Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

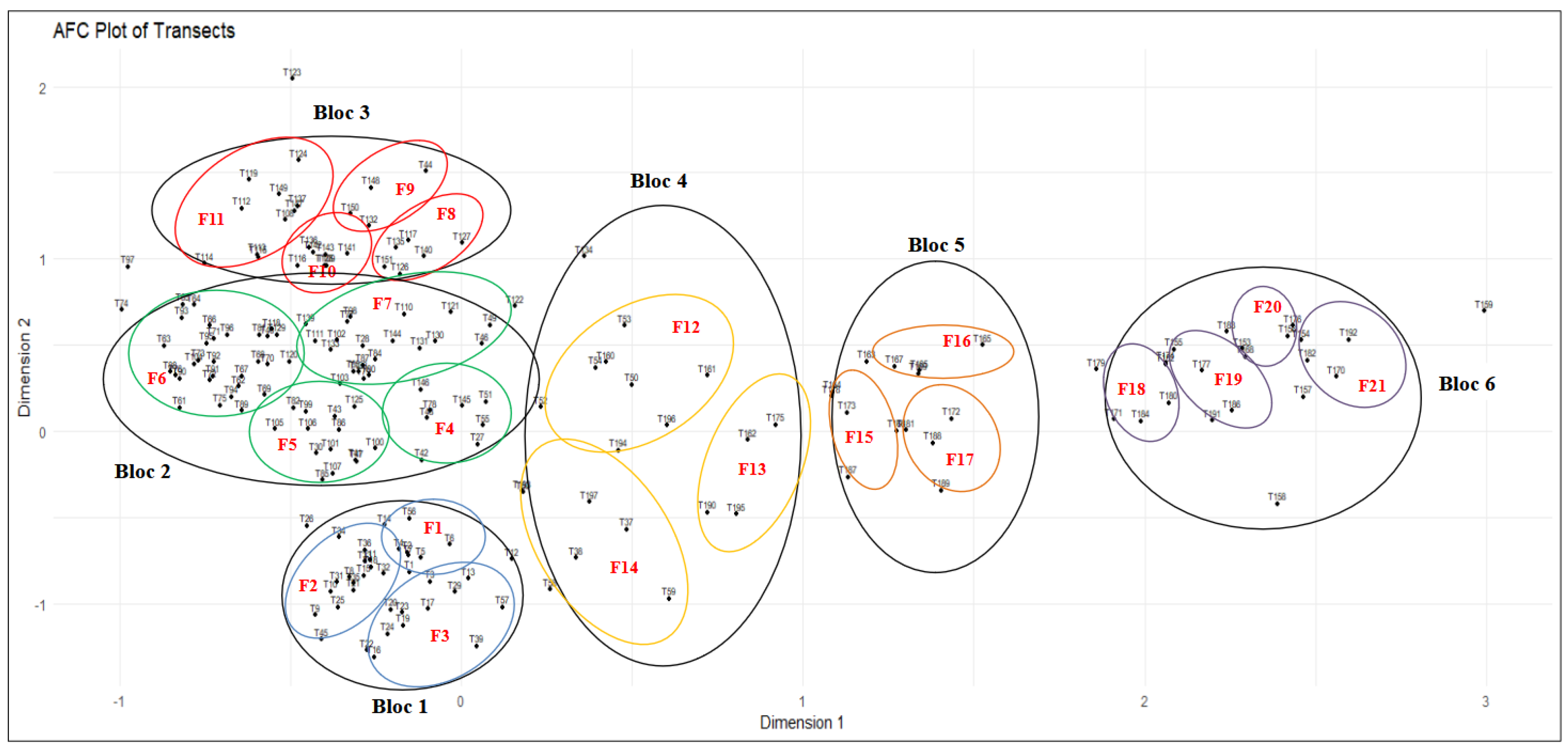

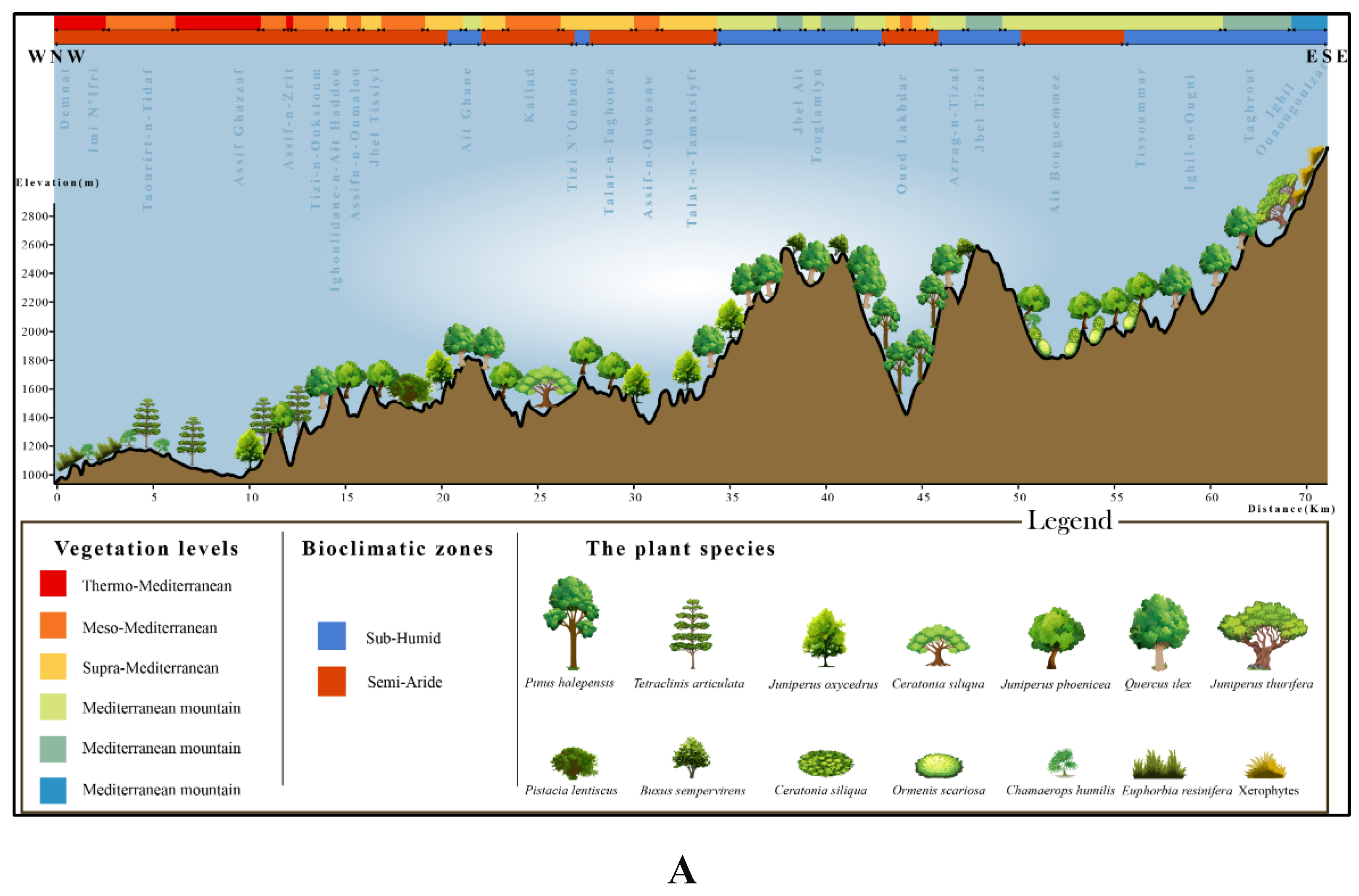

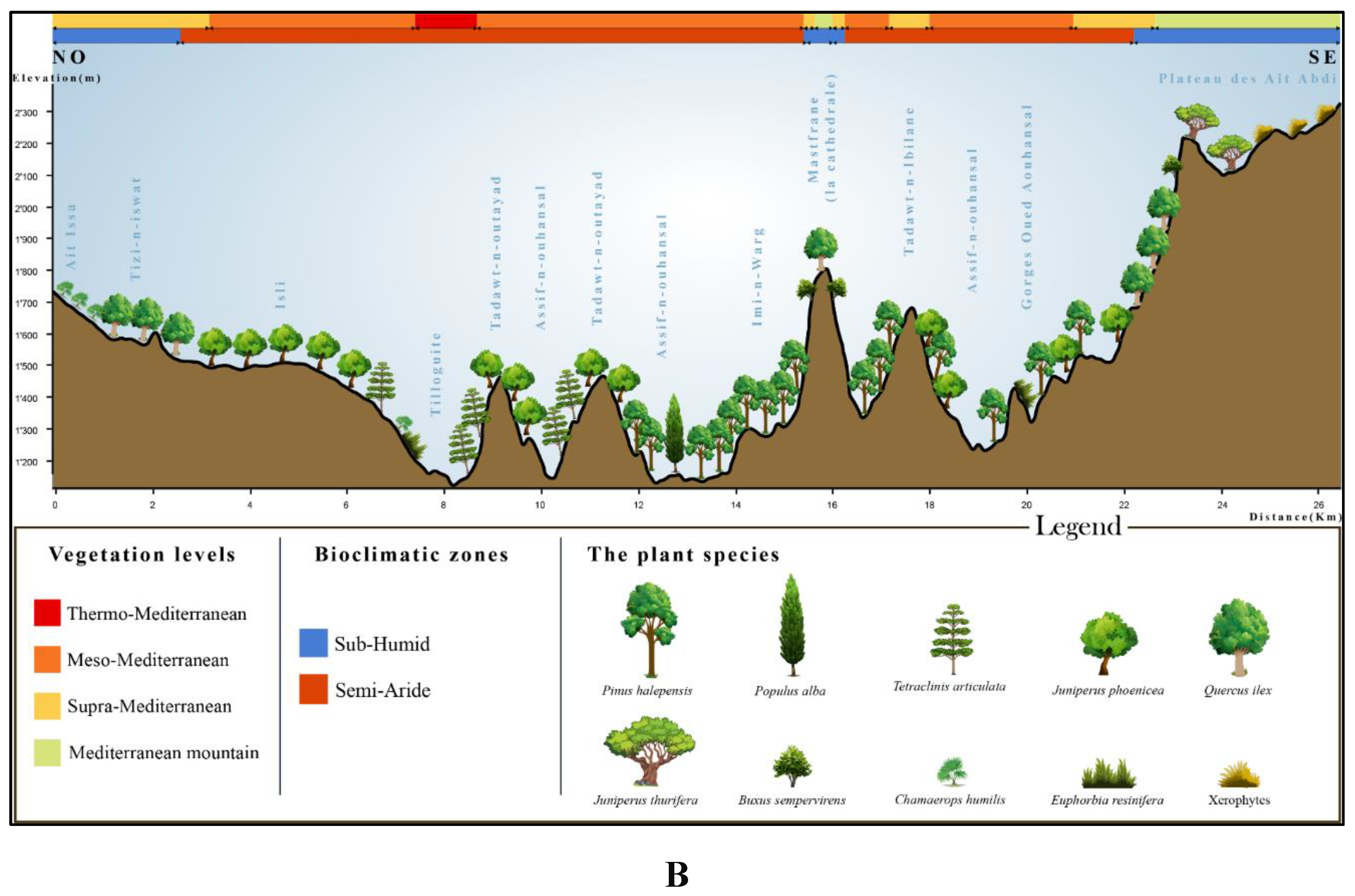

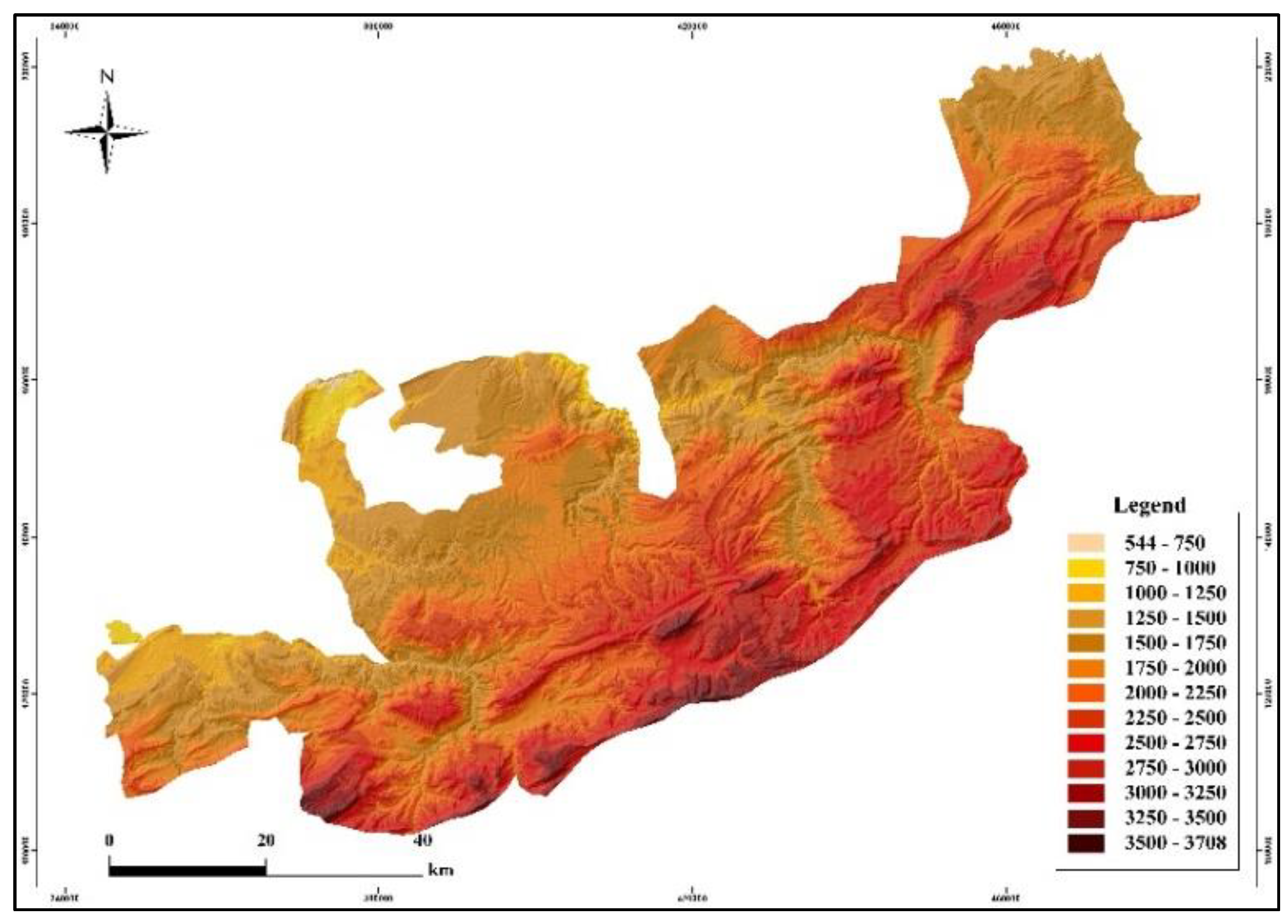

The vegetation cover in Morocco is impacted profoundly by human activities and climate change. However, the majority of ecosystems are not yet assessed. Using the sampling of vegetation, climate data, substrate (geological) map and altitudes (Digital Elevation Model) the phytoecology of species is constructed. The study revealed that the geopark contain 565 species. Floristic analysis, using correspondence analysis test, demonstrates that species are grouped into six distinct blocks. Block 1 comprises a set of Quercus ilex forests. Block 2 encompasses Juniperus phoenicea lands and transition zones between Q. ilex and J. phoenicea. Block 3 represents Pinus halepensis forests and pine occurrences within Q. ilex and J. phoenicea stands. Block 4 indicates the emergence of xerophytic species alongside the aforementioned species, suggesting the upper limits of Blocks 1, 2, and 3. Block 5 corresponds to formations dominated by Juniperus thurifera in association with xerophytes. Block 6 groups together a set of xerophytic species characteristic of high mountain environments. The formations species sampled are: Q. ilex that colonizes the subhumid zones, J. phoenicea, Tetraclinis articulata and P. halepensis occupy the hot part of the semi-arid while the J. thurifera and xerophytes inhabits its cold part. The thermo-Mediterranean vegetation level occupies low altitudes and is dominated by Tetraclinis articulata, J. phoenicea, and Olea europaea. The meso-Mediterranean level extends to intermediate altitudes and is dominated by Q. ilex and J. phoenicea. The supra-Mediterranean level, also found at intermediate altitudes, is dominated by Q. ilex, Arbutus unedo, and Cistus creticus. The mountain Mediterranean level, located in high mountains, is dominated by J. thurifera associated with xerophytes. Finally, the oro-Mediterranean level, found at extreme altitudes, is dominated by xerophytes. Generally, Q. ilex formations prefer limestone substrates. P. halepensis occupies limestone, clays, and conglomerates. J. phoenicea is more commonly associated with clays and sandstones. Xerophytic species and J. thurifera tend to inhabit limestone substrates. Some species within this region are endemic, rare, and threatened. Consequently, the implementation of effective conservation and protection policies is crucial.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

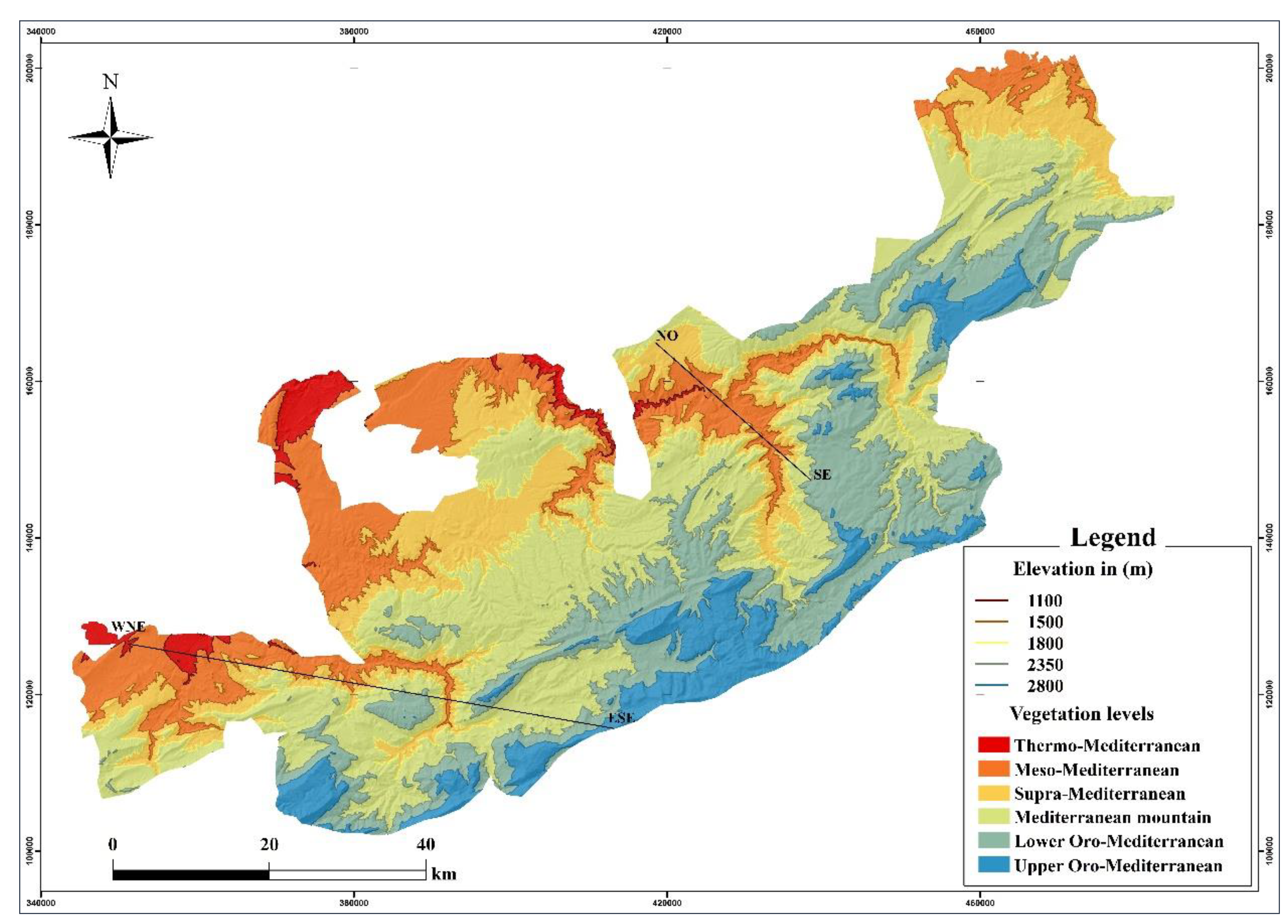

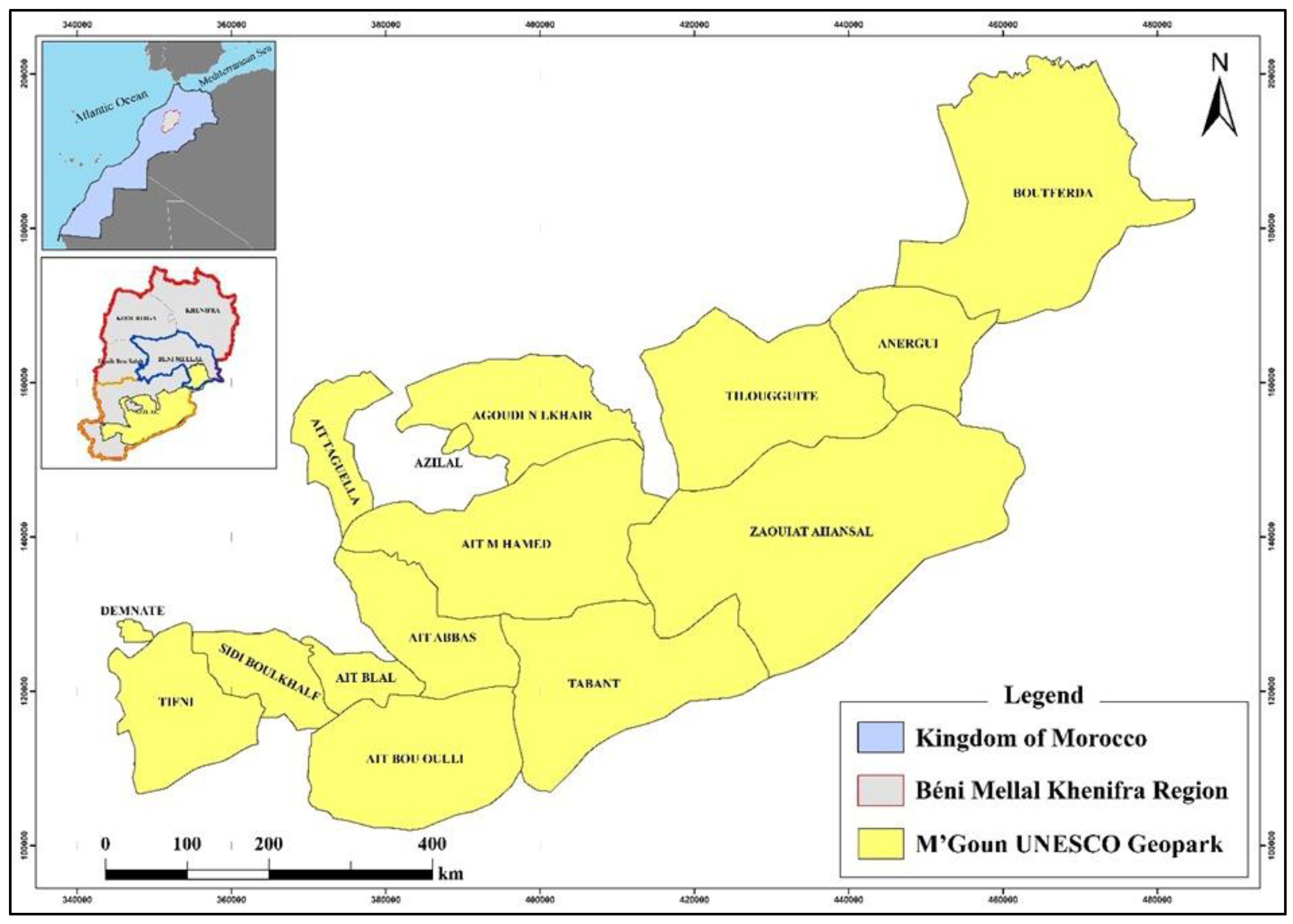

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Sampling, Species Identification and Floristic Analysis

2.2.2. Phytoecology

3. Results

3.2. Plant Richness and Floristic Analysis

| Blocs | Transects | Abundant Species | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bloc 1 | F1 | T6, T14, T4, T2, T5, T1, T56, T7 |

Quercus ilex, Anchusa azurea, Astragalus incanus, Bromus madritensis, Campanula filicaulis, Catananche caerulea, Echinops spinosissimus, Lactuca tenerrima, Silene vulgaris, asperula hirsuta, Picnomon acarna, |

| F2 | T34, T36, T32, T15, T8, T35, T31, T10, T25, T9, T45, T18, T11 |

Galium tricornicum, Papaver rhoeas, Bromus madritensis, Quercus ilex, Anchusa azurea, Medicago minima, Mantisalca salmantica, Plantago afra, Scolymus hispanicus, Beta macrocarpa, Medicago monspeliaca, Silene vulgaris, Sonchus asper | |

| F3 | T3, T13, T29, T17, T57, T39, T20, T23, T19, T24, T22, T16 | Quercus ilex, Hordeum murinum, Asphodelus macrocarpus, Galium tricornicum, Romulea bulbocodium, Anchusa azurea, asperula hirsuta, Astragalus hamosus, Echinaria capitata, Echinops spinosissimus, Ononis cristata, Salvia verbenaca | |

| Bloc 2 | F4 | T146, T78, T145, T51, T55, T27, T42, T46 | Quercus ilex, Clematis cirrhosa, Echinops spinosissimus, Arthemisia herba alba, Bromus madritensis, Buxus balearica, Carlina hispanica, Chamaerops humilis,Convolvulus althaeoides, Hordeum murinum Juniperus phoenicea |

| F5 | T100, T47, T41, T107, T85, T30, T101, T86, T125, T43, T106, T99, T82, T105 | Juniperus phoenicea, Anchusa azurea, Quercus ilex, Silene vulgaris, Alyssum alyssoides, Asperula arvensis, Atractylis cancellata, Avena fatua, Dactylis glomerata ; Erodium cicutarium, Hedypnois rhagadioloides, Isatis tinctoria, Lactuca tenerrima, Medicago minima, Papaver rhoeas, schismus barbatus, Torilis leptophylla | |

| F6 | T89, T69, T120, T75, T94, T62, T67, T68, T72, T118, T129, T81, T61, T92, T96, T66, T71, T95, T73, T104, T63, T81, T49, T88, T91, T93, T90, T101, T64, T93, T63 | Juniperus phoenicea, Stipellula capensis, Chamaerops humilis, Bromus madritensis, Pistacia lentiscus, Atractylis cancellata, A. sterilis, Torilis nodosa, Ceratonia siliqua, Cladanthus arabicus, Sonchus oleraceus, Tetraclinis articulata, Ziziphus lotus, Euphorbia resinifera… | |

| F7 | T139, T111, T133, T102 T77, T98, T28 T84, T87, T80, T103, T110, T144, T130, T131, T121, T49, T46 | Juniperus phoenicea, Picnomon acarna, Pinus halepensis, Buxus balearica, Quercus ilex, Thymus algeriensis, Lactuca tenerrima, Thymus saturejoides, Ajuga iva, Chondrella jencea, Crambe filiformis, Dactylis glomerata, Deverra scoparia, Genista scorpius, Globularia nainii, Lactuca viminea, Phagnalon saxatile, Phillyrea angustifolia, Salvia verbenaca, Teucrium polium, Thymus zygis | |

| Bloc 3 | F8 | T127, T140, T117, T135, T151, T126 | Pinus halepensis, Globularia nainii, Buxus balearica, C. corymbosa, Centaurea melitensis, Cistus creticus, Euphorbia niceensis, Fraxinus angustifolia, Fumana ericoides, Narsturia officinalis, Polygala balansae, Sedum sediforme, Stipellula capensis |

| F9 | T44, T148, T132, T150 | Thymus zygis, Anarrhinum fruticosum, Globularia nainii, Arbutus unedo, Astragalus incanus, Euphorbia taurinensis, Ononis pusilla, Fraxinus angustifolia, Schismus barbatus, Ajuga iva, | |

| F10 | T141, T143, T116, T136, T142, 128, | Juniperus phoenicea, Xanthium spinosus, Ajuga iva, Andryala integrifolia, Capparis spinosa, Crambe filiformis, Dittrichia viscosa, Erodium cicutarium, Globularia alypum, Melilotus sulcatus, Mentha peligium, Mentha suaveolens, Nerium oleander, Pinus halepensis, Pistacia lentiscus, Polypogon minspeliensis, Schismus barbatus | |

| F11 | T124, T119, T112, T149, T137, T108, T114, T113, T115, T147 | Globularia nainii, Hirschfeldia incana, Lythrum junceum, Pinus halepensis, Pistacia lentiscus, Polygala balansae, Teucrium polium, Bombycilaena erecta, Centaurea calcitrapa, Chondrella jencea, Cistus creticus, Juniperus phoeniceae, Nerium oleander, Populus negra, Schismus barbatus, Veronica polita, Anarrhinum fruticosum, Centaurea melitensis, Cistus albidus, Dianthus nudiflorus, Dittrichia viscosa | |

| Bloc 4 | F12 | T52, T54, T160, T53, T50, T194, T196, T161 | Euphorbia niceensis, Fraxinus angustifolia, Polycarpon tetraphyllum, Bellis annua, Eryngium campestre, Lactuca tenerrima, poclama brevifolia, Quercus, Astragalus incanus, Bromus madritensis, Crambe filiformis, Euphorbia terracina, Globularia nainii, Marrubium ayardii |

| F13 | T175, T162, T195, T190 | Teucrium chamaedrys, alyssum spinosum, Polycarpon tetraphyllum, Arenaria pungens, asperula hirsuta, Bupleurum spinosus, Cerastium arvense, Helianthemum cenereum, Jurinea humilis, Minuartia funkii, Thymelaea virgata, Thymus zygis | |

| F14 | T193, T58, T38, T197, T37, T59 | Quercus ilex, Astragalus granatensis, Campanula filicaulis, Ononis spinosa, Polycarpon tetraphyllum, Scutellaria orientalis, Teucrium chamaedrys, Aegilops geniculate, asperula hirsuta, Bromus madritensis, Cirsium acaule, Convolvulus lineatus, Coronilla minima, Crataegus lacinata | |

| Bloc 5 | F15 | T187, T173, T164, T178 |

Cytisus balansae, Euphorbia niceensis, alyssum spinosum, Hirschfeldia incana, Anthyllis vulneraria Arthemisia herba alba Buxus balearica, Cirsium dyris, Coronilla minima, Delphinium gracile, Helianthemum apenninum, Juniperus thurifera, Jurinea humilis, Ormenis scariosa, Quercus ilex, Scorzonera caespitosa |

| F16 | T163, T167, T185, T165 |

Arthemisia herba alba, Ormenis scariosa, Euphorbia niceensis, Sanguisorba minor, alyssum spinosum, Asperula cynanchica, Avena barbata, Bupleurum spinosum, Coronilla minima, Erinacea Anthyllis, Helianthemum cinereum, Hieracium pseudopilosella, Vella maierii |

|

| F17 | T172, T188, T181, T189 |

Euphorbia niceensis Ribes uva-crispa, Coronilla minima, Erinacea Anthyllis, Alyssum serpyllifolium, Buxus balearica ; Cytisus balansae, Juniperus thurifera, Raffenaldia platycarpa, Scorzonera angustifolia, Scorzonera caespitosa, Thymelaea virgata, |

|

| Bloc 6 | F18 | T179, T171, T184 |

Alyssum spinosum, Scorzonera caespitosa, Thymus pallidus, Arenaria pungens, Carduncellus atractyloides, Centaurea takredensis, Convolvulus sabatius, Delphinium gracile, Erinacea Anthyllis, Euphorbia niceensis, Euphorbia sagitalis, Juniperus thurifera |

| F19 | T186, T191, T180, T177, T155, T152, T174 | Alyssum spinosum, Bupleurum spinosum, Carduncellus atractyloides, Centaurea takredensis, Cytisus balansae, Erinacea Anthyllis, Euphorbia niceensis, Vella maierii, Ribes uva-crispa, Arenaria serpyllifolia, Arenaria pungens, Berberis vulgaris, Bupleurum atlanticum, Cirsium dyris, Delphinium gracile, Juniperus thurifera, Minuartia funkii, Ormenis scariosa, Prunus prostrata, Rahmnus liscoides, Thymus pallidus | |

| F20 | T183, T153, T168 |

Euphorbia niceensis, Alyssum spinosum Erinacea Anthyllis, Juniperus thurifera L. Scorzonera caespitosa, Vella mairii, Arthemisia herba alba, Bupleurum, atlanticum, Bupleurum spinosum, Convolvulus lineatus, Ormenis scariosa, |

|

| F21 | T176, T154, T182, T170, T157, T192, T156 | Arenaria pungens, Valla mairii, alyssum spinosum, Erinacea Anthyllis, Bupleurum spinosum, Clinopodium alpinum, Cytisus balansae, Euphorbia niceensis, Euphorbia megatlantica, Scorzonera caespitosa, Berberis vulgaris, Coronilla minima, Ormenis scariosa, Papaver atlanticum, Ruta montana, Stipa nitans | |

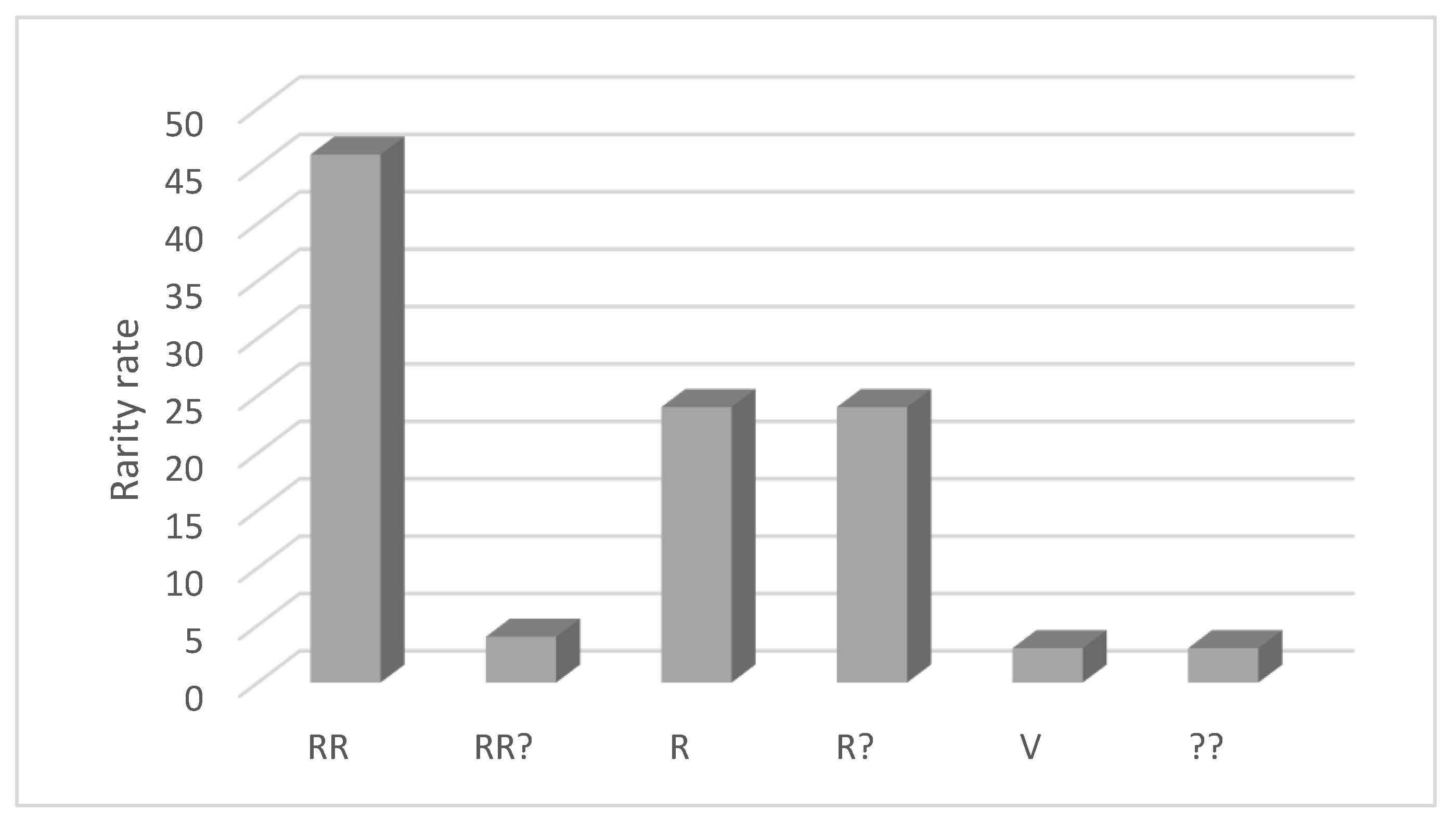

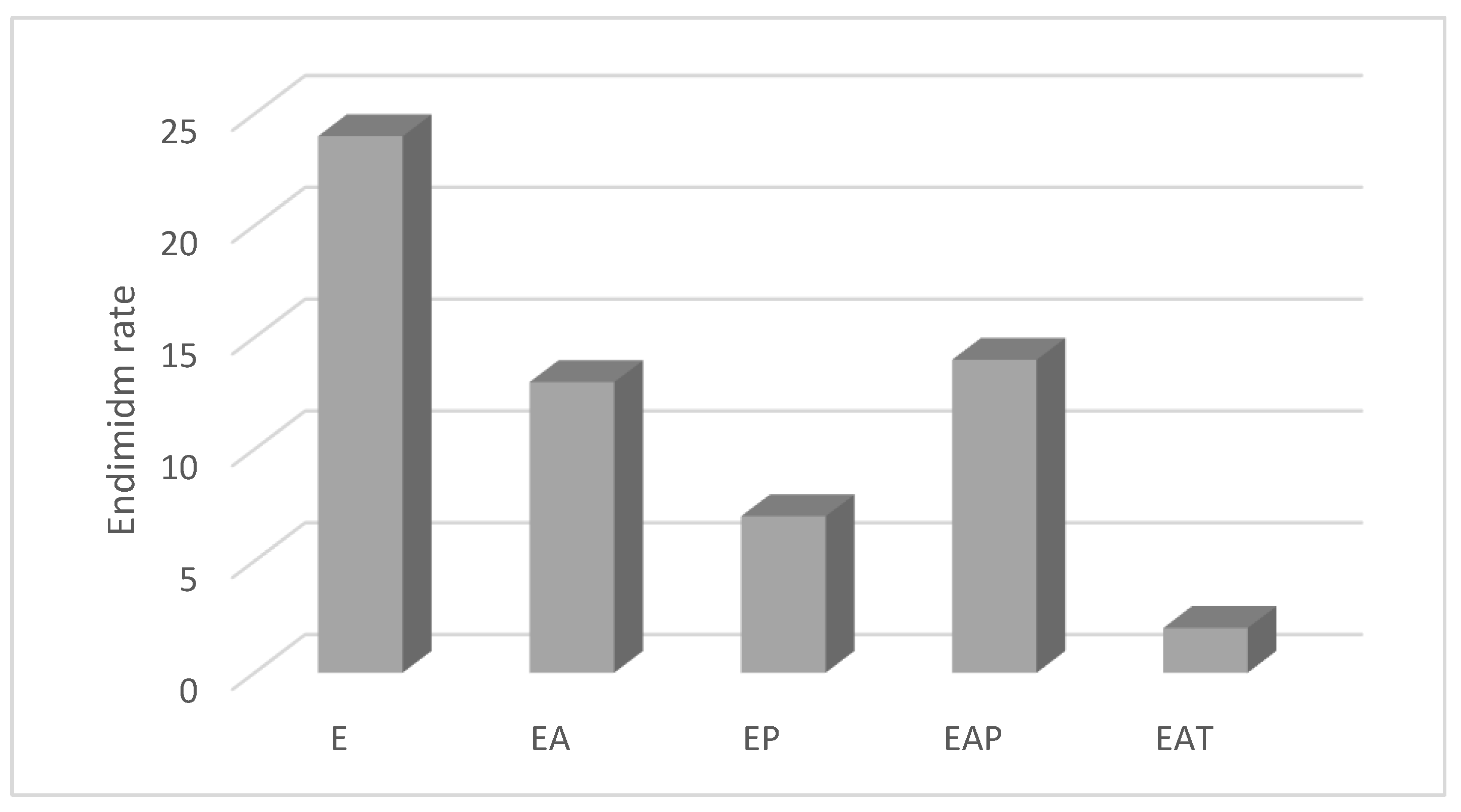

3.2. Endemism and Rarity

3.3. Rainfall Distribution

3.4. Temperature

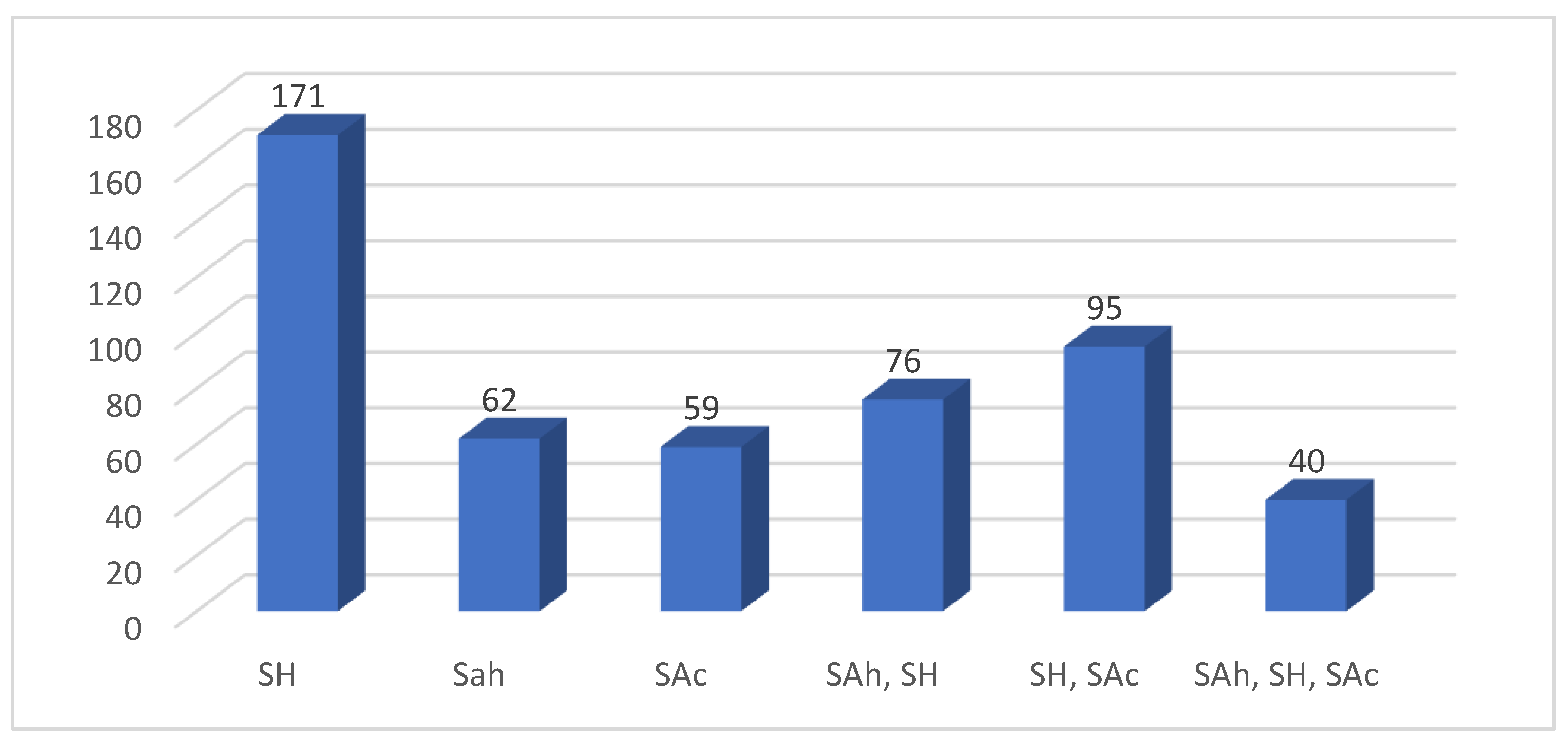

3.5. Bioclimatic Zones

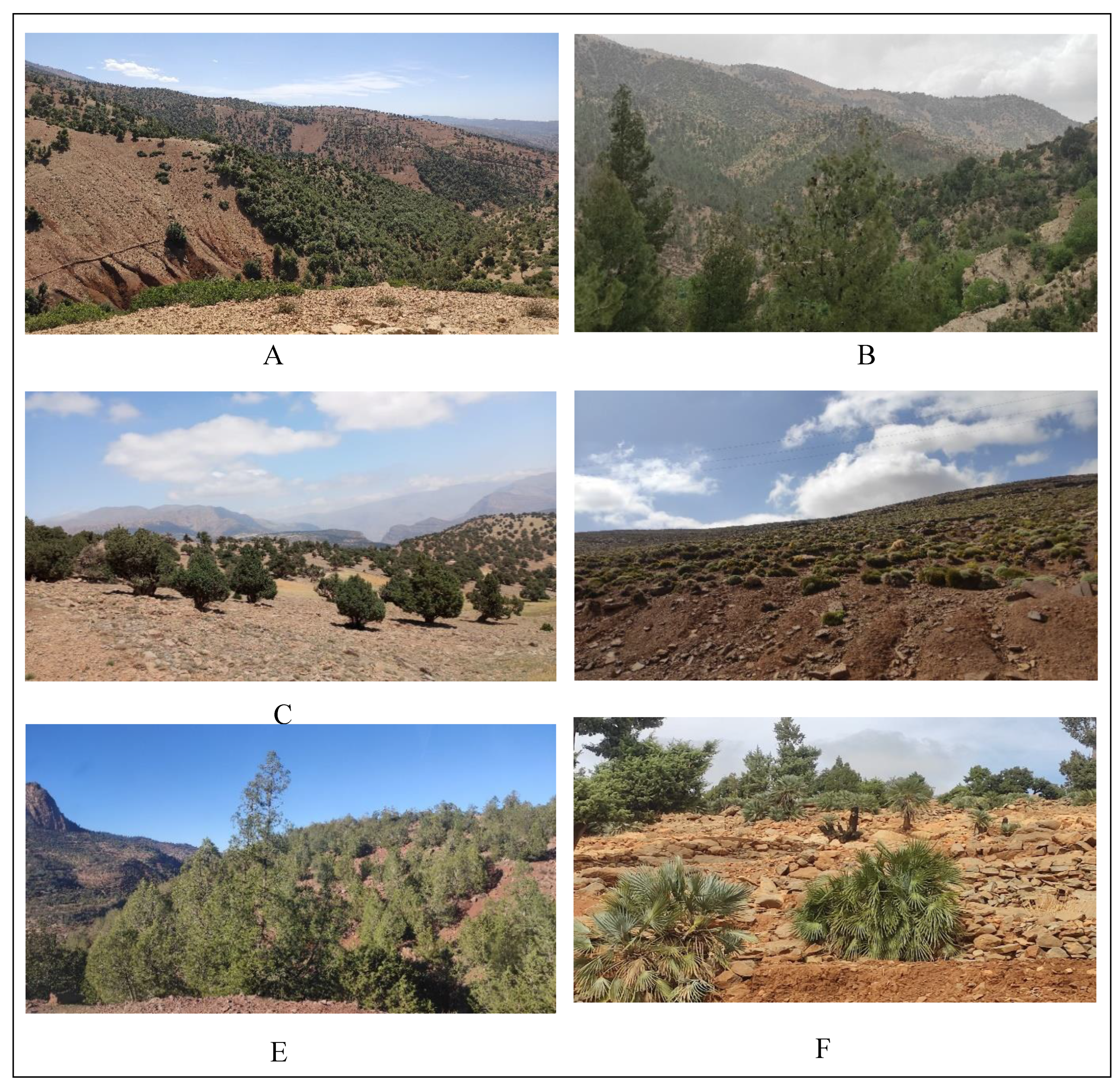

3.6. The Vegetation Cover

3.7. The Vegetation Levels and Associated Vegetation

| Symbol | Dominant Species | Companion Species | Altitude | Bioclimatic Stage | Vegetation Zone | Tmin & Tmax | Precipitation | Substrate type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Quercus ilex, Anchusa azurea, Astragalus incanus | Bromus madritensis, Campanula filicaulis, Catananche caerulea | 544–1000 | Semi-arid fresh | Supra-Mediterranean | -4°C, 30°C | 300–600 mm | Limstones |

| F2 | Galium tricornicum, Quercus ilex, Anchusa azurea | Bromus madritensis, Medicago minima, Silene vulgaris | 800–1500 | Semi-arid fresh | Meso-Mediterranean and Supra-Mediterranean | -2°C, 28°C | 350–650 mm | Limstones |

| F3 | Quercus ilex, Hordeum murinum, Asphodelus macrocarpus | Galium tricornicum, Romulea bulbocodium, Anchusa azurea | 1000–1900 | Subhumid fresh | Supra-Mediterranean | -5°C, 32°C | 400–700 mm | Limstones |

| F4 | Quercus ilex, Clematis cirrhosa, Echinops spinosissimus | Artemisia herba-alba, Juniperus phoenicea | 1200–2100 | Subhumid fresh | Meso-Mediterranean and Supra-Mediterranean | -3°C, 29°C | 250–500 mm | Limstones |

| F5 | Juniperus phoenicea, Anchusa azurea, Quercus ilex | Silene vulgaris, Avena fatua, Dactylis glomerata | 1600–2000 | Semi-arid fresh | Supra-Mediterranean and Montane Mediterranean | -6°C, 30°C | 400–650 mm | Limstones |

| F6 | Juniperus phoenicea, Stipellula capensis, Chamaerops humilis | Atractylis cancellata, Euphorbia resinifera | 1500–2200 | Subhumid fresh | Montane Mediterranean | -8°C, 25°C | 350–600 mm | Clays and sandstone |

| F7 | Juniperus phoenicea, Pinus halepensis, Buxus balearica | Thymus algeriensis, Lactuca tenerrima, Genista scorpius | 1800–2400 | Semi-arid cold | Montane Mediterranean | -7°C, 22°C | 400–700 mm | Clays and limestone conglomerates |

| F8 | Pinus halepensis, Globularia nainii, Buxus balearica | Centaurea melitensis, Cistus creticus, Euphorbia niceensis | 1900–2500 | Semi-arid cold | Montane Mediterranean | -10°C, 15°C | 200–400 mm | Clays and limesrones |

| F9 | Thymus zygis, Anarrhinum fruticosum, Globularia nainii | Arbutus unedo, Astragalus incanus, Ononis pusilla | 1700–2800 | Semi-arid very cold | Montane Mediterranean | -8°C, 20°C | 250–500 mm | Limestones and rocky limestones |

| F10 | Juniperus phoenicea, Xanthium spinosus, Ajuga iva | Capparis spinosa, Crambe filiformis, Nerium oleander | 1500–2200 | Subhumid fresh | Supra-Mediterranean | -5°C, 28°C | 300–600 mm | Clays and sandstones |

| F11 | Globularia nainii, Hirschfeldia incana, Lythrum junceum | Pinus halepensis, Polygala balansae, Teucrium polium | 1700–3000 | Semi-arid very cold | Montane Mediterranean | -9°C, 18°C | 300–500 mm | Clays |

| F12 | Euphorbia niceensis, Fraxinus angustifolia, Polycarpon tetraphyllum | Bellis annua, Lactuca tenerrima, Quercus ilex | 1400–2400 | Semi-arid cold | Supra-Mediterranean | -4°C, 28°C | 350–600 mm | Limestones |

| F13 | Teucrium chamaedrys, Alyssum spinosum, Polycarpon tetraphyllum | Arenaria pungens, Bupleurum spinosus, Cerastium arvense | 1700–3000 | Semi-arid very cold | Montane Mediterranean | -8°C, 20°C | 300–500 mm | Limestones, marls and dolomites |

| F14 | Quercus ilex, Astragalus granatensis, Campanula filicaulis | Ononis spinosa, Polycarpon tetraphyllum, Teucrium chamaedrys | 1800–3100 | Semi-arid very cold | Montane Mediterranean | -9°C, 18°C | 300–600 mm | Limestones |

| F15 | Cytisus balansae, Euphorbia niceensis, Alyssum spinosum | Hirschfeldia incana, Cirsium dyris, Coronilla minima | 1800–3200 | Semi-arid very cold | Meso-Mediterranean | -4°C, 26°C | 350–600 mm | Limestones |

| F16 | Artemisia herba-alba, Ormenis scariosa, Euphorbia niceensis | Sanguisorba minor, Alyssum spinosum, Bupleurum spinosus | 2000–3500 | Semi-arid extremely cold | Montane Mediterranean | -7°C, 25°C | 400–650 mm | Limestones |

| F17 | Euphorbia niceensis, Ribes uva-crispa, Coronilla minima | Erinacea anthyllis, Alyssum serpyllifolium, Juniperus thurifera | 1800–3500 | Semi-arid extremely cold | Montane Mediterranean | -10°C, 18°C | 300–600 mm | Limestones |

| F18 | Alyssum spinosum, Scorzonera caespitosa, Thymus pallidus | Arenaria pungens, Carduncellus atractyloides, Euphorbia niceensis | 2000–3708 | Semi-arid extremely cold | Montane Mediterranean | -12°C, 15°C | 200–400 mm | Limestones |

| F19 | Alyssum spinosum, Bupleurum spinosum, Carduncellus atractyloides | Cytisus balansae, Erinacea anthyllis, Euphorbia niceensis | 2000–3708 | Semi-arid extremely cold | Montane Mediterranean | -10°C, 17°C | 250–500 mm | Limestones |

| F20 | Euphorbia niceensis, Alyssum spinosum, Erinacea anthyllis | Juniperus thurifera, Vella mairii, Ormenis scariosa | 2000–3708 | Semi-arid extremely cold | Montane Mediterranean | -9°C, 16°C | 200–400 mm | Limestones |

| F21 | Arenaria pungens, Vella mairii, Alyssum spinosum | Erinacea anthyllis, Bupleurum spinosum, Cytisus balansae | 2000–3708 | Semi-arid extremely cold | Montane Mediterranean | -11°C, 14°C | 200–400 mm | Limestones |

4. Discussion:

4.1. Floristic Richness

4.2. Phytoecology

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achhal, A., Akabli, A., Barbero, M., Benabid, A., M’Hirit, O., Peyre, C., Quézel, P. & Rivas-Martinez, S. (1979a). A propos de la valeur bioclimatique et dynamique de quelques essences forestières au Maroc. Ecologia Mediterranea, 5(1), 211–249. [CrossRef]

- Achhal, A., Akabli, A., Barbero, M., Benabid, A., M’Hirit, O., Peyre, C., Quézel, P. & Rivas-Martinez, S. (1979b). À propos de la valeur bioclimatique et dynamique de quelques essences forestières au Maroc. Ecologia Mediterranea, 5(1), 211–249. [CrossRef]

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. (2009). An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 161(2), 105–121. [CrossRef]

- APG, Chase, M. W., Christenhusz, M. J. M., Fay, M. F., Byng, J. W., Judd, W. S., Soltis, D. E., Mabberley, D. J., Sennikov, A. N., Soltis, P. S. & Stevens, P. F. (2016). An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 181(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Barbero, M. & Quézel, P. (1976). Les groupements forestiers de Grèce centro-méridionale. Ecologia Mediterranea, 2(1), 3–86.

- Benabid, A. (1985). Les écosystèmes forestiers, préforestiers et presteppiques du Maroc : Diversité, répartition biogéographique et problèmes posés par leur aménagement. Forêt Méditerranéenne, 7, 53–64.

- Benabid, Abdelmalek. (1982). Bref aperçu sur la zonation altitudinale de la végétation climacique du Maroc. : : Ecologia Mediterranea, 8(1–2), 301–315.

- Benabid, Abdelmalek. (1985). Les écosystèmes forestiers, préforestiers et presteppiques du Maroc: Diversité, répartition biogéographique et problèmes posés par leur aménagement. Forêt Méditerranéenne, 7(1), 53–64.

- Benryane, M. A., Belqadi, L., Bounou, S. & Birouk, A. (2022). ANALYSE DE LA MISE EN ŒUVRE DU PROTOCOLE DE NAGOYA AU MAROC: IMPORTANCE ET LIMITES DE LA GOUVERNANCE DE LA BIODIVERSITE. Revue Des Études Multidisciplinaires En Sciences Économiques et Sociale, 7(3), 167–196.

- Bernard, D. (2015). Nouvelles considérations sur les phytoclimats du Maroc. Application au Maroc oriental. Matériaux Orthoptériques et Entomocénotiques, 20, 97–106.

- Bureau, D., Bureau, J.-C. & Schubert, K. (2020). No Title. Notes du conseil d’analyse économique, 59(5), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Bussard, J., Martin, S., Monbaron, M., Reynard, E. & El Khalki, Y. (2022). Geomorphological landscapes of the Central High Atlas (Morocco): Educative potential and resources for interpretation. GEOMORPHOLOGIE-RELIEF PROCESSUS ENVIRONNEMENT, 28(3), 173–185.

- Bussard, J., Martin, S., Monbaron, M., Reynard, E. & Khalki, Y. El. (2022). Les paysages géomorphologiques du Haut Atlas central (Maroc): Potentiel éducatif et éléments pour la médiation scientifique. Géomorphologie: Relief, Processus, Environnement, 28(3), 173–185.

- Chiarucci, A., Bacaro, G. & Scheiner, S. M. (2011). Old and new challenges in using species diversity for assessing biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1576), 2426–2437. [CrossRef]

- Cuttelod, A., García, N., Malak, D. A., Temple, H. J. & Katariya, V. (2009). The Mediterranean: A biodiversity hotspot under threat. Wildlife in a Changing World–an Analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 89(9), 1–4.

- Daget, P. (1977). Le bioclimat méditerranéen : Analyse des formes climatiques par le système d’Emberger. Vegetatio, 34, 87–103. [CrossRef]

- Damiani, M., Sinkko, T., Caldeira, C., Tosches, D., Robuchon, M. & Sala, S. (2023). Critical review of methods and models for biodiversity impact assessment and their applicability in the LCA context. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 101, 107134. [CrossRef]

- Defaut, B. (2015). Nouvelles considérations sur les phytoclimats du Maroc. Application au Maroc oriental. Matériaux Orthoptériques et Entomocénotiques, 20, 97–106.

- Derneği, D. (2010). Ecosystem Profile: Mediterranean Basin Biodiversity Hotspot. BirdLife International, Monaco, pp. 259.

- El Alami, A., Fattzh, A. & Bouzekraoui, H. (2021). Biodiversity, an essential component for the M’goun global geopark development (Morocco)-An overview. Journal of Analytical Sciences and Applied Biotechnology, 3(2), 103–106.

- Fennane, M. (1998). Catalogue des plantes vascularies rares, menacées ou endémiques du Maroc. Bocconea, 8, 5–243.

- Fennane, Mohamed & De Montmollin, B. (2015). Réflexions sur les critères de l’UICN pour la Liste rouge: Cas de la flore marocaine. Bulletin de l’Institut Scientifique, Rabat, 37, 1–11.

- Fennane, Mohamed & Ibn Tattou, M. (2012). Statistiques et commentaires sur l ’ inventaire actuel de la flore vasculaire du Maroc. Bulletin de l’Institut Scientifique, Rabat, Section Sciences de La Vie, 34(1), 1–9.

- Fennane, Mohamed & Tattou, M. I. (1998). Catalogue des plantes vasculaires rares , menacées ou endémiques du Maroc. Bocconea, 8, 5–243.

- Fougrach, H., Badri, W. & Malki, M. (2007). Flore vasculaire rare et menacée du massif de Tazekka (région de Taza, Maroc). Bulletin de l’Institut Scientifique, Rabat, Section Sciences de La Vie, 29, 1–10.

- Frizon de Lamotte, D., Zizi, M., Missenard, Y., Hafid, M., Azzouzi, M. El, Maury, R. C., Charrière, A., Taki, Z., Benammi, M. & Michard, A. (2008). The Atlas System. In A. Michard, O. Saddiqi, A. Chalouan & D. F. de Lamotte (Eds.), Continental Evolution: The Geology of Morocco: Structure, Stratigraphy, and Tectonics of the Africa-Atlantic-Mediterranean Triple Junction (pp. 133–202). Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Gharnit, Y., Outourakht, A., Boulli, A. & Hassib, A. (2023). Biodiversity, Autecology and Status of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants in Geopark M’Goun (Morocco). Annali Di Botanica, 13, 39–54. [CrossRef]

- Gharnit, Youssef, Moujane, A., Outourakhte, A., Hassan, I., Amraoui, K. El, Hasib, A. & Boulli, A. (2025). Plant Richness, Species Assessment, and Ecology in the M’goun Geopark Rangelands, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 98, 357–376. [CrossRef]

- Gharnit, Youssef, Outourakhte, A., Moujane, A., Ikhmerdi, H., Hasib, A. & Boulli, A. (2024). Habitat diversity, ecology, and change assessment in the geoparc M’goun in High Atlas Mountains of Morocco. Geology, Ecology, and Landscapes, In Press, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Green, M. J. B., How, R., Padmalal, U. & Dissanayake, S. R. B. (2009). The importance of monitoring biological diversity and its application in Sri Lanka. Tropical Ecology, 50(1), 41.

- Ibn Tattou, M. & Fennane, M. (1989). Aperçu historique et état actuel des connaissances sur la flore vasculaire du Maroc “. Bull. Inst. Sci, 13, 85–94.

- Ilmen, R. & Benjelloun, H. (2013). Les écosystèmes forestiers marocains à l ’ épreuve des changements climatiques. Forêt Méditerranéenne, XXXIV(3), 195–208.

- Lindenmayer, D., Woinarski, J., Legge, S., Southwell, D., Lavery, T., Robinson, N., Scheele, B. & Wintle, B. (2020). A checklist of attributes for effective monitoring of threatened species and threatened ecosystems. Journal of Environmental Management, 262, 110312. [CrossRef]

- Mace, G. M., Norris, K. & Fitter, A. H. (2012). Biodiversity and ecosystem services: A multilayered relationship. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 27(1), 19–26. [CrossRef]

- Maliha, N. S., Chaloud, D. J., Kepner, W. G. & Sarri, S. (2008). Regional Assessment of Landscape and Land Use Change in the Mediterranean Region BT - Environmental Change and Human Security: Recognizing and Acting on Hazard Impacts. In P. H. Liotta, D. A. Mouat, W. G. Kepner & J. M. Lancaster (Eds.), Environmental change and human security: Recognizing and acting on hazard impacts (pp. 143–165). Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht.

- Mauz, I. & Granjou, C. (2010). No Title. Sciences Eaux & Territoires, Numéro 3(3), 10–13. [CrossRef]

- Médail, F. & Diadema, K. (2006). Biodiversité végétale méditerranéenne. Annales de Géographie, 115, 618–640.

- Medail, F. & Quezel, P. (1997). Hot-spots analysis for conservation of plant biodiversity in the Mediterranean Basin. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 84(1), 112–127. [CrossRef]

- Menioui, M. (2018). Biological diversity in Morocco. In Global Biodiversity (pp. 133–171). Apple Academic Press, New York, pp 452.

- Mittermeier, R. A., Myers, N., Mittermeier, C. G. & Robles Gil, P. (1999). Hotspots: Earth’s biologically richest and most endangered terrestrial ecoregions. CEMEX, SA, Agrupación Sierra Madre, SC. Washington. 431 pp.

- Mostakim, L., Guennoun, F. Z., Fetnassi, N. & Ghamizi, M. (2021). Analysis of floristic diversity of the forest ecosystems of the Zat valley-High Atlas of Morocco: Valorization and conservation perspectives. Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Experimental Therapeutics, 5, 126–135. [CrossRef]

- Ozenda, P. (1975). Sur les étages de végétation dans les montagnes du bassin méditerranéen. Doc. Cart. Ecol., 16, 1–32.

- Ozenda, P. (1982). Les végétaux dans la biosphère. Revue de Géographie Alpine, 6, 310–311.

- Pauchard, A., Meyerson, L. A., Bacher, S., Blackburn, T. M., Brundu, G., Cadotte, M. W., Courchamp, F., Essl, F., Genovesi, P. & Haider, S. (2018). Biodiversity assessments: Origin matters. PLoS Biology, 16(11), e2006686. [CrossRef]

- Quézel, P. & Barbero, M. (1982). Definition and characterization of Mediterranean-type ecosystems. Ecologia Mediterranea, 8(1), 15–29. [CrossRef]

- Séné, A. M. (2010). Perte et lutte pour la biodiversité: Perceptions et débats contradictoires. VertigO-La Revue Électronique En Sciences de l’environnement, 10, 1–9.

- Taïbi, A. N., Hannani, M. El, Khalki, Y. El & Ballouche, A. (2019). Les parcs agroforestiers d’Azilal (Maroc) : Une construction paysagère pluri-séculaire et toujours vivante. Revue de Géographie Alpine, 107(3), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Teixidor-Toneu, I., M’Sou, S., Salamat, H., Baskad, H. A., Illigh, F. A., Atyah, T., Mouhdach, H., Rankou, H., Babahmad, R. A., Caruso, E., Martin, G. & D’Ambrosio, U. (2022). Which plants matter? A comparison of academic and community assessments of plant value and conservation status in the Moroccan High Atlas. Ambio, 51(3), 799–810. [CrossRef]

- Underwood, E. C., Viers, J. H., Klausmeyer, K. R., Cox, R. L. & Shaw, M. R. (2009). Threats and biodiversity in the mediterranean biome. In Diversity and Distributions (Vol. 15, Issue 2, pp. 188–197). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, P. (2020). The Mediterranean Floristic Region: High Diversity of Plants and Vegetation Types (M. I. Goldstein & D. A. B. T.-E. of the W. B. DellaSala (eds.); pp. 602–616). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, K. J., Porensky, L. M., Wilkerson, M. L., Balachowski, J., Peffer, E., Riginos, C. & Young, T. P. (2010). Restoration ecology. Nature Education Knowledge, 3 (10), 66.

- Youssef, G., Abdelaziz, M., Aboubakre, O., Abdelali, B. & Aziz, H. (2024). Impact of climate and demographic changes on the vegetation of the M’goun Geopark UNESCO of Morocco (1984-2021). Investigaciones Geográficas, 81, 225–243. [CrossRef]

| Period | Tmin (min-max) en °C | Tmax (min-max) en °C | Precipitations (min-max) en mm | Q2 (min-max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960-1969 | -9,97 - 2,18 | 20,9- 30,83 | 369,67 - 658,68 | 42,63 - 77,62 |

| 1970-1979 | -9,37 - 3,12 | 23,5 - 34,42 | 350,32 - 605,81 | 37,92 - 66,91 |

| 1980-1989 | -10 - 2,34 | 23,5 - 34,63 | 295,56 - 506,28 | 31 - 54,39 |

| 1990-1999 | -9,74 - 2,89 | 23,87 - 35,17 | 307,88 - 541,58 | 32,34 - 58,25 |

| 2000-2009 | -8,86 - 2,39 | 24,42 - 35,65 | 309,58 - 533,49 | 32 - 57,67 |

| 2010-2019 | -9,39 - 3 | 24,60 -36,12 | 329,25 - 571,19 | 33,96 - 60,76 |

| Habitat | Altitude (m) | Tmin (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Precipitation (mm) | Bioclimate | Climatic Variation | Vegetation Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercus ilex | Up to 2800 | 5.61–6.26 | 18.69–19.33 | 299.01–548.25 | Semi-arid and subhumid | All variants | Supra-, Meso-, Thermo-, and Montane Mediterranean |

| Juniperus phoenicea | Up to 2000 | 6.92–7.88 | 19.95–20.56 | 313.2–571.99 | Semi-arid and subhumid | Except very cold and cold | Meso- and Thermo-Mediterranean |

| Pinus halepensis | Up to 2200 | 6.29–7.36 | 19.13–19.72 | 278.23–501.08 | Subhumid and semi-arid | Cool and cold | Supra- and Meso-Mediterranean |

| Xerophytes | Up to 3700 | 2.24–3.26 | 15.14–15.79 | 291.93–532.19 | Subhumid and semi-arid | Cold and very cold | Montane and Oro-Mediterranean |

| Chamaerops humilis | Up to 2000 | 6.62–7.69 | 20.98–21.43 | 302.59–545.73 | Subhumid and semi-arid | Cold | Supra-Mediterranean |

| Juniperus thurifera | Up to 2700 | 3.41–4.42 | 16.26–16.98 | 288.48–499.47 | Subhumid and semi-arid | Cold and very cold | Montane Mediterranean |

| Euphorbia resinifera | Up to 1800 | 8.05–9.06 | 21.69–22.13 | 305.13–552.85 | Semi-arid and subhumid | Moderate and cold | Meso-Mediterranean |

| Buxus sempervirens | Up to 3000 | 1.99–2.93 | 14.9–15.51 | 281.61–478.13 | Subhumid and semi-arid | Cold and very cold | Montane Mediterranean |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).