells [

30,

31,

32]. HAdV was detected in 13 out of 25 brain tissue samples [

33]. The authors conclude that the central nervous system can be infected, but it is an overlooked site for HAdV persistent infection. It would be of great importance to analyze whether HAdV infections in the central nervous system could explain the neurological symptoms often seen in ME/CFS. Multiple studies indicate that ME/CFS is initiated and perpetuated by viruses, e.g. herpesviruses and/or possibly HAdV in severe cases, justifying the onset of well-controlled studies exploring antiviral medication to treat ME/CFS.

4.5. Latent Virus – Host Immune Balance

Virgin et al [

34] has reviewed the intricate balance and synergy in the co-existence between latent viruses and the host, which to a large extent also involves epigenetic regulations both from the host and the virus side [

17]. The antiviral responses could be dysfunctional by, for instance, blocking of IFN by autoAbs to IFN-I, release of neutralizing antiviral Abs, and the condition of the immune system such as other infections, severe stress, toxins, or trauma. Such an attenuation and decrease of the immune system is known to initiate the start of the latent-to-lytic viral program with the release of reactivated viral particles followed by worsening of the ME/CFS symptoms. Type I interferons are produced in response to viral infection as a key part of the innate immune response with potent antiviral, antiproliferative, and immunomodulatory properties. This cytokine binds a plasma membrane receptor made of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 that is ubiquitously expressed and thus is able to act on virtually all body cells. A deficiency of type I interferon in the blood is thought to be a hallmark of severe COVID-19 and may provide a rationale for a combined therapeutic approach [

35].

Dysfunctional IFN signaling underlies aberrant responses to infection and autoimmune diseases, including type I interferonpathies such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [

36]. Multiple antiviral IFN-I dysregulations have been described, including viral evasion of immune recognition by viral proteins antagonizing the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway [

37] [

38], dysregulated IFNA2 receptor by formation of novel isoforms via transposon exonization [

39], and autoAbs neutralizing IFN-I [

14,

20].

Recently, we reported that COVID-19 triggered higher saliva anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG, as well as elevated saliva IgG against reactivated HAdV [

8] and EBV [

7] in ME/CFS patients compared to healthy controls. The main take-home lesson from the present pilot study is that ME/CFS patients release a significant amount of reactivated viral copies in airway epithelium/sputum and that autoAbs to IFN-I are not elevated in mild/moderate conditions, albeit in severe ME/CFS and the elderly.

4.6. Limitation of the Study

The number of participants in the study is small and demands further studies in larger cohorts. The presence of released herpesviruses, predominantly EBV in sputum, as observed here, is however, supported by parallel studies showing reactivated EBV in blood, and also underlines our recent study that saliva antivirus IgG (EBV and HAdV) is elevated in ME/CFS.

4.7. Future Perspectives and Visions for Treatment Viral Driven Post-Acute Infection Syndromes

ME/CFS and long COVID share similarities in antiviral immune dysregulation and intense biomarker and therapeutic explorative studies are much in focus [

40]. It would be of interest to perform longitudinal studies on shedding of herpesviruses and HAdV variation over time. This could possibly disclose a connection between increased virus shedding and activation of previously clinically silent, persistent infection in lymphoid tissue [

30,

33,

41] as well as any relation to symptom level. Clinical well-controlled studies including severe ME/CFS in antiviral therapy are much needed. For example, intravenous Brincidofovir therapy has few side effects and is highly effective against HAdV [

42]. Brincidofovir also exhibits pronounced activity against EBV, HCMV [

43,

44], and HHV6 [

45]. To determine the role of HAdV and herpesviruses in the pathogenesis of ME-CFS, more extensive studies should be performed that include a larger number of participants. The most abundant sites of HAdV replication and infectious virus production are the intestine, the lower airway tract, and the eyes, where the virus can cause a variety of clinical manifestations ranging from mild to severe diseases [

46]. Notably, prior to the onset of ME/CFS, a majority of patients report irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Besides intestinal lymphocytes, there are convincing findings showing that HAdV can establish persistent infections in tonsillar and adenoidal T-lymphocytes, in epithelium cells of the lung mucosa, and in brain tissue [

30,

41,

47,

48].

Brincidofovir is a lipid conjugate that is highly active against HAdV but also has antiviral activity against herpesviruses [

42]. In an ongoing Phase 2a Clinical Trial (NCT04706923), the antiviral activity of intravenous Brincidofovir is being evaluated in immunocompromised patients with HAdV viremia or disseminated HAdV disease. Preliminary results from this clinical trial [

49] showed that BCV IV given 0.4 mg/kg twice weekly, had a highly effective antiviral activity against HAdV. With this regime, viremia clearance was achieved in 10 out of 10 patients after a mean duration of treatment for 5.1 weeks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.H. and A.R.; Methodology, A.A. A.R.; Investigation, U.H. A.A. K.N. A.R.; Writing – Original draft, U.H. and A.R.; Writing –Review & Editing, U.H., A.A., K.N., A.R.; Funding Acquisition, A.R.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Prof. J. Hinkula and Dr. Eirini Apostolou for reading the manuscript and giving valuable comments. Thanks to Prof. J. Hinkula for the kind gift of an anti-human IgG-HRP conjugate. Funding was received from Swedish Research Council (4.3-2019-00201 GD-2020-138), Swedish Cancer Society (no. 211832Pj01H2/Infection-Autoimmunity-B-lymphoma grant) and local Linköping University funds (A.R.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bateman, L.; Bested, A. C.; Bonilla, H. F.; Chheda, B. V.; Chu, L.; Curtin, J. M.; Dempsey, T. T.; Dimmock, M. E.; Dowell, T. G.; Felsenstein, D., et al. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Essentials of Diagnosis and Management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96,2861-2878.

- Hanson, M. R. The viral origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS Pathog 2023, 19, e1011523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickie, I.; Davenport, T.; Wakefield, D.; Vollmer-Conna, U.; Cameron, B.; Vernon, S. D.; Reeves, W. C.; Lloyd, A.; Dubbo Infection Outcomes Study, G. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2006, 333, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naess, H.; Sundal, E.; Myhr, K. M.; Nyland, H. I. Postinfectious and chronic fatigue syndromes: clinical experience from a tertiary-referral centre in Norway. In Vivo 2010, 24, 185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg, J.; Gottfries, C. G.; Elfaitouri, A.; Rizwan, M.; Rosén, A. Infection Elicited Autoimmunity and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: An Explanatory Model. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaroff, A. L.; Lipkin, W. I. Insights from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome may help unravel the pathogenesis of postacute COVID-19 syndrome. Trends Mol Med 2021, 27, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolou, E.; Rizwan, M.; Moustardas, P.; Sjögren, P.; Bertilson, B. C.; Bragée, B.; Polo, O.; Rosén, A. Saliva antibody-fingerprint of reactivated latent viruses after mild/asymptomatic COVID-19 is unique in patients with myalgic-encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 949787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannestad, U.; Apostolou, E.; Sjögren, P.; Bragée, B.; Polo, O.; Bertilson, B. C.; Rosén, A. Post-COVID sequelae effect in chronic fatigue syndrome: SARS-CoV-2 triggers latent adenovirus in the oral mucosa. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1208181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, B. M. Definitions and aetiology of myalgic encephalomyelitis: how the Canadian consensus clinical definition of myalgic encephalomyelitis works. J Clin Pathol 2007, 60, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, B. M.; van de Sande, M. I.; De Meirleir, K. L.; Klimas, N. G.; Broderick, G.; Mitchell, T.; Staines, D.; Powles, A. C.; Speight, N.; Vallings, R., et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J Intern Med. 2011;270,327-338.

- Hernroth, B. E.; Conden-Hansson, A. C.; Rehnstam-Holm, A. S.; Girones, R.; Allard, A. K. Environmental factors influencing human viral pathogens and their potential indicator organisms in the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis: the first Scandinavian report. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68, 4523–4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindele, A.; Holm, A.; Nylander, K.; Allard, A.; Olofsson, K. Mapping human papillomavirus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, and p16 in laryngeal cancer. Discov Oncol 2022, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corman, V. M.; Landt, O.; Kaiser, M.; Molenkamp, R.; Meijer, A.; Chu, D. K.; Bleicker, T.; Brunink, S.; Schneider, J.; Schmidt, M. L., et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25.

- Gervais, A.; Rovida, F.; Avanzini, M. A.; Croce, S.; Marchal, A.; Lin, S. C.; Ferrari, A.; Thorball, C. W.; Constant, O.; Le Voyer, T., et al. Autoantibodies neutralizing type I IFNs underlie West Nile virus encephalitis in approximately 40% of patients. J Exp Med. 2023;220.

- Eaton-Fitch, N.; Rudd, P.; Er, T.; Hool, L.; Herrero, L.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Immune exhaustion in ME/CFS and long COVID. JCI Insight 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomberg, J.; Rizwan, M.; Bohlin-Wiener, A.; Elfaitouri, A.; Julin, P.; Zachrisson, O.; Rosén, A.; Gottfries, C. G. Antibodies to Human Herpesviruses in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, E.; Rosén, A. Epigenetic reprograming in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A narrative of latent viruses. J Intern Med 2024, 296, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choutka, J.; Jansari, V.; Hornig, M.; Iwasaki, A. Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes. Nat Med 2022, 28, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Yuan, D.; Chen, D. G.; Ng, R. H.; Wang, K.; Choi, J.; Li, S.; Hong, S.; Zhang, R.; Xie, J., et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell. 2022;185,881-895 e820.

- Le Voyer, T.; Parent, A. V.; Liu, X.; Cederholm, A.; Gervais, A.; Rosain, J.; Nguyen, T.; Perez Lorenzo, M.; Rackaityte, E.; Rinchai, D., et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in humans with alternative NF-kappaB pathway deficiency. Nature. 2023;623,803-813.

- Bastard, P.; Vazquez, S. E.; Liu, J.; Laurie, M. T.; Wang, C. Y.; Gervais, A.; Le Voyer, T.; Bizien, L.; Zamecnik, C.; Philippot, Q., et al. Vaccine breakthrough hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia in patients with auto-Abs neutralizing type I IFNs. Sci Immunol. 2023;8,eabp8966.

- Philippot, Q.; Fekkar, A.; Gervais, A.; Le Voyer, T.; Boers, L. S.; Conil, C.; Bizien, L.; de Brabander, J.; Duitman, J. W.; Romano, A.; et al. Autoantibodies Neutralizing Type I IFNs in the Bronchoalveolar Lavage of at Least 10% of Patients During Life-Threatening COVID-19 Pneumonia. J Clin Immunol 2023, 43, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghia, E. M.; Jain, S.; Widhopf, G. F.; Rassenti, L. Z.; Keating, M. J.; Wierda, W. G.; Gribben, J. G.; Brown, J. R.; Rai, K. R.; Byrd, J. C.; et al. Use of IGHV3-21 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with high-risk disease and reflects antigen-driven, post-germinal center leukemogenic selection. Blood 2008, 111, 5101–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, A.; Marchal, A.; Fortova, A.; Berankova, M.; Krbkova, L.; Pychova, M.; Salat, J.; Zhao, S.; Kerrouche, N.; Le Voyer, T.; et al. Autoantibodies neutralizing type I IFNs underlie severe tick-borne encephalitis in approximately 10% of patients. J Exp Med 2024, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.; Yang, E. Y.; Moore, A. R.; Dhingra, S.; Chang, S. E.; Yin, X.; Pi, R.; Mack, E. K.; Volkel, S.; Gessner, R., et al. Autoantibodies are highly prevalent in non-SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infections and critical illness. JCI Insight. 2023;8.

- Hale, B. G. Autoantibodies targeting type I interferons: Prevalence, mechanisms of induction, and association with viral disease susceptibility. Eur J Immunol 2023, 53, e2250164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J. E.; Rosen, L. B.; Csomos, K.; Rosenberg, J. M.; Mathew, D.; Keszei, M.; Ujhazi, B.; Chen, K.; Lee, Y. N.; Tirosh, I.; et al. Broad-spectrum antibodies against self-antigens and cytokines in RAG deficiency. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 4135–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikova, E.; Reshkova, V.; Kumanova capital A, C.; Raleva, S.; Alexandrova, D.; Capo, N.; Murovska, M.; On Behalf Of The European Network On Me/Cfs, E. Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and human herpesvirus-6 infections in patients with myalgic small ie, Cyrillicncephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 3682–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J. H.; Kim, K. H.; Jeong, S. H.; Park, J. W.; Lee, S. M.; Seo, Y. H. Comparison of sputum and nasopharyngeal swabs for detection of respiratory viruses. J Med Virol 2014, 86, 2122–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lion, T. Adenovirus persistence, reactivation, and clinical management. FEBS Lett 2019, 593, 3571–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnett, C. T.; Erdman, D.; Xu, W.; Gooding, L. R. Prevalence and quantitation of species C adenovirus DNA in human mucosal lymphocytes. J Virol 2002, 76, 10608–10616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lion, T. Adenovirus infections in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014, 27, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosulin, K.; Haberler, C.; Hainfellner, J. A.; Amann, G.; Lang, S.; Lion, T. Investigation of adenovirus occurrence in pediatric tumor entities. J Virol 2007, 81, 7629–7635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgin, H. W.; Wherry, E. J.; Ahmed, R. Redefining chronic viral infection. Cell 2009, 138, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.; Schneider, W. M.; Hoffmann, H. H.; Yarden, G.; Busetto, A. G.; Manor, O.; Sharma, N.; Rice, C. M.; Schreiber, G. Multifaceted activities of type I interferon are revealed by a receptor antagonist. Sci Signal 2014, 7, ra50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, Y. J.; Stetson, D. B. The type I interferonopathies: 10 years on. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, C.; Wang, L. MAVS: The next STING in cancers and other diseases. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2024, 207, 104610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, S.; Watanabe, T.; Hara, Y.; Arata, M.; Uddin, M. K.; Mantoku, K.; Sago, K.; Yanagi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Masud, H., et al. A STING inhibitor suppresses EBV-induced B cell transformation and lymphomagenesis. Cancer Sci. 2021;112,5088-5099.

- Pasquesi, G. I. M.; Allen, H.; Ivancevic, A.; Barbachano-Guerrero, A.; Joyner, O.; Guo, K.; Simpson, D. M.; Gapin, K.; Horton, I.; Nguyen, L. L., et al. Regulation of human interferon signaling by transposon exonization. Cell. 2024;187,7621-7636 e7619.

- Peluso, M. J.; Deeks, S. G. Mechanisms of long COVID and the path toward therapeutics. Cell. 2024;187,5500-5529.

- Kosulin, K.; Geiger, E.; Vecsei, A.; Huber, W. D.; Rauch, M.; Brenner, E.; Wrba, F.; Hammer, K.; Innerhofer, A.; Potschger, U., et al. Persistence and reactivation of human adenoviruses in the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22,381 e381-381 e388.

- Alvarez-Cardona, J. J.; Whited, L. K.; Chemaly, R. F. Brincidofovir: understanding its unique profile and potential role against adenovirus and other viral infections. Future Microbiol. 2020;15,389-400.

- El-Haddad, D.; El Chaer, F.; Vanichanan, J.; Shah, D. P.; Ariza-Heredia, E. J.; Mulanovich, V. E.; Gulbis, A. M.; Shpall, E. J.; Chemaly, R. F. Brincidofovir (CMX-001) for refractory and resistant CMV and HSV infections in immunocompromised cancer patients: A single-center experience. Antiviral Res. 2016;134,58-62.

- Camargo, J. F.; Morris, M. I.; Abbo, L. M.; Simkins, J.; Saneeymehri, S.; Alencar, M. C.; Lekakis, L. J.; Komanduri, K. V. The use of brincidofovir for the treatment of mixed dsDNA viral infection. J Clin Virol 2016, 83, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J. A.; Nichols, W. G.; Marty, F. M.; Papanicolaou, G. A.; Brundage, T. M.; Lanier, R.; Zerr, D. M.; Boeckh, M. J. Oral brincidofovir decreases the incidence of HHV-6B viremia after allogeneic HCT. Blood 2020, 135, 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosulin, K. Intestinal HAdV Infection: Tissue Specificity, Persistence, and Implications for Antiviral Therapy. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radke, J. R.; Cook, J. L. Human adenovirus infections: update and consideration of mechanisms of viral persistence. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018, 31, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Calcedo, R.; Medina-Jaszek, A.; Keough, M.; Peng, H.; Wilson, J. M. Adenoviruses in lymphocytes of the human gastro-intestinal tract. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimley, M. S.; Maron, G., editors. Preliminary Results of a Phase 2a Clinical Trial to Evaluate Safety, Tolerability and Antiviral Activity of Intravenous Brincidofovir (BCV IV) in Immunocompromised Patients with Adenovirus Infection. 65th ASH Annual Meeting; 2023; San Diego, CA: Blood, 142,112-113.

Figure 1.

Overview of PCR positive HAdV, EBV, HHV6, CMV and SARS-CoV-2 in sputum from the 29 participants in the study. Red squares represent samples with virus present. Green squares represent samples with no virus detected.

Figure 1.

Overview of PCR positive HAdV, EBV, HHV6, CMV and SARS-CoV-2 in sputum from the 29 participants in the study. Red squares represent samples with virus present. Green squares represent samples with no virus detected.

Figure 2A.

EBV (copies/ml) in sputum from the 5 participant groups, 1 HD = Healthy donors (green dots, n=10), 2 ME/CFS patients (red dots, n=13), 3 SENIOR healthy controls (blue dots, n=4), 4 POS CTR=Positive control, 5 NEG CTR=Negative control . Data are presented as boxplots with median values and outliers. Statistically significant difference was found between the HD and ME/CFS groups (p=0.0256) according to non-parametric Wilcoxon rank procedure.

Figure 2A.

EBV (copies/ml) in sputum from the 5 participant groups, 1 HD = Healthy donors (green dots, n=10), 2 ME/CFS patients (red dots, n=13), 3 SENIOR healthy controls (blue dots, n=4), 4 POS CTR=Positive control, 5 NEG CTR=Negative control . Data are presented as boxplots with median values and outliers. Statistically significant difference was found between the HD and ME/CFS groups (p=0.0256) according to non-parametric Wilcoxon rank procedure.

Figure 2B.

HHV6 (copies/ml) in sputum from the 5 participant groups, 1 HD = Healthy donors (green dots, n=10), 2 ME/CFS patients (red dots, n=13), 3 SENIOR healthy controls (blue dots, n=4), 4 POS CTR=Positive control, 5 NEG CTR=Negative control. Data are presented as boxplots with median values and outliers. Statistically significant difference in HHV6 concentration was not found (ns, non-significant) between the HD and ME/CFS groups according to non-parametric Wilcoxon rank procedure.

Figure 2B.

HHV6 (copies/ml) in sputum from the 5 participant groups, 1 HD = Healthy donors (green dots, n=10), 2 ME/CFS patients (red dots, n=13), 3 SENIOR healthy controls (blue dots, n=4), 4 POS CTR=Positive control, 5 NEG CTR=Negative control. Data are presented as boxplots with median values and outliers. Statistically significant difference in HHV6 concentration was not found (ns, non-significant) between the HD and ME/CFS groups according to non-parametric Wilcoxon rank procedure.

Figure 3.

AutoAbs to type I interferon (IFN-I) in sputum from the 5 participant groups. 1 HD = Healthy donors (green dots, n=10), 2 ME/CFS patients (red dots, n=13), 3 SENIOR healthy controls (blue dots, n=4), 4 POS CTR=Positive control, 5 NEG CTR=Negative control. Data are presented as boxplots with median values quartiles. Statistically significant difference in HHV6 concentration was not found (ns, non-significant) between the HD and ME/CFS groups according to non-parametric Wilcoxon rank procedure.

Figure 3.

AutoAbs to type I interferon (IFN-I) in sputum from the 5 participant groups. 1 HD = Healthy donors (green dots, n=10), 2 ME/CFS patients (red dots, n=13), 3 SENIOR healthy controls (blue dots, n=4), 4 POS CTR=Positive control, 5 NEG CTR=Negative control. Data are presented as boxplots with median values quartiles. Statistically significant difference in HHV6 concentration was not found (ns, non-significant) between the HD and ME/CFS groups according to non-parametric Wilcoxon rank procedure.

Table 1.

Sample Id, duration of ME/CFS, disease severity, sex and age of the participants.

Table 1.

Sample Id, duration of ME/CFS, disease severity, sex and age of the participants.

| |

ME/CFS patients |

|

Healthy controls |

|

Senior controls |

|

| Sample |

Duration of |

Disease |

Sex |

Age |

|

Sample |

Duration of |

Sex |

Age |

|

Sample |

Duration of |

Sex |

Age |

|

| Id |

ME/CFS (yrs) |

Severity |

|

yrs |

|

Id |

ME/CFS (yrs) |

|

yrs |

|

Id |

ME/CFS (yrs) |

|

yrs |

|

| 1 |

8 |

1 |

F |

61 |

|

14 |

NA |

F |

56 |

|

24 |

NA |

F |

65 |

|

| 2 |

13 |

2 |

F |

60 |

|

15 |

NA |

F |

33 |

|

25 |

NA |

M |

77 |

|

| 3 |

10 |

2 |

F |

58 |

|

16 |

NA |

F |

61 |

|

26 |

NA |

F |

72 |

|

| 4 |

12 |

1 |

F |

56 |

|

17 |

NA |

F |

61 |

|

27 |

NA |

M |

75 |

|

| 5 |

28 |

1 |

F |

54 |

|

18 |

NA |

F |

37 |

|

Mean |

|

|

72,3 |

|

| 6 |

12 |

1 |

F |

54 |

|

19 |

NA |

F |

49 |

|

Range |

|

|

65 - 77 |

|

| 7 |

10 |

1 |

F |

53 |

|

20 |

NA |

F |

66 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

14 |

1 |

F |

49 |

|

21 |

NA |

M |

48 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

14 |

2 |

F |

48 |

|

22 |

NA |

F |

33 |

|

Positive, negative control |

|

| 10 |

8 |

1 |

F |

37 |

|

23 |

NA |

F |

66 |

|

Sample |

Duration of |

Sex |

Age |

|

| 11 |

17 |

2 |

F |

37 |

|

Mean |

|

|

51 |

|

Id |

ME/CFS (yrs) |

|

yrs |

|

| 12 |

12 |

3 |

F |

22 |

|

Range |

|

|

33 - 66 |

|

P7 |

NA |

F |

46 |

|

| 13 |

27 |

1 |

F |

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

L59 |

NA |

F |

54 |

|

| Mean |

14,2 |

|

|

49,8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mean |

|

|

65,9 |

|

| Range |

8- 28 |

|

|

22 - 61 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Range |

|

|

46 - 54 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).