1. Introduction

Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, driven by advanced convolutional neural networks and large language models, have made great progress in many fields, such as language comprehension, intelligent identification of satellites in orbit, and autonomous driving of vehicles [

1,

2]. However, these models with numerous parameters have high accuracy but are usually very large, which limits their practical use in resource-constrained environments. This has created an urgent need to accelerate the development of neural network models.

The quantization of neural network models is an important approach for optimizing models and increasing their speed [

3]. It converts traditional 32-bit floating-point parameters into more compact 8-bit or lower precision formats [

4,

5]. This technique is crucial for the AI field because it can reduce storage, computational needs, and energy consumption of neural network models [

6,

7,

8]. It enables complex neural networks to be effectively implemented on resource-limited platforms like mobile devices and embedded systems [

9,

10]. Quantization extends the application of deep learning and promotes the use of intelligent algorithms in edge computing environments [

11,

12]. It also provides a solid foundation for real-time data analysis, processing, and decision-making, enhancing the operational effectiveness of AI in industries like smart wearables, edge computing, and collaborative sensing [

13,

14].

Quantization involves converting continuous floating-point numbers to discrete integers, which brings benefits but also causes inherent precision loss [

15,

16,

17]. Finding a quantization technique to minimize this loss is a major challenge in modern AI research. Although there are clear advantages, existing quantization methods often suffer from significant precision degradation and lack of robustness. This is mainly due to the unclear mechanisms that cause precision reduction during quantization, making it hard to accurately evaluate the performance of quantized models.

Quantization is a complex process affected by various factors, and each factor uniquely and interconnectedly influences the model's accuracy. Input datasets and quantization parameter choices can significantly impact quantization accuracy. Weight distributions branches vary greatly, resulting in a wider range of converted weights. A large part of values cluster around 0, but values away from 0 are also important. This combination makes quantification challenging [

18]. Therefore, it is of great significance to select appropriate quantization parameters. Therefore, Mixed-Precision Quantization (MPQ) is a major trend in the quantization of neural network models in the future [

19,

20,

21]. Different combinations of bit-widths will also lead to varying degrees of accuracy loss [

22,

23,

24]. A common way to achieve quantization accuracy is to run the model on the entire test dataset. But this method has limitations, such as scalability problems and the risk of overfitting to the test data, which may not work well with new, unseen data. Moreover, running the model on a full test set can be computationally costly and time-consuming, especially for large models and datasets.

From the dataset perspective, large test sets require significant storage and processing time, while small ones may give unreliable results. Research shows that compressing datasets can reduce data volume and improve model validation efficiency. Dataset Distillation was first proposed by Wang et al. [

25], aiming to extract knowledge from large datasets to create much smaller synthetic datasets. Models trained on these distilled datasets are expected to perform as well as those trained on the original larger datasets. Zhao et al. [

26] proposed a dataset compression technique called Dataset Condensation. It aims to train deep neural networks effectively by generating a small number of information-rich synthetic samples, reducing storage and processing costs of large datasets. Sajedi et al. [

27] introduced a new dataset distillation method, DataDAM, which uses the Spatial Attention Matching Module (SAM) to capture and replicate the original dataset's distribution characteristics. Guo et al. [

28] put forward Difficulty-Aligned Trajectory Matching (DATM), which generates targeted informative patterns based on synthetic data's learning trajectories during training. It focuses on reproducing basic easy-to-learn patterns for small synthetic datasets and emphasizes modeling more complex patterns for larger ones. However, existing dataset compression techniques mainly focus on compressing training datasets, often ignoring the test dataset. As a result, the test dataset, which is important for evaluating model performance, may remain large and cumbersome, reducing the overall efficiency gains of dataset compression.

From the hardware perspective, when testing with simulated quantization on a PC, fully simulating the hardware computation process is very time-consuming. Simplifying the quantization computation process, as in fake quantization [

29], can lead to differences between simulated results and actual hardware performance due to different implementation methods. If testing is done on actual end devices, all samples must be evaluated to obtain performance metrics. This testing method has a limited application scope and requires more time and storage space. Processing and reasoning through all test dataset samples take a lot of time and storage, making it impractical in deployment scenarios with limited computing resources.

From the model structure perspective, existing methods for predicting the accuracy of quantized neural networks are usually limited to specific architectures. They cannot adapt well to changes in model structures and fail to effectively encode the representation of quantization parameters. Wang et al [

30] constructed a quantization accuracy predictor based on the highly flexible Once For All network [

31]. This predictor encodes the model structure and quantization strategy to directly predict the accuracy of the quantization model. However, in this approach, collecting the quantization dataset requires 16,000 GPU hours, which is both costly and time-consuming. Moreover, the quantization predictor is only capable of predicting neural network models with a predetermined structure.

To address these challenges, we propose a single-image input accuracy predictor for neural network models using the attention mechanism. This predictor uses an encoder to learn the features of each layer of the quantized data and then generates a single image representing the whole dataset through a decoder. By taking a single image as input, it can quickly output the model's quantization accuracy, providing a more efficient and practical solution for evaluating quantized models.

2. Methods

2.1. Overall Design Scheme

Existing methods for measuring the accuracy loss of the quantized neural network models usually require a series of steps on the embedded side. Besides, the quantization accuracy loss is measured by comparing the differences in the model's output before and after quantization. However, these methods are time-consuming and complex when deploying models on the embedded side. This is not beneficial for the instant iterative optimization of the quantization parameters and the rapid development of the tool chain.

We conduct research on methods for measuring the accuracy loss of the quantized neural network models, aiming to avoid actual measurements on the embedded side and predict the computational accuracy of models with different quantization parameters. We construct an accuracy predictor based on the self-attention mechanism to evaluate the quantization accuracy loss of neural network models with different bit widths. First, we use the Transformer structure to encode the feature maps of each layer in the quantized neural network and apply the attention mechanism to understand how much each layer of the neural network impacts the accuracy after quantization. Based on this, we implement the encoder and decoder based on the Transformer structure to generate single - image data instead of using the whole test set, thus significantly reducing the testing time.

The benefits of using the attention mechanism to evaluate the accuracy of quantized neural networks include:

Learning Relevance: By learning the importance of each layer of the neural network model after quantization, the self-attention mechanism can capture the intricate dependencies within the data, and automatically analyze and learn the factors affecting the accuracy of the quantized model.

Capturing Diverse Information: Each head can focus on different parts of the quantized data by attending to different parts of the sequence in parallel. For example, one head may focus on the rounding error caused by quantization, while another may focus on the quantization clipping error.

Enhancing Representational Capacity: Processing multiple aspects of the input simultaneously enables the model to form a more comprehensive understanding of the quantized data, resulting in better performance on complex tasks.

Improving Prediction Efficiency: It allows for parallel computation as all layers can be processed simultaneously, unlike Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short - Term Memory (LSTM) networks that process elements sequentially.

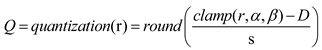

The accuracy evaluator we developed, as shown in

Figure 1, consists of two parts: an accuracy predictor based on the multi-head self-attention mechanism and a data generator based on the Transformer encoder and decoder. The entire training process is divided into two stages. The first stage is the training convergence of the accuracy predictor. For the trained mixed bit width quantization model and its test dataset, the output feature maps of each layer of the quantized model are processed with a histogram and then input into the accuracy predictor for training. The convergence condition is that the accuracy predictor outputs the prediction accuracy of the quantized model within the normal range. The second stage is the training convergence of the encoder - decoder and the data generator. Fixing the accuracy predictor from the first stage, we train the decoder and data generator of the Transformer structure. Then, we input the single-image generated by the data generator into the quantization model and generate the prediction accuracy through the output of the accuracy predictor.

2.2. Accuracy Predictor Based on Multi-Head Self-Attention

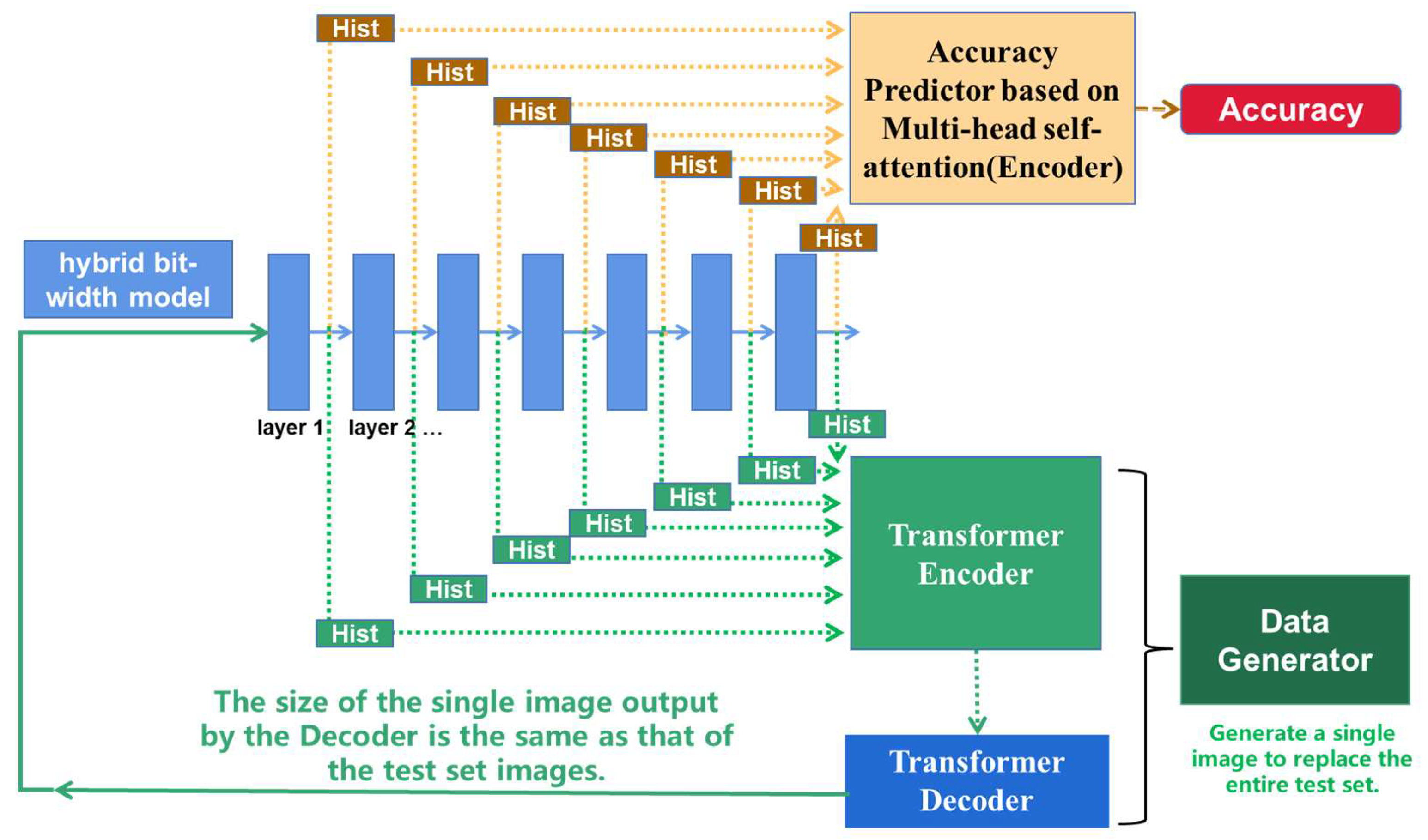

As depicted in the upper part of

Figure 1, the accuracy predictor, based on multi-head self-attention, takes a trained mixed bit-width quantized model as input. Here, both the quantization parameters and the quantization strategy can vary. The role of the accuracy evaluator is to forecast the accuracy of this input model. Initially, we must acquire the output feature maps of each layer of the input model. Given that the dimensionality of the feature maps for each layer differs, they are processed into a histogram matrix of a fixed dimensional size. We generate the histograms for the data from each layer of the quantized neural network model. In one branch of the histogram, the height represents the frequency of the data. Given the varying amounts of data in each layer of the neural network model, the other branch normalizes the histogram by converting the height to a rate. Subsequently, the two types of histograms are concatenated using the Concat operator and utilized as the input sequence to the Transformer Encoder, as shown in

Figure 2. Furthermore, the input sequence needs to be added with position encoding [

32]. For each position in the token embedding, the positional encoding is added as shown in (1).

where pos is the index of time step in the token embedding and d is the vector dimension.

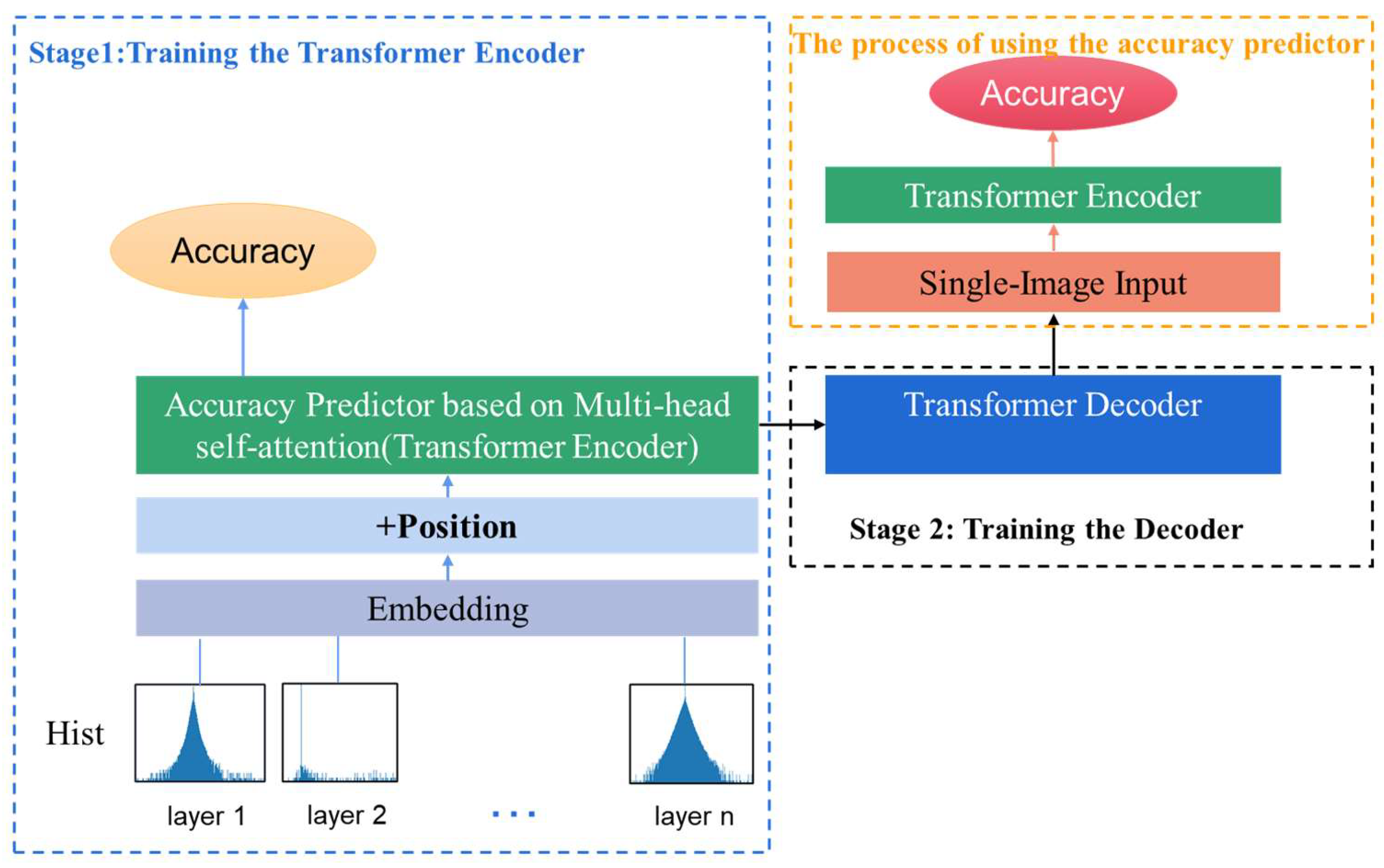

For each layer or operator of a neural network model, the processes of quantization, calculation, and dequantization are required. Quantization refers to the process of converting data from a floating-point type to an integer type, as indicated in (2). Dequantization, on the other hand, is the process of mapping the computation results of the integer type back to the corresponding floating-point type, as shown in (3). This is the method through which the floating-point results after quantization are obtained.

where r is the original floating-point value, Q is the integer value obtained after quantization, s and D are quantization parameters. Here, s represents the scaling factor, and D represents the zero point, which is selected in such a way that the value of 0 can be precisely mapped to quantized values. [

α,

β] is the clipping threshold for all the floating-point data of one layer. The clipping thresholds have a significant influence on the computation of quantization parameters. The clamp function is a mathematical function that constrains a given value within a specified range, which is referred to as the minimum bound and maximum bound. The round function is the fundamental function used to round numbers to the nearest integer.

Different quantization parameters will lead to different precision loss. We can analyze the influence of different quantization parameters on data distribution by the histograms. The processed histograms are then fed into the accuracy evaluator, and through the multi-head self-attention mechanism, autonomous training and learning commence. Using accuracy as the loss label, the accuracy evaluator is trained to assign coefficients to the output of each layer. It also learns the correlations among different feature maps in the input, thus completing the direct modeling from the mixed bit-width quantization model to task accuracy.

In the proposed method, the multi-head self-attention adopts the ViT (Vision Transformer) model [

33]. The concept of ViT involves segmenting an image into small patches. These patches are then used as a linear embedding and input into the Transformer, processed in a manner similar to tokens in NLP, with supervised training for image classification. The self-attention and multi-head self-attention (MHSA) [

32,

34] is shown in (4-6).We substitute the classification token with a token that outputs the prediction accuracy. Employing an attention-based mechanism to learn the feature maps of the quantization model's layers can enhance the ability to extract local features, to the extent that it reveals how different layers impact the quantization accuracy.

where Q, K and V represent Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) matrices of the self-attention mechanism respectively. The outputs from all heads {

,

, …

} are concatenated and passed through a single FC layer of dimensions W.

2.3. Data Generator Based on Transformer Encoder and Decoder

The data generator, depicted at the bottom of

Figure 1, is composed of an encoder and a decoder. It fuses the output feature maps of all the layers of the mixed bit-widths quantized model and inputs them into the Transformer-based encoder. The output of the encoder is used as the input of the decoder. The decoder outputs a single image that can represent the entire test set.

The encoder uses the self-attention mechanism to learn the correlation between the feature maps of the layers, which is in line with the principle of the accuracy predictor in the upper part of

Figure 1. It takes the fused feature maps from the data generator as input and processes them to generate an output that will be fed into the decoder.

The decoder component of the data generator consists of a stack of identical layers. Each layer contains a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a position-wise fully connected feed-forward network. Additionally, it features a masked self-attention module, which ensures that the predictions for a position can only depend on known outputs at positions preceding it. This helps maintain the auto-regressive nature of the sequence generation process. The Transformer decoder was first introduced by Ashish Vaswani et al [

32] and has since been widely used in computer vision tasks [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Our work that utilizes the Transformer decoder is inspired by the Masked Generative Image Transformer [

40]. The decoder of MaskGIT [

40] is designed based on a bidirectional Transformer architecture, incorporating various key operators to achieve efficient image generation functions. Its structure is built around a bidirectional self-attention mechanism, which can fully capture the global dependency relationships between image tokens and provide abundant contextual information for accurate token prediction. By integrating operators such as positional embedding and layer normalization, the model's performance is further optimized to ensure stable image generation during both training and inference processes. The decoder yields a solitary image capable of representing the entirety of the test set, so that the accuracy predictor can use the single representative image as the input for accuracy prediction in practical use, reducing the computational cost of the accuracy predictor, and improving the iterative efficiency of the development of neural network models.

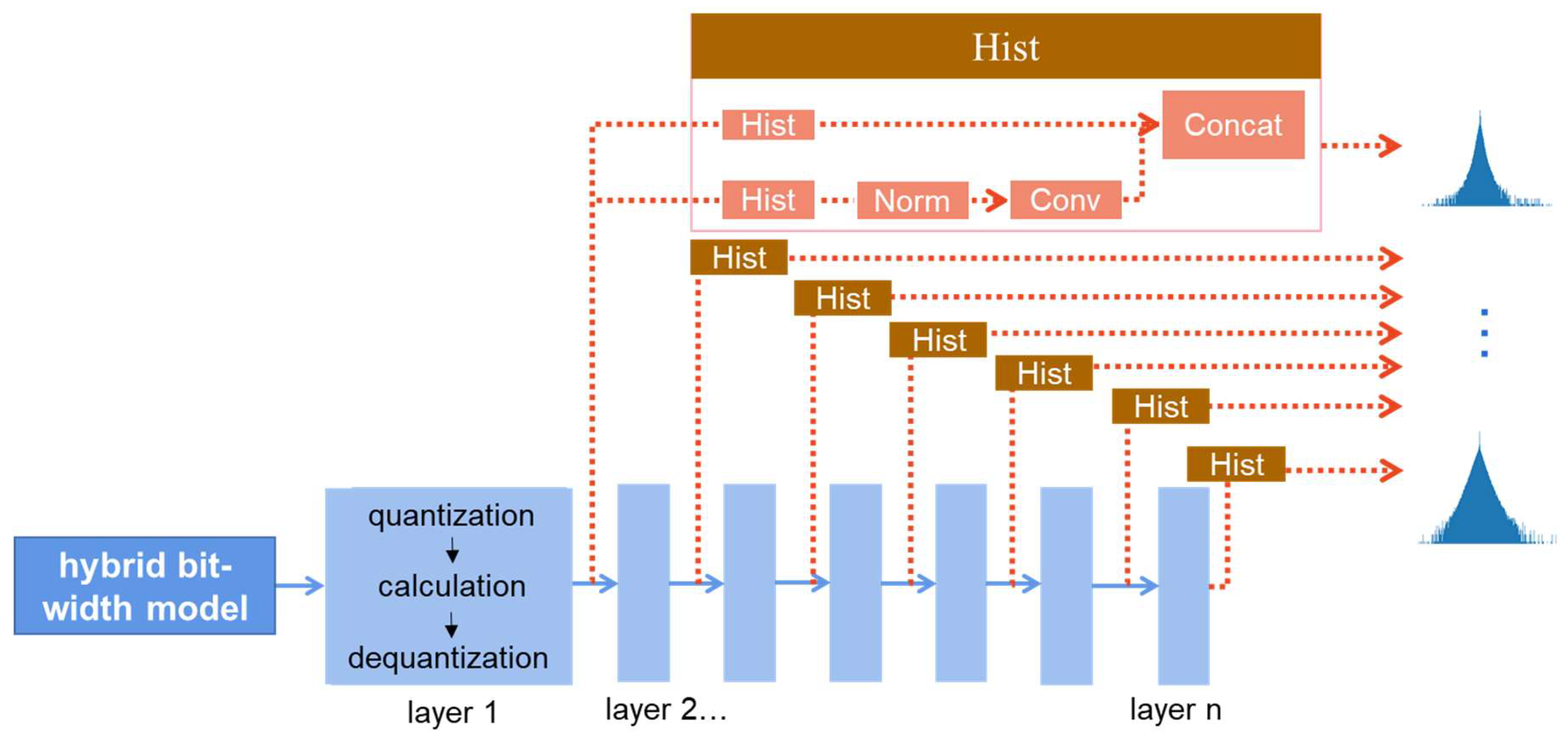

2.4. The Process of Training and Using the Accuracy Predictor

How to train and use the accuracy evaluator is shown in

Figure 3. The training is divided into two stages. In stage 1, multiple images are used as input and the Transformer Encoder is trained so that it can learn how much each layer of the neural network model affects the accuracy and get the predicted value of the accuracy. In stage 2, multiple images are used as input, the Transformer Encoder is fixed, and the Transformer Decoder is trained so that it can learn the features of the dataset and generate the single test image. After the training is completed, the accuracy predictor is used in such a way that the single test image is used as input, and the accuracy prediction value of the complete dataset is obtained after the transformer encoder.

3. Implementation and Experimental Results

3.1. Experimental Setting

In this research, we employ convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which have been trained on established datasets, to address the well-known problem of image classification. The CNN architectures selected for our experiments are MobileNetV2, ResNet50, and VGG16. To investigate the impact of quantization, the neural networks used in our experiments have been quantized to different bit-widths, namely INT8, INT4, and INT2, and also in mixed formats. It is crucial to note that each unique quantization parameter leads to a different level of accuracy, which forms a fundamental aspect of our study.

The core objective of our experimental design is to demonstrate the effectiveness of a newly developed quantization accuracy predictor. In the domain of image classification, we have adopted the Top-1 Accuracy as our evaluation metric. This metric calculates the proportion of cases where the model's top prediction matches the actual class, thus offering a straightforward and accurate measure of the model's performance.

Our validation is carried out on a computer system that features an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-8700K processor running at 3.70GHz, complemented by an NVIDIA GeForce GTX1070 graphics card. The proposed accuracy predictor is used to evaluate the performance of all quantized models. Subsequently, the predicted results are compared with the actual accuracy to determine the prediction error. It should be emphasized that the actual accuracy refers to the empirical label accuracy obtained through testing.

To our knowledge, this paper provides the first evidence demonstrating the efficacy of modeling for quantization accuracy prediction on image classification. Since the current evaluation of the accuracy of quantized models either requires testing the accuracy on a complete test set, which is time-consuming, or can only perform accuracy prediction on neural network models with specific structures, thus having application limitations. The method we provide uses a single image instead of the entire test set, and the accuracy of the quantized model can be evaluated without actual testing. Currently, there is a lack of similar methods. Therefore, we are unable to directly compare our predictor with existing quantization evaluation methods. Instead, we benchmark our predictor's accuracy against the empirical labels. This strategy allows us to assess the practical viability of our approach.

3.2. Dataset

The results presented in this section are derived from two datasets. The MobileNetV2 is evaluated using the UC Merced Land Use Dataset [

41]. The UC Merced Land Use Dataset is widely recognized in the fields of computer vision and machine learning, particularly for tasks associated with land cover classification and urban mapping. It was developed by the University of California, Merced, and consists of a set of high-resolution aerial images that showcase various land use patterns in the city of Merced, California. This dataset stands out due to its high spatial resolution, approximately 0.5 meters per pixel, which enables the identification of small and detailed features typical of different land use types. The images are large, typically measuring 1000 x 1000 pixels, providing abundant visual information for analysis. It encompasses 21 distinct land use categories, ranging from urban features like commercial and residential areas to natural landscapes such as grasslands, trees, and water bodies. The complexity and variability of urban landscapes within this dataset make it a challenging yet valuable resource for testing the robustness and accuracy of algorithms.

For ResNet50 and VGG16, we utilize the CIFAR-10 dataset [

42]. The CIFAR-10 dataset comprises 60,000 32x32 color images, divided into 10 different classes, with 6,000 images per class. This dataset is a staple in machine learning research for image classification tasks and serves as a benchmark for evaluating various algorithms' performance. CIFAR-10 poses a challenge due to the variety and complexity of its images. Given their small size, the task of image classification becomes more difficult compared to using larger images. Additionally, there is significant intra-class variation, meaning that objects within the same class can have diverse appearances. Researchers and practitioners frequently use CIFAR-10 to experiment with different image processing techniques, feature extraction methods, and machine learning models. It has been instrumental in the development and testing of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which have proven highly effective for image classification tasks.

3.3. Main Results

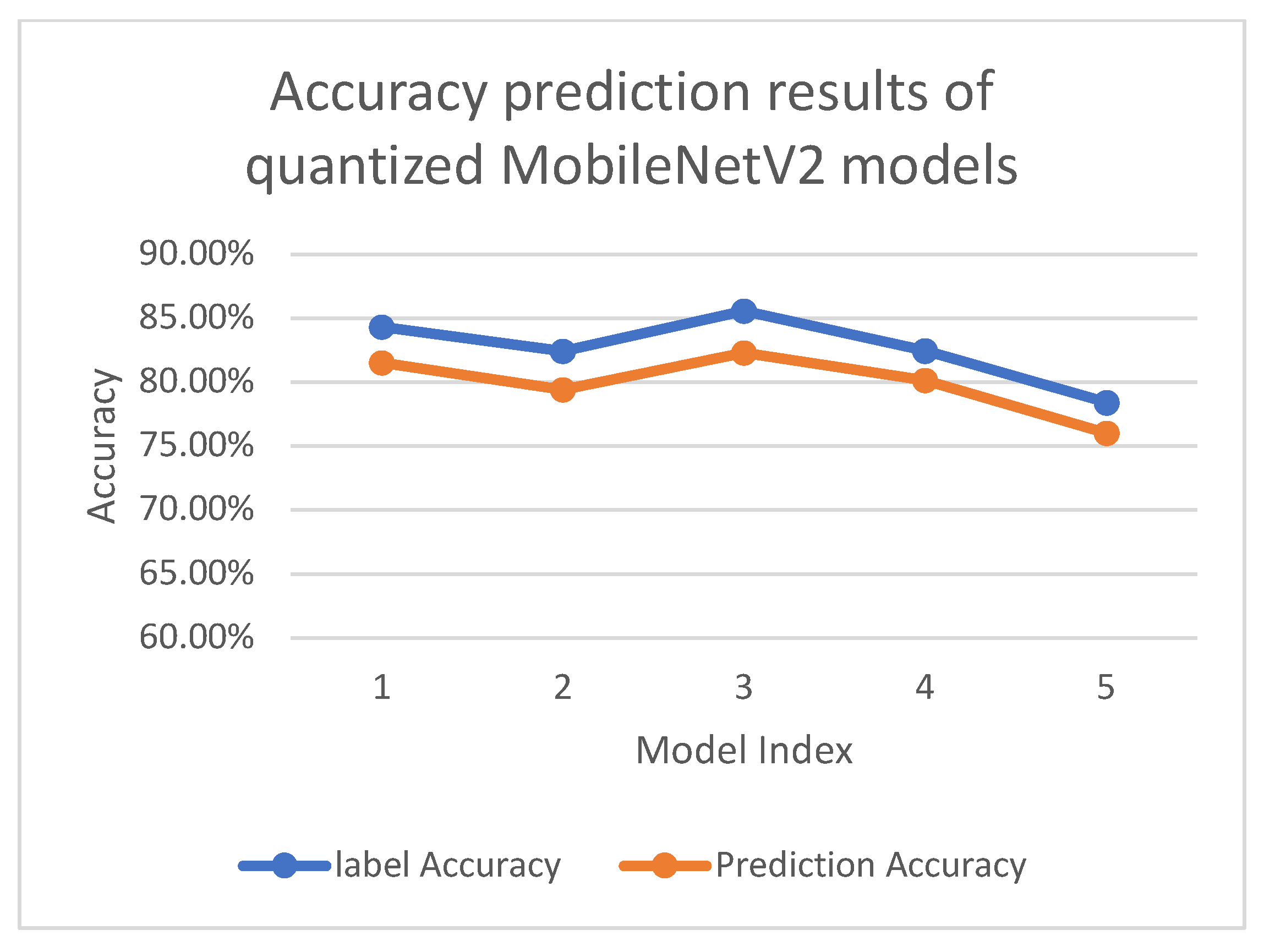

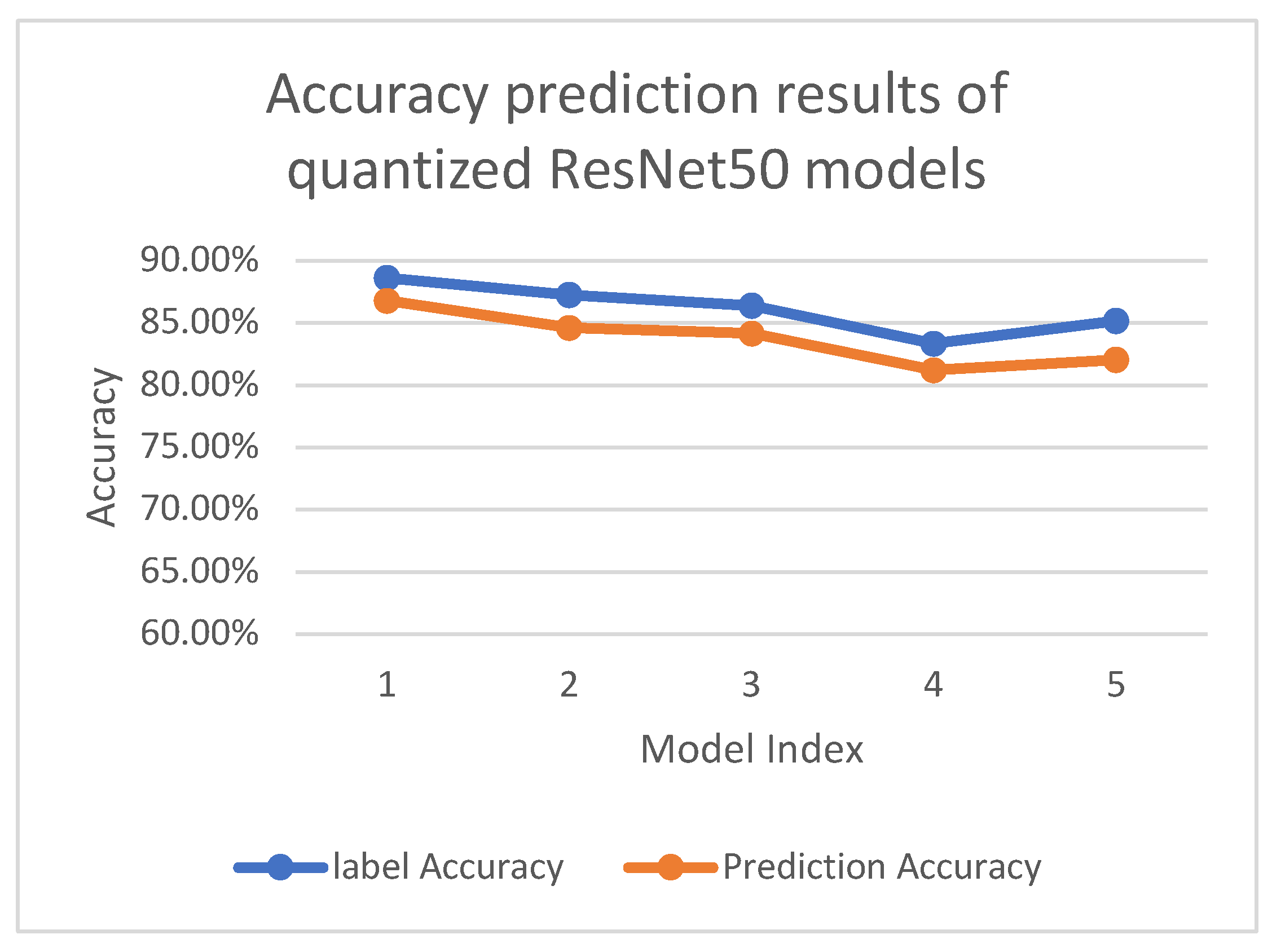

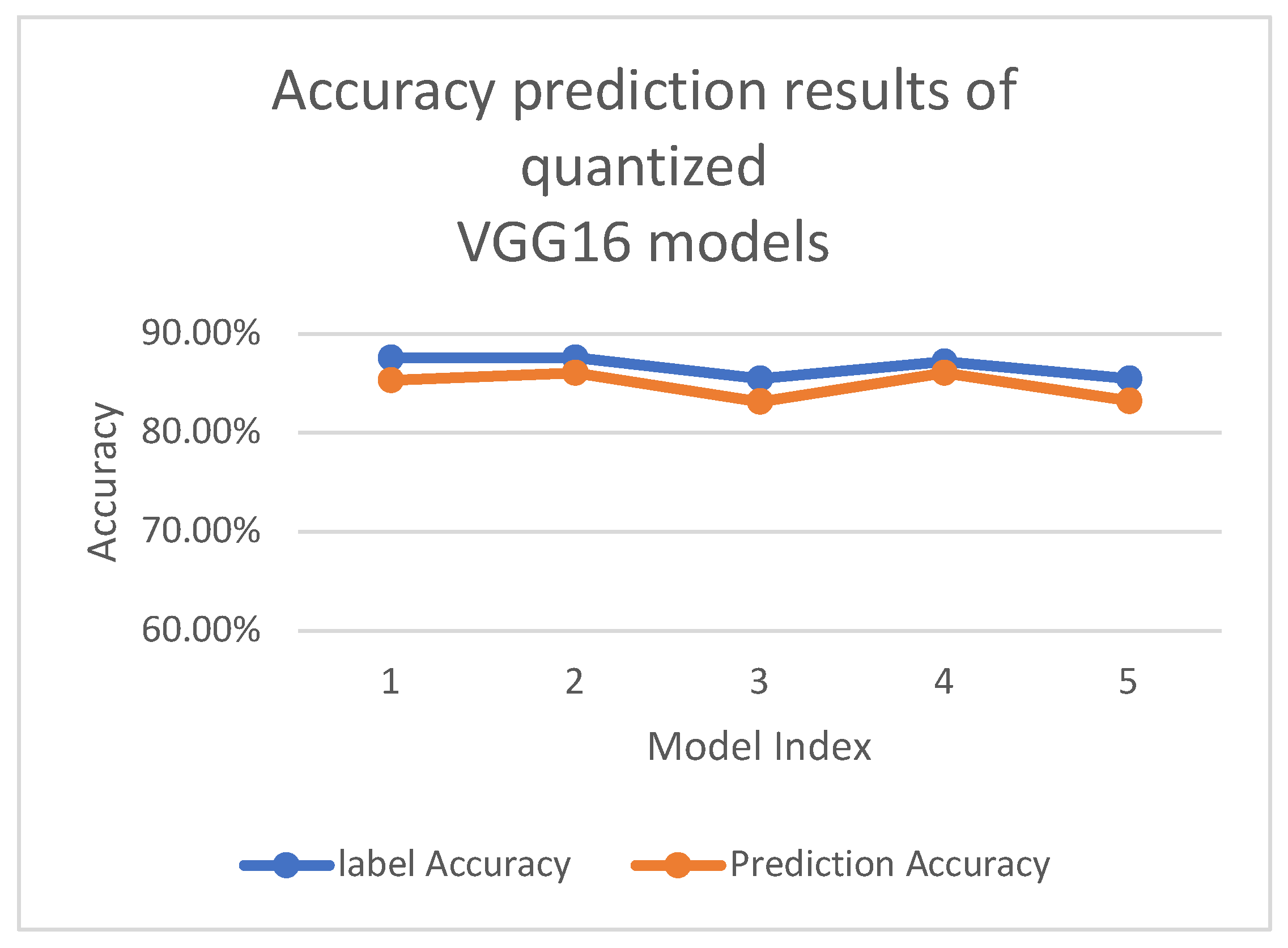

Using a single image as input, our trained accuracy predictor is used to measure the precision of several models with different quantization parameters. For MobileNetV2, we observe an average prediction error of 2.77%, with detailed results presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 4. For ResNet50, the average prediction error is 2.40%, as shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 5. For VGG16, the average prediction error is 1.89% presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 6. The reason why VGG16 performs better is that its model structure is a straightforward type, which is more friendly to quantization. Our findings emphasize the efficacy of our proposed method in predicting the quantization accuracy of neural network models within classification tasks. The proposed predictor is highly capable of quickly assessing the influence of input data, quantization parameters, bit-widths, and model architecture on the accuracy of neural network models. It exhibits versatility, being able to handle neural networks with diverse architectures and various quantization schemes, thereby enhancing its value in the field of machine learning.

3.4. Ablation Study

As depicted in

Figure 1, the accuracy evaluator for the quantized neural networks we developed is composed of two parts. One is an accuracy predictor founded on the multi-head self-attention mechanism, and the other is a data generator based on the Transformer encoder and decoder. The accuracy predictor in the first part can predict the accuracy of the neural network model after quantization. The data generator in the second part can generate a single image that represents the entire test set. Using this image as the input, the accuracy of the quantized model can be evaluated by the predictor in the first part, which significantly shortens the prediction time. We conduct the ablation study regarding whether using the single representative image. The results of the ablation experiment are shown in

Table 4.

The experimental results turned out as expected. In the "Part 1 + Part 2" approach, a single image generated by the data generator serves as a substitute for the entire test set. This significantly reduces the time needed for accuracy prediction, though at the expense of a minor drop in prediction accuracy. When compared with "Part 1", "Part 1 + Part 2" shows an average accuracy prediction loss of 0.56% across three different types of neural network models. If the priority is to enhance the speed of the predictor, the comprehensive "Part 1 + Part 2" method proposed in this paper is a viable option. On the other hand, if the focus is on maximizing the accuracy of the accuracy predictor, it is advisable to solely adopt the method presented in "Part 1".