Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

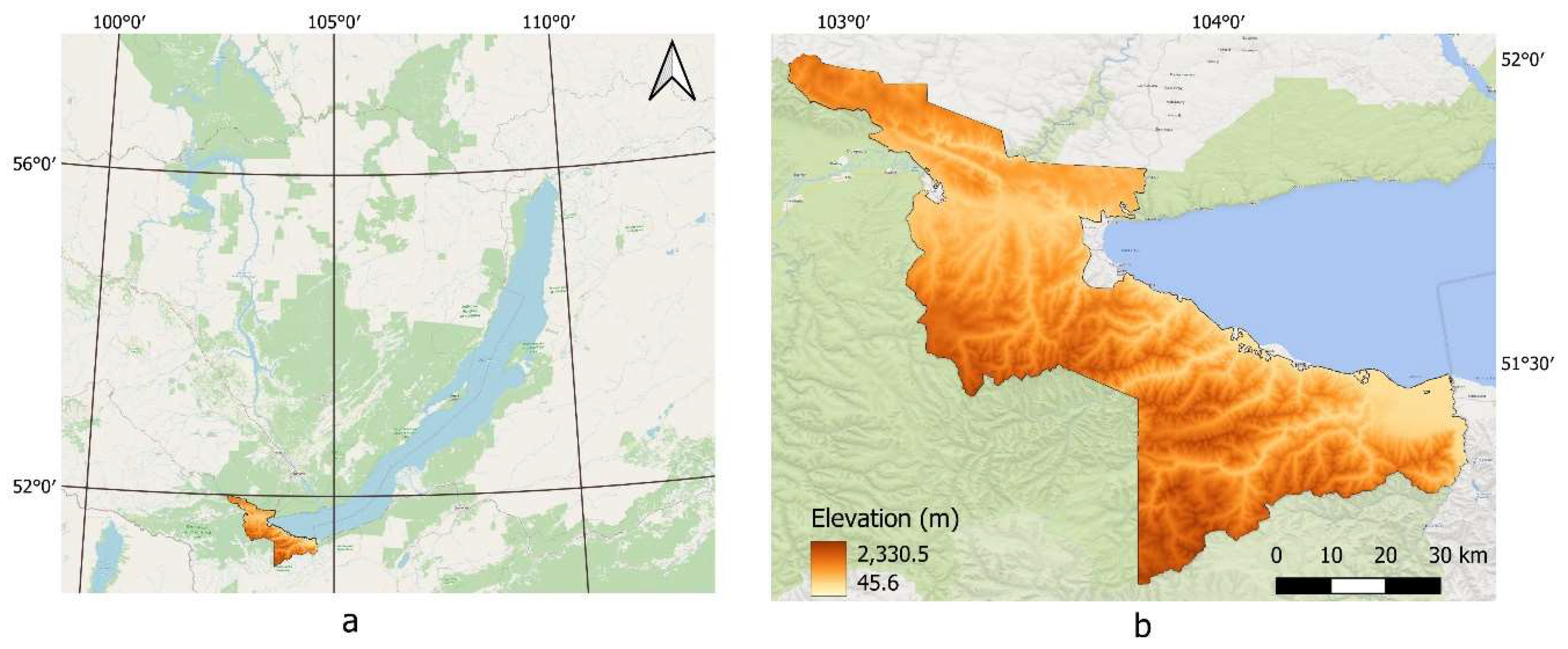

2.1. Data for Training

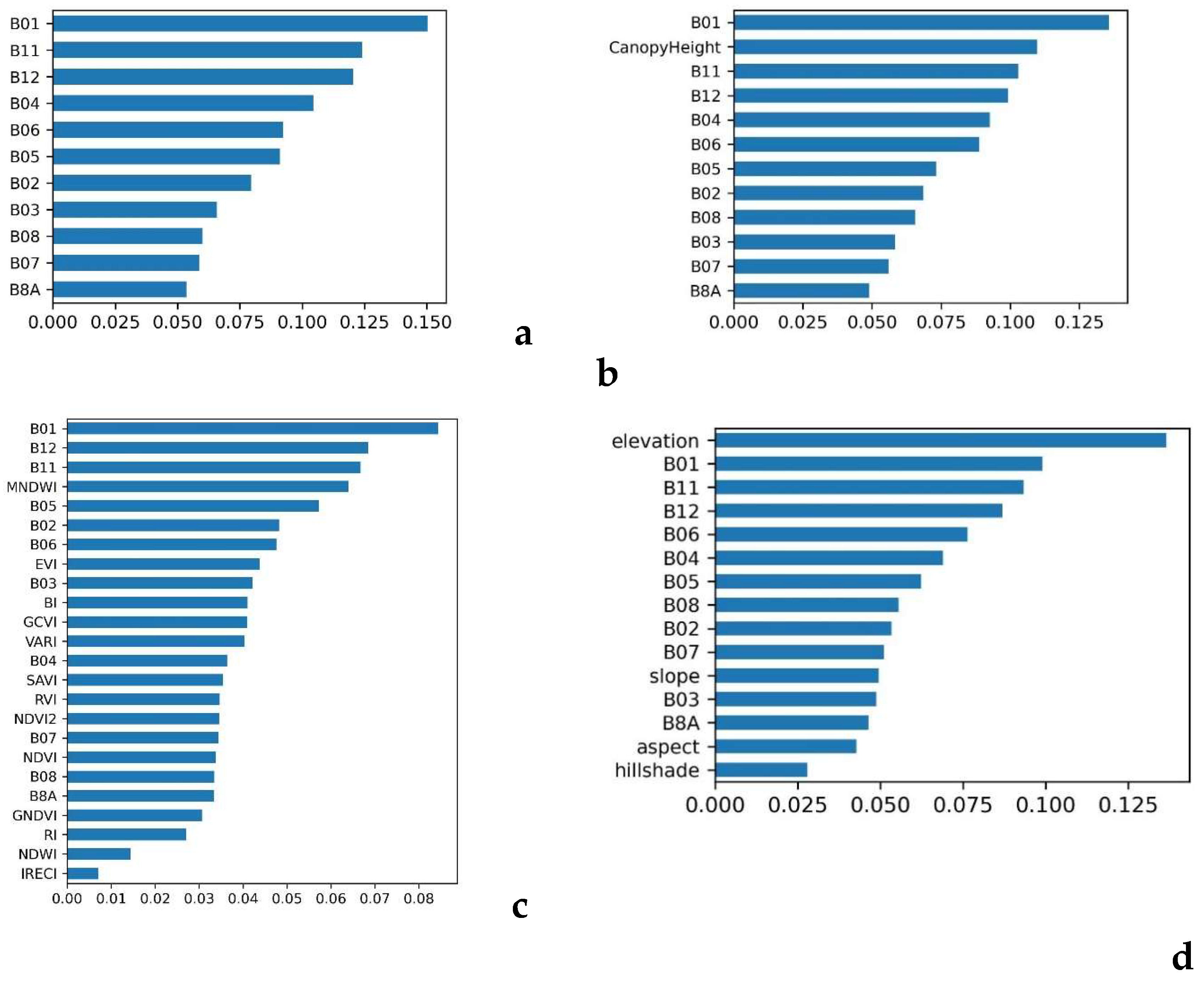

Vegetation Indices

Soil Data

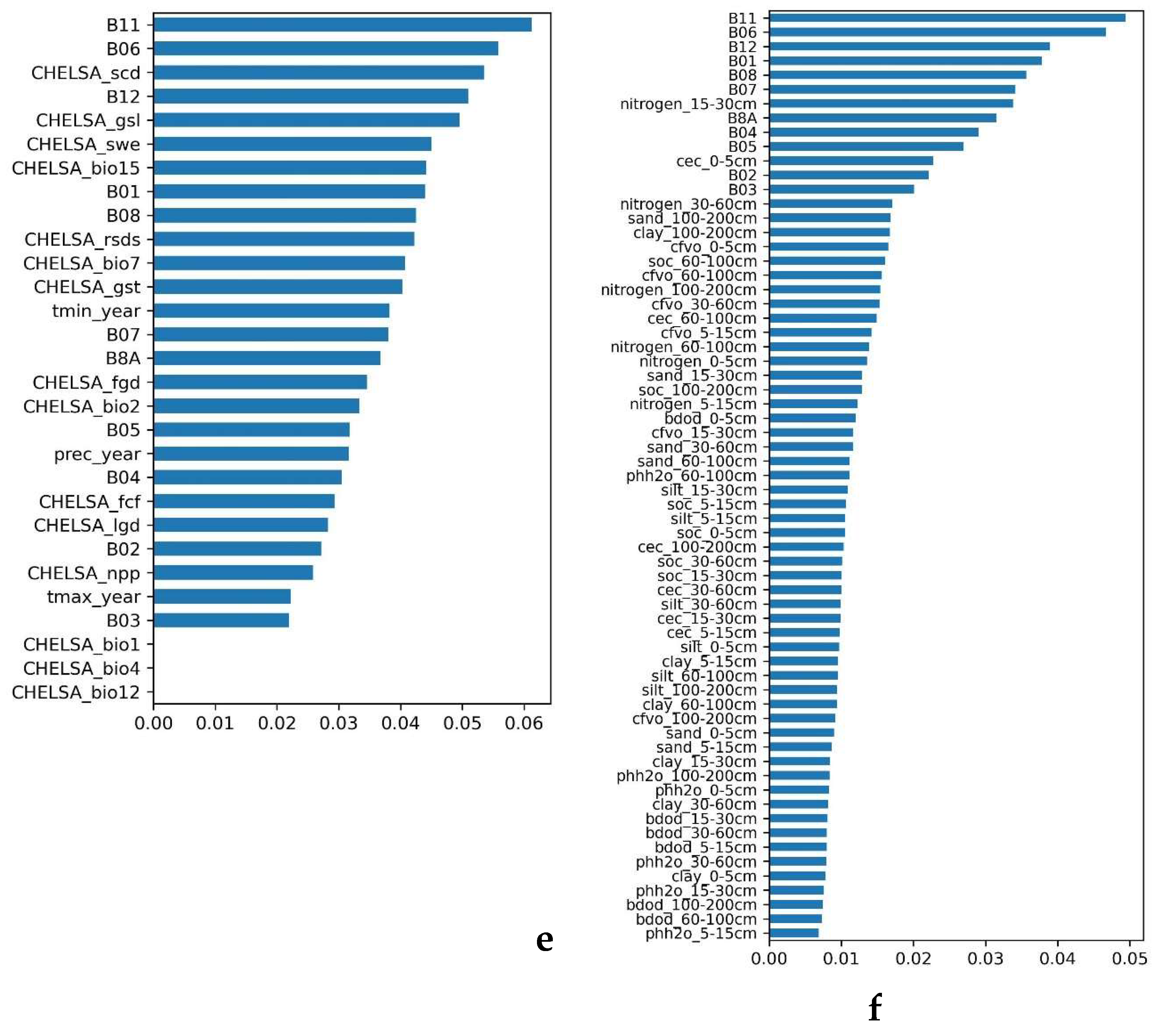

Climate Data

Topographic Data

Forest Canopy Height

2.2. Model Evaluation

2.3. Features Combinations

2.4. Training Dataset

2.5. Data Preprocessing

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Auxiliary Data on Model Performance

4.2. Limitations of the Method and Future Development

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pu, R. Mapping Tree Species Using Advanced Remote Sensing Technologies: A State-of-the-Art Review and Perspective. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 2021, 9812624. [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B. Forests, Climate, and Public Policy: A 500-Year Interdisciplinary Odyssey. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016, 47, 97–121. [CrossRef]

- Chiarucci, A.; Piovesan, G. Need for a Global Map of Forest Naturalness for a Sustainable Future. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 368–372. [CrossRef]

- H. Nguyen, T.; Jones, S.; Soto-Berelov, M.; Haywood, A.; Hislop, S. Landsat Time-Series for Estimating Forest Aboveground Biomass and Its Dynamics across Space and Time: A Review. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 98. [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, S.; Singha, P.; Mahato, S.; Shahfahad; Pal, S.; Liou, Y.-A.; Rahman, A. Land-Use Land-Cover Classification by Machine Learning Classifiers for Satellite Observations—A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1135. [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, I.; Popova, A. Forest Landscape Model Initialization with Remotely Sensed-Based Open-Source Databases in the Absence of Inventory Data. Forests 2023, 14, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Grabska, E.; Hostert, P.; Pflugmacher, D.; Ostapowicz, K. Forest Stand Species Mapping Using the Sentinel-2 Time Series. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1197. [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Zeng, J.; Li, Y. Tree Species Classification Based on Sentinel-2 Imagery and Random Forest Classifier in the Eastern Regions of the Qilian Mountains. Forests 2021, 12, 1736. [CrossRef]

- Hartling, S.; Sagan, V.; Sidike, P.; Maimaitijiang, M.; Carron, J. Urban Tree Species Classification Using a WorldView-2/3 and LiDAR Data Fusion Approach and Deep Learning. Sensors 2019, 19, 1284. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bretz, M.; Dewan, M.A.A.; Delavar, M.A. Machine Learning in Modelling Land-Use and Land Cover-Change (LULCC): Current Status, Challenges and Prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153559. [CrossRef]

- Wessel, M.; Brandmeier, M.; Tiede, D. Evaluation of Different Machine Learning Algorithms for Scalable Classification of Tree Types and Tree Species Based on Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1419. [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, A.; Lindberg, E.; Reese, H.; Olsson, H. Tree Species Classification Using Sentinel-2 Imagery and Bayesian Inference. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 100, 102318. [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, I.V.; Ruzhnikov, G.M.; Fedorov, R.K.; Popova, A.K.; Avramenko, Y.V. On Classification of Sentinel-2 Satellite Images by a Neural Network ResNet-50. Comput. Opt. 2023, 47, 474–481. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Kim, K.-M.; Kim, E.-H.; Jin, R. Machine Learning for Tree Species Classification Using Sentinel-2 Spectral Information, Crown Texture, and Environmental Variables. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2049. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gong, W.; Xing, Y.; Hu, X.; Gong, J. Estimation of the Forest Stand Mean Height and Aboveground Biomass in Northeast China Using SAR Sentinel-1B, Multispectral Sentinel-2A, and DEM Imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 151, 277–289. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M.; Dostálová, A.; Hollaus, M.; Atzberger, C.; Immitzer, M. Combination of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Data for Tree Species Classification in a Central European Biosphere Reserve. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2687. [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Tsendbazar, N.-E.; Herold, M.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Li, L. Improving the Characterization of Global Aquatic Land Cover Types Using Multi-Source Earth Observation Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 278, 113103. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Li, R.; Sun, X. Exploring the Differences in Tree Species Classification between Typical Forest Regions in Northern and Southern China. Forests 2024, 15, 929. [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Huang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y. Forest Tree Species Classification Based on Sentinel-2 Images and Auxiliary Data. Forests 2022, 13, 1416. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.-H.; Valdez, M. Tree Species Classification by Integrating Satellite Imagery and Topographic Variables Using Maximum Entropy Method in a Mongolian Forest. Forests 2019, 10, 961. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lu, D.; Li, G.; Chen, E. Classification of Land Cover, Forest, and Tree Species Classes with ZiYuan-3 Multispectral and Stereo Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 164. [CrossRef]

- Vorovencii, I. Assessing Various Scenarios of Multitemporal Sentinel-2 Imagery, Topographic Data, Texture Features, and Machine Learning Algorithms for Tree Species Identification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 15373–15392. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Fang, P.; Wang, L.; Ou, G.; Xu, W.; Dai, F.; Dai, Q. Synergism of Multi-Modal Data for Mapping Tree Species Distribution—A Case Study from a Mountainous Forest in Southwest China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 979. [CrossRef]

- Appendix 28 to the order of the Ministry of the Forestry Complex of the Irkutsk Region dated 28 January 2022 No. 91-7-mpr. In Forest Regulations Slyudyanskoye Forestry of the Irkutsk Region; Branch of FSBI “Roslesinforg” “Vostsiblesproekt”: Krasnoyarsk, Russia, 2021; p. 542.

- Campos-Taberner, M.; García-Haro, F.J.; Martínez, B.; Izquierdo-Verdiguier, E.; Atzberger, C.; Camps-Valls, G.; Gilabert, M.A. Understanding Deep Learning in Land Use Classification Based on Sentinel-2 Time Series. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Qiang, Z.; Xu, W.; Fan, J. A New Forest Growing Stock Volume Estimation Model Based on AdaBoost and Random Forest Model. Forests 2024, 15, 260. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Liu, S.; Feng, W.; Dauphin, G. Feature Importance Ranking of Random Forest-Based End-to-End Learning Algorithm. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5203. [CrossRef]

- Immitzer, M.; Vuolo, F.; Atzberger, C. First Experience with Sentinel-2 Data for Crop and Tree Species Classifications in Central Europe. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 166. [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.M. Land Cover and Land Use Classification Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms in a Boreal Landscape Using Sentinel-2 Data. GIScience Remote Sens. 2020, 57, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Mensah, S.; Noulèkoun, F.; Dimobe, K.; Seifert, T.; Glèlè Kakaï, R. Climate and Soil Effects on Tree Species Diversity and Aboveground Carbon Patterns in Semi-Arid Tree Savannas. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11509. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Atzberger, C.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, M.; Wang, X. Zanthoxylum Bungeanum Maxim Mapping with Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Images: The Importance of Different Features and Consistency of Results. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 174, 68–86. [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.; Jetz, W.; Schindler, K.; Wegner, J.D. A High-Resolution Canopy Height Model of the Earth. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 1778–1789. [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Herold, M.; Stehman, S. V.; Woodcock, C.E.; Wulder, M.A. Good Practices for Estimating Area and Assessing Accuracy of Land Change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 42–57. [CrossRef]

- Schepaschenko, D.G.; Shvidenko, A.Z.; Lesiv, M.Y.; Ontikov, P. V.; Shchepashchenko, M. V.; Kraxner, F. Estimation of Forest Area and Its Dynamics in Russia Based on Synthesis of Remote Sensing Products. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2015, 8, 811–817. [CrossRef]

- Persson, M.; Lindberg, E.; Reese, H. Tree Species Classification with Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1794. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, C.; Meng, R.; Pang, Y.; Jia, W.; Zhou, J.; Huang, Z.; Fang, L.; Zhao, F. Assessing Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 Spectral-Temporal Features for Mapping Tree Species of Northern Plantation Forests in Heilongjiang Province, China. For. Ecosyst. 2022, 9, 100032. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.F.; Brumby, S.P.; Guzder-Williams, B.; Birch, T.; Hyde, S.B.; Mazzariello, J.; Czerwinski, W.; Pasquarella, V.J.; Haertel, R.; Ilyushchenko, S.; et al. Dynamic World, Near Real-Time Global 10 m Land Use Land Cover Mapping. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 251. [CrossRef]

- Gao, B. NDWI—A Normalized Difference Water Index for Remote Sensing of Vegetation Liquid Water from Space. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 257–266. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Yan, K.; Liu, J.; Pu, J.; Zou, D.; Qi, J.; Mu, X.; Yan, G. Assessment of Remote-Sensed Vegetation Indices for Estimating Forest Chlorophyll Concentration. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 162, 112001. [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Tang, Y.; Jing, L.; Li, H.; Qiu, F.; Wu, W. Tree Species Classification of Forest Stands Using Multisource Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Shvidenko, A.; Schepaschenko, D.; Nilsson, S. Tables and Models of Growth and Productivity of Forests of Major Forest Forming Species of Northern Eurasia (Standard and Reference Materials); ); Federal Agency of Forest Management, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis: Moscow, 2008; p. 886.

- Lu, D.; Weng, Q. A Survey of Image Classification Methods and Techniques for Improving Classification Performance. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 823–870. [CrossRef]

- Rota, F.; Scherrer, D.; Bergamini, A.; Price, B.; Walthert, L.; Baltensweiler, A. Unravelling the Impact of Soil Data Quality on Species Distribution Models of Temperate Forest Woody Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 944, 173719. [CrossRef]

- Levula, J.; Ilvesniemi, H.; Westman, C. Relation between Soil Properties and Tree Species Composition in a Scots Pine–Norway Spruce Stand in Southern Finland. Silva Fenn. 2003, 37, 205–218. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, B.; Xian, M.; Zhou, S.; Huang, C.; Cui, X. Prediction of Future Potential Distributions of Pinus Yunnanensis Varieties under Climate Change. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2023, 6, 1308416. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, Q.; Guan, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Mi, J.; Yang, E. Quantifying the Nonlinear Response of Vegetation Greening to Driving Factors in Longnan of China Based on Machine Learning Algorithm. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110277. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xiang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Long, Y.; Yang, S.; Luo, X. Modeling the Impacts of Climate Change on Potential Distribution of Betula Luminifera H. Winkler in China Using MaxEnt. Forests 2024, 15, 1624. [CrossRef]

| Data type | Dataset features | Features | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation indices | 13 indices | NDVI | |

| RVI | |||

| NDWI | |||

| RI | |||

| EVI | |||

| GNDVI | |||

| IRECI | |||

| BI | |||

| GCVI | |||

| MNDWI | |||

| NDVI2 | |||

| SAVI | |||

| VARI | |||

| Soil | Soilgrids, 9 features, for each of the 6 depth intervals, total 54 features |

bdod | Bulk density of the fine earth fraction, cg/cm³ |

| cec | Cation Exchange Capacity, mmol(c)/kg | ||

| cfvo | Volumetric fraction of coarse fragments (> 2 mm), cm3/dm3 | ||

| clay | Proportion of clay particles (< 0.002 mm), g/kg | ||

| nitrogen | Total nitrogen, cg/kg | ||

| phh2o | Soil pH | ||

| sand | Proportion of sand particles (> 0.05 mm), g/kg | ||

| silt | Proportion of silt particles (≥ 0.002 mm and ≤ 0.05 mm), g/kg | ||

| soc | Soil organic carbon content, dg/kg | ||

| Climate | WorldClim, 3 features |

tmax | Average maximum temperature, °C |

| tmin | Average minimum temperature, °C | ||

| precepitation | Precipitation amount, mm | ||

| Chelsa, 15 features |

bio1 | Mean annual air temperature, °C | |

| bio2 | Mean diurnal air temperature range, °C | ||

| bio4 | Temperature seasonality (standard deviation of the monthly mean temperatures), °C/100 | ||

| bio7 | Annual range of air temperature, °C | ||

| bio12 | Annual precipitation amount, kg/m2 | ||

| bio15 | Precipitation seasonality, kg/m2 | ||

| fcf | Frost change frequency | ||

| fgd | First day of the growing season | ||

| gsl | Growing season length | ||

| gst | Mean temperature of the growing season, °C | ||

| lgd | Last day of the growing season | ||

| npp | Net primary productivity, gC/m2 | ||

| rsds_mean | Mean monthly surface downwelling shortwave flux in air, MJ/m2 | ||

| scd | Snow cover days | ||

| swe | Snow water equivalent, kg/m2 | ||

| Topography | Copernicus Digital Surface Model (DEM), 4 features |

aspect | Orientation of the slope in degrees |

| slope | Relief slope angle | ||

| hillshade | Terrain shading | ||

| elevation | Elevation above sea level | ||

| Forest canopy height | ETH Global Sentinel-2 10m Canopy Height, 1 feature |

CanopyHeight | Global forest canopy height |

| Total 90 auxiliary features | |||

| Model | Features combinations | Number of features |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sentinel-2 bands | 11 |

| 2 | Sentinel-2 + vegetation indices (S2+VI) | 24 |

| 3 | Sentinel-2 + Canopy height (S2+CH) | 12 |

| 4 | Sentinel-2 + topographic features (S2+topo) | 15 |

| 5 | Sentinel-2 + climate features (S2+clim) | 29 |

| 6 | Sentinel-2 + soil features (S2+Soil) | 65 |

| 7 | All collected features | 101 |

| 8 | Set of selected features | 98 |

| Model | Overall accuracy, % | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2 | 49.59 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.53 |

| S2+VI | 49.93 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.53 |

| S2+CH | 51.86 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.56 |

| S2+topo | 55.86 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.61 |

| S2+Clim | 67.38 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| S2+Soil | 69.86 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| 101 features | 78.8 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| 98 features | 80.69 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

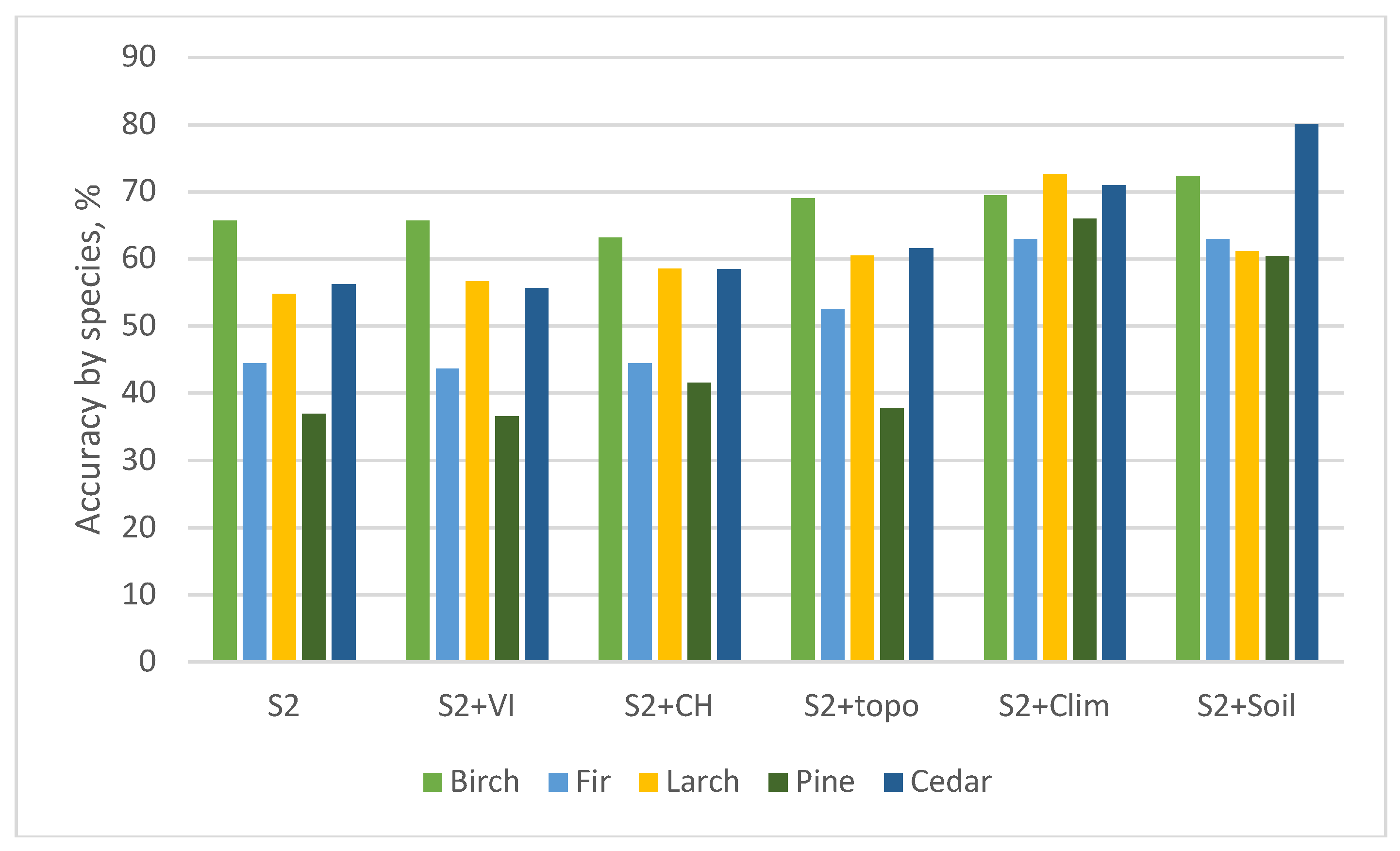

| Tree species | S2 | S2+VI | S2+CH | S2+topo | S2+Clim | S2+Soil | 101 | 98 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birch | 65.69 | 65.69 | 63.18 | 69.04 | 69.46 | 72.38 | 76.57 | 79.92 |

| Fir | 44.44 | 43.7 | 44.44 | 52.59 | 62.96 | 62.96 | 82.22 | 83.7 |

| Larch | 54.78 | 56.69 | 58.6 | 60.51 | 72.61 | 61.15 | 79.62 | 80.89 |

| Pine | 36.97 | 36.55 | 41.6 | 37.82 | 65.97 | 60.50 | 79.83 | 80.67 |

| Cedar | 56.25 | 55.68 | 58.52 | 61.65 | 71.02 | 80.11 | 82.10 | 84.66 |

| Average by species | 51.63 | 51.66 | 53.27 | 56.32 | 68.40 | 67.42 | 80.07 | 81.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).