Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

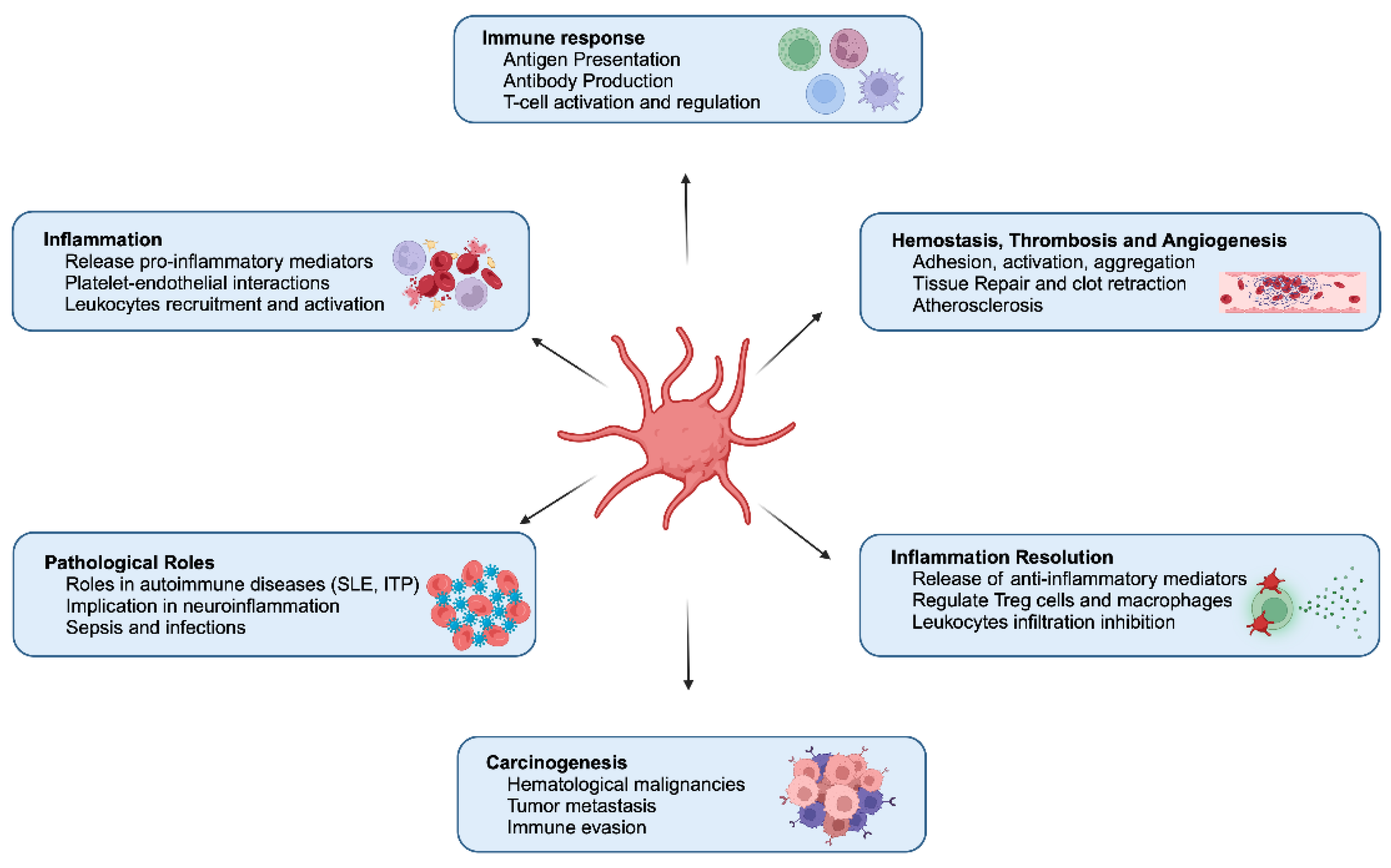

1. Introduction

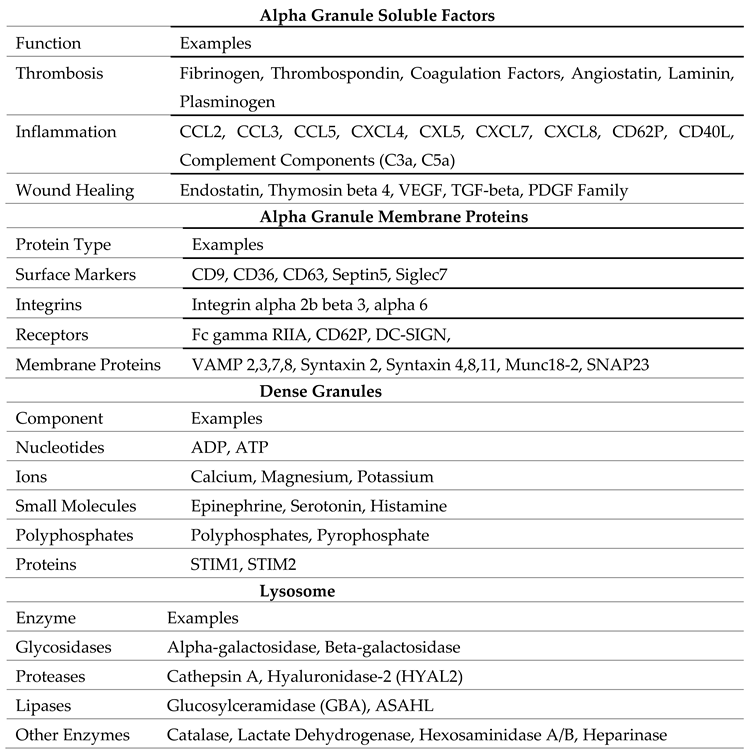

1.1. Alpha Granules

1.2. Dense Granules

1.3. Lysosomes

2. Platelets Activation

3. Synergy of Platelets and Macrophages in Immune Regulation

4. Platelets as Mediator of Innate Immunity

5. Platelets as Adaptive Immune Regulation

6. Platelets in Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia

7. Therapeutic Implications of Platelets

| Molecule | Target | Inhibitory Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin and NSAIDs | Cyclooxygenase1 | Blocks TXA2 formation |

| Clopidogrel | P2Y12 | Irreversibly inhibits ADP receptors |

| Ticagrelor | P2Y12 | Reversibly inhibits ADP receptors |

| Cangrelor | P2Y12 | Reversibly inhibits ADP receptors |

| Prasugrel | P2Y12 | Irreversibly inhibits ADP receptors |

| Tirofiban | GPIIbIIIa | Blocks integrin |

| Eptifibatide | GPIIbIIIa | Blocks integrin |

| Abciximab | GPIIbIIIa | Blocks integrin |

| Vorapaxar | PAR1 | Blocked thrombin receptors |

| Iloprost | PGI2 analogue | Increases platelet cAMP levels, thus acting as an intravenous reversible antiplatelet agent. |

| Cilostazol | PDE3A | Inhibits adenosine cellular uptake |

| Dipyridamole | PDE3/5 | Scavenge peroxy radicals and increase interstitial adenosine levels |

| Revacept | CLEC2/GPVI | Competes with platelet GPVI for binding to collagen |

| Quercetin | PDI | PI3K/Akt inactivation, cAMP elevation |

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VITT | Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia |

| TPO | Thrombopoietin |

| MK | Megakaryocytes |

| MVB | Multivesicular bodies |

| AG | Alpha Granules |

| TGN | Trans-Golgi network |

| VPS33B | Vacuolar Protein Sorting 33B |

| VPS16B | Vacuolar Protein Sorting 16B |

| NBEAL2 | Neurobeachin-like 2 |

| vWF | von Willebrand factor |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| DG | Dense Granules |

| BLOC | Biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex |

| ADP | Adenosine diphosphate |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| VAMP | Vesicle-associated membrane protein |

| SNAP23 | Synaptosome-associated protein 23 |

| STIM | Stromal Interaction Molecule |

| PAR | Protease-Activated Receptor |

| PF4 | Platelet factor 4 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| 5-HIAA | 5-Hydroxy indoleacetic acid |

| PRR | Pattern recognition receptors |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| CLRs | C-type lectin receptors |

| NLRs | NOD-like receptors |

| NET | Neutrophil extracellular traps |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| EPCR | Endothelial protein C receptor |

| IVIG | Intravenous immunoglobulin |

| HIT | Heparin-Induced Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia |

| DAPT | Dual antiplatelet therapy |

References

- Scherlinger, M.; et al. The role of platelets in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023, 23, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maouia, A.; et al. The Immune Nature of Platelets Revisited. Transfus Med Rev 2020, 34, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.T.; Corken, A.; Ware, J. Platelets at the interface of thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer. Blood 2015, 126, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machlus, K.R.; Italiano, J.E. Jr. The incredible journey: From megakaryocyte development to platelet formation. J Cell Biol 2013, 201, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bergmeier, W.; Stefanini, L. Platelet ITAM signaling. Curr Opin Hematol 2013, 20, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Li, W. Sorting machineries: how platelet-dense granules differ from alpha-granules. Biosci Rep 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.H.; et al. alpha-granule biogenesis: from disease to discovery. Platelets 2017, 28, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaumenhaft, R. alpha-granules: a story in the making. Blood 2012, 120, 4908–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharda, A.; Flaumenhaft, R. The life cycle of platelet granules. F1000Res 2018, 7, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.W. Release of alpha-granule contents during platelet activation. Platelets 2022, 33, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golebiewska, E.M.; Poole, A.W. Platelet secretion: From haemostasis to wound healing and beyond. Blood Rev, 2015, 29, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etulain, J.; et al. P-selectin promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation in mice. Blood 2015, 126, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio, A.L.; Boyle, J.A.; Di Pietro, S.M. Mechanism of platelet dense granule biogenesis: study of cargo transport and function of Rab32 and Rab38 in a model system. Blood 2012, 120, 4072–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, S.M.; et al. Platelet dense-granule secretion plays a critical role in thrombosis and subsequent vascular remodeling in atherosclerotic mice. Circulation 2009, 120, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thon, J.N.; Italiano, J.E. Platelets: production, morphology and ultrastructure. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2012, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Heijnen, H.; van der Sluijs, P. Platelet secretory behaviour: as diverse as the granules... or not? J Thromb Haemost 2015, 13, 2141–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendu, F.; Brohard-Bohn, B. The platelet release reaction: granules’ constituents, secretion and functions. Platelets 2001, 12, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italiano, J.E., Jr.; Battinelli, E.M. Selective sorting of alpha-granule proteins. J Thromb Haemost 2009, 7 Suppl 1, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre-Roig, C.; et al. Neutrophils as regulators of cardiovascular inflammation. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020, 17, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, S.S.; et al. Beta(3)-integrin-deficient mice but not P-selectin-deficient mice develop intimal hyperplasia after vascular injury: correlation with leukocyte recruitment to adherent platelets 1 hour after injury. Circulation 2001, 103, 2501–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrell, C.N.; et al. Emerging roles for platelets as immune and inflammatory cells. Blood 2014, 123, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, N.; et al. Platelets at the Crossroads of Pro-Inflammatory and Resolution Pathways during Inflammation. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; et al. Platelets in hemostasis and thrombosis: Novel mechanisms of fibrinogen-independent platelet aggregation and fibronectin-mediated protein wave of hemostasis. J Biomed Res 2015, 29, 437–444. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Role of platelet biomarkers in inflammatory response. Biomark Res 2020, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisucka, J.; et al. Platelets and platelet adhesion support angiogenesis while preventing excessive hemorrhage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006, 103, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sopova, K.; Tatsidou, P.; Stellos, K. Platelets and platelet interaction with progenitor cells in vascular homeostasis and inflammation. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2012, 10, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.; et al. Platelet, a key regulator of innate and adaptive immunity. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1074878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho-Tin-Noe, B. The multifaceted roles of platelets in inflammation and innate immunity. Platelets 2018, 29, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Tin-Noe, B.; Boulaftali, Y.; Camerer, E. Platelets and vascular integrity: how platelets prevent bleeding in inflammation. Blood 2018, 131, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordon, Y. Innate immunity: Platelets on the prowl. Nat Rev Immunol 2018, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nording, H.; Langer, H.F. Complement links platelets to innate immunity. Semin Immunol 2018, 37, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, J.W.; Freedman, J. Platelets and innate immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010, 67, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, R.; Semple, J.W. Platelets as immune-sensing cells. Blood Adv 2016, 1, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, F.W.; Vijayan, K.V.; Rumbaut, R.E. Platelets and Their Interactions with Other Immune Cells. Compr Physiol 2015, 5, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rolfes, V.; et al. Platelets Fuel the Inflammasome Activation of Innate Immune Cells. Cell Rep 2020, 31, 107615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speth, C.; et al. Platelets as immune cells in infectious diseases. Future Microbiol, 2013, 8, 1431–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Hundelshausen, P.; Weber, C. Platelets as immune cells: bridging inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res, 2007, 100, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Y.; et al. The role of platelets in central hubs of inflammation: A literature review. Medicine (Baltimore), 2024, 103, e38115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, S.J.; Conrad, C. Investigating and imaging platelets in inflammation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 2023, 157, 106373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contursi, A.; et al. Platelets as crucial players in the dynamic interplay of inflammation, immunity, and cancer: unveiling new strategies for cancer prevention. Front Pharmacol, 2024, 15, 1520488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayes, J.; et al. The dual role of platelet-innate immune cell interactions in thrombo-inflammation. Res Pract Thromb Haemost, 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vulliamy, P.; Armstrong, P.C. Platelets in Hemostasis, Thrombosis, and Inflammation After Major Trauma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2024, 44, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carestia, A.; et al. Platelets Promote Macrophage Polarization toward Pro-inflammatory Phenotype and Increase Survival of Septic Mice. Cell Rep, 2019, 28, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, J.Y.; et al. Optimizing intrauterine insemination and spontaneous conception in women with unilateral hydrosalpinx or tubal pathology: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2023, 286, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, R.; et al. Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma on M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Giovanni, M.; et al. GPR35 promotes neutrophil recruitment in response to serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA. Cell, 2022, 185, 1103–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revenstorff, J.; et al. Role of S100A8/A9 in Platelet-Neutrophil Complex Formation during Acute Inflammation. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrottmaier, W.C.; et al. Platelet p110beta mediates platelet-leukocyte interaction and curtails bacterial dissemination in pneumococcal pneumonia. Cell Rep, 2022, 41, 111614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; et al. Activated platelet membrane nanovesicles recruit neutrophils to exert the antitumor efficiency. Front Chem, 2022, 10, 955995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.R.; et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med, 2007, 13, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Stoppelaar, S.F.; et al. The role of platelet MyD88 in host response during gram-negative sepsis. J Thromb Haemost, 2015, 13, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; et al. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 receptor is expressed in platelets and enhances platelet activation and thrombosis. Circulation, 2015, 131, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.T.; McIntyre, T.M. Lipopolysaccharide signaling without a nucleus: kinase cascades stimulate platelet shedding of proinflammatory IL-1beta-rich microparticles. J Immunol, 2011, 186, 5489–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggrey, A.A.; et al. Platelet induction of the acute-phase response is protective in murine experimental cerebral malaria. J Immunol, 2013, 190, 4685–4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, M.M.; et al. Escaping the nuclear confines: signal-dependent pre-mRNA splicing in anucleate platelets. Cell, 2005, 122, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boylan, B.; et al. Identification of FcgammaRIIa as the ITAM-bearing receptor mediating alphaIIbbeta3 outside-in integrin signaling in human platelets. Blood, 2008, 112, 2780–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, H.; et al. Cooperative integrin/ITAM signaling in platelets enhances thrombus formation in vitro and in vivo. Blood, 2013, 121, 1858–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, M.; et al. Amplification of bacteria-induced platelet activation is triggered by FcgammaRIIA, integrin alphaIIbbeta3, and platelet factor 4. Blood, 2014, 123, 3166–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boilard, E.; et al. Influenza virus H1N1 activates platelets through FcgammaRIIA signaling and thrombin generation. Blood, 2014, 123, 2854–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karas, S.P.; Rosse, W.F.; Kurlander, R.J. Characterization of the IgG-Fc receptor on human platelets. Blood, 1982, 60, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; et al. Bacillus anthracis peptidoglycan activates human platelets through FcgammaRII and complement. Blood, 2013, 122, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benezech, C.; et al. CLEC-2 is required for development and maintenance of lymph nodes. Blood, 2014, 123, 3200–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitchcock, J.R.; et al. Inflammation drives thrombosis after Salmonella infection via CLEC-2 on platelets. J Clin Invest, 2015, 125, 4429–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hawas, R.; et al. Munc18b/STXBP2 is required for platelet secretion. Blood, 2012, 120, 2493–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; et al. STING activation in platelets aggravates septic thrombosis by enhancing platelet activation and granule secretion. Immunity, 2023, 56, 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; et al. The 17beta-estradiol induced upregulation of the adhesion G-protein coupled receptor (ADGRG7) is modulated by ESRalpha and SP1 complex. Biol Open 2019, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagirath, V.C.; Dwivedi, D.J.; Liaw, P.C. Comparison of the Proinflammatory and Procoagulant Properties of Nuclear, Mitochondrial, and Bacterial DNA. Shock, 2015, 44, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, L.H.; et al. Platelets release mitochondria serving as substrate for bactericidal group IIA-secreted phospholipase A2 to promote inflammation. Blood, 2014, 124, 2173–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melki, I.; et al. Platelets release mitochondrial antigens in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhm, F.; Boilard, E.; Machlus, K.R. Platelet Extracellular Vesicles: Beyond the Blood. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2021, 41, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavukcuoglu, Z.; et al. Platelet-derived extracellular vesicles induced through different activation pathways drive melanoma progression by functional and transcriptional changes. Cell Commun Signal, 2024, 22, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Itagaki, K.; Hauser, C.J. Mitochondrial DNA is released by shock and activates neutrophils via p38 map kinase. Shock, 2010, 34, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nish, S.; Medzhitov, R. Host defense pathways: role of redundancy and compensation in infectious disease phenotypes. Immunity, 2011, 34, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, L.; Pekayvaz, K.; Massberg, S. Platelets: Orchestrators of immunity in host defense and beyond. Immunity, 2024, 57, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.A.; Wuescher, L.M.; Worth, R.G. Platelets: essential components of the immune system. Curr Trends Immunol, 2015, 16, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hirosue, S.; Dubrot, J. Modes of Antigen Presentation by Lymph Node Stromal Cells and Their Immunological Implications. Front Immunol, 2015, 6, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukiji, N.; Suzuki-Inoue, K. Impact of Hemostasis on the Lymphatic System in Development and Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2023, 43, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, P.; et al. Platelet P-selectin initiates cross-presentation and dendritic cell differentiation in blood monocytes. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eaaz1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanujam, M.; et al. Phoenix from the flames: Rediscovering the role of the CD40-CD40L pathway in systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Autoimmun Rev, 2020, 19, 102668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, P.R.; et al. Platelets mediate lymphovenous hemostasis to maintain blood-lymphatic separation throughout life. J Clin Invest, 2014, 124, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognasse, F.; et al. Human platelets can activate peripheral blood B cells and increase production of immunoglobulins. Exp Hematol, 2007, 35, 1376–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greinacher, A.; et al. Pathogenesis of vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT). Semin Hematol, 2022, 59, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonca, S.A.; et al. Adenoviral vector vaccine platforms in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. NPJ Vaccines, 2021, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roytenberg, R.; Garcia-Sastre, A.; Li, W. Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia: what do we know hitherto? Front Med (Lausanne), 2023, 10, 1155727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, T.; Schwarz, S.L.; Handtke, S. Platelet size as a mirror for the immune response after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Thromb Haemost, 2022, 20, 818–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.; et al. Platelet-neutrophil interaction in COVID-19 and vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1186000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, S.R.; et al. Inflammation and Platelet Activation After COVID-19 Vaccines - Possible Mechanisms Behind Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombocytopenia and Thrombosis. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 779453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, J.M.; et al. European stroke organization interim expert opinion on cerebral venous thrombosis occurring after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Eur Stroke J 2021, 6, CXVI–CXXI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gresele, P.; et al. Management of cerebral and splanchnic vein thrombosis associated with thrombocytopenia in subjects previously vaccinated with Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca): a position statement from the Italian Society for the Study of Haemostasis and Thrombosis (SISET). Blood Transfus 2021, 19, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, B.F.; et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. S Afr Med J 2021, 111, 535–537. [Google Scholar]

- Tutwiler, V.; et al. Platelet transactivation by monocytes promotes thrombosis in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood.

- Stolla, M.; Kapur, R.; Semple, J.W. New Emerging Developments of Platelets in Transfusion Medicine. Transfus Med Rev 2020, 34, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, C.H.; DomBourian, M.G.; Millward, P.A. Platelet transfusion for patients with cancer. Cancer Control 2015, 22, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; et al. Clinical application of platelet rich plasma to promote healing of open hand injury with skin defect. Regen Ther 2024, 26, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meijden, P.E.J.; Heemskerk, J.W.M. Platelet biology and functions: new concepts and clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019, 16, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.S.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Aspirin Dosing in Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 1981–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagna, G.; et al. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy with Parenteral P2Y(12) Inhibitors: Rationale, Evidence, and Future Directions. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2023, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen, S.; et al. Aspirin therapy in primary cardiovascular disease prevention: a position paper of the European Society of Cardiology working group on thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014, 64, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadyen, J.D.; Schaff, M.; Peter, K. Current and future antiplatelet therapies: emphasis on preserving haemostasis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018, 15, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olie, R.H.; van der Meijden, P.E.J.; Cate, H.T. The coagulation system in atherothrombosis: Implications for new therapeutic strategies. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2018, 2, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrono, C.; et al. Antiplatelet Agents for the Treatment and Prevention of Coronary Atherothrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017, 70, 1760–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, P.C.; et al. In the presence of strong P2Y12 receptor blockade, aspirin provides little additional inhibition of platelet aggregation. J Thromb Haemost 2011, 9, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, M.G.; Vancura, A.; Wurdinger, T. Platelet RNA as a circulating biomarker trove for cancer diagnostics. J Thromb Haemost 2017, 15, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.Z.; et al. Platelet activation, and antiplatelet targets and agents: current and novel strategies. Drugs 2008, 68, 1647–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duley, L.; et al. Antiplatelet agents for preventing pre-eclampsia and its complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safouris, A.; Magoufis, G.; Tsivgoulis, G. Emerging agents for the treatment and prevention of stroke: progress in clinical trials. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2021, 30, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelbenegger, G.; Jilma, B. Clinical pharmacology of antiplatelet drugs. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2022, 15, 1177–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|---|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).