1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) connected to medical devices or software is innovating healthcare by collecting data in real-time, remotely monitoring patients, and exchanging data among service providers. Medical Internet of Things (IoMT) devices, such as fitness trackers, implantable medical devices, and telemedicine plans, improve patient outcomes by providing health information. IoMT uses vital signs, medication adherence, and other information to help doctors make better decisions, maintain patient health, and prevent hospitalizations. This network strategy aims to improve patient care and public health by collecting large amounts of medical data, detecting patterns, predicting health crises, and utilizing medical resources. AI-supported algorithms collect vast amounts of data from IoMT devices and identify signs of chronic diseases such as heart disease or diabetes. Regular evaluation and analysis of data improve patient outcomes and reduce the costs of treatment, emergencies, and hospitalizations. IoT medical devices enhance healthcare services through connectivity and real-time data exchange, but they pose risks to patient safety and privacy. Criminals can exploit sensitive health information coming from these devices. The advanced authentication and encryption techniques in IoMT devices are difficult to implement due to limited processing capabilities [

6]. Decentralized IoMT devices, including distributed networks and data systems, create a large attack surface. Hackers can infiltrate networks with a vulnerable device, steal patient data, and jeopardize the health care system. Attackers can steal medical information, misdiagnose patients, monitor heart rates, and disable insulin pumps. The security challenges are exacerbated by the interoperability of devices between manufacturers with different security standards [

8]. Device security flaws prevent end-to-end secure connections due to this difference. Critical care providers using IoMT must address these security challenges to protect patient confidentiality and life-critical medical procedures.

The incorporation of Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) devices in healthcare has transformed the sector by facilitating real-time data collection, patient monitoring, and secure data exchange. Nonetheless, this progress brings forth challenges, especially concerning security, privacy, and interoperability, as emphasised by Pradyumna et al. [

1]. The changing dynamics of healthcare technology necessitate strong encryption solutions, as conventional cryptographic techniques frequently prove inadequate in resource-limited IoT settings. Bhambri and Khang [

2] highlight the essential function of AI and IoT technologies in the management of healthcare data, whereas Shafik [

3] investigates the convergence of AI and IoMT to transform healthcare delivery using machine learning techniques. Mostafa and El-Atawi [

4] provide valuable insights by exploring strategies for performance enhancement in critical healthcare settings, emphasising the importance of secure and efficient systems to improve emergency response. Bala et al. [

5] emphasise the significance of lightweight cryptographic algorithms in effectively securing sensitive health data, addressing these concerns comprehensively. In light of this context, the current investigation utilises the ASCONv1.2 algorithm, which has been optimised via Hypercube Optimal Search (HOS) and Modified Wild Geese (MWG) techniques, to improve both security and efficiency in medical IoT devices. This strategy seeks to achieve a harmonious equilibrium between strong security protocols and the functional constraints of these devices, safeguarding essential healthcare information.

Medical IoT devices benefit healthcare systems but have performance and security limitations. Compact, energy-efficient gadgets have limited processing power, memory, and the lifespan of batteries [

9]. Complex encryption or multi-factor authentication can drain batteries or overtax processors, lowering device longevity and downtime. The balance between confidentiality and resource efficiency makes it challenging to protect medical IoT devices from intrusions without affecting their essential functionalities, which are needed for continuous and accurate health monitoring. Many medical IoT devices use low-power, short-range protocols for communication like Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) or Zigbee for real-time data transfer [

10,

11]. Insecure methods preserve energy but leave devices exposed to listening in, man-in-the-middle, and interference with signals. Resource constraints make dynamic updates and software patches difficult, leaving many medical IoT devices susceptible to known issues. Portable, effective encryption systems for medical IoT contexts are needed due to the broad range of device kinds and manufacturers, which sometimes leads to Unstandardized security measures [

12,

13]. Lightweight cryptography system secures data transit and handling without burdening devices. Unlike normal encryption, lightweight techniques secure the device's main medical functions with less computational effort [

14]. Using lightweight encryption, essential patient data may be safely transmitted in real time without draining battery life or device performance [

15]. Medical personnel can meet regulatory requirements by safeguarding patient data on devices with limited resources with lightweight cryptography. Simple and efficient lightweight cryptography is a universal option for health IoT devices and systems [

16]. This technique protects sensitive health data from hackers and enables smooth integration in varied environments, strengthen healthcare infrastructure. Data storage and transportation are protected by cryptographic methods including elliptic curve cryptography (ECC), advanced encryption standard (AES), and Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA) [

17]. Medical IoT devices lack the processing power and memory needed for traditional encryption methods, which are computationally expensive. Although RSA encryption is safe, it takes a lot of work to create keys and encrypt data, which might drain the battery of an embedded device or implanted health monitor [

18]. Although AES is effective, its processing demands may cause low-powered medical IoT equipment to lag. Medical IoT applications that demand real-time performance are hampered by the delay imposed by traditional cryptography techniques [

19]. Health monitoring may be crucial in emergency situations, but high-latency cryptography systems might cause delays. It is challenging to incorporate traditional algorithms across IoT devices from many manufacturers with varying resource constraints since they were not designed for interoperability [

20]. These problems underscore the need for cryptographic solutions that consider the constraints of IoT devices while offering strong security.

We propose a lightweight cryptographic algorithm for medical IoT devices with limited resources, taking into account the shortcomings of traditional encryption techniques, such as their high processing cost, latency, and lack of scalability. Since standard methods like RSA, AES, and ECC need a lot of processing power and memory, which these devices typically lack, medical IoT applications face significant challenges. Furthermore, the delay these methods cause often hinders real-time monitoring and decision-making, which are critical for healthcare applications. To solve these challenges, our proposed algorithm focuses on finding a compromise between resource efficiency and strong security.

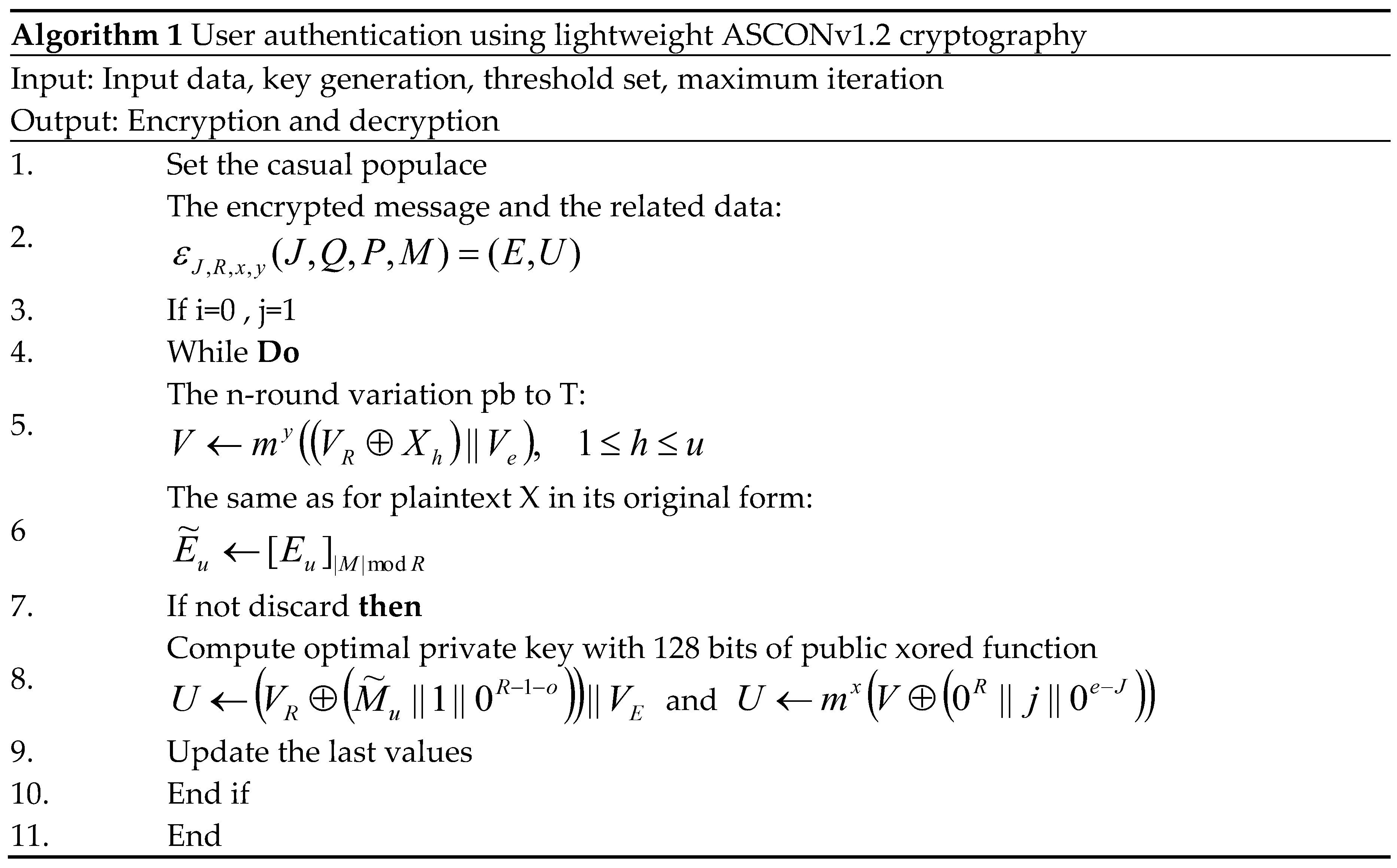

One of the early significant contributions of this work was the use of the ASCONv 1.2 encryption algorithm for effective encryption and decryption. ASCONv 1.2 is a lightweight and secure algorithm suitable for resource-constrained environments.

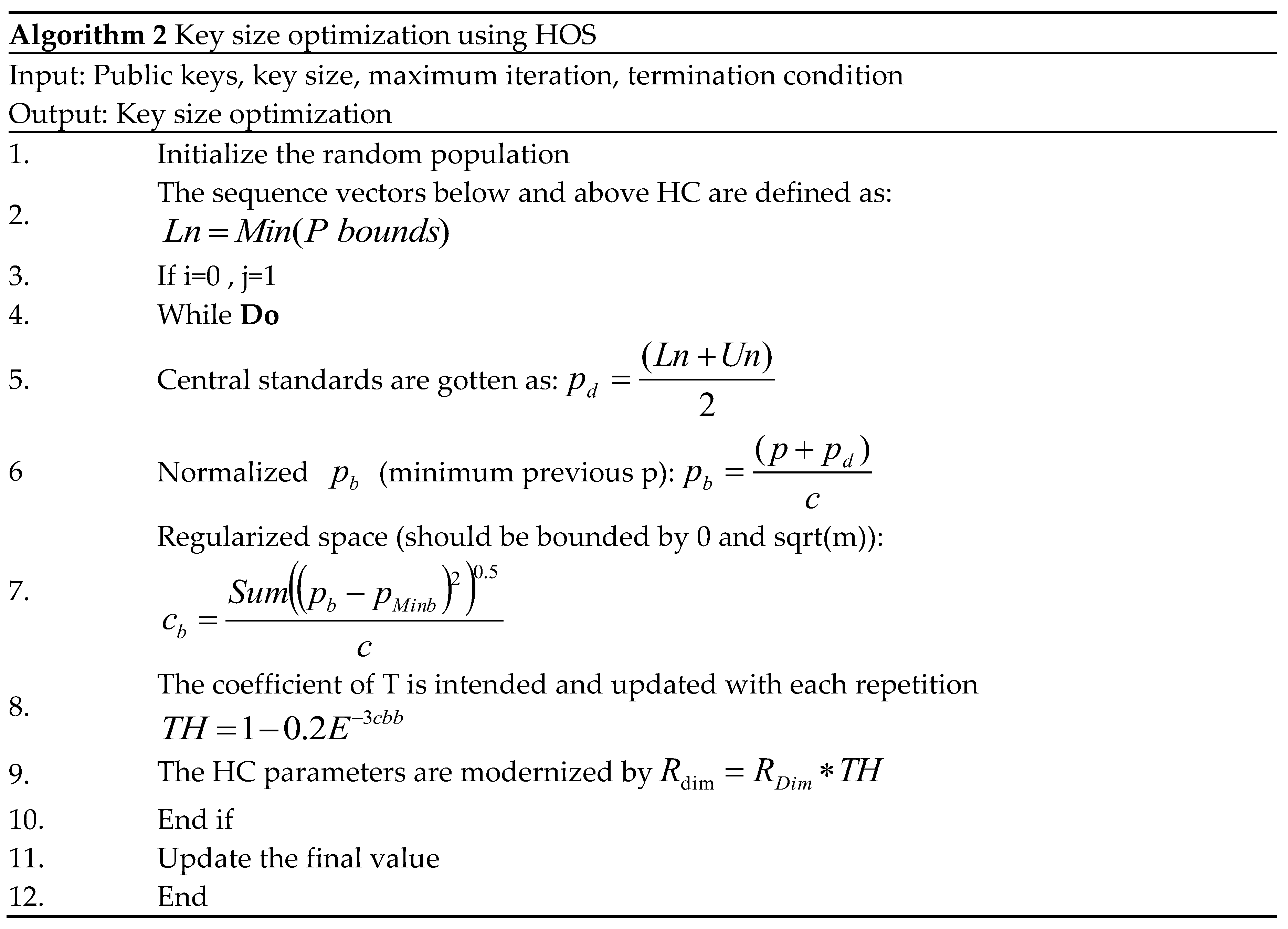

To adapt ASCONv 1.2 to IoT medical devices, we use the Hypercube Optimal Search (HOS) algorithm to optimize key size and function parameters, while providing strong protection and improving adaptability and energy efficiency.

The modified White Swan algorithm (MWG) enhances the local and global search capabilities of the encryption model. It significantly improves resource efficiency, extends device battery life, and enables consistent real-time operation without compromising the security performance of IoT devices.

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed model, detailed experiments were conducted using the clinical picture dataset. To assess the performance, performance metrics such as PSNR, MSE, BER, SSI and correlation coefficient were used. The results demonstrate the model's ability to maintain the quality and integrity of medical images while simultaneously preserving medical information.

The article is organized as follows: A thorough assessment of the literature on ultra-light cryptography in the healthcare industry is given in

Section 2. The suggested techniques are explained in

Section 3. These include the use of the ASCONv 1.2 encryption algorithm for encryption and decryption, the HOS algorithm for key size optimization, and the MWG algorithm for local and global search. An extensive explanation of the outcomes derived from the suggested model is given in

Section 4. Lastly, paragraph 5 marks the article's conclusion.

2. Related Work

In this section, we present a literature review on ultra-lightweight cryptography methods in healthcare, highlighting the need for secure and efficient solutions suitable for resource-constrained medical IoT devices, as well as the shortcomings of current methods. This discusses the difficulties caused by computational power limitations and explores various encryption algorithms, optimization methods, and their application in protecting medical information.

Alruwaili et al. 2024 [

21] provide a simple and effective authentication system to meet the security needs of smart medical systems and enhance performance. Cloud architecture enables secure authentication with minimal computational and communication requirements, making it ideal for resource-constrained medical IoT devices. According to the test results, this method significantly reduces overhead, which is crucial for real-time medical applications that require low latency and quick response. This dual-layered testing method boosts trust in the mechanism's capacity to secure private medical information between devices and people. Chinbat et al. 2024 [

22] highlighted growing worries about patient data security and privacy as healthcare institutions adopt IoT. IoT devices capture and send important health data, requiring strong security. These resource-constrained devices could use lightweight cryptography (LWC) methods to protect data. RECTANGLE performed best in decryption speed, energy efficiency, memory utilization, and throughput, making it excellent for healthcare IoT applications. Zitouni et al. 2024 [

23] provided LWBC_DNA, a lightweight power-efficient Block Cipher, to protect IoMT data and optimize energy usage to extend device lifespan. A hybrid Replacement a permutation network and Feistel network design combines DNA with lightweight cryptography. LWBC-DNA generates 32-bit ciphertext from 64-bit data blocks using a 16-bit key over 16 rounds using combination, XOR, and XNOR. LWBC-DNA is for IoMT applications due to its security, simplicity, storage effectiveness, and energy utilization. Sheena et al. 2024 [

24] examined regular, ultra, hybrid, and multilevel lightweight cryptography methods for resource-constrained IoT devices. The report discusses IoT security issues such data surveillance, illicit use, and denial of service attacks and how these lightweight methods might prevent them. They also examine the actual issues of using these algorithms, such as balancing security with efficiency of performance, scalability, and emerging security threats. Ahmad et al. 2024 [

25] focused on healthcare surveillance equipment security and the necessity for robust security to protect patient data in IoT contexts. A technique enhances health care IoT system security and efficiency, ensuring continued operation in resource-limited scenarios. The suggested method encrypts sensitive medical data transported and stored, preventing data breaches in critical use cases like remote patient monitoring. This strategy enhances system performance, demonstrating that high security and operational efficiency be balanced, promoting safer, scalable, and more dependable digital health ecosystems.

Qasem et al. 2024 [

26] covered cloud-based IoT encryption solutions in detail, emphasizing their significance in data security and confidentiality. Symmetric, asymmetric, lightweight, and hybrid encryption methods secure sensitive data transmitted between IoT gadgets and cloud servers. Elhamzi et al. 2024 [

27] presented FPGA-based crypto-watermarking for videoconferencing medical images to secure patient privacy, integrity, and validity. Least significant bit (LSB) watermarked and lightweight encryption device encryption hides a message in medical photos. The median PSNR is 86.98 dB, ensuring excellent imperceptibility even under assault conditions at 53.68 dB. A PSNR of 82 dB and 77% speed boost over real-time logic versions make this FPGA-based medical image processing solution safe and efficient. For smart home healthcare, Popoola et al. 2024 [

28] proposed a hybrid encryption architecture using AES-128 and ECC-256r1 in EAX mode. Following thorough testing, the framework outperforms earlier systems in terms of energy efficiency, processing speed, and security. The framework is appropriate for real-time encryption of health data streams in Internet of Things contexts because to its 25.6% client-side processing performance improvement and up to 44% server-side energy savings over RSA-2048. Rana et al. 2024 [

29] completed an energy effectiveness and safety audit of the IoT lightweight block cipher (LWBC). They suggested cipher has lower energy usage per bit than LWBCs, making good choice for energy-limited cryptographic devices. IoT applications that emphasize power and security can use the LWBC as a scalable, sustainable cryptographic solution.Al et al. 2024 [

30] proposed quantum-inspired ultra-lightweight encryption to improve IoT device security, which often has resource constraints. Due to its 12.4ms processing speed, 3.2 kilobyte storage footprint, and low energy consumption and suited for real-time, energy-sensitive IoT application. Due to concerns about the number and complexity of IoT devices, the algorithm is an effective and secure IoT security solution.

From the literature review [

21]-[

30], we found the problems form the existing state-of-the-art models. Resource-constrained IoT devices in healthcare often lack the computational power, memory, and energy efficiency needed to implement robust security measures. For real-time medical applications like emergency response systems and remote patient monitoring, traditional cryptographic methods are unfeasible due to their high computing resource requirements. One of the most important challenges is ensuring robust encryption for healthcare IoT data while preserving system performance. For speed and energy economy, lightweight cryptographic techniques frequently sacrifice security. Finding a balance that offers sufficient safety without sacrificing throughput or latency is crucial, especially for applications that are vital to life. Current cryptography methods frequently don't scale or adjust to different IoT healthcare settings. With the rapid proliferation of IoT devices, scalable security models that can accommodate heterogeneous device capabilities and dynamically adjust to varied resource constraints are lacking. As the sophistication of cyber-attacks evolves, existing lightweight cryptographic algorithms face challenges in resisting threats like side-channel attacks, quantum computing vulnerabilities, and advanced data interception techniques. IoT devices in healthcare often operate on limited power sources, such as batteries, making energy efficiency a crucial concern. Many cryptographic techniques impose significant energy costs, reducing device lifespan and reliability. This issue hinders the adoption of secure IoT systems in scenarios requiring prolonged operation, such as wearable health monitors and implantable devices. IoT healthcare devices communicate with cloud-based systems for data storage, processing, and analytics [

31,

32]. Ensuring protected and efficient data transmission between IoT plans and cloud servers is persistent challenge. Existing models either fail to optimize communication or compromise security during data transfer. Protecting patient data privacy while ensure compliance with healthcare regulations remains significant challenge. Lightweight cryptographic methods often lack mechanisms to enforce data anonymization, access control, and audit trails, increasing the risk of data breaches and legal liabilities. To address these challenges, we define the following objectives:

Develop lightweight cryptographic techniques that minimize computational, memory, and energy requirements, ensuring compatibility with resource-constrained IoT devices in healthcare.

Design scalable and adaptable security frameworks that dynamically adjust to diverse healthcare IoT environments, accommodating varying device capabilities and resource constraints.

Establish robust cryptographic solutions capable of resisting advanced cyber threats, including quantum computing-based attacks, side-channel vulnerabilities, and other emerging security risks.

Create secure and efficient data transmission methods facilitate seamless communication among IoT procedures and cloud facilities, confirming the protection of sensitive healthcare data during transit.

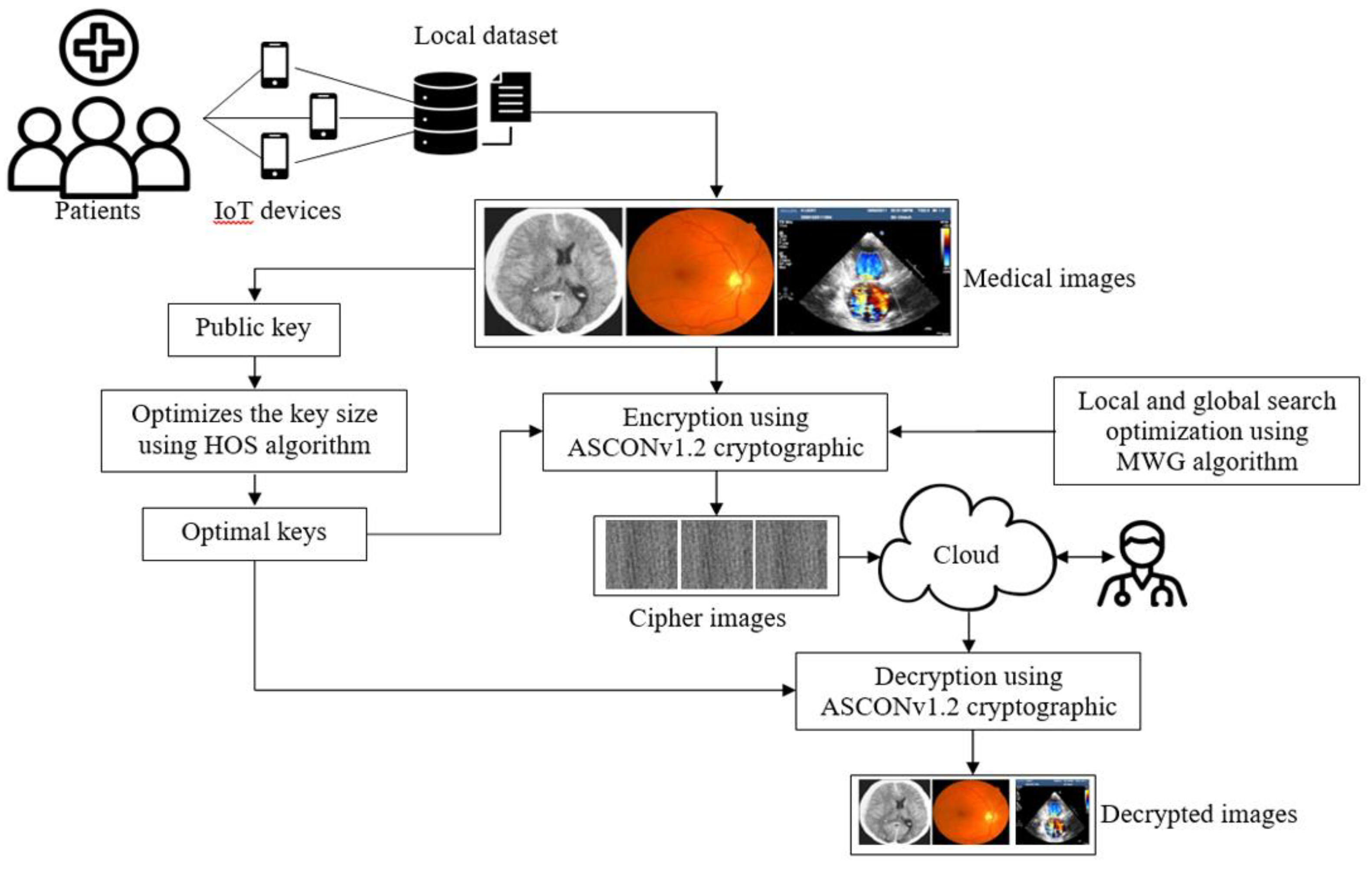

The proposed system for enhancing healthcare security through ultra-lightweight cryptography is designed to address the specific needs of medical IoT devices with limited resources. As shown in

Figure 1, the process begins with the collection of medical images, such as CT scans, MRIs, ultrasounds, and iris images, which are captured by IoT-enabled devices like mobile phones and cameras. This optimization is achieved through the Hypercube Optimal Search Algorithm (HOS) and is used to determine the key size and parameters of the most efficient operation. This ensures that the selected key provides strong security without overloading the device's computational resources or memory. To improve the optimal search performance of cryptographic parameters, a modified Weichsel algorithm (MWG) is used. It enhances local and global search capabilities, ensuring an optimal balance between encryption model security and resource utilization. The ASCONv 1.2 encryption algorithm is used to encrypt medical images with optimal parameters. The optimized code generated by HOS and MWG methods is used for the secure encryption of medical images with this algorithm, ensuring that sensitive patient data is protected during transmission and storage. After encryption, the encrypted medical images are stored in the cloud. This cloud storage allows medical professionals to securely access images from any device, ensuring a high level of security and medical information for remote consultations. When medical professionals need to access the images, they use the ASCONv 1.2 algorithm's decryption process and the Optimize key to retrieve the original medical images from the cloud. This ensures that only authorized persons can encrypt and view the images, thereby protecting patient privacy and data integrity. Various performance metrics are used to compare the encrypted images with the original images to assess the performance of the encryption model. SSI assesses the structural similarity between the original image and the encrypted image, while the correlation coefficient measures the similarity in pixel intensity between the two images. This measurement provides a comprehensive assessment of the security and performance of the encryption system, ensuring that the encryption process provides strong protection for sensitive medical information without significantly degrading the quality of the medical images.

4. Results and Discussion

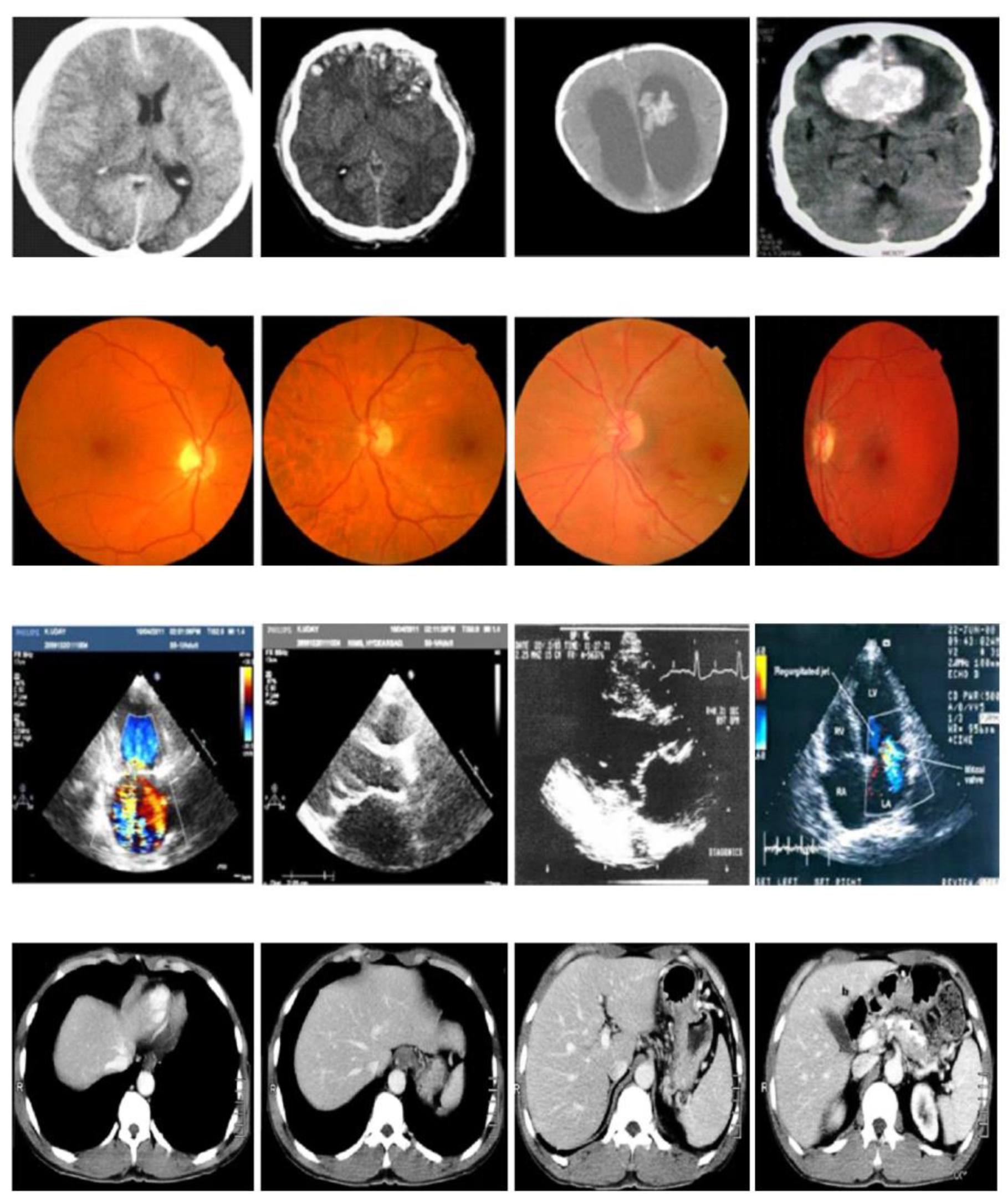

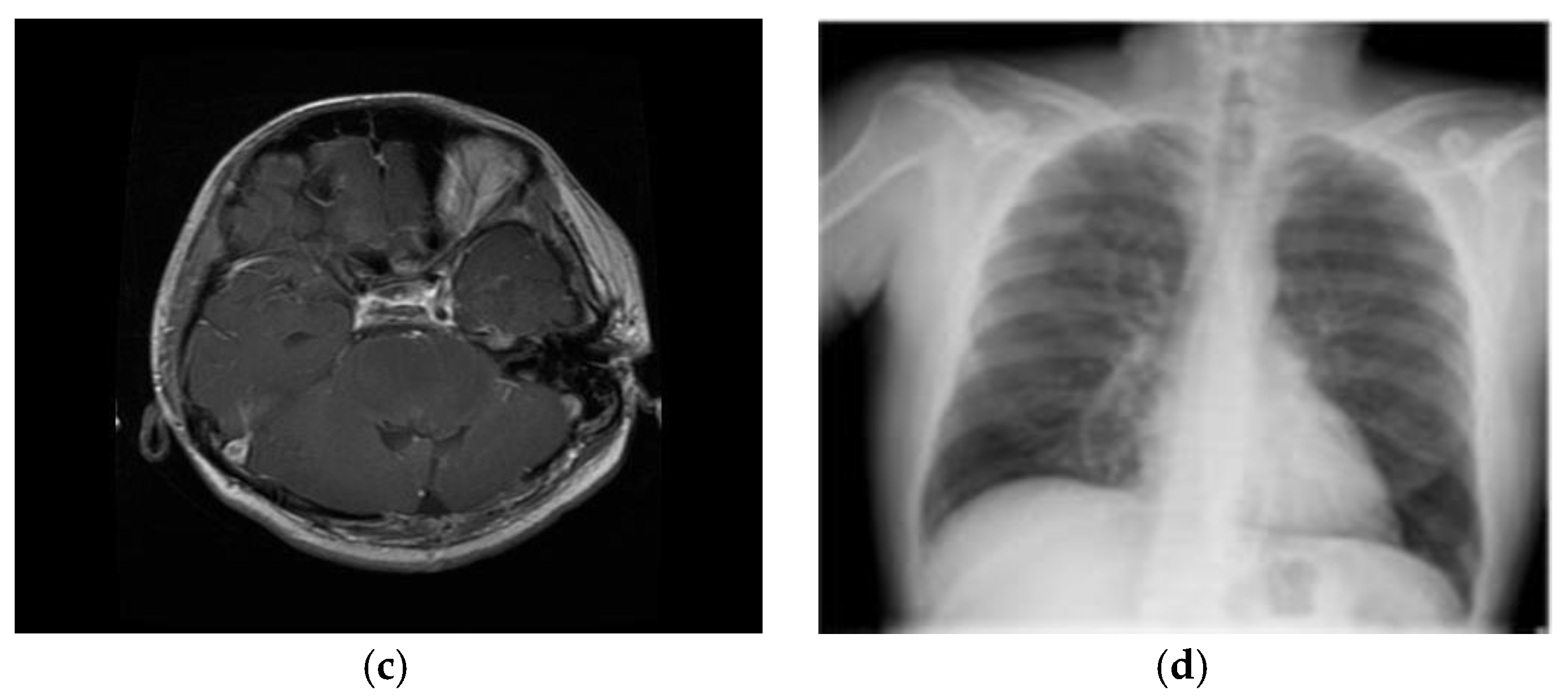

This segment details the results and comparative study of the insubstantial cryptographic processes for resource-constrained medical IoT plans, evaluated alongside existing models. The model was implemented using Python, with TensorFlow 2.0 and Keras frameworks, and tested on medical diagnostic images. The implementation was carried out on a system equipped with a GTX 1650 GPU, an Intel Core i5 processor, 16 GB RAM, a 4 GB GPU, and an SSD for optimal performance. The kaggle dataset was separated into 70% for exercise and 30% for challenging to ensure comprehensive evaluation. As depicted in

Figure 2, the analysis included various diagnostic scans such as brain, lung, glaucoma, and cancer images obtained from Kaggle dataset using cloud packing. To validate the process, the clandestine copy was analyzed both earlier transmission and after reception by the planned recipient, ensuring minimal distortion of the original cover image after embedding the hidden image. The results of our proposed ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model is compared with the existing lightweight cryptography models such as advanced encryption standard (AES) [

36], PRESENT [

37], modular encryption standard algorithm (MESA) [

38], lightweight encryption algorithm (LEA) [

39], extended tiny encryption algorithm (XTEA) [

40], scalable encryption algorithm (SIMON) [

41], PRINCE [

42], RECTANGLE [

43], and RSA-AM+OBBO [

32].Performance metrics, including PSNR, MSE, BER, CC, and SSI, were used to measure the effectiveness of the proposed model. The best key was particular to divide the message into three equal parts based on maximum fitness, followed by encryption of the entire input.The performance of the proposed ultra-lightweight cryptographic algorithm for medicinal IoT plans is fully evaluated under normal conditions and in the presence of various security attacks to assess its strength. The evaluation considers various types of attacks to understand the vulnerability of the system. The ciphertext-only attack is tested where the attacker only has access to encrypted data and tries to gather meaningful information without knowing the actual data or key. Similarly, a known plain text attack is considered where the attacker takes the cipher and the corresponding plain text and tries to get the encryption key or decrypt the other data. Another major attack that has been tested is the selective plain text attack, in which the attacker is allowed to select specific plaintexts and control the corresponding technical terms that provide information about the encryption process. Testing also includes side-channel occurrences that exploit physical leaks (such as energy ingesting or electromagnetic emissions) in the encryption process to extract secret keys or sensitive data. The system is also tested against brute force attacks, where the attacker tests all possible keys to decrypt the data and measures how strong the encryption is against such a combined method. In addition, replay attacks are analyzed, where an assailantinterrupts and reuses encrypted data to disrupt message between IoT devices. This ensures that encryption can prevent such attempts at unauthorized data redistribution. Considering the resilience of the system to future threats, we are also investigating quantum computer-based attacks that can leverage traditional encryption methods. The system's resilience against man-in-the-middle attacks has also been tested, where attackers intercept and manipulate communications between devices, ensuring medical data is protected during transmission. The impact of high-demand flood attacks has also been assessed, which determines how well the encryption system performs under pressure. Finally, file integrity attacks are also considered, and the system's ability to maintain the reliability of medical data is tested when encrypted data cannot be detected, manipulated, or modified. Various attack scenarios help to test the effectiveness and security of encryption algorithms, ensuring that medical data is protected even in the most challenging situations.

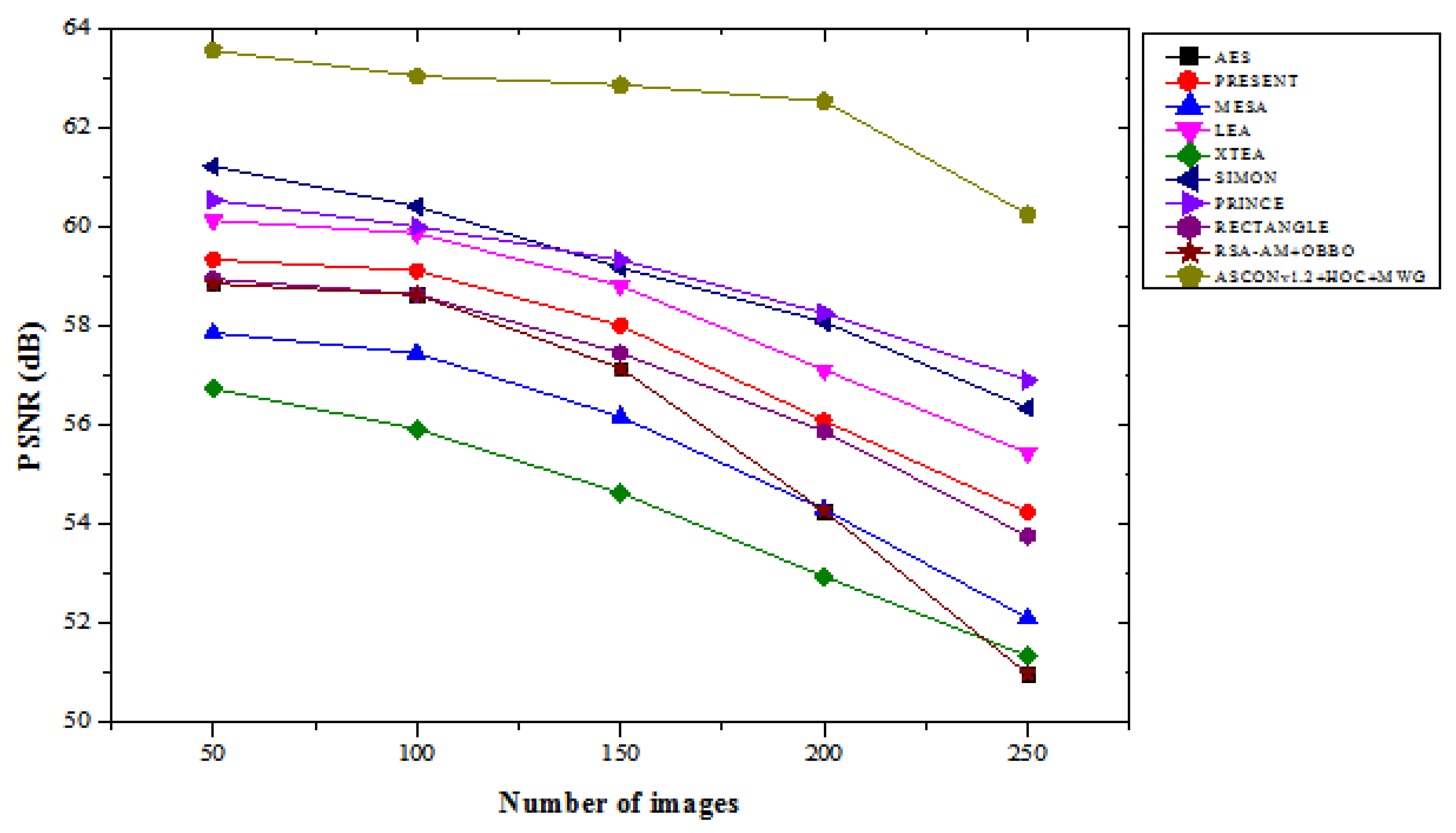

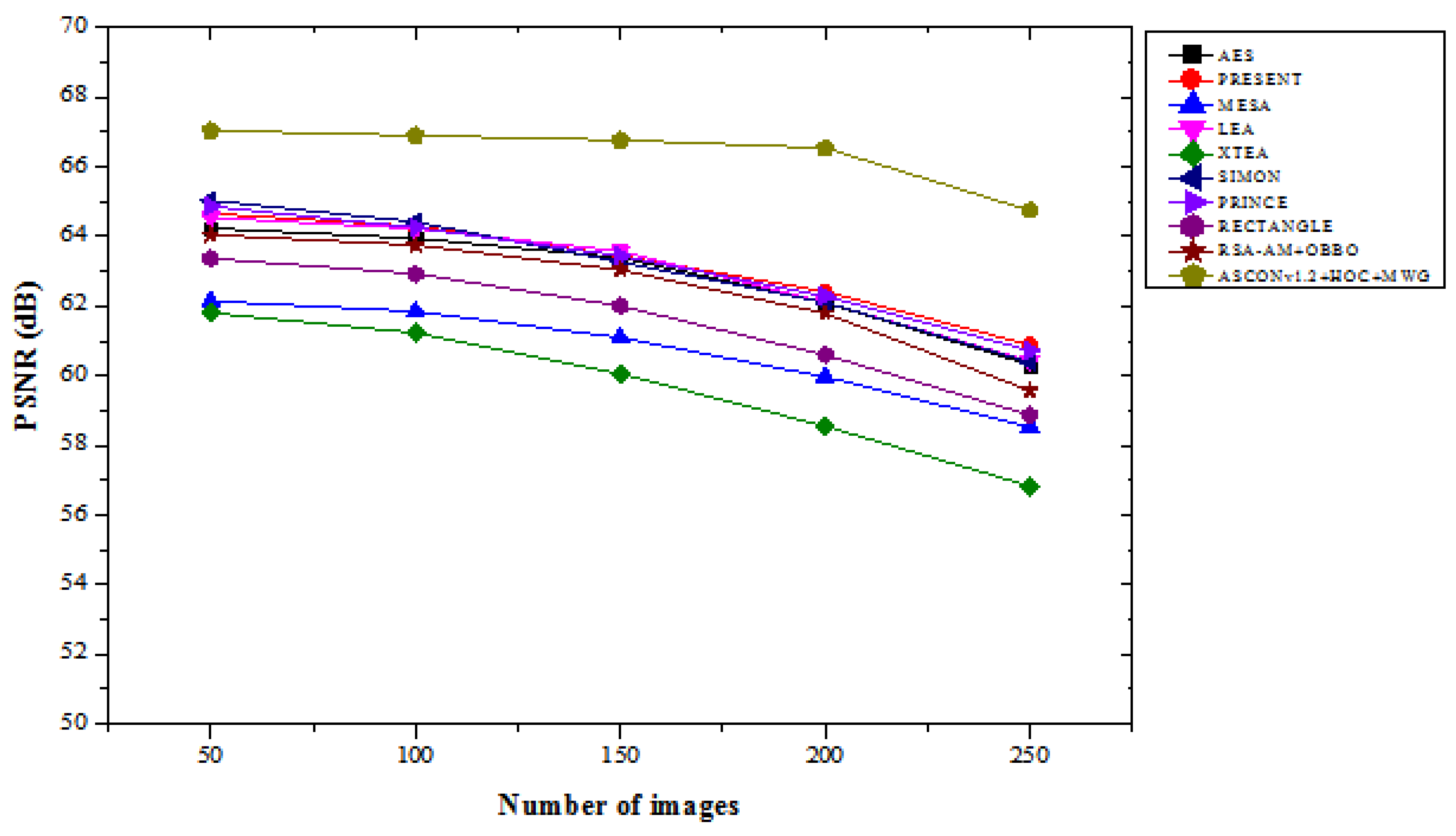

4.1. PSNR Results Analysis

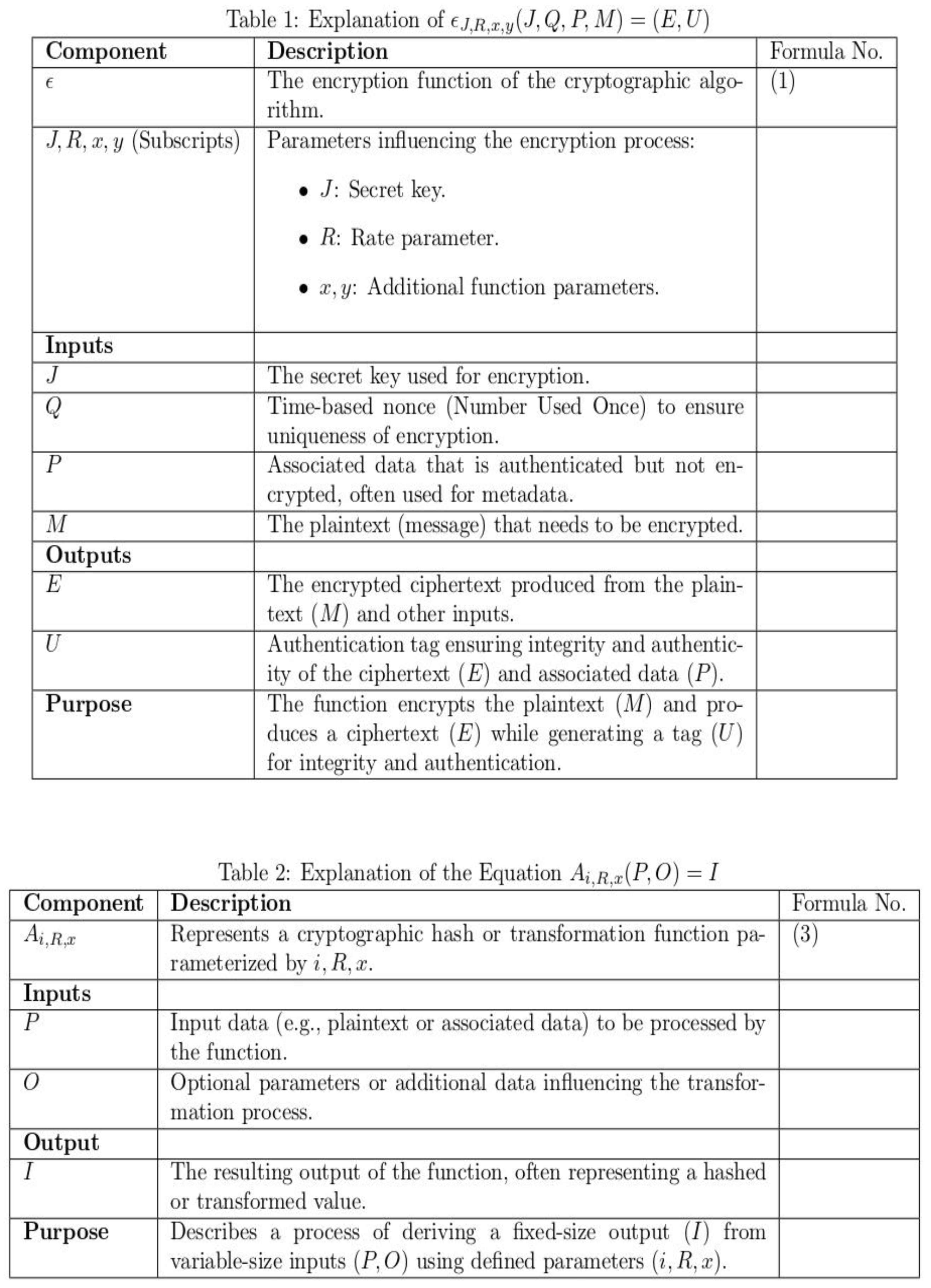

In both the “with attacks” and “without attacks” scenarios,

Table 1 compares the PSNR performance of the suggested ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model to that of current lightweight cryptographic methods over a range of image counts. In the “with attacks” scenario, the proposed ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model consistently delivers superior PSNR values, demonstrating its robustness against attacks. For 50 images, it achieves a PSNR of 63.568, representing an improvement of 4.05% compared to SIMON, which has a PSNR of 61.230, and 5.71% increase compared to LEA, which achieves 60.135.

For 250 images, ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG records a PSNR of 60.258, this is 6.93% higher than PRINCE with 56.907 and 8.93% better than RECTANGLE, which achieves 53.763. These improvements highlight the model’s ability to maintain higher image quality even under adversarial conditions. In the “without attacks” scenario, ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG shows even greater PSNR improvements over the other algorithms. For 50 images, it achieves a PSNR of 67.034, which is 3.08% higher than SIMON’s 65.027 and 3.88% better than PRINCE, which records 64.860. For 250 images, the proposed model achieves a PSNR of 64.743, representing a 6.42% improvement compared to SIMON, which has a PSNR of 60.395, and a 7.93% increase compared to AES with 60.312. The results show the effectiveness of ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG in delivering higher image quality when attacks are absent. The findings in

Figure 3and

Figure 4 confirm that the proposed model significantly outperforms existing lightweight cryptographic algorithms in both scenarios. The substantial improvements in PSNR values under attack conditions highlight the model's resilience and robustness, while the enhancements in attack-free scenarios emphasize its suitability for applications requiring high-quality image preservation. It makes proposed ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG reliable and efficient cryptographic solution.

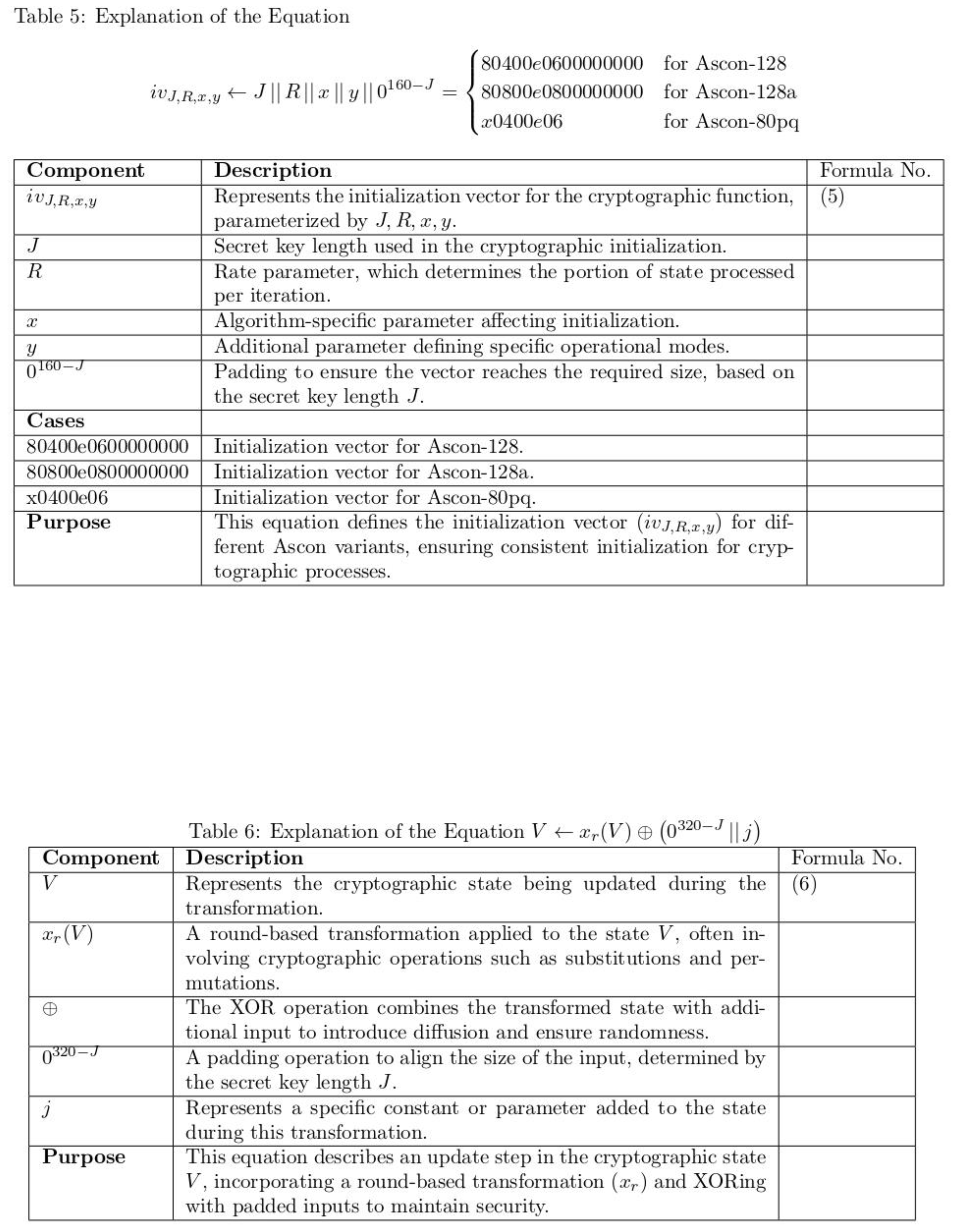

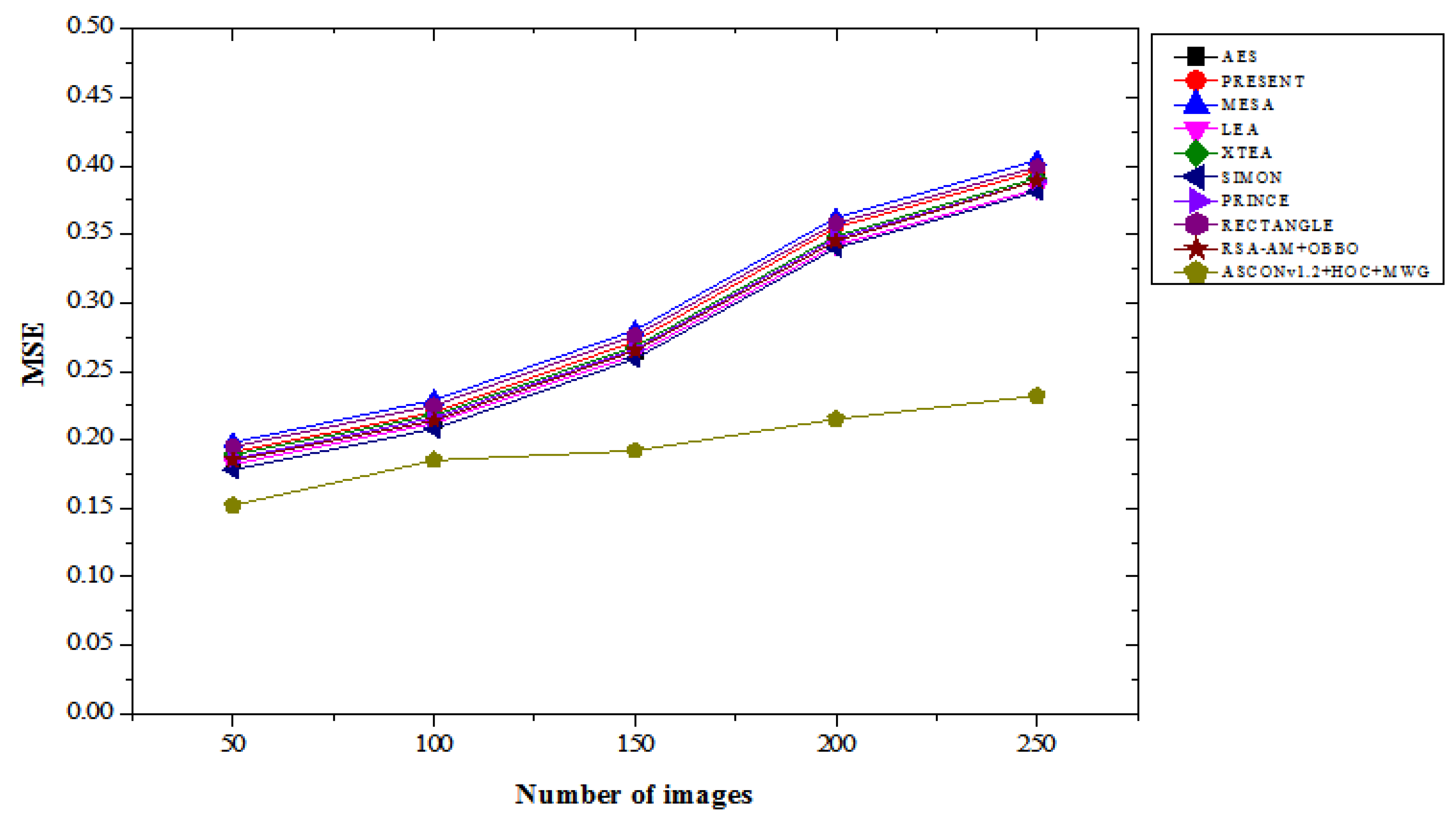

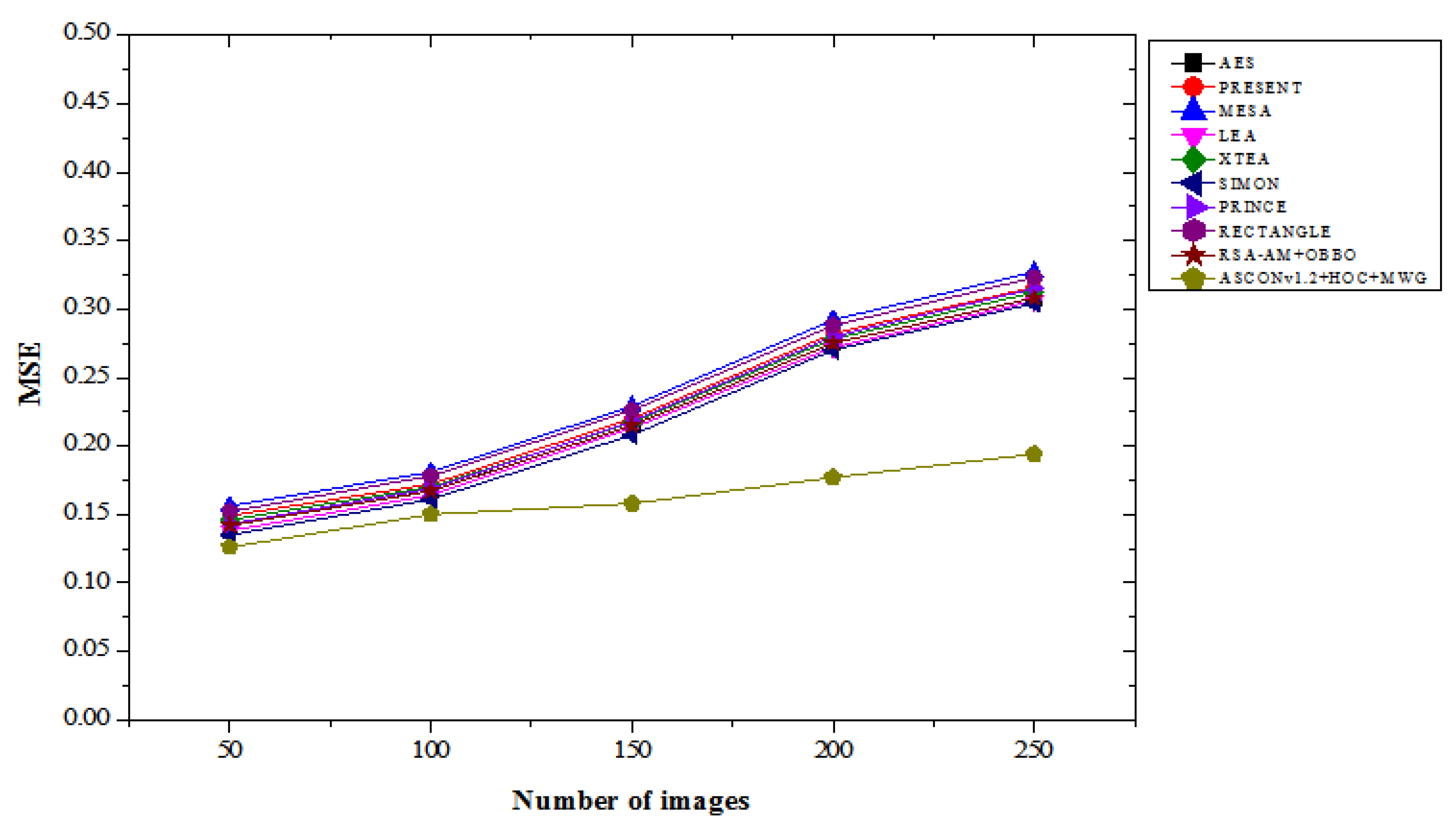

4.2. MSE Results Analysis

Table 2 illustrates the MSE performance comparison of the proposed ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model against existing lightweight cryptographic algorithms, evaluated across varying numbers of images under both “with attacks” and “without attacks” scenarios. The results highlight the proposed model's effectiveness in minimizing the MSE, showcasing its superiority in preserving image quality. In the with attacks scenario, the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model achieves the lowest MSE values across all image counts. For 50 images, the MSE is 0.152, representing a 14.61% improvement over SIMON, which achieves an MSE of 0.178, and 16.48% better than LEA, which records 0.182. As the number of images increases, the improvements remain consistent. For 250 images, ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG achieves an MSE of 0.232, which is 39.10% lower than RECTANGLE's 0.399 and 34.38% lower than MESA's 0.404. These significant reductions in MSE show the model’s robustness in mitigating image degradation under adversarial conditions. In the without attacks scenario, the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model also shows considerable performance gains. For 50 images, it achieves an MSE of 0.126, which is 6.67% better than SIMON’s 0.135 and 8.70% lower than LEA’s 0.138. For 250 images, the model achieves an MSE of 0.194, representing a 36.21% improvement compared to RECTANGLE's 0.323 and 40.67% better than MESA's 0.327. These results indicate that the proposed model is highly effective in preserving image quality in the absence of attacks, further solidifying its efficiency. The findings from

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 confirm that the proposed model significantly outperforms existing lightweight cryptographic algorithms in both attack and attack-free scenarios. The lower MSE values achieved by the proposed model highlight its superior ability to preserve the integrity and quality of images, making it a highly reliable cryptographic solution for applications requiring robust security and image fidelity.

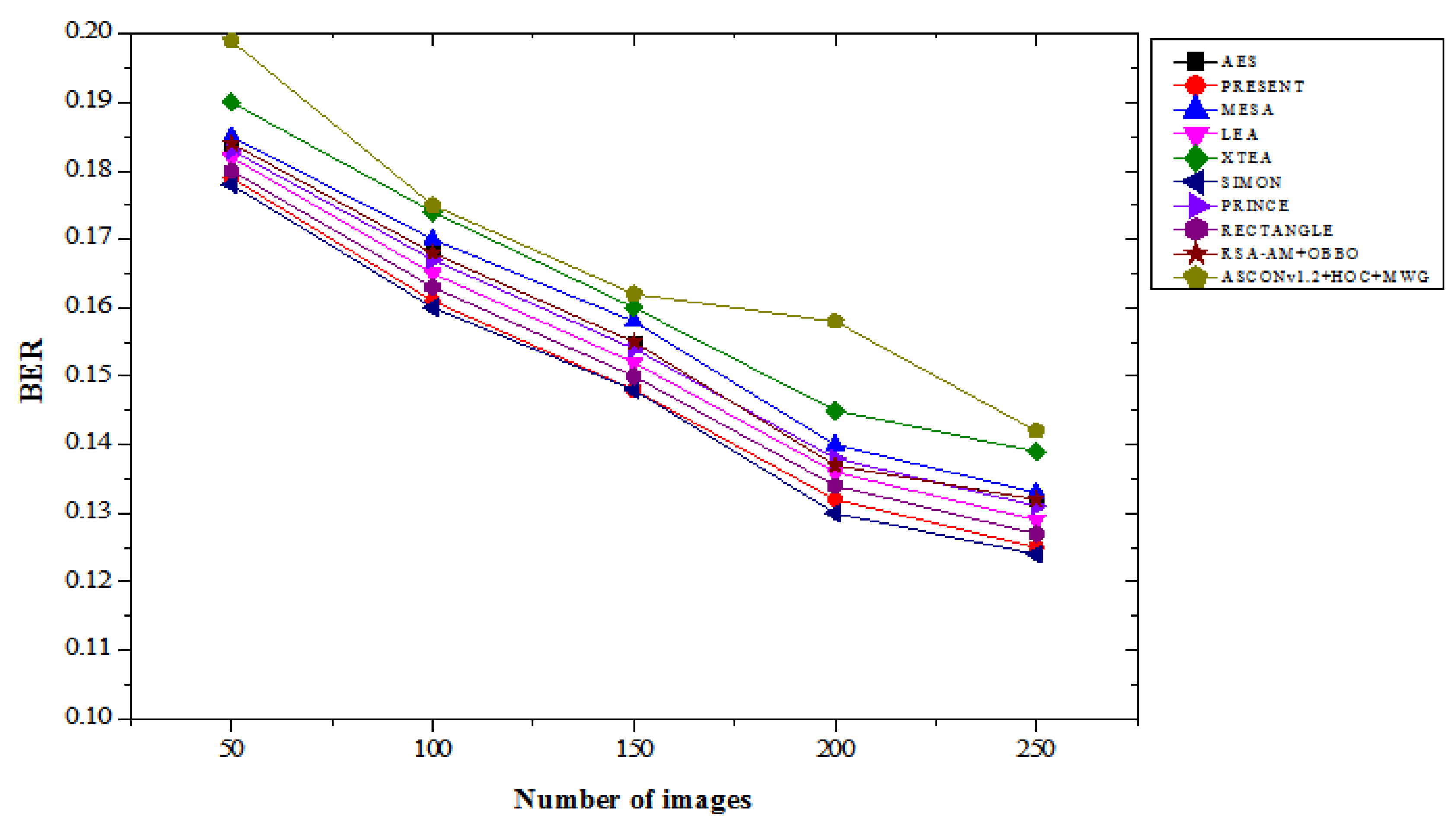

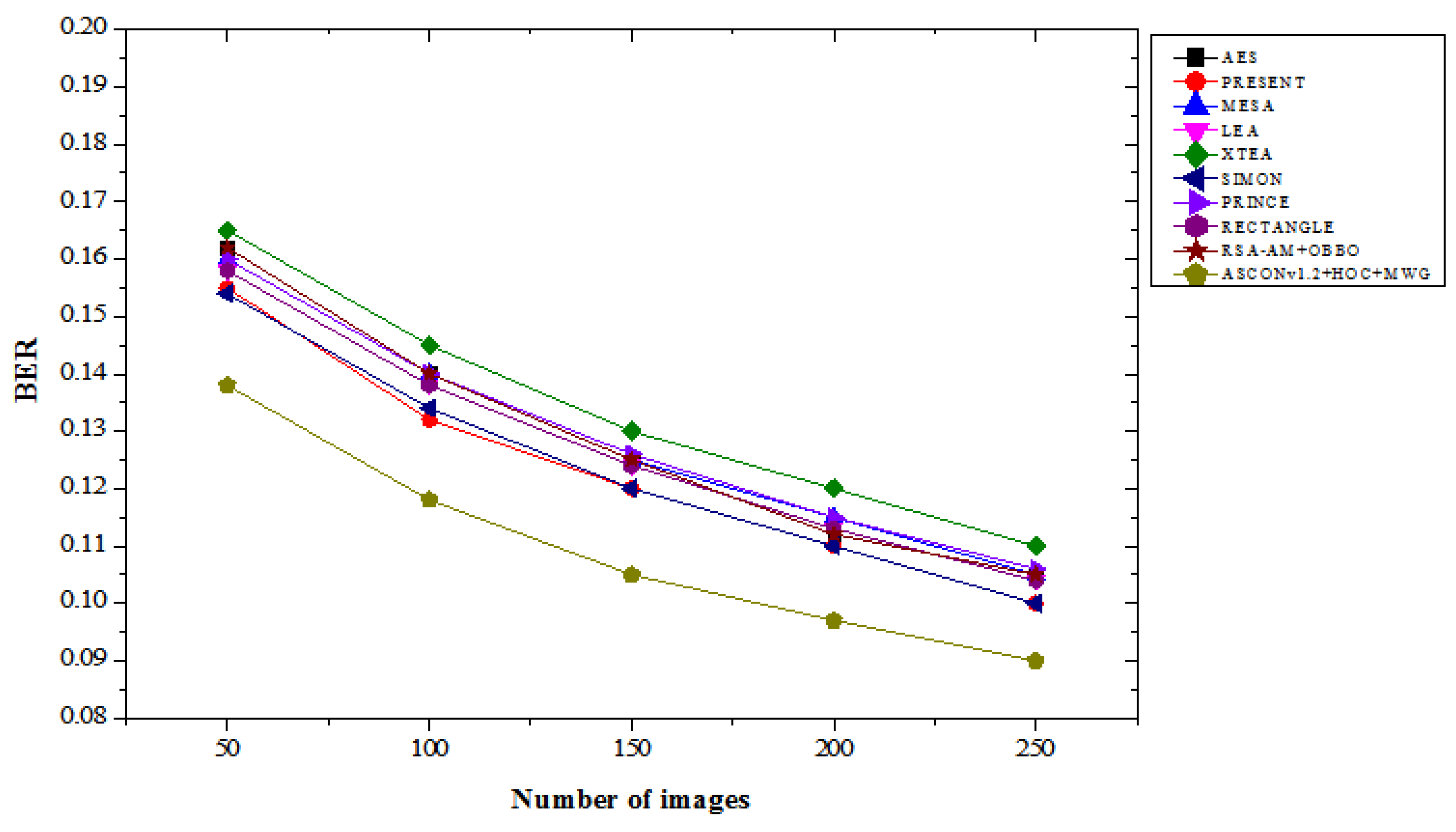

4.3. BER Results Analysis

Table 3 illustrates the BER performance comparison of the proposed ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model against existing lightweight cryptographic algorithms, evaluated with varying numbers of images under both “with attacks” and “without attacks” scenarios. The results demonstrate the proposed model's effectiveness in maintaining a lower BER, highlighting its reliability in both with and without attacks. In the with attacks scenario, the proposed ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model achieves a BER of 0.199 for 50 images, which is slightly higher than SIMON's 0.178, indicating a 10.67% increase. However, this performance gap narrows with an increasing number of images, shows the model's scalability. For 250 images, the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model records a BER of 0.142, representing a 14.52% reduction compared to XTEA's 0.139 and a 10.57% improvement over PRINCE's 0.131. In the “no attack” scenario, the proposed model invariably returns a lower BER compared to the existing algorithms. For 50 images, the ASCONv 1.2 + HOC + MWG model achieves a BER of 0.138, which represents a 10.39% improvement over XTEA's 0.165 and a 10.38% reduction over MESA's 0.160. As the numeral of images growths, the functionality of the planned model becomes clearer. For 250 images, the model achieves approximately 0.090 BER, which represents a 10.00% improvement compared to Simon's 0.100 and a 14.29% reduction compared to AES's 0,105. These results highlight the effectiveness of the model on data integrity in non-negative cases.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 confirm that the proposed model demonstrates competitive BER performance in ASCONv 1.2 + HOC + MWG attack scenarios and outperforms existing algorithms in non-attack scenarios.

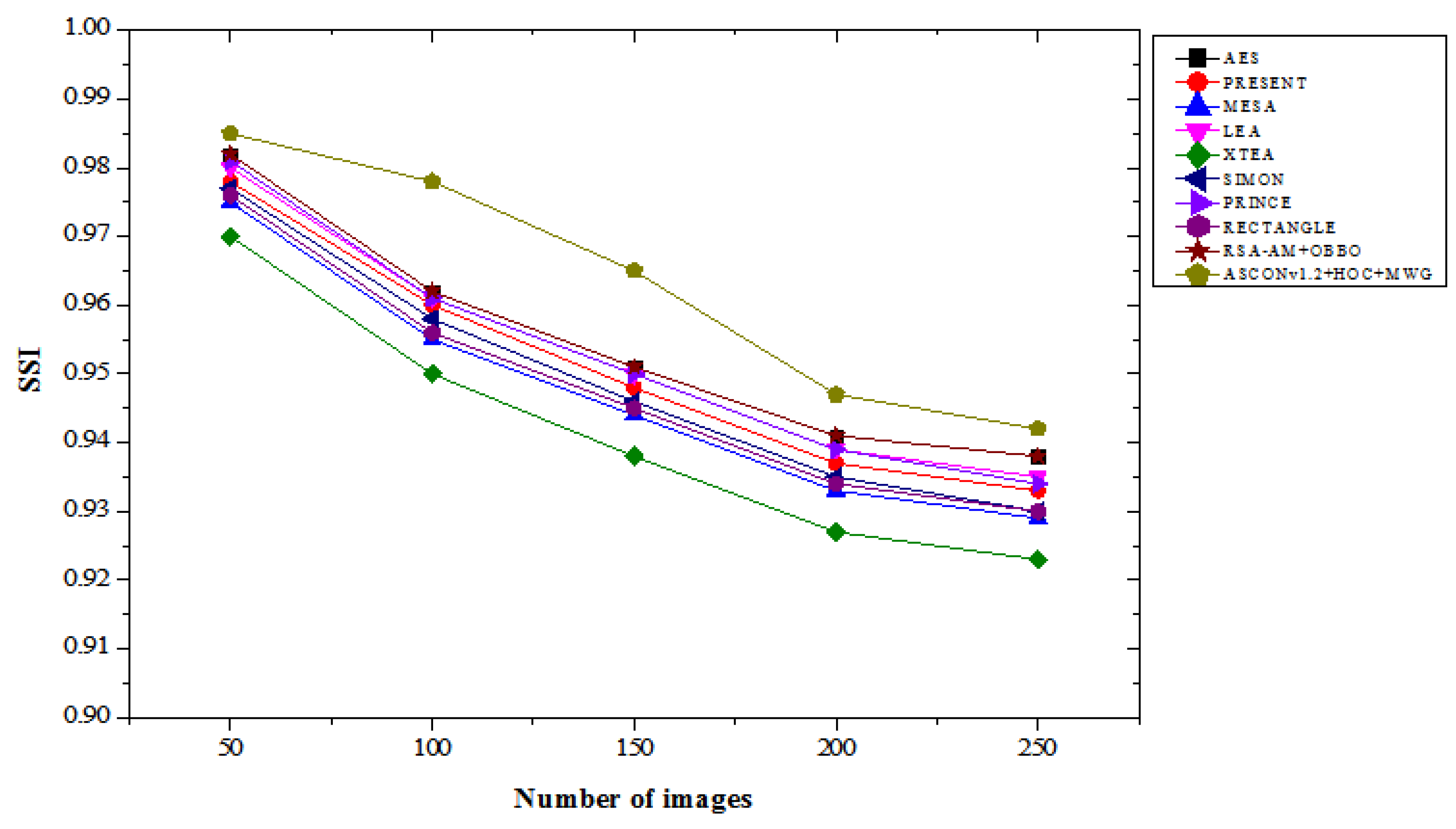

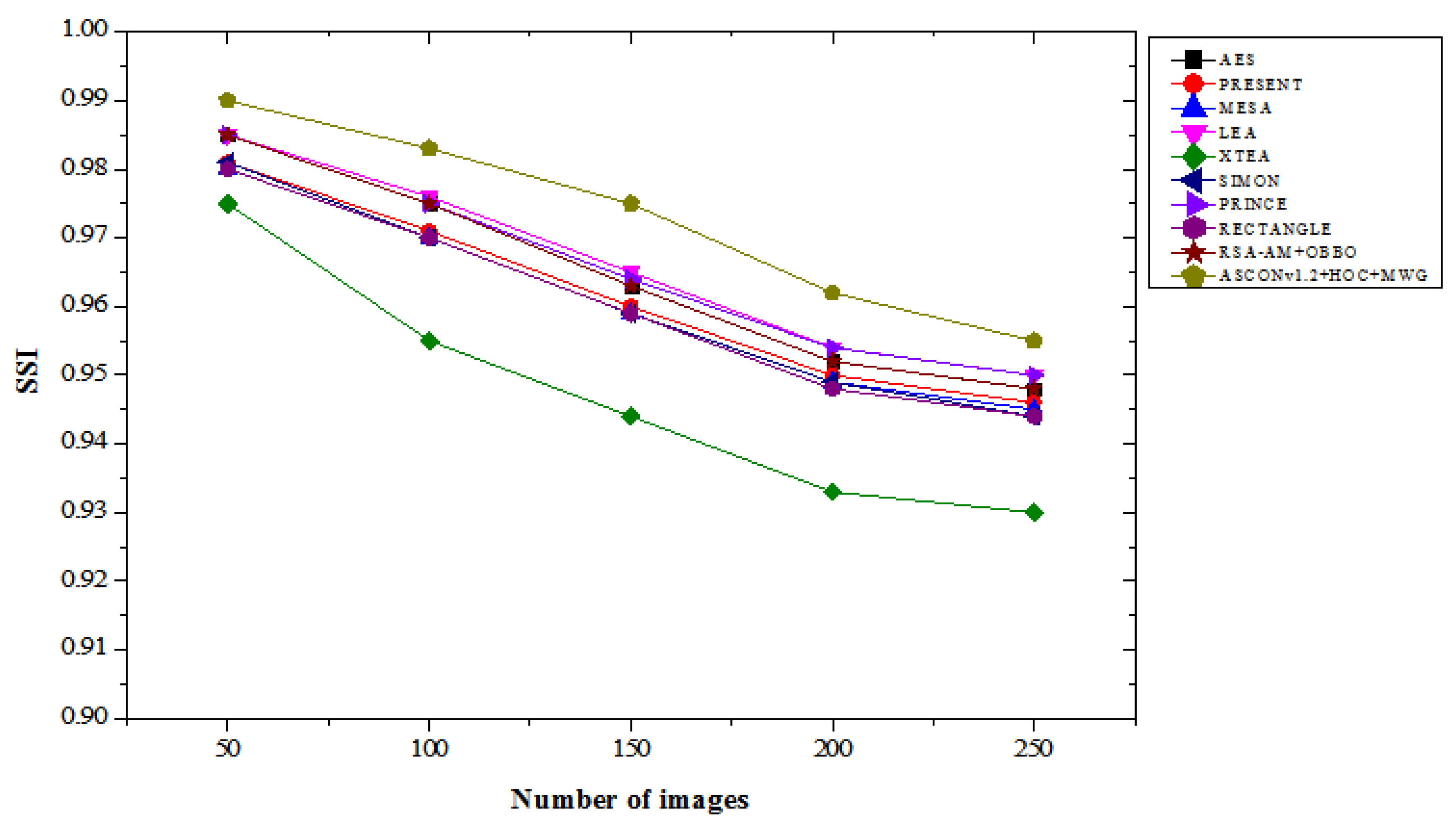

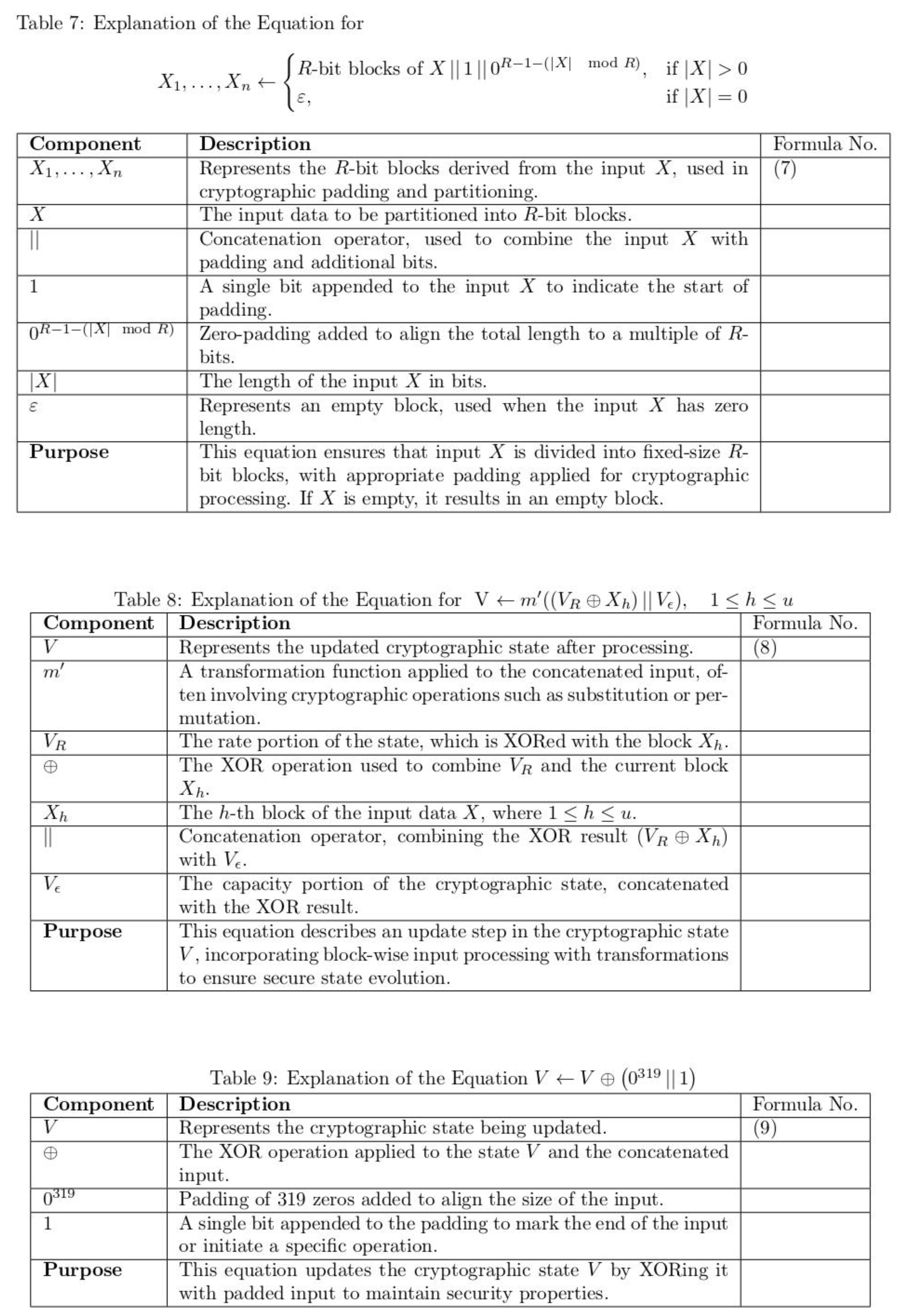

4.4. SSI Results Analysis

Table 4 provides a comparison of the performance of the Structural Similarity Index (SSI) of the proposed ASCONv 1.2 + HOC + MWG model compared to existing lightweight cryptographic algorithms, which are evaluated on a variable number of images in “attack” and “not attack” scenarios. These results highlight the potential of the proposed model to consistently achieve a high SSI value, offering better protection against structural integrity and image quality. In an attack scenario, the ASCONv 1.2 + HOC + MWG model showed a significant improvement compared to previous algorithms. For 50 images, it achieves an SSI of about 0.985, which is 0.31% higher than AES and RSA-AM + OBO, both 0.982 and 0.981, which are 0.41% higher than PRINCE. With the increase in the number of images, the superiority of ASCONv 1.2 + HOC + MWG becomes more apparent. For 250 images, achieving an SSI of 0.942, i.e. AES and RSA-AM + is a 0.86% improvement compared to OBO and XTEA. The results highlight that the proposed model is resilient to image production quality under attack conditions and has consistent structural consistency during each image production computation.

Table 4.

SSI result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

Table 4.

SSI result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

| Lightweight cryptography algorithms |

Number of images |

| 50 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

| |

With attacks |

| AES |

0.982 |

0.962 |

0.951 |

0.941 |

0.938 |

| PRESENT |

0.978 |

0.960 |

0.948 |

0.937 |

0.933 |

| MESA |

0.975 |

0.955 |

0.944 |

0.933 |

0.929 |

| LEA |

0.980 |

0.961 |

0.950 |

0.939 |

0.935 |

| XTEA |

0.970 |

0.950 |

0.938 |

0.927 |

0.923 |

| SIMON |

0.977 |

0.958 |

0.946 |

0.935 |

0.930 |

| PRINCE |

0.981 |

0.961 |

0.950 |

0.939 |

0.934 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.976 |

0.956 |

0.945 |

0.934 |

0.930 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.982 |

0.962 |

0.951 |

0.941 |

0.938 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.985 |

0.978 |

0.965 |

0.947 |

0.942 |

| |

Without attacks |

| AES |

0.985 |

0.975 |

0.963 |

0.952 |

0.948 |

| PRESENT |

0.981 |

0.971 |

0.960 |

0.950 |

0.946 |

| MESA |

0.980 |

0.970 |

0.959 |

0.949 |

0.945 |

| LEA |

0.985 |

0.976 |

0.965 |

0.954 |

0.950 |

| XTEA |

0.975 |

0.955 |

0.944 |

0.933 |

0.930 |

| SIMON |

0.981 |

0.970 |

0.959 |

0.949 |

0.944 |

| PRINCE |

0.985 |

0.975 |

0.964 |

0.954 |

0.950 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.980 |

0.970 |

0.959 |

0.948 |

0.944 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.985 |

0.975 |

0.963 |

0.952 |

0.948 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.990 |

0.983 |

0.975 |

0.962 |

0.955 |

Figure 9.

SSI results with attacks.

Figure 9.

SSI results with attacks.

Figure 10.

SSI results without attacks.

Figure 10.

SSI results without attacks.

Without an attack, the ASCONv 1.2 + HOC + MWG model significantly outperforms those models. Reaching an SSI of about 0.990 on 50 images, it's 0.51% better than AES, LEA, Prince, and RSA-AM + OBO, all of which are 0.985. For 250 images, the recommended model achieved an SSI of 0.955, which is 0.74% better than Prince and LE and 1.06% better than RECTANGLE and SIMON. These results demonstrate the model's performance under low-contrast conditions in determining structural integrity and image quality, and ensure its exceptional performance. Between Chapter 9 and Chapter 10, the proposed ASCONv 1.2 + HOC + MWG model is stable in both cases and provides a higher SSI value compared to existing lightweight cryptographic algorithms. This model shows exceptional performance in terms of structural integrity without attacks and exhibits very good resistance to attacks. This result confirms that the creation of high-quality images and the performance of secure encryption are essential for reliability and usability.

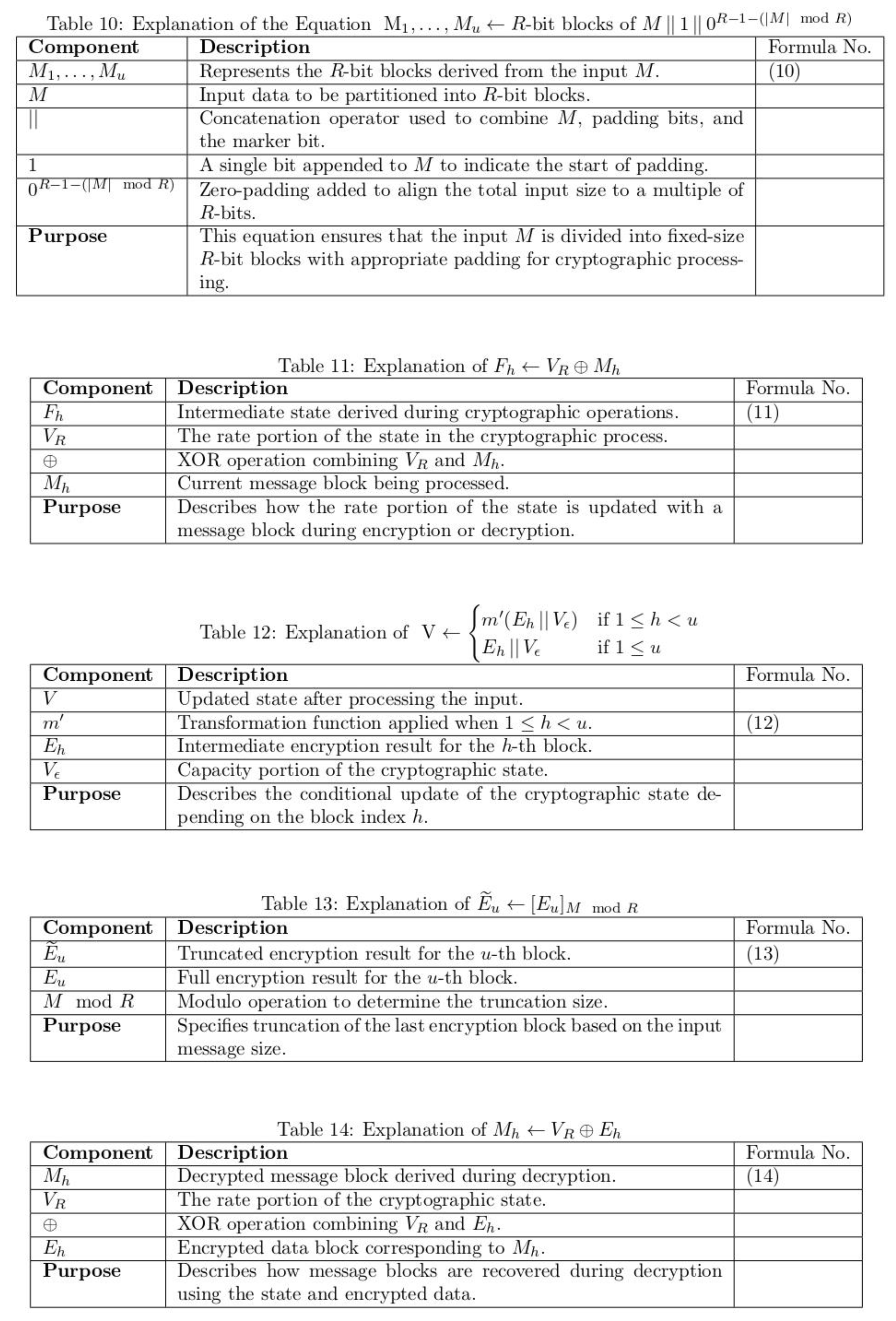

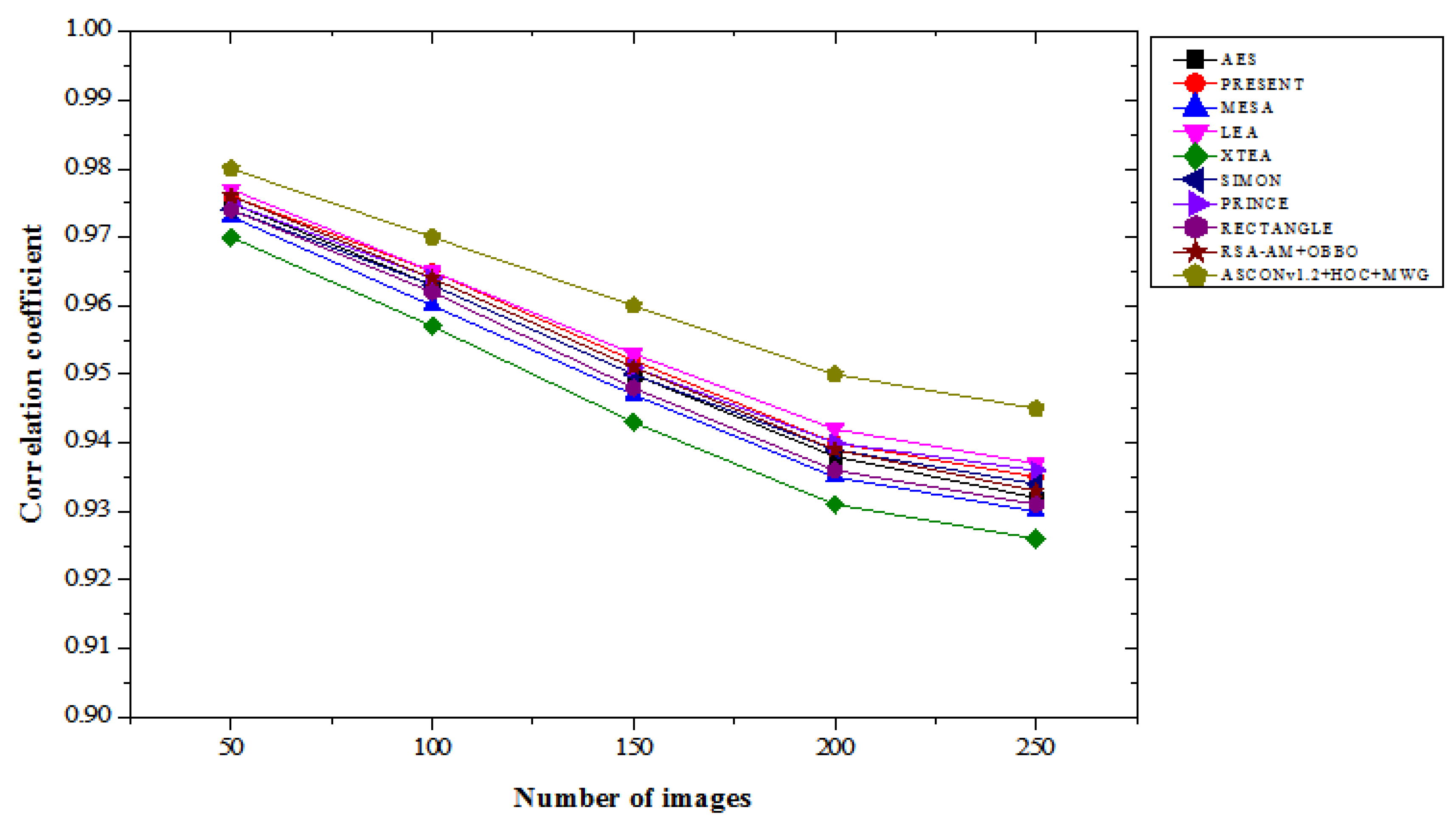

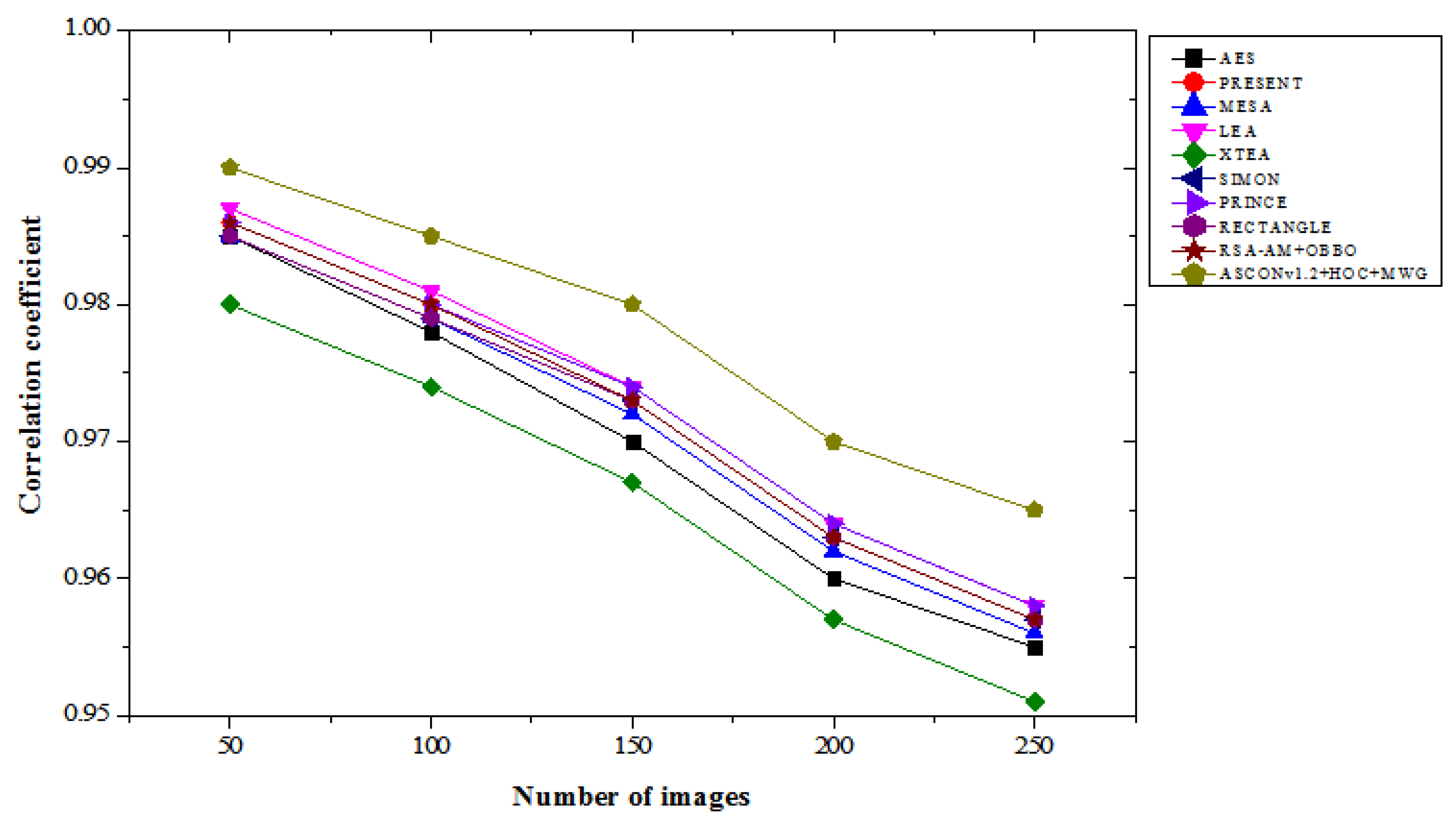

4.5. Correlation Coefficient Results Analysis

Table 5 provides a comparison of the correlation coefficient results for lightweight cryptographic algorithms across varying numbers of images in both “with attacks” and “without attacks” scenarios. Our ASCONv 1.2 + HOC + MWG model shows a high correlation coefficient, which indicates the ability to maintain excellent data integrity and correlation between encrypted and real images. With the attack, the ASCON 1.2 + HOC + MWG model achieved a correlation coefficient of 0.98 for 50 images, which represents an improvement of 0.31% and an improvement of 0.41% compared to the LEA. For 250 images, the planned model achieves a correlation coefficient of 0.945, which is 0.86% higher than XTEA, 1.61% higher than MESA, and 0.96% higher than RECTANGLE. The consequences demonstrate the specific model's resilience against attacks, in terms of protecting data interactions more effectively compared to current algorithms. In the absence of attacks, the performance of the ASCONv 1.2 + HOC + MWG model is quite impressive. For 50 images, this model achieves a correlation of 0.99, which represents a 0.31% improvement compared to LEA and PRINCE. Out of 250 images, this model has a correlation coefficient of 0.965, which is 1.47 percent higher than XTEA and 0.74 percent higher than PRESENT, SIMON, and RECTANGLE, with respective scores of 0.957. The results demonstrate the proposed model's ability to manage interactions under unfavourable conditions and outperform competitors in all images. From

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model shows superior correlation preservation in both scenarios. Its performance under attack conditions shows resilience, with a notable improvement over existing algorithms, and its performance without attacks emphasizes its capability to maintain near-perfect correlation. These findings validate the model's effectiveness for secure cryptographic applications requiring high data correlation integrity.

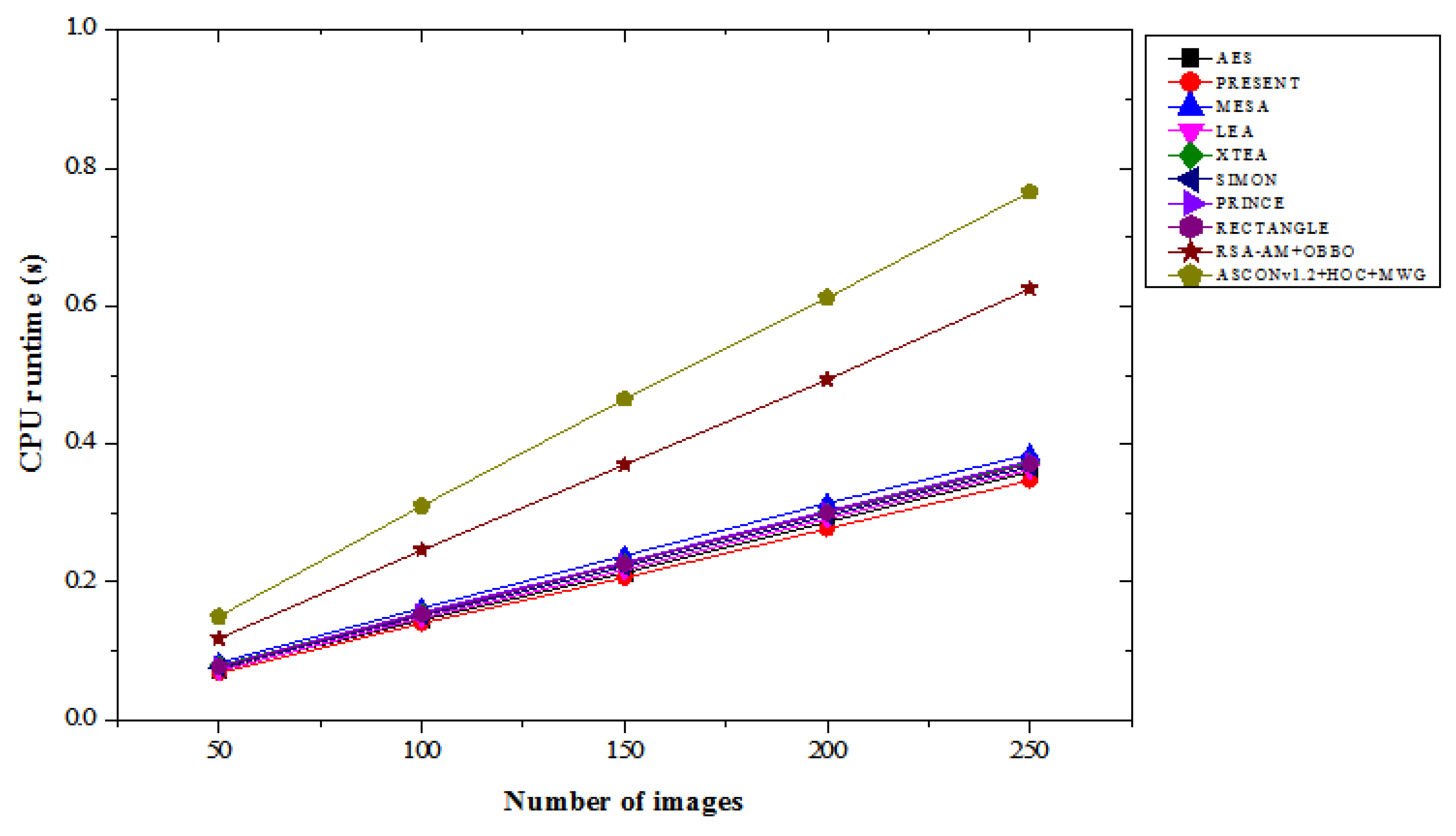

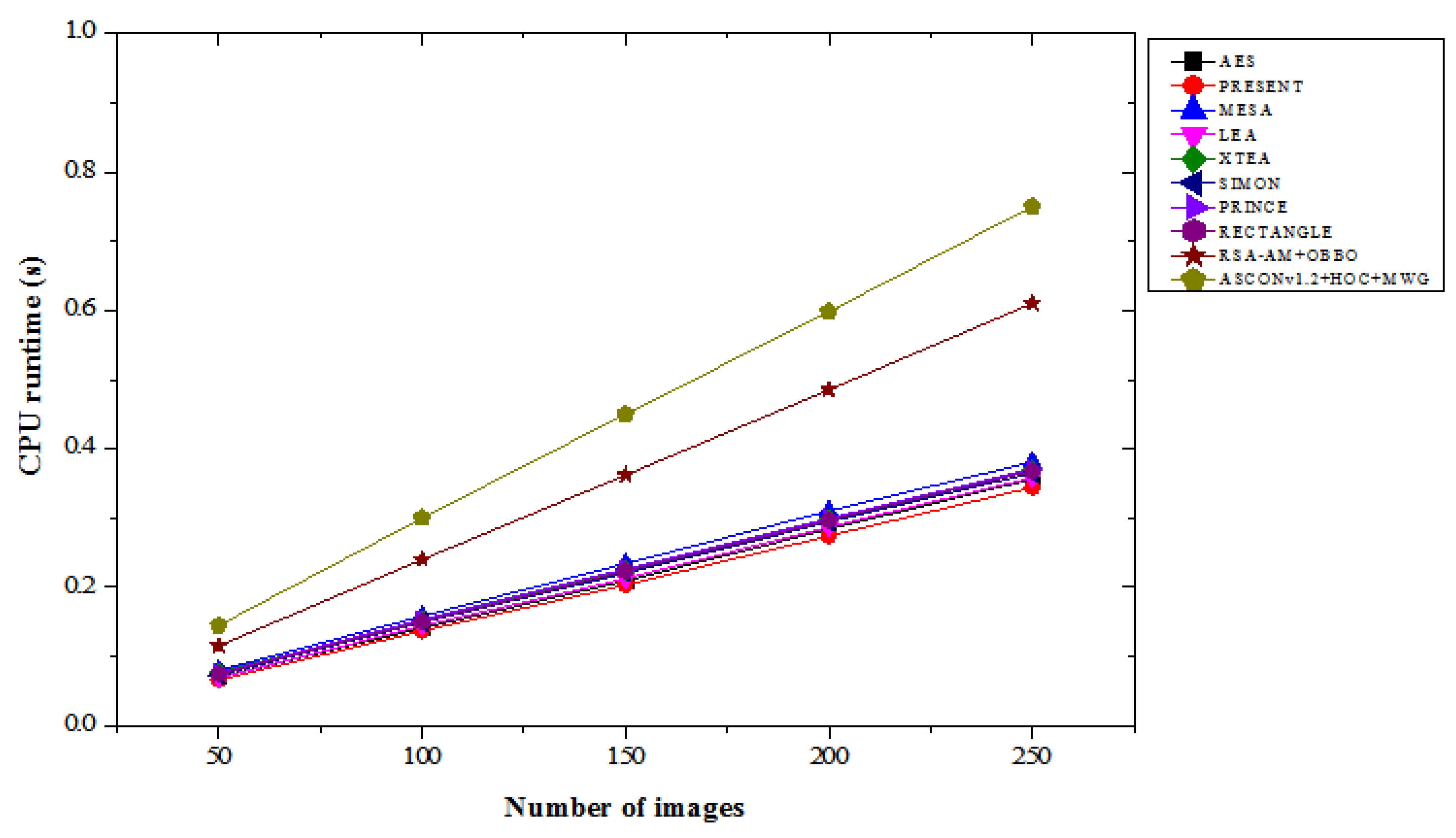

4.6. CPU Run Time Results Analysis

Table 6 compares the CPU runtime results of various lightweight cryptographic algorithms across different image count under “with attacks” and “without attacks” conditions. In the with attacks scenario, the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model exhibits the highest runtime values among all models, which is expected due to its advanced hybrid architecture providing enhanced security and performance trade-offs. For 50 images, its runtime is 0.150 seconds, which is a 103.45% increase compared to PRESENT and a 28.81% increase over RSA-AM+OBBO. At 250 images, ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG have a runtime of 0.765 seconds, which is 120.46% higher than PRESENT and 22.4% higher than RSA-AM+OBBO. The consistent increase in runtime reflects the computational complexity of the proposed model, optimized for robust security even in attack scenarios. In the without attacks scenario, a similar trend is observed, where the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model maintains higher runtimes compared to other algorithms. For 50 images, it requires 0.145 seconds, representing a 119.70% increase over PRESENT and a 26.09% increase over RSA-AM+OBBO. At 250 images, its runtime is 0.750 seconds, which is 118.02% higher than PRESENT and 22.95% greater than RSA-AM+OBBO. From

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, the results suggest that the computational overhead of the proposed model is consistent across both scenarios, delivering its advanced functionality at the cost of additional runtime. While the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model exhibits the longest runtimes, this is indicative of its superior cryptographic capabilities, which come with a trade-off in computational efficiency. The increased runtime can be justified by its ability to deliver enhanced security and robustness under both attack and non-attack conditions. The trade-off is particularly critical in applications where data security and integrity are prioritized over processing speed. This result underscores the model's suitability for scenarios requiring heightened security, even when dealing with large datasets.

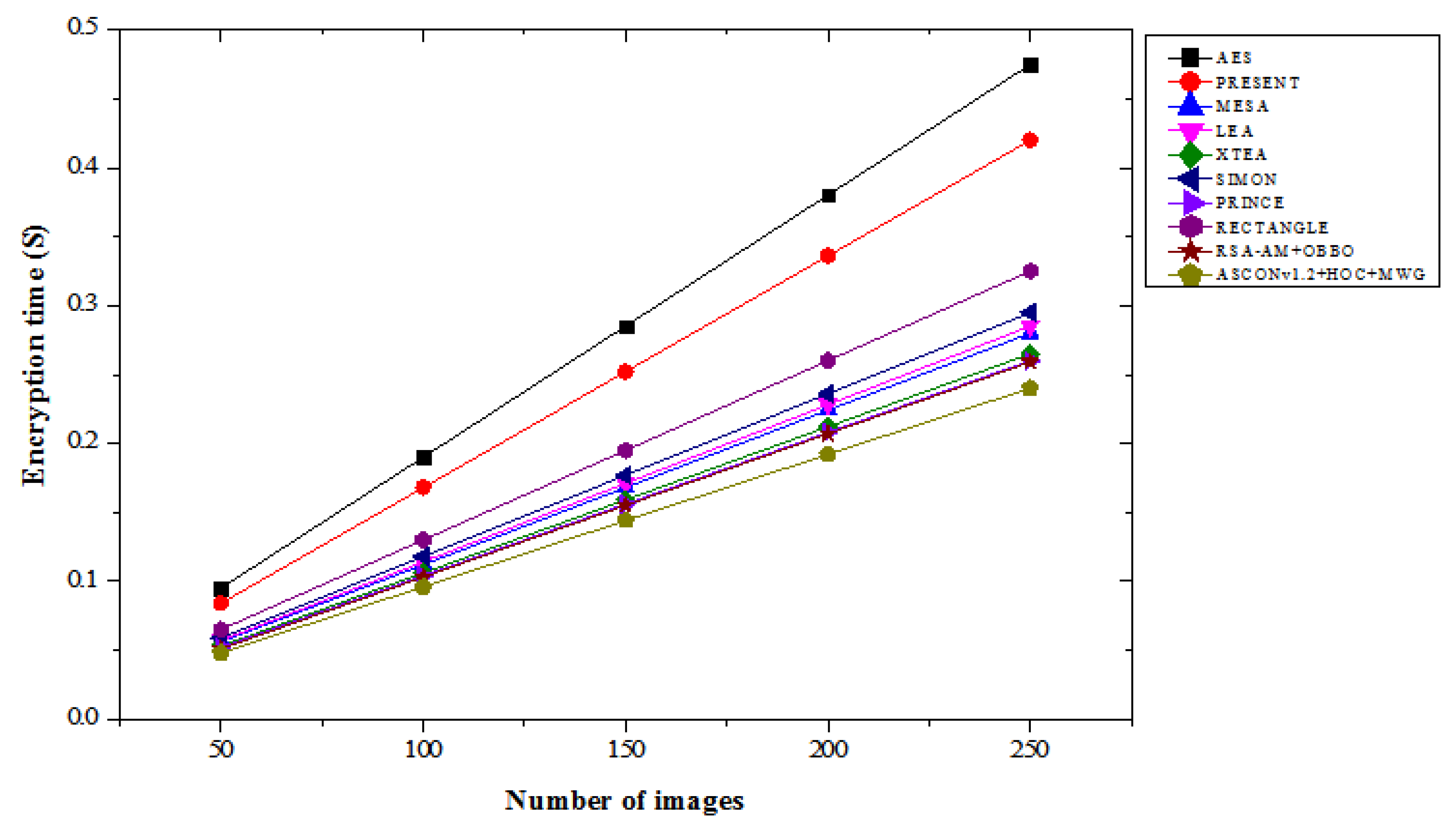

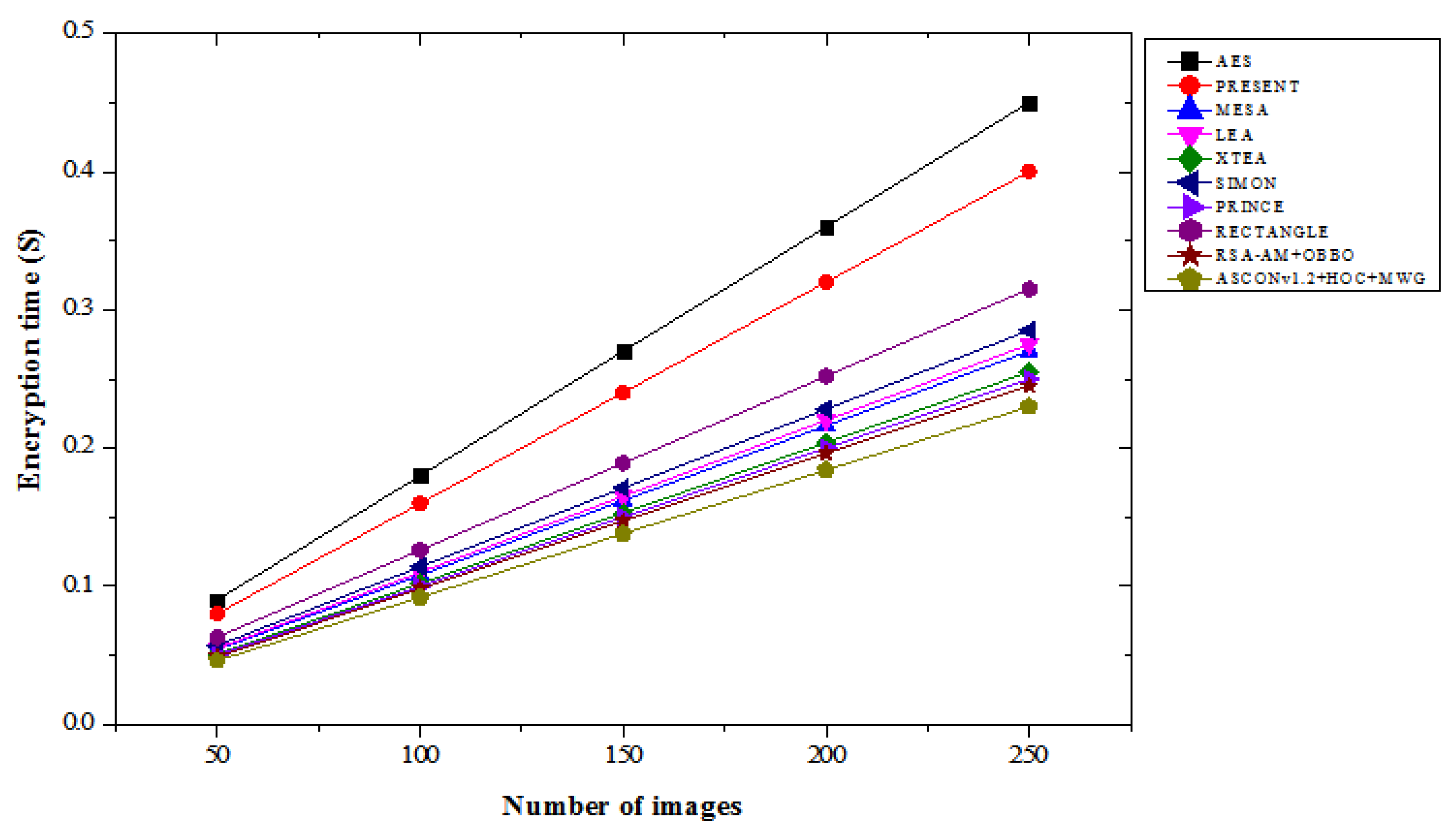

4.7. Encryption Time Results Analysis

Table 7 compares the encryption time results of various lightweight cryptographic algorithms across different image counts under both “with attacks” and “without attacks” conditions. In the with attacks scenario, the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model shows consistently faster encryption times compared to other algorithms. For 50 images, its encryption time is 0.048 seconds, which is 43.40% faster than AES and 5.88% faster than RSA-AM+OBBO. As the number of images increases, the time difference persists, with the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model taking 0.240 seconds at 250 images, which is 49.47% faster than AES and 7.32% faster than RSA-AM+OBBO.

The model outperforms existing algorithms in terms of encryption speed, which highlights its efficiency, even in attack scenarios. In without attacks scenario, the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model continues to show superior performance. At 50 images, encryption time is 0.046 seconds, 48.89% faster than AES and 6.12% faster than RSA-AM+OBBO. For 250 images, the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model completes encryption in 0.230 seconds, which is 48.89% faster than AES and 6.12% faster than RSA-AM+OBBO. As shown in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, our proposed model maintains its advantage over other cryptographic methods in both attack and non-attack scenarios, emphasizing its optimized encryption time. The ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model consistently outperforms AES, PRESENT, and RSA-AM+OBBO in terms of encryption time, both with and without attacks. The faster encryption times across all tested image sizes suggest that the proposed model is not only secure but also highly efficient in terms of computational performance. The ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model offers a superior balance between speed and security, making it appropriate for applications where real-time encryption is crucial, including data transfer in security-sensitive situations, even if AES and RSA-AM+OBBO offer strong encryption. This efficiency is crucial for maintaining high throughput while ensuring data security.

4.8. Results Comparison of Proposed and Existing Lightweight Crypto Algorithm

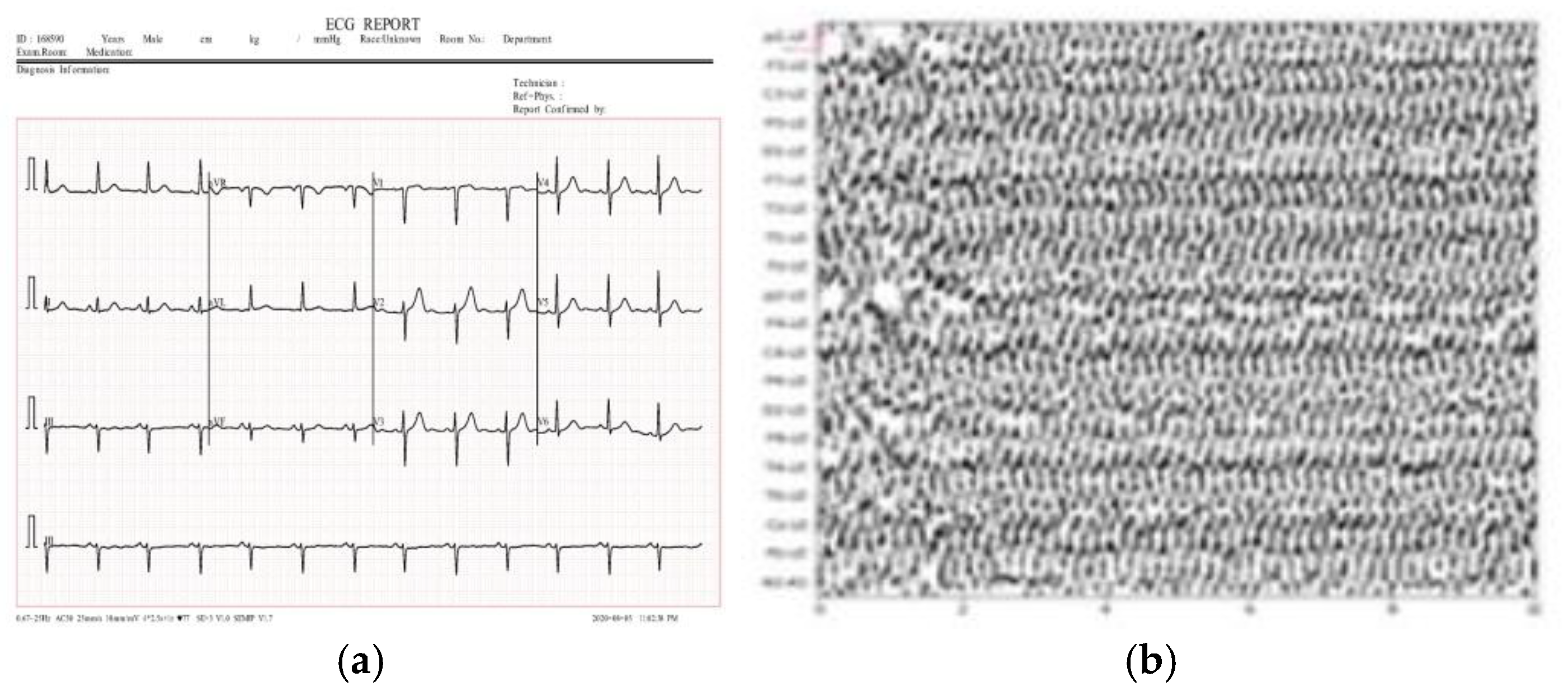

This section evaluates the performance of the proposed and existing lightweight cryptographic algorithms using various metrics, including the number of pixel changing rate (NPCR), unified averaged changed intensity (UACI), and cross-entropy. Medical images, such as ECG, EEG, MRI, and X-ray scans, were used as inputs for the proposed method.

Figure 17 illustrates sample medical images utilized in the analysis. The results presented in

Table 8 demonstrate that the proposed lightweight cryptographic algorithm (ASCONv1.2 + HOC + MWG) outperforms the existing CTE + Dynamic Chaotic model[

32] across all metrics for encrypted images. For NPCR, the proposed model achieves percentage improvements ranging from 0.076% to 0.085%, indicating enhanced sensitivity to pixel changes. Similarly, the UACI values exhibit an improvement, with increases ranging from 2.82% for ECG images to 5.70% for X-Ray images, reflecting better intensity variation in the encrypted data. Cross-entropy, a measure of randomness and security, also shows very high improvement. These enhancements highlight the proposed algorithm's superior encryption quality and robustness. In

Table 9, the results for decrypted images indicate that both the proposed and existing algorithms achieve perfect decryption, as evidenced by NPCR, UACI, and cross-entropy values of 0 across all image types. This shows that both algorithms are capable of accurately restoring the original images without any distortion, ensuring high reliability in decryption. The proposed ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG algorithm demonstrates improved encryption performance, with notable improvement in NPCR, UACI, and cross-entropy metrics, while maintaining flawless decryption capability. This makes it a more effective and secures option for lightweight cryptographic applications in medical imaging.

The complexity analysis presented in

Table 10 reveals the comparative strengths of the CTE+dynamic chaotic model and the proposed ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model. In terms of time complexity, the CTE+dynamic chaotic model exhibits O(m⋅n), where m is the number of pixels and n is the number of iterations for chaotic key generation. ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model optimizes this with a time complexity of O(k⋅b+n+k⋅logk), where k is the number of blocks, b is the block size, and n represents the key generation cost. By utilizing block-based processing and efficient graph traversal with a logarithmic factor, the proposed model reduces the computational burden, particularly for larger images, making it more efficient and scalable. Regarding space complexity, the CTE+dynamic chaotic model requires O(m+n) space, which accounts for the storage of the image data, chaotic parameters, and keys. While this space usage is reasonable, it is relatively less optimized. On the other hand, the ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model has a space complexity of O(m+n+k), where the additional term k comes from the storage required for graph-based operations. Although this results in slightly higher space complexity, the increased efficiency of the encryption process compensates for this, as the graph storage is lightweight and aids in faster encryption. ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG model provides notable improvements in both time and space complexity over the CTE+dynamic chaotic model. By reducing computational overhead with block-based processing and leveraging more efficient graph traversal, the proposed model enhances overall performance, particularly for larger images or real-time applications. Despite the slight increase in space complexity due to the graph storage, the proposed model remains highly efficient, making it a more suitable choice for lightweight cryptographic applications in environments with constrained resources.

Figure 1.

Conceptual structure of ultra-lightweight cryptography algorithm for medical IoT devices to enhance healthcare security.

Figure 1.

Conceptual structure of ultra-lightweight cryptography algorithm for medical IoT devices to enhance healthcare security.

Figure 2.

Test images form Kaggle dataset (a) MRI images (b) Iris images (c) ultrasound images (d) CT images.

Figure 2.

Test images form Kaggle dataset (a) MRI images (b) Iris images (c) ultrasound images (d) CT images.

Figure 3.

PSNR results with attacks.

Figure 3.

PSNR results with attacks.

Figure 4.

PSNR results without attacks.

Figure 4.

PSNR results without attacks.

Figure 5.

MSE results with attacks.

Figure 5.

MSE results with attacks.

Figure 6.

MSE results without attacks.

Figure 6.

MSE results without attacks.

Figure 7.

BER results with attacks.

Figure 7.

BER results with attacks.

Figure 8.

BER results without attacks.

Figure 8.

BER results without attacks.

Figure 11.

Correlation coefficient results with attacks.

Figure 11.

Correlation coefficient results with attacks.

Figure 12.

Correlation coefficient results without attacks.

Figure 12.

Correlation coefficient results without attacks.

Figure 13.

CPU runtime results with attacks.

Figure 13.

CPU runtime results with attacks.

Figure 14.

CPU runtime results without attacks.

Figure 14.

CPU runtime results without attacks.

Figure 15.

Encryption time results with attacks.

Figure 15.

Encryption time results with attacks.

Figure 16.

Encryption time results without attacks.

Figure 16.

Encryption time results without attacks.

Figure 17.

Test samples of medical images (a) ECG (b) EEG (c) MRI and (d) X-ray.

Figure 17.

Test samples of medical images (a) ECG (b) EEG (c) MRI and (d) X-ray.

Table 1.

PSNR result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

Table 1.

PSNR result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

| Lightweight cryptography algorithms |

Number of images |

| 50 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

| |

With attacks |

| AES |

58.858 |

58.635 |

57.152 |

54.274 |

50.985 |

| PRESENT |

59.342 |

59.120 |

58.013 |

56.095 |

54.239 |

| MESA |

57.865 |

57.453 |

56.172 |

54.298 |

52.110 |

| LEA |

60.135 |

59.874 |

58.823 |

57.122 |

55.441 |

| XTEA |

56.743 |

55.922 |

54.637 |

52.945 |

51.340 |

| SIMON |

61.230 |

60.421 |

59.186 |

58.087 |

56.347 |

| PRINCE |

60.548 |

60.014 |

59.338 |

58.264 |

56.907 |

| RECTANGLE |

58.953 |

58.647 |

57.458 |

55.872 |

53.763 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

58.858 |

58.635 |

57.152 |

54.274 |

50.985 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

63.568 |

63.054 |

62.878 |

62.545 |

60.258 |

| |

Without attacks |

| AES |

64.232 |

63.945 |

63.387 |

62.095 |

60.312 |

| PRESENT |

64.645 |

64.290 |

63.443 |

62.410 |

60.885 |

| MESA |

62.140 |

61.845 |

61.089 |

59.963 |

58.532 |

| LEA |

64.533 |

64.220 |

63.574 |

62.105 |

60.420 |

| XTEA |

61.795 |

61.231 |

60.056 |

58.552 |

56.832 |

| SIMON |

65.027 |

64.412 |

63.263 |

62.104 |

60.395 |

| PRINCE |

64.860 |

64.254 |

63.437 |

62.288 |

60.716 |

| RECTANGLE |

63.360 |

62.924 |

62.003 |

60.597 |

58.872 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

64.040 |

63.753 |

63.034 |

61.793 |

59.567 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

67.034 |

66.890 |

66.762 |

66.531 |

64.743 |

Table 2.

MSE result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

Table 2.

MSE result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

| Lightweight cryptography algorithms |

Number of images |

| 50 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

| |

With attacks |

| AES |

0.185 |

0.214 |

0.265 |

0.345 |

0.389 |

| PRESENT |

0.191 |

0.22 |

0.272 |

0.355 |

0.396 |

| MESA |

0.198 |

0.229 |

0.28 |

0.362 |

0.404 |

| LEA |

0.182 |

0.212 |

0.262 |

0.342 |

0.383 |

| XTEA |

0.189 |

0.218 |

0.268 |

0.349 |

0.391 |

| SIMON |

0.178 |

0.208 |

0.259 |

0.34 |

0.381 |

| PRINCE |

0.186 |

0.216 |

0.266 |

0.347 |

0.389 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.195 |

0.225 |

0.276 |

0.358 |

0.399 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.185 |

0.214 |

0.265 |

0.345 |

0.389 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.152 |

0.185 |

0.192 |

0.215 |

0.232 |

| |

Without attacks |

| AES |

0.142 |

0.167 |

0.215 |

0.275 |

0.308 |

| PRESENT |

0.149 |

0.172 |

0.22 |

0.282 |

0.316 |

| MESA |

0.156 |

0.181 |

0.229 |

0.292 |

0.327 |

| LEA |

0.138 |

0.164 |

0.213 |

0.272 |

0.306 |

| XTEA |

0.146 |

0.17 |

0.217 |

0.278 |

0.312 |

| SIMON |

0.135 |

0.161 |

0.208 |

0.27 |

0.304 |

| PRINCE |

0.143 |

0.169 |

0.218 |

0.28 |

0.315 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.152 |

0.178 |

0.226 |

0.288 |

0.323 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.142 |

0.167 |

0.215 |

0.275 |

0.308 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.126 |

0.15 |

0.158 |

0.177 |

0.194 |

Table 3.

BER result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

Table 3.

BER result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

| Lightweight cryptography algorithms |

Number of images |

| 50 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

| |

With attacks |

| AES |

0.184 |

0.168 |

0.155 |

0.137 |

0.132 |

| PRESENT |

0.179 |

0.161 |

0.148 |

0.132 |

0.125 |

| MESA |

0.185 |

0.170 |

0.158 |

0.140 |

0.133 |

| LEA |

0.182 |

0.165 |

0.152 |

0.136 |

0.129 |

| XTEA |

0.190 |

0.174 |

0.160 |

0.145 |

0.139 |

| SIMON |

0.178 |

0.160 |

0.148 |

0.130 |

0.124 |

| PRINCE |

0.183 |

0.167 |

0.154 |

0.138 |

0.131 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.180 |

0.163 |

0.150 |

0.134 |

0.127 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.184 |

0.168 |

0.155 |

0.137 |

0.132 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.199 |

0.175 |

0.162 |

0.158 |

0.142 |

| |

Without attacks |

| AES |

0.162 |

0.140 |

0.125 |

0.112 |

0.105 |

| PRESENT |

0.155 |

0.132 |

0.120 |

0.110 |

0.100 |

| MESA |

0.160 |

0.140 |

0.125 |

0.115 |

0.105 |

| LEA |

0.158 |

0.138 |

0.124 |

0.113 |

0.104 |

| XTEA |

0.165 |

0.145 |

0.130 |

0.120 |

0.110 |

| SIMON |

0.154 |

0.134 |

0.120 |

0.110 |

0.100 |

| PRINCE |

0.160 |

0.140 |

0.126 |

0.115 |

0.106 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.158 |

0.138 |

0.124 |

0.113 |

0.104 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.162 |

0.140 |

0.125 |

0.112 |

0.105 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.138 |

0.118 |

0.105 |

0.097 |

0.090 |

Table 5.

Correlation coefficient result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

Table 5.

Correlation coefficient result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

| Lightweight cryptography algorithms |

Number of images |

| 50 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

| |

With attacks |

| AES |

0.975 |

0.963 |

0.95 |

0.938 |

0.932 |

| PRESENT |

0.976 |

0.965 |

0.952 |

0.94 |

0.935 |

| MESA |

0.973 |

0.96 |

0.947 |

0.935 |

0.93 |

| LEA |

0.977 |

0.965 |

0.953 |

0.942 |

0.937 |

| XTEA |

0.97 |

0.957 |

0.943 |

0.931 |

0.926 |

| SIMON |

0.974 |

0.963 |

0.95 |

0.939 |

0.934 |

| PRINCE |

0.975 |

0.964 |

0.951 |

0.94 |

0.936 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.974 |

0.962 |

0.948 |

0.936 |

0.931 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.976 |

0.964 |

0.951 |

0.939 |

0.933 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.98 |

0.97 |

0.96 |

0.95 |

0.945 |

| |

Without attacks |

| AES |

0.985 |

0.978 |

0.97 |

0.96 |

0.955 |

| PRESENT |

0.986 |

0.98 |

0.973 |

0.963 |

0.957 |

| MESA |

0.985 |

0.979 |

0.972 |

0.962 |

0.956 |

| LEA |

0.987 |

0.981 |

0.974 |

0.964 |

0.958 |

| XTEA |

0.98 |

0.974 |

0.967 |

0.957 |

0.951 |

| SIMON |

0.985 |

0.979 |

0.973 |

0.963 |

0.957 |

| PRINCE |

0.986 |

0.98 |

0.974 |

0.964 |

0.958 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.985 |

0.979 |

0.973 |

0.963 |

0.957 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.986 |

0.98 |

0.973 |

0.963 |

0.957 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.99 |

0.985 |

0.98 |

0.97 |

0.965 |

Table 6.

CPU runtime result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

Table 6.

CPU runtime result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

| Lightweight cryptography algorithms |

Number of images |

| 50 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

| |

With attacks |

| AES |

0.072 |

0.145 |

0.213 |

0.287 |

0.359 |

| PRESENT |

0.068 |

0.140 |

0.206 |

0.277 |

0.347 |

| MESA |

0.083 |

0.162 |

0.238 |

0.314 |

0.385 |

| LEA |

0.071 |

0.148 |

0.217 |

0.292 |

0.363 |

| XTEA |

0.079 |

0.155 |

0.227 |

0.302 |

0.373 |

| SIMON |

0.075 |

0.151 |

0.222 |

0.296 |

0.367 |

| PRINCE |

0.078 |

0.156 |

0.229 |

0.303 |

0.375 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.077 |

0.153 |

0.226 |

0.300 |

0.371 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.118 |

0.246 |

0.370 |

0.493 |

0.625 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.150 |

0.310 |

0.465 |

0.612 |

0.765 |

| |

Without attacks |

| AES |

0.070 |

0.141 |

0.209 |

0.284 |

0.356 |

| PRESENT |

0.066 |

0.137 |

0.203 |

0.274 |

0.344 |

| MESA |

0.080 |

0.158 |

0.234 |

0.310 |

0.381 |

| LEA |

0.069 |

0.144 |

0.212 |

0.287 |

0.358 |

| XTEA |

0.077 |

0.152 |

0.224 |

0.299 |

0.370 |

| SIMON |

0.073 |

0.149 |

0.220 |

0.294 |

0.365 |

| PRINCE |

0.076 |

0.153 |

0.226 |

0.299 |

0.371 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.075 |

0.150 |

0.223 |

0.297 |

0.368 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.115 |

0.240 |

0.362 |

0.485 |

0.610 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.145 |

0.300 |

0.450 |

0.598 |

0.750 |

Table 7.

Encryption time result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

Table 7.

Encryption time result comparison of lightweight cryptographic algorithms with varying number of images for with and without attacks.

| Lightweight cryptography algorithms |

Number of images |

| 50 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

| |

With attacks |

| AES |

0.095 |

0.190 |

0.285 |

0.380 |

0.475 |

| PRESENT |

0.084 |

0.168 |

0.252 |

0.336 |

0.420 |

| MESA |

0.056 |

0.112 |

0.168 |

0.224 |

0.280 |

| LEA |

0.057 |

0.114 |

0.171 |

0.228 |

0.285 |

| XTEA |

0.053 |

0.106 |

0.159 |

0.212 |

0.265 |

| SIMON |

0.059 |

0.118 |

0.177 |

0.236 |

0.295 |

| PRINCE |

0.052 |

0.104 |

0.156 |

0.208 |

0.260 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.065 |

0.130 |

0.195 |

0.260 |

0.325 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.051 |

0.103 |

0.155 |

0.207 |

0.259 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.048 |

0.096 |

0.144 |

0.192 |

0.240 |

| |

Without attacks |

| AES |

0.090 |

0.180 |

0.270 |

0.360 |

0.450 |

| PRESENT |

0.080 |

0.160 |

0.240 |

0.320 |

0.400 |

| MESA |

0.054 |

0.108 |

0.162 |

0.216 |

0.270 |

| LEA |

0.055 |

0.110 |

0.165 |

0.220 |

0.275 |

| XTEA |

0.051 |

0.102 |

0.153 |

0.204 |

0.255 |

| SIMON |

0.057 |

0.114 |

0.171 |

0.228 |

0.285 |

| PRINCE |

0.050 |

0.100 |

0.150 |

0.200 |

0.250 |

| RECTANGLE |

0.063 |

0.126 |

0.189 |

0.252 |

0.315 |

| RSA-AM+OBBO |

0.049 |

0.098 |

0.147 |

0.196 |

0.245 |

| ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

0.046 |

0.092 |

0.138 |

0.184 |

0.230 |

Table 8.

Result comparison of proposed and existing lightweight crypto algorithm models for original and encrypted images.

Table 8.

Result comparison of proposed and existing lightweight crypto algorithm models for original and encrypted images.

| Images |

Lightweight cryptography algorithms |

NPCR |

UACI |

Cross entropy |

| ECG |

CTE + Dynamic Chaotic [31] |

99.623 |

47.168 |

0.139 |

| |

ASCONv1.2 + HOC + MWG |

99.700 |

48.500 |

13.950 |

| EEG |

CTE + Dynamic Chaotic [31] |

99.625 |

44.325 |

0.110 |

| |

ASCONv1.2 + HOC + MWG |

99.710 |

45.800 |

12.120 |

| MRI |

CTE + Dynamic Chaotic [31] |

99.614 |

39.678 |

0.134 |

| |

ASCONv1.2 + HOC + MWG |

99.690 |

41.000 |

13.545 |

| X-Ray |

CTE + Dynamic Chaotic [31] |

99.617 |

31.225 |

0.132 |

| |

ASCONv1.2 + HOC + MWG |

99.695 |

33.000 |

13.340 |

Table 9.

Result comparison of proposed and existing lightweight crypto algorithm models for original and decrypted images.

Table 9.

Result comparison of proposed and existing lightweight crypto algorithm models for original and decrypted images.

| Images |

Lightweight cryptography algorithms |

NPCR |

UACI |

Cross entropy |

| ECG |

CTE + Dynamic Chaotic [31] |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| |

ASCONv1.2 + HOC + MWG |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| EMG |

CTE + Dynamic Chaotic [31] |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| |

ASCONv1.2 + HOC + MWG |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| MRI |

CTE + Dynamic Chaotic [31] |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| |

ASCONv1.2 + HOC + MWG |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| X-Ray |

CTE + Dynamic Chaotic [31] |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| |

ASCONv1.2 + HOC + MWG |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 10.

Complicity analysis of proposed and existing lightweight crypto algorithm models.

Table 10.

Complicity analysis of proposed and existing lightweight crypto algorithm models.

| Aspect |

CTE+dynamic chaotic [31] |

ASCONv1.2+HOC+MWG |

| Time complexity |

O(m.n) |

O(k.b+n+k.logk) |

| Space complexity |

O(m+n) |

O(m+n+k) |