Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

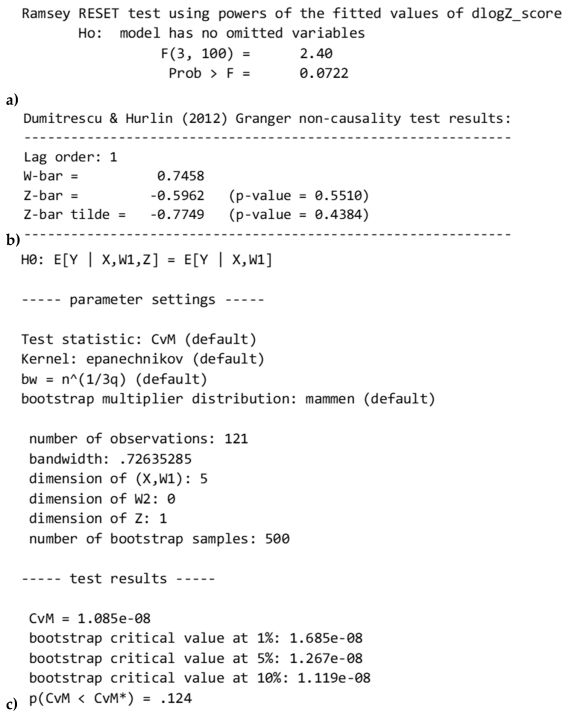

The study investigates the impact of climate risks on the financial sector stability of the selected SADC countries in the context of Angola, Malawi, Mozambique, Madagascar, Tanzania, Eswatini, Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, South Africa, Madagascar, and Zambia. Countries chosen for this study face climate-related shocks such as rising annual carbon dioxide emissions, affecting their agro-based economies and negatively impacting financial stability. The study aprovides insights into the risks and challenges associated with climate risk for the selected SADC countries. The study employed Panel-Corrected Standard Errors (PCSE) and Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) models to estimate the long-run parameters of climate risks' impact on the region's financial sector stability. The research confirms a negative and statistically significant long-run relationship between climate risk and financial sector stability in the SADC region. The research found carbon dioxide emissions to be statistically significant and have a negative impact on financial stability. The study recommends integrating climate-related risk into financial, supervision, and prudential regulations. It also recommends critical interventions in creating climate risk insurance products and availing incentives towards green investments to enhance financial sector resilience.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- Hypothesis 1: H0: Climate risk has no significant impact on the stability of the financial sector of SADC

- Hypothesis 2:H0: Climate risk has no significant impact on bank lending activities of SADC

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dependent Variable

3.2. Independent Variable

4. Results Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Empirical Results

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Policy Recommendations

5.3. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix 1. Pearson Pairwise Correlation Results, Unit Root Results and Cointegration Results

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) |

| (1) Z_score | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (2) LDR | 0.480* | 1.000 | |||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||||

| (3) CRI | 0.155* | 0.001 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (0.010) | (0.990) | ||||||||

| (4) NPL | -0.184* | -0.499* | 0.009 | 1.000 | |||||

| (0.043) | (0.000) | (0.921) | |||||||

| (5) CO2 | 0.076 | 0.768* | -0.079 | -0.301* | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.406) | (0.000) | (0.388) | (0.001) | ||||||

| (6) GDP_pc | 0.222* | 0.709* | 0.202* | -0.371* | 0.785* | 1.000 | |||

| (0.014) | (0.000) | (0.026) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| (7) EXR | 0.072 | -0.174 | -0.248* | 0.276* | -0.347* | -0.531* | 1.000 | ||

| (0.434) | (0.057) | (0.006) | (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| (8) Infl | -0.098 | -0.361* | -0.098 | 0.281* | -0.206* | -0.237* | 0.019 | 1.000 | |

| (0.286) | (0.000) | (0.283) | (0.002) | (0.023) | (0.009) | (0.836) | |||

| (9) AFF | -0.033 | -0.363* | -0.368* | 0.172 | -0.531* | -0.803* | 0.673* | 0.072 | 1.000 |

| (0.723) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.060) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.434) |

| Variables | LLC | CIPS | Fisher | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1(0) | 1(1) | 1(0) | 1(1) | 1(0) | 1(1) | |

| dlogZ_score | -5.3660 *** | -8.2678*** | -0.4945 | -1.6642** | 12.7217 | 60.4187*** |

| logCO2 | -2.1629*** | ….…. | -1.9827*** | ….… | 60.4957*** | ….… |

| logCRI | -3.3791*** | ….….. | -4.5253*** | ….…. | 88.9748*** | ….… |

| logAFF | -4.1308*** | …….. | -2.3279*** | …….. | 36.5061 | …….. |

| logGDP_pc | -6.7612*** | ….…. | -1.4825** | …….. | 32.9765** | …... |

| dlogNPL | -2.9820*** | -3.3300*** | 0.5465 | -1.9163* | 33.6102 | 17.5338 |

| Infl | -8.6621*** | ….….. | -2.4669*** | ….….. | 58.0166*** | ….… |

| logEXR | -6.9615*** | ….…. | -1.3093*** | ….….. | 51.5747*** | ….….. |

| LogCAR | -9.3178*** | ….…. | -2.8599*** | ….…. | 89.9057*** | ….…. |

| logBL_basst | -5.6998*** | ….….. | -1.9189*** | ….….. | 80.8102*** | ….… |

| logLIRR | -8.1089*** | ….…… | -1.3780** | ….…. | 69.0240*** | ….…. |

| logLDR | -1.4201** | -1.8162** | 20.0369 | 117.4387*** | ||

| Cointegration test | MPP_t | PP_t | ADF-t | Variance ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kao |

-5.9457 (0.0000) *** |

-5.5933 (0.0000) *** |

-3.6597 (0.0001) *** |

||

| Westlund | … | ……. | 3.0984 (0.0010)*** |

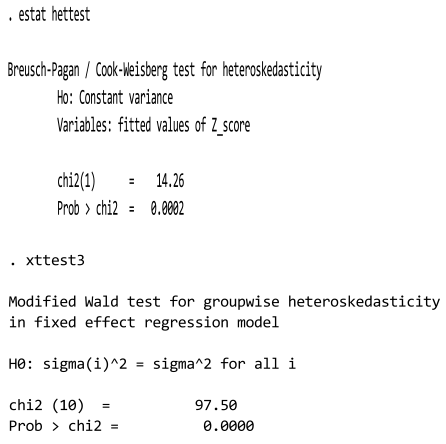

Appendix 2. Heteroscedasticity Test Results

Appendix 3. Hausman Test and Breusch Pagan Test

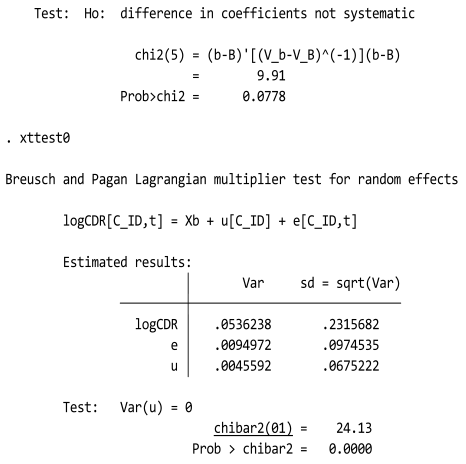

Appendix 4 Endogeneity Test

References

- Pereira, L., Climate change impacts on agriculture across Africa. Oxford research encyclopedia of environmental science, 2017.

- Carney, M., Resolving the climate paradox. Arthur Burns Memorial Lecture, Berlin, 2016. 22.

- Ozili, P.K., Managing climate change risk: A responsibility for politicians not Central Banks, in New Challenges for Future Sustainability and Wellbeing. 2021, Emerald Publishing Limited. p.

- Löyttyniemi, T., Integrating climate change into the financial stability framework1. Combatting Climate Change: a CEPR Collection, 2021: p. 24.

- Dunz, N., A. Naqvi, and I. Monasterolo, Climate transition risk, climate sentiments, and financial stability in a stock-flow consistent approach. Climate Sentiments, and Financial Stability in a Stock-Flow Consistent Approach (April 1, 2019), 2019.

- Curcio, D.; Gianfrancesco, I.; Vioto, D. Climate change and financial systemic risk: Evidence from US banks and insurers. J. Financial Stab. 2023, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglietta, M. and É. Espagne, Climate and finance systemic risks, more than an analogy?: the climate fragility hypothesis. 2016: CEPII, Centre d'etudes prospectives et d'informations internationales.

- Diallo, M.N.; Bah, M.M.; Ndiaye, S.N. Climate risk and financial stress in ECOWAS. J. Clim. Finance 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhang, B. Linking prosperity and sustainability: the economic impact of energy transition and financial stability. Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2024, 57, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, N., Financial stability and climate change. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 2020. 9(3): p. 27-43.

- Campiglio, E.; Dafermos, Y.; Monnin, P.; Ryan-Collins, J.; Schotten, G.; Tanaka, M. Climate change challenges for central banks and financial regulators. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, C., et al., Does climate change affect bank lending behavior? Economics Letters, 2022. 220: p. 110859.

- Wu, L.; Liu, D.; Lin, T. The Impact of Climate Change on Financial Stability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, S.; Men, W.; Sun, H. Impact of climate risk on financial stability: Cross-country evidence. Int. Rev. Financial Anal. 2024, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, C.; Dennis, B.; Gates, D.; Hancock, D.; Ignell, D.; Kiser, E.K.; Kotta, G.; Kovner, A.; Rosen, R.J.; Tabor, N.K. Climate Change and Financial Stability. FEDS Notes 2021, 2021.0. [CrossRef]

- Chabot, M.; Bertrand, J.-L. Climate risks and financial stability: Evidence from the European financial system. J. Financial Stab. 2023, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, T.; Ding, R.; Huan, X.; Zhang, Z. Climate risk and financial stability: evidence from syndicated lending. Eur. J. Finance 2024, 30, 2001–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, A.; Tiggeloven, T.; Lincke, D.; Koks, E.; Ward, P.; Hinkel, J. Risks on global financial stability induced by climate change: the case of flood risks. Clim. Chang. 2021, 166, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debels-Lamblin, É. and L. Jacolin, The impact of climate change in Sub-Saharan Africa: vulnerabilities, resilience and finance. Bulletin de la Banque de France, 2020. 230: p. 1-12.

- Aloui, D.; Gaies, B.; Hchaichi, R. Exploring environmental degradation spillovers in Sub-Saharan Africa: the energy–financial instability nexus. Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2023, 56, 1699–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Wang, X.; Ding, Y. The impact of climate change policies on financial stability of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1295951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K., Rustomjee, and A. Arevalo, Evolution of IMF Engagement on Climate Change. IEO Background Paper No. BP/24-01/06 (Washington: International Monetary Fund), 2024.

- Mugiyo, H., et al., El Niño’s effects on Southern African agriculture in 2023/24 and anticipatory action strategies to reduce the impacts in Zimbabwe. Atmosphere, 2023. 14(11): p. 1692.

- Cashin, P.; Mohaddes, K.; Raissi, M. Fair weather or foul? The macroeconomic effects of El Niño. J. Int. Econ. 2017, 106, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abor, J.Y. and D. Ofori-Sasu, The Future of Development Banks in Africa, in Perspectives on Development Banks in Africa: Case Studies and Emerging Practices at the National and Regional Level. 2024, Springer. p. 421-451.

- Robins, N., S. Dikau, and U. Volz, Net-zero central banking: A new phase in greening the financial system. 2021.

- Eckstein, D., V. Künzel, and L. Schäfer, The global climate risk index 2021. 2021: Bonn: Germanwatch.

- DeMenno, M.B., Environmental sustainability and financial stability: can macroprudential stress testing measure and mitigate climate-related systemic financial risk? Journal of Banking Regulation, 2023. 24(4): p. 445-473.

- Gütschow, J.; Jeffery, M.L.; Günther, A.; Meinshausen, M. Country-resolved combined emission and socio-economic pathways based on the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) and Shared Socio-Economic Pathway (SSP) scenarios. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 1005–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesolle, D., SADC policy paper on climate change: assessing the policy options for SADC member states. 2012: SADC Secretariat, Policy, Planning, Resource Mobilisation Directorate.

- Oman, W.; Salin, M.; Svartzman, R. Three tales of central banking and financial supervision for the ecological transition. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canton, H. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime—UNODC. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 240–244. [Google Scholar]

- FSB, F.S.B., 2023 Bank Failures: Preliminary lessons learnt for resolution. 2023.

- Campiglio, E., et al., Climate-related risks in financial assets. Journal of Economic Surveys, 2023. 37(3): p. 950-992.

- Lee, H., et al., IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. 2023.

- Baarsch, F.; Granadillos, J.R.; Hare, W.; Knaus, M.; Krapp, M.; Schaeffer, M.; Lotze-Campen, H. The impact of climate change on incomes and convergence in Africa. World Dev. 2020, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- milie, D.-L. and J. Luc, The impact of climate change in Sub Saharan Africa: vulnerabilities, resilience and finance [Impact du changement climatique sur l’Afrique subsaharienne: vulnérabilités, résilience et financements]. Bulletin de la Banque de France, 2020(230).

- Battiston, S.; Dafermos, Y.; Monasterolo, I. Climate risks and financial stability. J. Financial Stab. 2021, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, S., et al., ‘Climate value at risk’of global financial assets. Nature Climate Change, 2016. 6(7): p. 676-679.

- Weitzman, M.L. On Modeling and Interpreting the Economics of Catastrophic Climate Change. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2009, 91, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo-Bediako, E.; Takawira, O.; Choga, I. The impact of climate change on the resilience of banking systems in selected Sub-Saharan economies. Int. J. Appl. Econ. Finance Account. 2023, 17, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, G.M.; Fisseha, F.L. Does climate change affect the financial stability of Sub-Saharan African countries? Clim. Chang. 2024, 177, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tautiva, J.A.D.; Huaman, J.; Oliva, R.D.P. Trends in research on climate change and organizations: a bibliometric analysis (1999–2021). Manag. Rev. Q. 2022, 74, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, T.; Sahin, S.; Topaloglu, E.E.; Ege, I. Evaluating the Impact of Climate Risk on Financial Access and Stability in G20 Countries: A Panel Data Approach (2006-2017). J. Corp. governance, Insur. risk Manag. 2023, 10, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Febo, E.; Angelini, E.; Le, T. European Non-Performing Exposures (NPEs) and Climate-Related Risks: Country Dimensions. Risks 2024, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabil, M. Assessment of the Relationship among Climate Change, Green Finance and Financial Stability: Evidence from Emerging and Developed Markets. Int. J. Econ. Finance 2024, 16, p51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Yan, B.; Ling, R.; Jiang, H. Is climate change fueling commercial banks’ non-performing loan ratio? Empirical evidence from 31 provinces in China. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2024, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, K., H. Ichiue, and N. Shiraki, How Does Climate Change Interact with the Financial System?: A Survey. 2020: Bank of Japan Tokyo.

- Sun, L.; Fang, S.; Iqbal, S.; Bilal, A.R. Financial stability role on climate risks, and climate change mitigation: Implications for green economic recovery. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 33063–33074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.-T.; Tran, T.P.; Mishra, A.V. Climate risk and bank stability: International evidence. J. Multinatl. Financial Manag. 2023, 70-71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, B.N.; Akam, D.; Inuwa, N.; James, H.T.; Basila, D. Does globalization and energy usage influence carbon emissions in South Asia? An empirical revisit of the debate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 36190–36207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Gao, W. Climate risk and financial stability: the mediating effect of green credit. Finance Res. Lett. 2024, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. and H.R. Luo, How does financial inclusion affect bank stability in emerging economies? Emerging Markets Review, 2022. 51: p. 100876.

- Kamran, H.W., et al., Climate change and bank stability: The moderating role of green financing and renewable energy consumption in ASEAN. 2020.

- Klomp, J. Financial fragility and natural disasters: An empirical analysis. J. Financial Stab. 2014, 13, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machdar, N.M., Financial inclusion, financial stability and sustainability in the banking sector: The case of Indonesia. 2020.

- Pointner, W. and D. Ritzberger-Grünwald, Climate change as a risk to financial stability. Financial Stability Report, 2019(38): p. 30-45.

- Nieto, M.J., Banks, climate risk and financial stability. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 2019. 27(2): p. 243-262.

- Mufandaedza, S.M., The impact of Trade Liberalisation on mining sector Total Factor Productivity change of selected countries from SADC. 2021, North-West University (South Africa).

- Gujarati, D.N., Basic Econometrics 4th ed. 2002.

- Naseer, M.M.; Guo, Y.; Bagh, T.; Zhu, X. Sustainable investments in volatile times: Nexus of climate change risk, ESG practices, and market volatility. Int. Rev. Financial Anal. 2024, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, Y.; Ji, Q.; Guo, K.; Lucey, B. Climate impacts on the loan quality of Chinese regional commercial banks. J. Int. Money Finance 2023, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlona, T., et al., Climate Risk and Financial Stability: Evidence from Bank Lending. 2022, Working Paper.

- Nehrebecka, N. Climate Risk with Particular Emphasis on the Relationship with Credit-Risk Assessment: What We Learn from Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 8070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brik, H. Climate risk and financial stability: Assessing non-performing loans in Chinese banks. J. Risk Manag. Financial Institutions 2024, 17, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, O.R., Regional integration and industrialisation in the SADC. Regional Policy in the Southern African Development Community: p. 192.

- Garcia-Villegas, S.; Martorell, E. Climate transition risk and the role of bank capital requirements. Econ. Model. 2024, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelowa, A.; Hoch, S.; Weber, A.-K.; Kassaye, R.; Hailu, T. Mobilising private climate finance for sustainable energy access and climate change mitigation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Clim. Policy 2020, 21, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cyclone | Source | Year | |

| Cyclone Eline | Indian Ocean | 2000 | |

| Cyclone Japhet | Indian Ocean | 2003 | |

| Cyclone Galifo | Indian Ocean | 2003 | |

| Cyclone Dineo | Indian Ocean | 2016 November | 2017January |

| Cyclone Idai | Indian Ocean | 2019 | |

| Cyclone Eloise | Indian Ocean | 2021 | |

| Cyclone Chalane | Indian Ocean | 2021 | |

| Cyclone Gombe | Indian Ocean | 2021 | |

| Cyclone Batsirai | Indian Ocean | 2022 | |

| Cyclone Hermine | Atlantic Ocean | 2022 | |

| Cyclone Freddy | Indian Ocean | 2023 | |

| Cyclone Cheneso | Indian Ocean | 2023 |

| Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Z_score | Z_score -A measure of a financial system stability usually calculated as (ROA+(equity/assets))/sd(ROA); sd(ROA) is the standard deviation of ROA, calculated for country-years with no less than five bank-level observations. | Bank scope (2000-14) and Orbis (2015-20), Bureau van Dijk (BvD)-Global financial development database |

| LDR | Bank credit to bank deposit is a financial resource provided to the private sector by domestic money banks as a share of total deposits calculated as % | International Financial Statistics (IFS), International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank (2022) |

| CRI | Global Climate Risk Index-The index is constructed using four indicators, which include the number of deaths, number of deaths per 100000 inhabitants, the sum of losses in US$ in purchasing power parity (PPP) and losses per unit of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Global climate risk index, 2021). | German watch Global climate risk index, MunichRe Nat CatSERVICE (2006-2021) |

| CO2 | Carbon Emissions (metric tons per capita) | Available online at: https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ghg-emissions,World Bank (2023) |

| AFF | Agricultural Output-tones per hectare | World Bank (2022) |

| NPL | Non-performing Loans-Bank nonperforming loans to gross loans (%) | Financial Soundness Indicators Database (fsi.imf.org), International Monetary Fund (IMF) |

| Infl | Inflation | International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics and data files |

| GDP_pc | Gross Domestic Product per capita constant 2015 US$) | World Bank (2023) |

| CAR | Bank regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets (%) | Financial Soundness Indicators Database (fsi.imf.org), International Monetary Fund (IMF) |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| Z score | 121 | 14.411 | 6.355 | 4.268 | 27.018 |

| LDR | 121 | 72.632 | 17.843 | 32.044 | 119.064 |

| CRI | 121 | 68.899 | 29.993 | 2.67 | 132.33 |

| CO2 | 121 | 1.339 | 2.184 | .03 | 8.218 |

| Infl | 121 | 8.407 | 7.492 | -3.518 | 43.069 |

| EXR | 121 | 609.652 | 950.755 | 4.798 | 3787.754 |

| GDP pc | 121 | 2781.446 | 2509.495 | 324.828 | 8737.041 |

| NPL | 121 | 7.214 | 4.934 | .964 | 25.836 |

| CAR | 121 | 34.792 | 14.323 | 12.301 | 75.434 |

| AFF | 121 | 14.468 | 9.156 | 1.82 | 29.078 |

| Variable | CD-test | p-value | corr | abs(corr) |

| logZ_score | -1.940 | 0.053 | -0.07 | 0.33 |

| logCRI | 2.61 | 0.009 | 0.11 | 0.31 |

| logCO2 | 5.605 | 0.000 | 0.23 | 0.53 |

| logAFF | 3.362 | 0.001 | 0.14 | 0.49 |

| logEXR | 22.075 | 0.000 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| log NPL | 2.495 | 0.013 | 0.10 | 0.47 |

| logGDP_pc | 6.757 | 0.000 | 0.27 | 0.52 |

| Infl | 2.965 | 0.003 | 0.12 | 0.29 |

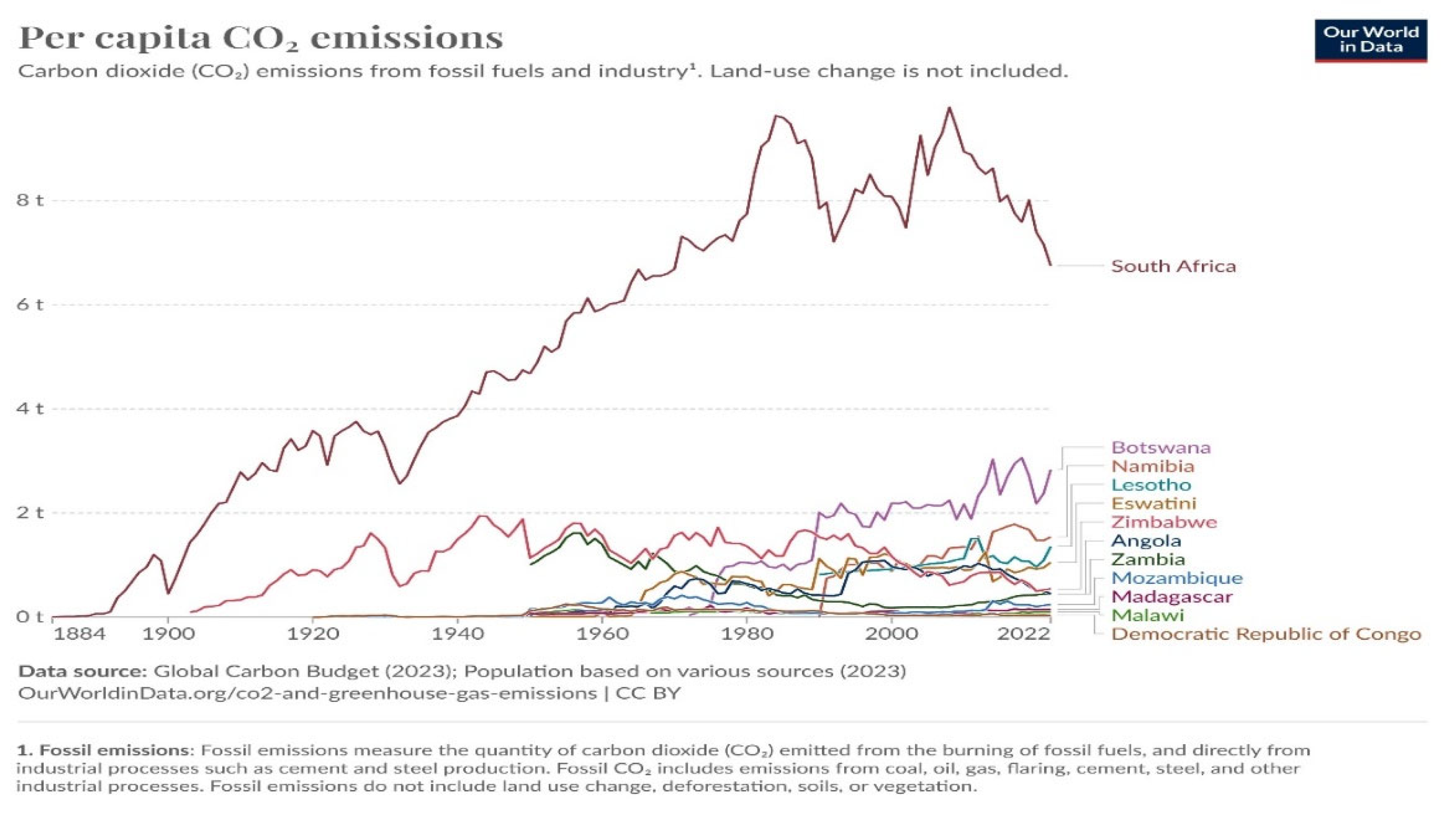

| (Z_score) | (Z_score) | Robustness | (Z_score) | |

| VARIABLES | PCSE Model 1 | PCSE Model 2 | FGLS Model 1 | FGLS Model 2 |

| logCRI | -3.455* | -3.455** | -3.455** | -2.874*** |

| (1.770) | (1.559) | (1.434) | (0.245) | |

| logCO2 | -9.402*** | -9.402*** | -9.402*** | -8.424*** |

| (1.897) | (1.440) | (1.502) | (0.414) | |

| logNPL | -2.092*** | -2.092** | -2.092*** | -2.028*** |

| (0.712) | (0.877) | (0.785) | (0.142) | |

| logAFF | 4.547*** | 4.547*** | 4.547*** | 4.832*** |

| (0.990) | (1.359) | (1.570) | (0.338) | |

| logGDP_pc | 20.37*** | 20.37*** | 20.37*** | 18.44*** |

| (3.191) | (2.511) | (2.431) | (0.821) | |

| logEXR | 1.284*** | 1.284** | 1.284** | 1.011*** |

| (0.456) | (0.519) | (0.505) | (0.195) | |

| Infl | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | 0.0208 | 0.0274 |

| (0.0726) | (0.0867) | (0.117) | (0.0209) | |

| Constant | -161.0*** | -161.0*** | -161.0*** | -147.7*** |

| (21.07) | (18.86) | (18.64) | (6.309) | |

| Observations | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 |

| R-squared | 0.423 | 0.423 | ||

| Number of C_ID | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| (LDR) | (LDR) | Robustness (LDR) | (LDR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | PCSE 1 | PCSE 2 | FGLS Model 1 | FGLS Model 2 |

| logCRI | 0.0512** | 0.0512*** | 0.0360*** | 0.0165*** |

| (0.0232) | (0.0194) | (0.00678) | (0.00363) | |

| logCO2 | 0.191*** | 0.191*** | 0.185*** | 0.173*** |

| (0.0102) | (0.0121) | (0.00454) | (0.00575) | |

| logNPL | -0.0348** | -0.0348*** | -0.0373*** | -0.0544*** |

| (0.0137) | (0.0122) | (0.00466) | (0.00527) | |

| logAFF | 0.163*** | 0.163*** | 0.163*** | 0.141*** |

| (0.0197) | (0.0240) | (0.00590) | (0.00927) | |

| logEXR | 0.0163 | 0.0163** | 0.0118*** | 0.0112** |

| (0.0114) | (0.00768) | (0.00451) | (0.00500) | |

| Infl | 0.000423 | 0.000423 | -7.28e-05 | -0.00107** |

| (0.00195) | (0.00182) | (0.000618) | (0.000501) | |

| Constant | 3.773*** | 3.773*** | 3.862*** | 3.994*** |

| (0.125) | (0.109) | (0.0407) | (0.0361) | |

| Observations | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 |

| R-squared | 0.767 | 0.767 | ||

| Number of C_ID | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| (LDR) | (LDR) | (LDR) | |

| VARIABLES | POLS | FE | RE |

| logCRI | 0.0493** | 0.0385* | 0.0493** |

| (0.0207) | (0.0215) | (0.0207) | |

| logCO2 | 0.176*** | 0.0488 | 0.176*** |

| (0.0218) | (0.0620) | (0.0218) | |

| logNPL | -0.0587*** | -0.0712*** | -0.0587*** |

| (0.0131) | (0.0135) | (0.0131) | |

| logAFF | 0.191*** | 0.184*** | 0.191*** |

| (0.0393) | (0.0683) | (0.0393) | |

| Infl | -0.000109 | -0.000721 | -0.000109 |

| (0.00176) | (0.00176) | (0.00176) | |

| Constant | 3.774*** | 3.726*** | 3.774*** |

| 9 | (0.133) | (0.172) | (0.133) |

| Observations | 110 | 110 | 110 |

| R-squared | 0.294 | ||

| Number of C_ID | 10 | 10 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).