1. Introduction

The sloshing phenomenon generally occurs in partially filled tanks with accelerated movement, e.g., liquid cargo ships in non-fully loaded navigation, moving oil tank transporters, elevated water towers perturbed by ground motion, and road vehicle tanks [2,3]. This non-linear phenomenon can lead to spillage of the transported liquid or, in the worst case, to damage to the container [4]. If the forcing lasts long enough, the sloshing intensity can cause significant compressive forces on the container walls and may be a source of destabilization or failure, especially if the forcing frequency is equal to the system’s natural frequency. Therefore, rapid stabilization or wave damping is crucial to avoid disasters.

Several techniques have been developed to control sloshing and reduce the stresses on container walls. For example, through a series of controlled and detailed experiments, [5] demonstrated the effectiveness of four different vertical baffle configurations to dampen the effects of sloshing and suppress the pressure on walls due to breaking waves. With the same purpose, but through numerical analysis, [6] studied the effect of damping on the sloshing pressure under resonance conditions by placing two baffles in a partially filled rectangular tank. Different heights and/or distances between the baffles were tested and gave good results. Following the same objective, [7] proposed a new configuration that consists of placing a horizontal perforated plate inside a container, which significantly reduces the wave amplitude and controls the sloshing. [8] improved the method by placing horizontal baffles of different lengths, porosity, and depths. They found that sloshing tends to decrease with an increase in porosity. The energy loss is mainly due to the generation of eddies when they pass through the pores.

Therefore, the effectiveness of energy dissipation by baffles in containers is clear. Moreover, it has been shown that the oscillation amplitude of the free surface depends on the viscosity. [3] found through their experiments in a 70% filled tank that the higher the liquid viscosity, the greater the reduction in sloshing pressure and splashing. They showed that for highly viscous fluids, friction with the container walls dissipates most of the energy. In addition, using numerical and experimental modeling, [9] demonstrated that for highly viscous liquids, the energy is mainly dissipated by the wall boundary layers. Therefore, sloshing is significantly lower with glycerin than with water. Viscosity can also be used to damp sloshing when used as a thin layer on the free surface of water. In this way, [10] performed experiments with two non-miscible liquid layers, that is, a layer of water in a partially filled reservoir covered by an upper layer of oil with a higher viscosity. When the depth of the water is 10 cm and the thickness of the oil layer is equal to 5 cm, the free surface is more stable than with a single layer of water and more stable when the upper layer is 2.5 cm thick.

Antisloshing by floating liquid foams is a technique proposed for the same purpose. [11,12] studied experimentally the influence of a liquid foam layer on sloshing. Their results show that a sufficiently thick foam layer (5 layers of bubbles) increases the damping coefficient and reduces the amplitude of free surface oscillations. By using an analytical model, they demonstrated that the dissipation of the sloshing energy is mainly due to the bubbles close to the walls. Based on [12]’s work, [4] proposed to place uniform-diameter solid spherical foams on the fluid surface to minimize sloshing. Through a series of experiments, they demonstrated that the effect of 1 to 4 layers of solid foam proportionally reduces the amplitude of the natural frequency at the free surface of a rectangular tank. They concluded that the energy dissipation of the sloshing is due to friction between neighboring spheres.

The works mentioned above are only a small part of the vast literature available on techniques to minimize sloshing-induced loads. However, most of them involve specialized engineering work and can be costly, especially for large containers. Recently, [1] reported experiments performed in two identical containers under different conditions. In the first configuration, the container was coated with a hydrophobic solution, while in the other it was uncoated. They performed measurements using different modes of excitation relating to the natural frequency of the tank and three water levels (low, medium, and high). Their analysis was done for long excitation times. In the case of the intermediate level, the wall sloshing pressure load is reduced by up to , while no significant reduction was observed for low and high levels. They concluded that hydrophobic surfaces lead to a reduction in the loads sloshing onto the container walls and reduce wave breaking.

Based on [1] results, we present here an experimental study of sloshing in two configurations: when the containers are uncoated and when the containers’ walls are coated with hydrophobic oil. As described in

Section 2, all containers are filled with

of water and eight different values for the aspect ratio of the containers are considered.

Section 3 shows how video processing allows extraction of the water-free surface as a function of time. Moreover, containers are subject to two regimes: a periodically forced regime which leads to results reported in

Section 4, and a damping regime after the external forcing is suddenly stopped (see

Section 5). The main objective of this study is to compare the sloshing damping time of water in containers with hydrophobic and non-hydrophobic walls. Our results will be compared with the work of [1]. Conclusion corresponds to

Section 6.

2. Experimental Set-Up

The experiments were performed at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory of the University of Guadalajara, Mexico.

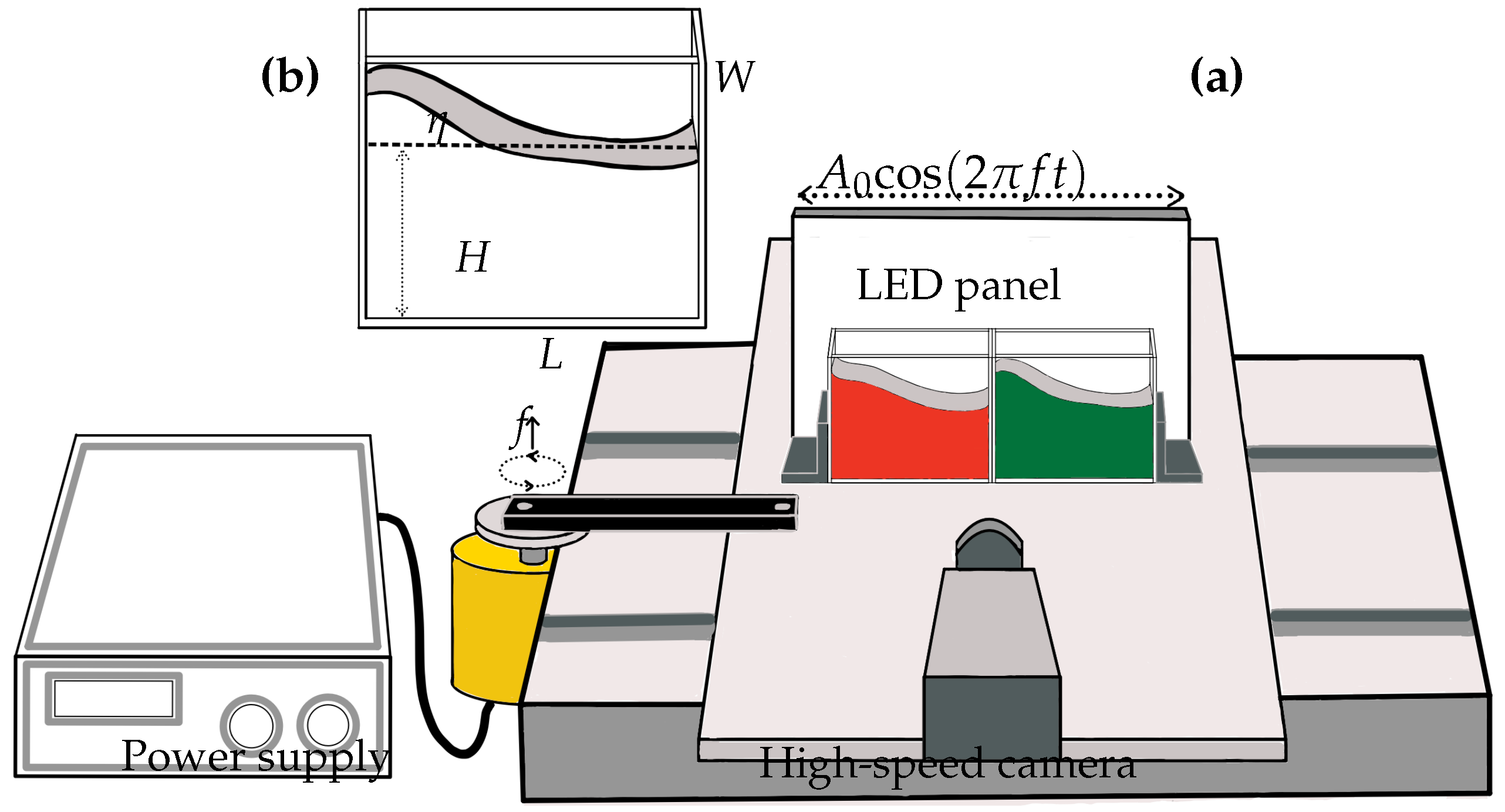

Figure 1(a) shows a scheme of our experimental setup; it is similar to that used by [12]. It consists of two transparent acrylic containers with the same dimensions. The experimenter controls their horizontal, periodic motion through a DC motor. Both containers are on a moving stage on rails and oscillate with a given amplitude

and a determined frequency

f. The harmonic lateral movement is thus described by

.

An LED panel has been located on the mobile platform behind the two containers to enhance container visualization. In front of them, a high-speed camera fixed on the moving stage records the water’s superficial waves at 240 fps. Each container was partially filled with colored water: green vegetable-dyed water for the hydrophobic-walled container and red water for the non-hydrophobic container. All the walls of the first container were coated with a thin layer of commercial Vaseline, including its bottom.

The present study is conducted on water. Its viscosity, density, and surface tension are considered constant, since the ambient temperature is maintained at

C. The panel in

Figure 1(b) points out the different parameters of our experiment:

W is the width of the container,

L its length,

H the depth of water before forcing, and

the maximum/minimum level of the free surface concerning its equilibrium.

The free surface period and decaying time are controlled by the depth of the liquid

H and the dimension of the container [13] and measurements were made for 8 different dimensions, each characterized by an aspect ratio

.

Table 1 shows the values for

,

W,

L and

H used in our experiments. Moreover, the natural frequencies of the superficial were calculated owing to the following equation [14]:

where

g is the acceleration of gravity. We checked that the consideration of the surface tension had no significant change (lower than

) on

values.

The methodology is as follows. The oscillation amplitude of the container is maintained constant and equal to

cm in all experiments. First, the DC motor is activated with a given low frequency. A video is recorded during several oscillation periods, and then the frequency is increased and the recording starts again. Amplitude measurements are reported in

Section 4.

After the forcing frequency

Hz was reached, the motor is suddenly stopped and the damping regime is recorded thanks to the same video camera. The results of this process are shown in

Section 5.

3. Video Processing: Wave Height Estimations Based on RGB Images and Data Extraction

The water height at a given point was extracted from the video as follows. The frames were recorded in RGB format with a time step of 0.0042 s and a spatial resolution of pixels. The physical dimension of each pixel was estimated from the distance between the free surface in equilibrium and the top of the same container; a pixel corresponds to m. After each frame was extracted from the video, it was binarized with optimal noise filtering parameters. To eliminate spurious values obtained from the free surface video data, we used Matlab’s csaps function, which employs a cubic smoothing spline. Then, the time history of one column of the binarized matrix is plotted in a diagram, where abscissa is the time and the y-axis is the space.

Figure 2 shows a frame in RGB format and the corresponding binarized version for the container with

. The column of pixels that was extracted to characterize the free-surface history is indicated by the vertical red lines on the right.

4. Forcing

As previously described, the excitation frequency was gradually increased over six values between 0 and

Hz.

Figure 3 shows the time history of six signals for

. The horizontal position of the container is indicated by the black line, where the maxima correspond to the position of the container on the right and are divided by

for better visualization. In the same graphics, green and red curves show the water surface history for the hydrophobic coated container and the uncoated one, respectively.

These graphics point out that the water level oscillates with the same frequency as the forcing one but with several harmonics. As the system is excited with a frequency different from the natural one, this is to be expected. Moreover, as the forcing frequency

f is higher, the oscillation amplitude

of the water level is greater; this behavior is predictable since the system approaches its resonance. It is also important to note that for all the tested forcing frequencies, the oscillation amplitude

is higher for the uncoated containers (red lines in

Figure 3) than for the hydrophobic containers.

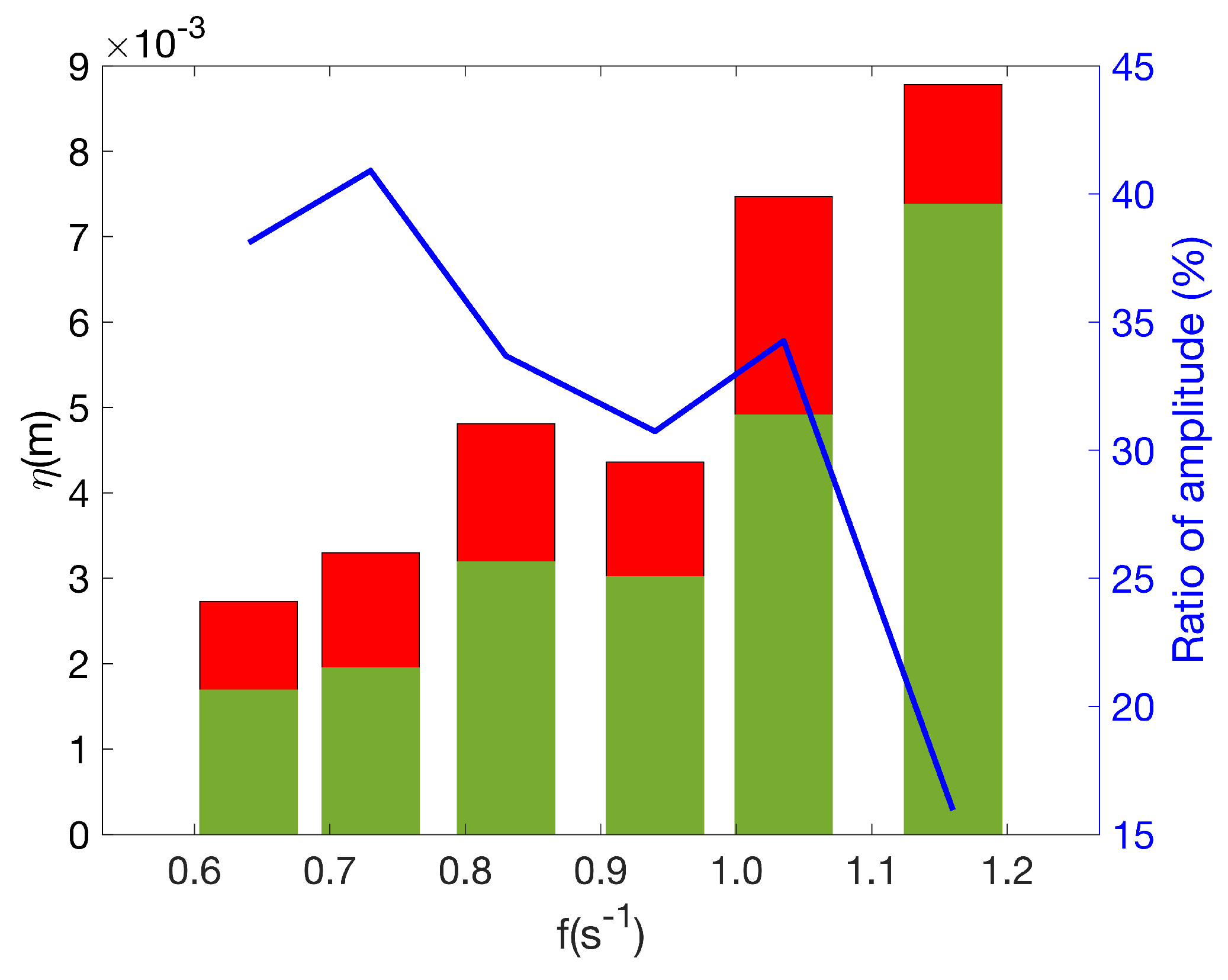

To quantify this difference, the left-hand vertical axis of

Figure 4 shows the evolution of the amplitude

as a function of the forcing frequency. The green bars are always lower than the red ones, as mentioned before. Now, the right-hand axis represents the difference in amplitude in % between the waves in the coated and uncoated containers. The solid blue line shows that the reduction in amplitude varies from

for higher frequency values to

for low frequency values, with an average value of approximately

.

It is interesting to note that our observations are different from the results reported by [1], who found an increase in the elevations of the free surface when the walls are hydrophobic. The resulting free-slip condition in the latter case should indeed promote faster motions of the water at the walls with higher waves. This is not the case in our experiments. This may be due to the development of a boundary layer despite a hydrophobic coating as explained by [15]. Moreover, recent experiments show that greater friction coefficients can be generated by hydrophobic coated walls as a comparison with hydrophilic coated walls [16].

5. Free Surface Damping

5.1. Damping Time

As mentioned above, the main objective of this work is to determine the influence of hydrophobic walls on the damping of the superficial waves after the container oscillation was suddenly stopped.

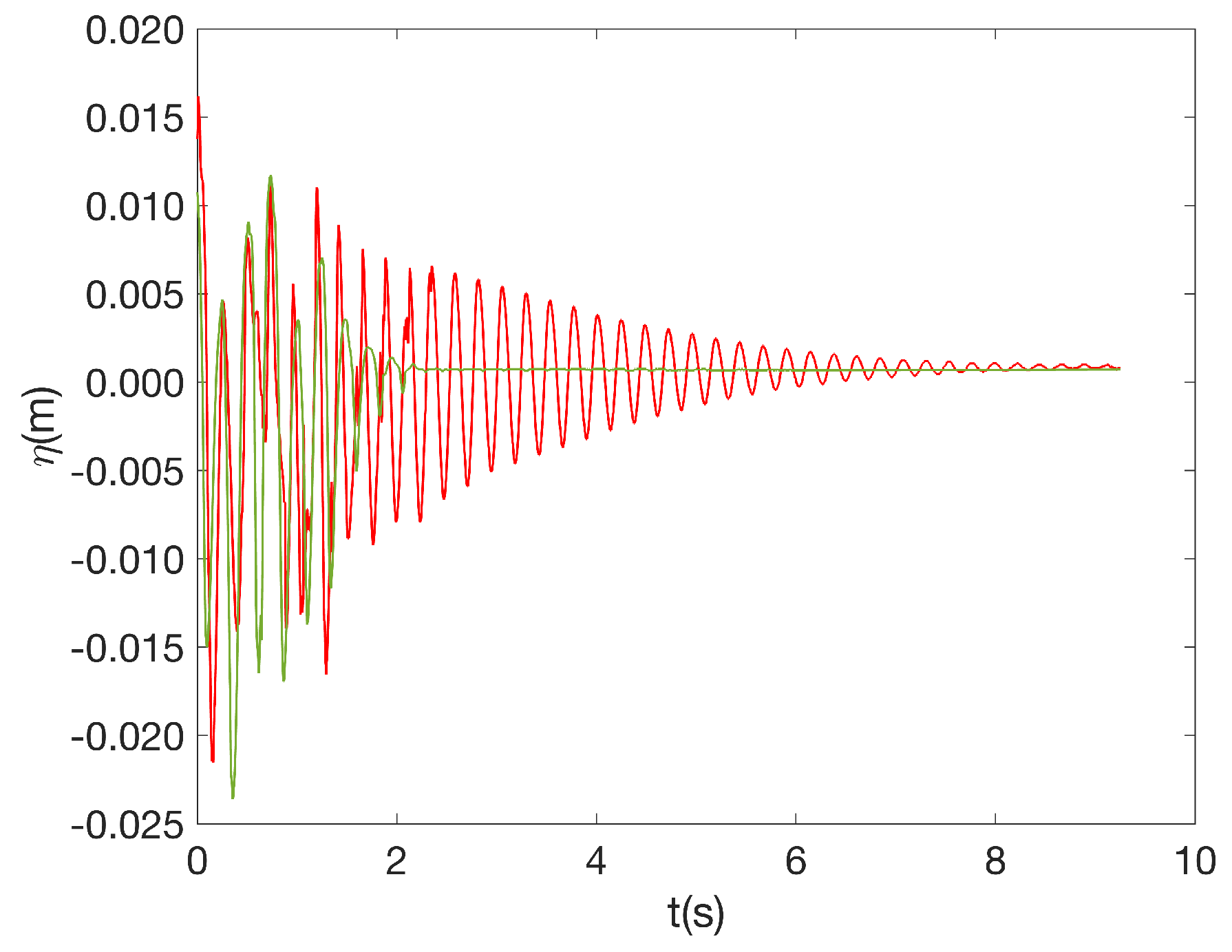

Figure 5 shows the oscillations of the water level for both the uncoated container (red line) and the hydrophobic container (green line). It is observed that the superficial waves in the hydrophobic-walled container are damped faster than the waves in the uncoated container. To quantify the damping time after the forcing was suddenly stopped, the following equation is used to fit the experimental points:

where

corresponds to the initial amplitude and

is the superficial waves’ natural frequency. To experimentally estimate the natural frequency of the superficial waves, the Fourier transform of the signal shown in

Figure 5 was calculated. The spectrum for

is shown in

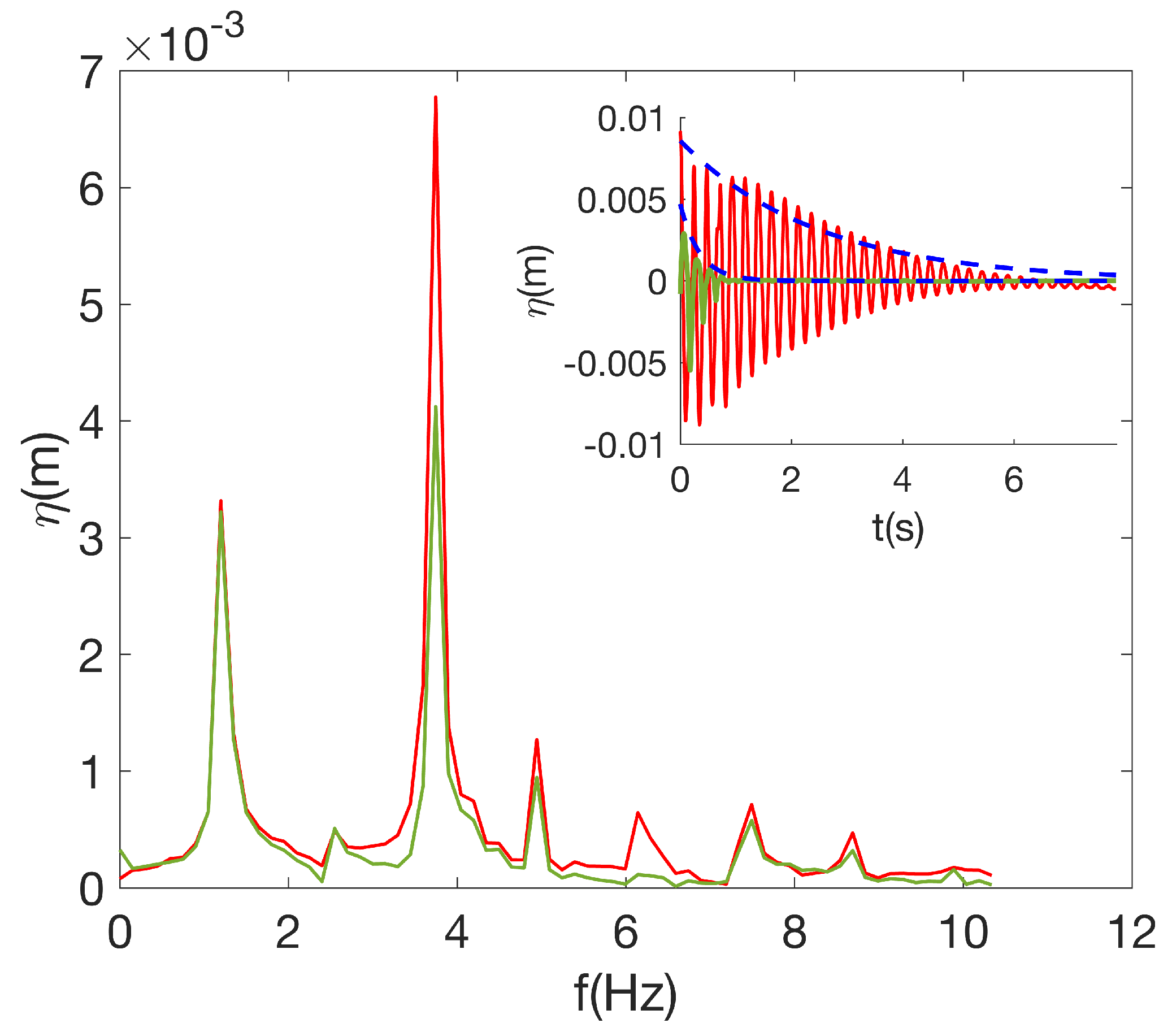

Figure 6.

The first peak represents the external forcing frequency (

) just before the excitation stopped. The second peak corresponds to the natural frequency of the system (

), which is consistent with Eq.

1 and

Table 1. The amplitude of the free surface waves in the uncoated container is observed to be greater than that of the hydrophobic coated container by approximately

.

An example of the evolution of the free surface

as a function of time after the forcing was turned off is shown in the inset of

Figure 6 for both containers. The dashed blue line is the external envelope of the damping process, i.e.,

where

and

are two fitting parameters. The best fitted values were

2.50

and 0.53

for the hydrophobic and uncoated walls, respectively. The higher value

for the hydrophobic container means greater damping. In this case (

), the hydrophobic coated walls dissipate about 5 times better than the superficial waves that concern the uncoated container.

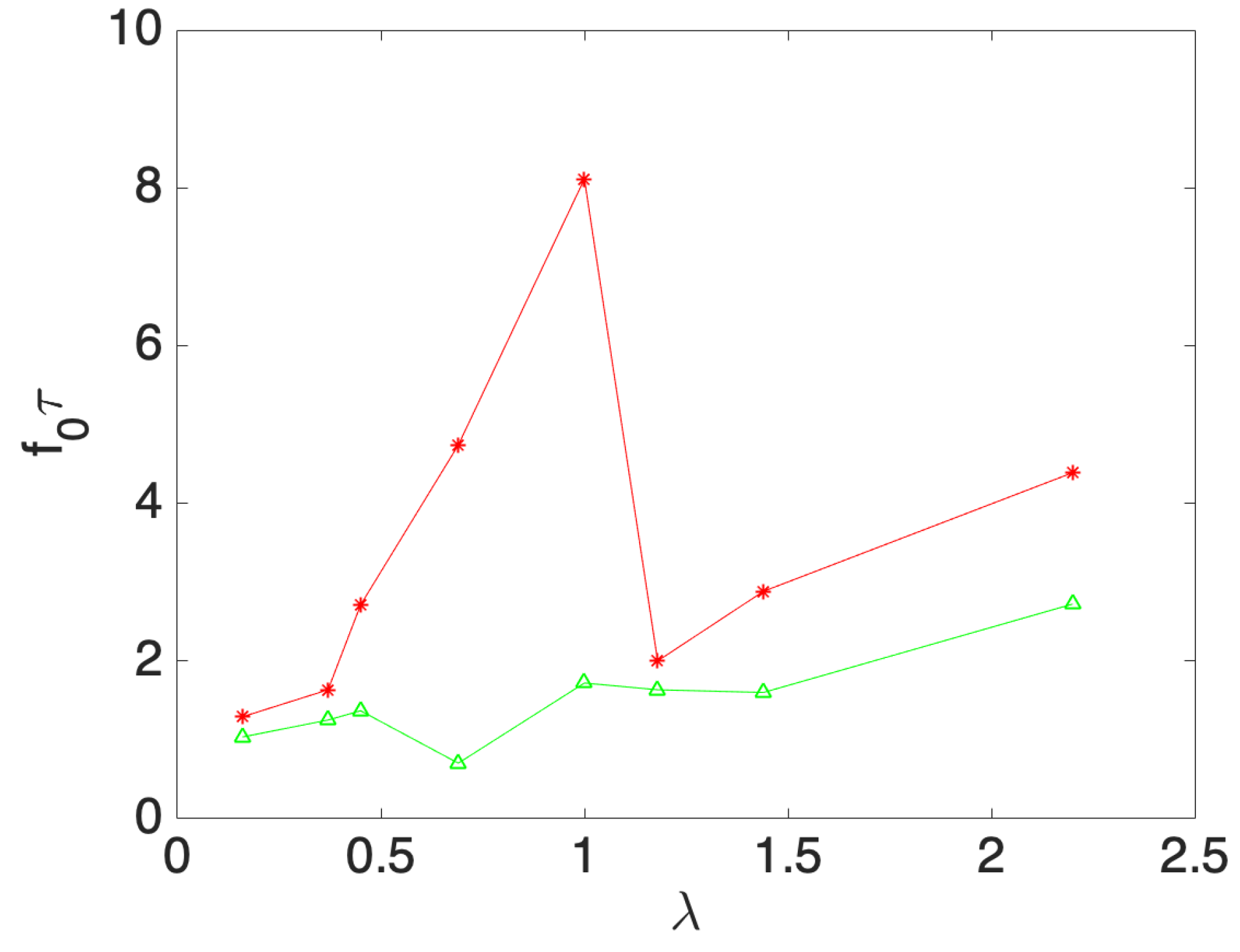

Applying the same process to all available containers (see

Table 1), it is possible to estimate

for the coated and uncoated configurations. Our results are reported in

Figure 7 in the form of non-dimensional parameters: the

x axis is

, while the

y axis corresponds to

. The latter quantity corresponds to the number of periods necessary for the system to be damped. The red curve is always above the green curve, which means that the uncoated containers last longer than the hydrophobic-walled containers to attenuate the superficial waves.

We should mention that a test was carried out on a pair of containers with larger dimensions,

cm and

cm, which corresponds to an aspect ratio

. It is interesting to note that the damping ratio was almost equal (

greater) to the one reported for

in

Table 2. This result leads us to believe that

is indeed the correct nondimensional parameter to consider.

It is also important to note that the less damped uncoated container corresponds to

, since more than 8 periods are necessary to attenuate the waves. But this is for the same container that the effect of the hydrophobic walls is more efficient since

Table 2 shows that the highest damping effectiveness is reached for

and

.

The higher damping in the case of hydrophobic walls is not intuitive since the consequent non-slipping condition should lead to a lower dissipation in the boundary limit near the wall container. However, this result is in agreement with the results of [1] who measured the pressure load on the lateral walls for both the uncoated and hydrophobic containers. They found that hydrophobicity causes a reduction in impact pressures and therefore decreases sloshing effects. The same phenomenon occurs here. In the present work, quantitative measurements of the damping coefficients allow us to quantify the reduction in sloshing due to the hydrophobic walls. This study is therefore complemented by the results of [1]’s results.

An important result is that the damping coefficient depends on the width

W through the aspect ratio

even though the waves are bidimensional, i.e., no dependence on the width direction was observed, as will be detailed in

Section 5.2. However, it is well known that

may depend on the width of the container

W, as explained by [12,17] when a boundary layer develops on the lateral wall and causes dissipation due to the viscosity of the fluid. In the present case, the pressure load is also exerted on the whole lateral wall.

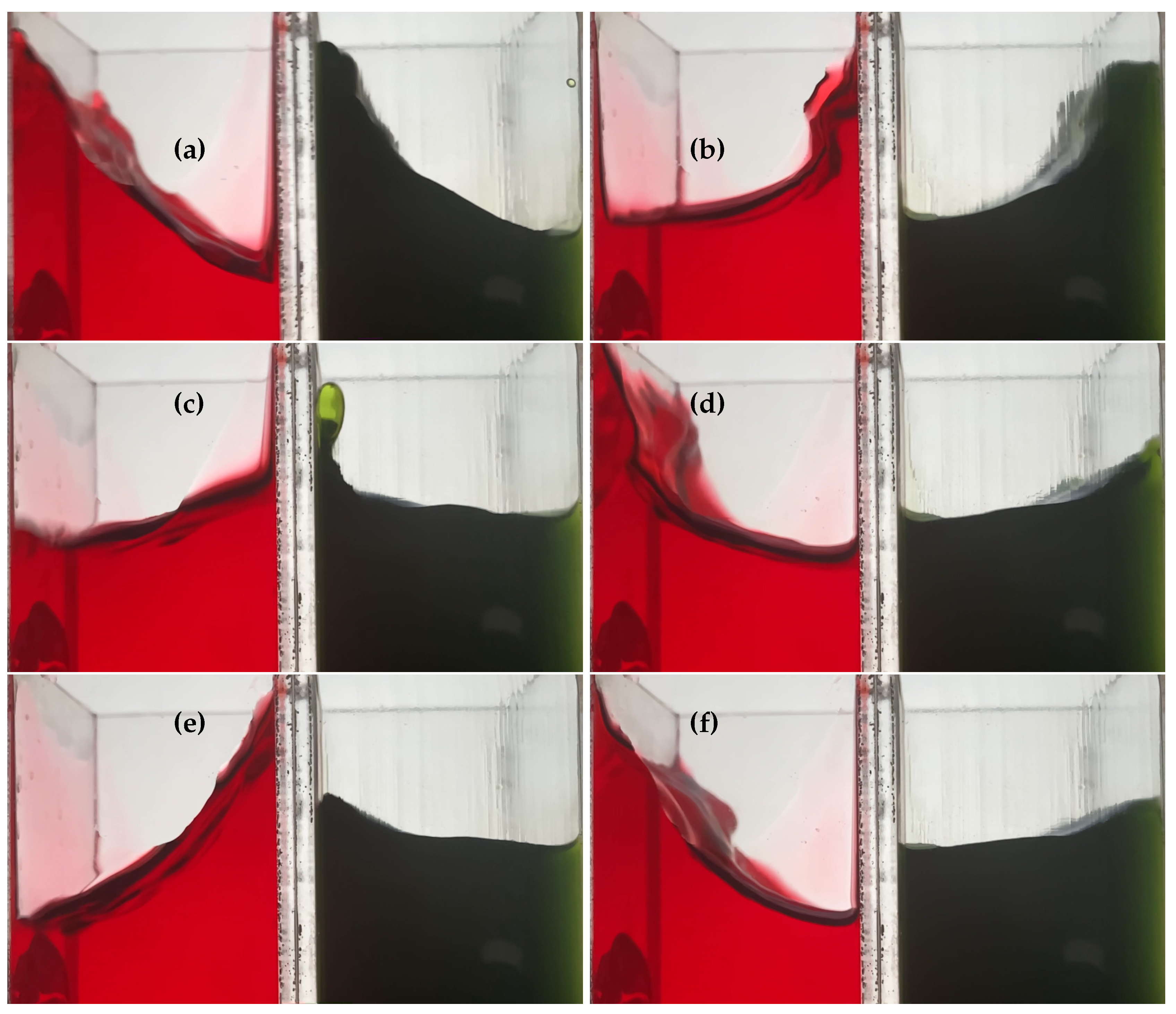

5.2. Waves Visualization

In this section, we describe a series of video snapshots of hydrophobic and hydrophilic containers to compare them and discuss the influence of the oil-coated walls.

Figure 8 shows 6 snapshots extracted from the video for

, 1 second after the forcing was suddenly stopped (see the inset of

Figure 6). A time interval equal to 0.166 s

separates each pair of images. Following the same methodology, the red color is for hydrophilic walls while the green color is for hydrophobic ones (hereafter red and green waves). In panel

(a), it can be observed that the red wave is slightly larger in amplitude and steeper than the green wave. However, the horizontal width at the top of the green wave’s crest is greater. This can be explained by a greater adhesion of the red fluid to the hydrophilic condition of the container. Note that, at this instant, both waves are in phase. In panel

(b), the crests of the two waves reach again roughly the same amplitude on the opposite wall. The two waves have roughly the same shape, although the green wave is again wider than the red one. The waves are still in phase. In panel

(c), the waves are completely phase-shifted and a shape similar to a breaking wave can be detected in the green container. Because of the hydrophobic wall in this latter container, the fluid cannot adhere to the wall, so its shape is curved, contrary to that of the red liquid. In panel

(d), the waves are again phase-shifted and a greater difference in amplitude and shape is observed. In the red container, the waveform is different from that in panel

(a); now, most of the liquid is stuck to the wall. However, in the green container, the wave is significantly attenuated. In panel

(e), the wave in the red container oscillates with the same amplitude as in panel

(a), but on the opposite wall, whereas the green wave’s amplitude keeps decreasing. This suggests that the effect of impact loads is significantly reduced on hydrophobic walls. Finally, in panel

(f), the behavior of the two waves is similar to that of panel

(e), but with a shifted phase.

This behavior was similar in all of our experiments. That is, a certain amount of red fluid is allowed to adhere to the walls; this is not the case for the green liquid. The shape of the free surface in the green container is also smoother. These features show the importance of the boundary layer and the hydrophobic effects which appear as a source of energy dissipation.

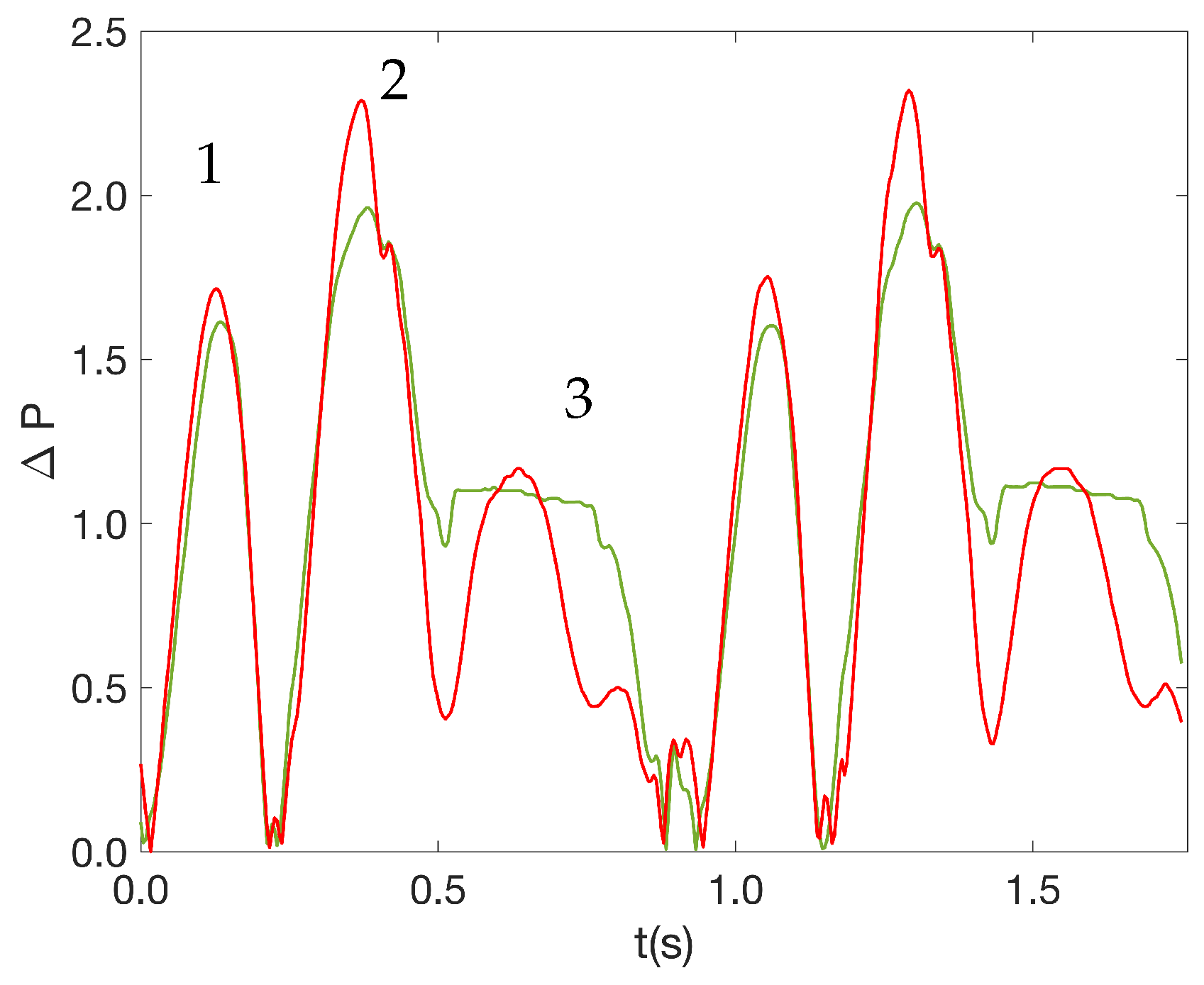

5.3. Pressure Load

Although the fluid viscosity does not change in our experiment, the pressure load on the walls of the containers does [1]. We could not directly measure the pressure on the vertical walls of the container, so we estimated the pressure through the scaled absolute hydrostatic pressure of the wave

[14]. This quantity was deduced from the wave elevation through the following expression:

Figure 9 shows three cycles of the pressure history for a portion of

Figure 3(b). In these graphics, the peaks correspond to the wave impact resulting from the external forcing on either lateral wall. For the first two peaks, the contact time is the same in the case of hydrophobic containers as in the hydrophilic ones. As for peak 3, it is similar in amplitude but not in time. Its shape shows that it corresponds to a longer contact time for the green wave, resulting in a greater energy loss despite a similar pressure amplitude.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we have experimentally studied how a hydrophobic coating on the walls of a container can drastically dampen the sloshing waves as a comparison with an uncoated one. First, we observed that when the external forcing is periodic, the amplitude of the free surface in the container without hydrophobic coated walls is always up to higher. Moreover, to quantify the free surface’s damping time after the forcing was suddenly stopped, we used an exponential function to fit the decrement of the oscillation amplitude. The corresponding damping coefficient of the free surface in the hydrophobic container is always lower than in the uncoated container. This behavior is congruent with the observations of [1] who measured lower pressure loads when a hydrophobic oil coats the walls. Moreover, the values of are strongly influenced by the container’s aspect ratio . For values of , the damping coefficient reduced up to the corresponding value of the non-hydrophobic walls. We think these experimental results are important to reduce the sloshing in containers. Finally, the energy loss due to the interaction of the fluid with the hydrophobic walls gives us a guideline to experiment with numerical models on unintuitive aspects to support the results obtained in the aforementioned research studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.C.G. and A.C.; methodology, L.E.C.P.; software, R.C.C.G and L.E.C.P.; validation, C.O.M., R.C.C.G. and A.C.; formal analysis, C.O.M.; investigation, R.C.C.G.; resources, L.E.C.P.; data curation, R.C.C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.C.G.; writing—review and editing, A.C and C.O.M.; visualization, R.C.C.G.; supervision, C.O.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

First, the first author is grateful toward the Geo- physical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and the Fluid Mechanics Labora- tory of CUCEI, Guadalajara University for allowing us to perform the experiments. The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments of two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and for providing very constructive comments that improved the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Korkmaz, F.C. and Güzel, B. Insights from sloshing experiments in a rectangular hydrophobic tank. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 2023, 146, 110920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.A. Liquid Sloshing Dynamics: Theory and Applications. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2005.

- Zou, C.F.; Wang, D.Y.; Cai, Z.H.; Li, Z. The effect of liquid viscosity on sloshing characteristics. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2015, 7, 670–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C; Su, P; Ning, D. Hydrodynamic study of an anti-sloshing technique using floating foams. Ocean Eng. 2019, 175, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M. A.; Zheng, J.; Lin, P.; Yuan, X. Experimental study on vertical baffles of different configurations in suppressing sloshing pressure. Ocean Eng. 2017, 136, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Xiong, C.; Ma, G. Numerical study on suppressing violent transient sloshing with single and double vertical baffles. Ocean Eng. 2021, 223, 108557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.J. Experimental study on sloshing in a tank with an inner horizontal perforated plate. Ocean Eng. 2014, 82, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Cho, IH. Anti-slosh effect of a horizontal porous baffle in a swaying/rolling rectangular tank: Analytical and experimental approaches. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2021, 13, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lin, P. Viscous effects on liquid sloshing under external excitations. Ocean Eng. 2018, 171, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, F.C. Damping of sloshing impact on bottom-layer fluid by adding a viscous top-layer fluid. Ocean Eng. 2022, 254, 111357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, J.; Sauret, A.; Boulogne, F.; Dressaire, E.; Stone, H.A. Damping of liquid sloshing by foams: From everyday observations to liquid transport. J. Vis. 2015, 18, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauret, A.; Boulogne, F.; Cappello, J.; Dressaire, E.; Stone, H.A. Damping of liquid sloshing by foams. Phys. Fluids 2015, 27, 022103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, L.; Cruchaga, M.; Storti, M.; D’Elía J, Núñez-Aedo, J. ; Reinoso, R. Numerical modelling of 3D sloshing experiments in rectangular tanks. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2018, 59, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Ch.F.; Wang, De.Yu.; Cai, Z.H. Effects of boundary layer and liquid viscosity and compressible air on sloshing characteristics. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2015, 7, 670–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretheway, D.C.; Meinhart, C.D. Apparent fluid slip at hydrophobic microchannel walls. Physics of fluids 2002, 3, L9–L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, P.M.; Claesson, P.M.; Swerin, A.; Briscoe, W.H.; Schoelkopf, J.; Gane, P.A.; Thormann, E. Frictional forces between hydrophilic and hydrophobic particle coated nanostructured surfaces. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2013, 15(41), 17893–17902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfort, A.; Caps, H. Faraday instability at foam-water interface. Phys. Rev. E 2012, 86, 066313–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).