1. Introduction

The convergence of technology and financial services has revolutionized how financial institutions engage with customers and deliver products. This technological disruption gave rise to financial technology (fintech) as a formidable force reshaping traditional banking models. Nearly two decades ago, the theory of disruptive innovation proposed that market entrants gain a foothold by targeting overlooked low-cost segments before gradually challenging incumbents (Christensen, 1997; Yu & Hang, 2010). Disruption occurs when smaller, resource-limited firms successfully challenge established businesses by initially catering to underserved market segments with superior, cost-effective offerings (Christensen & Raynor, 2003). As incumbents prioritize their most profitable customers, they often neglect emerging consumer needs, creating entry points for disruptors to gain traction. Disruptive innovation forces incumbents to redesign strategies to survive market shifts, fundamentally altering competitive dynamics (Markides, 2006).

Global fintech trends underscore the sector’s rapid expansion. In 2018 alone, China’s fintech transaction volume reached $1.6 trillion, followed by the U.S. ($1.26 trillion) and the U.K. ($216 billion) (Statista, 2019). In Africa, Nigeria leads fintech investment, raising $600 million between 2014 and 2020, with $122 million secured in 2019 alone. By mid-2021, Nigerian fintech firms had attracted $276.5 million in funding, with leading disruptors like Flutterwave raising $170 million to expand internationally (CB Insights, 2021). Interswitch, another major Nigerian fintech, secured $200 million in investments from Visa, valuing the company at over $1 billion (TechCrunch, 2019). The African Tech Ecosystem of the Future 2021/2022 Report confirms Nigeria as Africa’s top fintech hub, driven by widespread underbanking and high mobile penetration (fDi Intelligence, 2021).

Scholars have extensively debated fintech’s impact on traditional banks. Foundational marketing theories stress that businesses must anticipate and meet consumer needs for long-term success (Bell & Emory, 1971; Keith, 1960; Kotler & Levy, 1969). However, incumbent banks failed to adapt to shifting consumer preferences, particularly among millennials, resulting in lost market orientation and vulnerability to fintech disruption (Vives, 2017; Philippon, 2019). Disruptive innovation occurs through two primary business models: (i) market-driven disruption, where fintech firms compete on specialized services and lower costs, and (ii) technology-driven disruption, where advanced digital platforms redefine financial services (Gomber et al., 2018). Despite various theoretical frameworks guiding banks’ strategic responses—including the Hold, Make, Ally, Buy/Exit model—empirical evidence on effective managerial adaptation remains scarce (Huang & Rust, 2020).

This study empirically examines how corporate bank managers in an emerging market (Nigeria) respond to fintech disruption. The fintech sector’s expansion continues despite economic uncertainties, fueled by smartphone penetration, a young tech-savvy population, and unmet financial needs in the banking sector. Given the pace of fintech-driven competition, predicting long-term outcomes remains challenging.

Specifically, this study explores how traditionally conservative bank managers adapt to external technological disruptions by assessing whether an entrepreneurial mindset (EM) influences strategic responses. We hypothesize that an entrepreneurial mindset is positively associated with incumbents’ survival strategies in adapting to fintech disruption. This research builds on open innovation theories, emphasizing how firms integrate external innovations to sustain competitiveness (Chesbrough, 2003).

The rest of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the theoretical and conceptual background,

Section 3 outlines the methodology and data,

Section 4 presents the results,

Section 5 discusses key findings, and Section 6 concludes with policy implications.

2. Literature Review

FinTech is reshaping the financial sector, disrupting traditional business models, services, and regulations. Banks, heavily invested in legacy infrastructure, face increasing pressure as digital innovations transform industry structures (Karimi & Walter, 2015). This disruption necessitates strategic adaptation in business operations (Rauch, Wenzel, & Wagner, 2016), technological frameworks (Kjellman et al., 2019), and organizational structures (Utesheva, Simpson, & Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015). FinTech, a fusion of financial services and digital technology, enables mobile payments, virtual currencies, and innovations in B2C and B2B banking, reshaping investment funds and database management (CB Insights, 2018).

FinTech firms leverage customer-centric innovations to challenge traditional banks by unbundling financial services across lending, payments, foreign exchange, and financial advisory. Unlike legacy banks constrained by regulatory and corporate structures, FinTechs operate flexible business models, often bypassing intermediaries through crowdfunding and virtual currencies (Anand & Mantrala, 2019).

Christensen (1997) proposed the Disruptive Innovation Theory, which argues that incumbents can mitigate threats by leveraging internal capabilities or adopting risk-driven innovations. Traditional banks can integrate emerging technologies within existing units or establish separate divisions to address market shifts (Habtay & Holmén, 2014). Given that FinTech disruption is driven by both technological advancements and market dynamics, strategic flexibility is crucial in determining an effective response (Gatignon & Xuereb, 1997).

However, managerial commitment to strategic adaptation depends on an incumbent’s core strategic orientation, which shapes its ability to respond effectively to FinTech challenges (Markides, 2006; Chesbrough, 2003). A strong entrepreneurial mindset within executive leadership enhances adaptability by fostering proactive engagement with innovation. If bank executives adopt FinTech-like agility—enhancing R&D and leveraging core technologies—the threat can be mitigated. Otherwise, incumbents risk market share erosion and underperformance. Entrepreneurial orientation is key, as managers attuned to industry disruptions are more likely to secure a competitive advantage in evolving financial landscapes (Govindarajan et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2005; Miller, 1983; Hult & Ketchen, 2001).

In response to FinTech threats, Duncan (1976), March (1991), and Tushman & O’Reilly (1996) outline three strategic options: (1) leveraging existing technological infrastructure and R&D, (2) acquiring external disruptive skills, or (3) establishing a separate business unit. While integrating disruptive innovation within existing structures is ideal, acquiring and embedding new technologies can be a viable alternative when internal capabilities are insufficient (Atuahene-Gima, 2005; Christensen, 2006).

2.1. The Nature of the FinTech Threat

The effectiveness of a bank’s response depends on how it perceives FinTech disruption. A low perceived threat elicits minimal managerial action, while a high-threat perception demands more aggressive strategic responses.

Johnson, Christensen, and Kagermann (2008) define a firm’s business model as the mechanism through which it creates and extracts value from customers. FinTechs disrupt traditional banking by modifying key components of incumbents’ models, a process known as Business Model Innovation (BMI). These modifications challenge traditional banking operations and force incumbents to reassess their strategies.

FinTech disruptions can be technology-centered or market-centered (Habtay, 2012). Technology-driven disruption challenges incumbent firms by altering industry competencies, while market-driven disruption reshapes customer engagement and distribution channels. The degree of disruption intensifies when both technological and market factors are transformed (Anand & Mantrala, 2019). Banks must assess the extent of FinTech’s impact to formulate effective strategic responses, ensuring long-term adaptability and resilience.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

Understanding how bank managers respond strategically to FinTech threats requires distinguishing between technology-centered and market-centered disruptive business models. According to Anand and Mantrala (2018), business model innovation disrupts incumbents by eroding their relationships with target customers and revenue sources. Market-centered disruption occurs when FinTech firms introduce superior products or services that fulfill unmet customer needs, thereby drawing clients away from traditional banks. Conversely, technology-centered disruption arises when FinTechs outperform incumbents in operational efficiency, ease of use, and functionality through superior technological infrastructure (Habtay & Holmén, 2014; Anand & Mantrala, 2018).

Bank managers' responses depend on their perceived severity of the disruption. A low-perceived threat implies that the impact on customer relationships, revenue, and service segments is minimal, allowing banks to replicate the disruptive innovation internally. In such cases, incumbents can leverage their existing technology, expertise, and financial resources to counteract FinTech advances with minimal burden. However, a high-perceived threat suggests that the disruption is substantial, eroding customer relationships and revenue projections. This scenario signals that the incumbent may lack the necessary technological competencies to replicate FinTech innovations effectively, necessitating significant resource allocation to defend its market position.

Thus, when technology-centered disruption is perceived as minimal, banks can successfully adapt by leveraging in-house capabilities or integrating acquired FinTech innovations within their existing business models. However, if the perceived threat is significant, banks must either invest heavily in technological advancements or restructure their business models to remain competitive. Empirical evidence suggests that incumbents can successfully navigate market-centered disruptions by adopting a market-oriented approach, leveraging core competencies, and integrating disruptive innovations within existing business units (Habtay & Holmén, 2014).

Our conceptual model is adapted from the Entrepreneurial Orientation Framework proposed by Habtay and Holmén (2014). This framework evaluates senior management’s response to disruptive innovation using seven key dimensions:

- (i)

Risk-taking initiatives to address technological and market changes (Covin & Slevin, 1989).

- (ii)

Strategic flexibility to adapt to disruption (Zhou et al., 2005).

- (iii)

Championing disruptive ventures within the organization (Hamel, 2000).

- (iv)

Screening and approving diversified projects to enhance innovation (Cooper et al., 2003).

- (v)

Resolving cultural and managerial tensions between innovation units and traditional business operations (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004).

- (vi)

Setting strategic direction for emerging business units.

- (vii)

Allocating resources to explore and develop new ventures (Christensen & Raynor, 2003).

In Nigeria’s banking sector, valued at over $9 billion, a significant portion of the population remains underserved, particularly in rural areas. Issues such as limited financial access, affordability, and poor user experience have allowed FinTechs to rapidly gain market share by offering enhanced customer value propositions (Anand & Mantrala, 2019). These upstarts leverage business model innovations in digital payments, lending, and investment solutions, effectively competing with traditional banks.

Given the competitive pressure from FinTechs, we seek empirical evidence on how bank managers respond to disruption. We argue that traditional banking professionals facing FinTech competition are likely to develop an entrepreneurial mindset, enabling them to innovate within existing business models. While market-centered disruptions initially cause instability, their impact tends to diminish as incumbents leverage sustaining business models to compete effectively.

Thus, we hypothesize:

H1:

Entrepreneurial mindset (EM) is positively related to the incumbent’s survival strategy in responding to and adapting to FinTech disruption.

| VARIABLE |

MEASURE |

| CDS |

Championing radical or disruptive ventures |

| CBP |

Committed to strategic flexibility to face the challenges brought by disruptive innovation |

| UMP |

To undertake risk initiatives in response to radical technology and market price changes |

| HOP |

Screening and approving holistically projects for the new unit |

| SBS |

Setting strategic direction for the new business unit |

| ABP |

Accept to resolve all managerial conflicts between parties-managers of the new unit (innovation) and traditional units

|

| IBP |

Allocating budget for the innovation/ new partner unit

|

| BCV |

Entrepreneurial mindset (EM) is positively related to the incumbent’s survival strategy in the bank’s response and adaptation to fintech disruption. |

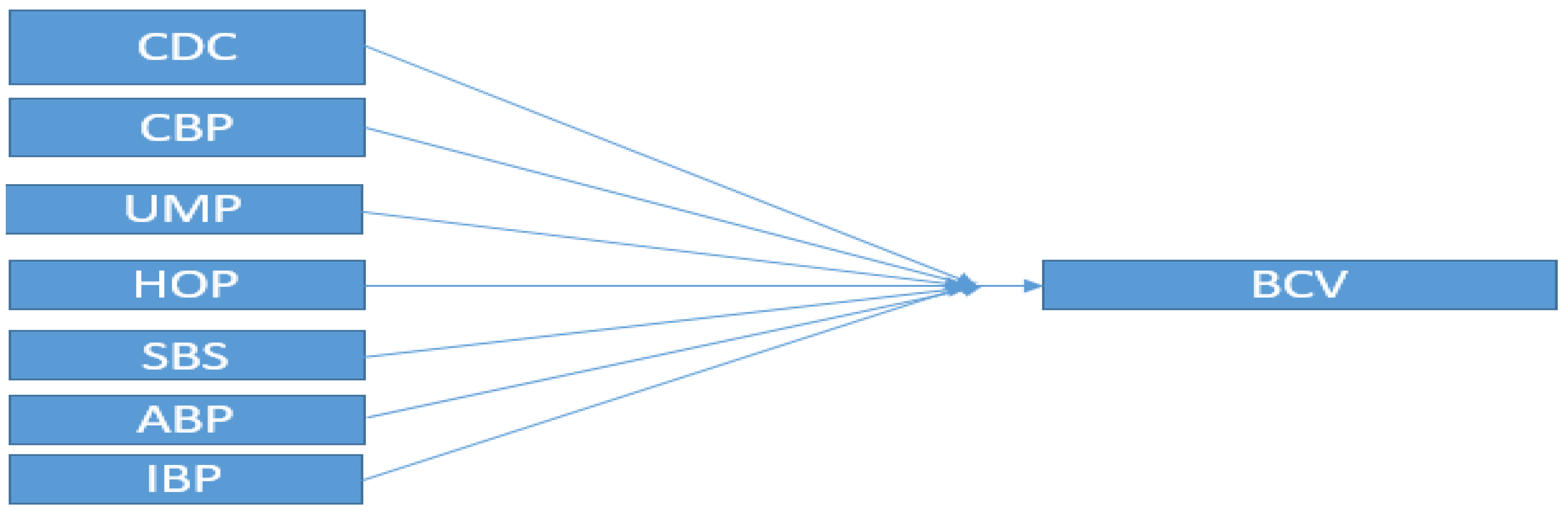

3. Methodology and Data Collection

This study examines bank managers' responses to FinTech disruption in Nigeria using a structured questionnaire based on the conceptual model in

Figure 1. The research targets eight commercial banks, comprising four with international authorization and four with national authorization.

A criterion sampling method was employed, selecting participants based on predefined criteria to ensure a focused investigation. This method facilitates an in-depth understanding of specific phenomena, allowing for rich qualitative insights to complement the quantitative dataset (Patton, 2001, p. 238). The questionnaire measures managerial orientation, entrepreneurial mindset, and human competencies required to develop and manage disruptive innovations. Respondents assessed senior management’s role in selecting technical teams responsible for handling FinTech threats. Additionally, demographic questions were included, and responses were collected using a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). The questionnaire was distributed via Google Forms, reaching managers in 84 strategic business units across the selected banks through email, WhatsApp, and other digital platforms. Completion time averaged seven minutes, with a 93% response rate yielding 84 valid responses.

To ensure reliability and validity, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to test internal consistency. A coefficient above 0.7 indicates high reliability, while values below 0.6 suggest weak reliability (Sharma, 2016; Novak, 2020). This ensures that the independent variables effectively measure the dependent variable, validating the robustness of the study.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptives

The study employed Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to assess the reliability of the correlation between independent and dependent variables.

Table 1 reports a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.975, exceeding the 0.7 threshold for acceptable reliability, confirming strong internal consistency in the measurement of explanatory and predicted variables (Cronbach, 1951).

In selecting the sample population, the study targeted banking professionals across diverse strategic business units, income levels, and career grades—individuals with direct market intelligence on FinTech threats to the banking sector.

Table 2 indicates that 83% of respondents spend over five hours daily using FinTech digital channels, while 12% engage for two to five hours and 5% use them for less than two hours each day.

The results indicate that 79% of respondents hold postgraduate degrees, while 14% are university graduates and 7% are college graduates. This high level of education suggests strong awareness of FinTech threats within the banking sector. The sample comprises 65% male (n = 55) and 35% female (n = 29) professionals. In terms of annual income, 2% of respondents earn approximately $59,000, while 52% report earnings of $30,000. Additionally, 14%, 13%, and 13% earn $15,000, $7,300, and $3,000, respectively. The distribution of career levels shows that 11% of respondents are in top executive management, 51% hold middle management positions—responsible for executing FinTech threat mitigation strategies—while 10% are managers. Bank officers and outsourced staff account for 14% and 5% of the sample, respectively.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

The results of the correlation analysis examine the relationships between the seven explanatory variables—CDS, CBP, UMP, HOP, SBS, ABP, and IBP—and the dependent variable, BCV. The findings indicate a positive correlation between all explanatory variables and BCV, suggesting that each management response measure contributes positively to mitigating FinTech threats in the banking sector. Furthermore, all predictor variables exhibit statistical significance at the 0.01 level, reinforcing the robustness of these relationships.

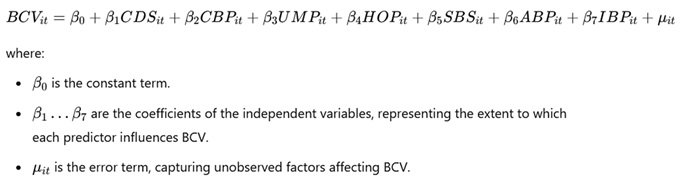

4.3. Regression Analysis

This study employs a multiple regression model to examine the relationship between seven independent variables—UMP, CBP, CDS, HOP, SBS, ABP, and IBP—and the dependent variable, BCV, which represents entrepreneurial orientation and high responsiveness to FinTech disruption threats. The model is specified as follows:

Table 4 presents the results of the multiple regression analysis used to test the study’s hypothesis. The model summary reveals a high multiple correlation coefficient (R = 0.976), indicating a strong positive relationship between the dependent variable, BCV (entrepreneurial orientation activation in response to external FinTech disruption), and the seven predictor variables—CDS, CBP, UMP, HOP, SBS, ABP, and IBP. These independent variables represent proactive managerial responses aimed at leveraging internal core competencies to counteract FinTech threats, deviating from traditional bureaucratic inertia in legacy banking institutions.

The coefficient of determination (R²) is 0.948, signifying that 94.8% of the variation in BCV is explained by the independent variables, underscoring the model’s predictive strength. The adjusted R² of 0.952 further confirms the robustness of the model, with only 5% of variations attributable to external factors not included in the framework. Additionally, the model’s significance is reinforced by an F-change value of 0.000, confirming that all predictor variables exert a statistically significant impact. These results suggest that bank managers' strategic responses to FinTech disruption are largely shaped by the identified explanatory variables, validating the model's reliability in predicting managerial adaptation to disruptive threats.

The ANOVA results confirm that the predictor variables have a statistically significant impact on the dependent variable, aligning with the model specification. This indicates that the independent variables collectively contribute to explaining variations in the dependent variable, supporting the robustness of the regression model.

Table 6.

Regression Coefficients.

Table 6.

Regression Coefficients.

| Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized

Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

| *B |

Std.Error |

Beta |

| 1 |

(Constant)* |

0.006 |

0.12 |

|

0.051 |

0.959 |

| |

CDS |

0.103 |

0.083 |

0.102 |

1.245 |

0.217 |

| |

CBP |

0.408*** |

0.076 |

0.418 |

5.401 |

0.000 |

| |

UMP |

0.035 |

0.06 |

0.037 |

0.593 |

0.555 |

| |

HOP |

0.087* |

0.048 |

0.095 |

1.805 |

0.075 |

| |

SBS |

0.246*** |

0.062 |

0.251 |

3.981 |

0.000 |

| |

ABP |

-0.013 |

0.069 |

-0.013 |

-0.181 |

0.857 |

| |

IBP |

0.138 |

0.061 |

0.151 |

2.25 |

0.027 |

| Dependent Variable: BCV |

|

|

|

|

4.4. Discussion

The regression results indicate that 94.8% of the variance in entrepreneurial mindset can be explained by the seven response measures, F(7, 76) = 215.330, p < 0.001, supporting H1: Entrepreneurial mindset (EM) is positively related to the incumbent’s survival strategy in response to fintech disruption. This aligns with previous studies, which highlight that internal innovation fosters business model transformation, organizational reinvention, and profitability improvements (Habtay & Holmen, 2014; Nazar et al., 2018; Brown & Eisenhardt, 1998; Covin & Miles, 1999; Covin & Wales, 2010; Jalali, 2012; Wang & Yen, 2012; Wiklund, 1999).

Examining individual contributions, CBP (β = 0.418, t = 5.401, p = 0.000), SBS (β = 0.251, t = 3.981, p = 0.000), and IBP (β = 0.151, t = 2.250, p = 0.027) significantly predict EM, while CDS (β = 0.102, p = 0.217), UMP (β = 0.037, p = 0.555), and HOP (β = 0.095, p = 0.075) show weaker effects. These findings suggest that strategic flexibility (CBP), clear strategic direction (SBS), and financial commitment (IBP) play key roles in shaping managerial adaptation to fintech disruption.

Traditional banks assess fintech threats based on their potential to erode customer relationships, revenue projections, and service coverage. If the perceived threat is low, incumbents leverage internal resources to develop competing innovations while maintaining a focus on high-value market segments (Christensen & Raynor, 2003). However, when the threat is high, radical strategic responses become necessary, requiring significant investment in internal capabilities, new business units, or technology acquisition.

Both correlation and regression analyses confirm that all response measures positively correlate with an entrepreneurial mindset. The predictor variables, which include championing disruptive ventures (CDS), commitment to strategic flexibility (CBP), risk-taking initiatives (UMP), project screening (HOP), setting strategic direction (SBS), conflict resolution between innovation and legacy units (ABP), and budget allocation for innovation (IBP), collectively contribute to proactive managerial adaptation. The high R² value (95%) demonstrates that these measures effectively predict the likelihood of executive management adopting a self-disruptive innovation strategy to counter fintech threats. This supports the argument that firms become more proactive when they perceive a decline in their competitive advantages (Covin et al., 1990; Henderson, 2006).

4.5. Contribution

This study advances the literature on disruptive technology and entrepreneurial orientation in the Nigerian banking sector. It builds on prior research by conceptualizing entrepreneurial mindset as a critical factor in incumbent banks’ responses to fintech threats. The findings confirm that entrepreneurial orientation plays a decisive role in shaping managerial responses to disruption, reinforcing the broader discourse on strategic adaptation in rapidly evolving financial markets.

4.6. Implications

The study offers practical insights for bank executives and financial service providers in Nigeria and other emerging markets. It highlights the need for an entrepreneurial mindset to counteract fintech disruptions, challenging the traditional conservatism of banking institutions. The findings emphasize that fostering internal innovation, strategic flexibility, and proactive self-disruption is essential for banks to maintain market dominance and adapt to evolving consumer expectations.

4.7. Limitations of the Study

One key limitation is the scarcity of prior empirical research on fintech disruptions in Nigeria’s banking sector, which constrains comparative analysis. Additionally, the reliance on a quantitative survey using Likert-scale responses introduces potential biases in participants’ self-reported data (Macinati, 2008). Future research should incorporate a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative and quantitative analysis for deeper insights.

5. Conclusion

Banks possess the internal competencies and resources necessary to counter fintech disruption, particularly when the perceived threat is low. However, when faced with technology-centered business model innovation, more proactive, innovative, and risk-intensive strategies are required. In such cases, banks must leverage their IT infrastructure, technical expertise, and financial resources—either internally or through external acquisitions—to develop competitive solutions. When the incentive and necessity for action are high, incumbents can replicate fintech-driven innovations within their existing structures, ensuring continued market relevance.

The Nigerian banking sector is undergoing significant technology-driven transformation, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. A notable example is Guaranty Trust Bank (GTBank), which is actively restructuring its operations to remain competitive in a digital-first economy (Agbaje, 2021). Rather than forming partnerships with fintech firms, Nigerian banks are increasingly building in-house fintech capabilities to counter external disruption. This shift highlights a strategic transition toward agility and innovation, positioning banks to combat fintech competition through market- and technology-centered business models.

The future of Nigeria’s banking sector will be shaped by continuous business model innovation. However, sustainable adaptation depends on top management’s ability to attract and retain innovative talent while fostering a culture of strategic flexibility. While this study provides insights into how bank managers respond to fintech disruption, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the findings may not fully capture responses across all emerging markets due to differences in corporate culture and regulatory environments. Second, the scarcity of empirical research on fintech disruption in Nigeria limits comparative analysis. Third, structural constraints, including government influence on regulatory policies, may restrict banks’ ability to pursue radical innovation. Additionally, unexplored factors such as board dynamics and organizational culture may further shape banks’ responses. Future research should address these gaps by incorporating cross-market comparisons and qualitative insights into managerial decision-making.

References

- Alam, N. , & Ali, S. N. (Eds.). (2020). Fintech, Digital Currency and the Future of Islamic Finance. [CrossRef]

- Anand, D. , & Mantrala, M. Responding to disruptive business model innovations: The case of traditional banks facing fintech entrants. Journal of Banking and Financial Technology 2019, 3, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M. L. , & Emory, C. W. The faltering marketing concept. Journal of Marketing 1971, 35, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CB Insights. (2018). More Banks Are Beginning to Acquire Fintech Startups. Retrieved , 2018, from https://www.cbinsights. 19 November.

- Chesbrough, H. The era of open innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review 2003, 127, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

- Gatignon, H. , & Xuereb, J. M. Strategic orientation of the firm and new product performance. Journal of Marketing Research 1997, 34, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Habtay, S. R. A firm-level analysis on the relative difference between technology-driven and market-driven disruptive business model innovations. Creativity and Innovation Management Journal 2012, 21, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtay, S. R. , & Holmén, M. Incumbents’ responses to disruptive business model innovation: The moderating role of technology vs. market-driven innovation. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 2014, 18, 289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, J. , & Walter, Z. The role of dynamic capabilities in responding to digital disruption: A factor-based study of the newspaper industry. Journal of Management Information Systems 2015, 32, 39–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, R. J. The Marketing Revolution. Journal of Marketing 1960, 24, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilkki, K. , Mantyla, M. , Karhu, K., Hammainen, H., & Ailisto, H. A disruption framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2018, 129, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Kjellman, A. , Björkroth, T. , Kangas, T., Tainio, R., & Westerholm, T. Disruptive innovations and the challenges for banking. International Journal of Financial Innovation in Banking 2019, 2, 232–249. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, A. K. , & Jaworski, B. J. Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing 1990, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P. , & Levy, S. J. Broadening the concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing 1969, 33, 10–15 http://wwwncbinlmnihgov/pubmed/12309673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markides, C. Disruptive innovation: In need of better theory. Journal of Product Innovation Management 2006, 23(SI), 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, M. , Wenzel, M., & Wagner, H. T. (2016). The digital disruption of strategic paths: An experimental study. Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Information Systems. Association for Information Systems. https://aisel.aisnet. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- TechCrunch. (2021). African Tech Took Center Stage in 2021. https://techcrunch. 2021.

- Topsy Kola-Oyeneyin, M. , Kuyoro, M., & Olanrewaju, T. (2020). Harnessing Nigeria’s Fintech Potential. McKinsey & Company, 20 Report. https://www.mckinsey. 20 September.

- Utesheva, A. , Simpson, J. R., & Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. Identity metamorphoses in digital disruption: A relational theory of identity. European Journal of Information Systems 2015, 1–20.

- Nairametrics. (2021). Nigeria Has the Most Startups in Africa but Ranks Low Due to Its Challenging Environment. https://nairametrics. 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).