Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

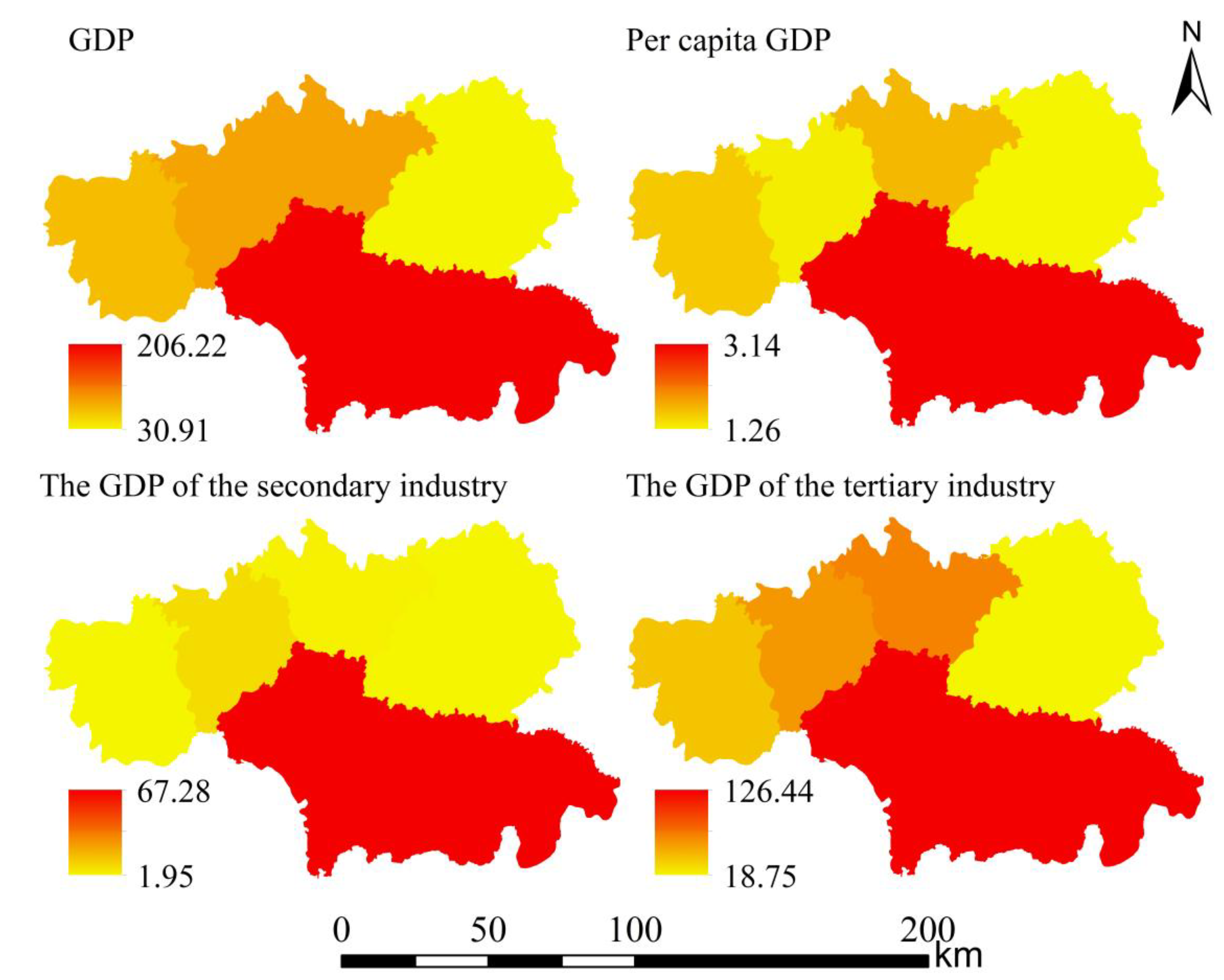

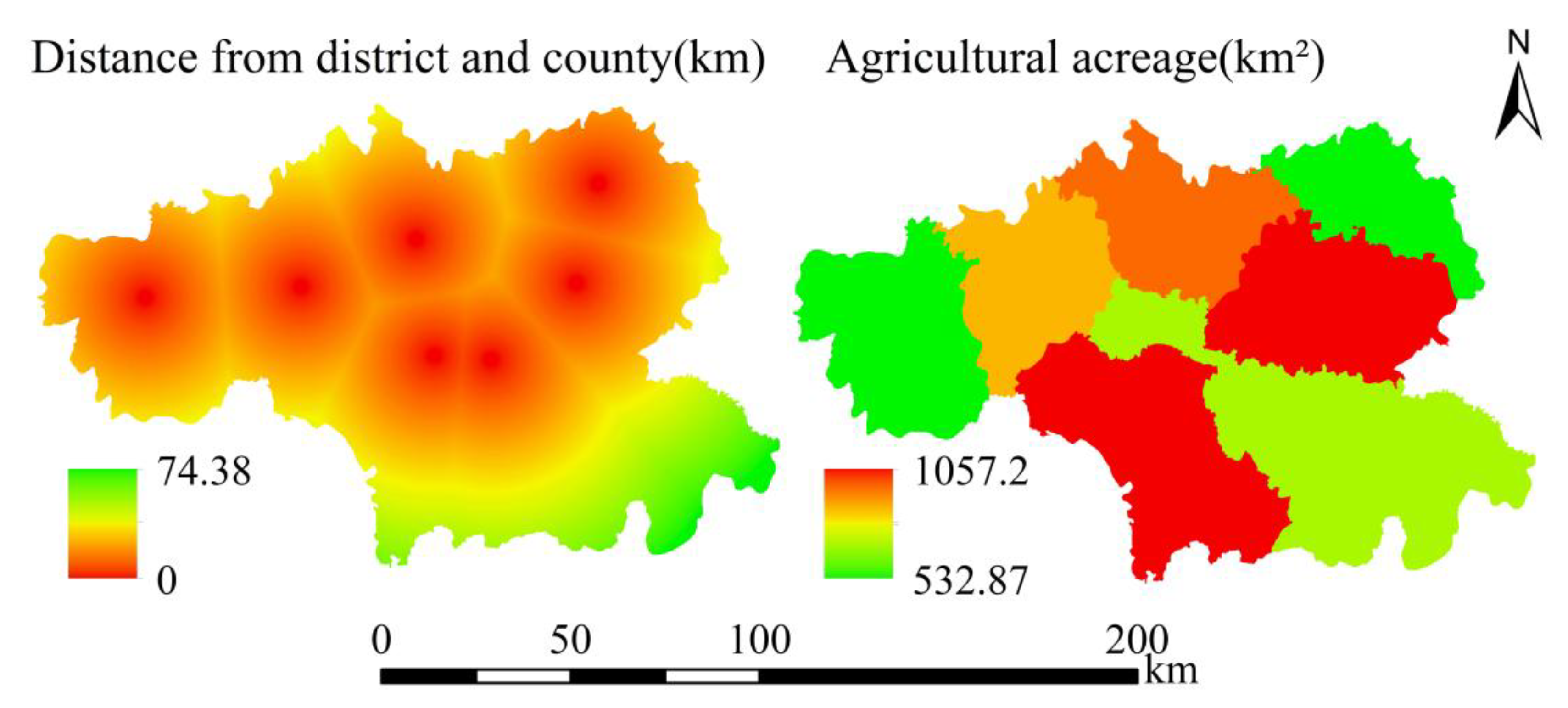

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

2.3. Research Methodology

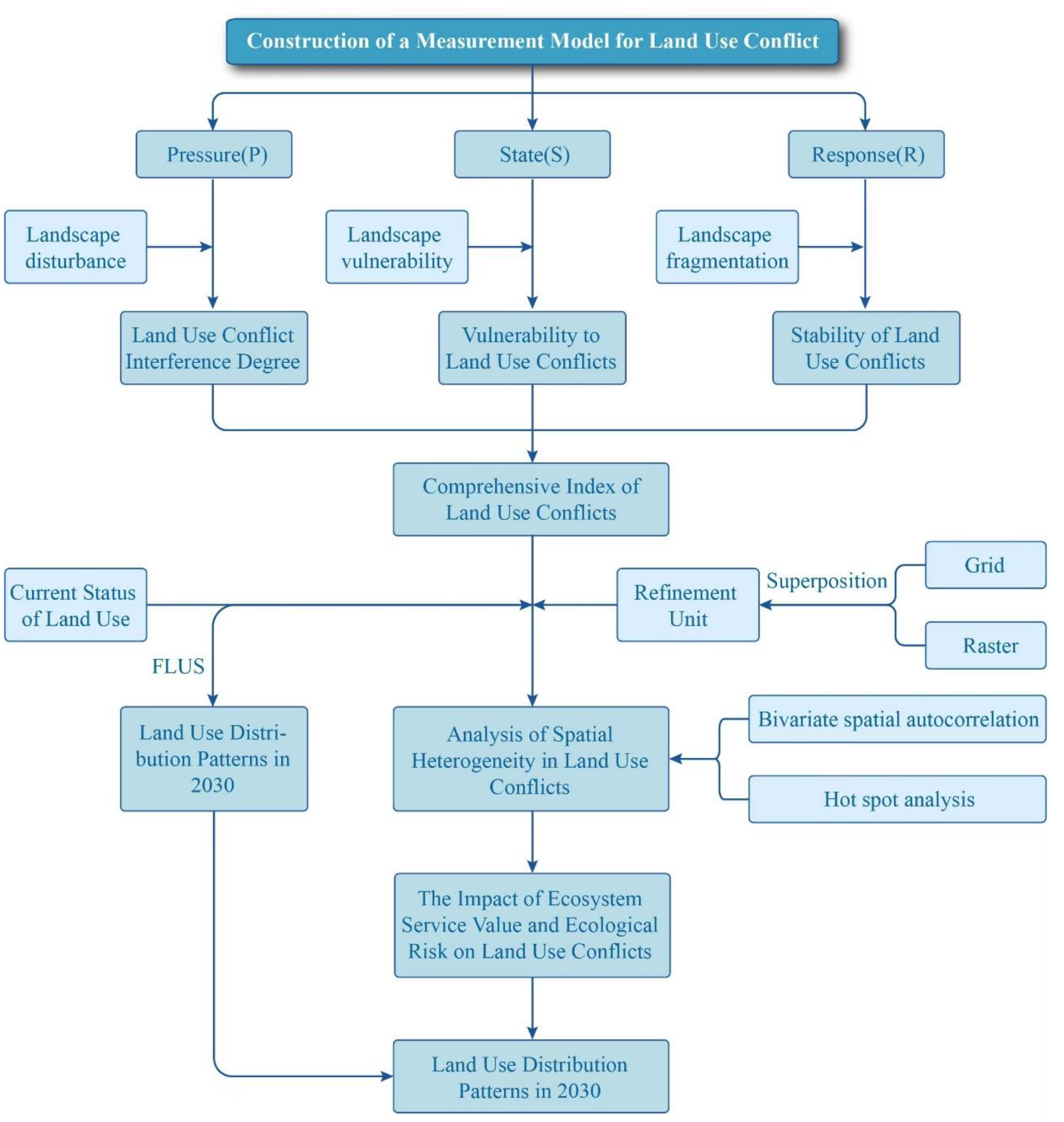

2.3.1. Construction of the Land Use Conflict Measurement Model

2.3.2. Modeling and Forecasting the Spatial Distribution of Land Use Conflicts

2.4. Ecological Risk Assessment System

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Land Use Conflicts and Their Ecological Implications

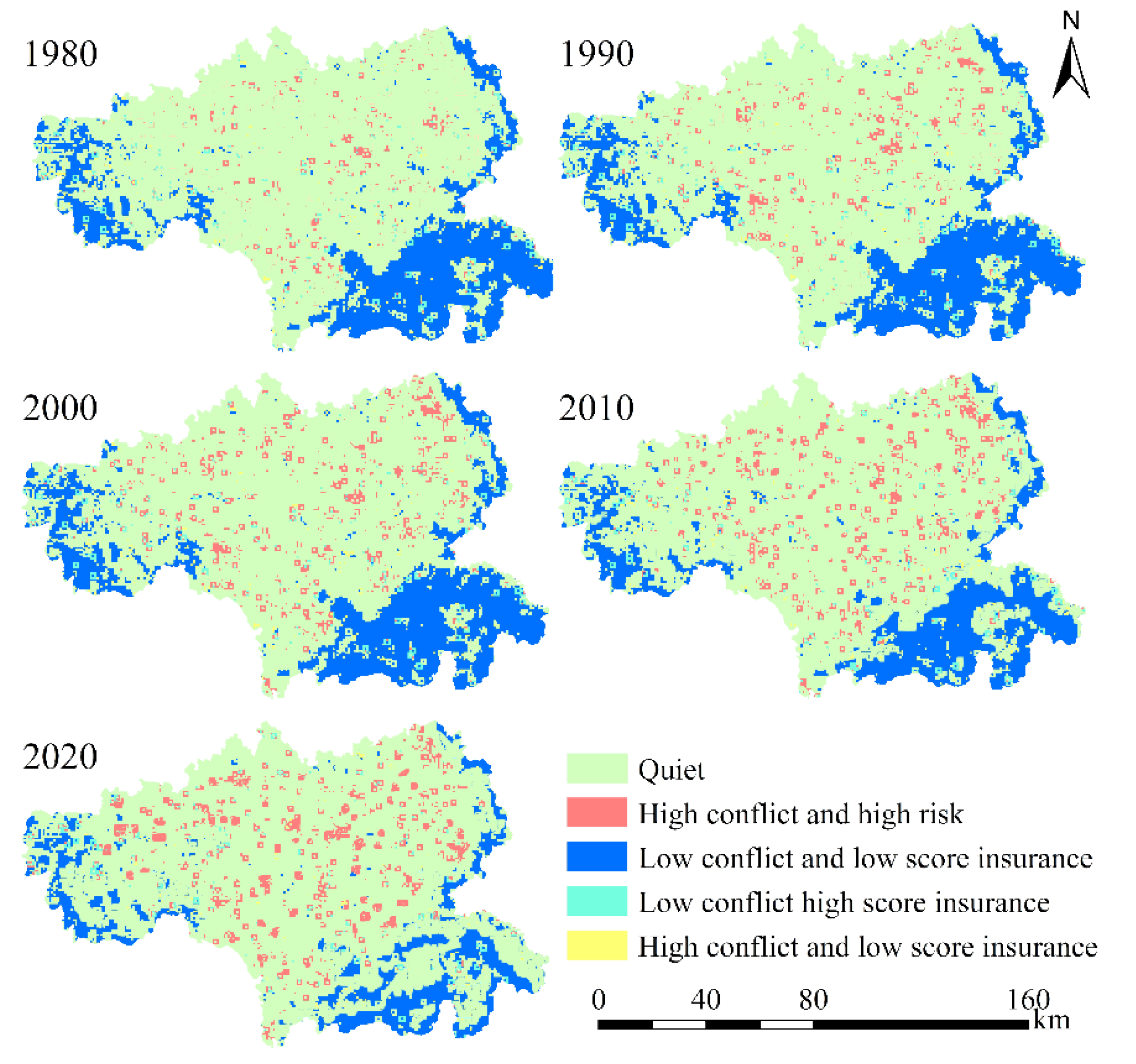

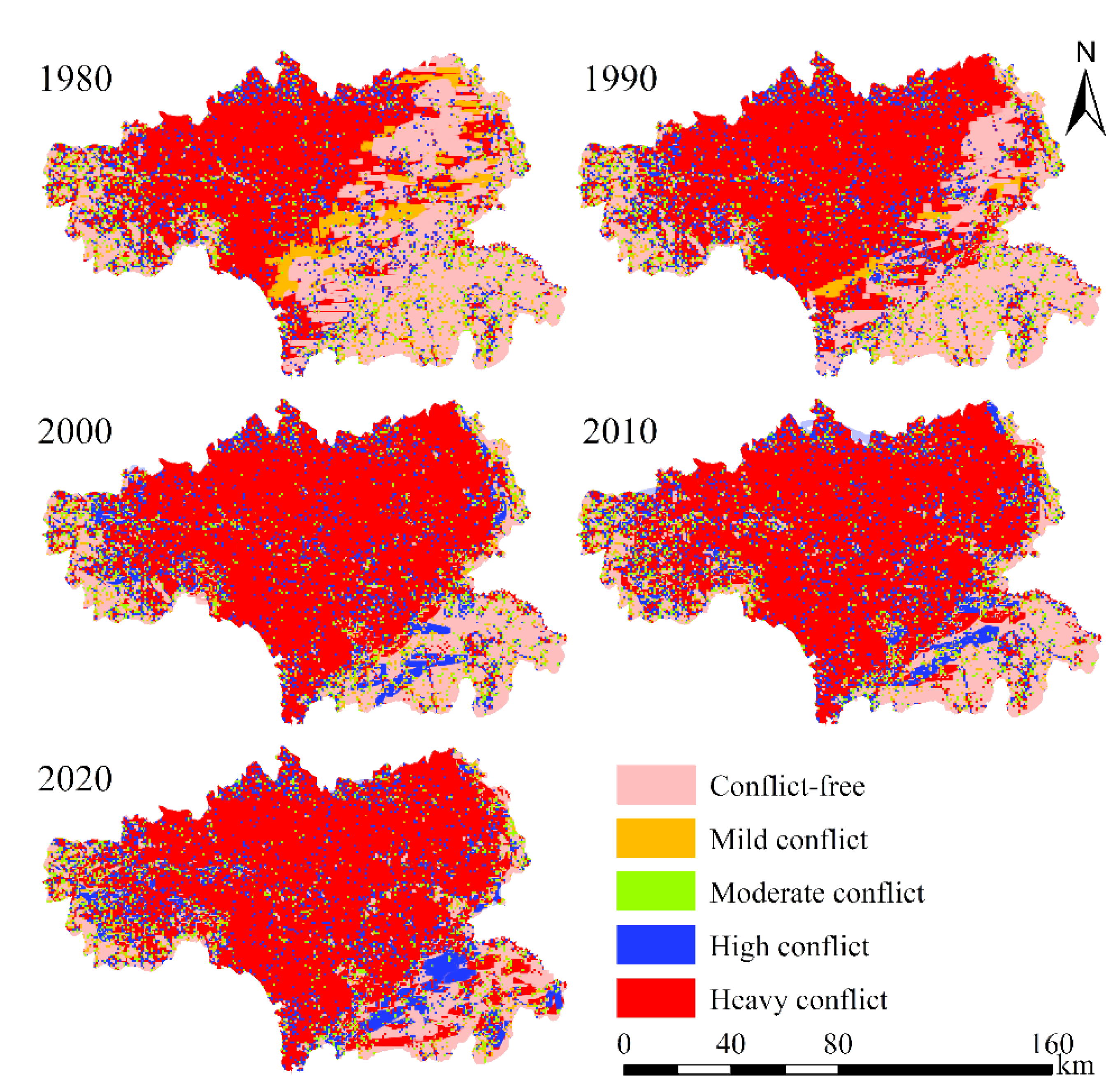

3.1.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Patterns of Land Use Conflicts

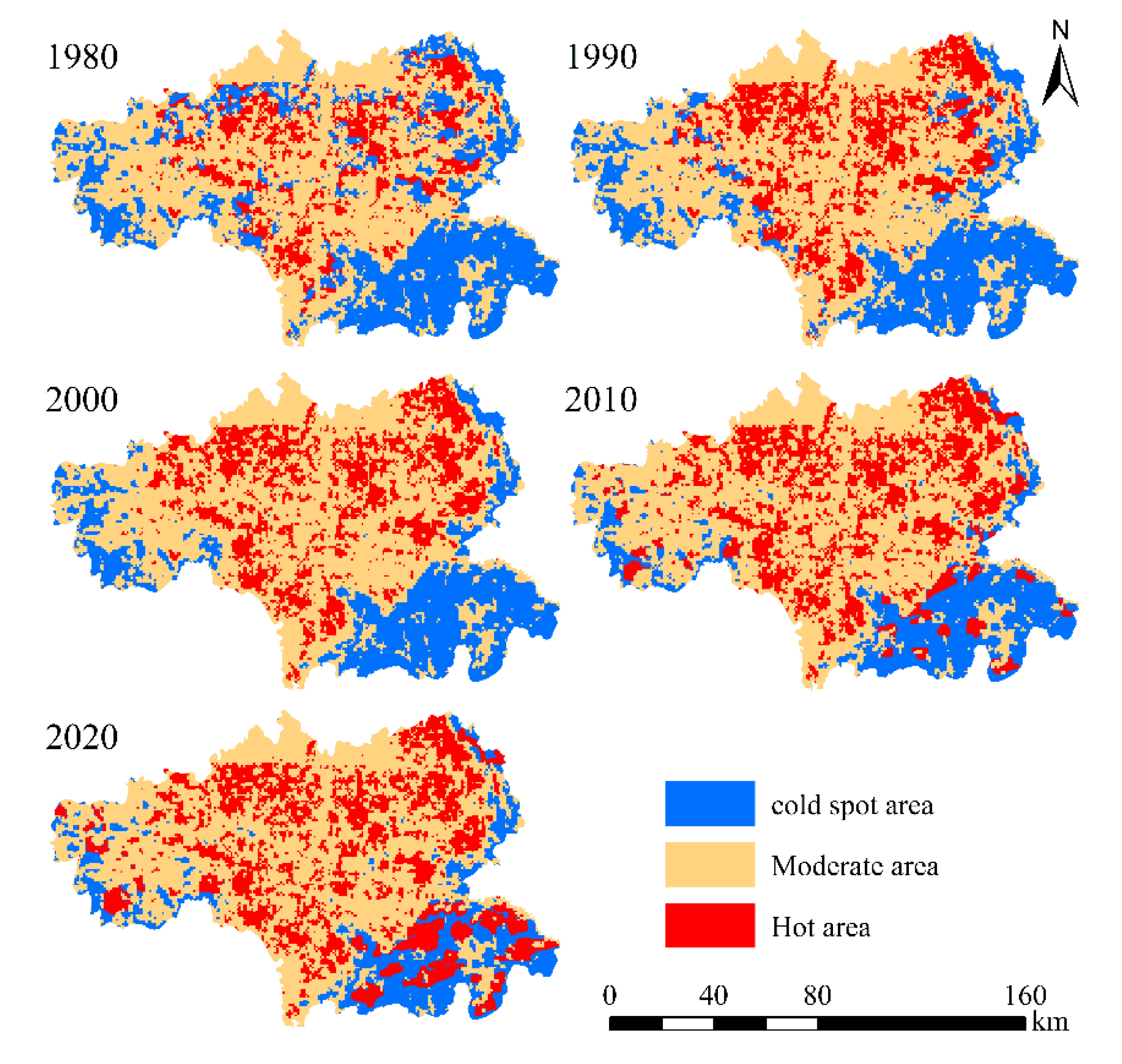

3.1.2. Analysis of Spatial Heterogeneity in Land Use Conflict Patterns

| Year | Fitting Model | Nugget (C0) |

Still (C0+C) |

Nugget/Still C0/C0+C |

Range(A0) | Coefficient of determinationt (R2) |

Residual RSS/10-7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Gauss | 0.0011 | 0.0037 | 0.2972 | 1345 | 0.8234 | 8.3421 |

| 1990 | Gauss | 0.0013 | 0.0053 | 0.2452 | 1457 | 0.8345 | 7.6421 |

| 2000 | Exponential | 0.0021 | 0.0058 | 0.3620 | 2109 | 0.9024 | 5.4534 |

| 2010 | Gauss | 0.0023 | 0.0061 | 0.3770 | 2345 | 0.9213 | 4.1758 |

| 2020 | Gauss | 0.0034 | 0.0073 | 0.4657 | 1597 | 0.8345 | 2.1896 |

3.1.3. Responses of Ecological Risks to Land Use Conflict

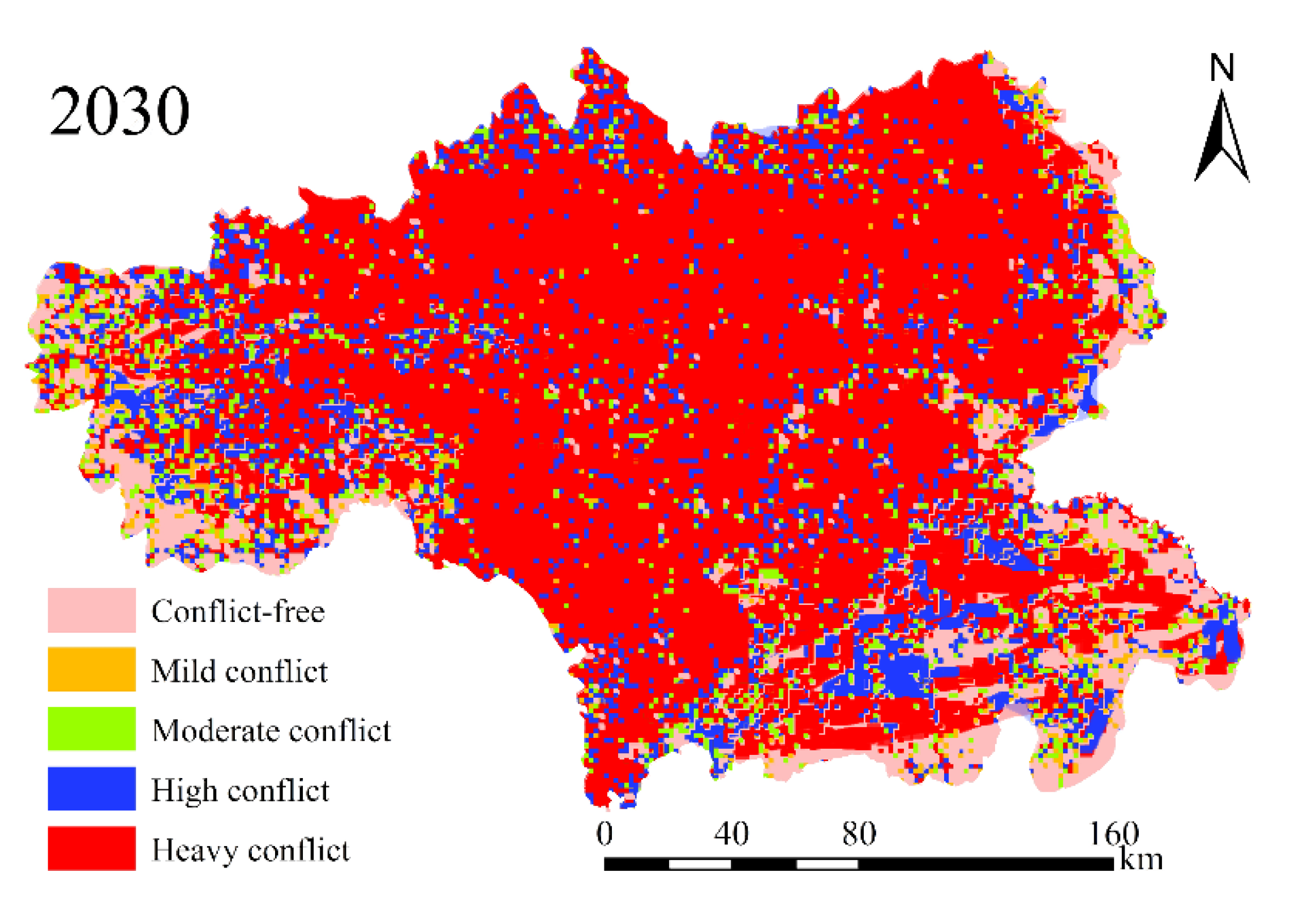

3.2. Spatiotemporal Prediction and Simulation of Land Use Conflicts

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Land Use Conflicts

4.2. Drivers of Spatial Heterogeneity and Temporal Dynamics

4.4. Implications for Policy and Management

4.5. Methodological Advancements and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, D.; Wang, M.; Zheng, W.; Song, Y.; Huang, X. A multi-level spatial assessment framework for identifying land use conflict zones. Land Use Policy 2025, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, S.; Xu, S.; Huang, J.; Ren, Y.; Song, C. Distribution patterns and driving mechanisms of land use spatial conflicts: Empirical analysis from counties in China. Habitat Int 2025, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.M.S.; Schilling, J.; Bossenbroek, L.; Ezzayyat, R.; Berger, E. Drivers of conflict over customary land in the Middle Draa Valley of Morocco. World Dev 2025, 188. [Google Scholar]

- Su, R.; Song, G.; Wang, Q. Identification and Driving Effects of Land Use Conflicts in Mega-City in Northeast China: A Case Study of Shenyang City. Pol J Environ Stud 2025, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amare, M.; Abay, K.A.; Berhane, G.; Andam, K.S.; Adeyanju, D. Conflicts, crop choice, and agricultural investments: Empirical evidence from Nigeria. Land Use Policy 2025, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, R.; Lamoureux, B. Understanding "public" framings of private places and psychological ownership in a rural land use conflict. J Rural Stud 2025, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, C.; Sun, W.; Xing, H.; Feng, C.; Su, Q. Impact of civil war on the land cover in Myanmar. Environ Monit Assess 2025, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, R.; Yang, J.; Xie, X.; Cui, X. Decoding Land Use Conflicts: Spatiotemporal Analysis and Constraint Diagnosis from the Perspectives of Production-Living-Ecological Functions. Land-Basel, 2024; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W. Land-Use Conflict Dynamics, Patterns, and Drivers under Rapid Urbanization. Land-Basel, 2024; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Guo, B.; Su, H.; Liu, Z. Study on multi-scenarios regulating strategy of land use conflict in urban agglomerations under the perspective of "three-zone space": a case study of Harbin-Changchun urban agglomerations, China. Front Env Sci-Switz, 2024; 11. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Dai, J.; Chen, L.; Song, Y. The Identification of Land Use Conflicts and Policy Implications for Donghai County Based on the "Production-Living-Ecological" Functions. Land-Basel, 2024; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Q. Identification of Land Use Conflict Based on Multi-Scenario Simulation-Taking the Central Yunnan Urban Agglomeration as an Example. Sustainability-Basel, 2024; 16. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.; Hu, X.; Huang, Z.; Wei, M. Identifying the Optimal Scenario for Reducing Land-Use Conflicts in Regional Development. Land-Basel, 2024; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Li, H.; Lei, S.; Tong, Z.; Wang, N. A novelty modeling approach to eliminate spatial conflicts and ecological barriers in mining areas of a resource-based city. Ecol Indic 2024, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhai, J.; Zhai, B.; Qu, Y. Understanding the "conflict-coordination" theoretical model of regional land use transitions: Empirical evidence from the interconversion between cropland and rural settlements in the lower yellow river, China. Habitat Int 2024, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Sun, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, K.; Yuan, C. Identification of Potential Land Use Conflicts in Shandong Province: A New Framework. Land-Basel, 2024; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Kang, J.; Wang, Y. Land Use Conflicts Identification and Multi-Scenario Simulation in Mountain Cities, Southwest China: A Coupled Structural and Functional Perspective. Land Degrad Dev 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Cao, W.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J. Multi-scenario land use prediction and layout optimization in Nanjing Metropolitan Area based on the PLUS model. J Geogr Sci 2024, 34, 1415–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, A. Identification of land use conflicts and dynamic response analysis of Natural-Social factors in rapidly urbanizing areas- a case study of urban agglomeration in the middle reaches of Yangtze River. Ecol Indic 2024, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Cai, H.; Chen, L. Concept and Method of Land Use Conflict Identification and Territorial Spatial Zoning Control. Sustainability-Basel, 2024; 16. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, S.; Xu, S.; Jiang, X.; Song, C. Identification and dynamic evolution of land use conflict potentials in China, 2000-2020. Ecol Indic 2024, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, C.; He, X.; Zhou, C.; Wang, H. Nonlinear Effects of Land-Use Conflicts in Xinjiang: Critical Thresholds and Implications for Optimal Zoning. Land-Basel, 2024; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Tavares, T.; Blanco, J.L.Y.; Pascual, C. Dispossessed lands and land-use change in the Colombian armed conflict: Exploring a link through a regional case study. J Rural Stud 2024, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Wei, Y.; Dai, Z.; Xu, W.; Wang, X.; Duan, J.; Zou, L.; Zhao, G.; Ren, X.; Feng, Y. Landscape ecological risk assessment and its driving factors in the Weihe River basin, China. J Arid Land 2024, 16, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseer, T.; Salifu, K.; Yiridomoh, G.Y. Land use practices and farmer-herder conflict in Agogo: dynamics of traditional authority and resistance. Third World Q 2024, 45, 1238–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, E.U.; Akase, T.M. Out of Frame: Invisibilisation of Non-Human Nature in Media Framing of a Land Conflict Transformation Policy in Nigeria. Afr Journal Stud 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudapakati, C.P.; Bandauko, E.; Chaeruka, J.; Arku, G. Peri-urbanisation and land conflicts in Domboshava, Zimbabwe. Land Use Policy 2024, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrizal; Putra, E. V.; Elida, L. Palm oil expansion, insecure land rights, and land-use conflict: A case of palm oil centre of Riau, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2024; Volume 146. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Sun, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, G.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, H. The progression traits of spatial conflicts within the production-living-ecological space among varying geomorphological types of mountain-basin areas in karst regions, China. Ecol Indic 2024, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furumo, P.R.; Yu, J.; Hogan, J.A.; Tavares De Carvalho, L.M.; Brito, B.; Lambin, E.F. Land conflicts from overlapping claims in Brazil's rural environmental registry. P Natl Acad Sci Usa 2024, 121, e1887610175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richetta, C.; Wegenast, T. Access denied: Land alienation and pastoral conflicts. J Peace Res 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, A.M.; Amsalu, T.B.; Dadi, T.T. Communal Grazing Land Distribution and Land Use Conflict in East Gojjam Zone: Insight From Baso Liben District, North-Western Ethiopia. J Asian Afr Stud 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, L.; Mohr, B.; Dinc, P. Cropland abandonment in the context of drought, economic restructuring, and migration in northeast Syria. Environ Res Lett 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, R.; Chopin, P.; Verburg, P.H. Supporting spatial planning with a novel method based on participatory Bayesian networks: An application in Curaçao. Environ Sci Policy 2024, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhao, X.; Li, P.; Jin, F.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Wang, J. Assessing territorial space conflicts in the coastal zone of Wenzhou, China: A land-sea interaction perspective. Sci Total Environ 2024, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurmessa, M.M.; Moisa, M.B.; Tesso, G.J.; Erena, M.G. Impacts of land use land cover change on Leopard (Panthera pardus) habitat suitability and its effects on human wildlife conflict in Hirkiso forest, Sibu Sire District, Western Ethiopia. All Earth 2024, 36, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Peng, S.; Ma, X.; Lin, Z.; Ma, D.; Shi, S.; Gong, L.; Huang, B. Identification of potential conflicts in the production-living-ecological spaces of the Central Yunnan Urban Agglomeration from a multi-scale perspective. Ecol Indic 2024, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Rotich, B.; Czimber, K. Assessment of the environmental impacts of conflict-driven Internally Displaced Persons: A sentinel-2 satellite based analysis of land use/cover changes in the Kas locality, Darfur, Sudan. Plos One 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Chen, S.; Dong, X.; Wang, K.; He, T.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Ye, Y.; Xiao, W. Revealing conflict risk between landscape modification and species conservation in the context of climate change. J Clean Prod 2024, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y. Accurate identification and trade-off analysis of multifunctional spaces of land in megacities: A case study of Guangzhou city, China. Habitat Int 2024, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Li, M.; Huang, X.; Lei, C.; Wang, H. Evaluation of spatial conflicts of land use and its driving factors in arid and semiarid regions: A case study of Xinjiang, China. Ecol Indic 2024, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Kang, J.; Wang, Y. Exploring the Coupling Relationship and Driving Factors of Land Use Conflicts and Ecosystem Services Supply-Demand Balances in Different Main Functional Areas, Southwest China. Land Degrad Dev 2024, 35, 5237–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, M.; Elagib, N.A. Armed conflict as a catalyst for increasing flood risk. Environ Res Lett 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesecker, J.M.; Evans, J.S.; Oakleaf, J.R.; Dropuljic, K.Z.; Vejnovic, I.; Rosslowe, C.; Cremona, E.; Bhattacharjee, A.L.; Nagaraju, S.K.; Ortiz, A.; et al. Land use and Europe's renewable energy transition: identifying low-conflict areas for wind and solar development. Front Env Sci-Switz, 2024; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, E.H. Settlement growth and military conflict in early colonial New England 1620-1700. Eur J Law Econ 2024, 57, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutiyo, S. The struggle for land by indigenous groups: from conflict to cooperation in Kasepuhan Ciptagelar, Indonesia. Community Dev J 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syaban, A.S.N.; Appiah-Opoku, S. Unveiling the Complexities of Land Use Transition in Indonesia's New Capital City IKN Nusantara: A Multidimensional Conflict Analysis. Land-Basel, 2024; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Tang, M.; Huang, J.; Mei, X.; Zhao, H. Driving mechanisms and multi-scenario simulation of land use change based on National Land Survey Data: a case in Jianghan Plain, China. Front Env Sci-Switz, 2024; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, S.; Yang, F.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y. An integrated model chain for diagnosing and predicting conflicts between production-living-ecological space in lake network regions: A case of the Dongting Lake region, China. Ecol Indic 2024, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M.; Charnley, S.; Martin, J.V.; Epstein, K. Large, rugged and remote: The challenge of wolf-livestock coexistence on federal lands in the American West. People Nat 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Conflict-free | Mild conflict | Moderate conflict | High conflict | Heavy confict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.91 |

| 1990 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| 2000 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.96 | 0.86 |

| 2010 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| 2020 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).