Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Samples

2.2. BRSV Vaccines

2.3. Extraction of BRSV RNA

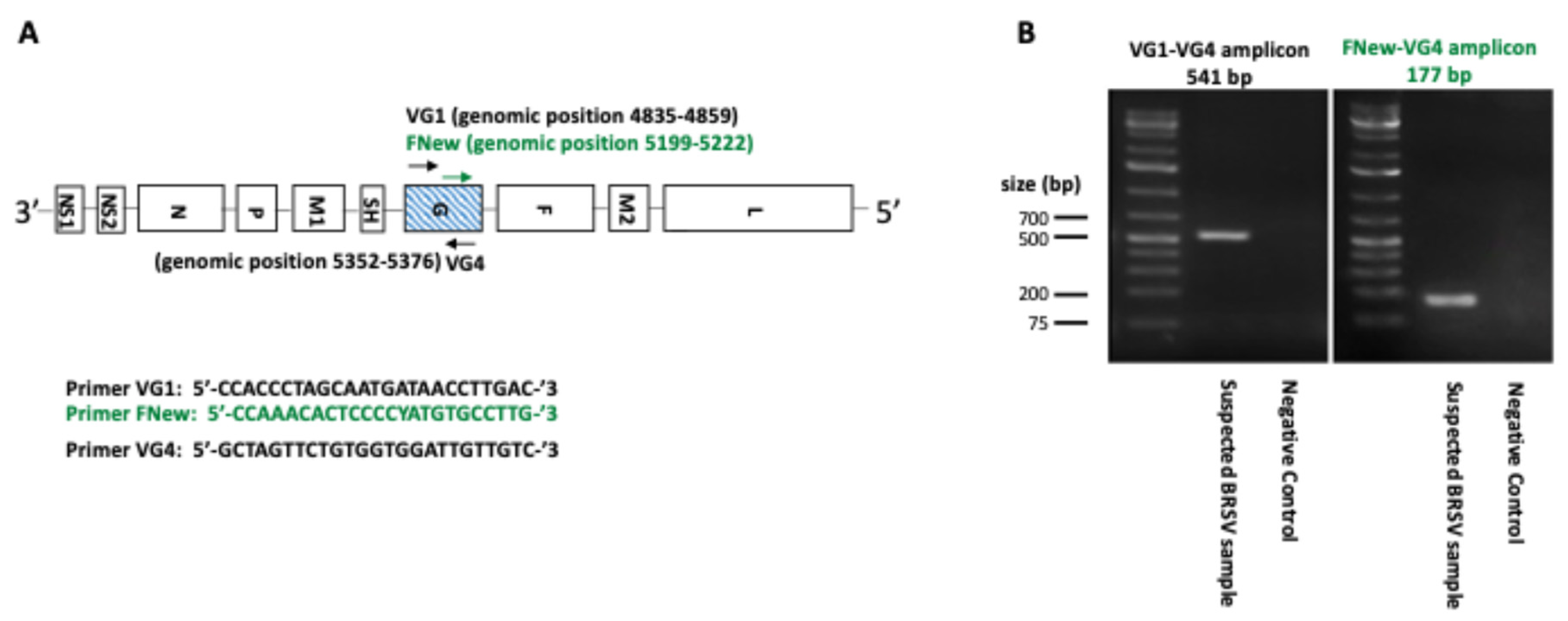

2.4. RT-PCR Targeting the BRSV G Gene

2.5. DNA Purification and Sequencing of BRSV G Gene

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.7. Amino Acid Sequences Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Collection

3.2. Sequencing Results

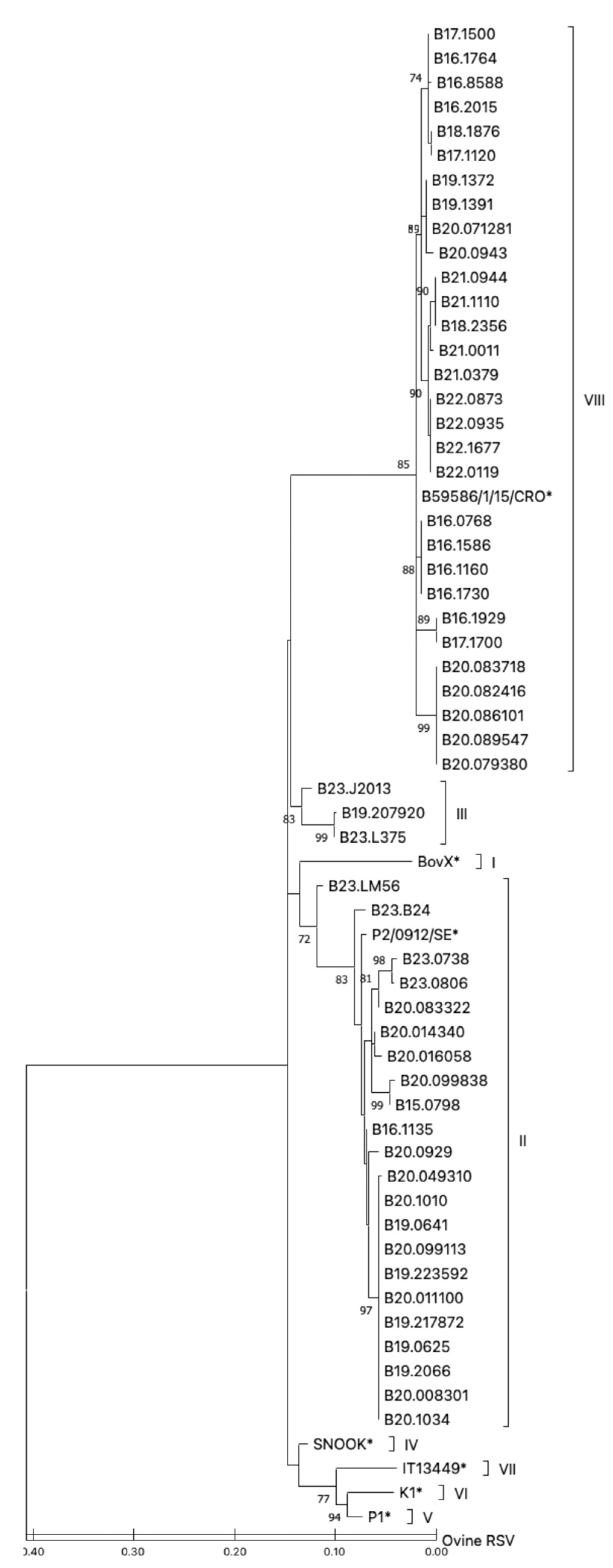

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

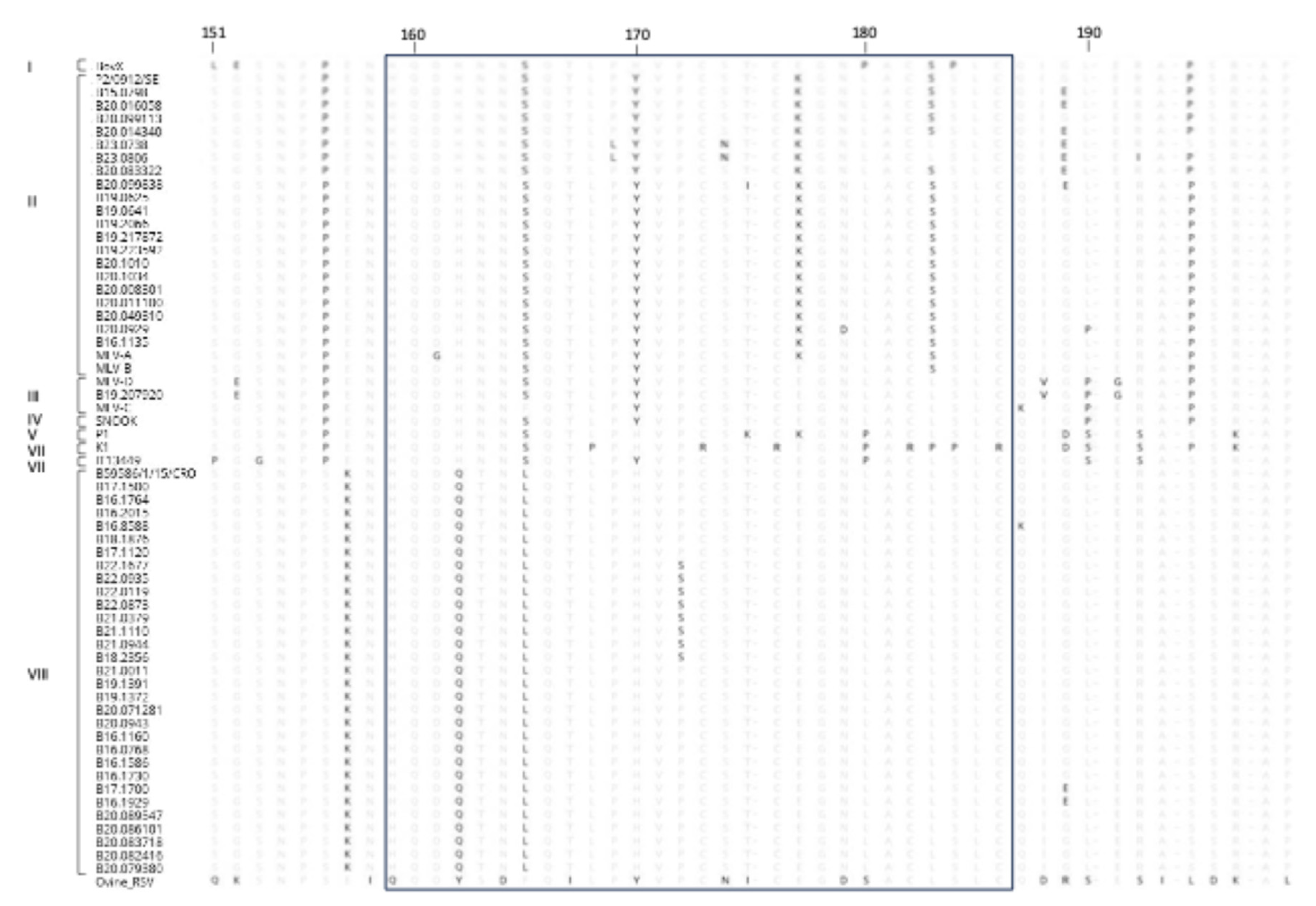

3.4. Amino Acid Sequences Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lillie, L. E. The Bovine Respiratory Disease Complex. Can. Vet. J. 1974, 15, 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Stott, E. J.; Taylor, G. Archives of Virology Respiratory Syncytial Virus Brief Review. Arch. Virol. 1985, 84, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valarcher, J.; Taylor, G.; Valarcher, J.; Taylor, G. Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection To Cite This Version : HAL Id : Hal-00902838 Review Article Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. 2007, 38 (2), 153–180.

- Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Auinger P, Griffin MR, Poehling KA, Erdman D, Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, S. P. Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Young Children. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarcher, J.-F.; Schelcher, F.; Bourhy, H. Evolution of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 10714–10728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doggett, J. E.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Gallop, R. G. C. A Study of an Inhibitor in Bovine Serum Active against Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Arch. Gesamte Virusforsch. 1968, 23, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, C. R.; Kiesel, G. K. Serological Evidence for the Association of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus with Respiratory Tract Disease in Alabama Cattle. Infect. Immun. 1974, 10, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaegashi, G.; Seimiya, Y. M.; Seki, Y.; Tsunemitsu, H. Genetic and Antigenic Analyses of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus Detected in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2005, 67, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, K. E.; Barnes, T. S.; Morton, J. M.; Gravel, J. L.; Commins, M. A.; Horwood, P. F.; Ambrose, R. C.; Clements, A. C. A.; Mahony, T. J. Associations between Exposure to Viruses and Bovine Respiratory Disease in Australian Feedlot Cattle. Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 127, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. A. Effects of Feedlot Disease on Economics, Production and Carcass Value. Am. Assoc. Bov. Pract. Proc. 2000, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento-Silva, R. E.; Nakamura-Lopez, Y.; Vaughan, G. Epidemiology, Molecular Epidemiology and Evolution of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Viruses 2012, 4, 3452–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentova, V.; Antonis, A. F. G.; Kovarcik, K. Restriction Enzyme Analysis of RT-PCR Amplicons as a Rapid Method for Detection of Genetic Diversity among Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus Isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 2005, 108, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klem, T. B.; Rimstad, E.; Stokstad, M. Occurrence and Phylogenetic Analysis of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Outbreaks of Respiratory Disease in Norway. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotti, L.; Giammarioli, M.; Rosati, S. Genetic Characterization of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus Strains Isolated in Italy: Evidence for the Circulation of New Divergent Clades. J. Vet. Diagnostic Investig. 2018, 30, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krešić, N.; Bedeković, T.; Brnić, D.; Šimić, I.; Lojkić, I.; Turk, N. Genetic Analysis of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Croatia. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 58, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumagai, A.; Kawauchi, K.; Andoh, K.; Hatama, S. Sequence and Unique Phylogeny of G Genes of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Viruses Circulating in Japan. J. Vet. Diagnostic Investig. 2021, 33, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Agri-environmental indicator-livestock patterns.

- Boxus, M.; Letellier, C.; Kerkhofs, P. Real Time RT-PCR for the Detection and Quantitation of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Virol. Methods 2005, 125, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langedijk, J. P. M.; Schaaper, W. M. M.; Meloen, R. H.; Van Oirschot, J. T. Proposed Three-Dimensional Model for the Attachment Protein G of Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1996, 77, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leme, R. A.; Dall Agnol, A. M.; Balbo, L. C.; Pereira, F. L.; Possatti, F.; Alfieri, A. F.; Alfieri, A. A. Molecular Characterization of Brazilian Wild-Type Strains of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus Reveals Genetic Diversity and a Putative New Subgroup of the Virus. Vet. Q. 2020, 40, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidokhti, M. R. M.; Tråvén, M.; Ohlson, A.; Zarnegar, B.; Baule, C.; Belák, S.; Alenius, S.; Liu, L. Phylogenetic Analysis of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Viruses from Recent Outbreaks in Feedlot and Dairy Cattle Herds. Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giammarioli, M.; Mangili, P.; Nanni, A.; Pierini, I.; Petrini, S.; Pirani, S.; Gobbi, P.; De Mia, G. M. Highly Pathogenic Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus Variant in a Dairy Herd in Italy. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 6, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timurkan, M. O.; Aydin, H.; Sait, A. Identification and Molecular Characterisation of Bovine Parainfluenza Virus-3 and Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus-First Report from Turkey. J. Vet. Res. 2019, 63, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, S.; Yao, X.; Yang, Y.; Niu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Pan, R.; Jiang, X.; Xiaobo, S.; Qiao, X.; Guan, X.; Xu, Y. Isolation, Identification, and Phylogenetic Analysis of Subgroup III Strain of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus Contributed to Outbreak of Acute Respiratory Disease among Cattle in Northeast China. Virulence 2021, 12, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langedijk, J. P.; Meloen, R. H.; Taylor, G.; Furze, J. M.; van Oirschot, J. T. Antigenic Structure of the Central Conserved Region of Protein G of Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 4055–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subgroup | Isolate name | Accession number | Year/month | Tissue | Age (months) | Vaccination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | B15.0798 | PP538078 | 2015/11 | Lung | 6 | No |

| II | B16.1135 | PP538080 | 2016/01 | Lung | 2.5 | Yesb |

| II | B19.2066 | PP538098 | 2019/03 | Lung | 18 | No |

| II | B19.0641 | PP538095 | 2019/12 | Lung | 6 | Yesb |

| II | B19.0625 | PP538094 | 2019/12 | Lung | 5 | NK |

| II | B19.217872 | PP538100 | 2019/11 | Lung | 16 | Yesb |

| II | B19.223592 | PP538101 | 2019/12 | Lung | 8 | No |

| II | B20.0929 | PP538102 | 2020/02 | Lung | 4 | NK |

| II | B20.1010 | PP538104 | 2020/02 | Lung | 7 | Yesb |

| II | B20.1034 | PP538105 | 2020/02 | Lung | 6 | No |

| II | B20.008301 | PP538106 | 2020/01 | Lung | 1 | Yesa |

| II | B20.016058 | PP538109 | 2020/01 | Lung | 4 | Yesb |

| II | B20.011100 | PP538107 | 2020/01 | Lung | 4 | No |

| II | B20.014340 | PP538108 | 2020/01 | Lung | 1.5 | Yesb |

| II | B20.049310 | PP538110 | 2020/03 | Lung | 4 | No |

| II | B20.083322 | PP538114 | 2020/04 | Lung | 1.5 | Yesb |

| II | B20.099113 | PP538118 | 2020/05 | Lung | 1.5 | Yesb |

| II | B20.099838 | PP538119 | 2020/05 | Lung | 3 | No |

| II | B23.0738 | PP538128 | 2023/02 | Lung | 8 | NK |

| II | B23.0806 | PP538129 | 2023/02 | Lung | 19 | Yesb |

| II | MLV-A | PP538130 | 2021/04 | Vaccine | ||

| II | MLV-B | PP538132 | 2021/04 | Vaccine | ||

| III | B19.207920 | PP538099 | 2019/11 | Lung | 7 | Yesb |

| III | MLV-C | PP538131 | 2021/04 | Vaccine | ||

| III | MLV-D | PP538133 | 2021/04 | Vaccine | ||

| VIII | B16.1160 | PP538081 | 2016/01 | Lung | 5 | NK |

| VIII | B16.1586 | PP538083 | 2016/03 | Lung | 3 | No |

| VIII | B16.1730 | PP538084 | 2016/04 | Lung | 2 | NK |

| VIII | B16.1764 | PP538085 | 2016/04 | Lung | 9 | No |

| VIII | B16.1929 | PP538086 | 2016/05 | Lung | 2 | No |

| VIII | B16.8588 | PP538088 | 2016/05 | Lung | 3 | Yesb |

| VIII | B16.2015 | PP538087 | 2016/05 | Lung | 3 | No |

| VIII | B16.0768 | PP538079 | 2016/11 | Lung | 4 | NK |

| VIII | B17.1500 | PP538090 | 2017/02 | Lung | 9.5 | Yesb |

| VIII | B17.1700 | PP538091 | 2017/03 | Lung | 3 | No |

| VIII | B17.1120 | PP538089 | 2017/12 | Lung | 5.5 | No |

| VIII | B18.1876 | PP538092 | 2018/04 | Lung | 4 | Yesb |

| VIII | B18.2356 | PP538093 | 2018/06 | Lung | 9 | No |

| VIII | B19.1372 | PP538096 | 2019/01 | Lung | 14 | No |

| VIII | B19.1391 | PP538097 | 2019/01 | Lung | 6 | NK |

| VIII | B20.0943 | PP538103 | 2020/02 | Lung | 1 | No |

| VIII | B20.071281 | PP538111 | 2020/04 | Lung | ||

| VIII | B20.079380 | PP538112 | 2020/04 | Nasal swab | 2 | Yesa |

| VIII | B20.082416 | PP538113 | 2020/04 | Nasal swab | 4.5 | No |

| VIII | B20.083718 | PP538115 | 2020/04 | Lung | 0.5 | NK |

| VIII | B20.086101 | PP538116 | 2020/04 | Nasal swab | ||

| VIII | B20.089547 | PP538117 | 2020/05 | Lung | 5 | Yesa |

| VIII | B21.0944 | PP538122 | 2021/02 | Lung | 4 | Yesa |

| VIII | B21.1110 | PP538123 | 2021/03 | Lung | 4.5 | Yesa |

| VIII | B21.0011 | PP538120 | 2021/09 | Lung | 8 | Yesa |

| VIII | B21.0379 | PP538121 | 2021/11 | Lung | 8 | Yesb |

| VIII | B22.0873 | PP538125 | 2022/02 | Lung | 2 | No |

| VIII | B22.0935 | PP538126 | 2022/02 | Lung | 1.5 | No |

| VIII | B22.1677 | PP538127 | 2022/09 | Lung | 12 | Yesb |

| VIII | B22.0119 | PP538124 | 2022/09 | Lung | 8 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).