Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

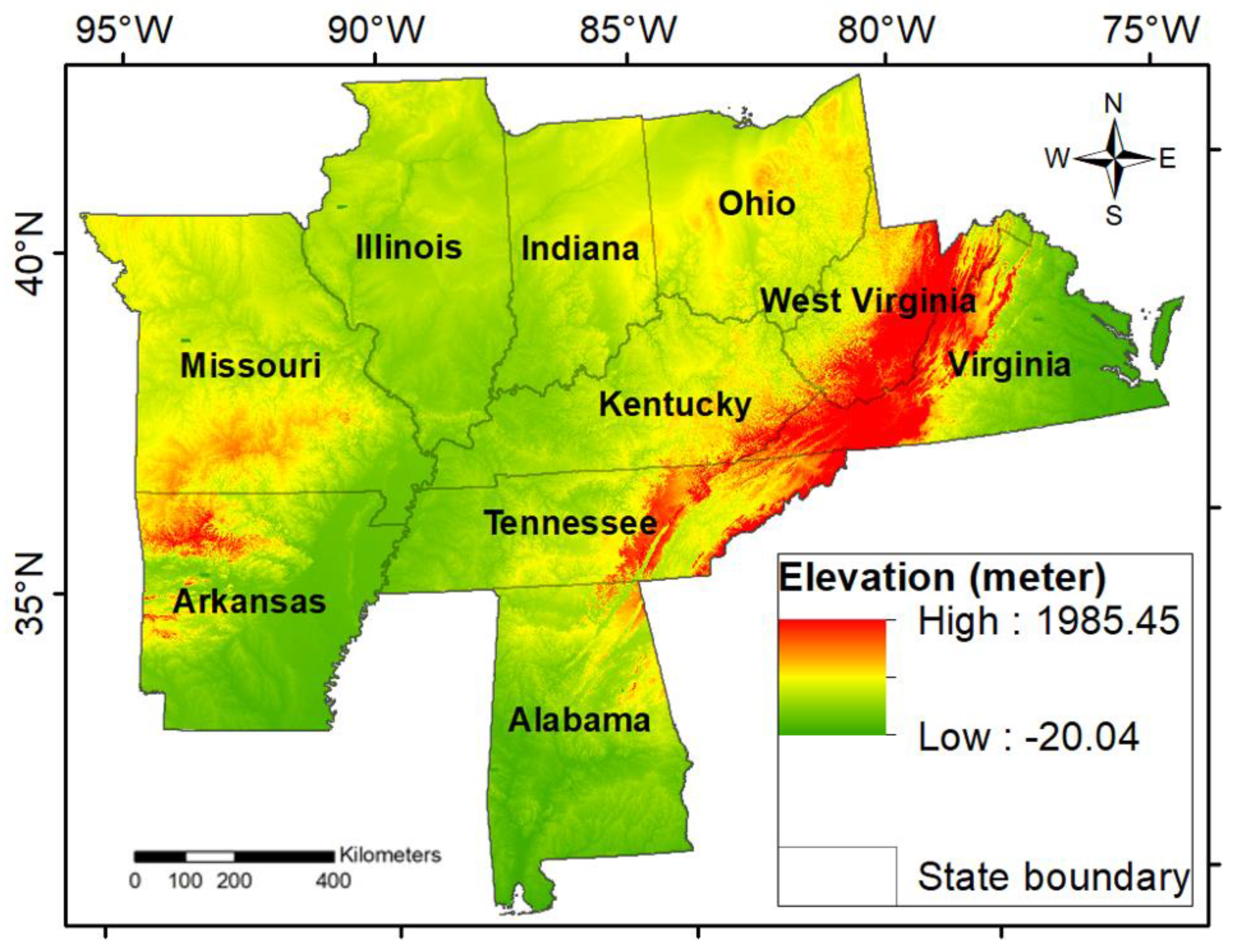

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing for Biotic and Abiotic Variables

| Biotic variables | Abiotic variables |

|---|---|

| Basal area | Climatic elements (Spring precipitation; Summer precipitation; Summer temperature; Winter temperature; Vapor Pressure) |

| Stand density | Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) |

| Stand age | Soil (Texture; Organic matter; Total available water; PH; Topsoil carbon; Subsoil carbon) |

| Terrains (Elevation; Aspect; Slope) |

2.2.1. Basal Area

2.2.2. White Oak Mortality Rate

2.2.3. Stand Density

2.2.4. Stand Age

2.2.5. Climate Variables

2.2.6. Drought Index

2.2.7. Soil Variables

2.2.8. Terrains

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

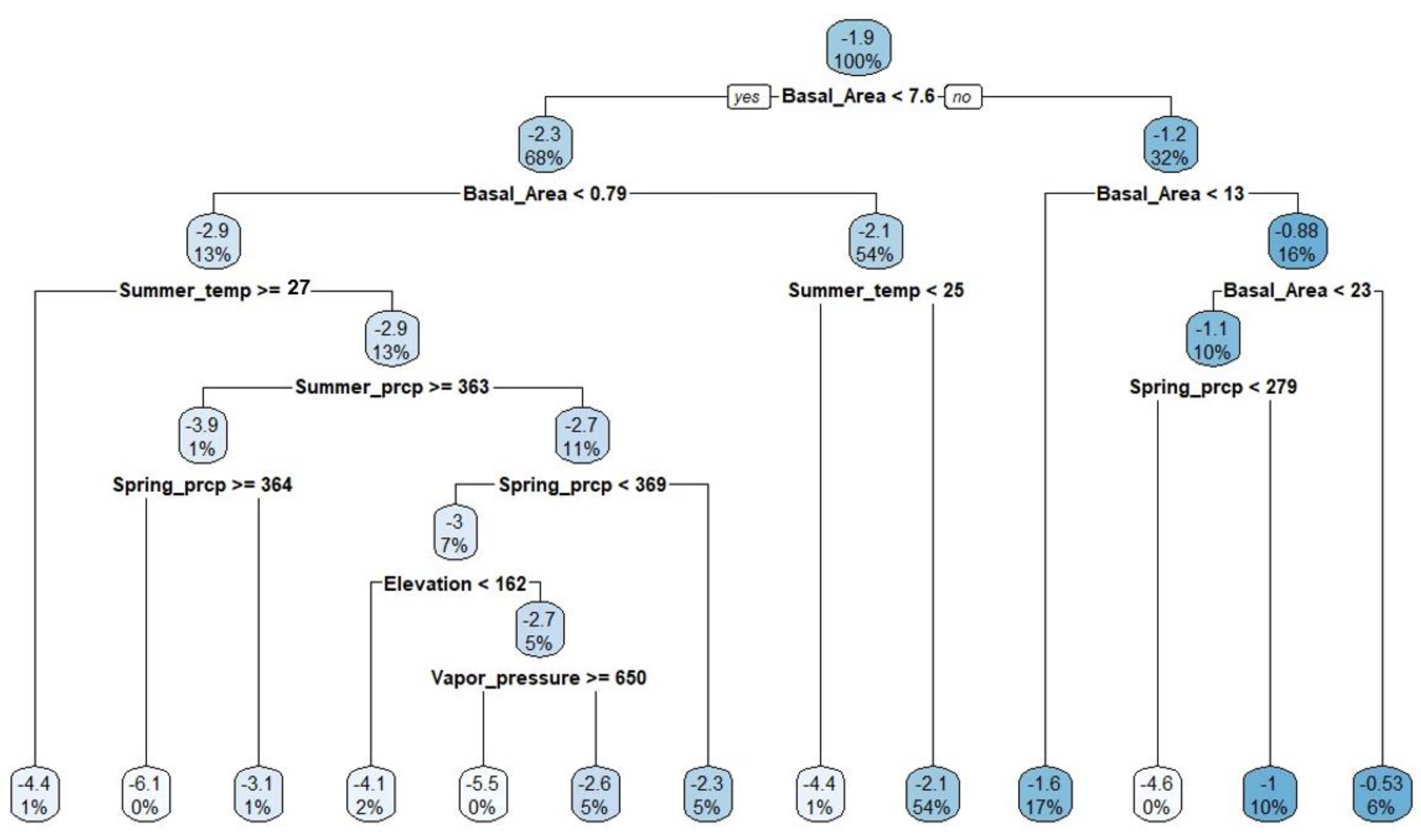

3.1. Identification of the Most Influential Variable Using the CART Model

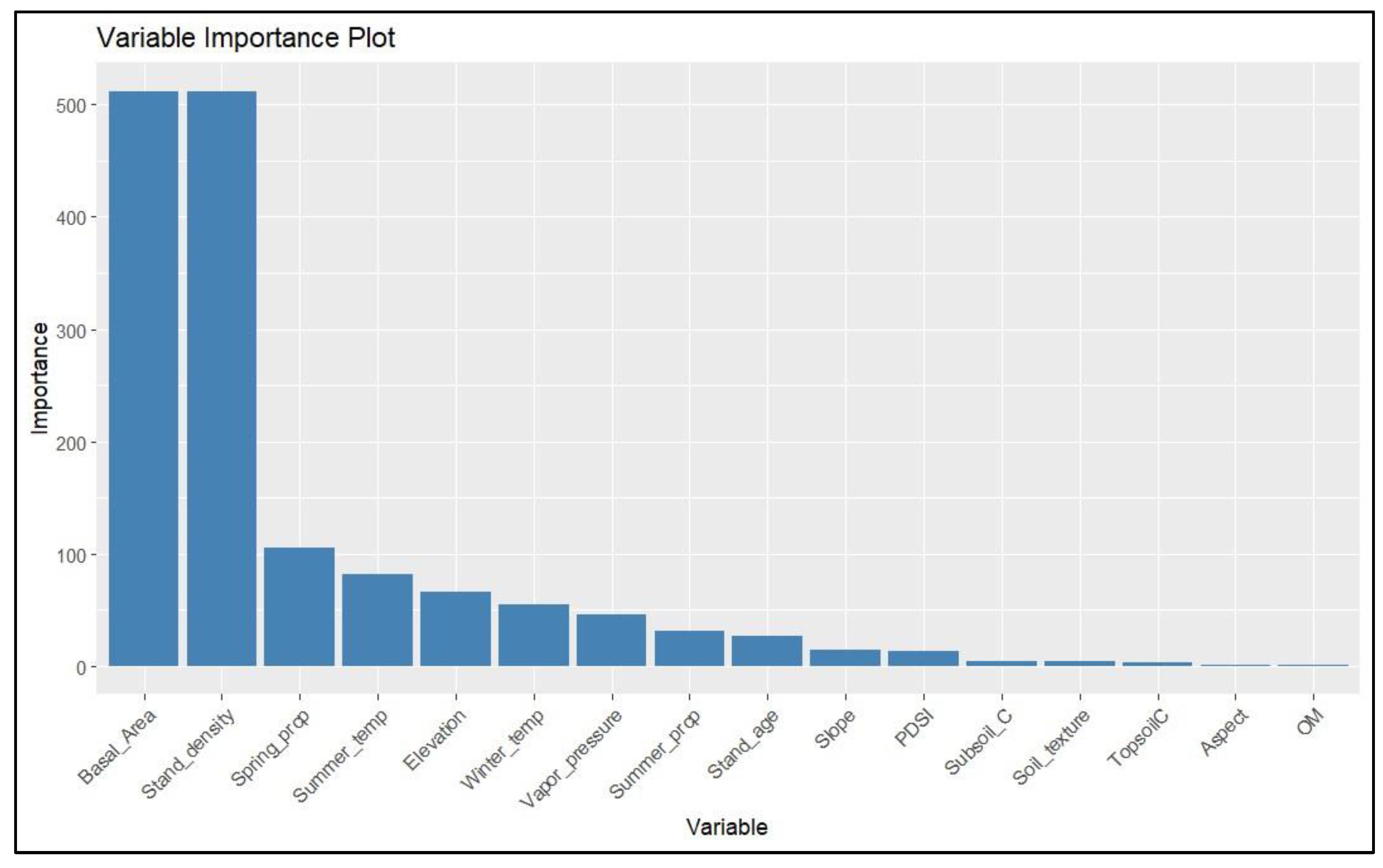

3.2. The Variable Importance of Biotic and Abiotic Influencers in Response to WOM Rate

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influential Variables in the Hierarchical Ranking and Their Ecological Significance

4.2. Management Implications of WOM Rate Under Specific Thresholds

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cavender-Bares, J. Diversification, Adaptation, and Community Assembly of the American Oaks (Quercus), a Model Clade for Integrating Ecology and Evolution. New Phytologist 2019, 221, 669–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McVay, J.D.; Hauser, D.; Hipp, A.L.; Manos, P.S. Phylogenomics Reveals a Complex Evolutionary History of Lobed-Leaf White Oaks in Western North America. Genome 2017, 60, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clotfelter, E.D.; Pedersen, A.B.; Cranford, J.A.; Ram, N.; Snajdr, E.A.; Nolan, V.; Ketterson, E.D. Acorn Mast Drives Long-Term Dynamics of Rodent and Songbird Populations. Oecologia 2007, 154, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.E.E.M.; Uen, A.M.Y.B.M.C.E.; Wihart, R.O.K.S.; Ontreras, T.H.A.C. Scatter-Hoarding Rodents in Deciduous Forests. America (NY) 2007, 88, 2529–2540. [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe, D.C.; Matthews, S.N.; Hix, D.M. Beyond Oak Regeneration: Modelling Mesophytic Sapling Density Drivers along Topographic, Edaphic, and Stand-Structural Gradients in Mature Oak-Dominated Forests of Appalachian Ohio. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2020, 50, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, C.S.M.; Arthur, M.A. Spatial Variability in Soil Nutrient Availability in an Oak-Pine Forest: Potential Effects of Tree Species. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2003, 33, 2321–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Wheeler, E.; Phillips, R.P. Root-Induced Changes in Nutrient Cycling in Forests Depend on Exudation Rates. Soil Biol Biochem 2014, 78, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudharsan, M.S.; Rajagopal, K.; Banu, N. An Insight into Fungi in Forest Ecosystems. In Plant Mycobiome: Diversity, Interactions and Uses; Springer, 2023; pp. 291–318.

- Bhat, R.A.; Dervash, M.A.; Mehmood, M.A.; Skinder, B.M.; Rashid, A.; Bhat, J.I.A.; Singh, D.V.; Lone, R. Mycorrhizae: A Sustainable Industry for Plant and Soil Environment; 2018; ISBN 9783319688671.

- Fei, S.; Steiner, K.C.; Finley, J.C.; McDill, M.E. Relationships between Biotic and Abiotic Factors and Regeneration of Chestnut Oak, White Oak, and Northern Red Oak. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE GENERAL TECHNICAL REPORT NC 2003, 223–227.

- Woodall, C.; Williams, M.S. Sampling Protocol, Estimation, and Analysis Procedures for the down Woody Materials Indicator of the FIA Program; USDA Forest Service, North Central Research Station, 2005; Vol. 256;

- Keyser, P.D.; Fearer, T.; Harper, C.A. Managing Oak Forests in the Eastern United States; CRC Press, 2016;

- Spetich, M.A. Upland Oak Ecology Symposium: History, Current Conditions, and Sustainability. Uplannd Oak Ecology Symposium: History, Current Conditions, and Sustainability 2002, 318.

- Heitzman, E. Effects of Oak Decline on Species Composition in a Northern Arkansas Forest. Southern Journal of Applied Forestry 2003, 27, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.G.; Van Lear, D.H.; Bauerle, W.L. Effects of Prescribed Fires on First-Year Establishment of White Oak (Quercus Alba L.) Seedlings in the Upper Piedmont of South Carolina, USA. For Ecol Manage 2005, 213, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedalof, Z.; Franks, J.A. Stand Structure and Composition Affect the Drought Sensitivity of Oregon White Oak (Quercus Garryana Douglas Ex Hook.) and Douglas-Fir (Pseudotsuga Menziesii (Mirb.) Franco). Forests 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouvé, R.; Bontemps, J.D.; Collet, C.; Seynave, I.; Lebourgeois, F. Growth Partitioning in Forest Stands Is Affected by Stand Density and Summer Drought in Sessile Oak and Douglas-Fir. For Ecol Manage 2014, 334, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhotka, J.M.; Loewenstein, E.F. An Individual-Tree Diameter Growth Model for Managed Uneven-Aged Oak-Shortleaf Pine Stands in the Ozark Highlands of Missouri, USA. For Ecol Manage 2011, 261, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiao, L.; Cheng, D.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; He, X.; Cao, Y.; Gao, G. Light Thinning Effectively Improves Forest Soil Water Replenishment in Water-Limited Areas: Observational Evidence from Robinia Pseudoacacia Plantations on the Loess Plateau, China. J Hydrol (Amst) 2024, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, S.; Noguchi, S.; Levia, D.F.; Araki, M.; Nitta, K.; Wada, S.; Narita, Y.; Tamura, H.; Abe, T.; Kaneko, T. Effects of Forest Thinning on Sap Flow Dynamics and Transpiration in a Japanese Cedar Forest. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, H.C.; Astrup, R.; Trowbridge, A.; Coates, K.D. Competition and Tree Crowns: A Neighborhood Analysis of Three Boreal Tree Species. For Ecol Manage 2010, 259, 1586–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anning, A.K.; Rubino, D.L.; Sutherland, E.K.; McCarthy, B.C. Dendrochronological Analysis of White Oak Growth Patterns across a Topographic Moisture Gradient in Southern Ohio. Dendrochronologia (Verona) 2013, 31, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixsen, D.P.; Hallgren, S.W.; Frazier, A.E. Stress Factors Associated with Forest Decline in Xeric Oak Forests of South-Central United States. For Ecol Manage 2015, 347, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, A.M.; Long, R.P.; Madden, L. V.; Bonello, P. Association of Phytophthora Cinnamomi with White Oak Decline in Southern Ohio. Plant Dis 2010, 94, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, D.C.; Terrells, M.A. Radial Growth Response of White Oak to Climate in Eastern North America. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2009, 39, 2180–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.J.; Kaye, M.W.; Abrams, M.D.; Hanson, P.J.; Martin, M. Tree-Ring Growth and Wood Chemistry Response to Manipulated Precipitation Variation for Two Temperate Quercus Species. Tree Ring Res 2012, 68, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, W.K.; Liknes, G.; Hansen, M.; Nimerfro, K. Incorporation of Precipitation Data into FIA Analyses: A Case Study of Factors Influencing Susceptibility to Oak Decline in Southern Missouri, USA. 2005.

- Fan, Z.; Kabrick, J.M.; Spetich, M.A.; Shifley, S.R.; Jensen, R.G. Oak Mortality Associated with Crown Dieback and Oak Borer Attack in the Ozark Highlands. For Ecol Manage 2008, 255, 2297–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bury, S.; Dyderski, M.K. No Effect of Invasive Tree Species on Aboveground Biomass Increments of Oaks and Pines in Temperate Forests. For Ecosyst 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.M.; Coggeshall, M. V.; O’Connor, P.A.; Nelson, C.D. Climate Adaptation in White Oak (Quercus Alba, L.): A Forty-Year Study of Growth and Phenology. Forests 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, S.; Gyawali, B.R.; Shrestha, T.B.; Cristan, R.; Banerjee, S. “Ban”; Antonious, G.; Poudel, H.P. Exploring Relationships among Landownership, Landscape Diversity, and Ecological Productivity in Kentucky. Land use policy 2021, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, S.; He, H.S.; Bardhan, S. Investigating the Spatial Pattern of White Oak (Quercus Alba L.) Mortality Using Ripley’s K Function Across the Ten States of the Eastern US. Forests 2024, 15, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnas, J.R.; Ayres, M.P.; Liebhold, A.M.; Evans, C. Subcontinental Impacts of an Invasive Tree Disease on Forest Structure and Dynamics. Journal of Ecology 2011, 99, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.I.; Brandeis, T.J. Estimating Maximum Stand Density for Mixed-Hardwood Forests among Various Physiographic Zones in the Eastern US. For Ecol Manage 2022, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkham, W.T.; Mahoney, P.R.; Hudak, A.T.; Domke, G.M.; Falkowski, M.J.; Woodall, C.W.; Smith, A.M.S. Applications of the United States Forest Inventory and Analysis Dataset: A Review and Future Directions. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2018, 48, 1251–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muffler, L.; Weigel, R.; Beil, I.; Leuschner, C.; Schmeddes, J.; Kreyling, J. Winter and Spring Frost Events Delay Leaf-out, Hamper Growth and Increase Mortality in European Beech Seedlings, with Weaker Effects of Subsequent Frosts. Ecol Evol 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, A. Overcoming Dormancy in Prunus Species under Conditions of Insufficient Winter Chilling in Israel. Plants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Fan, R.; Pan, X.; Chen, H.; Ma, Q. Climate Warming Advances Phenological Sequences of Aesculus Hippocastanum. Agric For Meteorol 2024, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainese, M.; Crepaz, H.; Bottarin, R.; Fontana, V.; Guariento, E.; Hilpold, A.; Obojes, N.; Paniccia, C.; Scotti, A.; Seeber, J.; et al. Global Change Experiments in Mountain Ecosystems: A Systematic Review. Ecol Monogr 2024. [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, M.; Améglio, T.; Baubet, O.; Bréda, N.; Charrier, G. Potential Processes Leading to Winter Reddening of Young Douglas-Fir Pseudotsuga Menseizii in Europe. Ann For Sci 2024, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopashree, S.; Anitha, J.; Challa, S.; Mahesh, T.R.; Venkatesan, V.K.; Guluwadi, S. Mapping of Soil Suitability for Medicinal Plants Using Machine Learning Methods. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngu, N.H.; Thanh, N.N.; Duc, T.T.; Non, D.Q.; Thuy An, N.T.; Chotpantarat, S. Active Learning-Based Random Forest Algorithm Used for Soil Texture Classification Mapping in Central Vietnam. Catena (Amst) 2024, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, S.; Bardhan, S. Examining the Relationship between Stand Density of Declining White Oaks (Quercus Alba L.) and Soil Properties across the Broader Scale of the Eastern United States 2024.

- Das, S.; Patel, P.P.; Sengupta, S. Evaluation of Different Digital Elevation Models for Analyzing Drainage Morphometric Parameters in a Mountainous Terrain: A Case Study of the Supin–Upper Tons Basin, Indian Himalayas. Springerplus 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve, M.; Aparicio, J.; Rabasa, A.; Rodriguez-Sala, J.J. Efficiency Analysis Trees: A New Methodology for Estimating Production Frontiers through Decision Trees. Expert Syst Appl 2020, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromping, U. Using R and RStudio for Data Management, Statistical Analysis and Graphics (2nd Edition). J Stat Softw 2015, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskiewicz, J.; Kenefic, L.; Weiskittel, A.; Seymour, R. Species Mixture Effects in Northern Red Oak-Eastern White Pine Stands in Maine, USA. For Ecol Manage 2013, 298, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, A.; Valentine, H.T. Models of Tree and Stand Dynamics; Springer, 2020;

- Lin, D.; Lai, J.; Yang, B.; Song, P.; Li, N.; Ren, H.; Ma, K. Forest Biomass Recovery after Different Anthropogenic Disturbances: Relative Importance of Changes in Stand Structure and Wood Density. Eur J For Res 2015, 134, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunster, K. Dictionary of Natural Resource Management; UBC press, 2011;

- Gleason, K.E.; Bradford, J.B.; Bottero, A.; D’Amato, A.W.; Fraver, S.; Palik, B.J.; Battaglia, M.A.; Iverson, L.; Kenefic, L.; Kern, C.C. Competition Amplifies Drought Stress in Forests across Broad Climatic and Compositional Gradients. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, D.I. Linking Forest Growth with Stand Structure: Tree Size Inequality, Tree Growth or Resource Partitioning and the Asymmetry of Competition. For Ecol Manage 2019, 447, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabrick, J.M.; Shifley, S.R.; Jensen, R.G.; Fan, Z.; Larsen, D.R. Factors Associated with Oak Mortality in Missouri Ozark Forests. 14th Central Hardwood Forest Conference 2004, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shifley, S.R.; Fan, Z.; Kabrick, J.M.; Jensen, R.G. Oak Mortality Risk Factors and Mortality Estimation. For Ecol Manage 2006, 229, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Bardhan, S.; Gullapalli, S.; Khadka, S. Forecasting Oak Diameter Using an LSTM Neural Network in the Missouri State of USA 2025.

- Sturrock, R.N.; Frankel, S.J.; Brown, A. V.; Hennon, P.E.; Kliejunas, J.T.; Lewis, K.J.; Worrall, J.J.; Woods, A.J. Climate Change and Forest Diseases. Plant Pathol 2011, 60, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangelo, M.; Camarero, J.J.; Borghetti, M.; Gentilesca, T.; Oliva, J.; Redondo, M.A.; Ripullone, F. Drought and Phytophthora Are Associated with the Decline of Oak Species in Southern Italy. Front Plant Sci 2018, 871, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwecki, R.; Ufnalski, K. Review of Oak Stand Decline with Special Reference to the Role of Drought in Poland. European Journal of Forest Pathology 1998, 28, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taccoen, A.; Piedallu, C.; Seynave, I.; Gégout-Petit, A.; Gégout, J.C. Climate Change-Induced Background Tree Mortality Is Exacerbated towards the Warm Limits of the Species Ranges. Ann For Sci 2022, 79, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, H.; Rydin, H.; Hylander, K.; Nilsson, M.B.; Lindborg, R.; Norberg, J. Towards a Trait-Based Ecology of Wetland Vegetation. Journal of Ecology 2017, 105, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifley, S.R.; Fan, Z.; Kabrick, J.M.; Jensen, R.G. Oak Mortality Risk Factors and Mortality Estimation. For Ecol Manage 2006, 229, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlali, R.; Taoussi, M.; Laasli, S.E.; Gachara, G.; Ezzouggari, R.; Belabess, Z.; Aberkani, K.; Assouguem, A.; Meddich, A.; El Jarroudi, M.; et al. Effects of Climate Change on Plant Pathogens and Host-Pathogen Interactions. Crop and Environment 2024, 3, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichs, D.A.; Trouet, V.; Büntgen, U.; Frank, D.C.; Esper, J.; Neuwirth, B.; Löffler, J. Species-Specific Climate Sensitivity of Tree Growth in Central-West Germany. Trees 2009, 23, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, R.W.; Dyer, J.M.; Pederson, N. Multiple Interacting Ecosystem Drivers: Toward an Encompassing Hypothesis of Oak Forest Dynamics across Eastern North America. Ecography 2011, 34, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.S. The Mortality of Midwestern Overstory Oaks as a Bioindicator of Environmental Stress. Ecological Applications 1999, 9, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixsen, D.P.; Hallgren, S.W.; Frazier, A.E. Stress Factors Associated with Forest Decline in Xeric Oak Forests of South-Central United States. For Ecol Manage 2015, 347, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilo-Alves, C.S.P.; Vaz, M.; Da Clara, M.I.E.; Ribeiro, N.M.D.A. Chronic Cork Oak Decline and Water Status: New Insights. New For (Dordr) 2017, 48, 753–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.-B.; Chu, L.-Y.; Jaleel, C.A.; Zhao, C.-X. Water-Deficit Stress-Induced Anatomical Changes in Higher Plants. C R Biol 2008, 331, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Sunita, K.; Giri, S.N.; Reddy, K.R. Influence of High Temperature and Breeding for Heat Tolerance in Cotton: A Review. Advances in agronomy 2007, 93, 313–385. [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlin, B.C.; Zavaleta, E.S. Predicting Species Responses to Climate Change: Demography and Climate Microrefugia in California Valley Oak (Quercus Lobata). Glob Chang Biol 2012, 18, 2301–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.M.; Jantz, P.; Goetz, S.J. Vulnerability of Eastern US Tree Species to Climate Change. Glob Chang Biol 2017, 23, 3302–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, D.C.; Terrell, M.A. Comparison of Growth-Climate Relationships between Northern Red Oak and White Oak across Eastern North America. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2011, 41, 1936–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.E.; McGregor, G.R.; Enfield, K.B. Humidity: A Review and Primer on Atmospheric Moisture and Human Health. Environ Res 2016, 144, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meineke, E.K.; Frank, S.D. Water Availability Drives Urban Tree Growth Responses to Herbivory and Warming. Journal of Applied Ecology 2018, 55, 1701–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.T.; Kirchner, J.W.; Braun, S.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Goldsmith, G.R. Seasonal Origins of Soil Water Used by Trees. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2019, 23, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, C.J.; McCarthy, B.C. Relationship of Understory Diversity to Soil Nitrogen, Topographic Variation, and Stand Age in an Eastern Oak Forest, USA. For Ecol Manage 2005, 217, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belote, R.T.; Jones, R.H.; Wieboldt, T.F. Compositional Stability and Diversity of Vascular Plant Communities Following Logging Disturbance in Appalachian Forests. Ecological Applications 2012, 22, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begna, T.; Daniela Naomi, O.-F.; Arturo Amed, L.-M.; Carolina, J.-H.; Victor Salvador, C.-G.; Andres, A.-R.; Hernandez Alberto, R.M. IMPACT OF DROUGHT STRESS ON CROP PRODUCTION AND ITS MANAGEMENT OPTIONS. International Journal of Research Studies in Agricultural Sciences 2022, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.S.; Shifley, S.R.; Rogers, R.; Dey, D.C.; Kabrick, J.M. The Ecology and Silviculture of Oaks; Cabi, 2019;

- Haavik, L.J.; Billings, S.A.; Guldin, J.M.; Stephen, F.M. Emergent Insects, Pathogens and Drought Shape Changing Patterns in Oak Decline in North America and Europe. For Ecol Manage 2015, 354, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, P.J.; Harrington, C.A.; Devine, W.D. Growth of Oregon White Oak (Quercus Garryana). Northwest Science 2011, 85, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.; Lead, M.H.; Swanston, C.; Lead, N.; Janowiak, M.; Hub, N.F.S.; Steele, R.F.; Hub, M.; Cole, A.; Sharon Hestvik, R.M.A.; et al. USDA Midwest and Northern Forests Regional Climate Hub: Assessment of Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies. US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA 2015, 55. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc, D.C.; Terrells, M.A. Radial Growth Response of White Oak to Climate in Eastern North America. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2009, 39, 2180–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Puettmann, K.; Wilson, E.; Messier, C.; Kames, S.; Dhar, A. Can Boreal and Temperate Forest Management Be Adapted to the Uncertainties of 21st Century Climate Change? CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 2014, 33, 251–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefpour, R.; Temperli, C.; Jacobsen, J.B.; Thorsen, B.J.; Meilby, H.; Lexer, M.J.; Lindner, M.; Bugmann, H.; Borges, J.G.; Palma, J.H.N.; et al. A Framework for Modeling Adaptive Forest Management and Decision Making under Climate Change. Ecology and Society 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.L.; Schweitzer, C.J. Stand Dynamics of an Oak Woodland Forest and Effects of a Restoration Treatment on Forest Health. For Ecol Manage 2016, 381, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, K.T. Forest Soils: Properties and Management; Springer International Publishing, 2013; Vol. 9783319025414; ISBN 9783319025414.

- Arthur, M.A.; Alexander, H.D.; Dey, D.C.; Schweitzer, C.J.; Loftis, D.L. Refining the Oak-Fire Hypothesis for Management of Oak-Dominated Forests of the Eastern United States. J For 2012, 110, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, L.R.; Hutchinson, T.F.; Prasad, A.M.; Peters, M.P. Thinning, Fire, and Oak Regeneration across a Heterogeneous Landscape in the Eastern U.S.: 7-Year Results. For Ecol Manage 2008, 255, 3035–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, P.R.; Parker, G.R.; Ward, J.S.; Michler, C.H. Spatial Dispersion of Trees in an Old-Growth Temperate Hardwood Forest over 60 Years of Succession. For Ecol Manage 2003, 180, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, K.M.; O’Hara, K.L. Silvicultural Strategies in Forest Ecosystems Affected by Introduced Pests. In Proceedings of the Forest Ecology and Management; April 18 2005; Vol. 209; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, A.M.; Iverson, L.R.; Liaw, A. Newer Classification and Regression Tree Techniques: Bagging and Random Forests for Ecological Prediction. Ecosystems 2006, 9, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Texture | SOM (%) | TAW (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay (C) | Loam (L) | Sandy Loam (SL) | No (0) | Very Low (0 - 20) |

| Clay Loam (CL) | Loamy Fine Sand (LFS) | Silt (SI) | Low (0.01) | Low (21 - 40) |

| Coarse Sand (COS) | Loamy Sand (LS) | Silt Loam (SIL) | Medium (0.02 -0.03) | Medium (41 - 60) |

| Fine Sand (FS) | Sand (S) | Silty Clay (SIC) | High (0.04 -0.1) | High (61 - 80) |

| Fine Sandy Loam (FSL) | Sandy Clay (SC) | Silty Clay Loam (SICL) | Very High (1.1 -3.7) | Very High (81 - 100) |

| Inland Water (WR) | Sandy Clay Loam (SCL) | Very Fine Sandy Loam (VFSL) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).