Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Detection of CoVs in the Feces of Black-Headed Gulls

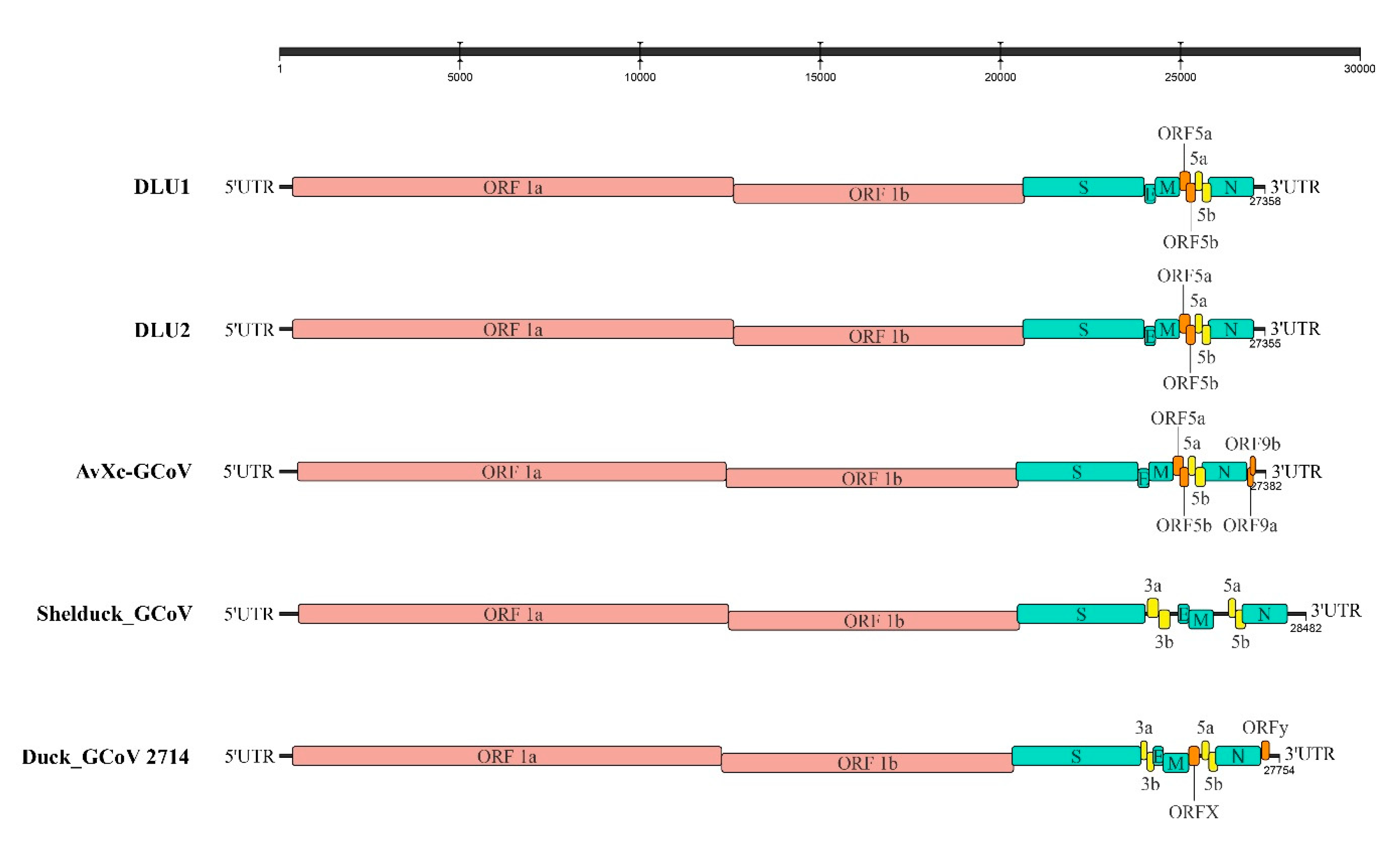

2.2. Whole-Genome Structural Analysis of BHG-GCoVs

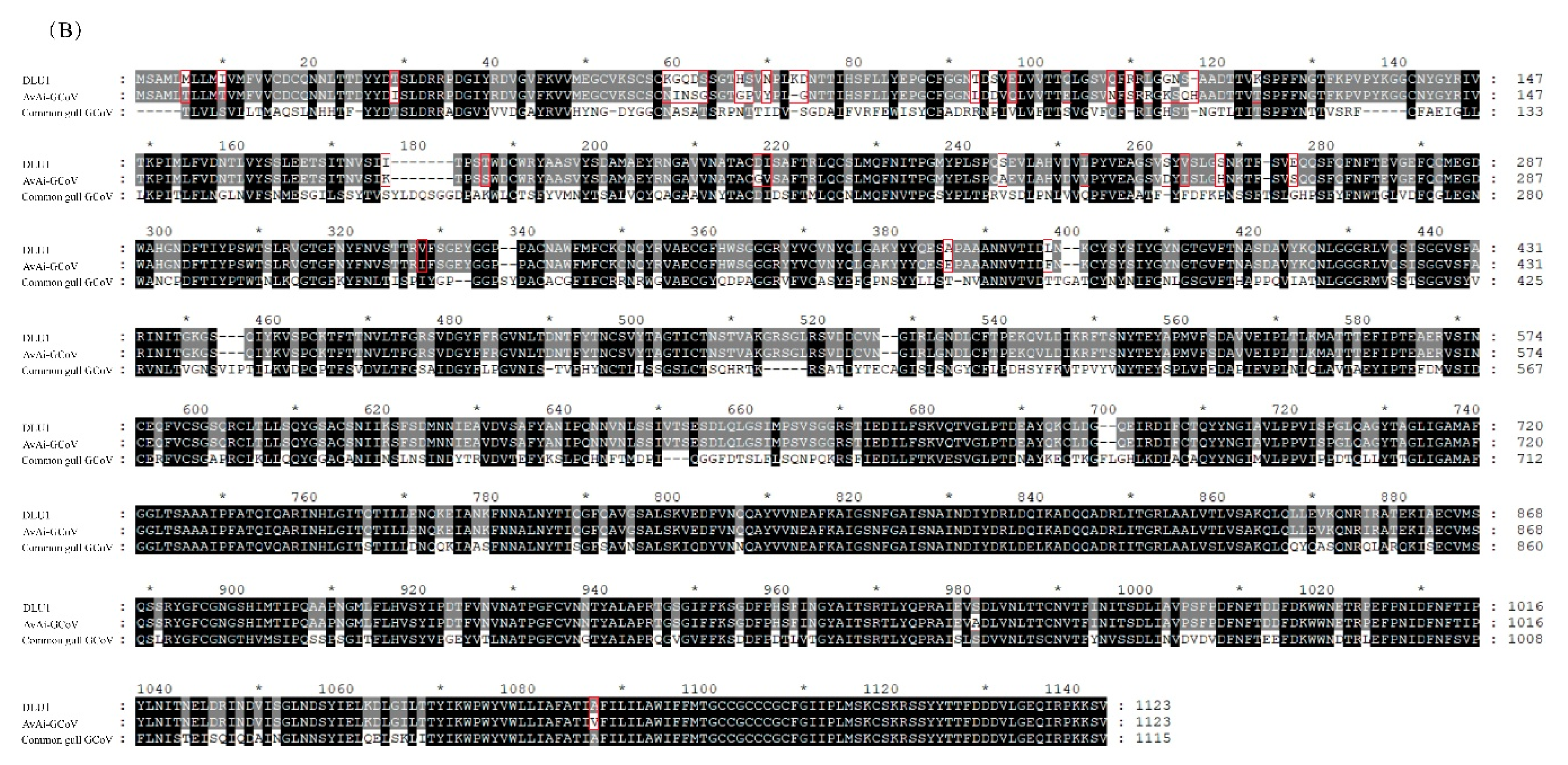

2.3. Genome Similarity Analysis of BHG-GCoVs.

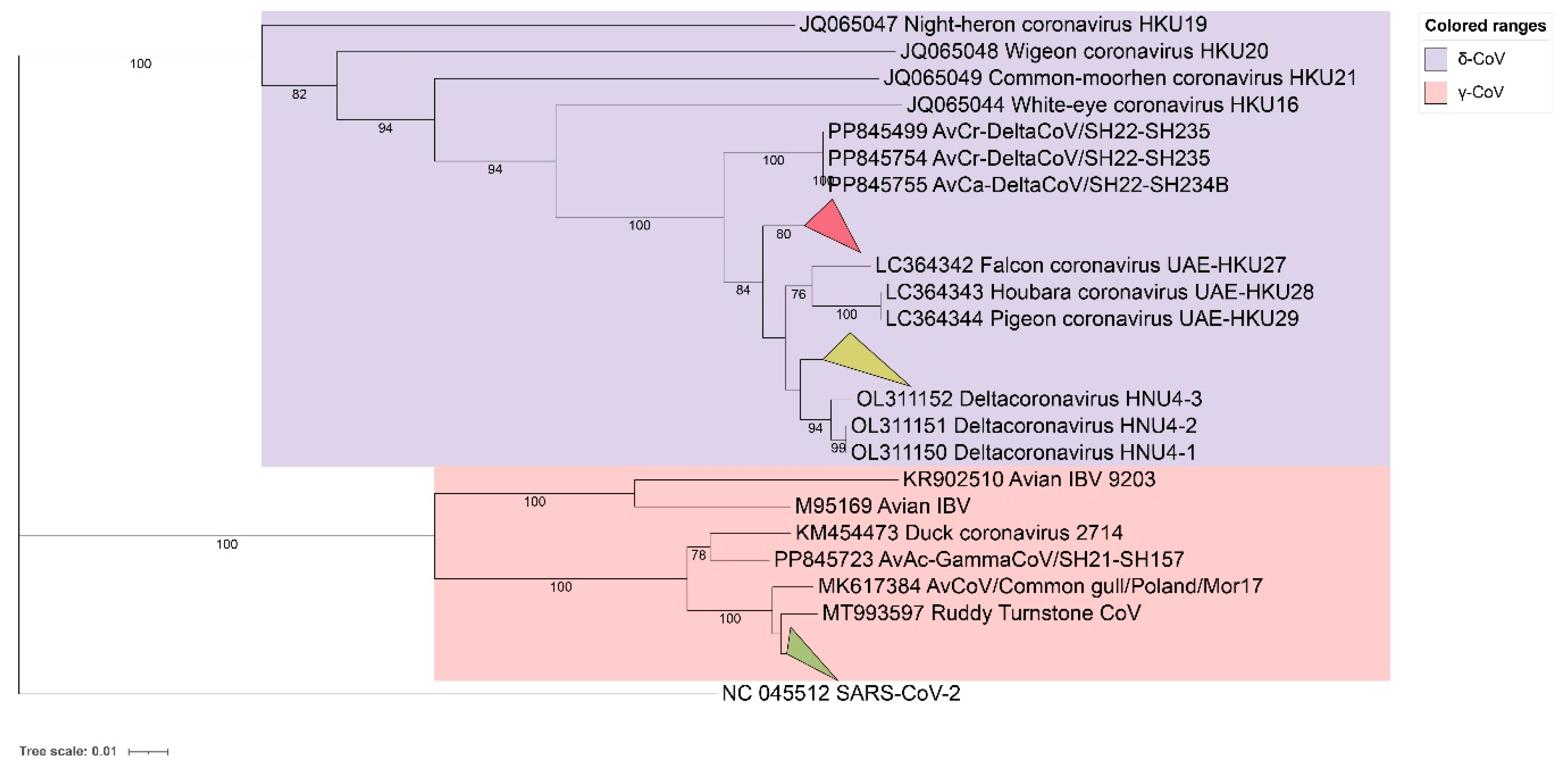

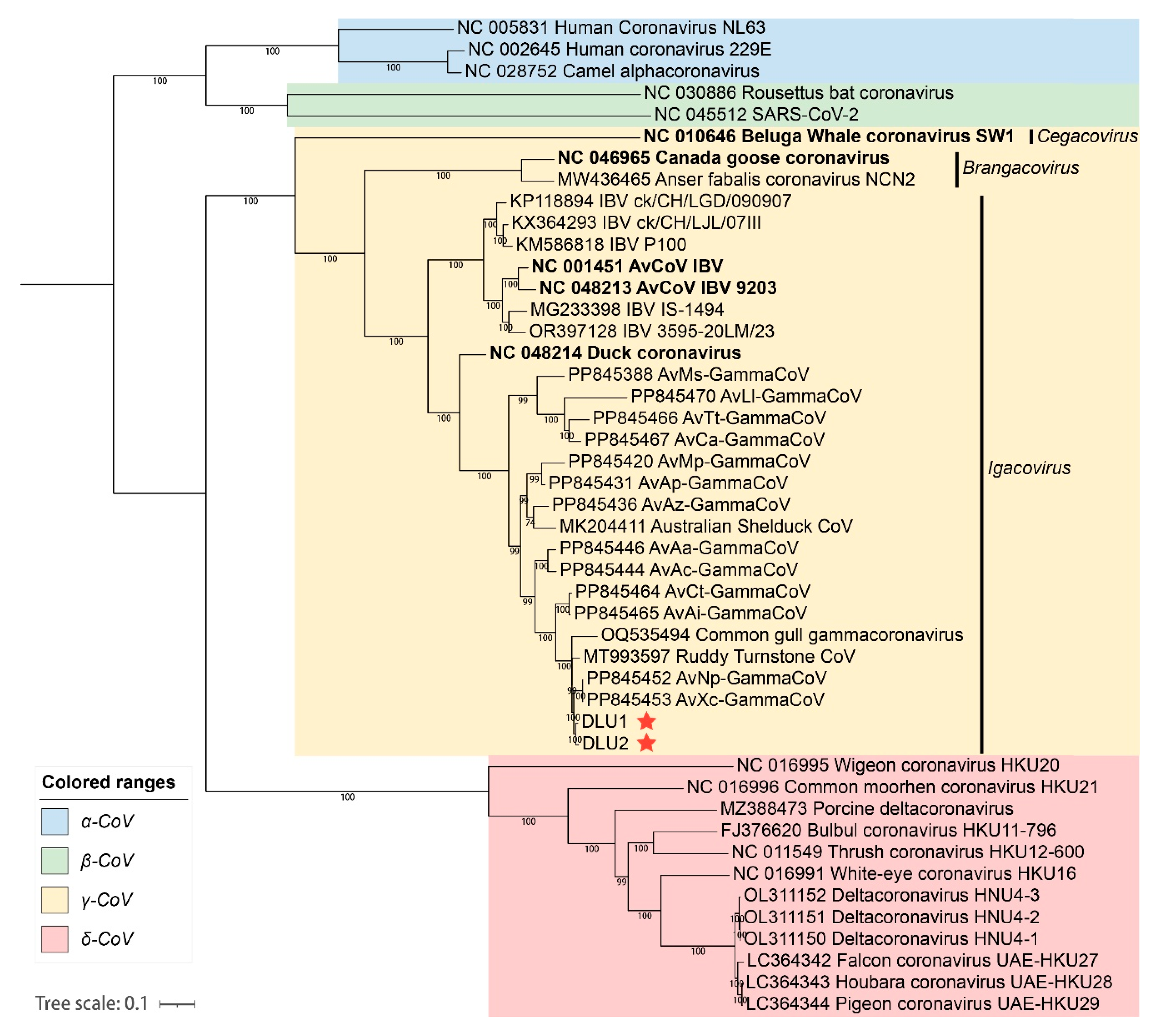

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of the Whole Genome BHG-GCoVs

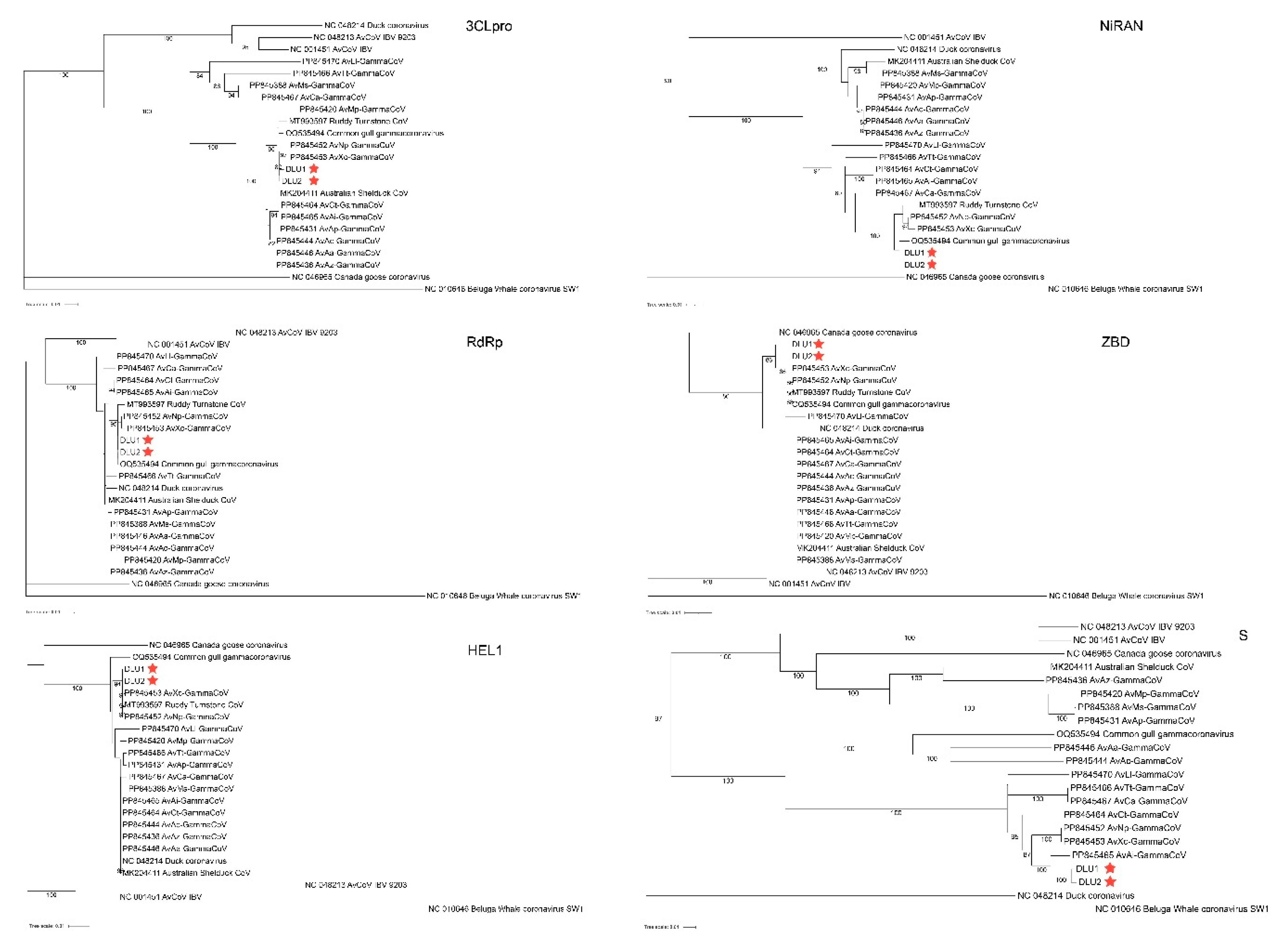

2.5. Phylogenetic Evolution of the Domains of BHG-GCoVs

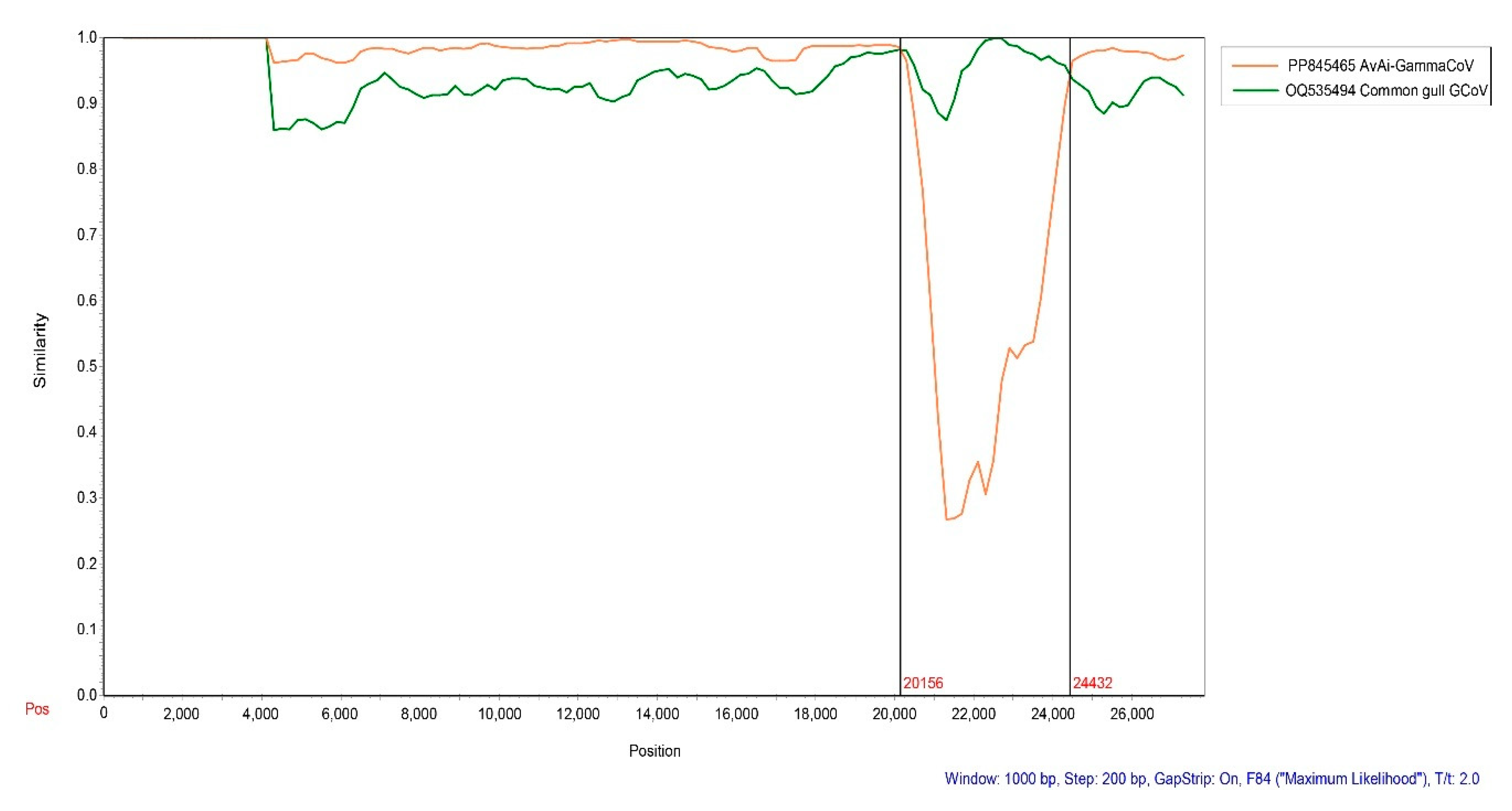

2.6. Recombination Analysis of BHG-GCoVs

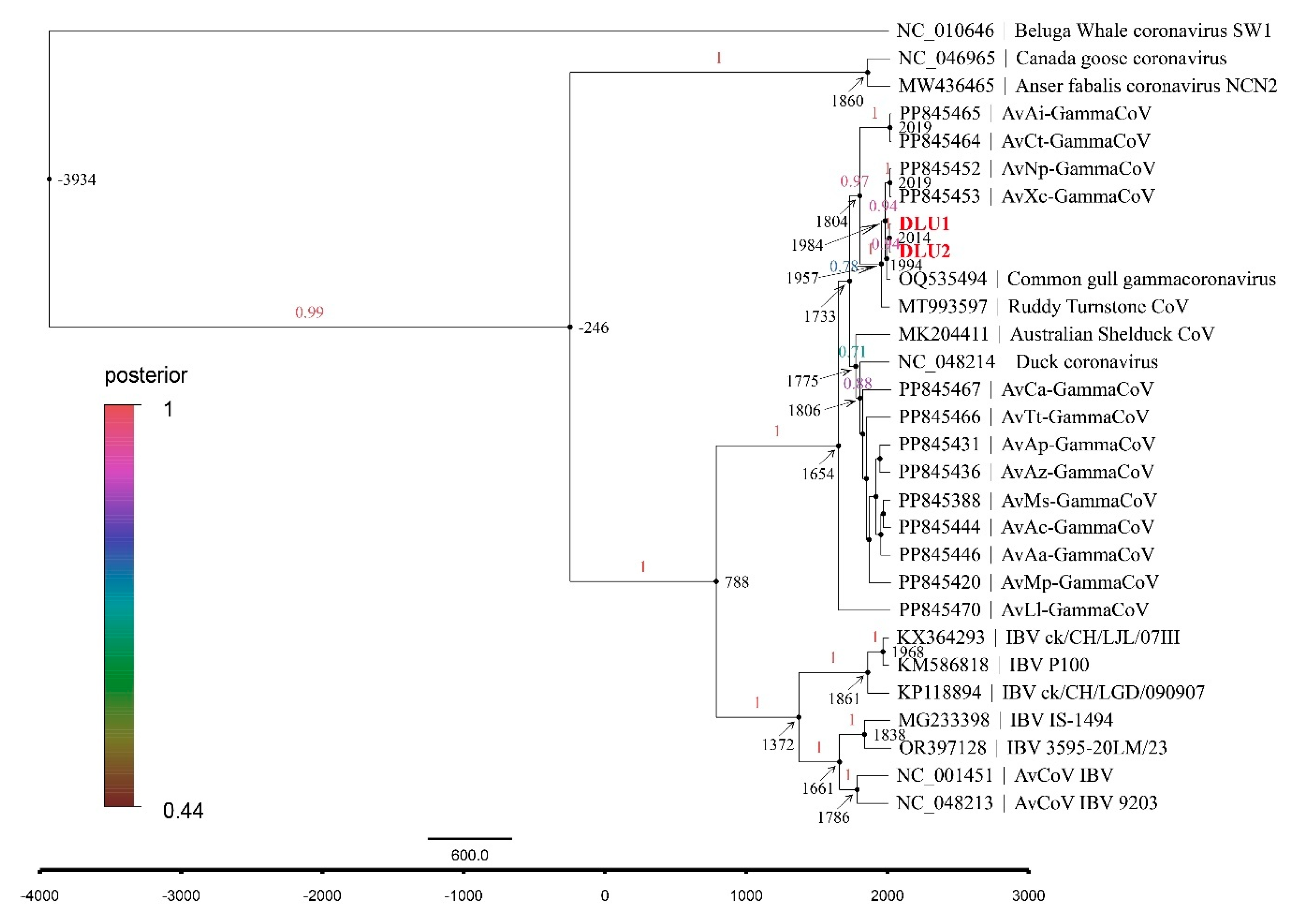

2.7. Evolutionary Rate and tMRCA

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection

4.2. RNA Extraction and CoV Screening by RT- PCR

4.3. Complete Genome Sequencing

4.4. Genomic and Phylogenetic Analysis

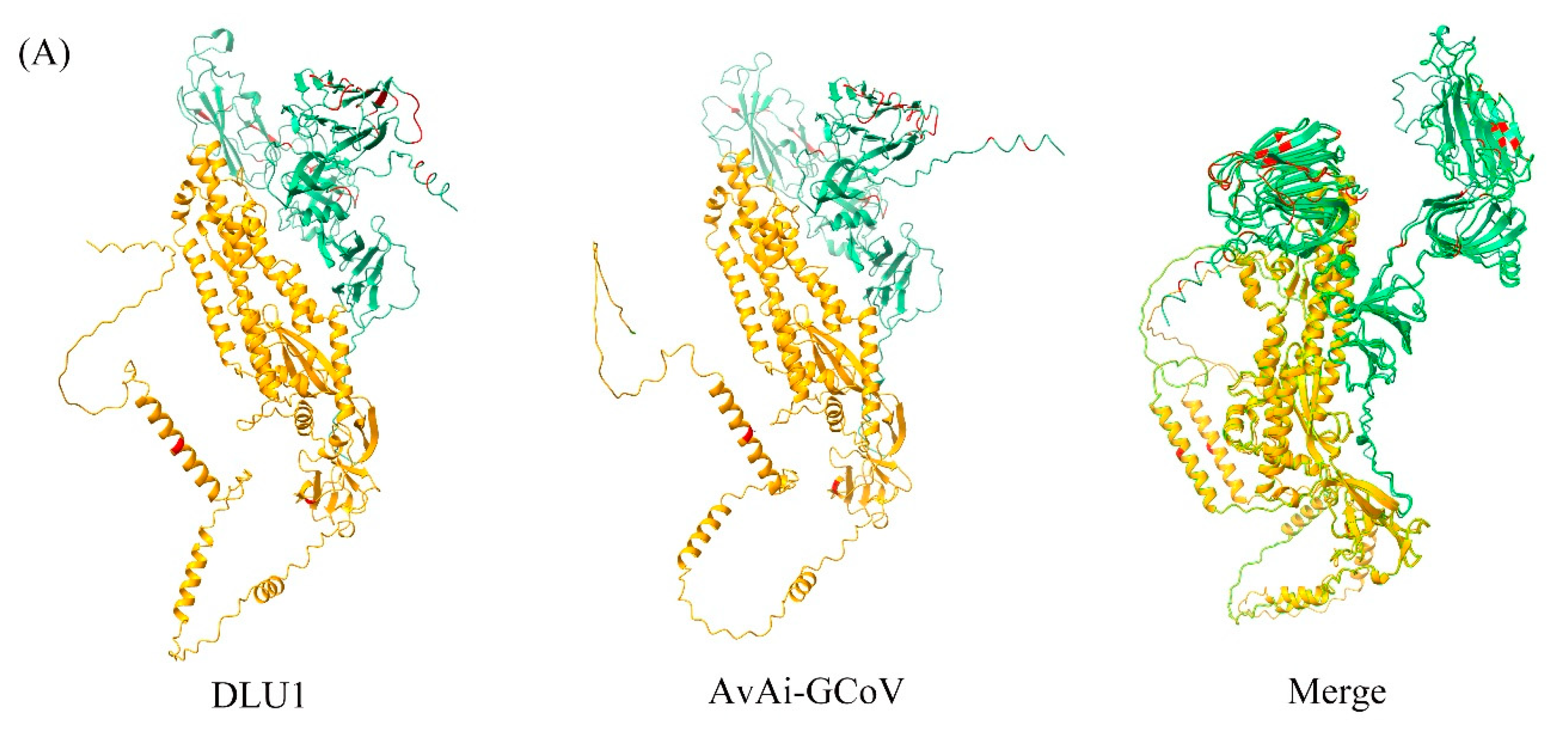

4.5. Protein Tertiary Structure Analysis

4.6. Estimation of Divergence Dates

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, G. SARS Molecular Epidemiology: A Chinese Fairy Tale of Controlling an Emerging Zoonotic Disease in the Genomics Era. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 362, 1063–1081. [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.-Y.; Li, J.-L.; Yang, X.-L.; Chmura, A.A.; Zhu, G.; Epstein, J.H.; Mazet, J.K.; Hu, B.; Zhang, W.; Peng, C.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of a Bat SARS-like Coronavirus That Uses the ACE2 Receptor. Nature 2013, 503, 535–538. [CrossRef]

- Sabir, J.S.M.; Lam, T.T.-Y.; Ahmed, M.M.M.; Li, L.; Shen, Y.; Abo-Aba, S.E.M.; Qureshi, M.I.; Abu-Zeid, M.; Zhang, Y.; Khiyami, M.A.; et al. Co-Circulation of Three Camel Coronavirus Species and Recombination of MERS-CoVs in Saudi Arabia. Science 2016, 351, 81–84. [CrossRef]

- Annan, A.; Baldwin, H.J.; Corman, V.M.; Klose, S.M.; Owusu, M.; Nkrumah, E.E.; Badu, E.K.; Anti, P.; Agbenyega, O.; Meyer, B.; et al. Human Betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012–Related Viruses in Bats, Ghana and Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 456–459. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qi, J.; Yuan, Y.; Xuan, Y.; Han, P.; Wan, Y.; Ji, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Bat Origins of MERS-CoV Supported by Bat Coronavirus HKU4 Usage of Human Receptor CD26. Cell Host Microbe. 2014, 16, 328–337. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Du, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Tang, J.; Baric, R.S.; Jiang, S.; Li, F. Receptor Usage and Cell Entry of Bat Coronavirus HKU4 Provide Insight into Bat-to-Human Transmission of MERS Coronavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 12516–12521. [CrossRef]

- V’kovski, P.; Kratzel, A.; Steiner, S.; Stalder, H.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus Biology and Replication: Implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 155–170. [CrossRef]

- Wacharapluesadee, S.; Tan, C.W.; Maneeorn, P.; Duengkae, P.; Zhu, F.; Joyjinda, Y.; Kaewpom, T.; Chia, W.N.; Ampoot, W.; Lim, B.L.; et al. Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 Related Coronaviruses Circulating in Bats and Pangolins in Southeast Asia. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 972. [CrossRef]

- Worobey, M.; Levy, J.I.; Malpica Serrano, L.; Crits-Christoph, A.; Pekar, J.E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Rasmussen, A.L.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Newman, C.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; et al. The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan Was the Early Epicenter of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Science 2022, 377, 951–959. [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: An Overview of Their Replication and Pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1282, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Bárcena, M.; Oostergetel, G.T.; Bartelink, W.; Faas, F.G.A.; Verkleij, A.; Rottier, P.J.M.; Koster, A.J.; Bosch, B.J. Cryo-Electron Tomography of Mouse Hepatitis Virus: Insights into the Structure of the Coronavirion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 582–587. [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.T.-Y.; Jia, N.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Shum, M.H.-H.; Jiang, J.-F.; Zhu, H.-C.; Tong, Y.-G.; Shi, Y.-X.; Ni, X.-B.; Liao, Y.-S.; et al. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-Related Coronaviruses in Malayan Pangolins. Nature 2020, 583, 282–285. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Ge, X. The Taxonomy, Host Range and Pathogenicity of Coronaviruses and Other Viruses in the Nidovirales Order. Anim. Dis. 2021, 1, 5. [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Lam, C.S.F.; Lau, C.C.Y.; Tsang, A.K.L.; Lau, J.H.N.; Bai, R.; Teng, J.L.L.; Tsang, C.C.C.; Wang, M.; et al. Discovery of Seven Novel Mammalian and Avian Coronaviruses in the Genus Deltacoronavirus Supports Bat Coronaviruses as the Gene Source of Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus and Avian Coronaviruses as the Gene Source of Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3995–4008. [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, D. Coronavirus Avian Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Vet. Res. 2007, 38, 281–297. [CrossRef]

- Bande, F.; Arshad, S.S.; Omar, A.R.; Hair-Bejo, M.; Mahmuda, A.; Nair, V. Global Distributions and Strain Diversity of Avian Infectious Bronchitis Virus: A Review. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2017, 18, 70–83. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Kong, X.; Shao, Y.; Han, Z.; Feng, L.; Cai, X.; Gu, S.; Liu, M. Isolation of Avian Infectious Bronchitis Coronavirus from Domestic Peafowl (Pavo Cristatus) and Teal (Anas). J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 86, 719–725. [CrossRef]

- Quinteros, J.A.; Ignjatovic, J.; Chousalkar, K.K.; Noormohammadi, A.H.; Browning, G.F. Infectious Bronchitis Virus in Australia: A Model of Coronavirus Evolution – a Review. Avian. Pathol. 2021, 50, 295–310. [CrossRef]

- Hepojoki, S.; Lindh, E.; Vapalahti, O.; Huovilainen, A. Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Coronaviruses in Wild Birds, Finland. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2017, 7, 1408360. [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Huang, Y.; Yuen, K.-Y. Coronavirus Diversity, Phylogeny and Interspecies Jumping. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2009, 234, 1117–1127. [CrossRef]

- Honkavuori, K.S.; Briese, T.; Krauss, S.; Sanchez, M.D.; Jain, K.; Hutchison, S.K.; Webster, R.G.; Lipkin, W.I. Novel Coronavirus and Astrovirus in Delaware Bay Shorebirds. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93395. [CrossRef]

- Muradrasoli, S.; Bálint, Á.; Wahlgren, J.; Waldenström, J.; Belák, S.; Blomberg, J.; Olsen, B. Prevalence and Phylogeny of Coronaviruses in Wild Birds from the Bering Strait Area (Beringia). PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13640. [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Leung, C.Y.H.; Gilbert, M.; Joyner, P.H.; Ng, E.M.; Tse, T.M.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Poon, L.L.M. Avian Coronavirus in Wild Aquatic Birds. J Virol. 2011, 85, 12815–12820. [CrossRef]

- Ushine, N.; Sato, T.; Kato, T.; Hayama, S. Analysis of Body Mass Changes in the Black-Headed Gull (Larus Ridibundus) during the Winter. J. Vet. Med Sci. 2017, 79, 1627–1632. [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Qian, J.; Yang, R.; Gu, W.; Li, R.; Yang, T.; Fu, X.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, Y. Metagenomics of Gut Microbiome for Migratory Seagulls in Kunming City Revealed the Potential Public Risk to Human Health. BMC Genomics 2023, 24, 269. [CrossRef]

- Domańska-Blicharz, K.; Miłek-Krupa, J.; Pikuła, A. Diversity of Coronaviruses in Wild Representatives of the Aves Class in Poland. Viruses 2021, 13, 1497. [CrossRef]

- Domańska-Blicharz, K.; Miłek-Krupa, J.; Pikuła, A. Gulls as a Host for Both Gamma and Deltacoronaviruses. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15104. [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.-K.; Zhou, Z.-J.; Wang, Q.; Ye, S.-B.; Guo, L.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Ge, X.-Y. Characterization of Deltacoronavirus in Black-Headed Gulls (Chroicocephalus ridibundus) in South China Indicating Frequent Interspecies Transmission of the Virus in Birds. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 895741. [CrossRef]

- Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Baker, S.C.; Baric, R.S.; De Groot, R.J.; Drosten, C.; Gulyaeva, A.A.; Haagmans, B.L.; Lauber, C.; Leontovich, A.M.; et al. The Species Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Related Coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and Naming It SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 536–544. [CrossRef]

- Kesheh, M.M.; Hosseini, P.; Soltani, S.; Zandi, M. An Overview on the Seven Pathogenic Human Coronaviruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2282. [CrossRef]

- Geldenhuys, M.; Mortlock, M.; Epstein, J.H.; Pawęska, J.T.; Weyer, J.; Markotter, W. Overview of Bat and Wildlife Coronavirus Surveillance in Africa: A Framework for Global Investigations. Viruses 2021, 13, 936. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.-H.; Han, P.-Y.; Tian, J.-W.; Zong, L.-D.; Yin, H.-M.; Zhao, J.-Y.; Yang, Z.; Kong, W.; Ge, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Z. Detection of Alpha- and Betacoronaviruses in Small Mammals in Western Yunnan Province, China. Viruses 2023, 15, 1965. [CrossRef]

- Lednicky, J.A.; Tagliamonte, M.S.; White, S.K.; Elbadry, M.A.; Alam, Md.M.; Stephenson, C.J.; Bonny, T.S.; Loeb, J.C.; Telisma, T.; Chavannes, S.; et al. Independent Infections of Porcine Deltacoronavirus among Haitian Children. Nature 2021, 600, 133–137. [CrossRef]

- Wille, M.; Shi, M.; Klaassen, M.; Hurt, A.C.; Holmes, E.C. Virome Heterogeneity and Connectivity in Waterfowl and Shorebird Communities. The ISME Journal 2019, 13, 2603–2616. [CrossRef]

- Wille, M.; Shi, M.; Hurt, A.C.; Klaassen, M.; Holmes, E.C. RNA Virome Abundance and Diversity Is Associated with Host Age in a Bird Species. Virology 2021, 561, 98–106. [CrossRef]

- Wille, M.; Eden, J.; Shi, M.; Klaassen, M.; Hurt, A.C.; Holmes, E.C. Virus–Virus Interactions and Host Ecology Are Associated with RNA Virome Structure in Wild Birds. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 5263–5278. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.-Y.; Wang, K.-C.; Liu, S.; Hou, G.-Y.; Jiang, W.-M.; Wang, S.-C.; Li, J.-P.; Yu, J.-M.; Chen, J.-M. Genomic Analysis and Surveillance of the Coronavirus Dominant in Ducks in China. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129256. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.-W.; Wen, H.-L. Research Progress on Coronavirus S Proteins and Their Receptors. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 1811–1817. [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Zou, X.; Chen, J.; Tang, X. PEDV: Insights and Advances into Types, Function, Structure, and Receptor Recognition. Viruses 2022, 14, 1744. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Tsai, L.; Huang, M.; Jhuang, J.; Yao, C.; Chin, S.; Wang, L.; Linacre, A.; Hsieh, H. A Novel Strategy for Avian Species Identification by Cytochromeb Gene. Electrophoresis 2008, 29, 2413–2418. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-J.; Qiu, Y.; Pu, Y.; Huang, X.; Ge, X.-Y. BioAider: An Efficient Tool for Viral Genome Analysis and Its Application in Tracing SARS-CoV-2 Transmission. Sustain Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102466. [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Murrell, B.; Golden, M.; Khoosal, A.; Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and Analysis of Recombination Patterns in Virus Genomes. Virus Evol.2015, 1, vev003. [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.J.; Suchard, M.A.; Xie, D.; Rambaut, A. Bayesian Phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 1969–1973. [CrossRef]

| Sampling site | γ-CoV | δ-CoV | |||

| Prevalence | 95%CI | Prevalence | 95%CI | ||

| Cuihu Park | 4.44%(10/225) | 1.73%-7.16% | 1.78%(4/225) | 0.04%-3.52% | |

| Daguanlou Park | 15.00%(12/80) | 7.00%-23.00% | 12.50%(10/80) | 5.09%-19.91% | |

| Haigeng Dam | 9.31% (19/204) | 5.29%-13.34% | 1.96%(4/204) | 0.04%-3.88% | |

| Total | 8.06% (41/509) | 5.68%-10.43% | 3.54%(18/509) | 1.90%-5.10% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).