1. Introduction

Rescue teams are composed of professionals trained to respond to emergencies and relief situations. These teams include police groups (involved in security management in crisis situations and assist in rescue and evacuation tasks), soldiers (combine their military skills with specialized life-saving techniques in emergency situations, providing assistance in search, rescue and evacuation operations in high-risk or conflict environments), firefighters (responsible for extinguishing fires, rescuing people in dangerous situations and handling hazardous materials), paramedics (provide emergency medical care and stabilize patients in emergency situations, and provide emergency medical care and stabilize patients in dangerous situations), rescue people in dangerous situations and handle hazardous materials), paramedics (provide emergency medical care and stabilize patients before transporting them to health facilities) and search and rescue personnel (specialize in locating and rescuing trapped or lost people, often in difficult terrain such as mountains, forests or collapsed areas) [

1,

2].

These professionals face various incidents, each with its own challenges and risks. In the case of natural disasters, such as earthquakes, they must deal with building collapses, which trap people and cut off basic services. Floods require the rescue of people trapped in flooded homes and the evacuation of at-risk areas. On the other hand, hurricanes and storms can cause extensive damage to infrastructure, requiring the search for survivors in debris. Forest fires involve fire control, extinguishing, and rescue of people and animals.

Major accidents are another frequent type of incident. Traffic accidents, for example, may involve multiple collisions and the rescue of victims trapped in vehicles, in addition to providing first aid at the scene. In industrial accidents, on the other hand, rescue teams must handle hazardous materials and perform rescues in high-hazard environments, such as factories and chemical plants. Likewise, air and rail accidents require survivors to search for, rescue, and manage scenes with multiple victims.

In addition, rescue teams respond to medical emergencies, such as heart attacks, where rapid response for patient stabilization and transport is crucial. Similarly, drug overdoses demand urgent treatment and transport to medical facilities, while serious injuries require immediate patient care and stabilization.

Due to the nature of their work, rescue professionals are constantly exposed to high-stress and traumatic situations. The frequency and severity of incidents, hazardous working conditions and the emotional impact of rescuing or failing to rescue victims contribute to this exposure. In addition, long shift workloads and lack of adequate rest and recovery increase fatigue and stress [

3,

4].

The analysis of mental health support mechanisms, such as debriefing, for rescue teams is intrinsically linked to environmental factors and public health outcomes. Rescue teams often operate in high-stress environments characterized by natural disasters, public health emergencies, and other crises. The psychological toll of these situations can lead to significant mental health challenges, including anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which not only affect the responders but also influence their effectiveness in providing care to affected populations [

5,

6].

The aforementioned high exposure to traumatic and stressful events can have various consequences for these professionals. Two of the most common problems are post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and burnout [

7].

PTSD is a mental disorder that can develop after a person has been exposed to a traumatic event [

1]. In rescue teams, PTSD symptoms are particularly common due to the nature of their work [

8,

9]. These symptoms may include reliving the traumatic event through flashbacks, nightmares, or intrusive thoughts about the event [

10,

11,

12]. In addition, people may experience avoidance, i.e., they avoid places, people, or activities that remind them of the traumatic event. Hyperarousal is another symptom, which manifests with insomnia, irritability, difficulty concentrating, and an exaggerated startle response [

12]. Negative changes in thinking and mood are also common, including persistent negative thoughts about oneself or the world, feelings of guilt or shame, and a loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities [

10,

11,

12].

The prevalence of PTSD among rescue teams internationally varies between 10% and 35% [

2], with some studies showing it to be significantly higher compared to the general population [

13,

14]. For example, some research has revealed that 45% of firefighters have experienced four or more potentially traumatic events [

15] and about 32% of them have clinically significant PTSD symptoms [

16]. In 2022, approximately 72,965 cases of PTSD were reported in Spain [

17].

Burnout is another prevalent mental health problem among rescue workers [

18]. It is characterized by extreme emotional and physical fatigue, depersonalization, and diminished personal accomplishment [

19,

20]. Professionals suffering from burnout may feel physically and emotionally exhausted and may develop a cynical or distant attitude toward their work and the people they serve. In addition, they may experience a reduction in their work performance, with decreased efficiency and productivity and an increased propensity to make mistakes [

19].

These mental health problems have a significant impact on the individual well-being of rescue professionals and their professional performance [

21]. PTSD can lead to long-term health problems, difficulties in personal relationships, and an inability to perform everyday tasks [

22]. Burnout can result in a decrease in the quality of service provided, increased absenteeism, and increased staff turnover. Taken together, these problems affect the health and well-being of professionals and can have negative consequences for rescue organizations and the community at large, which depends on these essential services.

For this reason, it seems crucial that rescue teams receive adequate psychological support to help them process traumatic experiences, reduce the effects of stress and maintain their mental health and general well-being. One of the most commonly employed therapeutic approaches in this regard is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which has proven to be effective in the treatment of PTSD and other anxiety disorders [

23,

24]. CBT focuses on changing negative thought patterns and developing effective coping strategies. In addition, resilience programs and stress management training have also been implemented to strengthen the ability of rescue professionals to manage stress and reduce the risk of burnout [

25].

Despite this variety of alternatives, techniques such as debriefing have been created to address these issues in rescue team members.

Debriefing as a Psychological Intervention in Rescue Teams

Debriefing is a structured group technique based on the Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) model [

26,

27], which was initially created as a short-term, group-format, preventive mental health intervention for law enforcement and emergency services personnel who had experienced traumatic situations. Since its origin, the debriefing model has been adapted and modified to apply to various clinical groups and crisis contexts, leading to changes in its structure and procedures [

28]. It is applied to help process events and lived experiences after a traumatic event [

28]. In mountain rescue teams, these experiences often have a high emotional impact due to the serious mishaps that occur during rescue operations and could have special connotations [

29].

This group intervention is designed to reduce emotional impact and burnout [

30] and prevent future mental health problems, such as PTSD. The main goals of debriefing are to provide a safe space for emotional expression, normalize reactions to trauma, and foster mutual support among participants.

The debriefing process consists of several phases, each with a specific purpose [

26]. The session begins with an introduction, where the purpose of the meeting is explained, and the rules of confidentiality and respect are established. Next, the facts of the event are reviewed, allowing participants to describe the incident from their perspective and focus on objective details. Subsequently, participants’ reactions and thoughts are discussed, allowing them to express their emotions about the event. Next, symptoms experienced since the incident, both physical and emotional, are addressed. In the teaching phase, information about common reactions to trauma is provided, and coping strategies are offered. Finally, in the re-entry phase, the session concludes with a summary and information about additional resources, and follow-up is provided [

26].

There are several types of debriefing tailored to the needs of the group and the nature of the traumatic event. One of the best-known is Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD), developed by Jeffrey T. Mitchell [

27], which focuses on emergency teams and other high-risk groups. This model follows a seven-phase process: introduction, review of facts, discussion of thoughts and reactions, identification of symptoms, teaching, and re-entry [

26]. Another type is psychological debriefing, which is more widespread and is used in a variety of clinical settings, adapting to different groups affected by trauma [

31]. There is also informational debriefing, which is less structured and can occur spontaneously among colleagues or friends after a traumatic event [

32].

Jeffrey T. Mitchell’s CISD model [

27] is one of the most widely applied theories. Developed for emergency teams and other groups that regularly face traumatic situations, CISD’s main objectives are to mitigate the emotional impact, help participants process and manage immediate emotional reactions, normalize reactions by providing information that helps them understand that their responses are normal given the circumstances, and foster group support by creating an environment where participants can share experiences and offer mutual support.

On the other hand, social support theory stresses the importance of support networks in the management of stress and trauma. According to this theory, social support can provide emotional resources, facilitate emotional expression safely and constructively, and improve people’s coping capacity [

33,

34]. In the context of debriefing, this theory highlights how a supportive environment, whether among colleagues, friends or family, can offer comfort and reduce feelings of isolation, thus contributing to the well-being and recovery of people affected by trauma.

Thus, intuitively, debriefing could act as a preventive measure against possible future mental disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, and could contribute to individual and group health, thus improving the performance of professionals and rescue teams [

35].

Numerous studies have evaluated the efficacy of debriefing in mental health, with most studies focusing on people who have experienced a traumatic event. The findings have been mixed, and the studies appear to have serious methodological shortcomings [

36,

37]. However, rescue teams frequently exposed to traumatic events have special characteristics that differ from the general population, including extensive training and specialization in emergency situations, so they may respond differently to debriefing strategies. Some studies suggest that debriefing can help reduce post-traumatic stress symptoms and improve emotional well-being in this population [

35]. For example, it has been found to provide a safe space for professionals to express their emotions and process their experiences, which may reduce the immediate emotional impact and prevent long-term mental health problems [

35]. However, in that study, conclusions are drawn, again from civilian victims and not rescue groups, since, as the authors conclude, only 1 of 15 studies included in their review was conducted on emergency personnel [

35]. Therefore, knowing the effect of debriefing on emergency personnel or rescue groups may help propose psychological support programs to prevent or treat PTSD or burnout in this specific population.

On the other hand, other research has questioned these benefits, indicating that debriefing may not be as effective as initially thought. Some studies even suggest that it may have negative effects, such as retraumatizing participants by reliving the traumatic event [

38]. Additionally, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have pointed out the low quality of many debriefing studies, highlighting issues such as inadequate control groups, small sample sizes, and flawed study designs. These methodological limitations complicate drawing definitive conclusions about the efficacy of debriefing in the general population [

36,

38], and given the special characteristics of emergency and rescue professionals, warrant individualized study. These controversies highlight the importance of conducting a systematic, rigorous, and updated review of the existing literature to clarify the effectiveness of debriefing in this population, paying special attention to psychological problems that are highly prevalent among these professionals [

7]and that have not been previously analyzed about the effectiveness of debriefing. A comprehensive evaluation will identify the strengths and weaknesses of this intervention, as well as the conditions under which it may be most effective. At the same time, it is essential to consider other interventions and strategies that have proven effective in the psychological support of rescue teams, such as those mentioned above.

Therefore, the present research focuses on debriefing as an intervention aimed at mitigating mental health problems in rescue teams. The central question guiding this review is: Is debriefing effective for treating post-traumatic stress disorder or burnout in rescue teams compared to other interventions? In this regard, the main objective of this review is to evaluate the effectiveness of debriefing in preventing and treating these specific problems through a systematic review of the existing scientific literature.

2. Materials and Methods

This work is developed within the Debriefing and Psychological Support to Rescue Teams working group of the Mountain Chair of the University of Zaragoza. The systematic review will follow the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [

39] and the Cochrane methodology [

40], using the PICOS strategy for developing the research question [

41]. Additionally, the review has been registered at PROSPERO (Prospero num. CRD42024618564).

The PRISMA methodology establishes guidelines for the complete elaboration of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Its objective is to optimize the quality and transparency of the information presentation, ensuring that all the essential elements for assessing the validity and applicability of the results are included. PRISMA facilitates a clear and detailed structure that guides from formulating the formulation of the research question to presenting the presentation of the findings, thus promoting reproducibility and comparability between studies [

39].

On the other hand, the Cochrane methodology focuses on conducting high-quality systematic reviews in healthcare. The Cochrane Collaboration provides rigorous standards for designing, conducting and interpreting evidence-based systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Its approach is based on thorough and critical identification of the relevant literature, meticulous assessment of the risk of bias in the included studies, and statistical synthesis of the results to provide clear and robust conclusions about the effectiveness of the evaluated interventions [

40].

Both methodologies, PRISMA and Cochrane, complement each other to ensure that systematic reviews are conducted comprehensively and methodologically soundly, thus ensuring that the results are reliable and useful for clinical and health policy decision-making.

Finally, the PICOS strategy [(P: Population or problem of interest; I: Intervention; C: Comparison; O: Outcome; S (Study)], is a tool used in research to formulate specific clinical questions and structure the search for relevant evidence.

2.1. Search Strategy and Databases

The search strategy, summarized in

Table 1, was designed to identify relevant studies in the PubMed and PsycINFO databases. It used a combination of MeSH terms and keywords related to “debriefing,” “psychological support,” “rescue teams,” or similar terms, as well as specific mental health terms such as “PTSD” and “burnout.”

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

For articles to be included, they had to meet the following inclusion criteria based on the PICOS method:

- -

Population (P): members or participants in organized rescue groups.

- -

Intervention (I): debriefing

- -

Comparator (C): control comparisons, placebo or other conservative non-pharmacological interventions.

- -

Outcome variables (O): Post-traumatic stress disorder and burnout.

- -

Type of study (S): clinical trials.

- -

Articles published in any year.

Quantitative studies investigating the effect of debriefing on rescue teams were included. The articles should be published in English or Spanish and accessible through indexed scientific journals. When reported in studies whose main variables were PTSD or burnout, results of other variables associated with stress or psychological factors were also included.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

We excluded studies that did not explicitly focus on debriefing in rescue teams, along with those that addressed disorders other than post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and burnout. Qualitative and observational studies were also excluded, in addition to studies published in languages other than English or Spanish and in formats other than peer-reviewed scientific journals.

2.4. Selection Process

First, a review protocol was established to create a structured plan for the entire process, aiming to avoid potential biases and ensure the review’s transparency. In this step, the necessity of the study was clarified, and the review question was formulated. The search strategy was crafted, detailing the eligibility criteria, the data extraction and synthesis method, and the planning for disseminating the results.

Once the search had been carried out according to the previously defined strategy, duplicate articles were eliminated using the Mendeley bibliographic manager. The titles and abstracts of all the records obtained were read. A checklist was created in Microsoft Excel to evaluate whether each article met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and was relevant to our purpose.

Subsequently, the full articles preselected during the abstract review phase were read and analyzed. Using the checklist previously created, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were reapplied, thus selecting the articles to be included in the systematic review.

In summary, the process included the following steps:

Initial search: an exhaustive search was conducted in the aforementioned databases using the defined terms and strategies.

Elimination of duplicates: The Mendeley bibliographic manager was used to manage and eliminate duplicates efficiently.

Title/abstract review: The titles and abstracts of retrieved articles were examined to identify potentially relevant works.

Full-text reading: The articles selected in the previous stage were read completely to determine their final inclusion in the review.

Article selection: Studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were chosen for the systematic review.

Data extraction: Relevant data, including the characteristics of the studied population, the type of intervention and comparison, main results, and pertinent conclusions, were extracted from each selected study.

2.5. Methodological Quality of the Studies

The methodological quality of the studies has been assessed using the PEDro scale, developed by Verhagen and colleagues through a Delphi study [

42]. This scale comprises 11 criteria for evaluating the quality of clinical trials in systematic reviews. The 11 criteria are as follows:

The selection criteria were specified.

Participants were randomly assigned to groups.

The assignment was concealed.

The groups were similar at baseline.

All subjects were blinded.

All therapists were blinded.

All evaluators were blinded.

Measures of at least one key outcome were obtained from over 85% of the subjects initially assigned to the groups.

Results were provided for all subjects who received treatment or were assigned to the control group. When this was not possible, data for at least one key outcome were analyzed on an “intention-to-treat” basis.

Statistical comparisons between groups were reported for at least one key outcome.

The study provides measures of point and variability for at least one key outcome.

Despite being composed of 11 items, the total score is out of 10 because the first criterion is not included in the overall total. The PEDro scale indicates that a higher score reflects better methodological quality. Therefore, a score of 7 or higher is considered to indicate “high” quality, a score between 5 and 6 is deemed “acceptable”, and a score of 4 or lower is classified as “poor”.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Review Process

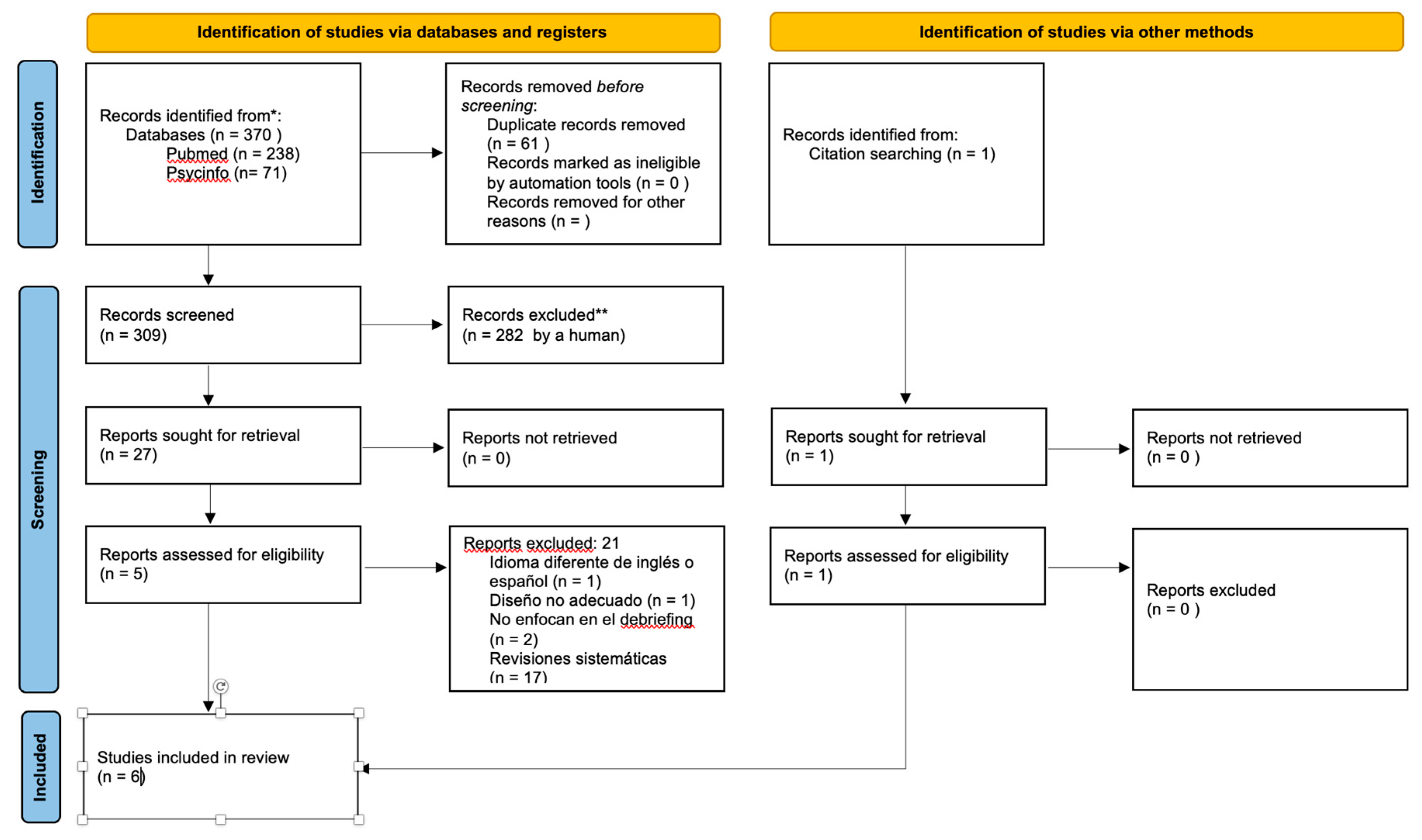

The initial literature search identified 370 studies, to which we added 1 study obtained through cross-referencing. Twenty-seven full articles were reviewed in detail, of which 6 met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the systematic review.

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram and why articles were excluded from the final selection of studies.

3.2. Results of the Methodological Quality Evaluation

Regarding assessing the methodological quality of the included articles using the PEDro scale, it was noted that the scores ranged from 4 to 7 points. Of the six studies evaluated, one was rated as high quality, three were classified as acceptable, and two demonstrated poor methodological quality (

Table 2).

3.3. Main Results

The selected studies investigated the effects of debriefing, specifically through the structured CISD process in emergency teams. However, the study variables and populations are heterogeneous. In particular, three studies involved soldiers as participants, one involved Chinese military rescuers, one involved emergency personnel, and the last involved paramedics and emergency medical technicians (EMT). These investigations were conducted across several countries, including the United States, Australia, England, China, and Canada. All studies examined the impact of debriefing on PTSD and, in some cases, also considered other variables such as psychological stress, quality of life, and alcohol consumption. No specific studies were found evaluating the effectiveness of debriefing in mountain rescue teams.

Adler et al. (2008)conducted a cluster randomised trial with 952 peacekeepers, comparing Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) with a stress management class (SMC) and a survey-only (SO) condition. The results indicated that CISD did not accelerate recovery more than the other two conditions. However, among soldiers with greater exposure to mission stressors, CISD showed a slight reduction in reports of PTSD and aggression compared to SMC, as well as an increase in perceived organisational support compared to SO, although an increase in alcohol-related problems was also observed relative to both groups.

Tuckey and Scott (2014) conducted a randomized clinical trial with 67 firefighters who had experienced a potentially traumatic event. Although CISD showed benefits in terms of lower alcohol consumption and improved quality of life compared with stress management education, no significant evidence was found that CISD was more effective in preventing PTSD or reducing psychological distress.

In the British Columbia Ambulance Service, a randomized controlled trial involving paramedics and medical technicians (EMTs) assessed three critical incident stress intervention strategies [

45]. Over 26 months, 50 critical incident stress-related calls were documented, but only 18 participants enrolled, of whom six did not complete the forms. Although several outcomes were evaluated over a six-month timeframe, there was no consistent correlation between incident severity and stress scores, no clear pattern of stress reduction over time, and none received formal debriefing. Due to low participation, the study could not adequately compare the three intervention levels, which was a key objective. However, the study suggests that while CISD is necessary, in the context of ambulance services, it likely does not require significant additional resource allocation.

Adler et al. (2011)also compared various early interventions involving 2,297 U.S. soldiers following their deployment in Iraq. In this context, they are not specifically rescue personnel, although their missions typically encompass these responsibilities, and in any case, they are exposed to high-stress situations. The study found that soldiers with significant combat exposure who underwent the Battlemind debriefing reported fewer symptoms of PTSD, depression, and sleep disturbances compared to those who received only stress education. Participants in smaller Battlemind groups also exhibited better outcomes for PTSD and sleep, while larger groups demonstrated fewer symptoms of depression and lower levels of stigma.

Deahl et al. (2000) examined the psychiatric morbidity of 106 British soldiers returning from UN peacekeeping missions in the former Republic of Yugoslavia. All 106 soldiers received an operational stress (OS) training package before deployment. Immediately after their return from Bosnia, they participated in a formal psychological debriefing session following the Mitchell and Dyregrov method. Scores on the CAGE questionnaire for detecting drinking behaviours decreased significantly in the group that attended the briefing at the end of the follow-up period.

Finally, Wu et al. (2012)compared the efficacy of a new psychological intervention model (“512 PIM”) with traditional debriefing in 2,368 Chinese military rescuers. The results indicated that “512 PIM” was more effective in reducing symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression than debriefing and the control group, demonstrating significant improvements in symptoms of re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal.

Taken together, these studies present mixed results on the effectiveness of CISD and other interventions, with some benefits noted in reducing PTSD symptoms and related issues but no clear consensus on their superiority compared to alternative strategies or the absence of intervention.

Table 3. presents each study’s main characteristics and a summary of their main results.

4. Discussion

The results of the studies reviewed provide a diverse and nuanced perspective on the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions, including critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) and other techniques, in alleviating symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychological distress, and other issues related to trauma.

Although some interventions, such as CISD, show positive effects in specific areas like organisational support and quality of life, their effectiveness in preventing or alleviating PTSD symptoms or psychological distress is limited and varies by context and population. The results underscore the need for more personalised approaches, such as Battlemind training and 512 PIM, that are suited to the unique needs of individuals with varying levels of trauma exposure.

CISD, as an intervention aimed at addressing the emotional and psychological effects following a traumatic event, may have been more applicable to those who experienced a higher level of stress. The intervention provided them with a structured environment to process the trauma, which seems to have helped in reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress and aggression [

43].

Furthermore, the CISD also indicated that participants perceived greater organizational support than the SO condition. This could stem from the intervention’s group structure, which promotes teamwork and a sense of community, potentially enabling these soldiers to feel more connected and supported by their peers and the organisation. This reinforces the findings of previous meta-analyses that identify social support post-incident as a critical factor in reducing the risk of developing PTSD [

49]. Nevertheless, an increase in alcohol-related problems was noted in the group with greater organisational support, contrasting with the results of Tuckey and Scott’s (2014) study, which demonstrated improved quality of life and reduced alcohol consumption among participants in the CISD group. A decrease in drinking behaviour was also observed in the study by Deahl et al. (2000), which examined the psychiatric morbidity of 106 British soldiers returning from UN peacekeeping missions in the former Republic of Yugoslavia. Scores on the CAGE questionnaire used to detect drinking behaviours decreased significantly in the group receiving psychological debriefing at the end of the follow-up period. Variations in the characteristics of the populations studied, their contexts, differing levels of stress exposure, and organisational culture may account for these discrepancies.

Tuckey and Scott’s (2014) clinical trial was conducted with firefighters who had experienced a traumatic event and also used CISD as an intervention. Although the results showed improved quality of life and decreased alcohol consumption among participants in the CISD group, no strong evidence was found to indicate that this intervention or the others implemented were effective in preventing PTSD or reducing psychological distress. This study underscores the complexity of evaluating the impact of psychosocial interventions and suggests that the positive effects of CISD may be limited and specific to certain outcomes rather than encompassing all aspects of mental health. While CISD appears to have improved some elements of general well-being and reduced risk behaviours such as alcohol use, it was not robust enough to have a profound impact on preventing PTSD or alleviating psychological distress. This implies that, although it may be useful as part of a broader emotional support approach, it may not be suitable as the sole intervention for severe psychological trauma.

On the other hand, studies such as that by Adler et al. (2011) on Battlemind debriefing and Battlemind training in U.S. soldiers provide a more encouraging perspective. Results indicated that those with high levels of combat exposure who received Battlemind debriefing reported fewer post-traumatic stress symptoms, depressive symptoms, and sleep problems than those who received only stress education. The same effects were observed in participants of small-group Battlemind training with high levels of combat exposure. The results demonstrate that brief early interventions can be effective for at-risk occupational groups, emphasising the importance of interventions that promote group cohesion and address participants’ specific experiences, such as combat exposure in this instance.

Finally, the study by Wu et al. (2012), which evaluated a new psychological intervention (512 PIM) in Chinese military rescuers, found that this intervention was more effective than traditional debriefing in reducing symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression.

The main distinction between the “512 PIM” and the debriefing lies in including a section dedicated to cohesion training. The “512 PIM” was initially designed for use in the Wenchuan seismic field, considering the practical principles and realities of the Chinese military organisation. Due to several key factors, the “512 PIM” intervention likely proved more beneficial than traditional debriefing. First, the “512 PIM” includes a cohesion training section that fosters social support, mutual trust, and a sense of belonging among participants. This group cohesion may have played a significant role in reducing symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression, as social support is a protective factor in trauma situations [

33,

34].

Moreover, the “512 PIM” was specifically designed by considering the Chinese military organisation’s unique characteristics and the rescuers’ experiences, making it more suited to the needs and realities of these groups compared to traditional debriefing. This indicates that new approaches, such as the 512 PIM, could provide additional advantages over conventional interventions like CISD. Being tailored for populations facing intense trauma, such as rescue workers and military personnel, it may offer better adaptation to stressful situations and mitigate long-term psychological effects. Furthermore, since this model has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety, its implementation could lead to a significant decrease in the prevalence of these disorders among trauma-exposed workers, thereby playing a crucial role in their prevention. Although initially developed for military contexts, the 512 PIM holds the potential to be utilized in other sectors that encounter high levels of stress, such as emergency services, healthcare workers, and police forces.

In the future, if widely adopted, the 512 PIM could become a standard for post-traumatic stress management in high-risk teams, improving their mental well-being and crisis response capability.

Although we found little evidence to support the effectiveness of post-deployment or post-incident interventions, none of the studies reviewed reported adverse effects related to such interventions, except for the increased alcohol consumption noted by Adler et al. (2008). It is also undetermined whether this was a direct consequence of the intervention or an improved social climate.

This contrasts with earlier research suggesting that psychological debriefing, in some instances, is not only comparable to but also potentially less effective than educational or control interventions in preventing or reducing disorders such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, or general psychological morbidity. Some studies indicate that single-session debriefing may increase the risk of developing PTSD and depression, raising questions about its routine use in unselected trauma victims [

50,

51].

Consider the greater homogeneity and specialization of the participant groups in the studies selected for this review, which included soldiers, military rescuers, emergency personnel, paramedics, and emergency medical technicians (EMTs), all of whom were exposed to very similar traumatic situations or events, such as deployment in a common environment. However, the previous debriefing reviews mentioned above [

38,

51] the general untrained population who had experienced trauma of varying natures.

The analysis presented in this review has several notable strengths. Firstly, it covers various interventions and population groups, providing a holistic view of the effectiveness of strategies such as debriefing and other measures designed to mitigate the impact of traumatic events. A more comprehensive understanding of how these interventions function in different high-pressure contexts is achieved by including military personnel, emergency responders, and healthcare workers. This breadth of analysis is essential, as not all populations respond in the same way to trauma, and understanding these differences can aid in tailoring interventions to the specific needs of each group.

Additionally, the review is not confined to a single intervention but compares various approaches, including Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD), stress management (SMC), and innovative strategies such as the “512 PIM.” This comparison enhances the analysis by pinpointing the advantages and disadvantages of each intervention, offering a more nuanced and comprehensive perspective on their effectiveness.

Finally, the review is notable for examining positive outcomes and considering possible side effects. By pointing out, for example, the increase in alcohol consumption in some groups after debriefing, the review adds a critical layer of depth to the analysis, questioning the overall efficacy of the intervention and highlighting the importance of monitoring possible long-term risks.

However, some important limitations should be considered. Although several studies are included, the evidence on the effectiveness of the interventions is often limited or inconsistent. This complicates drawing definitive conclusions and sometimes diminishes the ability to generalize the results to various populations or contexts.

Furthermore, the heterogeneity of the methods used in the reviewed studies—across aspects such as design, duration of follow-up, type of intervention, and participant characteristics—complicates direct comparisons among them. This variability and the poor methodological quality of the studies, as indicated by the PEDro scale, may undermine the ability to draw solid conclusions regarding which intervention is genuinely more effective.

Another significant challenge is the difficulty in controlling for contextual variables. Factors such as the type of trauma experienced, differences in organisational culture, or specific characteristics of the groups studied are not always uniformly accounted for. This can significantly influence the results and restrict the ability to apply the findings to other contexts. Effective interventions in one setting may not be equally successful in another, highlighting the necessity to tailor interventions to the specific context.

A crucial factor is the lack of long-term follow-up in numerous studies. By failing to evaluate the effects of interventions beyond a few months, we miss the opportunity to understand whether the strategies employed have a lasting impact on PTSD, depression, anxiety, or overall well-being. This poses a significant issue, as the effects of trauma can unfold over many years, and the effectiveness of an intervention can only be fully evaluated if its long-term consequences are taken into consideration.

Future research on debriefing should concentrate on developing more homogeneous and controlled studies that address the methodological limitations and heterogeneity observed in this review. Trials with long-term follow-up are crucial for assessing the sustained effects of interventions, tailoring them to specific contexts, and considering factors such as organisational culture and type of trauma. Additionally, personalised and multimodal approaches, such as the 512 PIM, should be investigated to enhance the efficacy of debriefing.

Public Health Perspective

From a public health perspective, the mental health of rescue teams is vital for ensuring a resilient healthcare response. When mentally fit rescue personnel are better equipped to deliver high-quality care and support to individuals experiencing crises [

52]Thus, integrating mental health support mechanisms into rescue teams’ operational protocols enhances their resilience and contributes to the overall effectiveness of public health responses in the face of environmental challenges.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this systematic review offers a comprehensive and nuanced perspective on the effectiveness of posttraumatic interventions, including debriefing and other strategies, in rescue teams subjected to high levels of stress. While some approaches, such as 512 PIM, have demonstrated promising results in specific contexts, the overall evidence regarding the efficacy of debriefing remains limited and inconsistent. Additionally, potential adverse effects, including increased alcohol consumption, were noted, highlighting the need for caution in the routine application of these interventions.

The heterogeneity in the studies reviewed, the lack of long-term follow-up, and the difficulty in controlling for contextual variables are significant limitations that hinder definitive conclusions from being drawn. Nevertheless, comparing various interventions and including diverse populations offers a valuable starting point for future research. We emphasise the need for more rigorous studies, employing context-specific approaches and longer follow-up periods, to more accurately assess the sustained impact of these interventions on psychological health. We cannot determine any specific effect on mountain rescue groups, as their impact on these particular groups has not been analysed to date.

Author Contributions

The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, FGM, FA and GVR.; methodology, FA, PGA, BG, JPN, GVR and FGM.; investigation, FA, PGA, BG, JPN, GVR and FGM.; resources, FA, PGA, BG, JPN, GVR and FGM.; writing—original draft preparation, FA, GVR and FGM.; writing—review and editing, FA, PGA, BG, JPN, GVR and FGM.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, GVR and FGM; project administration, PGA, BG, JPN, GVR and FGM.; funding acquisition, GVR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by Catedra de Montaña de la Universidad de Zaragoza, Diputación provincial de Huesca y Ayuntamiento de Huesca..

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Heber A, Testa V, Groll D, et al. Glossary of terms: A shared understanding of the common terms used to describe psychological trauma, version 3.0. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2023;43(10-11):S1-S999. [CrossRef]

- Oliphant R. Healthy Minds, Safe Communities, Supporting Our Public Safety Officers through a National Strateegy for Operational Stress Injuries: Report of the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security. House of Commons. Parliament; 2016.

- Courtney JA, Francis AJP, Paxton SJ. Caring for the country: fatigue, sleep and mental health in Australian rural paramedic shiftworkers. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):178-186. [CrossRef]

- Cramm H, Richmond R, Jamshidi L, et al. Mental Health of Canadian Firefighters: The Impact of Sleep. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24). [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Wang Z, Liu H, Ren M, Feng D. Physical and mental health problems of Chinese front-line healthcare workers before, during and after the COVID-19 rescue mission: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(10):e059879. [CrossRef]

- Bo Y, Liu H, Zhang M, et al. Knowing the Psychological Risks of Anti-epidemic Rescue Teams for COVID-19 by Simplified Risk Probability Scale. Published online December 13, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Carleton RN, Afifi TO, Taillieu T, et al. Exposures to potentially traumatic events among public safety personnel in Canada. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2019;51(1):37-52. [CrossRef]

- Galatzer-Levy IR, Madan A, Neylan TC, Henn-Haase C, Marmar CR. Peritraumatic and trait dissociation differentiate police officers with resilient versus symptomatic trajectories of posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(5):557-565. [CrossRef]

- Carleton RN, Afifi TO, Turner S, et al. Mental Disorder Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(1):54-64. [CrossRef]

- Williamson JB, Jaffee MS, Jorge RE. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Anxiety-Related Conditions. Continuum Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2021;27(6):1738-1763. [CrossRef]

- Pary R, Micchelli AN, Lippmann S. How We Treat Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2021;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Ayuso Mateos JL, Vieta Pascual E, Arango López C, Bagney Lifante A, American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 : Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de Los Trastornos Mentales. 5a. Médica Panamericana; 2014.

- Boffa JW, Stanley IH, Smith LJ, et al. PTSD Symptoms and Suicide Risk in Male Firefighters: The Mediating Role of Anxiety Sensitivity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(3):179. [CrossRef]

- Hoell A, Kourmpeli E, Dressing H. Work-related posttraumatic stress disorder in paramedics in comparison to data from the general population of working age. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Skeffington PM, Rees CS, Mazzucchelli T. Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder within fire and emergency services in Western Australia. Aust J Psychol. 2017;69(1):20-28. [CrossRef]

- Tomaka J, Magoc D, Morales-Monks SM, Reyes AC. Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Alcohol-Related Outcomes Among Municipal Firefighters. J Trauma Stress. 2017;30(4):416-424. [CrossRef]

- Statista. Number of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) cases registered in Spain from 2011 to 2022. Statista Research Department.

- Katsavouni F, Bebetsos E, Malliou P, Beneka A. The relationship between burnout, PTSD symptoms and injuries in firefighters. Occup Med (Lond). 2016;66(1):32-37. [CrossRef]

- Almutairi MN, Azza AA. Burnout and coping methods among emergency medical services professionals. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:271-27. [CrossRef]

- Who. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases.

- Stevelink SAM, Pernet D, Dregan A, et al. The mental health of emergency services personnel in the UK Biobank: a comparison with the working population. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Informa Health Care. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Second. (Nutt JD, Stein B M, Zohar J, eds.). Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2009.

- Gesteira C, García-Vera MP, Sanz J, Gesteira C, García-Vera MP, Sanz J. Porque el Tiempo no lo Cura Todo: Eficacia de la Terapia Cognitivo-conductual Centrada en el Trauma para el Estrés postraumático a muy Largo Plazo en Víctimas de Terrorismo. Clin Salud. 2018;29(1):9-13. [CrossRef]

- Kar N. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7(1):167. [CrossRef]

- Coimbra MAR, Ikegami ÉM, Souza LA, Haas VJ, Barbosa MH, Ferreira LA. Eficacia de un programa en el aumento de las estrategias de coping en bomberos: ensayo clínico aleatorizado. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2024;32. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell JT, Everly GS. Critical Incident Stress Management: An Operations Manual for CISD, Defusing and Other Group Crisis Intervention Services. 3rd ed. Chevron Publishing Corporation; 2001.

- Mitchell JT, Everly GS. Critical Incident Stress Debriefing. Ellical; 1993.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Management of Conditions Specifically Related to Stress.; 2013. Accessed September 9, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241505406.

- Basiaga-Pasternak J, Pomykała S, Cichosz A. Stress in volunteer mountain rescue teams. Studies in Sport Humanities. 2015;17.

- Sandoval JB, Hooshmand M, Sarik DA. Beating Burnout with Project D.E.A.R.: Debriefing Event for Analysis and Recovery. Nurse Lead. 2023;21(5):579-585. [CrossRef]

- Aulagnier M, Verger P, Rouillon F. Efficacité du « débriefing psychologique » dans la prévention des troubles psychologiques post-traumatiques: Efficiency of psychological debriefing in preventing post-traumatic stress disorders. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2004;52(1):67-79. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu G, Colon J, Barlow D, Ferris D. Daily Informal Multidisciplinary Intensive Care Unit Operational Debriefing Provides Effective Support for Intensive Care Unit Nurses. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2016;35(4):175-180. [CrossRef]

- Castro R, Campero L, Hernández B. La investigación sobre apoyo social en salud: situación actual y nuevos desafíos. Rev Saude Publica. 1997;31(4):425-435. [CrossRef]

- Durá E, Garcés J. La teoría del apoyo social y sus implicaciones para el ajuste psicosocial de los enfermos oncológicos. Rev Psicol Soc. 1991;6(2):257-271. [CrossRef]

- Tamrakar T, Murphy J, Elklit A. Was Psychological Debriefing Dismissed Too Quickly? Crisis, Stress, and Human Resilience: An International Journal. 2019;1(3):146-155.

- Arancibia M, Leyton F, Morán-Kneer J, et al. Psychological debriefing in acute traumatic events: Evidence synthesis. Medwave. 2022;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Vignaud P, Lavallé L, Brunelin J, Prieto N. Are psychological debriefing groups after a potential traumatic event suitable to prevent the symptoms of PTSD? Psychiatry Res. 2022;311:114503. [CrossRef]

- Rose SC, Bisson J, Churchill R, Wessely S. Brief psychological interventions (“debriefing”) for trauma-related symptoms and the prevention of post traumatic stress disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2002(2). [CrossRef]

- Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Urrútia G, Romero-García M, Alonso-Fernández S. Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021;74(9):790-799. [CrossRef]

- Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Manual Cochrane Para Revisiones Sistemáticas de Intervenciones, Versión 6.4 (Actualizado En Agosto de 2023). . Cochrane; 2023.

- Santos CMDC, Pimenta CADM, Nobre MRC. Estrategia PICO para la construcción de la pregunta de investigación y la búsqueda de evidencias. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2007;15(3):508-511. [CrossRef]

- Verhagen AP, De Vet HCW, De Bie RA, et al. The Delphi list: A criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(12):1235-1241. [CrossRef]

- Adler AB, Litz BT, Castro CA, et al. A group randomized trial of critical incident stress debriefing provided to U.S. peacekeepers. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(3):253-263. [CrossRef]

- Tuckey MR, Scott JE. Group critical incident stress debriefing with emergency services personnel: a randomized controlled trial. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2014;27(1):38-54. [CrossRef]

- Macnab A, Sun C, Lowe J. Randomized, controlled trial of three levels of critical incident stress intervention. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2003;18(4):367-371. [CrossRef]

- Adler AB, Bliese PD, McGurk D, Hoge CW, Castro CA. Battlemind debriefing and battlemind training as early interventions with soldiers returning from iraq: Randomization by platoon. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;77(5):928-940. [CrossRef]

- Deahl M, Srinivasan M, Jones N, Thomas J, Neblett C, Jolly A. Preventing psychological trauma in soldiers: The role of operational stress training and psychological debriefing. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 2000;73(1):77-85. [CrossRef]

- Wu S, Zhu X, Zhang Y, et al. A new psychological intervention: “512 Psychological Intervention Model” used for military rescuers in Wenchuan Earthquake in China. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(7):1111-1119. [CrossRef]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(5):748-766. [CrossRef]

- Rose SC, Bisson J, Churchill R, Wessely S. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online April 22, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Bisson JI, Jenkins PL, Alexander J, Bannister C. Randomised controlled trial of psychological debriefing for victims of acute burn trauma. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171(JULY):78-81. [CrossRef]

- Deng J, Kou X, Ma H, Niu A, Luo Y. Qualitative study on the core competencies of nursing personnel in emergency medical rescue teams at comprehensive hospitals in Chongqing, China. BMJ Open. 2024;14(4). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).