Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the effects of therapeutic exercise in Postoperative Cardiac Surgery Patients in Intensive Care Unit (ICU)?

- What characteristics are associated with the prescription of ET in Postoperative Cardiac Surgery Patients In ICU

- What benefits has scientific evidence documented regarding therapeutic exercise in this population?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

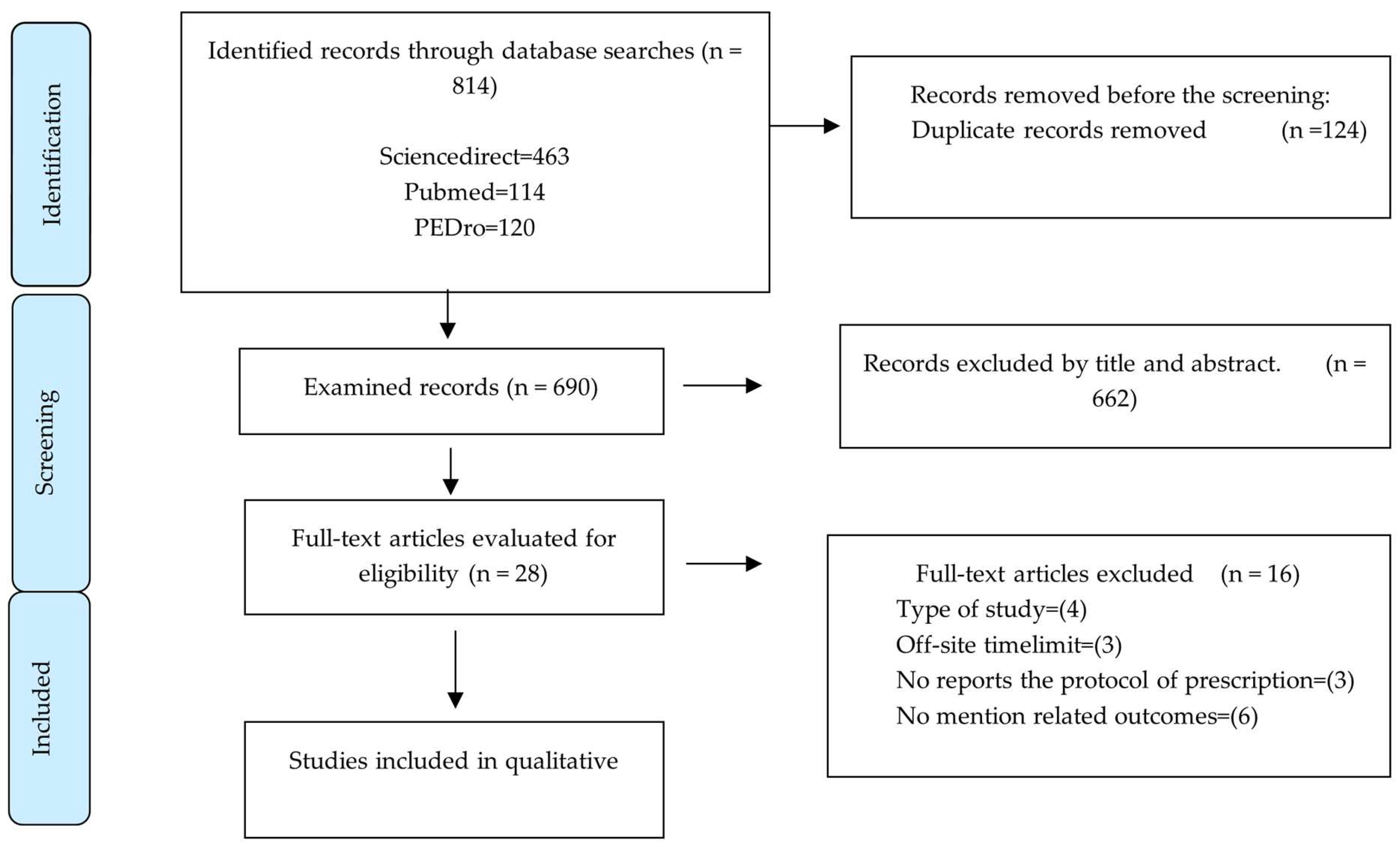

2.5. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.6. Data Charting Process and Data Items

2.7. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

| Duration | Frequency | Intensity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Exercise mode/type | Session (Minutes) | Program (Days) |

Sessions/week | IPE–aerobic capacity–MHR | MRC (Strength |

| Ribeiro BC et al. [13]. | RE–LLE–SEB–CELL–SC–PG-VR | 20 min | 1–3 days | NR | 20% MHR, moderate-high (modified Borg 4–5) | NR |

| Gama Lordello et al. [14]. | ULE–CELL+CEUL–SU–SC-PG | 10 min | 2–12 days | 2 times a day | Number of steps (pedometer) | NR |

| Shirvani et al. [15]. | SEB–PG | 15 min | 2–6 days | 2 times a day | Pulse oximetry and 20 % HR, Neecham confusion scale | NR |

| Moreira et al. [16]. | RE–BA–ULE–LLE–PG –CS | 10–30 min | 1–6 days | 2–3 times a day | 6MW; Borg modified scale; hemodynamic values: blood pressure, heart rate, and pain (4 MET of intensity) | NR |

| Han et al. [17]. | RE–TSS–SEB–SC–SU– PG | NR | 2–7 days | 2 times a day | IEP (Borg 3–4/10) - Barthel | NR |

| Cui et al. [18] | TBC–SU–SC–PG | 10–20 min | 3 days | 2–3 times a day | MHR, VO2max, (%MHR = 0.64 × %VO2max + 37; MHR = 205.8−0.685 × age; HRR = MHR−HRR; X% APMHR = HRR × X% + HRR). Everyday VO2max increased by 10% |

NR |

| Esmealy et al. [19]. | RE-ULE-LLE-SEB -SC-SU-PG | 15 min | 2 days | 2 times a day | Arterial blood gas (PaO2, PaCO2, blood pH), SpO2 | NR |

| Bano et al.[20] | ULE-LLE-CELL-PG, RE+CPAP | 20–30 min | 2–4 days | 1- 2 times a day | Mild IPE (modified Borg 3), HR 20 L/min, 6MW, 1 minute sit and stand test (measure lower limbs strength) | NR |

| Allahbakhshian et al.[21]. | RE-ULE-LLE-SEB - SC-SU-PG | 15 min | 0–1 day | 2 times a day | MMSE, VAS | NR |

| Tsuchikawa et al.[22]. | RE-ULE-LLE-PST-SEB-SU-PG | NR | 1–10 days | 2 times a day | 6MW | NR |

| Kenji Nawa et al. [23]. | ULE–LLE | 30 min | 4–8 days | 2 times a day | Dynamometry(force), Perme mobility scale (functionality), spirometry (pulmonary function), PIM, and PEM (respiratory muscle strength). | NR |

| Cordeiro et al. [24]. | TBC-PG | NR | 2–8 days | NR | MRC strength, FIM, 6MW (prepost) | NR |

| Authors | Test or measurement tool | Quality of life | Reduction of ICU and hospital stay | Complications | Functional and aerobic capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribeiro BC et al. [13]. | Modified Borg Scale | NR | Reduction of hospital stay, P < 0.05 (0.03). | No complications. | No Changes |

| Gama Lordello et al. [14]. | Podometer | Self-reports evidenced a significant improvement in the motivation of the control group. | No significant changes. | NR | The number of steps measured after the intervention in the intervention group was 1,126 versus 972 in the control group; the use of a cycloergometer did not show greater efficiency than other interventions at the time of comparison. |

| Shirvani et al. [15]. | Neecham confusion scale | NR | There were no significant differences in terms of hospitalization days. | No complications. | Planned EM may reduce the incidence of postoperative delirium. |

| Moreira et al. [16]. | 6MW , Borg scale , : PA, FC ,NRS, SF-36V2 | SF-36V2, there was a percentage increase in all domains, numerical pain scale. | There were no significant differences in terms of hospitalization days. | NR | 6-MW, there was improvement at the end of the study. |

| Han et al. [17]. | Barthel Test | Barthel index was significantly higher in the IGR group. | Postoperative hospital stay was statistically shorter for the IGR group. | Both the SGR and the IGR groups had significantly fewer complications. | NR |

| Cui et al. [18] | Arterial Blood gas analysis and Distance of walking (patient’s self-assessment and the experiences of rehabilitation therapists) Post-traumatic stress disorder score |

NR | PLOS in the PEA group was shorter than that in the Control group (9.04 ± 3.08 versus 10.09 ± 3.32 days. | Elderly patients subject to CABG had a higher risk of complications. | There were favorable and significant associations between PEA and clinical results such as PLOS, walking distance and psychological consequences |

| Esmealy et al. [19]. | Arterial blood gases and oxygen saturation | NR | NR | No adverse effects. | There was a significant increase of SpO2 over time (P = 0.001); PaO2 and its interaction with time had statistically significant results (P = 0.001). PaCO2 value decreased. |

| Bano et al. [20]. | Arterial blood gases | NR | ICU and hospital stays were considerably lower in the intervention group (P = 0.001). | NR | Walk distance and lower limb strength of the intervention group were statistically significant (P = 0.001). |

| Allahbakhshian et al. [21]. | Borg scale, MMSE, VAS | Improvement in pain sensation The intervention group had significantly less postoperative cognitive dysfunction. |

There was a significant difference in the length of hospital stay (P = 0.01) between groups. | NR | NR |

| Tsuchikawa et al. [22]. | 6 MW, EuroSCORE II | The estimated future risk decreased if there was an early onset of ambulation (EuroSCORE II). | NR | The Mortality rate was lower in the group that started ambulation before 3 days. | Patients in Group E showed a greater walk distance according to the 6-minute walk (368.9 m) The estimated future risk of adverse events was found to be increased day-by-day during the delay until initial ambulation. |

| Kenji Nawa et al. [23]. | 6MW - Perme Mobility Scale | NR | Perme score on days 2 and 3 was associated with hospital stay (P < 0.001). | No complications. | A 4.6-increase in Day 3 Perme Score reduced ICU stay to a day. |

| Cordeiro et al. [24]. | FIM | NR | MV time, ICU stay, and hospital stay were significantly better in the EM group (P = 0.001). | NR | Functional factors, such as functional independence and walk distance, were significantly higher in the group with EM (P = 0.001). |

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Las enfermedades del corazón siguen siendo la principal causa de muerte en las Américas - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 3]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/29-9-2021-enfermedades-corazon-siguen-siendo-principal-causa-muerte-americas.

- Lozada-Ramos, H.; Daza-Arana, J.E.; González, M.Z.; Gallo, L.F.M.; Lanas, F. Risk factors for in-hospital mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting in Colombia. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 63, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Rodríguez-Scarpetta, M.; Sepúlveda-Tobón, A.M.; E Daza-Arana, J.; Lozada-Ramos, H.; A Álzate-Sánchez, R. Central Oxygen Venous Saturation and Mortality in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.; Roddy, L.; Giuliano, K.K. Management of patient tubes and lines during early mobility in the intensive care unit. Hum. Factors Heal. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, M.; Nery, R.M.; de Lima, J.B.; Buhler, R.P.; da Silveira, A.D.; Stein, R. Effects of Different Rehabilitation Protocols in Inpatient Cardiac Rehabilitation After Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabilitation Prev. 2019, 39, E19–E25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santilli, G.; Mangone, M.; Agostini, F.; Paoloni, M.; Bernetti, A.; Diko, A.; Tognolo, L.; Coraci, D.; Vigevano, F.; Vetrano, M.; et al. Evaluation of Rehabilitation Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Neurological Health Conditions Using a Machine Learning Approach. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A McDonagh, T.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. Corrigendum to: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 42, 4901–4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani Correction to: 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2023, 148, E148–E148. [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G. Prescripción de ejercicio para personas con enfermedades cardiovasculares y pulmonares. In: Wolters Kluwer Español, editor. Manual ACSM para la Valoración y Prescripción del Ejercicio. 4th ed. 2021. p. 227–31.

- Pelliccia, A.; Sharma, S.; Gati, S.; Bäck, M.; Börjesson, M.; Caselli, S.; Collet, J.-P.; Corrado, D.; Drezner, J.A.; Halle, M.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 17–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäck, M.; Öberg, B.; Krevers, B. Important aspects in relation to patients’ attendance at exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation – facilitators, barriers and physiotherapist’s role: a qualitative study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B.C.; da Poça, J.J.G.; Rocha, A.M.C.; da Cunha, C.N.S.; Cunha, K.d.C.; Falcão, L.F.M.; Torres, D.d.C.; Rocha, L.S.d.O.; Rocha, R.S.B. Different physiotherapy protocols after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Res. Int. 2020, 26, e1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lordello, G.G.G.; Gama, G.G.G.; Rosier, G.L.; Viana, P.A.D.d.C.; Correia, L.C.; Ritt, L.E.F. Effects of cycle ergometer use in early mobilization following cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabilitation 2020, 34, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, F.; Naji, S.A.; Davari, E.; Sedighi, M. Early mobilization reduces delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Asian Cardiovasc. Thorac. Ann. 2020, 28, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.M.A.; Grilo, E.N. Quality of life after coronary artery bypass graft surgery - results of cardiac rehabilitation programme. J. Exerc. Rehabilitation 2019, 15, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Yu, H.; Xie, F.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Shao, B.; Liu, J.; et al. Effects of early rehabilitation on functional outcomes in patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J. Int. Med Res. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Li, N.; Gao, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhuang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Tan, Q. Precision implementation of early ambulation in elderly patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized-controlled clinical trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmealy, L.; Allahbakhshian, A.; Gholizadeh, L.; Khalili, A.F.; Sarbakhsh, P. Effects of early mobilization on pulmonary parameters and complications post coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2022, 69, 151653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bano, A.; Aftab, A.; Sahar, W.; Haider, Z.; Rashed, M.I.; Shabbir, H.M. Combined Effects of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure and Cycle Ergometer in Early Rehabilitation of Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery Patients. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2023, 33, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahbakhshian, A.; Khalili, A.F.; Gholizadeh, L.; Esmealy, L. Comparison of early mobilization protocols on postoperative cognitive dysfunction, pain, and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2023, 73, 151731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchikawa, Y.; Tokuda, Y.; Ito, H.; Shimizu, M.; Tanaka, S.; Nishida, K.; Takagi, D.; Fukuta, A.; Takeda, N.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. Impact of Early Ambulation on the Prognosis of Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Patients. Circ. J. 2023, 87, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawa, R.K.; Dos Santos, T.D.; Real, A.A.; Matheus, S.C.; Ximenes, M.T.; Cardoso, D.M.; Albuquerque, I.M. Relationship between Perme ICU Mobility Score and length of stay in patients after cardiac surgery. Colomb. Medica 2022, 53, e2005179–e2005179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, A.L.L.; Lima, A.D.S.; De Oliveira, C.M.; De Sa, J.P.; Guimaraes, A.R.F. Impact of early mobilization on clinical and functional outcomes in patients submitted to coronary artery bypass grafting. 2022, 12, 67–72.

- Alvarez CV, Obando LMG, Rendón CLA, López AL. Factores de riesgo cardiovascular y variables asociadas en personas de 20 a 79 años en Manizales, Colombia. Univ Salud. 2015 May 26;17(1):32–46.

- Félix-Redondo FJ, Baena-Díez JM, Grau M, Tormo M ángeles, Fernández-Bergés D. Prevalencia de obesidad y riesgo cardiovascular asociado en la población general de un área de salud de Extremadura. Estudio Hermex. Endocrinología y Nutrición. 2012 Mar 1;59(3):160–8.

- Aggarwal, R.; Yeh, R.W.; Maddox, K.E.J.; Wadhera, R.K. Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence, Treatment, and Control in US Adults Aged 20 to 44 Years, 2009 to March 2020. JAMA 2023, 329, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, S.J.; Mckenzie, M.J.; Joseph, L.J.; Ivey, F.M.; Macko, R.F.; Hafer-Macko, C.E.; Ryan, A.S. Reduced Skeletal Muscle Capillarization and Glucose Intolerance. Microcirculation 2009, 16, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, W.; Arif, R.; Kremer, J.; Al Maisary, S.; Verch, M.; Tochtermann, U.; Karck, M.; Meyer, A.L.; Warnecke, G. Temporary circulatory support with surgically implanted microaxial pumps in postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock following coronary artery bypass surgery. JTCVS Open 2023, 15, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirkes, S.M.; Kozlowski, C. Early Mobility in the Intensive Care Unit: Evidence, Barriers, and Future Directions. Crit. Care Nurse 2019, 39, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Flores M, Herrera-Melo J, Diaz X, Cigarroa I, Concha-Cisternas Y. Fuerza de prensión manual y calidad de vida en personas mayores autovalentes. Rev cuba med mil. 2021;e1328–e1328. Epub 01-Sep-2021. ISSN 1561-3046.

- Allen, C.; Glasziou, P.; Del Mar, C. Bed rest: a potentially harmful treatment needing more careful evaluation. Lancet 1999, 354, 1229–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crapo RO, Casaburi R, Coates AL, Enright PL, MacIntyre NR, McKay RT, et al. ATS Statement: Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 166, 111-117.

- Scherr, J.; Wolfarth, B.; Christle, J.W.; Pressler, A.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Halle, M. Associations between Borg’s rating of perceived exertion and physiological measures of exercise intensity. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 113, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero E, Guerassimova I, Lobato SD. Disnea aguda. Medicine - Programa de Formación Médica Continuada Acreditado. 2019 Oct 1;12(88):5147–54.

- Bragança, R.D.; Ravetti, C.G.; Barreto, L.; Ataíde, T.B.L.S.; Carneiro, R.M.; Teixeira, A.L.; Nobre, V. Use of handgrip dynamometry for diagnosis and prognosis assessment of intensive care unit acquired weakness: A prospective study. Hear. Lung 2019, 48, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, G.; Tzikos, G.; Menni, A.-E.; Chatziantoniou, G.; Vouchara, A.; Fyntanidou, B.; Grosomanidis, V.; Kotzampassi, K. Endothelial Damage and Muscle Wasting in Cardiac Surgery Patients. Cureus 2022, 14, e30534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Romero UDJ, Gochicoa-Rangel L, Guerrero-Zúñiga S, Cid-Juárez S, Silva-Cerón M, Salas-Escamilla I, et al. Maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressures: Recommendations and procedure. Neumologia y Cirugia de Torax(Mexico). 2019;78(S2):S135–41.

- Cordeiro, A.L.L.; Soares, L.O.; Gomes-Neto, M.; Petto, J. Inspiratory Muscle Training in Patients in the Postoperative Phase of Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Rehabilitation Med. 2023, 47, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Via Clavero G, Sanjuán Naváis M, Menéndez Albuixech M, Corral Ansa L, Martínez Estalella G, Díaz-Prieto-Huidobro A. Evolución de la fuerza muscular en paciente críticos con ventilación mecánica inva-siva. Enferm Intensiva. 2013 Oct 1;24(4):155–66.

- Perme, C.; Nawa, R.K.; Winkelman, C.; Masud, F. A Tool to Assess Mobility Status in Critically Ill Patients: The Perme Intensive Care Unit Mobility Score. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc. J. 2014, 10, 41–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna, E.W.; Perme, C.; Gastaldi, A.C. Relationship between potential barriers to early mobilization in adult patients during intensive care stay using the Perme ICU Mobility score. Can. J. Respir. Ther. 2021, 57, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolinelli G C, González H P, Doniez S ME, Donoso D T, Salinas R V. Clinical use and inter-rater agreement in the application of the functional independence measure. Rev Med Chil 2001 Jan;129(1):23–31. PMID: 11265202.

- Cid-Ruzafa J, Damián-Moreno J. Valoración de la discapacidad física: el indice de Barthel. Rev Esp Salud Publica 1997 71:127–37. ISSN 2173-9110.

- Wimmelmann, C.L.; Andersen, N.K.; Grønkjaer, M.S.; Hegelund, E.R.; Flensborg-Madsen, T. Satisfaction with life and SF-36 vitality predict risk of ischemic heart disease: a prospective cohort study. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2021, 55, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang-Xu, A.; Vivanco, M.; Zapata, F.; Málaga, G.; Loza, C. Actividad física global de pacientes con factores de riesgo cardiovascular aplicando el “International Physical Activity Questionaire (IPAQ). Rev. Medica Hered. 2011, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizábal Rivera JC, Jaramillo Londoño HN, Rico Sierra M. Pautas generales para la prescripción de la actividad física en pacientes con enfermedades cardiovasculares. Iatreia. 2005 Sep 16(3):240–53.

- Oh, S.-T.; Park, J.Y. Postoperative delirium. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrecht R, Wolf A, Gielen S, Linke A, Hofer J, Erbs S, et al. Effect of Exercise on Coronary Endothelial Function in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000 Feb 17 ;342(7):454–60. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.M.; Abusarea, S.A.; Fouad, B.Z.; Guirguis, S.A.; Shafie, W.A. Effect of Adding Early Bedside Cycling to Inpatient Cardiac Rehabilitation on Physical Function and Length of Stay After Heart Valve Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2024, 105, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Tronstad, O.; Flaws, D.; Churchill, L.; Jones, A.Y.M.; Nakamura, K.; Fraser, J.F. From bedside to recovery: exercise therapy for prevention of post-intensive care syndrome. J. Intensiv. Care 2024, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P (Participants) | C (Concept) | C (Context) |

| Adults >18 who have just been subject to heart surgery |

Therapeutic exercise after heart surgery |

Intensive care unit |

| Authors Country/Year | Number of Participants | Sex | Age, years Mean-Sd |

Body Mass Index | Sedentarism | Hypertension | Dyslipidemia | Type of Surgery | Length of hospital Stay | Duration of Mechanical Ventilation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribeiro BC et al. [13] Brazil, (2021) | 48 | 34 men (70%). | 60 ± 8.3 | 20.5 | NR | 10 | 60% | CABG | 8 days ± 2 | 10 hours ± 4.8 |

| Gama Lordello et al. [15] Brazil, (2020) | 228 | 133 men (58%). | 57 | 26 | 49 % | 156 | 30% | CABG + HVS | 2 days | 5 hours |

| Shirvani et al. [15] Iran, (2020) | 92 | 74 men (82%). | 60 ± 8.72 | 26 | NR | 50 | NR | CABG | 6 days ± 1 | 10 hours ± 2.71 |

| Moreira et al. [16] Portugal, (2019) | 11 | 6 men (55%). | 54 | 30 | NR | 100 | 40 | CABG | NR | NR |

| Han et al. [17] China, (2022) | 46 | 35 men (76%). | 63.0 ± 8.7 | 24.4 | NR | 58 | 24 | CABG | 7 days ± 2 | 10 hours ± 3.6 |

| Cui et al. [18] China, (2020) | 239 | 188 men (78%). | 65.1 ± 4.6 | 25.8 | NR | 33 | 33 | MRV-WEC | 10 days ± 3 | NR |

| Esmealy et al. [19]. Iran, (2023) | 40 | 30 men (75%). | 60 | 26 | NR | 62& | 62 | CABG | NR | NR |

| Bano et al. [20] Pakistan, (2023) | 51 | 35 men (68%). | 55.62 ± 7.62 | 24.6 | NR | 80% | NR | CABG | 7 days | 9 hours |

| Allahbakhshian et al.[21]. Iran, (2023) | 40 | 30 men (75%). | 60.7 ± 4.4 | 26 | NR | 80% | NR | CABG | 7.7 ± 1 | 24 hours after surgery |

| Tsuchikawa et al.[22]. Japan, (2023) | 887 | 689 men (77%). | 68.6 ±9.1 | 23.7 | NR | NR | NR | CABG | 23.4 ± 18 days | 27.6 ± 86.0 hours |

| Kenji Nawa et al. [23] Brazil, (2022) | 44 | 28 men (63%). | 62.3 ± 10.8 | 26.7 | NR | 80% | 34 | CABG + HVS | 8 days | NR |

| Cordeiro et al. [24]. Brazil, (2022) | 55 | 31 men (56%). | 63 ± 9 | 25 | 24% | 56% | 36 | CABG | 8 ± 4 control group, 14 ± 5 intervention group | 6 ± 2 hours |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).