Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

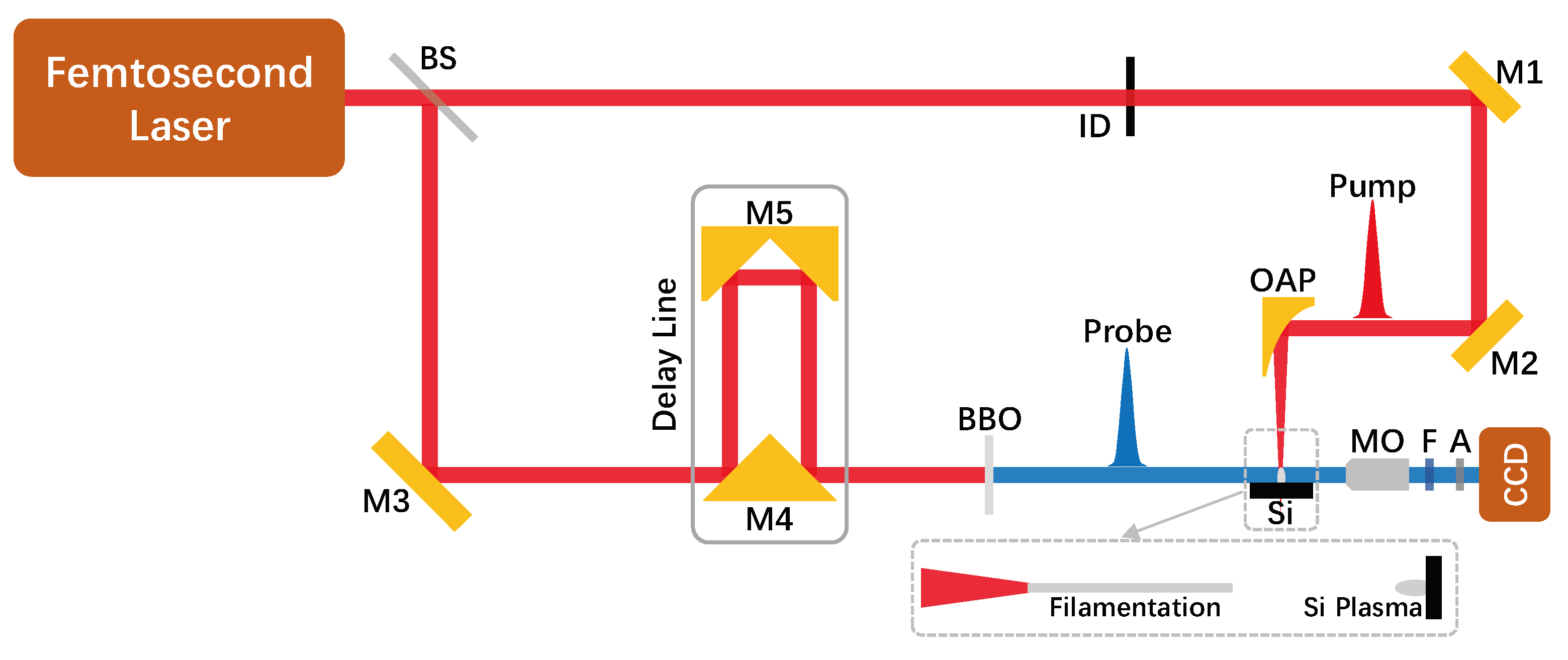

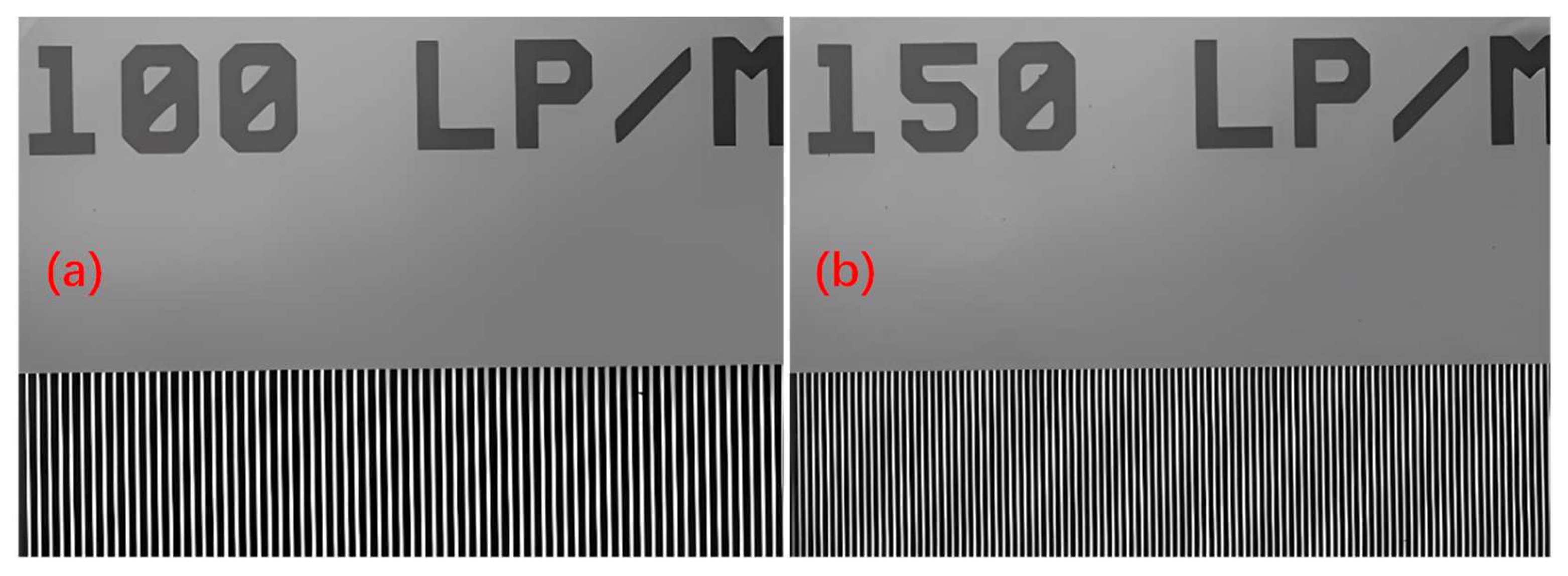

2. Experiment

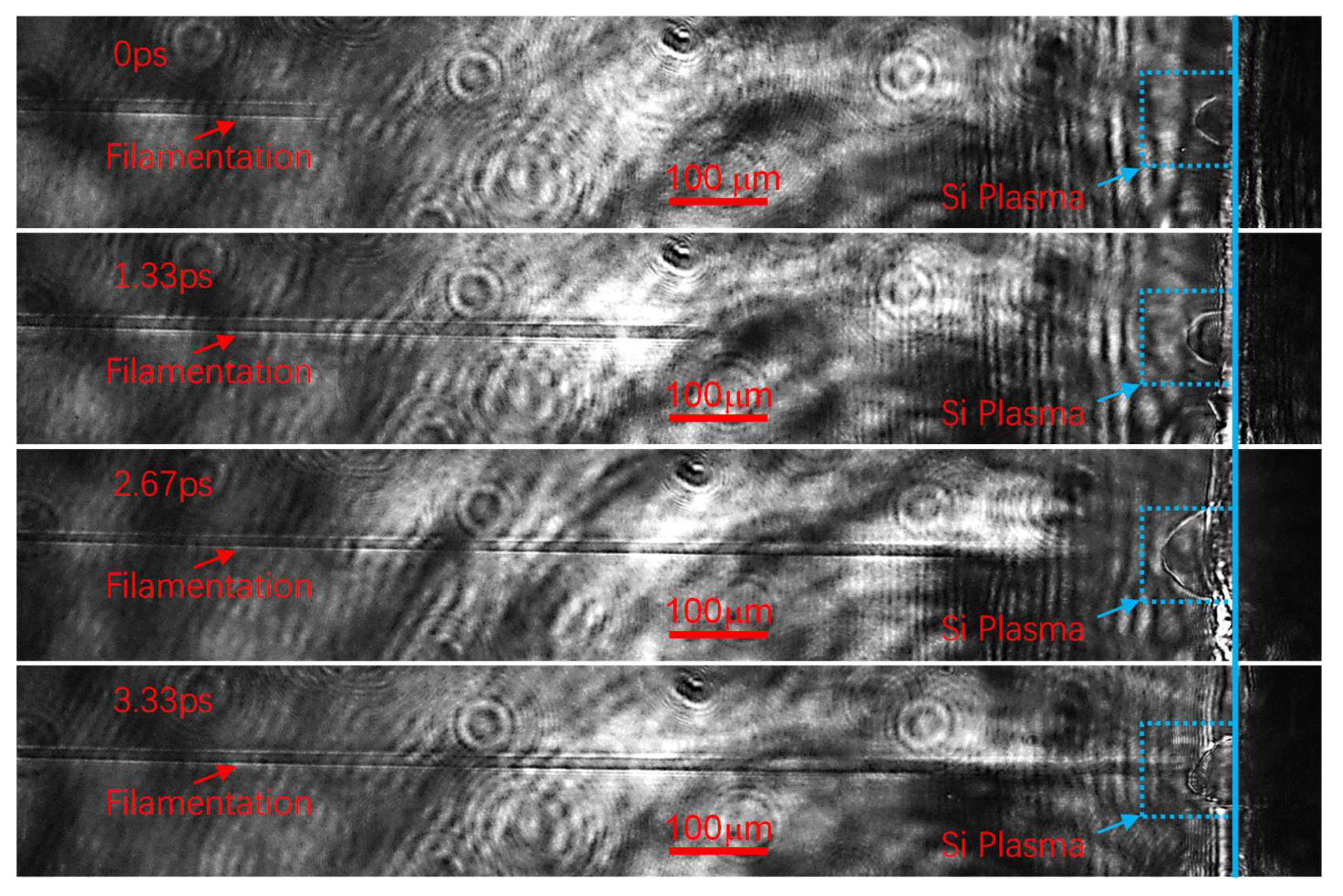

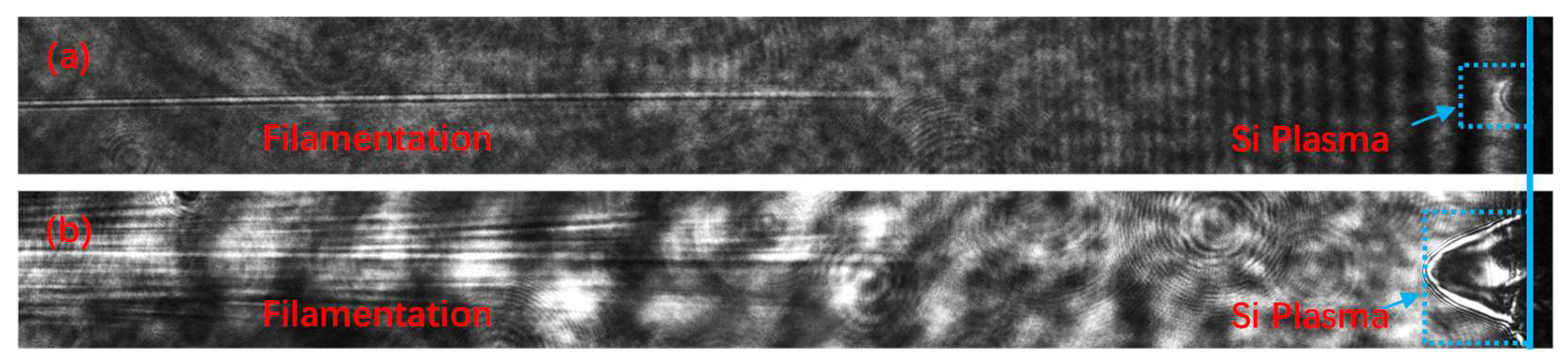

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lamač, M.; Chaulagain, U.; Nejdl, J.; Bulanov, S.V., Generation of intense magnetic wakes by relativistic laser pulses in plasma. Sci Rep-Uk 2023, 13, (1), 1701. [CrossRef]

- Houard, A.; Walch, P.; Produit, T.; Moreno, V.; Mahieu, B.; Sunjerga, A.; Herkommer, C.; Mostajabi, A.; Andral, U.; André, Y.; Lozano, M.; Bizet, L.; Schroeder, M.C.; Schimmel, G.; Moret, M.; Stanley, M.; Rison, W.A.; Maurice, O.; Esmiller, B.; Michel, K.; Haas, W.; Metzger, T.; Rubinstein, M.; Rachidi, F.; Cooray, V.; Mysyrowicz, A.; Kasparian, J.; Wolf, J., Laser-guided lightning. Nat Photonics 2023, 17, (3), 231-235. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Y.N.; Wang, P.; Bauer, F.J.; Zhang, Y.; Hanstorp, D.; Will, S.; Wang, L.V., Single-pulse real-time billion-frames-per-second planar imaging of ultrafast nanoparticle-laser dynamics and temperature in flames. Light: Science & Applications 2023, 12, (1), 47. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Yin, F.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, K.; Leng, Y., Time-resolved measurements of electron density and plasma diameter of 1 kHz femtosecond laser filament in air. Chin Opt Lett 2022, 20, (9), 93201. [CrossRef]

- Man, M.K.L.; Margiolakis, A.; Deckoff-Jones, S.; Harada, T.; Wong, E.L.; Krishna, M.B.M.; Madéo, J.; Winchester, A.; Lei, S.; Vajtai, R.; Ajayan, P.M.; Dani, K.M., Imaging the motion of electrons across semiconductor heterojunctions. Nat Nanotechnol 2017, 12, (1), 36-40. [CrossRef]

- Wolter, B.; Pullen, M.G.; Le, A.T.; Baudisch, M.; Doblhoff-Dier, K.; Senftleben, A.; Hemmer, M.; Schröter, C.D.; Ullrich, J.; Pfeifer, T.; Moshammer, R.; Gräfe, S.; Vendrell, O.; Lin, C.D.; Biegert, J., Ultrafast electron diffraction imaging of bond breaking in di-ionized acetylene. Science 2016, 354, (6310), 308-312. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., High Energy electron and proton acceleration by circularly polarized laser pulse from near critical density hydrogen gas target. Sci Rep-Uk 2018, 8, (1), 2191. [CrossRef]

- Yamanouchi, K.; Charalambidis, D., Progress in Ultrafast Intense Laser Science XV. Springer Nature: Cham, 2020; Vol. 136.

- Li, Z.; Lin, J.; Wang, C.; Li, K.; Jia, X.; Wang, C.; Duan, J.A., Damage performance of alumina ceramic by femtosecond laser induced air filamentation. Optics & Laser Technology 2025, 181, 111781. [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, S.M.; Zavedeev, E.V.; Arutyunyan, N.R.; Jaeggi, B.; Neuenschwander, B., Femtosecond laser-induced periodic surface structures on diamond-like nanocomposite films. Diam Relat Mater 2022, 130, 109517. [CrossRef]

- Tsibidis, G.D.; Mansour, D.; Stratakis, E., Damage threshold evaluation of thin metallic films exposed to femtosecond laser pulses: The role of material thickness. Optics & Laser Technology 2022, 156, 108484. [CrossRef]

- ZOU, G.; YE, J.; BAO, X., Observation on the clinical effect of femtosecond laser small incision lens extraction in the correction of myopia and astigmatism. Minerva Surg 2022, 77, (6), 610-612. [CrossRef]

- Kryszak, B.; Szustakiewicz, K.; Dzienny, P.; Junka, A.; Paleczny, J.; Szymczyk-Ziółkowska, P.; Hoppe, V.; Antończak, A., Functionalization of the PLLA surface with a femtosecond laser: Tailored substrate properties for cellular response. Polym Test 2022, 116, 107815. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xin, C.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Pan, D.; Ren, Z.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Chu, J.; Wu, D., Femtosecond Laser Fabrication of Three-Dimensional Bubble-Propelled Microrotors for Multicomponent Mechanical Transmission. Nano Lett 2024, 24, (10), 3176-3185. [CrossRef]

- Chin, S.L., Femtosecond Laser Filamentation. Springer: New York, 2010.

- Chin, S.L.; Xu, H., Tunnel ionization, population trapping, filamentation and applications. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics 2016, 49, (22), 222003. [CrossRef]

- Peña, J.; Reyes, D.; Richardson, M., Filamentation in low pressure conditions. Sci Rep-Uk 2022, 12, (1), 21365. [CrossRef]

- Harilal, S.S.; Yeak, J.; Phillips, M.C., Plasma temperature clamping in filamentation laser induced breakdown spectroscopy. Opt Express 2015, 23, (21), 27113. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, F.; Wang, T.; Leng, Y.; Li, R.; Xu, Z.; Chin, S.L., Stable, intense supercontinuum light generation at 1 kHz by electric field assisted femtosecond laser filamentation in air. Light: Science & Applications 2024, 13, (1), 42. [CrossRef]

- Geints, Y.E.; Bulygin, A.D.; Kompanets, V.O.; Chekalin, S.V., Supercontinuum saturation of a femtosecond laser filament in pressurized gases. Opt Lett 2024, 49, (21), 6033. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hao, Z.; Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, L., Polarization of the third harmonic emission from the filamentation of femtosecond cylindrical vector beams. Opt Express 2024, 32, (1), 387. [CrossRef]

- Babushkin, P.A.; Bulygin, A.D.; Geints, Y.E.; Kabanov, A.M.; Oshlakov, V.K.; Petrov, A.V.; Khoroshaeva, E.E., Turbulence-enhanced THz generation by multiple chaotically-distributed femtosecond filaments in air. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 179, 111322. [CrossRef]

- Pushkarev, D.V.; Zhidovtsev, N.A.; Uryupina, D.S.; Mitina, E.V.; Volkov, R.V.; Savel Ev, A.B., Three-domain stabilization of femtosecond filament red-shifted light bullet in air by means of beam amplitude modulation. Optics & Laser Technology 2025, 180, 111438. [CrossRef]

- Brée, C.; Babushkin, I.; Morgner, U.; Demircan, A., Regularizing Aperiodic Cycles of Resonant Radiation in Filament Light Bullets. Phys Rev Lett 2017, 118, (16), 163901. [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, P.; Whalen, P.; Kolesik, M.; Moloney, J.V., Super high power mid-infrared femtosecond light bullet. Nat Photonics 2015, 9, (8), 543-548. [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Jiang, H.; Houard, A.; Tikhonchuk, V.; Oliva, E.; Mysyrowicz, A.; Gong, Q.; Wu, C.; Liu, Y., Fluorescence and lasing of neutral nitrogen molecules inside femtosecond laser filaments in air: mechanism and applications. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics : PCCP 2024, 26, (36), 23528-23543. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Li, N.; Yi, Y., Spatial distribution of self-seeded air lasers induced by the femtosecond laser filament plasma. J Plasma Phys 2024, 90, (4), 905900404. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, M.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Zheng, L.; Chin, S.L.; Zeng, H., Filament-induced ultrafast birefringence in gases. Journal of Physics. B, Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics 2015, 48, (9), 94018-10. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.P., Short-pulse lasers for weather control. Rep Prog Phys 2018, 81, (2), 026001. [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Arantchouk, L.; Lozano, M.; Mysyrowicz, A.; Couairon, A.; Houard, A., Laguerre–Gaussian laser filamentation for the control of electric discharges in air. Opt Lett 2024, 49, (13), 3540.

- Latty, K.S.; Hartig, K.C., Atmospheric clearing of solid-particle debris using femtosecond filaments. Phys Rev Appl 2024, 22, (1), 014075. [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Mahieu, B.; Mysyrowicz, A.; Houard, A., Femtosecond filamentation of optical vortices for the generation of optical air waveguides. Opt Lett 2022, 47, (19), 5228-5231. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yan, B.; Yuan, Y.; Cai, Y.; Hao, Z.; Li, J., Real-Time Demonstration of Multi-Gigabit/s Free- Space Optical Communications Employing Femtosecond Laser Filaments in Complex Environment. J Lightwave Technol 2024, 42, (13), 4402-4409. [CrossRef]

- Froula, D.H.; Turnbull, D.; Davies, A.S.; Kessler, T.J.; Haberberger, D.; Palastro, J.P.; Bahk, S.; Begishev, I.A.; Boni, R.; Bucht, S.; Katz, J.; Shaw, J.L., Spatiotemporal control of laser intensity. Nat Photonics 2018, 12, 262–265. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, W.; Petrarca, M.; Polynkin, P., Universal threshold for femtosecond laser ablation with oblique illumination. Appl Phys Lett 2016, 109, (16), 161604. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).