1. Introduction

Podocytes are key constituents of the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) and podocyte loss leads to progressive and often irreversible decline in kidney function. The filtration barrier, which prevents leakage of proteins and molecules larger than the size of albumin into the urine, is a complex structure dependent on the correct localization of several structural and signaling proteins [

1]. Nephrin, a 150 kDa trans-membrane protein and member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is one of the most important components of the GFB. Loss of functional nephrin in podocytes leads to significant proteinuria and irreversible renal decline [

2]. Nephrin, however, can also be lost or mislocalized in acquired forms of kidney disease, particularly in immune mediated kidney diseases [

3,

4]. A recent study also found the presence of antinephrin autoantibodies in a significant proportion of patients with minimal change disease [

5]. Antinephrin autoantibody levels correlated with disease activity, suggesting that these autoantibodies are pathogenic. In addition, immunization of mice with the ectodomain of murine nephrin resulted in nephrin autoantibody formation and development of significant proteinuria together with down-regulation of proteins necessary to maintain the filtration barrier. The mechanisms underlying how nephrin autoantibodies result in nephrin degradation and damage to the filtration barrier remain unknown.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are 18-22 nucleotide noncoding RNAs that that regulate gene expression by binding of a “seed” sequence in the miRNA to the 3’ or on some occasions the 5’ UTR of a target mRNA, thereby inducing degradation or transcriptional repression of the target [

6,

7]. Of note is that small changes in microRNA expression can have significant effects on their target genes. Previous studies have shown that a microRNA miR-204 which is expressed in the kidney is protective in hypertensive and diabetic kidney disease [

8]. In addition, several studies have shown that decreased expression of miR-204 exacerbates kidney injury in various animal models of renal diseases [

9].

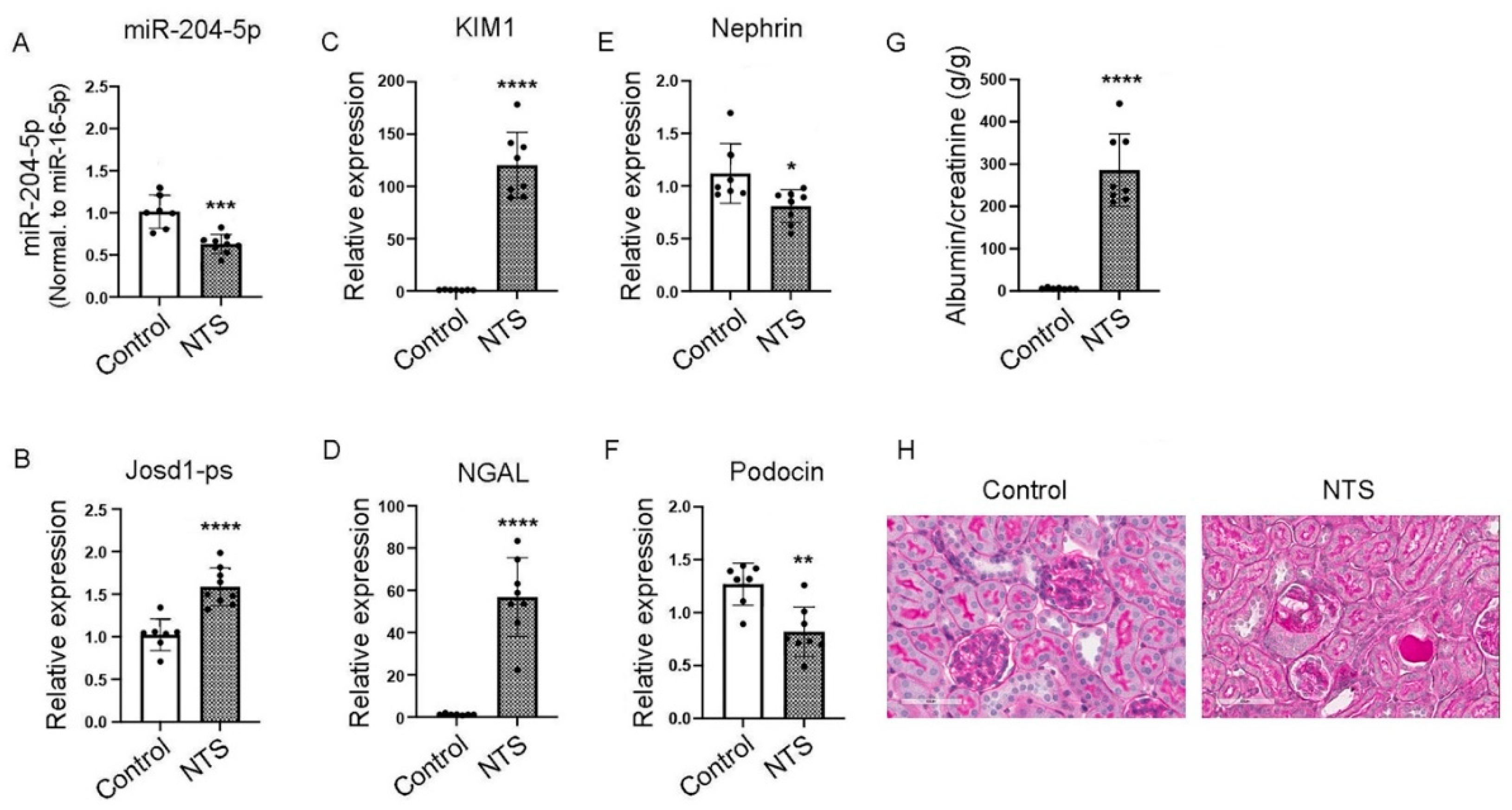

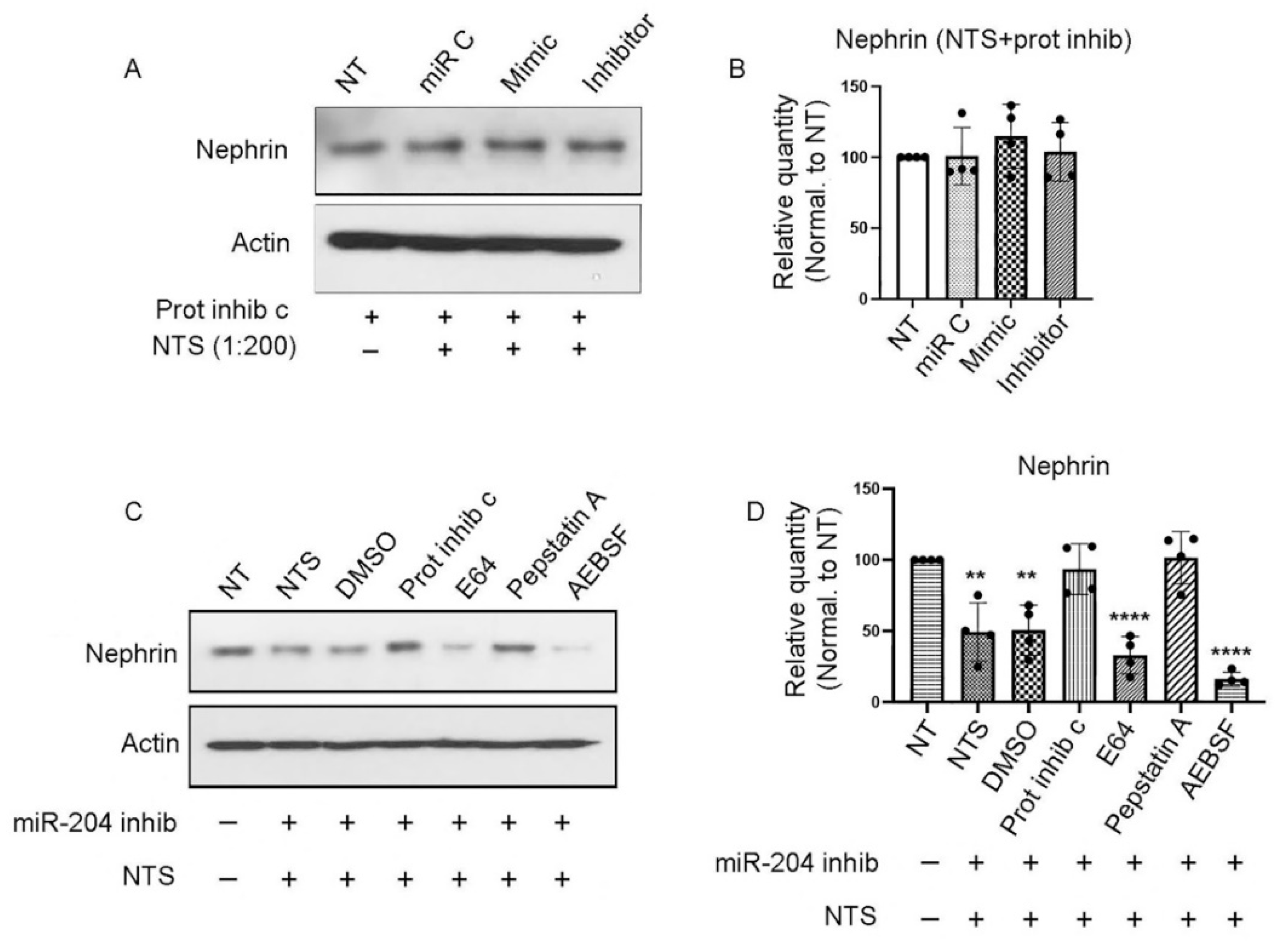

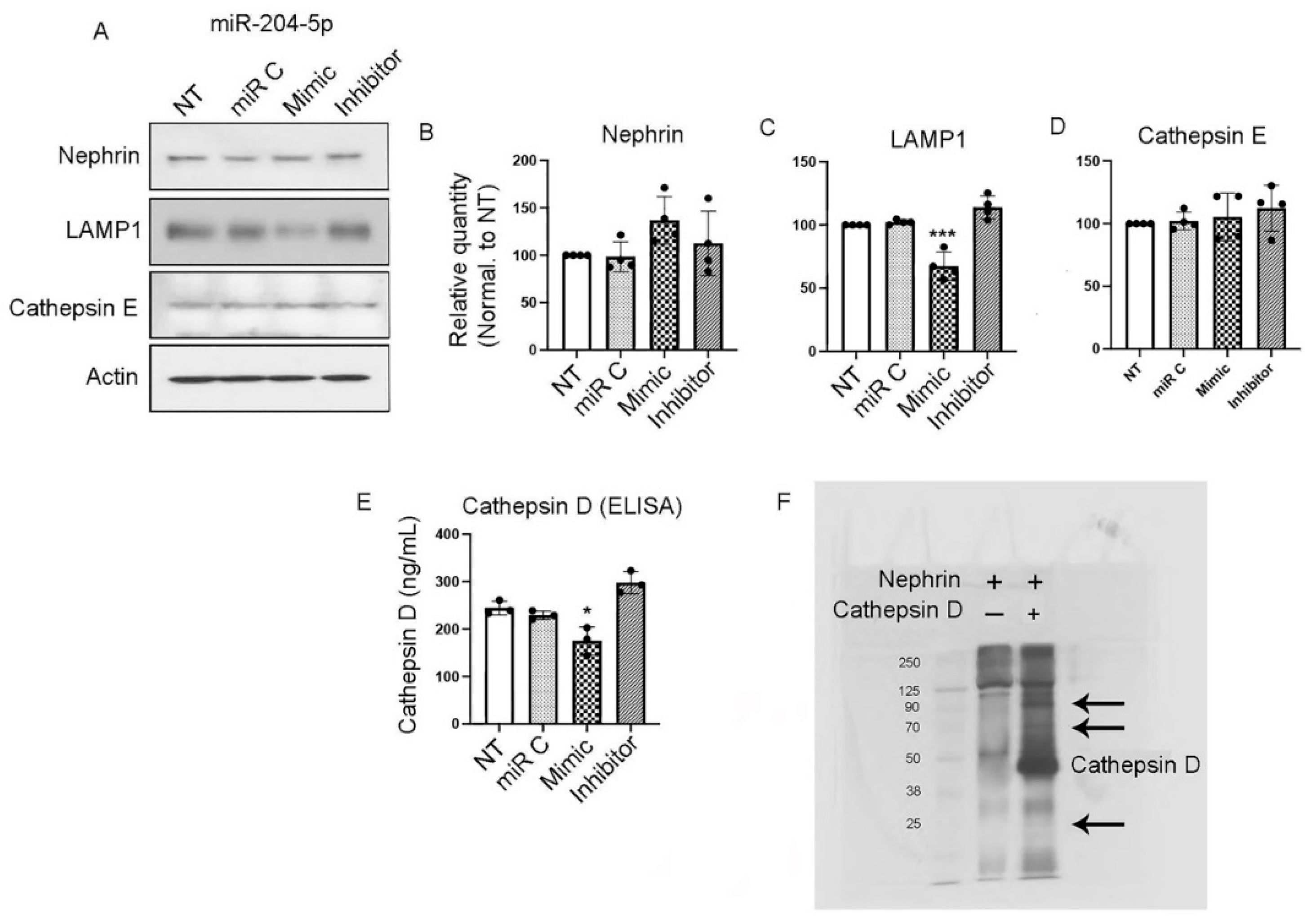

In this study, we evaluated whether miR-204 is protective in an in vitro model of podocyte stress induced by treating cultured murine podocytes with nephrotoxic serum (NTS) which contains antinephrin antibodies. We show that after NTS treatment, miR-204-5p overexpression protects nephrin from enzymatic degradation by cathepsin D, thereby preserving nephrin expression. We also find that lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) and cathepsin D are direct miR-204-5p targets. In addition, we demonstrate that the long non-coding RNA Josd1-ps regulates miR-204-5p function. We also show that induction of nephrotoxic serum nephritis, an in vivo model of immune mediated kidney disease, results in decreased kidney expression of miR-204 and that proteinuria and histologic damage can be significantly ameliorated by treatment with Pepstatin A, an inhibitor of cathepsin D. Taken together, our results suggest that after an immune mediated insult miR-204 protects nephrin from cathepsin D mediated degradation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Nephrin antibody (R&D Systems Minneapolis, MN, USA, cat# AF3159, lot# CBIK0422122). Neph1 antibody (NovusBio Centennial, CO, USA, cat# NBP3-03509, lot# 0107180201). Podocin antibody (Invitrogen ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA, cat#P A5-37904, lot# ZD4291857). LAMP1 antibody (abcam, Boston, MA, USA, cat# AB208943, lot# 1015275-34). Actin antibody (SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, cat# A1978, lot# 109M4849V), C5b-9 antibody (bioorbyt, Durham, NC, USA, cat# orb100655, lot# RB70). Alexa-635 phalloidin (Invitrogen ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA, cat# A34054, lot# 2127282). Cathepsin E antibody (NovusBio Centennial, CO, USA, cat# NB400-152SS, lot# B-6).

2.2. Cell Culture

Immortalized mouse podocytes, generated from C57BL/6J mice as described [

10], were cultured from frozen stock in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin and grown at 37 °C and 5 % CO

2.

2.3. miRNA Transfection and NTS Treatment

MicroRNA-204-5p mimic, inhibitor and negative control sequences were purchased from (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA, mimic cat# 4464066, lot# ASO2LE3J; inhibitor cat# 4464084, lot# ASO2KMY0; control cat# 4464076, lot# ASO2JI01). The cells were transfected using HiPerFect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, cat# 301705, lot# 172028439) and 50 nM of each microRNA sequences mimic, inhibitory, or control were added to the cells dropwise and incubated for further 72 h at 37 °C. The podocytes were then treated with nephrotoxic serum (NTS) (Probetex San Antonio, TX, USA, cat# PTX-001S-Ms, lot# 612-3T) at 1:200 dilution and incubated overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The next day the cells were washed with PBS and the cell lysates were collected using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany, cat# 04693159001).

2.4. SDS-PAGE and Western Blot

The cell lysates concentration was estimated using Pierce BCA protein assay and 10 ug was resolved in 10% SDS-PAGE gel. The proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane and blocked with 5% skim milk in PBST. The primary antibodies were added at 1:1000 dilution prepared in blocking buffer and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were washed 3X with PBST for 30 min and anti-species secondary antibodies were added at 1:10000 dilution for 1 hour at RT. The membranes were washed again with PBS for 30 min and developed using Immobilon Forte Western Blot Substrate (Millipore, Burlington MA, USA, cat# WBLUF0100, lot# 221543) and exposed to an X-Ray film.

2.5. Immunofluorescence

Mouse podocytes were seeded on 35 mm glass bottom MatTek (Ashland, MA) dishes. The cells were transfected with 50 nM miR 204 mimic or inhibitory sequences or control sequence using HiPerFect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, cat# 301705, lot# 172028439) for 72 hours at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and stained with nephrin and phalloidin-488. The images were obtained using Olympus 1X81 (Tokyo, Japan) confocal microscope available at the Advanced Light Microscopy Core Facility at the Colorado University Anschutz Medical Campus. The images were deconvoluted using Huygens Essential 23.10 software (Scientific Volume Imaging, Hilversum, The Netherland) under the conservative setting.

2.6. Lentivirus-Mediated LncJosd1-ps Overexpression and Antisense Oligos Knockdown

The long non-coding RNA Josd1-ps (GenBank: NG_065344.1) full sequence was cloned into the lentivirus plasmid VVPW (kind gift from Gabriele Luca Gusella, Icahn School of Medicine Mount Sinai Hospital, NY City, NY, USA) and validated by sequencing. The VVPW plasmid along with the packaging plasmid psPAX2 (Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA) and the envelope plasmid pCMV-VSV-G (Addgene) were combined with FUGENE HD (Promega, Madison, WI, USA, cat# E2311, lot# 0000553944) transfection reagent at the 3:2:1 ratio and added to ~70% confluent 293T cells. The cells supernatants were collected after 48 and 72 hours post transfection and validated for LncJosd1-ps overexpression by qPCR using RNA isolated from cells infected with 20% lentivirus supernatants. The mouse podocytes were infected with LncJosd1-ps lentivirus particles in addition to 8 μg/mL polybrene. The cells were used in experiments after 72 hours of infection. LncJosd1-ps knockdown was performed using antisense oligos (ASO). The knockdown was validated using two different ASOs at 1nM delivered using HiPerFect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, cat# 301705, lot# 172028439) and the experiments were performed 72 hours after transfection.

2.7. Cytoplasmic and Nuclear RNA Extraction

The RNA from the cytoplasm and the nucleus of mouse podocytes were isolated using the NORGEN BIOTEK CORP. kit (Thorold, ON, Canada, cat# 21000, lot# 605095) as per manufacturer’s instructions using cells growing in monolayer protocol.

2.8. Quantitative PCR and microRNA Analysis

The RNA was extracted using the TRIzol (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA, cat# 15596026, lot# 349906) method and quantified using NanoDrop 2000 (ThermoScientific). One microgram of total RNA was reversed transcribed into cDNA using LunaScript (NE Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA, cat# E3010L, lot# 10175742). SYBR Green master mix (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA, cat# A25742, lot# 2905743) was used and the PCR reaction was amplified using BioRad SFX96 Thermocycler. The antisense oligos (ASO) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) (Morrisville, NC, USA). Gene expression was normalized to Valosin containing protein (VCP) and asparagine-linked protein homolog 9 (ALG9). The results are reported as log

10 (2

-DDCt). The primers were ordered from IDT (Coralville, IA, USA) and the list of primers and anti-sense oligos used in this study are listed in

table S1 of supplementary data. The microRNA RT-PCR was performed the miRCURY LNA system (Qiagen Hilden, Germany). miRCURY LNA RT kit (cat# 339340, lot# 77203282). miRCURY LNA SYBR Green PCR kit (cat# 339346, lot# 77203504). miRCURY LNA miRNA PCR Assay primers: miR-204-5p (cat# YP00206072, lot# 20304364-2), miR-16-5p (cat# YP00205702, lot# 40501706-2).

2.9. Protease Inhibitors Assay

Mouse podocytes transfected with miR-204 inhibitory sequence were loaded with the following protease inhibitors: 0.25 mM AEBSF (SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, cat# SBR00015, lot# 0000188562), 1 mM Pepstatin A (SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, cat# SAE0154, lot# P318, lot# 0000144172), 20 mM E64 (SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, cat# SAE0154, lot# 0000105689), and 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany, cat# 04693159001) for 60 min at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. NTS was added at 1:200 dilution and the cells were incubated overnight. The next day the cells were washed 2X with PBS and cell lysates was collected and resolved using SDS-PAGE and Western blot.

2.10. Cathepsin D ELISA

Cathepsin D was detected using mouse cathepsin D SimpleStep ELISA kit (abcam Waltham, MA, USA, cat# ab239420) as per manufacturer’s instructions, and the plate was read at 450 nm using BioTek Synergy 2 plate reader.

2.11. Nephrin Digestion

Nephrin digestion with cathepsin D was carried out as described previously [

11]. Briefly, 10 μg of recombinant mouse nephrin (R & D Systems Minneapolis, MN, USA, cat# 3159-NN-050, lot# NZA0422021) was incubated with 10 μg of recombinant mouse cathepsin D (R & D Systems Minneapolis, MN, USA, cat# 1029-AS-010, lot# FVE0122021) in 100 mM sodium citrate, 200 mM NaCl buffer (pH 3.5) for 3 hours at 37 °C.

2.12. Silver Stain

The digested nephrin was resolved on an SDS-PAGE gel and stained using silver stain (ThermoFisher Waltham, MA, USA, silver reagent cat# 1851130, lot# VB297147, stabilizer base reagent cat# 1851190, lot# VC297149, and reducer aldehyde reagent, cat# 1851170, lot# VB297148) as per manufacturer’s instructions.

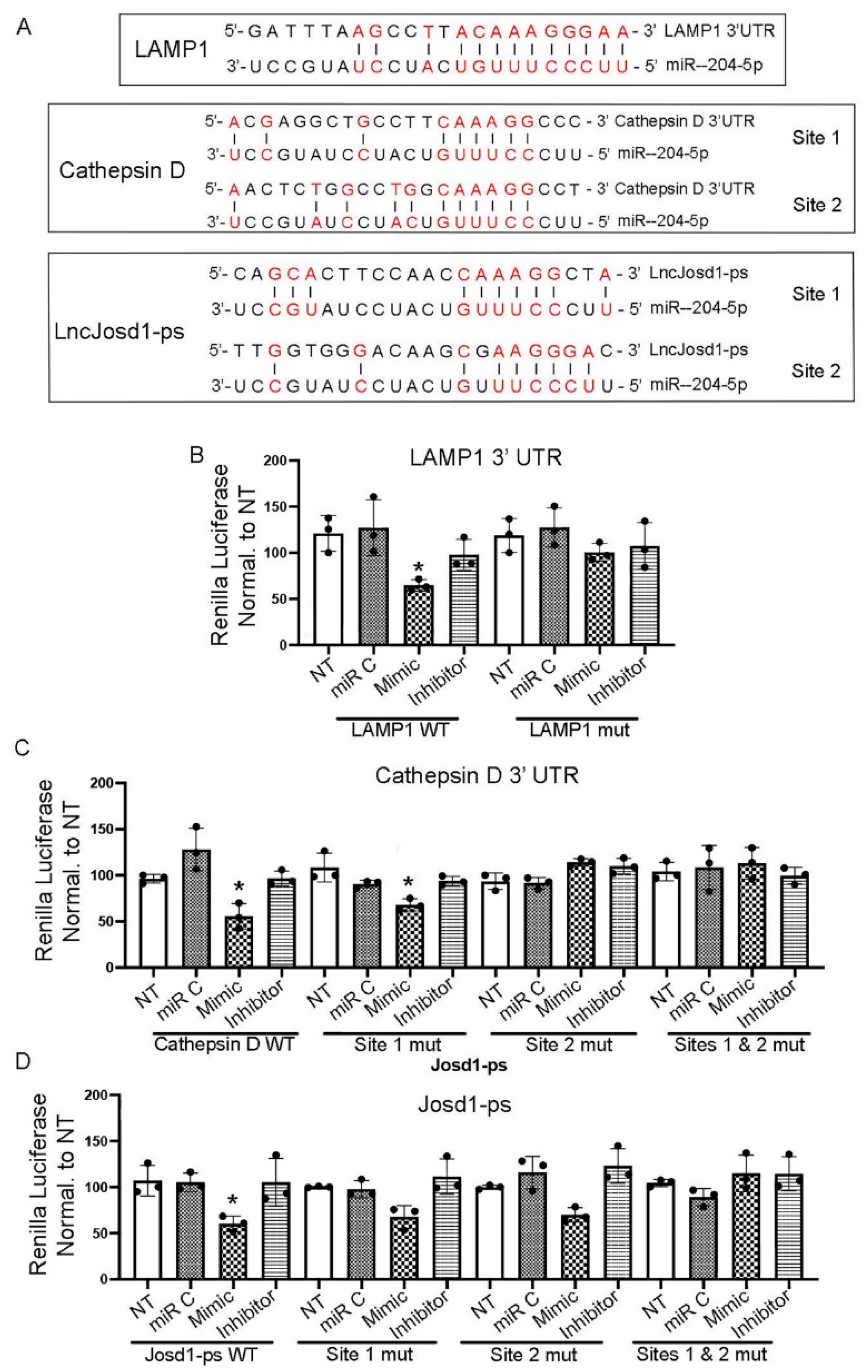

2.13. Site Directed Mutagenesis

The mutation of miR-204-5p binding sites in LAMP1, cathepsin D, and Josd1-ps was performed according to New England Biolabs Q5 ® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Ipswich, MA, USA, cat# E0554S, lot# 10164452) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers used to insert the mutated sequence into the lentivirus plasmids were designed using NEBaseChanger™ tool available at New England Biolabs website. The resulting mutant plasmids were validated by sequencing that was performed by Quintara Biosciences (Denver, CO, USA).

2.14. Luciferase Assay

LAMP1, cathepsin D 3’UTR and Josd1-ps sequences were cloned into pIS2 luciferase plasmid (a gift from David Bartel, plasmid 12177; Addgene) and validated by sequencing. Mouse podocytes were transfected with 1 ug of pIS2 plasmid using ViaFect transfection reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA, cat# 4981, lot# 0000514926) as well as the cells were transfected with 50 nM miR control sequence or miR-204-5p mimic or inhibitor sequences using the transfection reagent HiPerFect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, cat# 301705, lot# 172028439). The luciferase activity was determined 72 h post transfection using the Renilla luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA, cat# E183A, lot# 0000537514) as described in the manufacturer’s product manual. The luciferase substrate’s background fluorescence was subtracted from all the samples readings. The luciferase assay data were normalized to protein concentrations (reporter activity/total protein).

2.15. Identification of miR-204 Long Non-Coding RNA Binding Partners

miR-204 interaction with long non-coding RNA was analyzed using RNA22 and miRCode prediction tools to identify potential targets with at least 6 nucleotides interacting with miR-204-5p seed region. Other prediction tools used to predict miR-204 target genes including TargetScan and miRDB.

2.16. In Vivo Experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Colorado Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and performed according to the PHS Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and IACUC.

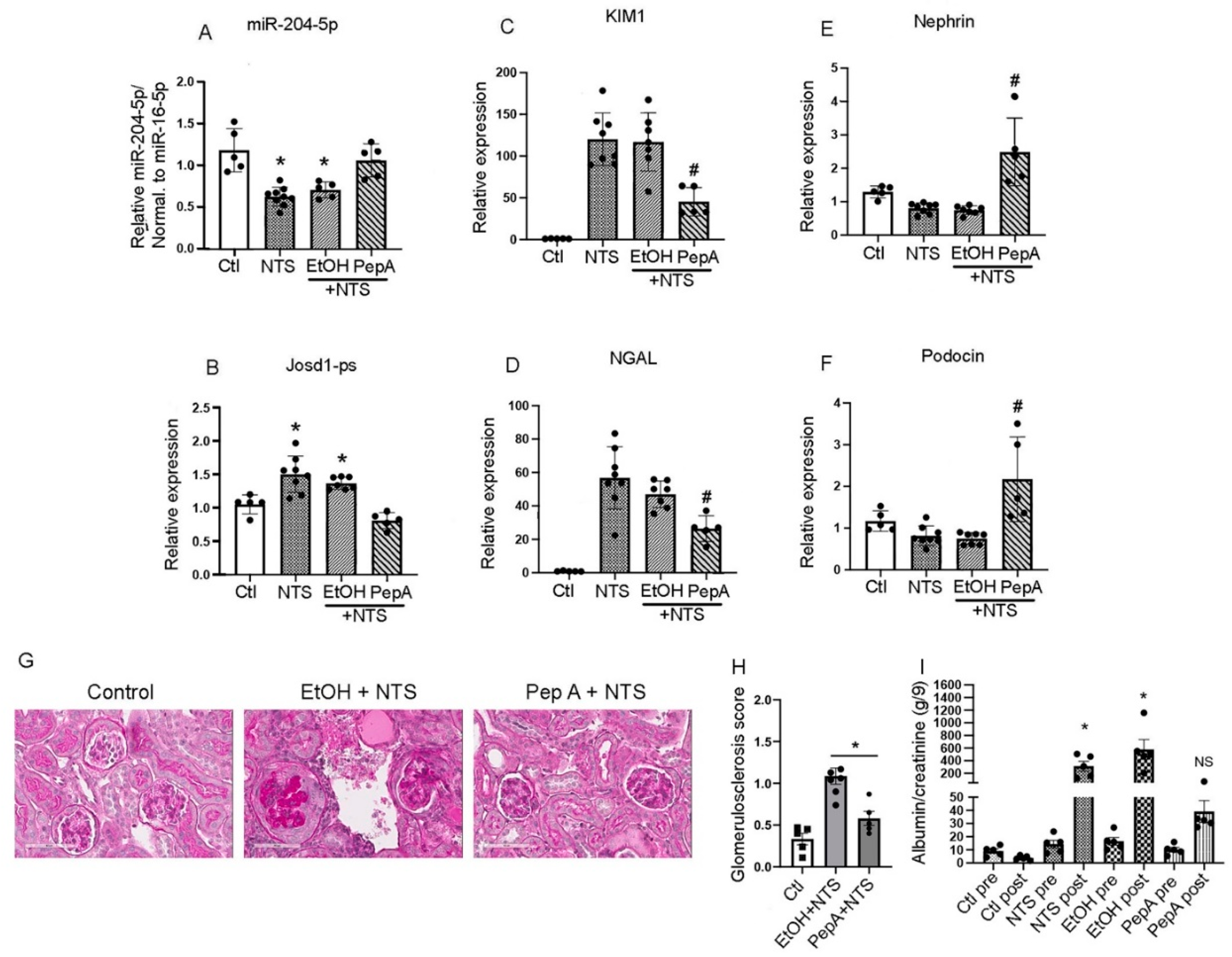

The nephrotoxic serum nephritis mouse model was performed as previously described [

12]. Male C57Bl/6 mice 8-12 weeks old were injected with 100 μL of sheep anti-rat glomerular basement membrane antibodies (NTS) purchased from Probetex Inc. (Probetex San Antonio, TX, USA, cat# PTX-001S-Ms, lot# 612-3T) via tail vein. The mice were euthanized after seven days. Blood and urine were collected prior to euthanasia for blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and proteinuria analysis. For Pepstatin A experiment, following the NTS injection Pepstatin A was administered as described previously [

13]. Briefly, male C57Bl/6 mice received 20 mg/kg Pepstatin A by intraperitoneal injection on day 1, 3, and 5 after the NTS injection and the mice were euthanized on day 7. Control mice received 100 μL of ethanol on day 1, 3 and 5 post NTS delivery and the mice were euthanized on day 7.

2.17. MTT Cell Toxicity Assay

Immortalized mouse podocytes were seeded in a 96-well tissue culture plate and grown at 37 °C and 5% CO

2 overnight. The next the cells were transfected with miR-204-5p mimic, inhibitory sequences or a negative control sequence and treated with NTS as described in

section 2.3. MTT (Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide, Tocris cat# 298-93-1, lot# 8A/261332) was added at 10 μL/well of 5 mg/mL and the plate was incubated for 4 hours. The medium was removed and the formazan crystals were solubilized with 100 μL/well dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and the plate was read using absorbance of 570 nm BioTek Synergy 2 plate reader.

2.18. Statistics

The statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10 for macOS, Version 10.4.0 (Boston, MA, USA). The datasets were analyzed using one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons to compare the mean of each column with the mean of every other column. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Discussion

Podocyte injury is detrimental to proper kidney function and at the core of various glomerulopathies [

2]. Identifying the different mechanisms that lead to podocyte injury aids in the development of novel therapeutic measures to treat podocytopathies.

Several podocyte antigens such as PLA2R1, THSD7A, NELL1, HTRA1, and nephrin are the primary targets of deleterious autoantibodies in glomerulonephritis patients [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Of all those antigens nephrin is an integral component of the slit diaphragm and is directly involved in preventing large proteins from leaking into the urine [

19]. Various in vivo studies demonstrated the importance of miR-204 expression for the preservation of the kidney function. The reported mechanisms involve the decreased expression of certain long-noncoding RNAs that block miR-204 activity such as MALAT1 [

20] and Kcnq1ot1 [

21] or by the activation/deactivation of signaling pathways including HMX1 [

22], Smad5 [

23], NLRP3 inflammasome [

21], and Fas/FasL [

9]. However, a direct link between miR-204 function and podocytes has not been reported. In this study, we describe the mechanisms underlying miR-204-5p protection of nephrin after NTS-induced stress.

The nephrotoxic serum model is widely used as an in vivo model of acute and chronic glomerulonephritis [

24]. However, the specific effect of NTS on podocytes in vitro is not clear. Given the reported function of miR-204 in protecting kidney function, we sought to explore the effect of miR-204 modulation on podocytes in the presence of NTS. Initial experiments with an NTS time course in a mouse podocyte cell line did not show a change in nephrin expression. However, when podocytes were transfected with miR-204-5p inhibitory sequence and treated with NTS nephrin expression was significantly decreased whereas levels of neph1 and podocin remained unchanged. This result suggests that miR-204-5p protects nephrin from the toxic effects of NTS. Interestingly, when podocytes were grown on a glass cover slip for immunofluorescence staining the effect of miR-204-5p inhibitory sequence and NTS was so drastic that the majority of cells did not survive and the remaining cells were almost devoid of nephrin. In contrast, the presence of miR-204-5p was protective at even a low level of expression in the cells that received microRNA control sequence and the miR-204-5p mimic sequence showed a strong protective effect on nephrin expression and the overall viability of the cells. Since the NTS contains anti-nephrin antibody, it suggested that the complement system is activated. Immunofluorescence staining of control and NTS-treated cells showed intracellular location of C5b-9 in control cells however the NTS-treated cells displayed surface as well as cytoplasmic C5b-9 locations. Notwithstanding the complement activation there was no detectable cell lysis even though C5b-9 deposition on the cell surface was observed. It is not surprising that podocytes can resist complement-mediated cell killing. Previous reports also showed that

in vitro cultured podocytes can withstand complement activation in a mechanism that involves several complement regulatory molecules such as factor H, CD46, CD55, and CD59 that the podocytes possess [

25,

26].

The loss of nephrin in podocytes treated with NTS and miR-204-5p inhibitory sequence can be attributed to an enzymatic activity as we observed a rescue of nephrin expression when the cells were pretreated with a protease inhibitor cocktail prior to treatment with NTS and miR-204-5p inhibitory sequence. In the search for a potential enzyme group that is responsible for nephrin degradation we pretreated the podocytes with various enzyme inhibitors including: the cysteine proteases inhibitor E64, the aspartyl enzymes inhibitor Pepstatin A, and the serine proteases inhibitor AEBSF. Nephrin was only rescued by Pepstatin A. The results suggested the involvement of an aspartic enzyme(s), a group of proteases that include pepsins, renins and cathepsins [

27]. Amongst this group of proteases, the cathepsins seemed more likely candidates to be involved in nephrin degradation. Screening the 3’UTR of the two cathepsin aspartic proteases cathepsin D and E, we identified cathepsin D as a potential target of miR-204-5p that was validated using a luciferase assay. The interaction between cathepsin D and nephrin was demonstrated by the cleavage of recombinant mouse nephrin by mouse cathepsin D. This result suggested that in the absence of miR-204-5p expression cathepsin D, under cellular stress such as that incurred by NTS, can act upon nephrin to reduce its expression. In line with our observation, in diabetic nephropathy nephrin is internalized inside endocytic vesicles mediated by dynein light chain 1 (

DYNLL1) and eventual nephrin is degraded in the lysosome. In the absence of

DYNLL1 expression endocytosed nephrin was recycled back to the plasma membrane [

28]. Another mechanism of nephrin degradation may also involve the SEL1L-HRD1 protein complex of endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) which is highly expressed in podocytes where nephrin is an endogenous substrate [

29]. However, this degradation pathway was not investigated in this study.

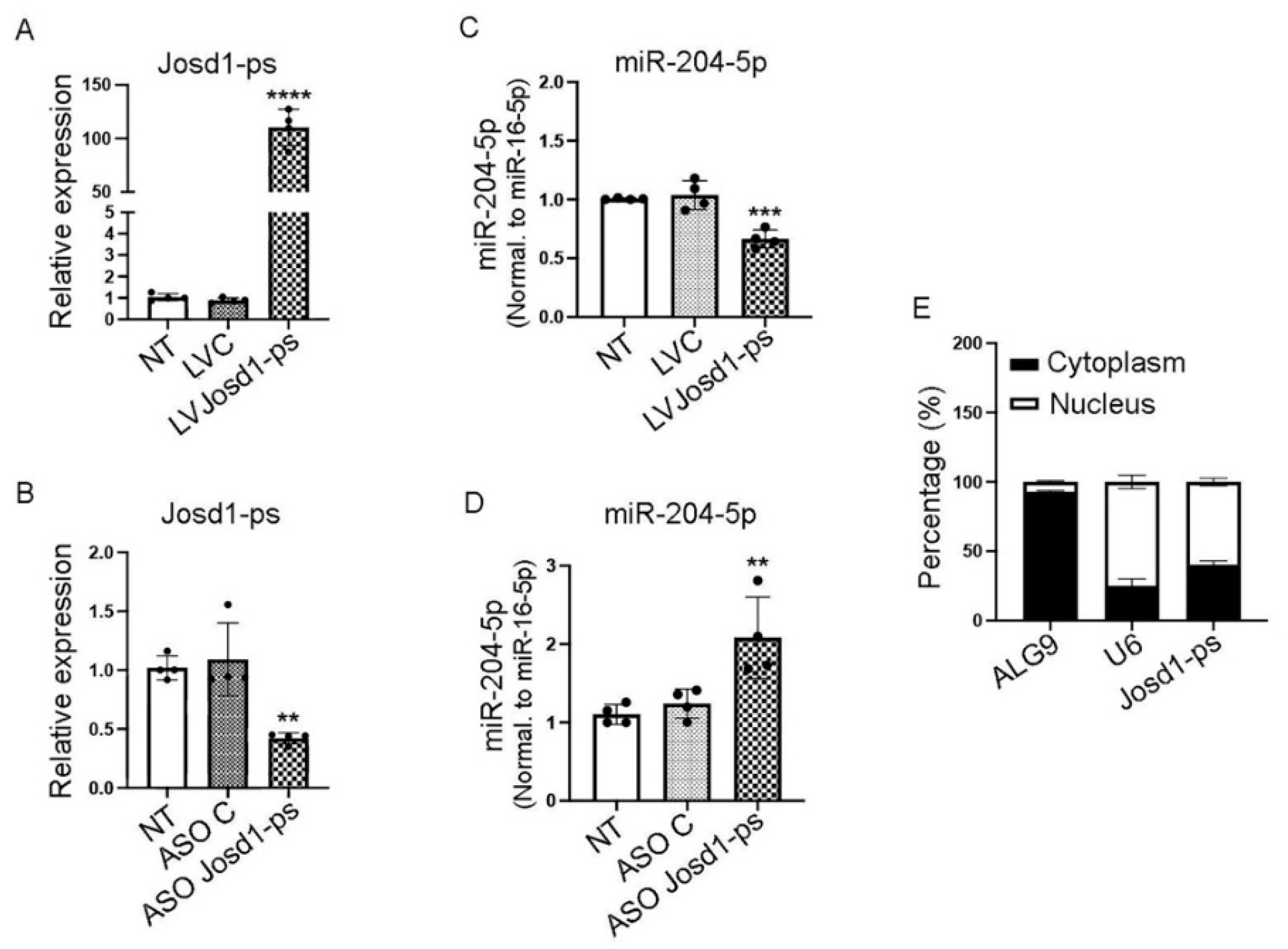

The expression level of mir-204-5p was down regulated in mice treated with NTS suggesting that a long noncoding RNA may regulate miR-204-5p activity. Several lncRNA reportedly regulate miR-204-5p function including MALAT1, KCNQ1OT, and SPANXA1-OT1 [

20,

21,

23] along with other potential in silico identified LncRNA partners of miR-204-5p were assayed for expression in mice treated with NTS. Amongst all the assayed lncRNAs only LncJosd1-ps was up regulated suggesting a potential interaction with miR-204-5p that merited further validation. No reports were found that described a function for lncJosd1-ps. We cloned lncJosd1 into a lentivirus vector and designed antisense oligos in order to manipulate its expression and determine whether it has any effect on miR-204-5p expression. The results clearly showed a link between lncJosd1-ps expression and that of miR-204-5p suggesting a potential binding partnership. Indeed, lncJosd1-ps overexpression led to miR-204-5p suppression and lncJosd1-ps inhibition increased miR-204-5p expression. This binding partnership was further validated and confirmed using a luciferase assay. The cellular location of lncJosd1-ps is important for its “sponging” of microRNA function. Although around 60 % of lncJosd1-ps transcripts are present in the nucleus, the remaining 40 % are available in the cytoplasm for a potential sponging activity.

There is a general agreement in the scientific literature that the expression of miR-204 is protective in various kidney injury models [

8,

9,

20,

21,

22,

23,

30]. However, the nephroprotective function of miR-204 has never previously been linked to nephrin. Here we show a correlation between miR-204 and nephrin expression and ultimately kidney function. In the NTS animal model miR-204-5p expression was significantly downregulated which coincided with nephrin’s reduced expression. As a result, the renal injury was severe as measured by the elevated expressions of the kidney injury markers KIM1 and NGAL as well as the albumin/creatinine ratio with noticeable glomerular injury. In contrast, Pepstatin A treatment in vivo protected miR-204-5p and nephrin expression and overall kidney function. Inhibiting aspartyl proteases had a beneficial effect on kidney function after NTS treatment but other potential effects of inhibiting aspartyl proteases remain to be determined. It has proved very challenging to deliver microRNAs effectively to podocytes. However, once miRNAs can be delivered to podocytes with high efficiency, miR-204 remains an excellent candidate for potential renal therapy for glomerular diseases in which nephrin is degraded. Our findings are of special relevance given recent findings that anti-nephrin autoantibodies are present in a significant number of patients with minimal change disease [

4]. However, the mechanisms underlying how these anti-nephrin autoantibodies lead to loss of nephrin from the slit diaphragm remain to be determined.