Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Outlines

2.1. Materials and Mix Proportions

2.2. Test Specimens

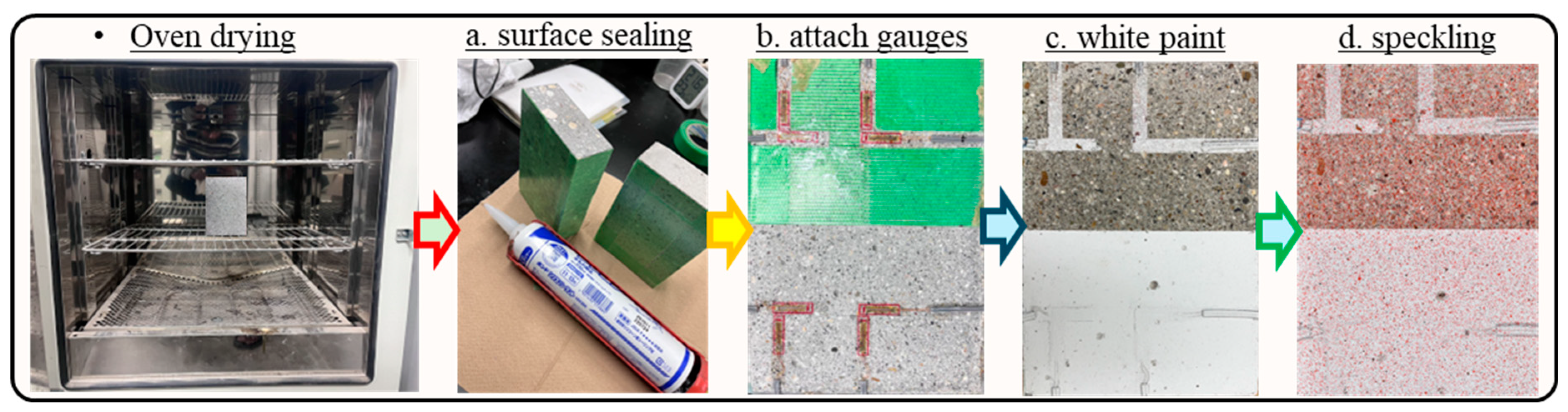

- Seal all surfaces of the specimen by applying silicone except for one longer side/edge (to allow water penetration) and the top face (to be used for DICM), where masking tape was applied to avoid traces of silicone while its application on other sides sealed them against water penetration.

- Cut the masking tape only at designated positions on the planner face at the marked points to attach the strain gauges which also served as guides for positioning of gauges in a particular direction at intended points, as illustrated in Figure 1. The face for DICM was divided into two halves, i.e., the painted side (P) and the unpainted side (NP), over which eight general-purpose surface strain gauges with a gauge length of 10 mm were attached. Moreover, the arrangement of gauges was kept identical on both halves in the x- and y-axes with respect to the direction of water penetration.

- After the attachment of surface strain gauges, the specimen was placed in a glass chamber and kept there for approximately 24 h. Afterwards, the half face was coated with matte-type white spray paint to decrease the influence of color change and to achieve good quality speckles for DICM, and the other half face was left unpainted to differentiate between DICM measurements during the water absorption process. It’s worth mentioning that matte-type white spray paint was used for coating the layer because its layer did not make any thin film over the surface, and also it does not affect the deformation measurements in DICM (for details readers may consult [46,58]).

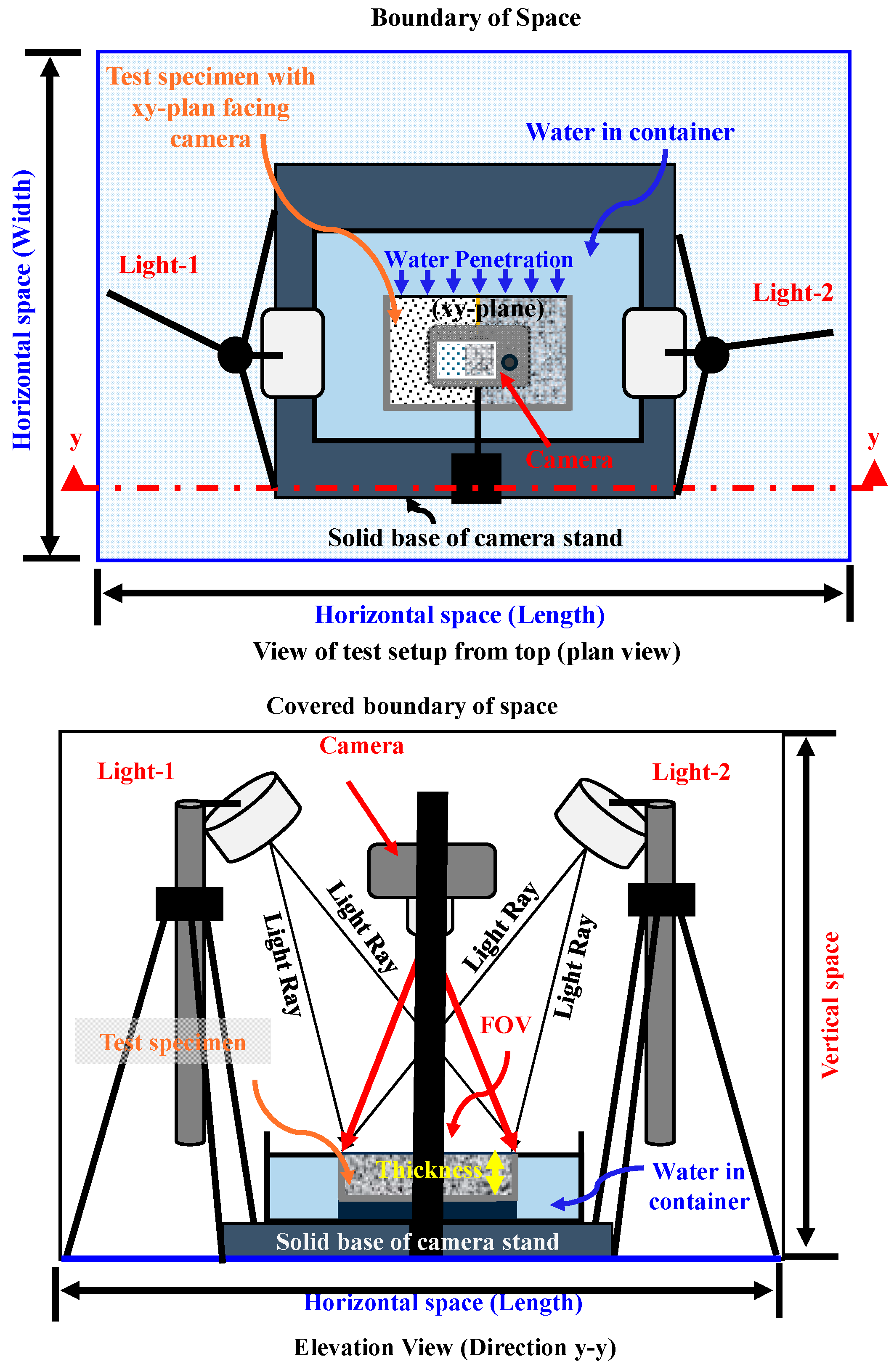

2.3. Test Methods

2.3.1. Water Absorption Test

2.3.2. Description of Digital Image Correlation Method (DICM)

2.3.3. Uni-axial Compression Test

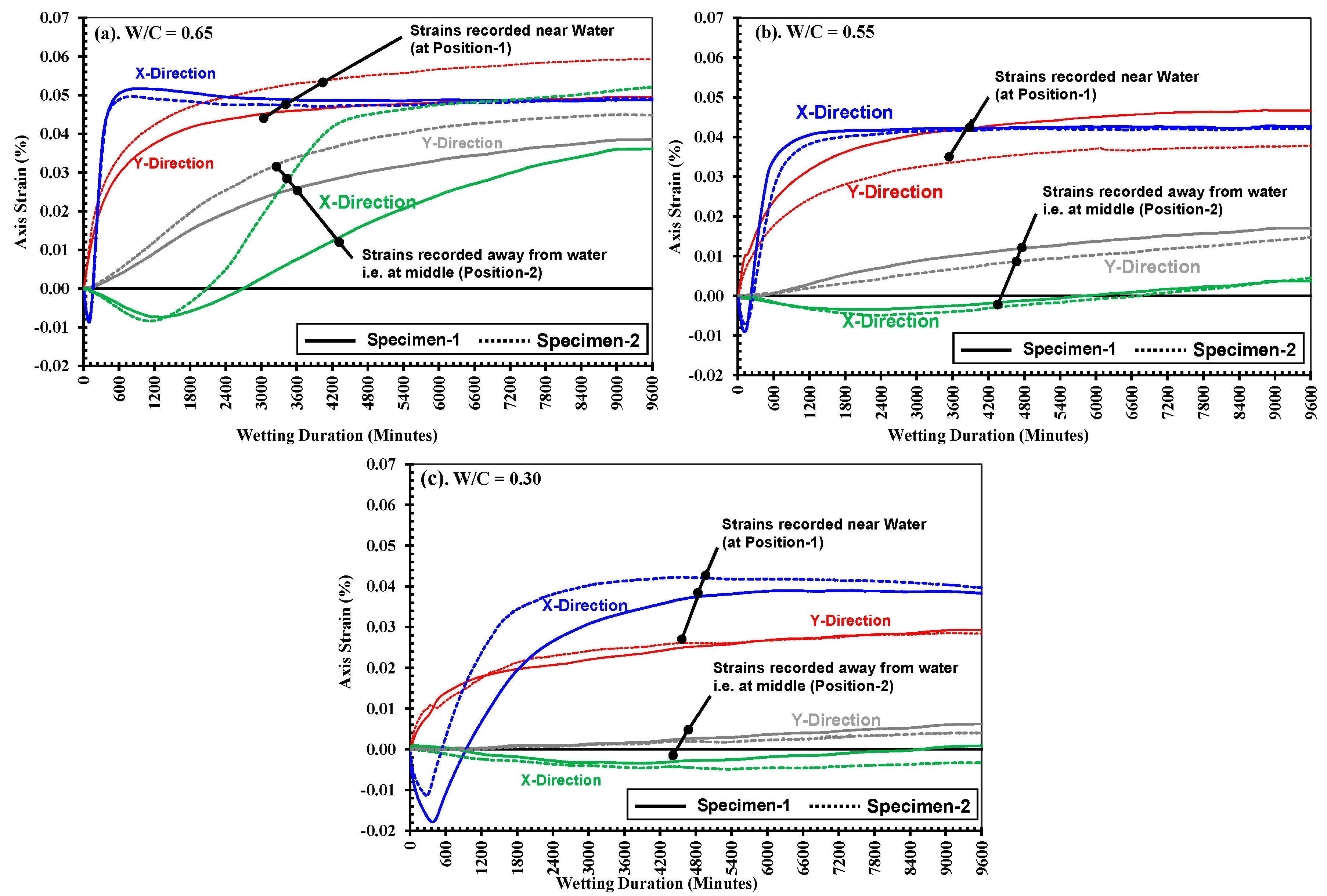

3. Determination of strain development during water absorption using surface strain gauges

3.1. Strain development along x-axis and y-axis directions

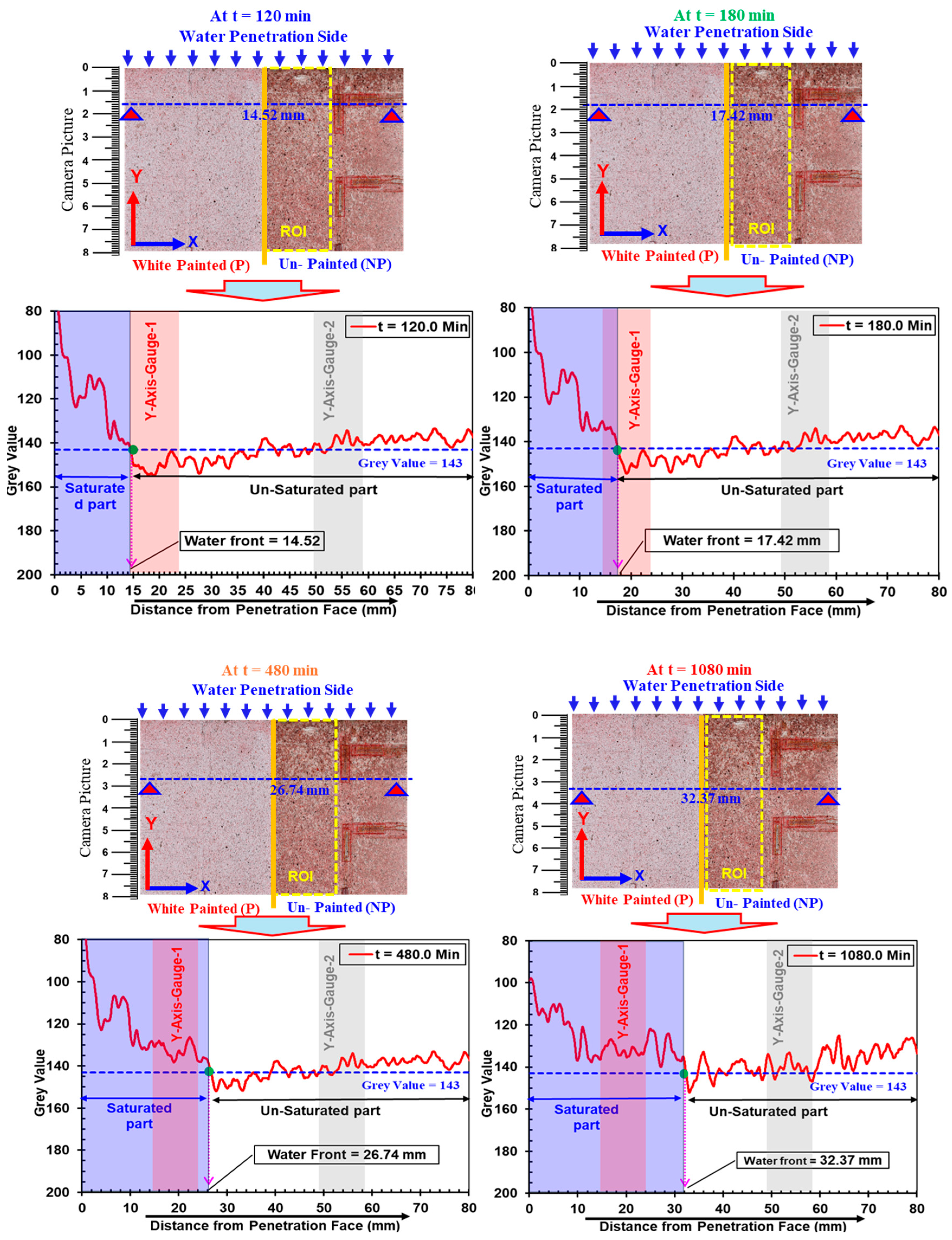

3.2. Water absorption depth determined by grey scale

3.3. Three-Dimensional Deformation Behavior during Water Absorption

- At Stage-I: The waterfront reached the y-axis gauge at position-1 as shown by the red mark in top view, indicating expansion in the saturated part of the specimen, and the specimen experienced the expansion along the x, y, and z-axis. Since the portion below the gauge is still unsaturated, this part exhibited contraction due to small bending occurring in z-axis direction. However, the positive strain in the x-axis is observed owing to the uniform expansion.

- At stage-II: The half of the y-axis strain gauge is covered in the saturated part (indicating positive strain) and half unsaturated (negative strain occurs due to contraction as a result of bending deformation), so both the strains balance each other, and the y-axis strain gets neutralized, but at the same time, the x-axis strain continues showing a gradual increase due to continued expansion.

- At stage-III: The moment when the full underneath part of y-axis gauge is saturated and the maximum possible deformations along y-axis has been reached. There was a rapid increase in the y-axis strain just before reaching this stage, e.g., when water progressed through its gauge, but soon after the full part below the y-axis strain gauge gets saturated, and the stabilized condition in expansion is achieved.

- At stage-IV: The water penetration increases resulting in more progressed volumetric changes in the specimen.

4. Implementation of DICM to Evaluate Strain Development during water penetration

4.1. Spatial distribution of strain during water absorption in low quality mortars

4.1.1. Variation of strain along x-axis

4.1.2. Variation of strain along y-axis

4.2. Strain recorded by surface strain gauges vs. strains by DICM (Pɛ_DICM vs. Pɛ_gauges)

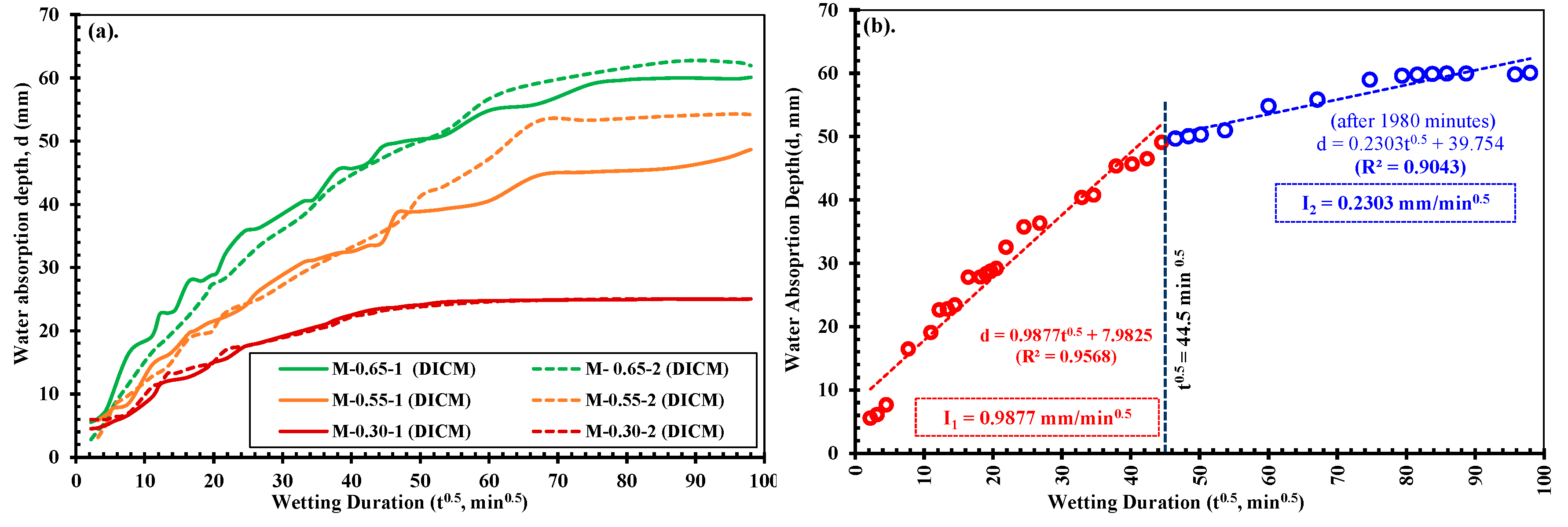

4.3. Evaluating water absorption characteristics by DICM

4.3.1. Comparison of progression of full field deformations in y-Axis direction

4.3.2. Comparison of progression of full field deformations in y-axis direction

5. Relationship between water absorption characteristics and the compressive properties of concretes of different strengths

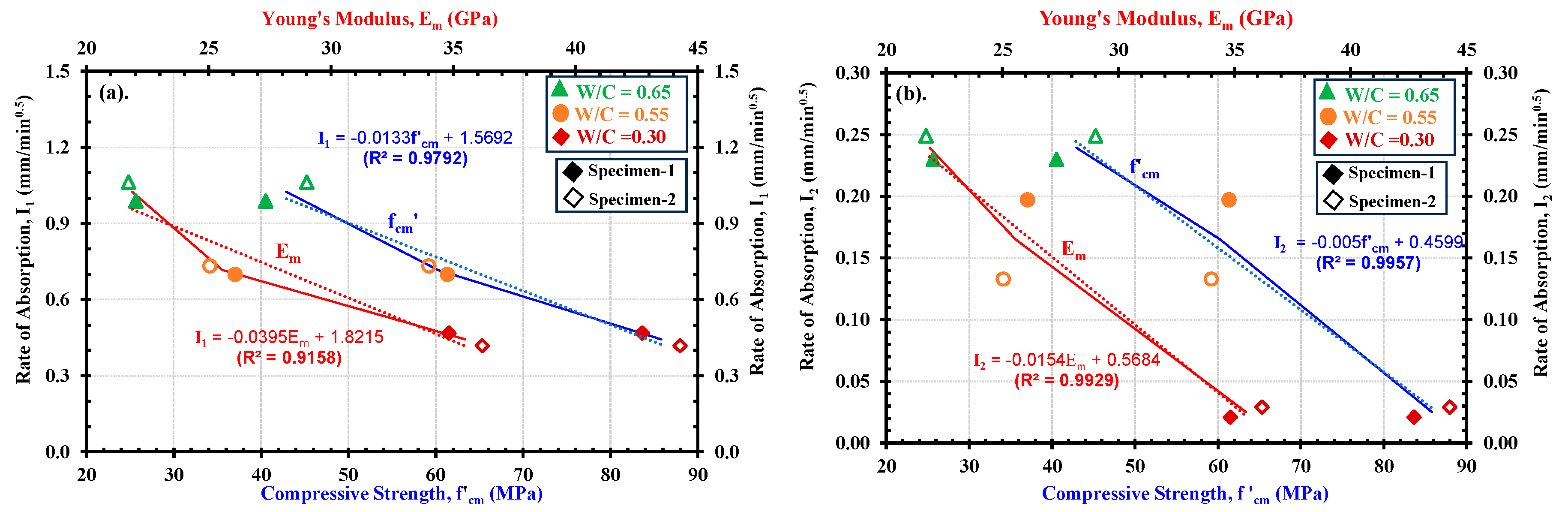

5.1. Relationship between Rate of Water Absorption (I) and the Mechanical Properties

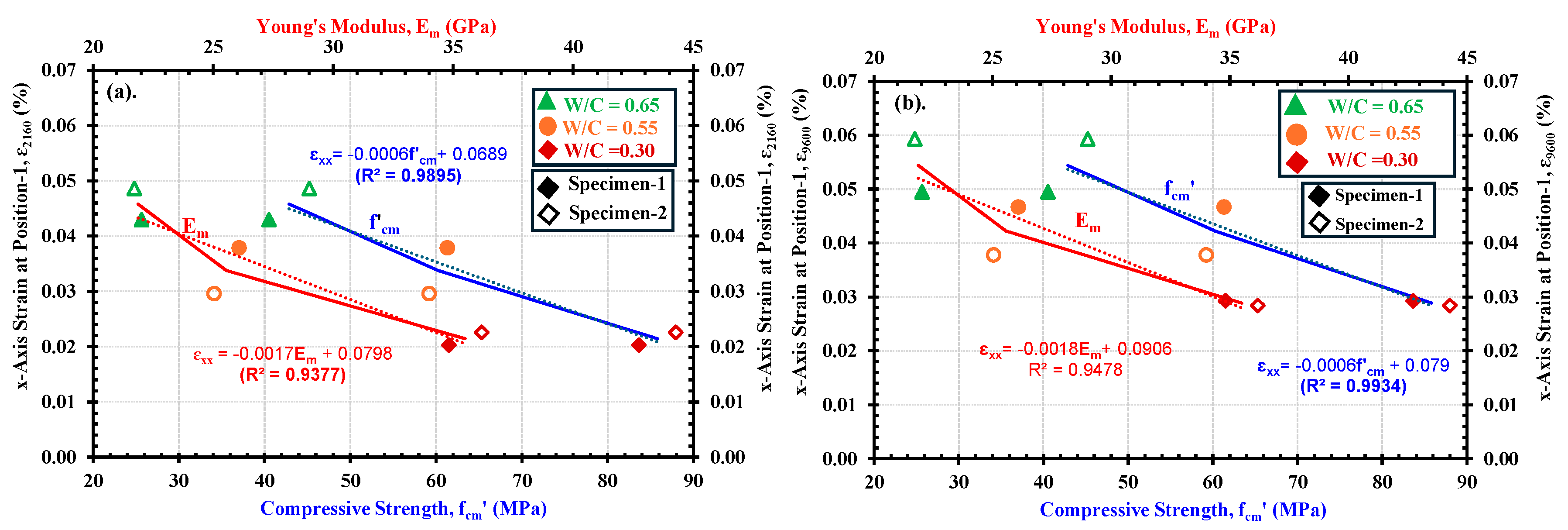

5.2. Relationship between Maximum Developed Strain along x-axis (i.e., ɛxx) in Fully Saturated Regions and the Mechanical Properties

6. Conclusions

- Water ingress has an instant effect on the volume changes (expansion) in the cement-based materials owing to the hygroscopic nature of the cement hydrates (i.e., the C-S-H). Moreover, the continuous monitoring/evaluation of strains at specimens’ surface during the water absorption process indirectly provides physical evidence of such internal swelling phenomenon in concrete materials during the process of water absorption.

- DICM is an effective method to evaluate the volumetric changes in concrete materials by evaluating the strains at the specimen surfaces during the water absorption process. However, the calculations in DICM are strongly influenced by the changes in the contrast of the image within the saturated regions of the test specimen surfaces and result in pseudo strains. Therefore, applying DICM with water absorption in concrete materials requires their surface to be coated with matte-type spray paints first and then enhanced by speckling to achieve good test results.

- The deformability and the water absorption depth/rate in concrete materials are directly related to each other and depend on their mix compositions. The progression in surface strains measured in DICM provided more reliable evaluations of water ingress rates into the mortars, thereby indicating the closest boundary between primary and secondary liquid water absorption processes. The water absorption depths and the tendencies in expansion strains in saturated parts were different for specimens of three different strengths. However, in all three strengths, the depth (d) vs. square root time (t0.5) curves deviated from a linear relationship after the same time, i.e., 1980 min, resulting in highlighting that the largest strains occur within the primary absorption period, after which strains progress slowly owing to the slow water absorption in the secondary absorption period.

- Concrete materials with lower w/c ratios (high strength) experience lower water absorption rates. On the other hand, mortars with lower strengths will allow more rapid water penetration and other liquids or ions owing to the presence of more pore fractions. Moreover, the primary and secondary absorption rates showed almost linear relationships with mechanical properties such as compressive strength and the Young’s modulus of mortars.

- The volume changes in mortars due to water absorption at the saturated part have a clear relationship with the mechanical properties. The results indicated that the evaluated durability properties related to water permeation not only relate to the water absorption rate but also to the compressive strength, Young’s modulus, and the volume change due to saturation.

- In this study, DICM was employed to determine the water absorption characteristics in ordinary mortar specimens with simply set test arrangements. The test results yielded excellent relationships between mechanical properties and water absorption characteristics, which are good indicators for assessment of the durability in concrete materials. Although some limitations incurred, like out-of-plane bending, can affect the accuracy of the measurements. In the future, the established framework will be extended in various aspects by improving the precision in tackling with the out-of-plane bending and will be involved in the evaluation of absorption characteristics in slices cut from core samples of an existing structure, checking the durability of materials designed/proposed for sustainable constructions and so on.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- P.K. Mehta, P.J.M. Monteiro. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, Materials. 4th ed. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc; 2014.

- Castro J, Bentz D, Weiss J. Effect of sample conditioning on the water absorption of concrete. Cem Concr. Compos. 2011;33(8):805–813. [CrossRef]

- Sabir BB, Wild S, O’farrell M. A water sorptivity test for mortar and concrete. Materials and Structures/Matriaux et Constructions. 1998.

- Maltais Y, Samson E, Marchand J. Predicting the durability of Portland cement systems in aggressive environments—Laboratory validation. Cem Concr Res. 2004;34(9):1579–1589. [CrossRef]

- Khanzadeh Moradllo M, Sudbrink B, Ley MT. Determining the effective service life of silane treatments in concrete bridge decks. Constr Build Mater. 2016;116:121–127.

- Mendes A, Sanjayan JG, Gates WP, et al. The influence of water absorption and porosity on the deterioration of cement paste and concrete exposed to elevated temperatures, as in a fire event. Cem Concr Compos. 2012;34(9):1067–1074. [CrossRef]

- Hearn N, Hooton R, Mills R. Pore Structure and Permeability. Significance of Tests and Properties of Concrete and Concrete-Making Mate rials. 100 Barr Harbor Drive, PO Box C700, West Conshohocken, PA 19428-2959: ASTM International; p. 240-240–23.

- Espinosa RM, Franke L. Influence of the age and drying process on pore structure and sorption isotherms of hardened cement paste. Cem Concr Res. 2006;36(10):1969–1984. [CrossRef]

- Krus M, Hansen KK, Kiinzel HM. Porosity and liquid absorption of cement paste. Materials and Structures/Mat~riaux et Constructions.

- Hanžič L, Ilić R. Relationship between liquid sorptivity and capillarity in concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2003;33(9):1385–1388. [CrossRef]

- Norman R. Physics and Thermodynamics of Capillary. Ind Eng Chem. 1970;62(6):32–56.

- Hong S, Yao W, Guo B, et al. Water distribution characteristics in cement paste with capillary absorption. Constr Build Mater. 2020;240. [CrossRef]

- Hall C. Water sorptivity of mortars and concretes: a review. 1989. [CrossRef]

- Martys NS, Ferraris CF. Capillary transport in mortars and concrete. Cement and concrete research. 1997 gg1;27(5):747-60. [CrossRef]

- Hall C. Anomalous diffusion in unsaturated flow: Fact or fiction? Cem Concr Res. 2007. p. 378–385.

- Zhang SP, Zong L. Evaluation of Relationship between Water Absorption and Durability of Concrete Materials. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering. 2014;2014:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zheng F, Hong S, Hou D, et al. Rapid visualization and quantification of water penetration into cement paste through cracks with X-ray imaging. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;125. [CrossRef]

- Dias WPS. Reduction of concrete sorptivity with age through carbonation. [CrossRef]

- Khanzadeh Moradllo M, Ley MT. Quantitative measurement of the influence of degree of saturation on ion penetration in cement paste by using X-ray imaging. Constr Build Mater. 2017;141:113–129.

- Henkensiefken R, Castro J, Bentz D, et al. Water absorption in internally cured mortar made with water-filled lightweight aggregate. Cem Concr Res. 2009;39(10):883–892. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1585. Test Method for Measurement of Rate of Absorption of Water by Hydraulic-Cement Concretes. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International; 2020. Available from: http://www.astm.org/cgi-bin/resolver.cgi?C1585-20.

- Zhutovsky S, Douglas Hooton R. Role of sample conditioning in water absorption tests. Constr Build Mater. 2019;215:918–924. [CrossRef]

- Van Belleghem B, Montoya R, Dewanckele J, et al. Capillary water absorption in cracked and uncracked mortar—A comparison between experimental study and finite element analysis. Constr Build Mater. 2016;110:154–162. [CrossRef]

- Alderete NM, Villagrán Zaccardi YA, De Belie N. Physical evidence of swelling as the cause of anomalous capillary water uptake by cementitious materials. Cem Concr Res. 2019;120:256–266. [CrossRef]

- L. Tang NL-O, P.A.M. Basheer. Resistance of Concrete to Chloride Ingress: Testing and Modelling. London and New York: CRC Press; 2012.

- Fries N, Dreyer M. An analytic solution of capillary rise restrained by gravity. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2008;320(1):259–263. [CrossRef]

- Muller ACA, Scrivener KL, Gajewicz AM, et al. Use of bench-top NMR to measure the density, composition and desorption isotherm of C-S-H in cement paste. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. 2013;178:99–103.

- Huang L, Tang L, Dong Z, et al. Effect of curing regimes on composition and microstructure of blended pastes: Insight into later-age hydration mechanism. Cem Concr Res. 2025;189:107785. [CrossRef]

- Wyrzykowski M, McDonald PJ, Scrivener KL, et al. Water Redistribution within the Microstructure of Cementitious Materials due to Temperature Changes Studied with 1H NMR. Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2017;121(50):27950–27962. [CrossRef]

- Rymarczyk T. New methods to determine moisture areas by electrical impedance tomography. International Journal of Applied Electromagnetics and Mechanics. 2016;52(1–2):79–87. [CrossRef]

- Smyl D, Rashetnia R, Seppänen A, et al. Can Electrical Resistance Tomography be used for imaging unsaturated moisture flow in cement-based materials with discrete cracks? Cem Concr Res. 2017;91:61–72.

- Dong B, Gu Z, Qiu Q, et al. Electrochemical feature for chloride ion transportation in fly ash blended cementitious materials. Constr Build Mater. 2018;161:577–586. [CrossRef]

- Bigger R, Blaysat B, Boo C, et al. A Good Practices Guide for Digital Image Correlation [Internet]. Jones E, Iadicola M, editors. 2018. Available from: http://idics.org/guide/.

- Oats RC, Dai Q, Head M. Digital Image Correlation Advances in Structural Evaluation Applications: A Review. Practice Periodical on Structural Design and Construction. 2022;27(4). [CrossRef]

- Bogusz P, Krasoń W, Pazur K. Application of Digital Image Correlation for Strain Mapping of Structural Elements and Materials. Materials. 2024;17(11). [CrossRef]

- Mousa MA, Yussof MM, Hussein TS, et al. A Digital Image Correlation Technique for Laboratory Structural Tests and Applications: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pan B, Qian K, Xie H, et al. Two-dimensional digital image correlation for in-plane displacement and strain measurement: A review. Meas Sci Technol. 2009;20(6). [CrossRef]

- Khoo SW, Karuppanan S, Tan CS. A review of surface deformation and strain measurement using two-dimensional digital image correlation. Metrology and Measurement Systems. Polish ACAD Sciences Committee Metrology and Res Equipment; 2016. p. 461–480. [CrossRef]

- Pan B, Qian K, Xie H, et al. Two-dimensional digital image correlation for in-plane displacement and strain measurement: A review. Meas Sci Technol. 2009;20(6). [CrossRef]

- Peters WH, Ranson WF. Digital imaging techniques in experimental stress analysis [Internet]. 1982. Available from: http://spiedl.org/terms.

- Pan B, Li K. A fast digital image correlation method for deformation measurement. Opt Lasers Eng. 2011;49(7):841–847. [CrossRef]

- Zhong FQ, Indurkar PP, Quan CG. Three-dimensional digital image correlation with improved efficiency and accuracy. Measurement (Lond). 2018;128:23–33. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, He X, Wang Q, et al. Deformation field and crack analyses of concrete using digital image correlation method. Frontiers of Structural and Civil Engineering. 2019;13(5):1183–1199. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, He X, Wang Q, et al. Deformation field and crack analyses of concrete using digital image correlation method. Frontiers of Structural and Civil Engineering. 2019;13(5):1183–1199. [CrossRef]

- Yudan Jiang, Zuquan Jin, Tiejun Zhao, et al. Strain Field of Reinforced Concrete under Accelerated Corrosion by Digital Image Correlation Technique. Journal of Adv Conc Tech. 2017;15:290–299. [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen IMG, Kragh C, Cardinaud G, et al. Quantification of plastic shrinkage cracking in mortars using digital image correlation. Cem Concr Res. 2019;123. [CrossRef]

- Dzaye ED, Tsangouri E, Spiessens K, et al. Digital image correlation (DIC) on fresh cement mortar to quantify settlement and shrinkage. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering. 2019;19(1):205–214. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa Keigo, Hashimoto Chihiro, Go Igarashi, et al. Time-dependent strain distribution of mortar in concrete during water uptake monitored by digital image correlation method. Cement Science and Concrete Technology. 2023;77(1):222–230.

- M.Usman, H.Nakamura, T.Miura. Application of Digital Image Correlation (DIC) Method to Evaluate the Water Absorption in Different Qualities of Concrete. In: R. Henry, A. Palermo, editors. fib Symposium 2024 11-13 November 2024, New Zealand. Christchurch; 2024. p. 1105–1114.

- Reu P. All about speckles: Contrast. Exp Tech. 2015;39(1):1–2.

- Pan B, Xie H, Wang Z. Equivalence of digital image correlation criteria for pattern matching. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Basheer L, Cleland DJ. Durability and water absorption properties of surface treated concretes. Mater Struct. 2011;44(5):957–967. [CrossRef]

- Baghabra Al-Amoudi OS, Al-Kutti WA, Ahmad S, et al. Correlation between compressive strength and certain durability indices of plain and blended cement concretes. Cem Concr Compos.2009;31(9):672–676. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang S, Wang Q, Zhang M. Water absorption behaviour of concrete: Novel experimental findings and model characterization. Journal of Building Engineering. 2022;53. [CrossRef]

- Snoeck D, Velasco LF, Mignon A, et al. The influence of different drying techniques on the water sorption properties of cement-based materials. Cem Concr Res. 2014;64:54–62. [CrossRef]

- Wu Z, Wong HS, Buenfeld NR. Influence of drying-induced microcracking and related size effects on mass transport properties of concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2015;68:35–48. [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin JJ, Tamtsia BT. Effect of Drying Methods on Microstructural Changes in Hardened Cement Paste: an A. C. Impedance Spectroscopy Evaluation. Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology. 2004;2(1):113-20. [CrossRef]

- Szalai S, Fehér V, Kurhan D, et al. Optimization of Surface Cleaning and Painting Methods for DIC Measurements on Automotive and Railway Aluminum Materials. Infrastructures (Basel). 2023;8 (2):27. [CrossRef]

- Miura T, Sato K, Nakamura H. The role of microcracking on the compressive strength and stiffness of cracked concrete with different crack widths and angles evaluated by DIC. Cem Concr Compos. 2020;114:103768. [CrossRef]

- Schreier H, Orteu J-J, Sutton MA. Image Correlation for Shape, Motion and Deformation Measurements. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2009. [CrossRef]

- Sutton MA, Turner JL, Bruck HA, et al. Full.field Representation of Discretely Sampled Surface Deformation for Displacement and Strain Analysis. 1991 (6);31:168-77. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi GO, Maruyama Ippei. A pilot study on a microscopic technique for observing the swelling behaviour of mortar during re-absorption of water. Annual conference of JSCE (in Japanese). 2023. p. 602.

- Zheng F, Jiang R, Dong B, et al. Visualization and quantification of water penetration in cement pastes with different crack sizes. Constr Build Mater. 2022;341. [CrossRef]

- Reu PL. A Realistic Error Budget for Two Dimension Digital Image Correlation.

- Dong YL, Pan B. A Review of Speckle Pattern Fabrication and Assessment for Digital Image Correlation. Exp Mech. 2017;57(8):1161–1181. [CrossRef]

- Hong S, Yao W, Guo B, et al. Water distribution characteristics in cement paste with capillary absorption. Constr Build Mater. 2020; (4);240:117767. [CrossRef]

- Kelham S. A water absorption test for concrete. Magazine of Concrete Research. 1988 Jun;40(143):106-10. [CrossRef]

- ACI committee 318. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete. USA: American Concrete Institute; 2019.

- Montgomery DC, Elizabeth A. Peck, G. Geoffrey Vining. Introduction to linear regression analysis. 6th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2021.

- Taylor SC, Hoff WD, Wilson MA, et al. Anomalous water transport properties of Portland and blended cement-based materials. [CrossRef]

| 1 | Designations will be used in plots, M (Mortar) – W/C ratio – specimen number |

| 2 | Properties will be used for correlation with water absorption characteristics |

| Strength Category |

W/C | Contents Unit Weights (kg/m3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | C | S | AE | SSP-104 | ||

| Low | 0.65 | 295 | 454 | 1135 | 5.35 | - |

| Medium | 0.55 | 295 | 535 | 1339 | 5.35 | - |

| High | 0.30 | 165 | 555 | 709 | - | 3.05 |

| Strength | Designation1[1] | Dimensions in mm (L x W x H) |

Age (days) | Mechanical properties[2] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curing | WA | CT | fcm’ (MPa) | Em (GPa) | |||

| Low | M-0.65-1 M-0.65-2 |

152.5 × 100.8 × 50.3 151.6 × 101.7 × 50.2 |

76 145 |

89 157 |

124 174 |

40.52 45.24 |

22.02 21.72 |

| Medium | M-0.55-1 M-0.55-2 |

151.4 × 102.4 × 50.2 152.6 × 102.1 × 50.6 |

78 145 |

102 157 |

281 231 |

61.33 59.21 |

26.08 25.04 |

| High | M-0.30-1 M-0.30-2 |

153.3 × 100.5 × 50.4 151.3 × 100.2 × 50.0 |

32 32 |

42 49 |

56 84 |

83.66 87.97 |

34.82 36.18 |

| Strength | Specimen | Depth Before Deviation (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t = 360 min | t = 1440 min | t = 2880 min | t = 9600 min | ||

| Low | M-0.65-1 M-0.65-2 |

28.33 25.91 |

45.38 43.20 |

51.00 51.68 |

60.09 61.97 |

| Medium | M-0.55-1 M-0.55-2 |

21.11 19.63 |

32.24 32.05 |

39.29 43.01 |

48.68 54.21 |

| High | M-0.30-1 M-0.30-2 |

14.10 14.64 |

21.80 21.20 |

24.54 24.15 |

25.01 25.03 |

| Strength | Specimen | Depth Before Deviation (mm) | Rate of Absorptions (mm/min0.5) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | R2 | I2 | R2 | |||

| Low | M-0.65-1 M-0.65-2 |

49.09 46.50 |

0.988 1.063 |

0.9568 0.9766 |

0.230 0.249 |

0.9043 0.8447 |

| Medium | M-0.55-1 M-0.55-2 |

34.02 47.22 |

0.699 0.733 |

0.9604 0.9867 |

0.197 0.133 |

0.9512 0.5776 |

| High | M-0.30-1 M-0.30-2 |

23.53 23.15 |

0.468 0.418 |

0.9729 0.9560 |

0.021 0.030 |

0.7336 0.7838 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).